Gérard de Nerval

Travels in the Near East (Voyage en Orient, 1843)

Part XVII: Ramadan Nights (Les Nuits Du Ramazan) – The Storytellers: Chapters 9 to 12, and the Lesser Bayram (Eid al-Fitr)

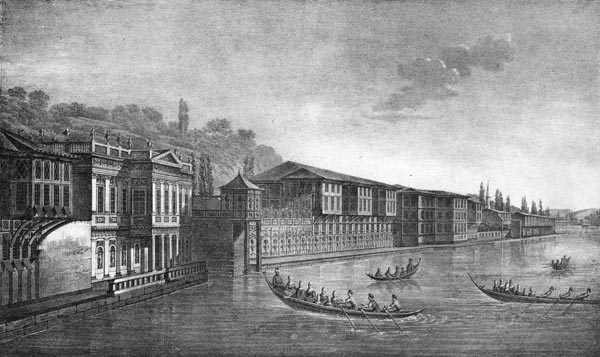

The Palace of Sultan Hatice, 1822 - 1828, Louis Goubaud

Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Ramadan Nights (Les Nuits Du Ramazan).

- Chapter 9: The Three Companions.

- Chapter 10: The Interview.

- Chapter 11: The King’s Supper.

- Chapter 12: Machbenach (Mahabon).

- The Lesser Bayram (Eid al-Fitr).

- Chapter 1: The ‘Eaux-Douces d’Asie’ (Küçüksu Deresi, the Sweet Waters of Asia).

- Chapter 2: The Lesser Bayram.

- Chapter 3: The Seraglio Festivities.

Ramadan Nights (Les Nuits Du Ramazan)

Chapter 9: The Three Companions

— At the next session, the storyteller continued:

Soliman and the high priest of the Israelites had been talking for some time in the Temple courtyard.

— ‘It is obligatory,’ said the vexed pontiff Zadoc to his king, ‘and you have no need of my consent to this fresh delay. How can a marriage be celebrated if the bride is not there?’

— ‘Venerable Zadoc,’ resumed the prince with a sigh, ‘these disappointing delays affect me more than you, and I am forced to endure them with patience.’

— ‘That is fine; but I am not in love,’ said the Levite, passing his dry, pale hand, veined with blue lines, over his long, white, forked beard.

— ‘That is why you should be calmer than I.’

— ‘What!’ replied Zadoc. For four days, the men-at-arms and the Levites have been on their feet; the burnt offerings are ready; yet the fire burns uselessly on the altar, and, on the verge of the solemn moment, everything must be postponed. Priests and king are at the mercy of the whims of a foreign woman, who beguiles us with pretext after pretext and plays on our credulity.’

What humiliated the high priest was to clad himself uselessly each day in pontifical ornaments, and to be obliged to strip himself of them afterwards without having been allowed to display, to the eyes of the Sabaean courtiers, the hieratic pomp of the ceremonies of Israel. He walked, agitated, about the inner courtyard of the Temple, his splendid costume glittering, before the dismayed Soliman.

For the august ceremony, Zadok had put on his linen robe, his embroidered belt, his ephod open on each shoulder; a tunic of gold, hyacinth, and twice-dyed scarlet, upon which shone two onyxes, engraved by the lapidary with the names of the twelve tribes. Suspended by hyacinthine ribbons, from rings of chased gold, the liturgical cloth sparkled on his chest; it was square, a palm long and bordered with a row of sardonyxes, topazes, and emeralds, a second row of carbuncles, sapphires and jasper; a third row of opals, amethysts, and agates; a fourth, finally, of chrysolites, onyxes and beryl. The tunic of the ephod, of a light violet, open in the middle, was bordered with small pomegranates of hyacinth and purple, alternating with bells of fine gold. The pontiff’s brow was encircled with a tiara topped by a crescent of linen cloth, embroidered with pearls, and on the front part of which shone, attached to a ribbon of hyacinth colour, a blade of burnished gold, bearing these words engraved in relief: ‘Adonai is Holy’.

It too two hours, and six servants of the Levites, to clothe Zadok in these sacred accoutrements, attached by chains, mystical knots, and gilded clasps. The costume was sacred; the Levites alone were permitted to wear it; and it was Adonai himself who had dictated the design to Moussa-Ben-Amran (Moses), his servant.

For four days, therefore, the pontifical finery of the successors of Melchizedek had suffered a daily outing borne on the shoulders of the respectable Zadoc, who was all the more irritated, since, being obliged, much against his will, to consecrate the marriage of Soliman with the Queen of Sheba, he now suffered such delay as rendered his disappointment even more acute.

Their union seemed to him a threat to the religion of the Israelites, and the power of the priesthood. Queen Balkis was educated.... he had discovered that the Sabaean priests had allowed her to learn many things of which a prudent sovereign should remain ignorant; and he was anxious regarding the influence of a queen versed in the difficult art of commanding strange birds. Such mixed marriages which exposed the faith to the endless attacks of sceptical spouses never pleased the pontiffs. And Zadoc, who had with great difficulty moderated in Soliman the latter’s pride in his own knowledge, by convincing him that there was nothing more to learn, trembled lest the monarch recognise the many things of which he was ignorant.

This thought was all the more judicious, since Soliman was already at a stage of reflection at which he found his ministers at once less subtle and more despotic than those of the queen. Ben-Daoud’s confidence was shaken; he had, for some days, concealed his thoughts from Zadoc, and no longer consulted him. The unfortunate thing, in countries where religion is subordinate to the priests and personified by them, is that, from the day the pontiff fails, and everything mortal seems frail, faith collapses with him, while his proud and fatal confidence, and even God Himself are eclipsed.

Circumspect, touchy, but in no way profound, Zadoc had maintained his position without difficulty, being possessed of the good fortune of having few ideas. Adapting his interpretation of the law to suit the passions of the prince, he justified this with a dogmatic complacency which was base, but punctilious as regards form; in this way, Soliman bore the yoke with docility.... and to think that now a young girl from Yemen and an accursed bird risked overthrowing the edifice of so prudent an education!

To accuse them of the practice of magic, was that not to confess the power of those occult sciences, so disdainfully denied? Zadoc experienced true embarrassment. He had, moreover, other concerns: the power Adoniram exercised over the workmen troubled the high priest, rightly alarmed by any seemingly occult and cabalistic domination. Nevertheless, Zadoc had constantly prevented his royal pupil from dismissing the only artist capable of raising, to the glory of the Lord Adonai, the most magnificent Temple in the world, and of attracting to the foot of the altar of Jerusalem the admiration and the offerings of all the peoples of the East. To be rid of Adoniram, Zadoc awaited the end of the work, limiting himself until then to fostering Soliman’s touchy mistrust. For some days, the situation had been worsening. Amidst the splendour of an unexpected, impossible, miraculous triumph, Adoniram, we recall, had disappeared. This absence astonished the whole court, except, apparently, the king, who had not spoken of it to his high priest; thereby displaying unusual restraint.

Thus, the venerable Zadoc, finding himself rendered useless, while determined to remain essential, was reduced to combining with vague prophetic declamations oracular utterances calculated to make an impression on the imagination of the prince. Soliman was rather fond of speeches, especially because they offered him the opportunity of summarising their meaning in a few proverbs. Now, in the current circumstances, the sentences of the Ecclesiastes, far from being moulded on the homilies of Zadoc, were simply reflections on the rightness of his master’s instincts, on the dangers of mistrust, and on the misfortune of kings dedicated to cunning, lies and self-interest. Zadoc, troubled, withdrew into the depths of the unintelligible.

— ‘Although you speak eloquently, as ever’ said Soliman, ‘it is not to enjoy your speeches that I have come to find you here in the Temple: woe to the king who feeds only on words! Three strangers will present themselves here, and ask to speak to me, and they shall be heard, since I know their intent. For their audience, I have chosen this place; it was important that their visit remains a secret.’

— ‘These men, lord, who are they?’

— ‘Men who are instructed in matters of which kings are ignorant: one may learn a great deal from them.’

Soon, three artisans, led to the inner courtyard of the temple, prostrated themselves at Soliman’s feet. Their actions were constrained, their gaze worried.

— ‘May the truth be on your lips.’ said Soliman to them, ‘Hope not to impose upon the king: your most secret thoughts are known to me. You, Phanor, a simple workman amidst the host of masons, you are Adoniram’s enemy, hating the supremacy of the miners, and, to thwart your master’s work, you mixed combustible stones with the bricks of his furnaces. Amrou, a member of the carpenters’ company, you set the beams in the flames, to weaken the foundations of the brazen sea. As for you, Methousael, miner of the tribe of Reuben, you contaminated the cast iron with sulphurous lava, collected from the shores of Lake Gomorrah. All three of you aspire in vain to the titles and pay of your masters. You see, I penetrate the secrets of your most hidden actions.’

— ‘Great king,’ replied Phanor, terrified, ‘these are slanders created by Adoniram, who has plotted our ruin.’

— ‘Adoniram is unaware of a plot revealed only to myself. Know this, nothing escapes the sagacity of those whom Adonai protects.’

Zadok’s look of astonishment informed Soliman that his high priest thought little of Adonai’s favour.

— ‘Therefore, you disguise the truth in vain,’ continued the king. What you reveal is already known to me, and it is your loyalty that is being tested. Let Amrou speak first.’

— ‘Lord,’ said Amrou, no less frightened than his accomplices, ‘I have maintained absolute surveillance over the workshops, construction sites, and manufactories. Adoniram has not appeared there once.’

— ‘I,’ continued Phanor, ‘hid myself, at nightfall, in the tomb of Prince Absalon-Ben-Daoud, on the road which leads from Moriah to the camp of the Sabaeans. Towards the third hour of the night, a man dressed in a long robe, wearing a turban such as the Yemenites adopt, passed before me; I advanced and recognised Adoniram; he was on his way to the queen’s pavilions, and, as he had noticed me, I dared not follow.’

— ‘Lord,’ continued Methusael in his turn, ‘you know everything, and wisdom dwells with you; I speak sincerely. My revelations may be of such a nature as to cost the lives of those who have penetrated their mysteries, deign to send away my companions, so that my words condemn me alone.’

As soon as the miner was alone in the presence of the king and the high priest, he prostrated himself and said:

— ‘Lord, stretch out your sceptre, and grant me life.’

Soliman stretched out his hand and answered:

— ‘Your honesty protects you; fear nothing, Methousael, of the tribe of Reuben!’

— ‘My forehead covered with a caftan, my face coated with a dark dye, I mingled, under cover of night, with the black eunuchs who surround the princess: Adoniram slipped through the shadows to her feet; he spoke to her at length, and the evening wind carried their words, tremulously, to my ear; an hour before dawn, I slipped away: Adoniram was still with the princess....’

Soliman contained an anger the signs of which Methusael saw in his eyes.

— ‘My king!’ he cried, ‘I have obeyed you; permit me to be silent.’

— ‘Continue! I command you.’

— ‘Lord, your glory is dear to your subjects. I will die, if needs be; but my master shall not be the plaything of these perfidious foreigners. The high priest of the Sabaeans, the nurse and two of the queen’s wives are party to this secret affair. If I understand aright, Adoniram is not what he appears to be, and is invested, as is the princess, with magical powers. Through them she commands the inhabitants of the air, as the artist commands the spirits of fire. Nevertheless, this pair of favoured beings fear your power over the genies, a power with which you are endowed without your knowing. Sarahil spoke of a gemmed ring whose marvellous properties she explained to the astonished queen, and deplored Balkis’ imprudence in the matter. I could not catch the gist of the conversation, because their voices were lowered, and I feared for my life if I approached too closely. Soon Sarahil, the high priest, and the maids, withdrew, after bowing to Adoniram, who, as I said, was left alone with the Queen of Sheba. O my king! May I find favour in your eyes, for deceit has not touched my lips!’

— ‘What right have you to fathom your master’s intentions? Whatever my decision may be, it will be just.... Let this man be shut up in the temple like his companions; he must not communicate with them, until the moment when I decide their fate.’

Who could describe the high priest Zadoc’s amazement, as the king’s mutes, prompt and discreet executors of his will, dragged away the terrified Methusael?

— ‘You see, O most respectable Zadoc,’ the monarch said, bitterly,’ your prudence has penetrated nothing; deaf to our prayers, little touched by our sacrifices, Adonai has not deigned to enlighten his servants, and it is I alone, with the aid of my own intellect, who reveal the plotting of my enemies. They, however, command occult powers. Their gods are loyal to them... while mine deserts me!’

— ‘Because you disdain Him, to seek union with a foreign woman. O my king, banish from your soul that impure feeling, and your adversaries will be delivered to you. But how to seize this Adoniram who renders himself invisible, and this queen whom hospitality protects?’

— ‘To take revenge on a woman is beneath the dignity of Soliman. As for her accomplice, in a moment you will see him appear. This very morning, he sought an audience, and it is here that I await him.’

— ‘Adonai favours us, O king! Let not the man leave this enclosure!’

— ‘If he comes here, fearlessly, be assured his defenders are not far away; but let us not be blindly precipitate: these three men here are his mortal enemies. Envy, and greed have embittered their hearts. They have, perhaps, slandered the queen.... I love her, Sadoc, and I would not insult the princess by believing her tainted by a degrading passion, based on the shameful remarks of three wretches.... But, fearing the underhanded machinations of Adoniram, so powerful among the people, I have had that mysterious character watched.’

— ‘So, you think he met with the queen?’

— ‘I am convinced he saw her in secret. She is curious, enthusiastic about the arts, ambitious for fame, and a tributary to my crown. Perhaps her design is to hire the artist, and employ him in her country for some magnificent enterprise, or to enlist, through his agency, an army to oppose mine, in order to free her kingdom from the tribute? I know not.... As for their alleged love affair, do I not have the word of the queen? However, I agree, any one of these suppositions alone is enough to demonstrate that the man is dangerous.... I will reflect on it....’

As he spoke, in his firm tone, in the presence of Zadoc, who was dismayed to find that his altar was disdained and his influence eclipsed, the mutes with their white spherical headdresses, their iron-plated jackets, and broad belts from which hung a dagger and a curved sabre, re-entered. They exchanged a sign with Soliman, and Adoniram appeared on the threshold. Six of his own men escorted him; he whispered a few words to them in a low voice, and they withdrew.

Chapter 10: The Interview

Adoniram advanced with a slow step, and confident countenance, to the massive throne on which was seated the king of Jerusalem. After a respectful bow, the artist waited, according to custom, until Soliman urged him to speak.

— ‘At last, master,’ said the prince, ‘yielding to my wish, you grant me the opportunity to congratulate you on an unexpected triumph ... and to demonstrate my gratitude. The work is worthy of my kingdom; and what is more, worthy of yourself. As for your reward, it cannot be sufficiently great; designate it yourself: what gift do you wish from Soliman?’

— ‘My leave to depart, lord: the work nears its end; it can be completed without me. My destiny is to travel the world; it calls me to other climes, and I place in your hands, once more, the authority with which you invested me. My reward is the monument I leave here, and the honour of having served as interpreter of the noble designs of so great a king.’

— ‘Your request distresses us. I had hoped to keep you among us, and with eminent status at court.’

— ‘My character, lord, would not repay such kindness. Independent by nature, solitary by vocation, indifferent to honours which I was not born to receive, I would oft put your indulgence to the test. Kings are of uneven temper; envy surrounds and besieges them; and fortune is inconstant: I have experienced too many of its vagaries. Did not what you term my triumph and glory almost cost me my honour, and even my life?’

— ‘I only considered your enterprise a failure when your own voice proclaimed it so, and I boast of no ascendancy over the spirits of fire....’

— ‘No one governs those spirits, if indeed they exist. Moreover, these mysteries are more within the reach of honest Zadoc than of a simple craftsman. What happened during this terrible night, I do not know: the course of the operation confounded my predictions. Only, my lord, in an hour of anguish, I waited in vain for your consolation, your support, and that is why, on the day of success, I no longer expected your praise.’

— ‘Master, that was due to your resentment and pride.’

— ‘No, my lord, it is a humble and sincere request for justice. From the night I poured the brazen sea until the dawn in which I revealed it to the world, my merit has certainly neither increased, nor decreased. Success has made all the difference ... and, as you have seen, success lies in the hand of God. Adonai loves you; he has been moved by your prayers, and it is I, Lord, who must congratulate you, and cry my thanks!’

— ‘Who will deliver me from this man’s irony?’ thought Soliman. ‘You are doubtless quitting my service so as to accomplish wonders elsewhere?’ he asked.

— ‘Not long ago, my lord, I would have sworn so. A host of burning ideas were stirring in my head; in my dreams I glimpsed blocks of granite, underground palaces with forests of columns, and the duration of our labours weighed on me. Today, my ardour subsides, fatigue lulls me, leisure smiles on me, and it seems to me that my career is over....’

Soliman thought he caught a glimpse of certain tender gleams that shimmered in Adoniram’s eyes. His face was grave, his physiognomy melancholy, his voice more penetrating than usual, such that Soliman, troubled, said to himself:

— ‘The man is handsome, indeed.’ ‘Where do you intend to go, on leaving my kingdom?’ he asked with a feigned indifference.

— ‘To Tyre,’ replied the artist, unhesitatingly: ‘I promised my patron so, the good King Hiram, who cherishes you like a brother, and who has shown me paternal kindness. If it be your pleasure, I wish to show him the plan, with elevated views, of the palace, the Temple, the brazen sea, as well as the two great twisted bronze columns, Jachin and Boaz, which adorn the great door of the Temple.

— ‘Let it be as you wish. Five hundred horsemen will serve as your escort, and twelve camels will carry the gifts and treasures chosen for you.’

— ‘This is too much: Adoniram will take but his cloak now. It is not, lord, that I refuse your gifts. You are generous; they are considerable, and my sudden departure would drain your treasury without profiting me at this moment. Allow me such utter frankness. The gifts I accept, but leave them in your hands. When I have need of them, lord, I will let you know.’

— ‘In other words,’ said Soliman, ‘Master Adoniram intends to render us his debtor.’

The artist smiled and answered gracefully:

— ‘Lord, you have divined my thought.’

— ‘And perhaps he reserves the right one day to dictate conditions to us.’

Adoniram exchanged a sharp, defiant look with the king.

— ‘I shall ask, however’ the former added, ‘for naught that is unworthy of Soliman’s magnanimity.’

— ‘I believe,’ said Soliman, weighing the effect of his words, ‘that the Queen of Sheba has plans in mind, and proposes to employ your talent...’.

— ‘Lord, she has said nothing to me of such.’

His answer gave rise to other suspicions.

— ‘Yet,’ objected Zadoc, ‘your genius has clearly not left her indifferent. Will you leave without saying your farewells to her?’

— ‘My farewells...?’ Adoniram repeated, and Soliman saw a strange light gleam in his eyes, ‘My farewells? If the king permits, I will indeed have the honour of taking leave of her.’

— ‘We had hoped,’ replied the prince, ‘to retain you until the imminent celebration of our marriage; for you know....’

Adoniram’s forehead was stained with a deep redness, and he added, though without bitterness:

— ‘It is my intention to journey to Phoenicia without delay.’

— ‘Since you demand it, master, you are free: I grant you leave....’

— ‘From sunset,’ commented the artist. ‘For, I still have to pay the workers, and I beg you, sir, to order your steward Azarias to have the necessary funds brought to the counter established at the foot of the pillar named Jachin. I will pay the men as usual, without announcing my journey, in order to avoid a tumultuous departure.’

— ‘Zadoc, transmit this order to your son Azarias. One more word: who are those three members of your company named Phanor, Amrou and Methousael?’

— ‘Three poor, honest, but ambitious people, though without talent. They aspire to the title of master, and pressed me to deliver the password to them, in order to obtain the right to a higher salary. Ultimately, they listened to reason, and recently I have had reason to praise their goodness of heart.’

— ‘Master, it is written: “fear the wounded serpent that hides its venom”. Know these men better: they are your enemies; it is they who, through their interference, caused those accidents which risked failure in regard to the casting of the brazen sea.’

— ‘How do you know this, lord...?’

— ‘Believing all was lost, but trusting in your prudence, I sought the hidden cause of the catastrophe, and, as I wandered among the crowd, these three men, believing themselves to be alone, spoke together.’

— ‘Their crime has caused the death of many. Such a precedent may prove dangerous; it is up to you to decide their fate. The accident cost me the life of a child I loved, of a skilled artist, Benoni, who since then, has not reappeared. Justice, my lord, is the privilege of kings.’

— ‘Justice shall be rendered to all. Live happily, Master Adoniram, Soliman will not forget you.’

Adoniram, pensive, seemed undecided and combative. Suddenly, yielding to momentary emotion, he said:

— ‘Whatever happens, lord, be forever assured of my respect, my pious memories, and the uprightness of my heart. And, if suspicion comes to your mind, say to yourself: ‘Like most human beings, Adoniram did not belong to himself alone; he was obliged to fulfil his destiny!’

— ‘Farewell, then, master.... go, and fulfil that destiny!’

With this, the king held out a hand to him, over which the artist bowed humbly; but failed to set his lips to it, and Soliman shuddered.’

— ‘Well,’ murmured Zadoc as he watched Adoniram withdraw, ‘what is your command, lord?’

— ‘Maintain the deepest silence, venerable father. From now on, I trust only myself. Know this, I am the king. To obey under pain of disgrace, and to be silent under pain of losing life and limb, that is your lot.... Come, old man, do not tremble: the sovereign who delivers his secrets for your instruction is a friend. Summon the three workmen prisoned in the Temple; I wish to question them again.’

Amrou, Phanor and Methousael duly appeared: behind them stood the sinister mutes, sabre in hand.

— ‘I have weighed your words,’ said Soliman in a severe tone, ‘and I have met with Adoniram, my servant. Is it the desire for equity, is it envy that animates you against him? How dare mere workmen judge their master? If you were notable men and leaders among your brothers, your testimony would be less suspect.... But no; greedy, and ambitious for the title of master, you have failed to obtain it, and resentment embitters your hearts.’

— ‘Lord,’ said Methusael, prostrating himself, ‘you wish to test us. But, even if it should cost me my life, I will maintain that Adoniram is a traitor; in plotting his destruction, I sought only to save Jerusalem from the tyranny of a perfidious man, who intends to enslave my country to foreign hordes. My imprudent frankness is the surest guarantee of my fidelity.’

— ‘It does not suit me to put my faith in contemptible men, in the slaves of my servants. Death has created a number of vacancies among the masters: Adoniram asks leave to rest, and I wish, as he does, to find, among the leaders, people worthy of my trust. This evening, after payment has been made, ask him for to be initiated among the masters; he will be alone.... Seek to make your reasoning heard. By this, I will know that you are hardworking, eminent in your art, and well placed in the esteem of your brothers. Adoniram is enlightened: his decisions are law. Has God abandoned him until now? Has He signalled his reprobation by one of those sinister warnings, by one of those terrible blows with which his invisible arm knows how to strike the guilty? Well, let Jehovah then be judge between you: if the favour of Adoniram distinguishes you from the others, it will be for me a covert sign that the heavens declare themselves for you, and I will deal with Adoniram. But, if he denies you the degree of master, tomorrow you will appear with him before me; I will hear the accusation and defence offered by the parties: the elders of the people will decide. Go, meditate on my words, and may Adonai be with you.’

Soliman rose from his seat, and, leaning on the shoulder of the impassive high priest, he slowly walked away.

The three men drew closer together, by mutual consent.

— ‘We must extract the password from him!’ said Phanor.

— ‘Or he must die!’ added the Phoenician, Amrou.

— ‘Let him yield us the masters’ password, and then die!’ cried Methousael.

Their hands joined in a triple oath. Upon the threshold, Soliman, turning away, observed them from afar, sighed heavily, and said to Zadoc:

— ‘Now, to pleasure!... Let us go find the queen.’

Chapter 11: The King’s Supper

— At the next session, the storyteller continued, thus:

The sun was beginning to set; the fiery breath of the desert set the countryside ablaze, illuminated by the reflections from a mass of coppery cloud; the shadow of the hill of Moria alone cast a little freshness on the dried-up bed of the Kidron; the failing leaves drooped, and the dead flowers on the oleanders hung there, scorched and crumpled; the chameleons, salamanders, and lizards were wriggling among the rocks and, the murmuring of the groves suspended, the sound of the streams had ceased.

Anxious and chilled, despite the heat and dreariness of the day, Adoniram, as he had announced to Soliman, went to take leave of his royal lover, prepared for the separation that she herself had requested.

— ‘To accompany me,’ she had said, ‘would be to oppose Soliman, to humiliate him in the face of his people, and to add outrage to the pain that the eternal powers have forced me to cause him. To remain here after my departure, dear husband, would be to seek your own death. The king is jealous of you, and my flight would leave behind no other victim than yourself, at the mercy then of his resentment.’

— ‘Well, let us share the fate of the children of our race, that of wanderers, scattered throughout the world. I promised the king I would journey to Tyre. Let us prove true, once your life is no longer at the mercy of a lie. This very night, I will set out for Phoenicia, where I shall not linger before travelling to join you in Yemen, via Syria and Arabia Petraea, by threading, thereafter, the defiles of the Cassanite Mountains (North of Yemen, according to Ptolemy, ‘Geographia VII’). Alas! Dear queen, must I leave you already, abandoning you, in a foreign land, to the mercy of an amorous despot?’

— ‘Rest assured, my lord, my soul is yours utterly, my servants are faithful, and the dangers will vanish conquered by prudence. Tempestuous and dark will be the coming night, which will hide my flight. As for Soliman, I loathe him; it is my kingdom he covets: he surrounds me with spies; seeks to seduce my servants, to suborn my officers, to negotiate with them for the surrender of my fortresses. If he had acquired rights over my person, I would never have seen fair Yemen again. He extorted a promise from me, it is true; but what is my perjury compared to his disloyalty? How could I not deceive him, moreover, he who has made me understand, with ill-disguised threats, that his love is boundless, but his patience at an end?’

— ‘We must rouse the companies of workmen!’

— ‘They await their pay; they will not move. Why take so perilous a risk? Your declaration, far from alarming me, suffices me; I had foreseen it, and awaited it impatiently. Go in peace, my beloved! Balkis will never be anyone’s but yours!’

— ‘Farewell then, my queen: I must quit this tent where I have found a happiness of which I never dreamed; I must cease to contemplate the face of one who is life to me. Will I see you again? Alas! These brief moments will pass like a dream!’

— ‘No, Adoniram; soon, we shall be united forever!... My dreams, my presentiments, in accord with the genies’ oracular words, assure me of the permanence of our race, and I carry with me a precious pledge of our marriage. You shall receive a son destined to grant us rebirth, and to free Yemen and all Arabia from the frail yoke of Soliman’s heirs. A double attraction draws you, a double affection attaches you, to one who loves you, and you will return to me.’

Adoniram, moved, pressed his lips to a hand on which the queen had shed tears, and, gathering his courage, cast upon her a long, last glance; then, turning away with effort, he let the curtain of the tent fall behind him, and regained the banks of the Kidron.

It was at Millo that Soliman, torn between anger, love, suspicion, and anticipated remorse, waited, given over to febrile longing for the smiling and desolated queen, while Adoniram, striving to bury his jealousy in the depths of his sorrow, hastened to the Temple to pay the workmen before taking up his staff of exile. Each of these personages thought to triumph over his rival, and counted on a secrecy already penetrated on both their sides. The queen disguised her goal, while Soliman, all too well-informed, dissimulated in his turn, seeking to hide a cunning born of self-esteem.

From the heights of the terraces of Millo, he surveyed the retinue of the Queen of Sheba, which wound along the path of Emathia, where, above Balkis, the purple walls of the Temple, over which Adoniram yet reigned, shone in sharp dentilated outline against the dark clouds. A chill dampness bathed Soliman’s brow, and pallid cheeks; his staring eyes devoured space. The queen made her entrance, accompanied by her principal officers and servants, who mingled with those of the king.

During the evening the prince appeared preoccupied; Balkis was cold, and adopted a nigh ironic tone: she knew that Soliman was in love. The supper was silent; the king’s eyes, furtive or affectedly averted, seemed to flee those of the queen, which, alternately lowered or raised by languid and self-contained fire, revived in Soliman illusions of which he wished to remain master. His absorbed air denoted some deeper design. He was a descendant of Noah, and the princess observed that, faithful to the traditions of that father of the vine, he sought wine to bolster the resolution which he lacked. The courtiers having withdrawn, his mutes replaced the prince’s officers; and, as the queen was served by her own people, she substituted, for her Nubians, Sabaeans to whom the Hebrew language was unknown.

— ‘My lady,’ said Soliman-Ben-Daoud gravely, ‘an explanation is necessary between us.’

— ‘My dear lord, our wishes are in accord.’

— ‘I had thought that, faithful to the word she had given, the princess of Sheba, more than a mere woman, was a queen....’

— ‘On the contrary,’ interrupted Balkis sharply, ‘I am more than a queen, my lord, I am a woman. Who is not subject to error? I believed you wise; then I believed in your love.... it is I who suffer the crueller disappointment.’

She sighed.

— ‘You know only too well that I love you,’ replied Soliman, ‘otherwise, you would not have abused your power, nor trampled underfoot a heart that must, in the end, rebel.’

— ‘I intended to reproach you, likewise. It is not I that you love, my lord, it is the queen. And, to be frank, am I of such an age as to aspire to a marriage of convenience? Yes, I wished to sound your soul: more sensitive than the queen, the woman, setting aside reasons of state, sought to enjoy her power: to be loved, such was her dream. Delaying the hour in which the promise, suddenly surprised from her, might be fulfilled, she put you to the test; she hoped you would seek to conquer only her heart, but she was mistaken; you proceeded further, by summons, by threats; you employed political artifice with my servants, and already you are more their sovereign than I am myself. I hoped for a husband, a lover; I now fear I am gaining a master. You see, I speak with sincerity’.

— ‘If Soliman had been dear to you, would you not have excused those faults caused by his impatience to belong to you? But no, your thoughts saw in him only an object of hatred, it is not for him that...’.

— ‘Stop there, my lord, and do not add offence to those suspicions that have wounded me. Mistrust rouses mistrust, jealousy intimidates the heart, and, I fear, the honour you wish to show me would cost my peace of mind and my freedom dear.’

The king remained silent, not daring, for fear of losing all, to commit himself further based on the word of a vile and perfidious spy.

The queen continued, with familiar and charming grace:

— ‘Listen, Soliman; be true to yourself, be kind. My illusions are still dear to me ... my spirit is daunted; yet I feel it would be sweet to be reassured.’

— ‘Ah! How you would banish all care, Balkis, if you could but read this heart where you reign undivided! Let us forget our suspicion; consent at last to my happiness. Fatal is the role of kings! Why am I not a mere Arab of the desert, kneeling at the feet of Balkis, the daughter of shepherds!’

— ‘Your wish accords with mine, and you have understood me. Yes,’ she added, bringing her face, at once open and passionate, close to the king’s. ‘yes, it is the austerity of an Israelite marriage that chills and frightens me: love, love alone would have drawn me, if....’

— ‘Yes?... Complete your utterance, Balkis: the tone of your voice penetrates me and sets me ablaze.’

— ‘No, no.... What am I saying, what has overcome me so suddenly?... These sweet wines are perfidious, and agitate me.’

Soliman made a sign: the mutes and the Nubians filled the cups, and the king emptied his in one gulp, observing with satisfaction that Balkis did the same.

— ‘It must be admitted,’ continued the princess cheerfully, ‘that marriage, according to the Jewish rite, was not established for the union of kings with queens, and demands unfortunate preparations.’

— ‘Is that what renders you uncertain?’ asked Soliman, gazing at her with eyes which were full of a certain languor.

— ‘Do not doubt it. Not to mention the inconvenience of fasting which make one ugly, is it not painful to deliver one’s hair to the shears, and to be wrapped in a headdress for the rest of one’s days? In truth,’ she added, displaying her magnificent ebony tresses, ‘I could not bear to lose such rich finery.’

— ‘Our women,’ objected Soliman, ‘are at liberty to replace their hair with tufts of pleasantly curled cockerel feathers. (Author’s note: in the East, even today, married Jewish women are obliged to substitute feathers for their hair, which must be trimmed to ear level, and hidden beneath a headdress).

The queen smiled with some disdain.

— ‘Moreover,’ she added, ‘in your country, the man purchases the woman like a slave or a servant; she must even offer herself humbly at her fiancé’s door. Finally, religion has little to do with a marriage contract which is similar to those drawn up in the marketplace, while the man, on receiving his companion, extends his hand to her and says to her: Mekudeshet-li; in Hebrew: ‘You are consecrated to me.’ Moreover, you have the power to repudiate her, to betray her, and even to have her stoned on the slightest pretext.... As much as I might be proud of being beloved by Soliman, I would dread marrying him.’

— ‘Beloved,’ cried the prince, rising from the sofa on which he reclined, ‘beloved, you! Never did a woman exercise a more absolute empire? I am annoyed: you appease me on whim; sinister preoccupations trouble me: I strive to banish them. You deceive me: I sense it, and conspire with you to condemn poor Soliman...’

Balkis raised her cup above her head, turning away with a voluptuous movement. The two slaves filled the tankards and withdrew.

The banqueting hall remained deserted; the light of the lamps, dimming, cast mysterious gleams over Soliman, pale, with burning eyes, and quivering and discoloured lips. A strange languor took possession of him: Balkis contemplated him with an equivocal smile.

Suddenly he remembered... and raised himself on his couch.

— ‘Woman,’ he cried, ‘trifle no longer with a king’s love.... The night protects us with its veils, mystery surrounds us, a fierce flame fills my whole being; rage and passion intoxicate me. This hour belongs to me, and, if you are sincere, you will no longer rob me of a happiness so dearly purchased. Reign, in freedom; but do not reject a prince who gives himself to you, whom desire consumes, and who, at this moment, would dispute for you with the powers of hell.’

Confused and palpitating, Balkis replied, lowering her eyes:

— ‘Give me time to gather myself; this language is new to me....’

— ‘No!’ interrupted Soliman, in delirium, as he emptied the cup from which he drew such boldness. ‘No, my temperance is at an end. It is a question for me of life or death. Woman, you shall be mine, I swear it. If you deceive me... I will be avenged; if you love me, eternal love will win my pardon.’

He stretched out his hands to embrace the queen; but grasped only a shadow; she had withdrawn, gently, and the arms of Daoud’s son fell back heavily. His head bowed; he remained silent, then, suddenly starting, raised himself.... His astonished eyes dilated with an effort; he felt desire expiring in his breast, while strange forms wavered above his head. His dulled, pallid face, framed by his black beard, expressed a vague terror; his lips parted without articulating a sound, and his head, weighed down by his turban, fell back against the cushions of the divan. Bound by invisible and heavy bonds, he attempted to shake them from his thoughts, while his limbs no longer obeyed the imagined effort.

The queen approached, slowly and gravely; in terror, he saw her standing, her cheek resting on the folded fingers of her left hand, while her right supported her left elbow. She watched him, he heard her speak and say:

— ‘The narcotic is working....’

Soliman’s dark pupils flickered in the white sockets of his large sphinx-like eyes, and he remained motionless.

— ‘There’, she continued, ‘I obey, I yield, I am yours!’

She knelt down and touched Soliman’s icy hand; he let out a deep sigh.

— ‘He hears, still...’ she murmured. ‘Listen, King of Israel, you who impose love at your whim, through the servitude and betrayal of others. Listen! I escape your power. But, if the woman abuses you, the queen has not deceived you. I love, though it is not you; fate debarred me from loving you. Born of a lineage superior to yours, I am obliged to obey the genies who protect me, and choose a husband of my own blood. Your power must bow before theirs; forget my name and face. May Adonai choose a fitting companion for you. He is great and generous: has He not given you wisdom and repaid you well for your services on this occasion? I abandon you to Him, and withdraw from you the idle support of the genies you disdain, and that you know not how to command....’

Balkis, then seized the finger on which she saw the talisman gleaming that she had gifted Soliman, and prepared to take up the ring; but the hand of the king, who was barely breathing, contracted with a sublime effort, closed tightly, and left Balkis attempting to reopen it in vain.

She was about to speak again, when Soliman-Ben-Daoud’s head fell back, the muscles in his neck relaxed, his mouth opened slightly, and his half-closed eyes grew dim; his spirit had fled to the land of dreams.

All were asleep in the palace of Millo, except the servants of the Queen of Sheba, who had lulled their guest to sleep. In the distance thunder rumbled; the black sky was furrowed with lightning-flashes; a raging storm blew the rain over the mountain slopes.

An Arabian steed, black as the tomb, awaited the princess, who gave the signal to depart, and soon the procession, turning along the ravine below the hill of Zion, descended into the valley of Jehoshaphat. They forded the Kidron, which was already swelling with rainwater to aid their escape; and, with distant Mount Tabor, crowned with flashes of lightning, to their left, they reached the corner of the garden of the Mount of Olives, and the hilly road to Bethany (al-Eizarya).

‘Let us follow this road.’ the queen told her guards. ‘Our horses are agile; our people are striking camp now, and already are in motion towards the Jordan. We shall meet with them again at the second hour of the day beyond the Salt Lake (the Dead Sea), from whence we may attain the pass through the Arabian mountains.’

And, loosening the reins of her mount, she smiled at the storm, knowing she shared the unfortunate weather with her dear Adoniram, doubtless wandering the road to Tyre.

As they entered the path to Bethany, a flash of lightning revealed a group of men, crossing the road in silence, who halted, stupefied, at the sight of this procession of ghosts riding amidst the darkness.

Balkis and his retinue passed before them, and one of the guards, having ridden forward, recognising them, murmured in a low voice to the queen:

— ‘Those three men are bearing away a corpse wrapped in a shroud.’

Chapter 12: Machbenach (Mahabon)

During the pause which followed this portion of the narrative, the audience were agitated by contrary ideas. Some refused to accept the tradition enunciated by the narrator. They maintained that the Queen of Sheba had a son by Soliman, and no other. The Abyssinian especially believed his religious convictions attacked by the suggestion that his sovereign rulers were the descendants of a mere artisan.

— ‘You lie,’ he shouted at the rhapsodist. ‘The first emperor of Abyssinia was Menelek, and he was the true son of Soliman and Balkis-Makeda. His descendant still reigns over us in Gondar.’

— ‘Brother,’ said a Persian, ‘let us hear the ending, or you will be ejected as happened the other night. This legend in our view is orthodox in its elements, and if your little Prester John of Abyssinia insists that he is descended from Soliman, we will accept that it was via some black Ethiopian, and not through Queen Balkis, whose skin was of our colouring.’ (Author’s note: the present emperor of Abyssinia is even now said to be descended from the Queen of Sheba. He is both sovereign and pope: he has always been called Prester John. His subjects today call themselves ‘Christians of Saint John’)

The café owner interrupted the furious reply on the Abyssinian’s lips and, with difficulty, restored calm.

The storyteller continued his tale:

— While Soliman had been welcoming the princess of the Sabaeans to his mansion, a man passing over the heights of Mount Moriah, was looking thoughtfully at the twilight fading in the clouds, and the torches like starry constellations dispelling the shade about Millo. His thoughts were of his beloved, as he addressed his farewell to the hills of Jerusalem, and the banks of the Kidron, which he was never to revisit.

The heavens lowered, and the sun, setting, had left the Earth to darkness. At the sound of hammers sounding the summons on bells of brass, Adoniram, tearing himself from his thoughts, traversed the assembled crowd of workmen; and, so as to preside over their payment, he entered the Temple, the eastern door of which he half-opened, and placed himself at the foot of the pillar named Jachin.

Lighted torches below the peristyle sparked as they received a few drops of warm rain, to the caress of which the panting workers happily offered their breasts.

The crowd were numerous; and Adoniram, besides his accountants, had at his disposal those men appointed to distribute their pay to the various orders. Distinguishing between the three hierarchical degrees was achieved by virtue of the passwords which replaced an exchange of hand-signals which would have occupied too great a time. Each man’s salary was delivered to him on his pronouncing the password.

The watchword of the apprentices had previously been ‘Jachin’ the name of the first of the bronze pillars (see the Bible ‘Kings III:7’); the watchword of the other workmen, ‘Boaz’, the name of the second pillar; the word of the masters was ‘Jehovah’.

Queuing in rows, by category, the workers presented themselves at the counters, and before the stewards, presided over by Adoniram, who touched their hand, and to whom they uttered the password in a low voice. On this final day, the password had been changed. That of the apprentices was ‘Tubal-Cain’; that of the workmen, ‘Shibboleth’ (see the Bible ‘Judges XII:6’); and that of the masters, ‘Giblim’ (the Giblim were the stonecutters who worked on the Temple, see the rites of Freemasonry).

Little by little the crowd thinned, the enclosure became deserted, and, the last workmen having withdrawn, it was seen that not all had attended, since there were still coins in the chests.

— ‘Tomorrow,’ said Adoniram, ‘you will issue a roll-call, and establish whether there are any sick workers, or if death has visited any of them.’

As soon as everyone had left, Adoniram, vigilant and zealous until the last, took a lamp, and made his rounds of the deserted workshops and the various quarters of the Temple, according to his custom, in order to ensure the execution of his commands, and the quenching of the lights. His steps echoed sadly on the flagstones; once again, he contemplated his creations, and stopped for a long time in front of a group of winged cherubs, the last work of the young Benoni.

— ‘Dear child!’ he murmured with a sigh.

His pilgrimage complete, Adoniram found himself in the great hall of the Temple. The darkness intensified about the light from his lamp, which spread in reddish volutes, marking the high ribs of the vaults, and the walls of the hall, from which one left by three doors facing north, west and east.

The first, that of the North, was reserved for the people; the second gave passage to the king and his warriors; the eastern gate was that of the Levites; the bronze pillars, Jachin and Boaz, were distinguishable beyond the third.

Before leaving by the western gate, the one nearest him, Adoniram cast his gaze upon the dark depths of the hall, and his imagination, struck by the numerous statues which he had just contemplated, conjured up in the shadows the phantom of Tubal-Cain. His fixed gaze tried to pierce the darkness; but the chimera grew as it faded, reached the roofs of the temple and vanished into the depths of the walls, like the shadow cast by a man departing who is lit by a torch. A plaintive cry seemed to resound beneath the vaults.

Then Adoniram turned away, preparing to leave. Suddenly a human form detached itself from the pilaster, and in a fierce tone said to him:

— ‘If you wish to leave, give the masters’ password!’

Adoniram was unarmed; the object of all respect, and accustomed to commanding with a sign, he gave not a thought to defending his sacred person.

— ‘Unhappy man!’ he replied, recognising his companion Methousael, ‘Depart!’ You will be received among the masters only when treason and crime are honoured! Flee with your accomplices before the justice of Soliman falls upon you.’

Methousael, on hearing this, raised his hammer with vigour, which fell with a crash on Adoniram’s skull. The artist staggered, dazed; by an instinctive movement, he sought to exit by the second door, that of the north. There stood the Syrian Phanor, who said to him:

— ‘If you wish to leave, give the masters’ password!’

— ‘You have not fulfilled the requisite seven years of labour!’ Adoniram replied in a faint voice.

— ‘The password!’

— ‘Never!’

Phanor, the mason, thrust his chisel into Adoniram’s side; but failed to repeat the blow, since the architect of the Temple, roused by the pain, flew like a bolt to the eastern Gate, to escape his assassins.

It was there that Amrou the Phoenician, a companion among the carpenters, was waiting to shout at him in turn:

— ‘If you wish to leave, give the masters’ password!’

— ‘That is not how I learned it;’ uttered Adoniram, exhausted, and with difficulty; ‘ask him who sent you.’

As he struggled to escape, Amrou plunged the point of his compass into his heart.

It was at this moment that the storm broke, signalled by a loud clap of thunder.

Adoniram was lying on the pavement, his body covering three flagstones. At his feet the murderers were gathered, hands joined.

— ‘The man was tall,’ Phanor murmured.

— ‘He will occupy no larger a space in the tomb than you,’ said Amrou.

— ‘May his death fall upon Soliman-Ben-Daoud!’

— ‘Let us lament on our own behalf;’ replied Methousael, ‘we possess a royal secret. Let us erase all evidence of the murder; rain is falling; the night is dark; Iblis protects us. Let us drag his remains far from the city, and entrust them to the earth.’

So, they wrapped the body in a long apron of white leather, and, lifting him in their arms, descended noiselessly to the edge of the Kidron, and headed for a solitary hill beyond the road to Bethany. As they reached it, troubled, and shuddering deeply, they suddenly found themselves in the presence of a cavalry escort. Crime engenders fear, they halted; those who flee are timid ... it was at this very moment that the Queen of Sheba passed in silence before the terrified assassins who were bearing away the remains of her husband Adoniram.

They advanced further, and dug a hole in the ground to bury the artist’s body. After which, Methousael, tearing up a young acacia stem, planted it in the fresh soil beneath which their victim lay.

Meanwhile, Balkis journeyed through the valley; lightning rent the skies, and Soliman slept.

His state was crueller, since he was obliged to wake.

The sun had completed its circuit before the lethargic effect of the potion he had drunk ceased. Tormented by painful dreams, he was troubled by visions, and it was with a violent shock that he returned to the realms of life.

He arose, astonished; his wandering eyes searching to re-establish their master’s rational thought; finally, he remembered....

The empty cup stood before him; the queen’s last words were in his thoughts: she was no longer there and he felt troubled; a ray of sunlight flickering, teasingly, across his brow made him shudder; he divined all and let out a cry of fury.

He enquired in vain: no one had seen her leave; her entourage had disappeared over the plain; only traces of her camp could be found.

— ‘This, then,’ cried Soliman, casting an irritated glance at the high priest Zadoc, ‘this is the aid your God lends to his servants! Is this what He promised? He delivers me like a plaything to the spirits of the abyss, and you, his imbecile minister, who reigns in his name, given my impotence, you have abandoned me, without foreseeing anything, without preventing anything! Who will grant me winged legions to attack this perfidious queen? Genies of earth and fire, rebellious powers, spirits of the air, will you not obey me?’

— ‘Blaspheme not;’ cried Zadoc, ‘Jehovah alone is great, and he is a jealous God.’

In the midst of this disorder, the prophet Ahias of Shiloh appeared, sombre, fearsome, and inflamed with divine fire; Ahias, poor yet dreaded, who was naught, except in spirit. It was to Soliman that he addressed himself:

— ‘God marked the forehead of Cain the murderer, and said, “Whoever makes an attempt on the life of Cain will be punished seven times over.” And of Lamech, who was descended from Cain, having shed blood, it is written, “The death of Lamech shall be avenged seventy times sevenfold.” Now listen, O king, to what the Lord instructs me to say: “Whoever sheds the blood of Cain and Lamech will be punished seven hundred times sevenfold.”

Soliman bowed his head; he thought of Adoniram, knowing that the latter had been executed at his command, and remorse brought from him this cry:

— ‘Unfortunate man! What have you done? I did not tell them to slay him.’

Abandoned by his God, at the mercy of the genii, scorned, betrayed by the princess of the Sabaeans, Soliman, in despair, lowered his gaze to his feeble hand, on which the ring he had received from Balkis still shone. That talisman roused in him a glimmer of hope. Once alone, he turned its bezel towards the sun, and saw all the birds of the air gather to him, all except Hud-Hud, the magical hoopoe. He called her three times, forced her to obey him, and ordered her to lead him to the queen. The hoopoe instantly resumed her flight, and Soliman, who was stretching out his arm towards her, felt himself lifted from the ground and borne into the air. Fear seized him, he drew his arm back and immediately regained his footing on the ground. As for the hoopoe, she crossed the valley and landed, on top of a mound, on the frail stem of an acacia that Soliman could not force her to abandon.

Seized by vertigo, King Soliman thought of raising innumerable armies to bring fire and blood to the kingdom of Sheba. He shut himself, alone, to curse his fate and evoke the spirits. An Afreet, a genie of the abyss, was forced to serve him and follow him into solitude. To forget the queen and to assuage his fatal passion, Soliman sought out foreign women from every land, whom he married according to impious rites, and who initiated him in the idolatrous worship of images. Soon, to sway the genies, he populated the high places and built, not far from Mount Tabor, a temple to Moloch.

Thus, was verified the prediction that the shade of Enoch, amidst the realm of fire, had made to his son Adoniram, in these terms: ‘You are destined to avenge us, and the Temple that you raise to Adonai will cause the downfall of Soliman.’

But the King of the Israelites did even more, as the Talmud teaches; for, the rumour of Adoniram’s murder having spread, the people rose up, demanding justice, and the king ordered that nine masters should investigate the death of the artist, and seek out his corpse.

Seventeen days had passed: their searches in the vicinity of the temple had proved fruitless, and the masters now scoured the countryside, as yet in vain. One of them, overcome by the heat, having sought to cling, in order to stand upright more easily, to an acacia branch, from which a bright and unknown species of bird had flown, was surprised to find that the whole sapling gave way under his hand, and was readily uprooted from the ground. It had been planted recently, and the master, astonished, called out to his companions.

Immediately the nine dug with their hands and revealed the grave beneath.

Then one of them said to his brothers:

— ‘The culprits may have sought to wrest from Adoniram the masters’ password. I fear they may have succeeded in doing so, would it not be wise to change it?’

— ‘What word shall we adopt?’ asked another.

— ‘If we find that, indeed, our master’s body lies here,’ answered a third, ‘the first word any one of us pronounces shall serve as the password; it will eternalise the memory of this crime, and of the oath we hereby swear to avenge it, we or our descendants, on his murderers, and on their most remote posterity.’

The oath was sworn; their hands joined over the grave, and they dug again with ardour.

The corpse was recognised as that of Adoniram, and one of the masters took the finger of its one hand, and found that the skin remained in his own; the same result was obtained by a second; while the third seized the corpse by the wrist in the manner in which masters greet a companion, and the skin separated from the bone again; whereupon, he cried out: ‘Machbenach!’ which means: ‘The flesh leaves the bone!’

They immediately agreed that this word would henceforth be the watchword and rallying cry of the avengers of Adoniram, and God’s justice decreed that this word should, for many centuries, rouse the people against the line of kings.

Phanor, Amrou, and Methousael had fled; but, recognised as disloyal brothers, they perished at the hands of the workmen, in the kingdom of Maacah, ruler of the country of Gath (north-east Philistia), where they hid under the names of Hoben, Sterkin, and Oterfut (see for this, and much of the other material, the rites of Freemasonry).

Nevertheless, the corporations, by secret inspiration, still continued to pursue their disappointed vengeance on Abiram or the murderer.... and Adoniram’s descendants remained sacred to them; for, many centuries after, they still swore by The Sons of the Widow; thus, they designated the line of Adoniram and the Queen of Sheba.

On the express order of Soliman-Ben-Daoud, the illustrious Adoniram was buried beneath the very altar of the Temple which he had erected; which is why, in the end, Adonai abandoned the ark of the Israelites, and reduced Daoud’s successors to servitude.

Eager for power and honours, greedy in his voluptuousness, Soliman wed five hundred women, and forced the genies, reconciled to him at last, to serve his designs against the neighbouring nations, by use of the famous ring, created by Irad, father of the Cainite, Maviael and possessed then by Jared the patriarch, his son Enoch (Idris), who employed it to command the stones (see ‘The Book of Enoch’), and by Nimrod, who bequeathed it to Saba, father of the Himyarites.

Solomon’s ring subdued the Djinns (the genies), the winds, and all creatures. Sated with power, and with his pleasures, the wise man constantly repeated the sentence:

— ‘Eat, love, drink; the rest is vanity.’

And yet, strange contradiction, he was unhappy! For the king, corrupted by materiality, aspired to become immortal....

By his artifice, and with the help of profound knowledge, he sought to achieve this by surviving in a certain material state: in order to purify his body of mortal elements, without dissolving it wholly, it was necessary that he should sleep the sleep of the dead, sheltered from all harm, from all corrupting forces, for two hundred and twenty-five years; after which, the exiled soul would return to its fleshly envelope, rejuvenated, and at that stage of flourishing virility whose blossoming attends on the age of thirty-three.

Now old and decrepit, once he perceived, by the decay of his physical powers, the signs of an approaching end, Soliman ordered the genies he had enslaved to build for him, within the mountain of Kaf, an inaccessible palace, at the centre of which was erected a massive throne of gold and ivory, supported on four pillars made from the vigorous trunk of an oak-tree.

It was there that Soliman, Prince of the Djinns, resolved to spend this period of trial. The last days of his life were employed in conjuring, by magic signs, mystical words, and the power of the ring, all creatures, elements, and substances endowed with the properties of decomposing matter. He summoned the clouds’ vapour, the earth’s humidity, the rays of the sun, the breath of the winds, the butterflies, moths and larvae. He summoned the birds of prey, the bat, the owl, the rat, the horse-fly, the ant, and those species of insects that crawl or gnaw. He summoned the metals; he summoned gemstones, alkalis and acids, and even the emanations of plants, to his conjuring.

These arrangements made, once he had made sure his body his body was far from all the agents of destruction, the pitiless ministers of Iblis, he had himself transported one last time to the heart of the mountain of Kaf, and, gathering the genies, imposed immense tasks on them, enjoining them, under threat of the most terrible punishments, to guard his sleep, and watch over him.

Then he seated himself on his throne, to which he firmly bound his limbs, which gradually grew cold; his eyes grew dim, his breathing ceased, and he entered a deathlike sleep.

The Djinns, his slaves, continued to serve him, to execute his orders and prostrate themselves before their master, whose awakening they awaited.

The winds respected his face; the larvae from which worms emerge shunned him; the birds, and predatory quadrupeds were obliged to avoid his body; the water diverted its vapours, and, by the power of his conjurations, his flesh remained intact for more than two centuries.

Soliman’s beard grew and spread down to his feet; his nails pierced the leather of his gloves, and the golden fabric of his shoes.

But how could limited human wisdom aspire to the Infinite? Soliman had neglected to summon one of the insects, the tiniest of all.... He had forgotten the humble termite.

The termite advanced secretly... invisibly.... it attached itself to one of the pillars that supported the throne, and gnawed at it slowly, slowly, without ceasing. The most subtle sense of hearing would not have detected the scratching of this little atom, which left behind it, each year, grains of fine sawdust.

It laboured for two hundred and twenty-four years.... after which time the corroded pillar suddenly gave way under the weight of the throne, which collapsed with a tremendous crash. (Author’s note: according to the Orientals, the powers of nature have no action except by virtue of a mutually agreed contract. It is this concord of all beings which engenders the power of Allah himself. Note the relationship between this tale of the termite, triumphing over the ambitious conjurations of Soliman, and the tale in the Eddas, relating to Balder. Odin and Freya similarly summoned all beings to their conjurations, so that all would respect the life of Balder, their child. They forgot to summon mistletoe from the oak-tree, and this humble plant was what brought death to that son of the gods. This is why mistletoe was considered sacred in the Druidic religion, which followed that of the Scandinavians.)

It was the termite that defeated Soliman, and the first that knew of his death; for the king of kings, hurled to the flagstones, failed to awaken.

Then the humiliated genies recognised their errant state, and regained their freedom.

— Here ends the history of the mighty Soliman-Ben-Daoud, an account which should be received with respect by true believers, because it was written, in summary form, by the sacred hand of the Prophet, in the thirty-fourth sura, Saba, of the Koran, the mirror of wisdom and the fount of truth.

The storyteller had finished his tale, which had taken him nearly two weeks to tell. I have feared to lessen its interest by interspersing accounts of what I had been able to observe of Instanbul in the intervals between the evening sessions. Nor have I related a few short stories interspersed here and there, according to custom, either at times when the audience was not so numerous, or to divert attention from some dramatic adventure. The cafedjis often go to considerable expense to secure the assistance of well-known narrators. As a session never lasts more than an hour and a half, they may well make an appearance in several cafés on any given night. They also perform sessions in the harem, when the husband, having assured himself of the delights of a particular tale, wishes to have his family share in the pleasure he has experienced. Prudent people address themselves, to secure a visit, to the syndic of the corporation of storytellers, who are called the Khasideans; for it sometimes happens that storytellers of bad faith, dissatisfied with the takings of the café, or the remuneration offered for a domestic performance, vanish in the midst of an interesting episode, leaving their listeners to regret not hearing the end of the tale.

I was very fond of the café frequented by my Persian friends, because of the varied nature of its regulars and the freedom of speech that reigned there; it reminded me of the Café of Surat as described by the good Bernardin de Saint-Pierre. One finds, in fact, far more tolerance in these cosmopolitan gatherings of merchants from the various countries of Asia, than in cafés composed purely of Turks or Arabs. The story that was being related was discussed, after each session, among the various groups of customers, for, in an Oriental café, the conversation is never general, and, except for the observations of the Abyssinian, who, as a Christian, seemed to abuse somewhat Noah’s juice of the grape, no one appeared to doubt the principal facts of the story. They are, in fact, in conformity with the general beliefs of the Orient; only, one finds there something of that spirit of dissent which stirs among the Persians and Yemeni Arabs. Our storyteller belonged to the sect of Ali (that of the Sh’ia), which is, so to speak, the Catholic tradition of the East, while the Turks, who rallied to the sect of Umar (that of the Sunni), rather represented a kind of Protestantism, which dominated over the former due to the subjugation of the more southerly populations.

I returned to Ildiz-Khan, preoccupied with the singular details of the legend, and principally with the picture which had just been given to us of the posthumous fall of Solomon. Above all, I pictured to myself the interior marvels of the mountain of Kaf, of which Oriental poems so often speak, in accord with the information I obtained from my companions. Kaf is the mass of rock constituting, so to speak, the internal substance of the globe, and the various mountain ranges which appear on the surface are only its extended branches. The Atlas Mountains, the Caucasus, and the Himalayas represent its most powerful buttresses; ancient authors place yet another branch beyond the western seas, in a region which they call Yni-Dunya, the New World, and which suggests Plato’s Atlantis, if one assumes they had no idea of the existence of the Americas.

It is probable that the scene in which Solomon’s pride was confounded — according to the Koran — took place in the Silver Gallery, hollowed out, at the centre of the mountain, by the genies, wherein could be seen the statues of the forty Solimans or emperors who governed the earth in the pre-Adamite era, as well as the painted figures of all the rational creatures who had inhabited the globe before the creation of the people of clay. Most of them revealed monstrous aspects, heads and arms in vast numbers, or bizarre forms approaching those of animals; which clearly suggests the primitive legends of the Hindus, Egyptians, and Pelasgians.

The pre-Adamite sovereigns, forty in number, who, according to legend, each reigned for a thousand years, reminded me of a hypothesis of the scholar Jean-Antoine Letronne, which I heard him propound in his lectures, that dates the antiquity of the world to about forty thousand years before the presumed creation of Adam. He gave as evidence the regular retreat of the sea from the shores of Egypt, and, also certain layers of rock corresponding in number to the annual flooding of the Nile. Georges Cuvier’s research would also lead to similar conclusions, if that scholar had not been so eager to tie his discoveries to the Biblical account.

In any event, it is impossible to absorb the novels or poems of the Orient without persuading oneself that there existed a long series of unique peoples before Adam whose last king was Gian ben Gian (Jann ibn Jann). Adam represented, for the Orientals, merely a new race, kneaded and formed from a particular bed of clay by Adonai, the God of the Bible, who acted, in this role, like Prometheus, the Titan, who animated by means of divine fire a lineage disdained by the Olympians, to whom the world had, until then, belonged.

But, enough of legend: I merely wish to shed a little light on the magical aspects of the tale told above; but the story is a ray of brightness lost amidst the shadows, which, according to Milton’s expression, only serves to make the darkness visible.

The Lesser Bayram (Eid al-Fitr)

Chapter 1: The ‘Eaux-Douces d’Asie’ (Küçüksu Deresi, the Sweet Waters of Asia)

We had not abandoned our idea of visiting, one Friday, the Eaux-Douces d’Asie. This time, we chose the rough track that led to Buyukdéré.

On the way, we stopped at a country house, which was the residence of Boghos Effendi, one of the senior employees of the Sultan. He was an Armenian, who had wed a relative of those Armenians with whom my friend was staying. A garden decorated with rare plants fronted the entrance to the house, and two very pretty little girls, dressed like miniature Sultanas, were playing among the flowerbeds under the supervision of a black African nurse. They came to embrace the painter, and accompanied us into the house. A lady, in Levantine costume, came to receive us, and my friend greeted her with:

— ‘Kalimera, kokona!’ (‘Good day, madam!’)

He addressed her in Greek, since she was of that nation, though married to an Armenian.

One is always embarrassed to have to speak, in an account of one’s travels, of people who welcome European travellers as hospitably as possible; travellers, that is, who seek to reveal to their own country the truth regarding matters foreign to it; I speak of social groups sympathetic to ours, upon whom Frankish civilisation casts rays of light. In the Middle Ages, our world received everything from the East; now we seek to return those powers with which it has endowed us to the mutual source of our civilisation, to revive the greatness of the universal motherland.

The fair name of France is dear to these distant nations; it is our future strength; it is what will allow us to await whatever the tired diplomacy of European governments may achieve.

We may say to ourselves, when describing such a country, what Racine said in his second preface to Bajazet: ‘They have completely different manners and customs.’ But surely it is permissible to be thankful for as warm a reception as our Armenian hosts gave us? More alive to our ideas than the Turks, they serve, so to speak, as a means of gaining the good will of the latter, towards whom France as a nation has always been particularly friendly.

I confess that it was a great delight to me to find, after a year’s absence from my country, a completely European family home, except for the women’s costumes, which, fortunately for local colour, were in keeping with the latest fashions from Istanbul.

Madame Boghos had her granddaughters serve us refreshments; then we entered the main room, in which were several Levantine ladies. One of them sat down at the piano to play one of the most recent pieces from Paris: it was a courtesy that we greatly appreciated, and we admired her extracts from a new opera by Fromental Halévy.

Also, on the tables, there were newspapers, alongside volumes of poetry, and plays, by authors such as Lamartine and Victor Hugo. This seemed strange when one has recently arrived from Syria, yet is quite natural when you consider the fact that Constantinople consumes the literary and artistic works emerging from Paris almost as readily as does Saint Petersburg.

While we were looking through the illustrated books and albums, Monsieur Boghos returned; he wished us to stay for dinner; but, having planned to go to the Eaux-Douces, we merely thanked him. He then wished to accompany us to the shore of the Bosphorus.

We remained some time on the bank waiting for a caique. While walking along the quay, we saw approaching in the distance a man of majestic appearance, of a complexion similar to that of a mulatto, magnificently dressed in the Turkish style, not in the costume of the Reform, but dressed in a traditional fashion. He stopped when he saw Monsieur Boghos who greeted him respectfully, and we left them to talk together for a moment. My friend warned me that he was a great personage, and that we must take care to make a graceful salamalek, when he left us, by putting our hand to our chest and mouth, according to oriental custom. I did so according to his instructions, and the mulatto responded very graciously.

It was not the Sultan, whom I had already met.

— ‘Who is he?’ I said when he had departed.

— ‘He is the kislar-agha,’ the artist answered, admiringly, and also a little fearfully.

I understood all. The kislar-agha is the chief eunuch of the seraglio, the man most feared after the Sultan, and more so than even the First Vizier. I regretted not having become more intimately acquainted with this personage, who seemed, very polite moreover, though clearly convinced of his own importance.

Attachés finally arrived; we left Boghos Effendi, and a six-oared caique bore us towards the coast of Asia Minor.

It took about an hour and a half to reach the Eaux-Douces. We admired, on the coasts to right and left, the crenellated castles which guard Pera (Beyoğlu), Istanbul, and Scutari (Üsküdar) against incursion from Crimea or Trebizond via the Black Sea. These fortifications are Genoese, like those which separate Pera and Galata.

When we had passed the castles of Asia and Europe, our boat entered the basin of ‘Sweet Waters’ (formed by the Göksu and Küçüksu rivers). Tall grass, from which here and there wading-birds flew, bordered the mouth of the river (the Göksu) which reminded me somewhat of the last stretches of the Nile where its waters, nearing the sea, enter the lake of Pelusium. But, here, Nature, calmer, greener, more northern in mood, echoed the magnificence of the Nile Delta, much as Latin echoes Greek... by lessening its power.

We landed in a delightful meadow, traversed by watercourses. The woods, artfully thinned, cast shadow in places on the tall grass. A few tents, erected by traders in fruit and refreshments, gave the scene the appearance of one of those oases at which wandering tribes halt. The meadow was covered with people. The varied tints of their costumes enlivened the verdure like the bright colours of flowers scattered over a lawn in Spring. In the middle of the widest clearing, a fountain of white marble could be distinguished, having that form of a Chinese pavilion whose unique architecture is found everywhere in Constantinople.

The pleasure of imbibing fresh water has prompted the invention of the most charming constructions one could imagine. This was not a spring like that of Arnavutköy, where one must await the good pleasure of a saint, who causes the fount to flow only on his feast-day. That is fine for the giaours, who wait patiently for the miracle to allow them a drink of fresh water.... but at the fountain of the Sweet Waters of Asia, one does not have to suffer from such delay. I know not which Muslim saint makes the water, there, flow with an abundance and limpidity unknown to the Greek equivalent. I had to pay a para for a glass of this liquid; the journey there, in order to obtain it directly from its source, costing some ten piastres.

Carriages of all kinds, most of them gilded, and drawn by oxen, had brought the ladies of Scutari to the Sweet Waters. Near to the fountain only women and children could be seen, speaking, shouting, conversing amidst gestures, laughter, and mild teasing, in that Turkish language whose soft syllables resemble the cooing of birds.

Although the women are more or less hidden beneath their veils, they do not, however, seek to hide themselves in such a cruel manner as to thwart Frankish curiosity. The police regulations which command them, as often as possible, to wear thicker veils, to shield the infidels from any external features which might affect the senses, inspire in them a reserve which would not yield readily to any attempt at seduction.

The heat of the day was, at this hour intense, and we had found shade beneath an enormous plane-tree surrounded by rustic divans. We tried to sleep; but, for Frenchmen, sleeping at midday is well-nigh impossible. The artist, seeing that we could not sleep, told us a story.

It concerned the adventures of friend of his, a painter (Camille Rogier), who had arrived in Constantinople hoping to make his fortune, by producing daguerreotypes.

He looked for sites where there were the largest crowds, and one day he set up his photographic equipment beneath the shade of the trees at Eaux-Douces.

A child was playing on the grass: the artist had the good fortune to achieve a perfect image; then, in his joy at seeing such a successful take, he exhibited the plate before the onlookers, who are never lacking on such occasions.

The mother approached, prompted by natural curiosity, and was surprised to see her child so clearly reproduced. She believed it to be the result of magic.

The artist knew nothing of the Turkish language, so that he did not, at first, understand the lady’s compliments. But the African servant who accompanied her signalled to him. The lady had entered an araba, and was on her way to Scutari.

The painter grasped his daguerreotype box under his arm, something which is not easy to carry, and followed the araba for a few miles.

Arriving at the first houses belonging to Scutari, he saw the araba come to a halt some distance away, and the woman descended at an isolated kiosk which faced the sea.