Gérard de Nerval

Travels in the Near East (Voyage en Orient, 1843)

Part XVI: Ramadan Nights (Les Nuits Du Ramazan) – The Storytellers: Chapters 4 to 8

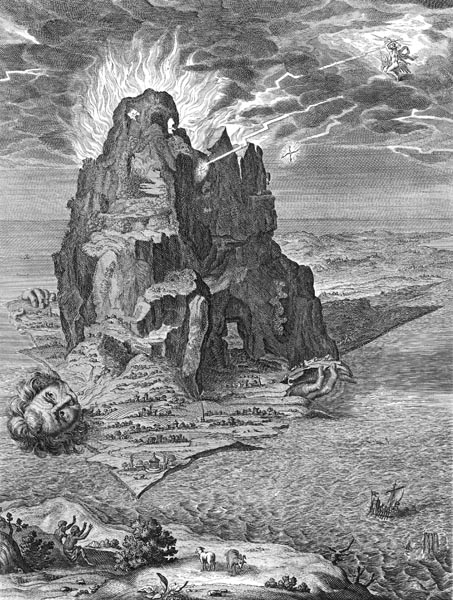

Enceladus below Etna, 1731, Bernard Picart

Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter 4: Millo.

- Chapter 5: The Sea of Bronze.

- Chapter 6: The Apparition.

- Chapter 7: The Subterranean World.

- Chapter 8: The Pool of Siloam.

Chapter 4: Millo

During the first pause of this next session, there was talk of the various emotions which the story had roused. One of the customers, who by his bluish sleeves could be recognised as a dyer, seemed not to share in the display of approval which had greeted the preceding scene. He approached the storyteller and said to him:

— ‘Brother, you announced that this story concerned all classes of worker, and yet I find that, so far, it is dedicated to the glory only of metal-workers, carpenters and stone-cutters.... if it fails to interest me further, I’ll not return, and many another will shun this café, likewise.’

The cafe owner frowned, and gazed at his storyteller with a look of reproach.

— ‘Brother,’ replied the storyteller, ‘there will be something for the dyers too.... I shall have occasion to speak of the good Hiram of Tyre, who distributed beautiful purple fabrics throughout the world, and who had been Adoniram’s patron....’

The dyer seated himself, once more, and the narration began again.

— It was at Millo, a place situated on the summit of a hill, from which one could see the valley of Jehoshaphat at its widest, that King Soliman proposed to celebrate the arrival of the Queen of the Sabaeans. Hospitality, enjoyed amidst the fields, seemed more cordial there: the freshness of the waters, the splendour of the gardens, the favourable shade cast by the sycamores, tamarinds, laurels, cypresses, acacias and terebinths awakened tender feelings in the heart. Soliman too was happy to show his pride in his rustic dwelling; and then, most sovereigns prefer to keep the people at a distance, and keep themselves to themselves than leave themselves and their peers open to the comments of the populace of their capital cities.

The green valley was dotted with white tombs overshadowed by pine and palm-trees: there lay the first slopes of the Valley of Jehoshaphat. Soliman said to Balkis:

— ‘What more worthy a subject of meditation for a king, than the spectacle of our common end! Here, beside you, queen, is pleasure, and happiness perhaps; over there, nothingness and mere oblivion.’

— ‘We rest from the fatigues of life in the contemplation of death.’

— ‘At this hour, my lady, I dread the latter; it parts one from another.... May I not learn too soon that it consoles also!’

Balkis glanced furtively at her host, and saw that he was truly moved. Softened by the evening light, Soliman seemed handsome to her.

Before entering the banqueting hall, the august guests contemplated the house in the twilight, breathing in the voluptuous scent of the orange trees which perfumed the depths of night.

The airy dwelling was constructed according to Syrian taste. Raised on a forest of slender columns, its openwork turrets and cedar pavilions, covered with bright woodwork, were outlined against the sky. The open doors revealed curtains of Tyrian purple, silken coverings woven in India, rosettes inlaid with multi-coloured gems, furniture carved from lemonwood and sandalwood, vases from Thebes, vases of porphyry and lapis-lazuli laden with flowers, silver tripods in which aloes, myrrh, and benjamin (benzoin) smoked, vines that embraced the pillars and were strung across the walls: that charming place seemed dedicated to love. But Balkis was wise and prudent: her reason protected her from the seduction of that enchanted abode, Millo.

— ‘It is not without timidity that I walk beside you through this little mansion,’ said Soliman, ‘since your presence honours it, it seems but humble to me. The cities of the Himyarites are doubtless richer.’

— ‘Not so, in truth; but, in our country, the smaller and more fragile columns, the openwork mouldings, the figurines, and the jagged bell-towers, are of marble. We execute in stone what you only carve in wood. Moreover, it is not through such vain fancies that our ancestors sought glory. They accomplished a work that will make their memory eternally blessed.’

— ‘What work is that? A tale of great enterprises exalts the mind.’

— ‘It must be confessed, first of all, that the happy, fertile country of Yemen was formerly arid and sterile. It received neither rivers, nor rain from the sky. My ancestors triumphed over Nature and created an Eden in the midst of the desert.’

— ‘Great Queen, tell me of these wonders.’

— ‘In the heart of the high mountain ranges which rise to the east of my kingdom, on a slope of which is situated the city of Marib, torrents meandered here and there, streams which evaporated into the air, were lost in abysses, and in the depths of valleys, before reaching the wholly arid plain. Through the labour of two centuries, our ancient kings succeeded in bringing together all these watercourses, on a plateau a number of miles in extent, where they dug a basin and created a lake, over which one can sail today, as over a gulf of the sea. It was necessary to support the steep cliffs with granite buttresses more solid than the pyramids of Giza, and cyclopean arches beneath which armies of horsemen and elephants could move easily. This immense and inexhaustible reservoir feeds, in silvery cascades, the aqueducts, and wide canals which, subdividing into numerous channels, carry the water across the plain, and irrigate half the provinces. We owe to this sublime work the rich crops from fertile fields, the numerous meadows, the age-old trees, and deep forests which are the wealth and charm of the sweet country of Yemen. Such, lord, is our ‘sea of bronze’, without deprecating yours, which is a delightful invention.’

— ‘A noble concept!’ cried Soliman, ‘and one I would be proud to imitate, if God, in his clemency, had not distributed to us the abundant and blessed waters of the Jordan.’

— ‘I crossed it yesterday on foot,’ replied the queen, ‘my camels were barely up to their knees in its stream.’

— ‘It is dangerous to overturn the natural order,’ pronounced the wise man, ‘and create, in spite of Jehovah, through artifice, a civilisation, with its commerce and industry, that condemns the populace to the brevity of human effort. Our Judaea is arid, it can feed no more inhabitants than it does, and what supports them is the natural produce of the soil and the climate. Should your lake, that basin carved amidst the mountains, be breached, should those cyclopean buttresses collapse — and a single day could bring about that misfortune! — your people, denied the tribute of its water, will die, consumed by the sun, devoured by famine, in the midst of those works of artifice.’

Seized by the obvious truth of this reflection, Balkis seemed pensive.

— ‘Indeed, already,’ continued the king, ‘already, those streams that run from the mountain-lake are scouring out ravines, freeing themselves from their prisons of stone, which they constantly undermine. The earth is subject to tremors, time uproots the rocks, the water seeps away. Moreover, burdened by such a weight of liquid, your magnificent basin, which was carved out before the lake was created, is impossible to repair. O queen! Your ancestors condemned the people to a future determined by a scaffolding of stone. Aridity would have made them industrious; they would have learned how to gain advantage from a land where they are doomed to perish, idle and dismayed, along with the first leaves of those trees whose roots the channels will one day cease to revive. We must not tempt God, nor correct His works. What He created was good.’

— ‘That maxim,’ replied the queen, ‘is born of a religion weakened by the shadowy doctrines of your priests. They seek nothing less than to prevent all effort, treat the people like children, and constrain human independence. Did God plough and sow the fields? Did God found cities, or build palaces? Did He place within our easy reach iron, gold, copper, all those metals that gleam throughout Soliman’s Temple? No. He endowed his creatures with genius, and activity. He smiles at our efforts, and our limited creations, but recognises the light of His spirit, illuminating ours. In believing Him to be a jealous god, you limit His omnipotence, you deify your own faculties, and render His mortal. O king! The prejudices displayed by your religion will one day hinder the progress of science, its developments prompted by genius, and, when men are diminished, they will reduce God to their own dimensions, and end in denying Him.’

— ‘Subtle,’ murmured Soliman with a bitter smile, ‘subtle, yet specious....’

The queen continued:

— ‘Do not sigh, thus, when my finger presses on your secret wound. You are alone in this kingdom, and you suffer: your views are noble, daring, yet the hierarchical constitution of this nation burdens your flights of imagination; you say to yourself, for they seem slight to you: ‘I shall leave to posterity only the statue of a king too great for so petty a people!’ As regards my own empire, it is otherwise.... my ancestors effaced themselves to aggrandise their subjects. Thirty-eight successive monarchs have spent their efforts on the lake and aqueducts of Marib: future ages will never know their names, while their labours will continue to glorify the Sabaeans; and, if ever the lake is breached, if the greedy earth reclaims it water, and the channels run dry, the soil of my homeland, fertilised by a thousand years of cultivation, will continue to produce; the great trees which shade our plains will retain humidity, and preserve their freshness, by shading the ponds, and fountains, and Yemen, won long ago from the desert, will retain until the end of time the sweet name of Arabia Felix.... If you had been freer, you would have brought glory to your people and happiness to humankind.’

— ‘I see to what you would have my spirit aspire.... It is too late; my people are wealthy: conquest or gold will provide what Judaea cannot; and, as for timber, I have prudently concluded a treaty with the king of Tyre; the cedars, the pines of Lebanon encumber my shipyards; our ships compete on the seas with those of the Phoenicians.’

— ‘You console yourself with displays of grandeur, through that paternal solicitude embodied in your method of government,’ said the princess with benevolent sadness.

This reflection was followed by a moment of silence; the deepening darkness hid the emotion imprinted on Soliman’s features, as he murmured in a low voice:

— ‘My spirit has merged with yours, and my heart follows.’

Somewhat troubled, Balkis cast a furtive glance around her; the courtiers had moved aside. The stars shone above their heads, scattering golden flowers amidst the foliage. Charged with the perfume of lilies, tuberoses, wisteria, and mandragoras, the nocturnal breeze sighed amidst the leafy branches of the myrtle-trees; the incense of the flowers had acquired a voice, the wind its perfumed breath; distant doves moaned; the sound of the waters accompanied the harmonies of nature; fireflies and starlit moths bore their gleams of light through the warm air which seemed full of voluptuous emotion. The queen felt herself seized by an intoxicating languor; the tender voice of Soliman penetrated her heart and held it in its spell.

Did Soliman please her; did she dream that she might yet love him? Ever since she had humbled him, she had found him an object of interest. But that sympathy, which had blossomed amidst the calm of reasoned conversation, mingled with gentle pity following a woman’s victory, was neither spontaneous nor enthusiastic. Mistress of herself, as she had been of the thoughts and impressions of her host, she was drifting towards love, if indeed it touched her at all, through friendship; and that path is long indeed!

As for the man, subjugated, dazzled, raised from rancour to admiration, from discouragement to hope, and from anger to desire, he had already received more than one wound, and, for a man, to love too soon is to risk his love being unrequited. Besides, the Queen of Sheba was reserved; her ascendancy had constantly dominated all, even the magnificent Soliman. The sculptor Adoniram had alone caught her attention, for a moment; she had not penetrated his character: her imagination had glimpsed a mystery there; but that lively curiosity of a moment had swiftly vanished. However, on seeing him for the first time, this strong woman had said to herself:

— ‘Now, there is a man!’

It may be, then, that her recent though fading impression of Adoniram had lowered the prestige of King Soliman in her eyes. What gave proof of it, was that once or twice, on the point of speaking about the artist, she restrained herself and changed the subject. (Author’s note: Adoniram was otherwise known as Hiram, a name that has been preserved by the mystical tradition. Adon is only a term of excellence, which means master or lord. This Hiram should not be confused with the king of Tyre who happened to bear the same name.)

However, David’s son was promptly ablaze: the queen was accustomed to such being often the case; he hastened to tell himself he was but following everyone’s example; yet he knew how to express himself with grace, the hour was propitious, Balkis was of the age that seeks love and, by virtue of the darkness, intrigued and tender.

Suddenly a host of torches cast red rays on the bushes, and supper was announced.

— ‘An unfortunate delay!’ thought the king.

— ‘A salutary diversion!’ thought the queen.

The meal was served in a pavilion built in the lively and fanciful taste of the peoples who dwelt on the banks of the Ganges. The octagonal room was illuminated with coloured candles, and lamps in which naphtha mixed with perfume burned; the light burst forth amidst shadowy sheaves of flowers. On the threshold, Soliman offered his hand to his guest, who put out her little foot, and quickly withdrew it in surprise. The floor was covered with a sheet of water in which the table, the divans, and the candles were reflected.

— ‘What deters you? Soliman asked in astonishment.

Balkis wished to show herself superior to fear; with a charming gesture, she lifted her dress and stepped forward, firmly. But her foot met a solid surface (compare the Koran: ‘Sura 27, An-Naml’).

— ‘O queen! You see,’ said the wise king, ‘that the most prudent may be mistaken when they judge by appearances only; I desired to astonish you, and I have at last succeeded.... You are stepping onto a floor of crystal.’

She smiled, with a shrug of her shoulders that was more graceful than admiring, perhaps regretting that none had known how to surprise her so before.

During the feast the king was gallant and eager to please; his courtiers surrounded him, and he reigned over them with such incomparable majesty, that the queen felt herself drawn to respect him. A solemn and rigid etiquette was observed at Soliman’s table.

The dishes were exquisite, and varied, but heavily loaded with salt and spices: never had Balkis tasted such salted food. She supposed that such was to the Israelites’ taste: she was therefore not a little surprised to notice that these people who braved such strong seasoning abstained from drink. No cupbearers; not a drop of wine or mead; not a single drinking-vessel on the table.

Balkis’ lips were burning, her palate was dry, and, as the king did not imbibe, she did not dare ask to do so: the prince’s dignity imposed itself upon her.

The meal over, the courtiers gradually dispersed, vanishing into the depths of a half-lit gallery. Soon the beautiful queen of the Sabaeans found herself alone with Soliman, now more gallant than ever, whose eyes were tender and who, from eagerness, became almost pressing.

Overcoming her embarrassment, the queen, smiling and with downcast eyes, rose and announced her intention of retiring for the night.

— ‘What!’ cried Soliman. ‘Will you thus leave your humble slave without a word, without hope, without some token of your compassion? A union I have dreamed of, a happiness without which I can no longer live, an ardent and submissive love which begs its reward, will you trample all underfoot?’

He had seized the hand she had previously abandoned to him, regaining it effortlessly; but she resisted. True, Balkis had thought more than once of this alliance; but she was determined to preserve her freedom and power. She therefore insisted on retiring, and Soliman found himself obliged to yield.

— ‘Very well,’ he said, ‘leave me; but I set two conditions for your doing so.’

— ‘Speak.’

— ‘The night is sweet and your conversation sweeter. Will you grant me one more hour?’

— ‘Agreed.’

— ‘Secondly, you may not take anything that belongs to me ere you leave.’

— ‘Agreed, with all my heart!’ replied Balkis, laughing aloud.

— ‘Laugh, my queen! I have seen even the wealthiest folk yield to the most bizarre temptations...’.

— ‘Wonderful! You are clever in your means of saving your self-esteem. No deceit now; a peace treaty.’

— ‘An armistice, since I still hope....’

The conversation was resumed, and Soliman sought, being a knowledgeable man, to make the queen converse for as long as he could. A jet of water, which babbled away at the rear of the room, served for an accompaniment.

Now, if talking parches the mouth, it is doubly so when one has eaten without drinking, and done honour to too well-seasoned a supper. The lovely Queen of Sheba was dying of thirst; she would have given one of her provinces for a jug of fresh water.

Yet she did not dare betray that ardent wish. And the fountain clear, fresh, silvery and mocking still tinkled beside her, throwing out pearls which fell back into the basin with a pleasant sound. And her thirst increased: the queen, panting, could no longer resist.

While continuing the conversation, on seeing Soliman distracted and as if weighed down, she began to walk in various directions about the room, and twice passed very close to the fountain, but did not dare....

The desire became irresistible. She returned, slowed her pace, steadied herself with a glance, then furtively plunged the hollow of her lovely hand into the water; turning away, she quickly swallowed the mouthful of pure water.

Soliman rose, approached, took hold of her hand, wet and gleaming, and, in a tone as cheerful as it was resolute, said:

— ‘A queen is true to her word, and by the terms you agreed, you belong to me.’

— ‘What does this mean?’

— ‘You have stolen water from me... and, as you yourself have rightly observed, water is most rare in my kingdom.’

— ‘Ah! Lord, this is but a trap; I do not desire so cunning a husband!’

— ‘All he needs do is prove to you he is yet more generous. If he grants you your freedom, despite our formal agreement...’

— ‘Lord,’ interrupted Balkis,’ bowing her head, we owe our subjects an example of loyalty.’

— ‘My Lady,’ Soliman, the most courteous prince of times past and future, replied, falling to his knees, ‘this command I give shall be your ransom.’

Rising swiftly, he struck a bell: twenty servants arrived, bearing various refreshments, and accompanied by the courtiers. Soliman articulated these words with majesty:

— ‘Offer your queen, a drink of water.’

At these words the courtiers fell, prostrate, before the Queen of Sheba and honoured her.

But she, palpitating and confused, feared that she had gone further than she would have liked....

— During the pause that followed this part of the story, a rather singular incident occupied the attention of the assembly. A young man, who by the colour of his skin, the colour, that is, of a new bronze coin, could be recognized as an Abyssinian (Habesch), rushed into the middle of the circle and began to dance a sort of bamboula, accompanying himself with a song in broken Arabic of which I have retained only the refrain. This song began with the soaring cry: ‘Yaman! Yamani!’ accented with those repetitions of long syllables peculiar to the Arabs of the South. ‘Yaman! Yaman! Yamani!... Sélam-Aleik Balkis-Mahéda!... Yaman! Yamani!’ which meant: ‘Yemen! Yemen! O Yemen!... Hail to you, Balkis the Great...Yemen! O Yemen!’

This bout of nostalgia can only be explained by the relationship that once existed between the peoples of Sheba and the Abyssinians, located on the western shore of the Red Sea, and who were also part of the empire of the Himyarites. Doubtless the admiration expressed by this listener, hitherto silent, was due to the preceding story being one of his country’s traditional tales. Perhaps he was happy, also, on hearing that the great queen had been able to escape the trap set by the wise King Solomon.

As his monotonous chant lasted long enough to annoy the regular customers, some of them cried out that he was melbous (a fanatic), and he was gently led towards the door. The café owner, anxious about the five or six paras (three centimes) that this customer owed him, hastened to follow him outside. All ended well, no doubt, for the storyteller soon resumed his narration in the midst of the most religious of silences.

Chapter 5: The Sea of Bronze

— By dint of vigilant labour, master Adoniram had completed, and set in the sand, the moulds for his colossal figures. Deeply dug, and artfully pierced, the plateau of Zion had received the imprint of the sea of bronze destined to be cast on site, solidly supported at first by masonry buttresses, which, later, were to be substituted by the lions, the gigantic sphinxes, intended to bear it permanently. It was upon bars of solid gold, resistant to fusing with the bronze flowing here and there, that the cover for this enormous basin was carried. Liquid iron, invading through several channels the space between the two parts, was to surround these gold pins, and become one with those refractory and precious bars.

Seven times had the Sun risen and set since the ore had begun to seethe in the furnace which was capped by a tall and massive brick tower ending, sixty cubits from the ground, in an open cone, from which escaped swirls of red smoke and blue flame flecked with sparks.

An excavation, made between the moulds and the base of the blast furnace, was to serve as a bed for the molten river of fire when the time came to open the entrails of the furnace with iron hooks.

To proceed with the great work of casting the metal, night was chosen: this was the time when they could follow the progress of the operation, a time when bronze, luminous and white, lights its own flow; and, if the glowing metal prepares some means of escape, if it flees through a crack, or pierces a hole somewhere, then that is unmasked in the darkness.

In anticipation of this solemn trial which would immortalise or discredit the name of Adoniram, everyone in Jerusalem was in turmoil. From all parts of the kingdom, workers had rushed to the site, abandoning their occupations, and, on the eve of the fatal night, as soon as the sun had set, the surrounding hills and mountains were cloaked with curious onlookers.

Never had an artist, on his own initiative, despite all objections, engaged in so formidable a task. On every occasion, the operation of casting metal offers a lively interest, and often, when important pieces were being created, King Soliman had deigned to spend the night at the forge with his courtiers, who disputed the honour of accompanying him.

But the casting of the brazen sea was a gigantic work, a challenge offered by genius to human prejudice, to Nature, and to the opinion of the experts, all of whom declared success impossible.

Also, people of all ages and countries, attracted by the spectacle of this venture, had already invaded the hill of Zion, the approaches to which were guarded by legions of workers. Noiseless patrols traversed the crowd to maintain order, and prevent excessive sound.... An easy task, since, by order of the king, announced by a trumpet blast, absolute silence had been imposed, the penalty for transgression being death; an indispensable precaution so that the artist’s commands could be transmitted with certainty and speed.

Already the evening star was setting over the sea; deep night, thickened with clouds lit by the flames of the furnace, announced that the moment was near. Followed by the chief workmen, Adoniram, running here and there in the torchlight, cast a last glance at the preparations. Under the vast roof that fronted the furnace, one might have seen the blacksmiths, wearing leather helmets with broad flaps, and dressed in long white short-sleeved robes, tearing, with the help of long iron hooks, masses of half-vitrified foam from the gaping mouth of the furnace, slag which they dragged away; others, perched on scaffolding borne on massive frames, threw baskets of coal, from the top of the structure, into the furnace itself, which roared with the impetus of the air from the bellows. On all sides, groups armed with picks, stakes, and pliers, wandered about, casting long trails of shadow behind them. They were almost naked: lengths of striped cloth covered their flanks; their heads were wrapped in woollen headdresses and their legs were protected by wooden greaves secured by leather straps. Blackened by the charcoal dust, they appeared red in the reflections of the embers; they moved about, here and there, like demons or ghosts.

A fanfare announced the court’s arrival: Soliman appeared, with the Queen of Sheba, and was received by Adoniram, who conducted them to thrones improvised for his noble guests. The artist had donned a breastplate of ox-hide; a white woollen apron descended to his knees; his sinewy legs were secured by tiger-skin gaiters, and his feet were bare, for he trod with impunity even upon red-hot metal.

— ‘You appear to me, in all your power,’ said Balkis to the king of the workmen, ‘like a god of fire. If your enterprise succeeds, no one will be able to say, this night, that he is greater than Master Adoniram!’

The artist, amidst his cares, was about to answer, when Soliman, always cautious and sometimes jealous, stopped him.

— ‘Master,’ he said in an imperative tone, ‘do not lose precious time; return to your labours, and do not let our presence here give rise to some accident.’

The queen waved him on, and he disappeared.

— ‘If he accomplishes his task,’ thought Soliman, ‘with what a magnificent monument he will honour the Temple of Adonai! Yet what brilliance he will add to his already formidable power!’

A few moments later, they saw Adoniram again, before the furnace. The brazier, which lit him from below, seemed to elevate his stature, his shadow ascending the wall, from which hung a large sheet of bronze on which the master struck twenty blows with an iron hammer. The sound of the vibrating metal echoed in the distance, then the silence grew deeper than before. Suddenly, ten shadowy phantoms, armed with levers and picks, swarmed into the excavation made beneath the outlet from the furnace, opposite the throne. The bellows rattled, and breathed, and only the dull sound of those iron implements penetrating the calcined clay, which sealed the orifice through which the liquid metal would rush, was heard. Soon the aperture turned darker, became purple, reddened, glowed, and acquired an orange colour; a white point appeared in the centre, and all the workers, but two, withdrew. The latter, under the supervision of Adoniram, worked to thin the crust around the luminous point, avoiding piercing it.... The master watched on anxiously.

During these preparations, Adoniram’s faithful companion, young Benoni, who was devoted to him, passed among the groups of workmen, encouraging their zeal, observing whether the master’s orders were being followed, and assessing their efforts himself.

It was this youth, who ran to the feet of Soliman, prostrated himself, fearfully, and said:

— ‘Lord, suspend the flow, all is lost, we are betrayed!’

It was not customary to approach the prince in this way without permission; the guards were already approaching the rash fellow; Soliman dismissed these attentions, and, leaning over Benoni who was kneeling, said to him in a low voice:

— ‘Explain yourself, swiftly.’

— ‘I was circling the furnace: behind the wall, there was a man, standing motionless, who seemed to be awaiting some event; a second man appeared, who said in a low voice to the first: Vehmamiah! He answered: Eliael! A third came who also pronounced the word: Vehmamiah! to whom the two answered in the same manner: Eliael! then one said:

— ‘He makes the carpenters slaves to the miners.’

— The second: ‘He subordinates the masons to the miners, too.’

— The third: ‘He seeks to rule over the miners.’

— The first replied: ‘His powers serve strangers.’

— The second: ‘He has no homeland.’

The third added: ‘This is truth.’

— ‘The companions are brothers’ ... recommenced the first.

— ‘The trades have equal rights,’ continued the second.

The third added: ‘This is truth.’

I realised the first was a mason, since he later said: ‘I have mixed limestone with brick, and the lime will crumble into dust. The second was a carpenter; he said: ‘I have raised the crosspieces for the beams, and the flame will visit them.’ As for the third, he worked the metal. These were his words: ‘I have drawn masses of bitumen and sulphur from the poisoned lake of Gomorrah; I have mixed them into the metal.’

At that moment a shower of sparks illuminated their faces. The mason is a Syrian, his name Phanor; the carpenter a Phoenician, his name Amrou; the miner an Israelite from the tribe of Ruben, his name Methousael. Great king, I have hastened to your feet: extend your sceptre and halt the work!’

— ‘It is too late,’ said Soliman thoughtfully; ‘the furnace is about to be drained; keep silence, do not disturb Adoniram, but repeat those three names to me.’

— ‘Phanor, Amrou, and Methousael.’

— ‘Let all be as God wills.’

Benoni stared at the king, then fled with lightning speed. Meanwhile, the hard-baked clay was falling from the stoppered mouth of the furnace, beneath the redoubled blows of the miners, and the thinning layer grew so luminous, it seemed as if the sun were about to be roused from its deep nocturnal retreat. At a sign from Adoniram, the labourers moved aside, and while hammers made the bronze sheet resound, lifting an iron club, he drove it into the diaphanous wall, turned it in the wound, and violently tore it forth. In an instant, a rapid torrent of white molten metal rushed into the channel, and advanced, like a fiery serpent streaked with crystal and silver, towards the basin dug in the sand, until the metal’s flow split into several further channels.

Suddenly a crimson and purple light illuminated the faces of the innumerable spectators on the hillsides; its gleams penetrated the darkness of the clouds, and reddened the crests of the distant rocks. Jerusalem, emerging from the darkness, seemed prey to fire. A profound silence gave this solemn spectacle the fantastic aspect of a dream.

As the outflow began, a shadow was seen hovering around the basin the bronze was about to invade. A man had rushed forward, and, in spite of Adoniram’s prohibitions, had dared to cross the channel intended for the metal. As he set foot there, the molten stream reached him, knocking him down, and he disappeared in a moment.

Adoniram’s thought was only for his work; overwhelmed by the thought of imminent disaster, he raced forward likewise, armed with an iron hook, and at the risk of his life plunged it into the victim’s breast, hooked him, raised him, and, with a superhuman effort, threw him like a block of slag onto the bank, where the luminous mass might darken and expire.... all so swiftly, that he failed to recognise the victim as his companion, the faithful Benoni.

While the molten metal flowed, like a river, to fill the cavities of the sea of bronze, whose vast outline had already been traced like a golden diadem in the darkened sand, gangs of workmen carrying large fire-pots, deep receptacles attached to long iron rods, plunged them one by one into the basin of liquid fire, and ran here and there pouring the metal into the moulds prepared for the lions, oxen, palms, and cherubim, the giant figures intended to support the sea of bronze. The onlookers were astonished at the quantity of metal the earth seemed to drink; outlines, like those of bas-reliefs lying flat on the ground, traced the clear and vermilion shapes of horses, winged bulls, cynocephali, and monstrous chimeras engendered by the genius of Adoniram.

— ‘A sublime spectacle!’ cried the Queen of Sheba. ‘O the grandeur! O the power of this mortal genius, who subdues the elements and tames Nature herself!’

— ‘He is not yet victorious,’ replied Soliman bitterly, ‘Adonai alone is all-powerful!’

Chapter 6: The Apparition

Suddenly Adoniram noticed that the river of metal was overflowing; the gaping spring vomited torrents; the overcharged sand collapsed: he fixed his eyes on the sea of bronze; the mould overflowed; a crack opened at the top; lava flowed out on all sides. He exhaled a cry so terrible that the air was filled with it and the echoes repeated from the mountain-slopes. Thinking that the sand, now over-heated, was vitrifying, Adoniram seized a flexible hose leading to a reservoir of water, and, with a hasty hand, directed a column of water onto the base of the crumbling buttresses of the basin’s mould. But the metal, having taken flight, hurtled onwards: the two liquids fought each other; a mass of metal enveloped the water, imprisoned it, embraced it. Freeing itself, the trapped water vaporised and burst its shackles. A detonation resounded; the metal spurted into the air in dazzling jets twenty cubits high; as if the crater of an angry volcano had opened. This detonation was followed by cries, by dreadful howls; for the rain of fire sowed death everywhere: every drop of metal was a burning dart which penetrated the body and killed. The place was strewn with dying people, the silence succeeded by an immense wail of terror. The terror at its height, all fled; fear of danger drove into the fire those whom the fire pursued.... the countryside about, illuminated, turning a dazzling purple, recalled that dreadful night when Sodom and Gomorrah blazed, scorched by Jehovah’s lightning-bolts.

Adoniram, distraught, ran here and there to rally his workers, and close the mouth of the seemingly inexhaustible stream; but he heard only cries and curses; he stumbled over corpses: the rest of his men were scattered. Soliman alone remained impassive on his throne; the queen calm at his side. The diadem and the sceptre still shone in the darkness.

— ‘Jehovah has punished him!’ said Soliman to his hostess, ‘and he punishes me, through the death of my subjects, for my weakness, my self-indulgence, and my monstrous pride.’

— ‘The vanity that causes so great a sacrifice, so many victims, is criminal,’ pronounced the queen. ‘Lord, you might have perished during this infernal ordeal: bronze rained down around us.’

— ‘And you were here! This vile servant of Baal has endangered a precious life! Let us leave, queen; your peril alone concerns me.’

Adoniram, who was passing by, heard this; he went away roaring with pain. Further on, a group of workmen overwhelmed him with their contempt, slander and curses. He was joined by the Syrian, Phanor, who said to him:

— ‘You are mighty; chance has betrayed you; but the masons were not its accomplices.’

Amrou the Phoenician joined him, and said to him, in turn:

— ‘You are mighty, and would have been victorious, if all had done their duty as the carpenters have.’

And the Israelite, Methousael said to him:

— ‘The miners have done theirs; but it is these foreign workers who, through their ignorance, have compromised the enterprise. Courage! A greater work will avenge us for this failure.’

— ‘Ah,’ thought Adoniram, ‘these are the only friends I have found....’

It was easy for him to avoid further encounter; all turned away from him, and the darkness hid their desertion. Soon only the glow of the braziers, and the metal turning red as it cooled on the surface illuminated the distant groups of workers, gradually lost in the shadows. Adoniram, dejected, sought Benoni.

— ‘He too has abandoned me,’ he murmured sadly.

The master remained alone beside the furnace.

— ‘Dishonoured!’ he murmured, bitterly. ‘Such is the fruit of an austere, laborious existence devoted to the glory of an ungrateful prince! He condemns me, and my brothers deny me! And this queen, this woman ... she was there, she saw my shame, and I… was forced to endure her contempt! But where is Benoni, at the moment when I suffer? Alone! I am alone, and cursed! The future is closed to me. Adoniram, smile at your deliverance, and seek it in fire, your element, and your rebellious slave!’

He advanced, calmly and resolutely, towards the river of molten metal, coursing along in fiery waves beneath the slag, and which, here and there, spurted and sparkled on contact with the humid air. The lava covered corpses, perhaps still quivering. Thick whirlwinds of violet and tawny smoke emerged in narrow columns, and veiled the abandoned theatre of his lugubrious venture. It was there that the thunderstricken giant collapsed, to sit upon the ground and lose himself in meditation ... his eye fixed on those fiery whirlwinds which might lean towards and smother him at the first breath of wind.

Certain strange, fleeting, extravagant forms appeared, now and then, among the bright, lugubrious play of the fiery vapour. Adoniram’s dazzled eyes glimpsed, amidst the limbs of giants, and blocks of gold, gnomish figures that scattered in smoke, or dissipated themselves in sparks. These fancies failed to distract him from his pain and despair. Soon, however, they seized possession of his delirious imagination, and it seemed to him that from the heart of the flames arose a grave, resounding voice that pronounced his name. Three times the whirlwind roared the name of Adoniram.

Around him, nothing moved.... He gazed greedily at the burning sand, and murmured:

— ‘The voice of the people calls to me!’

Without looking away, he rose on one knee, stretched out a hand, and distinguished a colossal, but indistinct human form in the midst of the red smoke, a form which seems to grow more solid in the flames, to gather itself, then dissolve, and merge. Everything around it stirred and blazed...it alone seemed fixed, though by turns obscure, or clear and dazzling, in the luminous vapour, amidst a mass of soot and smoke. It took shape, this figure, it acquired an outline, it grew larger again, and approached, and Adoniram, terrified, wondered what bronze creature this was, endowed with life.

The phantom advanced. Adoniram contemplated it in his stupor. Its gigantic chest was clad in a sleeveless dalmatic; its bared arms were adorned with iron rings; the bronzed head was framed by a square beard, braided and curled in several rows...and that head was crowned with a vermilion mitre; the figure held a hammer in its hand. Its large eyes, which shone with a gentle glow, bent themselves upon Adoniram, and, in a voice that seemed torn from entrails of bronze it murmured:

— ‘Rouse your spirit! Arise, my son!... Come, follow me.... I have seen the evils perpetrated by my descendants, and have taken pity on the latter....’

— ‘Spirit, who are you?’

— ‘The shade of the father of your fathers, the ancestor of those who work and suffer. Come! When my hand has smoothed your forehead, you will be able to breathe amidst the flames. Be without fear, as you once were without weakness....’

Suddenly, Adoniram felt himself enveloped by penetrating heat which animated him without setting him ablaze; the air he inhaled seemed subtler; an invincible and mounting force bore him towards the blaze into which his mysterious companion had already plunged.

— ‘Where am I? What is your name? Where are you leading me?’ he whispered.

— ‘To the centre of the earth ... the soul of the inhabited world; there rises the subterranean palace of Enoch, our father, whom Egypt calls Hermes, whom Arabia honours under the name of Idris.’

— ‘Immortal powers!’ cried Adoniram. ‘O my lord! Is it then true, you must be…?’

— ‘Your ancestor, a human being ...and an artist; your master and your patron: I was Tubal-Cain.’

The further they advanced, into the deepest regions of silence and night, the more Adoniram doubted the reality of his sensations. Little by little, distracted from himself, he was beguiled by the charm of the unknown, and his spirit, attached entirely to the mounting power which dominated him, was entirely devoted to his mysterious guide.

The humid, cold regions were succeeded by a warm, rarefied atmosphere; the inner life of the earth manifested itself by quakes, by singular humming sounds; dull, regular, periodic throbs announced the proximity of the heart of the world; Adoniram felt it beat with increasing force, and he was astonished at moving among endless spaces; he sought support, found it not, and followed, without being aware, the shade of Tubal-Cain, who remained silent.

After a few moments which seemed to him as long as the life of a patriarch, he discovered in the distance a luminous point. This spot grew, approached, extended in lengthy perspective, and the artist glimpsed a world peopled with labouring shades, given over to occupations which he did not understand. The tremulous light finally expired above the dazzling mitre, and on the dalmatic, of the son of Cain.

In vain did Adoniram strive to speak: his voice died in his oppressed chest; but he breathed again on finding himself in a vast gallery of immeasurable depth, so large that the walls were invisible, and the vault above, which they supported, borne on an avenue of columns so high that they were lost above him in the air, escaped sight.

Suddenly he started; Tubal-Cain began to speak:

— ‘Your feet rest upon the great emerald stone that serves as root and pivot of the mountain of Kaf; you have approached the domain of your ancestors. Here the line of Cain reigns unchallenged. Within these granite chambers, amidst these inaccessible caverns, we have finally found our freedom. It is here the jealous tyranny of Adonai expires, here one can, without perishing, feed on the fruit of the tree of knowledge.’

Adoniram exhaled a long, sweet sigh: it seemed to him that an overwhelming weight, which had always bowed him down in life, had vanished at last.

Suddenly life burst forth; forms appeared among these hypogea: work animated them, agitated them; the joyful din of beaten metal echoed; the sounds of gushing water and impetuous winds were mingled there; the open vault extended like an immense sky from which torrents of white, and azure light, which become iridescent as they fall to the ground, poured down over the largest and strangest of workshops,

Adoniram passed amidst a crowd given over to efforts whose goal he could not grasp; this clarity, this celestial dome in the bowels of the earth astonished him; he halted.

— ‘This is the sanctuary of fire,’ Tubal-Cain told him; ‘from here arises the heat of the earth, which, without our labours, would perish from cold. We prepare the metals, we distribute them by means of the planet’s veins, after liquefying these vapours.

Gathered and intertwined about our heads, the veins of various ores release opposing spirits which ignite and project these brilliant lights ... dazzling to your imperfect eyes. Attracted by these flows, the seven metals vaporise around them, and form clouds of sinople, azure, purple, gold, crimson and silver which move in space, and reproduce the alloys of which most minerals and precious stones are composed (The seven metals of alchemy were lead, tin, iron, gold, copper, mercury, and silver, each twinned with a planetary symbol). As the dome above cools, these condensing clouds rain down a hail of rubies, emeralds, topazes, onyxes, turquoises, and diamonds, and the currents of the earth bear them away amidst masses of scoria: granites, flints, and limestones which, raising the surface of the globe, fold themselves to form mountain ranges. These materials solidify as they approach the domain of men... and that of the faded sun of Adonai, a failing furnace that lacks even the strength to heat an egg. What would become of the life of man, if we did not secretly pass to him the element of fire, imprisoned in rock, as well as the flintstone fit to create a spark?’

His explanation satisfied Adoniram, while astonishing him. He approached the workers without understanding how they could work the rivers of gold, silver, bronze, and iron, separate them, dam them, and sift them, as the waves sift the contents of the sea.

— ‘These elements,’ said Tubal-Cain, answering his thought, ‘are liquefied by the central fire: the temperature where we are now is twice as great as that of the furnaces in which you dissolve metal.’

Adoniram, terrified, felt surprised to be still alive.

— ‘This degree of heat,’ resumed Tubal-Cain, ‘is the natural temperature of souls extracted from the element of fire. Adonai placed an imperceptible spark in the centre of that mould of clay from which he thought to form humankind, and the spark was enough to heat the mass, animate it and grant it thought; but there, above, such souls struggle against the cold: hence the narrow limits of your faculties; then it happens that the spark is drawn below by the attraction of the Earth, and you die.’

Creation, thus explained, prompted a sign of disdain from Adoniram.

— ‘Yes, continued his guide ‘he is a god less strong than subtle, and more jealous than generous, that Lord Adonai. He created Man of clay, in spite of the genies of fire; then, fearful of his work, and the genies’ pity for that sad creature, He, without pity for human tears, condemned Mankind to die. That is the source of the dispute which divides us: all terrestrial life proceeding from fire is attracted by the fire which resides at the centre. We wished in return that the central fire should be attracted by the circumference, and radiate outwards: this exchange of principles would have guaranteed life without end.

Adonai, who rules the worlds, closed up the Earth, and nullified that external power of attraction. As a result, the Earth will die like its inhabitants. It is already aging; the cold penetrates more and more; entire species of animals and plants have vanished; the nations are diminishing, the duration of life grows shorter, and, of the seven primitive metals, the earth, whose marrow freezes and dries up, already receives only five (the golden and silver ages having passed). The sun itself is failing; it will die in five or six thousand years. But it is not for me alone, O my son, to reveal these mysteries to you: you shall hear them from the mouths of your ancestors.’ (Author’s note: the traditions on which the various scenes of this tale are based are not peculiar to the Orient. The European Middle Ages knew them. One may consult the ‘Praeadamitae’ of Isaac de la Peyrère, Louis de Holberg’s ‘Nicolai Klimii Iter Subterraneum’, and a host of writings relating to the Kabbalah, and Spagyric medicine. The Orient is alive in them. One should not therefore be surprised by the strange scientific hypotheses this tale contains. Most of these legends are also found in the Talmud, the books of the Neoplatonists, the Koran, and in ‘The Book of Enoch’, recently translated by Richard Laurence, Archbishop of Cashel.)

Chapter 7: The Subterranean World

— Together, they entered a garden lit by the tender glow of a gentle fire, populated with unknown trees whose foliage, formed of small tongues of flame, cast, instead of shadow, brighter light on the emerald ground, dappled with flowers of strange shape, in surprisingly vivacious colours. Blossoming from that fire within the region of metals, the flowers were its most fluid and purest emanations. The arborescent vegetation of flowering metal shone with a brilliance like that of precious stones, while exhaling perfumes of amber, benzoin, incense and myrrh. Nearby, streams of naphtha meandered, feeding the veins of cinnabar, the rose of those subterranean regions. There, were statues also, of giant old men, sculpted to the measure of that impressive and exuberant place. Beneath a canopy of blazing light, Adoniram saw a row of seated Colossi, reproducing the sacred costumes, sublime proportion and imposing aspect of those figures he had once viewed in the caves of Lebanon. He divined them to be of that vanished dynasty, the princes of Enochia. Around them, crouching, he saw once more, were the cynocephali, the winged lions, the griffins, the smiling and mysterious sphinxes, those condemned species, swept away by the Flood, but immortalised in the memory of men. Those androgynous slaves, inert, docile, yet animate, supported the massive thrones.

Motionless, and at rest, the princes, descendants of Adam, seemed to dream and wait.

Having reached the end of the row, Adoniram, walking further, directed his steps towards an enormous square stone, white as snow, and was about to set foot upon that mass of incombustible asbestos-bearing rock.

— ‘Halt!’ cried Tubal-Cain. ‘We are beneath the mountain of Serendib; you are about to view the unvisited tomb of the first-born of the earth. Adam sleeps beneath this stone, which preserves him from the fire. He may not rise again until the last day of the world; his tomb holds our ransom fast. But listen: our common father calls out to you.’

Cain, it was, who was crouched in a painful posture; he raised himself. His beauty was superhuman, his eyes sad, his lips pale. He was naked, and around his furrowed brow coiled a golden serpent, like a diadem.... That errant ancestor seemed harassed still.

— ‘May sleep and death be yours, my son! Oppressed and labouring race, it is through my deed that you suffer. Eve was my mother; Iblis, the angel of light, set at her heart the spark that animates me, and that generated our line. Adam, kneaded of clay and the depository of a captive soul, Adam nourished me. Child of the Elohim, I loved those offspring of Adonai, and placed at the service of ignorant and feeble Mankind the spirit of the genius that resides in me. I nourished my foster-father in his old age, and cradled Abel in his infancy... he whom they called my brother. Alas! Alas! (Author’s note: The Elohim were primitive genii whom the Egyptians called the gods of Ammon. In the Persian tradition, Adonai or Jehovah, the god of the Israelites, was simply one of the Elohim.)

Before teaching the earth how to commit murder, I had felt that ingratitude, sense of injustice, and bitterness that corrupts the heart. Working ceaselessly, raising crops from the greedy soil, inventing, for the happiness of men, those ploughs that force the earth to produce, recreating for them, in the midst of abundance, the Eden they have lost; I made of my life a sacrifice. O depths of iniquity! Adam showed me no love! Eve believed herself banished from paradise for having brought me into the world, and her heart, closed to me, was concerned only for her Abel. He, disdainful and pampered, considered me the servant of both: Adonai favoured him, what more was needed? So, while I moistened the ground with my sweat over which Abel felt himself to be king, he himself, idle and adored, grazed his flocks and slumbered beneath the sycamores. I complained: our parents invoked God’s justice; we offered Him our sacrifices, and mine, sheaves of wheat that I had made to flourish, the first fruits of summer, mine was rejected with contempt.... it is thus that the jealous God has always rejected fertile and inventive genius, and granted the power of oppression to vulgar minds. You know the rest, all except that my rejection by Adonai, while condemning me to sterility, granted young Abel our sister Aclinia, as his wife, by whom I was loved. From that arose the first battle of the Djinns, the children of the Elohim, born of the element of fire, against the sons of Adonai, born of earth.

I extinguished Abel’s light.... Adam saw himself reborn later in the posterity of Seth; and, to atone for my crime, I became a benefactor to the children of Adam. It is to our race, superior to theirs, that they owe their arts, their industry, and the elements of their science, all their vain efforts! By instructing them, I freed them.... Adonai has never forgiven me, and that is why he marked me down as an irredeemable criminal, having broken that vessel of clay; He who, in the waters of the Flood, drowned so many thousands of human beings! He who, to decimate their numbers, raises up so many tyrants from among them!’

Then a voice arose from Adam’s tomb.

— ‘It was you,’ said the voice, in a deep tone, ‘you who gave rise to murder. God retains, in my descendants, the blood of Eve from which you came, and which you shed! It is because of you that Jehovah raised up priests who have immolated men, and kings who sacrificed both priests and soldiers. One day, he will raise up emperors to crush the people, priests and kings themselves, and the posterity of the nations will say: ‘These are the sons of Cain!’

Eve’s son stirred in despair.

— ‘He too!’ he cried, ‘He too, has never forgiven me.’

— ‘Never!’... the voice echoed.

And, from the depths of the abyss, he was heard to moan once more:

— ‘Abel, my son, Abel, Abel!... what have you done to your brother Abel?...

Cain rolled on the ground, which quaked, and in a convulsion born of despair tore at his chest....

Such is the punishment of Cain, because he shed blood.

Filled with respect, love, compassion and horror, Adoniram turned away.

— ‘What have I done, I?’ said the venerable Enoch, shaking his head surmounted by a tall crown. ‘Men wandered in herds; I taught them to cut stone, to build dwellings, to gather together in cities. I was the first to reveal to them the forms of society. I had gathered together mere brutes; ... I left them a nation in my city of Enochia, whose ruins still astonish the degenerate peoples. It is thanks to me that Soliman chooses to erect a temple in honour of Adonai, and this Temple will be his downfall; for the God of the Israelites, my son, has recognised my genius in the work of your hands.’

Adoniram contemplated that mighty shade: Enoch possessed a long, braided beard; his crown, adorned with crimson bands and a double row of stars, was surmounted by a point ending in a vulture’s beak. Two fringed bands fell over his hair and tunic. In one hand he held a long sceptre, and in the other a set-square. His colossal stature exceeded that of his father Cain. Near him stood Irad and Maviael, wearing plain bands about their hair. Bracelets wound about their arms: one had captured the water of the founts; the other had felled and trimmed the cedars. Mathusael had conceived of written characters, and left behind books which Idris later seized, and buried in the earth; the books of Tau. Mathusael bore on his shoulder a hieratic pallium and a parazonium, a short sword, at his side, and on his dazzling belt shone the fiery symbolic letter T which unites all workmen descended from the spirits of fire.

While Adoniram contemplated the smiling features of Lamech, whose arms were covered by his folded wings from which emerged two long hands resting on the heads of two crouching young men, Tubal-Cain, leaving his protégé, had taken his place on his iron throne.

— ‘You behold the venerable face of my father,’ he said to Adoniram. ‘These, whose hair he caresses, are the two children of Adah: Jabel, who first pitched tents, and learned to sew camel-skins, and Jubal, my brother, who was the first to string the kinnor, and the harp, and learn how to draw forth notes.’

— ‘Son of Lamech and Sella,’ replied Jubal in a voice as harmonious as the evening winds, ‘you are greater than your brothers, and reign over your ancestors. It is from you that the arts of war and peace proceed. You revealed the reduction of metals, you lit the first forge. By granting humans the use of gold, silver, copper and steel, you have recreated for them the tree of knowledge. Gold and iron will raise them to the heights of power, and will prove deadly enough for them to deal vengeance, on our behalf, upon Adonai. Honour to Tubal-Cain!’

A tremendous noise, from all sides, responded to this exhortation, repeated in the distance by the legions of gnomes, who resumed their labours with a new ardour. The sound of hammers echoed from the vaults of the eternal factories, and Adoniram ... the workman, in this world where the workmen were kings, felt a deep joy and pride.

— ‘Child of the race of the Elohim,’ Tubal-Cain said to him, ‘take courage, your glory is in servitude. Your ancestors made human industry formidable, and that is why our line was condemned. We fought for two thousand years; they could not destroy us, because we are of immortal essence; they succeeded in conquering us, because the blood of Eve mingled with our blood. Your ancestors, my descendants, were preserved from the waters of the Flood. For, while Jehovah, preparing our destruction, filled the reservoirs of heaven with them, I called fire to my aid and sent swift streams of flame towards the surface of the globe. At my command, the flame dissolved stone and excavated long galleries fit to serve as our retreats. These subterranean roads ended beneath the plain of Giza, not far from these shores where the city of Memphis has since arisen. In order to preserve the galleries from the water’s invasion, I gathered the race of giants, and our hands raised an immense pyramid which will last as long as the world. The stones were cemented with impenetrable bitumen; and no other opening was made than a narrow corridor closed by a small door which I walled up myself on the last day of the ancient world.

Underground dwellings were dug into the rock: one entered by descending into the depths; they lined a low gallery leading to the mass of water I had trapped in a great river, suitable for quenching the thirst of the human beings and herds concealed in these retreats. Beyond the river, I had gathered, in a vast space lit by fires generated by the friction produced by opposing metals, the vegetables and fruits nourished by the earth.

It was there that the feeble remains of the line of Cain lived, sheltered from the waters. All the trials we had undergone and journeys we had made, it was necessary to repeat in order to reach the light once more, once the waters had regained their bed. The ways were perilous, the climate within enervated us. During the outward and return journeys, through each region, we left behind a few companions. I alone, survived in the end, along with the son my sister Noema had borne me.

I unsealed the pyramid, and viewed the land. How vast the change! Mere desert!... Frail creatures, stunted plants, a pale and heatless sun, and here and there heaps of infertile mud through which reptiles crawled! Suddenly an icy wind, laden with infectious miasma, penetrated my chest, and scorched it. Half-suffocated, I expelled it, then breathed it in again so as not to die. I know not what chill poison circulated in my veins; my vigour was eclipsed, my legs gave way, black night surrounded me, a shivering seized me. The Earth’s climate had altered: the ground, cooling, no longer gave off enough heat to animate that to which it had formerly given life. Like a dolphin hurled from the depths of the seas onto the sand, I felt agony, and understood that my last hour had come....

Driven by the supreme instinct for self-preservation, I sought to flee, and, plunging into the pyramid, there I lost consciousness. It became my tomb; my spirit delivered thence, attracted by the internal fires, returned to seek those of my fathers. As for my son, barely adult, and still developing; he survived; but his growth ceased.

He wandered following the destiny of our race, until the wife of Ham, Noah’s second son, found him most beautiful among the sons of men. He knew her: she gave birth to Cush, the father of Nimrod, who taught his brothers the art of hunting, and founded Babylon. They undertook to build the tower of Babel; then, Adonai recognised, once more, the blood of Cain, and began to persecute them. The descendants of Nimrod were again scattered. Let the voice of my son bring this painful story to an end.’ (Author’s note: according to Talmudic tradition, it was the wife of Noah herself who mixed the race of genies with the race of men, by yielding to the seductions of a spirit issuing from the heavens. See ‘The Count of Gabalis’, by Abbé de Villars).

Adoniram looked about him anxiously, seeking the son of Tubal-Cain.

— ‘You will not see him,’ said the prince of the spirits of fire. ‘My son’s spirit is invisible, since he died after the Flood, and his corporeal form belongs to the earth. It is so with his descendants; and your own father, Adoniram, is wandering amidst the fiery air that you breathe.... yes, your father.’

— ‘Your father, yes, your father’... repeated a voice like an echo, but with a tender accent, that passed like a kiss over Adoniram’s forehead.

And, turning around, the artist wept.

— ‘Console yourself,’ said Tubal-Cain, ‘he is happier than I. He left you in the cradle, and, as your body does not yet belong to the earth, he enjoys the happiness of seeing your face. But pay attention to the words of my son.’

Then a voice spoke:

— ‘Alone among the mortal geniuses of our race, I have seen the world before and after the Flood, and have contemplated the face of Adonai. I hoped for the birth of a son, though the chill wind of the aged earth oppressed my heart. One night, God appeared to me: his face cannot be described. He said to me:

— “Hope!” …

Lacking experience, isolated in an unknown world, I replied timidly:

— “Lord, I am afraid.”

He recommenced:

— “That fear will be your salvation. You must die; your name will be unknown to your brothers and leave not an echo amidst the passing ages, and of you will be born a son you will never see. From him will come those lost among the crowd, like planets wandering the firmament. Of the stock of giants, I have diminished you in form; your descendants will be born weak; their lives will be short; isolation will be their lot. Their breasts will preserve the precious sparks of genius, and their greatness will be their torment. Superior to others, they will be their benefactors yet will find themselves the object of their disdain; their tombs alone will be honoured. Unrecognised during their stay on earth, the strength they possess, they will exercise for the glory of others, despite a feeling of bitterness. Sensitive to the misfortunes of humanity, they will long to prevent them, without being able to make themselves heard. Subjected to vile and mediocre power, they will fail to overcome contemptible tyrants. Superior in spirit, they will be the playthings of opulence and happy stupidity. They will further the fame of the nations, yet not be famed in their lifetime. Giants of intellect, burning torches of knowledge, organs of progress, lights of the arts, instruments of freedom, they alone will remain slaves, solitary and disdained. Tender-hearted, they will be the target of envy; energetic of spirit, they will be paralysed through their kindness.... They will recognise one another.”

— “God is cruel!” I cried. “At least their life will be short, and the spirit will consume the body.”

— “Not so; they will nourish hope, ever disappointed yet constantly revived, and the more they labour by the sweat of their brow, the more ungrateful others will be. They will give joy and receive but pain; the burden of toil with which I have charged the descendants of Adam will weigh heavily on their shoulders; poverty will hound them; their families will be for them companions in hunger. Complaisant or rebellious, they will be constantly decried, they will work for all, and waste, in vain, their genius, their industry, and the strength of their arms.”

Jehovah spoke; my heart was broken; I cursed the night in which I had fathered a child, and expired.’

And the voice died away, leaving behind a long series of sighs.

— ‘You see, you hear,’ cried Tubal-Cain, ‘and our example is before you. Benevolent geniuses, authors of the many intellectual conquests of which mankind is so proud, we are in their eyes accursed devils, spirits of evil. Son of Cain, suffer your destiny! Bear it with imperturbable brow, and may the God of Vengeance be terrified by your constancy. Be great before men, and strong beside us. I saw you close to succumbing, my son, and I wished to support your virtue. The spirits of fire will come to your aid; dare everything; you are reserved for the downfall of Soliman, that faithful servant of Adonai. From you will be born a line of kings who will restore, on earth, despite Jehovah, the neglected worship of fire, the sacred element. When you are no longer on earth, the tireless militia of artisans will rally to your name, and a phalanx of workers and thinkers will one day destroy the blind power of kings, those despotic ministers of Adonai. Go, my son, fulfil your destiny....’

At these words, Adoniram felt himself raised aloft; the garden of metals, its sparkling flowers, its trees of light, the immense, brilliant workshops of the gnomes, the dazzling streams of gold, silver, cadmium, mercury and naphtha, merged beneath his feet to form a single wide channel of light, a rapid river of fire. He found himself gliding through space with the speed of a meteor. Everything gradually dimmed: the domain of his ancestors appeared to him for an instant like a motionless planet in the middle of a dark sky, a chill wind struck his face, he felt a jolt, cast his eyes about him, and found himself lying on the sand, at the foot of the mould of the brazen sea, surrounded by half-cooled lava, which still cast a reddish glow amidst the nocturnal mists.

— ‘A dream!’ he said to himself, ‘Was it only a dream? Unhappy man! What is only too real is the loss of my hopes, the ruin of my project, and the dishonour that awaits me at dawn....’

But the vision was so clearly imprinted that he suspected the very doubts that had seized him. As he was musing, he raised his eyes and recognised before him the colossal shadow of Tubal-Cain.

— ‘Genius of fire’, he cried, ‘lead me back to the depths of your abyss. Let the Earth hide my shame.’

— ‘Is this how you follow my precepts?’ the shade replied, in a harsh tone. ‘No idle words; the night is advancing, soon the flaming eye of Adonai will light the earth; we must hasten. Feeble child! Would I abandon you in so perilous an hour? Be fearless; the moulds are full: the metal, suddenly widening the orifice of the furnace walled with stones that were not refractory enough, burst forth, and the overflow gushed over the rim. You thought there was a crack, lost your head, threw water upon it, and the jet of metal scattered.’

— ‘Yet how can I free the edges of the basin from those metal burrs that adhere to it?’

— ‘Bronze is porous, and conducts heat less well than steel. Take a piece, heat it at one end, cool it at the other, and strike it with a sledgehammer: the piece will break at the point between. Ores and crystals do the same.

— ‘Master, I am listening.’

— ‘By Iblis! You would be better off understanding me. Your basin is still red-hot: cool, suddenly, the overflow from its rim, and detach the burrs with hammer-blows.’

— ‘It would need some vigour....’

— ‘It needs but a hammer. That of Tubal-Cain opened the crater of Etna to set flowing the slag from our own factories.’

Adoniram heard the sound of a piece of falling iron; he stooped and picked up a hammer, heavy but perfectly weighted, to suit his hand. He longed to express his gratitude; but the shade had disappeared, and the rising sun had begun to obscure the light of the stars.

A moment later, the birds, who were singing their preludes to the dawn, took flight at the sound of Adoniram’s hammer, which, striking with repeated blows the rim of the basin, alone disturbed the profound silence that precedes the birth of day....

— This session had greatly impressed the audience, which increased in numbers the next day. There was talk of the mysteries of the mountain of Kaf, which always greatly interest Orientals. To me, the tale had seemed Classical, and akin to Aeneas’ descent to the underworld.

Chapter 8: The Pool of Siloam

— The storyteller continued:

It was the hour when Mount Tabor casts its morning shadow on the hilly road to Bethany: a few white and diaphanous clouds wandered the depths of the sky, softening the morning light; the dew still lay in bluish sheets on the meadows; the breeze, murmuring in the foliage, accompanied the song of the birds which lined the path to Mount Moriah; one might have seen from afar the linen tunics and gauzy dresses of a procession of women who, crossing a bridge thrown over the Kidron, reached the banks of a stream which fed the Pool of Siloam. Behind them walked eight Nubians carrying a rich palanquin, and two burdened camels which ambled along, their heads swaying.

The litter was empty; for, having left, along with her women, at dawn, the tents outside the walls of Jerusalem where she had chosen to remain with her retinue, the Queen of Sheba had dismounted, better to enjoy the charm of the fresh countryside.

Young and pretty, for the most part, Balkis’ maidservants had set out early for the fount, to wash their mistress’ linen. She, dressed as simply as her companions, preceded them, gaily, her nurse beside her, while, following her footsteps, the young people chattered to each other as they were wont.

— ‘Your reasoning impresses me not, my daughter,’ said the nurse; ‘this marriage seems to me a serious folly; and if the error is excusable, it is only on account of the profit it might yield.’

— ‘An edifying moral! If the wise Soliman heard you...’

— ‘Is it wise of him, he being no longer young, to covet the rose of the Sabaeans?’

— ‘Flattery! Good Sarahil, you are breathing too deeply of the morning air.’

— ‘Do not rouse my un-awakened severity; I would merely say....’

— ‘Well, say on!’

— ‘That Soliman loves you; and you deserve it.’

— ‘I am unsure,’ replied the young queen, laughing. ‘I have interrogated myself, seriously, as regards the matter, and yes, it is probable that the king is not indifferent to me.’

— ‘If it were not so, you would not have examined this delicate point so scrupulously. You seek to combine with him in political alliance, and scatter flowers thus on the arid path of propriety. Soliman has rendered your kingdom, like those of all his neighbours, tributary to his power, and you dream of freeing them by giving yourself to a master whom you intend to make your slave. But take care!’

— ‘What have I to fear? He adores me.’

— ‘He professes, as regards his noble person, too lively a passion for you for his better feelings to overcome the desire of the senses, and nothing is more fragile. Soliman is, in truth, thoughtful, ambitious and cold.’

— ‘Is he not the greatest prince on earth, the noblest scion of the race of Shem, from whom I am descended? Find in the world a prince more worthy than he to give successors to the dynasty of the Himyarites!’

— ‘The line of the Himyarites, our ancestors, descends from nobler roots than you think. Do not the children of Shem command the inhabitants of the air?... I hold, in the end, to the oracular predictions: your destiny is not yet fulfilled, and the sign by which you shall recognise your husband has not appeared; the hoopoe has not yet interpreted the will of the eternal powers which guard you.’

— ‘Must my fate depend on the dictates of a bird?’

— ‘Of a bird unique in all the world, whose intelligence is shared with no known species; whose spirit, the high priest told me, was born of the element of fire. It is no terrestrial creature; it belongs to the djinns (genies).’

— ‘It is true,’ replied Balkis, ‘that Soliman attempts to tame her, yet he offers her his shoulder or fist in vain.’

— ‘I fear she will never rest there. At the time when the creatures were submissive — for those species are extinct — they did not obey Mankind created from clay. They were only subject to the divs, or djinns, children of the air or fire.... Soliman is of the species formed from clay by Adonai.’

— ‘And yet the hoopoe obeys me...’

Sarahil smiled and nodded: a princess of the blood of the Himyarites, and a relative of their last king, the queen’s nurse had studied the natural sciences: her prudence matched her discretion and kindness.

— ‘My Queen,’ she added, ‘there are secrets kept from the young, which the girls of our house must remain ignorant of prior to their marriage. If passion leads them astray, and causes them to fall, these mysteries remain hidden from them, so that common men may be eternally excluded from knowledge of them. Let this suffice you: Hud-Hud, that renowned bird, will only recognise as master the husband reserved for the Princess of Sheba.’

— ‘You will make me curse this feathered tyrant.’

— ‘Who will save you, perhaps, from a despot armed with a sword.’

— ‘Soliman has my word, and, unless he, rightfully, incurs our resentment, Sarahil, the die is cast; the time granted me will expire, and, this very evening....’

— ‘The power of the Elohim (the gods) is great!’ murmured the nurse.

To end the conversation, Balkis turned away, and began to gather the flowers of hyacinths, mandragoras, and cyclamens which dappled the meadow’s green, while the hoopoe, which had fluttered after her, jumped around her coquettishly, as if seeking her forgiveness.

This pause allowed the women to rejoin, belatedly, their sovereign. They spoke among themselves of the Temple of Adonai, whose walls were rising, and of the brazen sea, which had been the subject of all conversation for four days.

The queen seized on this fresh source of conversation, and her attendants, in their curiosity to hear her comments, surrounded her. Tall sycamores, which spread verdant arabesques above their heads against the azure background, enveloped this charming group in delicate shadows.

— ‘Nothing equals the astonishment which seized me yesterday evening,’ Balkis told them. ‘Soliman himself was speechless with stupor. Three days before, all had seemed lost; Master Adoniram had collapsed, as if struck by lightning, amidst the ruins of his work. His victory, betrayed, vanished before our eyes amidst torrents of rebellious lava; the artist was plunged again into darkness.... Now, his name echoes triumphantly from the hills; his workmen have heaped palm-leaves at the threshold of his dwelling, and he is more powerful than ever in Israel.’

— ‘His roar of triumph,’ said a young Sabaean woman, ‘reached our tents, and, troubled by the memory of that recent catastrophe, O queen, we feared for your life! Your servants know not what occurred.’

— ‘Without waiting for the iron to cool, or so I am told, Adoniram, summoned his discouraged workmen the following morning. Their mutinous leaders surrounded him; he calmed them in a few words: for three days, they laboured, freeing the mould to accelerate the cooling of the basin that they believed damaged. A profound mystery hid their efforts. On the third day, those innumerable artisans, anticipating dawn, raised the bronze bulls and lions with levers still blackened by the heat. The massive blocks were dragged beneath the basin, and adjusted, with a promptness that bordered on the miraculous; the hollow sea of bronze, freed from its supports, settled on its twenty-four caryatids; and, though Jerusalem deplored the idle expense, the admirable work shone before the astonished eyes of those who had accomplished it. Suddenly, the barriers erected by the workmen fell: the crowd rushed forward; their noise spread to the palace. Soliman feared sedition; he hastened there, and I accompanied him. An immense crowd followed in our footsteps. A hundred thousand delirious workers, crowned with green palm-leaves, welcomed us. Soliman could not believe his eyes. The whole city praised the name of Adoniram to the heavens.

— ‘What triumph! How happy he must be!’

— ‘He! That strange genius! That deep and mysterious spirit!... At my request, they summoned him, they sought him, the workmen ran about in every direction... a vain effort! Disdainful of his labours, Adoniram hid himself; he evaded praise: the star was eclipsed. “Come,” said Soliman, “the people’s king has shamed us.” As for me, on leaving the field of genius, my soul was sad and my thoughts filled with thoughts of this mortal, rendered great by his works, greater still by his absence at such a moment.’

— ‘I saw him pass by the other day,’ said a maid of Sheba, ‘the fire in his eyes warmed my cheeks and reddened them: he possesses a king’s majesty.’

— ‘His beauty,’ continued one of her companions, is superior to that of the children of men; his stature is imposing, his appearance dazzling. Such is how I imagine the gods and the genies to be.’

— ‘More than one among you, I suppose, would willingly unite her fate to that of the noble Adoniram?’

— ‘O queen! What are we before the face of so high a personage? His spirit is among the clouds, and his proud heart would not condescend to visit ours.’