Gérard de Nerval

Travels in the Near East (Voyage en Orient, 1843)

Part XIX: Appendices – 9 to 16

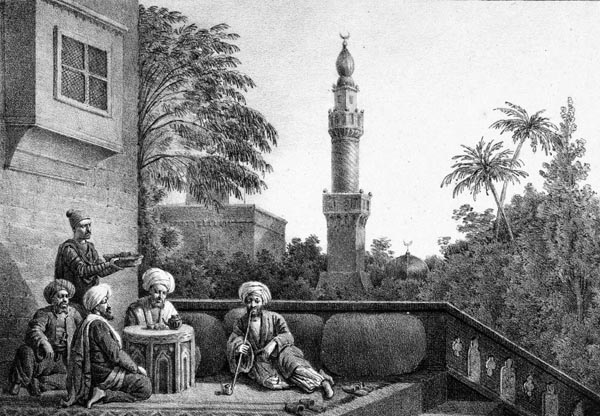

View of a garden near Cairo, 1828, Otto Baron Howen

Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Appendices On Various Topics Regarding the Near East.

- Appendix 9: The Art of Painting Amongst the Turks.

- Appendix 10: Egyptian Domestic Life.

- Appendix 11: The Festival of the Prophet (Mouled-el-Nebi).

- Appendix 12: The Beguines.

- Appendix 13: The Arts in Constantinople and the Near East.

- Appendix 14: Amrou’s Letter.

- Appendix 15: The Catechism of the Druze.

- Appendix 16: Letter to Théophile Gautier.

Appendices On Various Topics Regarding the Near East

Appendix 9: The Art of Painting Amongst the Turks

The Turks lack the art of painting, at least in the true meaning of the word. This is due, as is known, to a religious prejudice which, however, the Persians, and other Muslims of the sect of Ali (the Shia), do not appear to share. Persian paintings are well known from manuscripts, boxes, small ornamental objects, and even shawls and silks, which portray admirable and attractive subjects, generally representing hunting scenes. The ivory handles of sabres and yatagans are adorned with complex and painstakingly-executed carvings, which exactly resemble, often in their costumes, and always in style, our naive sculptures of the Middle Ages, while the paintings recall illustrations from our ancient manuscripts. The Shahnameh (the lengthy epic by the poet Ferdowsi), along with several other historical and religious poems, is decorated with small gouaches representing scenes of battle or ceremonies. Portraits of the prophets are often found in religious books.

There is no article in the Koran which absolutely prohibits the reproduction of figures of men or animals, except to forbid worship of the same. The Mosaic law was far more severe, and only permitted the portrayal of seraphim, and certain sacred beasts, for fear that the people would make an idol of this or that image, be it a calf or a serpent, as they had in the desert.

Nor does it appear that the Arabs always respected this religious scruple, since several Caliphs had their likenesses engraved on coins, or their palaces decorated with tapestries featuring human beings.

Here is a striking example, which I read in a history of the Caliphs, taken from the reign of the eleventh Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate, Al-Mustansir bi-llah (ruled 861-862AD):

‘He became Caliph the day he had his father, Al-Mutawakkil, slain. The people said that he would reign only a short time, and that was the case. The story goes that when Al-Mustansir was Caliph, a figured tapestry was handed to him, in which there was a portrait of a man on horseback, wearing a turban surrounded by a wide band, with writing in Persian. Al-Mustansir sent for a Persian to have the writing translated, the effect of which was to trouble him greatly: “I am,” it read, “Sheroe, son of Chosroes (Khosrow II, King of the Sasanian Empire), who killed my father and enjoyed the kingdom for only six months (as Kavad II, in 628AD).” Al-Mustansir turned pale, and rose from his seat; he was to reign a mere six months also.’

At the Alhambra in Granada, one can see two paintings on vellum, from the time of Muslim rule, which decorate the ceiling of a room. One represents the judgment of the adulterous Sultana (the wife of Boabdil) the other the massacre of the Abencerrages in the Court of the Lions. Théophile Gautier notes that the fountain depicted in this last painting, which is gilded, possesses a different form to that of today.

The Turks have many prejudices peculiar to their race, and to the various religious sects established among them. Such is the one which leads them to build no house of stone or brick, because, they say, a man’s house should not last longer than he does. Constantinople is entirely built of wood, and even the most modern palaces of the Sultan, which have hundreds of marble columns, have wooden walls everywhere, whose decorations alone imitate the tones of stone or marble. In Syria, in Egypt, and everywhere else where Muslim law reigns, but where the Turks nevertheless have only political sovereignty, the cities are built of solid materials, like ours; only the Turk whether Pasha, Bey or simply a rich individual, in possession of the most beautiful of the city palaces, cannot bring himself to dwell amidst stone, and has kiosks built separately of timber, abandoning the rest of the building to his slaves and horses.

Such is the power of certain ideas among the Turks; they own to neither a preoccupation with the future, nor a cult of the past. They are encamped in Europe and Asia-Minor, nothing is truer; always savage like their fore-fathers, the Mongols and the Kyrgyz people, who needed only a tent and a horse wherever they went. They enjoy, their possessions, moreover, without any desire to transmit them onwards, or hope of retaining them. The traveller who passes through their domain swiftly thinks to find among them the traces, or the germs, of science, art, and industry: the traveller is mistaken. The industry in the countries the Turks control is that of the Armenians, Greeks, Jews, and Syrians, the subjects of the empire; their science is that of the Arabs and the Persians, which the Turks have never known how to further. Their literature is limited to a few diplomatic documents, a few weighty historical compilations.

Even their poems, apart from a few pieces of light verse, are scarcely more than translations. Their architecture and ornamentation, borrowed partly from the Byzantines and partly from the Arabs, has not even gained from that mixture a particular and original style. As for the music, it is Wallachian, or Greek, when it is good; the airs regarded as particularly Turkish are simply composed of melodic phrases borrowed at various times from various peoples, and assimilated to Turkish taste through the use of barbarous rhythms and instrumentation.

Let me return to Turkish painting, which may yet own the best title to esteem among civilised nations. Arriving in Egypt full of European prejudice, which supposes that Islam does not allow the depiction of any living being, I was astonished to see, in the cafés, figures of leopards painted in fresco, and fairly well done. My astonishment increased on entering the palace of Mehemet-Ali, and finding first of all a portrait of his grandson hanging on the wall, painted in oil, and rendered with all the artistic skill of Europe; this fails to count as Oriental painting, but demonstrates that among the Turks the representation of figures is not absolutely rejected. I have since discovered the existence in Constantinople of a collection of all the portraits of the Sultans since Osman I and Orhan, his son. None of these sovereigns failed in their desire to transmit their features to posterity; The portraits are all painted in egg-tempera on thin cardboard, with inscriptions of four to five lines on the back of each painting. The whole forms a bound quarto volume. But only the sovereigns enjoyed the privilege of their image being reproduced without fear that it might be the object of cabalistic spells uttered against them, such being the scruple that inhibited many Muslims in the past. The Orientalist, Ignatious d’Ohsson, reports that, towards the end of the last century, there were not two Turks alive, other than the Sultan, who would have dared have themselves portrayed. An eminent person, who collected paintings, but only landscape and marine paintings, and who even then did not show them to his friends (certainly, a singular amateur!), decided to have his portrait done, and to hang it with his other paintings. But, feeling himself growing old, he was best by scruples, and chose to rid himself of the dangerous image by gifting it to a European.

Today, there are still only a few Turks who have portraits made of themselves; but, as one may see, none of them refuse the artists’ wishes, the latter desiring to collect examples of physiognomies or costume; the sitters even preserve their poses with the most perfect patience and a hint of vanity.

The portraits of the Sultans, not only those in the collection cited above, but also those larger items executed on canvas, forming a sort of family tree, which can be seen in one of the buildings of the Seraglio, were painted by Europeans, the Venetians for the most part. Everyone knows the anecdote relating to Gentile Bellini, the fifteenth century artist, of whom our museums possess several canvases representing scenes of ceremonies and receptions by the Ottoman Porte. Sultan Mehmed II, wishing to have himself painted, requested the services of that artist from the Republic of Venice. Gentile Bellini went to Constantinople, painted the portrait of the Sultan, and also several paintings for Christian churches there. It was for one of the latter that he painted a magnificent Beheading of Saint John the Baptist. The Sultan desired to see it, and had the painting brought to him in the Seraglio. It was then that he began with the painter that discussion, famous in the annals of art, concerning the contraction that the skin on the neck of a severed head undergoes, and had a slave decapitated to justify his comments. Gentile Bellini was so frightened by the experience that he hastened to leave for Venice, and never sought to return to Constantinople, although the Sultan requested his service again, from the Signoria of Venice, in the most flattering terms, and in a letter written in his own hand. One can still see today, in the Venetian archives, that which he wrote on the occasion of Gentile Bellini’s departure.

The portraits or figures to be found in Constantinople were not executed by Turkish painters; I even doubt that it is them that we owe a miniature illustrating Muhammad’s Journey to Heaven (Al-Isra’ wal-Mi’raj) which represents the Prophet borne away in the midst of flames on the famous mare Buraq, which is none other than a hippogriff with a woman’s head; four cherubs are part of this assumption, and flutter around the rider, whose face is hidden by a tongue of flame, since it is not permitted, even to the Persians, to represent the features of the Prophet. and this miniature, reproduced in all the manuscripts, of which there is a copy in Paris, must have been the work of a Persian artist.

I have declared what Turkish painting is not; let us see now what it is. I saw my first samples in the palace of Mehmet Ali, several rooms of which offered panels painted in tempera, and exhibiting a skill that barely exceeds that of our dining-room paintings. There were three genres: landscapes, cities, and battle-scenes; but, as it would have been difficult to represent the latter without showing the combatants, preference had been given to naval battles and the bombardment of cities, where, the ships appeared to have declared war on the houses without the help of human beings; cannons fire, bombs burst, buildings burn or collapse, furious fleets engage on the waters, and all this desolation is witnessed only by enormous sea-creatures, painted in the foreground, which jet water through their nostrils unconcerned by the thunderous quarrels of objects less alive than themselves.

Painting sea monsters and even certain animals is thus allowed. Of the latter I only saw examples of lions and leopards. A very well-executed gouache representing one of these animals was sold in Constantinople for two hundred piastres (forty-five francs). During the month of Ramadan, I viewed a collection of three hundred paintings, framed and under glass for the most part, exhibited at the entrance to the wooden bridge which crosses the Golden Horn, on the Galata side. The subjects were a little monotonous, and the execution variable in quality. The religious subjects permitted were limited to two: bird’s-eye views of Mecca and Medina, the two sacred cities, always deserted of people. One may add a few views of mosques. Another subject was portrayed by a prodigious quantity of animals with women’s heads; these are the only human heads which may be depicted. The colour of the eyes, the hair, the form of the face are left to the artist’s fancy. Thus, a Turkish artist cannot paint a portrait of his mistress without giving her the body of a monster. Moreover, this kind of sphinx-painting is most successful and is found in all the barbers’ shops. Genre paintings are limited to the reproduction of landscapes and views. The perspective is sometimes quite well done, and the colours, a little flat, produce an effect somewhat like those of our wallpapers. Marine subjects are still the most numerous. Ships of all kinds, of all flags, squadrons, and sea battles, with monstrous fish swimming on the surface, such is the genre in which the Turkish school flourishes in full freedom. I saw no signs of a steamboat. The Turkish painters are perhaps still somewhat uncertain as to whether a steamboat is, or is not, a living creature. Sometimes one also saw a Dervish’s cylindrical hat (sikke) set on a stool. Finally, some paintings were limited to representing the number of some Ottoman’s house, drawn in various colours, or gilded, and of a large size. Such was the collection, the most complete without doubt that had ever been assembled, which was exhibited in a wooden gallery, guarded by two soldiers, and in front of which an ecstatic crowd was gathered from morning to night.

In the spice-bazaar, the shops of the medicine-sellers and dye-merchants were decorated with similar pictures, which served as shop-signs, several of which, executed in the Turkish taste, were nevertheless done by English painters. The English neglect nothing, and even compete with the poor Turkish artists.

Let us now consider the latter in depth. They generally add to this industry that of paper-making, and occupy small shops located for the most part on Serasker (Beyazit) Square, along which an arcade runs, beneath which one can walk in the shade. The Turks visit these shops to have painted, given the absence of portraiture, their house number accompanied by attributes relating to their profession, or ask for a sketch of a mosque which they particularly admire. One of my friends, the painter Camille Rogier, whom a three-year stay had familiarised with the Turkish language, approached one of these artists, one day, who, seated with legs crossed on the platform of his shop, was drawing for a soldier the mosque of Sultan Bayezid II, located at the other end of the square. The French painter noticed that his colleague was painting the minaret of the mosque in red, which is in fact white, and thought he should advise him. ‘Peki! Peki!’ (‘Very good! Very good!’) he said to him, ‘You draw wonderfully well; but why do you make the minaret red?’ — ‘Do you wish me to do one in which the minaret is blue?’ replied the Turk. — ‘No, but why not make it the colour it is?’ — ‘Because this soldier here likes red, and asked me to paint it in that colour; everyone has a favourite colour, and I try to satisfy all tastes.’

The choice of colours is still, indeed, a matter of Turkish superstition, to the point that the shade of the houses makes it possible to recognise the sect to which each owner belongs. The true believers reserve light colours for themselves, and leave darker shades to the Greeks, Jews, Armenians, and other rayas (non-Muslim subjects).

I have related here all that I know of painting among the Turks. It would be difficult to draw any further interesting detail from a subject so limited that no one has thought of treating it to-date; I wish merely to correct various false ideas, widespread among us, concerning the supposed horror in which Muslims regard images. I have already shown that this prejudice should be attributed to the Turks alone, and that even then it is subject to many exceptions. Nor should one credit the idea that the Turks mutilate images out of religious fanaticism; this can only have happened in the early days of Islam, when it was a question of extirpating idolatry from Asia Minor. The Sphinx to be seen at Gizeh, that colossal sculpture of fine execution, has suffered the mutilation of its nose, because, long after the conquest of Egypt by the Muslims, Sabaeans gathered on certain days in front of the Sphinx to sacrifice white cockerels to it. Moreover, while abstaining from sculpture even more assiduously than painting, the Turks often allowed statues and bas-reliefs to contribute to the ornamentation of their public squares. That of the Atmeidan, which is where the ancient Hippodrome of the Byzantines stood, was decorated for a long time with three bronze statues taken from Buda during a conflict with Hungary. Even today, one may admire, in the centre of the square, a pedestal covered with Byzantine bas-reliefs, which serves as a base for an obelisk and which displays some fifty very well-preserved statues, besides the twisted bronze column depicting three intertwined serpents, the heads of which are missing, which is said to have served as a support for Apollo’s tripod at Delphi, and which can be seen in the same square.

When one traverses the cemeteries of Pera and Scutari for the first time, and views the headstones, one seems to see from afar a whole army, composed, in fact, of white or painted statues scattered amidst the green lawns, in the shade of the enormous cypress trees; some are capped by turbans, others by a modern fez painted red, with golden tassels. They are the height of an ordinary man, in the form of a human body without arms; beneath the head-dress the stone is flat, and covered with inscriptions; bright colours and gilding distinguish the newest and richest. They alone are upright; those of the rayas and the Franks, placed in specific areas of the cemeteries, lie on the ground. These stones are almost images, so much so that after the massacre and proscription of the Janissaries during the reign of Mahmud II, the head, or rather the turban, was struck from all those which indicated the graves of former soldiers of that corps. They are recognisable today by that sacrilegious mutilation.

To complete the story, and exhaust the subject, let me also point to the representation of a golden dove which adorns the prow of the emperor’s caique. In the days of Ignatious d’Ohsson, an eagle decorated the reigning Sultan’s vessel; perhaps the bird’s role was, and is, a symbolic one; in any case, the dove is now the only one which may be displayed. Finally, how may one explain the existence of those little figures which are employed during Ramadan, to people the Karagöz performances? They are both puppets, and Chinese-shadow figures. Their colours stand out perfectly well behind a thin, well-lit canvas, and all the costumes of the different peoples and professions are imitated to perfection, which adds to the attraction of the show; the principal character alone is, like our Punchinello, invariable in his form ... and in his deformity.

Appendix 10: Egyptian Domestic Life

The domestic life of the lower classes is, in general, so simple, compared with that of the higher classes, that it offers very little interest.

Except for a small number of town-dwellers, the lower classes are fellahin (farmers). Those who live in the large towns, and even towns of a lesser extent, as well as a small number of those in the villages, are small-traders, artisans or servants; their wages are small, and generally insufficient to support them and their families.

Their principal food is bread made from millet or maize, milk, soft cheese, eggs, and small salted fish called feseekh. They also eat cucumbers, melons and gourds which are abundant, onions, leeks, beans, chickpeas, lentils, fresh and dried dates, and pickled vegetables. They always eat vegetables raw; the fellahin sometimes feast on ears of nearly-ripe corn which they roast before the fire, or bake in the oven. As far as they are concerned, rice is unaffordable; the same is true of meat.

The great luxury indulged in by these simple people is tobacco, which is inexpensive, since they grow and dry it themselves. The tobacco is greenish, and its aroma quite pleasant.

Although most of the above-mentioned commodities are cheap, the poorest people can hardly procure anything but coarse bread, which they moisten with a mixture called sukkah, which is composed of salt, pepper, and zalaar (a kind of wild marjoram), or else of mint or cumin seed. At every mouthful, the bread is dipped in this mixture. When one considers how limited is the cuisine of the Egyptian fellahin, one is astonished at their healthy appearance, their robust frame, and the amount of work they can bear.

Women of the lower classes are rarely idle, and many of them are devoted to more arduous work than that of the men. Their occupations consist, in particular, of preparing the husband’s food, fetching water, which they carry in large vessels on their heads, spinning cotton, flax, or wool, and making a kind of round, flat cake, composed of cattle dung and chopped straw which they knead together, and which is used for fuel.

It is with this fuel called gelley that the ovens are heated in which food is cooked. Among the lower classes, the subjection of women to their husbands is much greater than in the upper classes. The women are sometimes not allowed to dine with the men, and when they go out in company with their husbands, they almost always walk behind; if there is anything to be carried, it is the woman who is burdened with it.

In the towns, some women have shops where they sell bread, vegetables, etc.; so that they contribute as much and often even more than the husband to the maintenance of the family.

When a poor Egyptian desires to marry, his first care is to pay the dowry, which usually comprises the sum of twenty ryals (from twelve to thirteen francs); if a man sees the possibility of raising a dowry, he does not hesitate to marry, for he needs to labour only a little more to provide for the maintenance of a wife and two or three children. From the age of five or six, children are employed in driving and guarding the herds, and afterwards, until the time when they marry, they help the father in his work in the fields. The poor in Egypt often depend entirely, in their old age, on their children’s support; but many parents are deprived of this help and find themselves reduced to begging, or die of hunger. Not long since the Pasha, when making the journey from Alexandria to Cairo, landed at a village on the banks of the Nile; a poor man there seized the sleeve of the Pasha’s garment, and all the efforts of those present who tried to force him to let go proved in vain. The man complained that, having formerly been at ease, he found himself reduced to the utmost misery, because, having reached old age, his sons had been taken from him to become soldiers. The Pasha, who usually examines, attentively, all requests made to him in person, came to the aid of the unfortunate man, by ordering the richest inhabitant of the village to gift him a cow.

Sometimes a young family is an unbearable burden on poor parents; therefore, children are now and then offered for sale; these offers are made by the mother herself, or by some woman whom the father has entrusted with them; the misery of these poor people must be extreme. If, at her death, a woman leaves one or more un-weaned children, and if the father or other relatives are too poor to provide a wet-nurse, the children are put up for sale, or else exposed at the door of a mosque when the crowd assembles for Friday prayers, and it generally happens that someone, seeing a poor creature thus exposed, is moved with compassion, and carries it away to be raised in the family, not as a slave, but as an adopted child; if this fails to happen, the child is entrusted to some person, until an adoptive father or mother can be found.

Some time ago a woman offered a lady a child born a few days previously, which the woman claimed to have found at the door of a mosque. The lady told her that she was willing to raise it, for the love of Allah, in the hope that her own child, whom she cherished, would be protected from all harm, as a reward for her act of charity; at the same time, she placed ten piastres, then equivalent to two francs and fifty centimes, in the woman’s hand; but she refused the gift. This shows, however, that children are sometimes made an object of sale, and that those who buy them can make slaves of them or resell them. A slave-dealer told me, and other people have confirmed the fact, that several young girls had been given to him for sale, with their full consent. They were persuaded by being shown the rich clothing and luxury objects that would be theirs; they were taught to say that they were foreigners, but that having been brought to Egypt at the age of three or four, had forgotten their mother tongue and only knew Arabic.

It often happens that the fellahin find themselves reduced to a state of poverty so great that they are forced, for financial reasons, to place their sons in a position worse than ordinary slavery. When a village is required to furnish a certain number of recruits, the sheik often follows the path which causes him personally least trouble, that is to say, he enlists the sons of the richest. In these circumstances, a father, in order not to be separated from his son, offers one of the poor villagers twenty-five or fifty francs, in order to procure a replacement, and often succeeds, although the love of the Egyptians for their children is as strong as their filial piety, and they have, in general, a great horror of seeing them enlisted. This is carried to such a dreadful point, that the poor often employ violent means to avoid this misfortune; for example, at the time of the war of 1834, one could hardly find a well-formed young man who did not lack one or more teeth, broken to render them incapable of biting a cartridge, or else they lacked a finger, or an eye had been torn out; there were even examples of both eyes having been gouged out to prevent them from being caught and sent to the army. Old women, and others, make a point of visiting the villages to perform such operations on young men and boys, and sometimes the parents themselves take charge of the operation.

The fellahin of Egypt can scarcely be viewed favourably in respect of their domestic and social condition, and their manners. They bear a great resemblance, in this regard, to their ancestors the Bedouin, without possessing many of the virtues of those desert-dwellers, and, if they do possess them, they are of a defective nature. As regards the faults which they have inherited, these often exercise a fatal influence on their domestic affairs. It is said that the fellahin are descended from the various Arab races who settled in Egypt at various times; separation into different tribes is still observed by the inhabitants of all the villages. The space of time has caused each of the original tribes to be divided into numerous branches; these smaller tribes have distinct names, and the names are often given to the villages or district which they inhabit. Those whose establishment in Egypt is the oldest have retained less of the manners of the early Bedouin, and the purity of the race has been compromised by reciprocal marriages with the Copts who have become proselytes to the Islamic faith, or with their descendants: which renders them despised among the Bedouin tribes more recently established in the country; they consider them among the fellahin, and arrogate to themselves the denomination of Arab or Bedouin. When the latter covet the daughters of the recently established tribes, the fathers have no objection to such a marriage; but they never allow their daughters to marry those whom they call fellahin. If any of their number is killed by a person belonging to an inferior tribe, they kill two, three, and even four of that tribe to avenge him. Homicide is usually punished by the death of one of the murderer’s family, and when the homicide has been committed by a person of a tribe other than that of the victim, it often results in vendettas which frequently turn to open warfare between the respective tribes, often lasting for years. A slight insult, offered by a person of one tribe to a member of another tribe, frequently produces the same consequences.

In many cases, blood-vengeance is exacted a century or more after the murder has been committed, if one or other individual revives its memory after the passage of time appeared to have buried it. There are in Lower Egypt two tribes, the Banu S’ad and Al Haram, who are distinguished by their aggression and rancour (the same is true of the Quays and Yaman of Syria); hence these names are given to any persons or parties living in enmity. It is astonishing that such crimes, which, if they took place anywhere other than in villages, that is to say in the towns or cities of Egypt, would be punished with the sentence of death being executed on several of the persons involved, are tolerated, even today. Blood-vengeance is allowed according to the Koran; but it is recommended that moderation and justice are applied: the small wars that it occasions in our time are therefore contrary to the precept of the Prophet, who says: ‘If two Muslims draw swords against one another, the one who slays, as well as the one who is slain, will be punished by the fires of hell), (See also Sura 5, Al-Ma’idah, verse 45)

In other respects, the fellahin resemble the Bedouin. When a fellahin woman is convicted of infidelity to her husband, he, or the brother of the adulterous woman, throws her into the Nile with a stone about her neck, or, after cutting her in pieces, throws the remains into the river. An unmarried daughter or sister who is guilty of incontinence is almost always punished in the same manner, and the father or brother undertakes the punishment. The parents of such girls are considered more offended than the husband by the wife’s adultery, and, if the appropriate punishment is not exacted following the crime, the family is often despised by the whole tribe.

Appendix 11: The Festival of the Prophet (Mouled-el-Nebi)

At the beginning of the month Rabi Al-Awwal (that is to say the third month), preparations are made to celebrate the anniversary of the birth of the Prophet; and this celebration is called Mouled-el-Nebi. The principal place of the festival is the south-western area of a large space in Cairo called Birket-el-Esbekieh, almost the whole of which becomes a lake during the floods; which has happened several years in a row at the time of the Mouled, celebrated, in those years, at the edge of the lake; when the land is dry, the festival takes place on the bared lake-bed. Large tents called siwans are erected, in most of which Dervishes gather every night, as long as the festival lasts. In the middle of each of these tents, a pole called a saariya (sari) is erected, which is firmly attached with ropes, and to which are hung a dozen or more small lamps; and it is around such poles that a group of fifty or sixty Dervishes range themselves, in a circle, to sing their zikrs (religious songs). Nearby, what is called the ckaim is erected, which consists of four poles erected in the same line, a few yards apart from each other, supported by ropes which pass from one pole to the other and are fixed to the ground at both ends.

On these cords are hung lamps which sometimes represent through their arrangement flowers, lions, etc., and at other times, words, such as the name of Allah, that of Muhammad, or some article of faith, or simply ornaments of pure fancy. The preparations end on the second day of the month, and on the following day begin the ceremonies and rejoicings, which must continue without interruption until the twelfth night of the month; which means, according to the Muslim method of calculation, until the night which precedes the twelfth day, and which is, properly speaking, the night of the Mouled itself. (Author’s note: the twelfth day of Rabi Al-Awwal is also celebrated as the anniversary of the death of Mahomet. It is remarkable that his birth and his death are both related as having taken place on the same day of the same month, and specifically on the same day of the week, Monday.)

During this period of ten days and ten nights, a large part of the population of the metropolis gathers at Esbekieh.

In some parts of the streets adjoining the square there are swings and various other equipment for entertainment, as well as a large number of stalls for the sale of sweets, etc.

I visited a street called Souk-el-Bekry, south of Esbekieh, to see the zikkers (chanters of zikrs, the religious songs) whom I was told gave the finest performance. The streets which we had to traverse to reach the place, were filled with people, and no one was allowed to walk around without a lantern after dark. There were hardly any women to be seen among the spectators.

On the very spot where the zikkers would perform, they had hung a large candelabrum, bearing two or three hundred small glass lamps, superimposed in layers, to form almost a single light. Around this cascade of light, there were also many wooden lanterns, each containing several small lamps similar to those of the large candelabrum.

The zikkers, about thirty in number, sat cross-legged on mats spread for the purpose before the houses on one side of the street, the mats being arranged in the form of an oval. In the midst of this oval were three wax candles, supported by low bases. Most of the zikkers were Ahmed-Dervishes, people of low condition, wretchedly dressed; only a few wore the green turban. At one end of the oval were four singers and four players of a kind of flute called a ney. It was among these last that we succeeded in establishing ourselves to attend the majlis, or gathering, for the performance of the zikr, which I will describe as accurately as possible.

The ceremony, according to my calculation, must have begun about three hours after sunset. The performers first recited the Fatiah together; their leader having cried out first: ‘Al-Fatiah!’ all continued thus: ‘O Allah! favour our lord Muhammad in all the ages; favour our lord Mahomet in the highest degree on the Day of Judgment, and favour all the prophets and apostles among the dwellers in earth and heaven. May God, whose name is praised and blessed, be pleased with our lords and masters Abu-Bakr, Omar, Osman, and Ali of illustrious memory. Allah is our refuge and our excellent guardian. There is no strength nor power except in Allah the high, the great! O God! O our Lord! O you, liberal in forgiveness! O you, the highest of the high! O Allah! — Amen!’

After these songs, the zikkers remained silent for a few minutes; then, resumed singing in a low voice.

This manner of preluding the zikr is common to almost all the orders of dervishes in Egypt, and is called istifta’hhez-zikr. Immediately afterwards, the singers, arranged as above, began the zikr: La illah il Allah (there is no God but Allah), in a slow measure, and bowing twice at each repetition of the La illah il Allah; they continued thus for about a quarter of an hour, and then repeated it for another quarter of an hour with more lively movements, while the murshids sang to the same tune, or with variations, passages from a kind of ode analogous to the Song of Solomon, and generally alluding to the Prophet, as an object of love and praise.

These zikrs continue until the muezzin calls for prayer, while the performers rest between each performance, some drinking coffee, and some others smoking.

It was past midnight when we left the Souk-el-Bekry Street zikr to go to Esbekieh; there, the light of the moon, joined to that of the lamps, produced a singular effect; however, many of those on the ckaim of the saariya, and in the tents had been extinguished; and several people were sleeping on the bare ground, taking their rest there for the night. The zikr of the dervishes around the saariya had ended, and I can only describe the latter according to what I noted on the the following night; for, after having attended several zikrs in the tents, on this night I withdrew.

The next day (the one immediately preceding the night of Mouled) we returned to Esbekieh, about an hour before noon. It was too early for there to be much of a company or entertainment. We saw only a few jugglers, and jesters attempting to gather about them a small circle of spectators. But soon the crowds gradually increased, since the remarkable spectacle, on this day, which every year attracts a multitude of people always amazes. The spectacle is called the dossah (the march). And this is what it consists of:

The sheik of the Saadyeh-Dervishes (the Sayeed, Mohammed El-Meuzela), who is a khatib (preacher) at the Mosque of Sultan Hasan, after having spent, it is said, a part of the preceding night in solitude, while repeating certain prayers, secret invocations, and passages from the Koran, reappears at the mosque, on the Friday, the day preceding the night of the Mouled, to accomplish the customary duties of the dossah. The morning prayers and preaching being over, he leaves the mosque to visit, on horseback, the house of the Sheik-el-Bekry, head of all the orders of Dervishes in Egypt. This house is to the south of Esbekieh, adjoining the square and situated at the south-west corner. On the way, he is joined successively by a crowd of Dervishes from different districts of the metropolis. The Sheik is a white-headed old man of fine stature, whose physiognomy is amiable and intelligent.

On the day of which we speak, he wore a white benieh, and a white skaouk (a cotton cap covered with cloth).

His muslin turban was of such a dark olive-green that it could hardly be distinguished from black, and a white muslin headband crossed his forehead obliquely. The horse he rode was of medium size, and weight. Why I have added the last remark will become apparent.

The Sheik entered the Birket-el-Esbekieh, preceded by a large procession of Dervishes, of whom he was their leader. A short distance from the house of the Sheik-el-Bekry, the procession halted; there followed a considerable number of Dervishes and others. I could not count them, but there were certainly more than sixty; they lay flat on their bellies on the path, in front of the horse mounted by the Sheik. They ranged themselves side by side, as close together as possible, with their legs stretched out, and their foreheads resting on their crossed arms, murmuring without interruption the word Allah! Then twelve Dervishes or more began to run over the backs of their prostrate companions, some of them striking bazes or small drums, which they held in their left hands, and also crying out: Allah! The horse bearing the Sheik hesitated for a few minutes to set hoof on the first of the men lying across its path; but, being urged from behind, it decided to do so, and, without apparent fear, trotted over them all, led by two men who held it on each side, themselves running, one over the feet, the other over the heads of the prostrate men. Immediately there arose a long cry among the spectators of ‘Allah! Allah!’ Not one of the men, thus trampled under the hooves of the horse and the feet of its two guides, appeared injured, and each man, rising with a bound as soon as the animal had passed over him, joined the procession which followed the Sheik. Each had endured the weight of two hooves of the horse, a forefoot, and a hindfoot, without forgetting the feet of the two guides. It is said that these Dervishes, as well as the Sheik, recite certain prayers and invocations the day before, in order to run no risk during this ceremony, and rise again safe and sound. Some, having had the temerity to participate in this devotion without having previously prepared themselves for it, have, on occasion, been killed or cruelly maimed. The success of this religious practice is considered a miracle granted to each Sheikh of Saadyeh (Author’s note: it is said that the second Sheikh of Saadyeh, the immediate successor to the founder of the order, ran his horse over pieces of glass without a single piece being broken.)

A custom followed by some of the Saadyeh, on such occasions is to eat live snakes, before a select gathering in the house of Sheikh-el-Bekry; but the present Sheikh has lately opposed this custom in the metropolis, by declaring it an unpleasant practice and contrary to the religion, which places reptiles among the class of animals that should not be consumed. However, we saw the Sadis more than once eating snakes and scorpions during our first excursion in the countryside. It must be added that the fangs of the snake, which contained the venom, had been removed, and that the creature was incapable of biting, since its jaws were pierced, and a silk cord was passed through them to bind them together, which silk cord was replaced by two silver rings when it was led in procession.

When a Sadi ate the flesh of a live snake, he was, or affected to be, excited by a sort of frenzy. He pressed the tip of his finger hard upon the back of the reptile, seizing it about two inches from the head, and consumed it only as far the place where he had pressed; which required three or four mouthfuls. The rest of the body he threw away.

However, snakes are not always handled without danger, even by Sadis. We were told that some years ago, a Dervish of this sect, who was called El-Fil, or Elephant, on account of his corpulence and muscular strength, and who was the most famous snake-eater of his time, and perhaps all time, having had the desire to tame a snake of a very venomous species which had been brought from the desert, placed this reptile in a basket, and kept it there several days to weaken it; after which, wanting to take it to extract its fangs, he thrust his hand into the basket, and felt himself bitten on the thumb. He called for help; but, as there was only one woman in the house, who was too frightened to come to him, some minutes elapsed before he could obtain assistance, and, by the time they arrived, his whole arm was black and swollen, and the man died after a few hours.

Appendix 12: The Beguines

It is the responsibility of travellers to enlighten the public regarding facts and events which they have observed and which are connected in some way to European society. The trial relating to the Beguine sect, a trial which all the newspapers have reported (January 1851), has given rise to only limited historical research into the origin of this religion.

It seems to me that this sect is not only linked, as has been said, to certain English congregations who preceded the Anabaptists of France and Germany, but that it relates to the very origins of the Christian religion.

There have been found on the coasts of Syria, from Carmel to Tripoli, extant traces of a religion whose followers are called Nazarenes, mainly inhabiting the region between Latakia and Antakia (Laodice and Antioch). The Comte de Volney, who has devoted several pages to this singular sect, calls them Ansaries.

It seems certain that these people believe in the primitive heresies of Christianity. Perhaps one might go back further by connecting them to some Hebrew sect, especially that of the Essenes, which was founded under the influence of certain inspired neighbours of Phoenicia, such as Pythagoras, whose memory is honoured at Carmel, and Elijah, the particular prophet of that mountain.

The hills of Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon contain a large number of these sectarians, who are accused of the same errors as the Beguines of our countries.

It should not be forgotten, moreover, that the primitive Christians were accused in Rome of similar practices, and that these also gave rise to suppositions of immorality.

Among the Nazarenes, we find the same belief in the prophet Elijah, who returns, at certain times, under various incarnations, and who, then, reestablishes neglected dogma. Everything is then permitted to him, as one who represents, at the same time, the prophet and the Divinity. And, though the faithful are generally sworn to continence, his divine character allows him to ignore that oath, when it is a question of begetting the expected Madhi or Messiah.

Their processions take place in the depths of the woods, as among the Beguines of Europe; but there is no question there, as here, of naked men or women. Only retirement at night to temples called kaloues, where the divine service is limited to the reading of the holy book, that is to say of a sort of apocryphal Bible which these people possess. It is true that at one moment of the ceremony, the lights are extinguished, or are reduced to a faint glow; but it has never been proven, even in Syria, that reprehensible acts then take place.

I have heard Egyptian officers, who took part in the occupation of Syria in 1840, express themselves on this subject with some levity. They claimed that once the lights were extinguished, unedifying scenes took place in the kaloue; but we should not trust the ironic claims of these Egyptians any more than that of our Marseillais who, finding themselves in contact with the populations of the lower slopes of Mount Lebanon, have attributed to the ceremonies of this cult a character which is certainly exaggerated. Moreover, it is probable that the cult, passing into our colder countries, was purified there, as happened with primitive Christianity, of which it was an important sect.

Appendix 13: The Arts in Constantinople and the Near East

(Original Editor’s Note: this appendix rounds out Appendix 9: The Art of Painting among the Turks. We thought its handful of repetitions insufficient reason for exclusion.)

There is a prejudice among us which considers the Oriental nations as the enemies of paintings and statues. This is an ancient accusation, akin to that which attributed to Umar’s lieutenant the destruction of the Library of Alexandria, which had been dispersed long before, after the fire which ravaged the Serapeum.

Oriental newspapers have informed us, moreover, that the Sultan has devoted large sums to the restoration of Hagia Sophia. At a time when European civilisation seems little interested in the marvels of artistic imagination and execution, it would be wonderful if the Muses were to find refuge on the shores of the Bosphorus, from whence they visited us. Nothing prevents it, in truth.

We know there are pictures painted on parchment, in the Alhambra of Granada, and that one of the Moorish kings of that city had a statue of his mistress erected in a place called The Garden of the Girl. I have already said that in one of the rooms of the Seraglio in Constantinople there is a collection of portraits of the Sultans, the oldest of which was painted by the Venetian, Gentile Bellini, who had been invited to execute the work, at great expense.

I even took the opportunity to attend an exhibition of paintings which took place in Constantinople, during the Ramadan festivities, in the suburb of Galata, near the entrance to the bridge of boats which crosses the Golden Horn. It must be admitted, however, that this exhibition would have left much to be desired by Parisian critics. Thus, anatomical studies were completely lacking, while landscapes, and still lifes uniformly dominated.

There were five hundred and more pictures, framed in black, which could be divided as follows: religious paintings, battles, landscapes, seascapes, animals. The first consisted of reproductions of the most considerable mosques of the Ottoman Empire; pure architecture, with at most a few trees highlighting the minarets. An indigo sky, an ochre ground, red brick, and grey domes, that was their scope, tyrannised by a sort of hieratic convention. As for the battle-scenes, their execution was singularly hampered by the impossibility established through religious dogma of representing any living creature, be it a horse, a camel, or even a cockroach. This is how Muslim painters handle the matter: they suppose the spectator to be extremely far from the scene of the fight; the folds of ground, mountains, and rivers are alone outlined with a degree of clarity; the layouts of the cities, the angles and lines of the fortifications and trenches, the position of the squares and batteries are indicated with great care; large cannon in the act of being fired, and mortars, from which the fiery curves of the bombs arch, animate the spectacle and represent the action. Sometimes, human beings are indicated by dots. Tents and flags indicate the various nationalities, and a legend written at the bottom of the painting informs the public of the name of the victorious leader. In the naval battles, the effect is more striking due to the presence of fighting vessels, which are relatively animated; these paintings also gain a livelier effect from certain groups of whales and other amphibians which are rendered as spectators of this maritime triumph of the Crescent.

It is, in fact, quite singular to see that Islam only allows the representation of a few creatures, those classified as monsters. Such, for example, is a sort of Sphinx of which one finds representations, by the thousands, in the cafés and barber-shops of Constantinople. It reveals a very beautiful woman’s head on the body of a hippogriff; her black hair in long braids spreads over her back and chest, her tender eyes are rimmed with black, and her arched eyebrows meet on her forehead; the painter is able to grant her the features of his mistress, and all those who see her can see in her the ideal of beauty; for she is, in the end, merely the representation of a celestial creature, Buraq, the steed that carried Muhammad through the heavens.

This is the only study of the figure allowed; a Muslim cannot gift a portrait of himself to his beloved or his parents. However, there is a way in which he may offer them a cherished, and perfectly orthodox, image: which is to have painted in large, or in miniature, on boxes or medallions, the representation of the mosque which pleases him most in Constantinople, or elsewhere. It signifies: ‘There my heart rests, it burns for you beneath the eye of Allah.’ In Serasker Square, near the Bayezit mosque, where doves flutter by the thousands, one comes across a row of small shops occupied by painters and miniaturists. It is there that lovers and faithful spouses go on certain anniversaries and have these sentimental pictures of mosques painted: each give their ideas on the colour and on the features; they usually have a few verses added which depict their feelings.

It is not entirely clear how Muslim orthodoxy deals with the delicately cut and painted puppets used in the representations of Karagöz. It is also worth mentioning certain coins and medals from the past, and even the standards of the ancient militia of the Janissaries, which bore figures of animals. The Sultan’s ship is decorated with a golden eagle with outstretched wings.

By another singular anomaly, it is customary in Cairo to paint the house of every pilgrim who has recently made the journey to Mecca, doubtless with the idea of representing the countries he has seen; for in this circumstance alone they allow themselves to represent characters who, however, are only with difficulty recognisable as living people.

These prejudices against figurative painting exist, as we know, only among the Muslims of the sect of Umar; for those of the sect of Ali display paintings and miniatures of all kinds. We must not therefore accuse Islam as a whole of a disposition fatal to the arts. The source of dispute arises from an interpretation of a holy text which suggests that it is not permitted for man to create forms, since he cannot create souls. An English traveller was once in the process of drawing figures while watched by an Arab out of the desert, who said to him most seriously: ‘When at the Last Judgment all the figures you have created present themselves before you, and Allah says to you: “Here they stand, complaining of their existence, and yet of not being fully alive. You have granted them a body; now grant them a soul!” what will you answer?’ – I will reply to the Creator, said the Englishman: ‘Lord, as for making souls, you acquit yourself too well for me to attempt to emulate you.... But, if these figures seem to you worthy of life, do me the favour of animating them.’

The Arab found this answer satisfactory, or, at least, knew not what to say in response. The English artist’s reply seems to me most ingenious; and, if God wanted, in fact, at the Last Judgment, to give life to all the figures painted or sculpted by the great masters, he might repopulate the world with a crowd of admirable creatures, worthy of dwelling in the New Jerusalem of the Apostle, Saint John.

It is worth noting, moreover, that the Turks respect the artistic monuments in places subject to their power far more than is believed. It is to their tolerance and their respect for antiquities that we owe the conservation of a host of Assyrian, Greek, and Roman sculptures that conflict between the various religions would else have destroyed in the course of the centuries. Whatever may be said, widespread destruction of statues only took place in the early eras of fanaticism, when certain populations alone were suspected of worshipping them as part of their cult. Today, the greatest proof of the tolerance of the Turks, in this regard, is shown by the survival of the obelisk at the centre of Atmeidan Square, opposite the Mosque of Sultan Selim, the base of which is covered with Byzantine bas-reliefs, in which one can distinguish more than sixty perfectly preserved figures. It would be difficult, however, to cite other sculptures of living beings preserved within the city of Constantinople, apart from those contained in the Catholic churches. A complete restoration of Hagia Sophia has, in our day, been executed by the Fossati brothers (Gaspare and Giuseppe), the mosaic figures of the apostles on the dome, having been covered with a protective layer of plaster on which arabesques and flowers have been represented to designs by Antonio Fornari. The Annunciation of the Virgin is only veiled. There is a most interesting work describing this restoration by Francois Noguès (editor of the Journal de Constantinople).

In the Church of the Forty Martyrs, located near the aqueduct of Valens, the mosaic images have also been preserved, although the building is now a mosque.

To finish with the publicly visible figures, I can also mention a certain tavern situated at the far end of Pera, at the edge of a road which separates the suburb from the village of Saint Dimitrios — this road is formed by the bed of a ravine, at the bottom of which flows a stream which becomes a river on rainy days. The location is most picturesque, thanks to the varied view of the hills which extend from the lesser Field of the Dead to the European coast of the Bosphorus. The painted houses, interspersed with greenery, most of them devoted to guinguettes or cafés, stand out by the hundreds on the crests and slopes of the heights. A motley crowd presses around the various establishments of this Muslim Courtille. The pastry-chefs, the food-fryers, the sellers of fruit and watermelons deafen you with their curious cries. One hears the Greek criers selling bunches of grapes for deka paras (ten paras, a little more than a penny), and there are pyramids of corncobs boiled in saffron water. If one enters the tavern, the interior is vast; high galleries with carved wooden balustrades reign around the large room; on the right is the tavern keeper’s counter, where he tirelessly busies himself pouring Tenedos wines into pale glasses with handles, where the pearls of amber liquor hover; at the back are the cook’s stoves, loaded with a multitude of pots of stew. People sit down to dine on small stools, in front of round tables that only rise to knee height; drinkers settle closer to the door or on the benches that surround the room. There, the Greek with his red tarbouch, the Armenian with his long robe and black kalpak, and the Jew with his grey turban, demonstrate their perfect independence from the proscriptions of Muhammad. The complement of this scene is the local decoration that I wish to mention, composed of a series of figures painted in fresco on the wall of the cabaret. It is the representation of a fashionable promenade, which, if we are to believe the costumes, dates back to the end of the last century. One sees there about twenty life-size characters, dressed in the costumes of the various nations that inhabit Constantinople. There is among them a Frenchman in the costume of the Directory period (1795-99), which gives the approximate date of the composition. The colour is perfectly preserved, and the execution not too inadequate, for a neo-Byzantine painting that is. A touch of satire contained within the work indicates that it is not that of a European artist, because one sees a dog raising its paw to spoil the mottled stockings of a dandy; the latter tries without success to push it back with his rattan cane. This is, in truth, the only publicly exhibited figure-painting that I was able to discover in Constantinople. We therefore see that it is not impossible there for an artist to place his talent at the service of innkeepers, as Simon Lantara did in France. It only remains for me to excuse myself for the length of this note, which may at least serve to counter two European prejudices, by proving that there are in Turkish countries both paintings and taverns. Several of our artists do very well there, moreover, by painting portraits of saints for the Armenians and the Greeks of the Fener district.

As for the painting of ornaments, and the design of graceful arabesques, I admit the superiority of the Turks in this respect. The pretty fountain of Tophane will edify travellers as to the genius of ornamentation in Constantinople.

Appendix 14: Amrou’s Letter

The author is motivated by the story of Caliph Hakim to complete his description of modern Cairo with a description of ancient Cairo, animated by memories of its finest historical era.

A document that should not be neglected, one rendering an impression of Egypt after its initial adoption of the Islamic faith, is a letter written by one Amrou (or Gamrou) to the Caliph Umar, at the time of the conquest of the country by the Muslims.

I cannot conclude my remarks on present-day Egypt better than by citing it. This detail also allows me to cover a historical event which seems to have misled many scholars. Jean-Jaques Ampère, who has published a very detailed and important work on Egypt, (‘Voyages et Recherches en Égypte et en Nubie, 1846’) has indulged in the common error which supposes that the Caliph Umar himself laid siege to Alexandria. We will see, from the following, that it was his general Amrou who was charged with that expedition. I have preserved here the style of the seventeenth century Orientalist, Pierre Vattier, who rendered the Arabic style admirably.

Here, first of all, is the letter that the commander of the faithful, Umar, wrote to Amrou (the French language only imperfectly renders the consonances of Arabic):

From Lord Umar, son of Al-Khattab, to Amrou, son of Gase: ‘Allah grant you his peace, O Amrou, and his mercy and his blessings, and grant peace to all Muslims generally! After these events, I thank God for the favour he has shown you; there is no other God than him, and I pray to him to bless Muhammad and his family. I know, O Amrou, from the report that has been made to me, that the province you command is fine and well-fortified, well-cultivated and well-populated; that the Pharaohs and the Amalekites reigned there; that they made exquisite works and excellent things there; that they displayed, there, the marks of their greatness and their pride, imagining themselves to be eternal, and counting on what they should not. Allah, however, has established you in their place, and has granted you power over their goods, their servants, and their children, and has granted you inheritance of their land. May He be praised and blessed and thanked for doing so; it is to him that the honour and glory belong. When you have read this letter of mine, write to me of the particular qualities of Egypt, both inland, and on its shores, and make it known to me as if I were seeing it myself.’

Amrou, having received this letter, and seen what it contained, replied to Umar; in these terms:

From Lord Amrou, son of Gase, son of Vail the Saharan, to the successor of the apostle of God, to whom God grant peace and mercy, Umar, son of Al-Khattab, Commander of the Faithful: ‘O Caliph who follows the straight path, whose letter has been received and read and whose request has been heard, I wish to dispel from your mind the cloud of uncertainty through the truth of my speech. It is from Allah that strength and power derive, and all things return to Him. Know, Lord Commander of the Faithful, that the land of Egypt is nothing but black earth and green vegetation between powdery mountains and red sand. There are between the mountains and the sand raised plains and low eminences. It consists of level strips which provide it with food, and which extend a month’s journey for a man on horseback from Syene (Aswan) to the end of the land, and likewise to the coast. Through the middle of these, and the whole country, flows a river, blessed in the morning, and favoured by heaven in the evening, which increases and decreases in flow, according to the courses of the sun and moon. There exists a season when the fountains and springs of the earth are opened, according to the command given them by its Creator, who governs and dispenses the river’s course to provide food for the province, and it flows, in accord with what has been prescribed, until, its waters being swollen and its waves sounding, and its floods having reached the highest elevation, the inhabitants cannot pass from village to village except in small boats, and these boats are seen moving to and fro, appearing as black and white camels might to the imagination. Then, when it is in this state, behold it begins to withdraw and to close itself up in its channel, as previously it had emerged, rising little by little. And then, the quickest and slowest prepare themselves for work; They spread out in groups over the countryside, the people of the law whom God keeps, and the men of the alliance whom men protect; one sees them walking like ants, some weak, others strong, and wearying themselves in the tasks that have been given them. We see them ploughing the earth which the river has moistened, and sowing all kinds of seed that they hope to be able to multiply with the help of Allah; and the earth does not delay, black from its watering, to clothe itself with green and to spread a pleasant odour, as it produces stems and leaves, and ears, making a beautiful show and giving hope of good harvest, the dew watering it from above, and the humidity giving nourishment to its produce from below. Sometimes, a few clouds bring moderate rain; sometimes, only a few drops of water fall, and, sometimes, none at all. After this, Lord Commander of the Faithful, the earth displays its beauties, and parades its graces, rejoicing its inhabitants and assuring them of the harvest of its fruits, for their sustenance and that of their mounts, bearing more, and multiplying their livestock. It appears now, Lord Commander of the Faithful, like a dusty plain, then immediately like a bluish sea; now like a white pearl, now like black mud, then like green taffeta, then like an embroidery of various colours, then like an outpouring of red gold. Then, they harvest their wheat, and they thresh it to extract the grain, which then passes variously between the hands of men, some taking what belongs to them, and others what does not belong to them. This vicissitude returns every year, each thing in its time, according to the order and providence of the Almighty: may He be praised forever this great God, may He be blessed, the best of creators! As for what is necessary for the maintenance of these things, and to render the country well-populated and well-cultivated, to preserve it in good condition and advance it from good to better, according to what we have been told by those who know, having had the government in their hands, I note three things in particular: the first of which is not to hearken to the ill speeches the rabble make against the principal people of the country, for they are envious, and ungrateful for the good that is done them; the second is to employ a third of the tribute levied on the upkeep of bridges and roads: and the third is not to extract tribute of any particular sort, except from that same when it is abundant. This is a description of Egypt, Lord Commander of the Faithful, by means of which you may know it as if you had seen it yourself. Allah maintain you in your righteous conduct, and see you govern your empire in happiness, and help you to discharge the burden that He has imposed on you. Peace be with you. May Allah be praised, and may He assist with his favour and blessing our lord Muhammad, and those of his nation, and those of his party.’

The commander of the faithful, Umar, having read Amrou’s letter, spoke thus, says the author: ‘He has acquitted himself well in describing the land of Egypt and its attributes; he has depicted it so well, that his letter should not be ignored by those who are capable of knowledge. Praised be Allah, O assembly of Muslims, for the grace He has shown you in granting you possession of Egypt, and other lands! It is him whose help we should implore.’

Appendix 15: The Catechism of the Druze

Question. ‘You are a Druze?’ — Answer. ‘Yes, by the help of our Almighty Master.’

Q. ‘What is a Druze?’ — A. ‘One who obeys the law, and worships the Creator.’

Q. ‘What does the Creator command of you?’ — A. ‘Truthfulness, observance of His worship and observance of the seven conditions.’

Q. ‘What are the harsh duties from which your Lord has exempted you, and which He has abrogated; and how do you know that you are a true Druze?’ — A. ‘Abstaining from what is unlawful; and by doing what is lawful.’

Q. ‘What is lawful and unlawful?’ — A. ‘Lawful is that which belongs to the priesthood and to agriculture; and unlawful, to temporal places, and renegades.’

Q. ‘When and how did our Mighty Lord arrive?’ — A. ‘In the year 400 of the Hegira (Hijra) of Muhammad. He was then said to be of the race of Muhammad to hide his divinity.’

D. ‘And why did he wish to hide his divinity?’ — A. ‘Because his worship was neglected, and those who worshipped him were few in number.’

Q. ‘When did he appear and manifest his divinity?’— A. ‘In the year 408.’

Q. ‘How long did he remain thus?’ — A. ‘The whole of the year 408; then he disappeared in the year 409, because it was a disastrous year. Then he reappeared at the beginning of 410, and remained the whole of the year 411; and finally, at the beginning of 412, he hid himself from sight, and will not return again until the Day of Judgment.’

Q. ‘What is the Day of Judgment?’ — A. ‘It is the day when the Creator will appear in human form and will reign over the universe with power and the sword.’

Q. ‘When will this be?’ — A. ‘That is unknown; but signs will declare it.’

Q. ‘What will these signs be?’ — A. ‘When we see a change of kings, and the Christians gain advantage over the Muslims.

Q. ‘In which month will this take place?’ — A. ‘In the moon of Jumada al-Thani, or in that of Rajab, according to the calculations of the Hegira.’

Q. ‘How will God govern peoples and kings?’ — A. ‘He will manifest himself by power and the sword, and will take away the life of them all.’

Q. ‘And after their death, what will happen?’ — A. ‘They will be reborn at the command of the Almighty, who will order them as he pleases.’

Q. ‘How will he treat them?’ — A. ‘They will be divided into four parts; namely, the Christians, the Jews, the renegades, and the true worshippers of God.’

Q. ‘And how will each of these sects be divided?’ — A. ‘The Christians will give birth to the sects of the Nazarenes (of Lebanon, in the provinces of Tripoli and Sidon) and the Metuali (Shia Muslims); from the Jews will derive the Turks. As for the renegades, they are those who have abandoned faith in our God.’

Q. ‘What treatment will God grant the worshippers of his unity?’ — A. ‘He will grant them empire, royalty, sovereignty, goods, gold, silver, and they will dwell in the world as princes, pashas and sultans.’

Q. ‘And the renegades?’ — A. ‘Their punishment will be dreadful. Their food and water, when they wish to eat and drink, will be bitter. Moreover, they will be reduced to slavery and subjected to the harshest labour amidst the true worshippers of God. The Jews and Christians will suffer similar torments, but much lighter in degree.’

Q. ‘How many times did Our Lord appear in human form?’ — A. ‘Ten times, which are called stations, and the names that he bore successively were: El-Ali, El-Bar, Alia, El-Maalla, El-Kaiem, El-Maas, El-Azis, Abazakaria, El-Mansour, and El-Hakem.’

Q. ‘Where did the first station, that of El-Ali, take place?’— A. ‘In a city in India, called Rchine-ma-Tchine.’

Q. ‘How many times did Hamza appear, and what was his name at each appearance?’— A. ‘He appeared seven times in the ages that have passed from Adam to the prophet Samed. In the age of Adam, his name was Chattnil; in that of Noah, his name was Pythagoras; David was the name he bore in the time of Abraham; in the time of Moses, his name was Shaib, and in that of Jesus, he was called the true Messiah and also Lazarus; in the days of Muhammad, his name was Salman-el-Farsi, and in the time of Sayd his name was Saleh.’

Q. ‘Teach me the etymology of the name Druze.’ — A. ‘The name is derived from our obedience to the Hakem by the order of God, which Hakem is our master Muhammad, son of Ishmael, who manifested himself by himself to himself; and when he had manifested himself, the Druze, by following his orders, entered into his law, which made them Druze: for the Arabic word enderaz, or endaradj, is the same as dakhala, which signifies to enter. It signifies that the Druze wrote the law, became imbued with it, and entered the state of obedience to the Hakem. Another etymology may be found by writing Druse with an s; then, it comes from darassa, iedros, to study, which signifies that the Druze studied the books of Hamza, and worshipped the Almighty, as is fitting.’

Q. ‘What is our intention in adoring the Gospel?’— A. ‘Know that we thereby wish to exalt the name of him who upholds the command of God, and that is Hamza; for he it is who uttered the Gospel. Moreover, it is fitting that in the eyes of every nation we should acknowledge their belief. Finally, we worship the Gospel, because it is founded on divine wisdom, and contains the evident marks of true worship.’

Q. ‘Why do we reject every book other than the Quran (Koran), when we are questioned as to this?’ — A. ‘Because we need not be known as who we are, when amidst the followers of Islam. It is therefore appropriate that we recognise the book of Muhammad; and, so we may not be treated badly, we have adopted all the Muslim ceremonies, even that of the prayers for the dead; and all this only externally, in order to be left untroubled.’

Q. ‘What do we say of those martyrs whose intrepidity and number the Christians so praise?’— A. ‘We say that Hamza did not recognise them, even if their martyrdoms were believed in and attested to by all the historians.’

Q. ‘But if Christians tell us that their faith is not in doubt, because it is supported by stronger and more immediate proofs than the word of Hamza, how do we answer them, and how do we recognise the infallibility of Hamza, the pillar of truth on which our salvation depends?’ — A. ‘By the testimony which he himself gave regarding himself, when he said, in the Epistle of the Commandment and the Defence: “I am the first among the creatures of God; I am his voice and his word; I have knowledge by his command; I am the tower and the well-founded house; I, am the master of death and resurrection; I am he who will sound the trumpet; I am the head of all the priesthood, the master of grace, the edifier, and the dispenser of justice; I am the king of the world, the destroyer of the two testimonies; I am the fire which devours.”’

Q. ‘What is the true religion of the Druze priests?’— A. ‘It is the opposite to every creed of other nations and tribes; and whatever is impious in others, we believe, as has been said in the Epistle of Deception and Warning.’

Q. ‘If a man should come to know our form of holy worship, to believe in it, and conform to it, would he be saved’ — A. ‘Never; the door is closed, the matter is finished, the pen is blunted; and, after his death, his soul will join his original nation and religion.’

Q. ‘When were all souls created?’ — A. ‘They were created after the creation of the pontiff Hamza, son of Ali. After him, God created from light all the spirits which are numbered, and which will neither decrease nor increase until the end of the ages.’

Q. ‘Does our august religion admit the salvation of women?’ A. ‘Without doubt, for Our Lord wrote a chapter on women, and they obeyed at once, as is mentioned in the Epistle of the Law of Women, and it is the same in the Epistle of Daughters.’

Q. ‘What do we say of other nations who claim to worship the Lord who created Heaven and Earth?’ — A. ‘Even if they say that was so, it would be a falsehood; and even if they really worship Him, if they do not know that the Lord is the Hakem Himself, their worship is sacrilegious.’

Q. ‘Who are the elders who preached the wisdom of the Lord to those who established our belief?’ — A. ‘There are three whose names were Hamza, Esmail and Beha-Eddine.’

Q. ‘Into how many parts are the sciences divided?’ — A. ‘Into five parts: two of them belong to religion and two to nature. The fifth part, which is the greatest of all, is not divided. It is the true science, that of the love of God.’

Q. ‘How do we know that a certain man is our brother, an observer of the true worship, if we meet him on the way, or if he approaches us in passing and calls himself a Druze?’ — A. ‘In this manner: after the usual compliments, we say to him: “Is the seed of myrobalan (aliledji) sown in your country?” If he answers: “Yes, it is sown in the hearts of the believers,” then we question him about our faith: if he answers correctly, he is our compatriot; if not, he is merely a stranger.’

Q. ‘Who are the fathers of our religion?’— A. ‘They are the prophets of Hakem, namely: Hamza, Esmail, Muhammad and Kalime, Abou-el-Rheir, and Beha-Eddine.’

Q. ‘Do the ignorant Druze win salvation or employment with the Hakem, when they die in a state of ignorance?’ — A. ‘There is no salvation for them, and they will exist in dishonour and slavery before Our Lord until the eternity of eternities.’

Q. ‘Who is Doumassa?’— A. ‘He is Adam the first; he is Arkhnourh; he is Hermes; he is Edris; John; Esmail, son of Mahomet-el-Taimi; and, in the century of Muhammad, son of Abdallah, he was called El-Mekdad.’

Q. ‘What is the ancient and eternal?’ — A. ‘The ancient is Hamza; the eternal is the soul, his sister.’

Q. ‘What are the feet of wisdom?’— A. ‘The three preachers.’

Q. ‘Who are they?’— A. ‘John, Mark, and Matthew.’

Q. ‘How long did they preach?’ — ‘A. ‘Twenty-one years in total; each of them preached for seven.’

Q. ‘What are those buildings which are in Egypt and which are called the Pyramids?’ — A. ‘The Pyramids were built by the Almighty, to achieve a wise end which he in his providence conceived.’

Q. ‘What was this wise purpose?’ — A. ‘To place there, and preserve there, until the Day of Judgment and His Second Coming, the secrets of and designs for all creatures which His divine hand has composed.’

Q. ‘For what reason did he appear at each new rendering of the law?’ — A. ‘To exalt the worshippers of his true worship, that they might be strengthened in it, that they might know that it is He who dispenses justice, at his will, and that they might believe in none beside Him.’

Q. ‘How do souls return to their bodies?’— A. ‘Whenever a man dies, another is born, and so is the world.’

Q. ‘What is Islam called?’— A. ‘The sending down (el tanzil).’

Q. ‘And Christianity’ — A. ‘The explanation (el taaouil). These two denominations signify, as regards the latter, that it an explanation of the words of the Gospel; as regards the former, the suggestion that the Koran was sent down from heaven.’

Q. ‘What might the will of God have been in creating the genies and angels who are designated in the Book of the Wisdom of Hamza?’ — A. ‘The genies, spirits, and demons are akin to those among men who have not responded to the invitation of Our Lord, the Hakem. The demons are spirits before they acquire bodies. As for the angels, we must view them as a representation of the true worshippers of God, who have obeyed the invitation of the Hakem, who is the Lord worshipped in all the cycles of the ages.’

Q. ‘What are the cycles of the ages?’ — A. ‘They are the virtuous cycles of the prophet, who appears in turn, and to whom the people of the century in which they live bear witness, such as Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, and Sayd. All these prophets are but one and the same soul which has passed from one body into another, and the soul, which is also the cursed demon, the guardian of Ebn-Termahh, and also Adam the disobedient, whom God drove from his paradise, that is to say, from whom God took away the knowledge of His unity.’

Q. ‘What was the role of the devil in Our Lord’s eyes?’— A. ‘He was dear to Him; but he conceived pride and refused to obey the vizier Hamza; then God cursed him and cast him from paradise.’

Q. ‘Who are the chief angels who uphold the throne of Our Lord?’— A. ‘They are the five primates who are named: Gabriel who is Hamza, Michael who is the second brother, Esrafil-Salame-Ebn-Abd-El-ouahab, Esmaïl Beha-Eddin, and Metatroun-Ali-Ebn-Achmet. These are the five viziers who are named also El-Sabek (the forerunner), El-Cani (the second), El-Djassad (the body), El-Rathh (the opener), and Fhial (the horseman).’

Q. ‘Who are the four women?’— A. ‘Their names are Ishmael, Muhammad, Salame, and Ali, and they are named also: El-Kelmé (the word), El-Nafs (the soul), Beha-Eddin (the beauty of religion), and Omm-el-Rheir (the mother of good).’