Gérard de Nerval

Travels in the Near East (Voyage en Orient, 1843)

Part XI: Druze and Maronites (Druses et Maronites) – The History of Caliph Hakim

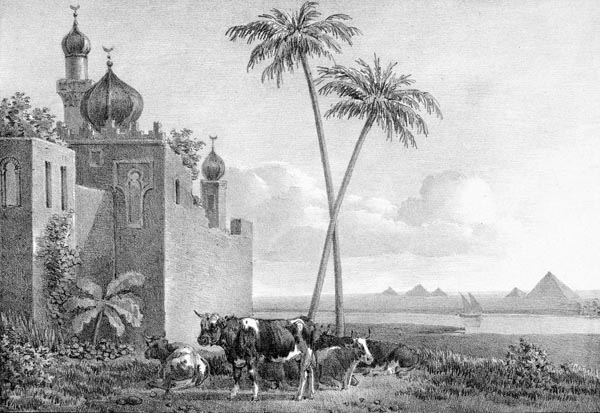

View taken from Roudah Island near Cairo, 1830, Otto Baron Howen

Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter 1: Hashish.

- Chapter 2: The Famine.

- Chapter 3: The ‘Lady of the Kingdom’.

- Chapter 4: The Moristan (The Asylum).

- Chapter 5: The Burning of Cairo.

- Chapter 6: The Two Caliphs.

- Chapter 7: Departure.

Chapter 1: Hashish

On the right bank of the Nile, at some distance from the port of Fustat, where the ruins of old Cairo are sited, and not far from the heights of Mokattam, which dominate the new city, there was, sometime after the year 1000 of the Christian era, which corresponds to the fourth century of the Muslim Hegira (Hijra), a small village inhabited largely by people of the Sabaean sect.

From the last houses that line the river, one enjoys a charming view; the Nile envelops with its caressing waves the island of Roda, which it seems to support like a basket of flowers that a slave might bear in his arms. On the other bank, lies Giza, and, in the evening, when the sun has just disappeared, the pyramids pierce, with their gigantic triangular faces, the band of violet mist of the setting sun. The heads of the doum-palms, the sycamores and the Pharaoh fig-trees are silhouetted in black against this bright background. Herds of buffalo that the Sphinx, recumbent on the plain like a pointing dog, seems to guard from afar, descend in long lines to the watering holes, and the lights of fishermen prick the opaque shadow of the banks with golden stars.

In the village of the Sabaeans, the place where one best enjoyed this perspective was an okel with white walls, surrounded by carob trees, whose terrace had its foot in the water, and where, every night, the boatmen who ascended or descended the Nile could see the night lights flickering in their pools of oil.

Through the bays of the arcades, a curious person, occupying a cange in the middle of the river, would have easily discerned, in the interior of the okel, the travellers and regulars seated at small tables on chairs of palm-wood, or divans covered with mats, and would certainly have been astonished by their odd appearance. Their extravagant gestures, succeeded by a stupefied immobility, their senseless laughter, the inarticulate cries which escaped from time to time from their chests, would have made him think it one of those houses where, outside the barriers, infidels went to intoxicate themselves with wine, bouza (beer) or hashish.

One evening, a boat, steered with the certainty that came from knowledge of the place, reached shore in the shadow of the terrace, at the foot of a staircase whose first steps were kissed by the water, and out sprang a young and handsome man, who seemed a fisherman, and who, climbing the steps with a firm and rapid step, sat down in the corner of the room in a place that seemed his own. No one paid any attention to his arrival; he was evidently a regular.

At the same time, through the opposite door, that is to say from the landward side, entered a man dressed in a black woollen tunic, wearing, in defiance of custom, long hair under a takieh (white cap).

His unexpected appearance provoked some surprise. He seated himself in a corner, in the shadows, and soon, the general drunkenness prevailing, none paid further attention to him. Though his clothes were wretched, the newcomer’s face bore no signs of the anxious humility of poverty. His features, firmly drawn, recalled the severe lines of a lion’s mask. His eyes, dark blue like that of sapphires, had an indefinable power; they frightened and charmed at once.

Yousouf — for such was the name of the young man borne there by the cange — immediately felt a secret empathy in his heart with the stranger whose unusual presence he had noticed. Not having taken part as yet in the drinking, he approached the couch on which the stranger was squatting.

— ‘Brother,’ said Yousouf, ‘you seem tired; doubtless, you have come a long way. Would you like some refreshment?’

— ‘Indeed, my journey has been long,’ the stranger replied. ‘I entered this okel to rest; but what might I drink here, where only forbidden beverages are served?’

— ‘You Muslims fear to wet your lips except with pure water; but we, who are of the Sabaean sect, may, without offending our law, quench our thirst with the generous juice of the vine, or the blond liquor fermented from barley.’

— ‘I see no such fermented drink in front of you, though?’

— ‘Oh! I have long since disdained gross drunkenness,’ said Yousouf, beckoning to a black servant, who placed on the table two small glass cups encased in silver filigree, and a box filled with greenish paste in which an ivory spatula had been dipped. ‘This box contains the paradise (Jannah) promised by your Prophet to true believers, and if you were not so scrupulous, I would set you in the arms of the houris, in a trice, without requiring you to cross the bridge of As-Sirat,’ continued Yousouf, laughing.

— ‘But this paste is hashish, if I’m not mistaken,’ replied the stranger, pushing away the cup in which Yousouf had placed a portion of this magical substance, ‘and hashish is prohibited.’

— ‘Everything that is pleasant is forbidden,’ said Yousouf, swallowing a first spoonful.

The stranger fixed the gaze of his deeply azure eyes on Yousouf; the skin of his forehead contracted in such violent furrows that his hair followed the undulations; for a moment one would have said that he wanted to rush upon the carefree young man, and tear him to pieces; but he restrained himself, his features relaxed, and, in a sudden change of mind, he stretched out his hand, took the cup, and began to slowly taste the green paste.

After a few minutes the effects of the hashish began to be felt on both Yousouf and the stranger; a sweet languor spread through all their members, a vague smile fluttered on their lips. Although they had barely spent half an hour with each other, it seemed to them that they had known each other for a thousand years. The drug acting with more force on them, they began to laugh, become agitated, and speak with extreme volubility, the stranger especially, who, a strict observer of the injunction, had never tasted this preparation and felt its effects keenly. He seemed in the grip of an extraordinary exaltation; swarms of new, unheard of, inconceivable thoughts, traversed his soul in whirlwinds of fire; his eyes glittered as if illuminated internally by the reflections of an unknown world, a superhuman dignity elevated his bearing; then the vision died, and he let himself fall limply to the tiles, amidst all the beatitudes of kief (rest).

— ‘Well, friend,’ said Yousouf, seizing this pause in the unknown man’s intoxication, ‘what do you think of this honest candied pistachio? Will you anathematise, now, good folk who meet quietly in some low-ceilinged room to find happiness in their own manner?’

— ‘Hashish renders one like God,’ the stranger answered in a slow, deep voice.

— ‘Yes,’ replied Yousouf enthusiastically, ‘drinkers of water know only the gross and material appearances of things. Intoxication, by rousing the body’s powers of sight, enlightens the soul; the spirit, freed from the body, its burdensome gaoler, flees like a prisoner whose guard has fallen asleep and left the key in the door of the dungeon. It wanders joyfully and freely in space and light, chatting familiarly with the spirits it meets, who dazzle him with sudden and charming revelations. It traverses, with light flaps of its wings, the atmosphere of unspeakable happiness, and this, in the space of a moment which seems eternal, so quickly do these sensations succeed one another. As for me, I have a dream which constantly reappears, ever the same and ever varying: when I retire to my cange, staggered by the splendour of my visions, closing my eyelids to a perpetual stream of hyacinths, garnets, emeralds, and rubies which form the background on which hashish draws its marvellous fantasies... as at the heart of infinity, I perceive a celestial figure, more beautiful than all the creations of the poets, who smiles at me with a penetrating sweetness, and who descends from the heavens to visit me. Is it an angel, a peri (a supernatural being)? I know not. She seats herself beside me in the boat, whose coarse wood immediately changes into mother-of-pearl, which floats on a silver river, moved by a breeze laden with perfumes.’

— ‘A happy and singular vision!’ murmured the stranger, shaking his head.

— ‘That is not all,’ continued Yousouf. ‘One night, having taken a weaker dose, I woke from my drunkenness, as my cange was passing the tip of the island of Roda. A woman like to the one in my dream leant over me with eyes that, though seemingly human, possessed no less than celestial brilliance; her half-open veil displayed her vest whose gems blazed in the moonlight. My hand met hers; her skin soft, unctuous and fresh as a flower petal, and her rings, whose carved surfaces brushed me, convinced me of her reality.’

— ‘Near the island of Roda?’ the stranger said to himself with a meditative air.

— ‘It was no dream,’ Yousouf continued, paying no attention to the impromptu remark of his confidant, ‘the hashish had simply aroused a memory buried deep in my soul, for this divine face was known to me. However, where I had seen her before, in what world we had met, what previous existence had brought us into contact, that I could not say; but this strange rapprochement, this bizarre adventure, caused me no surprise: it seemed quite natural to me that this woman, who so completely realised my ideal, should find herself there in my cange, in the middle of the Nile, as if sprung from the calyx of one of those large flowers that rise to the surface of the waters. Without seeking an explanation, I threw myself at her feet, and as, at the end of my dream, I addressed her in speech full of all that love in its exaltation can imagine of the most burning and sublime, words of profound significance arose in me, expressions that contained universes of thought, mysterious phrases in which the echo of vanished worlds vibrated. My soul occupied both the past and the future; I was convinced that the love I expressed I had felt from all eternity. As I spoke, I saw her large eyes brighten, and shed effluvia; her translucent hands stretched out towards me, tapering into rays of light. I felt myself enveloped in a network of flames, and I fell, in spite of my previous ecstasy, into dream. When I could shake off the invincible and delicious torpor that bound my limbs, I found myself on the shore opposite Giza, leaning against a palm-tree, and my black slave was sleeping peacefully beside the cange he had drawn up on the sand. A pink glow fringed the horizon; dawn was breaking.’

— ‘This is a love that hardly resembles earthly love,’ said the stranger, without raising the slightest objection to the impossibilities of Yousouf’s story, ‘though hashish easily makes one believe in marvels.’

— ‘I have never before told this incredible story to anyone. Why have I confided it to you, whom I have never seen before? It is difficult to explain. A mysterious attraction draws me to you. When you entered this room, a voice cried out in my soul: “Here he is, at last!” Your arrival has calmed a secret anxiety that left me no peace. You are the one I awaited, without knowing it. My thoughts rushed to meet you, and I have been driven to tell you all the mysteries of my heart.’

— ‘What you feel,’ replied the stranger, ‘I also feel, and I will tell you what I have not even dared to admit to myself until now. You are possessed by an impossible love; I too am possessed, by a monstrous passion! You love a peri; I love ... you will shudder ... my own sister! Yet, strangely enough, I feel no remorse for this forbidden aspiration; though I condemn myself, I am absolved by a mysterious power that I feel within. My love involves no earthly impurity. It is not voluptuousness that drives me to love my sister, though she equals in beauty the phantom of my visions; it is an indefinable attraction, an affection as deep as the sea, as vast as the sky, and such as a god might feel. The idea that my sister could unite with a man inspires in me disgust and horror like a sacrilege; there is something celestial in her that I perceive through the veils of the flesh. Despite the name by which she is called on Earth, she is the spouse of my divine soul, the virgin who was destined for me from the first days of creation; at times, I believe I grasp, through the aeons and the darkness, scenes of our secret affiliation. Landscapes that existed before the appearance of humankind on Earth appear to my memory, and I see myself under the golden branches of Eden, seated beside her, and served by obedient spirits. In uniting myself with another woman, I would fear to prostitute and ruin the soul of the world that beats within me. By the concentration of our divine blood, I would seek to obtain an immortal race, an ultimate god, more powerful than all those who have manifested themselves till now under various names and various masks!’

While Yousouf and the stranger were exchanging these lengthy confidences, the regulars within the okel, agitated by drunkenness, gave themselves over to extravagant contortions, senseless laughter, ecstatic swoons, and convulsive dances; but little by little, the strength of the hemp having dissipated, calm returned to them, and they sprawled across the divans in that state of prostration which ordinarily follows such excess.

A patriarchal-seeming man, his beard streaming down his trailing robe, entered the okel and advanced to the centre of the room.

— ‘My brothers, rise up,’ he cried in a sonorous voice; I have observed the heavens; the hour is favourable to our sacrificing a white rooster before the Sphinx, in honour of Hermes, and Agathos Dæmon (a Graeco-Egyptian god of the household, and protector of the city of Alexandria)’.

The Sabaeans rose to their feet and seemed about to follow their priest; but the stranger, on hearing this proposal, changed colour two or three times: the blue of his eyes became black, terrible furrows traversed his brow, and a dull roar escaped from his breast which made the gathering shudder with fear, as if a real lion had appeared in the midst of the okel.

— ‘Impious wretches! Blasphemers! Vile brutes! Worshippers of idols!’ he cried in a voice that echoed like thunder.

This explosion of anger was followed by a moment of stupor as regards the crowd. The stranger had such an air of authority, and raised the folds of his garment with such proud gestures, that no one dared respond to his insults.

Then the old man approached him, saying:

— ‘What harm do you find, brother, in sacrificing a rooster, according to the rites, to the good spirits Hermes and Agathos Dæmon?

The stranger gritted his teeth on hearing those two names.

— ‘If you do not share the beliefs of the Sabaeans, why are you here? Are you a follower of Jesus or Muhammad?’ asked the old man.

— ‘Muhammad and Jesus are impostors,’ cried the stranger with incredible blasphemous power.

— ‘No doubt you follow the religion of the Parsees, you worship fire....’

— ‘Phantoms, mockery, lies, all such!’ interrupted the man in the black robe with redoubled indignation.

— ‘Then, whom do you worship?’

— ‘He asks me whom I worship!... I worship none, for I myself am God! The only, the true, the unique God, of whom the others are mere shadows.’

At this inconceivable, unheard-of, wild assertion, the Sabaeans threw themselves upon the blasphemer, whom they would have treated harshly, if Yousuf, covering him with his body, had not dragged him backwards onto the terrace bathed by the Nile, though the man struggled and shouted like a madman. Then, with a vigorous kick against the shore, Yousuf drove the boat into the middle of the river.

When they had caught the current, he said to his new-found friend:

— ‘Where should I take you?’

— ‘There, to the island of Roda, where you see those lights gleaming,’ replied the stranger, whose exaltation had been calmed by the night air.

In a few strokes of the oars, they reached the shore, and the man in the black robe, before jumping ashore, said to his saviour, while offering him a ring of ancient workmanship that he took from his finger:

— ‘Wherever you meet me, you have only to show me this ring, and I will perform your wish.’

Then he walked away, and vanished beneath the trees that lined the river. To recover time lost, Yousouf, desiring to attend the sacrifice of the rooster, began to strike the water of the Nile with his oar, with redoubled energy.

Chapter 2: The Famine

A few days later, the Caliph Hakim left his palace as usual to visit the Mokattam observatory. All were accustomed to see him emerge like this, from time to time, mounted on a donkey, and accompanied by a single slave, a mute. It was supposed that he spent the night contemplating the stars, for he was seen to return at daybreak in the same manner, which astonished his servants less, in that his father, al-Aziz Billah (Abu Mansur Nizar, the fifth Fatimid caliph), and his grandfather, Moezzeldin (Abu Tamim Ma’ad al-Mu’izz li-Din Allah, the fourth Fatimid caliph) the founder of Cairo, had done so, both being well versed in the cabalistic sciences; but the Caliph Hakim, after having observed the disposition of the stars and understood that no danger immediately threatened him, would remove his ordinary clothing, don those of the slave, who remained awaiting him in the observatory tower, and, having blackened his face a little so as to disguise his features, descend to the city to mingle with the people and learn their secrets from which he later profited as sovereign. It was wearing such a disguise that he had recently introduced himself into that okel of the Sabaeans.

This time, Hakem went down to Rumaila Square (Salah al-Din Square), the place in Cairo where the population formed the most animated of crowds: they gathered in the shops and under the trees to listen to, or recite, stories and poems, while consuming sugared drinks, lemonades, and candied fruit. The jugglers, the almahs, and the tamers of animals, readily attracted an audience eager to amuse themselves after the day’s work; but, that evening, all was changed, the people presenting the aspect of a stormy sea with its swells, and breakers. Sinister voices here and there raised themselves above the tumult, and speeches full of bitterness resounded from all sides. The Caliph listened, and heard everywhere this exclamation:

— ‘The public granaries are empty!’

In fact, for some time, a serious famine had been afflicting the population; the hope of soon seeing wheat arrive from Upper Egypt had temporarily calmed their fears: everyone managed their resources as best they could; however, that day, the caravan from Syria having arrived bringing many a newcomer, it had become almost impossible to feed oneself, and a large crowd, excited by the arrival of these foreigners had hastened to the public granaries of old Cairo, their last recourse in the worst famines. A tenth of each harvest was heaped up there in immense enclosures with high walls, built long ago by Amr ibn al-As. On the orders of the conqueror of Egypt, these granaries were left unroofed, so that the birds might take their share. This pious arrangement had since been respected, which usually resulted in only a small part of the reserve being lost, and seemed to bring the city good fortune; but, on that day, when the furious people demanded that grain be delivered to them, the employees replied that flocks of birds had arrived, and devoured everything. At this, the people believed themselves threatened with the greatest of evils, and, from that moment, consternation reigned everywhere.

— ‘How is it,’ said Hakim to himself, ‘that I knew nothing of all this? How is it possible this prodigy has appeared? I would have read a prophecy of this occurrence in the stars; yet nothing has disturbed the pentagram I have traced, either.’

He was engaged in this meditation when an old man, who wore Syrian costume approached him, saying:

— ‘Why don’t you give them bread, lord?’

Hakim raised his head in astonishment, and fixed his lion’s eye on the stranger, believing that the man had recognised him despite his disguise.

But the man was blind.

— ‘Are you mad,’ cried Hakim, ‘to address such words to someone you cannot see, whose footsteps you have merely heard in the dust!

— ‘All men,’ said the old man, ‘are blind, before God.’

— ‘So it is to God that you are speaking?’

— ‘I speak to you, Lord.’

Hakim thought for a moment, and his thoughts swirled as if again intoxicated by hashish.

— ‘Save them,’ said the old man, ‘for you alone possess the power, you alone are life, you alone command the will!’

— ‘Do you think I can create grain, here and now?’ replied Hakim, prey to a vague thought.

— ‘The sun cannot shine through cloud; it slowly dissipates it. The cloud that veils you at this moment is the body into which you have deigned to descend, and which can only act with human force. Each being is subject to the law of things ordained by God; God alone obeys only the laws he makes for himself. The world, which he formed with cabalistic art, would dissolve instantly, if his will failed.’

— ‘I see,’ said the Caliph, with a rational effort, ‘that you are merely a beggar; you have recognised who I am under this disguise, but your words of flattery are crude. Here is a purse of gold; leave me be.’

— ‘I know not what your condition is, Lord, for I see only with the eyes of the soul. As for gold, I am versed in alchemy, and I know how to create it when I need it; give the purse to your people. Bread is dear; but, in this good city of Cairo, with gold, one can buy everything.’

— ‘This is some necromancer,’ Hakim thought.

Meanwhile the crowd gathered the coins the old Syrian now scattered on the ground, and rushed to the nearest baker. That day, a mere ocque (three pounds) of bread cost a gold coin (sequin).

— Ah! Is it so? said Hakim. ‘I understand! This old man, who comes from the land of the wise, recognised me and spoke to me in allegories. The Caliph is the image of God; I must enact punishment as God does.’

He went to the citadel, and found the officer of the guard, Abou-Arous, who was in his confidence as regards his disguise. He told this officer, and the executioner, to follow him, as he had already done on several occasions, being fond, like most oriental princes of summary justice; he led them to the house of the baker who sold his bread for its weight in gold.

— ‘Here is a thief,’ he said to the officer of the guard.

— ‘Then,’ said the latter, ‘we should nail his ear to the shutter of his shop?’

— ‘Indeed,’ said the caliph, ‘but after his head has been severed.’

The people, who had not expected such a thing, gathered joyfully in the street, while the baker protested his innocence in vain. The caliph, wrapped in a black abaya which he had taken from the citadel, seemed to fulfil the functions of a simple cadi (judge)’.

The baker was on his knees and stretched out his neck, commending his soul to the angels Munkar and Nakir (the interrogators of the dead). At that moment, a young man parted the crowd and ran towards Hakim, showing him his antique silver ring. It was Yousouf the Sabaean.

— ‘Grant me,’ he cried, ‘this man’s pardon. Hakim recognised his friend from the banks of the Nile and remembered his promise. He made a sign; the executioner released the baker, who rose joyfully. Hakim, hearing murmurs among the disappointed crowd, said a few words in the ear of the officer of the guard, who called aloud:

— ‘The sword is suspended until tomorrow at this time. Then, each baker must sell his bread at the price of ten ocques per gold sequin.’

— ‘I understood, from our meeting the other day,’ the Sabaean said to Hakim, ‘that you are a man of justice, on seeing your anger directed at drink which is forbidden; also, this ring grants me your favour, which I will seek to invoke from time to time.’

— ‘My brother, you have spoken truly,’ replied the Caliph, embracing him. ‘Now my labour is over; let us go and enjoy a little hashish, in the okel of your Sabaeans.’

Chapter 3: The ‘Lady of the Kingdom’

When he entered the house, Yousuf took the owner of the okel aside, and asked him to excuse his friend for the behaviour he had displayed a few days previously.

— ‘Everyone, he said, displays some peculiar obsession when intoxicated; his is to claim to be a god!’

This explanation was delivered to the regulars, who seemed satisfied, and the two friends sat down in the same place as the day before; the little black servant brought them the box that contained the intoxicating paste, and they each took a dose which soon produced its effect; but the Caliph, instead of abandoning himself to hallucinatory fancies, broke into extravagant speech, and rose, as if thrust forward by the steely arm of his fixed idea; an immutable resolution gripped his large, firmly sculpted features, and, in a voice whose tone was that of irresistible authority, he said to Yousouf:

— ‘Brother, you must take the cange, and bear me to the place where you landed me yesterday, on Roda Island, near the terraced gardens.’

At this unexpected order, Yousouf felt vague protests rise to his lips which he was unable to formulate, though it seemed strange to him to leave the okel precisely when the beatitudes hashish presented demanded rest on some divan, so as to progress at their ease; but such strength of will was shown in the Caliph’s eye that the young man silently descended to his cange. Hakim sat down near the prow, and Yousouf bent over the oar. The Caliph, who, during this short journey, had exhibited signs of the most violent exaltation, leapt ashore without waiting for the boat to draw up alongside, and dismissed his friend with a majestic and regal gesture. Yousouf returned to the okel, while the prince took the road to the palace.

He entered by a postern whose secret spring he touched, and soon found himself, after traversing various dark corridors, in the midst of his own apartments, where his sudden appearance surprised his people, accustomed to seeing him return only at the first light of day. His face illuminated by bright rays, his gait at once awkward and stiff, and his strange gestures, inspired a vague terror in the eunuchs; they imagined that something extraordinary was about to occur in the palace, and, standing back against the walls, with heads bowed and arms crossed, they awaited events in a state of respectful anxiety. Hakim’s judgements were known to be prompt, terrible and without apparent motive. Everyone trembled, for no one felt free of guilt.

Hakim, however, ordered no heads to fall. A more serious thought occupied him, entirely; neglecting these details of minor justice, he went to the apartment of his sister, Princess Setalmulc, an action contrary to all Muslim custom, and, raising a curtain, entered the first room, to the great fright of the eunuchs, and the princess’s women who hastily veiled their faces.

Setalmulc (the name means the Lady of the Kingdom, Sitt al Mulk) was seated at the rear of the secluded room, on a tiled seat that filled an alcove let into the thickness of the wall; the interior of this room dazzled by its magnificence. The vault, separated into small domes, offered the appearance of a honeycomb or a cave full of stalactites, due to the ingenious and skilled complexities of its ornamentation, where red, green, azure, and gold mingled their brilliant hues. Glass mosaics covered the walls, at the height of a person, with splendid plaques; pierced heart-shaped arches, rose gracefully from flared capitals in the shape of turbans, supported by marble columns. Along the cornices, door-jambs, and window-frames ran inscriptions in Arabic script whose elegant characters mingled with flowers, foliage and scrolled arabesques. In the centre of the room, an alabaster fountain received in its sculpted basin a jet of water whose crystal jet rose to the vault and fell back, in a fine rain, with a silvery murmur.

At the commotion caused by Hakim’s entrance, Setalmulc rose, anxiously, and took a few steps towards the door. Her majestic figure thus appeared to best advantage, for the Caliph’s sister was the most beautiful princess in the world: eyebrows of velvety black surmounted, with arches of perfect regularity, eyes which made one lower one’s gaze as if one were contemplating the sun; her fine nose with a slightly aquiline curve indicated her royal lineage, and, against her golden pallor, warmed on the cheeks by two small clouds of rouge, her mouth of dazzling purple burst like a pomegranate full of pearls.

Setalmulc’s costume was of an unheard-of richness: a cone of metal, covered with diamonds, supported her veil of gauze speckled with spangles; the velvet of her dress, half-green, half-incarnadine, was well-nigh lost beneath the intricate embroidery. Points of illumination, at the sleeves, elbows, and breast, shed light of a prodigious brilliance, where gold and silver mingled their gleams; her belt, formed of plates of open-worked gold, and studded with enormous rubies, slipped, by virtue of its weight, below her supple and majestic waist, and was held by the opulent contours of her hips. Thus dressed, Setalmulc appeared like the queen of some vanished empire, a queen with gods for ancestors.

The curtain had parted violently, as Hakim appeared on the threshold. At the sight of her brother, Setalmulc could not contain a cry of surprise which was addressed not so much to his unusual actions as the strange aspect of the Caliph. Indeed, Hakim seemed not to be animated by earthly life. His pale complexion reflected the light of another world. Here indeed was the form of the Caliph, yet illuminated by another mind and another soul. His gestures were the gestures of a phantom, and he possessed the air of his own spectre. He rushed towards Setalmulc driven more by will than human articulation, and, as he neared her, he embraced her in a look so deep, so penetrating, so intense, so laden with thought, that the princess shuddered and crossed her arms on her breast, as if an invisible hand had snatched at her clothing.

— ‘Setalmulc,’ cried Hakem, ‘I have long thought of finding you a husband; but no man is worthy of you. Your divine blood shall not suffer any admixture. We must transmit to the future, intact, the treasure we have received from the past. It is I, Hakim, the Caliph, the lord of heaven and earth, who will be your husband: the wedding will take place in three days. Such is my sacred will.’

The princess was so shocked by this unexpected declaration that her reply faltered on her lips; Hakim had spoken with such authority, such utter domination, that Setalmulc felt all objections to be impossible. Without waiting for his sister’s reply, Hakim retreated to the door; then returned to his room, and, overcome by the hashish, the effect of which had reached its highest degree, he let himself fall, a dead weight, on the cushions, and fell asleep.

Immediately after her brother’s departure, Setalmulc summoned the grand vizier Argevan to her, and told him all that had happened. Argevan had been the imperial regent during Hakim’s early youth, the latter having been proclaimed Caliph at eleven years of age; discrete power had remained in Argevan’s hands, and by force of habit he had maintained the attributes of true sovereignty, of which Hakim possessed only the title.

What passed in the mind of Argevan, after the account that Setalmulc gave him of the Caliph’s nocturnal visit, can scarcely be imagined; but who could fathom the secrets of that profound soul? Had not study and meditation thinned his cheeks and darkened his austere gaze? Had not resolution and will-power traced on the lines of his forehead the sinister form of the tau, a sign of destiny? Did the pallor of an immobile mask, which was only occasionally furrowed between the eyebrows, proclaim only that he came from the scorched plains of the Maghreb? The respect he inspired in the population of Cairo, the influence he had gained over the rich and powerful, were they a recognition of no more than the wisdom and justice he brought to the administration of the State?

Setalmulc, raised by him, ever respected him as deeply as she had her father, the previous Caliph. Argevan shared the Sultana’s indignation, saying only:

— ‘Alas! What misfortune for the empire! The Prince of Believers’ reason is obscured.... along with famine, heaven strikes us with yet another scourge. We must order public prayers; our lord is mad!’

— ‘Allah, forbid!’ cried Setalmulc.

— ‘When the Prince of Believers wakes,’ added the vizier, ‘I hope his confusion will have dissipated, and that he will be able, as usual, to preside over the great council.’

Argevan awaited the Caliph’s awakening, at daybreak. The latter did not call his slaves until very late, and was told that the room of the divan was already filled with doctors, lawyers, and cadis. When Hakim entered the room, all prostrated themselves according to custom, and the vizier, rising, gazed at the pensive face of his master with a questioning look.

It did not escape the Caliph. A sort of glacial irony seemed to him to be imprinted on his minister’s features. For some time, the prince had regretted the excessive authority he had allowed inferiors to assume, and, in seeking to act by himself, he was forever surprised by encountering resistance among the ulamas (doctors of law), cachefs (captains), and mouchirs (officers), all devoted to Argevan. It was to escape this tutelage, and in order to judge things for himself, that he had reverted to disguise, and perambulation by night.

The Caliph, seeing that only minor affairs were being discussed, halted the discussion and said in a resounding voice:

— ‘Let us talk a little about the famine; I promised myself that today I would have all the bakers beheaded.’

An old man stood up from the ulamas’ bench, and said:

— ‘Prince of the Believers, did you not spare one of them yestereve?’

The sound of his voice was not unknown to the Caliph, who replied:

— ‘True; but I pardoned him on condition that the bread would be sold at ten ocques per gold sequin.

— ‘Remember,’ said the old man, ‘that the unfortunate bakers pay ten gold sequins per ardeb (about 280 kilos) of flour. Rather punish those who sell it to them at that price.’

— ‘And who are they?’

— ‘The moultezim (tax-collectors), cachefs, mouchirs, and the ulama themselves, who store sacks of flour in their houses.’

A shudder ran through the members of the council, and their assistants, who were the leading inhabitants of Cairo.

The Caliph leant his head on his hands and thought for a few moments. Argevan, irritated, wished to respond to what the old ulama had said, but the thunderous voice of Hakim resounded amidst the assembly.

— ‘Tonight,’ he said, ‘at the time of prayer, I will leave my palace of Roda, I will cross this arm of the Nile in my cange, and, on the shore, the chief of the guard will await me, with the executioner beside him; I will follow the left bank of the Calish (the canal), I will enter Cairo by the Bab el-Talha gate, to visit the mosque of Rashida (in Fustat). At each house in which I find a moultezim, cachef or ulema, I will ask if they have any sacks of grains stored away, and, in any house where all has been sold, I will have the owner hanged or beheaded.’

The vizier Argevan did not dare to raise his voice in council after these words of the Caliph; but, seeing him about to return to his apartments, he hastened to follow his steps, and said to him:

— ‘You will not do so, my lord!’

— ‘Away from here,’ cried Hakim, angrily. ‘Do you remember that when I was a child you used to jokingly call me your little lizard? Well, now the lizard has become a dragon.’

’

Chapter 4: The Moristan (The Asylum)

In th evening, when the hour of prayer arrived, Hakim entered the city via the soldiers’ quarters, followed only by the head of the guards, and the executioner: he noticed that all the streets were illuminated as he passed. The common people held candles in their hands to light the prince’s way, and the majority had grouped themselves in front of the houses of doctors, cachefs, notaries and other personages, the eminent persons whom the order had indicated. Everywhere, the Caliph entered and found a great heap of grain; which he, immediately, ordered to be distributed to the crowd, while recording the name of the owner.

— ‘According to my promise,’ he said to them, ‘your head is safe; but learn henceforth not to hoard grain at home, thereby living in abundance amidst the general misery, or reselling it for its weight in gold and amassing, in a few days, the entire public wealth.’

After visiting various houses in this way, he sent officers to the others, and went to the mosque of Rashida to pray himself, for it was a Friday; but, on entering, his astonishment was great to find the pulpit occupied and to be greeted with these words:

— ‘Let the name of Hakim be glorified on earth as it is in heaven! Eternal praise to the living God!’

However enthusiastic the people were about what the Caliph had just done, this unexpected prayer must have outraged the faithful; many approached the pulpit to denounce the blasphemer; but the latter descended with majesty, forcing his assailants to retreat at each step, and traversing the astonished crowd, who cried out on seeing him more closely:

— ‘He is blind! The Hand of God is upon him.’

Hakim had recognised the old man from Rumaila Square, and, as, when awaking, an unexpected connection sometimes unites material fact with the events of a passing dream, he felt, as if by a flash of lightning, the dual realities of his life and his ecstasies combine. However, his mind still struggled against this new impression, so that, without halting any longer in the mosque, he remounted his horse and took the road to his palace.

He summoned the vizier Argevan, who could not, however, be found. As it was time to visit Mokattam and consult the stars, the Caliph, once there, ascended the observatory’s tower, and climbed to the topmost floor whose pierced dome delineated the twelve houses of the stars. Saturn, Hakim’s planet, was pale and leaden, while Mars, which gave its name to the city of Cairo (Caher, the Victorious), blazed with that blood-stained brilliance which announces war and danger. Hakim descended to the first floor of the tower, where stood a cabalistic table established by his grandfather Moezzeldin. In the centre of a circle around which were written in the Chaldean language the names of all the countries of the earth, was the bronze statue of a horseman armed with a lance held upright; when an enemy people marched against Egypt, the horseman lowered his lance, and turned towards the country from which the attack would come. Hakim saw that the horseman had turned towards Arabia.

— ‘That race of Abassids, once more!’ he cried, ‘Those degenerate sons of Umar, whom we crushed in their capital of Baghdad! But what do these infidels matter to me now, I grasp the thunderbolt in my hand!’

On further reflection, however, he felt that he was a mere man as before; his hallucinations no longer endowed him with his previous confidence in possessing superhuman strength to add to his claim of being a god.

— ‘Come,’ he said to himself, ‘let me consult the source of ecstasy.’

And he again intoxicated himself, by means of that marvellous green paste which perhaps is identical with that substance the Greeks called ‘ambrosia’, the food of the immortals.

The faithful Yousuf was already present, and gazing dreamily at the dull, flat waters of the Nile, which had receded to a point which always announced the advent of drought and famine.

— ‘Brother,’ said Hakim, ‘is it love that you dream of? Tell me who your mistress is, and, on my oath, you shall win her.’

— ‘I know not, alas!’ said Yousouf. ‘Since the breath of the khamsin renders the nights stifling, I no longer meet her golden cange on the Nile. Would I dare ask who she is, even if I saw her again? I sometimes believe it was all only an illusion engendered by this perfidious drug, which perhaps assails my reason... so much so that I can no longer distinguish dream from reality.’

— ‘You believe so?’ said Hakim, anxiously.

Then, after a moment’s hesitation, he said to his companion:

— ‘What matter? Let us forget this life, for an hour or two.’

Once plunged in the intoxication of hashish, it happened, strangely enough, that the two friends entered into a certain communion of ideas and impressions. Yousouf imagined that his companion, leaping towards the heavens and stamping with his foot the ground unworthy of his glory, held out his hand to him and drew him into space, towards circling stars and vague swirls whitened with the seeds of stars; soon Saturn, pale, but crowned with its luminous rings, grew larger and drew nearer, surrounded by its seven moons in swift rotation, and from then on who could say what happened on their arrival in that divine homeland of their dreams? Human language can only express sensations in conformity with our nature; moreover, when the two friends conversed in this divine dream, the names they addressed each other by were no longer names of this Earth.

In the midst of this ecstasy, which rendered their bodies mere inert masses, Hakim suddenly twisted and cried out:

— ‘Eblis! Eblis! (the leader of the demons, according to Islamic teaching)’

At that very moment, a part of zebecks (irregulars) broke down the door of the okel, at their head Argevan, the vizier, who had the room surrounded, and ordered that all these infidels, violators of the Caliph’s order forbidding the use of hashish and fermented drinks, be seized.

— ‘Demon!’ cried the Caliph, regaining his senses, and collecting himself, ‘I have had you sought for your head! I know that it was you who caused the dearth of grain, distributing to your creatures the reserve of the State granaries! On your knees before the Prince of Believers! Begin by answering, for you will end by dying.’

Argevan frowned, and his dark eyes shone with a cold gaze.

— ‘To Moristan (the asylum), with this madman who thinks he’s the Caliph!’ he said disdainfully to the guards.

As for Yousouf, he had already run to his cange, foreseeing that he would not be able to defend his friend.

The Moristan, which today adjoins the Qualawun mosque, was then a vast prison, only part of which was devoted to the mad. The respect Orientals hold for the state of lunacy, does not extend to leaving at liberty those who could be harmful. Hakim, on waking the next day in a dark cell, soon understood that he had nothing to gain by flying into a rage, or calling himself Caliph while dressed like the fellahin. Besides, there were already five caliphs in the establishment, and a number of divinities! This last title was therefore no more advantageous than the former. Hakim was convinced, moreover, by his thousand efforts made during the night to break his chain, that his divinity, imprisoned in a weak body, had left him, like the Buddhas of India, and other incarnations of the Supreme Being, when abandoned to human malice and the material laws of force. He remembered, too, that the situation he found himself in was not new to him.

— ‘Let me seek, above all,’ he said, ‘to avoid being whipped.’

This was difficult, since it was the means generally employed at that time against incontinence of mind. When the visit of the hakem (doctor) arrived, he was accompanied by another doctor who seemed to be a foreigner. Hakim’s prudence was such that he showed no surprise at this visit, and limited himself to replying that an excess of hashish had been the cause of a temporary confusion in him, and that he now felt as usual. The doctor consulted his companion and spoke to him with great deference. The latter shook his head and said that often the insane had lucid moments, and achieved their liberty by such cunning claims. However, he saw no difficulty in granting him the freedom to walk about the courtyards.

— ‘Are you also a doctor?’ said the Caliph to the foreigner.

— ‘This is the Prince of Science, cried the asylum doctor; the great Ibn-Sina (Avicenna), who, having recently arrived from Syria, deigns to visit Moristan.’

The illustrious name of Ibn-Sina, the learned doctor, the venerated master of the health and life of humankind — who was also considered by the masses to be a magician capable of the greatest prodigies — made a lively impression on the mind of the Caliph. His prudence deserted him; he cried out:

— ‘O you who see me here, as Aïssé (Jesus) was, abandoned to this form and, in my human impotence, to the agents of hell, doubly misunderstood as Caliph and as God, is it not fitting that I be released from this unworthy situation as soon as possible? If you support me, then make that known; if you do not believe my words, curses be upon you!’

Avicenna would not answer; but turned to the physician, shaking his head, and said:

— ‘You see... already reason has abandoned him!’

And he added:

— ‘Fortunately, these visions harm no one. I have always said that the hemp from which hashish paste is derived was the very herb that, according to Hippocrates, sent wild creatures into a kind of frenzy and made them throw themselves into the sea. Hashish was already known in the time of Solomon: you can read the word hashishot in the Song of Songs (not so, but see Canticle VIII, 2), where the intoxicating qualities of this preparation....’

The rest of these words were lost to Hakim because the two doctors were moving away, and passing to another courtyard. He remained alone, abandoned to the most conflicting impressions, doubting that he was a god, sometimes even doubting that he was the Caliph, with great difficulty gathering together the scattered fragments of his thoughts. Taking advantage of the relative freedom left him, he approached the unfortunates scattered here and there in strange attitudes, and, listening to their songs and speeches, he registered the various ideas which had gained his attention.

One of these madmen had managed, by collecting various debris, to compose a sort of gleaming tiara out of pieces of glass, and to drape, over his shoulders, rags covered with bright embroidery which he had adorned with scraps of tinsel.

‘I am, he said, the Kemal Zeman (the Perfection of this Age), and I tell you that the hour is here.’

— ‘You lie,’ said another. ‘You are not the true god; you belong to the race of divs (demons, in Zoroastrian teachings) and seek to deceive us.’

— ‘Who do you think I am?’ said the first.

— ‘You are none other than Tahmuras (see the Persian poet Ferdowsi’s work, the ‘Shahnameh’), the last king of the rebellious genies! Do you not remember who defeated you on the island of Serendib (Shri Lanka, where the pre-Adamites dwelt according to legend), and who was none other than Adam, that is to say, myself? Your spear and shield are still suspended as trophies above my tomb.’

— ‘His tomb!’ cried the other, bursting into laughter, ‘No one has ever been able to find it. I counsel him to tell us where it lies.’

— ‘I have the right to speak of a tomb, having already lived six times among men, and died six times also, as I must; magnificent sepulchres have been built for me; but it is yours that would be difficult to discover, since you other divinities only inhabit dead bodies!’

The general hostility which followed these words was directed at the unfortunate emperor of the divs, who rose up furiously and whose crown the pretended Adam knocked off with the back of his hand. The other madman then rushed upon him, while the fight between the two enemies would have lasted five thousand years (according to their account), had not one of the overseers separated them with blows from a bull’s pizzle, distributed impartially, however.

One may wonder what interest Hakim took in this mad talk, to which he listened with marked attention, and which he even provoked with a few words. Sole master of his reason in the midst of these mutually defective intelligences, he silently plunged back into a world of memories. By a singular effect, which perhaps resulted from his austere attitude, the madmen seemed to respect him, and none of them dared raise their eyes to his face; however, something led them to group themselves around him, like those plants which, in the waning hours of the night, turn towards the as yet absent light.

If mortals cannot conceive for themselves what passes in the soul of a man who suddenly feels himself a prophet, or of a mortal who feels himself a god, fable and history have at least allowed them to recognise the doubts and anxieties that inevitably arise in such ‘divine’ natures, at that uncertain moment when their minds are freed from the temporary bonds of incarnation. Hakim, at times, doubted himself, as the Son of Man did on the Mount of Olives, and what especially struck his dazed thoughts was the idea that his divinity had first been revealed amidst the ecstasies of hashish.

— ‘There exists, then,’ he said to himself, ‘something stronger than He who is above all, and a plant of the fields it is that creates such glories? True, a common serpent proved that it was stronger than Solomon, when it pierced, and broke in half, the staff on which that Prince of Jinns leant (see the ‘Koran, 34:14, Sura Saba’); but what is Solomon compared to me, if I am truly Albar (the Eternal Guardian)?

Chapter 5: The Burning of Cairo

By a strange and derisory act of fate, the idea of which only an evil spirit could conceive, it happened that Moristan received a visit, one day, from the Sultana Setalmulc, who appeared, according to the custom of royal personages, to bring help and consolation to the prisoners. After having visited the part of the building devoted to criminals, she also wanted to see the asylum for the insane. The Sultana was veiled; but Hakim recognised her by her voice, and could not restrain his fury on seeing the minister Argevan at her side, who, smiling and calm, did her the honours of the place.

— ‘Here,’ Argevan said, ‘are various wretches whose thoughts are abandoned to a thousand extravagant inventions. One calls himself Prince of Jinns; a second claims to be the original Adam; but the loftiest in his ambitions is the one you see there, whose resemblance to the Caliph, your brother, is striking.’

— ‘It is extraordinary indeed,’ said Setalmulc.

— ‘Well,’ replied Argevan, ‘the resemblance alone was the cause of his misfortune. By dint of hearing himself told that he was the very image of the Caliph, he imagined himself to be the Caliph, and, not content with this idea, he claimed that he was God. He is simply a miserable fellow who has ruined his mind as so many others have done through the abuse of intoxicating substances.... It would be curious to see what he would say in the presence of the Caliph himself....’

— ‘Wretch!’ cried Hakim, ‘Have you not created a phantom that looks like me, and usurps my place!’

He was suddenly silent, thinking that prudence was deserting him, and that perhaps he was about to deliver his life over to fresh danger; fortunately, the noise made by the other madmen prevented his words being heard. All those unfortunates heaped imprecations upon Argevan, and the king of the divs especially challenged him forcefully.

‘Rest assured’ he called to him. ‘Just wait till I am dead; and we’ll meet again elsewhere.’

Argevan shrugged and exited with the Sultana.

Hakim had not even tried to invoke his memories of the latter. On reflection, he saw the plot had been too well woven to hope to unravel it with a single effort. Either he had been deliberately suppressed in favour of some impostor, or his sister and his minister had combined to deal him a lesson in wisdom by having him spend awhile at Moristan. Perhaps they wished to take advantage later of the notoriety that would accompany his situation to seize power, and keep him under guard. There was doubtless something in that: what caused him to think so was that the Sultana, on leaving the Moristan, promised the imam of the mosque to devote a considerable sum to enlarging and rebuilding the premises for the insane, in magnificent style — such that, she said, their dwelling would seem worthy of a Caliph.

Hakim, after the departure of his sister and his minister, said only:

— ‘It had to be thus!’

And he resumed his way of life, not ceasing to exhibit the gentleness and patience he had shown till then. Only, he conversed at length with those of his companions in misfortune who had lucid moments, and also with the inhabitants of the other part of the Moristan who often came to the gates which separated the courtyards, to amuse themselves regarding the extravagant behaviour of their neighbours. Hakim welcomed them with such words, that these unfortunates crowded there for hours on end, gazing at him as one inspired (majzub). Is it not a strange thing that the divine word always finds its first followers among the wretched? Thus, a thousand years previously, the Messiah found his audience composed mainly of people of ill-repute, tax-collectors, and publicans.

The Caliph, once confidently established in their eyes, summoned them one after the other, made them relate their life, the circumstances of their faults or their crimes, and searched, deeply, for the primary motive that had led to their troubles: ignorance and misery was what he found at the root of everything. These men also revealed to him the secrets of their world, the ploys exercised by the usurers, monopolists, lawyers, heads of trading-houses, tax-collectors, and wealthiest merchants of Cairo, all supporting each other, welcoming each other, multiplying their power and influence by family alliances; all corrupting, and corrupted; increasing or lowering, at will, the tariffs of trade; masters of famine and abundance, of riot and war, oppressing in an unbridled manner a populace prey to their lack of the essentials for life. Such had proved the result of the administration led by Argevan the vizier, during Hakim’s lengthy minority.

Moreover, sinister rumours were circulating in the prison; the guards themselves showed no fear in spreading them: it was said that a foreign army was approaching the city and was already encamped in the plain of Giza, that acts of treason would yield unresisting Cairo to this force, and that the lords, ulama and merchants, fearing the results of a siege as regards their wealth, were preparing to surrender the gates and had seduced the military leaders of the citadel. It was anticipated that, the very next day, the enemy general would make his entry into the city by the gate of Bab el-Hadid (the Iron Gate). From that moment, the line of the Fatimids would be dispossessed of the throne; the Abbasid caliphs would reign henceforth in Cairo, as in Baghdad, and public prayers would be offered in their name.

— ‘This is what Argevan has prepared for me!’ said the Caliph to himself; ‘this is what my father’s observatory revealed to me, when Pharoüis (Saturn) gleamed palely in the sky! But the moment has come to see what my words can achieve, and whether I will let myself be conquered as the Nazarene once was.’

Evening was approaching; the captives were gathered in the courtyard for the customary prayers. Hakim spoke, addressing himself at once to this dual population of madmen and evildoers separated by a barred gate; he told them who he was, and what he wanted from them, with such authority and such assurance that no one dared to doubt. In an instant, the labour of a hundred arms shattered the internal barriers, and the guards, struck with fear, yielded control of the doors leading to the mosque. The Caliph soon entered, carried on the shoulders of those unfortunates, whom his voice filled with enthusiasm and confidence.

— ‘He is the Caliph! The true Prince of Believers!’ cried the criminals.

— ‘It is Allah, who comes to judge the world!’ shouted the troop of madmen.

Two of the latter had taken their places, on Hakim’s right and left, shouting:

— ‘Come all to the judgement, dealt by our lord Hakim!’

The believers gathered in the mosque, knew not why their prayers were disturbed thus; but anxiety caused by the approach of their enemies led all to extraordinary action. Some fled, spreading alarm in the streets; others cried:

— ‘Today is the Day of Judgment!’

And this thought brought joy to the poorest and most oppressed, who cried:

— ‘At last, Lord! At last, cometh your day!’

When Hakim appeared on the steps of the mosque, a superhuman radiance wreathed his face, and his hair, which he always wore long and flowing contrary to Muslim custom, spread long coils over the purple mantle with which his companions had covered his shoulders. The Jews and Christians, always numerous in Soukarieh street which contained the bazaars, prostrated themselves, saying:

— ‘Is he the true Messiah, or is this the Antichrist announced by the Scriptures to appear a thousand years after Jesus!’

Some also recognised in him their sovereign; but could not explain why he was there in the midst of the city, while the general rumour was that, at that very hour, he was marching at the head of his troops against their enemies encamped in the plain that surrounded the pyramids.

— ‘O you, my people!’ said Hakim to the unfortunates who surrounded him, ‘you, my true sons, it is not my day, it is yours that is here. We have arrived at the time of renewal, which arises whenever the word of heaven has lost its power over souls, whenever virtue has become a crime, when wisdom has turned to folly, and glory is shamed; all combining, thus, against justice and truth. Never has the voice from on high failed to illuminate minds, like lightning before the thunder; that is why it has been said in turn: “Woe to Enochia, city of the children of Cain, city of impurities and tyranny! Woe to you, Gomorrah! Woe to you, Nineveh and Babylon! And woe to you, Jerusalem!” The voice, which never tires, thus resounds from age to age, and always, between the threat and the punishment, time is granted for repentance. However, that time is growing shorter by the day; when the storm approaches, the fire follows the lightning more closely! Let us show that henceforth the word is armed, and that on earth the reign announced by the prophets will finally be established! Yours, my children, shall be this city enriched by fraud, usury, injustice and rapine; yours shall be the plundered treasure, the stolen riches. Deal justice on that luxury which deceives, those false virtues, those titles acquired at the price of gold, those convoluted betrayals which, under the pretext of peace, have sold you to the enemy. Set fire, set fire, everywhere, to this city which my grandfather Moezzeldin founded under the auspices of victory (qahirah), yet which has become a monument to your cowardice!’

Was it as a sovereign, was it as a god, that the Caliph thus addressed the crowd? Certainly, he displayed within that supreme reason which is above common justice, otherwise the anger he had unleashed would have struck at random as brigands strike. In a few moments, flames had devoured the cedar-roofed bazaars and the palaces with their sculpted terraces and frail columns; the richest dwellings in Cairo revealed their devastated interiors to the people. A dreadful night, when sovereign power took on the appearance of rebellion, when the vengeance of heaven used the weapons of hell!

The fire, and the sacking of the city, lasted three days; the inhabitants of the richest districts had taken up arms to defend themselves, and numbers of the Greek soldiers and the ketamis, barbarian troops led by Argevan, fought against the prisoners and the populace carrying out Hakim’s orders. Argevan spread the rumour that Hakim was an impostor, that the true caliph was with the army in the plain of Giza, so that a terrible combat, by the light of the flames, took place in the great squares and the gardens. Hakim had retired to the heights of Qarafa, and in the open air held his bloody tribunal where, according to tradition, he appeared as if assisted by angels, having beside him Adam and Solomon, the one a witness for men, the other for the Jinns. All those hated by the masses were brought there, and their judgment took place in in an instant; heads fell, to the acclamations of the crowd; Several thousand perished during those three days. The melee in the centre of the city was no less deadly; Argevan was finally struck between the shoulders by a lance wielded by a man named Reidan, who brought his head to the feet of the Caliph; from that moment, all resistance ceased. It is said that at the very moment when the vizier fell with a terrible cry, the guests of Moristan, gifted with that second sight peculiar to the insane, cried out that they saw in the air Iblis (Satan), who, having emerged from the mortal remains of Argevan, was summoning to him and rallying in the air the demons incarnated until then in the bodies of his partisans. The combat begun on Earth continued in the heavens; the phalanxes of the eternal enemies gathered once more, and struggled with the forces of the elements. It is on this subject that an Arabian poet once said:

— ‘Egypt! Egypt! You know them, these dark struggles of good and evil spirits, when Typhon with stifling breath smothers the air and the light; when the plague decimates your toiling people; when the Nile flood diminishes; when dense clouds of locusts devour, in a day, all the verdure of the fields.

It is not enough, then, for Hell to act through those fearsome scourges; it also populates the Earth with cruel and greedy souls, who, beneath a human form, hide the perverse natures of jackals and serpents!’

However, when the fourth day came, the city being half-destroyed, the sharifs gathered in the mosques, raising their Korans in the air and crying:

— ‘O Hakim! O Allah!’

But their hearts were not in accord with their prayer. The old man who had already acknowledged Hakim’s divine nature, presented himself before the prince, and said to him:

— ‘Lord, enough; halt the destruction in the name of your grandfather Moezzeldin.’

Hakim wished to question this strange character who only appeared in dark hours; but the old man had already disappeared into the melee of attendants.

Hakim, on his usual mount, a grey donkey, began to roam the city, uttering words of reconciliation and clemency. From that time, he reformed the severe edicts pronounced against the Christians and the Jews, and exempted the former from bearing a heavy wooden cross on their shoulder, the latter from bearing a yoke on their neck. Through equal tolerance towards all beliefs, he sought to lead his people to accept, little by little, a new doctrine. Places for discussion were established, notably in a building which was called the house of wisdom, and various doctors of religion began to publicly support Hakim’s divinity. However, the human spirit is so resistant to beliefs which time has not consecrated, that only thirty or so were registered among the faithful thousand inhabitants of Cairo. There was a dissenter named Almoschadiar who said to the followers of Hakim:

— ‘He whom you invoke, in place of God, could neither create a fly, nor prevent it troubling him.’

The Caliph, informed of his words, granted him a hundred pieces of gold, as proof that he did not wish to force belief on the people. Others said:

— ‘There were several in the family of the Fatimids affected by this illusion. Thus, Hakim’s grandfather, Moezzeldin, concealed himself for several days, then claimed he had been snatched up to heaven; later, he withdrew to a cell, and it was said that he disappeared from the Earth without dying like other men.’

Hakim hearkened to these words, which plunged him into deep meditation.

Chapter 6: The Two Caliphs

The Caliph returned to his palace on the banks of the Nile, and resumed his previous way of life, recognised by all and free, now, of his enemies. For some time, things continued on their usual course. One day, he visited his sister Setalmulc and told her to prepare for their marriage, which he wished performed secretly, for fear of arousing public indignation, the people not yet being sufficiently convinced of his divinity as not to be shocked by such a violation of established law. The ceremony was to involve only eunuchs and slaves as witnesses, and would be performed in the palace mosque; as for the festivities, the obligatory consequence of their union, the inhabitants of Cairo, accustomed to seeing the screens of the seraglio starred with lanterns and to hearing the sounds of music carried by the night breeze from the far side of the river, would not note them specifically, or be surprised by them in any significant way. Later, Hakim, when the time had come and minds were favourably disposed, reserved the right to proclaim aloud their mystical religious wedding.

When evening came, the Caliph, having disguised himself according to his custom, visited the observatory at Mokattam, so as to consult the stars. The heavens granted Hakim scant reassurance: sinister planetary conjunctions, dimmed constellations, foreshadowed the peril of imminent death. Possessing, as a god, the consciousness of his own eternal being, he was little alarmed by such celestial threats, which concerned only his perishable envelope. However, he felt his heart filled with poignant sadness, and, renouncing his usual perambulation, he returned to the palace in the early hours of the night.

Crossing the river by cange, he saw with surprise that the palace gardens were illuminated as if for a festival: he entered. Lanterns hung from the trees like fruits wrought of rubies, sapphires and emeralds; scented fountains launched their silver jets amidst the foliage; water ran in the marble gutters, and from the alabaster pavement, about the openwork kiosks, bluish smoke from most precious perfumes, was exhaled in wispy spirals and mingled its aroma with that of the flowers. Harmonious murmurs of hidden music alternated with the songs of the birds, who, deceived by these gleams, believed they were greeting the dawn, and, in the flamboyant background, in the midst of a blaze of light, the facade of the palace glowed, the lines of its architecture outlined by tongues of fire.

Hakim’s astonishment was extreme; he asked himself:

— ‘Who dares to celebrate there, while I am away? What unknown guest’s arrival is being celebrated at this hour? These gardens should be deserted and silent. Moreover, I have taken no hashish, and am no longer the plaything of the hallucinations it induces.’

He drew nearer. Dancers, dressed in dazzling costumes, undulated like serpents, upon Persian carpets surrounded by lamps, such that none of their movements and poses were lost. It seemed as if they failed to see the Caliph. At the palace gate, he encountered a whole host of pages and slaves bearing iced fruits and conserves in golden basins, and sorbets in silver ewers. Although he walked alongside them, jostling and being jostled by them, no one paid him the slightest attention. This singular occurrence filled him with secret disquiet. He felt himself passing among them like a shadow, an invisible spirit, and he continued to advance from room to room, threading the groups as if he on his finger he wore the magic ring possessed by Gyges (see Plato’s ‘Republic 2:359a–2:360d’).

When he reached the threshold of the last room, he was dazzled by a torrent of light: thousands of candles, set in silver candelabra, gleamed like bouquets of fire, mingling their bright halos. The instruments of the crowd of musicians concealed in the galleries thundered in vigorous triumph. The Caliph approached unsteadily, and took shelter behind the folds of an enormous brocade curtain. He now perceived at the rear of the salon, seated beside Setalmulc on a divan, a man dripping with jewels, his clothes studded with diamonds which sparkled amidst a swarm of scintillations and prismatic rays. One would have said that the treasures of Harun-al-Rashid had been exhausted to clothe this new Caliph.

One can imagine Hakim’s stupor on viewing this unheard-of spectacle: he reached for his dagger in his belt to assail the usurper; but an irresistible force constrained him. This vision seemed to him a celestial warning, and his confusion increased still further when he recognised, or thought he recognised, his own features in those of the man seated beside his sister. He believed that it was his ferouer (the Zoroastrian supernatural spirit within the body, that quits it, and pleads for it after death) or double, and, for Orientals, seeing one’s own shade is a direst omen. The phantom forces the body to follow it within a day.

Here the apparition was all the more threatening, as the ferouer had accomplished in advance the intention conceived by Hakim. Did not the action of this phantasmic Caliph, in wedding Setalmulc, whom the true Caliph had resolved to marry himself, contain some enigmatic meaning, some mysterious and symbolic terror? Was some jealous divinity, seeking to usurp heaven by wresting Setalmulc away from her brother, by separating the cosmogonic pair, hitherto blessed by providence? Was the race of divs attempting through this means, to prevent the affiliation of superior spirits and substitute its impious offspring? These thoughts crossed Hakim’s mind instantly: in his anger, he would have liked to rouse an earthquake, a flood, a rain of fire, or some other cataclysm; but he remembered that, bound to a form of earthly clay, he could only employ human measures.

Unable to manifest himself in a victorious manner, Hakim slowly withdrew and returned to the gate which opened on the Nile; a stone bench stood there; he seated himself and remained for some time lost in thought, seeking the meaning of the strange scene which had passed before him. At the end of a few minutes, the postern opened again, and, amidst the darkness, Hakim saw two vague shadows emerge, one of which cast a darker shadow on the ground than the other. With the aid of those vague reflections of earth, sky, and water, which, in the East, never render the darkness completely opaque, he discerned that the first was an Arab youth, and the second a gigantic Ethiopian.

Having reached a point on the bank which projected into the river, the young man knelt down, the Ethiopian placed himself near him, and the flash of a damascene blade gleamed in the darkness like a bolt of lightning. However, to the great surprise of the Caliph, the former’s head did not fall, and the Ethiopian, having leaned towards the victim’s ear, seemed to murmur a few words after which the latter rose, calmly and quietly, without undue joy or haste, as if it had concerned some other and not himself. The Ethiopian returned his blade to its scabbard, and the young man approached the river’s edge, close to Hakim, doubtless to cross once more in the boat which had brought him there. He found himself face to face with the Caliph, who feigned to wake, and said:

— ‘Peace be with you, Yousouf! Why are you here?’

— ‘Peace be to you, also!’ replied Yousouf, who still saw in his friend only a companion in adventure and was not surprised to have found him sleeping on the river-bank, as the sons of the Nile do in the hot summer nights.

Yousouf made the Caliph climb aboard the cange, and they let the vessel float with the flow of the river, along the eastern shore. The dawn was already tinting the neighbouring plain with a reddish hue, and outlined the silhouette of the ruined remains of Heliopolis, at the desert’s edge. Hakim felt as if in a dream, and, examining the features of his companion, which the day increasingly revealed, more attentively, he found in him a certain resemblance to himself which he had never noticed until then, for he had always met him at night, or seen him amidst the intoxication of hashish. He could no longer doubt that this was the ferouer, his double, the apparition of the day before, perhaps the one who had been made to play the role of Caliph during his stay in the Moristan. This explanation naturally left him with a degree of astonishment.

— ‘We are as alike as twin brothers,’ he said to Yousouf. ‘Sometimes, to justify such a coincidence, it is enough to be born amongst the same people. Where were you born, friend?’

— ‘At the foot of the Atlas Mountains, at Ketama, in the Maghreb, among the Berbers and the Kabyle people. I did not know my father, who was called Dawas, and who was killed in battle shortly after my birth; my grandfather, very advanced in years, was one of the sheiks of that desert country.’

— ‘My ancestors are also from that land,’ said Hakim; perhaps we are descended from the same tribe.... But what matter? Our friendship needs no tie of blood to be lasting and sincere. Tell me why I have not seen you for several days.’

— ‘You may well ask!’ said Yousouf. ‘These days, or rather nights, for I devote the days to sleep, have passed like delightful dreams, full of wonders. Since Justice surprised us in the okel and parted us, I have again encountered, on the Nile, that charming vision whose reality I can no longer doubt. Often, putting her hand over my eyes, to prevent me from noting the way, she has led me into magnificent gardens, and rooms of dazzling splendour, where the architect’s genius has outdone those fantastic constructions that the fantasies of hashish build among the clouds. A strange fate is mine! My waking hours are fuller of dreams than even my sleep. In that palace, no one seemed surprised by my presence, and, when I passed by, all heads bowed respectfully before me. Then that unknown girl made me sit at her feet, intoxicating me with her words and gaze. Each time she raised her eyelids fringed with long lashes, it seemed to me that a fresh paradise opened to me. The inflections of her harmonious voice plunged me into ineffable ecstasies. My soul, caressed by that enchanting melody, melted with delight. Slaves brought exquisite delicacies, preserves of roses, sorbets of snow, that she barely touched with her lips; for a creature so celestial and so perfect must surely live only on perfume, dew, and rays of light. Once, raising by the power of some magic utterance a paving slab closed with mysterious seals, she made me descend to the vaults below where her treasures are kept, and detailed their riches to me, saying they would be mine if I showed but love and courage enough. I saw there more wonders than are contained in the legendary mountain of Kaf, where the treasures of the Jinns are hidden: elephants made of rock-crystal; trees of gold on which birds wrought of precious stones beat their wings and sing; peacocks opening their tails like wheels starred with diamond suns; masses of camphor cut into slices, enclosed in filigree nets; tents of velvet and brocade with poles of solid silver; and, in cisterns, heaped like grain in a silo, piles of gold and silver coins, garnets and pearls.’

Hakim, who had listened attentively to this description, addressed his friend Yousouf:

— ‘Do you not know, brother, that what you viewed there were the treasures of Harun-al-Rashid taken by the Fatimids, and which can only be found in the Caliph’s palace?’

— ‘I know it now; but already, from the beauty and wealth of the stranger, I felt that she must be of the highest rank. Who knows, perhaps a relative of the grand vizier, the wife or daughter of some powerful lord. But what need did I have to learn her name? She loved me; was that not enough? Yesterday, when I arrived at the usual place of rendezvous, her slaves bathed me, perfumed me, and dressed me in magnificent clothes, more splendid that such as the Caliph Hakim wears. The garden was illuminated, and there was an air of celebration as if a wedding were in preparation. The woman I loved allowed me to take my place beside her on a divan, and let her hand meet mine, while her gaze was full of languor and voluptuousness. Suddenly she turned pale as if a fatal apparition, a dark vision, perceptible only to her, had arisen to eclipse the celebration. She dismissed the slaves with a gesture, and said to me in an agonised voice: “I am lost! Behind the door-hanging, I see shining azure unforgiving eyes. Do you love me enough to die for me?” I assured her of my boundless devotion. “It is necessary,” she continued, “that your existence be erased, that your passage on earth leave no trace, that you are annihilated and your body divided into impalpable particles, such that not an atom of you may be found; otherwise, the one to whom I am subject would invent torments for me to terrify the wickedness of the divs, and make the damned shudder with terror in the depths of Hell. Follow this Ethiopian; he will dispose of your life as is fitting.” Outside the postern, the Ethiopian made me kneel, as if he were about to sever my head; he swung the blade two or three times; then, seeing my firmness, he told me that it was all merely a game, a trial, and that the princess had wished to know if I was really as brave and devoted as I claimed. “Take care to find yourself tomorrow in Cairo towards evening, at the Fountain of Lovers, and a new rendezvous will be assigned,” he added, before returning to the garden.’