Gérard de Nerval

Travels in the Near East (Voyage en Orient, 1843)

Part X: Druze and Maronites (Druses et Maronites) – A Prince of Lebanon, and The Prisoner

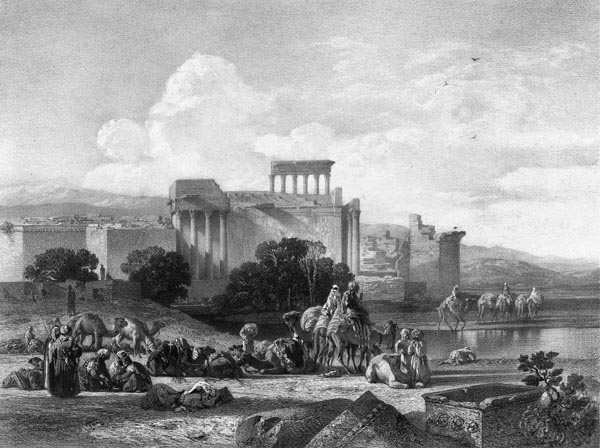

Caravan in front of the temple ruins of Baalbek, 1850, George Antoine Prosper Marilhat

Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- A Prince of Lebanon.

- Chapter 1: The Mountain.

- Chapter 2: A Mixed Village.

- Chapter 3: The Manor.

- Chapter 4: A Hunt.

- Chapter 5: Keserwan.

- Chapter 6: Conflict.

- The Prisoner.

- Chapter 1: Morning and Evening.

- Chapter 2: A visit to the French School.

- Chapter 3: The Akkal.

- Chapter 4: The Druze Sheikh.

A Prince of Lebanon

Chapter 1: The Mountain

I had accepted, eagerly, the invitation from the Lebanese prince or emir who had visited me, to spend a few days at his residence, located a short distance from Aintoura, in Keserwan. As we were to leave the next morning, I had only time to return to Battista’s hotel, where it was a question of agreeing the rental cost of the horse I had been promised.

I was led to the stable, where I saw only large bony creatures, with strong legs, and narrow backs like those of fish... in truth, they scarcely belonged to the breed of Nedjdi horses, but I was told that they were the best for climbing the steep slopes of the mountains in safety. The more elegant Arabian steeds only shine on the sandy floor of the desert. I pointed to one at random, and was promised that it would be at my door the next day, at daybreak. I was offered as companion a young lad named Moussa (Moses), who spoke Italian well. I offered my heartfelt thanks to Signor Battista, who had taken charge of the negotiation, and with whom I promised to stay on my return.

Night had fallen, but night in Syria is only a bluish version of day; all were enjoying the cool air on the terraces, and the city, as I gazed at it from the outer slopes, took on a Babylonian air. The moonlight produced white silhouettes at various levels formed, from afar, by the houses, that by day were so tall and dark, and whose uniformity was only broken, here and there, by the crowns of cypresses and palm-trees.

As you leave the city, you see at first only deformed plants; aloes, cacti and nopals, displaying, like the gods of India, multiple heads crowned with serrated flowers, and raising quite formidable swords and darts as you pass; but, beyond their reign, you encounter the broken shade of white mulberry-trees, laurels and lemon-trees with shiny, metallic leaves. Luminous flies soar here and there, brightening the darkness of the groves. The ogives and arches of the tall, illuminated dwellings are outlined in the distance, and, from the depths of those severe-looking mansions, you sometimes hear the sound of guitars (ouds) accompanying most melodious voices.

At the corner of the path that turns and ascends to the house where I lived, there was a tavern established in the shade of an enormous tree. There the young people of the surrounding area gathered, and commonly remained, drinking and singing, until two in the morning. The guttural sound of their voices, the drawn-out melody of some nasal recitative, succeeded one another, night after night, to the detriment of any European ears that might be open to their surroundings; I will admit, however, that this primitive and biblical music is not without charm on occasion, for those who know how to rise above the prejudices of solfeggio.

When I returned, I found my Maronite host, with his entire family, waiting for me on the terrace adjoining my lodgings. These good people believe they are doing you honour in bringing all their relatives and friends to your house. It was necessary to have them served coffee, and for pipes to be distributed, which, however, the mistress and girls of the house took care of, at the tenant’s expense of course. A few mixed phrases of Italian, Greek, and Arabic maintained the conversation, though rather painfully. I did not dare say that, having not slept during the day, and having to leave at dawn the following day, I would have liked to seek my bed; but, after all, the sweetness of the night, the starry sky, the sea spreading at our feet its shades of nocturnal blue, whitened here and there by the reflections of the stars, allowed me to endure the tedium of their reception quite easily. These good people finally bade me farewell, since I had to leave before they would wake, and, in fact, I barely had time to secure three hours of sleep, ended by cockcrow.

When I awoke, I found young Moussa sitting before my door, at the edge of the terrace. The horse he had brought was standing at the bottom of the steps, one foot folded under its belly by means of a rope, which is the Arab way of restraining a horse. All I had to do was fit myself into one of those high saddles fashioned in the Turkish manner, which squeeze you like a vice and make falling almost impossible. Large copper stirrups, in the shape of coal shovels, are attached at such a height that one’s legs are bent in two; their sharp corners serve to prick the horse. The prince smiled a little at my embarrassment in adopting the pose of an Arab horseman, and gave me some advice. He was the young man, of frank and open countenance, whose greeting had first charmed me; His name was Abou-Miran, and he belonged to a branch of the Hobeika family, the most illustrious in Keserwan. Without being one of the richest, it had authority over a dozen villages comprising a district, and paid dues to the Pasha of Tripoli.

All being ready, we descended to the road which runs along the shore, and which, anywhere but in the East, would pass for a simple ravine. At the end of a few miles, I was shown the cave from which the famous dragon emerged which was about to devour the daughter of the king of Beirut when Saint George pierced it with his lance. The place is highly revered by the Greeks, and by the Turks themselves, who have built a small mosque on the very spot where the conflict took place.

All Syrian horses are trained to walk at an amble, which renders their trot very gentle. I admired their sureness of step on the loose stones, sharp pieces of granite, and smooth rock one encounters everywhere.... It was already broad daylight, when we left behind the fertile promontory of Beirut, which juts into the sea five miles or so, its heights crowned with umbrella-pines, its staircase of terraces cultivated as gardens; the immense valley between two mountain ranges extends as far as the eye can see in a double amphitheatre, whose violet hue is brightened, here and there, by chalk-white patches, indicating a host of villages, monasteries and fortresses. It is one of the most open panoramas in the world, one of those places where the soul expands, as if to match the extent of so vast a spectacle. At the bottom of the valley flows the Nahr Beirut, a river in summer, a torrent in winter, which runs to the gulf, and which we crossed in the shade of a Roman bridge’s arches.

The horses had water only up to their mid-legs: mounds covered with thick oleander bushes divided the flow, and shaded the natural bed of the river; two areas of sand, indicating the extreme flood-line, parted and highlighted this long ribbon of flowering verdure which filled the whole floor of the valley. Beyond, the first slopes of the mountain rise; sandstone greened by lichens and mosses, twisted carob trees, stunted oaks with dark green leaves, and aloes and nopals, lying in wait among the stones like armed dwarves threatening travellers as they pass by, but offering refuge to enormous green lizards that flee by the hundreds under the horses’ feet: this is what one encounters when climbing the lower slopes. However, long stretches of arid sand interrupt, here and there, the coating of wild vegetation. A little further away, these yellowish wastelands lend themselves to cultivation, displaying regular lines of olive trees.

We had soon reached the summit of the first plateau, which, from below, seemed to merge with the Sannine massif. Beyond, a valley opens, a fold lying parallel to that of the Nahr Beirut, and which must be crossed to reach the second crest, from which yet another may be discerned. One already perceived that the numerous villages, which from afar seemed to shelter on the black flanks of the mountain, on the contrary dominated and crowned chains of heights, separated by valleys and chasms; one could also see that these lines, furnished with forts and towers, would present a series of inaccessible ramparts to any army, if the inhabitants wished, as in the past, to unite, and fight for the common principle of independence. Unfortunately, too many have an interest in deriving advantage from their internal divisions.

We drew to a halt on the second plateau, where stands a Maronite church, built in the Byzantine style. Mass was being said, and we dismounted in front of the door, in order to listen awhile. The church was full of people, since it was a Sunday, and we could only find a place in the rear pews.

The clergy seemed dressed much like the Greeks; the costumes are quite beautiful, and the language used ancient Syriac, which the priests declaimed or sang in a nasal tone peculiar to themselves. The women were seated in a raised gallery, defended by a grating. In examining the ornamentation of the church, simple but freshly repaired, I saw, with a degree of pain, that the black double-headed eagle of Austria decorated each pillar, as a symbol of the protective role formerly occupied by France alone. It is only since our latest revolution that Austria and Sardinia have competed with us for influence in the minds and affairs of the Syrian Catholics.

A Mass in the morning can do one no harm, unless one enters the church in a sweat, and exposes oneself to the damp shade that shrouds the vaults and pillars; but this house of God was so clean and cheerful, the sound of its bells had summoned us with such a pretty and silvery timbre, and we stood so near the entrance, that we exited cheerfully, well-disposed to completing the rest of our journey. Our horsemen set off again at a gallop, calling out to each other with joyful cries; pretending to pursue one another, they threw before them, like javelins, their lances adorned with cords and tufts of silk, and then retrieved them, without pause, from the earth, or the trunks of the distant trees in which they had lodged.

This game of skill was of brief duration however, for the descent became difficult, and the horses’ feet scraped more timidly, at the sandstone, smooth or broken in sharp fragments. Until then, young Moussa had followed me on foot, according to the custom of the moukres (muleteers), though I had offered to take him up behind me; but I was beginning to envy his fate. Reading my thoughts, he offered to guide the horse, and I was able to cross the valley floor by navigating the thickets and stones. I took a moment’s rest on the other side, and admired the skill of our companions in traversing ravines that would be considered impassable in Europe.

Soon we were climbing in the shade of a pine forest, and the prince dismounted as I did. A quarter of an hour later, we found ourselves at the edge of a valley, less deep than the other, and forming a kind of verdant amphitheatre. Herds were grazing the grass around a small lake, and I noticed, there, some of those Syrian sheep whose tails, burdened by fat, weigh up to twenty pounds. We descended, to water the horses, at a fount covered with a vast stone arch, and of ancient construction, or so it seemed to me. Several women, gracefully draped, came to fill large vases, which they then planted on their heads; naturally they were not wearing the high headdresses of married women; they were young girls or servants.

Chapter 2: A Mixed Village

Advancing a few more paces beyond the fount, remaining in the shade of the pines, we found ourselves at the entrance to the village of Beit Mery, situated on a plateau, from which the view extends, on one side, towards the gulf, and, on the other, over a deep valley, beyond which new crests of mountains fade into a bluish mist. The contrast of this freshness and silent shade with the heat of the plains and beaches that we left a few hours ago, was a sensation only truly appreciated in such a climate. About twenty houses were scattered among the trees, and presented the picture more or less of one of our southern villages. We halted at the residence of the sheikh, who was absent, but whose wife served us curdled milk and fruit.

We had passed, on our left, a large house, whose collapsed roof and charred beams indicated a recent fire. The prince informed me that it was the Druze who had set fire to the building, while several Maronite families were gathered there for a wedding. Fortunately, the guests had been able to flee in time; but the most notable feature was that the culprits were inhabitants of the same locality. Beit Mery, as a mixed village, contains about a hundred and fifty Christians, and sixty Druze. The houses of the latter are separated from those of the former by barely two hundred yards. As a result of this hostility, a bloody fight had taken place, and the Pasha had hastened to intervene by establishing, between the two sections of the village, a small camp of Albanians, who lived at the expense of the rival populations.

We had just finished our meal when the sheikh returned to his house. After the initial pleasantries, he commenced a long conversation with the prince, in which he complained strongly of the Albanians’ presence and of the general disarmament which had been enforced in his district. It seemed to him that this measure should have been exercised only in regard to the Druze, who bore the sole responsibility for the nocturnal attacks and arson. From time to time, the two leaders lowered their voices, and, though I could not completely grasp the meaning of their discussion, I thought it proper to withdraw a little, on the pretext of taking a short walk.

As we walked, my guide informed me that the Maronite Christians of the province of El Gharb, in which we were, had previously attempted to expel the Druze, who were scattered among several villages, and that the latter had called to their aid their co-religionists of the Anti-Lebanon. Hence, one of those struggles which are so often renewed. The greater mass of Maronites inhabit the province of Keserwan, situated behind Jebail (Byblos) and Tripoli, while the largest population of Druze inhabit the provinces situated from Beirut to Acre. The sheikh of Beit Mery was doubtless complaining to the prince that, in the recent events of which I spoke, the people of Keserwan had not stirred; although they had not had time, the Turks having put a stop to the matter with an eagerness unusual on their part. That was because the quarrel had arisen at the time of paying the miri. ‘Pay first,’ the Turks had said, ‘then you can fight as much as you like.’ Was this not, indeed, the only way to collect taxes from people who ruin themselves, and slaughter each other, at the very instant of harvest?

At the end of the line of Christian houses, I stopped beneath a clump of trees, from which one could see the sea breaking, in silvery waves, on the distant shore. There is a view, from there, of the stepped mountain ridges we had crossed, the tenuous river courses that furrow the valleys, and the yellowish ribbon of the road built by Antoninus, which can be traced following the coast, a good road beside which one finds Roman inscriptions and Persian bas-reliefs among the rocks. I had seated myself in the shade, when a message arrived inviting me to take coffee at the home of the mudhir, or Turkish commander, who, I supposed, exercised temporary authority following the occupation of the village by the Albanians.

I was led to a house, newly decorated doubtless in honour of this official, with a beautiful Indian carpet covering the floor, a tapestried divan, and silk curtains. I had the irreverence to enter without removing my shoes, despite the remarks of the Turkish servants, which I failed to understand. The mudhir made a sign to them to be quiet, and indicated a place on the divan, without himself rising to his feet. He had coffee and pipes brought, and addressed a few polite words to me, interrupting himself from time to time to apply his seal to squares of paper passed to him by his secretary, seated near him on a stool.

The mudhir was young and seemingly full of pride. He began by questioning me, in bad Italian, with all the usual banalities, about the use of steam, Napoleon, and the imminent discovery of a method of achieving manned flight. After satisfying him on these points, I thought to ask him for a few details regarding the population thereabout. He seemed very reserved regarding the matter; however, he told me that a quarrel had arisen there, as in several other places, due to the fact that the Druze did not wish to pay their tribute into the hands of the Maronite sheikhs, who were responsible to the Pasha. The same position existed in reverse in the mixed villages of the Druze districts. I asked the mudhir if there was any difficulty in visiting the other areas of the village.

— ‘Go where you wish,’ he said; ‘all these people have kept the peace since we arrived. Previously, they fought for one side or the other, for the white cross, or the white hand, on equally red banners. Such are the emblems that distinguish the flags of the Maronites and the Druze from one another.’

I took leave of this Turk, and, as I knew that my companions would remain at Beit Mery during the heat of the day, I headed towards the Druze quarter, accompanied only by Moussa. The sun was at full strength; after walking for ten minutes, we came across the first two houses. In front of the one on the right was a terraced garden in which some children were playing. They ran to see us pass by, uttering loud cries which brought two women from the house. One of them wore a tantour, which indicated her status as a wife or widow; the other appeared younger, and had her head covered with a simple veil, with which she covered part of her face. However, one could distinguish their features, which appeared and vanished in turn as they moved, like the moon’s features among the clouds.

The rapid examination that I could make was completed by the features of the children, whose uncovered faces, perfectly formed, were similar to those of the two women. The youngest, seeing me halt, went back to the house and returned with a porous earthenware jug, the spout of which she tilted towards me between the large cactus heads that bordered the terrace. I approached to drink, though I was not thirsty, since I had just enjoyed the mudhir’s refreshments. The other woman, seeing that I had only taken a mouthful, said to me: Tourid leben? (Do you wish for milk?) I made a sign of refusal, but she had already turned towards the house. On hearing the word leben, I remembered that in German it means life. Lebanon takes its name from that same word leben, owing to the whiteness of the snow which covers its mountains, and which the Arabs, in the burning sands of the desert, dream of from afar; snow like milk — reviving life! The good woman hastened back, bearing a cup of foaming milk. I could scarcely refuse to drink of it, and was about to take some coins from my belt, when, at the mere movement of my hand, the pair made very energetic signs of refusal. I already knew that hospitality in Lebanon is greater even than that of Scottish custom: I did not insist.

As far as I could judge from the comparative appearance of these women and children, the features of the Druze population are somewhat related to those of the Persians. The hue which tinted, with amber, the faces of the little girls, was absent from the matt white features of the two half-veiled women, such that one might believe the habit of covering the face to be, among the Levantines, a question, above all, of coquetry. The invigorating air of the mountain, and their work habits, strongly colour the lips and cheeks. Turkish rouge is therefore useless to them: however, as with the latter, that dye shades their eyelids, and prolongs the arch of the eyebrows.

I walked further. The houses were all single-storied, and mostly built of adobe, the largest being of reddish stone, with flat roofs supported by interior arches, and exterior staircases ascending to the roof, and their entire furniture, as one could see through the barred windows or half-open doors, consisted of carved cedar panelling, mats, and sofas, the children and women animating the scene without being too surprised at the passage of a stranger, and addressing me in a kindly manner with the customary sal-kher (good day).

Having reached the end of the village where the Beit Mery plateau ends, I saw on the other side of the valley a monastery, to which Moussa wished to guide me; but fatigue was beginning to overcome me and the heat of the sun had become unbearable: I seated myself in the shade of a wall, against which I leaned with a sort of drowsiness, due to the lack of peace the previous night. An old man emerged from the house and invited me to go and rest in his house. I thanked him, fearing that it was already late and that my companions would be worried at my absence. Seeing that I refused all refreshment, he told me that I must not leave him without accepting something. Then he went to fetch some small apricots (meshmosh), which he handed to me; next he wished to accompany me to the end of the street. He seemed annoyed on learning from Moussa that I had lunched at the house of the Christian sheikh.

— ‘I am the true sheikh,’ he said, ‘and I hold the right of granting hospitality to strangers.’

Moussa then told me that the old man had indeed been the sheikh or lord of the village in the days of Emir Bashir II; but, as he had sided with the Egyptians, the Turkish authorities no longer recognised him as such, and the role had fallen to a Maronite.

Chapter 3: The Manor

We remounted our horses, at about three o’clock, and descended into the valley over the floor of which flows a small river. Following its course, which headed towards the sea, and then ascending among rocks and pines, crossing here and there fertile valleys planted with mulberry-trees, olive-trees and cotton-trees, between which wheat and barley had been sown, we finally found ourselves on the banks of the Nahr el-Kalb, that is to say the Dog River, the ancient Lycus, which spreads its little water between the reddish cliffs and the laurel bushes. This river, which, in the summer, is barely a stream, takes its source in the snowy peaks of the upper Lebanon, as do all the other watercourses which run parallel to this coast as far as Antakya, and which flow into the sea off Syria. The high terraces of the convent of Aintoura rose to our left, and the buildings seemed very near, although we were separated from them by deep valleys. Other Greek, Maronite, or European Lazarist monasteries appeared, dominating numerous villages, all this, which, in its features, may be readily compared to the physiognomy of the Apennines or the lower Alps, providing a prodigious contrast in its effect, when one recalls that one is in a Muslim country, a few miles from the desert landscape of Damascus, and the dusty ruins of Baalbek. What also makes this part of Lebanon like a little, free, industrious, and above all intelligent, version of a European country, is that the impression of overbearing heat which troubles the people of Asia-Minor ceases here. The sheikhs and other well-off inhabitants have, seasonal residences which, set higher or lower in the terraced valleys between the mountains, allow them to live amidst an eternal Spring.

The area we reached at sunset, already quite elevated, but protected by two chains of wooded peaks, seemed to me to possess a delightful temperature. There the prince’s estates began, as Moussa told me. We were thus nearing the end of our journey; however, it was only at nightfall, and after traversing a sycamore wood through which it was difficult to guide the horses, that we perceived a group of buildings dominating a hillock, around which wound a steep path. They had quite the appearance of a Gothic castle; a few lighted windows, narrow ogives, formed, moreover, the only external adornment of a square courtyard enclosed by high walls. However, after a low door with an equally low arch had been opened, we found ourselves in a larger courtyard surrounded by galleries supported on columns. Numerous valets, and African black slaves hurried to attend to the horses, and I was introduced to a low room or ghurfa, large in size, and adorned with divans, where we took our seats while waiting for supper. The prince, after having refreshments served for his companions and myself, blamed the lateness of hour for not allowing him to introduce me to his family, and entered that part of the house which, among the Lebanese Christians as among the Turks, is especially consecrated to women; he had drunk with us only a glass of golden wine at the moment when supper was brought.

The next day I awoke to the sound of the sais and the black slaves busy with tending the horses in the courtyard. There were also a host of mountain dwellers bringing provisions, and various Maronite monks in black hoods and blue robes, gazing on everything with a benevolent smile. The prince soon appeared and led me to a terraced garden sheltered on two sides by the castle walls, but with a view beyond over the valley where the deeply-entrenched Nahr el-Kalb flowed. In this small space banana-trees, dwarf-palms, lemon-trees, and other trees of the plain, were grown, which, on this high plateau, formed a rare and luxurious resource. I thought a little of the chatelaines whose barred windows probably looked out upon this little Eden; but there was no mention of them. The prince spoke to me at length about his family, the journeys his grandfather had made to Europe, and the honours he had obtained there. He spoke very good Italian, like most of the emirs and sheikhs of Lebanon, and seemed well-disposed towards making a journey to France someday.

At dinner time, that is to say towards noon, I was asked to ascend to a high gallery, opening on the courtyard, the rear of which formed a sort of alcove furnished with divans with a platform-floor; two highly adorned women were seated on a divan, their legs crossed in the Turkish manner, and a little girl who was beside them came, according to tradition, to kiss my hand, as we entered. I would willingly have paid this homage in my turn to the two ladies, if I had not thought that it was contrary to custom. I simply bowed, and took my seat with the prince at a marquetry table which supported a large tray loaded with food. At the moment when I was about to sit down, the little girl brought me a long silk napkin embroidered with silver-thread at both ends. The ladies continued, during the meal, to maintain their pose on the platform like idols. Only when the table was cleared, did we seat ourselves opposite them, and it was on the order of the eldest that hookahs were brought.

These folk were clad, over the waistcoat which clasped the chest, and the shintyan (loose trousers) with long pleats, in long robes of striped silk. A heavy belt, adorned with gilt, diamond, and ruby ornaments testified to a very general luxury common elsewhere in Syria, even among women of lesser rank. As for the cone-shaped headdress that the mistress of the house wore above her brow and which rendered her movements those of a swan, that was of chased silver-gilt with turquoise inlays; the braids of her hair, intermingled with clusters of sequins, streamed over her shoulders, according to the general fashion of the Levant. The legs of these ladies, folded on the divan, were bare of stockings; which, in these countries, is a common feature, and adds to beauty a means of seduction far removed from our own ideas. Women who scarcely walk about, who indulge several times a day in perfumed ablutions, whose shoes do not compress the toes, possess, as one can well imagine, feet as charming as their hands; henna dye, which reddens the nails, and ankle-rings, as rich as bracelets, complete the grace and charm of that portion of a woman’s figure which is sacrificed too readily, in our own country, to the glory of the shoemakers.

The princesses asked me many questions about Europe and told me about several travellers they had already met. They were mostly Legitimists (Royalists) on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and one can therefore imagine how many contradictory ideas have been spread about the state of France among the Christians of Lebanon. One can add only that our political disagreements have little influence on peoples whose social constitution differs greatly from ours. Catholics who are obliged to recognise the Emperor of the Turks as their sovereign have no very clear opinion concerning our political state. However, they consider themselves with regard to the Sultan as mere tribute-givers. The true sovereign is still for them the Emir Bashir, who was accompanied by the English to the Sultan’s court, after the expedition of 1840.

In quite a brief time, I found myself very much at ease with the family, and found, with pleasure, that the ceremony and etiquette of the first day vanished. The princesses, dressed simply and like the ordinary women of the country, mingled in the work of their people, and the youngest went down to the wells with the village girls, just as Rebecca did in the Bible (Genesis:24) or Homer’s Nausicaa (Odyssey: VI). At that time, much effort was being expended on the silk harvest, and I was shown the buildings, cabins of light construction, that served as silkworm nurseries. In some rooms, the worms, on tiered racks, were still being fed; in others, the ground was strewn with thorn branches on which the larvae had undergone their transformation. Cocoons, like golden olives, starred these branches heaped together into dense bushes; it was necessary to detach the chrysalises, expose them to sulphurous vapour so as to destroy the pupae, and then unwind the almost imperceptible threads. Hundreds of women and children were employed in this work, which was also supervised by the princesses.

Chapter 4: A Hunt

The day after my arrival, which was a feast day, I was wakened at daybreak for a hunt, to be performed with great display. I was about to apologise for my lack of skill in the chase, fearing to compromise European dignity in the eyes of these mountain dwellers; but it was to be merely a hunt with falcons. The prejudice that leads Orientals to pursue only noxious animals means that, for centuries, they have deployed birds of prey on which the blame for any blood-shed falls. Nature then bears the responsibility for the cruel acts committed by their agents. Thus, this type of hunting has always been foremost in the Orient. Following the Crusades, the fashion for it spread to our own countries.

I thought that the princesses would deign to accompany us, which would have given the entertainment an air of chivalry; but they failed to appear. Various servants, charged with the care of the birds, went to fetch the falcons from their hutches in the courtyard, and handed them off to the prince and two of his cousins, being the most important personages there. I was readying my fist to receive one, when I was informed that the falcons could only be held by persons known to them. There were three of these birds, all white, very elegantly hooded, and, as it was explained to me, of a breed peculiar to Syria, with eyes of a golden brilliance.

We descended into the valley, following the course of the Nahr el-Kalb, to a point where the horizon widened, and where vast meadows extended, shaded by walnut and poplar trees. Water, escaping at a bend in the river, had created vast pools half-hidden by rushes and reeds. We halted, and waited until the river-birds, frightened at first by the noise of the horses’ feet, had resumed their usual movements. When all was silent once more, we distinguished, among the birds which were feeding amidst the marsh, two herons, doubtless fishing, whose flight traced circles from time to time above the grass. The moment had come: a few shots were fired to make the herons rise, then the falcons were uncapped, and each of the horsemen holding them threw them upwards, encouraging them with shouts.

The falcons flew about randomly at first, seeking their prey, then quickly caught sight of the herons, which, attacked singly, defended themselves with their beaks. For a moment, it was feared that one of the falcons would be pierced by the beak of its victim; but, perhaps wary of the risk involved, the falcon returned to join its two companions on the perch. One of the herons, free of its enemy, disappeared into the dense foliage, while the other soared in a straight line towards the sky. Then began the true interest of the hunt. In vain, the latter heron lost itself in the heights, where our eyes could no longer see it; the falcons watched, and, unable to pursue it for the moment, waited for it to descend once more. It was a spectacle that stirred the emotions to see those three barely-visible combatants soar upwards, their whiteness blending with the azure of the sky.

After ten minutes or so, the heron, tired or perhaps no longer able to breathe, in the rarefied air of the zone it occupied, reappeared a short distance from the falcons, which swooped down on it. A momentary struggle, in which the birds approached the ground, allowed us to hear their cries, and view that furious flurry of interlaced wings, necks, and legs. Suddenly the four birds fell together to the grass, and the huntsmen were obliged to search for them, awhile. Finally, they caught the heron, which was still alive, and cut its throat, to end its suffering. They then threw a piece of flesh, cut from the belly of the prey, to the falcons, and brought back in triumph the bloody spoils of the vanquished. The prince told me of hunts he sometimes made in the Beqaa valley, where the falcons were used to catch gazelles. Sadly, the nature of such hunts involves greater cruelty than the use of weapons; since the falcons are trained to perch on the heads of the poor gazelles, and blind them. I was not at all interested in witnessing such melancholy forms of amusement.

A splendid banquet was held that evening, to which many a neighbour had been invited. Many small Turkish tables had been placed in the courtyard, in groups arranged according to the rank of the guests. The heron, the victim of the triumphant expedition, placed on a platform, with its head raised by means of iron wire and its wings fanned out, adorned the centre of the prince’s table, at which I was invited to sit, next to one of the Lazarist fathers of the monastery of Aintoura, who had been invited on this festive occasion. Singers and musicians took their places on the courtyard steps, and the lower gallery was full of groups of five or six people seated at other small tables. Dishes, barely touched, passed from the premier tables to the rest, and ended by circulating in the courtyard, where mountain-dwellers, seated on the ground, received them in turn. We had been given antique Bohemian glassware to drink from; but most of the guests sipped from cups that went the rounds. Long wax candles lit the main tables. The cuisine consisted of grilled mutton, pyramid-shaped pilau, yellowed with cinnamon powder and saffron, then fricassees, boiled fish, vegetables stuffed with minced meat, watermelon, bananas and other local fruits. At the end of the meal, toasts were drunk to the sound of instruments, and the joyful cries of the gathering; half the people seated at the table rose and drank to the others. This went on for a length of time. It goes without saying that the ladies, after having witnessed the beginning of the meal, but without taking part in it, retired to the interior of the house.

The feast continued well into the night. In general, there is little to distinguish the life of the Maronite emirs and sheikhs from that of other Orientals, except for their mingling Arab customs with certain usages akin to those of our own feudal times. They are involved in a transition from tribal life, as still established at the foot of the mountains, to that of modern civilisation, already conquering and transforming the busy coastal cities. It is akin to living in the middle of the French thirteenth century; and one cannot help thinking of Saladin and his brother Malik-Adil, whom the Maronites boast of having defeated between Beirut and Sidon. The Lazarist with whom I was seated during the meal (his name was Father Adam) offered me many details regarding the Maronite clergy. I had believed until then that they were but indifferent Catholics, given their propensity to marriage. That is, however, a specific indulgence granted to the Syrian Church. The wives of the priests are honoured by being called priestesses, but are not permitted to exercise any priestly function. The Pope also admits the existence of a Maronite Patriarch, appointed by conclave, and who, from the canonical point of view, bears the title of Bishop of Antioch; while neither the Patriarch nor his twelve suffragan bishops are allowed to wed.

Chapter 5: Keserwan

The next day we accompanied Father Adam back to Aintoura. The convent is a fairly large building on a terrace which overlooks the whole country, and at the bottom of which is a vast garden planted with enormous orange-trees. The enclosure is traversed by a stream which descends from the mountains and is received in a large basin. The church is built outside the monastery, a fairly large building which is divided into a double row of cells; the fathers, like the other monks of the mountain, cultivate olive-trees and vines. They hold classes for the children of the country; their library contains many books printed in the mountains, since there are monks who carry out the process there, and I even found a collection of a journal entitled The Hermit of the Mountain, the publication of which ceased some years ago. Father Adam told me that the first printing press had been established a hundred years ago at Mar Youhanna by a monk from Aleppo named Abdallah-Zeker, who himself engraved and cast the type. Many books of religion, history and even collections of tales, have emerged from these sacred presses. It is quite curious to see, as one passes by the walls of a monastery, printed sheets drying in the sun. Moreover, the monks of Lebanon exercise many professions; it is not they who should be reproached for laziness.

Besides the fairly numerous monasteries of the Lazarists, and the European Jesuits, who today struggle for influence and are not always friendly to one another, there are in Keserwan about two hundred monasteries of regular monks, without counting a large number of hermitages in the country about Mar Elisha. There are also numerous convents, the women being mostly devoted to teaching and education. Is this not a considerable religious population for an area of only four thousand square miles, which has less than two hundred thousand inhabitants? It is true that this portion of ancient Phoenicia has always been famous for the ardour of its beliefs. A few miles from where we were situated flows the Nahr Ibrahim, the ancient River Adonis, which is still tinged with red in the Spring, at the time when people once mourned the death of Venus’ mythological favourite. Near the place where this river enters the sea, is Jebeil, the ancient Byblos, where Adonis was born; the son, it is said, of King Cinyras — and Myrrha, the daughter of that Phoenician king. That a mythological tale, adoration, and divine honours were formerly dedicated to incest and adultery still outrages the good Lazarist monks. As for the Maronite monks, they, happily, remain profoundly ignorant of them.

The prince was kind enough to accompany me and, on several excursions, guide me through this province of Keserwan, which I would not have believed so vast or so populated. Ghazir, the principal town, which contains five churches and a population of six thousand souls, is the residence of the Hobeika family, one of the three noblest of the Maronite nation; the other two are the Howayek and the Khazen. The descendants of these three houses number in the hundreds, and Lebanese custom, which requires the sharing of estates equally between brothers, has necessarily reduced the appanage of each greatly. This explains the local jest which calls some of these emirs ‘the princes of olive and cheese’, alluding to their meagre means of existence.

The largest properties belong to the Khazen family, who reside in Zouk Mikael, a town even more populous than Ghazir. Louis XIV contributed greatly to the splendour of this family, by entrusting consular functions to several of its members. There are, in all, five districts in the part of the province called Keserwan Ghazir, and three in Keserwan Beqaa, situated towards Baalbek and Damascus. Each of these districts includes a main town ordinarily governed by an emir, and a dozen villages or parishes placed under the authority of the sheikhs. The feudal edifice thus constituted culminates in the emir of the whole province, who himself holds his powers from the Grand Emir residing at Deir al-Qamar. The latter being today a captive of the Turks, his authority has been delegated to two kaymakams or governors, one Maronite, the other Druze, who are forced to submit to the pashas all questions of a political nature.

This arrangement has the disadvantage of maintaining between the two peoples an antagonism of interest and influence, which did not exist when they lived united under the one prince. The grand idea of Emir Fakhr al-Din II, which had been to intermingle their populations and erase all prejudice as regards race and religion, has failed, and there is ever a tendency to form two enemy nations where there once existed only one, united by bonds of solidarity and mutual tolerance.

One sometimes wonders how the rulers of Lebanon managed to secure the sympathy and loyalty of so many peoples of different religion. In this connection, Father Adam told me that Emir Bashir was a Christian by baptism, a Turk by his manner of living, and would be a Druze in death, the latter people having the immemorial right to bury the sovereigns of Mount Lebanon. He also related a relevant local anecdote. A Druze and a Maronite, who were travelling together, asked one another:

— ‘What then is our sovereign’s religion?’

— ‘He is Druze’, said the one.

— ‘He’s a Christian,’ said the other.

A passing mutawali (a Twelver Shi’ite Muslim) was asked to arbitrate, and had no hesitation in replying:

— ‘He is Turkish.’

These fine people, more uncertain than ever, agreed to go to the Emir and ask him to reconcile them. Emir Bashir received them very well, and, on being informed of their quarrel, said, turning to his vizier:

— ‘These are very curious people! Let us behead all three!’

Without giving undue credence to the bloodthirsty nature of this story, one recognises within it the constant policy of the great emirs of Lebanon. It is true that their palaces contained a church, a mosque and a khalwat (Druze prayer-house). Such was for a long time the triumphant nature of their policy, which has perhaps become its major weakness.

Chapter 6: Conflict

I cheerfully accepted the mountain life, in a temperate atmosphere, amidst customs barely different from those we see in our southern provinces. It was a rest from long months spent in the heat of an Egyptian sun; and, as for the people, they were what the soul needs, possessing that empathy which is never completely exhibited by the Muslims, or which, in the majority, is thwarted by racial prejudice. I found in reading, in conversation, in ideas, those elements of Europe which one flees out of boredom, or fatigue, but which one dreams of again, after a while, as we previously dreamt of the unexpected, the strange, and the unknown. That is not to claim that our world is better than the other, it is only to revert, unconsciously, to one’s impressions of childhood, to accept the common yoke. In a well-known poem by Heinrich Heine (see Intermezzo, XXVIII) one reads of a northern fir-tree covered with snow, which seeks the arid sand and fiery skies of the desert, while at the same time a palm-tree burnt by the arid atmosphere of the plains of Egypt seeks to breathe the Northern mists, bathe in melted snow, and plunge its roots into icy ground.

In such a mood of troubling contrasts, I was already thinking of returning to the plain, telling myself, that, all things being considered, I had not visited the East to spend my time amidst Alpine landscapes; but, one evening, I heard a crowd conversing anxiously; the monks had descended from the neighbouring monasteries, in a state of terror; they spoke of the Druze who had come from their provinces in number to attack the mixed cantons, which had been disarmed by order of the Pasha of Beirut. The population of Keserwan, which is part of the Pashalik of Tripoli, had retained their weapons; it was therefore necessary to support their defenceless brethren, and cross the Nahr el-Kalb, which acts as the border to the two countries, a veritable Rubicon, only traversed in grave circumstances. Armed mountain-dwellers pressed impatiently around the village, and gathered in the meadows. Horsemen rode through the neighbouring localities shouting the old war cry: ‘Zealous for God! Zealous for combat!’

The prince took me aside, saying:

— ‘I’m unsure of the extent of this; the reports we’ve received are perhaps exaggerated, but we are always ready to help our neighbours. The pashas’ aid always arrives when harm has already been done.... You would do well, as regards yourself, to go and visit the monastery of Aintoura, or to return to Beirut by sea.’

— ‘No,’ I answered him; ‘let me accompany you. Having had the misfortune to be born in an age that is quite unwarlike, I have only viewed such conflict in our European cities, and a sad business it is, I assure you! Our mountains were blocks of houses, and our valleys squares and streets! I would wish to witness, for once in my life, a grandiose struggle, a religious war. It would be wonderful to die defending the cause that you defend!’

I said, and I thought such things; surrounded by their enthusiasm, it overcame me; I spent the following night dreaming of exploits which must of necessity have determined, on my part, the highest of destinies.

At daybreak, when the prince mounted his horse into the courtyard with his men, I prepared to do the same; but young Moussa resolutely opposed my using the horse that had been rented to me in Beirut: he was charged with returning it alive, and rightly feared its chances during a warlike expedition.

I understood the justice of his claim, and I accepted one of the prince’s steeds. We finally crossed the river, being at most a dozen horsemen among perhaps three hundred men.

After a four-hour march, we halted near the convent of Mar Youhanna, where many more mountain-dwellers joined us. The Basilian monks gave us breakfast; but, according to them, we should wait: there was no indication that Druze had invaded the district. However, the new arrivals expressed a contrary opinion, and it was decided to advance further. We left the horses to take a short-cut through the woods, and, towards the evening, after a few alerts, heard gunshots echoing among the rocks.

I had separated from the prince, and climbed a hill to arrive at a village that could be seen above the trees. I found myself with a few others at the foot of a staircase of cultivated terraces; several of the men seemed to be working in concert, and began to attack the hedge of cacti that surrounded the enclosure, so, thinking that it was a question of forcing a path towards the hidden enemy, I did the same, wielding my yatagan; the cacti’s thorny plates rolled on the ground like severed heads, and the breach was not long in yielding us a passage. Once within, my companions spread about the enclosure, and, finding no one, began to chop at the bases of the mulberry-trees and olive-trees, in an extraordinary display of rage. One of them, seeing that I was idle, wished to hand me an axe; I pushed him away; the sight of all that destruction revolted me. I had only just realised that the place we had attacked was none other than the Druze section of the village of Beit Mery in which I had been so pleasantly received a few days before.

Fortunately, I saw from a distance the majority of our people arriving on the plateau, and I joined the prince, who appeared in a great state of irritation. I approached him to ask if there were no enemies to fight but cacti and mulberry-trees; but already he deplored all that had happened, and was busy preventing their setting fire to the houses. Seeing some Maronites who were approaching with lighted fir-branches, he ordered them to return. The Maronites surrounded him, calling out:

— ‘The Druze do this to the Christians; today we are strong, we must return the favour!’

The prince hesitated at these words, the law of retaliation being sacred among the mountain-dwellers. One murder, demands another, and the same goes for fire and damage. I tried to point out to him that many trees had already been felled, and that this might suffice as compensation. He found a more persuasive reason with which to curb them.

— ‘Do you not see,’ he said to them, ‘that the flames would be seen from Beirut? They will send the Albanians again!’

This consideration finally calmed their spirits. Moreover, they found among the houses only one old man wearing a white turban, who was brought to us, and in whom I immediately recognised the good fellow who, during my passage to Beit Mery, had offered his hospitality. They took him to see the Christian sheikh, who seemed somewhat embarrassed by the tumult, and who sought, like the prince, to quell the disturbance. The old Druze maintained an exceptionally calm demeanour, gazed at the prince and said:

— ‘Peace be with you, Miran; what are you doing here?’

— ‘Where are your brethren?’ said the prince, ‘no doubt they fled when they saw us afar.’

— ‘You know that is never their custom,’ said the old man, ‘but there were only a few of them to counter all your people; they have led the women and children far from here. I chose to stay.’

— ‘We were told that you summoned the Druze from the next valley, and that they were here in large numbers.’

— ‘You have been deceived. You have listened to evil people, foreigners who would be happy to see our throats cut, so that our brothers might seek vengeance on you!’

The old man remained standing during this explanation. The sheikh, in whose presence we were, seemed struck by his words, and said to him:

— ‘Do you think yourself a prisoner here? We were once friends; why not sit down beside us?’

— ‘Because you are in my house,’ said the old man.

— ‘Come,’ said the Christian sheikh, ‘let us forget all that. Take a seat on this sofa; we will bring you coffee and a pipe.’

— ‘Do you not know,’ said the old man, ‘that a Druze never accepts anything from the Turks or their friends, for fear that it may be the product of tribute exacted, and unjust taxes?’

— ‘A friend of the Turks? Indeed, I am not!’

— ‘Did they not make you a sheikh, though I was also one, in this village, in the days of Ibrahim, when your race and mine lived together in peace? Was it not you, again, who went to complain to the Pasha about the matter of a brawl, a house burned down, a quarrel between good neighbours, which we might easily have settled between ourselves?’

The sheikh shook his head without answering; but the prince cut the explanation short, and left the house, holding the Druze by the hand.

— ‘Will you have coffee with me, I who have accepted nothing from the Turks?’ he said to him.

And he ordered his kahwedji to serve him some under the trees.

— ‘I was a friend of your father,’ said the old man, ‘and, at that time, Druze and Maronites lived in peace.’

And they conversed, for a long while, about the days when the two peoples were united under the government of the Shihab family, and were not abandoned to the arbitrariness of the victors.

It was agreed that the prince would retire with all his people, that the Druze would return to the village without summoning help from afar, and that the damage done to their houses would be considered as compensation for the previous burning of a Christian house.

Thus ended the dread expedition, in which I had promised myself I would reap so much glory; but not all quarrels in mixed villages find arbiters as conciliatory as Prince Abou-Miran had been. However, it must be said that, though instances of isolated assassination are cited, general quarrels are rarely fatal. They are somewhat akin to those quarrels between Spaniards, who pursue each other in the mountains without meeting, because one of the parties always hides if the other appears in force. There is a deal of shouting, houses are burned down, trees are felled, but the bulletins, drawn up by the interested parties, alone, claim a tally of dead.

At bottom, these two groups esteem each other more than one might think, and cannot forget the ties which formerly united them. Troubled, and roused, either by the missionaries or the monks, in the interest of European influence, they spare themselves, in the manner of the condottieri of old, who fought great battles without any bloodshed. The monks preach, one must rush to arms; the English missionaries declaim and pay, one must show oneself valiant; but at the heart of this lie doubt and discouragement. All already understand what the various European powers desire, divided in aims and interest, and seconded by the improvidence of the Turks. By stirring up quarrels in the mixed villages, they seek to prove the necessity of complete separation between two groups of people who were formerly united in solidarity. The work that is being done, at this moment, in Lebanon, under the guise of pacification, consists in forcing the exchange of properties that the Druze own in the Christian cantons for those that the Christians own in the Druze cantons. Then, there will be no more of these internal struggles so often exaggerated; there will simply be two segregated parties, one of which will perhaps be placed under the protection of Austria, and the other under that of England. It will then be difficult for France to recover that influence which, at the time of Louis XIV extended its scope to embrace both the Druze and the Maronites.

It is not for me to pronounce on such serious issues. I only regret not having taken part in a more Homeric struggle in the Lebanon.

I was soon obliged to leave the prince to visit another site on the mountain. Meanwhile the fame of the Beit Mery affair grew as I passed; thanks to the seething imaginations of the Italian monks, this battle of ours against the mulberry-trees had gradually taken on the proportions of a Crusade.

The Prisoner

Chapter 1: Morning and Evening

What shall we say of youth, my friend! Its liveliest ardour has passed, we are no longer fit to speak of it except with modesty, and yet we scarcely knew it! We scarcely realised how soon we ourselves would chant that ode of Horace’s: Eheu fugaces, Postume, Postume ... (see Horace’s ‘Odes II, 14’); so soon after first having understood it.... Ah! Study has robbed us of our most beautiful moments! The only result of so much wasted effort is the ability to understand Greek, as I, for example, this morning, understood the meaning of a Greek song which resounded in my ears, issuing from the mouth of an intoxicated Levantine sailor:

‘Nè kalimèra! Nè orà kali!’

(‘Fair is the morning! Fair is the hour!’)

Such was the refrain that this man uttered idly to the sea breeze, to the echoing waves that beat on the shore: but ‘No more the fair morning, no more the fair hour!’ was the meaning that I found in his words, and, in what I could grasp of the other verses of this popular song, there lay hidden, I believe, this thought:

‘Morning’s no more, though evening’s not here,

Yet the lightning is lost from our eyes forever!’

and the refrain was always:

‘Nè kalimèra! Nè orà kali!’

while, the song added:

‘Though roseate dawn seems like evening, so near!

Yet the night will bring mere oblivion, later!’

Sad consolation, to think of those roseate evenings of life, and of the night that must follow! We are soon arriving at that solemn hour which no longer brings morning or evening, and nothing in the world can make it otherwise. What remedy can one seek?

I envisage one for myself: which is to continue to live on this shore of Asia Minor to which fate has brought me; it seems to me, for a few months now, that I have renewed the course of my life; I feel younger; indeed, I am younger; a mere twenty years old!

I am uncertain why, in Europe, people grow old so quickly; our best years are spent at school, far from women, and we have barely had time to dress like a man when we find ourselves no longer young. The virgin of first love greets us with mocking laughter, the beautiful but more worldly ladies, at our side, dream perhaps, with vague sighs, of Cherubino!

A prejudice, no doubt, and especially in Europe, where Cherubinos are so rare. I know of nothing more gauche, more ill-made, and less graceful, in a word, than a sixteen-year-old European boy. We reproach young girls for their red hands, thin shoulders, angular gestures, and shrill voices; but what is there be said for a puny ephebe with meagre contours, the despair of the Recruitment Board? Only later do his limbs take shape, the curves become pronounced, the flesh and muscles strengthen on the bony apparatus of youth; only then is the man revealed.

In the East, children are even less attractive perhaps than in our own country; those of the rich are bloated, those of the poor are thin with enormous bellies, especially in Egypt; but the time of youth is, generally, beautiful in both sexes. The young men look like women, and those who are seen dressed in long clothes are scarcely distinguishable from their mothers and sisters; yet, for that very reason, a man is really only attractive, here, when the years have given him a more masculine appearance, a more marked character of physiognomy. A beardless lover is not quite the thing in the eyes of the lovely ladies of the Orient, so that there are a host of opportunities, for one whose years have given him a majestic but well-trimmed beard, to be the focal point of all those ardent eyes which shine above the edge of the yashmak, or whose veil of white gauze barely dims their blackness.

And then, consider that, once the cheeks are covered with a thick fleece, another stage begins, when plumpness, doubtless making the body more beautiful, would render it supremely inelegant in the tight clothing of Europe, in which even Antinous (the emperor Hadrian’s lover) would have looked like a fat countryman. That is precisely the moment when floating robes, embroidered jackets, trousers with vast pleats, and wide belts bristling with Levantine weapons, grant a man the most majestic of aspects. Let us advance a lustrum (five Roman years) further: silver threads mingle with the beard and invade the hair; the latter itself becomes lighter in hue and, from then on, the most active man, the strongest, the most capable of feeling emotion and displaying tenderness, must renounce among us all hope of ever becoming the hero of a novel. In the East, this is the finest moment of life; Under the tarbouch or the turban, it matters little whether the hair becomes thinner or greyer, the youth was never himself able to take advantage of that natural adornment; it is shaved; he forgets whether nature blessed him, in the cradle, with flat or curly hair. With his beard dyed a Persian hue, his eye animated by a light tint of bitumen, a man is, until he is sixty years old at least, sure to please, as long as he still feels capable of loving.

Yes, let us spend our youth in Europe while we can; but let us grow old in the East, the country of men worthy of that name, the land of the patriarchs! In Europe, whose institutions have suppressed material force, woman has found her strength. With the powers of intelligence, perseverance, persuasion, and seduction that heaven has bestowed upon them, the women of our country are socially the equals of men, which is more than enough for the latter to be always, and surely, defeated. I hope that you will not offer me, in contrast, some picture of a happy Parisian household to deflect me from the plan on which I base my future! I have already regretted, bitterly, having let such an opportunity slip away, in Cairo. I must unite myself with some innocent girl of this sacred soil which is our primal homeland, so that I may re-immerse myself in those life-giving sources of humanity, from which flowed the poetry and beliefs of our fathers!

You will mock my enthusiasm, which, I admit, since the beginning of my journey, has already focused its attention on several different goals; but remember also that it is a matter of grave resolution, and that never was my hesitation more natural. You know it, and this is what has perhaps provided my narrative with some interest, to date. I like to conduct my life as in a novel, and would willingly place myself in the situation of one of those active and resolute heroes who wants at all costs to create, around him, drama; to be the centre of attention; the source, in a phrase, of action. Chance, however powerful it may be, never brings together the elements of a decent plot, at most it merely arranges the staging; leave it to do as it will, and everything is abortive, despite the most beautiful of intentions. Since it is agreed that there are only two kinds of outcome, marriage or death, let us at least aim to achieve one of the two ... for, until now, my ventures have almost always ceased to advance: I have barely been able to accomplish one meagre adventure, by adding to my fortune the amiable slave that Abd-el-Kerim sold me. Doubtless, that was not difficult, but it was still needful to possess the idea and, above all, the money. I have sacrificed all hopes of the tour of Palestine which was marked on my itinerary, and which must be relinquished. For the five purses that this golden girl from Malaysia cost me, I could have visited Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Nazareth, the Dead Sea and the River Jordan! Like the prophet (Moses) punished by God, I must halt at the borders of the Promised Land, and am barely allowed to cast a desolate glance thereon from the mountain-top. Serious people might say, in response, that one is always wrong to act in a different manner to everyone else, and seek to play the Turk when one is only a simple Nazarene from Europe. Might they be right? Who knows?

No doubt I am imprudent; no doubt I have hung a large stone round my neck; no doubt I have incurred a grave moral responsibility; but must we not also believe in that fate which rules everything in this part of the world? It is she, poor Zeynab herself, who willed that her star should conjoin with mine, so I might change, perhaps in a favourable way, the nature of her destiny! What imprudence! There you reveal your European prejudice! For who knows if, taking the road to the desert alone, though richer by five purses, I might not have been attacked, pillaged, slain by a horde of Bedouins scenting my wealth from afar! Come; all is well that could be worse, as worldly wisdom has long recognised.

Perhaps you think, from this preamble, that I have resolved to marry my Javan slave and rid myself, by vulgar means, of my scruples of conscience. You know me to be sensitive enough not to have thought of selling her for a single instant; I offered to grant her freedom, but this she rejected for a simple enough reason, that she had no idea how it might serve her; moreover, I did not add to it the necessary seasoning associated with so noble a sacrifice, namely a suitable sum that would place the person, once free, forever beyond poverty, which I have been told has been the custom in such cases. To inform you of the other difficulties of my position, I must tell you what has happened to me since my return from the expedition to the mountains, of which I have sent you an account.

I returned to settle in Baptiste’s hotel for a few days, waiting for an opportunity to go by sea to Saida, the ancient Sidon. The weather was so adverse no vessel dared sail. Yet on land the sun shone, the implacable azure of the sky was untarnished by a single cloud: there was little to complain of except the wind which raises columns of dust, here and there; though, in the harbour, everything moved and swayed, and the masts and funnels of drunken ships crossed swords with one another. Nothing is more astonishing than to witness such disorder in the midst of calm — the arid storm, and a treacherous sea, its black abysses yawning beneath the sun’s bright rays. It must be doubly sad to find oneself drowning amidst such fine weather.

At the table d’hôte I met the English missionary whom I had encountered before; the storm was no less vexing to him than to me, and was preventing him undertaking the same journey. The anticipation of being, in a brief while, travelling companions, rendered our relations somewhat more intimate, and we went together, after lunch, to gaze at the fine spectacle of a stormy sea.

On our way to the harbour, we met Father Planchet, who halted, and was kind enough to chat with us awhile. It was not the least among the many things that astonish me, in this country of contrasts; the sight of a Jesuit and an evangelical missionary conversing affably. Indeed, whatever their domestic and indirect troubles, these pious adversaries continually meet at the consular tables, and maintain a good face for want of anything better to do. Moreover, apart from the occult influence that they seek to overcome in their struggles with the mountaineers, they are no longer likely, in terms of conversion, to find themselves in the same territory. The Catholic agents have long since given up converting the Druze, and hardly assail any but the schismatic Greeks, whose ideas have more in common with their own. The English missionaries, on the contrary, have at their service all the various nuances of the Protestant religion, and end up finding extraordinary points of connection between their faith and that of the Druze. Their ultimate aim being to enter as many names as possible in the little book recording the sum of their work, they manage to prove to their neophytes that deep down the English have something in common with the Druze. This explains the latter’s proverb: ‘Ingliz, Dursi, sava-sava (the English, the Druze, it’s all one)’. And perhaps, that being the case, it is the missionaries themselves who seem to be converts?

Chapter 2: A visit to the French School

On returning from my excursion in the mountains, I hastened to visit Madame Carlès boarding-house, where I had placed poor Zeynab, not wanting to take her on so dangerous a journey.

It was one of those tall houses, in Italian architectural style, whose buildings, with an interior gallery, framed a vast space, half-terrace, half-courtyard, over which floated the shadow of a striped tendido. The building had formerly served as the French Consulate, and one could still see, on the pediments, fleur-de-lis shields, formerly gilded. Orange and pomegranate trees, planted in circular holes between the flagstones, brightened a little this court, closed on all sides to external Nature. A patch of blue sky, pierced by crenellations, and traversed by the doves of the neighbouring mosque from time to time, such was the only horizon for those poor schoolgirls. As I entered, I could hear the buzz of lessons being recited, and, climbing the stairs to the first floor, I found myself in one of the galleries which led to the rooms. There, on an Indian rug, the little girls had formed a circle, squatting in the Turkish manner about a divan on which Madame Carlès sat. The two eldest were near her, and in one I recognised the slave, who ran to me with great bursts of joy.

Madame Carlès hurried to show us into her own room, leaving her place to the other tall one, who, with an initial movement natural to the women of the country, had hastened, at the sight of me, to hide her face in her book.

— ‘Thus, she is not,’ I said to myself,’ a Christian, because the latter may be viewed freely inside the house.’

Long tresses of blond hair intertwined with silk cords, white hands with slender fingers, with those long nails which indicated her nation, were all that I could grasp of this graceful apparition. I hardly noticed her, however; I was eager to learn how the slave had fared in her new position. Poor girl! She wept hot tears as she pressed my hand to her forehead. I was very moved, without knowing yet whether she had some complaint to make, or whether my long absence was the cause of this effusion.

I asked her if she was comfortable in this house. She threw her arms around her mistress, saying that she was her mother.

— ‘She is very good,’ said Madame Carlès to me in her Provençal accent, ‘but she won’t do a thing; she learns a few words with the little ones, that is all. If we seek to have her write, or try to teach her to sew, she’s unwilling. I told her: “I cannot punish you; when your master returns, he will decide what he wishes to do.”’

What Madame Carlès told me, upset me greatly; I had thought to resolve the question of the girl’s future by having her learn what was necessary, so she might later find a place, and live by herself; I was in the position of a father who sees his plans overturned by the ill-will or laziness of his child. On the other hand, perhaps my rights were not as well-founded as those of a father. I assumed the most severe air I could, and had the following conversation with the slave, facilitated by the mistress as intermediary:

— ‘And why don’t you want to learn to sew?’

— ‘Because, as soon as I am seen to labour like a servant, I will be made a servant.’

— ‘The wives of Christians, women who are free, work without being servants.’

— ‘Well, I will not be wed to a Christian;’ said the slave, ‘with us, the husband must grant his wife a servant.’

I was about to answer that being a slave, she was less than a servant; but I remembered the distinction she had already established between her position as a quaden and that of an odaleuk destined for work.

— ‘Why,’ I replied, ‘do you not wish to learn to write, either? Then you might be taught to sing and dance; which is no longer the work of a servant.’

— ‘No, but it is merely the art of an almah, of a songstress, and I prefer to remain as I am.’

We know how deeply-embedded prejudices may prove in the minds of Europeans; but it must be said that ignorance, and social habits supported by ancient tradition, render them indestructible among the women of the Orient. They consent to abandon even their faith, more readily than to abandon ideas which involve their self-esteem. But, Madame Carlès said to me:

— ‘Be, at ease; once she has become a Christian, she will see that women of our religion can work without failing in dignity, and then she will learn whatever we wish. She has attended Mass several times at the Capuchin convent, and the superior has been very edified by her devotion’.

— ‘But that proves nothing,’ I said. ‘I have seen santons and dervishes entering Cairo churches, either out of curiosity or to hear the music, while showing great respect, and meditating therein.’

On the table, beside us, was a New Testament in French. I opened the book mechanically, and found, as frontispiece, a portrait of Jesus Christ, and, further on, a portrait of Mary. While I was examining these engravings, the slave approached me, and placing her finger on the first, said:

— Aissé! (Jesus!)

And on the second:

— Miriam! (Mary!)

Smiling, I brought the open book closer to her lips; but she recoiled in fright, crying out — ‘Mafisch!’

— ‘Why do you recoil?’ I said to her. ‘Do you not honour, in your religion, Aïssé as a prophet, and Miriam as one of the three holy women?’

— ‘Yes, she said,’ but it is written: “Thou shalt not worship images.”’

— ‘You see,’ I said to Madame Carlès, ‘that her conversion has not advanced very far.’

— ‘Wait; be patient,’ Madame Carlès replied.

Chapter 3: The Akkal

I rose in a state of great irresolution. I had just compared myself to a father, and it is true that I felt a familial feeling of a sort, towards the poor girl, who had only me for support. That is certainly the only good side to slavery as it is understood in the East. Does the idea of possession, which attaches so strongly to material objects and animals, possess a less noble and lively influence on the mind, if it is transposed to creatures such as ourselves? I do not seek to apply this idea to those unhappy black slaves held in Christian countries; I am speaking here only of those slaves owned by the Muslim peoples, slaves whose position is regulated by religion and morality.

I took poor Zeynab’s hand, and gazed at her with such tenderness that Madame Carlès was doubtless mistaken in her further comments.

— ‘This is what I try to make her understand.’ she said, ‘You see, my daughter, if you seek to become a Christian, your master will perhaps marry you and take you to his country.’

— ‘Oh! Madame Carlès!’ I cried, ‘Be not so hasty in your system of conversion.... What an idea you have expressed, there!’

I had not yet thought of that solution.... Yes, doubtless, it is sad, at the moment of leaving the East for Europe, to lack any idea of what to do with the slave one has bought; but to marry her! That would be much too Christian a deed. Madame Carlès, you have not thought it through! This woman is already eighteen years old, which, for the East, is quite advanced, she has only ten years of beauty left; after which, I will be, though still young, the husband of a woman of yellow hue, who has suns tattooed on her forehead and chest, and the hole for a ring she once wore in her left nostril. Consider that she looks well in Levantine costume, but dreadful when dressed in European fashion. Do you see me entering a salon with a beauty one might suspect of cannibalistic tastes! That would be ridiculous both for her and myself.

No, conscience does not demand this of me, nor does affection advise me to do so. The slave is dear to me, no doubt, but she has belonged to other masters. She lacks education, and the very will to learn. How can I make an equal of a woman who is neither coarse or stupid, but totally illiterate? Will she come to understand the necessity for study and labour? Moreover, dare I say it? I fear it to be impossible for a deeper empathy to be established between two beings from nations so different from ours.

And yet it will be painful to leave the woman behind…

Explain who can the unresolved feelings, the conflicting ideas which mingled at that moment in my brain. I had risen, as if urged by the hour, so as to avoid granting Madame Carlès a precise answer, and we passed from her room into the gallery, where the young girls had continued to study under the supervision of the eldest. The slave went to throw herself on the neck of the latter, and thus prevented her from hiding her face, as she had done on my arrival.

— ‘Ya makbouba! (she is my dear friend),’ she cried.

And the young girl, finally letting herself be seen, allowed me to admire her features wherein European paleness was allied to the pure outline of that aquiline type which, in Asia as with us, has something regal about it. An air of pride, tempered by grace, spread an air of intelligence over her face, and her habitual seriousness made the smile she gave me when I greeted her of greater value. Madame Carlès said to me:

— ‘She is a poor, and very interesting girl, whose father is one of the mountain sheikhs. Unfortunately, he has recently been taken by the Turks. He was imprudent enough to venture into Beirut at the time of the troubles, and has been imprisoned because he has not paid his taxes since 1840. He will not recognise the present powers; that is why his property has been sequestered. Finding himself captive and abandoned by all, he has sent for his daughter, who can only visit him once a day; the rest of the time, she lives here. I teach her Italian, and she teaches the little girls true Arabic ... for she is a scholar. In her nation, women of a certain birth are permitted to educate themselves, and even occupy themselves with the arts; which, among Muslim women, is regarded as a mark of inferior status.’

— ‘Of what nation is she?’ I asked.

— ‘She belongs to the Druze people,’ replied Madame Carlès.

I observed her more attentively from then on. She saw clearly that we were talking about her, and this seemed to embarrass her somewhat. The slave had half lain down beside her on the sofa and was playing with the long tresses of her hair. Madame Carlès said to me:

— ‘They are good together; they are like night and day. It amuses them to converse, because the others are too small. I sometimes say to your slave: “If you would only follow the example of your friend, you might learn something” ... But she is only good at playing, and singing songs, all day. What would you have! When you take them on so late, you can scarcely do anything with them.’

I paid scant attention to these complaints from the good Madame Carlès, accentuated always by her Provençal pronunciation. Concerned wholly with showing me that she should not be blamed for the slave’s lack of progress, she did not see that I was especially keen, at that moment, to be informed of whatever concerned her other boarder. Nevertheless, I dared not show my curiosity too clearly; I felt that it was wrong to abuse the simplicity of a good woman accustomed to receiving the fathers of families, ecclesiastics, and other serious people ... and who viewed me solely as an equally serious client.’