Gérard de Nerval

Travels in the Near East (Voyage en Orient, 1843)

Part VI: The Women of Cairo (Les Femmes du Caire) – The Harem

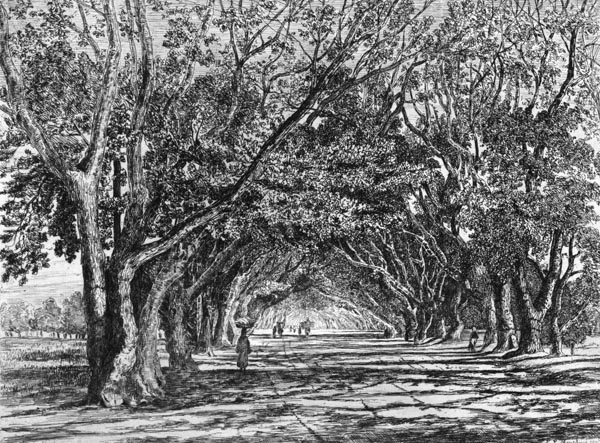

View of an avenue in Shubra, Cairo, 1876, Nicolai Yegorovich Makowski

Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter 1: Egypt’s Past and Future.

- Chapter 2: Domestic Life On Days When The Khamsin Blows.

- Chapter 3: Household Cares.

- Chapter 4 : First Lessons in Arabic.

- Chapter 5: The Kindly Interpreter.

- Chapter 6: The Island of Roda.

- Chapter 7: The Viceroy Ibrahim’s Harem.

- Chapter 8: The Mysteries of the Harem.

- Chapter 9: The French Lesson.

- Chapter 10: Shubra.

- Chapter 11: The Ifrits (Evil Spirits).

Chapter 1: Egypt’s Past and Future

I had no regrets over settling in Cairo, for some time, and rendering myself, in all respects, a citizen of the place, which is, undoubtedly, the only way to grow to understand and love it; travellers rarely take the time to grasp its inner life and penetrate its picturesque beauties, contrasts, and history. Yet it is the only Oriental city where one can find the distinctive layers of several past ages. Neither Baghdad, Damascus, nor Constantinople have retained such subjects for study and reflection. In the first two, the foreigner encounters only fragile constructions of brick and dry-earth; the interiors alone offer splendid decoration, but the conditions for serious and lasting art were never established there; Constantinople, with its painted wooden houses, is renewed every twenty years, preserving only its uniform physiognomy of bluish domes and pale minarets. Cairo owes to the inexhaustible quarries of Mokattam, as well as to the constant serenity of its climate, the existence of innumerable monuments; the eras of the Caliphs, Emirs, and Mamluk Sultans are evidenced, naturally, by their corresponding systems of architecture of which Spain and Sicily possess, to some extent, mere counterparts, or for which they provided the model. The memory of the Moorish marvels of Granada and Cordoba can be traced, at every step, in the streets of Cairo, in a mosque door, a window, a minaret, an arabesque, whose cut or style indicates their distant origin. The mosques, by themselves, tell the entire history of Muslim Egypt, since each ruler had at least one built, wishing to enshrine forever the memory of his era and his glory; it is Amr ibn al-As (c573-664AD), Ahmad ibn Tulun (835-884), Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah (985-1021), Saladin (1137-1193), Baybars (Al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars al-Bunduqdari, 1223-1277) and Barquq (Al-Malik Az-Zahir Sayf ad-Din Barquq, 1336-1399), whose names are thus preserved in the memory of the people; however the oldest of these monuments offer nothing more than crumbling walls and devastated enclosures.

The first mosque, that of Amr, built after his conquest of Egypt, occupies a site, deserted today, between the new city and the old. Nothing prevents the profanation of this place so revered in the past. I traversed the forest of columns which still supports the ancient vault; I was able to climb into the sculpted pulpit of the imam, erected in year 94 of the Hegira (Hijrah, 712AD), and of which it is said that there was none more beautiful or nobler after that of the Prophet; I went through the arcades and recognised, in the centre of the courtyard, the place where the tent of that lieutenant of Caliph Omar (Umar ibn al-Khattab) was pitched, when the idea came to him of founding a city, Old Cairo.

A dove had made its nest above the pavilion; Amr, conqueror of an Egypt under Greek rule, who had just sacked Alexandria, did not wish the poor bird to be disturbed; the place seemed to him to be consecrated by the will of heaven, and he first had a mosque built around his tent, then around the mosque a city which took the name of Fustat (founded 641), that is to say the tent. Today, this site is no longer even within the city, and is once again, as the chronicles once depicted it, in the midst of vineyards, gardens and palm-groves.

I found, at the other end of Cairo, within the walls, near the Bab-el-Nasr gate, the mosque, no less abandoned, of Caliph Hakim, built three centuries later (990-1013), and linked to the memory of one of the strangest heroes of the Muslim Middle Ages. Hakim, whom our old French orientalists called the Chacamberille, was not content with being the third of the Fatimid Caliphs, the heir by conquest of the treasures of Harun-al-Rashid, the absolute master of Egypt and Syria; the dizzying heights of grandeur and wealth rendered him a sort of Nero, or rather Heliogabalus. Like the first, he capriciously set fire to his capital; like the second, he proclaimed himself a god and laid down the rules of a religion which was adopted by a part of his people, and became that of the Druze. Hakim is the last ‘revealer’, or, if you like, the last god who appeared in the world and who still retains more or less numerous followers. The singers and narrators of the cafés of Cairo relate a thousand adventures involving him, and I was shown, on one of the peaks of Mokattam, the observatory from which he consulted the stars; since those who do not believe in his divinity at least portray him as a considerable astronomer.

His mosque is even more ruined than that of Amr. The exterior walls, and two of the towers or minarets situated at the corners, alone offer forms of architecture that can be recognized; they date from the period which corresponds to the oldest monuments in Spain. Today, the enclosure of the mosque, dusty and strewn with debris, is occupied by ropemakers who twist their hemp in that vast space, and whose monotonous spinning-wheel has succeeded the hum of prayers. Yet, is the edifice of the faithful Amr any less abandoned than that of the heretic Hakim abhorred by true Muslims? Old Egypt, forgetful as much as credulous, has buried under its dust many another prophet and many another god!

Thus, the foreigner has nothing to fear, in this country, as regards the religious fanaticism or racial intolerance of other parts of the Orient; the Arab conquest has never succeeded in transforming the character of the inhabitants to any great extent: is it not always, moreover, to this ancient and maternal land that our Europe, via the Greek and Roman world, traces its origins? Religion, morality, industry, everything started from this centre at once mysterious and accessible, from which the geniuses of early times passed their wisdom to us. They entered, in terror, those strange sanctuaries where the future of men was elaborated; and emerged, their foreheads surrounded by a divine glow, to reveal to their people traditions established prior to the flood, and dating back to the first days of the world. So, Orpheus, Moses, and that legislator well-known to us, whom the Indians call Rama, bore away a common fund of teachings and beliefs, which would alter according to place and nation, but which everywhere constituted lasting civilisation. What defines the character of Egyptian antiquity is precisely the thought of universality, and even of proselytism, that Rome later imitated, in the interest of power and glory. A people which founded indestructible monuments and engraved on them all the processes of their art and industry, and who spoke to posterity in a language that posterity is beginning to understand, certainly deserves the recognition of all men.

When mighty Alexandria had fallen, it was still, principally, Egypt, under the Saracens, which preserved and perfected that scientific knowledge on which the Christian world drew; the domination of the Mamluks extinguished its final glories, and it should be noted that the kind of obscurantism into which the Orient has fallen for three centuries, is not the result of Islam and the principles laid down by Muhammad, but of Turkish influence, in particular. Arab genius, which covered the world with wonders, was stifled by the unenlightened domination of the Turks; the angels of Islam lost their wings, the genies of the Thousand and One Nights saw their talismans broken; a sort of arid, dark Protestantism gripped all the peoples of the Levant. The Koran became, through Turkish interpretation, what the Bible was for the Puritans of England, a means of levelling everything. Islamic art, literature, and science have vanished since that time; the poetry of its primitive customs and beliefs has left only slight traces here and there, and it is Egypt which has preserved the most profound of them.

Today, its people, oppressed for so long, live only through foreign ideas; Egypt needs the return of those scattered luminaries to which it was, for centuries, home; and with what gratitude, what studious application it already imbues itself, and strengthens itself, by means of everything that flows from Europe? The masterpieces of our science and literary efforts are swiftly translated into Arabic, and immediately replicated in print; thousands of young people, raised for war, employ the leisure of peace in this labour. Should we despair of this people with inner strength, through whom Mehemet-Ali (Muhammad Ali) in recent times renewed and reconquered the ancient empire of the Caliphs, and which, without European intervention, might have overthrown Ottoman rule in but a few days? I can already foresee that in the absence of that military venture, which left Egypt exhausted by a great effort betrayed, civilisation and industry will absorb its strength and intelligence, called to action now for a different purpose. In Constantinople, recent institutions have proved sterile; in Cairo, they will yield great results when several years of peace have developed Egypt’s natural prosperity.

Chapter 2: Domestic Life On Days When The Khamsin Blows

During the khamsin, I take advantage of the long days of inaction imposed on me by studying and reading as much as possible. Since morning, the air has been hot and dusty. For fifty days, whenever the south wind blows, it is impossible to go out before three in the afternoon, when the breeze from the sea rises.

I live in the interior rooms, which are covered in tiles or marble, and refreshed by jets of water; one can spend the day in the baths, too, amidst that warm fog which fills a vast enclosure whose dome is pierced with holes, to resemble the starry sky. The majority of such baths are actual monuments that would serve very well for mosques or churches; the architecture is Byzantine, and Greek baths probably provided the first models; between the pillars on which the circular vault rests there are small marble-clad rooms, where elegant founts are dedicated to cold-water ablution. You can isolate yourself, or mingle with the crowd, in turn; a crowd which reveals none of the sickly aspect attached to our collective bathing, and is generally composed of fine healthy-looking men, draped, in the ancient manner, in long linen cloths. Their shapes are vaguely outlined through the milky mist traversed by the pale rays from the ceiling, and one might believe oneself to be in a paradise populated by fortunate shades. Except that, Purgatory awaits you in the neighbouring rooms. There one finds tubs of boiling water in which the bather undergoes various kinds of braising; there, terrible opponents their hands armed with horsehair-gloves rush upon you, and detach from your skin long molecular rolls whose thickness scares you, and makes you fearful of being gradually abraded like an over-scoured dish. One can, however, escape these ceremonies, and rest content with the well-being the humid atmosphere of the large bath provides. The notable effect of this artificial heat is to ease one after the heat outside; the earthly fire of Ptah combats the too lively ardour of celestial Horus. I cannot speak more highly of the delights of a massage, and the charming rest that one savours on one of the beds ranged round the high balustraded gallery which dominates the entrance room of the baths. Coffee, sorbets, a hookah, interrupt, or induce, that light meridian sleep, so dear to the peoples of the Levant.

Moreover, the southerly wind never blows continuously during the days of the khamsin; it often ceases for whole weeks, and literally allows you to breathe. Then the city resumes its lively aspect, crowds spread themselves about the squares and gardens; the alleys of Shubra fill with walkers; veiled Muslim women seat themselves in the kiosks, and on the rims of fountains, and tombs interspersed with shade, where they dream the day away surrounded by joyous children, and even have their meals brought to them. Oriental women have two great means of escaping the solitude of the harem: the cemetery, where they always have some dear person to mourn, and the public baths, which custom obliges their husbands to allow them to visit at least once a week.

This detail, of which I was unaware, has been for me the source of some domestic sorrow against which I must warn any European who may be tempted to follow my example. I had no sooner brought my Javanese slave back from the bazaar, than I found myself assailed by a crowd of reflections which had not yet presented themselves to my mind. The fear of leaving her a day longer among the women of Abd-el-Kerim had precipitated my resolution, while (must I say it?) the first glance I had cast upon her had been all-powerful.

There is something very seductive in a woman from a distant and unusual country, who speaks a language unknown to one, whose costume and habits are already striking due to their very strangeness, and who, in sum, lacks those detailed vulgarities that habit reveals to us in the women of our country. I suffered for some time this fascination with alien airs; I listened to her babble; I saw her display her various costumes; it was like possessing a splendid bird in a cage; but would these effects last forever?

I had been warned that if the merchant had deceived me regarding the slave’s merits, if there was any redhibitory defect, I had eight days to cancel the transaction. I scarcely thought it possible that a European would have recourse to so unworthy a clause, even if he had been deceived. Only, I saw, with a degree of pain, that this poor girl had, beneath the red headband that encircled her forehead, a burn-scar as big as a six-livre gold écu, beginning at the hairline. On her chest could be seen another scar of the same shape, and, within these two marks, a tattoo that presented the image of a sun. Her chin was also tattooed in the shape of a spearhead, and her left nostril pierced to accept a ring. As for her hair, it straggled away in front, from the temples, and around the forehead, and, except for the burnt area, fell thus to the eyebrows, which a black line extended and united according to custom. As for her arms and feet which were dyed orange, I knew that it was the effect of a preparation of henna, which would leave no mark after a few days.

What was to be done? To dress a yellow-complexioned woman in the European style would have been the most ridiculous thing in the world. I merely made a sign to her that her hair at the front should be allowed to grow again, which seemed to astonish her greatly; as for the burn on her forehead and that on her chest, which probably resulted from a custom in her land, since nothing of the sort is seen in Egypt, it could be hidden by means of a jewel or some ornament; I had therefore little to complain of, all things considered.

Chapter 3: Household Cares

The poor child had fallen asleep while I, with the solicitude of a landlord who is concerned about what has been done to damage the property he has just acquired, had been examining her hair. I heard Ibrahim call from without: ‘Ya, sidi! (Hey, sir!)’ then further words from which I understood that someone was visiting me. I left the room, and found the Jewish silk-grower, Yousef, in the gallery, wishing to speak with me. He noted that I did not ask him to enter, and we walked about smoking.

— ‘I have learned,’ he said, ‘that you have been obliged to buy a slave; I am very upset.’

— ‘And why so?’

— ‘Because you will have been cheated or robbed: a dragoman always colludes with the slave trader.

— ‘That seems most likely.’

— ‘Abdallah will have asked at least a purse for her.’

— ‘What would you have?’

— ‘The transaction is not done with as yet. You’ll be embarrassed by owning this woman, when you choose to leave, but he’ll offer to buy her back for a small price. That is what he’s accustomed to do, and that’s why he dissuaded you from concluding a marriage in the Coptic manner; which is much simpler and less costly.’

— ‘But, after all, you well know that I had some scruples about making such a marriage, which always requires a sort of religious consecration.’

— ‘Well, why didn’t you say so? I could have found you an Arab servant who’d have wed you as many times as you wished!’

The strangeness of this proposition made me burst out laughing; but when one is in Cairo, one quickly learns not to be too surprised at anything. The details which Yousef gave me taught me that there were people who were wretched enough to enter into such an arrangement. The ease with which Orientals take wives and divorce at will, makes this arrangement possible, and only a complaint from the woman can reveal it; but it is simply a means, evidently, of evading the Pasha’s severity with regard to public morals. Every woman who does not live alone or with her family must have a legally recognised husband, even though she might be divorced after eight days, unless, as a slave, she has a master.

I told Yousef how much such a convention would have repelled me.

— ‘Well!’ he said to me, ‘what does it matter … among Arabs!’

— ‘You might also say: among Christians’.

— ‘It’s a custom,’ he added, ‘which the English introduced, being so wealthy!’

— ‘So, it’s expensive?’

— ‘It used to be expensive; but now, there’s competition, and it’s within everyone’s reach.’

And this is where the moral reforms attempted here have led. An entire population becomes depraved to avoid an evil that is certainly a lesser one. Ten years ago, Cairo had public bayaderes (devadasi) like India, and courtesans, as in antiquity. The Ulama (Muslim authorities) complained, and for a long time without success, because the government levied a fairly considerable tax on these women, who were organised as a corporation, the majority of whom resided outside the city, in Al Matariyyah. Finally, the devout of Cairo offered to pay the tax in question; it was then that all these women were exiled to Esna, in Upper Egypt. Today, that city of the ancient Thebaid is a sort of Capua (the luxurious capital of ancient Campania, in Italy), to foreigners who ascend the Nile (note Flaubert’s visit, with Maxime du Camp, to the celebrated Sofia, called Kuchuk Hanem, at Esna, in 1850). The likes of Lais of Corinth, and Aspasia of Miletus (mistress to Pericles), reside there, and lead a fine life, having enriched themselves, particularly at the expense of the English. They have palaces, slaves, and are rich enough that they could have a pyramid built, like the famous Rhodope (ex-courtesan, and Queen of Memphis, she is said to have built the third pyramid), if it were still fashionable today to pile stones above one’s body to prove one’s glory; they prefer diamonds.

I quite understood that Yousef did not cultivate my acquaintance without some motive; the uncertainty I possessed with regard to the matter had already prevented me warning him of my visits to the slave bazaars. The foreigner in the Orient always finds himself in the same position as the naive lover or the son of a family in Molière’s comedies. One must navigate between Mascarille (the wily valet in several Molière plays), and Sbrigani (the schemer in Molière’s comic ballet ‘Monsieur de Pourceaugnac’). To put an end to his speculation, I complained that the price of the slave had almost exhausted my purse.

— ‘What a misfortune! cried Yousef; ‘I wanted you to share in a magnificent transaction which, in a few days, would have returned you ten times your money. I have several friends who buy the whole harvest of mulberry leaves in the vicinity of Cairo, and we resell it, in parcels, at whatever price we want, to the silkworm breeders. You need a little cash; which is the rarest thing in this country: the legal rate of interest is twenty-four per cent. However, in a sensible speculation, money multiplies.... Anyway, let us not speak of it anymore. I will give you but one piece of advice: you do not know Arabic; do not let the dragoman converse with your slave; he will communicate bad ideas to her without you realising it, and she will abscond one day; which happens.’

His words gave me food for thought.

If the custody of a woman is difficult for a husband, how much more difficult it proves for a master! That is the position of Arnolphe (in Molières ‘L’École des Femmes’), or Georges Dandin (in Molières play of that name). What can one do? The eunuch and the duenna are not suited to a foreigner; while to grant a slave the independence of a Frenchwoman, all at once, would be absurd in a country where women, it seems, show little resistance against the most vulgar methods of seduction. How can I leave her alone in the house? And how can I go about with her, in a country where no woman has ever appeared on the arm of a man? Can one understand how I failed to foresee all this?

I told Yousef to ask Mustafa to prepare dinner for me; obviously, I could not take the slave to the table d'hôte of the Domergue Hotel. As for the dragoman, he had taken himself off to await the arrival of the Suez coach; since I did not keep him busy enough, he sought, from time to time, to guide some Englishman around the city. I told him, on his return, that I only wanted to employ him for certain days, that I would not keep all these people around me, and that having a slave, I would very quickly learn how to exchange a few words with her, which was enough for me. As he had believed himself more indispensable than ever, this declaration surprised him somewhat. However, he ended by taking the matter well, and told me that I would find him at the Waghorn Hotel whenever I needed him.

He probably expected to use me as an intermediary to at least get to know the slave; but jealousy is a thing so well understood in the East, reserve is so natural in everything that has to do with women, that he never so much as mentioned it to me.

I had returned to the room where I had left the sleeping slave. She was awake and sitting on the window-sill, looking right and left into the street, through the side grilles of the moucharabia. Two houses away, there were young men in Turkish Reform costume; officers no doubt in the entourage of some personage, who were smoking nonchalantly in front of the door. I understood that danger lay there. I searched my mind in vain for a word that could make her understand that it was not good to gaze at soldiers in the street, but I found only the universal tayeb (‘very good’), an optimistic interjection well worthy of characterising the spirit of the gentlest people on earth, but quite insufficient in this situation.

O woman! In your company everything changes. I was happy, content with everything. I said tayeb at every turn, and Egypt smiled at me. Today, I must search for other words to be found perhaps in the language of this benevolent nation. It is true that I had surprised among the natives a negative word, and gesture. If something fails to please them, which is rare, they say: ‘Lah!’, raising their hand carelessly to the height of the forehead. But how can one say in a harsh tone, and yet with a languid movement of the hand: ‘Lah!’ This, however, was what I was reduced to, for want of anything better; after that, I led the slave back to the sofa, and signalled that it was more appropriate to stand there than at the window. Further, I made her understand that I would not be long in requiring dinner.

The question now was whether I should let her uncover her face before the cook; that seemed to me contrary to custom. No one, until then, had sought to view her. The dragoman himself had not ascended the stairs with me when Abd-el-Kerim showed me his women; it was therefore clear that I would be despised if I acted differently from the people of the country.

When dinner was ready, Mustapha shouted from outside:

— ‘Sidi!’

I left the room; he showed me an earthenware pot containing chicken pieces in rice.

— ‘Bono! bono!’ I said to him.

Then I continued to urge the slave to replace her mask, which she did.

Mustapha set the table, and laid a green tablecloth on it; then, having arranged a pyramid of pilau on a platter, he brought, in addition, several vegetables, on little plates, notably some koulkas (taro, colocasia esculenta) in vinegar, as well as large slices of onion swimming in a mustard sauce. Ambivalent in manner, the fellow looked untroubled. Then he discreetly withdrew.

Chapter 4 : First Lessons in Arabic

I motioned to the slave to take a chair (I had been so weak as to purchase chairs); she shook her head, and I realised that my idea was ridiculous given the table’s lack of height. So, I put some cushions on the floor, and took a seat, inviting her to sit on the other side; but nothing could persuade her. She turned her head away and put her hand over her mouth.

— ‘My child,’ I said to her, ‘do you wish to die of hunger?’

I felt that it was better to speak, even with the certainty of not being understood, than to indulge in a ridiculous pantomime. She answered in a few words which probably meant that no, she did not understand, and to which I replied: ‘Tayeb’. It was the beginning of a dialogue, at least.

Byron said that in his experience the best way to learn a language was to live alone for some time with a woman; but it would still be necessary to add some elementary text-books; otherwise, one only learns nouns, the verb is always missing; and then, it is hard to remember words without writing them down, and Arabic is not written with our letters, or at least the latter give only an imperfect idea of the pronunciation. As for learning Arabic writing, it is such a complicated matter because of the elisions, that the Comte de Volney (Constantin François de Chassebœuf), the scholar, found it simpler to invent a mixed alphabet, the use of which unfortunately other scholars failed to encourage. Science loves difficulty, and never wishes to over-popularise its studies: if one learned by oneself, what would become of the professors?

— ‘After all,’, I said to myself, ‘this young girl, born in Java, perhaps follows the Hindu religion; she probably only feeds on fruit and herbs.’

I made a sign of adoration, pronouncing the name Brahma in a questioning manner; she did not appear to understand. In any case, my pronunciation was doubtless deficient. I enumerated again all the names I knew relating to that same cosmogony; it was as if I had spoken French. I began to regret having gratified the dragoman; I was especially angry with the slave trader for having sold me this beautiful golden bird without telling me how to feed it.

I simply presented her with some bread, the best that was baked in the Frankish quarter; she said in a melancholy tone: Mafish! an unknown word whose expression saddened me greatly. I then thought of some poor bayaderes brought to Paris some years ago, whom I had been shown, in a house on the Champs-Elysées. Those Indian women only ate food that they had prepared themselves in new receptacles. This memory reassured me a little, and I resolved to go shopping with the slave, after my meal, to clear up this point.

The distrust that Yousef had inspired in me regarding my dragoman had the secondary effect of setting me on my guard against him; that is what had led to this unfortunate position. It was therefore a question of taking someone reliable along as an interpreter, in order at least to become acquainted with my new acquisition. I thought for a moment of Monsieur Jean, the Mamluk, a man of respectable age; but how could I take this woman to an inn? On the other hand, I could not leave her, and send the two hazardous servants outside awhile; was it prudent to leave a slave alone in a house closed only by a wooden lock?

A sound of little bells rang out in the street; I saw through the lattice a goatherd in a blue smock leading some goats towards the Frankish quarter. I pointed him out to the slave, who said to me with a smile: ‘Aioua!’, which I assumed meant yes.

I summoned the goatherd, a boy of fifteen, with a tanned complexion, enormous eyes, and possessing, moreover, the large nose and thick lips of the Sphinx’s head, a pure Egyptian type. He entered the courtyard with his animals, and began to milk one into a new earthenware vase that I showed to the slave before he used it. The latter repeated aioua, and, from the top of the gallery, she watched, although veiled, the goatherd’s activities.

All this was as simple as an idyll, and I found it very natural that she should address these two words to him: ‘Talé bouckra’; I understood that she was doubtless urging him to come back the next day. When the cup was full, the goatherd looked at me with a savage air and cried:

— ‘At foulouz!’

I had cultivated donkey drivers sufficiently well to know that this meant: ‘Give money.’ After I had paid him, he shouted again: ‘Bakshis!’ another favourite expression of the Egyptian, who demands a tip at every turn. I answered him: ‘Talé bouckra!’ as the slave had. He went away satisfied. That is how one learns the language, little by little.

She was content to drink her milk without seeking to dip bread in it; however, this light meal reassured me a little; I feared that she was of that Javanese people that feeds on some kind of rare earth which one could perhaps not have obtained in Cairo. Then I sent for some donkeys, and made a sign to the slave to don her outer garment (milayeh). She looked with a certain disdain at this checked cotton fabric, which is nevertheless worn everywhere in Cairo, and said to me:

— ‘An’ aouss abaya!’

How one learns! I understood that she hoped to wear silk instead of cotton, the clothes of great ladies instead of those of simple bourgeois women, and I said to her: Lah! Lah! shaking my head in the Egyptian manner.

Chapter 5: The Kindly Interpreter

I had no desire to go and buy an abaya, nor to take a simple walk; it had occurred to me that by taking out a subscription to the French reading room, the gracious Madame Bonhomme would be willing to serve as my go-between for an initial conversation with my young captive. I had only seen Madame Bonhomme before in the illustrious amateur performance which had inaugurated the season at the Teatro del Cairo; but the vaudeville she had played lent her in my eyes the quality of an excellent and obliging person. The theatre has this peculiarity, that it gives you the illusion of knowing a stranger perfectly. Hence the great passions which actresses inspire, whereas one scarcely falls in love, in general, with women one has only seen from afar.

If an actress has the privilege of exposing to all an ideal that the imagination of each interprets and realises at will, why not realise this generally benevolent function in a pretty and, if you like, even a virtuous merchant, and so to speak initiator, who might open a useful and charming conversation on behalf of a foreigner.

We know how delighted the good Doctor Yorick was (see Sterne’s ‘A Sentimental Journey’), when unknown, anxious, and lost in the great tumult of Parisian life, he found a welcome at the home of a kind and obliging glove-maker; how much more useful then, such an encounter in an Oriental city!

Madame Bonhomme accepted, with all possible grace and patience, the role of interpreter between myself and my slave. There were people in the reading room, so she showed us into her shop, selling toiletries and assorted goods, which was attached to the bookstore. In the Frankish quarter, every trader sells everything. While the slave, astonished, examined with delight the wonders of European luxury, I explained my position to Madame Bonhomme, who, moreover, had, herself, a black slave to whom, from time to time, I heard her issuing orders in Arabic.

My story interested her; I requested her to ask the slave if she was happy to belong to me.

— ‘Aioua!’ was the reply.

To this affirmative, she added that she would be very happy to be dressed like a European. This pretension made Madame Bonhomme smile, and she went off to fetch a tulle bonnet with ribbons and adjusted it on the slave’s head. I confess that it did not suit her very well; the whiteness of the bonnet made her look sickly.

— ‘My child’, said Madame Bonhomme, ‘you must remain as you are; the tarbouch suits you much better.’

And, since the slave gave up the bonnet reluctantly, she fetched her a Greek woman’s taktikos, festooned with gold, which, this time, was most effective. I saw that there was, clearly, some intention to urge the sale; but the price was moderate, in spite of the exquisite delicacy of the work.

Certain now of her redoubled benevolence, I had the adventures of this poor girl related to me in detail. It resembled all the stories of slaves, of Terence’s Andrian, of Mademoiselle Aïssé (a Circassian girl purchased by the Comte de Ferrol, Ambassador to Constantinople, during the Regency) ... understand that I did not flatter myself I would be told the whole truth. Born of noble parents, abducted as a child from the sea-shore, something that would be unlikely today in the Mediterranean but which remains probable from the point of view of the South Seas. And, besides, where could she have come from? There was no doubt about her Malay origin. The subjects of the Ottoman Empire cannot be sold under any pretext. Any person that is neither white nor black, in terms of slavery, can therefore only belong to Abyssinia or the East Indian archipelago.

She had been sold to a very old sheikh in the territory of Mecca. This sheikh having died, merchants from the caravan had taken her, and exposed her for sale in Cairo.

All this was very natural, and I was happy to believe that, in fact, she had only been owned before by that venerable sheikh, chilled by age.

— ‘She is eighteen years old,’ said Madame Bonhomme; ‘but she is very strong, and you would have paid more for her, if she were not of a people rarely seen here. The Turks are creatures of habit, they must have Abyssinians or African blacks; rest assured that she has been paraded from town to town without their being able to ride themselves of her.’

— ‘Well,’ I said, ‘then I was fated to pass by. It was reserved for me to affect her fortune for good or ill.’

This viewpoint, in accord with oriental fatalism, was transmitted to the slave, and earned me her assent.

I asked her why she had not wished to eat in the morning, and whether she was of the Hindu religion.

— ‘No, she is a Muslim.’ Madame Bonhomme told me, after speaking to her. ‘She has not eaten today, because it is a day of fasting, till sunset.’

I regretted that the woman did not belong to the Brahmanic religion, for which I had always had a weakness; as for language, she expressed herself in the purest Arabic, and had retained of her primitive language only the memory of a few songs or pantouns, which I promised myself I would have her repeat.

— ‘Now, said Madame Bonhomme, ‘how will you manage to converse with her?’

— ‘Madame,’ I said to her, ‘I already know a word with which one shows oneself satisfied with everything; only indicate to me another which expresses the opposite. My intelligence will supply the rest, while waiting for me to acquire further learning.’

— ‘Are you already at the refusal stage?’ she asked me.

— ‘I have some experience,’ I replied,’ one must plan for everything.’

— ‘Alas!’ Madame Bonhomme whispered to me, ‘that terrible word, here, is: Mafish! It covers all possible negatives.’

Then I recalled that the slave had already uttered it, when she was with me.

Chapter 6: The Island of Roda

The Consul-General invited me to visit the environs of Cairo. This was not an offer to be neglected; consuls enjoy innumerable privileges facilitating the convenience of their excursions. I had, moreover, the advantage, in this case, of having at my disposal a European carriage, a rare thing in the Levant. A carriage in Cairo is a luxury; all the finer, as it is impossible to employ it in the city; the sovereign and his representatives alone have the right to crush men and dogs in the streets, except that the narrow and tortuous form of the latter would prevent them taking advantage of it. But the Pasha himself is obliged to keep his carriages close to the city gates, and can only be conveyed to his various country houses; So, nothing is rarer than to see a coupé or a carriage, from Paris or London, and in the latest style, with a turbaned coachman on the seat, holding his whip in one hand, and his long cherry pipe in the other.

Thus, one day, I was visited by a janissary from the consulate, who knocked loudly on the door with his big cane with a silver knob, to honour me with his presence in the neighbourhood. He told me I would be expected at the consulate for the agreed excursion. We were to leave the next day at daybreak; but what the Consul did not know was that my bachelor’s lodgings had become a household, since his first invitation, and I wondered what to do about my amiable companion, during an absence of an entire day. To take her with me would have been indiscreet; to leave her alone with the cook and the porter would have been to fail in common prudence. I was much embarrassed. Finally, I thought that I must either resolve to buy a eunuch, or confide in someone. I had her mount a donkey, and we were soon in front of Monsieur Jean’s shop. I asked the former Mamluk if he knew of an honest family to whom I could entrust my slave for a day. Monsieur Jean, a resourceful man, directed me to an aged Copt, named Mansour, who, having served several years in the French army, was trustworthy in every respect.

Mansour had been a Mamluk, like Monsieur Jean, but one of the Mamluks of the French army. The latter, as he informed me, were composed mainly of Copts who, during the retreat of the Egyptian expedition, had followed our soldiers. Poor Mansour, with several of his comrades, was hurled into the water at Marseilles, by the populace, for having supported the emperor after Bourbon rule was renewed, but, as a true child of the Nile, he managed to save himself by swimming, and landed elsewhere on the shore.

We went to the home of this good man, who lived with his wife in a large, partly-collapsed house: the ceilings were bulging, and threatened the heads of the inhabitants; the wooden mesh of the windows was ripped in places like torn lace. Only the remains of furniture, and ragged cloths, adorned the ancient dwelling, where the dust and sunlight evoked an impression as gloomy as that which the rain and mud create on penetrating the poorest recesses of our cities. I felt a pang at heart to think that the greater part of the population of Cairo lived thus, in houses which the rats had already abandoned as unsafe. I refused to think, for even a moment, of leaving my slave there, but I asked the old Copt and his wife to return to my house. I promised to take them into my service, even if it meant dismissing one or other of my current servants. Besides, at a piastre and a half, or forty centimes per head, per day, I would hardly be showing prodigality.

Having thus secured the tranquillity of my household, by countering, like some clever tyrant, two suspect parties, who might have conspired against me, with a loyal one, I saw no difficulty in attending on the Consul. His carriage was waiting at the door, filled with provisions, while two janissaries accompanied us on horseback. There too, besides the secretary of the legation, was a grave personage in oriental costume, named Sheikh Abou-Khaled, whom the consul had invited, so that he might explain things to us; he spoke fluent Italian, and was considered one of the most elegant of poets, and learned as regards Arabic literature.

— ‘He is quite a man of the past,’ said the Consul to me. ‘Reform is odious to him, and yet it would be hard to find a more tolerant spirit. He belongs to that generation of philosophical Arabs, Voltaireans even, in a manner of speaking, quite unique to Egypt, who are not at all hostile to French domination.’

I asked the sheikh if there were many poets, in addition to himself, in Cairo.

— ‘Alas!’ said he, ‘we no longer live in the days when, for a fine piece of verse, the sovereign ordered the poet’s mouth to be filled with gold coins, as many as it could hold. Today, we are merely useless mouths. What good might poetry do here, except to amuse the common people at the crossroads?’

— ‘And why,’ I said, ‘should the people themselves not replace the generous sovereign?’

— ‘They are too poor,’ replied the sheikh, ‘and, besides, their ignorance is, now, such that they no longer appreciate anything but thin and artless novels, lacking any concern for purity of style. Sordid and blood-curdling tales of adventure suffice to amuse the café regulars. Even then, at the most interesting stage, the narrator stops, saying he will only continue the story when he’s received a certain sum; yet he forever delays the denouement until tomorrow, and this goes on for weeks at a time.’

— ‘Oh!’ I said, ‘All that’s no different to home!’

— ‘As for the illustrious poems of Antar (Antarah ibn Shaddad al-Absi, 525-608AD) or Abu-Zayd (Abu Zayd ibn Muhammad ibn Abi Zayd, 1186-1219),’ continued the sheikh, ‘people no longer want to listen to them except during religious festivals, out of habit. Do any understand their beauty? The people of our day can barely read. Who would believe that the most learned experts in literary Arabic, today, are two Frenchmen?

— ‘He refers,’ the Consul said, ‘to Doctor Nicolas Perron and Monsieur Fulgence Fresnel, Consul of Jeddah. You have, however,’ he added, turning to the sheikh, ‘many holy ulama with white beards who spend all their time in the libraries, within the mosques?’

— ‘Is that learning,’ said the sheikh, ‘to spend one’s whole life smoking one’s hookah, rereading the same small number of books, under the pretext that nothing is more beautiful, and that doctrine is superior to all things? Better to renounce our glorious past, and open our minds to the science of the Franks..., who nevertheless learned everything from us!’

We had exited the city wall, and left Boulaq and the smiling villas surrounding it on the right, and were driving along a wide, shady avenue, traced between the crops, which crossed a vast cultivated area belonging to Ibrahim Pasha (the general, politician, and eldest son of Muhammad Ali). It was he who had planted date palms, mulberry trees, and pharaoh’s fig-trees over all this formerly barren plain, which today seems like a garden. Large buildings serving as manufactories occupy the centre of these plantations a short distance from the Nile. Passing them, and turning right, we found ourselves in front of an arch through which one descends to the river to reach the island of Roda.

The branch of the Nile at this point appears as a small river flowing among kiosks and gardens. Thick reeds line the banks, and tradition indicates this point as being the one where Pharaoh’s daughter found the cradle containing Moses. Turning towards the south, one sees on the right the port of old Cairo, on the left the buildings of the Mekkias, or Nilometer, intermingled with minarets and domes, which cover the tip of the island.

The latter is not only a delightful princely residence, it has also become, thanks to Ibrahim’s care, the Botanical Garden of Cairo. One might expect it to be precisely the reverse of ours; that instead of concentrating heat in greenhouses, it would be necessary to create artificial rain, cold, and fog here to preserve our European plants. The fact is that, of all our trees, they have only been able to raise a poor little oak, which does not even produce acorns. Ibrahim was more fortunate in his cultivation of plants from India. The species are completely different from those of Egypt, while this latitude is even a little chilly for them. We walked with delight beneath the shade of tamarinds and baobabs; the fronds, shaped like ferns with slender stems, of coconut trees quivered here and there; and, amidst a thousand strange verdancies, I distinguished infinitely graceful bamboo avenues forming a curtain as do our poplar-trees; a small river wound across the lawns, where peacocks and pink flamingos shone in the midst of a crowd of domestic birds. From time to time, we rested in the shade of a kind of weeping willow, whose tall trunk, straight as a mast, spread around it very thick sheets of foliage; one thus believes oneself to be in a tent of green silk, flooded with gentle light.

With difficulty, we tore ourselves away from this magical scene, from its freshness, from those penetrating scents of another region of the world, to which it seemed we had been transported as if by a miracle; walking to the northern end of the island, we soon encountered plantings of a wholly different nature, doubtless intended to complete the array of tropical vegetation. In the midst of a wood composed of flowering trees which seemed like gigantic bouquets, traversing narrow paths, hidden under arches of lianas, one arrives at a sort of labyrinth of artificial rocks, surmounted by a belvedere. Between the stones, at the edge of the path, over your head, at your feet, twist, intertwine, bristle, and grimace the strangest ‘reptiles’ of the plant world. One is scarcely free of anxiety in setting foot in the lairs of sleeping serpents and hydras, among these almost living trees and plants, some of which seem to parody human limbs and recall the monstrous conformation of the tentacular gods of India.

Arriving at the summit, I was struck with admiration on seeing, in all their glory, rising above Giza which borders the other side of the river, the three famous pyramids, sharply outlined against the azure sky.

I had not seen them so clearly, and the transparency of the air allowed us, although at a distance of three leagues, to distinguish all their details.

I disagree with Voltaire, who claimed to prefer our ‘fours à poulets’ (dried-brick incubators for hatching chickens) to the Egyptian pyramids (see Voltaire’s ‘Troisième Diatribe de l’Abbé Baxin’); nor was it a matter of indifference to me to be looked down upon by forty centuries; but it was from the viewpoint of Cairo legends, and the thoughts of an Arab regarding these, that the spectacle interested me at that moment, and I hastened to ask the sheikh, our companion, what he thought of an age of four thousand years being attributed to these monuments, by European science.

The old man took a seat on the wooden sofa in the kiosk and addressed us:

— ‘Some authors think that the pyramids were built by the pre-Adamite king Jan-ibn-Jan; but, according to a tradition more widespread among us, there existed, three hundred years before the flood, a king named Surid ibn Salhouk, who dreamed one night that everything on Earth was overturned, men fell on their faces, and their houses on the men; stars clashed in the sky, and their debris covered the ground to a great height. The king awoke, utterly terrified, entered the temple of the Sun, and remained a long time bathing his cheeks and weeping, then he summoned the priests and the diviners. The priest Akliman (or Philemon), the most learned among them, told him that he himself had dreamt a similar dream, “I dreamt,” he said, “that I was with you on a mountain, and I saw the sky descend until it approached the top of our heads, and the people were crowding towards you as to their refuge, begging you to raise your hands above you and prevent the sky from falling further, and that I, acting with you, should do the same. At this moment, a voice came from the sun saying: ‘The heavens will return to their place, when I have made three hundred circuits.’ The priest having spoken thus, King Surid had readings of the stars taken, and investigated what events they foretold. It was augured that a deluge of water would be followed by a deluge of fire. It was then that the king had the pyramids built, in triangular form, suitable for withstanding the clash of the stars and the descent of the sky, and laid down those enormous stones, connected by tenons, and cut with such precision, that neither the fire of heaven nor the deluge could penetrate them. There, if necessary, the king and the nobles of the kingdom were to take refuge, with the books and images appertaining to their science, their talismans, and everything that it was important to preserve for the future of the human race.’

I listened to this legend with close attention, and told the Consul that it seemed to me much more satisfying than the supposition accepted in Europe, that these monstrous constructions were merely tombs.

— ‘But,’ I said, ‘how could people who had taken refuge in the rooms of the pyramids have breathed’

— ‘We can still see,’ the sheikh continued, ‘the outlines of wells and canals lost beneath the sand. Some of these communicated with the waters of the Nile, others correspond to vast underground caves; the water entered through narrow conduits, then emerged further away, forming immense cataracts, and continually stirring the air with a frightful noise.’

The Consul, a ‘positivist’, welcomed these traditions only with a smile; he had taken advantage of our halt in the kiosk to have the provisions brought from his carriage and laid out on a table, and Ibrahim Pasha’s bostanjis (gardeners, and guards) came to offer us, in addition, flowers and rare fruits, completing our feeling of being in Asia.

In Africa, one dreams of India, as in Europe one dreams of Africa; the ideal always gleams beyond our current horizon. As for me, I still questioned our good sheikh with avidity, and made him relate all the fabulous stories of his forefathers. I believed, with him, in King Surid more firmly than in the Cheops (Khufu) of the Greeks, their Chephren (Kafre) and their Mycerinus (Menkaure).

— ‘And what was found,’ I asked him, ‘in the pyramids when they were first opened by the Arab Sultans?’

— ‘They found,’ he said, ‘the statues and talismans that King Surid had established to guard them. The guard of the eastern pyramid was an idol of black and white tortoiseshell, seated on a throne of gold, and holding a spear, to look at which meant death. The spirit attached to this idol was a beautiful and laughing woman, who still appears in our day, and makes those who encounter her lose their minds. The guard of the western pyramid was an idol of red stone, also armed with a spear, having on its head a coiled serpent; the spirit who served it had the form of an old Nubian man, carrying a basket on his head and in his hands a censer. As for the third pyramid, it had for guard a small idol of basalt, with the same base, which attracted to it all those who looked at it, and left them unable to detach themselves from it. The spirit still appears in the form of a young man, beardless and naked. As for the other pyramids, at Sakkara, each also has its ghost: one is a swarthy, blackish old man, with a short beard; another is a young black woman, with a black child, who, when one gazes at her, displays long white teeth and white eyes; another has the head of a lion with horns; another looks like a shepherd dressed in black, holding a staff; another finally appears in the form of a monk who emerges from the sea and is reflected in its waters. It is dangerous to meet these ghosts at noon.’

— ‘So,’ I said,’ the East has ghosts of the day, as we have those of the night?’

— ‘That’, observed the consul, ‘is because everyone sleeps at midday in these regions, and this good sheikh tells us tales likely to induce sleep.’

— ‘But,’ I cried, ‘is all of this more extraordinary than the many natural things that we cannot explain? Since we believe in Creation, the Angels, the Flood, and since we cannot doubt the movement of the stars, why should we not admit that spirits are attached to these stars, and that the first men were able to establish contact with them through worship and monuments?’

— ‘Such was, in fact, the aim of primitive magic,’ said the sheikh, ‘the talismans and statues only acquired power by being consecrated to individual planets and signs, combined with their ascending and declining. The prince of the priests was called the Kater, that is to say, the master of celestial influences. Beneath him, each priest served a single star alone, as Pharouïs (Saturn), Rhaouïs (Jupiter) and the rest. Also, each morning, the Kater would ask a priest: “Where is the star, now, that you serve?” The latter would reply: “It is in such a such a sign, degree, and minute,” and, according to previous calculation, one wrote down what it was appropriate to enact that day. The first pyramid was therefore reserved for the princes and their family; the second contained the idols associated with the stars, and the tabernacles of the celestial bodies, according to the astrological, historical, and scientific texts; there too, the priests would find refuge. As for the third, it was intended solely for the preservation of the coffins of the kings and priests, and, as it soon proved insufficient, the pyramids of Sakkara and Dahshur were built. The purpose behind their solid construction was to prevent the destruction of the embalmed bodies which, according to the ideas of the time, would be resurrected at the end of a certain revolution of the stars, the exact duration of which was unknown.’

— ‘Given that were so,’ said the Consul, ‘there are numerous mummies who will be most surprised to wake one day under museum glass, or in some Englishman’s cabinet of curiosities.’

— ‘In fact, I observed, ‘they may be real human chrysalises from which the butterfly has not yet emerged. Who says they will not hatch some day? I have always regarded it as impious to strip bare and dissect the mummies of the poor Egyptians. How is it that the consoling and invincible faith of so many accumulated generations has not disarmed our foolish European curiosity? We respect the dead of yesterday; but are the dead of one particular age?’

— ‘They were infidels’, said the sheikh.

— ‘Alas!’ said I, ‘At that time, neither Muhammad nor Jesus were born.’

We discussed this point for some time, on which I was surprised to see the Muslim imitate Catholic intolerance. Why should the children of Ishmael curse ancient Egypt, which only enslaved the children of Isaac? To be truthful, however, Muslims generally respect the tombs and sacred monuments of various peoples, and only the hope of finding immense treasure had prompted the Caliph to open the pyramids. Their chronicles report that, in the so-called King’s Chamber, a statue of a man in black stone, and a statue of a woman in white stone, were discovered upright on a table, one holding a lance and the other a bow. In the middle of the table was a hermetically-sealed vase, which, when opened, was found to be full of fresh blood. There was also a cockerel of reddish-gold, enamelled with hyacinths, which crowed and flapped its wings when one entered. All this is somewhat reminiscent of The Thousand and One Nights; but what prevents us from believing that these chambers contained talismans and cabalistic figures! What is certain is that modern scholars have found no bones there other than those of an ox. The supposed sarcophagus in the King’s Chamber was doubtless a vat for lustral water. Besides, is it not more absurd, as the Comte de Volney has noted, to suppose that those many stones were piled up merely to house a five-foot long corpse?

Chapter 7: The Viceroy Ibrahim’s Harem

We soon resumed our walk, visiting a charming palace decorated in rocaille which the Viceroy’s wives sometimes inhabited in the summer. Turkish-style flowerbeds, imitating carpet-designs, surrounded this residence, which we were allowed to enter, freely. The ‘birds’ were missing from their cage, and nothing living occupied the rooms except musical clocks, which announced the quarter-hours with a little serinette (barrel-organ) air from French opera. The layout of a harem is the same in all Turkish palaces, and I had already seen several. There are always small rooms, surrounding larger lounges, with divans everywhere and, for additional furniture, small tables inlaid with tortoiseshell; and recesses, of ogive form, set in the woodwork, here and there, serve to hold hookahs, vases of flowers, and coffee cups. Only three or four rooms are decorated in the European style, and contain articles of cheap furniture which would be the pride of a porter’s lodge; but these are sacrifices to progress, perhaps the whims of some favourite, and none are of serious use to them.

But what is generally lacking in the most princely of harems are beds.

— ‘Where do these women, and their slaves, sleep?’ I asked the sheikh.

— ‘On the sofas.’

— ‘And do they have blankets?’

— ‘They sleep fully dressed. However, there are woollen or silk blankets for the winter.’

— ‘And where is the husband’s place in all this?’

— ‘Well, the husband sleeps in his room, the wives in theirs, and the slaves (odalisques, or odaleuk) on the sofas in the large rooms. If the sofas and cushions seem uncomfortable, mattresses are arranged in the middle of the room, and they sleep like that.’

— ‘Fully clothed?’

— ‘Always, but retaining only the simplest of garments: trousers, a jacket, a dress. The law forbids men, as well as women, to uncover themselves in front of each other from the throat downwards. The privilege of the husband is to view, freely, the faces of his wives; if his curiosity leads him further, his eyes are cursed: it is a formal proscription’.

— ‘I understand,’ I said, ‘that the husband may not wish to spend the whole night in a room full of fully-dressed women, and that equally he likes to sleep on his own; but if he should take with him two or three of these ladies....’

— ‘Two or three!’ cried the sheikh, indignantly, ‘What dogs do you think them to be who would act so? By living Allah! Is there a single woman, even an unfaithful one, who would consent to share with another the honour of sleeping next to her husband? Is that the way things are done in Europe?’

— ‘In Europe?’ I answered. Certainly not; but Christians have only one wife, and they suppose that the Turks, having several, live with them as we do with one.’

— ‘Were there any Muslims,’ the sheikh said, ‘depraved enough to act as the Christians suppose, their legitimate wives would immediately seek a divorce, and the slaves themselves would have the right to leave them.’

— ‘Behold,’ I said to the Consul, ‘the persistent error in Europe concerning the customs of these people. The life of the Turk is for us the ideal of power and pleasure, and yet I see that they are not even masters in their own house.’

— ‘In reality,’ the Consul replied, ‘the majority have only one wife. Daughters of good families almost always make it a condition of the alliance. A man rich enough to support and maintain several women properly, that is to say, to give each a separate lodging, a servant, and two complete sets of clothing a year, as well as a fixed sum every month for her maintenance, can, it is true, take up to four wives; but the law obliges him to devote one day of the week to each, which is not always very agreeable. Consider also that the intrigues of four women, with almost equal rights, would make his life most unhappy, if he were not a very rich and highly-placed fellow. Among the latter, the number of women is a luxury like that of horses; but they prefer, in general, to limit themselves to a legitimate wife, while possessing beautiful slaves, with whom they still do not always have the easiest relations, especially if the wife is from a noble family.’

— ‘Poor Turks!’ I cried, ‘How they are slandered! But if it is simply a matter of having mistresses here and there, every rich man in Europe has the same option.’

— ‘The Turks have the better of it,’ the Consul told me. ‘In Europe, our institutions are fierce on these points; but morality takes its revenge. Here, religion, which regulates everything, dominates both the social order and the moral order, and, as it demands nothing impossible, it is made a point of honour to observe it. It is not that there are no exceptions; however, they are rare, and hardly occurred until the reforms. The devout of Constantinople were indignant against Sultan Mahmud I, when it was learned that he had built a magnificent bathroom whereon he could watch his wives wash; but this is very unlikely, and is doubtless only a European invention.’

We walked, thus, in conversation, along a path paved with oval pebbles formed in black and white designs, and surrounded by a high border of clipped boxwood. I saw in my mind pale quadens (favoured slaves), dispersing about the paths, dragging their slippers over the mosaic pavements, and assembling in verdant rooms where large yew trees highlighted the balustrades and arches; doves must surely alight there, at times, like plaintive souls of this solitude, and I reflected that a Turk, amidst all this, could do nothing but pursue the phantom, pleasure. The Orient no longer sees great lovers or even great voluptuaries; the ideal loves of Medjnoun (see ‘Medjnoun and Leila’, by the Persian poet Nur ad-Din Abd ar-Rahman Jami) or Antar (see the tale of ‘Antar and Abla’, attributed to Al-Asmai) are forgotten by modern Muslims, while the inconstant ardour of Don Juan is unknown to them. They have beautiful palaces without loving art; beautiful gardens without loving nature; beautiful women without understanding love. I do not say this in respect of Muhammad Ali, an Albanian by origin, and who, on many occasions, showed the spirit of an Alexander; but I regret that his son and he were unable to re-establish in the East the pre-eminence of the Arab race, so intelligent, and so chivalrous in the past. The Turkish spirit prevails on the one side, the European spirit on the other; it is a mediocre result, given so much effort!

We returned to Cairo after visiting the Nilometer building, where a graduated pillar, formerly dedicated to Serapis (the solar deity of Memphis), plunges into a deep basin, and serves to determine the height of the floods each year. The Consul wished to show us the cemetery of the Pasha’s family. To view a cemetery after the harem made a sad contrast; but, in fact, a major criticism of polygamy is inherent. This cemetery, dedicated only to the children of the family, seems large enough to serve a city. There are more than sixty tombs there, large and small, new for the most part, with white marble cippi (low gravestones). Each of these cippi is surmounted either by a turban or a woman’s head-dress, which gives all Turkish tombs a look of funereal reality; it seems as if one were walking amidst a petrified crowd. The most important of these tombs are draped in rich fabrics, and bear turbans of silk and cashmere: here, the illusion is even more poignant.

It is comforting to think that, in spite of all these losses, the Pasha's family is still quite numerous. Moreover, the mortality of Turkish children in Egypt seems a fact as old as it is indisputable. Those famous Mamluks, who dominated the country for so long, and who brought there the most beautiful women in the world, have not left a single offspring.

Chapter 8: The Mysteries of the Harem

I pondered on what I had heard.

Here is another illusion to be done away with: the delights of the harem, the omnipotence of the husband or master, the bevy of charming women uniting to make one man happy! Religion or customs singularly temper this ideal, which has seduced so many Europeans. All those who, on the basis of our prejudice, understood oriental life in this way, found themselves soon discouraged. Most of the Franks who formerly entered the service of the Pasha, and, for reasons of self-interest or pleasure, embraced Islam, have today returned, if not to the bosom of the Church, at least to the sweetness of Christian monogamy.

To fully comprehend this idea, understand that a married woman, throughout the Turkish empire, has the same privileges as among us, and that she can even prevent her husband from taking a second wife, by making this point a clause in the marriage contract. And, if she consents to live in the same house as another woman, she has the right to live apart, and does not in any way contribute, as is believed, to forming graceful vignettes with the slaves, beneath the eyes of a master and husband. Let us even beware of thinking that these lovely ladies may consent to sing or dance to entertain their lord. Those are talents which seem to them unworthy of an honest woman; but every husband has the right to bring almahs and ghawasi into his harem, and so provide entertainment for his wives. It is also essential that the master of a seraglio not concern himself with the slaves he has granted to his wives, because they are thenceforth their personal property; and, if it pleases him to acquire some for his own use, he would be wise to establish them in a separate house, though nothing prevents him from employing this means of increasing his posterity.

Now, it must also be understood that, each house being divided into two completely separate parts, one devoted to the men and the other to the women, there is indeed a master on one side, but on the other, there is a mistress. The latter is the mother, or the mother-in-law, or the oldest wife, or the one who gave birth to the eldest child. The first is called the great lady, and the second the parakeet (durrah). In the case where the women are numerous, which only exists among the wealthy, the harem is a sort of convent where austere rule prevails. Its members mainly take care of raising the children, embroidery, and directing the slaves in their housework. The husband’s visits are ceremonious, as are those of close relatives, and, as he does not eat with his wives, all he can do to pass the time there is to smoke his hookah gravely and to drink coffee or sherbets. It is customary for him to see that his visits are announced some time in advance. Moreover, if he finds slippers at the door of the harem, he takes care not to enter, because it is a sign that his wife or wives are receiving a visit from their friends, and their friends often stay for one or two days.

As for the freedom to go out and make visits, it can hardly be contested in the case of a woman of free birth. The husband’s right is limited to making sure she is accompanied by slaves; but this is insignificant as a precaution, because of the ease with which the woman can subvert them, or don a disguise, either to visit the baths, or the house of one of their friends, while the guards wait at the door. The masks, and uniformity of dress, in reality, allow them more freedom than European women, if they are disposed to intrigues. The merry tales told in the evening in the cafes often revolve around the adventures of male lovers who disguise themselves as women to enter a harem. Nothing is easier, in fact; only, it must be said that this belongs more to Arab imagination than Turkish custom, which has dominated the Orient for two centuries. Let me add further that Muslim men are not given to adultery, and would find it distasteful to possess a woman who was not wholly theirs.

As for the adventures of Christians, they are rare. Formerly, there was a risk of death to both parties; today, the woman alone risks her life, but only in the situation of being caught in flagrante delicto in the marital home. Otherwise, adultery is simply a cause for divorce, and some degree of punishment.

Muslim law, moreover, has nothing that reduces women, as has been thought, to a state of slavery and abjection. They can inherit, they can own things personally, as everywhere else, and even beyond the scope of their husband’s authority. They have the right to initiate a divorce for reasons regulated by law. The privilege the husband commands is to be able to divorce without giving a reason. He only has to say to his wife in front of three witnesses: ‘You are divorced’, and she can only reclaim the dowry stipulated in her marriage contract. All know that, if he wishes to take her back afterwards, he can only do so if she has remarried in the meantime, and since become free. The use of a hulta, who is called in Egypt a musthilla, and who plays the role of an intermediary husband, is sometimes adopted on behalf of rich people only. The poor, marrying without written contract, leave each other, and take each other back, without difficulty. Finally, although it is mainly the wealthy and powerful who, through love of ostentation or personal taste, practice polygamy, there are in Cairo poor devils who marry several wives in order to live on the products of their labour. They thus have three or four households in the city, who are perfectly ignorant of each other. The discovery of such secrets usually leads to comedic disputes, and the expulsion of the lazy fellah from the houses of his various wives; for, if the law allows him several wives, it imposes on him, at the same time, the obligation to support them.

Chapter 9: The French Lesson

I found my lodgings in the same state as I had left them: the old Copt and his wife busy putting everything in order, the slave sleeping on a divan, the cocks and hens in the courtyard pecking corn, and the barbarian, who was smoking in the café opposite, waiting, attentively, for me. Further, it was impossible to find the cook; the Copt’s arrival had doubtless made him think he was about to be replaced, and he had left suddenly without saying anything; this is a frequent occurrence as regards servants or workmen in Cairo. They take care, however, to be paid every evening so they can act as they please.

I had no objection to replacing Mustapha with Mansour; and his wife, who came to help him during the day, seemed to me an excellent guardian of household morals. Except that this most respectable couple were completely ignorant of the elements of cooking, even Egyptian cuisine. Their food consisted of boiled wheat, and vegetables sliced in vinegar, they having failed to advance to the art of blending sauces or roasting. What they attempted to achieve in such directions made the slave cry out, and she commenced to shower insults on them. This character trait displeased me greatly.

I told Mansour to inform her that it was now her turn to cook, and that, wishing her to accompany me on my excursions, it would be good for her to prepare for them. I cannot convey, fully, the expression of wounded pride, or rather of offended dignity, with which she countered us all.

— ‘Tell the sidi,’ she replied to Mansour, ‘that I am a cadine (lady) and not an odaleuk (servant), and that I will write to the Pasha, if he does not grant me an appropriate position.’

— ‘To the Pasha?’ I cried. ‘What has the Pasha do with the matter? I purchase a slave to serve me, and if I cannot afford to pay servants, which may very well be the case, I cannot see why she should not do the housework, as women do in all countries.’

— ‘She says,’ said Mansour, ‘that as for the Pasha, every slave has the right to be resold, and thus exchange masters; that she is of the Muslim religion, and will never resign herself to menial tasks.’

I value pride of character, and, since she possessed the right she claimed, which Mansour confirmed as a fact, I limited myself to saying that I had been jesting; that, she need only apologise to him for her outburst; but Mansour translated this to her in such a way, that the apology, I believe, was on his side.

It was now clear that I had committed a folly in purchasing this woman. If she persisted in her idea, and remained for the rest of my stay merely an object of expense, at least she might be able to serve as my interpreter. I told her that, since she was such a distinguished person, it was fitting that she should learn French, while I learned Arabic. She did not reject the idea.

So, I granted her a lesson in speaking and writing; I made her draw letters on a sheet of paper, like a child, and taught her a few words. This quite amused her, and the pronunciation of French eliminated the guttural intonation produced by Arabian women, which is so graceless. I amused myself, greatly, by making her pronounce entire sentences whose meaning she could not as yet understand, for example: ‘I am a little savage,’ which she pronounced: Ze souis one bétit sovaze. Seeing me laugh, she decided I was obliging her to say something inappropriate, and called Mansour to translate the sentence for him. Not finding much harm in it, she repeated with great grace:

— ‘Ana bétit sovaze?... Mafish (not at all)!’ Her smile was charming.

Bored with tracing letters, in strokes thick or thin, the slave made me understand that she wanted to write (k’tab), according to her own idea of the matter. I assumed she knew how to write Arabic and gave her a blank page. Soon I saw a strange series of hieroglyphs being born beneath her fingers, which obviously did not belong to the calligraphy of any known people. When the page was full, I had Mansour ask her what she wanted me to do.

— ‘I have written for you; read it!’ she said.

— ‘But, my dear child, it represents nothing. It is only what a cat’s claws dipped in ink could trace.’

This astonished her greatly. She believed that, whenever one thought of a thing by randomly moving the pen over the paper, the idea would, thus, be clearly translated for the reader’s eye. I undeceived her, and communicated that she must state what she had wished to write, since writing would take a great deal more time to learn than she supposed.

Her naive request consisted of several items. The first renewed her claim, previously mentioned, to wear an abaya in black taffeta, like the ladies of Cairo, in order not to be confused with the ordinary fellahin women; the second indicated the desire for a dress (yalek) in green silk; and the third and last for the purchase of yellow boots, which one could not, as a Muslim, refuse her the right to wear.

It must be said here that these boots are hideous and give women a certain air of web-footedness which is most unattractive, and the rest makes them look like an enormous bundle of clothing; but, as the yellow boots, in particular, involved serious question of social pre-eminence, I promised to think about it all.

Chapter 10: Shubra

My answer appearing favourable to her, the slave stood up, clapping her hands and repeating several times:

— ‘And the fil! (The elephant!)’

— ‘What is this?’ I asked Mansour.

— ‘The siti (lady)’, he said to me after questioning her, ‘would like to go and see the elephant she has heard about, which is at the palace of Muhammad-Ali, in Shubra.’

It was only right to reward her application to her studies, and I had the donkey-drivers summoned. The city gate, on the Shubra side, was a mere hundred paces from our house. The gate is armed with large towers dating from the time of the Crusades. We crossed a bridge over a canal which widens on the left, forming a small lake surrounded by fresh vegetation. Casinos, cafes and public gardens take advantage of the freshness and shade. On Sundays, one encounters many Greeks, Armenians, and ladies from the Frankish quarter. They only remove their veils within the gardens, and then, once more, one can study the intriguing contrasts between the various peoples of the Levant. Further on, these cavalcades are lost in the shade of the Shubra promenade, certainly the most beautiful in the world. The sycamore and ebony trees which shade it for a mile and more, are all of enormous size, and the canopy formed by their branches is so dense that darkness of a sort reigns over the whole path, relieved in the distance by the burning edge of the desert, which glows on the right, beyond the cultivated land. On the left is the Nile, which runs alongside vast gardens for a similar distance, until the path borders it, and is brightened with the purple reflection of its waters. There is a café decorated with fountains and trellises, situated halfway to Shubra, and much frequented by walkers. Fields of corn and sugar-cane, and here and there a few pavilions, continue on the right, until one arrives at some large buildings which belong to the Pasha.

It was here that a white elephant given to His Highness by the English government was being shown. My companion, transported with joy, never wearied of admiring the animal, which reminded her of her own country, and which, even in Egypt, constituted a curiosity. Its tusks were adorned with silver bands, and the mahout had it perform several exercises in front of us. He even managed to make it achieve poses which seemed to me of questionable decency, but, when I signalled to the slave, veiled but scarcely blind, that we had seen enough, one of the Pasha’s officers said to me, gravely: Aspettate!... È per ricreare le donne. (Wait a moment!... It is to entertain the ladies.) There were several there, who were not at all scandalised, in fact, and who laughed out loud.

Shubra is a delightful place. The palace of the Pasha of Egypt, quite simple and of ancient construction, overlooks the Nile, opposite the plain of Embabeh, so famous for the rout of the Mamluks (at the Battle of the Pyramids, in 1798). On the garden side, a kiosk has been built whose galleries, painted and gilded, are of the most brilliant appearance. There, a truly oriental taste triumphs.