Gérard de Nerval

Travels in the Near East (Voyage en Orient, 1843)

Part IX: The Women of Cairo (Les Femmes du Caire) – Mount Lebanon

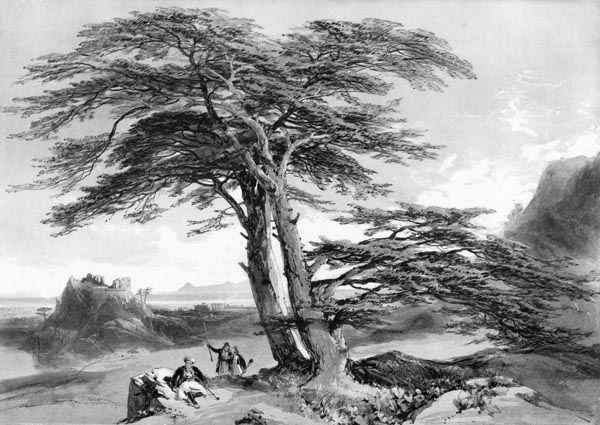

Cedars of Lebanon, 1841, James Duffield Harding

Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter 1: Father Planchet.

- Chapter 2: The Siesta (Kief).

- Chapter 3: The Table d’Hôte.

- Chapter 4: The Pasha’s Palace.

- Chapter 5: The Bazaars — The Port.

- Chapter 6: The Santon’s Tomb.

Chapter 1: Father Planchet

On exiting quarantine, I rented lodgings for a month in a house of Maronite Christians, two miles or more from the city. Most of the residences, located in the middle of gardens, arranged in tiers along the entire coast, on terraces planted with mulberry trees, look like small feudal manors, built solidly of brownstone, with ogives and arches. External staircases lead to the upper floors, each of which has its own terrace, and to the roof which dominates the entire building, and on which families gather in the evening to enjoy the view of the gulf. Our eyes encountered everywhere a thick, glossy verdure, where the regular hedges of nopals (Opuntia cacti) alone mark the divisions. I abandoned myself, during those first days of freedom, to the delights of freshness and shade. Everywhere there was life and ease around us; the well-dressed and beautiful women, free of veils, coming and going, endlessly, with heavy jugs which they fill at the cisterns, and carry gracefully on their shoulders. Our hostess, wearing a sort of draped cashmere cone, which, with the sequin-trimmed braids of her long hair, gave her the air of an Assyrian queen, was simply the wife of a tailor who had his shop in the Beirut bazaar. His two daughters, and the little children were on the first floor; we occupied the second.

The slave quickly became familiar with the family and seated, nonchalantly, on a mat, looked upon herself as surrounded by inferiors, and allowed herself to be waited on, despite whatever I could do to prevent these poor people from doing so. However, I found it convenient that I could now safely leave her in the house whenever I went to town. I was waiting for letters, which failed to arrive, the French postal service being so poor in these parts that newspapers and packages are always two months behind. This circumstance saddened me greatly, and darkened my dreams. One morning, I woke up fairly late, still half-immersed in the delusions of sleep. I found a priest seated at my bedside, who gazed at me with an air of compassion.

— ‘How do you feel, sir?’ he asked me in a melancholy tone.

— ‘Why, quite well .... my apologies, I have just wakened, and...’.

— ‘Stir not! Be calm. Collect yourself; remember that the moment is nigh.’

— ‘What moment?’

— ‘The supreme hour, so dreadful for those who are not at peace with God!’

— ‘Oh! Oh! What’s happening?’

— ‘You see me ready to hear your last wishes.’

— ‘Ah! Truly,’ I cried, ‘this is too much! And who are you?’

— ‘My name is Father Planchet.’

— ‘Father Planchet?’

— ‘From the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits).’

— ‘I know nothing of you people!’

— ‘I was told at the monastery that a young American, in mortal danger, was waiting for me to make some bequests to the community.

— ‘But I am not American! There is some mistake! And, moreover, I am not on my deathbed; as you can clearly see!’

And, with that, I rose abruptly... in need of convincing myself of my perfect health. Father Planchet finally understood that he had been misinformed. He asked the people of the house, and learned that the American lodged a little further away. He took his leave, laughing at his mistake, and promised to come and visit me when he returned, delighted as he was to have made my acquaintance, thanks to this singular chance.

When he did return, the slave was in the room, and I told him her story.

— ‘Why,’ he said to me, ‘did you burden your conscience in this manner! You have interfered with this woman’s life, and are now responsible for everything that may happen to her. Since you cannot take her to France, and you probably do not want to marry her, what will become of her?’

— ‘I will grant her freedom; it is the greatest good that a rational creature can claim.’

— ‘It would have been far better to leave her where she was: she might have found a good master, a husband.... Now, who knows into what abyss of misconduct she may fall, once left to herself? She has no skills; she has no wish to serve.... Reflect on all this.’

I had never, in fact, thought about it seriously. I asked Father Planchet for advice, who said, in answer: ‘It is not impossible that I may find her a place that guarantees her future. There are,’ he added, ‘very pious ladies in the city who would take charge of her fate.’

I warned him of the extreme devotion she had for the Muslim faith. He shook his head and began to speak to her at great length.

In fact, the woman had a religious feeling developed rather by nature, and in a general way, than in the sense of a particular belief. Moreover, the sight of the Maronite populations among whom we lived, and of the monasteries whose bells could be heard pealing in the mountains; and the frequent passage of Christian and Druze emirs, who visited Beirut, magnificently mounted and provided with brilliant weapons, amidst numerous retinues of horsemen and Africans who bore their standards behind them, rolled around lances: all that feudal apparatus, like some painting of the Crusades, which astonished even myself, taught the poor slave that there existed, even in Turkish lands, pomp and power beyond the Muslim sphere.

External effects may seduce women everywhere, especially ignorant and simple women, and often are the main cause of their sympathies or convictions. When we entered Beirut, and she passed through a crowd composed of women without veils, who wore on their heads the tantour (a sort of hennin), a decorated and gilded silver cone from which a veil of gauze hangs behind their heads, another fashion preserved from the Middle Ages, and of proud and richly armed men, whose red or multi-coloured turbans nevertheless indicated non-Islamic belief, she cried out:

— ‘What a crowd of giaours! ...’

Which softened my resentment a little, at having been insulted with that same word.

It was a question, though, of taking a stand. The Maronites, our hosts, who much disliked her manners, and judged her, moreover, from the stance of Catholic intolerance, said to me: ‘Sell her.’

They even offered to introduce a Turk to me who would undertake the transaction. You will understand what value I placed on this scarcely evangelical advice.

I went to see Father Planchet at his monastery, situated almost at the gates of Beirut. Christian children, whose education he supervised, attended classes there. We talked for a long time of Alphonse de Lamartine, whom he had known, and whose poetry he greatly admired. He complained of the difficulty he had in obtaining permission from the Turkish government to enlarge the monastery. However, partial construction revealed a grandiose plan, and a magnificent staircase, in Cyprus marble, led to floors as yet unfinished. Catholic monasteries are free to do as they wish in the mountains; but, at the gates of Beirut, they are not allowed to extend too far, and the Jesuits were even forbidden a belltower. An enormous set of chimes, modified from time to time, gradually took on the role of a belfry. The monastery buildings also grew, almost imperceptibly, under the watchful eye of the Turks.

— ‘One has to tack a little,’ Father Planchet told me; ‘but with patience, one arrives.’

He spoke to me again of the slave in a kind and sincere way. Yet I was contending with my own uncertain arrangements. The letters I awaited might arrive any day, and alter my plans. I feared that Father Planchet, deluding himself out of pity, mainly had in view the honour that would accrue to his monastery if a Muslim woman converted, and that after all the fate of the poor girl might become sadder later.

One morning she came into my room clapping her hands and crying out in fright:

— ‘Durzi! Durzi! Bandouguillah! (The Druze! The Druze! Shooting!)’

Indeed, the sound of shots echoed in the distance; it was an improvisation by some Albanians who were about to leave for the mountains. I made inquiries, and learned that the Druze had burned a village called Beit Mery, situated a few miles away. Turkish troops were being sent, not against them, but to watch the movements of the two parties who were still fighting at that stage.

I was in Beirut, when I heard the news. I returned very late, and was told that an emir or Christian prince from some area of Lebanon had chosen to lodge in the house. Learning that a Frank from Europe also lodged there, he wished to see me and had waited for me awhile in my room, where he had left his weapons as a sign of trust and fraternity. The next day, the noise made by his retinue woke me early; he had with him six well-armed men, and all rode magnificent horses. We soon became acquainted, and the prince suggested that I go and visit him in the mountains for a few days. I quickly seized on such a wonderful opportunity to study the events that take place there, and the customs of that singular population.

During my visit, it would be necessary to place the slave, whom I could not think of taking with me, in suitable hands. I was told of a school for young girls in Beirut run by a lady from Marseilles, named Madame Carlès. It was the only one in which French was taught. Madame Carlès was a very kind woman, who asked me only three Turkish piastres a day for the slave’s maintenance, and food. I was due to leave for the mountains three days after I had placed her there; she had already become very accustomed to it and was delighted to talk with the little girls, who were greatly amused by her ideas and stories.

Madame Carlès took me aside and told me that she did not despair of bringing about the slave’s conversion.

— ‘Here,’ she added in her Provençal accent, ‘is how I seek to do so. I say to her: ‘You see, my daughter, the true gods of every country are all the one true God. Muhammad is a man of great merit ... but Jesus Christ is a very good man too!’

This tolerant and gentle way of carrying on the conversion seemed most acceptable to me.

— ‘You mustn’t force her to do anything,’ I told her.

— ‘Don’t be too concerned’ replied Madame Carlès; ‘she has already promised, of her own accord, to attend Mass with me next Sunday’

Certainly, I could not leave her in better hands, to learn the principles of the Christian religion, and the French language...as spoken in Marseille.

Chapter 2: The Siesta (Kief)

Beirut, if one considered only the space enclosed by its ramparts, and the internal population, would correspond only loosely to the idea of it held in Europe, which recognises it as Lebanon’s capital. One must also take into account the few hundred houses surrounded by gardens that occupy the vast amphitheatre of which this port is the centre, a scattered herd guarded by a tall square building, furnished with Turkish sentinels, called the tower of Fakr al-Din. I was staying in one of these houses, which are scattered along the coast like the bastides that surround Marseilles, and, about to leave for the mountains, I had time only to visit Beirut and obtain a horse, mule, or even a camel. I would have accepted one of those beautiful asses with the long neck, and zebra-striped leggings, which are preferred to horses in Egypt, and which gallop through the dust with tireless ardour; but in Syria the breed is not sturdy enough to climb the stony roads of Lebanon. Yet should the creature not be blessed above all others, having served as a mount for the prophet Balaam, and for the Messiah?

I was thinking about this, as I walked to Beirut, at that time of day when, according to the Italian expression, one hardly sees anyone wandering about in the full sun except gli cani e gli Francesi (dogs and Frenchmen). Now, this saying has always seemed false to me with regard to dogs, who, at siesta time will stretch out in a cowardly manner in the shade, in no haste to be suntanned. As for the Frenchman, try to keep him on a sofa or a mat, especially if he has business afoot, or a whim or even a simple curiosity to satisfy! The demon of midday rarely weighs on his chest, nor is it for him that shapeless Smarra rolls yellowish eyes in his large dwarfish head (see Charles Nodier’s tale ‘Smarra, or the Demons of the Night’, 1821)

Thus, I was crossing the plain at a time when Southerners devote themselves to the siesta, and the Turks to kief. A man who wanders thus, when everyone is asleep, runs a great risk, in the East, of exciting the same suspicions that a nocturnal vagabond would among us; yet the sentinels of the tower of Fakr al-Din granted me merely that compassionate attention a soldier on watch grants to a passer-by out late. From this tower, a vast plain reveals, at a glance, the whole eastern profile of the city, whose enclosure and crenellated towers extend as far as the sea. It possesses the physiognomy of an Arabian city at the time of the Crusades; except that the modern European influence is betrayed by the numerous masts of the consular houses, which, on Sundays and holidays, are decked with flags.

As for Turkish domination, it has, as everywhere, applied here its personal and unique stamp. The Pasha had the idea of demolishing a portion of the city walls onto which the Fakr al-Din palace backs, so as to erect one of those wooden kiosks, painted according to the fashion prevailing in Constantinople, which the Turks prefer to the most sumptuous palaces of stone or marble. Do you wish to know why the Turks only live in wooden houses? And why the very palaces of the Sultan, although decorated with marble columns, have only firwood walls? The reason, in accord with a prejudice peculiar to the Ottomans, is that the house that a Turk builds for himself must last no longer than he himself does; it is akin to a tent erected in transit, a temporary shelter by means of which he should not seek to fight against destiny, by perpetuating his line, that is by attempting that difficult union of world and family, to which Christian peoples aspire.

The palace forms an angle, at the rear of which stands the city gate, with its cool, dark passageway, where one can recover a little from the heat of the sun, reflected by the sandy plain one has crossed. A beautiful stone fountain shaded by a magnificent sycamore, the grey domes of a mosque and its graceful minarets, a brand-new bathhouse of Moorish construction, these are what are offered to the eye on entering Beirut, with the promise of a pleasant and peaceful visit. Further on, however, the walls rise and take on a dark, cloistered appearance.

Why not spend time in a bathhouse, during those hours of intense and dreary heat that I would otherwise spend wandering the deserted streets sadly? I was thinking of entering one, when the sight of a blue curtain stretched in front of its door informed me that it was the hour when only women were allowed in the baths. Men have only the morning and the evening to themselves ... and woe, no doubt, to any who would lie asleep on a divan or a bed at the hour when one sex succeeds the other! Frankly, only a European would be capable of such an idea, which would confound the mind of a Muslim.

I had not entered Beirut before at that ungodly hour, and I felt like a man from the Thousand and One Nights entering a city of the Magi, the populace of which has been turned to stone. All were still fast asleep; the sentinels at the gate, the donkey-drivers in the square waiting for the ladies, probably also asleep in the upper galleries of the bathhouse; the sellers of dates and watermelons established near the fountain, the kawhedji in the coffee shop serving his customers, the hamal, or porter, his head resting on his burden, the camel-driver beside his crouching beast, and the large Albanian ‘devils’ forming a guard corps in front of the Pasha’s seraglio: all were sleeping the sleep of the innocent, leaving the city deserted.

It was at a similar hour and during a similar sleep that three hundred Druze seized Damascus, one day. It sufficed for them to enter separately, and mingle with the crowd of country folk who, in the morning, fill the bazaars and squares; then they pretended to fall asleep like the others; but groups of them, skilfully distributed, seized the principal posts at the same moment, while the main troop pillaged the rich bazaars and set fire to them. The inhabitants, awakened with a start, believed they were dealing with an army and barricaded themselves in their houses; the soldiers did the same in their barracks, so that at the end of an hour, the three hundred horsemen returned, laden with booty, to their unassailable retreats in Lebanon.

That is what a city risks by slumbering in broad daylight. However, in Beirut, the European colony does not give itself over entirely to the pleasure of the siesta. Taking a street on the right, I soon distinguished movement in a second street opening onto the square; a penetrating smell of fried food revealed the vicinity of a trattoria, and the sign of the celebrated Battista was not long in attracting my gaze. I was too familiar with hotels in the Orient intended for travellers from Europe to have thought, previously, of taking advantage of the hospitality of Signor Battista, the only Frankish innkeeper in Beirut. The English have spoiled these establishments everywhere, usually more modest in their appearance than in their pricing. I thought, however, that it might be a good idea, at that time of day, to take advantage of the table d’hôte, if they would serve me. I ascended the stairs, to find out.

Chapter 3: The Table d’Hôte

On reaching the first floor, I found myself on a terrace amidst buildings dominated by interior windows. A vast white and red tendido protected a long table, set in European style, from the sun, and almost all the chairs were tipped forwards, to mark the untaken places. On the door of a room at the back and on the same level as the terrace, I read these words: Qui si paga sessenta piastre per giorno. (The price here is sixty piastres a day.)

Some Englishmen were smoking cigars there, while waiting for the bell to ring. Soon two women came down, and seated themselves at a table. Near me was a serious-looking Englishman, who was being served by a young man with a copper-coloured face wearing a robe of white bazin, and silver earrings. I thought the Englishman must be some nabob with an Indian in his service. This personage was not slow to address me, which surprised me a little, the English rarely speaking to anyone other than those who have been introduced to them; but this one was in a unique position: he was a missionary of the Evangelical Society of London, charged with making English conversions in all countries, and forced to forgo the cant on many occasions to attract souls into his nets. He had just descended from the mountains, and I was delighted to be able to obtain some information from him before entering them myself. I asked him for news of the recent alert which had disturbed the environs of Beirut.

— ‘It’s, nothing’ he said, ‘the affair was a failure.’

— ‘What affair?’

— ‘A battle between Maronites and Druze, in villages where the live alongside each other.’

— ‘So, you’ve come,’ I said to him, ‘from the area where they were fighting?’

— ‘Yes, indeed. I went to pacify ... to bring peace, to everything in the canton of Bikfaiya, because England has many friends in the mountains.’

— ‘Are the Druze, then, friendly towards England?’

— ‘Oh, indeed. These poor people are very unhappy; they are slaughtered, they are burned, their wives are disembowelled, their trees and crops are destroyed.’

— ‘Pardon me, but in France we imagine that it is they, on the contrary, who oppress the Christians!’

— ‘Oh! Lord, no; what, those poor people! They are unfortunate farmers who perform nothing evil; but your Capuchins, your Jesuits, your Lazarists kindle war, and excite the Maronites against them, who are much more numerous; the Druze defend themselves as best they can, and, without England, they would already be crushed. England is always on the side of the weakest, of those who suffer....’

— ‘Yes, I said, you are a great nation.... So, you have managed to quell the troubles that have taken place in recent days?’

— ‘Oh! Certainly. There were several of us English there; we told the Druze that England would not abandon them, that they would receive justice. They set fire to the village, and then they returned home quietly. They accepted our offer of more than three hundred Bibles, and we converted many of those good people!’

— ‘I don’t understand,’ I observed to the Reverend, ‘how one can convert them to the Anglican faith; since they would have to become English subjects.’

— ‘Oh! no.... They belong to the Evangelical Society, and are protected by England; as for becoming English, they cannot.’

— ‘And who is the head of Anglican religion?’

— ‘Oh! It is Her Gracious Majesty, our Queen of England.’

— ‘Well, she makes a charming female pope, and I swear to you that in itself would be enough to convince me to convert.’

— ‘Oh! You French; you are always jesting.... You are no true friends of England.’

— ‘Moreover,’ I said, suddenly remembering an episode from my early youth, ‘one of your missionaries, in Paris, once undertook to convert me... I have even kept the Bible that he gave me; but I am still trying to discover how one can make an Anglican of a Frenchman.’

— ‘Yet there are many among you ... and, if you received, as a child, the word of truth, then it may well mature in you later.’

I refrained from attempting to disabuse the Reverend, for one becomes very tolerant when travelling, especially when one is guided simply by curiosity, and a desire to observe the local customs; but I saw that the circumstance of my having formerly known an English missionary granted me some right to the confidence of my neighbour at table.

The two English ladies I had noticed were placed on the left of my Reverend, and I soon learned that one was his wife, and the other his sister-in-law. An English missionary never travels without his family. This one appeared to be living in grand style, and occupied the principal apartment of the hotel. When we had risen from table, he went to his room for a moment, and soon returned, holding a sort of album, which he showed me, triumphantly.

— ‘Here,’ he said to me, ‘are the details of the abjurations that I obtained in my last tour in favour of our holy religion.’

A multitude of declarations, signatures, and Arabic seals covered, indeed, the pages of the book. I noticed that his register was kept in double entry; each verso gave the list of the presents and sums received by these Anglican neophytes. Some had received only a rifle, a cashmere, or ornaments for their wives. I asked the reverend if the Evangelical Society gave him a bonus for each conversion. He had no difficulty in admitting it; it seemed natural to him, as well as to me, that costly and dangerous journeys should be amply remunerated. I realised again, in the details added, the superiority that the wealth of English agents give them in the East over those of other nations.

We had taken our places on a sofa in the conversation room, and the Reverend’s copper-hued servant knelt before him to light his hookah. I asked if this young man was not Indian by origin; but he was, it seems, a Parsee from the neighbourhood of Baghdad, and the result of one of the Reverend’s most brilliant successes, a convert whom he was taking back to England as a sample of his labours.

In the meantime, the Parsee served him as a servant as well as a disciple; he doubtless brushed his clothes with fervour and polished his boots with compunction. I pitied him a little, inwardly, for having abandoned the worship of Ahura Mazda for the modest employment of an evangelical underling.

I hoped to be introduced to the ladies, who had retired to their apartment alone; but the Reverend retained all the customary English reserve on this point. While we were still talking, the sound of military music rang loudly in our ears.

— ‘There is a reception,’ the Englishman said, ‘at the Pasha’s. A deputation of Maronite sheikhs has come to air their grievances before him. They are people who are always complaining; but the Pasha is hard of hearing.’

— ‘One can tell that by the music, I said; I’ve never heard such a din.’

— ‘And yet it is your national anthem that is being performed; it is the Marseillaise.’

— ‘I would hardly have guessed.’

— ‘I only know because I hear it every morning and evening, and I was told that they thought they were performing that tune.’

Paying closer attention, I managed, indeed, to distinguish a few stray notes in a crowd of flourishes of specifically Turkish music.

The city seemed more definitely awake, the three o’clock sea breeze gently stirred the canvases stretched on the terrace of the hotel. I took leave of the Reverend, thanking him for the polite attentions he had shown me, which are rare among the English only because of that social prejudice which warns them against strangers. It seems to me that there is in that, if not a proof of selfishness, at least a lack of generosity.

I was surprised to have to pay only ten piastres (two francs fifty centimes) for the table d’hôte when leaving the hotel. Signor Battista took me aside, and issued a friendly reproach for my not having come to stay at his hotel. I showed him the sign announcing that one was only admitted for sixty piastres a day, which brought the expense to eighteen hundred piastres a month.

—Ah! Corpo di me! he cried. Questo è per gli Inglesi, che hanno molto moneta, e che sono tutti cretici!... ma, per gli Francesi, e altri Romani, è soltanto cinque franchi! (That’s for the English, who have a lot of money, and are all heretics! ... but for the French and other Roman Catholics it is only five francs!)

— ‘That’s quite different!’ I thought.

And I applauded myself all the more for not belonging to the Anglican religion, when one encountered among the hoteliers of Syria such Catholic and Roman sentiments.

Chapter 4: The Pasha’s Palace

Signor Battista completed his good deed for the day by promising to find me a horse for the next morning. Reassured on that matter, I was left with nothing to do but stroll about the town, and I began by crossing the square to view what was happening at the Pasha’s castle. There was a large crowd there, in the midst of which the Maronite sheikhs were advancing two by two like a procession of supplicants, the vanguard of which had already entered the palace courtyard. Their ample red or multi-coloured turbans, their mishlahs (camel-hair coats) or kaftans embroidered with gold or silver, and their gleaming weapons, all that exterior luxury which, in other countries of the Orient, is the preserve of the Turkish race alone, gave to this procession a most imposing aspect. I managed to enter the palace behind them, where the music continued to transform the Marseillaise with major reinforcements of fifes, triangles and cymbals.

The courtyard is formed by the enclosure of the old palace of Fakr al-Din. There, one can still distinguish traces of the Renaissance style, which this Druze prince was fond of, following his journey to Europe. One should not be surprised to hear the name of Fakhreddine II, or in Arabic Fakr-al-Din, cited everywhere in this country: he is the hero of Lebanon; he is also the first sovereign of Asia who deigned to visit our northern climes. He was received at the court of the Medici (in 1612), revealing something unheard of at the time, that is to say, that there existed in the land of the Saracens a people devoted to Europe, either by religion or by sympathy.

Fakr al-Din passed in Florence for a philosopher, heir to the Greek science of the Late Empire, preserved through Arabic translations which saved so many precious books and transmitted their contents to us; in France, they wished to see in him as a descendant of some former Crusader who had taken refuge in Lebanon at the time of Saint Louis; they sought, in the alliterative name of the Druze people itself, a relationship which would render him the descendant of a certain Count of Dreux. Fakr al-Din accepted all these suppositions with the prudent and subtle laissez-faire of the Levantines; he needed Europe, in order to fight against the Sultan.

He passed for a Christian in Florence; he perhaps became one, as has the Emir Bashir in our day, whose family succeeded that of Fakr al-Din in sovereignty over of Lebanon; but he was always a Druze, that is to say the representative of a singular religion, which, formed from fragments of all previous beliefs, allows its followers to accept, momentarily, all possible forms of worship, as the Egyptian initiates did in the past. In reality, the Druze religion is only a sort of Freemasonry, according to modern ideas.

Fakr al-Din represented for a time the idea the West had formed of Hiram, the ancient king of Lebanon, a friend of Solomon, and a hero with mystical associations. Master of all the coasts of ancient Phoenicia and Palestine, he attempted to create, from the whole of Syria, an independent kingdom; the support that he expected from the monarchs of Europe was lacking to him in that regard. Now, his memory remains, for Lebanon, an ideal of glory and power; the ruins of his buildings, destroyed by war rather than time, rival the ancient works of the Romans. Italian artists, whom he had summoned to decorate his palaces and cities, sowed, here and there, schools of ornamentation, sculpture, and architecture, which the Muslims, returning as victors, hastened to destroy, astonished at seeing the pagan arts, which their conquests had long eclipsed, suddenly reborn.

It is thus, in the very place where those fragile marvels existed for too short a space of time, where the breath of the Renaissance had, from afar, re-sown a few seeds of Greek and Roman antiquity, that the wooden kiosk built by the Pasha stands. The members of the Maronite procession had lined up beneath the windows awaiting the governor’s good pleasure. Moreover, it was not long before they were introduced.

When the vestibule doors were opened, I perceived, among the secretaries and officers who were stationed in the room, the Armenian who had been my sailing companion on the Santa-Barbara. He was clad in new clothes, bore a silver writing-case at his belt, and held in his hand parchments, and pamphlets. It was not surprising, in the land of Arabian legend, to find a poor devil, whom one had lost sight of, attain a good position at court. My Armenian recognised me at once, and seemed delighted to see me. He wore the costume of the Reform, as a Turkish employee, and already expressed himself with a certain dignity.

— ‘I am pleased,’ I said, ‘to see you in a suitable situation; you seem to me to be a man in office, and I regret having nothing to solicit.’

— ‘Lord,’ he said to me, ‘I have earned little credit as yet, but am entirely at your service.’

We were talking like this behind a column in the vestibule while the procession of sheikhs progressed towards the Pasha’s audience hall.

— ‘And what do you do here?’ I said to the Armenian.

— ‘I’m employed as a translator. The Pasha asked me yesterday for a Turkish version of this booklet here.’

I glanced at the pamphlet, printed in Paris. It was a report by Adolphe Crémieux regarding an affair concerning the Jews of Damascus. Europe has forgotten this sad episode, which relates to the murder of a certain Father Thomas, of which the Jews had been accused. The Pasha felt the need to shed light on this matter, which had been concluded five whole years ago. That is conscientiousness, certainly.

The Armenian had also been asked to translate Montesquieu’s L’Esprit des Lois, and a manual written for the Parisian National Guard. He found the latter work difficult indeed, and asked me to help him with certain expressions that he did not understand. The Pasha’s idea was to create a national guard in Beirut, as, indeed, one now exists in Cairo, and many other cities of the Orient. As for the Spirit of the Law, I think the work had been chosen on the basis of its title, perhaps thinking that it contained police regulations applicable to all countries. The Armenian had already translated part of it, and found the work agreeable, and written in an easy style, which doubtless lost very little in translation.

I asked him if he could aid me in viewing the reception of the Maronite sheikhs by the Pasha; but no one was admitted without showing a pass, which had been given to each of them, for the sole purpose of presenting themselves to the Pasha, since it is the case that Maronite and Druze sheikhs customarily lack the right to enter Beirut. Their vassals enter without difficulty; but there are severe penalties for they themselves, if, by chance, they are encountered within the city. The Turks fear their influence on the population, or the brawling which might break out in the streets due to the meeting of these leaders, who always go about armed, accompanied by a large retinue, and are constantly ready to fight over questions of precedence. It should be noted, however, that this law is only rigorously observed in times of trouble.

Moreover, the Armenian informed me that the audience with the Pasha was limited merely to receiving the sheikhs, whom he invited to sit on divans around the room; that, once there, slaves brought each of them a chibouk and then served them coffee, after which, the pasha listened to their grievances, and invariably answered that their adversaries had already come to him with identical complaints; that he would reflect carefully to see on which side justice lay; and that one could hope for everything from the paternal government of His Highness, before whom all religions and all races of the empire would always have equal rights. In terms of diplomatic procedures, at least, the Turks are the equals of Europeans.

It must be recognised, moreover, that the role of the Pashas is not easy in this country. We know what a diversity of the races inhabits the long chain of Mount Lebanon and Mount Carmel, and which dominates from there, as from a fortress, all the rest of Syria. The Maronites recognise the spiritual authority of the Pope, which places them under the protection of France and Austria; the united Greeks, more numerous but less influential because they are generally scattered about the level countryside, are supported by Russia; the Druze, with the Alawites and Matawalis (Shia Muslim splinter groups) who belong to beliefs or sects which Muslim orthodoxy rejects, offer England a means of action which other powers abandon to it too generously.

It was the English who, in 1840, succeeded in drawing the support of those energetic populations away from the Egyptian government. Since then, their internal politics have tended to divide the various groupings whom a general feeling of nationality might, as before, unite under a common leadership. It was with this thought in mind, that the English (in the form of Sir Sidney Smith, the English naval commander) accompanied to the Ottoman court (in 1799), the Emir Bashir Shihab II, last of the princes of Lebanon, the heir to that power, various and mysterious at source, which, for three centuries, had united all the Lebanese factions and religions under the same roof.

Chapter 5: The Bazaars — The Port

I left the palace courtyard, and traversed a dense crowd, which seemed drawn there simply by curiosity. On entering the dark streets formed by the lofty houses of Beirut, all built like fortresses, and connected, here and there, by arched passageways, I found again the hum of life, which had been suspended during the hours of siesta; folk from the mountains thronged the immense bazaar which occupies the central district, and which is organised by type of merchandise and produce. The presence of women tending the various stalls is a remarkable peculiarity for the Orient, explained by the rarity of Muslims among the population.

Nothing is more entertaining than to walk those long aisles, the booths protected by curtains in various colours, which still permit a few rays of sunlight to play over the fruits, and brightly-hued vegetables, or even make the embroidery on the rich clothes hanging from the doors of the clothes-stalls, gleam. I felt the longing to add to my costume a decoration, of a particularly Syrian nature, which consists of draping the head and temples with a square silk scarf, striped with gold, which is called a keffiyeh, and which is secured by encircling it with a twisted cord of horsehair; the usefulness of this headgear is to protect the ears and the neck from draughts, so dangerous in mountainous country. I was sold a brightly coloured one for forty piastres, and, having tried it on at a barber’s, found myself adorned like a king of the Orient.

Some of these squares of silk are made in Damascus; others are from Bursa, or Lyons. Long silk cords, knotted and tasselled, spread gracefully over the back and shoulders, and satisfy that male coquetry natural in countries where one can still wear beautiful costumes. It may seem childish; yet it seems to me that the dignity of the exterior reflects the thoughts and actions of life; there is a certain masculine self-assurance also to be derived from the further addition, according to Eastern custom, of wearing weapons at one’s belt: one feels that one is both respectable and respected on all occasions; while rudeness and quarrels are rare, since all know that the slightest insult may result in bloodshed.

I never saw such lovely children as those who were running about in play in the most beautiful alley of the bazaar. Slender, laughing young girls crowded around the elegant marble fountains decorated in the Moorish style, and departed from them, one after the other, carrying on their head large vases of antique shape. In this country one sees plenty of red-haired individuals, the colour, darker than in our country, possessing something of a purple or crimson hue. This colour is so well-regarded in Syria that many women dye their blond or black hair with henna, which, everywhere else, is used only to redden the soles of the feet, the nails, and the palms of the hands.

There were also sellers of iced-drinks and sorbets, at the various intersections of the alleys, mixing them on the spot with snow collected from the summit of Mount Sannine. A brightly-lit café, at the centre of the bazaar, frequented mainly by the military, also supplied iced and perfumed drinks. I halted there for a while, never tired of watching the movement of that energetic crowd, which brought together in one place all the varied mountain costumes. There is, moreover, something comical in the sight of those gilded cones (tantours), more than a foot high, which the Druze and Maronite women wear on their heads, the long, attached veil of which, hanging down over their faces, they sweep about at will, in the act of buying and selling. The positioning of this ornamentation gives them the air of those fabled unicorns which serve as a support for the coat of arms of England. Their outer costume is uniformly white or black.

The city’s main mosque, which overlooks one of the streets of the bazaar, is an old Crusader church in which you can still view the tomb of a Breton knight. Leaving this district to visit the port, you descend a wide street, dedicated to free-trade. There, the goods of Marseilles compete quite happily with products from London. On the right is the Greek quarter, filled with cafés and restaurants, where that nation’s taste for the arts is manifested by a host of coloured woodcuts, which enliven the walls with principal scenes from the life of Napoleon, and from the Revolution of 1830. To contemplate one of these art-galleries at leisure, I requested a bottle of Cyprus wine, which was soon brought to where I was seated, with a recommendation to keep it hidden in the shadow of the table. There was no reason to scandalise passing Muslims by their seeing wine being drunk. However, the aqua vitae, which is anisette, is consumed ostentatiously.

The Greek quarter is linked to the port by a street inhabited by bankers and money-changers. High stone walls, barely pierced by a few windows and barred archways, surround and hide courtyards and interiors in the Venetian style; they are a remnant of the splendour that Beirut long-owed to the governance of the Druze emirs, and their commercial relations with Europe. The consulates are for the most part established in this quarter, which I crossed quickly. I was eager to reach the port, and abandon myself entirely to the impression of the splendid spectacle that awaited me there.

O Nature! The beauty, the ineffable grace of those cities of the Orient, built on the sea-coast, those shimmering pictures of life, spectacles full of the most beautiful human specimens, of costumes, boats, ships ploughing the azure waves; how to describe the impression that you grant every dreamer, and which is nonetheless simply the reality of a feeling long-anticipated? One has already read of this scene in books, and admired it in paintings, especially in those old Italian pictures that relate to the era of Venetian and Genoese maritime power; but what is surprising is to find it still, today, so like the idea one has formed of it. One rubs shoulders, in surprise, with a motley crowd seeming to date back two centuries or more, as if the mind has returned to a past age, as if the splendour of times long gone have been, for an instant, recreated. Am I really the child of a serious country, of a century in dark clothes that seems forever in mourning for those that preceded it? Here I am myself transformed, observing and yet posing, at the same time, as some figure out of a seascape by Claude-Joseph Vernet.

I took a seat in a café, set on a platform supported by sections of columns, acting as stilts, sunk into the sea-bed. Through the cracks in the decking, one could see the greenish waves beating the shore beneath one’s feet. Sailors from every country, mountaineers, Bedouins in white robes, Maltese, and a few Greeks with the air of pirates, smoked and chatted around me; two or three young kahwedjis served and refilled, here and there, the fengans, encircled with golden filigree, full of foaming mocha; the sun, descending towards the island of Cyprus, barely hidden by the extreme line of the islets, illuminated, here and there, the picturesque embroidery that still gilds a poverty of ruins; it cast, towards the right of the quay, an immense shadow, that of the maritime castle which protects the harbour, a mass of towers grouped amidst rocks, towers whose walls were pierced and torn apart by the English bombardment of 1840. They are now little more than debris, surviving due their mass, and attesting to the iniquity of pointless devastation. To the left, a jetty projects into the sea, bearing the white buildings belonging to the Customs officers; like the quay itself, it is formed almost entirely from the ruined columns of ancient Phoenician Berytus, or the Roman city of Julia Felix (so named in honour of Augustus’ daughter).

Will Beirut ever regain the splendour that thrice rendered her the Queen of the Lebanon? Today, it is her location at the foot of verdant mountains, amidst gardens and fertile plains, at the end of a graceful bay that Europe continually fills with its vessels, the trade with Damascus, and her position as a central point of rendezvous for the industrious populations of the mountains, which guarantee a powerful future for Beirut. I know of nothing more animated, more alive than this port, nor which better realises the ancient idea that Europe has of those ‘Ports of the Levant’ (Échelles du Levant), in which tales or comedies were set. Does one not dream of mysterious adventures, on viewing those tall houses, those barred windows, at which we imagine the faces of bright-eyed and curious young girls? Who would dare to enter those fortresses of marital and paternal power, or rather, who would not be tempted to dare? But, alas, adventures here are rarer than in Cairo; the population is as serious as it is busy about its own affairs; the women’s attire proclaims both effort and ease. One’s general impression of the scene is of something biblical and austere: those high promontories projecting into the sea, the great sweeping lines of landscape formed by the various levels of the mountain range, the crenellated towers and ogival arches, lead the mind to meditation, and reverie.

To view this fine spectacle more widely, I left the café and headed for the Raz-Beirut promenade, situated on the left side of the city. The reddish lights of the setting sun tinged with charming hues the chain of mountains which descends towards Sidon; the whole coastline to the right showed the outlines of rocks and, here and there, natural basins which the flood fills on stormy days; women and young girls were dipping their feet in these pools, while bathing little children. There are many of these basins which seem like the remains of ancient baths, their floors paved with marble. On the left, near a small mosque which overlooks a Turkish cemetery, one can view enormous columns of red granite flat on the ground; is this, as is claimed, the site of Herod Agrippa’s circus?

Chapter 6: The Santon’s Tomb

I was trying to resolve this question internally, when I heard singing and the sound of instruments rising from a ravine which borders the walls of the city. It seemed to me it might be a wedding, since the character of the songs was joyous; but I soon saw a group of Muslims appear, waving flags, followed by others who bore on their shoulders a body laid on a kind of litter; various women came next, shouting, then a crowd of men, with flags again, and branches.

They all halted at the cemetery and laid the body, entirely covered with flowers, on the ground; the proximity of the sea lent grandeur to the scene, as did the impression aroused by the curious songs which they intoned in drawling voices. A crowd of passers-by had gathered, at this point, and were contemplating the ceremony, respectfully. An Italian merchant, nearby, informed me that this was no ordinary burial, and that the deceased was a santon who had lived for a long time in Beirut, the Franks regarding him as a madman, and the Muslims as a saint. His residence had been, in recent times, a cave beneath a terrace in one of the gardens of the city; it was there that he had lived, completely naked, in the manner of a wild beast, and that people had come from many a place to consult him.

From time to time, he would make a tour of the city and take whatever he liked from the shops of the Arab merchants. In their case, they were full of gratitude, thinking it would bring them good luck; but, after a few visitations in this singular manner, the Europeans, not sharing their opinion, had complained to the Pasha and obtained a ruling that the santon should no longer be allowed to leave his garden. The Turks, few in number in Beirut, had not opposed the measure, and limited themselves to maintaining the santon with provisions and presents. Now, this character having died, the people gave themselves up to joyful celebration, since Turkish saints are not mourned in the manner of ordinary mortals. The certainty that, after many privations, he had finally won eternal beatitude, rendered them happy as regards the event, and it was celebrated to the sound of instruments; in the past, such funerals even involved dancing, almahs singing, and public feasting.

Meanwhile, the door of a small square domed building, intended as the tomb of the santon, had been opened, and the dervishes at the centre of the crowd lifted the corpse on to their shoulders. As they were about to enter, they seemed as if driven back by an unknown force, and almost fell. There was a cry of stupefaction from the gathering. The dervishes turned towards the crowd in mock anger, feigning that the mourners who followed the body, and those who were chanting hymns, had interrupted their songs and cries for a moment. They began again with more unity; but, as they were about to cross the threshold, the same resistance was renewed. A group of old men then raised their voices.

— ‘It is, they said, ‘a whim of the venerable santon; he does not wish to enter the tomb feet first.’

The body was turned around, and the chanting began again; another manifestation of the whim, another retreat by the dervishes who carried the coffin.

There was a consultation.

— ‘Perhaps,’ said some of the faithful, the saint finds this tomb unworthy of him; a finer one must be built.’

— ‘No, no,’ said a group of Turks, ‘we must not yield to all his wishes; the holy man was always of an uneven disposition. Let us try to carry his corpse inside; once he’s within, perhaps he’ll like it; moreover, there’s always time to settle him somewhere else.’

— ‘How is that to be done?’ cried the dervishes.

— ‘Well, you must turn about, swiftly, to daze him a little, and then, without giving him time to gather himself, you can push him through the opening.’

This plan united all the mourners; the chants sounded once more, with renewed ardour, and the dervishes, grasping the coffin at both ends, rotated it for a few minutes; then, with a sudden movement, rushed through the door, this time with complete success. The people awaited with anxiety the result of this bold manoeuvre; they feared, for a moment, lest the dervishes had fallen victim to their own audacity, and the walls had collapsed on them; but they soon emerged in triumph, announcing that after some difficulties, the saint had remained motionless: whereupon the crowd shouted with joy, and dispersed, either into the countryside or into the two cafés which overlook the coast of Raz-Beirut.

This was the second Turkish miracle that I had been allowed to see (you will recall that of the Dohza, whereby the Sheriff of Mecca rode on horseback along a path paved with the living bodies of the faithful); but here the spectacle of this capricious corpse in the arms of the bearers, who was agitated and refused to enter his tomb, brought to mind a passage from Lucian of Samosata (see ‘De Dea Syria: The Syrian Goddess’) who attributes the same whim to a bronze statue of the Syrian Apollo. This was sited in a temple in the east of Lebanon, whose priests, once a year, set out, according to custom, to wash their idol in a sacred lake. Apollo refused this ceremony for a long time.... He disliked water, doubtless as prince of the celestial fires, and visibly agitated himself on the shoulders of the bearers, whom he overturned several times.

According to Lucian, this manoeuvre was simply due to certain gymnastic tricks of the priests; but should we place complete confidence in this assertion by an ancient forerunner of Voltaire? For my part, I have always been more disposed to believe everything than deny everything, and, since the Bible admits the wonders attributed to the Syrian Apollo, who was none other than Baal, I do not see why the power granted to the rebellious genius and spirit of his Pythian counterpart could not have produced such effects; nor do I see why the immortal soul of a poor santon could not exert a powerful influence over believers convinced of his sanctity.

Moreover, who would dare to be sceptical at the foot of Mount Lebanon? Is not this shore the very cradle of all Levantine belief? Ask the first mountain dweller who passes by: they will tell you that it is in this region of the Earth that the primitive scenes of the Bible took place; they will lead you to the place where smoke rose from the first sacrifice; they will show you a rock stained with the blood of Abel; not far away existed the city of Enoch, built by the giants, a city of which one can still distinguish the traces; elsewhere, is the tomb of Canaan, son of Ham. Share the mind of a Greek of antiquity and, descending from these mountains, you will see, as well, the whole procession of smiling divinities whose cult Greece accepted, transformed, and propagated via Phoenician migrations. These woods and mountains echoed to the cries of Venus weeping for Adonis, and it was in these mysterious caves that idolatrous sects still celebrated their nocturnal orgies, where they prayed and wept over an image of her lover, a pale idol of marble or ivory with bleeding wounds, around which tearful women repeated the plaintive cries of the goddess. The Christians of Syria conduct similar solemnities on the night of Good Friday: a weeping mother takes the place of the lover, but the sculpted imitation is no less striking; the forms of the feast described so poetically in that idyll by Theocritus have been preserved (see ‘Idyll XV’).

Consider also that many primitive traditions have only been transformed, or renewed, in fresh cults. I am not too sure if our Church places much credence in the legend of Simeon Stylites, and one may well, without irreverence, find the system of mortification of this saint a mere exaggeration; but Lucian also tells us that certain devotees, in ancient times stood for several days on high stone columns that Bacchus had erected not so far from Beirut (at Hierapolis according to Lucian), in honour of Priapus and of Juno.

But let us rid ourselves of the burden of ancient memories and religious reverie to which the appearance of the locale, and the mix of peoples so invincibly lead, who perhaps sum up in themselves all the beliefs and superstitions of the region. Moses, Orpheus, Zoroaster, Jesus, Muhammad, and even Buddha, possess, here, more or less numerous disciples.... Would it not be easy to conceive that all this must animate the city, fill it with ceremonies and festivals, and render it akin to the Alexandria of Roman times? But no; all is calm and gloomy, these days, given the influence of modern ideas. It is in the mountains, where such influence is felt less, that we shall doubtless find again those picturesque customs, those strange contrasts that so many authors have indicated, and so few have been able to observe.

The End of Part IX of Gérard de Nerval’s ‘Travels in the Near East’