Gérard de Nerval

Travels in the Near East (Voyage en Orient, 1843)

Part IV: The Women of Cairo (Les Femmes du Caire) – Coptic Marriage

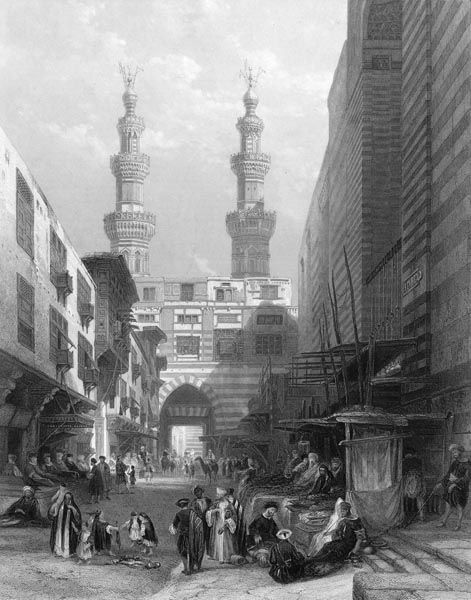

View of the market at the Bab Zuweila gate of Cairo, 1846 - 1855, David Roberts

Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter 1: The Mask and the Veil.

- Chapter 2: A Wedding by Torchlight.

- Chapter 3: Abdallah, the Dragoman.

- Chapter 4: The Disadvantages of Celibacy.

- Chapter 5: El Mosky.

- Chapter 6: An Adventure in the Besestain Bazaar.

- Chapter 7: A Dangerous House.

- Chapter 8: The Wakil (Envoy).

- Chapter 9: The Rosetta Gardens.

Chapter 1: The Mask and the Veil

Cairo is the city of the Levant where women are still the most hermetically veiled. In Constantinople, in Smyrna, a face-covering of white or black gauze sometimes allows the features of beautiful Muslim women to be guessed at, and even the most rigorous edicts rarely succeed in forcing them to adopt a denser version of the frail fabric. They are graceful and coquettish nuns who, devoting themselves to a single husband, are not sorry, however, to endow the world with a regret or two. But Egypt, serious and pious, is still the country of enigma and mystery; beauty surrounds itself there, as in the past, with veils and wrappings, and this gloomy attitude easily discourages the frivolous European. Such, leave Cairo after a week or so, and hasten to visit the cataracts of the Nile, and meet with other disappointments that science has in store, which they will never acknowledge.

Patience was the greatest virtue of the ancient initiates. Why progress so swiftly? Let us halt here, and seek to lift a corner of the austere veil of the goddess of Sais (Isis). Besides, is it not encouraging to see that in a country where women pass for prisoners, the bazaars, streets and gardens nonetheless present them to us by the thousands, walking, aimlessly, alone, or in pairs, or accompanied by a child? Really, European women have less freedom: the women of distinction go about, it is true, perched on donkeys and therefore in an inaccessible position; but, among us, women of the same rank hardly venture out except in carriages. There remains the veil ... which, perhaps, does not create as severe a barrier as one might believe.

Among the rich Arabian and Turkish costumes that Reform spares, the mysterious dress of the women grants the crowd that fills the streets the joyous aspect of a masked ball; the colour of the dominoes varies only from blue to black. The great ladies hide their waists beneath the abaya (loose-fitting robe) of light taffeta, while the ordinary women drape themselves, gracefully, in a simple blue tunic of wool or cotton (quamis), like antique statues. The imagination has more to work on in feminine faces that pass by incognito, a mystery which fails to extend to all their charms. Beautiful hands adorned with talismanic rings and silver bracelets; arms of pale marble escaping entirely, on occasion, from their wide sleeves raised to the shoulder; bare feet laden with rings which the slipper abandons at each step, and whose ankles resonate with a silvery noise, are what one is allowed to admire, to guess at, to surprise, without the crowd becoming concerned or the woman herself seeming to notice. Sometimes the floating folds of the white and blue chequered veil that covers the head and shoulders are disturbed a little, and the gap that appears between that garment and the elongated covering that is called a burqa reveals a graceful temple where brown hair twists in tight curls, as in the busts of Cleopatra; or a small, firm ear from which a cluster of gold sequins, or a plaque worked with turquoise and silver filigree hangs to tremble about the neck and cheek. Then, one feels the need to interrogate the eyes of the veiled Egyptian, and they are the most dangerous. The burqa is composed of a long, narrow piece of black haircloth that descends from head to foot, and is pierced with two holes like the hood of a penitent; a few shiny ringlets thread the space between the forehead and the rest of the mask, and it is behind this rampart that ardent eyes await you, armed with all the seduction they can borrow from art. The eyebrow, the orbit of the eye, even the eyelid behind the eyelashes, are brightened with dye, and it would be impossible to better highlight that small portion of her person that a woman, here, has the right to reveal.

I did not, at first, understand what is so attractive about this mysterious mode of dress in which the more interesting half of the people of the Orient envelop themselves; but a few days were enough for me to learn that a woman who feels noticed generally finds a way to let herself be seen, if she is beautiful. Those who are not, know better how to maintain their veils, and who can blame them. This is indeed the land of dreams and illusions! Ugliness is concealed like a crime, while one can always glimpse something of what constitutes form, grace, youth and beauty.

The city itself, like its inhabitants, only gradually reveals its most shaded retreats, its most charming interiors. On the evening of my arrival in Cairo, I was mortally sad and discouraged. In a few hours of riding on a donkey, and in the company of a dragoman (guide and interpreter), I had succeeded in convincing myself that I was about to spend there the six most tedious months of my life, and yet everything was fated in advance so that I could not reside there one day less.

— ‘What! Is this,’ I said to myself, ‘the city of the Thousand and One Nights, the capital of the Fatimid Caliphs, and the Sultans?’...

And, as evening approached, the shadows descending quickly, thanks to the dust that stains the sky and the tops of the houses, I plunged into the inextricable network of narrow, dusty streets, amidst the ragged crowd, the congested throng of dogs, camels, and donkeys,

What can one hope for from this confused labyrinth, perhaps as large as Paris or Rome, from these palaces and mosques that number in their thousands? All this was once splendid and marvellous, no doubt, but thirty generations have passed; everywhere the stone is crumbling and the wood rotten. It seems that one is moving in a dream, in a city of the past, inhabited only by ghosts, who populate it without animating it. Each district, surrounded by crenellated walls, closed by solid doors as in the Middle Ages, still preserves the appearance that it doubtless had at the time of Saladin (Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, the Kurdish founder of the Ayyubid dynasty, and the first Sultan of Egypt and Syria); long vaulted passages, here and there, lead from one street to another; more often one enters a cul-de-sac and must return. Little by little everything shuts down; only the cafes are still lit, while smokers occupying palm-frond chairs, beneath the vague glow of night-lights swimming in oil, listen to some long story delivered in a nasal tone. However, the moucharabias are lit up: these are wooden grilles, curiously worked and cut, which extend onto the street and serve as windows; the light which penetrates them is not enough to guide the passer-by; especially since the hour of curfew soon arrives; everyone carries a lantern, and one scarcely encounters anyone outside except Europeans, or soldiers making their rounds.

As for me, I could no longer find anything to do in the streets at that hour, that is to say ten in the evening, and I went to bed, in a sad mood, telling myself that it would doubtless be like this every day, and despairing of the pleasures of this fallen capital.... My initial bout of sleep was disturbed, in an unexplained manner, by the vague sounds of a bagpipe and a hoarse viol, which irritated my nerves greatly. This obstinate music repeated the same melodic phrase in various tones, and awakened in my mind the memory of some Burgundian or Provençal Christmas carol. Did it belong to dream, or reality? I hovered a while, but found myself waking completely. It seemed to me that I was being borne away, in the manner of a burlesque yet a serious manner too, amidst both religious chants, and drinkers crowned with vine-branches; a kind of patriarchal gaiety was fused with a mythological sadness in this strange concert, where church lament formed the basis of a hectic tune suitable for marking the steps of a dance of Corybantes (the priests of Cybele). The noise drew closer, grew louder; I had risen, still quite numb, when a great light, penetrating the trellis outside my window, informed me, finally, that here was a completely earthly spectacle. However, what I had thought mere dream was true, in part: near-naked men, crowned like ancient wrestlers, fought in the midst of the crowd with swords and shields; but they constrained themselves to striking the bronze with the blade in time to the music, and, setting off again, began the same simulacrum of wrestling, only further on. Numerous torches, and pyramids of candles carried by children, lit the street, brightly, leading a long procession of men and women, the details of which I could not distinguish. Something like a crimson ghost, wearing a jewelled crown, advanced slowly between two stern matrons, while a confused group of women in blue brought up the rear, uttering at each station a shrill cackle, to most singular effect.

It was unmistakably a wedding, there was no longer room for error. I had seen in Paris, among the engraved plates of the artist Louis-François Cassas, a complete depiction of such ceremonies (see his ‘Voyage Pittoresque de la Syrie etc.’, issue VI, Plate VI); but what I had just seen through the window-lattice was not enough to extinguish my curiosity, and I desired, whatever might happen, to follow the procession and observe it further, at my leisure. My dragoman, Abdallah, to whom I communicated this idea, pretended to shudder at my boldness, caring little for racing through the streets in the depths of night, and spoke to me of the danger of being assassinated or beaten. Fortunately, I had bought one of those camel-hair cloaks called a mishlah (also a bisht, or aba) which cover a man from shoulders to feet; with my already-long beard and a handkerchief twisted around my head, the disguise was complete.

Chapter 2: A Wedding by Torchlight

The difficulty lay in catching up with the procession, which had vanished into the labyrinth of streets and cul-de-sacs. The dragoman had lit a paper-lantern, and we raced along at random, guided or misled from time to time by the distant sound of bagpipes or by the glare of light reflected from the corners of crossroads. At last, we reached the entrance to a different district than ours; the houses were lit, the dogs howled, and there we were in a long street flamboyant and resounding, filled with people even on the housetops.

The procession advanced slowly, to the melancholy sound of instruments that imitated the creaking noise of an obstinate door, or a cart trying out its new wheels. The culprits of this din about twenty in number, marched along surrounded by men carrying fiery lances. Next came children carrying enormous candelabra whose candles threw a bright light everywhere. The wrestlers continued to fence at each other during the numerous halts the procession made; others, mounted on stilts and wearing feathered headdresses, attacked each other with long sticks; further on, young men were carrying flags, or poles surmounted by golden emblems and wreaths, such as were borne in Roman triumphs; others, again, carried small trees decorated with garlands and crowns, resplendent with lighted candles and leaves of tinsel, like Christmas trees. Large plates of gilded copper, raised on poles and covered with embossed ornaments and inscriptions, reflected here and there the brilliance of the lights. Next walked the singers (awalim) and the dancers (ghawazi), dressed in striped silk dresses, their tarbouch (a rimless hat with a flat, circular crown) capped with a gold tassel, their long braids streaming with sequins. Some had their noses pierced with long rings, and showed faces painted red and blue, while others, though singing and dancing, remained carefully veiled. They were generally accompanied by cymbals, castanets, and snare drums. Two long lines of slaves came next, carrying chests and baskets in which gleamed the presents given to the bride by her husband and her family; then the procession of guests, the women in the middle, carefully draped in their long black mantillas and veiled with white masks, like people of quality; the men richly dressed; for, on that day, the dragoman told me, even the simple fellahin (labourers) know how to procure suitable clothing. At last, amidst the dazzling light of torches, candelabras and fire-pots, the crimson phantom I had already glimpsed slowly advanced, that is to say the new bride (el arous), entirely veiled in a long cashmere dress the folds of which fell to her feet, and whose rather flimsy material doubtless allowed her to see without being seen. Nothing is as strange as this tall figure advancing beneath its sharply-pleated veil, magnified still further by a sort of dazzling, jewelled, pyramidal diadem. Two matrons dressed in black support her under the elbows, so that she seems to slide slowly along the ground; four slaves stretch a purple canopy over her head, and others accompany her progress to the sound of cymbals and tympani.

However, a further halt was made, at the moment when I was admiring her apparel, and children distributed seats so that the wife and her parents could rest. The awalim, retracing their steps, sounded out their improvisations and choruses, accompanied by music and dancing, and all the assistants repeated some passages of their songs. As for me, who at that moment found myself visible to all, I opened my mouth like the others, imitating as much as possible the eleisons or amens which serve as responses to the most profane couplets; but a greater danger threatened my incognito. I had failed to notice that, for some time, slaves had been traversing the crowd pouring a clear liquid into small cups which they distributed as they went. A tall Egyptian dressed in red, who was probably a member of the family, presided over the distribution and received the thanks of the drinkers. He was only two steps from me, and I had no idea what words of greeting I should address to him. Fortunately, I had taken the time to observe all my neighbours’ movements, and, when it was my turn, I took the cup in my left hand and bowed, placing my right hand to my heart, to my forehead, and finally to my mouth. The movements are easy, yet one must be careful not to reverse the order or fail to reproduce them with ease. I had the right, from that moment, to swallow the contents of the cup; but, then, my surprise was great. It was brandy, or rather a kind of anisette. I had not anticipated that Muslims would distribute such liquor at their weddings? In fact, I had only expected a lemonade or a sorbet. It was, however, easy to see that the almahs, musicians, and minstrels of the procession had more than once taken part in these distributions. At last, the bride rose and resumed her walk; the female fellahin dressed in blue, followed her in a crowd clucking wildly, and the procession continued its nocturnal promenade to the house of the newly-weds.

Content with having appeared a true inhabitant of Cairo, and behaving well enough at this ceremony, I signalled to summon my dragoman, who had gone a little further, to return to the passage where the brandy distributors stood; but he was in no hurry to do so, having taken a liking to the celebrations.

— ‘Let’s follow them into the house,’ he said, quietly.

— ‘But how will I answer, if someone speaks to me?’

— ‘You must simply say: Tayeb! It’s an answer to everything.... And, besides, I am here to turn the conversation elsewhere.’

I already knew that in Egypt tayeb was the foundation of the language. It is a word which, depending on the intonation you give it, means all sorts of things; however, you cannot compare it to the goddam of the English, unless it’s to mark the difference between a people who are certainly very polite, and a nation that is at most merely civilised. The word tayeb means in turn: very good, or that is fine, or that is perfect, or at your service, the tone and especially the gesture adding infinite nuance. This method seemed to me much safer, moreover, than that of which a famous traveller speaks; Giovanni Belzoni, I believe. He had entered a mosque, admirably disguised and, repeated all the gestures that he saw his neighbours make; but, as he could not answer a question that was put to him, his dragoman said to the curious: ‘He does not understand: he is an English Turk!’

We entered, via a door decorated with flowers and foliage, a most beautiful courtyard illuminated by coloured lanterns. The frail woodwork of the moucharabias was outlined against the orange background of rooms, well-lit, and full of people. We were forced to halt, and find a place under the interior arcade. Only the women went into the house, where they took off their veils, and one could no longer see anything but the vague shape, the colours, and radiance of their costumes and jewellery, through the turned-wood lattice.

While the ladies were being welcomed, and feted within by the new wife and the women of the two families, the husband had dismounted from his donkey; dressed in a red and gold coat, he received the compliments of the men, and invited them to take their places at low tables set in great numbers in the rooms on the ground floor, which were laden with dishes arranged in pyramids. All that was needed was to cross one’s legs on the ground, pull a plate or cup towards oneself, and eat in a proper manner, with one’s fingers. Everyone, moreover, was welcome. I did not dare risk, however, participating in the feast, for fear of seeming ill-mannered. Besides, the most brilliant part of the festival was taking place in the courtyard, where the dancing was going on to great noise. A troupe of Nubian dancers were performing strange steps in the centre of a vast circle formed by the assistants; they came and went, guided by a veiled woman dressed in a broadly-striped cloak, who, holding a curved sabre in her hand, seemed to alternately threaten the dancers and flee from them. During this time, the awalim, or almahs, accompanied the dance with their songs by striking with their fingers on terracotta goblet-shaped drums (darbukalar) held in the hand at ear-height. The orchestra, composed of a host of bizarre instruments, did not fail to play its part in this ensemble, and the assistants joined in, also, by beating time with their hands. In the intervals between the dances, refreshments were circulated, among which there was one that I had not anticipated. Black Africans, holding small silver flasks in their hands, shook them here and there over the crowd. It was perfumed water, the sweet scent of which I only recognised when I felt the drops, scattered at random, trickle down my cheeks and beard.

Moreover, one of the most prominent characters of the wedding party advanced towards me and said a few words to me in a very civil manner; I replied with the all-conquering tayeb, which seemed to satisfy him fully; he addressed my neighbours, and I was able to ask the dragoman what he had said.

— ‘He invites you to enter his house’, the latter said, ‘to view the bride’.

Without a doubt, my answer had been deemed an assent; but, as, after all, it was only a question of a parade of hermetically-veiled women around rooms filled with guests, I did not think it appropriate to take the adventure further. It is true that the bride and her friends would appear in their brilliant costumes that were hidden by the black veil they had worn in the street; but I was not yet sufficiently sure of the pronunciation of the word tayeb to venture into the bosom of the two families. The dragoman and I managed to regain the outer door, which opened onto Esbekieh Square.

‘That’s a shame,’ the dragoman said, ‘you would have seen the performance afterwards.’

— ‘What?’

— ‘Yes, the comedy.’

I immediately thought of the illustrious Karagöz (an obscene marionette of Turkish origin), but that was not it. Karagöz only appears during religious festivals; it is a myth, a symbol of the highest gravity; the spectacle in question, here, would simply consist of small comic scenes played by men, and which can be compared to our ‘society proverbs’ (dialogues, illustrating proverbs, performed in a social setting, for example those of Louis Carrogis, known as Carmontelle, or those of Théodore Leclercq). They are designed to entertain the guests, pleasantly, for the remainder of the night, while the spouses retire with their parents to the part of the house reserved for women.

It seems that the festivities of this wedding had already lasted eight days. The dragoman informed me that there had been, on the day of the contract, a sacrifice of sheep on the threshold before the passage of the bride; he also spoke of another ceremony in which a candied ball is broken open which contains two pigeons; an omen is drawn from the flight of these birds. All these customs are probably connected with ancient tradition.

I returned to my lodgings, quite moved by this nocturnal scene. Here, it seemed to me, is a people for whom marriage is a great thing, and, although the details of this one indicated some wealth between the spouses’ families, it appears that the poor marry with almost as much splendour and noise. They are not required to pay the musicians, jesters and dancers, who are their friends, or who take a collection among the crowd. The costumes are lent to them; each assistant holds his candle or his torch in his hand, and the bride’s diadem is no less loaded with diamonds and rubies than that of a Pasha’s daughter. Where else can one seek truer equality? The young Egyptian, who is perhaps neither beautiful beneath her veil, nor rich beneath her diamonds, has her day of glory on which she advances, radiantly, through the city, which shows its admiration, and sees her parade, displaying the purple robes and gems of a queen, yet unknown to all, and as mysterious beneath her veil as the ancient goddess of the Nile. One man alone, will possess the secret of this beauty, or this unknown grace; one alone can pursue his ideal in peace all day long, and believe himself the favourite of a Sultana or a fey; even a disappointment leaves his self-esteem intact; and, besides, does not every man have the right, in this happy country, to re-enact that day of triumph and illusion more than once?

Chapter 3: Abdallah, the Dragoman

My dragoman is a valuable fellow; but I fear he is too noble a servant for so minor a lord as myself. It was at Alexandria, on the deck of the steamship Leonidas, that he was revealed to me in all his glory. He had come alongside the ship, a boat at his command, with a little black African servant to carry his long pipe and a younger dragoman to act as retinue. A long white tunic covered his clothes and brought out the hue of his face, where Nubian blood tinted a mask borrowed from the Egyptian Sphinx’s; he was doubtless the product of a mixed inheritance; large gold rings burdened his ears, and his indolent walk in his long clothes completed the ideal portrait of a freedman of the Late Empire.

There were no Englishmen among the passengers; our man, a little annoyed, attached himself to me for want of anyone better. We disembarked; he hired four donkeys for himself, for his retinue and for me, and took me straight to the Hotel d’Angleterre, where they were willing to receive me for sixty piastres a day; as for himself, he limited his claim to half this sum, out of which he undertook to maintain the second dragoman, and the little black African boy.

After walking all day with this imposing escort, I became aware of the redundant nature of the second dragoman, and even of the little lad. Abdallah (that was the character’s name) had no difficulty in parting with his young colleague; as for the little black African boy, he kept him at his own expense, reducing the total of his own fee to twenty piastres a day, about five francs.

Arriving in Cairo, the donkeys took us straight to the Hotel d’Angleterre on Esbekieh Square; I restrained his fine ardour on learning that the terms for staying there were the same as in Alexandria.

— ‘Would you prefer to try the Waghorn Hotel, in the Frankish quarter?’ honest Abdallah asked me.

— ‘I’d prefer a hotel that wasn’t English’.

— ‘Well, there’s Demergue’s French Hotel.’

— ‘Then, let’s go.’

— ‘Pardon me, I’ll take you there; but I won’t stay there.’

— ‘Why not?’

— ‘Because they only charge forty piastres per day; I can’t stay there.’

— ‘But it’s fine for me.’

— ‘You are unknown; I’m from the city; I usually serve the English; I have my status to maintain.’

However, I considered the price of the hotel most reasonable, even in a country where everything is about six times cheaper than in France, and where a man for a day costs a piastre, or five sous in our currency.

‘There is,’ said Abdallah, ‘a way of arranging matters. You will lodge two or three days at the Domergue Hotel, where I will visit you, as a friend; meanwhile, I’ll rent a house in the city for you, and shall then be able to stay there, and be at your service, without difficulty.’

It seems that many Europeans rent houses in Cairo, if they are dwelling there, and, informed of this circumstance, I granted Abdallah full authority to do so.

The Domergue Hotel is located at the end of a cul-de-sac, off the main street of the Frankish quarter; it is, all things being equal, a very decent and well-kept hotel. The buildings surround a square courtyard painted with limewash, covered with an airy trellis, on which vines are intertwined; a French painter, most amiable though a little deaf, and very talented though keen on the daguerreotype process, has made a studio of an upper gallery. There, from time to time, he brings orange-sellers and sugar-cane sellers from the city who are willing to serve as models for him. They make no difficulty over allowing the physical form of the principal Egyptian types to be studied; but most of them insist on keeping their faces veiled; the last refuge of oriental modesty.

The French hotel has, moreover, a rather pleasant garden; its table d’hôte successfully avoids the difficulty of obtaining various European dishes in a city where beef and veal are lacking. It is this circumstance which mainly explains the high cost of the English hotels, in which the cooking is done with preserved meats and vegetables, as it is on board ship. The Englishman, in whatever country he may be, never changes his usual fare of roast-beef, potatoes, and porter or ale.

I met at the table d’hôte a colonel, a bishop in partibus (that is, in the land of the unbelievers), an artist, a language-teacher, and two Indians from Bombay, one of whom served as tutor to the other. It seems that the host’s very southern cooking seemed bland to them, since they took from their pockets silver flasks containing pepper and mustard for their own use, with which they anointed all their dishes. They offered me some. The sensation one would surely experience in chewing on lighted embers would give an exact idea of the strong effect of those condiments.

You may complete the picture of residency at the French Hotel by envisaging a piano on the first floor and a billiard-table on the ground floor, and say to oneself that one has as good as not left Marseilles at all. I prefer, for my part, to sample oriental life complete. I rent a most beautiful house with several floors, and with courtyards and gardens, for three hundred piastres (approximately seventy-five francs) per annum, Abdallah having shown me several in the Coptic quarter and the Greek quarter. The rooms were magnificently decorated with marble paving, and fountains, galleries, and staircases as in the palazzos of Genoa or Venice, courtyards surrounded by columns, and gardens shaded by valuable trees; sufficient to lead the life of a prince, on the condition of one populating those superb interiors with servants and slaves. Yet in all this, however, not a habitable room without going to enormous expense, not a pane of glass in those windows, so curiously shaped, open to the evening wind and the nights’ humidity. Men and women live thus in Cairo; but ophthalmia often punishes them for their imprudence, which explains the need for air and freshness. In the end, I was somewhat dubious of the pleasure of living camped, so to speak, in a corner of an immense palace; it must also be said that many of these buildings, former residences of an extinct aristocracy, date back to the days of the Mamluk Sultans, and are in danger of serious collapse.

Abdallah, ultimately, found me a much smaller house, but safer, and more thoroughly secure. An Englishman, who had recently lived there, had installed glazed windows, and this was considered a curiosity. I had to obtain the aid of the sheikh of that district to deal with a Coptic widow, who was the owner. This lady owned more than twenty houses, but by proxy, on behalf of foreigners, the latter not being permitted to be legal owners in Egypt. In reality, the house belonged to a diplomat at the English consulate.

The deed was drawn up in Arabic; it was necessary to pay a fee, make presents to the sheikh, to the lawyer, and to the head of the nearest guardhouse, and then to give the scribes and servants bakshish (tips); after which, the sheikh handed me the key. This instrument does not resemble ours but is composed of a simple piece of wood similar to a baker’s tally, at the end of which five or six nails are planted as if at random; though chance is not involved: one introduces this singular key into a notch in the door, and the nails are found to correspond to small internal and invisible holes beyond which hangs a moveable wooden bolt which allows passage.

It is not enough to have the wooden key to one’s house ... a key which it is impossible to place in one’s pocket, but which one can slip into one’s belt: one must also have furniture corresponding to the luxury of the interior; but this detail is, for all the houses of Cairo, of the greatest simplicity. Abdallah took me to a bazaar where they weighed out for me a few ocques of cotton (an ‘ocque’ weighed a little less than three pounds); with this and some Persian cloth, carders established at your house, will make, in a few hours, divan cushions, which become, at night, mattresses. The body of each piece of furniture is composed of a large frame that a basket maker constructs with palm fronds, before one’s eyes; it is light, elastic and stronger than one would believe. With a small round table, a few cups, long pipes or hookahs, unless one wants to borrow all that from the neighbouring café, one can receive the noblest of city society. The Pasha alone has a complete set of furniture, lamps, and clocks; but, in reality, this is only to show himself a friend to European trade and progress.

Mats, carpets, and even curtains are still needed for those who want to display luxury. I met a Jewish person in the bazaar who, most obligingly, interposed himself between Abdallah and the tradesmen, so as to prove to me that I was being robbed on both sides. He took advantage of the furniture being installed to settle himself down, as a friend, on one of the sofas; I was obliged to hand him a pipe, and have coffee served to him. His name is Yousef, and he devotes himself to raising silkworms for three months of the year. The rest of the time, he told me, he has no other occupation than to view the leaves of the mulberry trees to make sure they are growing, and see if the harvest will be good. He seems, moreover, perfectly disinterested, and seeks the company of foreigners only to inform his taste, and strengthen his knowledge of the French language.

My house is located on a street in the Coptic quarter which leads to the city gate, connecting with the alleyways of Shubra. There is a café opposite, a little further a donkey station, which rents the animals at a piastre an hour; further still, a small mosque accompanied by a minaret. The first evening that I heard the slow and serene voice of the muezzin (mu’adhin), at sunset, I felt seized by an inexpressible melancholy.

— ‘What does he say?’ I asked the dragoman.

— ‘Alla ilaha illa-llah… there is no other God but Allah!’

— ‘I know that formula; and then?’

— ‘Oh: you, who are about to sleep, commend your souls to Him who never sleeps!’

It is true that sleep is another life, which must be taken into account. Since my arrival in Cairo, all the stories of the Thousand and One Nights have been running through my head, and I see in my dreams all the genies and giants unleashed since Solomon. In France, people scorn, laughingly, the demons that sleep gives birth to, and recognise in them only the product of an intense imagination; but is sleep a lesser state in relation to us, and do we not experience in that state all the sensations of real life? Sleep is often heavy and troubling in a climate as hot as that of Egypt, and the Pasha, it is said, always has a servant standing at his bedside to wake him from sleep whenever his movements or his face betray restlessness. So, it suffices perhaps to simply recommend oneself, with fervour and confidence ... to the One who never sleeps!

Chapter 4: The Disadvantages of Celibacy

I have related the history of my first night, above, and it is understandable then that I awoke somewhat late. Abdallah announced to me the visit of the sheikh of my neighbourhood, who had already visited once in the morning. This fine white-bearded old man was waiting in the cafe opposite, along with his secretary and the black African boy bearing his pipe, for me to awake. I was not surprised at his patience; any European who is neither an industrialist nor a merchant is a character in Egypt. The sheikh sat down on one of the sofas; his pipe was filled, and he was served coffee. Then he began his speech, which Abdallah translated for me as follows:

— ‘He comes to bring you the money you paid to rent the house’.

— ‘Why? What reason does he give?’

— ‘He says: we don’t know your way of life, we’ve no knowledge of your morals.’

— ‘Has he observed that they are bad?’

— ‘That’s not what he means; he knows nothing about them.’

— ‘And yet, he holds a poor opinion of them?’

— ‘He says he thought a woman would live with you in the house.’

— ‘But I’m not married.’

— ‘It’s none of his business whether you are or not; but he says your neighbours have wives, and will be anxious if you do not. Besides, it is the custom here.’

— ‘What does he wish me to do?’

— ‘Quit the house, or find a woman to live with you.’

— ‘Tell him that, in my country, it is not right to live with a woman without being married.’

The old man’s reply to this moral observation was accompanied by a very paternal expression which the translation can only render imperfectly.

— ‘He offers you a little advice’, Abdallah told me: ‘he says that a gentleman (an effendi) like you should not live alone, and that it is always honourable to support a woman, and do her some good. It is even better, he adds, to support several, when the religion one follows permits it.’

The Turk’s reasoning touched me; however my European conscience struggled with his point of view, the justice of which I only understood after studying more closely the situation of women in this country. I communicated a reply for the sheikh, asking him to wait until I had inquired from my friends what it would be appropriate to do.

I had rented the house for six months, I had furnished it, I was very comfortable there, and I only wanted to find out how to resist the sheikh’s pretension to the breaking of our treaty, and to his demanding I leave on grounds of celibacy. After much hesitation, I decided to take advice from the artist residing at the Hotel Domergue, who had already been kind enough to introduce me to his studio, and initiate me into the wonders of the daguerreotype. The artist was so deaf that a conversation through an interpreter would have been amusing, though probably at the cost of his own hearing.

However, I was on my way to his house, and crossing Esbekieh Square, when at the corner of a street that turns towards the Frankish quarter, I heard exclamations of joy rising from a large courtyard where some very fine horses were, at that moment, being walked. One of the grooms sprang upon my neck and hugged me; he was a big lad dressed in blue woollen serge, wearing a yellowish woollen turban, and whom I remembered having noticed on the steamship, because of his face, which was very reminiscent of those large painted heads that one sees on the lids of mummies’ coffins.

— Tayeb! Tayeb! (Fine! Fine!) I said to this expansive mortal, freeing myself from his embraces and looking behind me to locate my dragoman, Abdallah.

But the latter had lost himself in the crowd, probably not caring to be seen accompanying the friend of a simple groom. This Muslim, spoiled by chaperoning tourists from England, forget that Muhammad was once a camel driver.

Meanwhile the Egyptian plucked me by the sleeve and led me into the courtyard, which belonged to the Pasha of Egypt’s stud farm, and there, at the back of an arcade, half lying on a wooden sofa, I recognised another of my travelling companions, a little more respectable socially: Soliman-Aga, of whom I have already spoken, and whom I’d met on the Austrian boat, the Francisco Primo. Soliman-Aga also recognised me, and, though more restrained in his demonstrations than his subordinate, he made me sit near him, offered me a pipe and asked for coffee.... Let me add, that the simple groom, as a point of manners, judging himself momentarily worthy of our company, sat down with his legs crossed on the ground and accepted, as I, a long pipe, and one of those small cups full of a hot mocha that one holds in a sort of gilded egg-cup so as not to burn one’s fingers. A circle soon formed around us.

Abdallah, seeing the situation take a more fitting turn, had finally shown himself, and deigned to favour our conversation. I already knew Soliman-Aga to be a very amiable guest, and, although we had achieved, during our mutual sea-crossing, only a pantomime conversation, our acquaintance was sufficiently advanced for me to be able, without indiscretion, to discuss my affairs with him and ask his advice.

— ‘Mashallah!’ (‘As Allah has willed it’) he cried, at first, ‘the sheikh is quite right; a young man of your age should have already married several times!’

— ‘You know,’ I observed timidly, ‘that in my religion one can only marry one woman at a time, and then one must support her forever, so that ordinarily one takes time to think, wishing to choose the most suitable.’

— ‘Ah! I am not speaking,’ he said, striking his forehead, ‘of your Roumi (European) women; they belong to all, not only to you; those poor foolish creatures show their faces entirely naked, not only to those who wish to see them, but to those who do not.... imagine,’ he added, bursting into laughter and turning towards the other Turks who were listening ‘every woman, in the street, gazed at me with eyes of passion, and some even pushed their shamelessness to the point of wanting to kiss me.’

Seeing the audience scandalised to the utmost degree, I believed I ought to inform them, for the honour of us Europeans, that Soliman-Aga had doubtless confused the interested eagerness of certain women with the honest curiosity of the majority.

— ‘Again,’ added Soliman-Aga, without replying to my observation, which seemed dictated only by national self-esteem, ‘if only these beauties were worthy of kissing a believer’s hand! But they are wintry plants, without colour or taste, sickly figures tormented by famine, for they hardly eat, and their bodies would fit within my two hands. As for marrying them, that’s another thing; they have been raised so badly, that there would be war and unhappiness in the house. With us, the women live together, and the men live together, it is the means of establishing tranquility everywhere.’

— ‘But do you not live,’ I said, ‘among your women in your harems?’

— ‘Lord above!’ he cried, ‘who would not be maddened by their babbling? Do you not see that, here, men who have nothing to do spend the time walking, bathing, at the café, at the mosque, as members of an audience, or in visits made to one another? Is it not more pleasant to talk with friends, or to listen to stories and poems, or to smoke while dreaming, than to talk to women preoccupied with vulgar interests, fashion, or slander?

— ‘But of necessity, you must accept this when you take your meals with them.’

— ‘Not at all. They eat together, or separately, at their choice, and we eat alone, or with our parents and friends. A small number of the faithful do act otherwise, but they are ill-regarded and lead a cowardly and useless life. The company of women makes men greedy, selfish and cruel; it destroys fraternity, and charity among us; it causes quarrels, injustice and tyranny. Let each live with his fellows! It is enough that the master, at the hour of the siesta, or when he returns in the evening to his lodging, finds to receive him smiling faces, amiable forms richly adorned,... and if the almahs who are brought in dance and sing before him, then he can dream of paradise in advance, and believe himself to be in the third heaven, where the true beauties dwell, pure and unblemished, those who alone will be worthy of being the eternal spouses of true believers.’

Is this the opinion of all Muslims, or only of a certain number of them? One might perhaps see in it less a contempt for women than a remnant of ancient Platonism, which elevates pure love above perishable objects. The adored woman is herself only the abstract phantom, the incomplete image of a divine woman, betrothed to the believer for all eternity. It is these ideas which led us to think that Orientals deny women a soul; but we know, these days, that truly pious Muslim women hope themselves to see their ideal realised in heaven. The religious history of the Arabs has its saints and its prophetesses, and the daughter of Muhammad, the illustrious Fatima, is the queen of this feminine paradise.

Soliman Aga finally advised me to embrace Islam; I thanked him with a smile and promised to consider it. At this, I was more embarrassed than ever. However, it remained for me to visit, and consult, the deaf painter at the Hôtel Domergue, as I had originally intended.

Chapter 5: El Mosky

When one turns the corner, leaving the stud farm’s courtyard on your left, one begins to feel the bustle of a big city. The roadway that encircles Esbekieh Square possesses only a meagre avenue of trees to protect you from the sun; but already, on one side of the street, broad, tall stone houses block the dusty rays it projects. The place is usually very crowded, noisy, populated by sellers of oranges, bananas, and still-green sugar cane, whose sweet pulp the people chew with delight. There are also singers, wrestlers, and snake-charmers who have large serpents wrapped around their necks; also, occurrences of a spectacle which realises certain images of Rabelais’ droll fantasies. A jovial old man makes small figures, their bodies traversed by a string, dance on his knee, like those shown by our Savoyards, but engaging in a much less decent pantomime. However, this is not the illustrious Karagöz, who usually only appears in a Chinese shadow-theatre performance. A wondering circle of women, children and soldiers naively applauds these shameless puppets. Elsewhere, it is a monkey-trainer who has taught an enormous ape to counter, with a stick, the attacks of the city’s stray dogs, which the children incite to battle. Further on, the street narrows, and darkens due to the height of the buildings. Here on the left is a convent of whirling dervishes, who perform a public session every Tuesday; then a large carriage entrance, above which one may admire a large stuffed crocodile, signals the station from which the carriages leave that cross the desert from Cairo to Suez. These are light vehicles, whose prosaic shape recalls that of a cuckoo-clock, the wide openings giving passage to the wind and dust, which is no doubt necessary; their iron wheels have a dual system of spokes, starting from each side of the hub and meeting at the narrow circle which replaces the rim. These singular wheels cut the ground rather than resting on it.

But let us move on. Here on the right is a Christian tavern, that is to say a vast cellar where drinks are served on barrel-heads. Usually, a mortal with an illuminated face and long moustache, stands before the door, who majestically represents the native Franks, or those, to put it better, who belong to the Orient. Who knows if he is Maltese, Italian, Spanish or Marseillais by origin? What is certain is that his disdain for the costume of the country, and his awareness of the superiority of European fashions have led him to refinements of dress which grant a certain originality to his dilapidated wardrobe. To a blue frock-coat whose frayed loops have long since parted from their buttons, he has had the idea of attaching loops of cord to imitate frogging. His red trousers fit into the remnants of thick boots armed with spurs. A wide shirt-collar and a white hat with green turn-ups soften what is too martial in this costume, and restore its civilian character. As for the truncheon he holds in his hand, it is still a privilege of the Franks and Turks, which is too often exercised at the expense of the shoulders of the poor and patient fellahin.

Almost opposite the tavern, the eye plunges into a narrow alley where a beggar lacking hands and feet crawls; this poor devil begs charity of the English, who pass at every moment, for the Waghorn Hotel is situated in this dark alley, which, moreover, leads to the Cairo theatre and to the reading room of Monsieur Bonhomme, announced by a vast sign painted in French lettering. All the pleasures of civilisation are evident there, and cannot but rouse great envy in the Arabs. Resuming one’s progress, one finds, on the left, a house with an architectural facade, sculpted and adorned with painted arabesques, the sole offering, seen so far, to the artist and the poet. Then the street bends away, and one must struggle for twenty paces against a perpetual crowd of donkeys, dogs, camels, cucumber-sellers, and women selling bread. Donkeys gallop, camels bellow, dogs stand stubbornly in rows at the doors its three butchers. This little corner would not lack an Arabian physiognomy, if one did not see in front of one the sign denoting a trattoria filled with Italians and Maltese.

Here before us, in all its luxury, is the great shopping street of the Frankish quarter, commonly called the Mosky. The first section, half covered with canvas and boarding, presents two rows of well-stocked shops, in which the European nations exhibit their best-known products. England dominates as regards fabrics and crockery; Germany, sheets; France, fashions; Marseilles, groceries, smoked meats and small assorted objects. I do not include Marseilles with France, because, in the Levant, one does not take long to realise that the Marseillais form a ‘nation’ apart; granting the word its most favourable sense, moreover.

Among these shops, where European industry at its best attracts the richest inhabitants of Cairo, the reformist Turks, as well as the Copts and Greeks more readily attuned to our habits, there is an English bar-restaurant where one can counteract, with the help of Madeira, porter, or ale, the sometimes-emollient action of the waters of the Nile. Another place of refuge from oriental life is the Castagnol pharmacy, where often the beys (gentlemen), mudirs (officers) and nazirs (officials) originating from Paris come to converse with travellers, and find some token of the homeland. One is not surprised to see the chairs of the pharmacy, and even the outside benches, filled with dubious Orientals, their chests covered with gleaming stars, who converse in French and read the newspapers, while the sais (grooms) keep ready at their disposal dashing horses, the saddles embroidered with gilt. This gathering is also explained by the proximity of the Frankish post office, located in the cul-de-sac that contains the Domergue Hotel. People attend every day, awaiting letters and journals, which arrive from time to time, depending on the state of the roads or the diligence of the messengers. The English steamboat only ascends the Nile once a month.

I am near the end of my journey, for at the Castagnol pharmacy I encounter my artist from the French hotel, who is waiting for gold chloride, used for toning his daguerreotypes, to be prepared. He suggests that I go with him to view the city; so, I dispense with the dragoman, who hastens to settle down in the English brasserie, having gained, I fear, from contact with his previous masters, an immoderate taste for strong beer and whiskey.

In accepting the proposed walk, I thought of a better idea still: it was to allow myself to be led to the most complex part of the city, abandon the artist to his labours, and then wander at random, without an interpreter, and without a companion. This is what I had not been able to achieve until then, the dragoman claiming to be indispensable, and all the Europeans I had met proposing to show me ‘the beauties of the city.’ One must have travelled in the South a little to understand the full scope of their hypocritical proposal. Do you think the amiable resident offers to be your guide from mere goodness of soul? Think again; he has nothing to do, he is dreadfully bored, he needs you to amuse him, to distract him, to ‘make conversation with him’, but he will show you nothing you would not have discovered yourself: he doesn’t even know the city, and has no idea of what goes on there; his aim is to take a walk, bore you with his remarks, and amuse himself with yours. Besides, what is a beautiful perspective, a monument, a curious detail, without chance, without the unexpected?

A prejudice of the Europeans in Cairo is that they cannot walk ten steps without mounting a donkey escorted by a donkey-driver. The donkeys are very beautiful, I agree, they trot and gallop wonderfully; the donkey driver serves as your kavasse (guardian) and makes the crowd part by shouting: Ha! ha! Yeminac! Smalac! which means: ‘To the right! To the left!’ Since women have thicker ears or heads than other passers-by, the donkey driver shouts at every moment: Ia bint! (Hey, girl!) in an imperious tone intended to convey, clearly, the superiority of the male sex.

Chapter 6: An Adventure in the Besestain Bazaar

We rode along like this, the artist and I, followed by a donkey which carried the daguerreotype, a complicated and fragile machine that it was a matter of establishing somewhere in such a way as to do us honour. After the street I have described, one comes to a covered and boarded passageway, where European trade displays its most brilliant products. It is a sort of market where the Frankish quarter ends. We turned right, then left, in the midst of an ever-increasing crowd; we followed a long, very straight street, which offers to one’s curiosity, from time to time, mosques, fountains, a convent of dervishes, and a whole bazaar of hardware and English porcelain. Then, after a thousand detours, the road becomes quieter, more dusty, more deserted; the mosques are falling to ruin, the houses collapsing here and there, the noise and the tumult no longer register except in the form of a band of howling dogs, determined to chase our donkeys, and especially to pursue our hideous black European clothes. Fortunately, we pass beneath a gate, thus moving from one quarter to another, and the animals cease their growling at the extreme limit of their domain. The whole city is divided into fifty-three quarters surrounded by walls, various of which belong to the Coptic, Greek, Turkish, Jewish, and French inhabitants. The dogs themselves, swarming peaceably about the city without belonging to anyone, recognise these divisions, and would not risk venturing beyond them. A new canine escort soon replaces the one which has quit us, and leads us to the casinos situated on the bank of a canal which traverses Cairo, and which is called the Calish (the Amnis Trajanus).

Here we are in a kind of suburb separated from the main districts of the city by the canal; numerous cafes and casinos line the inner bank, while the outer presents a wide boulevard adorned with a few dusty palm-trees. The water of the canal is green and somewhat stagnant; but a long series of arches and trellises festooned with vines and creepers, serving as a backcloth for the cafes, presents a most cheerful view, while the flat water which surrounds them pleasantly reflects the colourful costumes of the smokers. Oil-flask lanterns alone light the day, glass hookahs gleam, and amber liquor swims in the fragile cups that black African waiters distribute from their gilt-filigreed containers.

After a short halt at one of these cafes, we transported ourselves to the far bank of the Calish, and set up, on legs, the apparatus by means of which the god of daylight exercises, so agreeably, the profession of landscape-artist. A ruined mosque with a curiously carved minaret, a slender palm-tree springing from a grove of mastic trees, was, with all the rest, enough to compose a picture worthy of the artist Prosper Marilhat. My companion is in raptures, and, while the sun works on his freshly-toned plates, I thought to begin an instructive conversation, by making him answer in pencil those questions which his infirmity did not prevent him from answering orally.

— ‘Don’t marry’ he cried, ‘and above all don’t adopt the turban. What do they seek? That you take a wife into your house. A fine affair! One can have as many women as one wants. Those orange-sellers in blue tunics, adorned with silver bracelets and necklaces, are very beautiful. They take the very shape of Egyptian statues, with a well-developed chest, superb shoulders and arms, a slightly protruding hip, and thin, lean legs. It’s live archaeology; all they lack is a hawk’s head, bandages round their bodies, and an ankh in their hand, to represent Isis or Hathor.’

— ‘But you forget,’ I said, ‘that I am no artist; and, besides, these women have husbands or families. They are veiled: how can one know if they are beautiful?... I know only one word of Arabic, as yet. How can one persuade them?’

— ‘Dalliance is strictly forbidden in Cairo; but nowhere is love forbidden. You meet a woman whose gait, whose figure, whose grace in draping her clothes, something careless in the veil or hairstyle, indicates youth, or the desire to appear amiable. Just follow her, and if she looks you in the face at a moment when she thinks herself unnoticed by the crowd, take the road to your house; she will follow you. In matters regarding women, trust only yourself. The dragoman would serve you badly. You must pay your respects in person, it is safer.’

— ‘And, truly,’ I said to myself as I quit the painter, leaving him to his work, surrounded by a respectful crowd who believed him to be employed in some magical endeavour; ‘why have I relinquished hope of pleasing? The women are veiled; but I am not. My European complexion may have some charm for the women of this country. In France I would pass for an ordinary fellow; but in Cairo I am transformed into an amiable child of the North. This Frankish costume, which rouses the dogs, at least earns me some notice; that is much.’

Indeed, having entered the crowded street, and now pushing my way through the crowd all astonished to see a Frank on foot, and without a guide, in the Arab part of the city, I stopped in the doorways of shops and workshops, examining everything with the air of an inoffensive idler, which merely raised a few smiles. Saying to one another: ‘He has lost his dragoman, or perhaps he lacks the money to take a donkey...’ they pitied the foreigner astray in the immense hubbub of the bazaar, in the labyrinth of the streets. As for me, I had stopped to watch three blacksmiths at work who seemed men of bronze. They were singing an Arabic song whose rhythm guided the successive blows they gave to pieces of metal that a child brought in turn to the anvil. I shuddered to think that if one of them had missed the measure by half a beat, the child would have had his hand crushed. Two women had stopped behind me, and were laughing at my curiosity. I turned around, and saw clearly, by their black taffeta mantillas, and their green Levantine coats, that they did not belong to the class of the orange-sellers of Mosky. I turned to meet them, but they lowered their veils and escaped. I followed them, and soon arrived in a long street, interspersed with rich stalls, which crossed the whole city. We entered a vault of grandiose appearance, formed of carved frames in an antique style, varnish and gilding enhancing a thousand details of their splendid arabesques. This is perhaps the Besestain of the Circassians, in which the story told by the Coptic merchant to the Sultan of Kashgar took place. Here I am in the midst of the Thousand and One Nights. Why am I not one of the young merchants before whom these two ladies are leafing through rolls of cloth, as did the daughter of the emir before Bedreddin’s shop! I would say to them like the young man of Baghdad: ‘Let me view your face as the price of this golden-flowered fabric, and I will be paid with interest!’ But they disdain the silks of Beirut, the brocaded fabrics of Damascus, and the mantillas from Brousse (Bursa, in Turkey, a major centre of the silk trade) which each seller displays at will.... There are no shops here: they are simple stalls whose shelves rise to the vault above, surmounted by a sign covered with letters and gilded emblems. The merchant, his legs crossed, smokes his long pipe or his hookah on a narrow platform, and the women go thus from merchant to merchant, contenting themselves, after having looked at everything on one stall, with passing on to another, while granting it a disdainful glance.

My smiling beauties absolutely long for fabrics from Constantinople. Constantinople sets the fashion in Cairo. They are shown hideous printed muslins, to a cry of: Istamboldan (it’s from Istanbul)! They exclaim, in admiration. Fashionable women are the same everywhere.

I approach with an air of connoisseurship; I raise a corner of yellow fabric with wine-red patterns, and exclaim: Tayeb (Fine)! My observation seems to please; I make this my choice. The merchant employs a sort of tape-measure which is called a pick, and a little boy is charged with carrying the roll of fabric.

At this, it appeared to me that one of the young ladies looked me in the face; moreover, their uncertain steps, the laughter they stifled as they turned around, and saw me following them, the black mantilla (habirah) lifted from time to time to reveal a white mask, a sign of the superior class, finally all those indecisive allurements that a domino who wants to seduce you displays at the Opéra ball, seemed to indicate to me that she did not altogether dislike me. It seemed the moment had come, therefore, to forge on, and take the road to my house; but how to find it? In Cairo, the streets have no signs, the houses no numbers, and each district, surrounded by walls, is in itself a complete and utter labyrinth. There are ten cul-de-sacs for every street that leads anywhere. When in doubt, I always follow. We left the bazaar, full of tumult and light, where everything shone and glittered, where the luxury of the displays contrasted with the character of the architecture, and forsook the splendour of the principal mosques, painted with horizontal yellow and red bands; here, now, were vaulted passages, narrow, dark alleys, where the wooden window-trellises overhang, as in our streets in the Middle Ages. The coolness of these almost subterranean ways is a refuge from the heat of the Egyptian sun, and provides the population with many of the advantages of a temperate latitude. This explains the dull whiteness that a large number of women preserve under their veil, because many of them have never left the city except to go and rejoice beneath the shade in Shubra.

But what to think of all the twists and turns I was forced to take? Am I, in reality, being fled from, or are they my guides, while preceding me, on this adventurous journey? However, we entered a street that I had crossed the day before, and which I recognised above all by the charming odour given off by the yellow flowers of a strawberry-tree. This tree, beloved of the sun, projected its branches, covered with perfumed tufts of flower, above the wall. A low fountain occupied a corner, a pious installation intended to quench the thirst of stray animals. Here stood a house of fine appearance, decorated with ornaments, sculpted in plaster; one of the ladies introduced into the door one of those rustic keys of which I had already had experience. I plunged after them into a dark corridor, without hesitating, without thinking, and here I am in a vast and silent courtyard, surrounded by galleries, dominated by the thousand-meshed pattern of the moucharabia.

Chapter 7: A Dangerous House

The ladies having disappeared down some dark staircase at the entrance, I turned around with the serious intent of returning to the door; a tall, robust Abyssinian slave was closing it. I sought for a word to convince him that I was in the wrong house, that I had thought I was heading home; but the word tayeb, universal as it may be, did not seem to me sufficient to express all these things. During this time, a great noise was heard at the rear of the house, and astonished sais emerged from the stables, red caps appeared on the terraces of the first floor, and a most majestic Turk advanced from the back of the main gallery.

At such times, the worst thing is to be too curt. I think that many Muslims understand the Frankish language, which, at root, is only a mixture of all sorts of words from the southern dialects, which one uses randomly until one has made oneself understood; it is the language of Molière’s Turks. So, I gathered up all I might know of Italian, Spanish, Provençal, and Greek, and I composed of it all a very captious speech.

— ‘Besides,’ I said to myself, ‘my intentions are pure; at least one of the women may well be his daughter or his sister. I shall marry, and adopt the turban; well, there are things one cannot avoid. I believe in destiny.’

And then, this Turk looked like a kindly devil, and his well-fed face did not suggest cruelty. He scowled with some malice when he saw me, heaping on me the most baroque nouns that had ever sounded on the bass scale of the Levant, and said to me, holding out towards me a plump hand loaded with rings:

— ‘My dear sir, take the trouble to come this way; we can talk more comfortably.’

Oh, surprise! This brave Turk was a Frenchman like myself!

We entered a very beautiful room whose windows overlooked the garden; we took our places on a rich divan. Coffee and pipes were brought. We talked. I explained as best I could how I had entered his house, believing I was entering one of the many passages that intersect the main islands of houses in Cairo; but I understood from his smile that my beautiful strangers had found time to work my betrayal. This did not prevent our conversation from quickly taking on an intimate character. In Turkish lands, acquaintances are soon made between compatriots. My host was kind enough to invite me to his table, and when the time came, I saw two very beautiful ladies enter, one of whom was his wife, and the other his wife’s sister. They were my strangers from the Circassian bazaar, and both French.... That was the most humiliating thing! They made war on me over my daring to travel through the city without a dragoman, and without a donkey driver; They laughed at my diligent pursuit of two dubious dominoes, which clearly disguised their forms, and might have concealed old women or black Africans. These ladies did not thank me in the least for taking a risk in which none of their charms were involved, because it must be admitted that the black abaya, less attractive than the veil of simple fellahin girls, renders every woman a shapeless package, and, when the wind swells it, gives her the appearance of a half-inflated balloon.

After dinner, served entirely in the French style, I was shown into a much more ornate room, with walls covered with painted porcelain, and with carved cedar cornices. A marble fountain lifted its thin streams of water in the midst; Venetian carpets and mirrors completed the ideal of Arabian luxury; but a surprise that awaited me there soon attracted all my attention. There were eight young girls seated around an oval table, occupied with various labours. They rose, bowed to me, and the two youngest came to kiss my hand, a ceremony which I knew one could not refuse in Cairo. What astonished me most in this seductive apparition was that the complexion of these young people, dressed in oriental style, varied from swarthy to olive, and attained, in the last of them, the darkest chocolate. It would have been inappropriate perhaps to quote in front of the palest one Goethe’s verse:

‘Do you know the land where the lemon-trees grow?’ (Mignon’s song)

However, they would all have passed for beauties of mixed race. The mistress of the house and her sister had taken their places on the sofa, laughing aloud at my admiration. The two little girls brought us liqueurs and coffee.

I was infinitely grateful to my host for having introduced me to his harem; but I said to myself that a Frenchman could never make a good Turk, whose self-esteem at showing off his mistresses or wives must conquer the fear of exposing them to seduction. I was still at fault in the matter. These charming flowers of varied colours were not the women, but the daughters of the house. My host belonged to that military generation which devoted its existence to the service of Napoleon. Rather than recognising themselves as subjects of the Restoration, many of these brave men went to offer their services to the sovereigns of the Orient. India and Egypt welcomed a large number; there were in those two countries fine remnants of French glory. Some adopted the religion and customs of the peoples who gave them asylum. Who could blame them? Most of them, born during the Revolution, had hardly known any cult other than that of the Theophilanthropists (The ‘Friends of God and Man’, a deistic sect) or the Masonic lodges. Islam, in the countries over which it rules, possesses grandeurs which strike even the most sceptical mind. My host had given himself over while still young to the seductions of a new homeland. He had obtained the rank of bey by his talents, and his services; his seraglio had been recruited in part from the beauties of Sennar (on the Nile, in the Sudan). Later, and at a more advanced age, the idea of Europe had returned to mind: he had married the lovely daughter of a consul, and, as Suleiman the Magnificent did on marrying Roxelana, he dismissed his entire seraglio, though the children had remained with him. His girls I now saw; the boys were studying in military schools.

Amidst so many marriageable girls, I felt that the hospitality granted me in this house presented certain dangerous risks, and I did not dare to expose my real situation too much before knowing more.

I was conducted to my house that evening, and won from the whole adventure a most gracious memory.... But, in truth, it would not be worth going to Cairo simply to marry into a French family.

The next day, Abdallah came to ask my permission to accompany a party of Englishmen to Suez. It was a week’s work, and I did not want to deprive him of the lucrative errand. I suspected that he was not very satisfied with my conduct of the day before. A traveller who does without a dragoman all day, who wanders on foot through the streets of Cairo, and then dines who knows where, risks being considered a very odd person. Abdallah introduced to me, moreover, as his stand-in, a barbarian friend of his, named Ibrahim. The barbarian (this is the name given here to common servants) commands only a little of the Maltese patois.

Chapter 8: The Wakil (Envoy)

Yousef, my Jewish acquaintance from the cotton-market, came every day to sit on my couch and perfect his conversation.

— ‘I understand,’ he said to me, ‘that you wish to take a wife, and I’ve found you a wakil.’

— ‘A wakil?’

— ‘Yes, it means an envoy, an ambassador; but, in the present case, an honest man charged with reaching an agreement with the parents of girls to be married. He will bring them to you, or conduct you to them.’

— ‘Oh! But whose are these girls?’

— ‘They are daughters of most honest people, and there are only such people in Cairo, since His Highness relegated the other kind to Esna, a little below the first cataract.’

— ‘I would like to believe it. Well, we shall see; bring me this wakil.’

— ‘I have brought him; he’s downstairs.’

The wakil was a blind man, whom his son, a tall and robust fellow, guided with a most modest air. The four of us mounted a donkey, and I laughed a great deal inwardly as I compared the blind man to Amor, and his son to Hymenaeus the god of marriage. Yousef, heedless of those mythological characters, instructed me as we went.

‘You can marry, here,’ he said to me, ‘in four different ways. The first way is by marrying a Coptic girl before the Turk.’

— ‘Who is this, Turk?’

— ‘He is a virtuous man to whom you give money, who says a prayer, assists you before the cadi (Judge) and fulfils the functions of a priest: these men are saints in this country, and everything they do is well done. They never concern themselves with your religion, if you do not concern yourself with theirs; but such a marriage is not that of very honest girls.’

— ‘Good! Let’s move on to the next method.’

— ‘That’s a serious matter. You are a Christian, and so are the Copts; there are Coptic priests who will marry you, though a schismatic, on condition that you leave a dowry for the wife, in case you divorce later.’

— ‘That’s reasonable; but what dowry?’...

— ‘Oh! That depends on custom. You must always give at least two hundred piastres.’

— ‘Fifty francs! Well, I would marry, and at no great expense.’

— ‘There’s yet another kind of marriage for very scrupulous people; those of good family. You are betrothed before the Coptic priest, he marries you according to his rite, and you can never divorce.’

— ‘Oh! Wait a moment, that is very serious!’

— ‘Pardon me; you must also arrange a dowry in case you leave the country.’

— ‘So, the woman is then free?’

— ‘Certainly, and you also; but, as long as you remain in the country, you are bound.’

— ‘Indeed, that is only just; but what about the fourth type of marriage?

— ‘That method, I advise you not to consider. You would be married twice: in the Coptic church and at the Franciscan convent.’

— ‘It’s a double-marriage?’

— ‘A very solid marriage: if you leave, you must take the wife with you; she can follow you everywhere, and place her children in your arms.’

— ‘So, once it’s over, one is married without remission?’

— ‘There are still many ways of rendering it null and void.... But above all, beware of one thing: allowing yourself to be led before the Consul!’

— ‘But that would be a European marriage.’

— ‘Exactly. You have only one resource then; if you know someone at the consulate, you arrange that the banns are not read in your country.’

The knowledge this silkworm-breeder possessed on the subject of marriage astounded me, but he told me he’d often been employed in such matters. He served as an intermediary for the wakil, who knew only Arabic. All these details, moreover, interested me in the last degree.

We had arrived almost at the edge of the city, in the part of the Coptic quarter which connects to Esbekieh Square on the Bulaq side. A rather poor-looking house at the end of a street crowded with herb-sellers and fried-food merchants, was the place where the introduction was to take place. I was informed that this was not the parents’ house, but neutral ground.

‘You will see two of them,’ Yousef said, ‘and if you are not satisfied, we’ll bring others.’

— ‘That’s perfect; but if they remain veiled, I warn you I’m not marrying them.’

— ‘Oh! Don’t worry, it’s not like the Turks here.’

— ‘The Turks have the advantage of an imbalance in numbers.’

— ‘Indeed, it’s quite different.’

The lower room of the house was occupied by three or four men in blue coats, who seemed to be asleep; however, thanks to the proximity of the city gate, and a guardhouse located nearby, this was not at all disturbing. We ascended a stone staircase to an interior terrace. The room which we entered overlooked the street, and the large window, with its meshed grille, projected, according to custom, a foot and a half beyond the house. Once seated in this kind of cupboard, one’s gaze covered both ends of the street; one could view passers-by through the lateral openings. Such is usually the women’s place, from which, as if from beneath a veil, they can observe everything without being seen. I was made to sit there, while the wakil, his son and Yousef took their places on the sofas. Soon a veiled Coptic woman arrived, who, after a greeting, raised her black burqa above, which, with the veil thrown back, formed a sort of Israelite headdress. This was the women’s khatba (matchmaker), or wakil. She told me that the young people were finishing dressing. Meanwhile, pipes and coffee had been brought to everyone. A white-bearded man in a black turban had also joined our company. He was the Coptic priest. Two veiled women, probably the mothers, remained standing at the door.

The matter was becoming serious, and my expectation was, I confess, mingled with some anxiety. At last, two young girls entered, and came to kiss my hand, successively. I invited them by signs to take a place near me.

— ‘Let them remain standing,’ Yousef said to me, ‘they are your servants’.

But I was far too French not to insist on them being seated. Yousef spoke, to clarify, no doubt, that it was a strange custom of the Europeans to have women sit in front of them. They finally took their places beside me.

They were dressed in flowered taffeta and embroidered muslin. It was very Spring-like. The headdress, composed of a red tarbouch entwined with gauze, let loose a tangle of ribbons and silken braids; bunches of small gold and silver coins, probably imitations, completely hid the hair. Yet it was easy to see that one was brunette and the other blonde; every objection had been anticipated. The first ‘was slender as a palm tree and had the black eyes of a gazelle,’ with a slightly swarthy complexion; the other, more delicate, fuller in contour, and of a paleness that astonished me because of the latitude, had the mien and bearing of a young queen born in the land of sunrise.

This latter particularly attracted me, and I had her say all kind of sweet things, without however entirely neglecting her companion. However, time passed without my broaching the main question; then, the khatba made them stand and uncover their shoulders, which she struck with her hand to show their firmness. For a moment, I feared that the exhibition would go too far, and I was myself a little embarrassed in front of these poor girls, whose hands covered their half-betrayed charms with gauze. Finally, Yousef asked: ‘What do you think?’

— ‘There is one that I like very much, but I would like to reflect on it: one should not get too excited. We will return and meet with them again.’

The assistants would certainly have liked more of an answer. The khatba and the Coptic priest pressed me to make a decision. I finally rose to my feet, promising to return; but I felt their lack of confidence.

The two young girls had exited during this negotiation. When I crossed the terrace to reach the stairs, the one I had noticed particularly seemed busy tending shrubs. She stood up, smiling, and, doffing her tarbouch, spread, over her shoulders, her magnificent golden tresses, to which the sun gave a bright reddish glow. This last effort of coquetry, quite legitimate however, almost triumphed over my prudence, and I sent word to the family that I would certainly send presents.

— ‘My goodness,’ I said as I left, to the obliging Israelite, I would marry that one before the Turk.

— ‘The mother would not wish it; they are attached to the Coptic priest. They are a family of scribes: the father is dead; the girl you preferred has only been married once, and yet she is sixteen years old.

— ‘What! Is she a widow?’

— ‘No, divorced.’

— ‘Oh! But that changes the situation!’

I still sent a small length of cloth as a present.

The blind man and his son set forth again to find me other fiancées. The ceremony was always more or less the same, but I took a liking to my review of the Coptic fair sex, and, in exchange for a few lengths of fabric and little jewels, they were not too offended by my uncertainty. There was a mother who brought her daughter to my lodgings: I believe that she would have gladly celebrated a marriage before the Turk; but, all things considered, the girl was of an age to have already been married more times than seemed reasonable.

Chapter 9: The Rosetta Gardens

The barbarian who was covering for Abdallah, being perhaps a little jealous of Yousef’s assiduity and his wakil, brought me a very well-dressed young man, who spoke Italian, named Mahomet, who had a very distinguished marriage to propose to me.

— ‘This,’ he said, ‘would take place before the Consul. They are rich, and the girl is only twelve years old.’

— ‘She is a little young for me; but it seems that here it’s the only age at which one does not risk them being already widowed or divorced.’

— ‘Signor, è vero! They are most impatient to see you, for you occupy a house previously occupied by Englishmen; therefore, they have a high opinion of your rank. I said you were a general.’

— ‘But I’m not a general.’