Gérard de Nerval

Travels in the Near East (Voyage en Orient, 1843)

Part III: Introduction – Towards the Orient (1839-40, 1842-43)

From Paris to Cythera: Chapters 12-21

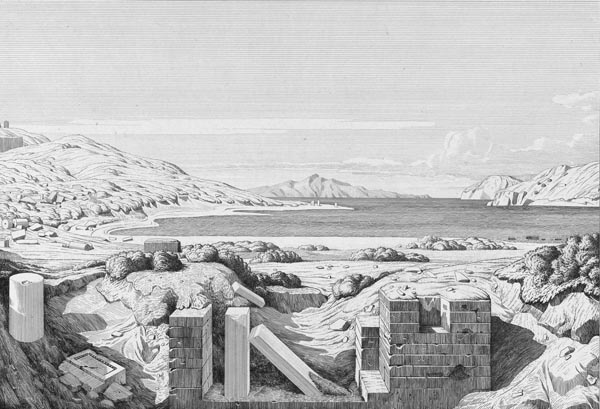

View of the Cyclades, 1845, Claude-Félix-Théodore Caruelle d'Aligny

Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter 12: The Archipelago.

- Chapter 13: Venus’s Mass.

- Chapter 14: Poliphilo’s Dream.

- Chapter 15: St. Nicolas.

- Chapter 16: Aplunari.

- Chapter 17: Paleokastro.

- Chapter 18: The Three Venuses.

- Chapter 19: The Cyclades.

- Chapter 20: The Cathedral of Saint George.

- Chapter 21: The Windmills of Syros.

(Translator’s note: the narrative now follows Gérard’s actual route, of 1843. Having sailed from Marseilles via the Italian coast and Malta, he passed Cythera, at dawn, on January 10th, 1843)

Chapter 12: The Archipelago

We had left Malta two days before, and no new land had appeared on the horizon. Doves — perhaps from Mount Eryx (the site, in Sicily, of the famous temple of Venus-Aphrodite) — had taken passage with us for Cythera or Cyprus, and were resting at night on the yards and in the tops.

The weather was fine, the sea calm, and we had been promised that on the morning of the third day we would be able to see the southern tip of the Morea. Must I confess? The appearance of the isles of Greece, reduced to their rocks, stripped by hostile winds of the little sandy earth that had remained after centuries, hardly corresponds to the idea that I had of them yesterday when I awoke. However, I was on deck at five o’clock, searching for the absent land, closely examining the edge of the dark blue circle traced by the waters beneath the azure dome of the sky, waiting to catch sight of Mount Taygetus, far away, like the apparition of some deity. The horizon was still dark; but the daystar shone, with a clear shaft of fire furrowing the sea. The wheels of the ship chased away the dazzling foam, which left far behind us its long trail of phosphorus. ‘Beyond this sea,’ said Corinne (See ‘Corinne’ by Madame de Staël, XV, 9), turning towards the Adriatic, ‘lies Greece.... Is not this idea enough to move us?’ And I, happier than she, happier than Johann Winckelmann, who dreamed of it all his life, and happier than the modern Anacreon (Pierre-Jean de Béranger, according to Gérard), who wishes to die there — I was about to see her at last, luminous, rise from the waters with the sun!

I saw her thus, I have seen her, my day began like a song of Homer! It was truly rosy-fingered Aurora (goddess of the dawn) who opened the gates of the Orient to me! And let us speak no longer of dawn in our countries, the goddess does not reach so far. What we barbarians call dawn, or daybreak, is only a pale reflection, tarnished by the impure atmosphere of our deprived climes. Behold, already, with the ardent line which widens on the circle of waters, a sheaf of pink rays blooming, reviving the azure of the air which higher above still remains dark. Would one not say that the brow of a goddess, and her outstretched arms, are gradually lifting the veil of night, still glittering with stars? She appears, she approaches, she glides, lovingly, over the divine waves which gave birth to Cytherea (the goddess Venus-Aphrodite) .... But what say I? Before us, on the horizon there, that vermilion coast, those purple hills which seem like clouds, reveal the very island of Venus, it is ancient Cythera with its porphyry rocks: Κυθήρη πορφυροῦσσα (Cythera purperea) .... Currently, the island is called Cerigo, and belongs to the English (1809-1864).

This was my dream ... and this my awakening! The sky and the sea are still here; the sky of the East, the sea of Ionia grant each other, each morning, the sacred kiss of love; but the earth is dead, dead beneath the hand of man, and the gods have flown!

‘I will teach you the truth of the oracles of Delphi and Claros,’ Apollo said to his priest. ‘Formerly, there came forth from the bosom of the Earth, and the woods, an infinity of oracles and exhalations which inspired the divine furies. But the Earth, by the continual changes that time brings, has gathered up and drawn back into its fount, all exhalations and oracles.’ This is what Porphyry reported, according to Eusebius (in the latter’s ‘Contra Porphyrium’, of which only fragments exist).

Thus, the gods themselves die, or quit the Earth, to which human love no longer summons them! Their groves have been cut down, their springs exhausted, their sanctuaries profaned; where can they manifest their presence again? O Venus Urania, queen of this isle and this mount, whence your features threatened the world; Venus Armata (Venus Victrix), who has reigned over me since the Capitol, where I saluted (in the museum) your extant statue, why have I not the courage to believe in you and to invoke you, goddess, as our forefathers did, for centuries, with fervour and simplicity? Are you not the source of all love, all noble ambition, the second of the sacred mothers who sit enthroned at the world’s heart, guarding and protecting the eternal idea of womankind from the double assault of death which transforms them, or nothingness which seduces them? ... But you are there still, amidst the glittering stars; mankind is forced to recognise you in the heavens, and science to name you. O you, the triple goddess, do you forgive the ungrateful earth for having neglected your altar?

To revert to prose, it must be admitted that Cythera has preserved, of all its beauties, only its porphyry, as melancholy to the sight as simple sandstone. Not a tree on the coast that we followed, not a rose, alas, not a shell along this shore from which the Nereids chose Aphrodite’s conch-shell. I sought Jean-Antoine Watteau’s shepherds and shepherdesses, their boats adorned with garlands approaching flowery banks; I dreamed of those mad bands, the pilgrims of love, in cloaks of shimmering satin.... I only saw a gentleman shooting woodcock and pigeon, and some blonde, dreamy Scottish soldiers, searching the horizon perhaps for the mists of their homeland.

We stopped, shortly, at the port of St. Nicolas, at the eastern tip of the island, opposite Cape Malea, which could be seen some seventeen miles away across the sea. The short duration of our stay did not allow a visit to Capsali, the capital of the island; but, to the south, one could see the rock which dominates the town, and from which one can view the whole island of Cythera, as well as a part of the Morea, and even the coast of Crete when the weather is clear. It is on this height, crowned today with a military fortification, that the temple of Celestial Venus stood. The goddess was dressed as a warrior, armed with a javelin, and appeared to dominate the sea, and guard the fate of the Greek archipelago from those cabalistic figures of the Arabian tales, that must be overcome in order to destroy the spells brought about by their presence. The Romans, descended from Venus through their ancestor Aeneas, were the only ones able to remove her statue of myrtle-wood, whose powerful contours draped in symbolic veils recalled the primitive art of the Pelasgians, from this superb rock. It was indeed the great goddess of generation, Aphrodite Melaenis, or the Black One, wearing the hieratic polos crown (tall and cylindrical) on her head, with irons on her feet, as if chained by force to the destiny of Greece, which had conquered her beloved Troy.... The Romans transported her to the Capitol, and soon Greece, in a strange twist of fate, belonged to the regenerated descendants of the vanquished royalty of Ilion.

Who, however, would recognize, in the cosmogonic statue that we have just described, the frivolous Venus of the poets, the mother of Cupid, the amorous wife of lame Vulcan?

She was called the provident, the victorious, the dominatrix of the seas — Euploia, Pontia —Apotrophia, who expels criminal passion; and again, was named the eldest of the Fates, a dark idealisation. On either side of the painted and gilded idol stood the two gods of love, Eros and Anteros, dedicating poppies and pomegranates to their mother. The symbol that distinguished her from the other goddesses was a crescent surmounted by an eight-rayed star; this sign, embroidered on purple, still reigns over the East, and truly among those who wear it Venus has ever a veil on her head, and chains on her feet.

This was the austere goddess worshipped in Sparta, Corinth, and in a certain place on Cythera with its rugged rocks; she was truly the daughter of a mother fertilised by the divine blood of Uranus, emerging cold as yet from the torpid flanks of Nature and Chaos.

The other Venus — since many poets and philosophers, especially Plato, recognise two separate Venuses — was the daughter of Jupiter and Dione; she was called Venus Pandemos (the earthly Venus, of the people), and had, in another part of the island of Cythera, altars and followers quite different from those of Venus Urania (celestial Venus). The poets were able to occupy themselves freely with the former, who unlike the other, was not protected by the laws of a severe theogony, and they lent her all their amorous fancies, which have transmitted to us a false image of the serious worship enacted by the pagans. What would be thought, in the distant future, of the mysteries of Catholicism, if posterity was reduced to judging them via the ironic interpretations of Voltaire or Évariste de Parny? Lucian, Ovid, Apuleius, belonged to no less sceptical eras, and they alone have influenced our superficial minds, which lack the curiosity required to study the old cosmogonic poems derived from Chaldean or Syriac sources.

Chapter 13: Venus’s Mass

The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (‘Poliphilo’s Dream’, attributed to Francesco Colonna, latinised as Franciscus Columna) gives some curious details regarding the cult of the Celestial Venus in the island of Cythera, and, without admitting as an authority this book, many pages of which imagination has coloured, we can often find there the result of studied and faithful impressions.

Two lovers, Poliphilo and Polia, prepare for a pilgrimage to Cythera.

They visit the sea-shore, and the sumptuous temple of Venus Physizoe (the Giver of Life), There, priestesses, led by a mitred praying woman, first address orations to the gods Foricula, and Limentina, and to the goddess Cardea (the three divinities of the door, the sill, and the door-hinges). The nuns were dressed in scarlet, and wore, in addition, short, light cotton surplices; their hair hung over their shoulders. The first held the book of ceremonies; the second, an almusse (cap) of fine silk; the others, a golden shrine, the cecespita or sacrificial knife, and the prefericulum, or libation-bowl; the seventh wore a golden mitre with pendants; the smallest held a candle of virgin wax; all were crowned with flowers. The almusse worn by the praying woman had attached, in front of the forehead, a golden clasp inlaid with an ananchyte, a talismanic stone used to evoke the figures of the gods.

The praying woman led the lovers to a cistern situated in the midst of the temple, and opened its lid with a golden key; then, reading in the holy book, by the light of the candle, she blessed the sacred oil, and poured it into the cistern; then she took the candle, and moved the torch near to the opening, saying to Polia: ‘My daughter, what do you ask?’ – ‘Lady, she said, I ask grace for him who is with me, and desire that we may visit, together, the kingdom of the great divine Mother to drink from her holy fountain.’ Whereupon the praying woman, turning to Poliphilo, made a similar request of him, and urged him to plunge the torch completely into the cistern. Then she tied with a cord, a vessel, called a lepaste (shaped like a cylix, resting on a broad stand), which she lowered into the holy water, drew some forth, and had Polia drink it. Finally, she shut the cistern, and implored the goddess to be favourable to the two lovers.

After these ceremonies, the priestesses entered a sort of circular sacristy, to which two white swans and a vase full of sea water were brought, and then two turtledoves tied to a basket, filled with shells and roses, which were placed on the sacrificial table; the young girls knelt around the altar, and invoked the most holy Graces, Aglaia, Thalia and Euphrosyne, ministers of Cytherea, praying them to leave the anclabris mensa, (the sacrificial table) which is at Orchomenus, in Boeotia, where they reside, and, as divine Graces, to descend, and accept the religious tribute made to their mistress in their name.

After this invocation, Polia approached the altar which was covered with spices and perfumes, set it on fire, and fed the flame with branches of dried myrtle. Then she placed upon it the two turtledoves, which were struck with the cecespita, and plucked on the anclabris mensa, the blood being set aside in a sacred vessel. Then began the divine service, intoned by a cantoress, to which the others responded; two young nuns, placed in front of the praying woman, accompanied the office with Lydian flutes in the natural Lydian tone. Each of the priestesses carried a branch of myrtle and, singing in tune with the flutes, danced around the altar while the sacrifice was consumed.

I have merely summarised, for the benefit of artists, the main details of Venus’s Mass as sometimes performed.

We shall see what other ceremonies were performed, on Cythera itself, in that realm of the mistress of the world — κυποια κυθηπειον και εανθου κοσμου — today ruled by another gracious female power, Queen Victoria.

Chapter 14: Poliphilo’s Dream

I am far from wanting to cite Poliphilo as a scientific authority; Poliphilo, that is to say Francesco Colonna, was doubtless swayed by the ideas and vision of his day; but that does not prevent his having drawn certain contents of his book from authentic Greek and Latin sources, while I might have done the same, but preferred to cite him.

May Poliphilo and Polia, those holy martyrs of love, forgive me for touching on their memory! Chance — if it was chance — placed their mystical history in my hands, and I was unaware that, at that very moment, a more learned poet, more learned than I, had shed the last gleam of genius that his bowed forehead concealed on those same pages. He was, like those martyrs, one of the most faithful apostles of pure love... and, among us, one of the last.

Accept this souvenir from one of your unknown friends, good Nodier, beautiful divine soul, who immortalised the pair, while dying (see Charles Nodier’s last work, ‘Franciscus Columna’, published 1844)! Like you, I believe in them, and, like them, in the celestial love whose flame Polia rekindled, and whose splendid palace on the Cytherean rocks Poliphilo rebuilt in thought. You know who the true gods are today, doubly-crowned spirits: pagans as regards genius, Christians at heart!

And I, who am going to disembark at this sacred isle that Francesco described without ever having seen it, am I not still, alas, the child of a century disinherited of illusion, who needs to touch in order to believe, and to dream of the past ... among its ruins? It sufficed only for me to commit the flesh and ashes of all I loved to the tomb, to confirm that it is we, the living, who walk in a world of ghosts.

Poliphilo, wiser than I, knew the true Cythera without visiting it, and true love, through having rejected its mortal image. It is a touching story that may be read in Charles Nodier’s last novella, if one has not been able to divine it veiled in the poetic allegories of Poliphilo’s Dream.

Francesco Colonna, the author of this work, was a poor fifteenth century artist, who fell madly in love with a princess, Lucrezia Polia of Treviso. An orphan, taken in by Jacopo Bellini, father of the most illustrious painter we know (Giovanni Bellini), he did not dare raise his eyes to the heiress of one of the greatest houses in Italy. It was she herself who, taking advantage of the freedom of a Carnival night, encouraged him to tell her everything, and showed herself touched by his pain. She is a noble figure, this Lucretia Polia, the poetic sister of Juliet (see Shakespeare’s play ‘Romeo and Juliet’), Leonora (the heroine of Beethoven’s opera ‘Fidelio’) and Bianca Capello (the lover of Francesco I de’ Medici). Their difference in status made marriage impossible; the altar of Christ ... the God of equality! ... was forbidden them; they dreamt of more indulgent deities, they invoked the ancient Eros and his mother, Aphrodite, and their homage rose towards distant skies unaccustomed to our prayers.

From that hour, imitating the chaste love of the followers of Venus Urania, they committed themselves to living apart during life, so as to be united after death, and, strangely enough, it was according to the forms of the Christian faith that they accomplished this pagan vow. Did they think to see in the Virgin and her son an ancient symbol of the divine Great Mother, and the celestial child who sets hearts ablaze? Did they dare to penetrate through the mystical darkness to the primitive Isis of the eternal veil, the changing mask, holding in one hand the ansate cross (the ankh), and on her knees the child Horus, the saviour of the world?...

Well, such strange assimilations were then in great fashion in Italy. The Neoplatonic school of Florence triumphed over Aristotle, and feudal theology opened like black tree-bark to the fresh buds of the philosophical Renaissance which flourished on all sides. Francesco became a monk, Lucrezia a nun, and each kept in their heart the pure and beautiful image of the other, passing their days in the study of ancient philosophy and religion, and the nights in dreaming of their future happiness, adorning it with the splendid details revealed to them by the ancient Greek writers. O happy and blessed double existence, if we are to believe the book that immortalises their love! Sometimes the pompous festivals of the Italian clergy brought them together in the same church, streets, squares where solemn processions took place, and alone, unknown to the crowd, they greeted each other with a sweet and melancholy look: ‘Brother, we will die!’ – ‘Sister, we will die!’ that is to say: we have only a short time left to drag our chain behind us...the smile exchanged said nothing but that.

However, Poliphilo wrote and bequeathed to future lovers the noble and admirable story of their struggles, their pains, their joys. He described those enchanted nights where, escaping from our world full of the law of a harsh God, in spirit he joined his sweet Polia in the holy dwelling-places of Cytherea. The faithful soul could not wait, and the whole mythological realm opened to them from that moment. Like the hero of a more modern and no less sublime poem (Goethe’s ‘Faust, Part II’), they traversed in their twin dream the immensity of space and time; the Adriatic Sea and dark Thessaly, where the spirit of the ancient world was extinguished on the field of Pharsalus (where Julius Caesar defeated Pompey)! The fountains began to well up in their caves, the rivers became streams again, the arid summits of the mountains were crowned with sacred woods; the Peneus flooded its changed shores once more, and everywhere could be heard the muffled labours of the Cabeiri (pre-Olympian chthonic deities) and the Dactyls (the male followers of Cybele-Rhea, the Great Goddess) constructing, for them, the phantom of a universe. The star of Venus grew like a magical sun, to pour golden rays on these deserted beaches, that their deaths would repopulate; the faun awoke in his lair, the naiad in her fountain, and the hamadryads escaped their green groves. Thus, the holy aspiration of two pure souls restored to the world, for an instant, its fallen powers, and the guardian spirits of its ancient fertility.

It was then that the pilgrimage took place, and continued night after night, which led our two lovers, over the plains and rejuvenated mountains of Greece, to all the renowned temples of Celestial Venus, and finally brought them to the principal sanctuary of the goddess, on the isle of Cythera, where the spiritual union of the two adherents, Poliphilo and Polia, was accomplished.

Brother Francesco died first, having completed his pilgrimage and his book; he bequeathed the manuscript to Lucrezia, who, great and powerful lady that she was, did not fear to have it printed by Aldus Manutius, and illustrated with drawings, most of them very beautiful, representing the principal scenes of the dream, the ceremonies of sacrifice, the temples, figures and symbols of the divine Great Mother, the goddess of Cythera. This book of platonic love was for a long time the gospel of loving hearts, in the lovely country of Italy which did not always pay such refined tributes to the Celestial Venus.

Could I do better than reread, before touching on Cythera, that strange book by Poliphilo, which, as Charles Nodier has pointed out, reveals a charming and unique feature; the author has signed his name and indicated his love, by employing the letters at the head of each chapter, chosen to form the following legend: Poliam frater Franciscus Columna peramavit (brother Francesco Colonna loved Polia dearly). What is the love of Abelard and Héloïse compared to this?

Chapter 15: St. Nicolas

When I set foot on the soil of Cythera, I had difficulty accepting that this island, in the early years of the century, belonged to France (1807-1813). Heir to the possessions of Venice, our homeland has, in turn, seen itself despoiled by England, which, there, as in Malta, announces to passers-by on a marble tablet, in Latin that ‘the treaty of Europe, and the love of these islands, have, since 1814, assured it of sovereignty.’ — Love! God of the Cythereans, have you, indeed, ratified this claim?

While we were skirting the coast, before taking shelter at St. Nicolas, I noticed a small monument, vaguely outlined against the azure sky, and which, from the top of a rock, seemed the extant statue of some protective divinity.... But, as we approached nearer, we clearly distinguished the object which drew the traveller’s attention to this stretch of the coastline. It was a gibbet, a gibbet with three arms, only one of which was furnished. The first real gibbet that I have yet seen, it was on the soil of Cythera, an English possession, that I first chanced to see it!

I shall not visit Capsali (Chora); I know nothing remains of the temple that Paris built, dedicated to Venus Dionaeus, when bad weather forced him to remain in Cythera, for sixteen days, with Helen, whom he had abducted from her husband, Menelaus. It is true that the fount which supplied water to the crew, the basin where that most beautiful of women washed her clothes, and those of her lover, with her own hands, is still shown; but a church was built on the ruins of the temple, and can be seen in the midst of the port. Nothing remains too, of the temple of Venus Urania on the cliff top, which was replaced by the Venetian fort, today guarded by a company of Scots.

Thus, the Celestial Venus, and Venus Pandemos, revered, one on the heights, and the other in the valleys, have left no traces in the capital of the island, and no one has bothered to excavate the ruins of the ancient city of Skandia, near the port of Avlemonas, hidden deep in the bosom of the earth; there, perhaps, one might find some relics of the third Venus, the eldest of the Fates, the ancient queen of mysterious Hades.

For, it must be noted – so as to escape the maze into which the last of the Latin poets and the modern mythologists have led us – that each of the great goddesses had three masks, and was worshipped in three forms; those of heaven, earth, and hell; a triplicity, however, that should not seem strange to the Christian mind, which accepts three persons in one deity.

The port of St. Nicolas offered to our eyes only a few huts on a sandy bay, where a stream flowed forth, and a few fishing boats had been pulled ashore; others spread their lateen sails on the horizon, on the dark line traced by the sea, beyond Cape Spathi, the northernmost point of the island, and Cape Malea, which could be clearly seen on the Greek side. No one came to inspect our papers when we disembarked; the islands belonging to the English do not abuse their use of police and the law, and, if their legislation still provides for a whip below, and a gibbet above, foreigners at least have nothing to fear from those methods of repression.

I was eager to taste the wines of Greece, instead of the dense, dark Maltese wine which had been served us, for two days, on board the steamship. So, I did not disdain to enter the humble tavern, which also served as a common rendezvous for English coastguards and Greek sailors. The painted front displayed, as in Malta, the names of English beers and liqueurs inscribed in gold. Seeing me dressed in a mackintosh bought in Livorno, the host hastened to fetch me a glass of whiskey; I tried, for my part, to remember the name that the Greeks gave to wine, and pronounced it so perfectly that I was not understood at all. – What use is it now to have been granted a bachelor’s degree by François Guizot, Abel-François Villemain, and Victor Cousin (Ministers of Public Instruction) combined, or to rob France of twenty minutes of their time to witness to my knowledge? College has made me such a great Hellenist that I find myself in a tavern on Cythera asking for wine so expertly that the host, immediately withdrawing the whiskey I have refused, serves me a jug of beer. I managed to scrape together three words of Italian, and, as no one had ever taught me that language, I easily succeeded in having a bottle of Cytherean liquid brought to my table.

It was a good little red wine, smelling somewhat of the wineskin in which it had been kept, and also of tar, but full of warmth and recalling the taste of the bone-dry asciutto wines of Italy — oh, generous blood of the grape!... as George Sand names you (see ‘Les Lettres d’un Voyageur, X’), as soon as you are inside me, I am no longer the same; are you not truly the blood of a god? And perhaps, as the Bishop of Cloyne (George Berkeley) said, the blood, too, of those rebellious spirits who fought in ancient times on earth, and who, vanquished, annihilated in their first form, return, in wine, to agitate us with their passion, their anger and their strange ambition!...

But no, that which comes from the holy veins of this isle, from the porphyrous and long-blessed earth where Celestial Venus reigned, can only inspire good and sweet thoughts. So I thought of nothing thenceforth but to seek out, piously, some trace of the ruined temples of the goddess of Cythera; I climbed the cliffs of Cape Spathi, where Achilles built a shrine, before he left for Troy; I looked for Cranae, on the other side of the gulf, which was the site of Helen’s abduction; but the isle of Cranae merged in the distance with the coast of Laconia, and not a stone of the temple remained on the cliffs, from whose summit one discovers, on gazing towards the island, only water-mills set in motion by a small river which flows into the bay of St. Nicolas.

On the way down, I met some of the other passengers, who planned on visiting a small town, a few miles away, a more considerable place even than Capsali. We mounted mules, and, under the guidance of an Italian who knew the countryside, we sought a route through the mountains. One would never believe, on seeing from the sea the approaches to Cythera bristling with the rocks, that the interior contains so many fertile plains; it is, after all, an island which is seventy miles or so in circumference, and whose cultivated areas are clothed with cotton, olive, and mulberry trees, sown among the vines. Oil and silk are the principal products providing the inhabitants with a livelihood, and the Cythereans — I prefer not to call them Cerigots (Cerigo was the Venetian name for the island) — find, in preparing the latter, a labour gentle enough for their lovely hands; the cultivation of cotton has been affected, on the contrary, by the English having taken possession....

Do you not admire all these beautiful details in the style of a guidebook? It’s only that modern Cythera, not being on the usual route taken by travellers, has never been described at length, and I will at least have the merit of having said more than the English tourists have done.

The goal of my companions’ trip was Potamos, a small town with an Italianate appearance, though poor and dilapidated; mine was the hill of Aplunari, situated a short distance away, where I had been told I would find the remains of a temple. Dissatisfied with my journey to Cape Spathi, I hoped to compensate for it, and be able, like the good Abbé Delille (the poet, Jacques Delille), to fill my pockets with mythological debris. Oh happiness! I encountered, as we approached Aplunari, a small wood of mulberry and olive trees where a few rare pines, here and there, extended their dark parasols; aloes and cacti bristled amidst the undergrowth, and on the left the great blue eye of the sea that we had lost sight of for some time opened once more. A stone wall seemed to partly enclose the wood, and, on a piece of marble the remains of an ancient arch that surmounted a square door, I could distinguish these words: ΚΑΡΔΙΩΝ ΘΕΡΑΠΙΑ (kardion therapia, the healing of hearts).

The inscription made me sigh.

Chapter 16: Aplunari

The hill of Aplunari possesses only a few ruins, but has preserved the even rarer remains of the sacred vegetation which once adorned the cliff-face; evergreen cypresses, and a few ancient olive trees whose cracked trunks are the refuge of bees, have been preserved by the kind of venerable tradition attached to such illustrious places. The remains of a stone enclosure protect, but only on the seaward side, this little grove which is the heritage of a single family; the door has been surmounted by an arched stone, retrieved from the ruins, whose inscription I have already given. Beyond the enclosure is a small house surrounded by olive trees, the home of these poor Greek peasants, who for fifty years have seen the Venetian, French, and English flags succeed one another on the towers of the fort, which protects St. Nicolas and can be seen at the other end of the bay. The memory of the French Republic, and of Bonaparte who had freed them (1797-1799), and later, as the Emperor Napoleon, dissolved the Russo-Ottoman Republic of the Seven Isles (in 1807), is still present in the minds of the older inhabitants.

England has shattered this fragile liberty since 1815, and the inhabitants of Cythera have watched, joylessly, the triumph of their brothers of the Morea. England does not make the people she conquers or rather that she acquires, English; she makes helots of them, sometimes servants; such is the fate of the Maltese, such would be that of the Greeks of Cythera if the English aristocracy did not disdain this dusty and sterile island as a residence. However, there is a kind of wealth of which our neighbours have nonetheless stripped ancient Cythera: I mean the bas-reliefs and statues which still indicated sites worthy of memory. They removed, from Aplunari, a marble frieze on which one could read, despite some abbreviations, these words, which were transcribed in 1798 by commissioners of the French republic: Ναὸς Ἁφροδίτης θεᾶς κυρίας Κυθηρίων, και Παντὸς κὸσμου (the temple of the goddess Venus, ruler of the Cythereans and the whole world).

This inscription leaves no doubt as to the character of the ruins; but, in addition, a bas-relief, also removed by the English, had long served as the covering of a tomb in the wood of Aplunari. There, the images of two lovers could be discovered, bringing an offering of doves to the goddess, and advancing towards the altar, near which was placed the vase of libations. The young girl, dressed in a long tunic, presented the sacred birds, while the young man, leaning with one hand on his shield, seemed with the other to assist his companion in placing her gift at the feet of the statue; Venus was dressed much like the young girl, and her hair, braided at the temples, fell in curls on her neck.

It is evident that the temple situated on this hill was not consecrated to Venus Urania, the Celestial Venus worshipped in other parts of the island, but to the second Venus, Venus Pandemos, the Earthly Venus, who presided over marriage. The first, brought here by inhabitants of the ancient city of Ascalon in Syria, a stern divinity, symbolically complex, of doubtful sex, had all the characteristics of primitive images loaded to excess with attributes and hieroglyphics, such as the Diana of Ephesus or the Cybele of Phrygia; she was adopted by the Spartans, who were the first to colonise the island; the second, more cheerful, more human, whose cult, introduced by the victorious Athenians, was the subject of civil wars between the inhabitants, was represented by a statue renowned throughout Greece as a wondrous work of art; she was naked, and held in her right hand a sea-shell; her sons Eros and Anteros accompanied her, and before her were grouped the three Graces, two of whom were looking towards her, and the third of whom was turned in the opposite direction. In the eastern part of the temple was a notable statue of Helen; which is probably the reason why the inhabitants of the country name these ruins the Palace of Helen.

Two young men offered to conduct me to the ruins of an ancient city of Cythera, whose dusty mound could be seen on the coast, between the hill of Aplunari and the port of St. Nicolas; I had passed them on my way to Potamos via the interior; but the road was only passable on foot, and the mule had to be returned to the village. I left with regret the little grove, richer in memories than in the few fragments of pillars and capitals disdained by the English collectors. Outside the wooded enclosure, three truncated columns still stood in the midst of a cultivated field; other fragments had been used to build a small house with a flat roof, situated at the steepest point on the mountain, but whose solidity is guaranteed by an ancient stone causeway. This remainder of the temple foundations also serve to form a sort of terrace which retains the topsoil necessary for crops, so rare on the island since the destruction of the sacred forests. There is an excavation site which may be examined there; a white marble statue draped in the antique style, badly mutilated, has been extracted; but it was impossible to determine its original characteristics. Descending among the dusty rocks, sometimes varied by olive trees and vines, we crossed a stream which plunges down to the sea in cascades and which flows among mastic trees, oleanders and myrtles. A Greek chapel has been erected on the banks of this beneficent water, and appears to have succeeded an older monument.

Chapter 17: Paleokastro

We followed the edge of the sea, walking the sand, and admiring, from time to time, caves into which the waves rush during storms; the quails of Cythera, much appreciated by hunters, were fluttering here and there on the neighbouring rocks, among tufts of sage with ashen-coloured leaves. Having reached the end of the bay, we were able to take in the whole hill of Paleokastro covered with debris, and dominated still by the ruined towers and walls of an ancient city. The enclosure is marked out on the slope facing the sea, and the remains of the buildings are partly hidden beneath the sand piled up by the waves at the mouth of a little river. It would seem that the greater part of the city has gradually vanished due to the force of the rising tide, and an earthquake, of which all these places bear traces, has altered the surface of the land. According to the inhabitants, when the waters are very clear, the remains of considerable buildings can be distinguished on the sea-bed.

Crossing the little river, one arrives at ancient catacombs carved from the cliff which dominates the ruins of the city, and to which one climbs by a path cut into the stone. The catastrophe revealed by certain features of the desolate beach, has split this funerary rock from top to bottom and opened to the light of day the hypogea (underground chambers) it contains. One can distinguish, through the opening, the opposite sides of each room, parted as if by miracle; it is only after having climbed the rock that one can descend to these catacombs, which seem to have been inhabited recently by shepherds; perhaps they served as a refuge during wars, or at the time of the Ottoman occupation.

The summit of the rock itself is an oblong platform, bordered by, and strewn with, debris which indicates the ruins of a superior building; it was, doubtless, a temple dominating the tombs, and beneath the shelter of which rested pious ashes. In the first room that I entered, I noted two sarcophagi cut in stone and covered with a curved arch; the slabs that closed them, and of which one can no longer see anything but the remnants, were lying apart; on both sides, niches had been made in the wall, either for lamps or lachrymatory vases, or to contain funerary urns. But, if there were urns here, what need for the sarcophagi? It is true that it was not always the custom of the ancients to immolate bodies, since, for example, one of the two Ajaxes was buried in the earth; but, if the custom varied over time, would the one and the other mode have been indicated in the same monument? Could it be that what appear to us to be tombs were only multiple vats of lustral water for the use of the temples? Here, doubt is allowed. The decoration of these rooms seems to have been architecturally simple; no sculpture, or column, to vary their uniform construction; the walls are squarely cut, the ceiling flat; only, one notices that originally the walls were covered with a mastic on which appear traces of ancient paintings, executed in red and black in the Etruscan manner.

Out of curiosity, people have cleared the entrance to a larger room dug into the mountain massif; it is vast, square and surrounded by rooms or cells, separated by pilasters, which may have been either tombs or chapels; since, according to many, this immense excavation may be the site of a temple dedicated to the underworld divinities.

Chapter 18: The Three Venuses

It is hard to say whether it was on this rock that the temple of Celestial Venus was built, which was indicated by Pausanias (in his ‘Description of Greece’, III, 23) as dominating Cythera, or if that monument stood on the hill still covered with the ruins of the city which some authors (Jacob Spon and George Wheler, see ‘Voyage du Levant fait aux années 1675 et 1676, I, p.96’) also call the City of Menelaus. In any case, the singular arrangement of this rock reminded me of that of another temple of Urania which the Greek author describes elsewhere as being placed on a hill outside the walls of Sparta. Pausanias, himself a Greek of the decadent period, a pagan in an era when the meaning of the old symbols had been lost, was astonished by the very primitive construction of the two superimposed temples dedicated to the goddess. In one, the lower, we see her covered in armour, like Minerva, as an epigram of Ausonius describes her (see Ausonius: ‘Epigrams XLII and XLIII’); in the upper temple, she is represented covered, entirely, with a veil, with chains on her feet. This last statue, carved in cedar wood, was said to have been erected by Tyndareus and was called Morpho, another epithet of Venus (Pausanias III, 15). Is this the subterranean Venus, the one the Romans called Libitina, the one who was represented uniting Pluto with chilly Persephone in the underworld, and who, still, under the nickname of Eldest of the Fates, is sometimes confused with the beautiful and pale Nemesis?

People have smiled at the concerns of that poetic traveller ‘so concerned to stress the whiteness of the marble he viewed,’ and perhaps people will be surprised, in this day and age, to see me spend so much effort on establishing the triple personality of the goddess of Cythera. Certainly, it is not difficult to find, in her three hundred nicknames and attributes, proof that she belonged to the class of those pantheistic divinities, who presided over all the forces of Nature in the three regions of the heavens, the earth, and the subterranean places. But I wish to show, above all, that the cult of the Greeks was mainly addressed to the austere, ideal, and mystical Venus, whom the Neoplatonists of Alexandria would oppose, shamelessly, to the Virgin of the Christians. The latter, more human, easier to understand for all, has now conquered the philosophical Urania. Today, the Greek Panagia (the Virgin Mary) has succeeded, on these very shores, to the honours of the ancient Aphrodite; the church or chapel is rebuilt from the ruins of the temple, and applies itself to concealing its foundations; the same superstitions are attached almost everywhere to very similar attributes; the Panagia, who holds in her hand a ship’s prow, has taken the place of Venus Pontia; another receives, like Venus Calva (the Bald Venus), the tribute of hair that young girls hang on the walls of her chapel. Elsewhere arose the Venus of the Flames, or the Venus of the Abyss; the Venus Apostrophia, Venus the Preserver, who warded off impure thoughts, or the Venus Peristeria, Venus of the Doves, who had the sweetness and innocence of those birds: the Panagia is sufficient to realise all these epithets. Do not demand new beliefs from the descendants of the Achaeans: Christianity has not conquered them, they have bent it to their ideal; the female principle, or, as Goethe says (at the end of ‘Faust, Part II’), the eternal feminine will always reign on these shores. The dark, cruel Diana of the Bosphorus, the prudent Minerva of Athens, the Armed Venus of Sparta, such were the emblems of their most sincere religious devotion: today’s Greece replaces all these various holy virgins with a single one, and counts for little the masculine trinity and all the saints of legend, with the exception of Saint George, that young and brilliant cavalier.

Quitting this strange rock, pierced with funereal rooms, whose base the sea assiduously gnaws, we arrived at a cave which stalactites have decorated with pillars and wondrous sheets of stone; shepherds had sheltered their goats, there, against the heat of the day; but the sun soon began to decline towards the horizon, casting its purple light on the distant rock of Cerigotto (Antikythera), an old retreat of pirates; the cave was dark, and poorly lit at this hour, and I was not tempted to enter it with torches; however, everything within reveals the antiquity of this land loved by the heavens. Petrified fossils, even piles of antediluvian bones have been extracted from this cave, as well as from several other sites on the island. So it is not without reason that the Pelasgians placed there the cradle of this daughter of Uranus, of this Venus so different from that of the painters and poets, whom Orpheus invoked, in a manner similar to this (see ‘Orphic Hymn, 54: To Aphrodite’): ‘Venerable Goddess, who loves the darkness... visible and invisible... from which all things emanate, for you give laws to the whole world, and even command the Fates, O Sovereign of the night!’

Chapter 19: The Cyclades

Kythera and Antikythera still displayed their angular outlines on the horizon; soon we rounded the point of Cape Malea, passing so close to the Morea that we could distinguish all the details of the landscape. A singular dwelling attracted our attention; five or six stone arches supported the front of a sort of grotto behind a small garden. The sailors told us that it was the dwelling-place of a hermit, who had long lived and prayed on this isolated promontory. It is a magnificent place, indeed, to dream to the sound of the waves like some romantic Byronic monk! The ships that pass sometimes send a boat to bring alms to this solitary, who is probably a prey to the curiosity of the English. He did not show himself: perhaps he was dead.

At two in the morning the sound of the anchor chain being dropped woke us all, and announced to us amidst our dreams that, on that very day, we would tread the soil of a truly regenerated Greece. The vast harbour of Syros surrounded us in a crescent.

I have been living since this morning in complete rapture. I would like to remain forever among these good Hellenic people, in the midst of these islands with sonorous names, from which exhale the perfumes of The Garden of Greek Roots (see Claude Lancelot’s etymological dictionary ‘Le Jardin des Racines Greques, 1657’) Ah! How I now thank my good teachers, so often cursed, for having taught me the means of deciphering, in Syros, the barber’s, shoemaker’s and tailor’s signs. Why! Here are the same round letters and the same capitals ... which I know how to read at least, and so grant myself the pleasure of spelling them aloud in the street.

— ‘Καλιμέρα (kaliméra: good day)’, the merchant said to me in an affable manner, doing me the honour of believing me not to be a Parisian.

— ‘Πόσα (pósa: how much)?’ I said, choosing some trifle.

— ‘Δέκα δράγμαι (déka drágmai: ten drachmas)’, he answers me in a classic tone.

Happy the man though, who knows Greek from birth, and does not suspect that he is speaking at this moment like a character from Lucian.

However, the boatman still pursues me on the quay and shouts to me like Charon to Menippus (see Lucian’s ‘Dialogues of the Dead, 2, Charon and Menippus’):

— ‘Ἀπόδος, ὦ κατὰρατε, τὰ πορθμεῖα (apódos, ó katárate, ta porthmeia: pay me, your fare, you rascal!)’

He is not satisfied with half a franc that I gave him; he wants a drachma (ninety centimes): he will not gain even an obol. I answer him valiantly with a few sentences from the Dialogues of the Dead. He withdraws, muttering Aristophanes’ curses.

It seems to me that I am walking about in the midst of a comic-opera. How can one believe in these people in embroidered jackets, and petticoats with deep pleats (fustanella), wearing red bonnets, whose thick silken braid falls to the shoulder, their belts bristling with gleaming weapons, and clad in leggings and slippers! It is the exact same costume as adorns the actors in Pirate Island (‘L’ile des Pirates,’ 1835, music by Rossini, Beethoven et al) or The Siege of Missolonghi (‘Le Dernier Jour de Missolonghi’, by Georges Ozaneaux and Ferdinand Hérold, 1828). Yet everyone passes by without suspecting that they look like an extra, and it is my hideous Parisian clothing alone that sometimes provokes a justifiable burst of hilarity.

Yes, my friends! it is I who am the barbarian, a rude son of the North, and who stands out amidst your motley crowd. Like the Scythian, Anacharsis (see Jean-Jacques Barthélemy’s ‘Voyage du Jeune Anacharsis en Grèce’, 1788) … Oh! I beg pardon, wishing to extricate myself from that tiresome parallel.

But it is the Eastern sun, and not the pale sun of the chandeliers, that lights this pretty town of Chora, whose first appearance produces the effect of an impossible stage-set. I walk amidst full local colour, the sole spectator of an alien scene, where the past is reborn within the envelope of the present.

Behold, a young man with curly hair, who passes by, bearing on his shoulder the bulging skin of a black kid.... You mighty gods! It’s a wineskin, a Homeric wineskin, moist and hairy. The boy smiles at my astonishment, and graciously offers to untie one of the legs of the creature, so as to fill my cup with honeyed Samian wine.

— O young Greek, into what will you pour this nectar? I have no cup, I will confess.

— ‘Πίθι (pithi: a drink)?’ he asks, taking from his belt a truncated horn trimmed with copper and causing a stream of foamy liquid to spurt from the kid’s foot.

I swallow it all without grimacing and without regurgitating, out of respect for the soil of ancient Scyros, that the feet of young Achilles trod (see Gérard’s later correction, Syros is not to be confused with Scyros).

I can say today that it smelled horribly of leather, molasses and resin; but surely this was the same wine that was drunk at Peleus’ wedding, and I bless the gods who gifted me the stomach of a Lapith, and the legs of a Centaur.

These latter were not useless to me either in this strange city, built in steps, and divided into two towns, one bordering the sea (the new one), and the other (the old town) crowning the top of a sugar-loaf mountain, which one must ascend two thirds of before arriving there.

May the chaste Pierides prevent me from speaking ill, today, of the craggy mountains of Greece! They are the powerful bones of this ancient mother (the mother of us all) that we tread with feeble steps. This rare lawn where the sad anemone blooms, finding barely enough soil to spread a remnant of its yellowed mantle thereon. O Muses! O Cybele!... What! Not even brushwood, or a tuft of tall grass signalling some nearby spring!... Alas! I forgot that, in the new town which I have just traversed, pure water is sold by the glass, and I have only met with a single wine-bearer.

So here I am at last, in the countryside, between the two towns. The one, on the shore, displaying its luxurious favours for merchants and sailors; its half-Turkish bazaar, its shipyards, its stores and new factories, its main street lined with haberdashers, tailors and booksellers; and, on the left, a whole district of merchants, bankers, and shipowners, whose houses, already splendid, climb to gradually cover the rock, which hangs sheer above a deep blue sea. The other, which, seen from the port, seems to form the point of a pyramidal construction, now appears detached from its apparent base, by a wide fold of land which must be crossed before reaching the mountain, whose summit it strangely caps.

Who does not remember Jonathan Swift’s fine city of Laputa, suspended in the air by magical force and landing, from time to time, somewhere on earth to stock up on what it lacks. This is the exact portrait of old Syros, minus the power of locomotion. It is of she who ‘from level to level, climbs the clouds,’ with her twenty rows of small flat-roofed houses, which diminish regularly until they reach the Cathedral of Saint George, the last level of this pyramidal peak. Two other higher mountains rise behind this one in a double peak, between which stands out, from afar, that pyramid of whitewashed houses. It makes for a most particular sight.

Chapter 20: The Cathedral of Saint George

We climb for a long time through the crops; small dry stone walls indicate the boundary of the fields; then the climb becomes steeper and we walk over bare rock; finally we reach the first houses; the narrow street spirals towards the top of the mountain; poverty-stricken shops, ground-floor rooms in which women converse or spin, groups of children with hoarse voices and charming features, running here and there or playing on the thresholds of their hovels, young girls hastily veiling themselves, quite fearful at seeing something as rare as a passer-by in the street; suckling-pigs and poultry, disturbed in their peaceful possession of the public road, and fleeing back towards the interiors of the houses; here and there enormous matrons summoning or hiding their children to protect them from the evil eye: such is the common spectacle which meets the stranger everywhere.

Stranger! Am I really so in this land of the past? Ah no, already kindly voices have saluted my mode of dress, of which just now I was ashamed.

‘Καθολικός! (Katholikós, a Catholic) That is the word the children repeat, around me.

And I am led with great shouts towards the Cathedral of Saint George, which dominates the town and the mountain. Catholic! Indeed, my friends; a Catholic, truly I had forgotten. I tried to think, then, of the immortal gods, who have inspired so many noble geniuses, so many elevated virtues! I evoked, from the empty sea and the arid soil, the ghostly laughing divinities that their fathers had dreamed of, and said to myself, viewing the sadness and nakedness of this archipelago of the Cyclades, these bare coasts, these inhospitable bays, that the curse of Neptune has struck neglectful Greece.... The green naiad has died, exhausted, in her cave; the gods of the groves have disappeared from this shadowless earth; and all those divine animations of matter have withdrawn little by little, like life itself from an icy body. Oh! Have none understood that last cry, uttered by a dying world, when pallid seamen reported that, passing the coast of Thessaly, at night, they had heard a great voice crying: ‘Pan is dead!’ Dead, oh, the companion of simple and joyful spirits, the god who blessed the fruitful marriage of humankind to the Earth! He is dead, he through whom all was brought to life! Dead, without a struggle, at the foot of profaned Olympus, dead as only a god can die, for want of incense and homage; struck to the heart as a father is by ingratitude and forgetfulness! Silence now, children, let me contemplate this ancient stone, sealed by chance in the wall of the terrace which supports your church, and which recalls his cult; let me touch its sculpted features, depicting a cittern, cymbals, and, at the centre, a cup crowned with ivy; it’s a remnant of his rustic altar, which your ancestors surrounded, with fervour, in times when nature smiled on human effort, when Syros was Homer’s Syrie....

Here, I close a somewhat lengthy paragraph to provide a helpful parenthesis. I previously confused Syros with Scyros. For want of a c, this amiable island must lose much in my esteem; for it is decidedly elsewhere that young Achilles was raised among the daughters of Lycomedes, and, if I believe my guide-book, Syros can boast only of having given birth to Pherecydes, Pythagoras’ master and the inventor of the compass.... How learned these guide-books are!

The beadle was sent for, to open the church; and I sit down, while waiting, on the edge of the terrace, in the middle of a troop of children, brown and blond as everywhere, but beautiful as those of ancient marble, with eyes that marble fails to render, and whose agitated brilliance cannot be fixed in a painting. Little girls dressed like tiny Sultanas, with turbans of braided hair, boys dressed like girls, thanks to the pleated Greek skirt, and the long braid of hair down to the shoulders, these are what Syros ever produces, in the absence of flowers and shrubs; Youth is still smiling, on the barest of soils.... Is there, in their language, some naive song corresponding to that roundel of our young girls, which mourns the deserted woods, and the felled laurels? But Syros would reply that her woods furrowed the waters, her laurels were exhausted in crowning the brows of her sailors!... For have you not also been a great nest of pirates, O virtuous rock, twice Catholic, Roman on the hill above, and Greek on the shore: are you not always the seat of usurers?

My guide-book adds that most of the rich merchants in the lower town made their fortune during the War of Independence by trading as follows: their ships, under the Turkish flag, seized those that Europe sent that brought money and arms to aid Greece; then, under the Greek flag, they resold those arms, and provisions, to their brothers in the Morea, or on Chios; as for the money, they did not hold it, but lent it, under secure pledge, to the Independence cause, and thus reconciled their habits as usurers and pirates with their duties as Hellenes. It must also be said that the upper town customarily supported the Turks because of its Romanised Christianity. General Charles Nicolas Fabvier, landing on Syros, and believing himself among Orthodox Greeks, was nearly assassinated there.... Perhaps they would have sold the body of that illustrious warrior to a grateful Greece as well.

What! Might your fathers have done that, O beautiful children with hair of ebony and gold, who watch in admiration as I leaf through this guide-book which is more or less accurate, while waiting for the beadle? No! I prefer to believe in your gentle eyes; what your fathers are reproached for must rather be attributed to that gathering of foreigners without name, religion, or country, who still swarm in the harbour of Syros, the crossroads of the Archipelago. And, moreover, there is the calmness of your deserted streets, the sense of order, the poverty.... Here comes the beadle, bearing the keys of the Cathedral of St. George. Let us enter: no ... I know what’s there.

A modest colonnade, a country-parish altar, a few old worthless paintings, a Saint George on a gold background, overcoming the one who always arises once more ... is it worth the risk of a chill gained beneath its damp vaults, between these massive walls that burden the ruins of a temple of the abolished gods? No! Not for one day I spend in Greece, do I wish to brave the wrath of Apollo! I will not expose my body, heated by the divine fires that have survived the days of its glory, to the shade. Away, breath of the tomb!

All the more so since there is, in the guide-book, a passage that struck me deeply: ‘Before reaching Delphi, one finds, on the road to Livadeia, several ancient tombs. One of them, whose entrance takes the form of a colossal portal, was split by an earthquake, and from the crack emerges the trunk of a wild laurel.’ Edward Dodwell (author of ‘A Classical and Topographical Tour through Greece’ published 1819) tells me that there is a tradition in the country that at the moment of Christ’s death, a priest of Apollo, offering a sacrifice in this very place, halted suddenly, and cried out that a new god was born, whose power would equal that of Apollo, but who would nevertheless end up yielding to him. Scarcely had he uttered this blasphemy, when the rock split, and he fell dead, struck by an invisible hand.

And I, child of a doubting century, did I not do well in hesitating to cross the threshold, and remaining instead on the terrace, to contemplate nearby Tinos, Naxos, Paros, and Mykonos, scattered on the waters, and further away that low and deserted coastline, still visible at the sky’s edge, which is Delos, once the island of Apollo!...

Chapter 21: The Windmills of Syros

I need say little more about Greece. Merely a word or two. I have brought the reader with me to the summit of that sugar-loaf mountain crowned with houses, which I compared to the suspended city of Laputa — the reader must be brought to the shore again; otherwise, his or her mind will remain perched forever on the terrace of that church of the great Saint George, that overlooks the old city of Syris. I know of nothing sadder than an uncompleted journey — I suffered more than anyone from the death of poor Victor Jacquemont (the geologist and botanist, who died of cholera in Mumbai, in 1832) who left me with one foot in the air poised on some summit of the Himalayas, and it vexes me greatly every time I think of India. Good Yorick himself (Laurence Sterne) did not hesitate to condemn us, voluntarily, to the eternal and painful curiosity of knowing what happened between that Reverend personage and the Piedmontese lady in the famous two-bedded room of which we know (see Sterne’s ‘Sentimental Journey: The Case of Delicacy’. ‘Parson Yorick’ was Sterne’s pseudonym in the book). This is among the petty miseries which seem so great in human life: — it seems one must deal with those unhappy enchanters who draw you into a magical conspiracy, from which they no longer know how to extricate you, and who leave you there, transformed — into what? — into a question mark.

What restrained me, it must be said, was the desire to tell – and the fear of not being able to properly relate – a certain adventure that happened to me, inside one of those six-sailed windmills that so strangely decorate the heights of all the Greek islands, while I was descending the mountain.

A windmill, with six sails that beat the air, joyfully, like the long membranous wings of cicadas, spoils the perspective much less than our dreadful mills of Picardy; yet it cuts a mediocre figure beside the solemn ruins of antiquity. Is it not sad to think that the coast of Delos is covered with them? Windmills grant the only shade in these sterile places, formerly covered with sacred woods. Descending from old Syros, to Ermoupoli, the new Syra, built on the seashore on the ruins of ancient Hermopolis, I had to rest in the shadow of these windmills, the ground floor of which is generally a tavern. There are tables in front of the door, and you are served, in bottles wrapped in straw, a little reddish wine that smells of tar and leather. An old woman approached the table where I was sitting and said:

— ‘Κοκόνιτζα! Καλὶ!’ (Kokónitza! Good! ...)

It is already known that modern Greek is much closer to ancient Greek than is thought. This is true to the point that the newspapers, most of them written in classical Greek, are nevertheless understood by everyone.... I do not present myself as a Hellenist of the first order; but I recognised, in the second word, that it was a question of something ‘good’. As for the noun Κοκόνιτζα, I searched in vain for its root in my memory, furnished only with the classical stanzas of Claude Lancelot (author of that etymological dictionary ‘Le Jardin des Racines Grecques’).

— After all, I said to myself, this woman recognises in me a foreigner; perhaps she wants to show me some ruin, to direct me to some curiosity. Perhaps she has been entrusted with some daring message, for we are in the Levant, a realm of adventures.

As she motioned for me to follow her, I did so. She led me further on, to another windmill. It was no longer a tavern: a sort of wild band of seven or eight ill-dressed rogues filled the interior of the low room. Some were sleeping, others were playing knucklebones. There was nothing gracious about the scene within. The old woman invited me to enter. Understanding more or less the purpose of the establishment, I pretended to wish to regain the honest tavern where the old woman had encountered me. She dragged me back, by the hand, shouting again: -

— ‘Κοκόνιτζα! Κοκόνιτζα!’

On my reluctance to enter, she made a sign to me to stay where I was.

She walked away a few steps, and lay in wait behind a hedge of cacti that bordered a path leading to the town. Country girls passed by, from time to time, bearing large copper vases; on their hips, when they were empty, on their heads, when they were full. They were going to the spring located nearby, or returning from it. I have since learned that it was the only spring on the island. Suddenly the old woman began to whistle, one of the peasant women stopped and rushed through one of the openings in the hedge. I understood at once the meaning of the word Κοκόνιτζα! It was a kind of hunting call for summoning young girls. The old woman whistled ... the same tune no doubt that the ancient serpent whistled under the tree of evil ... and a poor peasant girl had just been caught by the decoy.

In the Greek isles, all the women when outside are veiled as if they were in a Turkish country. I will admit that I was not sorry, on the only day that I spent in Greece, to see at least one female face. And yet, was not this simple traveller’s curiosity already a sort of acceptance of that dreadful old woman’s intrigues? The young woman seemed trembling and uncertain; perhaps it was the first time that she had yielded to the temptation lurking behind that fatal hedge! The old woman lifted the poor girl’s blue veil. I saw a pale, regular face, with somewhat wild eyes; two large braids of black hair were coiled about her head like a turban. There was nothing there of the dangerous charm of the ancient hetaira (courtesan); moreover, the peasant woman turned every moment with anxiety towards the countryside, saying:

— Ὦ ἀνδρός μου! ὦ ἀνδρός μου! (Oh, my husband! My husband!)

Wretchedness, rather than amorousness, dominated her whole attitude. I confess I gained little merit by resisting the seduction. I took her hand, into which I put two or three drachmas, and made a sign to her that she should go back whence she came.

She seemed to hesitate for a moment; then, putting her hand to her hair, she pulled from between the twisted braids around her head one of those amulets worn by all women in oriental countries, and gave it to me, saying a word that I could not understand.

It was a small fragment of an antique vase or lamp, which she had probably picked up in the fields, wrapped in a piece of red paper, and on which I thought I could make out a small figure of a spirit mounted on a winged chariot between two serpents. However, the relief is so crude that one could see in it anything one wished.... Let us hope it will bring me luck on my travels.

A sad spectacle, in short, is the corruption of manners seen in oriental countries whereby a false spirit of morality has suppressed those joyful and carefree courtesans depicted by the poets and philosophers — on the one hand, the passion of Corydon (the rustic youth in Virgil’s ‘Eclogues’) succeeds to that of Alcibiades — on the other, the entire sex is depraved so as to avoid perhaps a lesser evil; the stain widens without being erased; poverty makes a furtive gain which corrupts it without enriching. It is no longer even the pale image of love; it is only its fatal and painful shadow. — One may see how far this social prejudice extends, so clumsy and so impotent at the same time. The Greeks love the theatre, as ever; there are theatres in the smallest towns. Only, all the women’s roles are played by men.

On my way back down to the port, I saw posters bearing the title of a tragedy, Marcos Botzaris, by Panagiotis Soutsos, followed by a ballet, all printed in Italian for the convenience of foreigners. After dining at the Grand Hôtel d’Angleterre, in a large room decorated with ‘character’ wallpaper, I was guided to the Casino, where the performance was taking place. Before entering, the attendees long cherry-wood pipes were deposited at a sort of pipe office: the locals no longer smoke in the theatre so as not to inconvenience the English tourists who rent the best boxes. There were hardly any men there, except for a few women who were strangers to the locality. I waited impatiently for the curtain to rise to assess the actors’ mode of pronunciation. The play began with an exposition scene between Botzaris and a Palikari (a young Greek who fought the Ottoman Turks) his confidant. Their emphatic guttural delivery would have hidden the meaning of the lines from me, even if I had been learned enough to understand them; moreover, the Greeks pronounce eta as an i, theta as an English th, beta as a v, upsilon as a y, and so on. It is probable that this was indeed the ancient pronunciation, but the University teaches otherwise.

In the second act, I saw Moustai Pacha (the Pacha of Scutari, Albania), in the midst of the women of his seraglio, who were simply men dressed as odalisques; as I said, women are not allowed to appear on the stage in Greece. What morality! Moustai Pacha had his confidant beside him, like a Greek hero; he seemed as Turkish as the fierce Acomat presented by Saint-Aulaire (the author and diplomat Charles de Beaupoil. ‘Acomat’ is a character in Racine’s play ‘Bazajet’; Saint Aulaire encouraged Rachel’s acting career). As I followed the play, I gradually came to understand that Marcos Botzaris was a modern Leonidas, repeating with three hundred Palikaris, the last stand of the three hundred Spartans, at Thermopylae. This Hellenic drama was warmly applauded; after developing according to classical rules, it ended with rifle shots.

On returning to the steamer, I enjoyed the unique spectacle of that pyramidal city of Syros illuminated to its highest houses. It was truly Babylonian, as the English would say.

I left the Austrian vessel at Syros, and embarked on the Leonidas (on January 11th, 1843), a French ship leaving for Alexandria, which involved a three-day crossing.

Egypt is a vast tomb; that is the impression it made on me when I landed on the beach in Alexandria, which, with its ruins and mounds, offered nothing but tombs, scattered over an ashen landscape, to the eye.

Shades, draped in bluish shrouds, moved among the debris. I visited Pompey’s Pillar and Cleopatra’s Baths. The Mahmoudia promenade, with its evergreen palm trees, alone recalled living Nature .... I shall not describe the large, wholly-European square formed by the palaces housing consulates, the mansions containing bankers, the ruined Byzantine churches, nor the modern buildings of the Pasha of Egypt, bordered by gardens that appear like greenhouses. I would have preferred monuments of Greek antiquity; but all that is destroyed, razed, unrecognisable.

I embark this evening, on the Mahmoudia canal, in order to travel from Alexandria to Al-Atf village (later incorporated in the city of El Mahmoudia, on the Nile), then I will board a sail-boat and ascend the river as far as Cairo: a journey of a hundred and fifty miles or more, in all, that takes six days or so.

The End of Part III of Gerard de Nerval’s ‘Travels in the Near East’