Théophile Gautier

Travels in Spain (Voyage en Espagne, 1840)

Parts X to XII - Toledo, Granada, and Málaga

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2024 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Part X: Toledo – The Alcazar – The Cathedral – The Gregorian Rite and the Mozarabic Rite – Our Lady of Toledo – San Juan de Los Reyes – The Synagogue – The Galiana Palace, Charlemagne and Bradamant – Florinda’s Dwarf – The Cave of Hercules – The Cardinal’s Hospital – Toledo Blades

- Part XI: A Festival Procession in Madrd – Aranjuez – A Patio – The Countryside of Ocaña – Tembleque and its Garters – A Night in Manzanares – The Knives of Santa Cruz de Mudela – The Puerto de los Perros – The Colony of La Carolina – Bailén – Jaén, its Cathedral and its Dandies – Granada – The Alameda – The Alhambra – The Generalife – The Albaicín – Life in Granada – The Gitanos – The Charterhouse – Santo Domingo – An Ascent of Mulhacen

- Part XII: The Thieves and Pirates of Andalusia – Alhama de Granada – Málaga – Students on Tour – A Bullfight – Montes – The Theatre

Part X: Toledo – The Alcazar – The Cathedral – The Gregorian Rite and the Mozarabic Rite – Our Lady of Toledo – San Juan de Los Reyes – The Synagogue – The Galiana Palace, Charlemagne and Bradamant – Florinda’s Dwarf – The Cave of Hercules – The Cardinal’s Hospital – Toledo Blades

We had exhausted the curiosities of Madrid, we had viewed the palace, the Armeria, the Buen-Retiro, the museum and the academy of art, the Teatro del Principe, and the Plaza de Toros; we had walked the Prado from the fountain of Cybele to the fountain of Neptune, and a slight feeling of ennui began to invade us. So, despite a temperature of thirty degrees Centigrade and all kinds of horrifying stories about rebels and rateros, we set off boldly for Toledo, the city of fine swords and Romantic daggers.

Toledo is one of the oldest cities not only in Spain, but in the entire world, if the chroniclers are to be believed. The most conservative place the date of its foundation before the flood (why not under the pre-Adamite kings, a few years before the creation of the world?) Some attribute the honour of having laid its first stone to Tubal, others to the Greeks; some to Telmon and Brutus, Roman consuls; others to the Jews, who entered Spain with Nebuchadnezzar, relying on the etymology of Toledo, which comes from Toledoth, a Hebrew word meaning generations, since the twelve tribes contributed to building and populating it.

Be that as it may, Toledo is certainly an admirable old town, located a dozen leagues from Madrid, Spanish leagues I mean, which are longer than a twelve-column newspaper article, or a penniless day, the two longest things I know of. One travels there by one-horse gig, or in a small stagecoach which leaves twice a week; we preferred the latter as being safer, since beyond the mountains, as formerly in France, one draws up one’s will before the briefest journey. The dread of brigands must be exaggerated, for, in a very long pilgrimage through those provinces with the reputation of being the most dangerous, we never saw anything that could justify such a degree of panic. However, the fear adds greatly to the pleasure; it keeps you alert and protects you from boredom: you are performing a heroic action, displaying superhuman courage; the anxious and fearful look of those who remain behind enhances you in your own eyes. A trip in a stagecoach, the most ordinary thing in the world, becomes an adventure, an expedition; you are leaving, it is true, but you are unsure whether you will arrive or return. That is something, in a civilization as modern as ours, in this prosaic and misguided year of 1840.

We left Madrid by the Toledo gate and bridge, decorated with stone vases exuding flames, scrolls, statues, and foliage, all in mediocre taste, and yet producing something of a majestic effect; we left behind on the right the village of Carabanchel, where Hugo’s Ruy Blas sought that little blue German flower for Maria de Neubourg. He would not find today the least vergissmeinnicht (forget-me-not) in this hamlet of cork-oak, built on pumice stone. One enters, by a vile path, onto an interminable dusty plain, covered entirely with wheat and rye, the pale yellow of which further adds to the monotony of the landscape. A few crosses auguring ill, which here and there spread their fleshless arms, a few bell-tower spires which reveal an insignificant village in the distance, or a dry ravine bed bridged by a stone arch, are the only features which present themselves. From time to time, we met a peasant on his mule, rifle at his side; a muchacho chasing two or three donkeys in front of him, loaded with jars or chopped straw held by cords; or a woman, poor, haggard and sunburnt, dragging a savage-looking brat, and that was all.

As we advanced, the landscape became more arid and more desolate, and it was not without a feeling of inner satisfaction that we saw, on a drystone bridge, the five green-clad huntsmen on horseback who were to serve as our escort, since an escort is needed when travelling from Madrid to Toledo. Might one not think one was amid the plains of Algeria, and that Madrid was surrounded by its own Mitidja populated by Bedouins?

We halted for lunch at Illescas, a town or a village, I am not sure which, where we saw some traces of ancient Moorish buildings, and whose houses have windows adorned with complex ironwork and surmounted by crosses.

Lunch consisted of soup with garlic, eggs, the inevitable tomato tortilla, toasted almonds, and oranges, all washed down with a Val-de-Penas wine, fairly good, though thick enough to cut with a knife, bitter with resin, and the colour of blackberry syrup. Its cuisine is not Spain’s best offering, and the inns have not improved appreciably since Don Quixote; those descriptions of omelettes full of feathers, tough hake, rancid oil, and chickpeas that could serve as bullets, are still most true to life; I know not, for example, where one might find today the fine chickens and monstrous geese served at Camacho’s wedding.

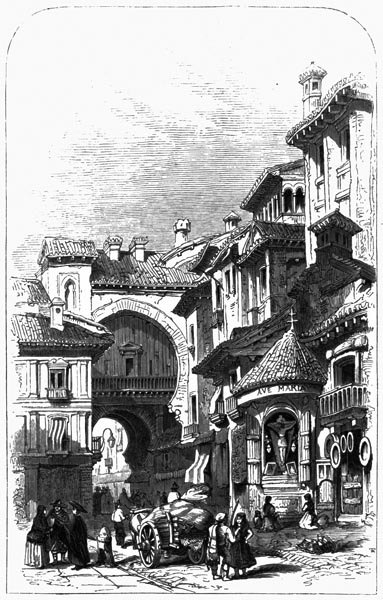

From Illescas, the terrain becomes more rugged, and results in an even more abominable road; nothing but potholes and death-traps. Though this did not prevent us from travelling at full speed; the Spanish postilions are like Morlach coachmen, they care little for what sits behind them, and as long as they arrive, even if only with an axle and the little front wheels, they are satisfied. However, we reached our destination without incident, in the midst of the cloud of dust raised by our mules, and the huntsmen’s horses, and we entered Toledo, panting with curiosity and thirst, through a magnificent gateway in the Arab style, with an elegantly curved arch, granite pillars topped with stone balls, and decorated with verses from the Koran. This portal is called the Puerta del Sol; it is red, sun-burnt, and candied in hue, like a Portuguese orange, and stands out admirably against the limpidity of a lapis-lazuli sky. In our foggy climate, we can barely gain an idea of that violence of colour, and harshness of contour, and the paintings that recall it always seem exaggerated.

After passing the Puerta del Sol, you find yourself on a sort of terrace from which you enjoy an extensive view; there is the Vega dappled and striped with trees and crops which owe their freshness to the irrigation system introduced by the Moors. The Tagus, crossed by the San Martín bridge and the Alcántara bridge, flows swiftly with yellowish waves, and enfolds the city almost entirely. At the foot of the terrace, the brown and shiny roofs of the houses, and the bell-towers of the monasteries and churches, their green and white earthenware tiles arranged in a checkerboard pattern, float before the eyes; beyond, one sees red hills and bare escarpments on the horizon. The view is singular in that it is entirely deprived of that ambient mist in the air, which with us, always bathes the broadest perspectives; the transparent atmosphere leaves the contours all their sharpness, and allows one to discern the smallest detail at considerable distance.

Having retrieved our luggage, there was nothing more urgent than to seek out a fonda or parador of some kind, since the eggs we partook of in Illescas already seemed far away. We were led, through alleys so narrow that two loaded donkeys could not have passed abreast, to the Fonda del Caballero, one of the most comfortable in the city. There, collecting the little Spanish that we knew, and with the help of pathetic mime, we managed to make the hostess, a gentle and charming woman, with the most interesting and distinguished air, comprehend that we were dying of hunger, something which always seemed to greatly astonish the natives of the country, who live on air and sun, in the highly economic fashion of chameleons.

The whole kitchen was put to work; about the fire, countless little pots were set, in which the spicy stews of the Spanish cuisine are distilled and sublimated, and we were promised dinner in an hour. We took advantage of that hour to examine the fonda in more detail.

It was a fine building, no doubt some old hotel, its interior courtyard paved with coloured marble forming a mosaic, and decorated with white marble wells, and troughs lined with earthenware tiles for washing the glasses and bowls.

The courtyard is called a patio; it is usually surrounded by columns and arcades, with a fountain in the middle. A canvas tendido (awning) which is folded up in the evening to let in the cool night air, serves as the ceiling for this sort of inside-out living room. All around, at the height of the first floor, there is an elegantly-worked iron balcony, onto which the windows and doors of the rooms open, rooms which one enters only to dress, dine, or take a nap. The rest of the time, we remained in this courtyard-salon, which was furnished with paintings, chairs, sofas, a piano, and embellished with flower-pots and orange trees in tubs.

Our inspection was barely over when Celestina (a strange and whimsical serving girl) came to tell us, while humming a song, that dinner was served. The meal was quite passable: cutlets, eggs with tomatoes, chicken fried in oil, and trout from the Tagus, accompanied by a bottle of Peralta, a thick sweet mulled wine, flavoured with a certain hint of muscat which is not unpleasant.

The meal over, we wandered into the city, preceded by our guide, a barber by trade, and an aid to tourists in his spare time.

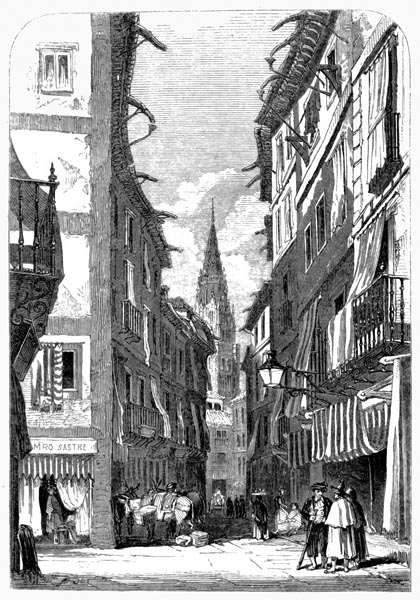

The Toledo streets are extremely narrow; one could link hands from one window to its opposite, and nothing would be easier than to climb over the balconies, if those very fine grilles and elegant bars of rich ironwork, with which they are so lavish beyond the mountains, did not keep such good order by preventing aerial familiarities. The lack of width would make all those partisans of civilisation cry aloud, who dream only of immense squares, vast market-places, wide streets and other more or less progressive embellishments; yet nothing is more reasonable than narrow streets in a torrid climate, and the architects and engineers who are cutting such large gaps in the massif on which Algiers stands will shortly realise it is so. At the bottom of these narrow passages, conveniently set between blocks and islands of houses, one enjoys delightful freshness and shade, and one moves around under cover of the ramifications and porosities of this human coral-reef called a city; the ladles full of molten lead that Phoebus-Apollo pours from the sky at midday scarcely reach you; the projecting roofs serve as a parasol.

Street in Toledo

If, by misfortune, you are forced to pass through some plazuela (little square) or calle ancha (wide street) exposed to the scorching rays of the sun, you soon appreciate the wisdom of former days, when architects chose not to sacrifice everything to some foolish idea of regularity; the paving slabs are like those red-hot sheet-metal plates on which showmen make geese and turkeys dance the krakowiak; the wretched dogs, lacking shoes or alpargatas, cross them at the run, uttering plaintive howls. If you raise a door-knocker, you burn your fingers; you can feel your brain boiling in your skull like a cooking pot on the fire; your nose turns crimson, your hands burn, you evaporate in sweat. This is all that large squares and wide streets achieve. Anyone who has spent between noon and two o’clock in Madrid’s Calle de Alcalá will agree with me. Moreover, to win spacious streets, the houses are reduced in size, while the opposite seems more reasonable. It is to be understood that this observation only applies to hot countries, where it never rains, where mud is seldom found, and vehicles extremely rare. Narrow streets in our rainy climate would be abominable cesspools. In Spain, women go about on foot in shoes of black satin, and make long journeys thus; for which I admire them, especially in Toledo, where the pavements are composed of small sharp brightly-polished stones, which seem to have been carefully placed with the cutting edge uppermost; but the women’s small arched and muscular feet prove as tough as the hooves of a gazelle, and they flit about as gaily as anything on diamond-cut pavements which makes the traveller accustomed to the softness of asphalt from Seyssel on the Rhône, and the elasticity of Antoine Polonceau’s bitumen, cry out in anguish.

Houses in Toledo present a severe and imposing appearance; they possess few windows on the facade, and those are usually barred. The doors, decorated with bluish-granite pillars topped with stone balls, a decoration which is frequently reproduced, have an air of solidity and thickness added to by constellations of enormous nails. The houses have the air, at one and the same time, of monastery, prison, fortress, and to some extent harem after the Moors passed through. Some of the residences, in bizarre contrast, are decorated and painted externally, either in fresco or tempera, with imitation bas-reliefs, grisailles, flowers, rocailles and garlands, with vases, medallions, cupids, and all the mythological jumble of the last century. These trumeau and pompadour houses produce the strangest, most farcical effect beside their sullen sisters of feudal or Moorish origin.

We were guided to the Alcázar, located like an acropolis on the highest point of the city, through an inextricable network of small alleys, where my companion and I walked one behind the other, like the geese in the ballad, for lack of room to link arms, and we entered it after some discussion, since the first reaction of those to whom one addresses oneself is always a refusal, whatever the request may be. ‘Come back this evening; or tomorrow; the guard is taking a nap; the keys are lost; you need permission from the governor’: such are the answers one receives at first; but, by exhibiting the sacred peseta, or the gleaming duro (a five-peseta coin) in case of extreme difficulties, we always ended up forcing the issue.

The Alcázar, built on the ruins of the ancient Moorish palace, is today itself in ruins; it looks like one of those marvellous architectural dreams that Piranesi pursued in his magnificent etchings; it is by Alonso de Covarrubias, a little-known architect and sculptor, but far superior to the heavy and ponderous Juan de Herrera, whose fame is much overrated.

The facade, flowery and ornamented with the purest Renaissance arabesques, is a masterpiece of elegance and nobility. The ardent Spanish sun, which reddens marble and gives stone a saffron hue, has coated it with a dressing of rich and vigorous colour, very different from the leprous black with which the centuries encrust our old buildings. According to the expression of a great poet, Time has passed his thumb, thoughtfully, over the edges of the marble, over the too-rigid contours, and given to this sculpture, already so supple and so soft, a supreme polish and final completion. I especially remember a large staircase of magical elegance, with columns, banisters and marble steps already half-broken, leading to a door which opened onto a void, since that part of the building had collapsed. This admirable staircase, which a king could traverse, and which leads to nothing, has about it something prestigious and singular.

The Alcázar is built on a large esplanade surrounded by crenellated ramparts in oriental fashion, from the top of which one discovers an immense view, a truly magical panorama: here the cathedral thrusts its disproportionate spire into the heart of the sky; further away, in a ray of sunlight, shines the monastery of San Juan de los Reyes; the Alcántara bridge, with its tower-shaped gateway, spans the Tagus in bold arches; the Artificio de Juanelo (Juanelo Turriano’s hydraulic water-lift) clutters the river with its storied red-brick arcades which one might mistake for the remains of Roman constructions; and the massive towers of the Castillo de Cervantes (this Cervantes has nothing in common with the author of Don Quixote), perched on the rough and misshapen rocks which border the river, add one more set of jagged features to a horizon already cut so deeply by the ridged vertebrae of the mountains.

An admirable sunset completed the picture: the sky, through imperceptible graduations, went from the brightest red to orange, then to pale lemon, to arrive at a strange blue, the colour of greenish turquoise, which blended, in the west, with the lilac hues of night, whose shadow was already cooling that hemisphere.

Leaning on the corner of a niche, and looking down, in a bird’s eye view, at this city where I knew no one, and where my name was completely unknown, I fell into a deep meditation. Faced with all these objects, all these forms, which I saw now and probably would never see again, I was possessed by doubt of my own identity, I felt so absent from myself, transported so far from my own sphere, that everything seemed a hallucination, a strange dream, from which I was about to wake with a start to the sharp, quavering sound of vaudeville music rising from beyond the edge of some theatre-box. By one of those leaps of thought so common in reverie, I reflected on what my friends might be doing at that hour; I wondered if they had noticed my absence, and if, by chance, at this very moment, as I was leaning over that niche in the Alcázar of Toledo, my name was fluttering on some beloved and faithful Parisian lips. Apparently, my internal response was not in the affirmative; since, despite the magnificence of the spectacle, I felt my soul invaded by an immeasurable sadness, and yet I was fulfilling the dream of my whole life, I was touching with my fingers one of my most ardently cherished goals: I had spoken enough, during the lovely verdant years of my Romanticism, of my fine blade from Toledo, to be curious to see the place where it was made.

It took nothing less than the suggestion made by my friend that we go for a swim in the Tagus to rouse me from my philosophical meditation. Bathing is so a rare a feature in a country where, in summer, the riverbeds themselves are irrigated with water from the wells, that it made sense not to neglect the opportunity. On the guide’s assertion that the Tagus was a serious river, and possessed enough moisture to yield a cupful or two, we descended in all haste from the Alcázar, in order to take advantage of the daylight, and we headed for the river. After crossing the Plaza de la Constitución (Plaza de Zocodover) lined with houses whose windows, furnished with large esparto-grass blinds rolled-up or half-raised above the projecting balconies, gave it a most picturesque look of Venice and the Middle Ages, we passed under a beautiful doorway in the Arab style with a brick arch (El Arco de la Sangre), and arrived, by a steep and abrupt zigzag path snaking along the rocks and walls which serve to enclose Toledo, at the Alcántara bridge, near which there was a suitable place for bathing.

During the journey, night, which succeeds day so swiftly in southern climes, had fallen, and the darkness was complete, which did not prevent us from clawing our way into that estimable river, made famous by Queen Hortense’s languorous Romantic air (‘Fleuve du Tage’), and by the golden sand it bears in its crystal-clear waters according to the poets, the servants, and the travel-guides.

Our bathing over, we ascended again, hastily, so as to return before the doors were closed. We enjoyed a glass of horchata de chufas and iced milk, yielding an exquisite taste and aroma, and were guided back to our fonda.

The plaster of our room, like all Spanish rooms, was whitewashed and covered with those encrusted yellowed pictures, those mystical daubs executed like beer signs, which one meets with so often in the Peninsula, that part of the world which contains the greatest number of bad paintings; which is said without detriment to those that are good.

We determined to fall asleep as soon, and as deeply as possible, in order to wake early, and visit the cathedral the next morning, before the services began.

Toledo’s cathedral is considered, and with good reason, to be one of the finest and, above all, richest in Spain. Its foundation is lost in the mists of time, and, if local authors are to be believed, it goes back to the apostle Santiago, the first bishop of Toledo, who indicated the place to his disciple and successor Elpidius, hermit of Mount Carmel. Elpidius raised a church at the place so designated, invoking Saint Mary and granting it her title, while that divine lady still lived in Jerusalem. ‘Notable felicity! Illustrious coat of arms of the Tolédans! Most excellent trophy of their glories!’ exclaims, in lyrical effusion, the author from whom I extracted these details.

The holy Virgin proved not ungrateful, and, according to the same legend, descended in body and soul in order to visit the church in Toledo, and brought with her own hands to the blessed Saint Ildefonso a beautiful chasuble made of heavenly cloth. ‘See how well this queen repaid us!’ cries our author again. The chasuble still exists, and we see embedded in the wall the stone on which the divine foot was planted, the imprint of which it still retains. An inscription, conceived thus, attests to the miracle:

QUANDO LA REINA DEL CIELO

When Heaven’s Queen,

PUSO LOS PIES EN EL SUELO

set her foot on this floor,

EN ESTA PIEDRA LOS PUSO

it was on this stone it was set

Legend further relates that the Blessed Virgin was so pleased with her statue, found it so well made, so well-proportioned, and so good a likeness, that she kissed it and granted it the gift of working miracles. If the Queen of Angels came down to our churches today, I doubt she would be tempted to thus embrace her image.

More than two hundred of the most serious and honourable authors relate this story, which is as proven, to say the least, as that of the cause of Henri IV’s death; as for myself, I have no difficulty believing in this miracle, and am happy to accept the tale as authentic. The church remained as it was until Eugenius, sixth bishop of Toledo, enlarged and embellished it, as much as his means allowed, under the title of Santa María de Toledo, which it still retains today; but in the year 302, the time of the cruel persecution suffered by Christians under the emperors Diocletian and Maximian, the prefect, Dacian, ordered the temple to be demolished and razed, so that the faithful no longer knew where to ask for and obtain the bread of grace. Three years later, Constantius, father of the great Constantine, having ascended the throne, the persecution ceased, the prelates returned to their seats, and Archbishop Melantius began to rebuild the church, on the same site. Shortly afterwards, around the year 312, Emperor Constantine, having converted to the faith, ordered, among other heroic works to which his Christian zeal impelled him, the repair and construction, at his own expense, in the most sumptuous manner possible, this basilica church of Our Lady of the Assumption of Toledo, which Dacian had destroyed.

Toledo then had as archbishop Patruinus, a learned, well-read man, who enjoyed the friendship of the emperor; this circumstance left him complete freedom to act, and he spared no expense in building a remarkable temple, of great and sumptuous architecture: it was this cathedral, that survived the time of the Goths, was visited by the Virgin, became a mosque during the conquest of Spain, and which, when Toledo was taken by King Alfonso VI, became a church again, the plan of which was carried to Oviedo by the order of the king of Asturias, Alfonso II the Chaste, in order to build, in accordance with that layout, the church of San Salvador of that city, in the year 803. ‘Those who are curious to know the grand and majestic form the cathedral of Toledo possessed at the time when the Queen of Angels descended to it, only have to visit that of Oviedo, and they will be satisfied,’ adds our author. For our part, we very much regret having been unable to grant ourselves that pleasure.

Finally, in the happy reign of Ferdinand III known as the Saint, Don Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada being archbishop of Toledo, the church took on the admirable and magnificent form that we see today, the form, it is said, of the temple of Diana at Ephesus. O naive chronicler! Permit me to believe not a word of it: the temple at Ephesus was no match for the cathedral of Toledo! Archbishop Rodrigo, assisted by the king and the entire court, after saying a pontifical mass, laid the first stone on a Saturday, in the year 1227; the work continued with great enthusiasm until the final touches had been made to it, and it had been brought to the highest degree of perfection that human art could attain.

Forgive the brief historical digression; I am not accustomed to the task, and will return swiftly to my humble role as tourist, guide, and literary daguerreotype.

The exterior of Toledo cathedral is far less rich than that of Burgos: no efflorescence of ornaments, no arabesques, no necklace of statues blossoming about the portals; solid buttresses, clear sharp angles, thick armour of dressed stone, a bell-tower of robust appearance, possessing none of the delicacy of Gothic jeweller’s-work, all this coated in a reddish hue, the colour of toast, or the sunburnt skin of a pilgrim returned from Palestine; the interior, on the other hand, is hollowed out and sculpted like a cave full of stalactites.

The door (Puerto del Reloj) through which we entered is of bronze and bears the following inscription: Antonio Zurreno del arte de Oro y Plata, faciebat esta media puerta (Antonio Zurreno, artist in gold and silver, made this half of the door). The impression one experiences is of the vividly grandiose; the church is divided into the nave and four aisles, two on each side: the nave is of disproportionate height, the aisles seem as if bowing their heads while kneeling as a sign of adoration and respect; eighty-eight pillars, as tall as towers and each composed of sixteen tapered columns joined together, support the enormous mass of the building; a transverse arm cuts the main nave between the choir and the high altar, forming the arms of the cross. All this architecture, a rare merit in Gothic cathedrals which were usually re-built several times, is in the most homogeneous and finished style; the original plan was executed from beginning to end, except for a few side-chapels which in no way conflict with the harmony of the general appearance. Stained-glass rose-windows sparkling with emerald, sapphire and ruby colours, set in stone ribs, produce a soft, mysterious filtered light conducive to religious ecstasy, and, when the sun is over-bright, esparto-grass blinds lowered over the windows maintain a semi-darkness full of cool air, which makes the churches of Spain such favourable places for meditation and prayer.

The main altar or retablo alone could pass for a church; it is an enormous pile of columns, niches, statues, foliage, and arabesques, of which the most minute description could give only a very faint idea; all this architecture, which rises to the vault and curves about the sanctuary, is painted and gilded with unimaginable richness. The tawny and warm tones of the antique gilding complement, in splendour, the glittering threads and rays of light caught in their traverse of the ribs and projections of the ornamentation, producing admirable effects, of the greatest and most picturesque opulence. The paintings, on a gold background, which adorn the panels of this altar equal, in their richness of the colour, the most dazzling Venetian canvases; this union of colour with the severe and almost hieratic forms of the art of the Middle Ages is encountered only very rarely; one might mistake the style of some of these paintings for Giorgione’s finest manner.

Opposite the high altar is placed the choir or silleria, according to Spanish usage; it is formed of three rows of carved, excavated wooden stalls, cut in a marvellous way, with historical, allegorical, and sacred bas-reliefs. Gothic art, on the verge of the Renaissance, produced nothing purer, more perfect, nor better designed. This work, involving a fearful amount of detail, is attributed to the patient chisels of Philippe de Bourgogne and Alonso Berruguete. The archbishop’s stall, set higher than the rest, is in the shape of a throne and marks the centre of the choir; jasper columns, of a brown shiny hue, crown this prodigious carpentry, and on the entablature rise alabaster figures, also by Philippe de Bourgogne and Berruguete, but in a freer and more flowing manner, of admirable elegance in appearance. Enormous bronze desks covered with gigantic missals, large mats of esparto-grass, and two organs of colossal size, placed facing each other, one on the right, the other on the left, complete the decor.

Behind the retablo is the chapel where Don Álvaro de Luna and his wife are buried in two magnificent juxtaposed alabaster tombs; the walls of this chapel are decorated with the arms of that constable, and the scallop shells of the Order of Santiago, of which he was the grand master. Close by, embedded in the vault of that portion of the nave which they here call the trascoro (afterchoir), I noticed a stone with a funeral inscription: that of a noble Toledan, whose pride revolted at the idea that his grave might be trampled on by the feet of people of low rank and doubtful extraction: ‘I prefer my chest not to be trodden by the masses,’ he had said on his deathbed; and, as he bequeathed a great deal of property to the church, his odd whim was satisfied by housing his body in the masonry of the vault where, indeed, no one was likely to step on him.

I shall not attempt to describe the side-chapels one after the other, it would take a whole volume for that: I will content myself with mentioning the tomb of a cardinal, worked with unimaginable delicacy in the Arab manner; the best comparison would be with guipure lace, but on a larger scale, and will arrive, without further delay, at the Mozarabic or Musharabic chapel, both terms being employed, one of the most curious in the cathedral. Before describing this chapel, let me explain what these words Mozarabic chapel mean.

At the time of the Moorish invasion, the inhabitants of Toledo were forced to surrender after a two-year siege; they sought to obtain the most favourable terms for their capitulation, and among the articles agreed was this: namely that six churches would be kept for those Christians who wished to live alongside the ‘barbarians’. The churches were those of San Marcos, San Lucas, San Sebastián, San Torcato, Santa Olalla, and San Justo. By this means, the Christian faith was preserved in the city during the four hundred years that Moorish domination lasted there, and for this reason the faithful Toledans were called Mozarabs, that is to say mixed with the Arabs. During the reign of Alfonso VI, when Toledo was returned to Christian authority, Cardinal Ricardo, the papal legate, wanted to abandon the Mozarabic office in favour of the Gregorian rite, supported in this by the king and by queen Constance, who both preferred the Roman rite. The clergy revolted, amidst a loud outcry; the faithful revealed their indignation, and there was nearly a mutinous popular uprising. The king, dreading the way things were going, and afraid the populace might take them to the last extreme, pacified them as best he could, and proposed to the Toledans this mezzo termine, this singular measure, entirely in the spirit of that age, which was accepted with enthusiasm on both sides: the supporters of the Gregorian rite and the Mozarabic rite were each to choose a champion and have them fight one another, so that God would decide in which manner and rite he preferred to be praised. Indeed, if ever God’s judgment were acceptable it must certainly be so in regard to liturgy.

The champion of the Mozarabs was one Don Ruiz de La Matanza; the day dawned; La Vega was chosen as the location for the fight. The victory remained uncertain for some time, but in the end Don Ruiz had the advantage and emerged victorious from the lists, to cries of delight from the Toledans, who, weeping with joy and throwing their caps in the air, entered the churches to kneel and return thanks to God. The king, queen, and court were most upset at this triumph. Realising, somewhat late, that it was an impious, reckless and cruel thing to have a theological question resolved by bloody combat, they claimed that only a miracle could decide the matter, and proposed a new test, which the Toledans, confident in the excellence of their ritual, were willing to accept. The test consisted, after a general fast and prayers in all the churches, of placing on a lighted pyre a book containing the text of the Roman liturgy, and another of the Toledan liturgy; the one which survived the flames without being burned would be deemed the best and most pleasing to God.

The test was carried out, point by point. A pyre of dry, highly-inflammable wood was erected on Zocodover Square, which, since it was created, had never seen such an influx of spectators; the two breviaries were thrown into the fire, each party raising their eyes and arms to heaven, and praying to God for the liturgy in which they preferred to serve him. The Roman ritual was rejected, the leaves scattered by the violence of the fire, and emerged from the ordeal intact, but a little scorched. The Toledan remained majestically in the midst of the flame, in the place where it had fallen, without stirring and without receiving any damage. Some enthusiastic Mozarabs even claim that the Roman missal was entirely consumed. The king, the queen and Cardinal Ricardo, the Papal legate, were scarcely content, but there was no path of retreat. The Mozarabic rite was therefore preserved and followed with ardour for many years by the Mozarabs, their children, and grandchildren; but, in the end, understanding of the text was lost, and no one remained capable of speaking or comprehending the office, the object of such lively dispute. Don Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, archbishop of Toledo, not wanting to let such a memorable rite fall into disuse, founded a Mozarabic chapel within the cathedral, had the rituals, which were in Gothic characters, translated and printed in ordinary letters, and instituted priests especially responsible for uttering this office.

The Mozarabic chapel, which still survives today, is decorated with Gothic frescoes of the highest interest: their subjects are battles between the Toledans and the Moors; the conservation is perfect, the colours as vivid as if the painting had been completed yesterday; an archaeologist might find from them a thousand intriguing items of information as regards weapons, costumes, equipment, and architecture, since the main fresco represents a view of ancient Toledo, which must have proved highly accurate. In the side frescoes the ships which brought the Arabs to Spain are painted in great detail; a professional seagoer might again draw useful information from them concerning the complex history of the navy in the Middle Ages. The coat of arms of Toledo, five sable stars on a field argent, is repeated in several places in this low-vaulted chapel, barred in the Spanish fashion by a gate of fine workmanship.

The chapel of the Virgin, entirely covered with porphyry, jasper, yellow and purple breccia of an admirable polish, is of a richness which exceeds the splendours of the Thousand and One Nights; many relics are kept there, including a shrine donated by Saint Louis, which contains a fragment of the true cross.

To catch our breath, we will, if you please, take a walk in the cloister, which frames with elegant and severe arcades beautiful masses of vegetation to which the church’s shade grants freshness, despite the consuming ardour of the season; all the walls of this cloister are covered with immense frescoes, in the style of the Van Loo family, by a painter named Francisco Bayeu. These compositions, simply arranged and pleasantly coloured, are out of keeping with the style of the building, and undoubtedly replaced older paintings which had deteriorated over the centuries, or had been found too Gothic in style by people of good taste in those days. A cloister beside a church is well-sited; it happily allows a transition from the tranquility of the sanctuary to the hustle and bustle of the city. One can walk there, dream, and reflect, without however being required to follow the prayers and ceremonies of worship; Catholics enter the temple, Christians more often linger in the cloister. This state of mind was understood by the Catholics, such skilful psychologists. In religious countries, the cathedral is the most highly-decorated, the richest, the most gilded, the most ornate of places; it is there that the shade is coolest, and the feeling of peace deepest; the music is better there than in the theatre, and the pomp of its spectacle has no rival. It is the central point, the place that attracts all, much like the Opéra in Paris. We have no idea, we Catholics of the North, with our Voltairean temples, of the luxury, elegance, and comfort of Spanish churches; such churches are furnished, alive, and lack the glacially deserted appearance of ours: the faithful can live there on familiar terms with their God.

The sacristies and chapter house of Toledo cathedral are of a more than royal magnificence; nothing is more noble or more picturesque than these vast rooms decorated with the solid and severe luxury to which the Church alone holds the secret. One sees only joiner’s work in walnut or black oak, tapestry or Indian damask door-hangings, curtains of embossed fabric with large heavy folds, ancient drapes, Persian carpets, fresco paintings. I shall refrain from describing them one by one, and will only speak of a room decorated with admirable frescoes representing religious subjects, in that German style which the Spaniards imitate so well, attributed to Berruguete’s nephew, if not Berruguete himself, since those prodigious geniuses travelled the threefold path of their art at the same. I would also cite an immense ceiling by Luca Giordano, over which a whole world of angels and allegories teem, foreshortened in the freest manner, and which creates a unique optical effect. From the centre of the vault springs a ray of light which, though painted on a flat surface, seems to fall perpendicularly towards your eye, whichever side you observe it from.

Here the cathedral’s treasures are kept, that is to say beautiful copes of brocade, uncut cloth of gold, and silver damask, wondrous guipure lace, silver-gilt shrines, diamond-studded monstrances, gigantic silver candlesticks, and embroidered banners; all the equipment and accessories needed for the presentation of that sublime Catholic drama which we call the Mass.

One of these rooms contains the Blessed Virgin Mary’s wardrobe, since cold statues of marble or alabaster are not enough for these southerners’ passionate piety; in their transports of devotion, they heap ornaments of extravagant richness on the object of their worship; nothing is lovely enough, brilliant enough, costly enough; under this flow of jewels the form and substance disappear: it concerns them little. Their greatest aim is for it to be materially impossible to hang one more pearl on the marble ears of the idol, to embed a larger diamond in the gold of her crown, or to trace one more pattern of jewels on the brocade of her dress.

Never did a queen in ancient times, not even Cleopatra, who drank pearls, or an empress of the Late Empire, or a duchess of the Middle Ages, or a Venetian courtesan at the time of Titian possess a more glittering casket, a richer trousseau than Our Lady of Toledo. We were shown some of the dresses: one is entirely covered, masking the background, with patterns and arabesques of fine pearls among which there are some of inestimable size and value, among others several rows of black pearls of incredible rarity; suns and stars of precious stones stud this prodigious dress, whose brilliance the eye can scarcely tolerate, and which is worth several million francs.

We ended our visit with an ascent of the bell tower, whose summit we reached via a series of ladders that were quite steep, and not very secure. About midway we came across, in a kind of storage area that we traversed, a series of gigantic mannequins, coloured and dressed in the fashion of the last century, which are employed in some procession akin to that of the tarasque at Tarascon.

The magnificent view visible from the top of the spire compensates to a large degree for the effort involved in the ascent. The whole city appears before one’s eyes with the clarity and precision of those scale models sculpted in cork by Auguste Pelet, which we admired at the last industrial exhibition. The comparison may no doubt seem most prosaic and not very picturesque, but in truth I cannot find a better or more accurate one. Those humped and tortured rocks of blue granite, which enclose the Tagus and one side of Toledo’s horizon, further add to the singularity of this landscape, flooded by and riddled with a harsh, pitiless, blinding light, which no reflection tempers, and which is further increased by the radiant, cloudless, vapourless sky, turned white by the heat, like iron in the furnace.

The heat was indeed atrocious, that of a plaster-kiln, and a rabid curiosity was demanded in order not to relinquish the exploration of monuments in this Senegambian temperature, but we still possessed all the ferocious ardour of enthusiastic Parisian tourists for local colour! Nothing deterred us; we only stopped to drink, since we were thirstier than African sand, and absorbed water like dry sponges. I really don’t know how we missed becoming dropsical; not counting wine and ices, we consumed seven or eight jars of water a day. Water! Water! was our perpetual cry, and a chain of muchachas, passing jugs from hand to hand from the kitchen to our room, was barely enough to quench the fire. Without this persistent flood, we would have turned to dust like the sculptors’ clay models when they neglect to dampen them.

Having viewed the cathedral, we resolved, despite our thirst, to visit the church of San Juan de los Reyes, but it was only after long negotiation that we succeeded in obtaining the keys, because the church had been closed for five or six years, and the monastery of which it is part is abandoned and falling to ruin.

San Juan de Los Reyes is sited on a bank of the Tagus, close to the Puente de San Martín; its walls possess that beautiful orange tint which distinguishes ancient monuments in climates where it seldom rains. A collection of statues of various kings in noble, chivalrous attitudes, and of proud appearance, decorates the exterior; but this is not what is most singular about San Juan de los Reyes; all the churches of the Middle Ages are populated with statues. A multitude of chains hanging from hooks adorn the walls from top to bottom: these are the shackles of Christian prisoners set free following the conquest of Granada. The chains, hung up there as ornaments, and ex-votos, give the church the somewhat strange, forbidding, though false appearance of being a prison.

An anecdote on this subject was related to us, which I will set down here since it is short and characteristic. The dream of every jefe politico (civil governor), in Spain, is to lay out an alameda (promenade), as every prefect in France desires a Rue de Rivoli in his city. The dream of the jefe politico of Toledo was to grant his citizens, therefore, a pleasant walkway; the location was chosen, the earthworks were soon completed, thanks to the cooperation of the Presidio (garrison); all that was missing from the promenade were trees, but trees cannot be improvised, and the jefe politico had the wise idea of replacing them with stone markers linked together by means of iron chains. As money is scarce in Spain, the ingenious administrator, a resourceful man if ever there was one, thinking of the ancient chains of San Juan de Los Reyes, said to himself: ‘By Heaven, there’s the perfect solution!’ And the chains from the prisoners delivered by Ferdinand and Isabella were attached to the boundary stones of the alameda. The locksmiths who carried out the work each received a few fathoms of this noble scrap-metal; a handful of intelligent people (for there are some everywhere) opposed this barbarity, and the chains were returned to the church. As for those that had been given as payment to the workers, they had already been forged into plough-shares, iron shoes for the mules, and various utensils. The tale is perhaps a slander, but it has all the characteristics of plausibility: we relate it as it was told to us: now let us return to our church. The key turned, with some difficulty in the rusty lock. This slight obstacle overcome, we entered a ruined cloister of admirable elegance; slender, semi-detached columns supported, on flowered capitals, arcades with extremely delicate ribbing and embroidered decoration; on the walls ran long inscriptions in praise of Ferdinand and Isabella, in Gothic characters interspersed with flowers, branches and arabesques; a Christian imitation of the Moors’ employment of sentences and verses of the Koran as architectural ornamentation. What a pity that such a precious monument should have been abandoned in this way!

By giving a few kicks to doors obstructed by worm-eaten boards or blocked with rubble, we managed to gain entry to the church, which is of a charming style, and seemed, apart from a degree of violent mutilation, to have been completed only yesterday. Gothic art has produced nothing more pleasant, elegant or finer. A gallery surrounds all, pierced and fenestrated like a steel fish-slice, its adventurous balconies being suspended from the beams of the pillars, whose recesses and projections it follows perfectly; gigantic scrollwork, eagles, chimeras, heraldic animals, coats of arms, banners and emblematic inscriptions like those in the cloister complete the decoration. The choir placed opposite the retablo, at the far end of the church, is supported by a low arch of beautiful appearance and great boldness.

The altar, which was undoubtedly a masterpiece of sculpture and painting, had been mercilessly overturned. These unnecessary devastations sadden the soul and make us doubt human intelligence: how can old stones hinder new ideas? Can we not make a revolution without demolishing the past? It seems to me that the Constitucion would have lost nothing by Ferdinand and Isabella’s church being left intact; she, that noble queen who trusted in genius, and endowed the universe with a new world.

Risking our lives on a half-broken staircase, we entered the interior of the monastery: the refectory is quite large and holds nothing in particular except a frightful painting set above the door; it represents, made even more hideous by the layer of dirt and dust which covers it, a corpse prey to decomposition, with all those horrid details treated so complacently by Spanish artists. A symbolic and funereal inscription, one of those threatening biblical sentences which give such terrible warnings of human nothingness, is written at the bottom of this sepulchral painting, singularly chosen for a refectory. I know not if all the stories about the gluttony of monks are true; but, for my part, I would possess but a mediocre appetite in a dining room decorated in that way.

Above, on each side of a long corridor, the deserted cells of the vanished monks are arranged like cells in a bee hive; they are all exactly the same as each other, and plastered with lime. This whiteness greatly diminishes the poetical impression by ridding the dark corners of terrifying chimeras. The interior of the church and the cloister are also whitewashed, giving them an air of the fresh and recent that contrasts with the style of the architecture and the condition of the buildings. The absence of humidity and the heat have prevented flowering plants and weeds germinating in the interstices of the stones and rubble, and the debris lacks the green coating of ivy with which time clothes ruins in northern climes. We wandered through the abandoned building for quite some time, following its endless corridors, ascending and descending hazardous staircases, like none other than Ann Radcliff’s heroes, but saw no ghosts, in fact, except for two wretched lizards which fled on all fours, doubtless ignoring, in their capacity as Spaniards, the French proverb: ‘The lizard is man’s friend.’ As for the rest, this walk among the veins and members of a great construction from which life has withdrawn, is the liveliest of pleasures one can imagine; forever expecting to encounter at the corner of an arcade an ancient monk with gleaming forehead, eyes flooded with shadow, walking gravely, arms crossed on his chest, on his way to some mysterious service in the desecrated and deserted church.

We retreated, since there was no more of interest to see, not even the kitchens, to which our guide led us downwards with a Voltairean smile that a subscriber to the Constitutionnel would not have disavowed. The church and the cloister are of rare magnificence; the rest is of the strictest simplicity: everything for the soul, nothing for the senses.

A short distance from San Juan de los Reyes is, or rather is not, the famous synagogue (latterly the church of Santa María la Blanca) in the Moorish style; since, lacking a guide, you might pass it by twenty times without suspecting its existence. Our guide knocked at a door cut in the most insignificant reddish adobe wall in the world; after some time, since the Spaniard is never in a hurry, someone came, opened the door, and asked us if we wished to visit the synagogue; upon our affirmative answer, we were introduced into a sort of courtyard filled with uncultivated vegetation, in the middle of which flourished an Indian fig-tree with deeply incised leaves, of an intense and brilliant greenery as if they had been varnished. In the background was a characterless building, looking more like a barn than anything else. We were taken into this hovel. Never was there a greater surprise: we were in the midst of the Orient; the slender columns with capitals shaped like turbans, the Turkish arches, the verses from the Koran, the flat ceiling with cedarwood compartments, the daylight admitted from above, nothing was lacking. Remains of old, almost erased, illuminations dyed the walls strange colours, and further added to the singularity of the effect. This synagogue, of which the Arabs made a mosque, and the Christians a church, today serves as a workshop and dwelling for a carpenter. His workbench took the place of the altar; this desecration is very recent. We can still see the remains of the retablo, and the inscription on black marble which notes the consecration of the building to Catholic worship.

Speaking of the synagogue, let me set down a rather curious anecdote here. The Jews of Toledo, no doubt to abate the horror they seemingly inspired in the prejudiced Christian population who thought them deicides, claimed not to have consented to the death of Jesus Christ, as per the following: when Jesus was put on trial, the council of priests, chaired by Caiaphas, consulted the tribes to know whether he should be released or executed: the question was put to the Jews of Spain, and the synagogue of Toledo declared itself in favour of acquittal. This tribe was not covered in the blood of the Righteous One, and therefore did not deserve the execrations heaped upon those who voted against the Son of God. The original response of the Jews of Toledo, with a Latin translation of the Hebrew text, is said to be preserved in the Vatican archives. As a reward, they were allowed to build this synagogue, which is, I believe, one of the few that was thereafter tolerated in Spain.

We had been told of the ruins of an ancient Moorish pleasure-garden, the Galiana Palace; we were led there after leaving the synagogue, despite our fatigue, because time was pressing, and we were due to leave next day for Madrid.

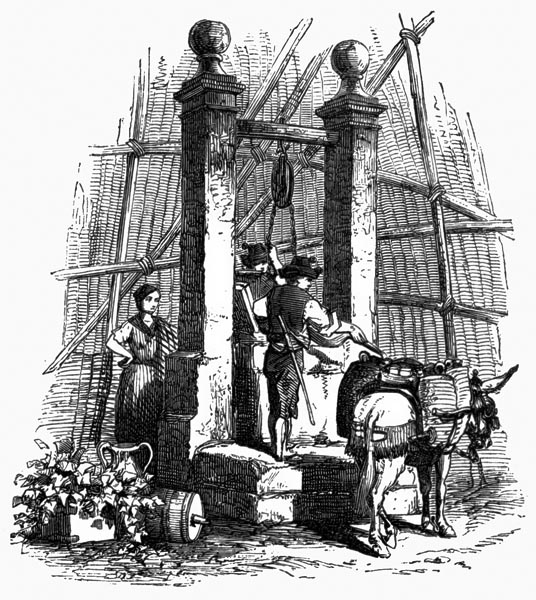

The Galiana Palace is located outside the city, in La Vega, and you reach it via the Alcántara bridge. After a quarter of an hour walking through fields and crops where ran a thousand small irrigation canals, we arrived at a clump of fresh-looking trees, at the foot of which a water-wheel turned. of the most ancient and Egyptian simplicity. Earthen jars, attached to the spokes of the wheel by reed cords, lifted the water and poured it into a channel of hollow tiles, leading to a reservoir, from which it was easily directed to places where one could quench one’s thirst.

An enormous pile of reddish bricks was outlined, in broken silhouette, behind the trees’ foliage; it was the Galiana palace.

We entered this pile of rubble, inhabited by a peasant family, through a low door; it is impossible to imagine anything darker, smokier, dirtier or more cavernous. The Troglodytes were housed like princes compared to these people, and yet the charming Aixa Galiana, the Moorish beauty with long henna-tinted eyes and brocade jacket studded with pearls, had set her little slippers on this broken floor; she had leaned on this window, watching in the distance the Moorish horsemen in the Vega practicing throwing the djerrid (wooden javelin).

We continued our exploration, bravely; climbing to the upper floors on shaky ladders, clinging with hands and feet to the tufts of dry grass, which hung like beards from the sullen old walls.

Having attained the summit, we noticed a strange phenomenon; we arrived with white trousers, we left with black ones, but a blackness that was leaping, teeming, swarming: we were covered with imperceptible little flies which had precipitated themselves upon us in compact masses, attracted perhaps by the coolness of our northern blood. I never would have believed that there were so many flies in the world.

A few pipes to bring water to the ovens are the only vestiges of magnificence that time has spared: the glass and enamelled earthenware mosaics, the marble columns their capitals covered with gilding, relief-work, and verses from the Koran, the alabaster basins, the stones pierced with holes to allow perfumes to filter through, all have vanished. What remains is a carcass: high walls and piles of bricks that dissolve to dust; for these wondrous buildings, recalling the enchantments of the Thousand and One Nights, are sadly built only of bricks and adobe covered with a layer of stucco or lime. All this lacework, all these arabesques, are not, as is generally believed, cut from marble or stone, but moulded in plaster, which allows them to be reproduced endlessly, and at minimal expense. It takes all the conserving dryness of the Spanish climate for monuments built with such frail materials to survive till our day.

The legend of Galiana is better preserved than her palace. She was the daughter of King Galafre, who loved her above all, and had a pleasure house built for her in La Vega with delightful gardens, kiosks, baths, and fountains that rose and fell according to the moon’s phase, either by magic or one of the hydraulic devices so familiar to the Arabs. Galiana, idolised by her father, lived most pleasantly in this charming retreat, occupying herself with music, poetry, and dance. Her hardest task was to evade the gallantries and adorations of her suitors. The most importunate and relentless of all was a certain petty king of Guadalajara, named Bradamant, a giant of a Moor, bold and fierce. Galiana could not stand him; and, as the chronicler says: ‘What matter that the knight is full of fire, if the lady is made of ice?’ However, the Moor was not discouraged, and his passion to see Galiana and speak to her was so strong that he had a covered way dug from Guadalajara to Toledo along which he came to visit her every day.

At that time, Charlemagne, son of Pepin, came to Toledo, sent by his father, to bring relief to Galafre against the king of Cordoba, Abdelrhaman. Calafre lodged him in this same Galiana Palace; since the Moors allowed their daughters, willingly, to receive famous and important people. Charlemagne had a tender heart under his iron armour, and it was not long before he was madly in love with the Moorish princess. At first, he tolerated Bradamant’s attentions to her, not yet being sure of having himself touched the beauty’s heart; but as Galiana, despite her reserve and modesty, could not long hide from him the secret preference of her soul, he began to show jealousy, and demanded the suppression of his swarthy rival. Galiana, who was already French to the core, or so says the chronicle, and who moreover hated that petty king of Guadalajara, gave the prince to understand that she and her father were equally annoyed by the pursuits of the Moor, and that she would be glad to be rid of him. Charlemagne did not need to be told twice; he challenged Bradamant to single combat and, though Bradamant was a giant, defeated him, cut off his head, and presented it to Galiana, who found it a gift in good taste. This gallantry advanced the French prince strongly in the heart of the beautiful Moor, and, their mutual love increasing, Galiana pledged to embrace Christianity, so that Charlemagne could wed her; which was swiftly done, Galafre being delighted to give his daughter to so great a prince. In the meantime, Pepin had died, and Charlemagne returned to France, taking Galiana with him, she being crowned queen, and received with great rejoicing. This is how a Moorish lady become a Christian queen, ‘and the memory of this story, still associated with the ancient building, deserves to be preserved in Toledo,’ adds the chronicler by way of final reflection.

Before all else we needed to rid ourselves of the populations of microscopic insects that had stained the folds of our formerly white trousers; fortunately, the Tagus was not far off, so we bore Princess Galiana’s flies there directly, and did as foxes do who gradually immerse themselves in water up to their noses, gripping with the tips of their teeth a piece of bark, which they later abandon to the river when they feel it is sufficiently crewed; for the infernal little creatures, encroached on by the waves, take refuge and lie dormant thereon. We ask forgiveness from our readers for these ample and picaresque details which would be better suited to La Vida de Lazarillo de Tormes or Mateo Alemán’s Guzmán de Alfarache; but a trip to Spain would not be complete without them, and we hope to be absolved on behalf of local colour.

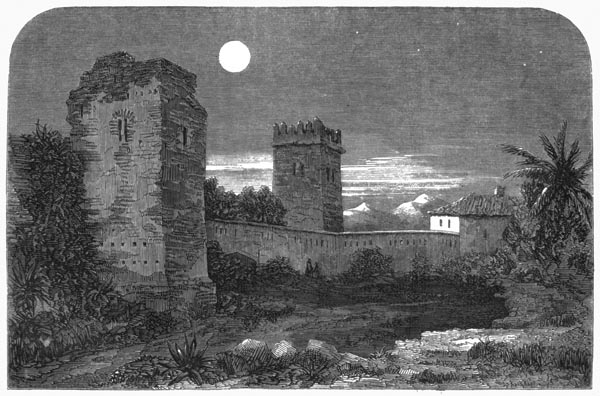

The far bank of the Tagus is lined with sheer cliffs which are difficult of approach, and it was not without some difficulty that we descended to the place where we were to carry out this great drowning. I began to swim like a mariner as cleanly as possible, in order to be worthy of a river as famous and respectable as the Tagus, and, after a few strokes, I arrived at some ruined buildings, shapeless remains of masonry, which topped the level of the river by a few feet only. On the bank, on precisely the same side, stood an old ruined tower, with a semi-circular arched entrance, where some laundry hung up by washerwomen was drying, prosaically, in the sun.

I had merely reached the Baño de la Caba (or Cava), otherwise known to the French as the bath of the legendary Florinda, and the tower that I had in front of me was the tower of Rodrigo ‘the last king of the Goths’. It was from the balcony of this window that Rodrigo, hidden behind a curtain, spied on the young girls bathing, and saw the beautiful Florinda la Caba comparing her legs, and those of her companions, to discover who had the roundest and shapeliest. Behold, on what things great events hang! If Florinda had possessed an ugly calf or an unsightly knee, the Arabs would not have entered Spain. Unfortunately, Florinda had trim feet, slender ankles, and the whitest, most attractive legs in the world. Rodrigo fell in love with the reckless bather, and seduced her. Count Julian of Ceuta, father of Florinda, furious at the outrage, betrayed his country to take revenge, and called on the Moors for aid. Rodrigo lost this famous battle which is so much talked about in the romanceros, and perished miserably in a coffin full of vipers, where he had lain himself down to do penance for his crime. Poor Florinda, stigmatised by the ignominious name of Caba, was held responsible by all Spain for this horror; yet what a preposterous and singular idea to have allowed a bath for young girls to face the young king’s tower!

Since I have mentioned Rodrigo, let me also note here the legend of the Cave of Hercules, which is inevitably linked to the story of that unfortunate Visigoth prince. The Cave of Hercules (Cuevas de Hércules) is an underground passage which extends, it is said, three leagues beyond the walls, and whose entrance, tightly closed and padlocked, is in the alley of San-Ginès, on the furthest elevated point from the city. On this place there once stood a palace founded by Tubal; Hercules restored it, enlarged it, and established his laboratory and his school of magic there, for Hercules, of whom the Greeks later made a god, was above all a powerful cabalist. By means of his art, he built an enchanted tower, whose talismans and inscriptions stated that, if anyone entered this magical enclosure, a fierce and barbarous nation would invade Spain.

Fearing that this disastrous prediction would be fulfilled, all the kings, and especially the Gothic kings, added new locks and fresh padlocks to the mysterious entrance, not because they had certain faith in the prophecy, but because, as wise people, they cared not at all for involvement in such enchantments and sorceries. Rodrigo, more curious, or more in need as his debaucheries and prodigality had exhausted his wealth, wished to attempt the adventure, hoping to find considerable treasure in the enchanted depths: he made for the passage, at the head of a few determined folk equipped with torches, lanterns and ropes, and arrived at its entrance, carved from the living rock, closed with an iron cover amply-padlocked, and adorned by a tablet on which could be read, in Greek characters: The king who unlocks this passage and is able to discover the wonders it contains, will meet with both good and evil. Previous kings, fearful of the consequences, had not dared go further; but Rodrigue, risking evil in hopes of good, ordered the padlocks to be broken, the bolts forced open, and the lid lifted; those who boasted of being the bravest descended first, but soon returned, trembling, pale, frightened, their torches extinguished, and those who could speak reported that they had been rendered afraid by a dreadful vision. Rodrigo, still resolving to breaking the spell, arranged fresh torches in such a way that the air flowing from the cave could not extinguish them, placed himself at the head of the troop, and entered boldly: he soon came to a square chamber, its architecture of the finest, in the midst of which stood a bronze statue, tall in stature and fearsome in appearance. The statue’s feet were set on a column three cubits high, and it held in its hand a mace with which it struck great blows upon the pavement, producing the sound and gusts of air which had caused so much fear on first entry. Rodrigo, brave as any Goth, resolute as any Christian who trusts in God and is unsurprised by pagan enchantments, advanced upon this colossus and asked its permission to visit the wonders that were there.

The bronze warrior, signifying its agreement, ceased striking the earth with its heavy mace: it was possible to see what lay in the room, and it was not long before Rodrigo came across a chest on the lid of which was written: He who opens me will see wonders. On seeing the statues acquiescence, the king’s companions recovered from their fright, and encouraged by the auspicious inscription, prepared to fill their cloaks and pockets with gold and diamonds; but all that was found in the chest was a rolled-up canvas on which were painted troops of Arabs, their heads girded with turbans; some were on foot, others on horseback, armed with shields and spears, and an inscription whose meaning was: He who has come this far, and opened the chest, will lose Spain, defeated by people such as these. King Rodrigo tried to conceal the melancholy emotion he experienced, so as not to cause the others sadness, and sought to see if there would not be some compensation for so disastrous a prophecy. Looking higher, Rodrigue saw on the wall, to the left of the statue, a cartouche which read: Wretched king! You entered here to your misfortune! And, on the right, another meaning: You will be dispossessed by foreign nations, and your people suffer harsh punishment. Behind the statue was written: I invoke the Arabs; and in front: I do my duty.

The king and his courtiers withdrew in confusion, filled with dark foreboding. That same night there was a furious storm, and the ruins of the Tower of Hercules collapsed with a dreadful crash. Not long afterwards events justified the prediction in the magic cave; the Arabs, depicted thus on the rolled-up canvas in the chest, displayed, in actuality, their turbans, spears and shields of a strange shape, on the unfortunate soil of Spain: all this, because Rodrigo gazed at Florinda’s leg, and clambered down into a cellar.

But as night is falling, we must now return to the fonda, have supper, and sleep, since we still have to visit the hospital of Cardinal Don Pedro Gonzales de Mendoza, the arms factory, the remains of the Roman amphitheatre, and a thousand other curiosities, and we leave tomorrow evening. As for me, I am so weary of treading the diamond-sharp pavements, I would rather walk on my hands a while, like the clowns at the circus, and rest my aching feet. O hansom-cab of civilization! Omnibus of progress! I invoke you, painfully; yet how would you have done in the streets of Toledo?

The Cardinal’s hospital (Hospital de Tavera) is a large building of broad, severe proportions, which would take too long to describe. We will cross, in haste, its courtyard surrounded by columns and arcades, only remarkable for two circular air shafts with white marble copings, and immediately enter the church to examine the tomb of the cardinal, carved in alabaster by the prodigious Berruguete who lived for more than eighty years, blessing his homeland with masterpieces of varied style but always equal perfection. The cardinal lies on his tomb in his papal vestments; Death with his bony fingers, has pinched his nose, and a supreme muscular contraction that sought to hold back the soul on the verge of escape clamped the corners of the mouth and tapered his chin; never has the mask of a dead person’s face been more sinisterly faithful; and yet the beauty of the work is such that we forget whatever is repellent regarding this spectacle. Little children, in attitudes of desolation, support the plinth and the cardinal’s coat of arms; the most free and fluid terracotta possesses no greater a freedom and fluidity; it is not sculpted, it is kneaded!

There are also, in this church, two paintings by Doménikos Theotokópoulos, known as El Greco, an extravagant and bizarre painter who is, at present, scarcely known outside Spain. His folly was, as you may know, his fear of being seen as an imitator of Titian, whose pupil he had been; this preoccupation led him, stylistically, to indulge in the most baroque refinements and caprices.

The first of these two paintings, that which represents the Holy Family, must have rendered poor El Greco somewhat unhappy, since, at first glance, one might take it for a Titian. The ardent colouring, the liveliness of tone in the draperies, a beautiful yellow-amber glow which warms even the freshest nuances of the Venetian painter, everything combines to deceive the most practiced eye: the brushstrokes alone are less broad and thick. What little reason El Greco still possessed must have capsized utterly on the dark ocean of madness after having completed this masterpiece; there are few painters likely to go mad for a similar reason these days.

The other painting, whose subject is the Baptism of Christ, belongs entirely to El Greco’s second style: here there is an excessive use of black and white, violent contrasts, a singular use of colour, freedom in the poses, draperies folded and crumpled at will; while in all this there reigns a depraved energy, a sickly power, which betrays both the great painter and the mad genius. Few paintings interest me as much as those of El Greco, because the worst always reveal something unexpected, beyond imagining, that surprises one and makes one dream.

After the hospital we visited the arms factory. It is a vast, symmetrical building, in good taste, founded by Charles III of Spain, whose name can be seen on all monuments of public utility; the factory is built close to the Tagus, whose waters are used to temper the blades, and drive the wheels of the machinery. The workshops occupy the sides of a large courtyard, surrounded by porticos and arcades as are almost all courtyards in Spain. Here, the iron is heated; there, it is subjected to the hammer; further on it is tempered; in one room are wheels for polishing and sharpening; in another scabbards and hilts are made. We will carry this investigation no further, since it offers our readers nothing in particular, and will only say that the composition of these rightly famous blades involves the old iron shoes of horses and mules, carefully gathered for the purpose.

To confirm that the blades of Toledo still deserve their reputation, we were led to the testing room: a worker, of tall stature and colossal strength, took a weapon of the most ordinary kind, a straight cavalry sabre, drove it into a lead ingot fixed to the wall, and made the blade bend every way like a riding crop, so that the hilt almost reached the tip; the elastic and flexible temper of the steel allowed it to withstand this test without breaking. Then the man placed himself in front of an anvil and gave it a blow so well applied that the blade entered a millimetre or so; this feat made me think of the scene from a Walter Scott novel (The Talisman, chapter XXVII), in which Richard the Lionheart and Saladin practice cutting iron bars and cushions.

The Toledo blades of today then are equal in that respect to those of yesteryear; the secret of their temper is not lost, only the secret of their form: modern works in truth only lack that one little thing, so despised by progressive people unlike those of ancient times. A modern sword is merely a tool, a sixteenth-century sword is both a tool and a treasure.

We had hoped to find in Toledo various old weapons, daggers, poignards, longswords, two-handed swords, rapiers and other curiosities suitable to set as trophies on a wall or a dresser, and we had learned by heart, for this purpose, the names and the marks of the sixty armourers of Toledo collected by the medievalist Achille Jubinal, but the opportunity to put our knowledge to the test did not present itself, since there are no more such blades in Toledo than there is leather in Cordoba, lace at Mechelen, oysters at Ostend, or pâté de foie gras in Strasbourg; it is in Paris that all the rarities are found, and if we encounter any of them in foreign countries it is because they come from Mademoiselle Delaunay’s little shop, on the Quai Voltaire.

We were also shown the remains of the Roman amphitheatre and the naumachia, which have the exact appearance of a ploughed field, like all Roman ruins in general. I lack the imagination needed to go into ecstasies over such problematic nothingness; that is a task I will leave to the antiquarians; I would rather speak to you of the walls of Toledo, which are visible to the naked eye and have an admirably picturesque effect. The buildings blend very happily with the uneven contours of the land; it is often difficult to say where rock ends and rampart begins; each civilisation has set its hand to the work; this section of wall is Roman, that tower is Gothic, and these battlements are Arab. The entire portion which extends from the Puerta de Cambron to the Puerta de Bisagra (its name derived some say from via sacra), where the Roman road probably ended, was built by Wamba king of the Visigoths. Each of these stones has its story, and if I wished to relate everything, I would need a volume instead of an article; but what does not exceed the bounds of my role as traveller is to repeat once more what a noble sight Toledo makes on the horizon, seated on its throne of rock, with its belt of towers, and its diadem of churches: one cannot imagine a stronger or more severe profile, a form coated with richer colours, or a city that preserves the physiognomy of the Middle Ages more faithfully. I remained in contemplation of it for more than an hour, trying to sate my sense of vision, and to engrave the silhouette of that admirable perspective in the depths of my memory: night fell too soon, alas, and we retired to bed, since we had to leave at one in the morning, to avoid the worst of the heat. Indeed, our calesero (coachman) arrived punctually, at midnight, and we clambered, still asleep but in a state of pronounced somnambulism, onto the meagre cushions of our carriage. The dreadful jolting caused by Toledo’s cobblestones soon woke us enough to enjoy the fantastic appearance of our nocturnal caravan. The carriage, with its large scarlet wheels and extravagant trunk seemed to pass through waves of houses closing behind it so near were the walls! A sereno (watchman) with bare legs, loose breeches, and the colourful headscarf of the Valencians, walked before us, bearing at the end of his spear a lantern whose flickering rays produced a play of shadow and light that Rembrandt would not have disdained to employ in some of his fine etchings of night-watches and patrols; the only noise to be heard was the silvery tremor of the bells on our mule’s neck, and the creaking of the axles. The townspeople slept as soundly as the statues in the Chapel of Los Reyes Nuevos. From time to time, our sereno thrust his lantern under the nose of some odd fellow sleeping in the street, and drove him away with the shaft of his spear; for wherever sleep takes a Spaniard, he spreads his cloak on the ground, and retires to bed, with a perfect show of philosophy and phlegmatism. In front of the gate, which was not yet open, and at which we were made to wait for two hours, the floor was strewn with sleepers, snoring in every possible tone, because the street is the only bedroom which is not also full of animals, and where entering your alcove requires the resignation of an Indian fakir. Finally, the accursed gate swung on its hinges, and we returned by the road we had come.

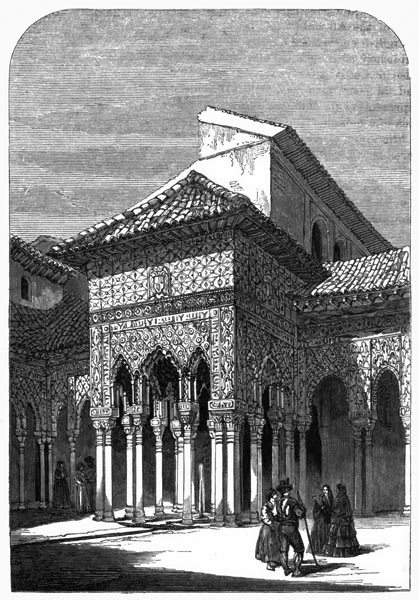

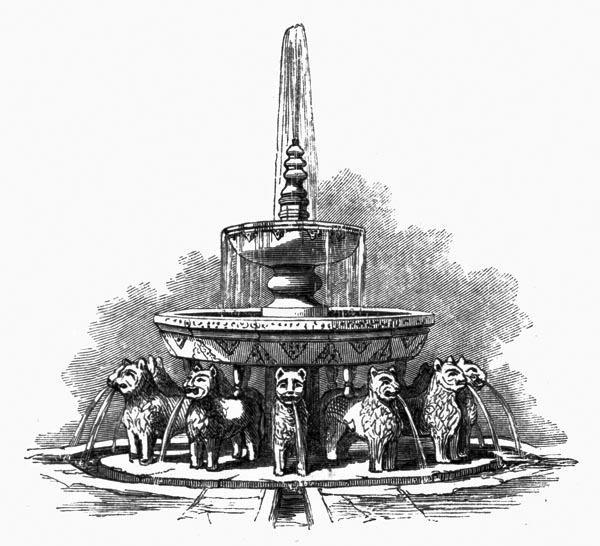

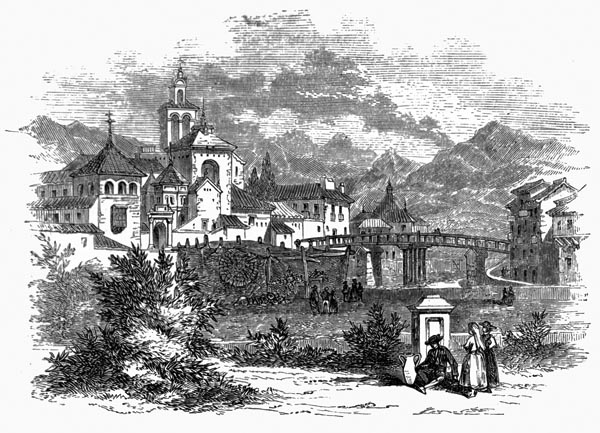

Part XI: A Festival Procession in Madrid – Aranjuez – A Patio – The Countryside of Ocaña – Tembleque and its Garters – A Night in Manzanares – The Knives of Santa Cruz de Mudela – The Puerto de los Perros – The Colony of La Carolina – Bailén – Jaén, its Cathedral and its Dandies – Granada – The Alameda – The Alhambra – The Generalife – The Albaicín – Life in Granada – The Gitanos – The Charterhouse – Santo Domingo – An Ascent of Mulhacen

We were obliged to return to Madrid to take the diligence for Granada; we could have travelled to Aranjuez and waited for it there, but ran the risk of finding it full, and we decided on the former course.

We arrived at Illescas at around one, half-roasted, if not wholly so, but without further incident. We could barely wait to complete the journey which had nothing new to offer us, except that we were travelling in the opposite direction.

My companion preferred to sleep, while I, already more familiar with Spanish cuisine, began to compete for my dinner with countless swarms of flies. The hostess’ daughter, a charming child of twelve or thirteen years, with Arab eyes, stood near me, a fan in one hand, a small broom in the other, trying to ward off the unwelcome insects which returned to the charge buzzing more furiously than ever as soon as the fan slowed or halted its movements. With this aid, I managed to cram a few morsels, fairly free of flies, into my mouth and, when my appetite was a little appeased, I began a dialogue with my insect-hunter which my ignorance of the Spanish language necessarily constrained a good deal. However, with the help of my precious dictionary, I managed to carry on a very passable conversation for a foreigner. The little one told me that she knew how to read and write all kinds of printed script, even Latin, and that in addition she played the pandero (tambourine) quite well, a talent of which I urged her to give me a sample, which she did, with very good grace, to the detriment of my comrade’s sleep, whom the jingling of the copper plates, and the dull sound of the donkey-skin brushed by the thumb of the little musician, ended by waking.

The fresh mule was harnessed. We had to set out again on our way, and really needed substantial moral courage to leave, in thirty degrees of heat, a posada where the perspective consisted of several rows of jars, pots and alcarrazas (earthenware jugs) covered with beads of moisture. Merely drinking the water is a pleasure I only truly experienced in Spain; it is indeed pure, clear and of exquisite taste. The Muslim prohibition against drinking wine is the easiest of prescriptions to follow in such climes.