Théophile Gautier

Travels in Spain (Voyage en Espagne, 1840)

Parts XIII to XV - Seville, Cadíz, Gibraltar, and Valencia

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2024 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Part XIII: Écija – Córdoba – The Archangel Raphael – The Mosque

- Part XIV: Seville – La Cristina – La Torre del Oro – Italica – The Cathedral – La Giralda – El Polho Sevillano – La Caridad and Don Juan de Marana

- Part XV: Cádiz – A Visit to the Brig ‘Voltigeur’ – The Rateros – Jerez de la Frontera – The Toro Embolado – The Steamboat – Gibraltar – Cartagena – Valencia – La Lonja de la Seda – The Convent of La Merced – The Valencians – Barcelona – The Return

Part XIII: Écija – Córdoba – The Archangel Raphael – The Mosque

As yet we had only experienced travelling by two-wheeled cart; the four-wheeled equivalent we had yet to try. One of these amiable vehicles was about to leave for Córdoba, already burdened with a Spanish family; we completed the load. Imagine a low-slung affair, equipped with slatted sides, whose floor is simply woven esparto-grass, into which trunks and packets are piled without much concern as to the projecting corners. Over the pile are thrown two or three mattresses, or, to be more precise, in our case two canvas bags within which a few lumps of lightly-carded wool bobbed about; on these mattresses the poor travellers lie, transversally, in a position quite similar (forgive the mundane comparison) to that of calves being carried to market. True, the travellers’ feet are not bound together, but their situation is scarcely improved by that. The whole affair is covered with a large awning stretched over iron hoops, led by a mayoral, and drawn by four mules.

The family with whom we journeyed was that of a well-educated engineer who spoke good French: they were accompanied by a great scoundrel of mongrel appearance, formerly a brigand in José Maria’s band, and now a mine supervisor. This fellow followed the wagon on horseback, a knife in his belt, a rifle at his saddle-bow. The engineer seemed to think highly of him; he praised his probity, with regard to which the man’s former profession gave him little or no concern; It is true that when speaking of José Maria (José Maria Hinojosa Cabacho, known as ‘El Tempranillo’), he told me several times that the aforesaid was a brave and honest man. This opinion, which would seem slightly paradoxical to us as regards a bandit, is shared in Andalusia by the most honourable folk. Spain has retained an Arabian inclination on this point, and brigands there easily pass for heroes, an identification less bizarre than it seems at first, especially in southern regions where imaginations are extremely impressionable. Contempt for death, audacity, composure, prompt and bold decision-making, skill and strength, the kind of greatness which attaches to a man in rebellion against society, all those qualities which act so powerfully on minds that are still scarcely civilised, are they not the qualities that define greatness of character, and are people wrong to admire them so, in men of such energetic nature, even though their use of them is reprehensible?

The road we followed rose and fell, quite steeply, amidst a country studded with hills and criss-crossed by narrow valleys whose depths were occupied by dry stream-beds bristling with enormous stones that jolted us about dreadfully, drawing shrill cries from the women and children. Along the way, I noted various admirably-poetic and colourful sunset effects. In the distance, the mountains took on hues of purple and violet, glazed with gold, of an extraordinary fieriness and intensity; the complete absence of vegetation gives this landscape, composed solely of earth and sky, a character of grandiose bareness and fierce harshness whose equivalent exists nowhere else, and which painters have never rendered successfully. We stopped for a few hours, at nightfall, in a small hamlet of three or four houses, to let the mules rest and allow us to obtain some food. Improvident, like all French travellers, though a five-month stay in Spain should have taught us better, we had brought no provisions from Málaga, so were obliged to sup on dry bread and a little white wine which a woman from the posada was kind enough to supply us with, for Spanish pantries and cellars do not share the abhorrence that nature has, it is said, for a void, and embrace its nothingness with a secure conscience.

At about one in the morning, we set off again, and, despite the dreadful jolting, the children of the mine-employee rolling all over us, and the frequent shocks our bobbling heads received on striking the sides of the wagon, we soon fell asleep. As the sun tickled our noses with a ray like a gilded ear of wheat, we approached Carratraca, an insignificant village, unmarked on the map, possessing only its sulphurous springs effective for treating skin-disease, which attract a rather suspect population, and an unhealthy trade, to that lost place. They play a devilish game of cards there; and, though it was still very early, both cards and coins were already in play. It was somewhat hideous to see these sickly people with greenish earthy faces, full of an ugly rapaciousness, slowly extending their convulsive fingers to seize their winnings. The houses of Carratraca, like all those in the villages of Andalusia, have been whitewashed; which, combined with the bright colour of the tiles, the vine garlands, and the shrubs that surround them, grants them an air of celebration and ease quite different from the ideas we have in the rest of Europe of Spanish uncleanliness, ideas generally false, which can only have come about in connection with a few miserable hamlets in Castile, of which we ourselves possess the equivalent, and worse, in Brittany and the Sologne.

In the courtyard of the inn, my eyes were attracted by crude frescoes of primitive naivety, representing bullfights; around the paintings were coplas (verses) in honour of Paquiro Montes and his quadrille. The name of Montes is quite as popular in Andalusia as that of Napoleon is here; his portrait adorns walls, fans, and snuff-boxes, while the English, great exploiters of the latest fashion, whatever it may be, distribute, from Gibraltar, thousands of scarves on which the features of the famous matador are reproduced, printed in red, purple, and yellow, and accompanied by flattering captions.

Learning from our hunger of the previous day, we bought some provisions from our host, in particular a ham for which he made us pay an exorbitant price. There is much talk of highway robbers; but it is not on the road that danger lies; it is beside it, in the inns, where they slit your throat, where they fleece you in complete safety, without you being able to resort to defensive weapons and fire your rifle at the lad who brings you your bill. I pity the bandits with all my heart; such hoteliers leave them little opportunity for gain, and only hand travellers over to them once they are like lemons from which the juice has been squeezed. In other countries, they make you pay dearly for whatever they sell you; in Spain, you pay for the absence of the same with its weight in gold.

Our siesta over, the mules were harnessed to the wagon, each of us regained our place on the mattresses, the escopetero mounted his little mountain-pony, the mayoral gathered some small stones to throw at the ears of his mules, and we set off once more. The country we crossed was wild without being picturesque: the hills bare, rough, flayed, stripped to the bone; the beds of the stony torrents like scars carved in the ground by the ravages of the winter rain; the olive groves whose pale foliage, caked with dust, stirring not a single thought of greenery or freshness; here and there, from the torn tuff or chalk sides of the ravines, sprang a few tufts of fennel whitened by the heat; over the powdery trail lay the tracks of snakes and vipers, and above all this the sky burning like the roof of an oven, with not a breath of air, not a breath of wind! The grey sand raised by the mules’ hooves fell without a swirl. A hot sun beat down on the canvas awning of our wagon, where we ripened like melons under glass. From time to time, we descended and went on foot for a while, keeping to the shadows cast by the horse or the cart and, having stretched our legs, scrambled back to our places, squashing the children and their mother somewhat, since we could only reach our corner by crawling on all fours under the low arch formed by the hoops above the wagon. Through crossing quagmires and ravines, and taking short-cuts over the ground, we strayed from the correct route. Our mayoral, hoping to recover it, forged ahead, as if he knew perfectly well where he was going; since cosarios and guides only concede that they are lost in the last extremity, and only after leading you five or six leagues from the true path. It is fair to say, however, that nothing was easier than going awry on this fabled track, barely visible, whose course was interrupted at every moment by deep ravines. We found ourselves among wide fields, sparsely sown with olive trees possessing twisted and stunted trunks in fearful attitudes, and lacking any trace of human habitation, or the appearance of any living creature; since morning, we had only encountered a half-naked muchacho, driving in front of him, amidst a torrent of dust, half a dozen black pigs. Night fell. To make matters worse, it was not a moonlit one, and we had only the flickering light of the stars to guide our way.

At every moment, the mayoral left his seat and descended to feel the ground with his hands, hoping to come across a rut, some wheel-mark that would indicate the track; but his searches were in vain, and, most reluctantly, he found himself obliged to inform us that we were lost, having no idea himself where he was: he could not imagine why, having covered the same route twenty times, and could reach Córdoba with his eyes shut. This all seemed rather suspicious, and it occurred to us that we were perhaps exposed to being ambushed. The situation was otherwise unpleasant; we found ourselves caught at night in a deserted countryside, far from any human aid, in the midst of a region renowned for containing more thieves than all the rest of Spain combined. These reflections undoubtedly also occurred to the mining employee and his friend, the former associate of José Maria, who must have been knowledgeable in such matters, because they loaded their rifles with bullets, silently, and did the same with two others in the wagon, handing us one each without saying a word, which was most eloquent. In this way, the mayoral remained unarmed, and, if we made contact with the bandits, he would find himself reduced to powerlessness. However, after wandering at random for two or three hours, we saw a light far off, gleaming beneath the branches like a glowworm; we immediately made it our pole-star, and headed towards it as directly as possible, at risk of overturning with every yard. Sometimes a crevice in the ground hid it from view, and all of nature seemed extinguished; then the light reappeared, and our hopes with it. Finally, we were close enough to recognise the window of a farm, that being the heaven from which our star shone, in the form of a copper lamp. Ox-carts and agricultural implements scattered, here and there, reassured us utterly, because we might easily have attained some haunt of cutthroats, some posada de barateros. The dogs, having noticed our presence, were barking with the full force of their lungs, so that the whole farm was soon in uproar. The occupants emerged, rifles in hand, to identify the cause of this night-time alarm, and, having seen that we were only honest travellers gone astray, they politely suggested that we enter the farm to rest.

It was these good folks’ supper time. A wrinkled, tanned old woman, somewhat mummified, whose skin was creased at every joint like a hussar’s boot, was preparing a gigantic gazpacho in a red clay bowl. Five or six greyhounds of the tallest size, slender, broad-chested, exquisitely groomed, and worthy of a royal pack, followed the movements of the old woman with the most studious attention and the deepest gaze of melancholy longing one can imagine. But the delicious treat was not for them; in Andalusia, it is men and not dogs who eat soup made from bread-crusts soaked in water. Various cats, the absence of whose ears and tails, for in Spain they are docked of these ornamental superfluities, gave them the look of Japanese chimeras, also gazed, but from a greater distance, at these appetizing preparations. A bowl of the said gazpacho, two slices of our own ham, and a few bunches of grapes the colour of amber, made our supper, for which we were obliged to compete with the invasive familiarities of the greyhounds, who, under the pretext of licking us, literally tore the meat from our mouths. We rose, and ate standing, plate in hand; but the devilish creatures stood on their hind legs, placed their front legs on our shoulders, and so found themselves level with the coveted morsels. If they failed to steal them, they gave them at least two or three licks of the tongue, thus releasing the first, most delicate flavours. These greyhounds seemed to be descended directly from a famous dog, one whose history does not however appear in Cervantes’ writings. That illustrious animal held the role of washer-of-dishes in a Spanish fonda, and, when the servant was reproached because the plates were not quite clean, she swore by the great gods that they had nevertheless been washed by seven streams of water, por siete aquas. Siete Aquas was the name of the dog, so designated because he licked the dishes so closely one would have said they had been washed seven times; he must have neglected to do so that day. The greyhounds on the farm were certainly of that same breed.

We were loaned a young lad as our guide who knew the paths perfectly, and led us without incident to Écija, at which we arrived around ten in the morning.

The entrance to Écija is quite picturesque; you arrive over a bridge at the start of which rises an entry-arch, of triumphant effect. The bridge spans a river which is none other than Granada’s Genil, and which is delayed by the ruins of ancient arches, and the dams for the water-mills; once across, you emerge into a square planted with trees, and decorated with two monuments in a baroque style. One is a statue of the Holy Virgin gilded and set on a column whose hollow base forms a kind of chapel, embellished with tubs of artificial flowers, ex-votos, wreaths woven of strips of reed, and all the trinkets of southern devotion. The other is a gigantic Saint Christopher, also of gilded metal, his hand resting on a palm-tree staff proportionate to his size, carrying on his shoulder, with a most prodigious contraction of muscles and an effort sufficient to lift a house, a tiny Baby Jesus of charming delicacy and appeal. This colossus, attributed to the Florentine sculptor Pietro Torrigiano who broke and crushed Michelangelo’s nose with his fist, is perched on a column of Solomonic order (this is the name given here to such twisted pillars), of soft pink granite, whose spiral terminates midway in volutes and extravagant florets. I have a great liking for statues carved in this way; they produce a finer effect, and can be viewed from further off, to their advantage. Ordinary bases are massive and flat-sided, robbing the figures they support of lightness.

Écija, although absent from the tourist itinerary, and generally little known, is nevertheless a most interesting town, with a specific and original appearance. The bell-towers which form the most acute angles of its outline are neither Byzantine, Gothic, nor Renaissance; they are Chinese, or rather Japanese; you might take them for the turrets of some Miao temple dedicated to Confucius, Buddha, or Fu, because they are entirely clad with porcelain or earthenware tiles coloured in the brightest hues, or with green and white glazed tiles arranged in a checkerboard pattern, granting them the strangest aspect in the world. The rest of the architecture is no less chimerical, the love of over-elaboration being taken to its limits. It is nothing but gilt, incrustations, breccias and coloured marbles like crumpled fabric, nothing but garlands of flowers, love-knots, swollen-cheeked angels, and all this illuminated, painted, with a crazed richness, and in sublime bad taste.

The Calle de los Cabelleros, where the nobility live, and which contains the most beautiful mansions, is truly something wondrous in its way; it is hard to believe one is in a real street, amidst houses inhabited by real beings. Balconies, railings, friezes, nothing is straight, all twists and turns, blossoms in florets, volutes, and chicory-leaves. You cannot find a square inch that is not guillochéd, scalloped, gilded, embroidered, or painted; all that the genre known to us by the name rococo has created of the inharmonious and disordered, with a richness and accumulated wealth of display that good French taste, even in the worst eras, has ever known how to avoid. The presence of this Dutch-Chinese pompadour style in Andalusia amuses and surprises. The run-of-the-mill houses are plastered with lime, of a dazzling whiteness which stands out against the dark azure of the sky in a wondrous manner, and with their flat roofs, narrow windows and miradores, they made me dream of Africa, an idea prompted equally by the temperature of thirty-seven degrees Centigrade, usual for the place in ‘cool’ summers. Écija is known as Andalusia’s ‘oven’, and never has an epithet been better deserved: located on low ground, it is surrounded by sandy hills which shelter it from the wind, and reflect the sun’s rays like concentric mirrors. We lived there in the state of being fried; which did not prevent us from valiantly traversing it, in every direction, while waiting for lunch. The Plaza Mayor presents a very original look with its pillared houses, its rows of windows, its arcades and its projecting balconies.

Our parador was quite comfortable, and we were served an almost decent meal which we savoured with a sensuality that was quite appropriate after so many deprivations. A long snooze in a large, well-shuttered, dark, moist room completed our rest, and when, at around three o’clock, we climbed back into the wagon, we appeared serene and completely resigned.

The road from Écija to La Carlota, where we were to sleep, crosses uninteresting country, with an arid and dusty appearance, or at least the season made it appear so, and has left scant trace in my memory. From far to near, a few olive trees and a few clumps of holm-oaks appeared, while aloes showed their bluish foliage to characteristic effect. The mine-employee’s dog (for we possessed quadrupeds in our menagerie, not counting the children) raised a few partridges, two or three of which were downed by my travelling companion. It was the most remarkable incident of that stage of our journey.

La Carlota, at which we halted for the night, is an unimportant hamlet. The inn occupies a former monastery which had first been transformed into a barracks, as occurs almost always in times of revolution, military life being that which is most easily transferred to and embedded in buildings arranged for monastic life. Long arcaded cloisters formed a covered gallery on all four sides of the courtyards. In the midst of one of them yawned the black mouth of an enormous, and very deep well, which promised the delightful treat of very clear, very cold water. Leaning over the edge, I could see that the interior was lined with the most beautiful green plants which had grown in the gaps between the stones. To find some greenery and some freshness, it was indeed necessary to gaze into the wells, since the heat was such one might have believed it produced by a nearby fire. The temperature inside a greenhouse where tropical vegetation is grown alone gives some idea of the heat. The very air burned, and the gusts of wind seemed to carry igneous molecules. I tried to take a walk outside in the village, but the heat, as if from an oven, that greeted me at the door made me retreat. Our supper consisted of jointed chicken lying higgledy-piggledy on a layer of rice, which was as seasoned with saffron as a Turkish pilau, and a salad (ensalada) of green leaves swimming in a flood of vinegary water, starred here and there by a few dollops of oil undoubtedly stolen from the lamp. This sumptuous meal finished, we were shown to our rooms, which were already so occupied that we ended the night in the midst of the courtyard, in our coats, an overturned chair serving for a pillow. There, at least, we were only exposed to mosquitoes; by donning gloves and veiling our faces with a scarf, we escaped with no more than five or six insect bites. It was merely painful, rather than disgusting.

Our hosts possessed slightly sinister faces; but for a long time now we had ceased to pay attention to such things, accustomed as we were to more or less forbidding visages. A fragment of their conversation that we overheard revealed that their feelings matched their looks. They asked the escopetero, thinking that we understood no Spanish, if there was not an ambush prepared for us a few leagues further on. Our former associate of José Maria replied, with a perfectly noble and majestic air: ‘I will not allow it, since these young gentlemen are in my company; moreover, they anticipated being robbed, and carry with them only an amount strictly necessary for the journey, their money being in bills-of-exchange to be drawn in Seville. Besides, they are both tall and strong; as for the mining employee, he is my friend, and there are four rifles in the wagon.’ This persuasive reasoning convinced our host and his acolytes, who on this occasion were content with the ordinary means of robbery permitted to innkeepers in all countries.

Despite all the dreadful tales of brigands reported by travellers and natives of the country, our adventures were limited to this, the most dramatic incident of our long wandering through regions reputed to be the most dangerous in Spain, at a time certainly favourable to that kind of encounter; the Spanish brigand was for us a purely chimerical being, an abstraction, a simple poetic conceit. We never encountered the shadow of a trabuco, and regarded the idea of thieves with an incredulity equal at least to that of the young English gentleman whose story Prosper Mérimée tells, who, having fallen into the hands of brigands who robbed him, persisted in seeing in them only extras from some melodrama posted there to perform for him.

We left La Carlota at about three in the afternoon, and in the evening lodged in a wretched gypsy hut, the roof of which was constructed simply of branches cut and laid, like a kind of coarse thatch, over transverse poles. After drinking a few glasses of water, I lay down quietly in front of the door, on the breast of our common mother Earth, and, gazing at the azure abyss of the sky in which large stars seemed to hover like swarms of golden bees, stars whose glittering formed a luminous haze similar to that produced around their bodies by the swiftly-beating, and thus invisible wings of dragonflies, it did not take me long to fall into a deep sleep, as though I were lying on the softest bed in the world. However, I had only a stone wrapped in my cloak for a pillow, while a few decent-sized pebbles imprinted themselves on the hollow of my back. Never did a more beautiful and serene night swathe the globe in its blue velvet mantle. Around midnight, the wagon set out again and, when dawn broke, we found ourselves no more than half a league from Córdoba.

One might believe, perhaps, from the description of these halts and stages, that a vast distance separates Córdoba from Málaga, and that we travelled far in a journey which lasted no less than four and a half days. The distance is only about twenty Spanish, or thirty French, leagues; but the wagon was heavily loaded, the road abominable, with no relays available to change mules. Add to this the intolerable heat which would have suffocated both animals and people, if we had ventured forth during the hours when the sun was at full strength. However, the slow and painful journey left us with solid memories; excessive speed when travelling takes away all the charm of the route: you are borne away as if in a whirlwind, without having time to see anything. If you arrive almost immediately, you may as well stay at home. For me, the pleasure of a journey is in travelling not in arriving.

A bridge over the Guadalquivir, the river being fairly wide at that point, serves as an entrance to Córdoba on the Écija side. Nearby can be seen the ruined ancient arches of an Arab aqueduct. The bridgehead is defended by a large square tower, crenellated, and supported by casemates of more recent construction. The city gates were not yet open; a crowd of ox-carts, the oxen majestically crowned with yellow and red esparto-grass tiaras; mules and white donkeys loaded with chopped straw; and countrymen in sugar-loaf hats, dressed in brown wool capas descending in front and behind like a priest’s cope, the head inserted through a hole made in the centre of the fabric, waited for the set hour with the phlegm and patience common to Spaniards, who never seem in a hurry. Such a gathering at a Paris barrier would have caused a dreadful uproar, and would have swelled to invective and insult; there was no other sound here than the tinkle of a copper bell on some mule’s collar, or the silvery ringing of the bell or a leading donkey changing position or resting his head on the neck of a long-eared colleague.

We profited from the pause to examine the interior view of Córdoba at leisure. A beautiful gate, in the style of a triumphal arch of Ionic order, and of such excellent taste that one might have believed it to be Roman, formed a most majestic entrance to the city of the Caliphs, though I would have preferred one of those beautiful Moorish archways flared to a heart-shape, such as we saw in Granada. The mosque-cathedral rose above the walls and roofs of the city more like a citadel than a temple, with its high walls denticulated with Arab battlements, and its heavy Catholic dome squatting on an oriental base. It must be confessed that the walls are painted a quite abominable yellow. Without being one of those people who love mouldy, leprous and blackened buildings, I have a particular horror of that infamous pumpkin hue which so charms priests, factory-owners, and religious chapters everywhere, since they never fail to tarnish in this way all the marvellous cathedrals delivered to them. Buildings must be painted and always have been, even in ancient, and purer, times; but a better choice for the nature and hue of their coating is needed.

At last, the doors were opened, and we experienced the necessary preamble of being inspected quite closely by the customs officers, after which we were free to head, with our trunks, for the nearest parador.

Córdoba has a more African appearance than any other city in Andalusia; its streets or rather its alleyways, whose tumultuous pavements resemble the beds of dry torrents, strewn all over with bits of straw that escape the donkeys’ loads, in no way recall the manners and habits of Europe. One walks there between endless chalk-coloured walls, with sparse windows latticed with grilles and iron-bars, and only encounters some beggar with a forbidding face, some devotee hooded in black, or some majo passing by with the speed of lightning, on his brown horse with a white harness, striking thousands of sparks from the paving stones. The Moors, if they could return, would have little to do on resettling there. The idea that one might have previously formed, when thinking of Córdoba, that of a city with Gothic houses and open-work spires, is entirely false. The universal use of lime-plaster gives a uniform colour to all monuments, fills the wrinkles of their architecture, erases the stone-embroidery and prevents one determining their age. Thanks to the use of lime, a wall made a hundred years ago can scarcely be distinguished from one completed yesterday. Córdoba, once the centre of Arab civilisation, is today nothing more than a cluster of small white houses from which spring a few Indian fig-trees with their metallic greenery, and a few palm-trees with their blooming carapaces of foliage, houses which are divided into islands by narrow corridors through which two mules would have difficulty passing abreast. Life seems to have withdrawn from this vast body, formerly animated by the active circulation of Moorish blood; now all that remains is its bleached and charred skeleton. But Córdoba has its mosque, a unique form of architecture, and completely new even to travellers who have already had opportunity to admire the marvels of Arab architecture in Granada or Seville.

Despite its Moorish appearance, Córdoba is nevertheless a Christian city, and placed under the special protection of the Archangel Raphael. From the balcony of our parador, we saw a rather odd monument raised in honour of that celestial patron; one which we wished to examine more closely. The Archangel Raphael, from the top of his column, sword in hand, wings outstretched, glittering with gilt, seemed a sentinel eternally watching over the city entrusted to his guard. The column is made of grey granite with a Corinthian capital of gilded bronze, and rests on a small tower or lantern of pink granite, the base of which is formed by rockeries on which are grouped a horse, a palm-tree, a lion and a most fantastic sea-monster; four allegorical statues complete the decoration. Inside the base is enshrined the coffin of Bishop Pascual, a character famous for his piety and his devotion to the holy archangel.

On a cartouche one may read the following inscription:

Yo te juro

I swear to you

por

by

Jesu Christo cruzificado

the crucified Jesus Christ

Que soi Rafael angel a quien

That I am the Archangel Rafael to whom

Dios tiene puesto por guarda

God gave the power to protect

de esta ciudad

this city

But, how do we know, you may ask, that the Archangel Raphael was the actual patron of this ancient city of Abd al-Rahman I, he and not another? I will reply by referring to a romance or lament printed, by permission, in Córdoba, by Don Raphael Garcia Rodriguez, on Calle de la Librería (formerly Calle de los Libreros, and now Diario de Córdoba). This precious document bears at the head a woodcut vignette representing the archangel with open wings, a halo around his head, his travelling staff and his emblematic fish in his left hand, majestically encamped between two glorious vases of hyacinths or peonies, the whole accompanied by an inscription thus conceived: Verdadera Relación y Curioso Romance del Señor San Rafael: Arcángel y Abogado de la peste y Custodio de la Ciudad de Córdoba (True Relation and Curious Legend of the Lord Saint Raphael, Archangel, Advocate during the plague, and Guardian of the city of Córdoba).)

It tells of how the blessed archangel appeared to Don Andrés Roelas, gentleman and priest of Córdoba, and addressed him, in his room, in a speech, the first sentence of which is almost exactly the one engraved on the statue’s column. This speech, which the writers of legend have preserved, lasted more than an hour and a half, the priest and the archangel seated face to face, each on a chair. This apparition took place on the seventh of May in the year of Christ 1578, and it is to preserve the memory of this that the monument was erected.

An esplanade surrounded by railings extends all around this construction and allows you to contemplate it from all sides. Statues, thus placed, have something elegant and slender about them which pleases me very much, and which admirably offsets the bareness of a terrace, public square or overly-large courtyard. The statuette placed on a porphyry column, in the courtyard of the Palais des Beaux-Arts, in Paris, may give some slight idea of the advantage that could be gained, in the way of ornamentation, by this manner of placing such figures, which thereby take on a monumental aspect they would otherwise lack. This thought had already occurred to me, in front of the Blessed Virgin, and the Saint Christopher, of Écija.

The exterior of the cathedral appealed to us but little, and we were afraid of being cruelly disenchanted. Those lines of Victor Hugo’s:

Cordoue aux maisons vieilles

Córdoba with its old mansions, many in number,

A sa mosquée, où l'œil se perd dans les merveilles...

Has its mosque, where the traveller’s gaze is lost in wonder…

appeared too flattering to us, in advance of the fact, yet we were soon convinced that they were only just.

It was Caliph Abd al-Rahman I who laid the foundations of the Mosque of Córdoba (the Mezquita), towards the end of the eighth century; the work was carried out with such vigour that the construction was finished at the beginning of the ninth: twenty-one years were enough to complete the gigantic building! When we think that a thousand years ago, a work so admirable and of such colossal proportions was executed in such a short time by a people who later fell into the most savage barbarism, the mind is astonished and refuses to believe in the so-called doctrines of progress that are current today; we even feel tempted to side with the opposite opinion when we visit countries formerly occupied by vanished civilisations. For my part, I have always greatly regretted, as I have said before, that the Moors did not remain masters of Spain, which certainly was the loser by their expulsion. Under their domination, if we are to believe the exaggerated popular legends, so gravely collected by historians, Córdoba possessed two hundred thousand houses, eighty thousand palaces and nine hundred baths; and its suburbs comprised twelve thousand villages. Now it has less than forty thousand inhabitants, and seems almost deserted.

Abd al-Rahman I wished to make the Mosque of Córdoba a destination for pilgrimage, a Western Mecca, the foremost temple of Islam after that in Medina in which the body of the prophet rests. I have not yet seen the kasbah of Mecca, but I doubt whether it equals in magnificence and extent the Spanish mosque. One of the originals of the Koran was once kept there, and, an even more precious relic, a bone from Muhammad’s arm.

The common folk even claim that the Sultan of Constantinople still pays tribute to the King of Spain so that Mass is not said in a place especially dedicated to the prophet. This chapel is ironically called by the devotees the Zancarron, a term of contempt signifying ‘the jaw of an ass, or a rotten carcass.’

The Mezquita is pierced by seven doors which are less than monumental, since its very construction is opposed to such ideas, prohibiting the majestic portal imperiously demanded by the sacramental architecture of Catholic cathedrals, and nothing of its exterior prepares you for the admirable sight that awaits within. We will, if you please, pass through the Patio de los Naranjos, an immense and magnificent courtyard planted with monstrous orange trees, and contemporary with the Moorish kings, surrounded by long arcaded galleries paved with marble, and on one side of which stands a bell-tower in mediocre taste, a clumsy imitation of the Giralda tower in Seville, as we were able to see later. Beneath the pavement of this courtyard, it is said, there is an immense cistern. In the days of the Umayyads, one entered the mosque itself on the same level as the Patio de los Naranjos, because the dreadful wall which blocks the view from without was only built later.

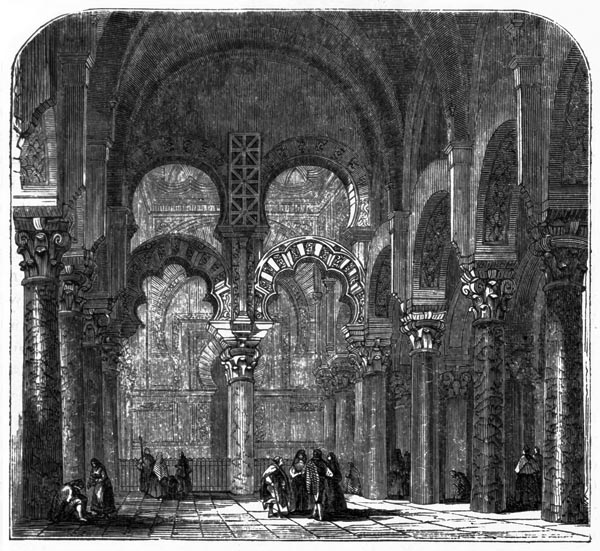

The best idea that we can give of this strange building is to say that it resembles a large esplanade enclosed by walls, and planted with rows of columns at intervals. The esplanade is four hundred and twenty feet wide and four hundred and forty long. The columns number eight hundred and sixty; it is said to cover only half of the original mosque.

The impression one experiences on entering this ancient sanctuary of Islam is indefinable and is unconnected with the emotions that architecture ordinarily causes: it seems more as if one is walking through a roofed forest than a building; whichever way one turns, the eye wanders among avenues of columns which extend and intersect as far as the eye can see, much like marble vegetation springing spontaneously from the ground; the mysterious half-light that reigns in this forest further adds to the illusion. There are nineteen arcades width-wise, thirty-six lengthwise, but the openings to the transverse arcades are much smaller. Each nave is formed of two rows of superimposed arches, which appear to cross and intertwine like ribbons, producing the strangest effect. The columns, all of a piece, are barely more than ten to twelve feet high topped by capitals of an Arabian-Corinthian style full of strength and elegance, which recalls the palm-tree of Africa rather than the acanthus of Greece. They are made of rare marble, porphyry, jasper, green and purple breccia, and other precious materials; there are even some ancient ones which came, it is claimed, from the ruins of an ancient temple of Janus. Thus, three religions’ rites are associated with the place. Of those three religions, one has disappeared irrevocably into the abyss of the past with the civilisation it represented; the second has been driven from Europe, where only one foot remains planted, into the abyss of eastern barbarism; the third, having reached its apogee, undermined by the critical spirit, weakens day by day, even in the countries where it once reigned sovereign and absolute; and perhaps the old mosque of Abd al-Rahman will last long enough to see yet a fourth system of belief arise to dwell in the shadow of its arches, and celebrate a new god with other forms and other rites, or rather a fresh prophet, since the god never changes.

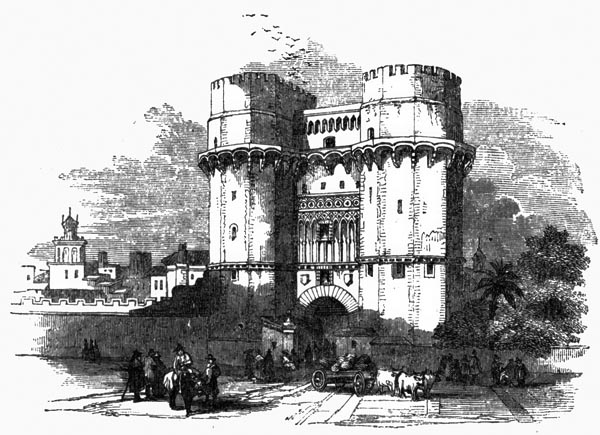

Mosque of Cordova

In the days of the Caliphs, eight hundred silver lamps filled with aromatic oils lit these long naves, making the porphyry and polished jasper of the columns gleam, raising scintillations of light from the golden stars of the ceilings and, drawing from the shadows mosaics of crystal and quotations from the Koran intertwined with arabesques and flowers. Among these lamps were the bells of Santiago de Compostela, conquered by the Moors; upended, and suspended from the vault with silver chains, they illuminated the temple of Allah and his prophet, astonished at having become Muslim lamps rather than the Catholic bells they once were. Our gaze then played freely through the long colonnades and one could view, from the rear of the temple, the orange-trees in flower and the fountains of the patio gushing forth a torrent of light made even more dazzling by the contrast with the semi-darkness of the interior. Sadly, the magnificent perspective is obstructed today by the Catholic church, an enormous mass buried heavily at the heart of the Arab mosque. Altarpieces, chapels, and sacristies complicate and destroy the general symmetry. This parasitic church, a monstrous mushroom of stone, an architectural wart borne on the back of the Arab building, was built to the designs of Hernán Ruiz, and is not without merit in itself; we might even admire it elsewhere, but it is forever regrettable that it occupies the space it does. It was built, despite the resistance of the ayuntamiento, by the chapter, due to an unexpected command from Emperor Charles V, who had never seen the mosque. He said, after visiting it some few years later: ‘If I had known, I would never have allowed the ancient work to be touched: you have built what can be seen everywhere, in a place which can be seen nowhere else.’ This just reproach made the members of the chapter bow their heads, but the damage was done. In the choir one can admire an immense work of carpentry, stalls carved from solid mahogany and representing subjects from the Old Testament, the work of Don Pedro Duque Cornejo, who spent ten years of his life on this prodigious task, as one can read on the tomb of the poor artist, lying on a slab a few steps from his work. Speaking of tombs, we noticed a rather singular one, embedded in the wall; it was shaped like a trunk and closed with three padlocks. How will the corpse, locked up so carefully, open the stone locks of its coffin on the day of the Last Judgment; how will it find the keys in the midst of the general disorder?

Until the mid-eighteenth century, the old ceiling of Abd al-Rahman’s day, made of cedar and larch wood, was preserved with its coffers, its soffits, its diamonds and all its oriental magnificence; it was replaced by vaulting, and half-domes, in mediocre taste. The old paving has disappeared under brick which has raised the level of the floor, submerged the shafts of the pillars, and made the general defects, of a building too low for its size, even more apparent.

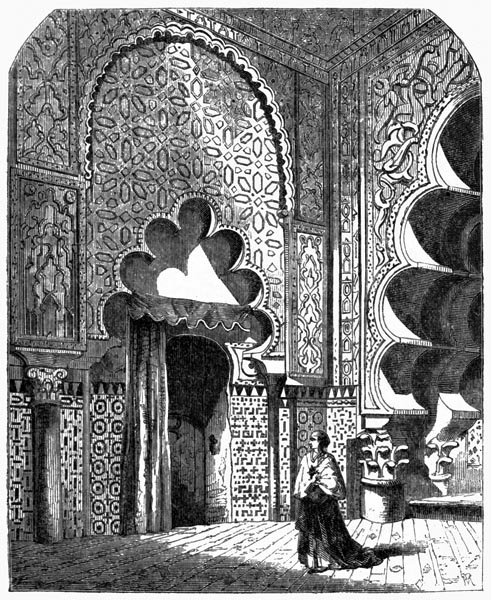

All this desecration does not prevent the mosque of Córdoba from remaining one of the most marvellous monuments in the world; while, as if to make us feel the mutilation of the rest more deeply, a portion, which is called the Mihrab, has been preserved, as if by a miracle, in its original integrity.

The carved and gilded wooden ceiling with its media-naranja studded with stars, the pierced windows furnished with grilles which gently filter the daylight, the arcade of trefoil columns, the mosaics of coloured glass, the verses from the Koran in letters of gleaming gold, which wind among the most gracefully complex ornaments and arabesques, form a whole of a richness, beauty, and magical elegance, the equivalent of which is only found in the Thousand and One Nights, and which yields nothing to any art. Never were lines better chosen, colours better combined: even the Gothic artists, in their finest caprices, in their most precious goldsmith’s-work, betray something unhealthy, emaciated, sickly, which smacks of barbarism and the childhood of art. The architecture of the Mihrab, on the contrary, shows a civilisation at its highest point of development, an artistry at its peak; beyond which lies only decadence. Proportion, harmony, richness and grace, nothing is lacking. From this chapel, one enters a small, excessively-decorated sanctuary, the ceiling of which is made of a single block of marble hollowed out like a conch-shell and carved with infinite delicacy. This was probably the holy of holies, the formidable and sacred place where the presence of Allah seemed more perceptible than elsewhere.

Chapel of the Mosque of Cordova

Another chapel, called the capilla de los reyes moros (la capilla real), where the Caliphs said their prayers, while separated from the crowd of believers, also offers curious and charming details: but it lacks the radiance of the Mihrab, its colours having vanished under an ignoble coat of white.

The sacristies are full of treasure: there are monstrances sparkling with precious stones, silver shrines of enormous weight and incredible workmanship, as large as small cathedrals, candlesticks, golden crucifixes, copes embroidered with pearls: a luxury more than royal and completely Asian.

As we were about to leave, the verger who served as our guide led us, with an air of mystery, to a dark corner, and pointed out, as a supreme curiosity, a crucifix which it is claimed was carved with a fingernail by a Christian prisoner, on a column of porphyry at the foot of which he was chained. To bear witness to the authenticity of the tale, he showed us the statue of the poor captive, a few yards away. Without being more Voltairean than needed as regards legend, I cannot help but think that in the past they had devilishly hard nails, or that porphyry was then extremely soft. This crucifix is not the only one; there is a second one on another column, but much less well-shaped. The verger also showed us an enormous ivory tusk suspended from the centre of a dome by iron chains, like the hunting-trophy of some Saracen giant, some Nimrod from a vanished world; this tusk is said to belong to one of the elephants used to bear the materials during the construction of the mosque. Pleased by his explanation and his complacency, we gave him a few coins, a generosity which seemed to greatly displease the former friend of José Maria, who had accompanied us, and extracted from him this somewhat heretical sentence: ‘Would it not have been better to give the money to a brave bandit rather than a wicked sacristan?’

Leaving the cathedral, we stopped for a few moments in front of a pretty Gothic portal which serves as the facade of the Foundling Hospital. One might admire it anywhere else, but it is eclipsed there by its wondrous neighbour.

Having seen the cathedral, there was nothing to keep us in Córdoba, where our visit had not proved the most stimulating ever. The only entertainment a foreigner can enjoy there is to go swimming in the Guadalquivir, or undergo a shave in one of the numerous barber shops which surround the mosque, an operation which is accomplished with great dexterity, using an enormous razor, its little brother perched on the back of the large oak armchair where you are seated.

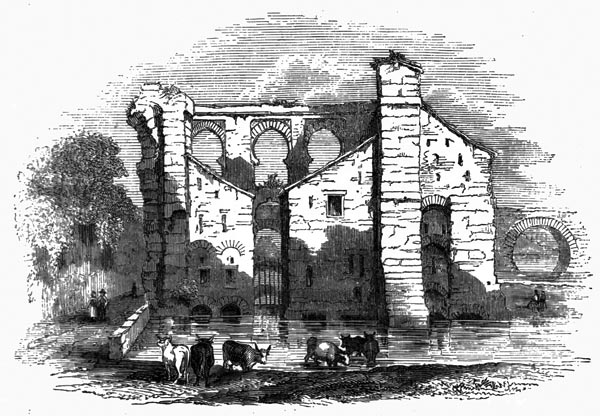

Moorish Mill, Cordova

The heat was intolerable, as it was augmented by flames. The harvest had been completed not long before, and it is the custom in Andalusia to burn the stubble once the sheaves have been gathered, so that the ash fertilises the earth. The countryside was ablaze for three or four leagues around, and the wind, which scorched its wings in passing over this fiery ocean, brought us blasts of hot air like those which escape from the mouths of stoves: we were in the position of those scorpions that children surround with a circle of shavings which they then set on fire, and which are forced to make a desperate exit, or commit suicide by turning their sting on themselves. We preferred the former solution.

The wagon in which we had come brought us back by the same route to Écija, where we sought a two-wheeler to take us to Seville. The driver, having viewed us both, thought us too big, strong and heavy to accept, and made all kinds of difficulties. Our trunks were, he said, so excessively heavy that it would take four men to lift them, and they would instantly damage his carriage. We countered this last objection with the greatest of ease by placing the trunks thus slandered on the rear of the carriage ourselves. The fellow having no more objections to make, at last decided to leave.

Flat or vaguely undulating land, planted with olive-trees, whose grey colour is faded further by dust, and sandy steppes with rounded blackish lumps of vegetation here and there, like the galls on leaves, these are the only objects which offer themselves to one’s gaze for several leagues.

At La Luisiana, the entire population were stretched out in front of their doors snoring beneath the stars. Our carriage roused rows of sleepers who leant against the walls, grumbling, and lavishing on us all the richness of Andalusian vocabulary. We supped in a rather ill-looking posada, stocked with more guns and blunderbusses than household utensils. Monstrous dogs stubbornly followed our every movement, seemingly awaiting the signal before tearing us apart with their teeth. The hostess seemed most surprised at the calm voracity with which we dispatched our tomato omelette. She seemed to find the meal superfluous, and to regret serving food that would be of no benefit to us. However, despite the sinister appearance of the place, our throats were not slit, and they had the clemency to allow us to continue our journey.

We encountered sandier and sandier ground, into which the wheels of the carriage sank up to their hubs. We now understood why our driver had been so concerned with our specific gravity. To relieve the horse, we dismounted and, around midnight, after following a path which climbed, in a zigzag, the steep planes of a mountain, we arrived at Carmona, where our bed awaited. Lime-kilns cast long reddish reflections on this rock-strewn ramp producing Rembrandt-like effects of admirable power and picturesqueness.

The room we were given was decorated with badly-coloured lithographs representing different episodes of our July Revolution of 1830, the storming of the Hôtel de Ville, etc. This pleased us, and almost moved us: it was like a little piece of France framed and hanging on the wall. Carmona, which we barely had time to look at as we clambered back into the carriage, is a small town as white as fresh cream, to which the campaniles and towers of an old convent (Santa Clara) of Carmelite nuns give a rather picturesque appearance: that is all there is to say concerning the place.

From Carmona onwards, the succulents, cacti and aloes, which had abandoned us, reappeared bristlier and more ferocious than ever. The landscape was less bare, less arid, more rugged, the heat had lost a little of its intensity. Soon we reached Alcalá de los Panaderos (Alcalá of the Bakers, now Alcalá de Guadaíra), famous for the excellence of its bread, as its name indicates, and its bullfights involving novillos (young bullocks), attended by aficionados from Seville during the holidays. Alcalá de los Panaderos is well-situated at the bottom of a small valley through which a river (the Guadaíra) winds; it is sheltered by a hill slope, on which the ruins of an ancient Moorish palace still stand. We were approaching Seville. Indeed, the Giralda, the cathedral bell-tower, soon appeared on the horizon, first its windowed lantern was revealed, then its square tower; a few hours later we passed under the Puerta de Carmona (no longer extant), whose arch framed a background of dusty light where wagons, donkeys, mules and ox-carts crossed paths, amidst waves of golden vapour, some arriving, the others departing. A superb aqueduct (Caños de Carmona), of Roman appearance, raised its stone arcades to the left of the road; on the right the houses grew closer and closer together; we were in Seville.

Part XIV: Seville – La Cristina – La Torre del Oro – Italica – The Cathedral – La Giralda – El Polho Sevillano – La Caridad and Don Juan de Marana

There is a Spanish proverb about Seville which is often cited:

Quien no ha vista a Sevilla

Whoever has not seen Seville

No ha vista a maravilla.

Has wonders awaiting them still.

I admit, in all humility, that this proverb would seem more accurate if applied to Toledo or Granada than to Seville, where we found nothing especially wondrous, except the cathedral.

Seville is sited on the banks of the Guadalquivir, in a large plain, and this is where its name Hispalis came from, which means ‘flat ground’ in Carthaginian, if we are to believe the scholars Benito Arias Montano and Samuel Bochart. It is a vast, diffuse city, wholly modern, cheerful, smiling, lively, and must indeed seem delightful to the Spaniards. A greater contrast to Córdoba one could not find. Córdoba is a dead city, an ossuary of houses, an open-air catacomb, over which abandonment sifts its whitish dust; the rare inhabitants who show themselves at the street-corners seem like apparitions who’ve misread the time. Seville, on the contrary, has all the energy and buzz of life: a maddened cloud of noise hovers over it at every instant of the day; Seville barely has time to rest. Yesterday occupies it little, tomorrow even less, it is all of the moment; memory and hope are the recourse of unhappy folk, while Seville is happy: it lives to play, while its sister, Córdoba, seems to dream gravely, in silence and solitude, of Abd al-Rahman, its great captain, and all its vanished splendours, flaming beacons lost in the night, of which only the ashes remain.

To the great disappointment of travellers and antiquarians, whitewash reigns supreme in Seville; the houses don their shirts of lime three or four times a year, which gives them an air of neatness and cleanliness, but conceals from the investigator’s eye the remains of those Arab and Gothic sculptures which formerly decorated them. Nothing could be less varied than this network of streets, where the eye sees only two hues: the indigo of the sky, and the chalk white of the walls, against which the azure shadows of the neighbouring buildings are silhouetted, for in hot countries shadows are always blue and not grey, so that objects seem illuminated on one side by moonlight and on the other by the sun’s rays; however, the absence of any dark tints produces a city full of cheerfulness and life. Doors closed by iron-grilles reveal patios within, decorated with columns, mosaic paving, fountains, flower tubs, shrubs, and frescoes. As for the exterior architecture, it is nothing remarkable; the height of the buildings rarely exceeds two or three stories, and there are barely a dozen facades of artistic interest. The streets are set with small stones like those in all the towns of Spain, but are lined with pavements of fairly-wide flat stone slabs over which the people progress in file; The pavement is always yielded to women, in the event of an encounter, with that exquisite show of politeness natural to Spaniards even of the lowest class. The women of Seville justify their reputation for beauty; they almost all look alike, as is common in pure lineages of a marked type: their eyes slope up towards the temples, are fringed with long brown eyelashes, and produce an effect of light and dark unknown in France. When a woman or a young girl passes you by, she lowers her eyelids slowly, then suddenly raises them, grants you a look of unbearable brilliance, then turns her glance about, and lowers her eyelashes again. The Hindu dancer (bayadère) Amany, when dancing the Pas des Colombes, can alone give an idea of these incendiary glances which the Orient has bequeathed to Spain; we have no terms to express this manoeuvre of the pupils: the verb ojear is missing from our vocabulary. These glances, so bright and abrupt, which almost embarrass the stranger, are of no special significance however, and are focused indifferently on the first object that comes along: a young Andalusian woman will gaze with those passionate eyes at a cart passing by, a dog chasing its tail, or children playing at bullfighting. Compared to theirs, the eyes of the people of the North are dull and empty; therein the sun has failed to leave its reflection.

Pointed canine teeth, which resemble in whiteness those of young Newfoundland dogs, grant something wild and Arabian of extreme originality to the smiles of the young women of Seville. The forehead is high, domed, polished; the nose thin, tending a little to the aquiline; the mouth brightly-tinted. Sadly, the chin sometimes ends in too abrupt a curve, an oval divinely begun. Slightly thin shoulders and arms are the only imperfections that the most demanding of artists could find in the Sevillanas. The fineness of limb, the smallness of the hands and feet, leave nothing to be desired. Without any poetic exaggeration, one could easily find in Seville women whose feet a child could contain in its hand. The Andalusians are very proud of this quality, and wear their shoes accordingly: the similarity between their shoes and Chinese lotus shoes is considerable.

Con primor se calza el pié

A foot that is neatly shod

Digno de regio tapiz

Worthy of a king’s carpet

is a verse of praise as frequent in their romances as a complexion of roses and lilies is in ours.

These shoes, usually made of satin, barely cover the toes, and appear to have no sides or back, being trimmed at the heel with a small piece of ribbon of the same colour as the stockings. In our country, a little girl of seven or eight years old would be unable to wear the shoes of a twenty-year-old Andalusian woman. Thus, they never stop making jokes about the feet and shoes of Northern women: such as ‘with the shoes a German woman wears to a ball, we’d make a boat for six to sail the Guadalquivir’; or ‘a picadores wooden stirrups might serve as slippers for Northern ladies’, and a thousand other andaluzades of this kind. I defended the feet of our Parisian women as best I could, but met only with disbelief. Sadly, the Sevillanas are only Spanish as regards the head and feet, in their mantillas and shoes; dresses in French colours will soon be in the majority. The men are dressed like fashion plates. Sometimes, however, they wear small white cotton jackets with matching trousers, a red belt and an Andalusian hat; but this is rare, while the costume is also far from picturesque.

It is to the Alameda del Duque (Alameda de Hércules), that one goes to breathe some fresh air during the intervals of the theatre, which is close by, and above all to La Cristina, where it is a delight to see the pretty Sevillanas in small groups of three or four, parading about and taking their exercise, between seven and eight in the evening, accompanied by their gallants in attendance or expectation. They have something of a nimble, lively, dashing air, prancing rather than walking. The agility with which their fingers open and close their fans, the brilliance of their gaze, the assurance of their bearing, the undulating suppleness of their waists, gives them a most individual physiognomy. There may be in England, France, or Italy, women of more perfect, more regular beauty, but certainly there are none prettier or more piquant. They possess to a high degree what the Spanish call sal. It is something of which it is difficult to give an idea in France, a compound of nonchalance and liveliness, of bold responses and childish manners, a grace, a spiciness, a ragout, as the painters say, which is something separate from beauty, and often preferred to it. Thus, in Spain they say to a woman: ‘How salty, salada, you are!’ No compliment is worth more.

La Cristina (Jardines de Cristina) is a superb promenade on the banks of the Guadalquivir, with a salon paved with large slabs, surrounded by an immense white marble bench adorned with an iron back, shaded by oriental plane trees, with a labyrinth, a Chinese pavilion, and planted with all kinds of northern trees: ash, cypress, poplar, willow, which are admired by Andalusians, as palm-trees and aloes might be admired by Parisians.

At the borders of La Cristina, pieces of sulphurous cord wound around poles grant a ready light to smokers, so that one is free from the annoyance of those children bearing hot embers who pursue you while crying: Fuego! rendering the Prado in Madrid unbearable.

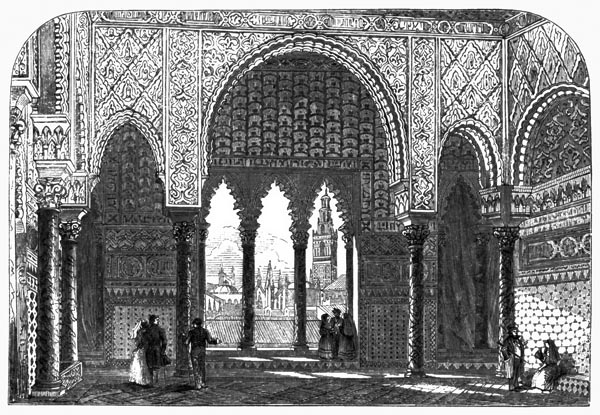

Nonetheless, to this walk, pleasant though it is, I prefer the river-bank itself, which offers a spectacle ever-lively and constantly renewed. Amidst the current, where the water is deepest, are stationed brigs and commercial schooners, with slender masts and rigging, whose dark silhouettes stand out clearly against the lighter background of the sky. Little vessels pass each other on the river in all directions. Sometimes a boat bears a company of young men and women, who descend the river playing the guitar and singing coplas whose rhymes are dispersed by the wild breeze, and whom walkers applaud from the bank. The Torre del Oro, a sort of octagonal tower with two upper stories diminishing in size, and crenellated in the Moorish style, whose foot bathes in the Guadalquivir near the landing stage, and which rises into the azure air amidst a forest of masts and ropes, ends the perspective most happily on the near side. This tower, which scholars claim to be of Roman construction, was formerly connected to the Alcazar by sections of wall which were demolished to make way for La Cristina, and supported, in the days of the Moors, one of the ends of the iron chain which barred the river, and whose other end was attached to the masonry buttresses opposite. The name Torre del Oro comes, it is said, from the fact that gold brought from America by the Spanish galleons was stored there, under lock and key.

Torre del Oro

We walked there every evening, and watched the sun set behind the suburb of Triana, which is on the other side of the river. A palm-tree of noblest form raised its canopy of leaves into the air as if to greet the declining star. I have always loved palm-trees and am never able to see one without feeling transported into the poetic world of the patriarchs, amidst Oriental enchantments, and Biblical magnificence.

Each evening, as if to reawaken our sense of reality, on returning to Calle de la Sierpe (Calle Sierpes), where Don César Bustamente, our host, lived, with his wife, who was Jerez born and had the most beautiful eyes and longest hair in the world, we were accosted by well-dressed fellows, of most decent appearance, with eye-glasses and watch-chains, who asked us to visit, rest and take refreshments with some muy finas, muy decentes people, who had charged them with offering an invitation. These honest people seemed very surprised at first by our refusals, and, thinking that we had not understood, went into more explicit detail; and then, on finding their efforts wasted, contented themselves with offering us cigarettes and sight of ‘the Murillo’, for Murillo, I must tell you, is the honour and also the bane of Seville. His is the only name pronounced there. The meanest bourgeois, the leanest abbot, owns at least three hundred Murillos of the best kind. What is this murky thing? A Murillo in his vaporous style. And this? A Murillo in his warm style. And this third one? A Murillo in his chillier style. Murillo, like Raphael, has three styles, which means that any type of painting can be attributed to him, and leaves admirable latitude to amateurs who wish to fill their galleries. At every street corner, one comes across the corner of a picture-frame: it is a thirty-franc Murillo, which an Englishman would pay thirty thousand francs for. ‘See, sir knight, what design! What colours! It is a perla, a perlita.’ How many pearls have been shown me that were not worth framing! How many ‘originals’ which were not even good copies! That does not prevent Murillo from being one of the most admired painters in Spain, and the world. But here I have strayed far from the banks of the Guadalquivir; let us return there.

A pontoon bridge joins the two banks, and connects the suburbs to the city. Over this, one passes, in order to visit, near the town of Santiponce, the remains of Italica, birthplace of the emperors Trajan, Hadrian and Theodosius and, it is claimed, the poet Silius Italicus. One can view a Circus, in ruins yet still distinctive in shape. The vaults where ferocious beasts were kept, and the gladiators’ stalls, are perfectly recognisable, as are the corridors and stands. All of this is built of cement, with stones embedded in the mixture. The stone cladding was probably pillaged to be used for more modern constructions, since Italica was long Seville’s quarry. Some rooms have been cleared, and serve as refuge, during the hours of scorching heat, for herds of bluish pigs which escape, grunting, between the legs of visitors, and are today the only population of the ancient Roman city. The most complete and interesting vestige which remains of all its vanished splendour is a large mosaic, which has been surrounded by a wall, and which represents the Muses and Nereids. When it is wet with water, its colours are still most brilliant, though, through greed, the most precious stones have been removed. We also found, in the rubble, some statue fragments executed in quite good style, and there is no doubt that skilfully-directed excavations would yield important discoveries. Italica is about a league and a half from Seville, and, by means of a carriage, it is an excursion that one can easily cover in an afternoon, unless one is a fanatical antique dealer, and wishes to examine, one by one, every old stone suspected of bearing an inscription.

The Puerta de Triana (not extant) also has Roman pretensions and takes its name, it is said, from the emperor Trajan. The appearance is monumental; it is of Doric order, with double columns on each side of the arch, and is decorated with the royal arms, and surmounted by a pyramid. It is overseen by its own alcalde (magistrate), and serves as a prison for the nobility. The Puertas del Carbon y del Aceite (not extant) are also worth a look. On the Puerta de Jerez (not extant) the following inscription can be seen:

Hercules me edifico

Hercules first constructed me

Julio Cesar me cerco

Julius Caesar surrounded me

De muros y torres altas

With walls and high towers; at last

El rey santo me gano

Ferdinand the Saint won me,

Con Garci Pérez de Vargas.

Through Garci Pérez de Vargas.

Seville is encircled by crenellated walls, flanked at intervals by large towers, several of which are in ruins, and surrounded by ditches which are now almost entirely infilled. The walls, which would offer scant defence against modern artillery, produce, with their saw-toothed Arabic battlements, a rather picturesque effect. The city’s foundation, like that of every Roman wall and encampment, is attributed, as the verse declares, to Julius Caesar.

In a square neighbouring the Puerta de Triana, I saw a most singular spectacle. It was a family of bohemians camped in the open air, constituting a group that would have delighted Jacques Callot. Three sticks arranged in a triangle formed a rustic tripod, which supported, over a large fire scattering tongues of flame and spirals of smoke in the breeze, a pot with strange and dubious contents, such as Goya might have added to his depictions of the cauldrons employed by the witches of Barahona de las Brujas. Near this improvised hearth, sat a swarthy, copper-skinned gypsy-woman with a hook-nosed profile, and naked to the waist, proving her complete disregard for appearances; her long black hair fell in a wayward manner down her thin, yellow back and over her bistre-coloured forehead. Through her disordered locks gleamed large oriental eyes of mother-of-pearl and jet, eyes so mysteriously contemplative that they grant even the most bestial and degraded physiognomy a poetic quality. Around her, there wallowed three or four squealing brats in a most primitive state, black as mulattoes, with pot-bellies and spindly limbs which made them look more like human quadrupeds than bipeds. No little Hottentot was ever more hideously dirty. Her state of nudity is not rare in Spain and shocks no one. We often met beggars whose only clothing was a scrap of blanket, and haphazard fragments of underclothes; in Granada and Málaga, I saw boys of twelve to fourteen years of age wandering the squares, with less covering than Adam when he left the earthly paradise. The suburb of Triana is full of encounters of this kind, since it contains many gitanos, folk who have the most advanced opinions in matters of casual dress; the women cook in the open air, and the men indulge in smuggling, mule-shearing, horse-trading, etc., when they are not perpetrating something worse.

The Cristina, the Guadalquivir, the Alameda de Duque, Italica, and the Moorish Alcazar, undoubtedly arouse one’s interest: but the real wonder of Seville is its cathedral, which is indeed a surprising building, even after viewing the cathedrals of Burgos and Toledo, and the Mosque in Córdoba. The chapter which ordered its construction summarized their plan of campaign in this sentence: ‘Let us raise a monument that will make posterity think us madmen.’ A splendidly broad aim, and well-executed. Having been granted carte-blanche, in this way, the architects and artists performed wonders, and the canons, to hasten the completion of the building, sacrificed their whole income, reserving only enough to fund the bare necessities required for living. O thrice holy canons! Sleep sweetly beneath your slabs, in the shadow of your beloved cathedral, while your souls bask in paradise, in choir-stalls probably less well sculpted than its own!

The most extravagant, monstrous, prodigiously-sized Hindu pagoda-temples fail to even approach the dimensions of Seville’s cathedral. It is a hollow mountain, an upturned valley; Notre-Dame de Paris could walk with its head upright in the central nave, which is of enormous height; pillars as tall as towers, yet appearing slender enough as to make one shudder, rise from the ground, or hang from the vaults like the stalactites in a giant’s cave. The four side-naves, though less high, could house churches along with their bell-towers. The retablo mayor, or main altar, with its ascending stories, its superposed architecture, its rows of statues filling each level, is an immense construction in itself, rising almost to the vault. The paschal candle, as large as a ship’s mast, weighs two thousand and fifty pounds. The bronze candlestick that supports it is akin to the column in the Place Vendôme; it is an imitation of the candlestick in the Temple of Jerusalem, as it appears on the bas-reliefs of the Arch of Titus; everything is of grandiose proportions. Twenty thousand pounds of wax, and an equivalent amount of oil, are burned each year in the cathedral; the wine which is used for the consumption of the holy sacrifice amounts to a fearful quantity of eighteen thousand seven hundred and fifty litres. It is true, though, that five hundred Masses are said every day at the eighty altars! The catafalque which is used during Holy Week, and which is called the monument, is nearly a hundred feet high. The organs, of gigantic proportions, look like the basalt colonnades of Fingal’s cave, and yet the thunderous hurricanes that escape their pipes as big as siege cannons seem like melodious murmurs, the chirping of birds and seraphim beneath those colossal warheads. There are eighty-three windows with stained glass coloured after cartoons by Michelangelo, Raphael, Durer, Pietro Perugino, Pellegrino Tibaldi and Luca Cambiaso; the oldest and most beautiful were executed by Arnao de Flandes the Younger, a famous glassmaker. The most recent, which date from 1819, show how greatly art has degenerated since the glorious sixteenth century, that supreme era of the world’s art, in which the tree of humanity bore its most beautiful flowers and its most delicious fruits. The choir, in the Gothic style, is embellished with turrets, spires, pierced niches, figurines, and foliage; an immense and meticulously-executed creation which astounds the imagination and can no longer be comprehended today. We remain truly confounded in the presence of such works, and wonder, in deep concern, whether vitality is, with every new century, ebbing from the aging world. This prodigious work of talent, patience, and genius, at least bears the name of its author, and admiration finds someone on whom to focus. On a panel on the Gospel side, the left, is traced this inscription: Este coro fizo Nufro Sanchey entallador que Dios haya año de 1475: ‘Nufro Sánchez, sculptor, whom God has in his care, made this choir in 1475’.

To try to describe the riches of the cathedral, one by one, would be a great folly: it would take a year to view it thoroughly, and one would still not have seen everything; volumes would not suffice to merely create a catalogue. Sculptures in stone, wood, and silver, by Juan de Arphe, Pedro Millán, Juan Montañés, and Pedro Roldán; and paintings by Murillo, Francisco de Zurbarán, Pedro de Campaña, Juan de las Roelas, by Luiz de Vargas, Pedro de Villegas Marmolejo, the Francisco Herreras the Older and Younger, by Juan de Valdès Leal, and by Goya, clutter the chapels, sacristies, and chapter houses. One is so overwhelmed by magnificence, repelled or intoxicated by masterpieces, one no longer knows where to turn; the desire to, and impossibility of, seeing everything provokes a kind of feverish dizziness; you wish to remember everything, yet every minute you sense a name escaping you, a lineament fading from your brain, one painting eclipsing another. Desperate appeals are made to one’s powers of recall, one urges oneself not to omit a single glance; the least rest, the hours for dining or sleeping, seem to be thefts committed against oneself, because a blind imperative necessity drives you onward; and yet soon one must leave, for the steamboat’s boiler has already been fired, the water hisses and boils, the chimneys disgorge their white smoke; tomorrow you will leave all these wonders behind, perhaps never to see them again!

Not having space to speak of everything, I will limit myself to mentioning Murillos’ painting of the Vision of Saint Anthony of Padua, which adorns the baptistry chapel. The magical art of painting has never been taken further. The saint in ecstasy is kneeling in the midst of the cell, all the meagre details of which are rendered with that vigorous reality which characterises the Spanish school. Through a half-open door, we glimpse one of those white arcaded cloisters so conducive to daydreaming. The heights of the painting, drowned in a pale, transparent, vaporous light, are occupied by a group of angels of truly ideal beauty. Attracted by the force of prayer, the Child Jesus descends from the clouds towards the upraised arms of the saint, whose head, raised in a spasm of celestial ecstasy, is bathed in radiance. I place this divine painting above Murillo’s Saint Elizabeth of Hungary Curing the Sick to be viewed at the Academy of Madrid (the Prado), above his Moses Striking the Rock, and above all this master’s depictions of virgin and child, however beautiful and pure they may be. Who has not seen the Vision of Saint Anthony of Padua has not viewed the crowning work of this artist of Seville; it is as if one imagined one knew Rubens yet had never seen, in Antwerp, his Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy.

All the architectural styles meet in Seville Cathedral. The severe Gothic, the Renaissance style, that which the Spaniards call plateresco (plateresque) or goldsmith’s work, and which is distinguished by a madness of ornamentation and indescribable arabesques, the Rococo, the Greek, the Roman; not one is missing, since every century has built its chapel, its retablo, with the taste peculiar to itself, and the building is not even complete, for several of the statues filling the niches of the portals, representing patriarchs, apostles, saints, and archangels, are only made of terracotta and placed there as if provisionally. On the side of the Patio de los Naranjos, at the summit of the unfinished portal, one currently sees a steel crane, symbolic of the fact that the building is unfinished, and that the work is to be renewed later. A like gallows also appears atop the Cathedral of Saint Peter at Beauvais; but when will its weight of stone, slowly hoisted into the air by returning workers, make its pulley, rusted for centuries, creak again? Perhaps never; since the celestial aspiration of Catholicism has ceased, and the sap which caused this flowering of cathedrals to emerge from the soil no longer rises from the trunk to the branches. Faith, which doubts nothing, wrote the first stanzas of all these great poems in stone and granite; reason, which doubts everything, did not dare complete them. The architects of the Middle Ages are like some tribe of religious Titans who piled Pelion on Ossa, not to dethrone the God of thunder, but to admire the gentle figure of the Virgin Mother, smiling at the Child Jesus, more closely. In our age, where all is sacrificed for a crude and stupid feeling of well-being, we no longer understand those sublime pangs of the soul reaching for infinity, translated into spires, needles, arrows, pinnacles, those ogives (pointed arches) stretching their stone arms towards heaven, and meeting, above the heads of the prostrate people, like gigantic hands in supplication. All the neglected cathedral treasures which garner no profit make economists shrug their shoulders pityingly. Even the congregation begins to calculate how much the gold of the ciborium is worth; those who previously did not dare raise their eyes to the gleaming sun of the Host, tell themselves that pieces of glass could perfectly well replace the diamonds and precious stones of the monstrance; Seville’s cathedral is hardly frequented except by tourists, beggars and dreadful old women, atrocious dueñas clad in black, with owl-like faces, skull-like smiles, and spidery fingers, who cannot move without a clicking of aged bones, medals, and rosaries, and who, under the pretext of begging for alms, whisper I know not what terrible proposals in one’s ears, concerning dark hair, ruddy complexions, burning glances, and ever-blooming smiles. Spain itself is no longer Catholic!