Théophile Gautier

Travels in Spain (Voyage en Espagne, 1840)

Parts VII to IX - Madrid

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2024 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

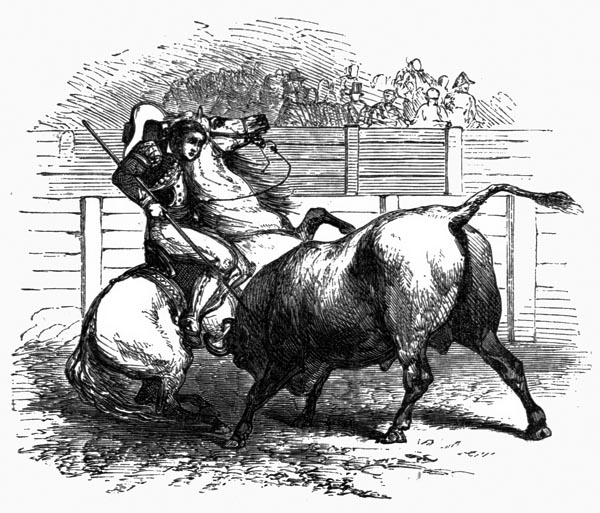

- Part VII: The Bullfight – Sevilla the Picador – The Estocada (Death-Blow) known as Vuela Pies

- Part VIII: The Prado – The Mantilla and the Fan – The Spanish Type – Water-Sellers; The Cafés of Madrid – Newspapers – The Politics of the Puerta de Sol – The Post-Office – The Houses of Madrid – Evening Gatherings (Tertulias) – Spanish Society – The Prince’s Theatre – The Queen’s Palace, that of the National Assembly, and the Monument Commemorating the Second of May 1808 – The Armoury – The Parque de Buen Retiro – Goya

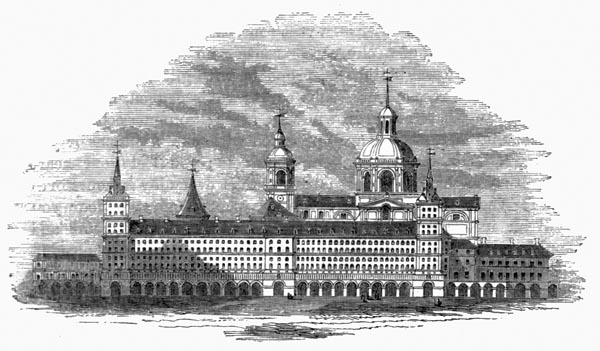

- Part IX: The Escorial – The Thieves

Part VII: The Bullfight – Sevilla the Picador – The Estocada (Death-Blow) known as Vuela Pies

Nonetheless, we still had to wait two days for the bullfight. Never did the hours seem longer to me, and to overcome my impatience I reread, more than ten times, the poster, copies of which were affixed to the corners of the main streets; this poster promised mountains and marvels: eight bulls from the most famous pastures; Sevilla and Antonio Rodriguez, as picadors; Juan Pastor, also called el Barbero, and Arjona Guillen, known as Cúchares, as espadas; all with a notice prohibiting the audience from throwing orange peel into the arena, or other projectiles capable of harming the bullfighters.

In Spain, the word matador, to designate the one who kills the bull, is rarely employed; he is termed the espada (sword), which is a nobler name possessing greater character; nor does one say toreador, but rather torero. I am giving, in passing, this useful information to those who seek to add local colour to their romances and comic-operas. Our bullfight was a media corrida, a half-corrida, since in the past there used to be two, every Monday, one in the morning, the other at five in the afternoon, which made up the entire corrida (coursing of the bulls): the afternoon corrida alone is still performed.

It has been said, and repeated, on all sides, that the taste for the bullfight is waning in Spain, and that civilisation will soon render such events obsolete; if so, it will nonetheless be mourned, as the bullfight is one of the greatest spectacles that can be imagined; but that day has not yet arrived, and sensitive writers who declare the opposite only need to visit the Puerto de Alcalá on a Monday, between four and five o’clock, to convince themselves that the taste for this savage entertainment is not about to be lost as yet.

Monday, the day of the bulls, dia de toros, is a public holiday; no one remains at work, the whole town is in uproar; those who have not yet purchased a seat stride towards the Calle de Carretas, where the ticket office is located, in the hope of securing a vacant place; since, in an arrangement that cannot be praised enough, the enormous amphitheatre is divided into stalls and numbered throughout, a practice that should be imitated in the theatres of France. Calle de Alcalá, which is the artery into which the city’s populous streets discharge, is filled by pedestrians, horse-riders and carriages; it is for this solemn ritual that the most baroque and extravagant calessines and carioles emerge from their dusty sheds, and the most fantastic teams, the most phenomenal mules, come to light. The calessines recall the corricoli (curricles) of Naples: large red wheels, a box without springs, decorated with more or less allegorical paintings, and lined with old damask or tired serge with fringes and frays of silk, achieving a certain rococo air to most entertaining effect; the driver sits on the bench, from where he can harangue, and apply his cane to, his mule at his ease, thus leaving more room for that practice. The mule is adorned with as many feathers, pompoms, tassels, fringes and bells as can be attached to the harness of any quadruped. A calessine usually also contains a manola and her female friend, with her manolo, without prejudice to a bunch of muchachos hanging from the rear. All this flies along like the wind in a tornado of screams and dust. There are also carriages drawn by four or five mules whose equivalents can only be found in the paintings of Adam Frans van der Meulen representing the conquests and hunting expeditions of Louis XIV. Every vehicle is involved, because the great thing among the manolas, who are the grisettes of Madrid, is to travel in a calessine to the Plaza de Toros; they pawn their mattresses to have money for the day, and, without being exactly virtuous the rest of the week, are certainly much less so on Sundays and Mondays. One also sees country-folk arriving on horseback, rifles on their saddles; others alone, or with their wives, on donkeys; all this without counting the carriages of the society people, and a crowd of honest townspeople and señoras in mantillas who hasten onwards; for here is a detachment of the National Guard advancing on horseback, trumpets to their lips, to clear the arena, and not for anything in the world would we wish to miss the emptying of the arena, and the precipitous flight of the alguazil, after throwing the lad in charge the key to the toril where the horned gladiators are imprisoned. The toril faces the matadero, where the slaughtered creatures are skinned. The bulls are brought, on the previous evening and night, to a meadow near Madrid, which is called el arroyo, the destination for aficionados on foot, a walk not without some danger; for the bulls roam freely, and their drivers have a hard time restraining them. Thence they are delivered to the encierro (the arena’s stable), using mature oxen, accustomed to that function, mixed in with the savage herd.

The Plaza de Toros is located on the left, outside the Puerto de Alcalá which, incidentally, is a rather beautiful gate, in the style of a triumphal arch, with trophies and other heroic ornaments; the plaza is an enormous arena appearing nothing remarkable on the outside, whose walls are whitewashed; as everyone buys their ticket in advance, entry takes place without the slightest disorder. Everyone climbs to their place and seats themselves according to their number.

Here follows the interior layout. Around the arena, of truly Roman grandeur, runs a circular barrier, made of planks six-feet in length painted oxblood-red and decorated on each side, which is about two feet from the ground, with a wooden ledge, on which the chulos and banderilleros place their feet in order to jump to the other side when they are pressed too hard by the bull. This barrier is called las tablas. It is pierced with four doors, serving for the entry of the bulls, the removal of carcasses, etc. Behind this barrier, there is another one, a little higher, which forms, with the first, a kind of corridor where tired chulos stand; the picador sobre-saliente (the replacement), who must always be there fully dressed and fully caparisoned in case his leader is injured or killed; the cachatero; and a few aficionados who, through sheer perseverance, manage, despite the regulations, to slip into this blissful corridor whose entrances are as much sought after in Spain as those to the backstage of the Opéra in Paris.

As the exasperated bull often penetrates the first barrier, the second is also furnished with a rope-net intended to prevent a second lunge; several carpenters equipped with axes and hammers stand ready to repair any damage that may result to the fences, so that accidents are virtually impossible. However, we saw bulls of muchas piernas (strong-legged), as they are technically called, penetrating the second barrier, as evidenced by an engraving from La Tauromaquia of Goya, the famous creator of Los Capricos; an engraving (number twenty-one) which represents the death of the mayor of Torrejón de Ardoz, miserably skewered by a rampant bull.

From this second enclosure rise the stands intended for the spectators: those which are near the ropes are called barrera places, those in the middle tendido, and the others which back onto the first row of grada cubiertas, take the name of tabloncillos. These stands, which recall those of the amphitheatres of Rome, are made of bluish granite, and have no other roof than the sky. Immediately after come the covered places, gradas cubiertas, which are divided as follows: delantera, the front; centro, the middle; and tabloncillo, the rear. Above, rise the lodges called palcos, and palcos por asientos, to the number of a hundred and ten. These boxes are large and can accommodate around twenty people. The palco por asientos offers this difference from the simple palco, that you occupy a single seat, like a balcony stall at the Opéra. The boxes of la Reina Gobernadora y de la inocente Isabel are adorned with silk draperies and hidden by curtains. Next to them is the box belonging to the ayuntamiento (municipality) which has charge of the place, and is obliged to resolve any difficulties that arise.

The arena, thus organised, contains twelve thousand spectators, all seated at ease and with a perfect view, something essential in a purely ocular spectacle. The immense enclosure is always full, and those who cannot get sombra seats (places in the shade) would rather be cooked alive on the stands in the sun than miss a bullfight. It is de rigueur, for people who pride themselves on elegance, to have their box at the Taureaux, as in Paris, a box at Le Théâtre des Italiens.

On emerging from the corridor to find my seat, I felt a sort of dazzled vertigo. Torrents of light flooded the arena, for the sun has a superior lustre and the advantage of not shedding oil, which gas itself will not eclipse for a long time yet. An immense murmur floated above the arena, like a mist of noise. On the sunlit side, thousands of fans and small round parasols fixed to reed-sticks throbbed and sparkled; it looked like a swarm of birds of varying colour attempting to take flight: there was not a single empty space. I assure you that it is a more than admirable spectacle to view twelve thousand spectators in a theatre so vast that only the deity can paint its ceiling that splendid blue drawn from the urn of eternity.

The National Guards on horseback, very well mounted and very well dressed, toured the arena, preceded by two alguazils in costume, with plumes and hats in the style of Henri IV, black jerkins and capes, and riding boots, chasing before them a few stubborn aficionados and a few stray dogs. The arena remaining empty, the two alguazils went to seek out the toreros, consisting of the picadores, the chulos, the banderilleros and the espada, the main actor in the drama, who made their entrance to the sound of a fanfare. The picadores rode horses which had been blindfolded, as the sight of the bull could frighten them and cause a dangerous situation for them all. The picador’s costume is very picturesque: it consists of a short jacket, which does not button, of orange, crimson, green or blue velvet, burdened with gold or silver embroidery, sequins, piping, fringes, filigree buttons and decorations of all kinds, especially on the shoulder pads where the fabric completely disappears under a luminous and phosphorescent jumble of intertwined arabesques; a waistcoat in the same style, a frilled shirt, a colourful and carelessly knotted tie, a silk belt, and tawny buffalo-skin pants padded, and lined with sheets of metal internally, like a postilion’s boots, to defend the legs against blows from the bull’s horns; a grey hat (sombrero) with an enormous brim, low in shape, embellished with an enormous tuft of favours; a large bun, or cadogan of black ribbons, which is called, I believe, a moño, and which ties the gathered hair behind the head, completes the adjustment. The picador’s weapon is an iron-shod spear with a point one or two inches long; this spear is unable to cause the bull any grievous harm, but is enough to irritate and deter it. An inch of leather tailored to the picador’s hand prevents the spear from slipping; the saddle is very high in front and behind, and resembles the steel-clad harness in which knights of the Middle Ages were encased for tournaments; the stirrups are made of wood and form sabots, like Turkish stirrups; a long iron spur, sharp as a dagger, arms the horseman’s heel; to direct the horses, often only half-alive, no ordinary spur would be sufficient.

Sevilla the Picador

The chulos possess a very agile and gallant air, in their short satin breeches, green, blue or pink, embroidered with silver on all the seams, their white or flesh-coloured silk stockings, their jackets decorated with designs and motifs, their tight belts, and their hats, monteras, tilted coquettishly towards the ear; They bear cloth capes (capas) on their arm, which they unfurl, and flutter in front of the bull to irritate, dazzle, or confuse it. They are well-shaped, lean and slender young people unlike the picadores who are generally noted for their tall height and athletic shape: some require strength, others agility.

The banderilleros wear a similar costume, their specialty consisting of planting sticks equipped with iron barbs, and embellished with strips of paper, into the shoulders of the bull; these pointed darts are called banderillas, and are intended to revive the bull’s fury, and arouse in him the degree of exasperation needed for him to present himself correctly to the matador’s sword. The banderillero must set two banderillas in place at a time, and to do this must pass both of his arms between the horns of the bull, a delicate operation during which any distraction might prove dangerous.

The espada differs from the banderilleros only in his richer, more decorative costume, sometimes of purple silk, a colour particularly displeasing to the bull. His weapons are a long sword with a hilt in the form of a cross, and a piece of scarlet cloth sewn onto a transverse rod; the technical name for this kind of fluttering shield is a muleta.

Here then you have the theatre and the actors; we will now display them in action.

The picadores escorted by the chulos first salute the box belonging to the ayuntamiento from which the keys of the toril are thrown down to them; the keys are collected, and handed to the alguazil, who takes them to the lad appointed for the fight, who races away at full speed; all this amid the jeers and cries of the crowd, since the alguazils, like all the representatives of government, are hardly more popular in Spain than are the gendarmes and city officials among us. Meanwhile, the two picadores place themselves to the left of the gates of the toril which faces the queen’s box, since the exit of the bull is one of the most interesting features of the bullfight; they are posted at a short distance from each other, leaning against the tablas, secure in their saddles, spears in hand, and prepared to receive the savage beast in a most valiant manner; the chulos and banderilleros remain at a distance or scatter themselves about the arena.

All these preparations, which take longer to describe than in reality, ignite one’s interest to the highest degree. All eyes are fixed anxiously on the fatal door, and among these twelve thousand glances there is not one turned in any other direction. The most beautiful woman on earth would scarcely receive a glance at that moment.

I admit that, for my part, my heart was gripped as if by an invisible hand; my temples were moist, and hot and cold sweats ran down my back. It was one of the strongest emotions I have ever felt.

A loud fanfare sounded, the two red doors were released with a crash, and the bull rushed into the arena amidst an immense cry from the audience.

The bull was a superb animal, almost completely black and gleaming, with an enormous dewlap, a square muzzle, sharp and polished crescent-shaped horns, slender legs, and a tail constantly in motion, bearing between his shoulders a tuft of colourful ribbons of his Ganaderia (cattle-ranch), fixed into the hide with a needle. He stopped for a second, sniffed the air two or three times, dazzled by the broad daylight, and astounded at the tumult; then, spotting the first picador, he rushed towards him at a gallop with furious momentum.

Sevilla, was the picador so attacked. I cannot resist the pleasure of describing here the renowned Sevilla, truly the ideal of his kind. Imagine a man about thirty years old, with a grand manner and fine figure, robust as a Hercules, swarthy as a mulatto, with superb eyes and a physiognomy like one of Titian’s Caesars; the expression of jovial and disdainful serenity which reigned in his features and his posture, in truth, possessed something heroic. On that day, he was wearing an orange jacket embroidered and interlaced with silver, which remains inscribed in my memory in indelible detail: he lowered the point of his spear, stood stock still, and withstood the shock of the bull so impressively, that the savage beast staggered, and passed by, bearing a wound which soon streaked his black hide with crimson; he halted, seeming uncertain, for a few moments, then rushed with added rage upon the second picador posted some distance away.

Antonio Rodriguez dealt the bull a good blow of the spear, which opened a second wound immediately adjoining the first, since one must only stab at the shoulder; but the bull returned on him headlong and plunged its entire horn into the horse’s belly. The chulos came running, shaking their capes, and the foolish beast, attracted and distracted by this new bait, began to chase them at full speed; but the chulos, setting foot on the ledge of which we have spoken, jumped lightly over the barrier, leaving the animal most surprised at their vanishing.

The blow from the bull’s horn had split the horse’s belly, so that its entrails spilled out and flowed almost to the ground; I thought the picador would retire to mount another: not in the least; he touched the animal’s ear to see if the blow was likely to be fatal. The horse was only unseamed; the wound, though dreadful to look on, could be healed; they replaced the intestines in the horse’s belly, added two or three stitches, and the poor creature was fit for another bout. The rider gave him the spur, and, after a brief gallop, placed himself further away.

The bull began to comprehend that little more than a spear thrust was to be gained from the picadores, and felt the desire to return to his pasture. Instead of charging without hesitation, he returned, after a few paces, to his querencia with an air of imperturbable obstinacy; the querencia, in terms of the art of the bullfight, is any corner of the place that the bull chooses to rest in, and to which he always returns after having attempted the cogida; a goring by the bull is termed the cogida, while the torero’s pass is termed the suerte, or diestro.

A swarm of chulos came, waving brightly coloured capas before the bull’s gaze; one of them pushed his insolence so far as to cover the bull’s head with his rolled-up cape, which thus resembled the sign outside Le Bœuf à la Mode, which everyone in Paris must have noted. The furious bull rid himself of this untimely ornament as best he could, and sent the innocent fabric flying into the air, trampling it in rage when it fell to the ground. Taking advantage of his increased wrath, a chulo began to taunt him and draw him towards the picadores; finding himself face to face with his enemies, the bull hesitated, then, choosing his target, rushed on Sevilla with so much force that the horse rolled over with all four shoes in the air, for Sevilla’s arm proved a buttress of bronze that nothing could move. Sevilla fell beneath the horse, which is for the best, since the man is protected from a blow from the bull’s horn, and the body of his mount serves as a shield. The chulos intervened, and the horse was left with only a cut to the thigh. Sevilla was helped to his feet, and returned to the saddle with perfect tranquility. The horse ridden by Antonio Rodriguez, the other picador, was less fortunate: it received such a violent blow in the chest that the horn sank in up to the hilt, and vanished entirely within the wound. While the bull tried to free his head from the horse’s body, Antonio clung with his hands to the edge of the tablas which he traversed with the help of the chulos, since the picadores, once unhorsed, weighed down by the steel fitments of their boots, can no more move than could Medieval knights encased in their armour.

The poor horse, left to his own devices, began to stagger across the arena, as if he were drunk, entangling his feet in his bowels; streams of black blood gushed impetuously from his wound, and streaked the sand with intermittent zigzags which betrayed the unevenness of his gait; finally, he approached, and collapsed close to, the tablas. He raised his head two or three times, rolling one already glazed blue eye, drawing back his lips whitened with foam, which revealed his bony teeth; his tail beat weakly on the earth; his hind feet moved convulsively and launched a last kick, as if he wanted to break the dense skull of death with his hard hoof. His agony was barely over when the muchachos on duty, seeing the bull was occupied elsewhere, ran to remove the saddle and bridle. The horse remained lying on his side, disembowelled, and forming a dark silhouette on the sand. He was so thin, so flattened, that one might have taken him for a cut-out made of black paper. I had already noted, at Montfaucon, what strangely fantastic forms horses take in death: without doubt, the corpse of such a creature is the saddest one can view. The head, so nobly and purely structured, now gripped and laid flat by the dreadful hand of nothingness, seems as if once inhabited by human thought; the dishevelled mane, the outspread tail, have something picturesque and poetic about them. A dead horse is a corpse; any other animal whose life is spent merely a carcase.

I emphasise the death of the horse, because it delivered the most painful sensation I experienced while watching the bullfight. It was not, however, the only victim: fourteen horses occupied the arena that day; a single bull killed five of them.

The picador returned with a fresh horse, and there were several more or less successful exchanges. But the bull began to tire and his fury to subside; the banderilleros arrived with their barbed darts lined with paper, and soon the bull’s neck was adorned with a collar of these, which the efforts he made to free himself fixed even more immovably. A little banderillero, named Majaron, thrust in his darts with great delight and audacity, and sometimes even beat an entrechat with his feet before retiring; he was therefore greatly applauded. When the bull had seven or eight banderillas trailing from him, whose iron barbs tore his hide and whose paper rustled in his ears, he began to run here and there, bellowing frightfully. His black muzzle was white with foam, and, in the intoxication of his rage, he dealt such harsh blows with his horn against one of the doors that he sent it flying from its hinges. The carpenters, who followed his movements with their gaze, immediately replaced it; a chulo attracted the bull from another direction, and was pursued so vigorously that he barely had time to leap the barrier. The bull, exasperated and enraged, made a prodigious effort and rode over the tablas. Those who found themselves in the corridor leapt about where they were with marvellous agility, and the bull was returned to the arena through another door, driven back with canes and hats by the spectators in the front row.

The picadores withdrew, leaving the field open to the espada, Juan Pastor (‘El Barbero’), who went to salute the box belonging to the ayuntamiento, and ask permission to kill the bull; permission being granted, he threw his hat, his montera, in the air, as if to show that he was going to exert his all, and marched towards the bull with a deliberate step, concealing his sword beneath the red folds of his muleta.

The espada fluttered the scarlet cloth, towards which the bull was blindly rushing, several times; a slight movement of his body was enough for him to avoid the momentum of the fierce beast, which soon returned to the charge, violently butting its head against the light fabric which it moved without being able to pierce it. The favourable moment having arrived, the espada placed himself straight in front of the bull, waving his muleta with his left hand, and holding his sword horizontally, the point at the height of the animal’s horns; it is difficult to convey in words the degree of interest, full of anguish, the frenetic attention which this situation arouses, one worth all of Shakespeare’s dramas; in a few moments, one of the two actors will be killed. Will it be the man, or the bull? They are both there, face to face, alone; the man has no defensive armour; he is dressed as if for a ball, in pumps and silk stockings; a woman’s pin would pierce his satin jacket; he possesses a scrap of cloth, a frail sword, that is all. In this duel, the bull has all the material advantage: he has two dreadful horns, sharp as daggers, immense power when in motion, the anger of a brute unaware of danger; yet the man has his sword, and his courage, and twelve thousand eyes fixed on him; and beautiful young women will soon applaud him, with the tips of their white fingers!

The muleta was moved aside, leaving the matador’s chest exposed; the bull’s horns were only an inch from his chest; I thought him lost! A flash of silver passed, with the rapidity of thought, between the twin crescents; the bull fell to his knees uttering a bellow of pain, with the hilt of the sword between his shoulders, like Saint Hubert’s stag bearing a crucifix between the base of its antlers as represented in that marvellous engraving by Albrecht Durer.

Thunderous applause echoed throughout the amphitheatre; the palcos of the nobility, the gradas cubiertas of the bourgeoisie, the tendido of the manolos and manolas, erupted, and vociferated, with all the ardour and exuberance of the south: Bueno! Bueno! Viva El Barbero! Viva!!!

The blow that the espada had just delivered is, in fact, highly esteemed and is called the estocada a vuela piés: the bull dies without losing a drop of blood, which is the height of elegance, and falling to his knees seems to recognise the superiority of his opponent. The aficionados (dilettanti) claim that the inventor of this move was Joaquín Rodríguez Costillares, a famous bullfighter of the eighteenth century.

If the bull does not die instantly, one sees a small mysterious fellow, dressed in black, leap the barrier; one who has taken no part in the preceding events: he is the cachetero. He advances in a furtive manner, observes the bull’s final convulsions, determines if he is still capable of rising, which is sometimes the case, and treacherously thrusts into him, from behind, a cylindrical dagger tipped with a lance-head, which severs the spinal cord, and ends the bull’s life with the speed of lightning; the correct placement is behind the head a few inches from the base of the horns.

Military music announced the death of the bull; one of the doors opened, and four mules magnificently harnessed, with plumes, bells, woollen tassels, and small yellow and red flags, in the colours of Spain, trotted into the arena. This team is equipped to remove the carcasses which are attached to the end of a rope fitted with a grappling-iron. First the horses were dragged away, then the bull. Those four brightly-adorned and sonorous mules which drew over the sand, at a furious speed, all those corpses which had themselves been racing about so furiously a moment ago, had a strange wild appearance, which somewhat concealed the lugubrious nature of their function; a lad arrived with a basket of earth which he sprinkled on the pools of blood in which the bullfighters’ feet might slip. The picadores resumed their places next to the door, the orchestra played a fanfare, and another bull rushed into the arena; because this show has no interval, nothing delays it, not even the death of a torero. As I have said, their understudies are already there fully dressed and armed in case of accident. It is not my intent to recount, successively, the death of the eight bulls which were sacrificed that day; but I will mention a few noteworthy variants and incidents.

The bulls are not always so ferocious; some are even quite gentle and ask nothing better than to lie down quietly in the shade. One perceives, from their honest and good-natured appearance, that they prefer their pasture to the arena: they turn their backs on the picadores and, most phlegmatically, allow the chulos to shake capes of all colours in front of their noses; the banderillas are not even enough to rouse them from their apathy; it is therefore necessary to resort to violent means, to banderillas de fuego: these are a kind of firework-dart, which flare up a few minutes after being planted in the shoulders of the cobarde (cowardly) creature, and burst forth in energetic sparks and detonations . The bull, by this ingenious invention, is therefore at the same time pricked, burned, and stunned: even if he is the most aplomado (leaden) of bulls, he cannot but choose to be enraged. He indulges in a host of extravagant antics, which one would not credit such a heavy beast of being capable; he roars, he foams, and twists in all directions to free himself from the ill-placed fireworks that fry his ears and scorch his hide.

The banderillas de fuego are only employed, however, in the last extremity; it is a mark of dishonour, if the bullfighters are obliged to resort to them; but when the alcalde takes too long to wave his handkerchief as a sign of his consent, there is such a commotion that he is forced to yield. There are unimaginably loud cries and vociferations, howls, and the stamping of feet. Some shout for the Banderillas de fuego! Others for the Perros! Perros! (the dogs). They heap insults on the bull; he is called a brigand, an assassin, a thief; they offer him a place in the shade, they make him the butt of a thousand jests, often very witty. Soon a chorus of canes, beaten against the woodwork, join the vociferations which have become insufficient. The planks of the palcos creak and split, and the paint from the ceilings descends in whitish films like snow mingled with dust. The audience’s exasperation rises to its peak: Fuego al alcalde! Perros al alcalde! (fire and dogs take the alcalde)! shout the enraged crowd, shaking their fists at the box reserved for the ayuntamiento. At last, the blessed permission is granted, and calm restored. In these kinds of shouting-matches, pardon the term, since I can’t think of a better one, quite clever jokes are sometimes made. I will report a quite brief and vivid one: a picador, magnificently dressed in a brand-new outfit, was resting on his horse without doing anything, and at a place in the arena where he was in no danger. Pintura! Pintura! cried those members of the crowd who noticed his lack of movement – A painting! A painting!

Often the bull is so cowardly that even the banderillas de fuego are insufficient. He returns to his querencia and refuses to engage. The cries of: Perros! Perros! start up again. Then, after a sign from the alcalde, messieurs les chiens are introduced. They are admirable creatures, of an extraordinary purity of breed, and great beauty; they rush straight at the bull, who tosses half a dozen into the air, but who fails to prevent one or two of the strongest and bravest dogs from ending up by grabbing his ear. Once they have taken hold, they are like leeches; one could drag them backwards without making them let go. The bull shakes his head, knocks them against the barriers: nothing helps. When this has lasted for some time, the espada, or the cachatero, thrusts a sword into the side of the victim, who staggers, bends his knees and falls to the ground, where he is then done to death. They also, on occasion, employ a kind of instrument called a media luna (half-moon), which severs his hind hocks and renders him incapable of any resistance; then it is no longer a fight, but a disgusting act of butchery. It often happens that the matador’s blow misses its target: the sword strikes a bone and recoils, or it enters the throat and makes the bull vomit blood in large quantities, which is a grave fault according to the laws of tauromaquia. If at the second blow the beast is not despatched, boos, whistles and insults, are heaped on the espada, for the Spanish public is an impartial one; it applauds the bull and the man according to their respective merits. If the bull disembowels a horse and fells a man: Bravo toro! if it is the man who wounds the bull: Bravo torero! but it refuses to tolerate cowardice either in man or beast. One poor devil, who did not dare dart the banderillas into an extremely ferocious bull, excited such tumult that the alcalde was forced to promise to have the man imprisoned so that order could be re-established.

During this same bullfight, Sevilla, who is an admirable picador, was greatly applauded for the following action: a bull of extraordinary strength caught his horse beneath the belly, and, raising its horns, lifted him completely from the ground. Sevilla, in this perilous position, scarcely wavered in his saddle, kept his feet in the stirrups, and managed his horse so well that it fell back onto all four feet.

The bullfight had been excellent: eight bulls, and fourteen horses killed, one chulo slightly injured; we could not have wished for anything better. Each session must bring in twenty or twenty-five thousand francs; the amount is granted by the queen to the main hospital, where injured toreros find all imaginable manner of help; a priest and a doctor, wait in a room in the Plaza de Toros, ready to administer, one, remedy to the soul, the other, remedy to the body; I believe a Mass used to be said, and still is, for them during the bullfight. You can see that, clearly, nothing is neglected, and that the impresarios are people of foresight. When the last bull has been slain, all the folk leap into the arena to view it more closely, and the spectators then retire, discussing the merits of the different suertes or cogidas which most impressed them. And the women, you will ask me, what of them? Is that not one of the first questions asked of the traveller? I confess I know nothing about it. I seem to recall, vaguely, that there were some very pretty ones not far from me, but cannot affirm it with any degree of certainty.

Let us visit the Prado, to clarify this important point.

Part VIII: The Prado – The Mantilla and the Fan – The Spanish Type – Water-Sellers; The Cafés of Madrid – Newspapers – The Politics of the Puerta de Sol – The Post-Office – The Houses of Madrid – Evening Gatherings (Tertulias) – Spanish Society – The Prince’s Theatre – The Queen’s Palace, that of the National Assembly, and the Monument Commemorating the Second of May 1808 – The Armoury – The Parque de Buen Retiro – Goya

When one speaks of Madrid, the first two ideas that the name awakens in the imagination are the Prado and the Puerta del Sol: since we have the inclination to do so, let us go to the Prado; at the hour when the promenade begins. The Prado, comprising several alleys and side-alleys, with a roadway in the middle for vehicles, is shaded by tall and stocky trees, the bases of which bathe in a narrow pool bordered by bricks, to which channels bring water at specific hours; without this precaution they would soon be consumed by dust and scorched by the sun. The promenade begins at the monastery of Atocha, passes in front of the gate of that name, then the Alcala Gate, and ends at the Recoletos Gate. But the fashionable world haunts the space circumscribed by the fountain of Cybele and that of Neptune, from the Alcala Gate to the Carrera de San Jerónimo. The large space there is called the salon, lined with chairs, like the main avenue of the Tuileries; on the side of the living room, there is a side alley which bears the name Paris; it is the city’s Boulevard de Gand (now the Boulevard des Italiens), and Madrid’s fashionable meeting-place; and, as the imagination of fashionable people does not exactly chime with the picturesque, they have chosen the dustiest, least shaded, least convenient place on the whole promenade. The crowd is so large in this narrow space, squeezed between the salon and the roadway, that it is often difficult to put one’s hand in one’s pocket to extract a handkerchief; you have to conform, and follow the line like a queue at the theatre (in the days when theatres saw queues). The only thing that could have led to this place being selected is that one can see and greet people in their carriages traversing the roadway (it is always honourable for a pedestrian to salute a carriage). The equipages are less than brilliant; most of them are dragged by mules whose blackish coats, full bellies, and pointed ears have a most unsightly effect; they look like mourning carriages following a hearse: the carriage of the queen herself is quite simple and bourgeois. An Englishman with pretensions of being a millionaire would certainly disdain it; no doubt, there are exceptions, but they are rare. What does charm the eye are those fine Andalusian saddle-horses, seated on which the most fashionable people of Madrid parade about. It is impossible to view anything more elegant, nobler, or more graceful than an Andalusian stallion with his beautiful erect mane, long, well-furnished tail which descends to the ground, harness decorated with red tufts, arched head, glowing eyes, and neck bulging like a pigeon’s throat. I saw one ridden by a woman, as pink in colour (the horse, not the woman) as a Bengal rose glazed with silver, and of marvellous beauty. How great the difference between these noble beasts which have retained their beautiful primitive form, and those locomotive ‘machines’ of muscle and bone which we call English coursers; and which feature no more of the equine than four legs and a backbone to support a jockey!

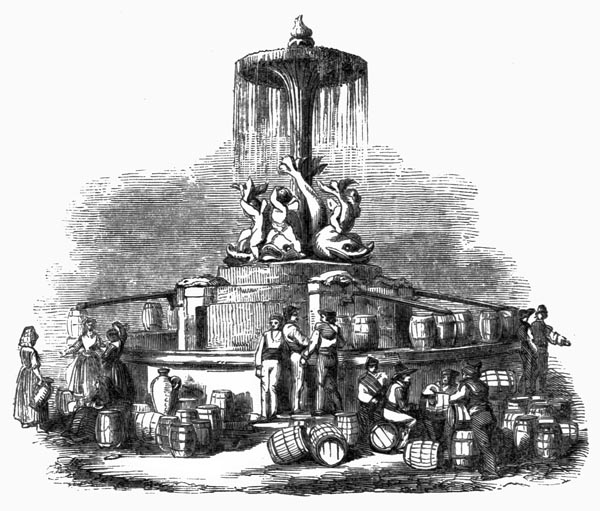

Fountain at Madrid

The spectacle embodied by the Prado is truly one of the liveliest that can be seen, and it is one of the most beautiful promenades in the world, not regarding its location which is quite ordinary, despite all the attempts that Charles III of Spain made to correct that defect, but because of the astonishing crowds that attend there every evening, from half past seven to ten o’clock.

One sees very few women’s hats along the Prado; with the exception of a few sulphur-yellow pancakes, which must once have adorned educated donkeys, there are only mantillas. The Spanish mantilla is therefore a reality; I had thought it only existed in the romances of Monsieur Crevel de Charlemagne: it is woven of black or white lace, more often black, and is placed over the back of the head on top of the comb; a few flowers set on the temples complete this hairstyle which is the most charming imaginable. With a mantilla, a woman would need to be as ugly as the three theological virtues not to appear pretty; sadly, this is the only part of the Spanish costume that has been retained: the rest is à la francaise. The last folds of the mantilla rest on a shawl, an odious shawl, and the shawl itself is accompanied by a dress of ordinary material, which in no way resembles a basquin. I cannot help being astonished at such blindness, and I do not understand why women, ordinarily clairvoyant as regards their beauty, do not realise that this, their supreme effort at elegance, exhibits merely provincial pretension, with mediocre results. The ancient native costume is so perfectly suited to the beauty, proportions, and manners of Spanish women that it is surely the only garb possible. The fan somewhat corrects this pretension to Parisianism. A woman without a fan is something I have not yet seen in this happy country; I saw women with satin shoes and no stockings, but they carried a fan; the fan accompanies them everywhere, even to church where you meet groups of women of all ages, kneeling, or squatting on their heels, who pray and fan themselves with fervour, interspersing everything with Spanish signs of the cross, which are much more complicated than ours, and which they execute with a precision and speed worthy of Prussian soldiers. Manoeuvring the fan, is an art completely unknown in France. The Spanish excel at it; the fan opens, closes, turns in their fingers, so quickly, so lightly, that a conjurer could do no better. Some elegant folk create collections of fans at great cost; we saw one that contained more than a hundred different styles; from every country and every era: ivory, tortoiseshell, sandalwood, sequined fans, fans painted in gouache from the days of Louis XIV and Louis XV, rice-paper fans from Japan and China, no style was lacking; several were studded with rubies, diamonds and other precious stones: it is a luxury in good taste, and a charming hobby for a pretty woman. The fans as they open and close produce a little whistling sound which, repeated more than a thousand times a minute, projects its note through the confused noise which enwraps the promenade, and contains something alien to a French ear. When a woman meets a person she knows, she grants them a little wave of the fan, and emits in passing the word agur (good evening) which is pronounced abour. Now let me address the subject of Spanish beauty.

Ladies on the Prado

What is understood in France as the Spanish type does not exist in Spain, or at least I have not yet encountered it. We usually imagine, when we say the words señora and mantilla, an elongated and pale oval face, large black eyes surmounted by velvety eyebrows, a thin, slightly-arched nose, a pomegranate-red mouth, and, above all, a warm and golden tone justifying the Romantic phrase: She is yellow as an orange. That is the Arab or Moorish type, not the Spanish type. The Madridleñas are charming in the full sense of the word: out of every four there are always three pretty ones; but they in no way correspond to the idea we have of them. They are small, neat, well turned-out, with slim feet, arched waists, and breasts rich in contour; but they have extremely white skin, delicate and lined features, and heart-shaped mouths, and exactly mimic certain Regency portraits. Many have light brown hair, and you cannot take two turns on the Prado without meeting seven or eight blondes of all shades, from ash-blond to a red as vehement as the red beard of Charles V. It is an error to believe that there are no blondes in Spain. Blue eyes abound there, but are not as greatly esteemed as black ones.

At first I had some difficulty accustoming myself to viewing women with low necklines as if for a ball, with bare arms, satin shoes on their feet, flowers on their heads, and fans in their hands, walking alone in a public place, because there one does not offer a woman one’s arm, unless one is her husband or a close relative: one must be content to walk beside them, at least as long as it is daylight, though after dark they are less rigorous about this etiquette, especially with foreigners who are unused to it.

We have heard great praise bestowed on the manolas of Madrid: the manola is a type that has vanished like the Parisian grisette, and the trasteverine of Rome; she still exists, but stripped of her primitive character; she no longer displays so bold and picturesque a costume; ignoble Indian cotton has replaced those skirts in dazzling colours embroidered with exorbitant motifs; the frightful leather shoe has displaced the satin slipper, and, dreadful to think of, the dress has lengthened by a good two finger-widths. In the past they relieved the drab appearance of the Prado with their lively looks and singular costume: today it is difficult to distinguish them from petty-bourgeois women and tradesmen’s wives. I searched for a sign of the purebred manola in every corner of Madrid, at the bullfight, at the Jardin de las Delicias, at the Nuevo Recreo, at the feast of Saint Anthony, and never came across a perfect example. Once, while walking through the Rastro quarter, the Temple district of Madrid, and having passed a large number of beggars who were lying asleep on the ground clothed in dreadful rags, I found myself in a small deserted alley, and there I saw, for the first and last time, the sought-after manola. She was a tall, well-built girl, of about twenty-four years old, the highest age at which girls may still be termed manolas or grisettes. She had a dark complexion, a strong, sad look, a somewhat coarse mouth, and something African in the lines of her face. An enormous braid of hair, blue by dint of being almost black, braided like the rushes of a basket, coiled around her head and attached itself to a large tortoiseshell comb; clusters of coral hung from her ears; her tawny neck was adorned with a necklace of the same material; a black velvet mantilla framed her head and shoulders; her dress, as short as that of the Swiss women of the Canton of Berne, was made of embroidered cloth, and revealed thin, sinewy legs enclosed in well-made black silk stockings; her shoes were satin, in the traditional fashion; a red fan trembled like a cinnabar butterfly between fingers laden with silver rings. The last of the manolas turned the corner of the alley, and vanished before my eyes, amazed at having seen, if only the once, an Opéra character in a Henri Duponchel costume, alive and walking about the real world! I also saw at the Prado some pasiegas from Santander in their national costume; these pasiegas are reputed to be the best nursemaids in Spain, and their affection towards children is as proverbial as the probity of Auvergnats in France; they have a skirt of red cloth with large pleats, bordered with a wide braid, a black velvet corset also braided with gold, and for hairstyle a madras variegated with dazzling colours, the whole accompanied by jewellery, silver, and other native coquetries. These women are very beautiful, possessing a most striking air of strength and grandeur. The habit of rocking children in their arms gives them an upright, arched attitude which encourages chest development. Viewing a pasiega in costume is a species of luxury comparable to having a klepht ride behind your carriage.

As yet I have said nothing regarding the male mode of dress: consult the fashion plates published six months ago, in some tailor’s shop, or reading room, and you will gain a perfect idea. The thought of Paris occupies everyone, and I remember seeing on a shoe-shiner’s stall: ‘Boots polished here in the Parisian style (estilo)’ Paul Gavarni’s delightful designs are the modest aim of the modern hidalgo: ignorant of the fact that only the finest Parisian dandies can achieve it. However, to do the men justice, we must say that they are far better dressed than the women: they are as varnished, as white-gloved as possible. Their clothes are correct, and their trousers commendable; but the tie is not of the same excellence, and the waistcoat, the only part of the modern costume where fantasy can be displayed, is not always in impeccable taste.

There is a trade in Madrid that we lack the idea of in Paris: that of the retail water-seller. His ‘shop’ consists of a cántaro (pitcher) of white clay, a small basket, woven from rushes or made of tin, which contains two or three glasses, a few azucarillos (sticks of caramelized and porous sugar), and sometimes a couple of oranges or lemons; others have small barrels surrounded by foliage which they carry on their backs; some, along the Prado for example, even have illuminated counters topped with yellow-copper emblems and flags that are in no way inferior to the magnificence of the coco-sellers of Paris (coco being a herbal tea made of liquorice and lemon water). These water-sellers are usually young Galician muchachos in tobacco-coloured jackets, and short trousers, with black gaiters, and a pointed hat; there are also a few Valencianos with their white canvas breeches, their cloth cape worn over the shoulder, their tanned legs and their alpargatas (sandals) edged with blue. A few women and little girls, in insignificant costumes, also sell water. They are called, according to their sex, aguadores or aguadoras; from every corner of the city one can hear their high-pitched cries, modulated in all tones, and varied in a hundred thousand ways: Agua, agua, quien quiere agua? Agua helada, fresquita como la nieve! This lasts from five in the morning till ten in the evening; These same cries inspired Breton de Los Herreros, an esteemed poet of Madrid, to write a song called La Aguadora, which gained success throughout Spain. The lack of water in Madrid is truly an extraordinary thing: all the output from the springs, all the snow from the mountains of Guadarrama, fails to suffice. There are many pleasantries spoken about the poor Manzanarès, and its naiad’s dry urn; I would like to see the appearance of the river in any other city consumed by such thirst. The Manzanarès is drunk from at source; the aguadores anxiously look for the least sign of water, the slightest humidity, to appear between its dry banks, and carry it away in their cantaros and siphons; the laundresses wash clothes with sand, and even in the midst of its river-bed a Muslim would lack the means to perform his ablutions. No doubt you remember that delightful article by Joseph Méry on the lack of water in Marseille, multiply it sixfold and you will have but a slight idea of Madrid’s thirst. A glass of water sells for a cuarto (a few sous); what Madrid needs most, after water, is a coal to light its cigarettes; the cry: Fuego, fuego, is heard on all sides and mingles incessantly with the cry of: Agua, agua. The struggle between the two elements is fierce, it being a question of which can make the greater noise: the fire, more inextinguishable than that of the Roman goddess Vesta, is carried by young people in small cups, full of coals and fine ash, equipped with a handle so as not to burn the fingers.

Now it is half-past nine, the Prado’s population is beginning to disperse, and the crowd are heading towards the cafés and botillerias (refreshment places) which line the long Calle de Alcalá and the surrounding streets.

The cafés of Madrid seem to us, who are accustomed to the dazzling and magical luxury of the cafés of Paris, to be, in truth, drinking dens of the lowest order; the manner in which they are decorated is reminiscent of those booths in which bearded women and live mermaids are shown; yet this lack of luxury is more than compensated for by the excellence and variety of the refreshments served there. It must be admitted that Paris, so superior in everything, is behind in this respect: the art of the café-owner here is still in its infancy. The most famous cafés are La Bolsa, on the corner of Calle de Carretas; Nuevo, where the exaltados (radicals) meet; the café... (I forget the name), a customary gathering-place for people who belong to moderate opinion, whom they term cangrejos, that is to say crabs; and Levante, close to the Puerta del Sol; which is not to say that others are inferior; merely that these are the most frequented. And let us not forget the Café del Principe, next to the theatre of that name, a common meeting-place for artists and writers.

We will enter the Café de la Bolsa, if you wish, which is decorated with small mirrors cut in intaglio beneath, so as to form designs, as we see in certain pieces of German glassware: here the menu consists of bebidas heladas, sorbetes and quesitos. The bebida helada (frozen drink) is contained in glasses that can be distinguished as grande or chico (large or small), and a wide variety is offered; there is the bebida of naranja (orange), of limon (lemon), of fresa (strawberry), and of guindas (cherries), which are also as superior to those awful jugs of sour redcurrant and citric acid that they are not ashamed to serve you in Paris, in the most splendid of cafés, as genuine sherry is to authentic wine from Brie: the bebida is a kind of liquid ice, a snowy puree with the most exquisite taste. The bebida de almendra blanca (white almonds) is a delicious drink, unknown in France where we swallow, under the pretext of sipping barley-syrup, I don't know what abominable medicinal mixtures; it is also offered as iced milk, half strawberry or cherry, which, while your body is boiling in the torrid zone, allows your throat to enjoy all the frost and snow of Greenland. During the day, before the iced drinks are available, there is agraz, a type of drink made from green grapes and contained in bottles with oversized necks; the slightly tangy taste of agraz is most pleasant; you can also drink a bottle of cerveza de Santa Barbara con limon; but this requires a degree of preparation: first a bowl and a large spoon are brought, like that with which punch is stirred, then a waiter approaches carrying the beer-bottle, fastened with wire, which he uncorks with infinite care; the cork pops, and one pours the beer into the bowl, into which one has previously emptied a carafe of lemonade, then one stirs everything with the spoon, fills one glass and swallows. If you dislike such mixtures, you need only enter the chufas horchaterías, usually run by Valencians. The chufa (tigernut) is a small tuber, from a species of sedge, grown in the neighbourhood of Valencia, which is roasted and crushed, and from which an exquisite drink is made, especially when mixed with snow: this preparation is extremely refreshing.

To complete the menu, allow me to say that sorbetes differ from those in France in possessing more consistency; that quesitos are small hard ice-creams, moulded in the shape of a cheese: there are all kinds, made with apricots, pineapples, oranges, as known in Paris; but they are also made with butter (manteca) and with as yet unformed eggs, removed from the bodies of disembowelled hens, which is a method unique to Spain, since I have only ever heard of this singular refinement in Madrid. One is also served chocolate, coffee and other spumas; these are a type of whipped ice-cream, in nature extremely light, and sometimes sprinkled with very finely grated cinnamon; accompanied by barquilos, biscuits rolled into long cones with which you taste your bebida, as with a straw, by sucking slowly through one of the ends; a small refinement which allows you to enjoy the freshness of the beverage for longer. Coffee is not offered in cups, but in glasses; it is quite rarely taken otherwise. All these details may seem tedious to you; but, if like us you were exposed to heat of thirty to thirty-five degrees Centigrade, you would find them of the greatest interest. One sees many more women in the Madrid cafés than in those of Paris, though cigarettes and even Havana cigars are smoked there. The newspapers most frequently found in them are the Eco del Comercio, the Nacional and the Diario, which prints the events of the day, the times of masses and sermons, the temperature, and notices regarding lost dogs, young peasant girls looking to be employed as nursemaids, parlour maids seeking a position, etc., etc. – But now eleven o’clock strikes; it is time to retire; Barely a few lingering strollers line the Calle de Alcalá. The streets are occupied only by the serenos with their lantern on the end of a pike, their coat the colour of a stone wall, and their measured cry; all you can hear is a chorus of crickets singing, in little cages adorned with beads, their disyllabic lament. In Madrid, they have a taste for crickets: each house has its own, in a miniature cage made of wood or wire hanging in the window; they also have a strange passion for quails which they keep in slatted wicker-baskets, and which, with their eternal pick-per-wick, provide a pleasant alternative to the crick-crick of the crickets. As is said of the cup-and-ball game, those who like the sound must be exceedingly tolerant.

The Puerta del Sol is not a gate, such as one might imagine, but rather a church facade, painted pink and embellished with a clock-dial lit at night, and a large sun with gilded rays, hence the name Puerta del Sol. In front of this church, there is a kind of square or crossroads; where the length of the Calle de Alcalá is crossed by the Calle de Carretas, and the Calle de la Montera. The Post Office, a large formal building, occupies the corner of the Calle de Carretas, with its facade facing the square. The Puerta del Sol is a meeting-place for the city’s idlers, and many there appear to be, since a dense crowd occupies it from eight in the morning. All those grave personages, stand about, wrapped in their coats, despite it being excruciatingly hot, under the frivolous pretext that what protects against cold must also protect against heat. From time to time, we see emerge, from the motionless folds of a cape, a thumb and index finger, yellow as gold, rolling a papelito, containing a few pinches of chopped tobacco, and soon from the mouth of the grave personage a cloud of smoke rises, which proves that he is endowed with lungs, which one might have doubted given his perfect immobility. Speaking of papel espanol para cigaritas, let me note in passing that I have not yet seen a single booklet of cigarette-papers; the natives of the country use ordinary writing paper cut into small pieces; all such liquorice-tinted booklets, with grotesque colourful drawings and the texts of letrillas (little lyric verses) or farcical romances, are exported to France, to our lovers of local colour. Politics is the general topic of conversation; the theatre of war greatly occupies their imaginations, and more strategy is composed at the Puerta del Sol than on all the battlefields, and in all the campaigns in the world. Juan Manuel Balmaseda, Ramón Cabrera, the Palillos brothers, and other more or less important guerilla leaders, may reappear on the scene at any moment, tales are told of things that make one shudder, cruelties that are outdated, and have long been considered tasteless by the Caribs and the Cherokees. Balmaseda, in his last campaign, advanced to within twenty leagues of Madrid, and, having surprised a village near Aranda del Duero, amused himself by breaking the teeth of the ayuntamiento and the alcalde, and concluded the entertainment by having horseshoes nailed to the feet and hands of a constitutional priest. As I expressed my astonishment at the perfect tranquility with which this story was received, I was told that it took place in Old Castile, and there was thus no need to worry about it. This reply sums up the entire situation in Spain, and provides the key to many things which seem incomprehensible to us, when viewed from France. Indeed, for an inhabitant of New Castile, what happens in Old Castile is as uninteresting as what occurs on the moon. Spain does not yet exist as a united entity, it is still Las Españas: Castile and Leon, Aragon and Navarre, Granada and Murcia, etc.; folk who speak different dialects and cannot stand each other. As a naive foreigner, I protested at such refinements of cruelty; but it was pointed out to me that the priest was a constitutional priest, which greatly attenuated the matter. Baldomero Espartero’s victories, victories which seem mediocre to us, accustomed as we are to the colossal battles of the empire, frequently serve as a text for the politics of the Puerta del Sol. Following such triumphs, where a couple of men were killed, three prisoners taken, and a mule, bearing a sabre and a dozen cartridges, was seized, fireworks were lit, and oranges or cigars, arousing an enthusiasm easy to conceive, distributed to the soldiers. In the past, grandees visiting the shops near the Puerta del Sol, on being granted a seat, remained there for a large part of the day, chatting to the customers, to the great displeasure of the owners, distressed by such a mark of familiarity; and they still do so, even today.

Let us, if you please, visit the Post Office to see if there are any letters from France; this pre-occupation with letters is truly unhealthy; you may be sure that on arriving in a city, the first building a traveller will visit is the post office. In Madrid, letters marked poste restante are each given a number; this number and the name of the recipient are written on a list which is displayed on pillars; there is a pillar for January, for February, and so on; you look for your name, make a note of the number, and request your letter at the depot, where it will be delivered to you without any further formalities. After a year, if a letter has not been claimed, it is burned. Under the arcades of the Post Office courtyard, shaded by large blinds made of esparto-grass, every sort of reading-room is established, as under the arcades of the Odéon in Paris, and there one may read the Spanish and foreign newspapers. Postage charges are not very great, and, despite the innumerable dangers to which the mail is exposed on its journey, the roads being almost always infested with rebels or bandits, the service is maintained as regularly as possible. It is also on these pillars that offers of service are displayed, by poor students, who seek to polish one’s riding boots in order to complete their courses in rhetoric or philosophy.

Let us now traverse the city at random, since chance is the best of guides, especially in Madrid which is not rich in architectural splendour, and where one street is as interesting as another. The first thing you see when you gaze up at the corner of some house or street, is a small earthenware plaque on which is written: Visita. G(eneral). Manzana. and a number ‘n’ (indicating block ‘n’, on the general visitation route for tax purposes). These plaques were formerly used to number the houses, grouped into islands or blocks. Today everything is numbered as in Paris. You would also be surprised at the various plaques proclaiming ‘Asegurada de incendios’ (insured against fire) adorning the facades of houses, especially in a country where there are no chimneys, and where fires are never lit. Everything is insured, even the public monuments, even the churches; the civil war, it is said, is the cause of the great eagerness for such insurance (which funded teams of firefighters); since no one can be sure they will not be more or less roasted alive by some Balmaseda or other, all try at least to save their homes.

The houses in Madrid are constructed with lath, bricks, and adobe, except for the jambs, masonry-piers, and corbels, which are sometimes of grey or blue granite, and are all carefully plastered and painted in rather fanciful colours, celadon-green, ash-blue, buff, canary-tail yellow, rose pompadour, and other more or less anacreontic hues; the windows are framed by decorations, and simulated architectural features, with many a volute, scroll, little cupid, or vase of flowers; and adorned with Venetian blinds striped in wide blue and white bands, or esparto-grass matting which is watered to charge the breeze that passes through it with humidity and freshness. The wholly modern houses content themselves with being plastered with lime, or whitewashed with milk-white paint, like those in Paris. The projecting balconies and miradores break somewhat their monotonous straight lines, casting sharp shadows, and varying the naturally flat aspect of buildings all of whose projecting reliefs are painted and treated like theatre decorations: illuminate all of this with a glowing sun, plant at various distances, in these streets flooded with light, a few señoras in long veils holding their fans, spread in the manner of parasols, against their cheeks; a few sunburnt, wrinkled beggars, draped in shreds of canvas, and mossy rags; a few half-naked Valencians with the appearance of Bedouins; and bring forth, from between the roofs, the small humped domes, and bulging pinnacles ending in lead cones, of a church or monastery, and you will obtain an interesting enough view; one which will prove to you that you are, at last, no longer in the Rue Laffitte, and that you have definitely left the asphalt behind, even if your feet torn by the sharp stones of Madrid’s pavements have not already convinced you of the fact.

One thing that truly surprises is the frequency of the following inscription: Juego de villar, which recurs every twenty steps. Lest you imagine that there is something mysterious in these three sacred words, I hasten to translate them: they only mean Billiard Parlour. I cannot understand what the devil the need is for so many billiards tables; the whole universe could take a turn. After the juegos de villar the most frequent inscription is that of despacho de vino (wine-shop). Val-de-Peñas and other full-bodied wines are sold there. The counters are painted in vibrant colours, decorated with draperies and foliage. The confiterías (confectioneries) and pastelerías (baker’s-shops) are also numerous and quite attractively decorated: the Spanish confitures deserve a particular mention; those known as angel-hair (cabello de angel) are exquisite. The pastry is as good as it can be in a country where there is little butter, or at least it is so expensive and of such poor quality that it can hardly be used; it is close to what we call petit-four pastry. All the street signs are written in abbreviated characters, the letters intertwined with each other, which initially makes them difficult to understand for foreigners, the great readers of signs, if ever there were any.

The house interiors are vast and comfortable; the ceilings are high, and space is nowhere constrained; in Paris an entire house would be built in the shafts of certain staircases; you traverse long lines of rooms before arriving at the section that is actually inhabited; all these rooms being decorated only with lime plaster or in a flat yellow or blue shade, enhanced with coloured strips and panels of simulated woodwork. Paintings, darkened by smoke, of a blackish hue, representing the beheading or disembowelling of some martyr, a favourite subject of Spanish artists, hang from the walls, most of them unframed and merely tacked to their stretchers. Parquet is something unknown in Spain, or at least I have never seen it there. All the rooms are tiled with brick; but, as the bricks are covered with matting, of reeds in winter and rushes in summer, the inconvenience is greatly reduced; these reed and rush mats are woven with great taste; the natives of the Philippines or the Sandwich Islands could do no better. There are three things which for me are precise thermometers of the state of civilisation of a people: pottery, the art of weaving either wicker or straw, and the method of harnessing beasts of burden. If the pottery is beautiful, of pure form, correct as in ancient times, with the natural hues of pale or red clay; if the baskets and mats are finely made, skilfully woven, enhanced with arabesques of admirably chosen colours; if the harnesses are embroidered, stitched, and decorated with bells, woollen tassels, designs of the most discerning choice, you can be sure that the people are primitive and still very close to the state of nature: civilised people have no idea how to make pottery, or matting, or a harness. As I write, I have in front of me, hanging from a pillar by a string, the jarra that is filled with the water I have to drink: it is an earthen pot worth twelve quartos, which is to say about six to seven French sous; the shape is charming and I know of nothing purer except the Etruscan. The rim is flared, and forms a four-leafed clover, each leaf hollowed out like a spout, so that you can pour water from whichever one you wish; the handles, fluted with a small moulding, attach with perfect elegance to the neck and sides, in a delightful curve; to these charming vases, fashionable people prefer those abominable English containers, swollen, pot-bellied, humped, and coated with a thick layer of glaze, which one might take for riding boots polished with whiting. But, in speaking of boots and pottery, I stray far from my description of domiciles; let me return to them without further ado.

The small amount of furniture that is found in Spanish homes is in dreadful taste, reminiscent of Messidor taste or Pyramide taste. The art of the Empire flourishes there in all its integrity. Here you will find those mahogany pilasters terminating in the heads of sphinxes in green bronze, those copper rods and framed Pompeii garlands, which have long since disappeared from the face of the civilised world; not a single piece of furniture sculpted in wood, not a table inlaid with mother-of-pearl, not a lacquer cabinet, nothing; ancient Spain has vanished completely: only a few Persian carpets and damask curtains remain. On the other hand, there is an abundance of truly extraordinary chairs and sofas of straw; the walls are defaced by false columns, false cornices, or daubed with some tint of tempera paint. Scattered about the tables and shelves are little biscuit-fired or porcelain figurines representing troubadours, or the opera-characters Mathilde and Malek Adel, or other equally ingenious subjects fallen into disuse; poodles in spun glass, plated candlesticks garnished with candles, and a hundred other magnificent items which it would take too long to describe, but of which what I have said above must offer sufficient token; I lack courage to speak of the atrocious illuminated engravings that possess the misplaced pretension of embellishing the walls.

There may be a few exceptions to all this, but the number is small. Nor should you imagine the homes of upper-class people as being furnished with greater taste and opulence. The description, applies with the most scrupulous accuracy, to the houses of those with carriages and eight or ten servants. The blinds are always lowered, the shutters half-closed, so that the apartments are left with a third of the usual daylight, something one must get used to, in order to discern objects, especially when one enters from outside; those who are in the room see perfectly, but those who have arrived are blind for eight or nine minutes, especially when one of the previous rooms is fully lit. It is said that skilful mathematicians have calculated the optics required for perfect comfort during an intimate tête-à-tête in an apartment so arranged. The heat is excessive in Madrid, it comes on suddenly without the usual transition to spring; and they say of the temperature in Madrid: ‘three months of winter, nine months of hell’. One can only shelter oneself from this storm of fire by staying in the lower rooms, where almost complete darkness reigns, and where perpetual moistening maintains the humidity. This need for freshness gave rise to the fashion for búcaros, which would seem a strange and savage refinement offering nothing pleasurable as regards our French amours, but which seems a most desirable thing in the best taste to lovely Spanish women.

Búcaros are a kind of vase, in red earthenware from America similar to that from which the chimneys of Turkish pipes are made; they come in all shapes and sizes; some are decorated with threads of gilt and strewn with roughly painted flowers. As they are no longer made in America, búcaros are becoming rare, and in a few years will be as unobtainable, and legendary as old Sèvres ware; then everyone will want one.

To deploy búcaros, one places seven or eight of them on marble pedestals or corner tables, fill them with water, and seat oneself on a sofa to wait for them to produce their effect, so as to savour the pleasure while meditating appropriately. The clay takes on a darker shade, the water penetrates its pores, and the bucaros soon exude and spread an aroma resembling the smell of wet plaster, or a damp cellar that has remained unopened for a length of time. This transpiration of the búcaros is so profuse that after an hour half the water has evaporated; that which remains in the vase is cold as ice, and has acquired a taste of wells and cisterns which is quite nauseating, but which is found delicious by its aficionadas. Half a dozen búcaros are enough to permeate the air of a boudoir with such humidity that it strikes you when you enter; it is a kind of cold vapour-bath. Not content with smelling the aroma and drinking the water, some people chew small fragments of búcaros, reduce them to powder, and end up by swallowing them.

I attended a few evening gatherings, or tertulias; there is nothing remarkable about them; people dance to the piano as in France, but in an even more modern and more lamentable way, if possible. I cannot imagine why people who dance so little do not, instead, resolve to abandon dancing completely; which would be simpler and just as amusing. Their fear of being accused of favouring the bolero, the fandango, or the cachucha renders the women perfectly immobile. Their costume is very simple, compared to that of the men, who are always dressed like fashion plates. I made the same remark at the Palace of Villa-Hermosa, at a performance for the benefit of foundlings (niños de la cuna), attended by the queen mother, the ‘little queen’, and all the grand and beautiful people Madrid contains. Women who were duchesses two times over, and marquises four times, wore dresses that, in Paris, a milliner visiting a dressmaker’s house would disdain; they no longer know how to dress in the Spanish, but do not yet know how to dress in the French manner, and, if they were not so pretty, would often run the risk of appearing ridiculous. Only once, at a ball, did I see a woman in a pink satin basquin, trimmed with five or six bands of pale black, like that of Fanny Elssler in Alain-René Lesage’s Le Diable Boiteux; but she had danced in Paris, where the Spanish costume had been revealed to her. Tertulias cannot cost much to those who give them. Refreshments are conspicuous by their absence: no tea, no ices, no punch; only a dozen glasses of perfectly clear water, and a plate of azucarillos, on a table in the main salon; while one would be taken generally for an indiscreet man, and sur sa bouche (a glutton), as Henri Monnier’s Madame Desjardins would say, if one took the Sardanapalian to the point of sweetening one’s water with sugar; that only occurs in the wealthiest houses: it is not out of miserliness, merely that such is the custom; moreover, the ascetic sobriety of the Spaniards is perfectly adapted to this regime.

As regards morals, it takes one more than six weeks to understand the character of a people and the customs of a society. Nonetheless, novelty creates a first impression which may fade during a long stay. It seemed to me that women in Spain had the upper hand, and enjoyed greater freedom than in France. The attitude of the men towards them seemed to me most humble and submissive; they render them service with scrupulous exactitude and punctuality, and express their passion in poems of every measure, rhyming and assonant, sueltos (blank verse) and others; from the moment they have placed their hearts at the feet of a beautiful woman, they are only permitted to dance with their great-grandmothers. The conversation of women of fifty years of age, and of noted ugliness, alone is granted them. They can no longer make visits to houses where there is a young woman: a frequent visitor vanishes suddenly and reappears after six months or a year; his mistress has forbidden him the house: he is received as if he had been there the day before; this is quite accepted. As far as one can judge at first glance, Spanish women are not capricious in love, and the relationships they form often last several years. After a few evenings spent at a gathering, the couples are easily discernible, being visible to the naked eye – if you wish to receive Madame X, you must invite Monsieur Y, and vice versa; the husbands seem admirably civilised, and a match for the most good-natured of Parisian husbands: with no sign of the ancient Spanish jealousy, which is the subject of so many dramas and melodramas. To completely dispel all illusions, everyone speaks perfect French, and, thanks to those few elegant people who spend the winter in Paris, and make visits backstage at the ballet, the puniest little Opéra ‘rat’ (trainee), the most insignificant little marcheuse (extra), are perfectly well-known in Madrid. There I found what exists perhaps in no other place in the universe, a passionate admirer of Mademoiselle Louise Fitzjames, whose name will serve as a transition from the tertulia to the theatre.