Théophile Gautier

Travels in Spain (Voyage en Espagne, 1840)

Parts I to III - The Basque Country

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2024 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction

- Travels in Spain

- Part I: Paris to Bordeaux

- Part II: Bayonne – Human Contraband

- Part III: The Zagal and the Escepeteros – Irun – The Little Mendicants – Astigarraga

Translator’s Introduction

Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) was born in Tarbes, in the Hautes-Pyrénées region of south-west France, his family moving to Paris in 1814. He was a friend, at school, of the poet Gérard de Nerval, who introduced him to Victor Hugo. Gautier contributed to various journals, including La Presse, throughout his life, which offered opportunities for travel in Spain, Algeria, Italy, Russia, and Egypt. He was a devotee of the ballet, writing a number of scenarios including that of Giselle. At the time of the 1848 Revolution, he expressed strong support for the ideals of the second Republic, a support which he maintained for the rest of his life.

A successor to the first wave of Romantic writers, including Chateaubriand and Lamartine, he directed the Revue de Paris from 1851 to 1856, worked as a journalist for La Presse and Le Moniteur universel, and in 1856 became editor of L’Artiste, in which he published numerous editorials asserting his doctrine of ‘Art for art’s sake’. Saint-Beuve secured him critical acclaim; he became chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1862, and in 1868 was granted the sinecure of librarian to Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, a cousin of Napoleon III, having been introduced to her salon.

Gautier remained in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and the aftermath of the 1871 Commune, dying of heart disease at the age of sixty-one in 1872.

Though ostensibly a Romantic poet, Gautier may be seen as a forerunner to, or point of reference for, a number of divergent poetic movements including Symbolism and Modernism.

This enhanced translation of his Travels in Spain has been designed to offer maximum compatibility with current search engines. Among other modifications, the proper names of people and places, and the titles given to works of art, have been fully researched, modernised, and expanded; comments in parentheses have been added here and there to provide a reference, or clarify meaning; and minor typographic or factual errors, for example incorrect attributions and dates, in the original text, have been eliminated from this new translation.

Part I: Paris to Bordeaux

Some weeks ago (April, 1840), I let fall this sentence, quite casually: ‘I would gladly visit Spain!’ Five or six days later, my friends having deleted the prudent conditional tense with which I had qualified my desire, repeated, to anyone who would listen, that I definitely intended to take a trip to Spain. To this positive formula succeeded the question: ‘When are you leaving?’ I replied, without comprehending what I was committing to: ‘In eight-days’ time.’ The eight days having elapsed, people expressed astonishment on seeing me still in Paris. ‘I thought you were in Madrid.’ said one. ‘Are you back already?’ asked another. I now understood that I owed my friends an absence of several months at least, and that I had to pay the debt as swiftly as possible, or be harassed without respite by my officious creditors. Theatre foyers, and the varied asphalts and elastic bitumens of the boulevards, were forbidden me until further notice: all I could obtain was a delay of three or four days, and, on the fifth of May, I began the process of ridding the country of my unwelcome presence by climbing into a coach bound for Bordeaux.

I will pass lightly over the first post-stations, which offered us nothing out of the ordinary. To right and left lay all kinds of crops, in stripes like those of tigers or zebras, looking exactly like those tailors’ cards where samples of cloth for trousers and waistcoats are displayed. Such perspectives delight agronomists, landowners, and bourgeois others, but offer meagre fodder for the enthusiastic traveller and student, who, telescope in hand, sets out to observe the universe. Since I had left in the evening, my first memories, of Versailles are only faint sketches blurred by the night. I regret having passed through Chartres without an opportunity of viewing the cathedral.

Between Vendôme and Château-Regnault, pronounced Chtrno in the language of the postilions (so well portrayed by Henri Monnier, in his illustration of a passing diligence), rise wooded hills whose inhabitants carve homes from the living rock and live underground, in the manner of the ancient Troglodytes. They sell the stone removed from their excavations, so that each hollowed-out house yields a corresponding one in relief like a work in plaster removed from the mould, or a tower built from the stones of a well; their chimneys, long pipes hammered out from the thickness of rock, end flush with the ground, so that the smoke leaves the earth in bluish spirals and without visible source, as from a sulphur-pit or volcanic terrain. It’s all too easy for the facetious passer-by to throw a stone that lands in the breakfasts of these hidden folk, while absent-minded or short-sighted rabbits must frequently fall into the pot alive. The construction of these dwellings obviates the need to descend to one’s cellar to select one’s wine.

Château-Regnault is a small town with steep, twisting slopes, lined with poorly-sited, tottering houses, which seem to support each other in their upright stance; a large round tower, above a few embankments of ancient fortifications draped here and there with green sheets of ivy, slightly enhances its appearance. From Château-Regnault to Tours there is nothing remarkable about the country, wooded on every side, or the long yellow stripes that extend as far as the eye can see, which they term ribbons, much like those round the plaited queues that carters wear: that’s all, in sum; then the road plunges, suddenly, between two fairly steep slopes, and, a few minutes later, we discover the city of Tours, which its prunes, Rabelais, and Monsieur de Balzac, have rendered famous.

The Tours bridge is much praised, though in itself nothing extraordinary; yet the town is charming in appearance. When I arrived, the sky, through which a few puffs of cloud trailed nonchalantly, possessed a bluish tint, of extreme mildness. A white line, like that traced on glass by the edge of a diamond, cut the limpid surface of the Loire. This adornment was formed by a small weir, produced by one of the sandbanks so common in the bed of that river. Saint-Gatien showed as a brown silhouette in the clear air, its Gothic spires surmounted by domes and bulges like the Kremin belltowers, giving the city’s outline a wholly picturesque Muscovite appearance. A few other spires and towers belonging to churches whose names I do not know, completed the picture. Boats with white sails glided, with the motion of slumbering swans, over the river’s azure mirror. I would like to have visited the house of Tristan l’Hermite, Louis XI’s formidable accomplice, which remains in a marvellous state of preservation, with its notable and dreadful ornamentation composed of twists of rope and other intertwined instruments of torture, but lacked the time; I had to rest content with following the Grande-Rue, which must be the pride of the Tourangeaux, as the inhabitants of the city are named, with its pretentions of rivalling the Rue de Rivoli.

Châtellerault, which enjoys a wide reputation for its cutlery, possesses nothing of note, except for a bridge with ancient towers at each end, creating the most charmingly feudal and romantic effect in the world. As for the arms-factory, it is a large white mass with a multitude of windows. Of Poitiers I can say nothing, having traversed it in driving rain, and in darkness blacker than an oven, except that its cobbles are perfectly execrable.

As daylight returned, the carriage was travelling through wooded countryside, apple-green trees planted in soil of the brightest red producing a most singular effect. The farm-roofs were covered with hollow tiles, grooved in the Italian manner. These were also bright red, an alien colour to eyes accustomed to the dark and sooty tones of Parisian roofs. Due to an odd custom, whose motive escapes me, the region’s builders begin by constructing the roof; the walls and foundations follow. The frame is erected on four stout planks and the roofers complete their work before the masons start.

Angoulême, a town perched, oddly, on a very steep hillside, at the foot of which the Charente causes two or three mills to emit their babble, is built according to the same fashion. It has a kind of Italianate air, enhanced by the clumps of trees that crown its escarpments, and a species of large pine-tree, expanding much like a parasol, akin to those in Roman villas. An old tower which, if my memory serves me correctly, is surmounted by a telegraph station (the telegraph has saved many an old tower) adds to the severity of its general appearance, and allows the town to hold its own as regards the horizon. Ascending the slope, I noticed a house daubed externally with a crude fresco depicting Neptune perhaps, or Bacchus, or Napoleon. The artist having neglected to add the name, all suppositions are allowed and may be defended.

Up to this point, I admit that an excursion to the east of Paris, to Romainville or Pantin, would have seemed just as picturesque. There is nothing flatter, emptier, more insipid than the interminable strips of land, like those strips by means of which lithographers portray the Paris boulevards on a single sheet of paper. Hawthorn hedges and stunted elms; stunted elms and hawthorn hedges, with further off a row of poplars, their green plumes stuck in level ground, or a willow with a deformed trunk and powdery wig, there you have the whole landscape; for human presence, an engineer, or a roadworker, tanned like an African Moor, who watches you pass by, hand resting on the handle of his hammer, or a poor soldier returning to his regiment, sweating and staggering beneath his equipment. But beyond Angoulême, the physiognomy of the landscape changes, and one begins to comprehend one’s distance from suburbia.

On leaving the department of the Charente, one encounters the first areas of moorland. These are vast stretches of grey purplish-blue land, with more or less pronounced undulations. A rare moss, of no great height, heathers reddish in tone, and stunted patches of broom, form its whole vegetation. It has the melancholy air of the Egyptian Thebaid, and at every moment one expects to see a file of camels or dromedaries; it seems as if no human being has ever been there before.

Having crossed the moors, one enters a quite picturesque region. Groups of houses, beside the road, are buried like nests among clumps of trees resembling those in Hobbema’s paintings, with wide roofs, wells clothed in wild vines, large oxen with astonished eyes, and hens pecking among the manure-heaps. All these houses, note, are fashioned of cut stone, as are the garden walls. On every side one sees the outlines of buildings, abandoned on pure whim, and started up again a few steps away. The natives are akin to children who have been given building blocks to play with, and who can, by employing a selection of wooden pieces cut into rectangles, make all manner of constructs; they remove their roofs, carry about the stones of their house, and create a completely different one from the same materials. Gardens flourish beside the road, dotted about with sweet-peas, marguerites, and roses, and surrounded by beautiful trees of the most humid freshness, and the views plunge down to meadows containing cows up their knees in grass. A side-road perfumed by hawthorn trees and wild roses; a group of trees beneath which stands an unhitched cart; peasant women with their flared headdresses like an alim’s turban, and tight red skirts; a thousand unexpected details delight the eye and add variety to the route. By passing a bitumen glaze over the scarlet-tinted roofs one might think oneself in Normandy. Camille Flers and Louis Cabat would find ready-made subjects there. At this latitude berets begin to show themselves; all are blue, and their elegant shape is far superior to that of mere hats.

It is in this region also that one encounters the first ox-drawn carts. These vehicles have a quite primitive, Homeric appearance. The oxen are harnessed to a single yoke, adorned with a small sheepskin headband; they possess a mild, grave, and resigned air, formed like sculptures worthy of some Aegean bas-relief. Most wear a white canvas caparison which protects them from horseflies and the like. Nothing is more singular than the sight of these oxen, in their long shirts, slowly raising their wet shiny muzzles to gaze at you from large dark-blue eyes, which the Greeks, those connoisseurs of beauty, found so remarkable, that they made them an epithet of Juno: βοῶπις Ἥρη, Ox-eyed Hera.

A wedding, taking place in an inn, furnished the opportunity to see a gathering of people native to the region; since, in a space of more than a hundred leagues, I had not seen ten of them. The natives are very ugly, especially the women; there is no difference between the young and the old; a peasant woman of twenty-five or one of sixty are equally withered and wrinkled. The little girls have caps as imposing as those of their grandmothers, which gives them the air of those Turkish street-children, with enormous turbaned heads and slender bodies, in Alexandre Decamps’ sketches. In the stable of this inn I saw a monstrous black goat, with immense spiral horns and flaming yellow eyes, which had a hyper-diabolical appearance, and might have presided worthily over the Sabbath in the Middle Ages.

Daylight was fading when we arrived at Cubzac. In the past, one crossed the Dordogne by ferry; the width and speed of this river made the crossing dangerous, now the ferry has been replaced by a suspension bridge of the boldest design: it is known that I am no great admirer of modern inventions, but it is really a work worthy of Egypt or Rome as regards its colossal dimensions and grandiose appearance. Piers formed by a series of arches gradually rising in height, support the suspended roadway. Ships under full sail can pass beneath as if between the legs of the Colossus of Rhodes. Towers of fenestrated cast-iron, to render them lighter, serve as trestles for the iron wires which cross with a carefully-calculated symmetry under tension; these cables, outlined against the sky, seem to possess the tenuousness and delicacy of a spider’s web, which further adds to the marvellousness of the construction. Two cast-iron obelisks are placed at each end as on the peristyle of a Theban monument, and the ornamentation would not have been out of place there, since the architectural genius of the Pharaohs for the gigantesque would not have disavowed the Cubzac bridge. It takes thirteen minutes, watch in hand, to traverse it.

An hour or two later, the lights of the Bordeaux Bridge, another marvel, though of a less striking aspect, glittered, at a distance away that my appetite wished much shorter, since the rapidity of a journey is always obtained at the expense of the traveller’s stomach. Having exhausted the bars of chocolate, biscuits and other supplies in the carriage, we began to think of cannibalism. My companions looked at me with eyes full of the fear of starvation, and, if there had been yet another leg of the journey to do, we would have repeated the horrors of the raft of the Medusa, and eaten our straps, the soles of our boots, the crowns of our hats and the other items shipwrecked people are accustomed to, and which they digest perfectly well.

Bordeaux

On descending from the vehicle, one is assailed by a crowd of porters who share out your belongings it requiring twenty or so to carry a pair of boots: this is commonplace; but what is more amusing is that these are a species of agent posted by the hotel proprietors to snatch up the traveller as one passes by. The whole of this rabble shout aloud a chorus of praises and insults in gibberish: one grabs you by the arm, another by the leg, this one by the tail of your coat, that by the button of your vest: ‘Monsieur, try the Hotel de Nantes, an excellent place!’ ‘No Monsieur, stay away from there, it’s the bedbugs’ hotel, that’s its real name,’ the representative of a rival inn hastens to add. ‘Hotel de Rouen! Hotel de France!’ cry the little band following you, vociferously. ‘Monsieur, they never clean the pots; they cook with lard; the rain wets all the rooms; you’ll be flayed, robbed, murdered.’ They all seek to deter you from visiting rival establishments, and this procession only quits the chase when you have finally entered one of them. Then they quarrel among themselves, hurling deprecations and decrying each other as bandits, thieves, along with other most plausible insults, before they set out, in sudden haste, in pursuit of other prey.

Bordeaux greatly resembles Versailles in terms of the style of its buildings: it is evident that its architects were preoccupied with the idea of surpassing Paris in grandeur; the streets are wider, the houses vaster, their stories higher. The theatre is of enormous dimensions; it’s the Odéon merged with our Stock Exchange, the Bourse. But the inhabitants find it difficult to populate their city; they do all they can to appear numerous, but all their southern turbulence is not enough to furnish those disproportionate buildings; the high windows rarely display curtains, and the grass grows in a melancholy fashion in the immense courtyards. It is the grisettes, and the women of the people, who animate the city; they are really very pretty: almost all of them possess straight noses, cheeks lacking pronounced cheekbones, and large black eyes in pale oval faces, creating a charming effect. The customary headdress is most original; it is made up of a bright coloured kerchief, like a madras, worn in the creole style, set far back, and containing the hair which sits quite low on the nape of the neck; the rest of the outfit consists of a large straight shawl that descends to the heels, and a dress of Indian cotton with long pleats. These women have an alert and lively gait, the waist supple and arched, and slender in nature. They carry, on their heads, baskets, packages, and jugs of water which, incidentally, are of a very elegant shape. With their amphorae on their heads, and dressed in their pleated costumes, one might take them for Greek girls, each a Princess Nausicaa on her way to the fountain.

The cathedral, built by the English, is quite beautiful; the portal contains life-size statues of bishops, of a much truer and more studied execution than ordinary Gothic statues, which are posed en arabesque and sacrificed wholly to the requirements of architecture. While visiting the church, I saw, set against the wall, Léon Riesener’s magnificent copy of The Scourging of Christ, after Titian; it was awaiting a frame. From the cathedral, my companion and I went to the Saint-Michel tower, where there is a vault which possesses the property of mummifying the bodies placed there.

The top floor of the tower is occupied by the caretaker and his family who cook at the entrance to the vault and live there in the most intimate familiarity with their dread neighbours; the man took a lantern, and we descended by a spiral staircase, with worn steps, to the funereal hall. The dead, approximately forty in number, are arranged upright around the vault, leaning against the wall; this perpendicular attitude, which contrasts with the usual horizontality of corpses, gives them an appearance of phantasmic life which is most fearsome, especially in the yellow, flickering light of the lantern which oscillates in the guide’s hand and alters the position of the shadows, from moment to moment.

The imaginings of poets or painters have never produced a more horrible nightmare; the most monstrous whims of Goya, the deliriums of Louis Boulanger, the devilries of Jacques Callot and Teniers are nothing by comparison, and all the makers of fantastic ballads are rendered obsolete. More abominable spectres have never emerged from the German night; they are worthy of appearing at the sabbath on the Brocken, with the witches, in Faust.

Here are contorted, grimacing faces, half-peeled skulls, half-opened flanks, which reveal, through the mesh of ribs, lungs dry and withered as sponges. On this side, the flesh has been reduced to powder and the bones break through; on the other, no longer supported by fibres of cellular tissue, the parchment-like skin hangs about the skeleton like a second shroud; none of these heads have the impassive calm that death imprints like a supreme seal on all those it touches; mouths yawn horribly as if strained by the immeasurable boredom of eternity, or sneer with that sardonic empty laughter which mocks life; the jaws are dislocated, the neck muscles swollen; fists clench furiously; the backbones arch in desperate tension. They seem as if irritated at having been dragged from their graves, and having been disturbed in their sleep by profane curiosity.

The caretaker showed us a general, slain in a duel – the wound in his side, like a wide mouth with blue smiling lips, is perfectly distinguishable – then a porter who expired, suddenly, while lifting an enormous weight; a dark-skinned woman only a little blacker than the pale-skinned ones placed near her; a woman who still had all her teeth and an almost intact tongue; and, finally, a family who died from eating poisonous mushrooms; and, supreme horror, a little boy who, to all appearances, must have been buried alive.

This last figure is sublime in its pain and despair; never has the expression of human suffering been carried further: the nails dig into the palms of the hands; the nerves are stretched taut like the strings on the bridge of a violin; the knees make convulsive angles; the head is thrown back, violently; the poor child, with an incredible effort, has turned around in his coffin.

The room where these dead are located is a cellar with a low vault; the soil, suspiciously soft, is composed of human detritus fifteen feet deep. In the middle rises a pyramid of more or less well-preserved debris; the mummies exhale a bland and dusty odour, more unpleasant than the pungent perfumes of bitumen and Egyptian natrum; some of them have been there for two or three hundred years, others for only sixty; the fabric of their shirts or shrouds is also fairly intact.

Leaving the vault, we departed to view the belfry, consisting of two towers joined at their summit by a balustrade of original and picturesque taste, and then the church of Sainte-Croix, next to the old people’s hospice, a building with full arches, and twisted columns, with foliage carved wholly in the Greek-meander manner, in Byzantine style. The portal is enriched with a multitude of groups that quite brazenly carry out the precept Crescite et multiplicamini: grow and multiply. Fortunately, the efflorescent, tufted arabesques conceal what might seem strange in regard to this manner of rendering the spirit of the divine text.

The museum, located in the town-hall’s magnificent mansion, contains a fine collection of plasterwork and a large number of notable paintings, including two small pictures by Cornelius Bega which are twin priceless pearls, combining the warmth and freedom of Adriaen Brouwer with the finesse and refinement of Teniers; there are also works by Adriaen van Ostade of great delicacy, by Tiepolo revealing the most baroque and fantastic of tastes, by Jacob Jordaens and Van Dyck, and also a Gothic painting which must be by Fra Angelico or Ghirlandaio: the Paris museums have nothing in terms of medieval art to match it; only it is impossible to hang pictures with less taste and discernment; the prime locations are occupied by enormous crustaceans of the modern school from the era of Pierre-Narcisse Guérin and Guillaume Léthiers.

The port is crowded with vessels of all nations and varied tonnage; in the evening mist, they seem a host of cathedrals adrift on the water, since nothing resembles a church more than a ship with its slender masts and criss-crossed strands of rope. To end the day, we entered the Grand-Théâtre. Conscience compels me to say that it was full, despite the opera being Françoise Boïeldieu’s La Dame Blanche, which is far from being a novelty these days; the auditorium is about the same size as that of the Paris Opéra, but much less ornate. The performers’ singing was as out of tune as it is at our original Opéra-Comique.

In Bordeaux, the Spanish influence can already be felt. Almost all the signs are in two languages; the booksellers stocking at least as many Spanish books as French. Many people know how to hablar in the idiom of Don Quixote and Guzmán de Alfarache: this foreign influence increases as one approaches the border; and, to tell the truth, the Spanish tongue, in this half-way house, prevails over the French: the patois that the people of the region speak has much more to do with Spanish than with the language of their fatherland.

Part II: Bayonne – Human Contraband

Leaving Bordeaux, moorland reappears; sadder, gaunter, and drearier, if possible, than ever; decked out with heather, broom and pinadas (pine-groves), with, here or there in the wilds, some shepherd crouching, guarding his flock of black sheep, or a hut like an Indian wigwam: it provides a most dismal spectacle and very little entertainment. No other tree is visible but the pine with its notch from which resin flows. This large wound, whose salmon-colour contrasts with the grey tones of the bark, gives a most lamentable appearance to a tree suffering the deprivation of the majority of its sap. The groves look like woods unjustly slain, the trees raising their arms to the sky in a plea for justice.

We passed through Dax in the middle of the night, and crossed the Adour in dreadful weather, with pouring rain and a wind strong enough to de-horn oxen. The further we advanced towards hotter regions, the more bitter and sharp the cold became. If we had not had our overcoats with us, our noses and feet would have frozen like those of the soldiers of the Grande Armée in the Russian campaign.

When daylight broke, we were still amidst the moorland; but the pines were interspersed with cork-oaks, trees that I had always imagined in the form of corks themselves, but which are, in fact, enormous in height, at the same time both oak and carob in the strangeness of their attitude and the deformity and roughness of their branches. Pools of brackish water, and of a leaden colour, extended on both sides of the road; salt-laden air reached us in gusts; A vague murmur I failed to recognise, sounded on the horizon. At last, a bluish silhouette appeared on the pale backcloth of the sky: it was the Pyrenees mountain-range. A few moments later, an almost invisible line of azure, marking the Ocean, announced to us that we had arrived. Bayonne soon became visible in the form of a pile of crushed tiles and an awkward, squat bell tower; I say nothing ill of Bayonne, for the view of a city in the rain is, of its nature, dreadful. The port was not very full; a few scarce pontoon-boats lounged beside the deserted quays, with an air of nonchalance, in admirable indolence; the trees which form the promenade are very beautiful and temper somewhat the austerity of all those straight lines displayed by the fortifications and parapets. As for the church, it is painted in straw-colours and light beige; the only thing remarkable about it being a kind of baldachin in red damask, and a few paintings by Nicolas Lépicié and others, in the style of Charles-André van Loo.

Bayonne is virtually a Spanish city as regards language and customs: the hotel where we stayed was called the Fonda San-Esteban. On it being learned that we were about to make a long trip throughout the Peninsula, we were given all kinds of recommendations: ‘Buy red belts to gird your waists; equip yourself with muskets, combs, and vials of insect-repellent water; take biscuits and other provisions; the Spaniard’s breakfast is a spoonful of chocolate, dinner a clove of garlic washed down with a glass of water, and supper a hand-rolled cigarette. You should also take a mattress each, and a cooking pot to make soup.’ The French- to-Spanish guidebook for travellers was not very reassuring. In the chapter on the traveller at the inn, we read these fearsome words: ‘I would like to partake of something.’ – ‘Have a seat,’ the hotelier replies – ‘Very well; but I’d rather eat something thing more nourishing’ – ‘What have you brought with you?’ continues the owner of the posada – ‘Nothing’, replies the traveller sadly – ‘Well! How can I cook a meal for you: the butcher is over there, the baker beyond. Go, buy some bread and meat, and, if there’s coal for the fire, my wife, who can cook a little, will supply you with dinner.’ The traveller, furious, creates a dreadful row, while the impassive hotelier writes on the bill: six reals for rowdiness.

The coach for Madrid leaves from Bayonne. The coachman is called a mayoral and wears a pointed hat adorned with velvet and silk tassels, a brown jacket embroidered with coloured embellishments, leather gaiters, and a red belt: behold the small initial token of local colour. Beyond Bayonne, the country is extremely picturesque; the Pyrenees range is more clearly seen, and its mountains, with beautiful undulating lines, make the horizon appear more varied; the sea is frequently visible to the right of the road; at each bend one catches sight, suddenly, between two mountains, of those sombre, yet soft-blue depths, cut here and there by curls of foam, whiter than snow, of which no painter has ever been able to convey the true idea. Here I make honourable amends to the sea, of which I have previously spoken irreverently, having only viewed the waters off Ostend, which are little more than the Scheldt estuary, as my dear friend Fritz (Gérard de Nerval) once maintained, so spiritedly.

The dial of the church at Urrugne, which we passed through, had this funereal inscription written in black letters: Vulnerant omnes, ultima necut: all things wound, the last kills. Yes, you are right, melancholy dial, every hour tracked by your sharp-pointed hands hurts us, and every turn of the wheel bears us towards the unknown.

The houses in Urrugne, and Saint-Jean-de-Luz which is not far distant, have a bloodthirsty and barbaric physiognomy, due to the strange custom of painting the doors, the shutters, and the beams that hold the masonry sections etc. in antique red or oxblood. After Saint-Jean-de-Luz, one comes to Behobie, the last French village. There are two items of trade on the border, to both of which war has given rise: first that of cannon-balls found in the fields, then that of human beings. A Carlist is transported like a bale of merchandise; there is a variable rate: so much for a colonel, so much for an officer; the deal done, the trafficker arrives, takes his man, bears him onwards, and renders him to his destination as he might a dozen scarves or a hundred cigars. On the far side of the Bidasoa river one reaches Irun, the first Spanish village; half of the bridge belongs to France, the other to Spain. Close to this bridge is the famous Pheasant Isle where the marriage of Louis XIV was celebrated by proxy. It would be difficult to celebrate anything there today, because it is no bigger than a medium-sized fried sole.

A few more turns of the coach’s wheels and perhaps one of my fondest illusions will vanish; I will see the Spain of my dreams disappear, the Spain of the romancero, the ballads of Victor Hugo, of Mérimée’s short stories, and Alfred de Musset’s tales. Crossing that dividing line, I remembered what the good and witty Heinrich Heine had said to me, at the Liszt concert, his German accent full of humour and mischief: ‘What will you do, as regards all this talk of Spain, once you’ve been there?

Part III: The Zagal and the Escepeteros – Irun – The Little Mendicants – Astigarraga

Half of the Bidasoa bridge belonging to France, and the other half to Spain, you can have one foot in each kingdom, which is very grand: here, the gendarme grave, honest, serious, the gendarme fulfilled, having been rehabilitated, according to Léon Curmer’s Les Français, by Édouard Ourliac; there, the Spanish soldier, clad in green, savouring the sweetness and softness of a rest in the green grass, with blissful nonchalance. At the far end of the bridge, you enter immediately into Spanish life, full of local colour: Irun in no way resembles a French market town; the roofs of the houses jut out like a fan; the run of tiles, alternately round and hollow, forms a kind of crenellation, with an alien Moorish appearance. The protruding balconies are of ancient ironwork, crafted with a care surprising in so remote a village as Irun, and indicating a great but vanished opulence. The women pass their lives on these balconies shaded by an awning with coloured bands, balconies which are like so many aerial chambers added to the body of the building; both sides are left open and give passage to cool breezes and ardent glances; as for the rest, look not for the tawny and brazen hues (forgive the term), those brown shades, of a well-smoked pipe, that a painter might hope for: everything is whitewashed according to the Arab custom; but the contrast of this chalky tone with the dark brown colour of the beams, roofs and balconies, succeeds in producing a fine effect.

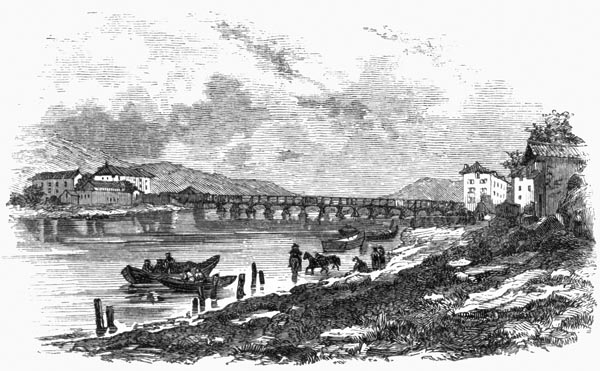

Bridge of Irun

At Irun, the horses left us. Ten mules were harnessed to the coach, each shaved to the middle of its body, half hide, half hair, like those medieval costumes which seem in two sections made of different cloth and sewn together by chance; the creatures, thus shaved, have a strange appearance and seem frighteningly lean; since the denudation allows us to study their anatomy in depth: bones, muscles and even the smallest veins. With their furry tails and pointed ears, they look like enormous mice. In addition to the ten mules, our staff was augmented by a zagal and two escopeteros adorned with their trabucos (muskets). The zagal is a kind of coachman, a sub-mayoral who applies the brakes on perilous descents, keeps an eye on the harnesses and the coach-springs, drums up relay-animals, and plays the role of a coachman, but more efficiently. The zagal’s costume is charming, extremely elegant and light; he wears a pointed hat embellished with bands of velvet, and silk pompoms, a brown or tobacco-coloured jacket, with undersleeves and a collar made of pieces of cloth of various colours, usually blue, white, and red, and with a large flowery arabesque in the middle of its back, breeches studded with filigree buttons, and for shoes alpargolas, sandals attached by cords; add to this a red belt and a colourful cravat, and you have the most characteristic look. The escopeteros are guards, miqueletes (militia men) appointed to escort the car and frighten the rateros (that’s what we call the petty thieves, there), who cannot resist the temptation of robbing isolated travellers, but whom the edifying sight of a musket is enough to deter, out of respect, and who in passing greet you with the sacramental: ‘Vaya usted con Dios’; go with God’. The clothing of the escopeteros is roughly similar to that of the zagal, but less coquettish, less embellished. They are positioned on a double seat at the rear of the coach, and thus dominate the countryside. In the description of our caravan, I forgot to mention a small postilion mounted on a horse, who heads the convoy and gives impetus to the whole array.

Before leaving, it was necessary to have our passports, already quite adorned, stamped. During this important operation, we had time to take a look at the population of Irun which displays nothing particular, except that the women wear their hair, which is remarkably long, gathered in a single braid which hangs down to their haunches; shoes are rare there, and stockings even more so.

A strange, inexplicable, hoarse, fearful, and risible noise had been annoying my ears for some time; think of a multitude of jays being plucked alive, children being whipped, cats in love, saws grinding their teeth away on hard stone, cauldrons being scraped, or prison-cell hinges grinding rust, forced to release their captive; I, for my part, believed that it was a princess whose throat was being slit by some fierce black-skinned native; it was, in fact, nothing but an oxcart travelling along the Rue d’Irun, whose wheels were caterwauling dreadfully for lack of being greased, the driver no doubt preferring to add the grease to his soup. The cart was certainly very primitive; the wheels being solid and turning with the axle, like those, of their little carts, that children make of pumpkin peel. The noise can be heard half-a-league away, and seems not to displease the natives of that country. They thereby possess a musical instrument which costs them nothing and which plays itself, by itself, as long as the journey lasts. It seems to appear as harmonious to them as a violinist’s exercises on the fourth string do to us. No peasant would wish for a cart that failed to sing: this type of vehicle must date from the Flood.

On the façade of an old palace transformed to an ordinary house, we saw for the first time an example of that white plaster panel which shames many another old palace with its inscription: Plaza de la Constitucion. The true state of things will always emerge in some way: one could not choose a better symbol to represent the current state of that country. A constitution in Spain is like a handful of plaster on a granite surface.

As the climb is steep, I walked as far as the city gate, and, turning around, cast a farewell glance at France; it was a truly magnificent spectacle: the chain of the Pyrenees descended in harmonious undulations towards the blue sheet of the sea, crossed here and there by a few silver bars, and, thanks to the extreme clarity of the air, far, far away, one could see a faint, pale salmon-coloured line, which jutted out into the immeasurable azure and formed a vast indentation in the coastline. Bayonne, and its advanced sentinel, Biarritz, occupied the far end of this indentation, and the Bay of Biscay was outlined as clearly as on a map; from here we would lose sight of the sea until we were in Andalusia. Farewell, brave Ocean!

The mules galloped up and down the slopes at extreme speed; a balancing exercise on the steep track, which can only be performed thanks to the prodigious skill of the drivers, and the extraordinary surety of the creatures’ feet. Despite our speed, from time to time a laurel branch, a small bouquet of wild flowers, a necklace of mountain strawberries, pink pearls threaded by a blade of grass, fell into our laps. These bouquets were thrown by little mendicants, girls and boys, who followed the coach, running barefoot over the sharp stones: this way of asking for alms by sacrificing yourself has about it something noble and poetic.

The landscape was charming, somewhat Swiss perhaps in appearance, and offering a wide variety of views. Mountain ridges, the gaps in which revealed higher ranges, rose on both sides of the road; their flanks cultivated in different ways, or wooded with holm-oaks, formed a vigorous foil for the distant, misted peaks; villages with red-tiled roofs blossomed at the foot of the mountains amidst clumps of trees, and I expected at any moment to see Kettly or Rutley, those characters from Paul Duport’s comic-opera, emerge from the alien chalets. Fortunately, Spain does not take things that far.

Torrents as capricious as women, form waterfalls, here and there; divide, and converge again, amidst rocks and over pebbles, in the most diverting way; and serve as a pretext for a multitude of the most picturesque bridges in the world. These bridges, infinitely multiplied, have a singular character; the arches rise almost to the parapets, so that the road over which the carriage passes seems no more than six inches deep; a sort of triangular pile of stone forming a bastion usually occupies their centre. It is not a very arduous occupation, that of a Spanish bridge; there is no sinecure more perfect: one can walk beneath it three-quarters of the year. The bridges rest there, with an air of imperturbable phlegmatism, and a patience worthy of a finer fate, awaiting a river, a trickle of water, a little humidity even; feeling no doubt that their arches are mere arcades, and that their title of ‘bridge’ is purely a product of flattery. The torrents I spoke of earlier are at most four to five inches deep; but they serve to create a lot of noise, and enliven the solitary spaces they traverse. From time to time, they drive some mill, or manufactory, by means of channels and locks, built as the landscapers require; the houses, scattered about the countryside in small groups, are of a curious colour; they are neither black, nor white, nor yellow, but the colour of roast turkeys: the comparison, though trifling and culinary, is nonetheless strikingly valid. Patches of holm-oaks, and clumps of other trees, happily, enhance the broad outlines and severe misted hues of the mountains. I insist on mentioning these trees, because nothing in Spain is rarer, and from now on I shall have scant opportunity for describing them.

We changed mules at Oiartzun, and arrived, at nightfall, at the village of Astigarraga, where we were to sleep. We had not yet tried a Spanish inn; the picaresque and teeming descriptions of Don Quixote, and of Lazarillo de Tormes, came to mind, and it made the body itch just thinking about them. We anticipated omelettes adorned with Merovingian hair, with feathers and feet involved, quarters of rancid bacon complete with the bristles, equally suitable for making soup or brushing one’s shoes, wine in goatskins, like those the good knight of La Mancha slashed at so furiously, or even nothing at all, which is far worse, and trembled at having naught to eat but the evening breeze, and to sup, like the valiant Don Sancho, on an air on the mandolin.

Profiting from the little daylight that remained, we visited the church which, to tell the truth, looked more like a fortress than a temple: the narrowness of the windows, cut like loopholes, the thickness of the walls, the solidity of the buttresses gave it a squared, robust attitude, more warlike than pensive. This is often the form of churches in Spain. All about it lay a kind of open cloister, in which was suspended a very large bell, rung by agitating the clapper with a rope, instead of swinging the enormous metal shell itself.

On being conducted to our rooms, we were dazzled by the whiteness of the bed curtains and window drapes, the Dutch cleanliness of the floors, and the perfect attention to every detail. Lovely, tall, shapely girls with magnificent braids falling over their shoulders, perfectly-dressed, and nothing like the maritornes Cervantes promised, went to and fro with that degree of activity that augured well for the supper which was not long in coming, excellent, and very well served. At the risk of appearing pedantic, I will describe it; since the difference between nations consists precisely of the thousand little details that travellers neglect in favour of those vast poetical and political reflections that one can write equally as well without visiting the country concerned.

For the first course, we were served with a thick soup, differing from ours in that it possessed a golden-yellow tint, owing to the saffron with which it is sprinkled to give it flavour. Behold, local colour indeed: golden-yellow soup! The bread was very white, very dense, with a smooth, slightly golden crust; and noticeably salty to a Parisian palate. The forks had their tails curved backwards, and their flat heads cut into comb-like teeth; the spoons also had a spatula-like appearance that our silverware does not have. The linen was a type of coarse weave damask. As for the wine, we must admit that it was the colour of the finest bishop’s-cassock-purple that could be seen, sufficiently full-bodied to be cut with a knife, and rendering the carafes in which it was contained completely opaque.

After the soup, they brought puchero, an eminently Spanish dish, or rather the only Spanish dish, because we ate it every day from Irun to Cadiz, and vice-versa. The composition of a decent puchero stew involves a hind-quarter of beef, a leg of mutton, a chicken, a few pieces of a sausage called chorizo stuffed with pepper, chili, and other spices, slices of bacon and ham, and on top of that a fiery tomato and saffron sauce; that is the animal content. The vegetable content, verdura, varies according to season; but cabbage and garbanzos are always there in the background; the chickpea, garbanzo, is hardly seen in Paris, and I cannot define it better than by saying: ‘It’s a pea which aspires to be a bean, and succeeds only too well.’ All this is served in an array of dishes, but the ingredients are mixed on one’s plate in such a way as to produce a truly complex mayonnaise with an excellent taste. This mixture will seem somewhat rustic to gourmets who read Carême, Brillat-Savarin, Grimod de La Reynière and Monsieur de Cussy; however, it has a charm of its own, and will please eclectics and pantheists. Then came chickens, cooked in oil because butter is a thing unknown to Spain, and fried-fish, trout or hake, roast lamb, asparagus, salad, and, for dessert, small macaroon biscuits, toasted almonds with an exquisite taste, and queso de Burgos, which is goat’s-milk cheese possessing a great reputation that it sometimes deserves. To end with, they brought a drinks-stand with Malaga-wine, sherry and brandy, aguardiente, which resembles French anisette, and a little cup (fuego) filled with embers to light the cigarettes. This meal, with a few minor variations, is everywhere reproduced throughout Spain...

We left Astigarraga in the middle of the night; since there was no moon, there is naturally a gap in my story. We passed through Hernani, a town whose name awakens the most Romantic memories, without seeing a thing, except for heaped-up hovels, and rubble, outlined vaguely in the darkness. We traversed, without stopping, Tolosa, where we noted houses adorned with frescoes and gigantic coats of arms carved in stone: it was market day, and the square was covered with donkeys, mules harnessed in a picturesque manner, and peasants with singularly fierce faces.

By dint of ascending and descending, and crossing torrents on drystone bridges, we finally arrived at Bergara, where we dined, with profound satisfaction, since we had long forgotten the jicara de chocolate, swallowed while half-asleep, at the Astigarraga inn.

The End of Parts I-III of Gautier’s Travels in Spain