Théophile Gautier

Travels in Spain (Voyage en Espagne, 1840)

Parts IV to VI - Burgos and Vallodolid

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2024 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Part IV: Bergara – Vitoria: a National Dance Performance and the French Strongmen – The Pancobo Gorge – Donkeys and Greyhounds – Burgos: A Spanish Fonda – Galley slaves in coats – The Cathedral – El Cid’s Chest

- Part V: The Cloister; Paintings and Sculptures – The House of El Cid; The Rope House; The Santa Maria Gate – The Theatre and the Actors – La Cartuja de Miraflores – General Thiébault and the Bones of El Cid

- Part VI: El Correo Real; The Galleys – Valladolid – San Pablo – A Performance of Hernani – Santa Mária la Real de Nieva – Madrid

Part IV: Bergara – Vitoria: a National Dance Performance and the French Strongmen – The Pancobo Gorge – Donkeys and Greyhounds – Burgos: A Spanish Fonda – Galley slaves in coats – The Cathedral – El Cid’s Chest

At Bergara, which is the place where the treaty between Baldemero Espartero and Rafael Maroto was concluded, I saw a Spanish priest for the first time. His appearance seemed quite grotesque to me, although I have, thank God, no Voltairean ideas about the clergy; but Basil, Beaumarchais’ caricature of such, came to mind, involuntarily. Imagine a black cassock, a coat of the same colour, and, to crown all, an immense, prodigious, phenomenal, hyperbolic, titanic hat, of which no epithet, however bloated and gigantic it may be, can give even the slightest idea. This hat was at least three feet in length; the edges rolled upwards, and forming a sort of horizontal roof in front of and behind the head. It would be difficult to invent a more baroque and more fantastic form: which however did not prevent the worthy priest from possessing a very respectable appearance and walking about with the air of a man who has a perfectly clear conscience in regard to the shape of his headdress; instead of a rabat, he wore a small dog-collar (alzacuello), in blue and white, like Belgian priests.

After Mondragón (Arrasate), which is the last town, or, as the Spanish say, the last pueblo, of the province of Gipuzkoa, we entered the province of Álava, and it was not long before we found ourselves at the foot of the mountain-pass leading to Salinas de Léniz (Leintz Gatzaga). A roller-coaster would seem nothing compared to it, and at first the idea that our carriage was going to cross the mountain seemed as ridiculous as our walking on the ceiling upside-down, like flies. The miracle was accomplished thanks to six oxen harnessed at the head of our ten mules. I have never, in my life, heard such an uproar: the mayoral, the zagal, the escopeteros, the postillion and the herdsmen made their assault on it with a storm of cries, invectives, whiplashes and goads; they drove the wheels on with their hands and shoulders, and supported the box from behind, pulling the mules by the halter, and the oxen by the horns, with incredible ardour and fury. The carriage, at the end of this interminable line of men and beasts, created the most astonishing effect in the world. There were a good fifty paces between the first and last creature in the team. Let me not forget to note, in passing, the bell-tower of Salinas de Léniz, which possesses a rather attractive Saracenic shape.

From the summit of the pass, you can see, if you look behind you, the various levels of the Pyrenees chain in infinite perspective; they look like immense draperies of ribbed velvet thrown down at random and crumpled into bizarre folds at the whim of some Titan. In Arroyabe, which is a little further on, I noticed a magical light effect. A snowy ridge (sierra nevada), which the closely-packed mountains had hidden from us until then, appeared suddenly, standing out against a lapis-lazuli sky, of a blue so dark as to be almost black. Soon, on all sides of the plateau we were crossing, other inquisitive mountains raised their heads, laden with snow and bathed in clouds. The snow was not compact, but divided in narrow veins, like ribs of silver lamé, its whiteness enhanced by the contrasting azure and lilac hues of the escarpments. The cold was bitter and increased in intensity as we progressed. The wind had scarcely been warmed in caressing the pale cheeks of these beautiful chilly virgins, and as it reached us felt as icy as if it had come straight from the Arctic or Antarctic pole. We wrapped ourselves as tightly as possible in our overcoats, since it is beyond shameful to possess a frozen nose in a torrid country; a scorched one is acceptable.

The sun was setting as we entered Vitoria (Vitoria-Gasteiz). After traversing all manner of streets adorned with mediocre architecture in gloomy taste, the carriage halted at the parador viejo, the ‘old hostelry’, where our trunks were carefully inspected. Our daguerreotype-camera apparatus especially worried the brave customs officers; they approached it with infinite caution, like folk who are afraid of being hurled into the air: I think they took it to be a machine for delivering therapeutic electric shocks; we took care not to have them reconsider that salutary idea.

Our belongings having been inspected, our passports stamped, we owned the right to disport ourselves among the city streets. We took advantage of this immediately, and, crossing a rather beautiful square surrounded by arcades, we made directly for the church; shadows already filled the nave and amassed themselves, mysteriously and threateningly, in the darker corners where phantasmal shapes could be vaguely discerned. A few small lamps flickered, casting a sinister yellow light, and glowing mistily like stars through fog. I know not what sepulchral chill gripped my body, and it was not without a slight feeling of fear that I heard a melancholy voice whisper, very close to me, the sacramental formula: ‘Caballero, una limosna por amor de Dios: Monsieur, alms for the love of God’. It was a poor devil of a wounded soldier asking for charity. Here the soldiers beg, an action which is excused by their profound poverty, since they are paid irregularly. In this church at Vitoria, I became acquainted with those fearful sculptures in wood which the Spaniards so strangely abuse by painting them.

After a supper (cena) which made us nostalgic for the one at Astigarraga, the idea came to us to visit the theatre: we had been enticed, in passing, by a grandiose poster announcing an extraordinary performance of French strongmen, to end with a certain baile nacional (national dance) which appeared to consist of cachuchas, boleros, fandangos and other furious dances.

Theatres in Spain generally have no special facade, and are only distinguished from other houses by the two or three smoky oil-lamps hanging about the doors. We paid for two seats in the orchestra stalls, which are termed lunette seats (asientos de luneta), and bravely entered a corridor whose floor was neither planked nor tiled but simply native earth. They care no more for the walls of these corridors than for the walls of their public monuments that bear the inscription: Prohibited, under penalty of fine, the deposition of, etc., etc. Yet, holding our noses tightly, we arrived at our seats only half-asphyxiated. Add to this custom their incessant smoking of cigarettes during the intermissions, and your idea of a Spanish theatre will prove less than balsamic.

The interior of the auditorium is, however, more comfortable than its surroundings promise; the boxes are well-arranged, and although the decor is very simple it is fresh and clean. The asientos de luneta are armchairs arranged in rows and numbered; there is no attendant at the door to take your tickets, but a little lad comes and asks for them before the end of the show; all you receive on initial entry is a voucher.

We hoped to find, there, examples of the Spanish female type, of which we had so far seen but few; yet the women who furnished the boxes and the galleries revealed only the Spanish mantilla and fan: that was already a great deal, but not, however, sufficient. The audience was mostly made up of soldiers, as in all towns where there is a garrison. In the pit, one stands, as in very primitive theatres. In order to resemble the theatre at the Hôtel de Bourgogne, all it really lacked was a row of candles, and an employee to snuff them; but the globular glass of the oil-lamps consisted of segments arranged like melon slices (côtes de melon) joined at the top by a circle of tin, which is hardly an advanced style. The orchestra, composed of a single row of musicians mostly playing brass instruments, blew valiantly into their cornets, sounding a ritornello that was ever the same, reminiscent of a Franconi’s Circus fanfare.

Our Herculean compatriots lifted masses of weights, and twisted many an iron bar, to the great satisfaction of the assembled gathering, and the nimbler of the two climbed a steep length of rope and performed other routines, all too well known, alas, in Paris, but probably new to the population of Vitoria. We fretted with impatience in the stalls, I wiping the eyepiece of my opera-glass with furious activity, so as not to lose any of the impending baile nacional. Finally, the trestles were lowered, and the Turks on duty removed the weights and all the rest of the strongmen’s equipment. Imagine, dear reader, the ardent anticipation of two young, enthusiastic and Romantic Frenchmen who are about to view Spanish dance for the first time... in Spain!

At last, the curtain rose on a set which intended, in vain, to conjure an air of enchantment and magic; the cornets repeated, with more fury than ever, the fanfare already described, and the baile nacional advanced in the form of a male and female dancer, both armed with castanets.

I have seen nothing sadder and more lamentable than these two grand wrecks who failed to inspire each other: the fourpenny theatre never bore on its worm-eaten boards a couple more worn-out, more exhausted, more toothless, more melancholy, balder, or more ruined. The poor woman, who had plastered herself with crude white make-up, possessed a sky-blue hue which brought to mind the anacreontic image of a choleric corpse or a freshly-drowned man; the two red spots with which she had adorned the tops of her bony cheekbones, to brighten a little her eyes like boiled fish, contrasted in a most singular manner with this blue tint; with veiny, fleshless hands she clicked a pair of cracked castanets which chattered away like the teeth of a man with a fever, or the hinges of a moving skeleton. From time to time, with a desperate effort, she stretched the loose sinews of her hocks, and managed to lift her poor old leg carved to the shape of a baluster, so as to produce a little nervous caper, like a dead frog subjected to a Voltaic pile, and to make the copper flakes of the dubious overskirt that served as her basquin sparkle and glitter for a second. As for the man, he moved about in a sinister manner in his corner; he rose and fell limply like a bat crawling on its stumps; his appearance was that of a gravedigger burying himself, his forehead wrinkled like a hussar’s boot; his parrot’s nose, his goat’s cheeks gave him a most fantastic appearance, and if, instead of castanets, he had held a Gothic rebec, he might have posed for the lead in the dance of the dead, in the Basel fresco.

Throughout the dance, they did not once raise their eyes to each other; one would have said that they were afraid of their mutual ugliness, and feared bursting into tears at seeing each other so old, so decrepit and so funereal. The man, indeed, fled his companion as from a spider, and seemed to shiver with horror in his old parchment skin, every time a figure of the dance forced him to approach her. This macabre bolero lasted five or six minutes, after which the fall of the curtain put an end to the torment of these two unfortunate people... and to ours.

This is how the bolero appeared to two poor travellers taken with local colour. Spanish dance exists only in Paris, as sea-shells do, which are found at the curio-sellers, and never at the seaside. O Fanny Elssler, who are now in America among the savages, even before our journey to Spain we suspected that it was you who had invented the cachucha!

We retired to bed quite disappointed. In the middle of the night, someone came to wake us so as to set us on our way; it was still freezing cold, a Siberian chill, which is to be explained by the height of the plateau we were crossing, and the snow with which we were surrounded. At Miranda de Ebro, we met with our trunks once again, and entered Old Castile (Castilla la Vieja), in the kingdom of Castile and Leon, symbolized by a lion holding a shield strewn with castles. These lions, repeated endlessly, are usually made of greyish granite and have a somewhat imposing heraldic presence.

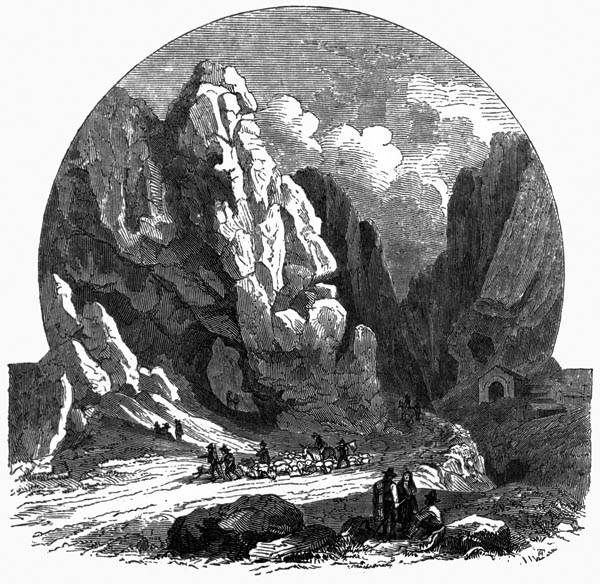

Between Ameyugo and Cubo de Bureba, small insignificant villages where relay animals are provided, the landscape is extremely picturesque; the mountains draw closer, the road is narrower, and immense perpendicular rocks rise at the edge of the track, as steep as cliffs; on the left, a torrent, crossed by a bridge with a truncated arch, boils at the bottom of a ravine, turns a mill, and covers with foam the stones which hinder it. In order that nothing detracts from the effect, a Gothic church, falling to ruin, the roof shattered, the walls embroidered with parasitic plants, rises amidst the rocks; in the background, the Sierra appears vague and bluish. The view is undoubtedly beautiful, but the Pancorbo Pass exceeds it in singularity and grandeur. The rocks there leave only sufficient space for the track, and one arrives at a place where two great granite masses, leaning towards each other, simulate the arch of a gigantic bridge that has been broken at the centre, so as to close the way to some army of Titans; a second, smaller arch, carved in the thickness of rock, further adds to the illusion. Never has a theatre designer imagined a more picturesque or more easily-comprehended backcloth; when you are accustomed to the level perspectives of the plains, the surprising effects that you encounter at every step in the mountains seem impossibly fabulous.

Pass of Pancorbo

The posada at which we stopped for dinner had a stable as its vestibule. This architectural arrangement is invariably repeated in all Spanish posadas, and to reach your room you are forced to pass behind the rumps of the mules. The wine, even darker than usual, also possessed a certain local bouquet of goatskin. The girls who served us wore their hair hanging down to the middle of their backs; beyond that, their clothing was that of lower-class French women. National costumes are generally only retained in Andalusia, and there are now very few traditional costumes worn in Castile. As for the men, they all wore pointed hats, trimmed in velvet with silk tassels, or somewhat fiercely-shaped wolfskin caps, and the inevitable tobacco or chimney-sweep coloured coat. Their faces, moreover, showed no notable characteristics.

From Pancorbo to Burgos we encountered only three or four small, half-ruined villages, dry as pumice and the colour of toast, including Briviesca, Castil de Péones, and Quintanapalla. I doubt that, in the depths of Asia Minor, Alexandre Decamps ever found walls more roasted, more scorched, more tawny, more grainy, more crusty and more furrowed than these. Along these walls certain donkeys ambled, which were worthy of his Turkish donkeys, and which he ought to go and study. The Turkish donkey is fatalistic, and we see from his humble and dreamy expression that he is resigned to all the blows that fate has in store for him, which he will endure without complaint. The Castilian donkey has a more philosophical and deliberate expression; he understands that we cannot do without him; he belongs to the household, has read Don Quixote, and prides himself on being a direct descendant of the famous Grison beloved of Sancho Panza. Side by side with the donkeys also wandered purebred dogs of noble race, with perfect paws, shapes, and coats, among others, large greyhounds in the style of Paul Veronese and Velasquez, of an admirable size and beauty; not to mention a few dozen muchachos or street-urchins, whose eyes sparkled amidst their rags like black diamonds.

Old Castile is, undoubtedly, so named because of the large number of old women found there: and what old women! The witches of Macbeth crossing the heath at Dunsinane to prepare their infernal cuisine, were charming young girls by comparison: the abominable shrews of Goya’s caprices, which until now I had taken for nightmares and monstrous chimeras, are simply portraits of fearful accuracy; most of these old women have beards like mouldy cheese, and moustaches like grenadiers; and then, only see their attire! If one took a piece of fabric and worked for ten years to dirty it, scrub it, pierce it, patch it, so as to rid it of its original colour, one could not achieve the sublimity of those rags! These adornments are enhanced by a haggard and fierce appearance, very different from the humble and pitiful demeanour of the French poor.

A little before arriving in Burgos, a large building on a distant hill was pointed out to us: it was La Cartuja de Miraflores (the Charterhouse), about which we will have occasion to speak more fully. Not longer after this, the cathedral’s spires gradually revealed their serrations against the sky; and half-an-hour later, we entered the ancient capital of Old Castile.

The square in Burgos, in the midst of which stands a rather mediocre bronze statue of Charles III of Spain, is large and does not lack character. Houses red in colour, supported by pillars of bluish granite, enclose it on all sides. Under the arcades, and in the square, are all kinds of small traders, while an infinite number of donkeys, mules, and picturesque peasants stroll around. The Castilians’ ragged clothes appear there in all their splendour. The least beggar is nobly draped in his cloak like a Roman emperor in his purple. These coats, can be best compared, for colour and substance, to large pieces of spongy fungi (amadou) torn apart at the edge. The cloak of Don César de Bazan, in the play Ruy Blas, does not come close to those triumphant and glorious rags. All is so threadbare, so dry, so inflammable, that one considers it imprudent to smoke or use a lighter. The little children of six to eight years old also have coats, which they wear with the most ineffable gravity. I cannot recall without laughter a poor little devil who only had a large collar which barely covered his shoulders, but who draped himself in the absent folds with such a comically pitiful air that it was enough to make one split one’s sides. Those condemned to the presidio (forced labour) sweep the city and remove the filth without emerging from the rags that swaddle them. These galley slaves in coats are indeed the most astonishing scoundrels one can see. At each sweep of the broom, they make as if to sit or lie down on a doorstep. Nothing would be easier for them than to escape, but when I raised this, I was told that they refrained from doing so due to their natural goodness of character.

The fonda at which we arrived was a genuine Spanish fonda where one heard not a word of French; we were obliged to deploy our Castilian, and force our throats to growl out the abominable jota, that Arabic and guttural sound which does not exist in our language, and I must say that, thanks to the extreme intelligence which distinguishes the natives, we were understood quite well. Sometimes a candle was brought when we had asked for water, or chocolate when we desired ink; but, apart from these small, very forgivable mistakes, everything went well. The inn was served by a crowd of dishevelled girls who bore the most beautiful names in the world: Casilda, Matilde, Balbina; the names are always charming in Spain: Lola, Bibiana, Pepa, Hilaria, Carmen, Cipriana, serve as a label for the least poetic creatures that one can see; one of these girls had hair of a most vehement red, a colour which is quite common in Spain, where there are many blondes and many redheads especially, contrary to the generally accepted belief.

They do not put mere sprigs of the boxwood blessed on Palm Sunday in the rooms here, but large branches in the shape of palm-fronds, plaited, and woven together in spirals, with great elegance and care. The beds lack a bolster, but own to a pair of flat pillows placed one on top of the other; they are generally very hard, though the woollen mattresses are fine; but they are not in the habit of carding the wool, they only turn it over with the tips of a pair of rods.

In front of our windows, we viewed a strange sign, that of a leading surgeon who had thereon been depicted, with a student, sawing off the arm of a poor devil sitting on a chair, and we could also see a barber’s shop, the barber, I swear, in no way resembling Figaro. We saw through his window the gleam of a large, somewhat shiny shaving dish of yellow copper, which Don Quixote, if he were of this world, might well have taken for Mambrino’s helmet. Spanish barbers, if they have lost their traditional costume, have retained their skill, and shave one with great dexterity.

Through having been the principal city of Castile for so long, Burgos has failed to retain a pronounced Gothic appearance; With the exception of one street where one sees a few windows and porticos from the time of the Renaissance, with coats of arms supported by statues, the houses hardly date back beyond the beginning of the seventeenth century, and are nothing if not vulgar; they are outdated but not ancient. Yet Burgos has its cathedral, one of the most beautiful in the world; unfortunately, like all Gothic cathedrals, it is embedded amongst a crowd of ignoble buildings, which prevent us from appreciating it as a whole and grasping its sheer mass. The main portal opens onto a square, in the midst of which a pretty fountain rises, topped with a fine white marble statue of Christ, the focal point of all the city’s pranksters, who enjoy no sweeter pastime than throwing stones at sculptures. This portal, which is magnificent, decorated, pierced and burgeoning like lace, was unfortunately scraped and planed down to the first frieze by unknown Italian prelates, great lovers of simple architecture, sober walls and ornamentation executed in good taste, who wanted to present the cathedral in the Romanesque style, feeling great pity for these poor barbarians of architecture. little practised in the Corinthian order, and appearing to know nothing of the benefits of the Attic style and the triangular pediment. Many people are still of this opinion in Spain, where the Messidor style flourishes in all its purity, preferring to the most ornate and richly-chiselled Gothic churches all kinds of abominable buildings pierced by many windows and decorated with columns like those at Paestum, just as in France before the Romantic school had restored the Middle Ages to a place of honour, and made people understand the meaning and beauty of their cathedrals. Here, twin sharp, saw-toothed spires, carved as if with a template, scalloped, embroidered, and chiselled, down to the smallest detail, as on the bezel of a ring, soar towards God with all the ardour of faith, and all the passion of an unshakeable conviction. These are not our doubting bell-towers that dare to venture into the sky supported only by their own stone lacework and ribs as thin as spider’s silk. A further tower, also sculpted with incredible richness, but less lofty in height, marks the place where the transept crosses the nave, and completes the magnificence of the silhouette. An innumerable crowd of statues: saints, archangels, kings, monks, animates all this architecture, and the stony population is so numerous, so crowded, so teeming, that it surely exceeds in quantity the flesh and blood population occupying the city.

Thanks to the grace and kindness of the civil governor, Don Henrique de Vedia, we were able to visit the cathedral and appreciate its smallest details. An octavo volume describing it, an atlas of two thousand plates, twenty rooms filled with moulded plasterwork, would still fail to give a complete idea of that prodigious efflorescence of Gothic art, denser and more complex than the virgin forests of Brazil. I who could only write a simple note or two, scribbled hastily, and from memory alone, on the corner of a posada table will be forgiven for various omissions, and a degree of negligence.

On first stepping into the church, you are halted in your tracks by an incomparable masterpiece: it is the carved wooden double-door which opens onto the cloister. It represents, among its other bas-reliefs, the entry of Our Lord into Jerusalem; its jambs and sills are filled with delightful figurines, of the most elegant shape and of such finesse that one cannot understand how an inert and opaque material like wood can lend itself to such capricious and yet spiritual fantasy. It is undoubtedly the most beautiful double-portal in the world after that of the Baptistery in Florence designed and cast by Ghiberti, which Michelangelo, who knew it, found worthy of adorning the entrance to paradise. The admirable panels of the Burgos door, should be moulded and cast in bronze, to ensure for them all that space of eternity which is at humankind’s disposal.

The choir, in which the stalls, called silleria, are located, is enclosed by wrought iron grilles of inconceivable workmanship; the pavement is covered, as is the custom in Spain, with immense mats of esparto-grass, and each stall also has its own carpet of dried grasses or rushes. Raising one’s head, one sees a kind of dome formed by the interior of the tower of which we have already spoken; it is an abyss filled with sculptures, arabesques, statues, columns, ribs, lancets, and pendants dizzying in their effect. One could gaze upwards for a year and more and still not have viewed all its details. It is densely-formed like a cabbage, pierced rectangularly like a fish-slice, vast as a pyramid, and delicate as a woman’s earring, and one cannot understand how such a filigree could have hung in the air for so many centuries! Who were the men who executed these marvellous constructions unsurpassed by the prodigality of fairy palaces? Is that race of individuals lost? And we, who boast of being civilized, are we, in fact, merely decrepit barbarians? A deep feeling of sadness grips my heart on visiting one of these prodigious buildings of bygone times; I become immensely discouraged, and only aspire to retire to a corner, set a stone beneath my head, and wait, in an immobility of contemplation, for death, that absolute immobility. What is the point of our labours? What is the point of all our fuss and noise? The most extreme of human efforts will never reach beyond this. Ah well! We know not the names of these divine artists, and to find some trace of them, we must search the dusty archives of the monasteries. When I think that I have spent the best part of my life rhyming ten or twelve thousand lines, writing six or seven poor octavo volumes, and three or four hundred trivial newspaper articles, and find myself wearied by it, I am ashamed of myself and of this age, where so much effort produces so little. What is a thin sheet of paper next to a mountain of granite?

If you would like to tour this immense madrepore with us, this mass of coral built by those prodigious human polyps of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, we will commence with the small sacristy, which is quite a large room despite its title, and contains an Ecce Homo, a Christ on the Cross by Murillo, and a Nativity by Jacob Jordaëns, framed in richly carved woodwork; in the middle a large brazier is set, which is used to light the censers, and cigarettes too perhaps, since many a Spanish priest smokes them, a thing which seems no more improper to me than snuffing powdered tobacco, a pleasure the French clergyman has no scruple in permitting himself. The brazier is a large yellow-copper basin placed on a tripod and filled with embers or small lit coals covered with fine ash, producing a gentle flame. In Spain, braziers stand in for fireplaces, which are extremely rare.

In the large sacristy, next to the small one, we note a Christ on the Cross by Dominikos Theotokopoulos, better known as El Greco, an extravagant and most singular painter, whose works one might take for sketches by Titian, if it were not that a certain affectation of elongated and exaggerated forms makes them instantly recognisable. To render his paintings with a touch of pride, he applies here and there brush strokes of incredible petulance and brutality, thin, sharp gleaming strokes which traverse the shadows like sabre blades: all of this does not prevent El Greco from being a great painter; the fine works of his secondary style closely resembling the Romantic paintings of Eugène Delacroix.

You will have undoubtedly viewed, in the Spanish Museum in Paris, the portrait of El Greco’s daughter, attributed to him, a magnificent rendering that no master would disown, and can therefore judge what an admirable painter he must have been; when he was in his right mind, that is. It seems that his concern to avoid imitating Titian, of whom it is claimed that he had been a student, disturbed his brain and caused him to display a degree of extravagance and caprice which allowed the magnificent faculties he had received from Nature to emerge only in intermittent glimmers; El Greco was also architect and sculptor, that sublime trinity, a luminous triad, often encountered in the heavens of supreme art.

The walls of this sacristy hold woodwork cabinets, their scalloped columns carved with flowers, of the richest taste; above the woodwork a row of Venetian mirrors reigns, the point of which I can scarcely understand, unless they are purely ornamental, since they are too high up for one to be able to gaze into them. Higher than the mirrors, with the oldest touching the vaulted ceiling, portraits of all the bishops of Burgos are arranged in chronological order, from the first to he who today occupies the episcopal see. These portraits, though painted in oil, have a pastel, tempera appearance deriving from the fact that paintings are left unvarnished in Spain, a lack of precaution which has allowed many fine masterpieces to be consumed by humidity, a thing to be regretted. These portraits, although most of them are very detailed, are not paintings of the first order, and moreover they are hung too high for one to be able to judge the merit of their execution. The centre of the room is occupied by an enormous buffet, and immense baskets woven from espartos, in which church ornaments, and utensils of worship, are stored. Under two glass domes, two coral trees are kept as a curiosity, though much less complex in their branches than the slightest arabesque of the cathedral. The door is decorated with the arms of Burgos in relief, with a scattering of small heraldic-red crosses.

Jean Cuchiller’s chapel, which we passed through next, is nothing remarkable in terms of its architecture, and we were hastening to leave it, when we were asked to raise our eyes and observe a most curious object. This was a large chest held against the wall by iron clamps. It is difficult to imagine a more patched-up, worm-eaten, and ruined trunk. It is without doubt the oldest chest in the world; an inscription in black letters conceived thus: Cofre del Cid, immediately granted, as you can believe, enormous importance to these four boards of rotten wood. This chest, if the chronicle is to be believed, is precisely the one that the famous Ruy Diaz de Vivar, better known under the name of El Cid Campéador, lacking money, hero though he was, like many a plain writer, offered, filled with a mass of sand and stones, as collateral to an honest Jewish pawnbroker who furnished loans, with a prohibition on opening the mysterious trunk before he, El Cid Campéador, had repaid the amount borrowed; which proves that the usurers of that time were more easy-going in nature than those of our day. We would now find few Jews or Christians naive and good-natured enough to accept such a pledge. Monsieur Casimir Delavigne made use of this legend in his play La Fille du Cid, but he substituted for the enormous chest a less than imposing box, which contained nothing but the gold of El Cid’s words; and no Jew, even a Jew of the heroic age, would lend anything in exchange for such a box of bonbons. The ancient chest is large, wide, heavy, deep, and furnished with all kinds of locks and padlocks: full of sand, it would have taken at least six horses to move it, and the worthy Israelite might well have supposed it filled with clothes, jewels, or silverware, and have resigned himself more easily to the Cid’s caprice, a caprice provided for by the Penal Code, as it provides for many another heroic fantasy. With all due respect to Monsieur Anténor Joly, his staging of Renaissance theatre is therefore inexact,

Part V: The Cloister; Paintings and Sculptures – The House of El Cid; The Rope House; The Santa Maria Gate – The Theatre and the Actors – La Cartuja de Miraflores – General Thiébault and the Bones of El Cid

On leaving Jean Cuchiller’s chapel, one enters another room with a most picturesque style of decoration: oak woodwork, crimson hangings, and a ceiling of Cordoba leather displayed to best effect; in this room can be seen a Nativity by Murillo, a Conception, and a painting depicting Jesus in a most finely-achieved robe.

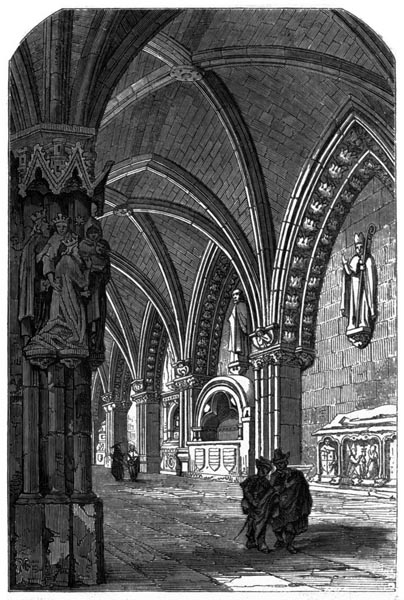

The cloister is filled with tombs, most of them closed off by tight and extremely strong iron grills; these tombs, all of illustrious character, are carved into the thickness of the wall, adorned with coats of arms and studded with sculptures. On one of them I noticed a group consisting of Mary and Jesus holding a book in their hands, of great beauty, and a chimera half-animal, half-arabesque, of the strangest and most impressive invention. Upon all these tombs lie life-size statues, either of armed knights or of bishops in their regalia, which one might readily mistake, through the iron mesh of the gates, for the dead they represent, so realistic are the poses and the slightest details.

Cloisters, Burgos Cathedral

On a door-jamb, I noticed, in passing, a charming little statuette of the Virgin, of delightful execution and extraordinary boldness of conception. Instead of the contrite and modest air that is usually granted to the Blessed Virgin, the sculptor has represented her with a look in which voluptuousness mixes with the ecstasy and the intoxication of a woman about to give birth to a god. She stands there, her head thrown back, breathing in, with all her soul and body, the ray of fiery light emitted by the symbolic dove, with a combination of ardour and purity of rare originality; it is difficult to achieve anything new with regard to a subject so often repeated, but to genius no subject is ever exhausted.

The description of the cloister alone would require an entire book; but, given the little space and time I have, you will forgive me for uttering only those few words, and entering on the church, where I will address at random, to right and left, the masterpieces as they come, without choice or preference; because all there is beautiful, all is admirable, and what I shall not speak of equals at the very least what I shall.

One first comes to a halt in front of the Passion of Jesus Christ, in stone, by Philippe de Bourgogne, who was unfortunately not a French artist, it seems, as his name, or rather his epithet, might lead one to believe. It is one of the largest bas-reliefs in the world. According to Gothic practice, it is divided into several compartments; The Garden of Olives, The Bearing of the Cross, The Crucifixion between the Two Thieves; an immense composition indeed, which, as regards the finesse in execution of the heads and the richness of detail, is worth anything that Albrecht Durer, Hans Memling, or Holbein wrought, of a most delicate and elegant nature, with their miniaturist’s brushes. This stone epic ends with a magnificent Descent to the Tomb: the groups of sleeping apostles who occupy the lower panels of The Garden of Olives are almost as beautiful and as pure in style as the prophets and saints of Fra Bartolommeo; the heads of the blessed women at the foot of the cross show a pathetic and painful expression of which Gothic artists alone possessed the secret, here this expression joins with rare beauty of form; the soldiers stand out for their singular and fierce accoutrements such as those attributed to ancient, oriental or Jewish characters of the Middle Ages whose true costumes we do not know; they are also portrayed with a boldness and bravado which make the happiest contrast with the ideality and melancholy of the other figures. All this is framed by architecture formed like goldsmith’s work, of incredible lightness and good-taste. The sculpture was completed in 1536.

Since we are on the subject of sculpture, let us speak at once of the choir-stalls, admirable works of carpentry perhaps unrivalled in the world. These stalls are so many marvels; they represent subjects from the Old Testament in bas-relief, and are separated from each other by chimeras and fantastic animals in the shape of seat-arms. The flat panels are formed with incrustations, highlighted with black hatching, like niello work on metal; arabesque and caprice have never been taken further. Here is inexhaustible verve, incredible abundance, perpetual invention both in idea and execution; it is a new world, a separate creation, as complete, as rich, as that of the deity, where plants are alive, men flower, where a branch ends in a hand and a leg in foliage, where the sly-eyed chimera opens wings equipped with claws, where the monstrous dolphin emits water through its blowhole. An inextricably interwoven mesh of florets, foliage, acanthus leaves, lotus blooms, flowers with calyxes decorated with egret-feather aigrets and tendrils, serrated and contoured vegetation, fabulous birds, impossible fish, mermaids, and extravagant dragons, of which no language can convey even the idea. The freest fantasy reigns in all these inlays, to which their yellow tone on the darker background of the wood grants the appearance of Etruscan vase-painting, an appearance completely justified by the frankness and primitive accent of the line. These images, which the pagan genius of the Renaissance illuminates, have no connection with the purpose of the stalls, and sometimes the choice of subject reveals complete forgetfulness of the holiness of its location. There are children playing with masks, women dancing, gladiators wrestling, peasants harvesting grapes, young girls tormenting or caressing some fantastic monster, creatures plucking harps, and even little boys imitating in the basin of a fountain the famous Manneken-Pis in Brussels. With a little more slenderness in their proportions, these figures would be equal to the purest Etruscan forms: unity of appearance coupled with infinite variety of detail, that is the difficult problem that medieval artists almost always solve with success. Five or six paces away, this carpentry, so fanciful in execution, becomes serious, solemn, architectural, brown in tone, and entirely worthy of serving as a frame for the pale and austere faces of the canons.

The Constable’s chapel (Capilla del Condestable) is in itself a complete church; the tombs of Don Pedro Fernandez de Velasco, Constable of Castile, and that of his wife, occupy the centre and are without the slightest ornamentation; the sculpted figures are of white marble and magnificent workmanship. The man lies in his battle-armour enriched with arabesques in a superior style, from which the sacristans make prints on moist paper which they sell to travellers; the woman has her little dog beside her; her gloves and the patterns of her brocade dress being rendered with incredible finesse. The heads of the two spouses rest on marble cushions, decorated with their crowns and their coat of arms; gigantic coats of arms decorate the walls of the chapel, and, on the entablature, figures are placed bearing stone poles to support banners and standards. The retablo (which is what the architectural facade around an altar is called) is sculpted, gilded, painted, interspersed with arabesques and columns, and represents the circumcision of Jesus Christ, with life-size figures. On the right where hangs a portrait of Doña Mencia de Mendoza, Countess of Haro, there is a small illuminated, gilded, chiselled Gothic altar, embellished with a host of figurines, thought to be by Antonin Moine, since they are so light and spiritually oriented; on this altar there is a Christ in black jet. The great altar is decorated with silver blades and crystal suns, whose shimmering reflections form plays of light of singular brilliance. At the summit of the vault a sculptured rose of incredible delicacy blooms.

In the sacristy which is close to this chapel, we see embedded a midst of the woodwork a Mary Magdalen which is attributed to Leonardo da Vinci: the softness of the brown half-tones blended with the light ones by imperceptible degrees, the lightness of touch displayed in the hair, and the perfect roundness of the arms make this supposition entirely plausible (the painting ‘The Enigma of Mary Magdalen’, is currently attributed to Gianpetrino one of his pupils). Also kept in this chapel is the ivory diptych which the constable took to the army and before which he said his prayers. The Capilla del Condestable belongs to the Duke of Frias. Take a passing look at the statue of Saint Bruno, in coloured wood, which is by Manuel Pereira, a Portuguese sculptor, and at the tomb of Pedro Fernández de Villegas, translator of Dante’s Inferno.

A grand staircase of the most beautiful design, with magnificent sculpted chimeras, held us spellbound for a few minutes. I have no idea where it led and into which room the little door at its end opened; but it is worthy of the most dazzling palace. The great altar of the chapel of the Duke of Abrantès (the chapel of Santa Ana) is one of the most singular works that can be viewed: it represents the genealogical tree of Jesus Christ. Here is how this curious idea is rendered: the patriarch Abraham is lying down at the foot of the composition, and into his fertile chest plunge the hairy roots of an immense tree, each branch of which bears an ancestor of Jesus, and is subdivided into as many branches as there were descendants. The summit is occupied by the Blessed Virgin, on her throne among the clouds; the sun, moon and stars, in silver and gold, sparkle through an efflorescence of branches. The degree of patience it took to carve all those leaves, sculpt those folds, hollow out those branches, separate all those characters from the background, we dare not think of except with fear. This retablo, so worked, is as large as the facade of a house, and rises at least thirty feet high, including three levels, the second of which contains a Coronation of the Virgin, and the last a Crucifixion with Saint John and the Virgin. The artist was Rodrigo del Haya (sculptor of the main altarpiece of the cathedral) who lived in the mid-16th century (the work is now attributed to Gil de Siloé, its main section completed 1492).

The chapel of Saint Thecla is as curious as one can imagine. Both architect and sculptor seem to have set themselves the goal of as much ornamentation as possible in as little space as possible; They succeeded perfectly, and I would challenge the most industrious ornamentalist to find place in the entire chapel for a single rose window or a single fleuron. It is in the richest, most adorable, and most charming bad taste: nothing but twisted columns surrounded by vine-stocks, infinitely coiled volutes, little chains of cherubs with winged cravats, great bubbles of cloud, flames blowing in the wind emitted from perforated boxes, open fans of light rays, blooming and bushy chicory plants, all gilded and painted in natural colours, with miniature brushes. The patterns of drapery are executed thread by thread, point by point, and with fearful meticulousness. The saint, surrounded by the flames of her pyre, flames whose ardour is aroused by Saracens in extravagant costumes, raises her beautiful enamelled eyes to the sky, and holds in her little flesh-coloured hand a large sacred branch, curled in the Spanish manner. The vaults were worked in the same taste. Other altars, of a smaller size, but of equal richness, occupy the rest of the chapel: here is no Gothic finesse, nor the charming taste of the Renaissance; richness is substituted for purity of line; yet it is still very beautiful, as is everything excessive and complete in its own way.

The cathedral-organs, which are of formidable size, possess batteries of organ-pipes arranged on a transverse plane like cannons, aimed with menacing and bellicose effect. The private chapels each have their own organ, but smaller. On the retablo of one of these chapels (the Chapel of the Presentation) we saw a painting of such beauty that I know not to which master it should be attributed, except perhaps to Michelangelo; the undeniable characteristics of the Florentine school in its finest period shine out victoriously from this magnificent painting, which would be the pearl of the most splendid of museums. However, Michelangelo almost never painted in oil, and his paintings are fabulously rare; I would gladly believe that the composition was painted by Sébastien del Piombo, following the outlines of a cartoon by the sublime artist. We know that, jealous of Raphael’s success, Michelangelo sometimes employed Sebastian del Piombo to combine colour with drawing and surpass his young rival. Regardless, it is an admirable painting; the Holy Virgin, seated and nobly draped, veils with a transparent scarf the divine nudity of little Jesus, standing next to her. Two angels, in contemplation, swim silently in the ultramarine of the sky; in the background we see a harsh landscape, rocks, earth and a few distant sections of wall. The head of the Virgin has a majesty, calmness, and power that cannot be conveyed in words. The neck is attached to the shoulders by lines so pure, so chaste and so noble, the face breathes such sweet maternal tranquility, the hands are turned so divinely, the feet have such elegance and such great style, that one cannot can take one’s eyes from this painting. Add to this marvellous sketch a simple, solid colour, sustained in tone, without false lights, without the lesser refinements of chiaroscuro, with a certain touch of the fresco that harmonizes perfectly with the tone of the architecture, and you have a masterpiece of which one can find the equivalent only in the Florentine or Roman schools.

There is also, in the cathedral of Burgos, a Holy Family without the painter’s name, which I strongly suspect to be by Andrea del Sarto, and Gothic paintings on wood by Cornelis van Eyck, the like of which can be found in the Dresden Gallery; paintings of the German school are not rare in Spain, and some are of great beauty. We will mention, in passing, some paintings by Fra Diego de Leyva, who became a Carthusian at the Cartuja de Miraflores, at the age of fifty-three, among others the one which represents the martyrdom of Saint Casilda, whose breasts the executioner severed: blood gushes in large quantities from two crimson patches left on the chest by the amputated flesh; the two half-globes lie next to the saint, who looks, with an expression of feverish and convulsive ecstasy, at a large angel with a dreamy and melancholy face who brings her a palm-frond. These fearful paintings of martyrs are very numerous in Spain, where the love of realism and truth in art is pushed to the ultimate limits. The artist spares one not a single drop of blood; we are forced to view the severed veins which retract, the living flesh which trembles, and whose dark purple contrasts with the bloodless and bluish whiteness of the skin, the vertebrae cut by the executioner’s scimitar, the violent marks left by the rods and whips of tormentors, the gaping wounds that vomit water and blood from their livid mouths: everything is rendered with terrible truth. Jusepe de Ribera painted, in this genre, things that would make even el verdugo, the executioner himself, recoil with horror, and it takes all the terrible beauty and diabolical energy which characterize that great master to support such ferocious depictions of flaying and the slaughterhouse, which seem to have been painted for the pleasure of cannibals by the executioner’s servant. There is truly something disgusting about martyrdom, and the angel with its palm-frond seems slight compensation for such atrocious torment. Yet Ribera very often refuses this consolation to his tortured figures, whom he leaves to writhe, like severed parts of a snake, in dark menacing shadows that no divine ray illuminates.

The longing for the actual, however repulsive it may be, is a characteristic feature of Spanish art: the ideal and the conventional are not part of the genius of a people completely devoid of aesthetics. Sculpture is not enough for it: it requires painted statues, rouged Madonnas with realistic clothes. Material illusion is never carried far enough to satisfy its taste, and that unbridled love of realism often makes it traverse the distance that separates statuary from Philippe Curtius’ cabinet of wax figures.

The famous and revered Burgos Christ, which can only be seen once candles are lit, is a striking example of this strange taste: here is no longer stone or illuminated wood, but human skin (at least so they say), padded with great art and care. The hair is real hair, the eyes have eyelashes, the crown of thorns is made of real briars, no detail is forgotten. Nothing is more lugubrious and more disturbing to see than this elongated, crucified ghost, with its false evocation of life and its dead immobility; the skin, of a rancid and brown tone, is streaked with long streams of blood so well imitated that one might believe that they were actually flowing. It takes no great stretch of the imagination to believe the legend that this miraculous crucifix bleeds every Friday. Instead of gathered loose drapery, the Burgos Christ wears a white petticoat embroidered with gold which hangs from his waist to his knees; this addition produces a singular effect, especially for those who are not used to seeing Our Lord thus costumed. At the foot of the cross three ostrich eggs are embedded, a symbolic emblem whose meaning escapes me, unless it is an allusion to the Trinity, the source and seed of all.

We left the cathedral dazed, crushed, intoxicated by masterpieces and unable to admire it further. We had strength, at most, to cast an absent-minded glance at the arch of Fernán González, an attempt at classical architecture, created at the start of the Renaissance by Philippe de Bourgogne. We were also shown the Cid’s house; when I say the Cid’s house, I express myself badly, I mean the site where it may have been: it consists of a square of land surrounded by boundary-markers; there remains not the slightest vestige authorising this belief, but also nothing to indicate the contrary, and, in such a case, there is no detriment in relying on tradition. The Rope House, so named for the stone coils of rope that border the doors, frame the windows, and embellish the architecture, is worthy of examination; it serves as the residence of the civil governor of the province, and we met there a group of mayors from the surrounding area, whose physiognomy would have seemed suspicious at the corner of a wood, and who would have done well to demand of themselves their own identification papers before permitting themselves to go about freely.

The Santa Maria Gate, built in honour of Charles V, is a remarkable piece of architecture. The statues placed in the niches, though short and stocky, have a strength of character and a power which makes up for their lack of slenderness. It is a shame that this superb triumphal gate is obstructed and shamed by I know not how many plastered walls erected there on the pretext of providing fortification, and which it should be a matter of urgency to raze to the ground. Near this gate is the promenade which runs along the Arlanzón, a most respectable river, two feet deep at least, which is a great deal in Spain. The promenade is decorated with four statues representing four kings or counts of Castile of a rather fine appearance, namely: Don Gonzalo Fernández, Don Alonzo, Henry II and Ferdinand I. That is almost all that is worth seeing in Burgos. The theatre is even cruder than that of Vitoria. That evening a play in verse was performed there: El Zapatero y el Rey (the Shoemaker and the King) by José Zorilla a most distinguished young writer, extremely popular in Madrid, who has already published seven volumes of verse, which boast of both style and harmony. All the seats had been booked in advance; we were forced to deprive ourselves of the pleasure and wait till next day for a performance of Charles Favart’s Les Trois Sultanes, interspersed with Turkish songs and dances of transcendent foolishness. The actors knew not a word of their parts, and the prompter shouted the text at the top of his lungs, thereby drowning out their voices. The prompter is protected by a tin carapace, a rounded lid on four sides, against the patatas, manzanas and cascaras de naranja, potatoes, apples and orange peel, with which the Spanish audience, impatient as they were, never failed to bombard actors who displeased them. Everyone carries their own supply of projectiles in their pockets; if the actors have performed well, the vegetables are returned to the pot to add to the stew, the puchero.

The Santa Maria Gate

For an instant we thought we had found the true Spanish female type in one of the three Sultanas: large arched black eyebrows, thin nose, elongated oval face, red lips; but an officious neighbour told us that it was a young French girl.

Before leaving Burgos, we paid a visit to the Cartuja de Miraflores, located half a league from the city. Some poor aged and infirm monks were allowed to lodge in this charterhouse awaiting their end. Spain lost much of its romantic character with the suppression of the monasteries, and I fail to see what it gained in other respects. Admirable buildings whose loss is irreparable, and which had been preserved until then in a most meticulous manner, full of integrity, will deteriorate, collapse, and add their ruins to the ruins already so frequent in that unfortunate country; an incredible wealth of statues, paintings, art objects of all kinds, will be lost without benefit to anyone. It seems to me that one could imitate our Revolution in a better way than through foolish vandalism. To cut each other’s throats for the ideas you think to possess, to fertilise with your bodies the meagre fields ravaged by war, such is good; but stone, marble and bronze touched by genius are sacred; spare them. In two thousand years your civil discords will be forgotten, and posterity will only know you were a great people through a few marvellous fragments found by excavation.

La Cartuja is sited on top of a hill; the exterior is austere and simple: grey stone walls, tiled roofs; everything for the mind, nothing for the eyes. Inside, there are long, cool, silent cloisters whitewashed with quicklime, the doors of cells, lead-meshed windows in which are enshrined a few sacred objects in coloured glass, in particular an Ascension of Jesus Christ, singular in its composition: the body of the Saviour has already disappeared; we see only his feet, the hollow imprints of which have remained in the surface of a rock surrounded by holy figures expressing adoration.

A small courtyard, in the centre of which a fountain rises from which crystal-clear water filters, drop by drop, encloses the prior’s garden. A few vines brighten somewhat the gloom of the walls; a few clumps of flowers, a few sheaves of plants grow here and there, mostly at random and in picturesque disorder. The prior, an old man with a noble and melancholy face, dressed in a garment resembling a coarse robe as much as anything (monks were not allowed to retain their habit), received us with great politeness and made us sit round a brazier, since the weather was not too hot, and offered us cigarettes and azucarillos (lumps of sugar) in cold water. A book was open on the table; I allowed myself to take a look: it was the Bibliotheca Carluxiana, a collection of passages from various authors praising the order and way of living of the Carthusians. The margins were annotated, in the prior’s own hand, with that good old priestly handwriting, straight, firm, somewhat large, which speaks of long reflection, and which a hasty, anxious, and worldly person might attempt in vain to acquire. So, this poor old monk, left there out of pity in an abandoned monastery whose vaults might well shortly collapse above his unknown grave, still dreamed of the glory of his order, and with a trembling hand inscribed on the white pages of the book some passage, forgotten and newly-discovered.

The cemetery is shaded by two or three large cypress trees, as in Turkish cemeteries: this funerary enclosure contained four hundred and nineteen Carthusians who had died since the construction of the monastery; thick, bushy grass covers the ground, where we find neither grave, cross, nor inscription; they lie there confusedly, humble in death as they were in life. This anonymous cemetery has something calm and silent which eases the soul; a fountain, placed at the centre, mourns, its tears clear as silver, all those poor forgotten dead; I took a sip of the water filtered through the ashes of so many holy people; it was pure and icy as death.

Yet if the dwelling of men is poor, that of God is rich. In the midst of the nave are the tombs of Don Juan II and Isabel of Portugal, his wife. We would be surprised if human patience has ever achieved a like work: sixteen lions, two at each corner, supporting eight escutcheons with the royal arms, serve as their base. Add a proportionate number of virtues, allegorical figures, apostles and evangelists, and have branches, foliage, birds, animals, coiling arabesques wind through it all, and you will have but a poor idea of this prodigious work. The crowned statues of the king and queen repose on the lid. The king holds a sceptre in his hand, and wears a long garment, carved and decorated with inconceivable delicacy.

The tomb of Infante Alonso is on the left of the altar, the Gospel side. The infante is represented kneeling in front of a prie-dieu. A vine pierced with holes, on which small children hang to pick grapes, festoons, with inexhaustible caprice, the Gothic arch which frames the composition half-embedded in the wall.

These marvellous monuments are carved from alabaster, and by the hand of Gil de Siloé, who also carved the sculptures of the high altar; to the right and left of this altar, which is of rare beauty, two doors open through which we see two motionless Carthusians in garments like white shrouds: these two figures, which are probably by Diego de Leyva, deceive the eye at first glance. Alonso de Berruguete’s choir-stalls complete this ensemble, which one is surprised to find amidst a deserted countryside.

From the top of the hill, we were shown the monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña, in the distance, where the tomb of El Cid and Doña Jimena, his wife, is located (the tomb is now in Burgos Cathedral). About this tomb, a bizarre anecdote is told which we will repeat, without guaranteeing its authenticity.

During the French invasion, General Thiébault had the idea of transferring the bones of El Cid from San Pedro de Cardena to Burgos, with the intention of placing them in a sarcophagus on the public promenade, in order to inspire heroic and chivalrous feelings in the population through the magnanimous placement of these relics. It is said, in addition, that, in a fit of militaristic enthusiasm, the honourable general slept beside the hero’s bones, to summon up the courage for this glorious removal, a precaution of which he had no need. The project was not carried out, and the Cid returned to Doña Jimena, in San-Pedro de Cardena, where he remained thereafter; but one of his teeth, which came loose, and which had been stuck in a drawer, disappeared without anyone knowing what had become of it. The only glory lacking to the Cid was that of being canonized; as he would have been if, before dying, he had not had the heretical and offensive Arabic idea of wishing his famous horse Babieca to be buried beside him: which led to grave doubts concerning his orthodoxy. In regard to the Cid, we should point out to Monsieur Casimir Delavigne that the hero’s sword is called Tizona and not Tizonade, which rhymes too closely with lemonade. All I have said detracts not at all from the glory of El Cid, who, in addition to his merit as a hero, has so potently inspired the unknown poets of the Romancero, Guillén de Castro, Juan Diamante, and Pierre Corneille.

Part VI: El Correo Real; The Galleys – Valladolid – San Pablo – A Performance of Hernani – Santa Mária la Real de Nieva – Madrid

El correo real, in which we left Burgos, deserves special mention. Imagine an antediluvian carriage, the obsolete model for which can only be found in fossilized Spain; enormous wheels, with very thin spokes, spreading far from the chassis, painted red in the time of the Catholic Isabella; an extravagant superstructure, pierced with windows of all shapes, and lined inside with small satin panels which may have been pink at some remote time, enhanced with sewn decorations in chenille, which nothing has barred from being executed in several different colours. This respectable carriage was crudely suspended by means of ropes, and secured in vulnerable places with esparto-cord. To this vehicle was added a line of mules, a string of the creatures of reasonable length, with an assortment of postilions and mayorales in jackets of Astrakhan lambskin, and sheepskin trousers of a very Muscovite appearance, after which we left amidst a whirlwind of cries, insults and whip-lashes. We went at a breakneck pace, devouring the terrain, as the vague silhouettes of objects flew past, to right and left, with phantasmagorical speed. I have never seen mules more inspired, restive or fiercer; at each relay-post, it took a veritable army of muchachos to attach each one to the carriage. These diabolical beasts emerged from the stable rearing on their hind feet, and it was only by means of a cluster of postilions hanging from their halters that they were eventually reduced to a state of quadrupedalism. I believe what inspired their frenzied ardour was the idea of the meal that awaited them at the next venta (inn) because they were fearfully lean. On leaving one little village, they began to kick and rear so furiously that their legs became caught in the traces: then there ensued a flurry of kicks, and unimaginable blows with sticks; the whole file collapsed, and an unfortunate postilion who was at the head, mounted on a horse which had probably never been harnessed, was pulled out from beneath the almost flattened heap, bleeding from the nose. His mistress, who was present at the departure, uttered soul-splitting screams such as I would not have believed could emerge from the human chest. In the end, we managed to untangle the ropes and set the mules back on their feet; another postilion took the place of the wounded man, and we set off with unparalleled speed. The country we crossed had an aspect of unusual savagery: large arid plains without a single tree to break their uniformity, ending in mountains and hills of yellow ochre that distance could barely render bluish. From time to time we traversed earthy villages, built of adobe, mostly in ruins. As it was a Sunday, lines of haughty Castilians draped in their spongy rags, stood, motionless as mummies all along the yellowish walls lit by pale rays of sunlight, engaged in tomar el sol (taking the sun), a recreation which would make the most phlegmatic German die of boredom in an hour. However, this most Spanish of pleasures was very excusable that day, since it was atrociously cold, a furious wind sweeping across the plain with a noise like the thunder of chariots full of armour rolling over bronze vaults. I cannot believe that in Hottentot kraals or Kalmyk encampments one would encounter anything more savage, more barbaric, and more primitive. Taking advantage of a halt, I entered one of the houses: it was a windowless hovel, with a crude stone hearth placed in the centre, and a hole in the roof to allow the smoke to escape; the walls were covered with a dark bitumen worthy of Rembrandt.

We dined at Torquemada a pueblo located on a small river partially blocked by old ruined fortifications. Torquemada is remarkable for the complete absence of any windows: the only tiling is in the parador which, despite this incredible luxury, nevertheless has a kitchen with a hole in the ceiling. After having swallowed a few garbanzos (chickpeas) which rattled into our bellies like grains of lead onto a tambourine, we returned to our carriage, and the steeplechase began again. The carriage, on the heels of those mules, was like a saucepan attached to a tiger’s tail: the noise it made aroused them even more. A fire of straw lit in the middle of the road very nearly made them take the bit in their teeth. They were so suspicious that you had to hold them by the reins and put your hand over their eyes when another carriage came in the opposite direction. As a general rule, when two carriages pulled by mules meet, one of them must overturn. Finally, what was fated to happen happened. I was turning over some fragment of a hemistich in my head, as is my habit when travelling, when I saw my comrade, who was seated opposite, lurch towards me, in a sudden parabola; this unusual action was followed by our abrupt arrest, and a general cracking sound: ‘Are you dead?’ my friend asked me as he terminated his course. ‘On the contrary,’ I replied, ‘and you?’ ‘Hardly at all,’ he replied. And we emerged as quickly as possible through the broken roof of the poor carriage which had broken into a thousand pieces. We saw with infinite satisfaction, fifteen paces away in a field, the case containing our daguerreotype equipment as fresh and intact as if it had still been in the Susse Brothers’ shop, busily taking views of the colonnade of the Bourse. As for the mules, they had fled, taking with them the front-axle and the two smaller wheels. Our losses amounted to a button which had popped due to the violence of the shock and could no-longer be found, it is genuinely impossible to overturn in more admirable fashion.

One of the most comical things I have seen was the mayoral’s lament over the wreckage of his carriage; he tried to fit the pieces back together like a child who has broken a glass, and, finding the damage irreparable, he burst forth in a dreadful bout of swearing, stamped his feet, punched himself, rolled on the ground, imitating the excesses of ancient tragedy, or, deeply-moved, indulged in the most touching elegies. What distressed him most was the fate of the pink cushions scattered here and there, torn, and soiled with dust; these cushions were the most magnificent thing his mayoral imagination could conceive, and his heart bled to see so much splendour vanquished.

Our position otherwise was not too cheerful, though we were attacked by a rather untimely fit of laughter. Our mules had vanished like smoke, and we had nothing left but a dismantled carriage without wheels. Fortunately, the venta (inn) was not far away. There, we found two galleys, which took us and our luggage. The galley perfectly justifies its name: it consists of a cart with two, or four, wheels, which has neither base nor flooring; beneath, a network of reed-ropes forms a sort of net where trunks and packages are placed. A mattress is spread on top, a purely Spanish mattress, which in no way prevents you from feeling the corners of the luggage piled haphazardly. The passengers arrange themselves as best they can on this new kind of bridge, next to which the gridirons of Saint Lawrence and those of Aniceto Ortega’s opera Guatimotzin are beds of roses, because it was at least possible to turn around on them. What would those philanthropists who would have convicts travel in post-chaises say, on seeing these galleys to which the most innocent people in the world are condemned when they visit Spain?

With these charming vehicles, deprived of any kind of springs, we traversed four Spanish leagues an hour, that is to say five French leagues, a league more than a best-served mail-coach on the finest of roads. To travel faster, English race-horses or coursers would have been required, while the road we followed was broken by the steepest of climbs and downward slopes, always descended rapidly at a triple gallop; it takes all the confidence and skill of the Spanish postilions and drivers not to shatter a vehicle into fifty thousand pieces at the bottom of some precipice: instead of overturning once, we might have overturned at every opportunity.

We were shaken about like mice that are shaken against the walls of a mousetrap, to stun and kill them, and it took all the grave beauty of the landscape to prevent us giving way to melancholy and soreness; but those beautiful hills with their austere lines, their sober and calm colour, gave so much character to a landscape constantly renewed, that the bumping we received from our galleys was more than compensated for. A village, or a former convent built like a fortress, varied the view which was of an oriental simplicity, recalling the distant landscape of Decamps’ Joseph Sold by His Brethren.

Dueñas, located on a hill, looks much like a Turkish cemetery; caves, dug into the solid rock, receive air through small flared turrets like turbans, which possess the deceptively strange appearance of minarets. A church in the Moorish manner completes the illusion. To the left, on the plain, the Castile Canal appears from time to time; its channel is as yet incomplete.

At Venta de Trigueros, we harnessed to our galley a chestnut steed of singular beauty (we had given up on the mules), which fully justified the much-criticised colour of the horse in Eugène Delacroix’s The Justice of Trajan. Genius is always correct; what it invents exists, and nature almost imitates it in its most eccentric fantasies. After crossing a road flanked by embankments and flying buttresses of a rather monumental character, we finally entered Valladolid, slightly bruised, but with our noses intact and our arms still attached to our chest without the aid of those black pins that secure the arms of a new doll. I say nothing about our legs, where numbness pricked us, as if from all the needles manufactured in England, and where the passing feet of a hundred thousand invisible ants swarmed.

We descended at a superb parador, perfectly clean, where we were given two excellent rooms with a balcony opening onto the square, carpets of coloured mats, and walls painted in yellow and apple green tempera. So far, we had found no justification for the reproaches regarding uncleanliness and dilapidation which all travellers heap upon Spanish inns; we had not yet found scorpions in our bed, and the promised insects had failed to appear.

Valladolid is a large city which is almost entirely depopulated; it could house two hundred thousand souls and has barely more than twenty thousand inhabitants. It is a clean, calm, elegant city, where one already senses one’s approach to the Orient. The facade of San Pablo is covered from top to bottom with marvellous sculptures from the early Renaissance. In front of the portal, granite pillars surmounted by heraldic lions are arranged like markers, holding, in all possible poses, the escutcheon of the arms of Castile. Opposite is a palace from the time of Charles V, with an extremely elegant arcaded courtyard and sculpted medallions of rare beauty. Merchants disburse their vile salt and awful tobacco within this architectural pearl. By a happy coincidence, the facade of San Pablo is located in a square, and one can capture a view of it with a daguerreotype camera, which is a thing intensely difficult to perform as regards medieval buildings, they being almost always embedded amidst piled-up houses, and wretched stalls; but the rain, which did not stop falling during the time we remained in Valladolid, prevented any attempt to do so. Twenty minutes of sunshine amidst the showers of rain in Burgos had enabled us to reproduce the two spires of the cathedral and a large piece of the portal in a most clear and distinct manner; but, in Valladolid, we lacked even those twenty minutes, which we regretted all the more as the city abounds in charming architecture. The building where the library is located, which they wish to turn into a museum, is in the purest and most delightful taste; although some of those ingenious restorers who prefer plain stone to bas-relief have shamefully erased its admirable arabesques, enough still remains to make it a masterpiece of elegance. We should point out, to our readers who are architects, an interior balcony indenting the corner of a palace on this same San Pablo square, and forming a mirador (viewpoint) entirely original in taste. The column which joins the two arches is very well cut. This house, we were told, was the one in which that dreadful king Philip II was born. Let me also mention the colossal fragment of the unfinished granite cathedral, by Herrera, in the style of Saint Peter’s in Rome, the construction of which was abandoned in order to create the Escorial, that lugubrious fantasy of Charles V’s melancholy son.

We were shown, in a church which was not in use, a collection of paintings gathered during the suppression of the monasteries, and brought together there by orders from above; this collection proves that the people who pillaged the churches and convents were excellent artists and admirable connoisseurs, since they left behind only these horrible crustaceans, the best of which would not sell for fifteen francs on a bric-a-brac stall. At the Museum, there are some passable paintings, but nothing superior; on the other hand, there are many sculptures in wood, and many ivory Christs, remarkable rather for the grandeur of their proportions and their antiquity, than for any genuine beauty. As regards any other relics, people who head to Spain seeking to buy curiosities return disappointed: not a precious weapon, not a rare edition, not a manuscript, nothing at all.

The Plaza de la Constitucion in Valladolid is very beautiful, and vast in size: it is surrounded by houses supported by large columns of bluish granite, each carved from a single piece of stone to beautiful effect. The palace of the Constitucion, painted apple-green, is decorated with an inscription in honor of innocente Isabella, as the little queen is called here, and with a dial, lit at night like that of the Hotel-de-Ville in Paris, an innovation which seems to greatly delight the inhabitants. Beneath the pillars are established multitudes of tailors, hatters, and shoemakers, the three most flourishing trades in Spain; this is where the main cafes are, and all the population’s movement seems to be focussed on this point. In the rest of the city, you scarcely meet a single passerby, perhaps a criada (maid) going to fetch water, or a peasant driving his donkey before him. This air of solitude is further enhanced by the large surface area of the city, where squares are more numerous than streets. The Campo Grande, next to the Great Gate, is surrounded by fifteen monasteries, there may even be more.

That evening there was a performance, at the theatre, of a play by Manuel Breton de Los Herreros, a dramatic poet highly esteemed in Spain. The piece had the rather odd title: El Pelo de la Desa, which literally means the Hair of the Pasture, a proverbial expression whose meaning is hard to understand, but which corresponds to our saying: ‘The fish-barrel smells always of herring.’ It is about an Aragonese peasant who must marry a well-born girl, and who has the good sense to recognize that he can never become a man of the world. The play’s comedy consists in the perfect imitation of dialect, the Aragonese accent, which is scarcely perceptible to foreigners. The baile nacional, without being as macabre a dance as that of Vittoria, was still quite mediocre. The next day, they performed Hernani or Castilian Honour, by Victor Hugo, translated by Don Eugenio de Ochoa; we were careful not to miss such a feast. The play is rendered, line for line, with scrupulous accuracy, with the exception of a few passages and scenes which had to be cut to suit the demands of the public. The portrait scene is reduced to nothing, because the Spaniards feel it insults them, and consider themselves indirectly ridiculed. There are also a host of cuts in the fifth act. In general, Spaniards are angered when people speak of them in a poetic manner; they claim to have been slandered by Hugo, by Mérimée and by all those, in general, who have written about Spain: yes... slanders, though beautifully done. They deny with all their strength the Spain of the Romancero and the Orientalists, and one of their main pretensions is to be neither poetic nor picturesque, pretensions, alas, all too well justified. The drama was well played: the Ruy Gomez of Valladolid was certainly equal to the one on the Rue de Richelieu, and that is saying something. As for Hernani, the poisonous rebel, his acting would have been most satisfactory were it not for the tiresome whim of his being dressed like a troubadour on a clock-mount. Doña Sol was almost as young as Mademoiselle Mars (Anne Salvetat), without her talent.

The theatre in Valladolid is of quite good design, and, although it is only decorated inside in simple white with decoration en grisaille, the effect is pretty; the decorator had the odd idea of painting window frames on the proscenium walls, adorned with excellent imitations of speckled muslin curtains. These windows give the boxes nearest the stage a singular appearance. The balconies and fronts of the boxes are open, with carved balusters, which allows you to see whether the women have small feet and are well shod, and even whether their ankles are thin, and their stockings neat; which presents no disadvantage to Spanish women, who are almost always irreproachable in that respect. I read, in a charming article by my literary stand-in (since La Presse penetrates even to these barbaric regions) that the balconies in the gallery of the new Opéra-Comique are constructed according to this system.