Théophile Gautier

Travels in Russia (Voyage en Russie, 1858-59, 1861)

Part VIII: Troitsa (The Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius), and Byzantine Art

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

Chapter 18: Troitsa (The Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius)

If, having viewed the main sights, one has a few days leisure in Moscow, an excursion offers itself that one should not fail to accept with alacrity. That is, to visit the monastery of Troitsa. The journey is well worth while, and few regret the undertaking.

It was therefore agreed that we would go to Troitsa, and a Russian friend, who had graciously assumed the responsibility of acting as our guide, took care of the preparations. He engaged a kibitka (sleigh) and sent a relay of horses to the half-way point; for the journey, if one takes to the road early, can be accomplished in half a day, and one can arrive early enough to gain a general idea of the buildings and their situation. We were warned to be ready to leave at three in the morning.

Habitual travelling grants one the ability to wake at a precise time, without persistent prompting from the tinkling chimes of an alarm clock. So I was on my feet, and already furnished with food and a glass of hot tea — the tea is excellent in Moscow — when the kibitka arrived at the front door of the inn. Trying to assess the state of the weather through the double panes of the window, I noted that the indoor thermometer showed fifteen degrees Réaumur (nineteen degrees Centigrade) and the outside minus thirty-one degrees (minus thirty-eight degrees Centigrade). A light wind cooled by the polar ice floes had blown during the night, and brought the glacial resurgence.

Thirty-one degrees of cold, when you think about it, makes even the least chilly nature shiver; fortunately, I had already suffered all the rigours of the Russian winter, and was accustomed to temperatures suited to reindeer and polar bears. However, as I would be exposed to the fresh air for a whole day, I had dressed accordingly: two shirts, two vests, and two pairs of trousers, enough to clothe a second person from head to toe. For the legs and feet woollen stockings, and white felt boots, inside a second pair of fur-lined boots reaching above the knee; for headgear a warm beaver-lined hat; for gloves, a pair of Samoyed mittens of which the thumbs alone were articulated, and, cloaking all, an enormous fur overcoat, its collar rising behind as high as the top of my head to protect my neck, and secured at the front to protect my face. In addition, I wound a long knitted woollen scarf five or six times round my torso, like string knotted round a parcel, so as to preclude any gap in my coat through which air could penetrate. Bundled up, in this manner, I looked like an ambulant sentry-box, and, in the warmth of the room, the layers of clothing seemed to weigh immensely, and overwhelm me; yet, once in the outside air, felt as light as cotton.

The kibitka was waiting, and the impatient horses, lowering their heads and shaking their long manes, chewed the snow. A few words of description apropos the vehicle. A kibitka is a kind of box, which is as much a cabin as a carriage, set on a sled’s frame. It has a door, and a window which one would not dream of closing, since the steam from one’s breath condensing on the window would change to ice, and one would thus find oneself deprived of air, and plunged into frosted darkness. We arranged ourselves as best we could in the depths of the kibitka, packed like sardines from Lorient; because, though there were only three of us, the quantity of clothes with which we were overloaded meant that we occupied the space of six; over our legs, as an additional precaution, travel blankets and a bearskin were thrown, and we departed.

It must have been about four in the morning. In the blue-black sky, the stars shone with vivid scintillations and the sharp clarity that indicates an intense degree of cold; the snow screeched, beneath the steel runners of the kibitka, like glass scratched with a diamond. As for the rest, there was not a breath of air, and one would have said that the wind itself has frozen stiff. One could have taken a walk lit by a candle in one’s hand, without the flame wavering; the wind added markedly to the severe morning chill, changing an inert coldness to an active coldness, and cubes of ice into arrowheads. It was, in short, what towards the end of January is termed fine weather, for Moscow.

Russian coachmen like to travel swiftly, a taste that the horses share. It proves necessary to restrain rather than rouse them. Every departure takes place at full speed, and when one is unused to so dizzying a speed, one fears them having the bit between their teeth. Ours did not deviate from the rule, and galloped wildly amidst the solitude and silence of the Moscow streets, which were lit by a dim glow from the reverberating snow, rather than the fading light of their frozen lanterns. The houses, buildings, and churches sped by rapidly to right and left, their dark silhouettes strangely outlined and enhanced by gleams of white, because no darkness quite extinguishes the silvery sheen of snow. Sometimes the domes of chapels, quickly glimpsed, gave the effect of giant helmets rising above the ramparts of some fantastic fortress; the silence was disturbed only by the night-watch, walking at regulation pace, trailing their iron-shod sticks over the pavement slabs to demonstrate their vigilance.

At the speed we were going, though Moscow is vast, we had soon crossed the city boundary, and the street was replaced by a road. The houses vanished, and the countryside extended vaguely on both sides, whitish under the night sky. It offered a strange sensation, this coursing at great speed through a pale, indefinite landscape, enveloped in a monotonous whiteness, and resembling a flat plain on the moon, while man and beast slept, and without hearing any other noise than the trampling of horses and the sound of the sled runners in the snow. One might have thought one was on an uninhabited globe.

While we were galloping like this, a sequence of thoughts filled my mind, due to one of those internal transitions whose thread Edgar Allan Poe’s Auguste Dupin knew so well how to follow, but which often arouse sudden questions in the reader ignorant of its secret – thoughts of what, of whom? I challenge you to guess – of Robinson Crusoe!

What circumstance could have given rise in my brain to the idea of Robinson Crusoe, on the road from Moscow to Troitsa, between five and six a.m., in thirty degrees of cold, a temperature which scarcely reflected the climate of the island of Juan-Fernández, on which Daniel Defoe’s hero spent many a long and lonely year. A peasant’s hut, built of logs, which took shape for a moment at the edge of the road, had awakened, confusedly, in me the memory of the lodge built by Crusoe at the entrance to his cave; but this fleeting idea would have vanished, and remained unlinked to the present situation in any sensible way, if the snow, as I glanced at it with a distracted eye, had not imperiously recalled that character, close to disappearing into the fog of my vague musings. In the sequel to his adventures (see Defoe’s ‘The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe’, 1719) after his deliverance and return to civilised life, Crusoe makes a long journey, with his little caravan, over the snow-covered plains of Siberia, and is attacked by packs of wolves which put his body as much at risk as when the cannibals had previously landed on his isle.

That is why the idea of Robinson Crusoe came to me, in accordance with that hidden logic readily deducible by an attentive mind. Passing beyond it, to the idea of wolves on the road ahead, was fatal. My thoughts had turned of themselves towards that rather troubling subject given the vast solitude of snow, marked here and there by reddish patches indicating the presence of pine and birch forest. I recalled the most dreadful stories of travellers attacked and devoured by packs of wolves. I put an end to such thoughts, by recalling a tale that Honoré de Balzac once related to me, with that enormous degree of seriousness he brought to all his pleasantries. It was the story of a Lithuanian lord and his wife, travelling from their castle to another at which a ball was taking place. On the path, at the corner of a wood, a pack of wolves lay in wait to ambush the carriage. The horses, urged on by the coachman, and by the dread that those formidable creatures aroused, galloped on frantically, followed by the whole pack whose eyes glowed like embers in the carriage’s shadowy wake. The lord and his lady, more dead than alive, each cowering in their corner, frozen with fear, thought they heard behind them vague sighs, panting breath, and the grinding of jaws; at last, they arrived at the castle whose gate, on closing, sliced two or three wolves in half. The coachman halted by the porch, and when no one came to the door, they turned around, only to see the skeletons of their two lackeys, perfectly stripped of flesh, still clinging to the straps of the carriage in the classic position. ‘Now there were well-trained and dutiful servants,’ exclaimed Balzac, ‘such as we no longer find in France!’

The humour of the story did not, however, prevent me imagining more than one wolf, ravenous as they are in the depths of winter, chasing behind us. We had no weapons, and our only hope of salvation would have lain in the speed of our horses, and the protection of some neighbouring dwelling. All this would have made for a far from cheerful scene; but the tale had proved amusing, and laughter had quenched our worries, and moreover day began to break, the dawn light that does away with chimeras and sends the wild creatures back to their dens. Needless to say, we saw not the slightest trace of even the tail of a wolf.

The night had been studded with stars; but towards morning a mist had risen on the horizon, and the Muscovite dawn arose pale, with weary eyelids, and pallid face. Her nose may have been red, but the epithet ‘rosy-fingered’ that Homer applied to his Greek Aurora was less than applicable here. However, the glow was enough to allow the landscape around us, though not lacking in grandeur, to be seen in all its dreary extent.

The reader may find my descriptions of it somewhat repetitive, but monotony is one of the characteristics of the Russian countryside, at least in the region we were travelling through. On those immense plains, only slightly undulating, one finds no higher hills than those on which the Kremlins of Moscow and Nizhny-Novgorod are built, neither of which exceed Montmartre in height. The snow, which covers these indefinite spaces for four or five months of the year, further adds to their uniformity of appearance, by filling the folds of the ground, and the beds of the watercourses and the valleys they carve. What one sees for hundreds of leagues, is an endless white tablecloth, raised a little, here and there, by the inequalities of the ground it covers and, depending on the obliquity of the sun, sometimes streaked with pink light and bluish shadow; though, when the sky has its ordinary hue, that is to say a leaden grey, the general colour is a matt white, or, to put it better, a dead white. In the more or less near distance, lines of reddish bushes, half emerging from the snow, mark the vast whiteness. Birch woods, and sparsely sown pine trees, show as dark spots here and there, and poles similar to telegraph posts reveal the presence of the road, cleared by the frequent activity of snow ploughs. Near the road, stand izbas made from logs, the cracks stuffed with moss, their roofs, the gables of which are crossed at the top in the form of an X, displaying their sharp lines in rows, and, at the edge of the horizon, villages reveal themselves in shallow silhouettes, each topped with a church’s bulbous bell-towers. Nothing living is visible but flocks of ravens and crows, and sometimes a moujik, bearing wood or some other load to a dwelling in the interior, on his sleigh drawn by small long-haired horses.

Such is the landscape, reproduced till the eye is sated, which reforms around one as one advances, just as one’s view of the sea endlessly renews, ever the same, beyond one’s vessel Although an accidentally picturesque feature is quite rare, one never wearies of gazing at those immense expanses which inspire in one an indefinable melancholy, as does everything that is vast, silent and lonely. Sometimes, despite the speed of the horses, one might think oneself at rest.

We arrived at the relay station, whose name I forget. It was a wooden house, with a courtyard cluttered with telegas (carts) and sleds of quite wretched appearance. In the lower room, moujiks, in tulups shiny with grease, with blond beards, and crimson faces lit by eyes of icy blue, were grouped around a copper urn drinking tea, while others were sleeping on benches near the stove. Some, even more cautious souls, lay on its top.

We were conducted to an upper room, its walls covered with planking, which looked like a firwood-box viewed from within. It was lit by a small double window, and had no other ornament than an image of the ‘Mother of God’, whose halo and garments were of metal, and whose head and hands emerged to reveal that brown tint which the Russians employ in imitation of the Byzantine school, and which grants an age-old appearance to paintings which are quite recent. The Child Jesus was treated in the same manner. A lamp burned before this holy image. These mysteriously tanned faces, which one glimpses amidst a golden or silver carapace, are full of character, and command greater veneration than would paintings more preferable from the point of view of art. There is no cottage so poor that it lacks one of these images, in front of which one never passes without baring one’s head, and which are the object of frequent worship.

A pleasant hothouse temperature reigned in this room, furnished with a table and a few chairs, rendering it comfortable. We removed the fur coats and heavy clothes that weighed us down, and lunched on the provisions brought from Moscow, a lunch washed down with Caravan tea (a blend of black and oolong teas named from the camel caravans that carried it from China to Europe via Russia in the 18th century) brewed in the inn’s samovar. After which, resuming our heavy armour against the barbs of winter, we settled into our kibitka once more, ready to brave, with good cheer, the rigours of the cold.

As one approaches Troitsa the houses become more numerous, and one feels one has reached an important place. Troitsa is indeed the destination for lengthy pilgrimages. Worshippers arrive from all the provinces of the Empire, for Saint Sergius, the founder of this famous convent, is one of the most revered saints of the Greek calendar. The road that leads from Moscow to Troitsa, which we had followed, runs to Yaroslav, and in summer it presents, it is said, a most lively sight; it leads there by way of Ostankino, where a Tatar encampment is to be found, the village of Rostokino, and that of Alekseyevskoye, which still retained until a few years ago the ruins of Tsar Alexis’ castle, and, when winter does not cover them with its coat of snow, one can see amidst the countryside graceful pleasure mansions. The pilgrims, dressed in their armiaks (camel-hair kaftans) and shod with lime bark shoes when they are not walking barefoot out of devotion, follow the sandy road in stages. Families follow, in kibitkas, carrying with them mattresses, pillows, kitchen utensils, and the essential samovar, like nomads on a journey; but at the time of our excursion the road was perfectly empty.

Before arriving at Troitsa, the ground drops a little, probably eroded by some watercourse frozen in winter and covered with snow. On the far side of the ravine, on a broad plateau, the monastery of Saint Sergius rises picturesquely, with the look of a fortress, a huge quadrilateral, surrounded by solid ramparts, their width supporting a covered gallery, pierced by barbicans that sheltered the defenders of the place: so, one might describe this convent, which was attacked on several occasions. Large towers, some square, others hexagonal, occupy the corners and surmount the walls far and near. Some of these towers at their top bear a strongly-projecting machicolated surround, on which oddly bulging roofs rest, topped with lanterns that end in needles.

There are others which carry a second tower, rising behind the first, amidst a ring of pinnacles. The door through which one enters the monastery is set in a square tower in front of which extends a vast square.

Above these ramparts stand, in graceful and picturesque irregularity, the ridges and domes of the buildings that the monastery encloses. The immense refectory, whose walls are squared, and painted with pointed diamond-shaped bosses, occupies the eye, its imposing mass lightened by the bell-tower of an elegant chapel. Nearby are the five bulbous domes of the Church of the Assumption, each topped with a Greek cross; a little further, dominating the skyline, the tall polychrome bell-tower of the Trinity displays its tiered turrets, and lifts to the heavens its cross adorned with chains. Other towers, pinnacles and roofs take shape, confusedly, within the area of the walls, but the eye cannot assign them an exact location, which would require a view from above. Nothing is more charming than the gilded domes and spires, to which the snow adds a few touches of silver, rising from a group of buildings painted in bright colours. It gives one the illusion of gazing at an oriental city.

On the far side of the square is a large hotel more akin to a caravanserai than an inn, designed to receive pilgrims and travellers. That is where we left our carriage, and where, before visiting the monastery, we chose our rooms and ordered dinner. Our lodging-house was not the equal of the Grand Hôtel du Louvre (on the Place du Palais-Royal, opened 1855) or the Hotel Le Meurice (on the Rue de Rivoli, opened 1835) in Paris, but, despite that, the place was quite comfortable, the temperature was spring-like, and the pantry seemed sufficiently well-garnished. Tourists’ laments concerning the dirt and vermin in Russian inns astound me.

Near the monastery door, stalls were established containing small goods and various little curiosities that tourists like to buy as souvenirs. There were children’s toys of primitive simplicity, coloured with amusing barbarity, charming white felt shoes, bordered with pink or blue, that Andalusian feet would scarcely fit, fur-lined mittens, Circassian belts, Tula cutlery nielloed with platinum, models of the cracked bell in Moscow, rosaries, enamel medallions with the effigy of Saint Sergius, metal or wooden crosses adorned with a multitude of miniature figures in Byzantine style interspersed with legends in Slavonic characters, bread from the convent bakery bearing, stamped on the thin crust, scenes from the Old or New Testament, all without counting the piles of those green apples which the Russians seem to love. Some moujiks purple with cold kept these little shops; because here, the women, without being subjected to oriental seclusion, are barely seen outdoors; one rarely encounters them on the street; trade is handled by men, though the merchant as such is a type virtually unknown in Russia. This custom is a remnant of the ancient Asian concern for modesty. On the entrance tower several episodes of the life of Saint Sergius, the great local saint, are painted. Like Saint Roch and Saint Anthony, Saint Sergius has his favourite animal. Neither a dog nor a pig, but a bear in fact, a wild beast well-suited to appearing in the legend of a Russian saint.

While the venerable anchorite was living in solitude, a bear with obviously hostile intentions prowled around his hermitage. One morning, on opening his door, the saint encountered the bear, standing there and growling, its arms extended for a hug which had nothing fraternal about it. Sergius raised his hand and blessed the animal which dropped on all fours, licked his feet and began to follow him with the docility of the most submissive dog. The saint and the bear became the best of companions.

After taking a look at these paintings which if not old, had at least been executed in the ancient style and were of sufficiently Byzantine appearance, we entered the monastery enclosure, which resembles the interior of a fortress and which is indeed one, for Troitsa endured several sieges.

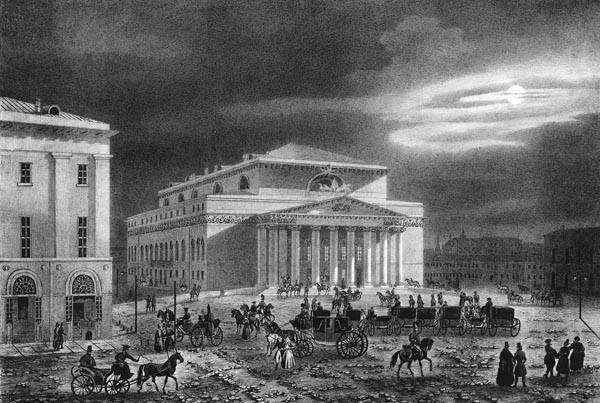

Troitsa - Sergiyeva Lavra, 1800 - 1802

Picryl

A few lines of historical details about Troitsa maybe necessary before moving on to a description of the monuments and treasures its ramparts contain. Saint Sergius lived in a hut in the middle of the vast surrounding forest of Radonezh, currently known as Gorodok (now Radonezh once more), indulging in prayer, fasting and all the austerities of eremitic existence. Near his cabin, he raised a church in honour of the Most Holy Trinity and thereby created a religious centre to which the faithful flocked. Disciples, full of fervour, wished to dwell near the master. To accommodate them, Sergius built a monastery which took the name Troitsa, ‘Trinity’ in Russian, after the name of the church, and he was elected its superior. This took place in 1337. Care for one’s salvation and concern for heavenly things did not prevent Saint Sergius being interested in the events of his time. The love of God did not extinguish in him love for his native soil. He was a patriotic saint, and as such is still the object of great veneration amongst the Russians. It was he who, at the time of the great Mongol invasion, inspired Prince Dmitri Donskoy to take to the plains along the River Don against Manai’s fierce Tartar horde. So that heroic exaltation might be joined with religious exaltation, two monks (Peresvet and Oslyabya), delegated by Sergius, accompanied the prince in battle. The enemy was repulsed (on the Field of Kulikovo, in 1380) and the grateful Dmitri endowed the monastery of Troitsa with great wealth, an example which was followed by all the princes and tsars, among others Ivan the Terrible, one of the convent’s most generous protectors.

In 1393, the Tartars attacked Moscow and carried out razzias (hostile raids) in the Asian manner. Troitsa was already too rich a prey not to excite their greed. The monastery was attacked pillaged, burned, and reduced to a heap of ruins, and when, the devastating storms having ceased, Saint Nikon (Abbot of Radonezh) visited the monastery (in 1422) to initiate its restoration, and recall the dispersed monks, the body of Saint Sergius, in a state of miraculous preservation, was found beneath the rubble.

Troitsa, in times of invasion and trouble, served as a sanctuary for patriotism and a citadel for nationality. The Russians defended themselves there for sixteen months, from 1608 to 1610, against the Poles led by hetman Jan Sapieha. After several fruitless assaults the enemy was forced to lift the siege. Later, (in 1698) the monastery sheltered the young Tsareviches, Ivan and Peter Alexeevitch, fleeing the Streltsy rebellion, or, to speak more correctly, the rebellious ‘Streltsys’ of those regiments. Peter I, the Great, sought refuge there from these same Streltsys, and its recognition by the illustrious but persecuted pair, who subsequently came to power, enriched Troitsa and rendered it a tabernacle of treasures. Since the sixteenth century, Troitsa has escaped being pillaged, though the convent would have offered splendid booty to the French army if it had advanced that far, and if the great fire of Moscow had not decreed its retreat.

Tsars, princes, and boyars, through pure magnanimity or a desire to obtain divine forgiveness, endowed Troitsa with incalculable riches which remain there still. The sceptical Prince Grigory Potemkin, who was none the less devoted to Saint Sergius, offered up sumptuous priestly vestments. Besides these heaps of treasure, Troitsa commanded a hundred thousand peasants, and held immense estates which Catherine II, the Great, secularised, compensating the monastery with rich gifts. Formerly Troitsa housed, in cells, around three hundred monks; today there are scarcely more than a hundred, who sparsely populate the vast solitude of the immense convent.

The Troitsa enclosure, which is almost a city in itself, contains nine churches, or nine cathedrals as the Russians say, the Tsar’s palace, the accommodation for the archimandrite, the chapter house, refectory, library, and treasury, the cells of the brethren, sepulchral chapels, and service buildings of all kinds, regarding which there was no attempt at symmetry, and which rose at the right time, in the right place, like plants growing on some favourable corner of land.

Its aspect is strange, new and, so to speak, disorienting. Nothing is less picturesque than Catholic convents. Melancholy Gothic art with its frail columns, angled arches, hollowed-out trefoils, and slender ascent towards the heavens, inspires a completely different set of ideas. Here, one notes extensive cloisters, bordering, with their arcades darkened by time, a solitary courtyard; and ancient and austere walls, green with moss and washed by the rain, which retain the lichens and soot of centuries. Architectural features of infinite caprice, varying the obligatory theme and creating surprise even within the expected. Greek Orthodox religion, though less picturesque, from the point of view of art, preserve the ancient Byzantine formulae, repeated fearlessly, with a greater concern for orthodoxy than taste. It achieves powerful effects of wealth and splendour, however, and its hieratic barbarity deeply impresses naive imaginations.

It is impossible for the most jaded tourist not to feel astonishment and admiration on seeing, at the end of an avenue of trees, glistening with frost, which offers itself to view as one emerges from the tower’s entrance porch, those varied churches painted in Marie-Louise blue, bright red, and apple green, highlighted in white by the snow, their gold and silver domes rising strangely from amidst the polychrome buildings that support them.

Daylight was beginning to fade when we entered the Trinity Cathedral, in which the shrine of Saint Sergius is to be found. Mysterious shadows further added to the magnificence of the sanctuary. On the interior walls, long rows of saints made dark patches on the gilded panels and took on a kind of strange savage life. They seemed like a procession of sombre figures, silhouetted darkly on the summit of a hill by the rays of a setting sun. In other more obscure corners, the painted figures looked like ghosts gazing from the shadows on whatever was taking place in the church. Touched by some stray shaft of light, here and there, a halo shone like a star in the night sky or some bearded saint’s head gave the appearance of John the Baptist’s head on Herodias’ plate. The iconostasis, a gigantic facade of gold and jewels, rose to the vault amidst umber gleams, and prismatic scintillations. Near the iconostasis, to the right, a brightly-lit structure caught the eye; a series of lamps illuminated this corner, a conflagration of gold, silver and vermeil. It was the shrine of Saint Sergius, the humble anchorite, who rests there in a monument richer than that of any emperor. The tomb is in gilded silver, the canopy in solid silver, supported by four columns of the same metal, a gift from the Tzarina Anna Ioannovna. Around this block of goldsmith’s work over which light pours, moujiks, pilgrims, faithful folk of all kinds, in admiring ecstasy, were praying, making the sign of the cross, and surrendering to the practices of Russian devotion. It formed a scene worthy of Rembrandt. The gleaming tomb cast splashes of light on these kneeling peasants making a skull shine here, a beard glow there, highlighting some profile, while the body below remained bathed in shadow, lost beneath coarse layers of clothing. There were superb faces there, illuminated by fervour and belief.

After contemplating this spectacle so worthy of interest, we examined the iconostasis wherein is embedded the image of Saint Sergius, an image considered miraculous in its effects, and which Tsar Alexis took with him in his wars against Poland, and Peter the Great on his campaigns against Charles XII. One cannot conceive the sheer amount of wealth that faith, devotion, and hope born of remorse has accumulated, in seeking indulgence of the heavens over the centuries, on the wall of this iconostasis, a colossal setting for a true mine-full of gems. The halos of various icons are embossed with diamonds; while sapphires, rubies, emeralds, and topazes form mosaics on the gilded robes of the Madonnas, white and black pearls make patterns there, and where space is lacking, chains of solid gold sealed at the two corners like handles on a chest of drawers, are embedded with diamonds of enormous size. I dare not calculate the value, which certainly exceeds several million francs. Doubtless, a simple Madonna by Raphael is more beautiful than a Greek ‘Mother of God’ thus adorned, but nevertheless this prodigious magnificence, Asian and Byzantine in nature, produces a singular effect.

The Assumption Cathedral, which neighbours that of the Trinity, is built on the same plan as the Kremlin’s Dormition church, the exterior and interior arrangements of which it replicates. Paintings that one might believe created by student contemporaries of Manuel Panselinos, the great Byzantine artist of the eleventh century, cover the walls, and the enormous pillars which support the vault. One might say that the church is entirely clothed in tapestries, because no relief work interrupts its immense frescoes divided into zones and compartments. Sculpture is in no way involved in the ornamentation of religious buildings dedicated to the Greek Orthodox worship: the Eastern Church, which employs so great a profusion of painted images, seems not to admit sculpted ones. It seems to fear the statue as representing a form of idol, although bas-relief is sometimes employed in the decoration of doors, crosses and other elements of worship. I know of no other three-dimensional statues than those which adorn St. Isaac’s Cathedral. This absence of relief and sculpture gives Greek churches a strange and singular character which one fails to fully appreciate at first, but which one ends by comprehending.

In this church are the tombs of Boris Godunov, his wife and two children; these sepulchres resemble Islamic turbas (mausoleums) in style and shape. Religious scruples have banished the artistry that renders the Gothic tombs in western churches so admirable.

Saint Sergius, as founder and patron saint of the monastery, deserved a church of his own on the site where his hermitage once stood. So, there is, within the Troitsa enclosure a chapel of Saint Sergius as rich, as ornate, and as splendid as the sanctuaries of which I have just spoken. Here the miraculous image of the Virgin of Smolensk, called the Hodegetria, ‘She who shows the way’, was to be found. The walls were covered with frescoes from ceiling to floor, and the iconostasis, in niches embossed with gold, revealed the brown heads of Greek saints.

However, night had now completely descended, and whatever zeal one may possess, the profession of tourist cannot be practised in darkness. Hunger gripped us, and we returned to the inn where the pleasant temperature maintained in Russian interiors awaited us. The meal was passable. The sacred cabbage soup, accompanied by meatballs, a suckling pig, and sudak (pikeperch), a fish as peculiar to Russia as sterlet, composed the menu, brightened by a little Crimean white wine, a sort of ‘epileptic coconut juice’ (foaming white; for the origin of the phrase see Henri Murger, Scènes de la Vie de Bohème, 1851) which seeks to counterfeit Champagne, and is not too unpleasant a drink.

After dinner, a few glasses of tea, and a quantity of extremely strong Russian tobacco, smoked in small pipes like those the Chinese employ, occupied us till bedtime.

My sleep, I admit, was undisturbed by those nocturnal creatures whose impure attentions transform the traveller’s bed to a blood-stained battlefield. I am thus deprived of the pleasure of uttering here a pathetic curse against insects, and must reserve for another occasion that quotation from Heinrich Heine: ‘Yes, the worst thing on earth…is the duel with a bug’ (see Heine’s ‘Atta Troll’ Canto XI, last verse). To destroy them it suffices to leave the bedroom window open in thirty degrees or so of frost, and it was winter.

Early the following morning we recommenced our tour of the Troitsa monastery. We visited the churches we had not been able to see the day before, which it is useless to describe in detail, since their interiors are more or less repetitions of one another like a liturgical formula. In some of the exteriors the rococo style is joined, most oddly, to the Byzantine style. It is difficult also to assign their true age to these buildings; what seems old may have been painted the day before, while the traces of time vanish between layers of colour incessantly renewed.

I had a letter, from an influential person in Moscow, for the archimandrite, a handsome fellow with long beard and long hair, and a most majestic visage, whose features recalled those of the Ninevite bulls with human faces. The archimandrite knew no French and, summoning a nun who understood the language, told her in Russian to accompany us on our visit to the treasures and other curiosities of the convent. The nun kissed the hand of the archimandrite, and stood in silence, waiting till the guard arrived with the keys. She was one of those figures which it is impossible to forget, and which emerge like a dream from the trivialities of life. She was wearing a kind of cylindrical headdress, similar to the diadem of certain Mithraic deities, and such as are worn by priests and monks. Long crepe beardlike strands descended in floating fragments; they fell on a loose black garment, of a fabric similar to that from which lawyer’s robes are made. Her face, of an ascetic paleness, in which yellow waxy tones lay beneath the fineness of the skin, was of perfect regularity. Her eyes, surrounded by large dark marks, revealed, whenever she raised her eyelids, pupils of a strange blue tint, while her whole person, though engulfed by, and almost lost in, that floating bag of black cheesecloth, betrayed the rarest distinction. She dragged its folds through the long corridors of the monastery with the air of one manoeuvring the train of a dress at some court ceremony. The grace of a former worldly woman, which she tried to hide out of Christian humility, reappeared in spite of herself. On seeing her, the most prosaic imagination could not help but envisage her as a character in a novel. What suffering, what despair, what catastrophe in love could have brought her there? She reminded me of Antoinette, Duchesse de Langeais, in Balzac’s Histoire des Treize, discovered by Armand de Montriveau hiding beneath a Carmelite habit, in the depths of an Andalusian convent.

We arrived at the treasury where we were shown, as a most precious item, a goblet carved from wood and some crude priestly vestments. The nun explained that this humble wooden vessel was the ciborium that Saint Sergius used in his holy offices, while wearing these chasubles of wretched cloth, which rendered them priceless relics. She spoke the purest French, without a trace of accent, as if it was her native language. With the most detached manner in the world, without scepticism and yet without naivety, she told us, with the air of a historian, some marvellous legend I no longer recall, relating to these objects, her lips parted in a faint smile which revealed teeth brighter than all the oriental pearls in the treasury, sparklingly white teeth leaving an imperishable impression on the memory, akin to Berenice’s teeth in Edgar Allan Poe’s short story of that name.

Those gleaming teeth, in a face bruised by sorrow and austerity, restored youthfulness to her. The nun, who at first sight had seemed to me to be about thirty-seven or thirty-eight years old, appeared now to be no more than twenty-five. But it was only a glimpse of youth, so to speak. Having appreciated, with feminine delicacy, our respectful, but lively admiration, she again took on the death-like air that suited her apparel.

All the cupboards were opened for us, and we were able to view bibles, gospels, and books of liturgy, with gemmed silver-gilt covers encrusted with onyx, sardonyx, agate, chrysoberyl, aquamarine, lapis lazuli, malachite, and turquoise, and with gold or silver clasps, ancient cameos embedded in their surfaces; gold ciboria encircled by diamonds; crosses adorned with emeralds and rubies; rings with sapphire settings; vessels and candlesticks of silver; brocade dalmatics embroidered with jewelled flowers and legends in Old Slavonic written in pearls; enamelled incense-burners; triptychs historiated with countless figures; images of Madonnas and saints, and pieces of goldsmith’s work studded with cabochons — like to the treasures of some Christianized Harun-al-Rashid.

As we were about to exit, dazed by wonders, our eyelids flickering, our eyes filled with crazed points of light, the nun pointed out to us a row of boxes, on one shelf of a cupboard which had hitherto escaped our attention, and seemed to offer nothing special. She plunged her thin, narrow patrician hand therein, saying: ‘These are pearls. No one knew what to do with them, so they were left here. There are eight full measures in total.’

Chapter 19: Byzantine Art

Realising, from various comments of ours, that we were no strangers to art, the nun, having shown us the treasury, thought that a sight of the convent’s workshops might interest us as much as these heaps of gold, diamonds and pearls, and led us, by wide corridors interspersed with stairways, to the rooms where the artist-monks and their students laboured.

Byzantine art is in every way unique, and bears little resemblance to the manner in which the phrase is understood by the people of Western Europe, or those who follow the Latin religion. It is a hieratic art, priestly, and immutable; nothing or almost nothing is left to the imagination or invention of the artist. Its formulae are as precise as dogma. There is thus in this school, neither progress, nor decadence, nor age, so to speak. A fresco or painting completed twenty years ago is indistinguishable from one hundreds of years old. As it was in the sixth, eighth, or tenth century, such is Byzantine art still; I use the term for lack of one more fitting, as one uses the word Gothic, which is understood by all, though not possessing an exact meaning.

It is obvious to any man accustomed to the art of painting that this style derives from some source other than the Latin style, that it owes nothing to the Italian school, that it endures as if the Renaissance never happened, and that Rome is not the metropolis in which its ideal resides. It exists alone, without borrowings, without development, since it has, from the very first, found its essential form, open to criticism from the artistic viewpoint, but wonderfully suited to the function it performs. Yet, where is the home of this tradition one wonders, a tradition so carefully preserved? Whence does this uniform style derive which has survived the ages and suffered little or no alteration however diverse the milieux? What masters did they obey, all those unknown artists whose brushes adorned the churches of the Greek Orthodox with such a multitude of figures that their enumeration, if it were possible, would exceed the sum of the most formidable army?

A curious and learned introduction by Adolphe Didron, to a Byzantine manuscript, The Guide to Greek and Latin Christian Iconography (Manuel d’Iconographie Chrétiennne Grecque et Latine, 1845), translated by Paul Durand, for the most part answers the questions we have just asked. The editor of this guide to painting is a certain Dionysius, a monk of Fourna in Agrapha, and a great admirer of the celebrated Manuel Panselinos of Thessaloniki, who is the Raphael it seems of Byzantine art, some of whose frescoes can still be seen in the major church (the Protaton) of Karyes, on Mount Athos. In a short preface, preceded by an invocation ‘To Mary, Mother of God, ever virgin,’ master Dionysius of Agrapha states the aim of his book thus. ‘This art of painting, which, from childhood, cost me so great an effort to learn, in Thessaloniki, I wish to propagate for the benefit of those who also desire to practice it, and I explain, in this work, all the measurements, the characteristics of the figures, and the colours of the flesh and ornamentation with great accuracy. Furthermore, I wish to explain the natural dimensions, the details applicable to each subject, the various preparations of varnish, glue, plaster and gold, and the way to paint on walls with the utmost perfection. I also indicate the whole sequence of the Old and the New Testament; the manner of representing the natural facts and miracles of the Bible; and at the same time the Lord’s parables, legends, and epigraphs appropriate to each prophet; also, the names and facial characteristics of the apostles and principal saints; their martyrdoms, and a number of their miracles, according to the order of the calendar. I say how churches are painted, and I provide other information necessary to the art of painting, as can be seen in the list of contents. I collected all this material with great trouble and care, assisted by my student, Master Cyril of Chios, who edited all this with careful attention. Pray for us then, all of you, so that the Lord delivers us from our fear of being condemned as poor servants.’

This manuscript, a true manual of Christian iconography and pictorial technique, dates, according to the monks of Mount Athos, to the tenth century. It is not so old as that, in fact, only dating from the fifteenth; but that matters little, since he is recording ancient formulae and archaic methods. It still serves as a guide today, and, as Adolphe Didron recounts in his trip to the Holy Mountain (‘Agion Oros’, Mount Athos), where he visits Father Macarios, the finest Hagiorite painter after Father Joasaph, ‘this bible of his art was spread open in the middle of the workshop, and two of his youngest students were alternately reading it out loud as the rest were painting while listening to this reading.’

The traveller wished to buy this manuscript, which the artist refused to surrender at any price, since without the book he would not have been able to continue painting, but of which he allowed a copy to be made. The manuscript contained the secrets of Byzantine painting, and allowed the learned tourist, who had recently visited the churches of Athens, Salamis, Trikala, Kalabaka, and Larissa, and the monasteries of Meteora, Saint Varlaam, Hagia Sophia, Thessaloniki, Mystras (Pantanassa), and Argos, to comprehend why he found everywhere the same profusion of painted decoration, everywhere the same composition, costumes, ages, and attitudes of the sacred figures. ‘It as if,’ he exclaims, surprised at this uniformity, ‘a single thought, animating a hundred brushes simultaneously, created all the paintings of Greece.’

A comment, which could be said every bit as justly when standing before the frescoes which decorate most Russian churches.

‘The workshop where these paintings are prepared’, the traveller continues, ‘and where these Byzantine artists are trained, is Mount Athos; this is truly the Italy of the Eastern Church. Mount Athos, this province of monks, contains twenty large monasteries which are so many small towns, ten villages, two hundred and fifty isolated cells, and a hundred and fifty hermitages. The smallest of the monasteries contains six churches or chapels, and the largest thirty-three; in all, two hundred and eighty-eight. The villages or sketes (monastic settlements) contain two hundred and twenty-five chapels and ten churches. Each cell has its chapel, and each hermitage its oratory. In Karyes, the capital of Mount Athos, one finds what might be called the cathedral of the whole mountain, which the Caloyers (monks following the rule of St. Basil) name the Protaton, the metropolis. From the summit of the eastern peak which terminates the peninsula, rises an isolated church dedicated to the Metamorphosis, or Transfiguration, of the Saviour. Thus, Mount Athos houses nine hundred and thirty-five churches, chapels or oratories.

Almost all of these are frescoed and filled with paintings on wood. Most of the refectories, in the great monasteries, are also covered with wall paintings.

Here is a rich museum of religious art indeed. The student-painter possesses no lack of subjects for study or examples to reproduce, for the merit of the artist of the Byzantine school does not lie, as in other schools, in invention, imagination, or originality, but in tracing the consecrated models in the most faithful manner. The contours, the proportions of the figures are fixed in advance. Nature is never consulted, tradition indicates the colour of the beard and the hair, whether long or short, the tint of the clothing, the number, direction, and thickness of the folds in garments. For the long-robed saints, the folds are invariably parted above and below the knee. In Greece,’ writes Adolphe Didron, ‘the artist is the slave of the theologian. His work, which his successors will copy, itself copies that of the painters who preceded him. The Greek artist is as enslaved by tradition as the creature by its instincts. He creates figures as the swallow does its nest or the bee its waxen cell. The execution alone is his; the invention and idea belong to the Fathers, to theologians, to the Orthodox Church. Time and place mean nothing to Greek art; the eighteenth-century painter in the Morea continues to imitate the Venetian painter of the tenth century, who in turn imitated some painter on Mount Athos of the fifth or sixth century. One finds in the Church of the Metamorphosis in Athens, in the Hecatompylos of Mystras, in the Panagia painted by Saint Luke, that Saint John Chrysostom of the Baptistery of St. Mark’s, in Venice.’

Adolphe Didron had the pleasure of meeting, on Mount Athos, in the Monastery of Esphigmenou, the first one that he entered, a painter from Karyes, the monk Joasaph, who was paintings murals on the porch, or narthex, which precedes the nave of the church. He was assisted in his work by his brother, two students, the first of whom was a deacon, and by two apprentices. The subject he was drawing on the fresh plaster applied to the wall was Christ assigning his apostles the task of evangelising and baptising the world, an important subject — involving twelve figures of almost natural size. He sketched the figures without halting, with a sure hand, with only his memory as his cartoon or model. While he was working in this way, the students filled with the designated pigments the contours of the figures and the draperies, and gilded the nimbuses around the heads on which they wrote the letters of the inscriptions which the master dictated to them while continuing with his work. The young apprentices were grinding and watering down the pigments. These frescoes, the traveller assures us, executed with such certainty and alacrity, were of greater value than the paintings of our second or third-rate painters, in the religious genre; and when he expressed surprise at Father Joasaph’s talent and knowledge, he who had found inscriptions so appropriate for each character, implying vast erudition, the monk replied, humbly, that it was not so difficult as one might assume, and that with the help of the Guide and a little practice, anyone might execute the same.

The much-to-be-regretted Dominique Papety exhibited at the Salon of 1847 a charming little painting of ‘Caloyer Monks Decorating a Chapel, in the Monastery of Iviron (Karyes) on Mount Athos, with Frescoes.’

Though I had not as yet made the trip to Russia; this neo-Byzantine art, of which I had been able to view some isolated fragments, already interested me, and Papety’s painting, besides its artistic merit, excited and satisfied my curiosity by presenting the living artists at work, artists whose paintings seemed to date back to the time of the Greek emperors. I said as much in my report on the exhibition: ‘There they both are (the Caloyer monks), standing before the areas of the curved wall of the half-dome that they are painting. The lineaments of the saints they seek to illuminate are outlined in red on the fresh area that awaits their attention. These outlines have an archaic stiffness that might make one think them created in some remote era. In between them, on a kind of pedestal table, lie the tools and colours of the artists. On the left, a trestle supports a trough containing lime-mortar and powdered marble, along with the trowel needed for their application.’

To his offering, the painter had added watercolours representing frescoes by Manuel Panselinos, of which he had made a copy in the church of the Monastery of Agia Lavra. They represented saints of the Greek calendar, grand and proud in appearance, saints of the warrior type.

I too, like Papety and Didron, was about to see the work of artist-monks like those of Mount Athos, religiously following the teachings of the Guide; a living school of Byzantines, the past at work through the hands of the present, a rare and curious thing, indeed.

Half a dozen monks of various ages were in the process of painting a large, well-lit room, with bare walls. The air of priestly gravity, and the pious care, with which one of them executed his work, a handsome man with a black beard and swarthy face, who was completing a ‘Mother of God’, was most striking. It made me think of that fine painting by Jules-Claude Ziegler: Saint Luke painting the portrait of the Virgin. A religious feeling obviously preoccupied him more than his art: he painted as one officiates. His ‘Mother of God’ could have been placed on the easel of that apostle, seeming so severely archaic, and confined within its rigid sacramental outline. One would have thought her a Byzantine empress, gazing on one with such serious majesty from the depths of her large, black, fixed eyes. The areas due to be covered by silver or gold plating, had been as carefully done as if they were still to remain visible.

Other more or less advanced paintings, representing Greek saints, and among others Saint Sergius, the patron saint of the monastery, were being completed beneath the labouring hands of the artist-monks. These paintings, intended to serve as icons in chapels or private residences, were on panels coated with gypsum, according to the processes recommended by Master Dionysius of Agrapha, and were a little darkened; nothing enabled one to distinguish them from like paintings of the fifteenth or even the twelfth century. Here were the same stiff, constrained poses, the same hieratic gestures, the same regular pattern of folds, the same fawn and bistre colour of the flesh, the exact doctrine of Mount Athos. The process used was egg-water or tempera, applied then varnished. Halos and ornamentation intended to be gilded formed slight projections, to better catch the light. The ancient masters of Thessaloniki, if they had returned to the world, would have been satisfied with the students of Troitsa.

But no tradition today can be faithfully maintained. Among the stubborn cultists of the old formula, there appears from time to time, another follower less conscientiousness and constrained. A new spirit introduces itself into the old mould, through some fissure. The very artists, amidst our epoch, who desire to follow the way of the Athonite painters, and render the Byzantine style immutable, cannot help but experience our modern paintings where freedom of invention is combined with the study of nature. It is difficult to close one’s eyes forever, and even in Troitsa, a new spirit had penetrated. In the metopes of the Parthenon we distinguish two styles, one archaic and the other modern. The majority of the monks complied with the rules; a few younger ones had abandoned egg-water for oils, and, while maintaining their figures in the prescribed attitude, and immemorial pattern, allowed themselves to give heads and hands more realistic tones, a less conventional colour, and model the planes and study the use of relief. They had created most human and attractive, and less theocratically fierce saints; they chose not to apply to the chin of the patriarchs and solitaries that junciform (reed-like) beard the Guide recommends. Their images approach painting, without, according to us, having merited it.

This more suave and likeable style has no shortage of supporters, and one can view examples in several modern Russian churches; but, for myself, I much prefer the old method, which is idealistic, religious, and decorative, and displays, to its credit, forms and colours beyond vulgar reality. That symbolic manner of presenting the idea by means of figures defined in advance, like some sacred writing whose characters it is not permitted to alter, seems to me wonderfully suited to the decoration of the sanctuary. In its rigidity even, it still leaves room for a great artist to affirm, by bold execution, the grandeur of the style, and its nobility of outline.

Moreover, I do not think the attempt to humanise Byzantine art succeeds. In Russia there is a school of Romantic writers, enamoured, like ours, of local colour, who defend, with scholarly theories and enlightened criticism, the old style of Mount Athos, because of its ancient and religious character, its deep sense of conviction, and its absolute and original uniqueness, amidst the products of Italian, Spanish, Flemish, and French art. One can gain a fair idea of these polemics by recalling the passionate defence of Gothic architecture, and the diatribes against Greek architecture being applied to religious buildings, involving comparisons between Notre-Dame de Paris and the church of La Madeleine, which were the delights of my youth from 1830 to 1833. There is in every country an era of false Classicism, a species of learned barbarism, in which its people fail to comprehend their native beauties any longer, misunderstand their own character, deny their own antiquities and costume, and seek to demolish, with a view to achieving an insipid ideal of regularity, their most wondrous national buildings. Our eighteenth century, otherwise so great, would have gladly razed the Gothic cathedrals as being monuments to bad taste. The baroque portal of Saint-Gervais, in Paris, by Salomon de Brosse, was genuinely preferred to the prodigious facades of the cathedrals of Strasbourg, Chartres and Reims.

Our nun appeared to regard these Madonnas in fresh colours not with disdain exactly, since, after all, they represented a sacred image worthy of adoration, but with far less admiration and respect. She halted longer in front of the easels where the artists were employing the ancient method. Despite my preference for the style, I must confess that, in my opinion, some aficionados take their passion for old Byzantine paintings a little too far. By dint of seeking the naive, the primordial, the sacred, the mystical, they display enthusiasm for darkened and worm-eaten panels in which one vaguely discerns crude figures, of extravagant design and impossible colouring. Alongside these images, the most barbarous Christ of Giovanni Cimabue would seem as if painted by Carle van Loo or François Boucher. Some of these paintings date, it is claimed, to the fifth or even the fourth century. I can understand that one might seek them out as archaic curiosities, but I find it strange that they are admired from the point of view of art. I was shown some of them during my trip to Russia, but admit that I failed to discover in them the beauties which so charmed their owners. In a sanctuary, they may be venerated for providing an ancient testimony to the faith of their creators, but they have no place in a gallery, unless it is one within a museum.

Apart from this Byzantine art whose Rome is on Mount Athos, there has not as yet been any Russian art to speak of. The artists, few in number moreover, that Russia has produced do not constitute a school: they travel to complete their studies in Italy, and their paintings have nothing particularly national in flavour about them. The most famous of their artists, and the best known in the West, is Karl Bryullov, whose vast canvas entitled The Last Day of Pompeii produced a great effect at the Salon of 1824. Bryullov painted, on the ceiling of the dome of Saint-Isaac, a large Apotheosis in which he demonstrated a notable understanding of composition and perspective, in a style somewhat reminiscent of decorative painting as it was practised towards the end of the eighteenth century. The artist, who possessed a fine pale face, Romantic and Byronic, and flowing blond hair, took pleasure in self-portraiture, and France has several representations of his features, made at various times, less or more ravaged by time, but always handsome and of a fatal beauty. These portraits, made with verve, and free caprice, seem to us the best pieces by that artist. A very popular name in St. Petersburg is that of Alexandre Ivanov, who, employed for many years in the creation of a mysterious masterpiece (The Appearance of Christ to the People, 1837-57), has granted Russia the expectation and hope of a great painter. But that is a separate matter, which would lead me too far from my subject. Is this as much as to say that Russia will never find a place among the schools of painting? I believe that it will happen when her art frees itself from the imitation of foreign works, and her painters, instead of seeking to copy the Italian models, choose to look around them and draw inspiration from nature, and from the extremely varied and characteristic types within this immense empire, which begins at the borders of Prussia and ends at those of China. My encounter with the group of young artists who constitute the ‘Friday’ society permits me to believe in the imminent realisation of this goal.

Preceded, as before, by the nun, draped in her long black garments, we entered a perfectly equipped photographic laboratory, in which Félix Nadar would feel at home. To pass from Mount Athos to the Boulevard des Capucines (Nadar’s studio was at number 35), was rather an abrupt transition! To leave behind those monks painting Panagias (portraits of the Virgin) on gold backgrounds, in order to visit others coating glass plates with collodion is one of these tricks that civilisation plays on you, at a moment one least expects. The view of a cannon aimed at me would not have surprised me more than the yellow brass lens directed by chance towards me. The evidence was undeniable. The monks of Troitsa, the disciples of Saint Sergius, produced views of their monastery, images most successfully achieved. They possess the best equipment, know of the latest methods, and pursue their object in a chamber the window panes of which are dyed yellow, a colour which avoids over-exposure. I bought a view of the monastery, a view that I still possess, and which has not faded too badly.

During his trip to Russia, the Marquis de Custine complained of not being allowed to visit the library of Troitsa. I found no difficulty in being admitted and saw what a traveller can see of a library in half an hour, the spines of well-bound books, stored neatly on cabinet shelves. Besides works of theology, bibles, works of the Fathers of the Church, scholastic treatises, gospels, and liturgical books in Greek, Latin, and Slavonic, I noticed, during my swift inspection, many books in French of the last century, and the Great Century (the seventeenth, when France became the dominant European power). I also took a look at the immense refectory, terminating in a very delicately worked grille, allowing the gold background of an iconostasis to gleam through its arabesques of iron; for the refectory adjoins a chapel, so that the soul may acquire nourishment like the body. Our tour was over, and the nun led us to the archimandrite again, so we might take our leave of him.

Before entering the apartment, the habits of a worldly woman prevailing over the prescriptions of convent life, she turned to us and, in a small gesture of farewell, granted us, as a queen might have done from the steps of her throne, a weak, languishing, and graceful smile, amidst which shone like white lightning, her gleaming teeth preferable to all Troitsa’s pearls. Then, in a sudden reversal as if resuming the veil, she reverted to her death-like face, her spectral physiognomy denoting her renunciation of the world and, with a ghostly movement, knelt before the archimandrite, whose hand she kissed politely, as if it were the communion dish, or a sacred relic. After which, she rose, and returned like a figure in dream to the mysterious depths of the convent, leaving me with an indelible memory of her brief appearance.

There was nothing left for us to view in Troitsa, and we returned to the inn to tell our driver to prepare our sled for departure. The horses once harnessed to the kibitka by a system of ropes, the coachman seated on a narrow folding-seat padded with a sheepskin, and ourselves warmly installed under our bearskin-cover, the bill paid, and tips added, there was nothing left but to execute the fantasia of departure at the gallop. A slight click of the moujik’s tongue made each of our team adopt the look of that furious horse carrying Mazeppa bound on his back (see Byron’s poem, ‘Mazeppa: IX’), and it was not till the far side of the hill dominated by Troitsa, whose domes and towers could still be seen, that the brave little creatures resigned themselves to a reasonable pace. I need not describe the road from Troitsa to Moscow, having described its course from Moscow to Troitsa, the only difference being that the objects in view presented themselves from the opposite direction.

That same evening, we returned to Moscow, well enough disposed to attend a masked ball which was being held that night, and tickets to which we found at the hotel. In front of the door, despite the intense cold, sleighs and carriages were parked the lanterns of which shone like icy stars. A warm blaze of light burst from the windows of the building where the ball was taking place, and made, with the bluish light of the moon, one of these contrasts that dioramas and stereoscopic views seek to incorporate. The vestibule crossed, we entered a vast room in the rectangular form of a playing card, framed by large columns borne on a wide stylobate (platform) which formed a terrace around the floor itself, to which one descended by a stairway. This arrangement seemed sensible to me, and it should be imitated in France where a room is intended for partying. It allows those not taking an active part in the pleasures of the ball to over-look the dancers, without obstructing them, and to enjoy, at their ease, the spectacle offered by the lively and teeming crowd. This raised floor staged and grouped the figures in a more picturesque, more luxurious, more theatrical way. Nothing is as unpleasant as a crowd all on the same level. This is what makes popular festivities so inferior to the effect of the Opéra balls, with their triple row of boxes filled with ‘masks’ forming garlands, and their troops of ‘stevedores’ (in the costume created by the designer Paul Gavarni, mimicking that of dockers), ‘apprentices’, Pierrettes, ‘babyish dolls’ and ‘savages’, ascending and descending the stairs. The decoration of the room was very simple, yet produced no less of an effect as regards gaiety, elegance and richness. Everything was white, the walls, ceiling, and columns all white and enhanced by a few sober gold threads on the mouldings. The columns, stuccoed and polished, could have been mistaken for marble, and the light flowed over them in long bright waves. On the cornices, candles in holders exposed the entablature of the portico, and maintained the overall brightness. Amidst all this whiteness, the lighting mimicked the vividness of the most brightly illuminated Italian day.

Movement and clarity are surely elements of joy; but for a party to attain its full brio, noise must be added to it; noise, the breath and song of life. The crowd, though quite dense, was silent. A faint whisper like a light frisson trembled about the groups, and added a low bass to the orchestra’s fanfares. Russians are silent in their pleasures, and when one has been deafened by the triumphant bacchanal of an Opéra night, one is surprised by their phlegmatism and taciturnity. No doubt, they were enjoying it all internally, without seeming to do so on the outside. There were dominoes, a few ‘masks’, military men in uniform, civilians in evening dress, a few Lezgins, Circassians, and Tartars, young officers with wasp waists, in costume, but none in traditional clothes which might be noted as belonging to the country. Russia has not yet produced its own characteristic mask. The women, as usual, were there in small numbers, and I had to search for them at the ball. As far as I was able to judge, what we call the demi-monde in France was only represented there by Frenchwomen imported from the Jardin Mabille in Paris, and by German and Swedish women, sometimes of a rare beauty. It may well be that a female Russian element is also involved, but it is not easy for the foreigner to identify it as such; I simply note the observation for what it is worth.

Despite some timid attempts at the cancan, again imported from Paris, the party languished a little and bursts of brassy music failed to add much warmth. They were waiting for the Gypsies to enter, for the ball was now interrupted by a concert. When the gypsy singers appeared on stage, a huge sigh of satisfaction rose from every breast. At last, some fun! The real show began! The Russians have a passion for Gypsies, and their nostalgically exotic songs which set one dreaming of a life of freedom amidst primeval Nature, far from all constraint and every divine or human law. That passion, I share, and indulge it to the point of delirium. So, I jostled in order to be near the platform on which the musicians stood.

There were five or six wild-looking haggard young girls, in that state of alarm bright light induces in furtive and vagrant nocturnal creatures They looked like deer suddenly driven from some forest clearing into a living room. Their costume was nothing remarkable; to appear at the concert, they had been obliged to abandon their characteristic dress and make ‘a fashionable toilette’. Thus, they possessed the air of badly-dressed chambermaids. But the odd flutter of the eyelashes, and a wild dark glance hovering vaguely over the audience, sufficed to display their innate character once more.

The music started. The songs were strange, full of melancholic sweetness or mad gaiety, embroidered with endless flourishes like those of a bird which listens to its own warbling and, self-intoxicated, sighs with regret for a previous bright existence, then resumes its carefree, joyful, mood of freedom, while mocking everything, even lost happiness, provided that it remains at liberty; the music, interspersed with stamping and wild cries, made to accompany those nocturnal dances that leave, what we call ‘fairy circles’ in the grassy glades, was akin to a savage version of some work by Weber, Chopin or Liszt. Sometimes the theme was borrowed from a vulgar melody dragged out on the piano, but so smothered in lengthened chords, trills, ornamentations, and caprices, that the originality of the variations made one forget the banality of the motif. The marvellous Variations on the Carnival of Venice, by Paganini (Op. 10) may give some idea of those delicate musical arabesques of silk, gold and pearls, embroidered on a background of coarse fabric. A male Gypsy, a sort of comic character with a fierce look, as swarthy as an Indian, and reminiscent of those bohemian types represented so characteristically by Théodore Valério in his ethnographic watercolours, accompanied the women’s singing by sounding a large rebec placed between his legs, which he played in the manner of oriental musicians; another tall fellow exerted himself on stage, dancing, stamping his feet, plucking the strings of a guitar, marking the rhythm on the wood of the instrument with the palm of his hand, making strange grimaces, and from time to time yielding an unexpected cry. The whole troupe were graceful, comical, lively.

The enthusiasm of the audience, crowded around the platform was indescribable; they burst into applause, shouted, nodded their heads, and gave forth cries of admiration, while repeating the refrains. These songs, of a mysterious strangeness, have a true incantatory power; they induce dizziness and delirium, and bring about the most incomprehensible state of mind. Listening to them, you feel a fatal desire to abandon civilisation forever and run through the woods in the company of one of those witches with a complexion as darkly-tinted as a cigar, and eyes like blazing coals. Such songs, so enchantingly seductive, are indeed the very voice of nature, noted in solitude, and captured in flight. That is why they deeply trouble all on whom the complex mechanism of human society weighs so heavily.

Still spellbound by the melody, I wandered dreamily amidst the masked ball, my mind a thousand miles away. I was thinking of a gitana (a gypsy girl) from the Albaicín neighbourhood in Granada, who had sung copias (ballad verses) to me, to a tune that strongly resembled one of those I had just heard, the words of which I was seeking to retrieve from some remote corner of my brain, when I felt myself seized suddenly by the arm and heard in my ear, spoken in the shrill, false, bright tone of one of those dubious females who affect a domino mask wishing to start an intrigue, the sacramental words: ‘I know you.’ In Paris, nothing would have seemed more natural. For a long time now, I have been visible at first performances, on the boulevards, and in art galleries, so that I am as well-known there as if I were famous. But in Moscow, this recognition at a masked ball seemed like an affront to my privacy.

The domino, asked to prove her assertion, whispered my name into the beard hanging from her mask, pronouncing it fairly accurately, and in a sweet little Russian accent which the attempt to disguise the voice did not prevent me from penetrating. A conversation commenced which confirmed that, even if this Moscow domino had never met me before this ball, she at least knew my works perfectly. It is difficult for an author who has a few verses from his poems, and a few lines of his prose, quoted at him so far from the Boulevard des Italians, not to be a little puffed up, on smelling that incense, the most delightful of all to a writer’s nostrils. In order to save my self-esteem from her designs upon it, I was obliged to tell myself that Russians read a great deal, and the most minor of French authors meet with a wider hearing in Saint Petersburg and Moscow than in Paris itself. However, to return the compliment, I sought to behave gallantly, and respond to her quotations by paying her my attentions, a difficult thing as regards a domino hidden by a satin sack, a cap sloping over her forehead, and a beard as long as that of a hermit. The only thing visible was a small, rather slender hand, tightly-gloved in black. The mystery was too great, and it required too great an expense of imagination on my part for me to prove amiable. I also have a defect of character which restrains me from precipitating myself too ardently into adventures at masked balls. I readily assume that behind every disguise lies ugliness rather than beauty. That vile-looking piece of black silk, with a snub goatish profile, slant eyes, and a goatee beard, seemed to me a mould for the face it covered, and I was at pains to remove it. When masked, the very women whose assured youth and notorious beauty are known to us sometimes arouses suspicion. I am of course only speaking of the full mask. The little black velvet excrescence, our ancestors called a touret de nez (nose-bridge), which great ladies wore when out for a walk, allows the mouth and a pearly smile to be seen, along with the noble contours of chin and cheek, and highlights, with its intense blackness, the rosy freshness of the complexion. It allows one to judge of a woman’s beauty without it being wholly revealed. It represents a modest flirtatiousness, and not a troubling mystery. The worst one risks is discovering a Roxelana nose (an upturned nose, like that of Roxelana, the consort of Suleiman the Magnificent) instead of the Greek nose of which one had dreamed. One can easily console oneself regarding such a misfortune. But the hermetically-sealed domino, when removed at the trysting hour, may bring a sinister discovery that leaves the enthusiastic lover with a most embarrassed countenance. That is why, after two or three turns around the ballroom floor, I returned the mysterious lady to the group she indicated. So ended my adventure at the Moscow masked ball.

— ‘What! Is that all? my readers may say. ‘You are hiding something out of modesty. The domino having left the ball will have directed you to a mysterious carriage and had you mount it, and seat yourself next to her. Then the lady will have tied her lace handkerchief about your face, saying that love must go blindfolded, and, taking you by the hand when the carriage halted, she will have made you follow her down lengthy corridors, such that when she returned you the use of your eyes, you found yourself in her splendidly lit boudoir. The lady will have doffed her mask and shed her domino, as a gleaming butterfly emerges from its darkened chrysalis; she will have smiled at you, seemingly enjoying your wonder. Come, tell us if she was blonde or brunette, if she had a little mole at the corner of her mouth, so we might recognise her, if we encounter her in Paris, in society. We hope you maintained the honour of France abroad, and showed yourself to be tender, gallant, spirited, varied, and passionate, in sum worthy of the situation. — An adventure, at a masked ball in Moscow! — A fine tale, of which you fail to boast, you who are customarily so verbose when it comes to describing buildings, paintings and landscapes.’

Am I to be taken for some worn-out Don Juan, some retired Valmont (see the epistolary novel by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos: ‘Les Liaisons Dangereux’)? Nothing else occurred. The intrigue ended there, and after having taken a glass of tea with an infusion of Bordeaux wine, I returned to my sleigh, which returned me to the hotel on the Rue des Vieilles-Gazettes (Gazetny Pereulok) in a few minutes.

My day had been a full one: a morning at the monastery, an evening at the ball, the nun, the domino, Byzantine painting, and the Gypsies; my sleep was well-deserved.

When travelling one senses the value of time more deeply than usual. One is present for a few weeks, or a few months at most, in a country to which one may never return; a thousand curious things, which one will never see again, solicit the attention. There is not a moment to lose, and one’s eyes, like one’s teeth at the station buffet, fearing the departure whistle, fasten themselves on double-size portions. Every hour has its task. The absence of business, occupation, work, boredom, and visits to be made or received, plus isolation in an unknown environment, and perpetual use of a vehicle, significantly lengthens the days and, strangely enough, the trip never seems as brief as it truly is; three months of travel is equivalent in duration to a year at home. When one stays where one resides the days, indistinguishable one from another, vanish into the abyss of oblivion scarcely leaving a trace. When one experiences a new country for oneself, the memory of unusual objects, actions, and unforeseen events, form points of reference, and in marking out time, measure it, and make its extent felt.

Appelles said: ‘Nulla dies sine linea,’ (‘Never a day without a line’, according to Pliny the Elder, ‘Naturalis Historia XXXV, 84’) — in default of the Greek, I quote the Latin, though it is not the language the artist who painted Campaspe (the supposed mistress of Alexander the Great) would himself have spoken. The tourist should apply the phrase to his own activity, and say: ‘Never a day without a full schedule.’

Following this precept, the day after our expedition to Troitsa, we visited the Kremlin, to view the Museum of Vehicles, and the Treasures of the Popes.