Théophile Gautier

Travels in Russia (Voyage en Russie, 1858-59, 1861)

Part VI: Saint-Isaac's Cathedral

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

Chapter 15: Saint Isaac’s Cathedral

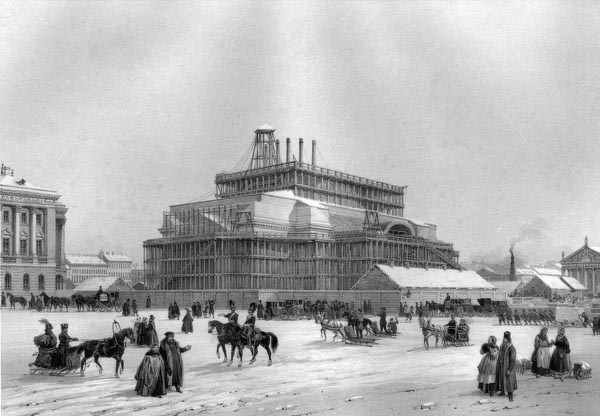

When a voyager, having entered the Gulf of Finland, approaches Saint Petersburg, what first captures their gaze, is the dome of Saint-Isaac’s Cathedral, rising above the city’s silhouette like a golden mitre. If the sky is bright and a shaft of light descends, the effect is magical: this first impression is valid, and one to be embraced. The gleaming church of Saint-Isaac (Isaakievskiy Sobor) ranks first among the religious buildings which adorn this capital of all the Russias. Of modern construction, recently inaugurated, it may be considered the finest achievement of contemporary architecture. Few temples have seen less time elapse between the installation of their foundation stone and that of their capstone. The concept proposed by the architect, Auguste Ricard de Montferrand, a Frenchman, was realised in total, without any modifications or refinements to his plan except those implemented by himself during the execution of the work. He achieved the rare happiness of completing the building he had begun which, being as important as it is, might have been predicted to absorb more than one architect’s life.

St. Isaac's Cathedral - St, Petersburg, 1889

Picryl

An omnipotent will, which nothing resisted, not even material obstacles, and which never shrank from sacrifice, operated on a large scale in undertaking this prodigious creation. Commenced in 1818, under Alexander I, continued under Nicholas I, and completed under Alexander II, in 1858, Saint-Isaac’s is a temple complete, finished within and without, in a wholly unified style, to which can be attached specific dates and an architect’s name. Unlike many another cathedral, it is not the slow product of time, a cavernous crystallisation of centuries, within which each era has, so to speak, secreted its stalactite, the tip of which the flow of faith, stopped or slowed in its passage, was unable to reach. The symbolic crane that towers against unfinished churches, for example Cologne’s Dom (Cologne Cathedral) or Seville Cathedral, has never marred its pediment. Uninterrupted labour brought it, in a little less than forty years, to the point of perfection one beholds today.

In appearance Saint Isaac’s seems a harmonious synthesis of Saint Peter’s Basilica, Agrippa’s Pantheon in Rome, Saint-Paul’s in London, and the Dôme des Invalides and Sainte-Genevieve (the Pantheon) in Paris. In designing a domed church, Auguste de Montferrand must have studied buildings of that type, and taken advantage, of the knowledge gained by his predecessors, while nonetheless displaying his own originality. He selected for his dome a most elegant curvature yet one which, at the same time, offered the most resistance; he surrounded it with a diadem of columns, and set it between four pinnacles, borrowing an aspect of beauty from each previous achievement.

Given the regular simplicity of a plan which the eye and the mind grasps without hesitation, one would scarcely believe that Saint-Isaac’s embraced in its seemingly homogeneous construction fragments of an earlier church which it was obliged to absorb and utilise, a church both dedicated to the same patron saint and venerated previously by Peter the Great, Catherine II, and Paul I, all of whom more or less contributed to its splendour, without however being able to achieve its definitive perfection.

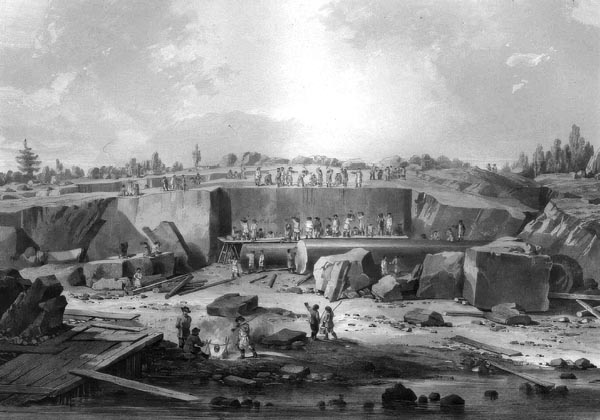

The plans submitted to Emperor Alexander I by the architect were adopted, and the work begun; but soon doubts arose as to whether it was possible to bind the new sections to the old foundations in a solid enough fashion to avoid settling and disturbance, and so raise the dome, encircled by columns, to its great height. Petitions were even penned by other architects objecting to Auguste de Montferrand’s plans. Activity slowed, though quarrying of the gigantic monoliths which were required to support the pediments and dome was continued, and on the accession of Emperor Nicholas I the plans, carefully revised, were deemed executable. Work was resumed, and its complete success showed the correctness of the calculations.

There is no need for me to pursue in detail the ingenious means used to seat this enormous mass, in an indestructible manner, on marshy ground, or to bring from a distance, and raise to their full height, its columns, each cut in a single piece, though the means employed, now half-forgotten, are no less interesting: the building, in its solidity, alone remains to our judgment.

Construction of St Isaac's Cathedral - Auguste de Montferrand, 1845

Picryl

The plan of the Cathedral of Saint Isaac of Dalmatia, a saint of the Greek liturgy unconnected to the patriarch of the Old Testament, is that of a cross with equal arms, differing in that respect from the Latin cross with its extended foot. The need to orient the new church towards the east while preserving the iconostasis already consecrated, combined with that of rendering the view of the Neva, and the statue of Peter the Great, from the main portico, visible from the rear also, would not allow of a main portal aligned with the sanctuary. Two entrances corresponding to two monumental porticos are thus set laterally in relation to the iconostasis, before which a third door opens onto a small octostyle portico, with a row of columns which are reproduced symmetrically on the opposite side. The Greek rite demanded this provision, which the architect was required to fulfil and yet reconcile with the building’s appearance, given that it could not present its main nave to the river, from which it is separated by a vast square. It is for this reason that the arms of the gold crosses surmounting the dome and the bell towers are not parallel to the facades, but indeed to the iconostasis, so that the church has a dual orientation: on the one hand religious, on the other architectural; though the inevitable discord implied, given the site, is masked with such skill that its discovery requires close attention and long examination. It is impossible to divine from within, and only assiduous study of Saint Isaac’s allowed me to see the fact clearly.

When you stand at the corner of Admiralty Prospekt (Amiralteyskiy Prospekt), Saint Isaac’s appears to you in all its magnificence, and from that point you can assess the entire building. The main facade is visible to its full extent, as well as one of the side porticos; three of the four pinnacles are visible, and the dome, with its rotunda of columns, its golden cap, and its bold lantern dominated by the sign of salvation, is highlighted against the sky.

At first glance, the effect is most satisfactory. The lines of the monument which might have appeared too severe, too sober, too Classical in a word, are happily enhanced by the richness and colour of the finest materials that human piety has ever employed in constructing a temple: gold, marble, bronze, and granite. Without descending to the tangle of colours displayed by systematically polychrome architecture, Saint Isaac’s borrows from those splendid materials a harmonious variety of tones whose honesty augments its charm; nothing is painted, nothing is false, nothing of all this luxury is intended to deceive the Lord on high. Solid granite supports eternal bronze, indestructible marble covers the walls, and pure gold gleams from the crosses, the dome, and the bell towers, granting the building the Oriental and Byzantine character of the Greek Church itself.

Saint Isaac’s rests on a granite base which should, I believe, have been more elevated in height; not that it is not closely related to the building, but, isolated in the middle of a square bordered by palaces and tall houses, the monument would have gained in perspective by being enhanced below, especially since a long horizontal line tends to appear bent in the middle, a truth that Greek art recognised by giving a slight slope from the central point to the architrave of the Parthenon. Likewise, a large public square, however flat it might appear elsewhere, always seems a little concave at its centre. The optical effect, which was not accounted for, makes Saint Isaac’s appear too squat, despite the true harmony of its proportions. This disadvantage, which should not be over-exaggerated, could be remedied by giving a slight slope to the land, from the foot of the cathedral to the end of the square.

Access to each of the three porticos which act as portals, and correspond to an arm of the Greek cross which constitutes the building’s plan, is offered by three colossal granite steps designed for a giant’s legs, without pity or concern for those of ordinary human beings, though they are actually divided centrally into nine smaller steps opposite the entrances. The fourth portico precludes this arrangement: since the iconostasis abuts it internally, it lacks a door, and the three granite steps, worthy of the temples at Karnak, reign without interruption; except that, on either side, at the corner of the wall, each step, for a brief space, is divided in three, so one can gain access to the platform of the portico.

The entire base, of granite from Finland, reddish and speckled with grey, was assembled, dressed, and polished to an Egyptian perfection, and will bear, without strain, the temple that burdens it, for many a century.

The main portico overlooking the Neva is, like all the others, an octostyle, that is to say composed of a row of eight columns of the Corinthian order, monoliths, with bases and capitals of bronze. Two groups of four similar columns, at the rear, support the ceiling partitions and the roof of the triangular pediment above, whose architrave rests on the first row; in all, sixteen columns which form a peristyle of richness and majesty. The portico of the opposite facade repeats this at every point. The other two facades, also octostyle, display only one row of columns of the same order and material. They were added during the execution of the building to the original plan, and they fulfil their purpose well, which was to adorn the somewhat bare sides of the edifice.

Bronze bas-reliefs, are embedded in the pediments of the tympanums which I will describe later when I consider the details of the building whose main lines I indicate here.

Once one has negotiated the nine steps cut into the three granite levels of the base, the last level serving as a stylobate for the columns, one is struck by the enormity of these pillars, less evident from afar due to the elegance of their proportions. These prodigious monoliths are no less than seven feet in diameter and fifty-six feet in height. Seen close to, they look like towers circled at the base by bronze, and capped with bronze vegetation. There are forty-eight of these in the four porticos, without counting those of the dome, which are actually only thirty feet in height. After Pompey’s Pillar (at Alexandria), and that raised in memory of the Emperor Alexander I, these are the largest columns the hand of man has cut, turned, and polished. Depending on the weather, a shaft of blue light, like a flash of steel, runs shivering over a surface smoother than a mirror, and the purity of line, that no break interrupts, proves that integrity of each monstrous block which otherwise the mind might doubt.

One can scarcely believe the degree of strength, power and longevity that these gigantic columns, rising in a single thrust, bearing on their Atlas-like heads the comparatively slight weight of pediments and statues, express in their silent language. They have the durability of the bones of the earth, with which they alone seem worthy of perishing.

The one hundred and twelve monolithic columns used in the construction of Saint Isaac’s Cathedral came from a quarry (Pyterlahti in Virolahti) located on a peninsula, in the Gulf of Finland, between Viborg and Hamina. We know that Finland is one of the richest countries on earth for deposits of granite. Some cosmic cataclysm, of a primeval nature, undoubtedly accumulated those enormous masses of beautiful material as indestructible as Nature herself.

Making the columns of St Isaac's Cathedral, Pyterlak quarry, Finland, 1911

Picryl

Allow me to continue my outline sketch. On each side of the projection formed by the portico, a monumental window pierces the marble wall, its cornice decorated with bronze, supported by two granite columns with bases and capitals of bronze, and a balcony with a balustrade supported by consoles; denticulated cornices, topped with attics, mark the major architectural divisions, and their projections cast favourable shadows. On each corner is a fluted Corinthian pillar above which stands an angel with folded wings.

Two quadrangular campaniles, emerging from the main line of the building, at their respective corners of the pediment, repeat the motifs of the monumental windows, namely granite columns, bronze capitals, balconies with balusters, and triangular pediments, allowing one to see, through their round-arched bays, their bells suspended without a frame, by means of a unique mechanism. A round, gilded cap, surmounted by a cross with its foot set on a crescent, caps these campaniles that the daylight traverses, and from which harmonious vibrations escape the bronze to seek the surrounding air.

Needless to say, these two bell towers are reproduced identically on the opposite facade. However, from where I stand, I can only see the dome of the third gleaming. The fourth is hidden by the mass of the dome.

On the two corners of the facade, kneel angels hanging garlands from lamp-holders of ancient form. On the parapets of the pediments are placed groups, and isolated figures, representing apostles. All this crowd of statues enlivens, happily, the building’s silhouette, breaking its horizontal lines in an appropriate manner.

I have thus described, roughly, the main masses of what we might call the first floor of the monument. We now arrive at the dome which rises boldly towards the heavens from the square platform forming the roof of the church.

A round plinth, of three large receding mouldings, serves as the base of the tower and as a stylobate for the twenty-four granite monoliths of thirty feet in height, with bronze capitals and bases, which surround the core of the dome with a circle of columns, an aerial diadem, amidst which the light plays and gleams. In their interstices twelve windows are set, and on their capitals rests a circular cornice surmounted by a balustrade intersected by twenty-four pedestals on which stand, with beating wings, as many angels holding instruments of the Passion or attributes of the celestial hierarchy.

Above this angelic crown, placed on the front of the cathedral, the dome extends. Twenty-four windows appear between an equal number of pilasters, and, above their cornice rises the immense dome sparkling with gold and striated by ribs in relief curving down to the positions of the columns. An octagonal lantern, flanked by pillars and gilded overall, surmounts the dome, which terminates in a colossal cross, struck by the light, a cliché of heraldic language, victoriously established above a crescent.

There are in architecture, as in music, rhythmic notes of a harmonious symmetry which charm the eye as regards the former and the ear as regards the latter, without disturbing either. One’s mind happily anticipates the return of a motif to a point designated in advance; Saint Isaac’s Cathedral produces this very effect: it develops like some beautiful phrase of religious music, supporting what its pure and classical theme promises, and not troubling the eye by any hint of dissonance. The pink columns form balanced choirs, singing the same melody on the four sides of the building. Corinthian acanthus-leaves flourish their green bronze on all the capitals. Bands of granite extend along the friezes like staves, the statues, through their similar or contrasting attitudes, recalling the necessary interweaving of a fugue, the great dome launching its supreme note towards the heavens amidst the four campaniles which serve as accompaniment.

No doubt the design is simple like all those drawn from Greek and Roman antiquity; but what splendid execution, what a symphony of marble, granite, gold and bronze! If the choice of this style of architecture may stir some regret in the minds of those who believe the Byzantine or Gothic style better suited to the poetry and needs of Christian worship, it should be remembered that it is eternal and universal, consecrated by the centuries, and by human admiration, and beyond the fashions of any one age!

The classical austerity of the plan adopted by the architect of Saint Isaac’s precluded him from indulging in, as regards the exterior of this temple, with its severe and ancient lines, those fantasies wrought by a capricious chisel, those garlands, those scrolls, those cherubs and sprites interspersed with trophies, those attributes often little related to the building, which only serve to hide gaps in the architecture. With the exception of the acanthus-leaves and other sparsely used pieces of ornamentation required by its order of architecture, all the decoration of Saint Isaac’s is borrowed from statuary: bas-reliefs, groups and isolated statues in bronze, that is all. Magnificent sobriety!

Foregoing my point of view, from the corner of Admiralty Prospekt, which I selected so as to swiftly sketch the general appearance of the monument, I will now describe the bas-reliefs and the statues as they present themselves from the square, as I circle the church.

The bas-relief of the northern pediment, that is to say the one which faces the Neva, represents The Resurrection of Christ; it is by Henri Lemaire, the creator of the pediment of the Madeleine, in Paris. The decoration is large, monumental, decorative, and adequately achieves its goal. The resurrected Christ springs from the tomb, standard in hand, in an upright pose, at the very centre of the triangle, which allowed the figure its full development.

On the left of this radiant apparition, a seated angel, with a thunderous gesture, pushes back the Roman soldiers assigned to guard the tomb, whose attitudes express surprise, fear, and the desire to oppose the preordained miracle; on the right, two angels, standing, welcome with reassuring kindness the holy women who have come to weep and sprinkle perfumes before Jesus’ tomb. The Magdalene collapsed on her knees, lost in grief, has not yet seen the miraculous apparition; Martha and Mary, bearing vessels filled with cinnamon and nard, which they have brought so they might pay the honours due to the dead, witness that luminous figure, which the finger of one of the angels indicates to them, rising in glory. The fine pyramidal composition and the bowed poses are naturally explicable as due to the lack of space at the external corners of the pediment. The projections of the figures, according to their position, were calculated so as to produce firm shadows, and definite contours which avoid embarrassing the eye; a happy mixture of round and flat surfaces produces all the illusion of perspective that one can reasonably ask of bas-relief, without destroying the main architectural lines.

Below the pediment, on the granite entablature of the frieze interrupted by a tablet of marble, a legend in Slavonic characters is inscribed; in the liturgical script, that is, employed by the Greek Church. This inscription, in gilded bronze lettering, translates as: ‘May the Lord answer you when you are in distress.’

On parapets, at the three corners of the pediment, statues of Saint John the Evangelist, and two of the apostles Saint Peter and Saint Paul are placed. The Evangelist, located at the summit, is seated and accompanied by his symbolic eagle; he holds a quill in his right hand and a roll of papyrus in his left. Saint Peter and Saint Paul are identified, the former by his keys, the latter by the large sword on which he leans.

Beneath the peristyle, above the main door, a large bronze bas-relief, rounded in the upper part like the arch which serves to frame it, represents Christ on the Cross Between the Two Thieves. At the foot of the tree of suffering the holy women are swooning in distress; in one corner, the Roman soldiers are playing dice for the tunic of this divinity in torment; in the other corner, woken by the last summons, the dead rise again, raising the shattered lids of their sepulchres. In the two side entrances, set in hemispheres, we see, on the left, Christ Bearing the Cross, on the right, the Descent to the Tomb. The crucifixion is by Ivan Vitali, the other two bas-reliefs are by Peter Clodt von Jürgensburg (Pyotr Kalovich Klodt).

The large monumental bronze door is decorated with bas-reliefs arranged as follows: on the lintel, The Triumphal Entry of Christ into Jerusalem; on the leaf on the left, Ecce Homo; on the right The Scourging of Christ; below, in the oblong panels, two saints in priests’ habits, Saint Nicholas and Saint Isaac, each occupy a niche with a shell-shaped arch; on the lower panels, two little angels kneeling, bear in the middle of a cartouche a radiant Greek cross, decorated with inscriptions. The drama of the Passion, in all its phases, takes place beneath the portico; the Apotheosis is gloriously resplendent on the pediment.

Let us now move on to the eastern portico, of which the large bas-relief is also by Henri Lemaire. It represents an event in the life of Saint Isaac of Dalmatia, the patron saint of the cathedral: the Emperor Valens was leaving Constantinople to go and fight the Goths; Saint Isaac, whose retreat was near the city, stopped him as he passed by, and predicted that he would not succeed in the affair, being in conflict with God because of his support for the Arian heretics. The emperor, angered, had the saint chained and imprisoned, promising him death if his prophecy was false, and freedom if it proved true. Valens was slain during the expedition, and Saint Isaac, once delivered, was honoured by the Emperor Theodosius. Valens is mounted on a horse which half-rears, frightened by the saint obstructing it in the centre of the road. It is not easy to achieve an equestrian statue in the round, and I know few that are entirely satisfactory; attempted in bas-relief the difficulty further increases, but Lemaire has happily conquered. His horse, its truth uncluttered by over-precise detail, as befits monumental statuary, bears its rider well, and the rider’s figure thus enhanced produces an excellent effect, and dominates the groups around him without painfully-sought artifice. The saint has just delivered his prediction, and the emperor’s orders have been executed. Soldiers burden the saint’s outstretched arms with chains, as he pleads and warns. It would be difficult to reconcile the dual action of the subject more adroitly. Behind Valens, crowds of warriors are drawing their swords, seizing their shields, or donning their armour, to express the idea of an army departing on an expedition. Behind Saint Isaac hides a more powerful army, in the heavens, of the poor and wretched, of women pressing their infants to their hearts. The composition has breadth, truth, and movement, and the lack of space imposed by the lower level of the triangle failed to harm the outer groups.

On the acroter of the pediment stand three statues; in the middle is Saint Luke the Evangelist, his winged calf next to him, painting the first portrait made of the Virgin, a model for subsequent Byzantine sacred images; on either side, Saint Simeon holds his saw, Saint James his book. The Slavonic inscription literally translated reads: ‘In you, Lord, I have found refuge, let me never be put to shame.’ As the iconostasis rests against the internal wall of this portico, there is no door, and therefore no bas-reliefs beneath the colonnade, which is only adorned with Corinthian pilasters.

The southern pediment was entrusted to Vitali. It represents The Adoration of the Magi, a subject that the great masters of painting have rendered redundant on canvas, but that modern statuary has rarely addressed due to the multiplicity of figures required, though that failed to deter the naive Gothic artists as regards their triptychs so patiently peopled. Here is a ceremonial composition, elegantly arranged, with an abundance of figures grouped a little too facilely perhaps, but easy on the eye. The Blessed Virgin, seated on the folds of her cloak which, by an ingenious idea of the sculptor, opens like the curtains of a tabernacle, offers to the wise men, bent or prostrate at her feet in oriental attitudes of respect, the little child, for their adoration, who will redeem the world, and whose divinity she already senses; this miraculous birth preceded by omens, these kings who have hastened from the depths of Asia guided by a star, to kneel before the manger with their gold vases and perfume boxes, all this troubles the heart of the ever-virginal Holy Mother; she is almost afraid of this child who is a god. As for Saint Joseph, leaning on a rock, he takes only a limited part in the scene, and takes these strange events on trust, without really understanding them.

Following the kings, Caspar, Melchior and Balthazar, sumptuously dressed characters abound, officers, gift-bearers, slaves, richly populating either end of the composition. The shepherds, loins clad in goatskin, slip in behind them, adoring the child from afar. Into the space between the groups, an ox with gleaming muzzle thrusts its head. But why fail to show the donkey? It too tugged its mouthful of straw from the manger, and warmed with its breath the future Saviour of the world who had been born not long since in that stable. Art does not have the right to be more precious than the Divine. Jesus did not despise the donkey, for it was on a donkey that he entered Jerusalem.

Three statues, pursuing the constant theme of the architectural decoration, appear on the acroter of this facade: at the top, Saint Matthew writing as the angel dictates; at either end, Saint Andrew with his saltire, and Saint Philip with his book and his pastoral cross. The inscription on the frieze reads: ‘My house shall be called a house of prayer.’

Entering beneath the peristyle, we find the same arrangement as in the north portico. Above the main door, within the tympanum of the arch, is framed a large galvanoplastic (electrotype) bas-relief, similar to that of the crucifixion, representing the Adoration of the Shepherds. It is a repetition of the previous scene, already familiar to us. The central group is much the same, though the Virgin turns more sympathetically towards the shepherds, and with a freer movement; the shepherds bear rustic offerings to the newborn, in contrast to the wise men who placed rich gifts at his feet. She is not enthroned, and is gentle with these poor, humble, and simple men who give of their best. She presents her child to them with complete assurance, opening the swaddling clothes to show them how firmly he is built; and the shepherds, bowing, or on one knee, admire and worship him, trusting in the word of the angel; a woman with a basket of fruit on the shoulder, and a child with a pair of doves, arrive in haste; and, high above, the angels flutter about the star which designates this stable in Bethlehem.

On the side doors, set within hemispheres, there are two bas-reliefs: the one on the left representing The Angel Announcing the Birth of Christ to the Shepherds, the other The Massacre of the Innocents. Both of these are by Alexander Loganovsky.

On the lintel of the large bronze door, we see a Presentation in the Temple: on the doors, The Flight into Egypt, and Jesus as a Child among the Doctors; below, in the conch-shell niches, a saint and an angelic warrior: Saint Alexander Nevsky and Saint Michael; further down, on the lower panels, little angels supporting crosses. This portico contains, in its decoration, all the poetry of the Nativity and childhood of Christ, as the other contained all the drama of the Passion.

On the east pediment, we saw Saint Isaac persecuted by the Emperor Valens; on the west, we witness his triumph, if such a phrase is in accord with saintly humility. The emperor, Theodosius the Great, returns victorious from his war against the barbarians, and near to the Golden Gate (of Constantinople), Saint Isaac, gloriously delivered from his prison, presents himself to him, in his poor hermit’s gown girded with a rosary, holding in his left hand the dual cross, and raising his right hand above the head of the emperor whom he blesses. Theodosius bows piously. His arm about the Empress Flacilla, he links her to his obeisance, wishing to associate her with the saint’s blessing. The intent is charming and executed with rare good-fortune. An august expression can be divined on the majestic faces of the emperor and the empress. At the feet of the laurel-crowned Theodosius are discernible the eagle and emblems of victory. To the right of the group, relative to the spectator, warriors whose attitudes exude the liveliest fervour bow, and set one knee to the ground, lowering the fasces and axes (the Roman symbols of civil and military power) before the Cross. In the background, a character, in a constrained pose, seems to move away, with a gesture full of spite and fury, leaving room for Saint Isaac, whose influence prevails: it is Demophilus, leader of the Arian sect, who had hoped to win Theodosius to their heresy. At the extremity is seen the woman from Edessa, with her child, she whose appearance suddenly caused the troops sent to persecute the Christians to retreat. On the left, a lady-in-waiting of the empress in rich clothes supports a poor paralytic woman, symbolising the charity reigning in this Christian court. A little child, playing, who possesses the supple grace of childhood, contrasts with the stiff immobility of the sufferer. At the corner of the bas-relief, with an anachronism that idealised statuary admits, the architect of the church is shown, draped in the antique style and displaying a miniature model of the cathedral which will arise later under the patronage of Saint Isaac. This fine composition, whose groupings are balanced and coordinated with happy symmetry, is by Vitali.

Beneath this portico, simpler than those of the north and south, there are no arched hemispherical bas-reliefs. It is pierced by a single door which opens before the iconostasis. This bronze door is partitioned in a similar manner to those we have already described. The bas-relief of the lintel represents The Sermon on the Mount. In the upper panels are depictions of The Resurrection of Lazarus and Jesus Healing a Paralytic; Saint Peter and Saint Paul occupy the ribbed conch-shell bays; at the bottom, angels support the sign of redemption. The vine and ear of wheat, symbols of the Eucharist, serve as motifs for the ornamentation of this door and others.

Saint Mark, accompanied by the lion, a motif that Venice has taken for its coat-of-arms, writes his Gospel on the summit of the pediment, the extremities of which are occupied by Saint Thomas, bearing his set-square while sceptically extending the finger that he seeks to plunge into Christ’s wound before he dare bring himself to believe in the resurrection, and Saint Bartholomew with the instruments of his martyrdom, the rack and the knife. On the frieze the following inscription may be read: ‘To the King of Kings’.

With its archaic form, the Slavonic script lends itself to monumental legends. It is a means of ornamentation, like Kufic lettering. There are other inscriptions beneath the peristyles and above the doors. They express religious or mystical ideas. I have only translated those which are the most visible.

Vitali, with the help of Robert Salemann and an artist of the Boilly family, modelled the sculptures of all the doors; to him we also owe the evangelists and apostles on their acroters. These figures are no less than fifteen feet two inches tall. The angels kneeling beside lighting-columns are seventeen feet high, and the garlanded columns themselves, twenty-two. These angels, with large outstretched wings, are like mystical eagles fallen from the heights to perch on the four corners of the building.

As I have said, a swarm of angels are posed around the crown of the dome. The height at which they are placed makes it difficult to distinguish the details of their features, but the sculptor was able to give them elegant, slender profiles that are easy to appreciate from below.

Thus, on the cornice of the dome, on the parapets, attics and entablatures of the building, not to mention the characters half-embedded in the pediments, the bas-reliefs of the arches, and the hemicycles, and the figures of the doors, the fifty-two statues adorning Saint Isaac’s, all three times as large as life, constitute an eternal population in bronze, varied in their poses, but subject, as if they comprised an architectural choir, to the cadences of a linear music.

Before entering the church, whose outline I have drawn as faithfully as the inadequacy of words permits, I should say that it must not be thought, despite its pure, noble, and severe lines, its sober and sparse ornamentation, and its austerely ancient style, that the cathedral of Saint-Isaac’s, in its perfect regularity, possesses that cold, monotonous, slightly tedious appearance of the architecture that we call Classical, for want of a more accurate expression. The gilding of its domes, the rich variety of materials employed, prevents it from being disadvantaged so, and in this climate the play of light and colour shades it with unexpected effects, which render it completely Russian, not Roman. The spirits of the North flutter about this grave monument and grant it a national character without detracting from its ancient and grandiose appearance.

Winter in Russia has a particular poetry; its rigours are compensated for by the beauty of many a picturesque effect or aspect. Snow and ice silver those golden domes, charge the gleaming lines of the entablatures and pediments, add touches of white to the bronze acanthus-leaves, create luminous points on the statues’ projections, and alter all the tonal relationships by magical transposition. Saint Isaac’s, seen thus, takes on a completely local originality. It is superb of hue, or is highlighted, whitely enhanced, against a curtain of grey cloud, or is silhouetted against one of those ‘skies’, in turquoise and pink, that shine above St. Petersburg when it is cold and dry, and the snow crunches underfoot like powdered glass. Sometimes, after a thaw, an icy overnight breeze freezes the moisture coating the granite and marble body of the monument. A network of pearls, finer and rounder than the dew-drops on leaves, envelops the gigantic columns of the peristyle. The reddish granite turns the most tender pink, and is edged with the hue like a velvety peach, or like plum-blossom; it is transformed to an unknown material, similar to that precious stone of which celestial Jerusalems are built. Crystallised vapour covers the building with a diamantine powder that send forth sparks and flame when a ray of light touches it; it looks like a jewelled cathedral in the City of God.

At each hour of the day its appearance varies. View Saint-Isaac’s in the morning, from the quay beside the Neva, and it appears the colour of amethyst and burnt topaz in the middle of a halo of milky and rose splendours. The pale mists that float at its base detach it from the earth so that it hovers above a vaporous archipelago. In the evening, seen from the corner of Little Morskaya Street (Malaya Morskaya), and given a certain incidence of light, its windows caught by the rays of the setting sun, it seems illuminated as if on fire within. The bays set in the dark walls glow brightly; sometimes, when it is misty, under a low sky, clouds descend on the dome, and crown it like vapour over the summit of a mountain. I have viewed the strange sight of the lantern and upper half of the dome rising above a bank of fog. The cloud, separating, with a layer of cotton the gilded hemisphere from its base, granted the cathedral a prodigious elevation, and the appearance of a Christian tower of Babel about to seek in the heavens, but not defy, that One without whom nothing can stand firm.

Night, which in other climes casts its opaque veil over buildings, cannot entirely extinguish Saint Isaac’s. Its dome, with its tones of pale gold, remains visible beneath the black canopy of the heavens, like an immense half-lit bubble. No darkness, even that of the most sinister of December nights, prevails against it. One still sees it, floating above the city and, though the homes of human beings fall into shadow, and slumber, God’s dwelling house shines, seeming to watch over it from above. When the darkness is less dense, when the glitter of the stars and the vague glow of the galaxy leave only the ghosts of objects discernible, the vast mass of the cathedral rises majestically and takes on a mysterious solemnity. Its columns, as smooth as ice, are outlined by some unexpected gleam, and, on the attics, the statues, vaguely glimpsed, seem like celestial sentinels committed to guardianship of the sacred edifice. What remains of the diffuse light in the sky focuses on some point on the dome with such intensity that the nocturnal passerby might take this unique flake of gold for a lighted lamp. Sometimes, a still more magical effect occurs: luminous fiery touches blaze at the extremities of each of the raised ribs which divide the dome, surrounding it with a crown of stars, a sidereal diadem surrounding the golden tiara of the temple. An age of greater faith and less belief in science would have thought it a miracle, since this perfectly natural effect dazzles the eye in a seemingly inexplicable manner.

If the moon is full, and sails clear of the clouds towards midnight, Saint Isaac’s is lit by her opal glow, in a symphony of tones: ashen, silvery, bluish, violet, all of an unimaginable delicacy; the hue of the granite fades to that of a pink hydrangea, the bronze draperies of the statues whiten to the shade of linen robes, the gilded caps of the pinnacles exhibit reflections and translucencies of an amber paleness, while threads of snow on the cornices emit straw-coloured flashes here and there. From the depths of the northern sky, blue and cold as steel, she seems to have come to gaze upon her silver face in the golden mirror of the dome; the rays which result are reminiscent of the electrum of the ancients formed of molten gold and silver.

From time to time, the enchanted lights, with which the North consoles itself for the length of its frozen nights, deploy their magnificence above the cathedral. The aurora borealis launches its immense polar fireworks behind the monument’s dark silhouette. Its bouquet of rockets, effluvia, irradiations, and phosphorescent veils, spreads forth, in silver, mother-of-pearl, and opal, dimming the stars and making the dome, always so luminous, appear utterly black, except for the bright gleam of the golden sanctuary lamp that nothing eclipses.

I have sought to depict Saint Isaac during the days and nights of winter. Summer is no less rich in effects, as new as they are admirable.

During those long days, barely interrupted by an hour of diaphanous night which is at once both twilight and dawn, Saint Isaac’s, flooded with light, gains the majestic clarity of a Classical monument. The vanishing vapours reveal its superb reality; and when transparent shadow envelopes the city, the sun continues to shine on the colossal dome. From the horizon, beneath which it plunges only to promptly re-appear, the sun’s rays still reach the golden hemisphere. Though, in the mountains, the highest peak may still be illuminated by the flames of the setting sun long after the lower summits and the valleys have been bathed in evening mist, ultimately its glow quits that vermillion spire and seems to withdraw, regretfully, to the heavens, yet a gleam of light never abandons the dome. Even if all the stars in the firmament were lost, there would still be one glittering from Saint Isaac’s!

Now that I have given you, to the extent I am able, an idea of the cathedral in its various external aspects, let us penetrate the interior, which is no less magnificent.

One usually enters Saint Isaac’s by the south door, but let us seek the west door, which faces the iconostasis; this is the direction from which the building best presents itself. From the first, one is struck by amazement: the massive grandeur of the architecture, the profusion of rarest marble, the brilliance of the gilding, the fresco tints of the wall paintings, the shimmer of the polished paving stones in which objects are reflected, everything combines to dazzle your eyes, especially if your gaze falls, unavoidably, on the iconostasis. The iconostasis, a marvellous edifice, a temple within a temple, its facade of gold, malachite and lapis lazuli, its doors of solid silver, is nevertheless only the veil before the sanctuary! One’s face inevitably turns towards it, whether the open leaves reveal, in all its sparkling translucency, the colossal Christ in stained glass, or, closed, display only their curved bay, the purple curtain of which seems dyed in the blood of the divinity.

The interior layout of the building is simple enough for the eye and the mind to grasp immediately; three naves lead to the three doors of the iconostasis, cut transversely by the nave forming the arms of the cross which, terminate externally in the projecting porticos; at the point of intersection rises the dome; four domes set symmetrically at the corners emphasise the architectural composition.

On a marble floor, rest fluted columns and pilasters of the Corinthian order, with bases and capitals of gilded bronze and ormolu, adorning the building. This decorative order, applied to the walls and the massive pillars supporting the arched vaults and the roof, is topped by an attic divided by pilasters, presenting panels and frames for paintings. On this attic are set the archivolts, whose tympanums are decorated with religious subjects.

The walls, from base to cornice, between the columns and pilasters, are clad in white marble from which panels and compartments in various colours emerge; of Genoa-green, cherry-red, and Siena-yellow marble, various jaspers, and red porphyries from Finland, every stone that the veins of the richest quarries were able to deliver, by way of beauty. Recessed niches supported on consoles contain paintings, relieving the flatness of surface in an appropriate manner.

The rosettes and modillions (brackets) of the soffits (undersides) are in bronze, gilded by the galvanoplastic (electrotyping) method, and stand out from their marble coffers in vigorous projections. The ninety-six columns or pilasters are from the quarries of Tivdiya (in Karelia, north-east of Lake Ladoga), which provided a beautiful marble veined with grey and pink. The white marble came from the Seravezza quarries (in Tuscany). Michelangelo preferred it to that from Carrara, which says all, for what greater a connoisseur of marble was there than the architect of Saint Peter’s and sculptor of the tomb of the Medicis!

The plan of the interior having been sketched in a few lines, we now arrive at the dome whose gulf yawns above the visitor’s head, suspended with inescapable solidity in the air. Here, iron, bronze, brick, granite, and marble combine, according to the best mathematical calculation, in well-nigh eternal resilience. The dome’s interior height, from the marble pavement to the lantern’s vault, is two hundred and ninety-eight feet and eight inches, or forty-two sazhens and two arshins (Russian measure: a sazhen equates to seven feet, an arshin is a third of a sazhen, or two feet four inches). The interior length of the building is two hundred and seventy-seventy feet and eight inches, or thirty-nine sazhens and two arshins; its breadth within is one hundred and forty-nine feet four inches, or twenty-one sazhens and one arshin. I stress these measurements only because they enable one to appreciate the true grandeur of the building, and provide an overall scale, allowing one to assess the relative proportions of its details.

At the summit of the lantern, a colossal sculpted Holy Spirit spreads its white wings on high, amidst rays of light. Below it is a rounded half-dome with gold palmettes on an azure field; then comes the great spherical vault of the dome, bordered at its upper opening by a cornice, whose frieze is decorated with garlands, and gilded heads of angels, resting at its base on the entablature of twelve fluted pilasters of the Corinthian order between windows also twelve in number.

A false balustrade, providing a transition between the architectural and painted features, crowns this entablature, the large circular composition above representing The Virgin in Glory beneath a bright sky. This painting, like all those of the dome, was entrusted to Karl Bryullov, known in Paris for his painting of The Last Day of Pompeii (now in the State Russian Museum, St, Petersburg) which was displayed at one of the exhibitions. Bryullov deserved the honour; but illness ending in premature death prevented him from executing this important work himself. He could only paint the partitions, and though his ideas and instructions were followed religiously, we must regret that the eye, hand, and indeed genius of the master could not complete these paintings, suited as they are however to their decorative purpose. He would doubtless have added all that they lack: the touch, colour, fire, everything that comes with the execution of wisely ordered work, which not even a like talent, following another’s ideas, is able to emulate.

To grant some order to my description, let me face the iconostasis; we then have before us the group which is the centre and crux of this vast composition (Bryullov’s original design is described here.)

The Holy Virgin, in the midst of glory, is enthroned on a seat of gold; eyes downcast, hands crossed modestly on her breast, she seems, even in heaven, to submit to rather than accept this triumph; but she is the humble servant of the Lord, ancilla Domini, and she resigns herself to apotheosis.

On either side of the throne stand Saint John the Baptist, the precursor, and the other Saint John, the beloved disciple of Christ, recognisable by his symbolic eagle. They both deserve this place of honour: one announced the coming of Christ; the other followed him to the Garden of Olives, assisted at the Passion, and it was to him that the dying divinity consigned his mother.

Below the throne, flutter little angels, clasping lilies, symbols of purity. Larger angels with outstretched wings, in daringly foreshortened poses, placed here and there, lift banks of clouds supporting other groups that I will describe, starting from the Virgin’s left relative to the viewer and circling the dome until returning on her right, thus closing the cycle of composition. One of these angels is charged with a long sword, an attribute of Saint Paul whom we actually see kneeling above him, on a cloud near to Saint Peter, with his head turned towards the Virgin; cherubim open the Book of Epistles and toy with the golden keys of paradise.

On the cloud that floats above the balustrade and forms an aerial base for the groups, we note, beyond Saint Peter and Saint Paul, an old man with a white beard, in the habit of a Byzantine monk: it is Saint Isaac of Dalmatia, the cathedral’s patron saint. Near him stands Saint Alexander Nevsky, wearing a breastplate and a purple mantle; behind him, angels brandish flags, and the image of Christ on a golden disc indicates the services rendered to religion by the holy warrior.

The next group consists of three saintly women kneeling: Anne, mother of the Virgin, Elizabeth, the mother of the Baptist, and a sumptuously dressed Saint Catherine, in an ermine robe and brocaded dress, with a crown on her head; not because she belonged to a royal or princely family, but because she bears the triple crown of virginity, martyrdom, and science, her original name being changed from Dorothea to Catherine, a name whose root, Kether in Hebrew, means ‘the crown’. Thus, the ornament is wholly allegorical. The angel beneath the cloud holds a fragment of a wheel with curved teeth, part of the instrument of torture applied to the saint.

Separated by a slight interval from the trio I have just described, a third cloud bears Saint Alexis, the man of God, dressed in a monk’s robe, and the Emperor Constantine with a gold breastplate, draped in purple; an angel beside him bears the axes and fasces; a second angel, to the rear, holds the insignia of command, an ancient sword in its sheath.

The last figure, on the right of the Virgin’s throne, is Saint Nicholas, Bishop of Myra and patron saint of Russia, dressed in a dalmatic and a green stole strewn with gold crosses, kneeling in adoration before the mother of God; he is surrounded by angels holding banners and sacred books.

Recognised here are the patron saints of Russia and of the imperial family. The mystical idea of this immense composition, which is no less than two hundred and twenty-eight feet in circumference, is the triumph of the Church symbolized by the Virgin.

The composition of this painting is somewhat reminiscent of that on the cupola of Saint Genevieve (the Pantheon, in Paris), by Antoine-Jean Gros. That is not a criticism of Bryullov; such similarities are inevitable in the depiction of religious subjects whose main outlines are determined in advance. Complying with the intentions of the architect, better than many another artist responsible for paintings elsewhere, Karl Bryullov, or those who executed the works to his designs, utilised plain matte areas, avoiding forceful colours and blacks always harmful where paintings are concerned, in that they conflict with the architectural concept, and grant their subjects a presence which disturbs one’s view of the building’s lines.

These paintings, and the others which adorn the cathedral, even when they are on a gilt background, never seek to reproduce the hieratic, immobile, unchanging attitudes of Byzantine art. Auguste de Montferrand very judiciously thought that since the church, of which he was the architect, borrowed its forms from the pure Greek and Roman styles, the artists responsible for the paintings should take their inspiration from the mighty Italian school, the most skilled and learned as regards the decoration of religious buildings in those styles. The paintings in Saint Isaac’s are therefore in no way archaic, contrary to the habits of the Russian Church, which willingly conforms to models fixed during the earliest days of the Greek Orthodox Church and preserved, traditionally, by the artists of the monastery on Mount Athos.

Twelve large gilded angels, acting as caryatids, support consoles upon which the bases of the pilasters rest that form the interior order of the dome, and separate the windows. The angels measure no less than twenty-one feet in height, and were executed by the galvanoplastic (electrotyping) process in four pieces, then invisibly welded together. It was possible to grant them a degree of lightness which, despite their size, fails to burden the cupola. This crown of gilded angels, that the vivid light floods, causing them to glitter with metallic reflections, produces an extremely rich effect.

The figures are arranged in a certain manner appropriate to the architecture, but with sufficient variety of pose and movement to avoid the tedium that would result from too rigorous a uniformity. Various attributes, such as books, palms, crosses, scales, crowns, and trumpets, generate slight inflections of attitude, while designating the celestial functions of these gleaming statues.

The empty spaces between the angels are filled with seated apostles and prophets, each accompanied by the traditional symbol rendering them recognisable. All the figures, voluminously draped and in excellent style, stand out against a palely lit background of approximately the same tonal value. The general appearance is bright, approaching as close as possible to that of fresco.

The four Evangelists, statues of colossal size, occupy the pendants. The artist has attempted in these figures to reproduce the fierce and violent attitudes loved by the painter of the Sistine Chapel. The pendants, due to their odd shape, obliged him to compress the composition to fit the spaces that contain them, and the difficulty created by their framing often inspired him. The statues possess a great deal of character.

Saint Mark is recognised by the winged lion; he holds his Gospel in one hand, raising the other to preach or bless. A circle of gold shines about his head, a large blue drape envelops his knees. Above him, angels bear a cross.

Saint John, dressed in a green tunic and red mantle, writes on a long strip of papyrus unrolled by two angels. Near him, the symbolic eagle flaps its wings, while from its eyes flashes the lightning of the Apocalypse.

Leaning on his ox, Saint Luke gazes at a portrait of the Virgin, the work of his brush, that angels present to him. Above his haloed head, floats a labarum (standard); a reddish-orange drape hangs about it in massive folds.

Saint Matthew’s angel-companion, stands at his side. The saint, in a purple tunic and yellow mantle, holds a book in his hand. On the dark sky which serves as a background to him, as with the other figures, cherubim flutter and a star shines.

At the tips of the four pendants are recessed paintings represent scenes from the Passion of Christ. In one, Judas, preceding soldiers bearing lanterns and torches, gives his master the treacherous kiss which designates him among the other disciples. In another, Christ is flogged by two tormentors armed with knotted ropes. The third shows us the Righteous One, to whom the people preferred Barabbas, being taken from the courtroom to be delivered to the executioner, while Pontius Pilate, on his tribunal, washes his hands of the blood which eternally stains them.

The fourth painting represents what the Italians call ‘spasimo’, the swooning of the victim beneath the cross of torment, on the path to Calvary. The Virgin, the holy women, and Saint John, exhibiting attitudes of desolation, escort the condemned divinity.

In the attic of one arm of the cross of the transverse nave, one notices, on the right when facing the iconostasis, The Sermon on the Mount, by Pierre Bazin. On a high place, shaded by a few trees, Jesus, seated, preaches among the disciples; the crowd is hastening to hear him; paralytics hoist themselves on their crutches; the sick, eager for the divine word, are being dragged there, in the blankets from their beds; the blind grope their way there; women listen in a heartfelt manner, while, in a corner, Pharisees argue and dispute; the composition is fine, and the well-distributed groups grant the figure of Christ, placed in the centre, its full importance.

The two lateral paintings have as their subjects The Parable of the Sower and The Good Samaritan. In one, Jesus walks amidst the fields with his disciples; he shows them the Sower distributing the grain and the birds fluttering in the sky above of his head. In the other, the Good Samaritan, having descended from his horse, is pouring oil over the wounds of the young man abandoned at the edge of the road, whose cries the Pharisee refused to hear. The first of these paintings is by Nikolai Nikitin; the second, by Vasily Sazonov.

On the vault, in a panel framed by rich ornamentation, cherubs support a book against a skiey background.

Opposite The Sermon on the Mount, at the other end of the nave, in the attic, is a vast painting by Eugène Pluchart, The Feeding of the Five Thousand. Jesus occupies the centre, while his disciples distribute loaves, constantly and miraculously renewed, to the hungry crowd; bread symbolic of the Eucharistic bread on which the generations and multitudes of earth feed.

The paintings on the two lateral walls represent The Return of the Prodigal Son and The Workers in the Vineyard whom the stewards wish to drive away but whom the master welcomes: the one is by Sazonov; the other, by Nikitin. Cherubim raising a ciborium are painted on the panel of the vault.

The central nave, from the transept to the door was decorated by Fyodor Bruni. In the depths of the tympanum, Jehovah, enthroned on a cloud, and surrounded by a swarm of archangels, angels and cherubim forming a circle, the symbol of eternity, seems content with His creation and blesses it. At the knotting of His brow, the infinite quivered in its intimate depths, and from nothing arose all things.

With its leafy trees, flowers, and animals, the terrestrial paradise flourishes on the attic. The first pair of human beings are living in peace among species whom, as a consequence of the former’s actions, sin and death will later render hostile. The lion as yet leaves the gazelle unharmed, the tiger refrains from attacking the horse, the elephant seems unaware of its defensive powers, and all respect the likeness of God, stamped on the faces of His guests in Eden. On the vault, amazed angels contemplate the sun and moon, lights which only now illuminate the firmament.

The subject of the attic panel is The Flood. The waters, vomited in cataracts from the abyss and the sky, cover that early world so swiftly forfeited, which has already given God cause to regret His creation. Various peaks, which the rising waters will soon cover, still emerge alone from the shoreless ocean. The last remnants of the human race, condemned to perish, cling there desperately, their stiffened muscles contracting as they seek to climb to some narrowing plateau. In the distance, beneath the rain falling in torrents, floats Noah’s ark, bearing in its hollow compass all of the ancient creation that will survive.

On the other wall, The Sacrifice of Noah forms a pendant to The Flood. Bluish smoke from the accepted sacrifice rises to heaven, through the serene air, from a primitive altar made from a lump of rock; the patriarch, standing, dominates with his great height which is that of antediluvian Man, his sons and daughters-in-law prostrated around him, each pair of whom will be the source of an extensive human family.

In the background, against a curtain of dissipating cloud, the rainbow rounds its variegated curve, that symbol of alliance which, appearing at the close of the deluge, promises that the waters will no longer cover the Earth, now protected from cosmic catastrophe until the Last Judgment.

Further on, The Vision of Ezekiel covers a large vaulted space. Standing on a segment of rock, beneath a sky illuminated by crimson flames, amidst the Valley of Jehoshaphat whose population of the dead germinates, quiveringly, like wheat in the furrow, the prophet watches the dreadful spectacle taking place around him; to the ineluctable call of angels sounding their trumpets, ghosts rise in their shrouds; skeletons drag themselves about on their emaciated fingers, and recompose their scattered bones; corpses, rising from the tomb, reveal their decomposed faces into which life returns, accompanied by expressions of terror and remorse. These spirits, that were the people of the earth, seem to ask for grace and regret the grave’s darkness, except for a few righteous people, full of hope in the divine goodness, who seem untroubled by the prophet’s thunderous gesture.

A powerful imagination and masterful stylistic vigour are exhibited in this painting which is of considerable dimensions: a study of the Sistine frescoes is evident here. The colour is sober, strong and, in its historic tones, a noble garment for ideas, which the moderns too often abandon for the superficial effects and minor accuracies of detail which falsify monumental and decorative painting.

At the end of this same nave, on the vault above the iconostasis, Fyodor Bruni painted The Last Judgment, of which Ezekiel’s vision was only a prophecy. A colossal Christ, its proportion double and even triple that of the figures which surround it, stands before a cloud-mounted throne; I greatly approve of this Byzantine manner of having the divine and principal character dominate visibly: it impresses itself on both naive and cultivated imaginations, the former in a material way, the latter in an ideal one. The centuries are complete, time is no more, all is eternal, both the reward and the punishment. Overthrown by the breath of angels, the ancient skeleton falls to dust, his scythe broken. Death, in turn, has died.

To the right of Christ, in an ascending motion, press swarms of blessed souls, with pure and slender forms, and long chaste draperies, their faces radiant with beauty, love and ecstasy, whom the angels welcome, fraternally. To his left, whirling, in the impetuosity of their fall, driven backwards by haughty and severe angels, with bladed wings and flaming swords, crowds of the damned, whom we recognise by their hideous forms, along with representations of those evil traits which lead humankind into the abyss: Envy, whose locks of hair scourge her narrow temples like knotted snakes; Avarice, sordid, angular, and hunched; Impiety, casting a gaze of impotent menace towards the heavens; all these culprits, weighed down by their sins, stumble into the abyss, where the grasping hands of demons, whose bodies are not shown, wait to tear them apart in eternal torture; their gnarled, clawed hands like to the iron combs employed by executioners, are highly poetic and evoke a most tragic dread. It is a composition worthy of Dante or Michelangelo. Those hands I have viewed in the cartoon, but sought in vain in the painting; the projection of the cornice, the curve of the dark vault which constricts the corners, doubtless prevented me from discerning them.

One may divine, from this brief description, necessarily subordinate to that of the whole church, how important Fyodor Bruni’s work is with regard to Saint-Isaac’s. It would be desirable for the work of this remarkable artist to be engraved or photographed, since his paintings have not achieved the degree of fame they deserve. His compositions with numerous figures, two or three times larger than life, cover immense surfaces, and there are few modern painters who have been granted the opportunity of executing similar commissions. The artist’s work is not confined to the above, since he executed several paintings in the sanctuary itself, paintings of which I will give an account later.

At both ends of the transverse nave, of which Fyodor Bruni’s Last Judgment occupies the central portion, are paintings arranged as follows, which a paucity of light prevents one from appreciating in their entirety. On the attic, in the background, The Resurrection of Lazarus, brother of Mary and Martha, by Zinoviev (Ivan Ignatyevich Zinoviev); above, on the tympanum, Mary at Christ’s feet, again by Zinoviev; on the lateral wall, Jesus Healing a Man Possessed; The Marriage at Cana; and Christ saving Saint Peter from the Waters, are all by the same artist. On the other side, the main painting on the attic represents Jesus Resurrecting the Son of the Widow of Nain; that on the tympanum, Jesus Christ Allowing the Little children to Approach Him, both by Zinoviev; the side wall contains depictions of Christ’s miracles: Healing the Paralytic; The Repentant Woman; and Healing the Blind, by Nikolai Alexeyev.

Another transverse nave, since the church, divided into three naves lengthwise offers five breadthwise, contains paintings from different artists. Joseph Welcoming His Brothers to Egypt, by Nikolai Maykov, is a vast composition which occupies the entire attic. Jacob on His Deathbed Surrounded by His Sons Whom He Blesses, is represented on the tympanum; this painting is due to Charles de Steuben. On the walls in three panels, following the architectural divisions, Eugène Pluchart has painted: The Sacrifice of Aaron; The Arrival of Joshua at the Promised Land; and The Fleece Found by Gideon.

The Passage of the Red Sea, by Alexeyev, occupies the attic, facing Joseph Welcoming His Brothers to Egypt. It is a tumultuous and disorderly composition, with too much violent movement perhaps for a mural painting. I found some difficulty in disentangling the subject, given the multiplicity of figures, especially with a background unfavourable to the process. Above, The Exterminating Angel Strikes the Firstborn of Egypt. This composition is also by Nikolai Alexeyev.

Moses Saved from the Waters; The Burning Bush; and Moses and Aaron Before Pharaoh, by Pluchart, decorate one of the walls; the other is adorned with panels depicting Mary Celebrating the Praises of God; Jehovah Delivering the Tablets of the Law to Moses on Mount Sinai; and Moses Dictating his Last Wishes, by Fedor Zavyalov. At each end of the side naves, to the right and left of the door, is a rounded dome. On the vault of the first, Franz Riss has depicted Saint Fevronia, surrounded by angels bearing palm-fronds, instruments of torture, torches, brands for the pyre, and swords; in the pendants, on a gold background imitating mosaic, the prophets Hosea, Joel, Haggai, and Zechariah; and in the recesses of the arches, historical and religious subjects, among others the events involving Menin and Pozharsky, names which make every patriotic heart in Russia throb. Allow me to devote a few lines to this painting, of which it is not enough, especially for readers who are not Russian, to merely state the subject, as one may in regard to some motif taken from Sacred History, known to all Christians, whatever the communion to which they belong.

Prince Dimitry Pozharsky and the mujik Kusma Menin resolved (in 1612) to save their homeland threatened by Polish invasion. They are here preparing to leave, advancing together at the head of their troops. The nobility and the people are united, in the persons of the two heroes, who, wishing their action to gain divine protection, have had the clergy bear before them the holy image of Our Lady of Kazan, on whom there falls a celestial ray of light as a sign of God’s acquiescence. As the procession passes men and women, children, old folk, individuals of all ages and every class prostrate themselves in the snow. In the background one can see palisades, and the crenelated walls and towers of the Kremlin.

The other tympanum shows us Dimitri Donskoy kneeling at the threshold of a monastery and receiving the blessing of Saint Sergius of Radonezh, here accompanied by his monks, before Dimitri departs to gain his victory, at Kulikovo (in 1380), over the Tartars commanded by Mamai.

The third painting depicts Ivan III showing his plan for the Assumption Cathedral in Moscow to Saint Peter the Metropolitan. The saintly character seems to approve, and calls on Heaven to protect the pious founder. A council of the apostles, upon whom the Holy Spirit is descending, fills the fourth arch.

On the dome which is symmetrical to this, I note the following paintings, all by the hand of Franz Riss: on the ceiling, The Apotheosis of Saint Isaac of Dalmatia; on the pendants: Jonas, Nahum, Habakkuk and Zephania. The recesses formed by the arches depict subjects relating to the introduction of Christianity to Russia: The Proposal Made to Vladimir the Great of Embracing the Christian Faith; The Baptism of Vladimir; The Baptism of the Inhabitants of Kiev; and The Pronouncement of the Adoption of Christianity by Vladimir. The order which adorns these domes is the Ionic.

These paintings, though skilfully composed, are rather too focused on their historical content. The artist, in love with the effects created, took insufficient note of the requirements of wall-painting. The scenes, framed by arches or architectural divisions needed quieting rather than dramatising, rendering them closer to polychrome bas-relief. When working in a church or a palace, the painter must be, above all, a decorator, and sacrifice individual self-esteem to the general effect of the monument. The work must be linked to it in such a way that it cannot be seen as detached from it. The great Italian masters in their frescoes, so different in execution from their paintings, understood, more deeply than artists of other nations, this particular aspect of their art.

This criticism is not specifically aimed at Franz Riss; it is deserved, in differing degrees, by most of the artists commissioned to paint the interior of Saint Isaac’s, who did not always make the sacrifices regarding execution required by wall painting.

The solid walls to which the columns are applied, and the pilasters, as well as the walls, are decorated with subjects executed by different artists, and in the recesses, from niche to console, with tablets adorned with inscriptions. In the niches, Carl Timoloen von Neff has painted: The Ascension, Jesus Christ Sending His Image to King Abgar of Edessa, The Exaltation of the Cross, The Birth of the Virgin, The Presentation in the Temple, The Intercession of the Virgin, and The Descent of the Holy Spirit. These paintings by Carl von Neff are full of colour and feeling; I would rank them among the most satisfying in the church.

Charles de Steuben has depicted: Saint Joachim and Saint Anne, The Birth of Saint John the Baptist, The Entry into Jerusalem, The Crucifixion, Christ in the Tomb, The Resurrection, and The Assumption of the Virgin. While Cesare Mussini has added: The Annunciation, The Birth of Jesus, The Circumcision, Candlemas, The Baptism, and The Transfiguration.

All these paintings in Saint Isaac’s were done in oil, since fresco is unsuited to humid climates and its much-vaunted strength fails to resist the action of two or three centuries, as demonstrated, sadly, by the state of deterioration, more or less advanced, of most of the masterpieces which great artists thought would be preserved in an eternally fresh state. Encaustic painting is a possibility; but the handling of it is difficult, unfamiliar to most, and rarely practised. Also, the wax employed in the areas worked shimmers; furthermore, too little time has been spent testing this method, so that, as regards its life, we have nothing but theoretical predictions. It was therefore with good reason that Auguste de Montferrand chose oil for the paintings of Saint Isaac’s (nonetheless the oil paintings were affected by the cold and damp, and Montferrand gradually replaced them with mosaics, the work remaining unfinished.)

We now arrive at the iconostasis, a wall of holy images enshrined in gold, which clothe the mysteries of the sanctuary. Those who have seen the gigantic altarpieces in Spanish churches have some idea of the adornment the Greek Orthodox religion grants to this part of its churches.

The architect raised his iconostasis to the height of the attic, such that it merges with the architecture of the building, and does not conflict in size with the colossal proportions of the monument whose entire background it occupies, stretching from one wall to the other. It forms the facade of a temple within a temple!

Three steps of red porphyry form the base. A white marble balustrade, with gilded balusters inlaid with precious marble, forms the line of demarcation between the priest and the faithful. The purest marble from Italian quarries serves as background to the iconostasis’ wall. This background, which would seem rich anywhere else, almost disappears behind the splendid ornamentation.

Eight malachite columns, of the Corinthian order, fluted, with bases and capitals of gilded bronze, and two engaged pilasters, form the façade and support the attic. The colour of the malachite with its metallic sheen, its green coppery nuances, strange and charming to the eye, and its perfect polish, that of solid stone, surprises the eye with its beauty and magnificence. At first, it is hard to believe that such luxury is real, since malachite is used only for table-tops, vases, caskets, bracelets and jewellery, while these columns with their pilasters, are forty-two feet high. Cut from the block by circular saws designed for the purpose, the malachite plates fit, with a precision which makes them seem a single sheath, onto a copper drum, which supports an iron cylinder cast in a single operation, on which the foot of the attic stands.

The iconostasis is pierced by three doors: the central one gives access to the sanctuary, the others to the chapels of Saint Catherine and Saint Alexander Nevsky. The layout is as follows: a pilaster at the corner then a column, then a chapel door; then three columns, the main door, three more columns, a chapel door, a column and a pilaster.

These columns and pilasters dividing the wall-space form frames filled by paintings on a gold background imitating mosaic, models for real mosaics which are replacing them as they are completed. From the base to the cornice, there are two levels of frames separated by secondary cornices behind the columns, which rest on either side of the central door on two columns of lapis lazuli, and at the doors of chapels on pilasters of white statuary marble.

Above is an attic intersected by pilasters, inlaid with porphyry, jasper, agate, malachite and other indigenous precious materials, and decorated with gilded bronze ornaments of a richness and brilliance that no altarpiece in Italy or Spain exceeds. These pilasters above the columns border compartments also filled with paintings on a gold background.

A fourth stage, like a pediment, surmounts the line of the attic and is topped by a large group of gilded angels in adoration at the feet of the cross, by Ivan Vitali, while an angel kneeling in prayer adorns each side. In the central panel, a painting by Semen Zhivago represents Jesus Christ in the Garden of Olives accepting the bitter chalice during that funereal wake throughout which his dearest apostles slept.

Immediately below, two large sculpted angels, holding sacred vases, their wings silvery and palpitating, their robes swirling in the air, accompanied by smaller, less prominent angels, recessed into the wall, touch shoulders with a larger panel representing the Last Supper, half painted, half in bas-relief. The figures are painted; the background, gilded, shows the room where the Last Supper is in progress, the perspective is skilfully handled. This painting is also by Semen Zhivago.

Over the arch of the central door, decorated with a semicircular inscription in Slavonic characters, rises a group of figures arranged thus: in the middle, Christ, the eternal pontiff according to the ‘order of Melchizedek’ (see Psalm 110:4 and Hebrews 7:17), is enthroned on a richly decorated seat. His left hand holds the earthly globe, represented by a lapis lazuli sphere, while the right hand makes the gesture of consecration. A halo surrounds his head; his vestments are of gold. Behind his throne, angels crowd; at his feet lie the symbolic winged lion and ox. To his right the Blessed Virgin kneels; to his left Saint John the Baptist.

This group, which overlaps the cornice, offers a remarkable feature: the figures are in the round, with the exception of their heads and hands which are painted on sheets of silver or other metal shaped appropriately. This combination of Byzantine icon and solid sculpture produces an effect of extraordinary power, and it takes careful examination to see that the faces and bared hands are not themselves sculpted. The gilded reliefs were modelled by Peter Clodt; the flat areas, painted by Carl von Neff.

To this central subject are linked, by means of an imperceptible transition, patriarchs, apostles, kings, saints, martyrs, and righteous folk, a pious crowd who form the court and army of Christ, and whose figures fill the voids of the archivolt. These figures are painted, not sculpted, on a gold background.

The arches of the side doors are topped by the tables of the law, by way of ornamentation, and a radiant chalice in marble and gold accompanied by little painted angels. When the doors of the sacred portal, which occupies the centre of this immense facade of gold, silver, lapis lazuli, malachite, jasper, porphyry, and agate, acting as a prodigious showcase of all the riches that human magnificence can bring together when uninhibited by cost, are closed; those mysterious silver-gilt doors with guilloché enamelling, which are sculpted, and hollowed out, and which are no less than thirty-three feet high by fourteen feet wide; one can discern amidst the glow, and framed by the most marvellous metal foliage which has ever surrounded the work of a brush, paintings representing busts of the four Evangelists, and full length figures of the Angel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary.

Yet when, during ceremonies of worship, the leaves of the sacred door are opened wide, a colossal Christ, in gold and purple, in the form of a stained-glass window at the far end of the sanctuary, is visible, raising his right hand to bless, in a pose wherein modern technique allies itself with the majesty of the Byzantine tradition. Nothing is more beautiful or more splendid than this image of the Saviour illuminated by gleaming rays as if from the depths of a sky now revealed to the eye via the arch of the iconostasis.

The darkness, full of mystery, which reigns in the church at certain hours further increases the glow and translucency of this magnificent stained-glass window, created in Munich.

Here I will trace the main partitions of the iconostasis: let me first describe the figures they contain, starting with the first pair located to the right of the visitor when facing the iconostasis.

First, there is Jesus Christ seated on a throne in the Byzantine style, he has a globe in his left hand and is blessing the onlooker with the other; to his right is Saint Isaac of Dalmatia unrolling a plan of the cathedral. These two figures were executed in mosaic, on backgrounds formed of small crystal cubes lined with pure gold, to warm and rich effect, like those mosaics we admire in Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, and at Saint Mark’s in Venice. A picture in precious stones should be set on a field of gold.

Saint Nicholas, bishop of Myra and patron saint of Russia, in a brocaded dalmatic, holding a book in his raised hand, occupies the third panel, on the right-hand side. Saint Peter, separated from Saint Nicholas by the door to the side chapel, ends the row. All these figures are due to Carl von Neff.