Théophile Gautier

Travels in Russia (Voyage en Russie, 1858-59, 1861)

Part IX: A Ballet in St. Petersburg, and Return to France

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

Chapter 20: A Ballet in St. Petersburg

(‘Éoline’ or ‘The Dryad’, a ballet in four acts by Jules-Joseph Perrot, music by Cesare Pugni, with Amalia Ferraris, on her début at the Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre)

The curtain, rising, reveals to the eyes of the spectator a mysterious subterranean kingdom which for sky has a vault of rock, for stars lamps, for flowers strange metallic crystallisations, for lakes dark waters in which blind fish swim, and for inhabitants, mountain gnomes whom a gang of human beings have come to disturb in their deep retreat. Joyful activity reigns within the mine; pickaxes pursue veins of ore amidst their dull matrix; cables are wound on winches; baskets come and go, and hods pour into the stoves, whose red mouths blaze fire, the treasure extracted from the rock. Barely-cooled ingots are shaped beneath the rhythmic blows of the hammers. The scene displayed is wholly charming.

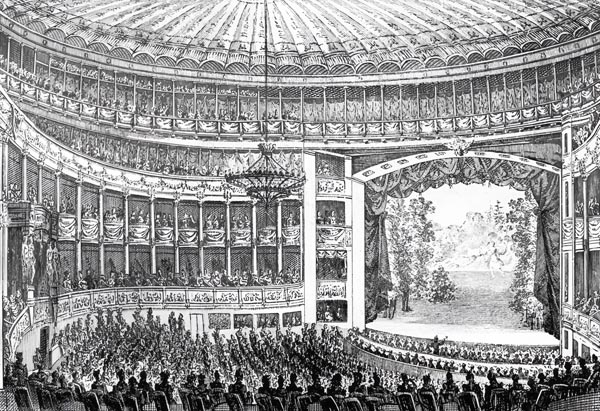

The Auditorium of the Bolshoi Theatre, 1820

Picryl

Such labour deserves its reward. By means of a frail staircase, whose summit is lost in the ceiling of the cave, and which allows the lower world to communicate with the upper, there descend, like the angels of Jacob’s ladder (see Genesis: 28), the wives, daughters and fiancées of the miners, in coquettish and picturesque costume, bringing lunch to those workers. All those little feet, all those rounded or slender legs navigate the innumerable steps of the staircase with winged agility, beneath a military onslaught of opera-glasses, without a false step, without hesitation, without the aerial staircase trembling for even a moment; there is nothing bolder or more graceful than this parade of the whole corps de ballet in mid-air.

The provisions are removed from the baskets, and Lisinka, the prettiest of these pretty girls, with a show of affection, attends to her father, the head of the miners, who is as skilled at finding metallic ore hid in its earthy envelope as the Telchines of Samothrace or the gnomes of the Hartz mountains. To complete their joy, Count Edgar, owner of the mine, has sent his brave workers pitchers of wine and jugs of ale. The miners draw heavily on these, and the sober lunch ends in festive cheer. In the light of the lamps, eyes sparkle, cheeks blaze, smiling mouths display gleaming flashes of white teeth, hands search out hands, arms clasp bodices, feet stamp on the ground which glitters with flecks of gold, and a dance soon begins.

This joyful tumult awakens, in the depths of his underground palace, Rübezahl, king of the gnomes, the resident spirit of the mountain whose realm these audacious and greedy mortals have invaded; an immense block of lava once liquefied in the fires of primeval volcanoes suddenly bursts open, and forth springs this supernatural being, half god, half demon, a short white mantle over his shoulders, wearing a breastplate and knemides (greaves) giving off metallic gleams, undoubtedly forged by Vulcan, his mythological ancestor. Rübezahl, irritated at first by all this noise, soon brightens on seeing the dancers and descends from his stony perch to mingle amongst them. Invisible at will, and therefore as unseen by them as if he were wearing the ring of Gyges (see Plato’s ‘Republic, Book II, 2:359a–2:360d’) on his finger, he circulates between the groups of dancers, whom he flirts with and troubles. Thanks to him, the most modest of the lads there are punished for a license they themselves have not taken. Here, he touches a pale shoulder with his lips; there, he wraps his fingers around a wasp-like waist; and intercepting his kisses in flight he lets them arrive as mere breaths of air... on innocent cheeks. That is far from all: for by spilling the red wine profusely, as he passes the amphoras, so denying it to the thirsty drinkers, he causes their toast to Count Edgar to falter on dry lips, to the great satisfaction of the evil genius, who disappears laughing.

Count Edgar now visits the mine to congratulate the workers for the ardour shown by their efforts, which are enriching him and allowing him to marry Éoline, his fiancée, the adopted daughter of the powerful Duke of Ratibor.

Éoline, curious to visit this subterranean world, soon arrives with her father, strewing beneath these dark vaults, which only gold, silver and precious stones adorn, flowers of the field, all wet with dew, that she has culled on the way; the dancers surround her, admire her, acclaim her; she is so beautiful, kind, and full of charm! Behind her beauty one admires another which seems to glow beneath the first, like a flame in an alabaster globe. It appears, from sudden phosphorescent gleams that envelop her, that Éoline is only the envelope, the transparent veil, of a superior being, a divinity condemned through some fatality to live among men. Edgar, intoxicated with love, hastens in the footsteps of his beautiful fiancée, trying to reach her and arrest her in flight. Have you seen a pair of butterflies with beating wings seeking and evading one another above the tips of the flowering stems, one passionately, the other coquettishly, forever keeping their distance till they meet in the same ray of light? Then, you have some idea of the delightful dance in which Amalia Ferraris — Éoline, I should say rather — appeared so young, so light, so airy, so voluptuously chaste and so modestly provocative. How lovely the movement with which she attracted and repelled the kiss hanging over her smiling lips like a gracious threat!

As Éoline continues to admire the mine’s riches, partakes of the refreshments offered to her, joins in the dances, welcomes the eager young girls around her, and receives indiscreet confidences offered by the young worker in love with Lisinka, Rübezahl, the mountain spirit, has reappeared; in an attitude of ecstasy, hands outstretched, eyes dazzled, he follows all the movements of Edgar’s fiancée. He is deeply intoxicated with her beauty. Never has a like marvel penetrated his dark kingdom; neither the undines of its interior, nor the salamanders of the plutonic regions who have sought to please him, possess that perfection of features and form, that virginal grace, that enchanting smile! Rübezahl is smitten with desire for Éoline; the arrow of love has pierced his heart through the dense layers of rock.

Suddenly he turns himself into a miner, and with an awkward and boorish air approaches the table, despite the sneers of the masters, whose jests he disdains. Beneath his humble clothes, he is more powerful than they; his eyes pierce obstacles which defy the gaze of men; he can see, most clearly, the veins of metal that run through their stony beds. He it is who holds the key to the mountain’s treasures; indeed, with each pickaxe blow he deals, the threads of native gold shine in yellow nuggets; the gems sparkle and gleam madly; the cavern, thus illuminated, reveals the riches men seek with such pain; the metallic blooms display their exotic colours, while rubies, sapphires, and diamonds mingle their varied flames. What is the treasure of the Caliphs next to these wonders, this efflorescence? In the humble miner, who bears himself so proudly, Rübezahl, king of the gnomes is revealed; unconcerned by Edgar’s wrath or by his sword, which only threatens the empty air, the spirit declares his love for Éoline. She shall be queen among the gnomes, and Earth will display all its treasures for her; so Rübezahl has decided, whom no obstacle will deny. Who can compete with a spirit, and especially one possessed of such wealth!

In vain Éoline protests, in vain Edgar seeks to chastise the insolent; Rübezhal is unmoved; he gestures, and the cave is bathed in purplish light, as if the wells that contain Earth’s inner fires have overflowed. The spirit disappears in the midst of flames. All flee in terror, and the mine is once more a solitude.

Once the humans have gone, the gnomes re-possess their realm. From gaps in the rock emerge a multitude of little beings all dressed in grey, from the depths of whose hoods shine cunning eyes. They leap about in bizarre fashion, in rhythmic disorder, to entertain their master, who seems troubled; to the gnomes succeed pretty creatures whose dresses glitter with metallic scintillations, who seek, in vain, to distract the mountain king from his reverie. Rübezahl even fails to pay attention to the antics of Trilby, his page, his beloved elf. The thought that preoccupies him is made visible behind the dark wall of the cavern; the compact rock becomes translucent, vaporises, turns a blue colour, and allows the audience to view, in magical perspective, the interior of a room of ogival architecture, by the soft light of a lamp, Éoline rests on a brocade coverlet, in the graceful abandon of sleep; a shaft of bluish light penetrates the chamber through the open stained-glass window. As the silvery glow touches Éoline, a metamorphosis transforms her; like a butterfly emerging from its chrysalis, the young girl quits her earthly form, leaving only a tangle of clothes on the bed. In the darkness of night, she becomes a Dryad, as her mother was before her; her companions surround her and guide her through her native forest towards the oak to which her life is joined. ‘Mortal or goddess, what matter!’ cries Rübezahl, I shall still win her love.’ The vision fades; the curtain falls.

In the following act, the pink glow of dawn, contesting the sky with the bluish light of the moon, plays on the high roofs of a Gothic mansion, the base of which is bathed by a stream. All the rest of the scene is as yet still in shadow, and in the foreground, near a ruined tower, an old oak-tree, split by lightning, displays its dead branches. This is the day of Edgar and Éoline’s betrothal. The miners prepare a throne adorned with flowers and foliage for the ceremony. ‘Let us fell this shattered tree, that stands in the way,’ Frantz, the lover of Lisinka, signs to old Hermann, the leader of the miners. ‘Be careful, my children,’ Hermann signs in reply, ‘a legend is attached to this oak: the chatelaine, Éoline’s mother, drawn to it as by a mysterious spell, loved to rest in its shade: one stormy day, lightning struck the tree, and, as if her life was linked to that of the oak, the young wife died.’

While the old miner is relating this tale, a crackling of sparks is heard, and Rübezahl rushes forth from the tower’s ruins as if in pursuit of a vision. Indeed, a luminous figure, whose reflection extends on the water, hovers above the stream, like a bird skimming over a lake; it is the Dryad, returning to her earthly form with the dawn.

The rising sun illuminates the facade of the castle, making the waters of the river gleam, and gilding the green foliage of the trees in the parkland; the workers, parading banners and symbols, bear heavy ingots of silver and gold as offerings to their lord; the young village girls follow on behind. Trilby, Rübezahl’s elf, disguised as a page to assist in his master’s affair, enjoys flirting with them, exciting the jealousy of their rustic lovers. The Duke of Ratibor, Éoline, Edgar, and the gentlemen who will witness the engagement soon appear; they take their seats and the event begins. A nobleman, exotically and magnificently dressed, steps boldly forward. His action excites a mixture of surprise of fear. He seems to possess a supernatural power, which subdues the will, shatters all resistance, fascinates like a serpent, and attracts one as does the abyss.

Entranced by his magnetic gaze, Éoline rises and begins to dance with him. Her movements are like those of a dove descending from branch to branch towards a snake motionless at the base of her tree, feathers ruffling, wings fluttering, distraught with horror, but spellbound. Éoline assuredly feels no love for Rübezahl, yet this magical dance stuns and intoxicates her; a perfidious languor pervades her actions, her head tilts, her eyes swim; their brightness increasingly moist, her lips opening smilingly, as she breathes more urgently. Half-overcome, she abandons herself to Rübezahl’s arms.

This dance sequence, which is a masterpiece, rendered the audience as ecstatic as those on stage. Count Edgar alone did not find it to his taste, and in truth was justified in feeling so. Furiously, dagger in hand, he rushed towards the pair; the king of the gnomes knocked him down with a flick of his arm, and returned to his cavernous realm via a trapdoor. The young girls received and supported the fainting Éoline.

The scene is now within the castle, a rich Gothic room, Éoline’s chamber; the young girl is sleeping, but her sleep is troubled by strange and fearful visions. She shivers and sits on the edge of the bed, thinking she hears laughter, and sees shadows passing by. This is not wholly an illusion, for Trilby, sent to spy on her, enters the room, and his malignant features appear between the curtains; however, surrounded by her chambermaids who have responded to her cries, Éoline feels reassured that she was but the victim of a dream! To dispel the unfortunate impression it has made, she runs to look in her mirror — is that not where women can forget everything, even love? — She smiles on seeing that the nightmare has not dimmed her eyes or made pallid her cheeks. Her women try to adorn her; but suddenly, instead of her charming image, the passionate figure of Rübezahl appears in the mirror, kneeling, stretching out his arms to her as if to draw her to his heart. Terrified, she takes a step back; the vision fades, but the amorous spirit bears away Éoline’s reflection with him. Unable to possess the body, he seizes the shadow; the faithless mirror no longer shows the young girl’s features. The image, however accurate it may be, fails to satisfy Rübezahl, he desires the original, and soon returns more vigorous, passionate, and ardent than ever; Éoline defends herself like a woman whose heart is another’s; however, her situation is perilous; Trilby dismisses her maids, and the spirit presses his attentions. The girl falls to her knees on a prie-dieu, in front of a sacred image, heaven alone can aid her. Midnight strikes; it is the hour of metamorphosis. A moonbeam traverses the room, and along this path of light the Dryad flies, leaving Rübezahl disconcerted and furious.

Warned that a bold fellow has entered Éoline’s chamber, Count Edgar hastens there, sword in hand, but the king of the gnomes, in anticipation, has called on the mysteries of electricity. His blade, upon meeting that of Edgar, raises blue sparks, and stuns his opponent’s arm; before the count can retrieve his useless weapon, the spirit vanishes.

It is a hard task, even for a king of the gnomes, that of pursuing a woman who exists in dual form, who escapes the moment he thinks he has her, and takes refuge in the trunk of a tree, at the heart of a vast forest. Rübezahl, despite his magic arts, is quite discomforted. Disguised as a woodcutter, he examines all the oak-trees, young and old. Beneath what protective bark is Éoline hiding? He knows not. An idea comes to him; he will interrogate every oak with his axe. As soon as the steel’s edge bites into each trunk, a dryad appears seeking mercy on behalf of the tree to which her life is linked.

Rübezahl continues his task until he has found Éoline’s oak. The unhappy Dryad resists for as long as she can; the axe sprinkles pink drops of blood from the sapwood over her delicate flesh before she is forced to emerge; the gnome threatens, if she continues to reject his love, to fell the tree completely which her being animates. Éoline, with suppliant grace, a modest display of coquetry, and submissive caresses, manages to disarm the wrath of this spirit. Her companions surround her, serving to mask her flight. Edgar, who has been searching for her, leads her back to the château.

In the weapons room of this manor-house, adorned with equestrian accoutrements, the celebrations for the wedding of Edgar and Éoline are to take place. Organ-notes issue from the neighbouring chapel, and soon the couple reappear, united forever before heaven and earth. Various dances follow one another. Éoline, in a supreme routine, expresses the chaste intoxications, the heavenly joys of consecrated love. ‘And Rübezahl, what does he do?’, you will ask. He allows the one he loves to wed his rival; it scarcely matters to the king of the gnomes! Wait: see there, in the background, that red glow which empurples the forest; billows of smoke swirl towards the sky, flames rise, the fire spreads, and the oaks, inhabited by dryads, twist painfully in the blaze.

Éoline leans backwards, puts a hand to her heart, and with the other waves farewell to Edgar. The fire which devours her oak-tree finally consumes it; she dies, and Rübezahl, suddenly appears beside her, grinning with diabolical wickedness: at least she will belong to no other.

A sky lit by apotheotic splendour, in the obligatory ending to ballets involving enchantment, now received the bodiless souls of the dryads. Éoline rose, sustained by her mother’s arms, and the curtain fell to the tumultuous sounds of a host of voices demanding Amalia Ferraris.

Her triumph was complete, and the Russians are strict judges where dancing is concerned; they have seen Marie Taglioni, Fanny Essler, Fanny Cerrito, and Carlotta Grisi, not to mention their own danseuses, that host of young performers who emerge from their Conservatory, one of the finest in the world, alert, flexible, wonderfully disciplined, talented and fully-trained, lacking only that on-stag experience which is readily acquired.

Amalia Ferraris is today without rival. She has grace, lightness, flow, the ability to float in the air and, beneath her charming exterior, incomparable strength and force. When she rises, a steel spring is released, when she descends, a dove’s feather falls. En pointe, the tips of her toes prick the stage like an arrowhead, and she turns, reverses, beats time obliquely, and performs sudden changes of pose with a perfect confidence, boldness, and abandon which might make one believe she was supported on invisible wings; each step is clear, exact, well-defined, and performed without stiffness or wavering, with classic perfection and a grace wholly new; moreover, those little feet, in the delirium of the dance, never forget the measure; they are finely attuned and maintain the rhythm to a marvel. Her rapid steps en pointe are as precise as the beats of Johann Maelzel’s metronome.

Charged with her dual role, Amalia Ferraris was able to reveal her talent, as if in two ballets played one after another, beneath two diverse physiognomies; as Éoline, she displays the gracious affability of a chatelaine with an air of innocent gaiety, and the naive coquetry of a young girl; as the Dryad, she appears idealised, detached, borne aloft, becoming yet lighter and more transparent, and flies through the oak-forest, over the tips of the grass-blades, without dislodging a single drop of dew from a violet-flower. In these sudden transformations from woman to divinity, from divinity to woman, she never errs, always fully inhabiting each change of character.

Though this critique is already quite long, to do the performance justice I would need a great deal more space. So many blue eyes and blonde heads of hair, so many charming feet and slender gleaming legs, floating, leaping, rising and falling, in that whirlwind of gauze, glitter, flowers, smiling lips, and pink tights that we call Éoline, or the Dryad! — Consider that, as a foreigner who arrived but yesterday, listening in charmed surprise to all those feminine names as strange to my ear as the song of an unknown bird, so sweet yet so full of musical vowels that one might take them for Sanskrit names from some Indian drama unknown to William Jones or Friedrich Schlegel: Prikhounova, Muravieva, Amosova, Koupeva, Liadova, Snetkova, Manarova... it was if I were transcribing for the dancers of the Rue Le Peletier (site of the Paris Opéra 1821-1873), and from the text of Sacountala (the ballet-pantomime of 1858, choreographed by Petipa, libretto by Gautier, music by Reyer, based on the classical Sanskrit play ‘Shakuntala’, by Kalidasa), all those beautiful blossoming names as fragrant as Indian flowers whose sonority so alarms them; consider, all the more readily as you know all that delightful world better than I; that each of these names means beauty, talent, or at the very least youth and hope — as for Maria Petipa (Mariia Sergeyevna Surovshchikova-Petipa, prima ballerina and wife of the choreographer Marius Petipa), her French surname (possibly derived from ‘petit pas’ or ‘small step’) should be a guide to her talent, although she is Russian, and I may say that she is especially fine, pretty, light-footed, and worthy of belonging to that family of distinguished choreographers (Marius Petipa’s father Jean-Antoine was also a renowned ballet-master). Is it really necessary to praise Jules-Joseph Perrot or Cesare Pugni? Their names alone are eulogies.

Chapter 21. Return to France

For many days, weeks, months even, I had postponed my departure for France. St. Petersburg as regards my willingness to leave, had become a sort of frozen Capua (Hannibal’s temporary retreat in Italy, a byword for decadence), where I luxuriated amidst the delights of a life of pleasure, and it pained me, I shamelessly admit, to contemplate returning to the journalist’s yoke, which had weighed for so long on my shoulders. To the great attraction of fresh experiences, was joined that of even more pleasing relationships. I had been pampered, celebrated, spoiled; even, I am foolish enough to believe, loved; and all this could not be abandoned without feelings of regret. Suave, caressing, and flattering, Russian life had enveloped me, and I had difficulty shedding that soft fur pelisse. However, one cannot remain in St. Petersburg forever. Letters from France, each one more urgent, had arrived, and the great day was irrevocably fixed.

I have said I was a member of the ‘Friday’ club of young artists who gathered every week on that day, now at one house, now at another, and spent the evening drawing, painting in watercolours, or flooding with sepia their improvised compositions which Begrov sold, who is the Susse of St. Petersburg (Michel Victor Susse and his brother Nicholas were art dealers in Paris, who also cast reproduction art bronzes, at the Susse Frères foundry), the profits from which aided whichever of their company was short of resources. Around midnight, a pleasant supper ended the evening’s labour; the pencils, brushes, and pastels, were removed and we attacked a classic macaroni made by ‘an Italian from Rome’, or tackled a ragout of grouse, or some large fish caught in the Neva through a hole in the ice. Dinner was more or less sumptuous, depending on the financial state of the member who was hosting the supper that evening. But whether accompanied by a Bordeaux wine, Champagne, or merely English beer, or even kvass, it was no less cheerful, cordial, and fraternal. Ridiculous tales, artistic jibes, amusing follies, and unexpected paradoxes, leapt forth like fireworks. Then we returned in groups, wending our separate ways through the neighbourhood, while continuing our conversations amidst silent and deserted streets, white with snow, where not a sound could be heard but our bursts of laughter, the howl of some dog awoken as we passed, or a night-watchman’s stick trailing along the pavement.

On the eve of my departure, which was a Friday, it was my turn to treat the assembled club, and the whole gathering arrived in force at my lodgings on Bolshaya Moskaya Street. Given the solemnity of the event, Imbert, a court-officer in charge of the imperial table, who was famous in St. Petersburg, wished to create the supper menu and, while supervising its execution, even deigned to involve himself in preparing a ‘hot and cold’ dish of partridge which I have tasted nowhere else. Imbert gifted me the recipe for a risotto, executed by myself in his presence, according to the purest Milanese recipe, after a conversation of ours about exotic cuisine; he declared it exquisite and no longer considered me a mere bourgeois; aside from my literary works, he also considered me an artist. No mark of approval ever flattered me more, and he had made this same dish for the palace, whose diners he considered capable of appreciating his merit.

As usual, the evening began with artistic toil; each sat at his desk, which had been prepared in advance, beneath the light of a lamp. But my efforts made little progress, I was preoccupied; conversation interrupted the strokes of the brush, and the bistre or the Indian ink sometimes dried in the tub between one touch and the next. For nearly seven months, I had lived a good companion of these spirited, amiable, young people, lovers of beauty and full of generous ideas. I was about to depart. When one leaves who knows if one will ever see one’s friends again? Especially when, separated by a wide distance, life must resume its habitual course. A certain melancholy therefore hung over the Friday club, which the announcement that supper was ready came, most conveniently, to dispel. The toasts to my safe journey revived the cheerfulness which had been extinguished, and so many stirrup-cups were drunk that they determined to stay till daylight and accompany me en masse to the station.

The season was advancing; the great thawing of the Neva’s ice had taken place, and only a few late ice floes were sailing downriver to melt in the warming gulf, now free for navigation. The roofs had lost their ermine cloaks, and in the streets, the snow, changed to black slush, had brought puddles and quagmires at every step. The ruins of winter, masked for a long time by a layer of white, were laid bare. The paving stones were out of kilter, the road surface broken, and our droshkys, bumping harshly from quagmire to quagmire, gave us terrible blows in the kidneys, and made us leap about like peas on a drum, for the poor road conditions in no way prevented the isvochtchiks from flying along as if the devil were carrying them off: provided that the two little wheels follow on behind, they are happy and care little for the traveller.

We soon arrived at the railway station, and finding that our parting came too swiftly upon us, the whole group clambered aboard the carriage, desiring to accompany us to Pskov, where a branch line terminated. This custom of accompanying parents, or friends, part-way on their journey seems peculiar to Russia, and I found the habit touching. The bitterness of departure is ameliorated, and hugs and handshakes are not followed by sudden solitude.

At Pskov, however, there was an obligatory parting of the ways. The Friday club members reversed direction, and headed for St. Petersburg by the return train; it was a final farewell, and my real journey was about to begin.

I was not returning to France alone; I had, as travelling companion, the young man who had lodged in the same house as I did in St. Petersburg, and with whom I had quickly became friends. Though French, he knew, and this is rare, almost all the Northern languages: German, Swedish, Polish, and Russian which was his maternal language; he had made frequent trips to all parts of Russia, by every means of transport, and in all seasons. As a traveller, he was admirably calm, knew how to do without everything, and showed an astonishing resistance to fatigue, although he was delicate in appearance, and accustomed to life’s many comforts. Without him, I would not have been able to accomplish my return journey at that time of year and by so difficult a route.

Our first task was to search Pskov for a carriage to rent or buy, and, after much toing and froing we found a single rather dilapidated droshky, the suspension of which inspired us with scant confidence. We purchased it, but on the condition that if it broke down before having gone forty versts the seller must repay its cost, while deducting a small amount for the damage. It was our prudent friend who added this clause, and well he did so, as we will see.

We strapped our luggage to the back of the frail vehicle, seated ourselves on the narrow folding-seat, and the driver set his team to the gallop. It was easily the worst time of year to travel; the road was merely a muddy causeway, only a little more compacted, relatively speaking, than the vast muddy swamp around. To right and left, and straight before us, the view consisted of a sky smeared with dirty grey, above a perspective of black and soggy terrain; with, here and there, a few reddish, half-submerged birch trees, gleaming puddles of water, and izbas (log cabins) their roofs still retaining a few patches of snow akin to shreds of badly-torn paper. Through the deceptive warmth, as evening approached, came the breath of a somewhat bitter breeze which made us shiver beneath our furs. The wind was not warmed by blowing over that mix of snow and ice; flocks of crows punctuated the sky with their black silhouettes, as they headed, croaking, towards their resting place for the night. The scene was scarcely cheerful, and, without the presence of my companion, who told me of one of his trips to Sweden, I would have fallen into a melancholy state.

Moujiks’ carts, carrying stacks of wood, followed the road ahead, drawn by muddy little horses splashing a deluge of mud around them; but hearing the bells attached to our team, they lined up, respectfully, to let us pass. One of these moujiks was honest enough to run after us and return one of our trunks which had come loose, the fall of which we had failed to hear above the noise of our wheels.

Night had almost fallen, and we were not far from the post-house; our horses galloped like the wind, excited by the nearness of the stables; the poor droshky was leaping about on its weakened springs, and was dragged along obliquely, its wheels not being able to turn quickly enough due to the thick mud. Encountering a large stone dealt it so violent a shock we were almost hurled into the midst of the quagmire. One of the springs had broken, the forepart was no longer attached. Our coachman dismounted, and mended the damaged vehicle with a piece of rope as best he could, so that we could hobble along to the relay station. The droshky had not lasted fifteen versts. It was unthinkable that we could continue the journey in such a tub. The post-house yard contained nothing better than a telega (cart), and we still had five hundred versts to travel, so as to reach the border.

To render all the horror of our situation clear, a brief description of the telega is necessary. This eminently primitive vehicle, consists of two planks placed lengthwise on twin axles each fitted with a pair of wheels. Narrow planks border the sides. A double rope, wrapped in sheepskin, attached to the sides, forms a sort of swing serving as a seat for the traveller. The postilion stands on a wooden crosspiece, or sits on a board. The luggage is piled up behind. Five little horses are attached to the thing, horses seemingly unfit to pull a carriage they look so pitiful standing there, yet which the swiftest racehorse would have difficulty keeping up with once they launch themselves. It is not a means of transport suited to sybarites, but the road was hellish, and the telega is the only vehicle that can withstand roads ruined by the thaw.

We held a council in the yard. My companion said: ‘Wait here. I’ll push on to the next relay, and return to collect you in a carriage.... if I can find one.’

— ‘Why so?’ I replied, surprised at his proposal.

— ‘Because,’ replied my friend, hiding a smile, ‘I’ve undertaken many a journey in a telega with companions who seemed brave and robust. They took their seats, proudly, and, for the first hour, limited themselves to a few grimaces, a few contortions immediately repressed; but soon, with bruised sides, sore knees, churned intestines, brains rattling in their skulls like nuts in their shells, they began to grumble, moan, lament, and shower insults on me. Some even wept, begging to be set down, and left in a ditch, preferring to die of hunger or cold on the spot, or be eaten by wolves than endure such torture a moment longer. None lasted more than forty versts.’

— ‘You’ve a poor opinion of me,’ I replied, ‘I’m no fragile traveller. The Cordoban carro, the floor of which is an esparto net; the Valencian tartana, akin to a box in which marbles are rolled to round them, never elicited a groan from me. I rode with the post in a cart, holding on hand and foot to the sides. There’s nothing astonishing to me about a telega. If I complain, you may answer me as Guatimotzin (the Aztec emperor Cuauhtémoc: see the opera ‘Guatimotzin’ by Aniceto Ortega del Villarto) did his companion, as they were being roasted: ‘And mine, is mine a bed of roses?’

My proud reply seemed to convince him. The horses were harnessed to a telega, into which we piled our trunks, and away we went.

And dinner? Allow me to say that Friday’s supper was now fully-digested, while the conscientious traveller still owes it to his readers to record the menu of the least meal eaten en route. We took no more than a glass of tea and a thin slice of brown bread; for when one is on one of these highly extravagant trips, one must not eat, no more than the postilions do who transport the post without leaving the saddle.

I would not wish to convey the idea that the telega is the most pleasant of vehicles. However, it seemed more so than I had expected, and I maintained myself without too much trouble on the horizontal rope, rendered a little more comfortable by its sheepskin wrapping.

With night, the wind had grown colder; the sky had cleansed itself of cloud, and the stars shone, bright and clear in the dark blue, as when the weather turns frosty.

Cold spells often occur during the thaw. The northern winter has scarcely retreated towards the pole before it returns to throw handfuls of snow in the face of Spring. Around midnight, the mud was already hardened, the puddles were frozen, and the telega threw up denser lumps of petrified mire than before. We arrived at the post- house, recognisable by its white facade and portico columns. All these relay stations are the same, built to the prescribed plan, from one end of the Empire to the other. We descended from our telega with our luggage, and clambered into another which immediately departed. We were travelling flat out, and the vague objects glimpsed in the shadows fled in disorder, on both sides side of the road, like a routed army. It was as if these phantoms were being pursued by an unseen enemy. Nocturnal hallucinations troubled my sleepy eyes, and dreams mingled, despite myself, with my thoughts. I had not slept the night before, and the urgent need to sleep made my head bob from one side to the other. My companion made me sit in the back of the cart, and I put my head between my knees to keep from splitting my skull against the sides. The most violent jolts of the telega, which, sometimes, on sandy or peaty stretches, ran over logs laid across the road, failed to wake me, but made my dreams go astray like a draughtsman’s line if his elbow is jogged as he is working: the design that began as an angel’s profile ends in a devil’s mask. This slumber lasted some three quarters of an hour; I woke rested, and as cheerful as if I’d slept in my bed.

Speed is an intoxicating pleasure. What joy compares to that of passing like a whirlwind, amidst the din of bells and wheels, in the depths of a vast noiseless night, in which all are at rest, seen only by the stars that blink their glittering eyes and seem to show one the way! The feeling of action, progress, one’s forward motion towards a goal, during hours usually lost to sleep, inspires one with an odd sense of pride: one is full of oneself, and looks down a little on philistines snoring beneath their blankets.

At the next relay, the same ceremony took place: a fantasy-filled entry to the courtyard and a swift transfer from one telega to another.

— ‘Well!’ said I to my companion, when we had left the post-house, the postillion having launched his horses at full speed down the road, ‘I’ve not begged for mercy, yet, and the cart has shaken me about for quite a few versts. My arms are still attached to my shoulders, my legs are not out of joint, and my spine still supports my head.’

— ‘I had no idea you were so seasoned to it. Now the worst is over, and I’ll not be forced to drop you beside the road, with a scarf on a pole, for you to flag down some berlin or post-chaise crossing the empty waste. But since you’ve slept, it’s your turn to watch; I’ll close my eyes for a while. Don’t forget, to maintain our speed, by prodding the moujik in the back so he whips up the horses. And shout durak (fool) at him in a loud voice, too; it can’t hurt.’

I carried out the task imposed on me, most conscientiously; but let me say, at once, so as to free me, in the eyes of philanthropists, from the reproach of barbarity, that the moujik was dressed in a thick sheepskin tulup whose fleece cushioned any external shock. My prods were as if aimed at a mattress.

When daylight dawned, I saw with surprise that during the night snow had fallen over the countryside we were about to travel through. Nothing was sadder than the sight of this snow, the thin layer only half-covering, like a shroud full of holes, the miserable, ugly ground soaked by the recent thaw. On the inclined slopes, narrow drifts rose and fell, vaguely resembling the columns of those Turkish tombs in the cemeteries of Istanbul, in Eyüp or Scutari (Üsküdar), which subsidence has caused to tumble or lean at strange angles.

After a while, the breeze began to whirl a kind of fine snow about, thin and pulverised like sleet, which stung my eyes, and riddled with a hundred thousand frozen needles the part of my face that the need to breathe had forced me to leave uncovered. It is hard to imagine anything more unpleasant than this relentless form of minor torment, which the speed of the telega further intensified in running against the wind. My moustache was soon studded with white pearls, and bristling with icicles, between which my breath rose, vaporous and bluish, like pipe smoke. I was frozen to the marrow of my bones, for a damp cold is more unpleasant than a dry one, and I felt that discomfort at dawn known many a traveller, and seeker of nocturnal adventure. However adaptable one may be, the telega, as regards restfulness is no match for a hammock, or even one of those green leather sofas one finds everywhere in Russia.

A glass of hot tea, and a cigar, smoked and consumed, at the relay while the horses were harnessed, and I returned to my perch, and continued valiantly on the way, bolstered by my companion’s compliments, who declared he had never seen a Westerner endure a telega so heroically.

It is quite difficult to describe the country we were travelling through, such as it appeared at that time of year to the traveller obliged to cross it for a compelling reason. The gently undulating plains, of a blackish hue, were punctuated by poles intended to mark the road when winter snows erase the paths, and which in summer must look like supernumerary telegraph-posts. On the horizon one saw only birch-forests, sometimes half-burned, or a rare village lost in the landscape, betrayed by a church with a small bulbous dome painted apple-green. At this season, over the depth of mud that the night-frost had solidified, snow was spread, here and there, in long strips like those pieces of canvas that are rolled out in the meadows for the dew to whiten, or, if that comparison seems too cheerful, white braiding sewn onto to the scorched blackness of a common funeral shroud. Pale daylight filtered through the immense bank of greyish cloud and covered the whole sky with its diffuse glow, but failed to illuminate objects or cast their shade; nothing was solid, every outline seemed filled with the same flat tone. In this doubtful clarity, all looked grey, soiled, pallid, and the colourist would have found no more material than the engraver, in that vague, indefinite, and drowned landscape, which seemed morose rather than melancholic. But what comforted me and relieved the monotony, despite the regret for St. Petersburg that filled me, is that my face was turned towards France. Every bump in the road amidst that dreary countryside brought me closer to my homeland, where I would quickly discover, after seven months of absence, if my Parisian friends had forgotten me. Besides the achievement of a journey painfully endured, and the satisfaction of triumphing over obstacles, distracted from these minor details. When one has viewed a number of countries, one no longer expects to encounter ‘enchanting sites’ at every step; one is accustomed to these gaps in nature which is sometimes repetitive, and nods, like the greatest of poets (Dryden’s ‘even Homer nods’ translating Horace: ‘Ars Poetica 359’). More than once, I was tempted to say, like Fantasio, in Alfred de Musset’s comedy of that name (see Act I Scene I): ‘How lacking is this sunset! Nature is pitiful this evening. Look for a moment at that valley over there, those four or five wicked clouds clinging to the mountainside! I drew landscapes like that when I was twelve years old, on the covers of my schoolbooks!’

We had long passed Ostrov, Rezhitza (Rēzekne, Latvia), and other towns or burgs of which, as one can imagine, I could make no close observation from the heights of my telega. I might have stayed longer and still been unable to do more than repeat descriptions already reported; for all these places are similar to one another: always plank fences, wooden houses with double windows through which one glimpses some exotic plant or other, roofs painted green, and a church, with five pinnacles and a narthex illuminated with some painting of Byzantine pattern.

In the midst of this stands the post-house, with its white facade in front of which are grouped a few moujiks in soiled tulups, and some fair-haired children. As for the women, one rarely encounters them.

As the daylight faded, it appeared we were not far from Dünaburg (Daugavpils, Latvia). We arrived there to the last gleams of a livid sunset, which gave to the town, populated largely by Polish Jews, a somewhat unpleasant aspect. It was one of those skies as conceived in paintings which depict times of plague, pale grey and full of morbid and greenish hues, like those of rotting flesh. Under this sky, the dark houses, soaked in rain or melting snow, dilapidated after the winter, looked like half-submerged piles of wood or flotsam in a sea of mud. The streets were veritable torrents of mud. Streams of meltwater flowed from all sides seeking an outlet, yellow, earthy, blackish, and carrying with them a thousand pieces of nameless debris. Excremental swamps spread over the ground marked here and there by a few islands of dirty snow still resistant to the westerly wind. Through this filthy mixture, which prompted one to sing a hymn in honour of tarmac, wheels churned, like the paddles of a steamboat in a silty river, splashing the walls and the rare passer-by booted like an oyster-fisherman. Ours sank up to the hubs. Fortunately, beneath the flood, the wooden paving-blocks survived and, though sunken in the wet, offered, at a certain depth, resistant ground which prevented our horses, carriage, and ourselves from disappearing as travellers do in the quick-sands around Mont Saint-Michel.

Our fur coats had become, beneath the upthrown water, true celestial planispheres, exhibiting many a muddy constellation unknown to astronomers, and if it was possible to look filthy in Dünaburg, we were, as they say, not even fit to be picked up with a pair of tongs.

The passage of isolated travellers was a rare thing at that time. Few mortals possessed the courage to travel in a telega, and the only possible vehicle was the mail-coach. But one had to register well in advance to book a seat, and I had departed abruptly, like a soldier who sees his hours of leave expiring and must at all costs rejoin his unit, under penalty of being branded a deserter.

Russian Telega used for haymaking, 1850

Picryl

My companion’s rule was that one should eat as little as possible when travelling in this manner, and his sobriety exceeded that of the Spaniards or the Arabs. However, when I declared that I was close to dying of hunger, having not attended to the needs of ‘the underside of one’s nose’, as Rabelais has it, since Friday night — it was now Sunday evening — he condescended to what he called my weakness, and, leaving the telega in charge of the relay-station, accompanied me in search of food. Dünaburg retires early, and the dark facades were only rarely illuminated — to walk through the cesspool was no easy thing, and it seemed to me that at every step an invisible hand grasped my shoe by the heel. At last, I saw a reddish glow emerging from a sort of den with the appearance of a tavern; rays of light extended over the liquid mud in red streams, like blood flowing from a wound. This was hardly wont to whet the appetite, but at a certain level of starvation one does not demur to eat. We entered without allowing ourselves to be deterred by the nauseating odour of the place, in which a smoky lamp crackled and burned with difficulty amidst the mephitic atmosphere.

The room was full of Jews of strange aspect, with long tight-chested Levitical garments like cassocks, which were sadly muddied, and of a colour which had once been black rather than purple, brown than olive, but which, at that moment, displayed a hue that I will designate as: ‘deeply soiled’ They wore exotic hats, with wide brims and tall circular crowns, but somewhat faded, battered, gleaming, and furred in places, bald in others, too worn even to be snatched from the corner of a mound by the hook of a bankrupt rag-picker. And the boots! The glorious Saint-Amand (the playwright Jean-Armonde Lacoste) himself would be needed to describe them! Worn-out, slumping, twisted in spirals, blanched by layers of half-dried stains, like to the feet of elephants that have waded for lengths of time in the jungles of India. Many among these Jews, especially the young, had their hair parted on the forehead, and hanging behind one ear a long, braided side-lock, a coquetry which contrasted with their general shabbiness. These were not the splendid Oriental Jews, heirs of the patriarchs, who retain its biblical nobility, but the wretched Jews of Poland, devoted, amidst the mud, to all kinds of vague activities and lowly industry. Yet, illuminated thus, their thin faces, their fine but anxious eyes, their beards forked at the ends like fish-tails, and their soiled clothing with the hue of a smoke-varnished cured herring, recalled Rembrandt’s paintings and etchings.

The consumption of food was scarcely apparent in the establishment. In dark corners, I discerned a few individuals drinking, at a slow pace, a glass of tea or vodka; but of solid eatables, not a sign. Understanding and speaking both German and the Polish dialect spoken by the Jews, my companion asked the proprietor if there was a way to provide us with a meal.

This request seemed to surprise him. It was the day after the Sabbath, and the dishes prepared on the Friday for the weekend, on which it was not permitted to do anything, had been devoured to the last crumb. However, our look of starvation moved him. His larder was empty, his stove unlit: but perhaps bread could be found at his neighbour’s house. He issued orders accordingly, and after a few minutes we saw a young girl, appear amidst this pile of ragged human beings, with an air of triumph, bearing a sort of flat cake, A Jewess of marvellous beauty, the Rebecca of Waltor Scott’s Ivanhoe, the Rachel of Eugène Scribe’s La Juive, a true sun radiating like the alchemist’s macrocosm in the darkness of that sombre room. Eliezer at the edge of the well would have presented her with Isacc’s engagement ring (see Genesis:24). She was the purest example of her people that one could dream of, a true biblical flower blooming, one scarcely knew how, on a midden. The Shulamite of the Shir Hashirim (The biblical Song of Songs) was no more orientally intoxicating. What gazelle-like eyes, what a delicately aquiline nose, what beautiful lips, of a hue like twice-dyed Tyrian purple, adorned the matt pallor of her face, a chastely elongated oval from temples to chin, made to be framed by the traditional headscarf!

She presented us with the bread, smiling, like those daughters of the desert who tilt their urn to the traveller’s thirsty lips, while, wholly occupied with contemplating her, I hesitated to take it from her. A faint blush rose to her cheeks on seeing my admiration, and she set the bread down at the edge of the table.

I heaved an inner sigh, on thinking that, for me, the age of passionate antics had passed. My eyes dazzled by that radiant apparition, I began to nibble the bread, which was both unleavened and burnt, but which seemed just as fine to me as if it had come from the Viennese bakery on the Rue de Richelieu (August Zang’s Boulangerie Viennoise, at no. 92, founded 1838/9.)

Nothing further detained us there: the lovely Jewess had vanished, making the smoky hue of the room appear darker still by her disappearance. So, I returned to our telega with a sigh, telling myself that it is not the velvet case, always, that contains the most beautiful Oriental pearl.

We soon arrived on the banks of the Dvina (the Western Dvina, the Daugava) which we were to cross. The river-banks are high, and we descended by a wooden ramp with a fairly steep slope to it, like that of a roller-coaster. Happily, the postilion’s sense of balance was wondrous, and the little Ukrainian horses sure-footed. We reached the bottom of the incline without incident, where we heard the waters bubbling and foaming in the shadows. Neither a boat-bridge nor ferry was used to travel from one bank to the other, but a system of plank-floored rafts abutting one another and linked by cables; they lend themselves better thus to the changing height of the water, rising and falling with it. The crossing, though without real danger, seemed quite sinister. The river, swollen by the melting snow, was running high, and drove against the obstacle presented by the rafts, stretching the cables. The river, the night, were easily rendered gloomy and fantastical. Streaks of light, issuing from who knows where, rippled like phosphorescent serpents, the foam glittering strangely and deepening the darkness; we seemed to be floating over an abyss, and it was with a feeling of relief that we found ourselves on the far side, drawn onwards by our horses, who climbed the ramp almost as rapidly as they had descended the opposite bank.

We coursed once more over the grey and black expanse, discerning mere shapes that faded swiftly from memory as soon as they had passed from sight, and which it is impossible to describe. Such obscure visions, that arise and vanish at speed, are not without charm: it seems as if one is crossing a landscape in dream, at the gallop. One would like to penetrate with one’s gaze the vague darkness, cottony like a piece of wadding, from which every outline fades, and on which every object merely shows as a somewhat darker blot.

I was thinking of the lovely Jewess, whose physiognomy I had engraved on my brain, like an artist who repeats an outline for fear of it fading, and I tried to remember how she was dressed, but without success. Her beauty had dazzled me so much that I only recalled her face. All else was plunged in shadow. The light had been focussed upon it, and if she had been dressed in gold brocade strewn with pearls, I would have paid it no more attention than a scrap of Indian cotton.

At daybreak, the weather changed, and winter had decidedly returned. Snow began to fall, but this time in large flakes. The layers overlapped, and soon the countryside was whitened as far as the eye could see. At every moment we were obliged to shake ourselves, so as not to be covered with snow, but it scarcely lessened the depth; and after a few minutes, we were powdered with white again like tartlets that a pastry-chef dusts. The silvery flakes, mingled, blurred, and rose and fell, with each breath of wind. It was as if someone had emptied innumerable feather-beds all over the heavens and, in that whiteness, one could not see even four paces ahead. The little horses, shook their dishevelled manes, impatiently. The desire to escape the turmoil gave them wings, and they galloped at full speed towards the relay station, despite the resistance offered to the play of the wheels by the freshly fallen snow.

I have an odd passion for snow, and nothing pleases me so much as that frozen rice-powder that whitens the brown face of the earth. That immaculate, virginal whiteness, in which particle glitter as in Parian marble, seems preferable to me than the richest of hues, and when one treads a road covered with snow, it is like walking on the silvery sands of the Milky Way. But on this occasion, I confess, my predilection was satisfied only too well, and my position on the telega was beginning to feel no longer tenable. My friend himself, impassive as he tended to be, and accustomed to the rigours of hyperborean travel, agreed that we would have been more comfortable by the corner of the stove, in a well-sealed room, and even in a simple post-chaise, if a berlin could travel in such weather.

The weather soon deteriorated, and we were amidst a snow-storm. Nothing could be stranger than a fluffy tempest of this nature. A level wind scours the earth, and sweeps the snow before it with irresistible violence. White smoke runs over the ground, swirling flakes freeze like vapour from some polar conflagration. When the drift meets a wall, it accumulates against it, soon tops it, and then cascades down the far side. In a moment, ditches and stream-beds are filled, the road disappears and is only re-discovered by virtue of the signposts. Were one to stop, one would be buried as if under an avalanche, in five or six minutes. Before the force of the wind, which transports this immense mass of snow, trees arch, poles bend, and creatures bow their heads. It is the khamsin of the steppe.

This time the danger was not great; it was daylight; the layer of snow that had fallen was not very dense, and we were granted the spectacle without the peril. But at night, a snowstorm can very well bear you away, and swallow you. Sometimes flights of rooks or crows driven by the wind, passed amidst this whiteness, like rags of black cloth, blown upside down and capsized as they flew. We also encountered a few carts led by moujiks seeking to return to their izbas and fleeing before the storm.

It was with great relief that, amidst the white-chalk cross-hatching all around us, I saw the post-house with its Greek portico looming at the edge of the road. No architecture ever appeared more sublime. To leap from the telega, shake the snow from our overcoats, and enter the room set aside for travellers, where a pleasant temperature reigned, was the matter of moments. At the relay-stations the samovar is in a constant state of boiling, and a few sips of tea, as hot as the palate could bear, soon restored the circulation of our blood, a little chilled by so many hours spent in the open.

‘I would undertake a journey of discovery with you to the Arctic pole,’ my friend said, ‘and I am sure you would make a fine winter companion. How charming it would be to live in an igloo, with a supply of pemmican and bear-meat!’

— ‘Your approval is touching,’ I answered, ‘since I know you’re no flatterer by nature; but now I’ve sufficiently proven my power to endure the bumps in the road and the cold, there’d be no cowardice, it seems to me, in seeking a more comfortable way of continuing our journey.’

— ‘Then, let’s go and see if there’s some vehicle in the courtyard less open to the rigour of elements. Needless heroism is simply a form of boasting.’

The courtyard, half-filled with snow, which we tried in vain to pile in the corners with brooms and shovels, presented an odd spectacle. Telegas (wains), tarantasses (unsprung, long-based four-wheelers), and droshkys, encumbered it, raising shafts like the spars and masts of half-submerged vessels. Behind all these primitive vehicles, we discovered, through a sea of white flakes that swirled in the breath of the storm, the leather hood of an old carriage much like the back of a whale stranded amidst the foam, which had an effect on us, despite its dilapidation, akin to encountering the ark of salvation. We stared at the carriage and, after towing it to the centre of the courtyard, could see that the wheels were in good condition, the springs quite intact, and if the windows failed to close completely, at least none were missing. To tell the truth, we would not have shone in the Bois de Boulogne in such an old jalopy; but since we were not required to circle the lake to excite the admiration of the ladies, we were most happy that the owner was prepared to rent it to us till we reached the Prussian border.

The installation of ourselves and our luggage in this clog only took a few minutes, and there we were, on our way once more, slowed a little, however, by the violence of the wind driving before it swirls of icy powder. Though we kept all the windows closed, there was soon a layer of snow on the seat we had chosen not to occupy. Nothing resists that impalpable, white dust crushed and kneaded by the storm: it enters through the slightest gap, like Saharan sand, and penetrates one’s very watch-case. But as neither of us were Sybarites, whining for a bed of roses, we enjoyed the relative comfort with deeply-felt pleasure.

One could at least support one’s back and head on the ancient green, padded interior, worn, it is true, but infinitely preferable to the side of a telega. Sleep no longer rendered one likely to fall and break one’s skull.

We profited from the situation to sleep a little, each in our own corner, but without yielding to too long a slumber, which is often dangerous in such low temperatures, for the thermometer had dropped to twelve degrees or so below zero under the influence of the icy wind. But, little by little, the storm subsided, swirls of snow suspended in the air fell to the ground, and one could see the landscape, as far as the horizon, now completely white.

The temperature rose, until there was scarcely more than three or four degrees of frost, which is wholly springlike for Russia at that time of year. We crossed the Vilia (Neris), which flows into the Niemen (Nemunas) near Kovno (Kaunas, Lithuania), by means of a ferry, which adjoined the low river-bank, and reached the town, which had an attractive appearance beneath the fresh fall of snow with which it was sprinkled. The post-house was located in a square with a fine aspect, surrounded by buildings in a uniform style, and planted with trees which, for a quarter of an hour at least, looked like constellations of quicksilver. Bell towers, of onion or pineapple shape, appeared here and there above the houses; but I had neither the time nor inclination to visit the churches they marked.

After a light collation of sandwiches, and a glass of tea, horses were set to the carriage so we might cross the Niemen by day; and the day is not long in February at that latitude. Several vehicles, telegas and carriages, crossed the river at the same time as us and, mid-passage, the yellow, bubbling water well-nigh reached the planked sides of the boats, which yielded under the pressure then reverted to shape again as the teams worked their way towards the far bank. If a horse had taken fright, nothing would have been likelier than our tumbling into the current, luggage and all; but Russian horses, though full of ardour, are very placid, and not alarmed by so small a matter.

A few minutes later, and we were galloping towards the Prussian border, which we thought to reach that night, despite the metallic moans and groans our poor carriage emitted which, though shaken about, nonetheless held together, refusing to yield like a coward on the way. Indeed, at about eleven o’clock, we reached the first Prussian post-station, where we relinquished the carriage to the relay we had employed.

‘Now there are no more acrobatic exercises for us to perform in impossible carts,’ said my friend, ‘it would be good to take supper at our ease, and round out our features a little, so as not to appear like spectres on arrival in Paris.’

You may imagine I made scant objection to this brief but substantial speech, which so well reflected my intimate thoughts. When I was but a boy, I imagined the borders of countries as marked on the ground in blue, pink or green, as they are on geographical maps. It was a childish and chimerical idea. But though it was not drawn with a brush, the demarcation line was no less abrupt and precise. At a point indicated by a post diagonally-striped in white and black, Russia ended and Prussia began, in a sudden and complete manner. The neighbouring country merged not with her, nor her with her neighbour.

We entering a low room furnished with a large tiled stove which crackled harmoniously. The floor was dusted with yellow sand; a few framed engravings adorned the walls; the tables and seats had Germanic shapes, and the serving-women who came to set the table were tall and strong. It was a long time since we had seen women busy with domestic cares which seem the prerogative of their sex in the West: in Russia, as in the Orient, it is the men who do the waiting-on, at least in public.

The cuisine was no longer the same. Shchi (cabbage soup), caviar, ogurcy (cucumbers), grouse, and sudak (pike-perch) were replaced by beer-soup, veal with raisins, hare with redcurrant jelly, and sweet German pastries. Everything was different: the shape of the glasses, knives, and forks, a thousand little details that it would take too long to list, revealed, at every moment, that we had changed country. With this copious meal, we drank a Bordeaux wine, which was excellent, despite its sumptuous label printed in gleaming metallic ink, and a glass of Rudesheim (Riesling) poured into emerald-coloured römers (drinking-glasses with wide bowls and short stems).

While dining we urged each other to temper our voracity so as not to die of indigestion, like those castaways some vessel rescues from a raft, their having consumed their meagre provisions of dry biscuit, their shoe-leather, and even the rubber of their shoulder-straps. If we had been wiser, we would have dined on a cup of broth and a piece of marzipan soaked in Malaga wine, so as to gradually accustom ourselves to food once more. But since our supper was already in our stomachs, we let it remain there, hoping it would cause us no remorse!

The modes of dress had changed too; we had seen our last tulups (sheepskins) in Kovno (Kaunas); and the facial types were no different to the clothing. Instead of the vague, pensive, gentle air of the Russians, here was the stiff, methodical, and gluttonous air of the Prussians – a wholly other people — the men with small peaked caps, rounded at the front, short tunics, trousers tight at the knee and wide in the leg, and a porcelain or meerschaum pipe in their mouth, or even an amber holder, bizarrely bent, in which a cigar was secured at right angles. Thus, the Prussians at the first post-house appeared to us: it was no surprise, since we knew them already.

The carriage we mounted resembled the little omnibuses that château-owners deploy to collect Parisians expected for dinner from the railway-station. It was suitably padded, well-sealed, and with a well-sprung suspension: at least it seemed so after the telega that we had left behind, which had well-nigh reproduced the torments of the strappado employed in the Middle Ages. What a difference too between the ardent pace of the little Russian horses, and the phlegmatic trotting of the large, heavy Mecklenburgers who seemed to be falling asleep as they went, and barely woke to a caress of the whip nonchalantly applied to their broad backs. These German horses doubtless knew the Italian proverb: Chi va piano va sano (‘who goes wisely goes well’). They meditate on it, raising their great hooves and ignoring the second part of the saying: Chi va sano va lontano (‘who goes well goes far’), since the Prussian post-stations are closer together than the Russian.

Nonetheless, one arrives, even if one does not travel quickly, and dawn found us not far from Königsberg (now Kaliningrad, Russia), on a road lined with tall trees which extended as far as the eye could see, and presented a truly magical scene. The snow had frozen to the branches and covered the thinnest ramifications with an extraordinarily-bright diamantine sheen. The alley looked like a long silver-filigree arcade leading to the enchanted castle of some Northern fey. We saw that the snow, knowing our love for her and given it was time to part from us, had lavished her magic upon us, and treated us to the most brilliant of spectacles. Winter had conducted us as far as he could, and had found it hard to leave us.

Königsberg is not an overly-cheerful town, at least at that time of year. The winters there are still rigorous, and the houses retain their double windows. We noticed several with stepped gables, their facades painted apple-green and supported by very elaborate S-shaped iron braces, as in Lubeck. It is Kant’s native place, he who with his Critique of Pure Reason, returned philosophy to its true path. I seemed to see him, at every street corner, with his steel-grey coat, his tricorn hat, and his shoes adorned with buckles, and thought of how his meditations had been troubled by the growth of some slender poplar trees, that were felled in order that he could see the old tower of Löbenicht church, on which, for more than twenty years, he had been accustomed to fix his gaze during his profound metaphysical reveries.

We went straight to the station, and each settled into a corner of the nearest carriage. It is not my intention to describe our journey by rail through Prussia; it contained little of interest, especially since the train does not halt at the towns, and we travelled straight to Cologne, where the snow finally left us. There, as our arrival and departure times failed to coincide, we were obliged to remain for a while, at which we took the opportunity to indulge in some essential cleansing and resume something of a human appearance, since we looked like true Samoyeds arriving on the Neva to market our reindeer.

The rapidity of our journey in the telega had caused a bizarre variety of damage to the contents of our trunk: the polish on our shoes had been rubbed away revealing the bare leather; a box of excellent cigars contained only polvo sevillano (a seasoning made from dried bitter-orange peel), for the jolting had reduced them to a yellow dust; and the seals on the letters we had entrusted to our trunk had worn away, having been filed down and thinned by friction, we could no longer distinguish neither coat of arms nor numerals, nor any imprint. Several envelopes had fallen open. There was snow between our shirts! Order restored, we retired to bed after an excellent supper, and the next day, five days after our departure from St. Petersburg, we arrived in Paris at nine in the evening, in accord with our prior commitment. We were not five minutes late. A coupé awaited us at the station, and a quarter of an hour later we found ourselves amidst old friends, including many a lovely woman, before a table glowing with candles, on which a fine supper was being served, and our safe return was celebrated, joyfully, till morning.

The End of Part IX of Gautier’s ‘Travels in Russia’