Théophile Gautier

Travels in Russia (Voyage en Russie, 1858-59, 1861)

Part II: Lübeck, The Baltic Crossing, St. Petersburg

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

Chapter 4: Lübeck

It was necessary to travel to Kiel to take the train. I made the journey by calèche without accident, other than a halt midway at the post-house to let the horses breathe. While partaking of a zabaglione (a drink or dessert with egg yolks, and sugar) made with beer, in the hotel, I noticed the Spanish name, Saturnina Gomez, engraved on the window with a diamond, which immediately set imaginary castanets playing in my mind. Doubtless, the woman who had written it must have been young and beautiful, and with that my brain began to devise the outline of a novella with which mingled memories of Prosper Mérimée’s Les Espagnols en Dannark (a satirical piece written in 1823-24).

In Kiel, the rain began to fall, light at first, then in torrents, which did not prevent me wandering, umbrella in hand, along its fine promenade by the sea, while waiting for the departure of the Hamburg train.

It was good to see the city of Hamburg again, and I amused myself by making another tour of its streets, so lively, vibrant, and of such picturesque appearance. As I wandered, I noticed a few small details that had previously escaped me: for example, iron-bound and padlocked wooden chests at the corner of the bridges, adorned with a painting in which, to excite the pity of the passer-by, were united, in a naïve manner, every imaginable accident at sea, with storms, lightning-bolts, fires, vast waves, sharp reefs, and an overturned vessel to the topmost spars of which sailors clung, representing amidst the foam the classic phrase from Virgil...Rari nantes in gurgite vasto (‘lone swimmers in the sea’s vastness’, see ‘Aeneid, I, 118’).

Often a sailor tanned by the suns of every ocean searched his tarred pocket and threw a schilling coin into the slot in one of these trunks, a little girl raising herself on tiptoe to watch his piece of small change drop into the opening — doubtless it added to an aid fund distributed to the families of shipwrecked mariners. This trunk, whose purpose was to collect alms for the victims of the sea, two paces from departing vessels about to run the dangers of the waves, had about it something religious and poetic. Human solidarity relinquished none of its members, and the sailor calmly departed.

Let me mention ‘beer tunnels,’ a species of underground tavern of a local nature. Drinkers descend a steep flight of steps, like barrels vanishing into a cellar, and sit in a fog of tobacco, where gas jets flicker at the rear of a small room with a low ceiling. The beer I drank there was excellent, since Hamburg is a city that thrives by consuming. The numerous delicatessens, whose displays exhibit edibles from all over the world, prove this by their abundance. There are many confectioners too. The Germans, especially the German women, have a childlike taste for sweets. These shops are highly frequented. One goes there to eat candy, drink syrups, and swallow ice cream as in cafés at home. At every step one sees shops-signs on which gleaming gold letters spell the word Konditorei; I doubt I exaggerate by assessing the number of Hamburg confectioners at three times that of their like in Paris.

Since the boat for Lübeck would not leave till next day, I went to dine at Wilkens’ Keller which I have mentioned previously. Wilkens, who is Hamburg’s equivalent to Collot (Étienne Auguste Collot owned ‘Les Trois Frères Provençaux’, a famous Parisian restaurant) runs a basement restaurant, with very low ceilings divided into decorative panels, with luxury rather than taste in evidence. Oysters, turtle soup, a fillet steak with truffles, and a bottle of Champagne supplied by the Widow Clicquot (Veuve Clicquot), composed the simple menu for my meal. The display board, following the custom of Hamburg, was burdened with more or less rare comestibles, and with early or late vegetables and fruits which did not yet exist, and have long not existed, for the masses. In the kitchen, we were shown large sea-turtles, in immense vats, who raised their scaly heads above the water, and seemed like snakes trapped between two plates. Their little horny eyes looked with concern at the light that shone on them, and their legs, similar to oars on the side of a drifting galley, made vague swimming motions, beneath the rims of their shells as if seeking to achieve an impossible escape. I hoped the same ones were not always shown to the curious, and that the creatures exhibited were sometimes replaced.

The next day I lunched at an English restaurant, in a glass pavilion from which one had a splendidly panoramic view. The river flowed majestically through a forest of ships with slender masts, of every size and tonnage. Steam-driven tugboats pounded the water, trailing behind them sailing-ships that the wind had failed to dispatch from the shore. Others, free to move, manoeuvred amongst obstacles with that precision which makes a steamboat seem an intelligent being endowed with a firm will and conscious of its own power. From this high viewpoint, the Elbe could be seen to widen, like any large river as it approaches the sea. Its waters, sure to arrive, were no longer in haste, and moved insensibly, in a placid manner like those in a lake; the far shore, quite low-lying, appeared green, and was dotted with little pink houses, half blurred by the vapour from the funnels. The golden shaft of a ray of sunlight traversed the plain; it was bright, broad, and superb.

In the evening the train brought me to Lübeck, through magnificent farmland, and summer-houses bathing their feet in dark water over which willows leaned. Hamburg’s Venice possesses its own equivalent to the Brenta canal, including villas, which though not designed by Michele Sanmichele or Andrea Palladio, made no less pleasant a sight, against the background of fresh greenery.

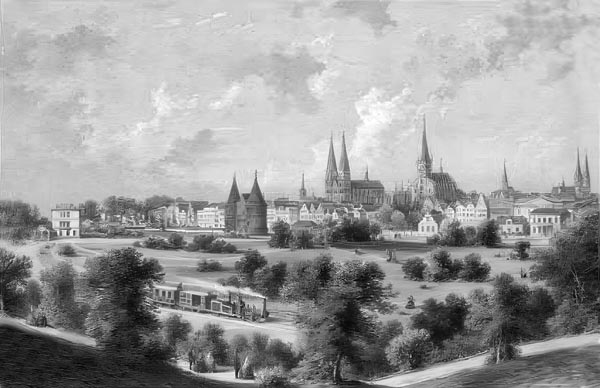

Lübeck - anonymous, 1860

Picryl

At the railway station, a special omnibus collected me, and bore myself and my luggage to Duffckes Hotel (in the Breite Strasse). Viewed in the darkness, by the vague glow of the lanterns, the city seemed picturesque, and in the morning, on opening the window of my room, I saw at once that I had not been mistaken. The house which faced me had an unmistakably German physiognomy. An extremely tall gable, denticulated in the ancient fashion, capped its facade. It had no less than seven floors, but the windows decreased in number towards the tip of the gable. The last floor displayed only a single dormer window. At each level, cross-braces, flourishing their ironwork, maintained the building and served for both support and ornamentation: a solid architectural principle that we greatly neglect these days. It is not by concealing but, on the contrary, by accentuating parts of the construction that we grant a building character.

This house was not the only one of its kind, as I was able to convince myself by taking a few paces along the street. The Lübeck of today is still, at least to the eye, the Lübeck of the Middle Ages, a town which, of old, headed the Hanseatic League: modern life is played out amidst its ancient decor; no one has altered the flats in the theatre-wings, or re-painted the back-ground scenery. What a pleasure to walk amongst the forms of the past, and to contemplate the dwellings, still intact, that vanished generations inhabited! — Without doubt, the living own the right to remodel their surroundings according to their habits, taste, and manners; but a new city is much less interesting than an old one.

When I was a child, I was sometimes given, at New Year, one of these Nuremberg boxes containing a miniature German town. I would arrange, in a hundred different ways, those tiny houses of carved and painted wood, around the little church with its pointed bell-tower and pink walls, the joints between the bricks marked by fine white lines. I would plant the two-dozen curly, painted trees, and admire what a delightfully strange and joyfully magical air they acquired, set on the carpet, those apple-green, pink, lilac, and reddish-white houses, with their neat little window-panes, their gables, stepped or scrolled, and their pointed roofs varnished a shiny-red; I thought such places could not exist in reality, and that the good fays made them for good little boys: the wonderful magnifying powers of childhood soon filled the colourful little city with mighty events, and I walked through the line of streets, with the same care that Gulliver took in Lilliput (see Jonathan Swift’s ‘Gulliver’s Travels’). Lübeck recreated, for me, that childhood feeling, long forgotten. It seemed as if I was walking amidst a town in some fantasy, one taken from a gigantic toy box — after all, I deserved some compensation for all the ‘tasteful’ architecture I had been forced to view in my life as a traveller!

At the entrance to the hotel, a frieze built into a wall caught my eye, ever in search of curiosities. Sculpture is quite rare in countries where brick abounds: this one represented a fairly crudely-worked group of Nereids or Sirens, but of an ornamental and chimerical character which gave me pleasure. They accompanied large coats of arms in the German style: an excellent theme for ornamentation if one knows how to employ it as the Middle Ages did.

A cloister, or at least an arcade, the remains of an ancient monastery, presented itself to me. This portico runs along one side of a square at the bottom of which rises the Marienkirche, a fourteenth century brick-built church. Continuing one’s walk, one soon find’s oneself in the market square, where one of those sights awaits one which reward the traveller for his many troubles: a building of a new, unexpected, and original aspect, the old Town Hall (Rathaus) where the Hall of the Hanse once stood, suddenly rises before one. It occupies two sides of the square at right angles. Imagine, if you will, in front of the Marienkirche whose spires and oxidized-copper roof protrude above it, a high brick facade, blackened by time, topped by three bristling pinnacles with pointed roofs in verdigris, pierced by two large open rose-windows without interior ribs, and emblazoned with crests, inscribed in the trefoils of its arches, displaying a black double-headed eagle on a shield of silver and red (the Lübeck coat of arms: ‘or, a double-headed eagle sable, overall an escutcheon party per fess argent and gules’), arranged alternately, and rendered in the proudest heraldic style.

To this facade is joined a Renaissance palazzino, fronting it, in stone and in a radically different style, whose greyish-white tones stand out wonderfully from the dark-red background of old brick. This palace, with its three scrolled gables; its fluted ionic columns; its Caryatids or rather Atlases (since they are male); its semi-circular windows; its rounded shell-topped niches; its gallery pierced by pedimented triangular bays, the arches decorated with figures, its base faceted in low relief; produces a most unexpected and charming architectural dissonance. Only a very few buildings of this style and period are met with in the North. The Reformation could scarcely accommodate such a return to pagan ideas and classical forms, modified by a graceful fancy.

In the facade at right angles to the first, the old German style regains its rights; brick arches set on short granite columns supports a gallery with ogival windows, with, above them, a row of coats-of-arms, each inclined to the right, their coloured enamel highlighted against the blackish tint of the wall. One cannot imagine how much character and richness this simple ornamentation possesses.

This gallery is joined to a taller building of which it might be said that a fanciful theatre-designer, looking for a suitable backdrop depicting the Middle Ages, for some opera, could scarcely invent one more singular or picturesque. Five turrets, topped with candle-snuffer spires, crown, with their sharp points, the line of the façade, fenestrated by round windows set above high pointed ones, some open, the majority unfortunately blanked-out, doubtless due to whatever interior alterations have been made. Eight large roundels, each with a gold background, four displaying radiated suns, two showing double-headed eagles, and two the silver and gules of the coat of arms of Lübeck, magnificently adorn this bizarre architecture. Lower, a line of square windows, with rows of small glass panes fills the width of the façade. At the base, arches, on squat pillars, reveal dark open mouths, from the depths of which the clocks and watches of goldsmiths’ shops vaguely sparkle.

Turning towards the square, one sees, above the houses, the green spires of another church and, above the heads of the tradespeople selling their fish and vegetables, the silhouette of a small building with brick pillars, which must have, in its time, been a pillory. It adds a last touch to the utterly Gothic physiognomy of the square, which is free of any modern buildings.

The bright idea came to me that this splendid Town Hall ought to possess another facade, and, in fact, passing under an arch I found myself in a main street, and there my admiration was again aroused. Five pinnacles, half-engaged in the wall, and separated by long ogival partially-obstructed windows, repeated, with variations, the facade I have just described. Rosettes of bricks displayed curious designs, in squares, like pieces of tapestry. At the foot of the dark building, a pretty Renaissance cubicle, of later date, served as an entrance to an exterior staircase, rising along the wall in a diagonal line to a sort of mirador, or overhanging balcony, in delightful taste. Charming statues of Faith and Justice, gallantly draped and accompanied by their attributes, decorated the portico.

The staircase, carried on arches whose openings grew larger as it rose, was adorned with Caryatids and Mascarons (grotesque heads). The mirador, set above the ogival door leading to the Market Square, was crowned by a pediment with indented ornamentation and volutes, and in a niche the figure of Themis, goddess of Justice, holding a pair of scales in one hand, and in the other a sword, though without neglecting to display her draperies in a coquettish manner. A bizarre architectural order formed of fluted pilasters, fashioned like herms, and supporting busts, framed the windows of this aerial cage. Chimerical consoles, adorned with stone masks completed the elegant ornamentation over which Time had passed its thumb just sufficiently to give the sculptures that blurred surface that nothing can reproduce.

The building continued, simpler in architecture, and decorated with a stone frieze depicting masks, figurines and foliage, though eaten-away, blackened, and dirtied, even the largest features, beyond recognition. Under a porch supported by Gothic columns of bluish granite, before the doorway, I noticed two benches whose exterior armrests were formed of two thick bronze panels, the one representing an emperor with a crown, globe, and raised hand of justice; the other a savage creature, hairy as a wild beast, armed with a club and a shield displaying the coat of arms of Lübeck, all of ancient workmanship.

The Marienkirche, which is located, as I have said, behind the Town Hall, is worth a visit. Its two main bell-towers are four hundred and ten feet high; and another elaborate bell-tower rises from the crest of the roof, at the point of intersection of the transept. The bell-towers of Lubeck offer this peculiarity that they seem out of balance and to tilt to right and left in a subtle manner, without however disquieting the eye as does the Asinelli tower in Bologna, or the Leaning Tower of Pisa. When I was a little distant from the city, the bell-towers, inebriated and tottering, with their pointed caps which seemed to salute the horizon, offered a strange and delightful silhouette.

On entering the church, the first curious thing one encounters is an old copy (by Bernt Notke) of the Totentanz, or Dance of the Dead, from the Basel cemetery. There is no need to describe it in detail. The Middle Ages embroidered countless variations on that macabre theme. The main variants are brought together in this mournful painting covering all the walls of a chapel. From the Pope and the Emperor to even the child in the cradle, each human being takes their turn dancing with the inevitable scarecrow. But Death is not represented by a white skeleton, polished, cleaned, and articulated with joints of copper, like the skeleton in an anatomical display; that would be too pretty a look for old Mob (a female personification of Death; see Edgar Quinet’s prose-poem ‘Ahasuerus’, 1834, in which he appears to coin the name, perhaps prompted by Shelley’s poem ‘Queen Mab’ in which Ahasuerus, the Wandering Jew also appears, though Mab, the Queen of Faerie, is not there associated specifically with death) who appears as a corpse in a more or less advanced state of decomposition; remnants of hair bristle on the skull, blackish soil fills the half-empty eyes, the skin of the chest hangs like tattered cloth; the flat stomach clings hideously to the vertebrae of the spinal column, and the tendons, bared, hang about the shins like broken strings from the neck of a violin; not one of the awful secrets stolen from the privacy of the tomb has been passed over in silence.

— The Greeks respected Death in modest style, presenting ‘him’ simply in the form of a lovely sleeping youth; but the Middle Ages, of a less delicate temperament, tore off the shroud and showed Death’s nakedness, in all its horror and wretchedness, with the pious intention of edifying the living. In this mural painting, Death has so little shaken off the black humus of the pit that an inattentive eye might take him for a black and bony African.

Very rich and ornate tombs, attached to the walls or suspended on massive pillars, with allegorical statues and their attributes; coats of arms; and lengthy epitaphs; formed a sepulchral chapel, as in the Dei Frari church in Venice (the Basilica di Santa Maria Glorioso dei Frari), granting the Marienkirche an interior worthy of Johan Peter Neef, the artist whose paintings depict many a cathedral.

The Marienkirche contains two paintings by Johan Friedrich Overbeck, The Descent from the Cross and The Entry into Jerusalem, which are much admired in Germany. One finds therein the pure religious feeling, the sweetness and unction of a master, which its affectation of archaism and deliberate naivety spoils as far as I am concerned. Otherwise, the delicacy of execution shows that Overbeck studied the charming primitive painters of the Umbrian school; in his talent as in his painting Italia und Germania, in the Pinakothek in Munich, blonde Germany seeks from dark-haired Italy the secrets of her art.

There are also various paintings of the older German school, among others a triptych by Jan Mostaert, my examination of which had to be abandoned so that I might, at the urging of a beadle desiring a contribution, plant myself at the foot of one of these extremely complicated mechanical clocks which show the course of the moon, the sun, the date in the year, the day of the month and even the hour, so that I might view a parade of seven gilded and painted wooden figurines, representing the Seven Electors, in front of a statuette of Jesus Christ in His Glory. On the stroke of noon, a door opens, and the Electors advance, on a semi-circular track, each in turn nodding his head with so sudden and energetic a movement that, despite the holiness of the place, it is hard to refrain from smiling. The performance complete, each figurine jerks its head and disappears through a second door.

The cathedral, also called the Dom, is quite remarkable inside. In the centre of the nave, filling the entire arch, is a colossal Christ, in Gothic style, nailed to an openwork cross adorned with arabesques; the foot of the cross rests on a transverse beam stretching from one pillar to the other, and burdened with holy women and pious characters in attitudes of adoration and pain; on each side, Adam and Eve are dressed, as decently as possible, in costumes of the earthly paradise; the base of the cross is a most ornate and foliate pendant or keystone, serving as the support for an angel with extended wings.

This suspended construction, despite its volume appearing quite light to the eye, is made of wood and carved with much art and taste. I cannot better define it than by terming it a portcullis of sculptures half-lowered in front of the choir. It is the first example I have seen of such a work.

Behind it, rises the rood screen pierced by three arches, with its gallery of statuettes, and a mechanical clock where the hours are struck by a skeleton and an angel bearing the Cross. The baptismal font is small, but formed like a building elaborately adorned with rows of Corinthian columns, whose interstices reveal a group of Jacob wrestling with the Angel. The cover is formed by the dome of this building, which is raised by a cord suspended from the vault. I will say nothing as regards the tombs, funeral chapels, and organs; but I will say a few words about two old fresco or tempera paintings accompanied by a long inscription in Latin pentameter verse, in which one sees a miraculous deer released by Charlemagne, with a necklace bearing the date of his release, slain four or five hundred years later by a hunter (Henry the Lion, third Duke of Saxony) who began to build the church which stands today at that very place.

The Holstentor Gate, a stone’s throw from the embarkation point, is one of the more curious and picturesque specimens of German architecture of the Middle Ages. Two enormous brick round-towers are connected by a central building in which a curved arch opens, such is the rough plan. But it is harder to appreciate the effect produced by the tall summit features of the central facade, the conical roofs of the towers, the fanciful dormer windows (lucarnes), and the dark-red and purplish tones of the crumbling brick. It would offer a completely new program for painters of architectural studies who should be dispatched to Lübeck by the next convoy. I also recommend five or six old houses in crimson brick, to them, positioned quite near to the Holstentor, beside the bridge, on the left bank of the Trave; they stand shoulder to shoulder as if to support themselves, bellying outwards and out of true, perforated with six or seven windowed floors, and with denticulated gables, trailing reddish reflections in the water like red aprons being washed by a serving-maid. What a painting Jan Van den Heyden would have created, with these as his subject!

Following the quay, which runs alongside a rail line along which freight-wagons roll, one enjoys the most entertaining and varied views. On the far bank of the Trave, amidst houses and clumps of trees, ships and boats can be seen at different stages of construction. Here one glimpses a carcass with wooden ribs, like to the skeleton of a stranded sperm-whale; there a hull covered with its planking, near to which smokes a cauldron of caulking tar, releasing pale clouds of vapour. Everywhere is the joyous turmoil of human activity. Carpenters hammer in nails, porters roll barrels along, sailors swab the decks of various vessels, or half-raise the sails to dry them in the sun. A boat on arrival lines up alongside the quay, moving the flotilla apart somewhat for a moment to allow itself passage. Steamboats raise or emit steam, and when one turns towards the city, above the ships’ rigging, one sees the bell-towers of the many churches gracefully rising like the masts of clippers.

The Neva, which was to transport me to St. Petersburg, was quietly being loaded with various crates and bundles, and seemed in no way prepared to leave on the day indicated. In fact, she was not ready to sail until two days later, a delay which would have been irritating if I had been in a less charming city and which I took advantage of by attending a performance of Mozart’s Don Juan, sung in German by a German troupe. The town’s theatre is brand-new and very pretty; the windows of the facade are supported by Muses arranged as Caryatids. I was less happy with the way Mozart’s masterpiece was executed so near to his homeland. The singers were mediocre, and they allowed themselves strange acts of license, for example, replacing many instances of recitative with lively and animated dialogue, probably because the music seemed to them detrimental to the story. Leporello indulged in various pieces of stage-business which were in very bad taste, and displayed beneath the weeping Elvire’s nose an endless strip of paper on which were pasted silhouette portraits of the ‘thousand and three’ victims of his master, the portraits, all similar, depicting a woman with the ‘giraffe’ hairstyle fashionable in 1828! (Note Nicolas Hüet’s ‘Study of the Giraffe Given to Charles X by the Viceroy of Egypt, 1827’. The first giraffe seen in France, a female, she caused a sensation, and led to a whole range of fashions based on her appearance). It was not a particularly imaginative performance!

Chapter 5: The Baltic Crossing

The Neva left at the appointed time, moderating its speed to follow the windings of the Trave, whose banks are populated with pretty country-houses, the retreats of the richer inhabitants of Lübeck. As it approaches the sea, the river widens, the banks are lower, and buoys mark the channel ahead. I liked the flat landscape: it is more picturesque than one might think. A tree, a house, a bell-tower, a boat’s sail, take on extreme importance, and suffice with their vague and fleeting background as a motif for the painter’s art.

On the thin line of horizon, between the pale blue of the sky and the pearly grey of the water, rose the silhouette of a city, or a large town, probably Travemünde, then the banks spread further and further apart, diminished, and disappeared. Ahead of us, the water took on greener hues; the undulations, weak at first, gradually swelling, became waves; the crests of these were like sheep shaking their wool made of foam. The horizon was sealed in a sharp blue line like some signature-flourish of the Ocean. We were at sea.

Painters of seascapes seem intent on depicting transparency, and when they succeed, the term transparent is applied to their work as a laudatory epithet. The sea, however, is distinguished by its heavy, dense appearance, almost solid, and particularly opaque. It is impossible for an attentive eye to confuse its deep and powerful waters with fresh water. Certainly, when a ray of light strikes a wave, partial transparency may be revealed, but the general tone is nevertheless dull; the sea’s local power is such that the neighbouring areas of sky appear darker. By the depth of colour, the intensity of hue, one perceives a formidable element, of irresistible energy, of prodigious mass.

When you set out to sea, it creates a certain solemn impression, even among the most frivolous, the most courageous and those most accustomed to the experience; you leave the shore where doubtless death can surprise you, but where at least the ground does not open beneath your feet, so as to criss-cross an immense salt plain, the epidermis of the abyss, which hides so many lost vessels. You are separated from the bubbling chasm only by thin planks, or weak plates of sheet-metal, that a wave, or a reef can tear open. A sudden breeze, a shift in the wind, is enough to capsize you, and then your ability to swim serves only to prolong your agony.

The indefinable effects of seasickness soon add to your serious thoughts; it seems that the affronted element wishes to reject you like some impure thing, and cast you among the algae on its shores. Your willpower vanishes, your muscles loosen, your temples tighten, a migraine possesses you, and the air you breathe acquires a nauseating bitterness. Your livid, green face has lost all composure: your lips turn violet in hue, and the colour leaves your cheeks to take refuge in the tip of your nose. You resort to your small pharmacopoeia; this person crunches candy from Malta; that one bites on a lemon; a third resorts to English smelling-salts; others beg for a mug of tea that a roll or pitch of the vessel makes them spill down their front; the bravest stagger about chewing on the butt of a cigar they neglect to light; almost all unite in leaning on the rail; happy are those who have sufficient presence of mind to face the leeward side.

However, the deck continues to rise and fall, with increasingly substantial movements. If your eye juxtaposes the horizon line and the masts and chimney of the steamboat as it climbs and falls, you perceive a difference in level of several meters, and your discomfort grows. Around you, the waves pursue one another, swell and burst, and spring forth in foam; the rising water leaps amidst a dizzying tumult; wave-packets sweep the deck, where they turn to a salty rain, which flows through the scuppers, having dealt the passengers an unexpected shower. The breeze freshens, the ropes through the pulleys make a sharp whistling sound like the cry of a seabird. The captain declares that the weather is favourable, to the great astonishment of naive travellers, and orders the hoisting of the jib-sail, since the wind that had stalled is now blowing freely and in a useful direction. Steadied by its jib-sail, the ship pitches and rolls to a lesser degree and picks up speed. From time to time, other boats, and brigs, pass more or less closely, under jib, their topsails furled, and with a reef in the lower sails, plunging their noses into the foam, performing a Pyrrhic dance which leads you to believe that the sea is perhaps not as benign as is claimed.

Tearing you away from your contemplation, a cabin-boy arrives to notify you that dinner is served. It is not an easy thing to descend to the captain’s cabin by a staircase the steps of which shift under your feet like the rungs of the mysterious ladder in the trials Freemasonry demands, and whose walls strike you as racquets do a shuttlecock. At last, you take your place among a few intrepid people. The rest lie on deck wrapped in their coats. One eats, searching with one’s lips, and risking blinding an eye on the prongs of one’s fork, as the ship dances ever more vigorously. When you try to drink, in itself a balancing act, your beverage performs, of itself, that comedy by Léon Gozlan: A Storm in a Glass of Water (first performed in Paris in 1849).

This difficult exercise complete, one returns to the poop-deck somewhat on all fours, and the cool breeze grants you fresh heart. You risk a cigar; it doesn’t taste too foul, you are safe. The sullen sea gods will no longer demand your libations!

As you walk the deck, legs straddled, swinging your arms, the sun descends into a bank of grey clouds whose vapours redden, and which the wind soon sweeps away. The horizon is empty, except for the silhouettes of ships. Beneath the pale violet sky, the sea darkens and takes on sinister tones; later, the purple turns to a steely blue. The water is utterly black, and the crests of foam, there, glisten like the silver ‘tears’ on a funeral drape. Myriads of greenish-gold stars punctuate the immensity, and the comet, trailing its huge mass of hair, seems to wish to plunge its head in the sea. For a moment its tail is severed by a narrow line of transversely-interposed cloud.

The limpid serenity of the sky did not prevent the breeze blowing hard, and a chill gripped me. My clothes were being penetrated by a bitter drizzle raised by the wind from the crest of the waves. The very thought of returning to my cabin and breathing its hot mephitic air raised my spirits, and I went and sat by the steamboat’s funnel, pressing my back against its hot sheet-metal, sufficiently sheltered by the paddle-boxes. It was not till deep in the night that I regained my cabin to doze, my sleep troubled, and traversed by extravagant dreams.

In the morning, the sun opened a dull eye, like someone who had slept badly, pushing aside with much difficulty the curtain of fog. Pale yellow rays pierced the vapour, and traversed the clouds, like the golden rays of glory in some religious painting. The breeze was freshening, and the vessels that showed, from time to time, elsewhere on the horizon, described strange parabolas. Seeing me stagger across the deck like a drunken man, the captain felt obliged to say: ‘Fine weather!’ doubtless to reassure me. His strong German accent nevertheless granted his sentence an ironic meaning.

I descended to lunch. The plates were held in place by little strips of wood, the carafes and bottles securely moored; without which the place-setting would have cleared itself away of its own accord. To serve the dishes, the cabin-boys indulged in strange gymnastics; they looked like acrobats balancing chairs on the tips of their noses. Perhaps the weather was not quite as fine as the captain had claimed.

Towards evening, the sky clouded over, and rain fell, lightly at first, then more heavily and, in accord with the proverb: ‘A little rain conquers a great storm,’ the bitter chill produced by the breeze was greatly diminished. From time to time, the red or white beam, glaring or in eclipse, of a lighthouse shone in the gloom, indicating the coast to be avoided. We had entered the Gulf of Finland.

When day dawned, low flat land, forming an almost imperceptible line between the sky and water, which with the naked eye might have been taken for morning fog or spray from the waves, appeared on our right. Sometimes the shore itself, due to the slope of the waves, was invisible; rows of half-faded trees seemed to rise from the water. The same effect was apparent as regards the houses, and lighthouses whose white towers I often confused with sails. On the left, I could see an islet rocky and barren, or at least so it appeared from a distance. A fairly large congregation of boats animated its shores, and, before having recourse to a telescope, I at first mistook their sails oriented to the rising sun, and set against the purplish depths of its bays, for the facades of buildings; but, with a clearer view, I could see the isle was deserted and contained no more than a lookout-cabin erected on a slope.

The sea had calmed somewhat, and at dinner, from the depths of their cabins, the figures of unknown passengers, of whose existence I had been unaware, emerged like ghosts from their tombs. Pale, starving, tottering, they dragged themselves to the table; but despite that not all dined: the soup was still too stormy, the roast too tempestuous. After the first mouthfuls, most of them rose and staggered towards the stairs to the hatch.

A third night extended its sway over the waters; it was the last I would spend aboard, since on the next day, at eleven, if nothing hindered the ship’s progress, we would have sight of Kronstadt. I stayed late on the poop-deck, gazing into a darkness dotted here and there with the red gleams of lighthouses, devoured by feverish curiosity. After two or three hours of sleep, I returned to the deck, anticipating the dawn’s arrival, a dawn still lazing in bed that day, at least to my mind.

Who has not experienced the discomfort of that hour preceding dawn? One is wet, icy, shivering with cold.

The robust feel a vague anxiety, those still suffering feel faint, the sense of fatigue seems heavier; the phantoms of the dark, the nocturnal terrors seem, as they flee, to brush you with their chilly batlike wings. One thinks of those who are no more, of those who are absent; melancholic thoughts stir, one misses one’s home though voluntarily abandoned; but, with the first ray of light, all that is forgotten.

A steamboat, trailing after it a long low plume of smoke, passed to our right; it was heading westwards, and came from Kronstadt.

The gulf narrowed more and more; reefs at the water’s edge were revealed, sometimes bare, sometimes covered with dark vegetation; lookout towers started to emerge; ships and boats were sailing to and fro, following a channel marked by buoys and poles. The sea, shallower, was of a different hue in the vicinity of land, and seagulls were glimpsed performing graceful evolutions in flight.

Through the telescope, I could see before me two pink blotches punctuated with black, a gleam of gold, a gleam of green, a few tenuous threads like spider threads, a few spirals of white smoke rising through the still air of a perfect purity: it was Kronstadt.

In Paris, during the war, I saw many more or less fanciful plans of Kronstadt, with the crossfire from cannons represented by multiple lines, like rays from a star, and made great efforts to imagine the true appearance of the city, but without success. The most detailed plan gives not the slightest idea of the town’s actual silhouette.

The blades of the paddle-wheels stirring calm, well-nigh dormant water, drove us on swiftly, and I could already clearly distinguish a rounded four-story fort with embrasures on the left, and on the right a square bastion commanding the entrance-channel. Low batteries could be seen at the water’s edge. The yellowish gleam transformed itself to a golden dome of magical brilliance and clarity. All the light was focused on the salient part while the shaded areas took on amber tones of incredible subtlety; the greenish gleam was a dome painted a colour that might have been taken for oxidised copper. A golden dome, a green dome: Russia, at first sight, showed itself to me in characteristic hues.

On a bastion stood one of those large masts for signal flags which are so effective in naval manoeuvres, and behind a granite mole ships-of-war were massed being readied for over-wintering. Many vessels, flying the colours of all nations, cluttered the port and formed, with their masts and rigging, a forest of denuded pine-trees.

A machine for raising and lowering masts, with its beams and pulleys, stood at the corner of a quay covered in piles of squared timber, and a little way behind it, I could see the houses of the town painted in various shades, some with green roofs, in a low horizontal line, above which only the domes of the churches accompanied by their small domes protruded. Fortified cities offer the slightest possible presence to the sight, and to naval cannon; the sublimest of that genre would be that which one can scarcely see at all: such will no doubt be achieved.

The customs-men or naval police, set off in oared boats from a building with a Greek pediment, towards our steamer, which had dropped anchor, and was at rest. The scene reminded me of the visits by the sanitary inspectors in harbours of the Levant, where a host of officials more plague-ridden than us, breathing four-thieves vinegar (a blend of vinegar, herbs, spices, and garlic once thought a protection against plague. A French folk tale tells of a group of thieves who employed it to escape the Black Death, in the 17th century), came to examine our papers using long tweezers. Everyone was on deck, and in a boat which appeared to be awaiting, once the formalities were completed, some traveller disembarking for Kronstadt, I saw my first moujik (or ‘muzhik’, a peasant, a dismissive diminutive of ‘mouj’, a man). He was a fellow of twenty-eight or thirty years old, his long hair separated by a middle parting, with a blond beard, curled somewhat, in the manner in which painters paint Jesus Christ; with well-set limbs, he handled his double oar easily. He wore a pink shirt, tight at the belt, whose tails, hanging over his trousers, formed a sort of tunic or rather graceful jacket. The legs of his trousers of blue fabric, ample, and with abundant folds, were tucked in his boots; his headdress consisted of a cap or rather a small flat hat, narrow in the middle, flared above and with a circular rim. This first specimen had already witnessed to the truth of those designs by Adolphe Yvon.

Borne towards us in their boats, the employees of the police and customs, dressed in long overcoats and wearing Russian caps with visors, and for the most part adorned with medals, climbed on deck and fulfilled their office with great politeness. We were asked to descend to the lounge cabin to retrieve our passports which had been deposited in the captain’s hands when we left port. The passengers were English, German, French, Greek, Italian and folk of other nations; to our great surprise, the police superintendent, quite a young man indeed, employed a different language with every interlocutor, responding to the English in English, the Germans in German and so on, without being mistaken as to nationality. Like Cardinal Angelo Mai he seemed to be fluent in every possible idiom.

When my turn came, he returned me my passport, while saying to me, in the purest Parisian accent: ‘You have long been awaited in St. Petersburg.’ In truth, I had taken the path schoolboys take, who spend a morning traversing a road they could tread in an hour. To my passport was attached a trilingual paper indicating the formalities to be completed upon arriving in the City of the Tsars.

The steamboat started up again, and, standing on the bow, I gazed with eager eyes at the extraordinary spectacle that unfolded before me. We had entered the arm of sea into which the Neva flows. The appearance was rather that of a lake than a gulf. As we held to the middle of the channel, the banks on each side were barely discernible. The waters, spreading widely, seemed higher in elevation than the land, which was thin as a brush-stroke in a flat-toned watercolour. The weather was magnificent. A sparkling, though cold, light fell from a clear sky; it was a boreal, azure, polar light so to speak, with nuances of milk, opal, and steel, of which our skies give little idea; a pure, white, sidereal clarity, seemingly not shed by the sun, such as we imagine when in dream we are transported to another planet.

Beneath this milky vault, the immense surface of the gulf was dyed with indescribable colours, into which the ordinary tones of water failed, wholly, to enter. Sometimes the tones were of the pearly whiteness one sees in the valves of certain shells, sometimes they were pearl-greys of incredible subtlety; further away, there were matte shades or the surface was streaked with the blue of Damascene blades, or iridescent with reflections, as in the film which coats molten tin; an area of a polished ice was followed by a wide embossed strip in antique moiré; but all this with a certain lightness, blurred and vague in nature, but limpid and bright, to the point of being unreproducible by the artist’s palette, or the writer’s vocabulary.

The freshest tone of the painter’s brush would have seemed like a muddy stain on this ideal translucency, and the words I employ to describe this marvellous glow seem to me mere inkblots falling from a spitting pen onto the vellum’s surpassingly beautiful azure.

If a boat passed close by with its solid tones, its salmon-coloured masts, and its clearly delineated details, it looked, in the midst of this Elysian blue, like a balloon floating in air; one could not dream of anything more magical than that luminous infinity!

At the end of this tract of water slowly emerging, between the milky water and the pearly sky, surrounded by its crown of crenelated and turreted walls, rose the magnificent silhouette of St. Petersburg whose amethyst tones separated like a line of demarcation those two pale immensities. Gold sparkled from the domes and spires forming its diadem; the richest, the most beautiful the brow of a city has ever borne.

Soon Saint Isaac’s Cathedral displayed, between four pinnacles, its golden dome like a tiara; the Admiralty Building raised its gleaming spire; the Church of the Archangel Michael (in Saint Michael’s Castle, the Mikhailovsky) revealed its bulging Muscovite dome, that of the Horse Guards (the Cathedral of the Annunciation, not extant) showed its sharp pyramidions each surmounted by a cross, and a crowd of more distant bell-towers shimmered with metallic flashes of fire.

Nothing could be more splendid than this city of gold on this silver horizon, where evening owns to the whiteness of dawn.

Chapter 6: St. Petersburgh

The Neva is a beautiful river, about as wide as the Thames at London Bridge; its course is not very long: it flows from Lake Ladoga, close by, and discharges into the Gulf of Finland. A few turns of the wheel brought us alongside a granite quay near which was moored a flotilla of small steamboats, sailing-ships, schooners, and other boats.

On the far side of the river, that is to say on the right, ascending, rose the roofs of huge hangars containing construction docks; on the left, large buildings with palatial facades, which I was told were the Corps of Mines and the Naval Cadet School, revealed their monumental lines.

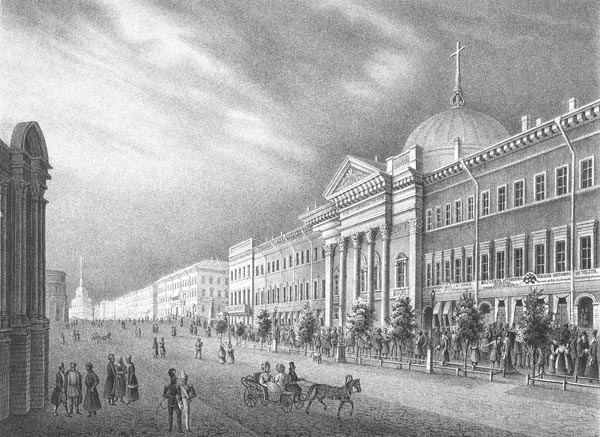

View of the Saint Petersburg Stock Exchange from the Bolshaya Neva

From Voyage pittoresque en Russie by Charles de Saint-Julien, 1853

Internet Archive

It is not an easy task to unship the luggage, trunks, bags, boxes, and parcels of all kinds which clutter the deck of a steamboat when one disembarks, and to recognise one’s own belongings among all the accumulated pile. A swarm of moujiks soon removed the whole, carrying each individual load to the visitors’ office on the quay, followed by its worried owner.

Most of these moujiks wore a pink shirt over their trousers, in lieu of a jacket, wide trousers and mid-length boots; others, although the weather was unusually mild, were already decked out in tulups, long sheepskin coats. The tulup is sewn with the wool inside, and when new, the tanned skin is a fairly pale salmon colour pleasing to the eye; a few stitches do for decoration, and the whole is not lacking in character, while the moujik is as loyal to his tulup as the Arab is to his burnous; once endorsed, he never abandons it: it is his tent and his bed; he wears it night and day, sleeps in it at every corner, on every bench and stove-top. Soon the garment becomes greasy, shiny, and, glazed with frost, takes on those bitumen tones that Spanish artists affect in their picaresque paintings; but, unlike the models who sat for Jusepe de Ribera and Bartolomé Murillo, the moujik is clean under this filthy garb, because he visits the steam-baths once a week. These men, with their long hair and full beards, dressed in animal skins, on a magnificent quay from which you can see, on every side, golden domes and spires, ensure that the foreigner’s imagination is seized by the contrast. However, there is nothing wild or alarming in the sight; these moujiks reveal gentle and intelligent countenances, and their polite manners would put to shame the crudeness of our porters.

The inspection of my luggage took place without further incident than the prompt discovery of Les Parents

Pauvres (‘The Poor Family’), by Balzac, and Les Ailes d’Icare (‘The Wings of Icarus’), by Charles de Bernard, on top of my linen, both of which the officials removed, telling me to ask for them at the Censor’s Office where they would doubtless be returned to me.

The formalities complete, we were free to roam the city. A multitude of droshkys (four-wheeled open carriages) and small carts to transport the luggage were waiting in front of the visitors’ office, careful not to miss the opportunity. I knew the name in French of the street I needed, but it had to be rendered in Russian by the coachman. One of the local domestics, who no longer speak any idiom, and end up composing a kind of Frankish language akin to the jargon used by the stage-Turks in that ceremony in Moliere’s Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, saw my embarrassment, and soon understood that I wanted to go to the Hotel de Russie, run by Monsieur Klée, stacked my packages on a rospousky, climbed up beside me, and we were on our way. The rospousky is a long low cart of the most primitive nature: a pair of rough-hewn logs, set on four small wheels; it is no more complicated than that! When you leave behind the majestic solitude of the sea for the whirlwind of human activity, and tumult of a great capital city, it dazes you somewhat; you pass, as in a dream, amidst unknown objects, wishing to see everything, and thereby seeing nothing; it seems to you that the waves are still rocking you, especially when a vehicle with as little suspension as a rospousky causes you to sway and bump about over uneven paving, and produces the illusion of seasickness, on solid land: but, although harshly treated, I saw all, and my gaze devoured each fresh sight that presented itself.

We soon arrived at a bridge, which we later knew to be the Annunciation Bridge (the Blagoveshchensky Most) or, more commonly, the Nicolas Bridge (the Nikolaevsky); it consists of two swing-sections at the northern end, which are opened for the passage of boats, and then returned to their positions, so that the bridge temporarily appears as a Y with shortened arms above the river; at the junction of these arms stands a small and extremely ornate chapel, of whose mosaics and gilding I could catch no more than a glimpse in passing.

At the end of the bridge, whose piers are made of granite, and arches of iron, the cart made a turn and followed the English quay lined throughout with pedimented and columned palaces, and private mansions no less splendid, painted in cheerful colours, and with canopied balconies extending over the pavement. Most houses in St. Petersburg, like those of London and Berlin, are in brick coated with plaster in various hues, in such a way as to highlight the architectural lines and produce a fine decorative effect. In passing them, I admired, behind the lower windows, banana trees, and tropical plants blooming in those warm apartments as in a greenhouse.

The English quay opens onto the corner of a large square where Étienne Falconet’s statue of Peter the Great on his rearing steed extends its arm towards the Neva, from the top of the rock which serves as its base. I recognised it instantly, agreeing as it did with Diderot’s description, and drawings I had seen. At the bottom of the square stood the gigantic silhouette of Saint Isaac’ Cathedral with its golden dome, columnar tiara, four pinnacles and octostyle (eight-pillared) pediment. At the entrance to a street behind the English quay, winged Victories in bronze, on porphyry columns, held palm fronds. All this, glimpsed confusedly, due to the speed of the vehicle, and the astonishment caused by novel sights, formed a magnificent and Babylonian ensemble.

The Bronze Horseman (Peter the Great) Senate Square, Saint Petersburg

From Voyage pittoresque en Russie by Charles de Saint-Julien, 1853

Internet Archive

Continuing in the same direction, the immense Admiralty Palace soon became visible! A square tower in the shape of a temple, decorated with columns set on its roof, raised its thin gold spire with a ship atop for a weather-vane, which can be seen from afar and which had drawn my gaze in the Gulf of Finland; the avenues of trees that extend around the building had not yet lost their foliage, though the autumn was already advanced (it was the tenth of October).

Further on, in the midst of a final square, the Alexandrine Column soared from its bronze base, a prodigious monolith of pink granite surmounted by an angel carrying a cross. I only caught a glimpse of it, since the cart turned and entered Nevsky Prospekt, which is to St. Petersburg what the Rue de Rivoli is to Paris, Regent’s Street to London, the Calle d’Alcalá to Madrid, and the Via Toledo to Naples, the main artery of the city, that is, the busiest place and the one which is most alive.

What struck me especially was the immense amount of traffic – for a Parisian is seldom surprised in this manner – the throng of carriages filling the wide street, and especially the extreme liveliness of the horses. Droshkys are, as we know, a species of small, low, very light phaetons, which only contain two people at most; they go like the wind, driven by coachmen as bold as they are skilful. They overtook our rospousky with the speed of swallows, crossed and interwove, passing from wood-block paving to granite without ever touching one another; seemingly inextricable embarrassments were resolved as if by magic, and everyone, after flying by, sped off on their own, finding space for the wheels where a wheelbarrow could not pass.

Nevsky Prospekt is both the mercantile street and the finest street in St. Petersburg; the shop-rents there are as high as on the Boulevard des Italiens, in Paris: there is a mix of stores, palaces, and wholly original churches; on the signs in lines of gold shine the beautiful characters of the Russian alphabet, which retains a few Greek letters, whose lapidary forms lend themselves to inscriptions.

All this passed before my eyes like a dream, because the rospousky was travelling so quickly and, before I realised it, we were in front of the steps of the Hôtel de Russie, whose owner scolded, most harshly, the servant who had installed his lordship in such a wretched vehicle. The Hôtel de Russie, located on the corner of Michael Square, near Nevsky Prospekt, is scarcely less grand than the Hôtel du Louvre in Paris; its corridors are longer than many streets, and weary one. The lower floor is occupied by vast lounges where you dine and which are adorned with hothouse plants. In the main salon, on a kind of bar, caviar, herrings, sandwiches made with white and brown bread, cheese of several kinds, bottles of beer, kummel, and brandy, serve, in the Russian manner, to whet the appetite of their consumers.

Appetizers here are eaten before the meal, and I travelled far before encountering this strange custom. Each country has its habits: in Sweden do they not serve soup for dessert? At the entrance to this salon, there was a coat-rack surrounded by a partition, where everyone hung their overcoat, muffler, and plaid, and stood their galoshes. However, it was not at all cold, and the thermometer in the open air, showed seven or eight degrees Centigrade. These careful precautions, given so mild a temperature, surprised me, and I looked outside to see if snow was not already whitening the roofs, but only the faint pink glow of evening coloured them.

However, double windows were already installed everywhere; enormous piles of logs cluttered the streets, and all were preparing to welcome winter in style — my room also owned to that hermetic seal; between one frame and the other sand was spread in which small cones filled with salt were planted, designed to absorb moisture and prevent warping due to the silvery patterns of frost, which, without this precaution, coat the windows; copper heating-vents, similar to the mouths of letter-boxes, stood ready to blow their gusts of warm air, but winter was late to arrive; and the double windows served to keep the apartment pleasantly warm. The furnishings owned to no particular local character, other than one of those immense sofas covered in padded leather that one encounters everywhere in Russia, and which, with their numerous cushions, are more comfortable than the beds, which are wretched, indeed, for the most part.

After dinner I sallied forth without a guide, according to my usual habit, and trusted to my instinctive sense of direction to find my lodgings again. A watchmaker’s dial over one corner, a watchtower at another, served as points of reference. This first outing, taken at random, through an unknown and long dreamed-of city is one of the most vivid delights of the traveller and repays one for the wear and tear, and the fatigue, of the journey — is it mere embellishment to say that night, with its mingling of light and shadow, its mystery and fanciful magnifications, adds a great deal to this pleasure? The eye glimpses, the imagination refines. Reality does not present itself with too harsh a line, and its various aspects emerge in solid masses, as in a painting that the artist intends to complete later.

So, there I was, treading the pavement with slow steps, following the Prospekt in the direction of the Admiralty. Now I looked at the passers-by, now at the brightly lit shops, into whose basements, which reminded me of the ‘caves’ of Berlin and the ‘tunnels’ of Hamburg, I plunged my eyes. At every step, I encountered artistically grouped displays of fruit behind elegant windows: pineapples, grapes from Portugal, lemons, pomegranates, pears, apples, plums, watermelons — the taste for fruit is as widespread in Russia as the taste for sweets in Germany; it costs a lot, which makes it even more desirable. On the pavements, moujiks offered passers-by apples, acid-green to the eye, which nevertheless found buyers. They were stationed at every corner.

A first reconnaissance completed, I returned to the hotel. If children need to be lulled to sleep, adults prefer motionless slumber; and for three nights the waves had tossed me about sufficiently in the steam-boat to make me desire a more stable bed; though amidst my dreams the ripple of the waves could still be felt. I experienced this weird effect several times —the sacrosanct solid-ground, so appreciated by Panurge (see ‘Gargantua and Pantagruel’, Book IV), is not as swift a remedy as one might think for the anxieties caused by the shifting surface of the liquid plain.

Next day, I issued forth early, to revisit the sights divined the previous evening in the vague twilight and the descending night. As Nevsky Prospekt somehow sums up all St. Petersburg, allow me to give a somewhat long and detailed description which will grant you an immediate intimacy with the city. Forgive me in advance for a few puerile and seemingly trivial remarks. It is those little things which are neglected as far too humble and easily observed that constitute the difference between one place and another, and warn you that you are not in the Rue Vivienne or Piccadilly.

It is from Admiralty Square that Nevsky Prospekt extends, for an immense distance, to the monastery of Saint Alexander Nevsky, where it terminates after a slight bend. The street is wide like all those in St. Petersburg, the middle of the road is surfaced with fairly rough stone chippings whose two slopes when meeting form the bed of the roadway. On either side, a wooden border edges the band of small granite fragments; large slabs cover the pavements.

Admiralty Square, St Petersburg - Louis-Julien Jacottet, 1840 - 1865

Rijksmuseum

The Admiralty spire, which resembles the golden mast of a vessel planted on the roof of a Greek temple, at the end of the Prospekt, represents a landmark happily achieved. With the slightest ray of sunlight, it gleams, and entertains the eye however far away one might be. Two other neighbouring streets also enjoy this advantage and due to their adroitly arranged layout, allow one to catch sight of that same golden needle; but for the moment let us turn our backs on the Admiralty, and walk up Nevsky Prospekt to the Anichkov Bridge (over the Fontanka), that is to say along the liveliest and most frequented stretch. The houses that line it are tall and vast, with the appearance of palaces or hotels. Some, the oldest, recall the old French style, a little Italianised, and present a majestic mix of the architectural styles of François Mansart, and Gian Lorenzo Bernini; Corinthian pilasters, cornices, windows with pediments, consoles, bull’s-eyes with scrolls, doorways with grotesque carvings, ground floors with simulated joints and rustic quoins usually raised on a pink plaster background. Others offer fantasies of ornamentation in the Louis XV style, rocaille, chicory-leaves, napkins, vases of flame, while the Greek taste of the Empire further displays itself in columns and triangular pediments highlighted with white on a yellow background. The wholly modern houses are of an Anglo-German genre, and seem to have taken as models those magnificent hotels in seaside towns, lithographs of which seduce the traveller. This collection, whose details cannot be too closely studied, since the use of stone alone gives value to the execution of the ornamentation while retaining the direct imprint of the artist; this whole, I say, forms an admirable and eye-catching view for which the name Prospekt, that the street bears, like many another thoroughfare in St. Petersburg seems to me wondrously just and meaningful. Everything is laid out for the eye, and the city, created in one fell swoop by an act of will which brooked no obstacle, emerges complete from the swamp it superseded, like a theatre-set at the sound of the stage manager’s whistle.

If Nevsky Prospekt is beautiful, let me hasten to say that it profits from its beauty. Fashionable and mercantile, its palaces and stores alternate; nowhere, except in Berne, do the signs imply a like luxury. Here one almost has to concede that a modern architectural order has been added to Giacomo da Vignola’s five (see his ‘Regola delli Cinque Ordini d’Architettura; Canon of the five orders of architecture’, 1562). Golden lettering traces its curves and strokes across azure fields and red or black panels, is stamped in ironwork, applied to storefront windows, repeated at every door, profits from street-corners, surrounds arches, extends along cornices, takes advantage of the protrusion of the padiezdas (awnings), descends basement steps, and seeks every means of attracting the eye of the passer-by. But perchance you know no Russian, and the shape of these characters means nothing more to you than a decorative design or a pattern of embroidery? Next to it is a translation in French or German. You still don’t understand? The indulgent sign forgives you for knowing none of the three languages, it even assumes that you may be completely illiterate, and therefore presents the actual items sold in the store it advertises. Golden grapes, sculpted or painted. indicate a wine merchant; further on there are glazed hams, sausages, tongues of beef, cans of caviar designating a food-store; boots, ankle-boots, and naively-carved clogs address feet unable to read: ‘Enter, and you will be shod’; a necklace of gloves speaks an idiom intelligible to all. There are also mantles and women’s dresses topped with a hat or a cap, to which the artist has not judged it necessary to add the human form; pianos invite you to try their painted keyboards. All this entertains the stroller and has a character of its own.

The first thing that attracts the attention of the Parisian strolling along Nevsky Prospect is the name of the print-dealer Giuseppe Daziaro (known in Russia as Iosif Datsiaro, his store was at No.1) whose sign, in Russian, he has undoubtedly noticed on the Boulevard des Italiens; continuing on the right he will stop at the gallery, owned by Beggrov (the painter Karl Beggrov, or one of his family, at No.4), the Deforge (Armand-Auguste Deforge the prominent art-dealer) of St. Petersburg, which sells artists’ pigments and always displays some watercolor or painting in its window.

Numerous canals crisscross the city, which is built on twelve islets like a northern Venice. Three of these canals cross transversely beneath Nevsky Prospekt, that of the Moyka, the Catherine Canal (the Griboyedov), and further on that of the Liga and Fontanka. The Moyka is crossed by the Police Bridge (also known as the Green Bridge) whose salient curvature forms a sloping arc, and slows for a moment the rapid pace of the droshkys. The Kazan and Anichkov bridges span the other two channels. When one crosses these bridges before the winter season, one’s gaze is pleasurably drawn to the gaps opened amidst the houses by these constricted waters, bordered by granite quays, and crisscrossed with boats.

Gotthold Lessing, the author of Nathan the Wise, would have liked the Nevsky Prospect, since his ideas regarding religious tolerance are put into practice there in the most liberal fashion; there is scarcely any communion that lacks its church or temple on this wide street, exercising its worship there in complete freedom.

Here, on the left, in the direction I am walking, is the Dutch church, the Lutheran Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, the Catholic church of Saint Catherine, an Armenian church, not to mention, in the adjacent streets, the Finnish chapel and temples of other reformed sects; on the right, the Russian Cathedral of Our Lady of Kazan, another Greek church, and a chapel for dissenters, adherents of the old rite, who are known as Starovertzi or Raskolniki. All these houses of God, except Our Lady of Kazan whose elegant semicircular portico, interrupting the architectural lines, and facing a vast square, is imitated from the colonnade of Saint Peter’s in Rome, mix familiarly with the houses of mankind; their facades are only isolated by being slightly set back; they offer themselves without mystery to the piety of the passer-by, recognisable by their particular style of architecture. Each church is surrounded by vast grounds granted by the Tsars, lands covered with substantial buildings rented out as manufactories.

The Dutch church, in St Petersburg - Charles Schütz, 1820 - 1899

Rijksmuseum

Continuing on our way, we arrive at the tower of the City Duma, a sort of lookout-station for the fire service, like the Seraskier Tower (Beyazit Tower) in Constantinople; on its attic storey a signal apparatus is placed, whose red or black globes indicate the street where a fire is raging. Nearby, on the same side, rises the Gostiny Dvor, a large trapezoid-shaped building, with galleries on two floors, which reminds me a little of our Palais-Royal, and contains shops of all kinds, with luxurious displays. Next comes the Imperial Library, with its rounded corner facade, and Ionian columns, then the Anichkov Palace, which gave its name to the neighbouring bridge decorated with four bronze horses, rearing from granite pedestals and restrained by squires.

Such is the Nevsky Prospect, roughly sketched; but you will say: there are no human beings in your picture; no more than in those the Turkish daubers paint. Wait a moment, since I am about to animate the scene and populate it with figures. The writer, less fortunate than the painter, can only present objects in succession.

I have promised to add characters to my Nevsky Prospekt. Let me attempt to sketch them myself, not having, as the draughtsmen do, the resources to employ a pencil more skilled than mine, and write at the foot of the result: ‘Figures by Duruy or Bayot (Antoine Duruy, Adolphe Bayot).

From one o’clock to three is when the crowd is largest; besides the passers-by who go about their business and walk quickly, there are strollers whose only goal is to see, to be seen, and to take their exercise; their coupés or their droshkys await them at some place agreed, or even parallel their steps, on the road, in case the fancy takes them to remount their carriage.

Firstly, one may distinguish the officers of the guard, in grey greatcoats, with a tab on the shoulder marking their rank; they almost always push out their chests decorated with stars, and are adorned with a helmet or cap; then come the chinovniks (officials), in long frock-coats pleated, and gathered by a belt, at the back; they wear, instead of a hat, a cap dark in colour, with a cockade; youths who are neither military nor employed, display overcoats trimmed with fur of a value to astonish foreigners and from which our dandies would recoil. These fine cloth overcoats are lined with marten’s or musk-ox fur and have beaver collars costing from one to three hundred rubles, depending on the extent to which the hair is fuller, softer and darker in colour, and whether the white hairs extending beyond the surface of the fur have been retained — the price of a thousand-rubles for an overcoat is not seen as exorbitant, there are some that are worth more; they represent a Russian luxury unknown to us: in St. Petersburg the proverb: ‘Tell me who you’re seen with, and I’ll tell you who you are,’ might be altered to a northern variant: : ‘Tell me what furs you wear, and I’ll tell you what you’re worth.’ One is judged according to one’s coat.

What! Are you thinking, given this description, of furs already! At the start of October, in a period of exceptionally mild weather, that to a northerner is as warm as Spring! Why, yes, — the Russians are not as foolish as people seem to think — we all imagine that, seasoned by their climate, they rejoice like polar bears at snow and ice; nothing is falser; on the contrary, they are very cautious, and so as to protect themselves from the slightest bad weather take precautions that foreigners, on a first visit, neglect, even if they adopt them later.... after they have fallen ill. If you see a man passing by, lightly dressed, with an olive complexion, and a prolixity of beard, and with dark sideburns, you will recognise him as an Italian, a southerner, whose blood has not yet cooled — don your wadded overcoat, put on your galoshes, tie a muffler round your collar, I tell you — yet the thermometer reads five or six degrees above zero — no matter, there is here, as in Madrid, a little wind which would not extinguish a candle yet bothers a man. Having donned an overcoat in Madrid at eight degrees Centigrade, there was no reason to neglect a winter coat in autumn, in St. Petersburg — one should always attend to national wisdom — a coat lined with light fur is worn mid-season; at the first snowfall, one adopts a long fur overcoat (pelisse), and retains it till the month of May.

If Venetian women only go around by gondola, women from St. Petersburg only do so by carriage; and rarely descend except to take a few paces on Nevsky Prospekt. They adhere to Parisian hats and fashions. Blue seems to be their favourite colour; it suits their pale complexions and blonde hair. Of their elegance and height, one cannot judge, in the street at least, since ample pelisses of black satin, or sometimes of Scottish tartan in broad check envelop them from neck to heel. Coquetry gives way here to considerations of climate, and the prettiest feet plunge without regret into large shoes: Andalusians would prefer to die; but, in St. Petersburg, the phrase ‘to avoid a cold’ answers all. These pelisses are of sable, Siberian blue fox, or other furs, the extravagant prices of which the rest of us westerners, would hardly surmise; unheard-of luxury obtains in this regard; and if the rigour of the climate only allows women the one shapeless sack, rest assured, that sack will cost as much as the most splendid of gowns.

After about fifty paces, these indolent beauties regain their coupé or carriage, and go on visits, or return home.

What I am describing here relates to society women, that is to say the nobility; the others, even if they are as rich, adopt a humbler appearance, but of equal beauty: quality above all. Here are German women, merchants’ wives, recognisable by their Germanic type, their sweet and dreamy air, and their neat clothes, though clad in simpler fabrics; they wear talmas (short cloaks), basquines, or coats of cloth with a thick pile. Here are French women in bright garb, velvet overcoats, hats covering the entire top of the head, which makes one think of the Jardin Mabille and the Folies-Nouvelles in Paris, on the pavements of the Nevsky Prospekt.

Strictly speaking, until now you might believe yourself on the Rue Vivienne or any boulevard; a little patience, and you will observe the Russian type. Regard this man, in a blue kaftan buttoned at the corner of his chest like a Chinese robe, which is gathered at the hips in symmetrical pleats and of exquisite propriety, he is an artelshchik or merchant’s servant; a flat disc-shaped hat with a visor, set on the forehead, completes his garb; his hair and beard are parted as in depictions of Christ; his physiognomy is honest and intelligent. He is tasked with errands, requests, and commissions that require probity.

The moment you lament the absence of the picturesque, a nursemaid in traditional, national dress passes by; her headdress is a povoïnik, a kind of hat shaped like a tiara, in red or blue velvet, decorated with gold embroidery. The povoïnik is hollow or closed on top; open, it designates a young girl; closed, a woman; that of the nursemaid has a lower fringe, and the hair falls from under this hat in two braids which hang down the back. Virgins, gather their hair in a single braid. The padded damask dress, its waist gathered under the arms and with a very short skirt, looks like a tunic, and reveals a second skirt of a less rich fabric. The tunic is red or blue like the povoïnik and is edged with gold braid. This fundamentally Russian costume, worn by a beautiful woman, possesses style and nobility. The grand gala dress at court festivities is tailored to this pattern, and streaming with gold, studded with diamonds, it contributes no little to a woman’s splendour.

In Spain, it is regarded as elegant for nursemaids to wear the pasiega costume in public; and I admired the lovely countrywomen on the Prado and the Calle d’Alcala, with their black velvet jackets and scarlet skirts with gold bands. It seems that civilisation, sensing that the national character is fading everywhere, seeks to imprint the memory of it on its children, by bringing from the depths of the countryside a woman in traditional costume, who provides an image of the motherland.

Speaking of nursemaids, allows me to mention the children; the transition is wholly natural. Russian babies are very neat in their little blue kaftans, hair flattened beneath a hat akin to a sombrero calañés (the Andalusian hat from Calañas in Huelva province) with the decorative knob on its top adorned with a peacock feather.

There are always a few dvorniks or doormen on the pavement, busily sweeping it in summer, or clearing the ice in winter. They rarely remain in their lodges, if lodge they have, in the sense in which we use the word, rather keeping watch all night, not moving from their place, and hastening to open in person at the first summons, since it is asserted, and strange it is, that a doorman is there to open the door at three in the morning, as much as at three in the afternoon. They sleep here and there, and never undress. They wear a blue shirt hanging over their trousers, moderately broad trousers, and high boots, a costume that they exchange at the first sign of cold for a double- sheepskin.

From time to time a lad, draped in an apron akin to a loincloth tied at the waist by a string, leaves some craftsman’s workshop and crosses the street quickly to enter a house or shop a little further away, he is a malchik or apprentice (strictly, ‘a youngster’) whom his master sends on an errand.

The picture would be incomplete if we failed to add a few dozen moujiks in tulups, shiny with dirt and grease, selling apples or cakes, carrying provisions in korzinas (baskets woven of strips of fir-wood), mending and trimming the wooden paving-blocks with axes, or, in groups of four or six, bearing with measured tread, a piano, a table, or a sofa on their shoulders.

One scarcely sees female moujiks, they either remain in the countryside on their master’s estate, or they occupy themselves at home in domestic work. Those that one encounters, here and there, have no particular characteristics dress-wise. A kerchief tied beneath the chin covers and frames the head; a padded overcoat in plain fabric, neutral in colour and of questionable cleanliness, descends to mid-leg, and reveals a skirt of Indian cotton with thick felt stockings and wooden clogs. They are not very pretty, and have a sad and gentle air about them; not a flicker of envy lights their pale eyes at the sight of a well-dressed and beautiful lady, and coquetry seems to be unknown to them. They accept their inferiority, which no woman among us does, however lowly placed she may be.

Overall, I was struck by the proportionately small number of women in the streets of St. Petersburg. As in the Orient, men alone seem to have the privilege of travelling about, there. It is the opposite in Germany, where the female population are always outside the home.

I have only populated the pavement with figures so far; the roadway itself presents no less animated and lively a spectacle. There a perpetual torrent of carriages flows by, and crossing the Nevsky Prospekt is an operation no less dangerous than crossing the boulevard between the Rue Drouot and the Rue Richelieu. One seldom walks in Saint Petersburg; one takes a droshky for a journey of only a few paces. A carriage is considered here not as an object of luxury, but one of prime necessity. Small merchants and poorly paid employees deprive themselves of many things, and almost embarrass themselves, in order to own a kareta (carriage), droshky, or sled. Going about on foot is seen as a mark of dishonour. A Russian without a carriage is akin to an Arab without a horse. His nobility might be doubted; he might be taken for a mekanin (workman), or a serf.

The drosky is the national carriage par excellence, it has no analogue in any other country and deserves specific description. Here is an example, waiting, lined up alongside the pavement, its master visiting some house nearby, which seems posed expressly for our purpose. It is a fashionable droshky, belonging to a young gentleman careful as to appearances. The droshky is a small open carriage, low slung, and with four wheels; the ones behind are no bigger than the front wheels of our American carriages, or victorias; those in front than that of a wheelbarrow. Four curved springs support the box which supports two seats, one for the coachman, the other for the master. The latter seat is rounded, and, in the elegant droshkys called egotistics, only holds one person; in the others there are two places, but so narrow that one is obliged to pass one’s arm around one’s neighbour.

On each side, two patent leather mudguards arc above the wheels and, joining at the sides of the carriage, which has no doors, form a descending step a few inches from the ground. Beneath the coachman’s feet is the swan’s-neck (attaching the carriage body to the front wheels by means of curved suspension pieces); there are no patented hoods to the wheels, for a reason I shall explain when describing the method of harnessing.