Théophile Gautier

Travels in Russia (Voyage en Russie, 1858-59, 1861)

Part I: Berlin, Hamburg, Schleswig

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction.

- Travels in Russia.

- Chapter 1: Berlin.

- Chapter 2: Hamburg.

- Chapter 3: Schleswig.

Translator’s Introduction

Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) was born in Tarbes, in the Hautes-Pyrénées region of south-west France, his family moving to Paris in 1814. He was a friend, at school, of the poet Gérard de Nerval, who introduced him to Victor Hugo. Gautier contributed to various journals, including La Presse, throughout his life, which offered opportunities for travel in Spain, Algeria, Italy, Russia, and Egypt. He was a devotee of the ballet, writing a number of scenarios including that of Giselle. At the time of the 1848 Revolution, he expressed strong support for the ideals of the second Republic, a support which he maintained for the rest of his life.

A successor to the first wave of Romantic writers, including Chateaubriand and Lamartine, he directed the Revue de Paris from 1851 to 1856, worked as a journalist for La Presse and Le Moniteur universel, and in 1856 became editor of L’Artiste, in which he published numerous editorials asserting his doctrine of ‘Art for art’s sake’. Saint-Beuve secured him critical acclaim; he became chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1862, and in 1868 was granted the sinecure of librarian to Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, a cousin of Napoleon III, having been introduced to her salon.

Gautier remained in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and the aftermath of the 1871 Commune, dying of heart disease at the age of sixty-one in 1872.

Though ostensibly a Romantic poet, Gautier may be seen as a forerunner to, or point of reference for, a number of divergent poetic movements including Symbolism and Modernism.

His travels in Russia, in 1858-59, including visits to Saint Petersburgh and Moscow, reveal further aspects of the wide influence achieved by French culture evidenced in all Gautier’s travel writing, and confirm, once more, his passionate interest in all things artistic. He left for Russia in September 1858, and was there until March 1859, the aim being to publish a work on the Art Treasures of Ancient and Modern Russia, illustrated with two hundred heliogravure plates taken from photographs; his companion, the photographer Pierre-Ambroise Richebourg, was to be responsible for these, as instructed by Gautier, who would write the accompanying text. Tsar Alexander II was the patron, and the trip was fully funded by a businessman, Carolus van Raay. Gautier was in St, Petersburg by mid-October 1858, and visited Moscow briefly in early February 1859 before returning to St, Petersburg, and then Paris in late March. Gautier had also agreed, in exchange for six months’ leave, to provide the Moniteur Universel with a series of articles giving his travel impressions, which provided the basis for Voyage en Russie.

He was in Russia again in August and September 1861, with his eldest son Charles-Marie Théophile, known as Toto, and a family friend Olivier Gourjault, a trip which included further visits to St. Petersburg and Moscow, and his visit to Nizhny Novgorod via Tver and the River Volga.

This enhanced translation has been designed to offer maximum compatibility with current search engines. Among other modifications, the proper names of people and places, and the titles given to works of art, have been fully researched, modernised, and expanded; comments in parentheses have been added here and there to provide a reference, or clarify meaning; and minor typographic or factual errors, for example incorrect attributions and dates, in the original text, have been eliminated from this new translation.

Travels in Russia

Chapter 1: Berlin

We have barely left, yet here we are, far from France. I shall say naught of the intermediate space traversed by the nocturnal flight of our Hippogriff. Accept that we are in Deutz on the far side of the Rhine, at the end of the boat- bridge, gazing at the silhouette of Cologne, which the bottles of fragrance (Eau de Cologne) produced by Johan-Maria Farina have made familiar to all the world, outlined against the evening splendour. The bell of the Rhine railway sounds, we enter the carriage, and the train slides away, in a cloud of steam.

Tomorrow, at six, I will be in Berlin; yesterday I was still in Paris, at the moment when the street-lights were illuminated. This surprises no one, in this marvellous nineteenth-century of ours, except myself.

The convoy speeds across a vast cultivated plain which the setting sun gilds; soon night comes, and with it sleep. At the widely-separated halts, German voices shout German names that the accent disguises, and prevents me from finding in the guide-book; magnificent stations, monumental buildings, take shape in the shadows, the gaslight glows and disappears.

We have passed Hanover, and Minden; the train rolls on and dawn is breaking.

To the right and left stretch peat-lands, amidst which the morning mists produce most singular mirage-like effects. It seems to us as if the railway-tracks are crossing an immense lake whose waves die, in transparent ripples, at the edge of the embankment. Here and there a few clumps of trees, or a cottage, emerge like islands, and complete the illusion, which it is; a cloud of bluish fog, floating some few feet above the ground and ruffled by the first rays of the sun, produces this aquatic phantasmagoria similar to the Fata Morgana of Sicily (as seen in the Strait of Messina).

Our disorientated sense of geography protests in vain against this inland sea which no map of Prussia indicates. Our eyes refuse to admit they were in error, and later, as the sun, mounting higher, dries up the imaginary waters, the presence of a boat is needed to make them admit the reality of a watercourse.

Suddenly, on the left of the road, the trees of a large park gather; Tritons and Nereids appear, wading through a pond; a dome set on a circle of columns arches over vast buildings: it is Potsdam.

Despite the speed of the train, we are allowed to glimpse a sentimental couple, who tread, this morning, a deserted path through the gardens. The lover has here the opportunity to compare his mistress to the dawn, and no doubt he recites to her some sonnet, written on the theme of ‘the fair Aurora’.

Not long after we are in Berlin, and a local cab has carried us to the Hôtel de Russie.

One of the traveller’s greatest pleasures is the first brief journey through an unknown city, which destroys, or realises, the picture of it one has formed in one’s mind. Differences in shape, characteristic features, and vagaries of architecture, one’s perception of which is never sharper, catch one’s eye still innocent of acquired habit.

My idea of Berlin was largely drawn from Ernst Hoffmann’s fantastic tales. I had constructed, despite myself, deep in my brain, amidst a cloud of tobacco, a strange and bizarre Berlin, populated by Court Councillors, the Sand Man, the composer Kreisler (Hoffman’s alter ego), the archivist Lindhurst, and the student Anselme; yet I had before me a city regular in form, grandiose in appearance, with wide streets, vast walks, pompous buildings, half-English half-German in style, marked by the stamp of utmost modernity.

As I passed, I glimpsed the depths of cellars with steps so polished, so slippery, so well-scoured, that the gaze slid into them as it might into an antlion’s nest, expecting to discover Hoffmann himself there, with a barrel for a seat, feet crossed on the bowl of his gigantic pipe, in the middle of a chimerical scribble, as depicted in the vignette in the edition of his Tales translated by Francois Adolphe Loève-Veimars; but, in truth, those underground shops which the owners were starting to throw open, bore no similarity to those of my imagination.

The local cats, of benign appearance, failed to roll phosphoric eyes like the tomcat Murr, and seemed incapable of writing their memoirs, or deciphering a score by Richard Wagner, with their claws.

Nothing is less fantastic than Berlin, and it took all the delirious poetic fancy of the storyteller to house ghosts in a city so defined, so upright, so correct, where the bats of one’s hallucinations would find not a single dark corner in which to cling by their claws.

The beautiful monumental houses, which one might readily take for palaces on viewing their columns, pediments, and architraves, are built of brick for the most part, since stone seems rare in Berlin; but brick coated with cement or whitewashed plaster, so as to simulate cut stone; misleading joint-lines indicate fictitious foundations, and the illusion would be complete if, in places, the winter frosts, which have detached the plaster, have not added a reddish tone which makes it appear like baked clay. The need to paint the facades all over, so as to hide the nature of the underlying material, gives them the appearance of large stage-sets depicting architecture, but seen in broad daylight. The protruding parts, the mouldings, cornices, entablatures, and consoles, are of wood, cast-iron or sheet-metal, to which the appropriate form has been given; if one does not look too closely, the effect is satisfactory. All that this splendour lacks, is authenticity.

The palaces that line Regent’s Park in London also offer these porticos and columns, these brick cores overlaid with plaster, and a single layer of paint attempting to imitate stone or marble. Why not build openly in brick, whose warm tones, and ingeniously-contrasted patterns, provide so varied a resource? I have seen, even in Berlin itself, charming houses in this style, possessing the advantage, where the eye is concerned, of being genuine. Feigned material always inspires a degree of concern.

The Hôtel de Russie is very well-located, and I shall describe the view revealed from its entrance, which will give a fairly good idea of the general character of Berlin.

In the foreground is a quay bordering the River Spree — a few boats with slender masts are slumbering on its dark water — boats on a canal or a river, within the confines of a city, always produce a charming effect.

On the opposite quay, a line of houses extends, some of which have retained the stamp of time; the king’s palace occupies the corner. A dome capping an octagonal tower shows, above the roofs its monumental outline, the curved sides granting grace to the rounded cap.

A bridge spans the river, which, due to the sets of white marble statues that adorn it, recalls the Ponte Sant’Angelo in Rome. These groupings, eight in number, if my memory does not deceive me, each consist of two figures, one allegorical and winged representing the homeland or glory, the other realistic and representing a young man guided through several trials to triumph or immortality. These pairings, of a taste entirely classic, in the style of Charles-Antoine Bridan or Pierre Cartellier, do not lack merit, and present excellent nude studies; their bases are decorated with medallions on which the Prussian eagle is happily displayed, half-realistically, half-heraldically; these medallions are a little too rich in decoration, in my opinion, given the simplicity of the bridge, whose central section opens to grant the boats passage.

Further away, through the trees of a promenade or a public garden, the old museum appears, a large building in the Greek style with Doric order columns, highlighted against a painted background. At its corners, horses of bronze held by squires, are silhouetted, on high, against the sky.

Behind, taking a sidelong view, one can see the triangular pediment of the new museum.

A church modelled on Agrippa’s Pantheon fills the space to the right; all this offers a somewhat grandiose prospect worthy of a capital city.

On crossing the bridge, one encounters the blackened façade of the castle, fronted by a terrace with balustrades; the sculptures over the main doorway are done in the old, exaggerated German rococo taste, with flowery, luxuriant, and bizarre ornamentation surrounding them, like valances round a coat of arms, which I have previously admired when viewing the palace at Dresden; this kind of wildness of manner has its charms, and entertains eyes like mine satiated with masterpieces. There is invention here, caprice, originality, and though I may pass for a man with questionable taste, I prefer such exuberance to the coldness of Greek pastiche which offers more erudition than pleasure where modern buildings are concerned.

On each side of the door, large bronze horses, in the style of those of the Fountain of Monte Cavallo in Rome, their bridles gripped by naked squires, are pawing the ground.

I visited the castle apartments, which are beautiful and rich, but offer little of artistic interest except their old ceilings, carved, over-decorated, covered with cherubs, chicory-flowers, and rocailles, in the most curious style. In the concert chamber there is a musicians’ platform, wildly sculptured, all silvered to charming effect. No lack of wealth was employed in its decorations, relying on classic gold lending itself to other colour combinations. The chapel, whose dome projects above the palace roofs, would please a Protestant. It is bright, well-organised, comfortable, and rationally decorated; but on one who has visited the Catholic churches of Spain, Italy, France and Belgium, it failed to produce much of an impression: one thing surprised me, which was seeing portraits of Philip Melanchthon and Théodore de Bèze, painted on a gold background; nothing is more natural, however.

Let us cross the square and view the museum. Let us admire, in passing, an immense basin of porphyry set on cubic blocks of the same material, in front of the staircase which leads to the portico, painted by various hands, under the direction of the famous Peter von Cornelius.

The paintings form a wide frieze, each of the ends of which extends round a side wall of the portico, and which is interrupted in the centre to grant access to the museum.

The left-hand section displays a whole epic poem of mythological cosmogony, treated with the philosophy and science that the Germans bring to these kinds of composition. The right part, purely anthropological, represents the birth, development, and further evolution of humanity.

If I were to describe in detail these two immense frescoes, you would certainly be charmed by the ingenious invention, profound knowledge, and critical sagacity shown by the artists involved; such a work might be worthy of the symbolism of the scholar Georg Friedrich Creuzer. The mysteries of our ancient origins are penetrated there and science proclaims its latest word. If again I showed them to you in one of those beautiful German engravings, the main features highlighted with delicate shadows, with a clean and precise line like that of Albrecht Durer, and with a pale harmony pleasing to the eye, you would admire the order of a composition so artfully balanced, its groupings happily linked to one another, the ingenious episodes, the reasoned choice of attributes, the significance of all; you might even find a certain grandeur of style, masterful poses, beautiful folds of drapery, proud attitudes, characteristic types, daring Michelangelo-style musculature, and a certain noble Germanic wildness well-worth savouring. You would be struck by the penchant for grandeur, the broad concepts, the development of ideas which our French painters generally lack, and might almost, as regards Cornelius, share the German opinion of his status; yet in front of the work itself one’s impression is completely different.

We know that the art of fresco, even when practised by the Italian masters, so skilful in their technique, lacks the seduction of oil-painting. One’s eyes need to grow accustomed to the abrupt, matte tones, so as to untangle the beauties of fresco-work. Many people, who fail to articulate this, since nothing is rarer these days than having the courage of one’s feelings or opinions, find the frescoes of the Vatican and the Sistine unappealing; the mighty names of Michelangelo and Raphael impose on them only silence, and they murmur a few vague expressions of enthusiasm, while they are in genuine ecstasy, at another time, in front of a Madeleine by Guido Reni, or a Virgin by Carlo Dolci. We must therefore make large allowances for the unsatisfying appearance of fresco-work in what I describe, but here the execution is really too repellent: if the mind is satisfied by it, the eye suffers. Painting, all the plastic arts, can only achieve their aim through shape and colour. It is not enough to think, one has to execute. The most beautiful intent needs to be translated by a skilful brush, and if, in large undertakings of this kind, we may readily admit the simplification of detail; the absence of trompe-l’oeil; neutral, abstract and, so to speak, historic colouring; we would still wish to be spared harsh, sour tones, screamingly loud and painful discordances, clumsiness, gracelessness, and a heaviness of touch. Whatever respect we owe to the idea, the primary attribute of a painting is to be painterly, while so mundane an execution as this, is truly a veil between the artist’s concept and the viewer.

The only representative in France of this philosophical art, is Paul Chenavard, the creator of the cartoons intended for the decoration of the Pantheon; a gigantic labour that the restoration of the church as a place of worship has rendered useless, and for which we should find a suitable space, since the study of those beautiful compositions would be profitable for our artists, who have the opposite defect to the Germans, in not generally sinning through an excess of ideas. But Chenavard, being a prudent fellow, never quits the charcoal for the brush. He ‘writes’ his thoughts, and chooses not to paint them. However, if some day one wished to execute them on the walls of a building, one would not lack for expert practitioners capable of colouring them in a fitting manner.

I have no intention of compiling here an inventory of the Berlin Museum, which is rich in paintings and statues; that would take me well beyond the scope of a mere paragraph or two. One encounters there, more or less well-represented, all the great masters that could honour a royal gallery. But what is most remarkable is the extensive and comprehensive collection of the primitive painters of all countries and all schools, from the Byzantines to the artists who preceded the Renaissance; the old German school, so unknown in France, and yet in many respects so interesting, can be studied there more readily than anywhere else.

A rotunda, there, contains tapestries after drawings by Raphaël, the cartoons of which are in England, at Hampton Court (‘The Acts of the Apostles’; the cartoons are now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; the tapestries themselves are not extant).

The staircase of the new museum is decorated with those remarkable frescoes by Wilhelm von Kaulbach, that the art of engraving and the Universal Exhibition introduced to France. I recall the cartoon of The Tower of Babel, and we all went to view, at Goupil’s gallery, his poetic Battle of the Huns, where the struggle begun between corporeal bodies is continued between their souls, above a battlefield covered in corpses. The Destruction of Jerusalem is also well-composed though in too theatrical a style. It looks like a tableau from the end of the fifth act of a play, more so than is appropriate for the seriousness of fresco. Homer is the central character of a panel that surveys Hellenic civilization; that composition seems to us the least happy of all. Other unfinished paintings represent significant eras of humanity, the last being well-nigh contemporary, because when a German starts to paint, universal history has to be represented; the great Italian masters needed far less to create masterpieces. But every civilisation has its particular tendencies, and this encyclopaedic style of art is one of the characteristics of our time. It seems that before departing on some new path of destiny, the world feels the need to record a synthesis of its past.

These compositions are separated by arabesques, emblems, allegorical figures relating to the subject, and are surmounted by a frieze, in grisaille, full of ingenious and charming patterns.

Kaulbach searches for the correct tone, and if he fails to find it on every occasion, he at least avoids too unpleasant a dissonance; he employs reflections, transparencies, luminous highlights, flickering touches, and his fresco-work sometimes resembles paintings by Francesco Hayez or Théophile Fragonard. He knits together tones where one broad local tint would suffice; he pierces, with untimely vigour, the wall that he should simply cover; because fresco is a kind of tapestry, and should not disturb the architectural line through depth of perspective — all in all, Kaulbach is more concerned with the execution of his art than the pure thinkers, and his painting, though it concerns humanity, still remains human.

The staircase, of colossal size, is decorated with casts taken from the most beautiful of ancient statues; on the walls are displayed the metopes of the Parthenon, the friezes of the Temple of Theseus and, on one of the landings, the Pandroseion with its Caryatids, strong and tranquil in their beauty. All this has a rather grandiose effect.

And what of the inhabitants, you will say? You have only talked about buildings, paintings and statues; Berlin is not a city empty of people. No, doubtless, but I only halted for a day there, and was unable, especially since I was ignorant of the German language, to conduct any profound ethnographic study. Today there is no longer much visible difference between one group of people and another. All have donned the uniform dress of civilisation; no particular colouring, no special fashion in clothing tells you that you are other than at home. Berliners encountered in the street, or on the promenade, are not unique in their description, and the strollers on Unter den Linden exactly resemble those on the Boulevard des Italiens.

The former promenade, lined with magnificent hotels, is planted, as its name suggests, with European lime trees; trees ‘whose leaf has the shape of a heart,’ according to an observation by Heinrich Heine, a feature which has made it a favourite place for lovers, and a focal point for rendezvous.

At its entrance stands that equestrian statue of Frederick the Great, a scale model of which appeared at the Universal Exhibition.

Like the Champs-Elysées in Paris, the promenade leads to a triumphal arch surmounted by a chariot drawn by a bronze quadriga. When one has passed the triumphal arch, one emerges into a park that adequately corresponds to our Bois de Boulogne.

The Tiergarten in Berlin - Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, 1772

Rijksmuseum

At the edge of this park, shaded by large trees, which possess the intense verdancy of Northern vegetation, and are refreshed by a river’s meanders, lie gardens full of flowers, in the depths of which one sees lodges and summer-houses. These are neither chalets, cottages, nor villas, but Pompeian houses, with their four-columned porticos and their antique red panels. Greek taste is in great favour in Berlin — on the other hand, the Renaissance style, if fashionable in Paris, seems much disdained there, since I saw few buildings in that style.

Night was falling, and after hastily visiting a zoological garden, whose inhabitants were lying down, with the exception of a dozen macaws and cockatoos squawking on their perches, waddling about, and flourishing their crests, I returned to the hotel to pack my trunk and wait, at the station for the train to Hamburg, which was leaving at ten o’clock; this thwarted my design of attending the Opera to hear Les Deux Journées, the opera by Luigi Cherubini, and see Louise Taglioni dance the Sevillana.

What! But a single day in Berlin! — In travelling, there are only two ways of proceeding, by means of an instant trial or a long study. I was short of time. Deign to settle, then, for a simple fleeting impression.

Chapter 2: Hamburg

To describe a night journey by rail is no easy thing; one speeds along like an arrow whistling through the clouds; there is no more abstract way of travelling. I traversed provinces, and kingdoms, unaware. From time to time, through the carriage window, a comet appeared which seemed to rush towards the earth, with head lowered and hair outspread; a sudden glow of gaslights dazzled our eyes, filled with the golden dust of slumber; the light of a bluish moon gave a magical aspect to a landscape doubtless quite dull during the daytime. In all conscience, I have little to add, and it would scarcely amuse you were I to transcribe here, from the timetable, the names of the localities past which the train from Berlin to Hamburg carried us.

It is seven in the morning, and here we are in this good Hanseatic city of Hamburg: the city is not yet awake, or at least is rubbing its eyes while stretching its arms — while they prepare my breakfast, I set out at random, as is my habit, without guide or cicerone, chasing the unknown.

The Hôtel de l’Europe where I stayed is located on the quay by the River Alster, a basin at least as large as Lac d’Enghien (north of Paris), and, like it, populated by tame swans.

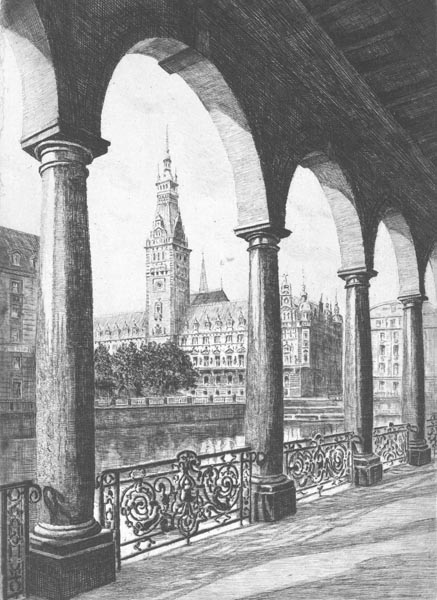

View from the Alster Arcade of the City Hall, in Hamburg - Anonymous, 1843

Rijksmuseum

The Alster basin is bordered, on three sides, by magnificent hotels and houses, in the modern style. A dam, topped by trees, and dominated by the silhouette of a windmill, occupies the fourth side; beyond extends a vast lagoon.

On the busiest embankment, a café, painted green and built on stilts, juts out into the water like that café on the Golden Horn in Constantinople where I smoked so many chibouks while watching the sea-birds fly overhead.

At the sight of this quay, this basin, these houses, I experienced an indefinable sensation. I seemed to have known them already. A vague memory emerged from the depths of my memory; had I visited Hamburg without knowing it? Certainly, none of these things seemed new to me, and yet I was surely seeing them for the first time. Had my mind retained the imprint of some painting, or photograph? Not at all.

While I was searching for a philosophical reason for this reminiscence of the unknown, a recollection of Heinrich Heine’s face suddenly presented itself to me, and I understood. Often the great poet had spoken of Hamburg in those eloquent words of which he possesses the secret, and which evoke the reality. In his collection of travel writings, Reisebilder, he describes that café, the pond, and the swans, and also the bourgeoisie of Hamburg traversing the path; what a portrait he makes of them! He invokes it all again in his poem Deutschland, and all this in so lively a manner, so delicately etched in relief, so evocatively, that direct perception conveys nothing more.

I took a turn around the pool, accompanied, graciously, by a swan as white as snow, and so beautiful as to make one believe that Jupiter, aiming to seduce some innocent Leda from Hamburg, was feigning, the better to disguise himself, to sample the traveller’s breadcrumbs.

At the end of the pool, to the right, is a sort of garden or public promenade dominated by an artificial mound like the labyrinth of the Jardin des Plantes. The garden visited I retraced my steps.

In every city there is a beautiful neighbourhood, a new neighbourhood, a wealthy district, a fashionable district, of which the inhabitants are proud, and where servants carry themselves with pride. The streets are wide, drawn with a rule, and intersecting at right angles; pavements of granite, brick, or bitumen border the streets; gas-lamps are everywhere. The houses look like hotels or mansions; their architecture is classically modern, their impeccable whitewash, their varnished doors with gleaming brass fitments, fill the city councillors, and lovers of progress, with joy. All is clean, correct, healthy, full of air and light, and reminiscent of Paris or London — here stands the Stock Exchange! It is superb! As fine as the Bourse in Paris! I liked it well, and what’s more, I could smoke there; quite an advantage. Further on are the Palais de Justice, the Bank, etc., etc., built in the familiar style that philistines of every country adore. But hardly what the artist seeks.

Doubtless this mansion must have been expensive to construct, it provides all possible luxury and comfort. One feels that the mollusc within such a shell must be a millionaire; but permit me to prefer that old house with projecting stories, a roof of disordered tiles, and small but characteristic details revealing the existence of previous generations. To be interesting, a city must seem to have been lived in, and human beings to have granted it a soul, so to speak. What makes these magnificent streets so cold and boring is that they have not, as of yet, been imbued with human vitality.

Leaving the new district, I plunged deeper into the maze of older streets, and soon had before me the picturesque and characteristic Hamburg, a real and ancient city, with a medieval charm capable of appealing to a Richard Parkes Bonington, a Eugène Isabey, or a William Wyld.

I walked slowly, pausing at every street corner so as not to lose any of the details, and a walk has rarely amused me more. The houses, with denticulated or scrolled gables jutting out from their overhanging stories, exhibited a row of windows, or rather a single window, with glass panes separated by carved timbers. At the foot of each house, cellars and basements yawned, with steps that the entrance gates spanned like drawbridges. Wood, brick, half-timbering, stone, slate, sufficiently varied as to satisfy the colourist, covered the scant spaces left free by the windows of the facades. All this was covered by steeply sloping roofs, clad in red or purple tiles, or coated planking, and decorated with dormer windows. These steep roofs function well in northern weather; the rain trickles down them, the snow slides away; they harmonise with the climate, and there is no need to clear them in winter.

It was a Saturday. Hamburg was recovering from the week. Maids, perched on high, were cleaning the windows, and the frames, which opened outwards, projected on either side of the street; soft vapours, gilded by the sun’s rays, misted the perspective, and a warm light traversed the tiles above the facades of the houses thus profiled. You could scarcely imagine the rich tones, precious, and strange, that the panes of glass acquired, set as they were one behind the other, amidst the rays of sunlight darting obliquely from the end of the street. The windows of green bubble-glass open on mysterious interiors, akin to those in which Rembrandt liked to house his alchemists, which offer nothing warmer, more transparent, more splendid to the eye beneath the dark glaze of his paintings.

Naturally, when the windows are closed, these unusual effects vanish; but there are still signs and notice-boards, whose lettering and symbols command the attention of the passerby, projecting from walls, and invading the public highway. Strict design would undoubtedly prohibit such unaligned adornments; but all these additions break the lines, entertain the eye, and vary the view with their unexpected angles. Now, it is a sign made of coloured glass, which the sunlight infuses with rubies, topazes and emeralds, advertising an optician’s shop or a confectioner’s; now, hanging from a locksmith’s signature writ large, a lion, holding in one set of claws a compass, and in another a mallet, the emblem of some coopers’ guild; elsewhere it is a copper basin above a barber’s shop, shiny enough to play the role of the famous helmet of Mambrino (see Cervantes’ ‘Don Quixote, XXI’), or a board on which are painted oysters, crayfish, herrings, soles, and other seafood designating a fishmonger, and so on.

Some houses have ornate doors, with rustic columns, and vermiculated bosses, notched pediments, chubby caryatids, small angels, little cherubs, large chicory-flowers, and rocailles, all coated with a coloured wash probably renewed every year.

There are tobacco-sellers beyond count in Hamburg. Every two or three steps, one sees the figure of a black African slave, naked to the waist, cultivating the precious leaf, or that of a great lord, costumed like a Carnival Turk, smoking a colossal pipe. Cigar boxes form the ornamental motif of the storefront, with their stickers and their more or less misleading inscriptions, arranged in a certain symmetry. A very small quantity of tobacco must remain in Havana, if one believes these displays so rich in noble provenance.

As I mentioned, it was early. Servants, kneeling on the porch steps, or hanging from window-sills, were carrying out the Saturday cleaning. Despite the lively breeze, the sturdy arms they displayed were bare to the shoulder, tanned, reddened, and whipped to that vermilion hue which often surprises in paintings by Rubens and is explained by the bite of the air joined to the action of water on pale flesh; young girls of the petty bourgeoisie, hair loose, décolletté, and with arms exposed, exited to purchase provisions; I shivered in my overcoat on seeing them so lightly dressed. A strange thing: northern women wear low-cut dresses, and go about with their heads and arms bare, while southern women cover themselves in jackets, wraps, pelisses, and warm clothing.

To heighten my pleasure, the mode of dress which the traveller is obliged to search for today, often without success, appeared openly to my gaze in the streets of Hamburg in the apparel of its milkmaids, somewhat akin to the Tyrolean water-carriers in Venice. The costume consists of a skirt riding the hips, and pleated with very small pleats, held by transverse threads so as not to flare above the waist, and a cloth jacket in green, black, or blue, buttoned at the cuffs. Sometimes the skirt is striped lengthwise, sometimes it bears crosswise a wide strip of plain fabric or velvet. Blue stockings, which a fairly short petticoat reveals, and clogs with wooden soles, complete their attire, which is not lacking in character; while the headgear, is quite singular: over the hair, gathered at the nape of the neck, with a ribbon tied in a bow resembling a big black butterfly, is placed a straw hat in the shape of an inverted hollow plate, cut and shaped to allow for balancing a jug or some other burden there.

Most of these milkmaids are young, and their costume renders almost all of them pretty. They carry their milk pails in a rather original way. From a sort of yoke, splayed about the neck, and hollowed out beneath to fit the shoulders like a mould, which is painted bright red, hang two buckets of the same colour acting as a counterweight on each side of the bearer, who strides along, upright and alert, carrying her double burden. There is no better orthopaedic method that could be employed than this manner of transporting heavy things; these milkmaids have an admirable air of ease, balance, and aplomb.

Continuing my random perambulations, I reached the maritime district of the city, where canals replace streets. The tide was out, and boats lay stranded on the mud, revealing their hulls, and lying at angles to delight the watercolourist.

Soon the water began to rise, and everything began to move — I recommend Hamburg to those artists who seek to walk in the footsteps of Canaletto, Francesco Guardi, and Jules Romain Joyant; they will encounter, at every step, motifs as picturesque and far fresher than those which they look to find in Venice.

The forest of salmon-coloured masts, with its thousand ropes, and tanned sails drying in the sun, the tarred sterns with apple-green trim, the yards and spars blinding the windows, the pulley-systems covered with a roof of planks, shaped like that of a pagoda, the cranes lifting loads from the boats and delivering them to the storehouses, the bridges which open to give passage to ships, the tufts of trees, the gables overlooked here and there by spires or church domes, all bathed in smoke, traversed by the sun’s rays, pierced by glittering light, bluish with fleeting vapours dispersing amidst the vigorous foreground, displays a host of novel effects, piquant and various. A bell- tower, clad in sheets of copper, springing from this jumble of houses and objects, reminded me, with its strange green tint, of the Galata Tower in Constantinople.

Allow me to note some random details: carts, consisting of a board and two flared drop-sides, are led along, in the style of those ‘Duke of Aumont’ carriages, harnessed to two horses. The leather-booted driver rides one of his beasts, instead of walking beside it, as in France. When the cart is drawn by a single horse, the driver stands upright in the American style; the narrowness of the streets, and the necessity of waiting for some bridge, open for the passage of boats, to be lowered, cause numerous delays and obstructions, which the phlegmatism of both bipeds and quadrupeds saves from proving hazardous. The postmen, dressed in crimson greatcoats of antique shape, attract the traveller’s gaze by their eccentric appearance. It is so rare to see the colour red amidst our modern civilisation, that friend of neutral shades, the idea of which appears to be that of rendering the painter’s profession untenable!

In the market I passed through, green vegetables and green fruit predominated. As has been said, cooking apples are the only fruit that ripens well in cold countries. On the other hand, flowers abounded; there were hosts of wheelbarrows filled with baskets, all fresh, bright, and fragrant. Amongst the country-folk who sold these various foodstuffs, I noticed a few dressed in rounded jackets and short trousers. They are natives, as are the milkmaids, of one of those islands in the Elbe where the old traditions are maintained, and whose inhabitants only marry among themselves.

View of the Großneumarkt in Hamburg - Thomas Higham, 1828

Rijksmuseum

Near the market, I saw a flesh-coloured omnibus, scheduled to ply between central Hamburg and Altona (the westernmost suburb). Its construction differed from that of our omnibuses. The front part was a sort of coupé, adorned with a glass mantle which folded down, thus, protecting travellers from the wind and rain, without obscuring their view of the route; the body of the vehicle, pierced with windows, was occupied by two side benches, and, at the rear, an extension of the sides and the imperial above sheltered the driver and allowed one to ascend or descend under cover. These are pleasant little observations, you may say. Tell us instead how many barrels the port handles; in what year Hamburg was founded; and how many souls it contains. I know absolutely naught of such matters, while the first traveller’s guide you consult will provide the answers; but, without my comments, you would never have known that flesh-coloured omnibuses existed in that good Hanseatic city.

Since we are addressing the singular features of Hamburg, let me not forget to note that on the façade of certain stores one sees the following inscription: Magasin de Galanterie. Grand assortiment de delicatesses (Haberdashery Store. Wide Assortment of Delicacies). ‘What!’ I said to myself, most intrigued, ‘so gallantry is a commodity, now, in Hamburg, and delicacies are sold over the counter! Is that by weight or length; in boxes or bottles? One must possess a truly mercantile spirit to sell such articles!’ — a closer more-detailed inspection led me to realise that the ‘gallantry’ boutiques, within, merely stocked novelties and attractions, to fill the shelves, while it was the delicatessen shops, there, that sold things to eat.

While wandering the streets, an idea occupied my thoughts. Rabelais often speaks of bottarga (the salted and dried roe sacs of the grey mullet) and smoked-beef from Hamburg, which he praises as wonderfully designed to raise a thirst, and I thought to find mountains of these products piled up in the storefronts of the delicatessen shops, but they no more sell smoked beef from Hamburg in Hamburg, than they do Brussels sprouts in Brussels, Parmesan cheese in Parma, or Ostend oysters in Ostend. Perhaps one could find some at Wilkens Keller, the Restaurant Véry (in Paris, owned by Jean-François Véry) of the place, where you can ask for salangane-swifts’ bird-nest soup, or mock-turtle in which no calf’s-head is involved (presumably the original green-turtle soup), Indian-style curry, elephant’s feet with chicken, haunch of bear, buffalo hump, sterlets from the Volga, ginger from China, rose-conserves, and other cosmopolitan delights. Seaports possess this feature, that nothing, there, surprises; they are the places in which eccentrics should stay, if they wish not to be noticed.

As the hour advanced, the crowd became more numerous, and women were in the majority. In Hamburg they seem to enjoy a great deal of freedom. Very young girls go to and fro alone without a thought and, remarkably, the children take themselves to school, satchel under one arm, and slate in hand; free to do as they wished, back home, they would be playing boules, hopscotch, or tag.

Dogs are muzzled in Hamburg all week, except on Sunday, when they can bite at will. They are licensed and seem to be cherished; but the cats there seem sad and misunderstood. Recognising me as a friend, they cast looks full of melancholy towards me, and said, in their feline language, to which familiarity has long granted me the key: ‘These philistines, occupied in making money, look down on us, yet we have pupils yellow as gold coins. Like fools, they think us only good for catching rats, we the wise, the dreamers, the independent spirits, who spin our mysterious spinning-wheels, while slumbering on a prophet’s arm. Pass, we allow you, your hand over our backs shedding sparks of electricity, and tell Charles Baudelaire that his sonnet is beautiful in which he deplores our sorrows.’ (See Baudelaire’s poems ‘Le Chat’ and ‘Les Chats’, first published in ‘Les Fleurs du Mal’, in 1857.)

Chapter 3: Schleswig

The suburb of Altona to which the flesh-coloured omnibus I have described runs, begins in an immense street with wide side-alleys lined with little theatres and fairground booths, akin to the Boulevard du Temple, in Paris, a strange memory to invoke on the border with a State owning to Hamlet, Prince of Denmark! It is true that Hamlet loved actors and offered them advice and criticism, much like a newspaper columnist.

At the end of the district of Altona is the railway station; the track connects it with Schleswig where I had business.

Business, in Schleswig! — Yes — What is so surprising? I promised, if ever I passed through Denmark (Schleswig-Holstein was a part of Denmark, until annexed by Prussia and Austria in 1869), to visit a beautiful chatelaine of my friend’s (the chatelaine was Joséphine von Ahlberg, née Bloch, the Parisian ex-artist’s model known as ‘Marix’. She had married Carl Hermann von Ahlberg, who had died in 1855), and needed to gain the necessary information in Schleswig as to how to reach Ludwigsburg, which is not far from it (twenty miles or so, near Loose, Schleswig-Holstein), only two or three hours by carriage.

So here I am, entering the post-chaise, somewhat fortunately, having had great difficulty in making the people at the ticket-office comprehend where I wished to go, since in Schleswig the German dialect is complicated by an admixture of Danish. Fortunately, our companions on the road, very distinguished young people, came to our aid by means of a Teutonic form of French quite similar to the language Balzac deploys in La Comédie Humaine to render the speeches of Wilhelm Schmucke and the Baron de Nucingen, but which sounded with no less delightful a musicality in our ears. They wished to serve me as guides. When one is in a foreign country, reduced to a state of deafness and muteness, one cannot help but curse whoever possessed the idea of raising the tower of Babel and bringing about, through pride, the multiplicity of languages. Seriously, now that the human species circulates like a generous flow of blood through the arterial, venous, and capillary railway networks of all regions of the globe, a congress of people should come together and decide the adoption of a common idiom — French or English — which like the Latin of the Middle Ages would act as a common, universal and, so to speak, human, language; one would automatically be taught it in schools and colleges; though every nation, be it understood, would still retain its native and individual language.

But let us leave this dream, which will be realised, of itself, in the near future, by one of these means that necessity alone knows how to invent, and, while waiting for it to be accomplished, let us congratulate ourselves on whatever of the noble language of our homeland is either spoken, or at least stuttered, in whatever place we find ourselves, by anyone who prides themself on being well-bred, educated and intelligent.

Night falls quickly, at the end of those short autumn days even briefer there than in France, and the landscape, otherwise quite flat, soon disappeared in the vague half-light which changes the shape and character of objects. I might as well have slept, but I am a conscientious traveller and, from time to time, I stuck my head out of the carriage-window, to try and disentangle some view or other, here and there, in the grey glow of the rising moon. — Fatal imprudence! I had not secured the chin-strap of my cap, and the fairly cool wind, increased by the speed of the train travelling at full pace, snatched it from me with a dexterity worthy of the magician Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, or of Macaluso, the Sicilian conjurer. For a moment I saw its black disk spinning like a star torn from its orbit; at the end of a few seconds, it had dwindled to a point in space, and I remained, dishevelled, and somewhat pitiful in appearance.

A young man, seated before me, began gently laughing, then, regaining seriousness, opened his night-case and took out a small student’s cap, which he handed to me, begging me to accept it. It was not a moment to quibble as to its appropriateness, since I could not halt the train to seek other headgear, and besides the route seemed somewhat lacking in hatters.

Having thanked the obliging traveller as best I could I set it on my head, taking good care, this time, to secure the chin-strap, the narrow cap, which gave me the air of a senior (a ‘bemoostes Haus’ or ‘maison mossue’) from Heidelberg, or Jena, of thirty years of age or more. This incident, with its air of pathetic buffoonery, was the only one which marked our journey, and augured well as regards the hospitality of the country.

At Schleswig, the railway line extends a little beyond the station, and ends in the middle of a field, like the last line of an abruptly-interrupted letter, all to singular effect.

An omnibus took me aboard, with my luggage, and in the hope that it would inevitably lead us somewhere I allowed myself at least the appearance of confidence. The intelligent vehicle dropped me in front of the best of the city’s hotels, and there, as the journals of circumnavigatory voyages have it: ‘We had speech with the natives.’ Among them was a lad who spoke French sufficiently clearly that one could glimpse his meaning, and who, a much rarer thing, sometimes even understood what I said to him.

My name, written in the passenger register, provided a ray of light! Our hostess had been forewarned of my arrival, and someone was supposed to come and collect me, as soon as notice of my appearance was given; but as it was late, I had to wait until next day. I was served a hot and cold dinner of partridges, without candied sugar or confiture, and slept on the sofa, expecting to sleep not a wink between the two quilts that make up German and Danish beds.

The messenger sent forth the day before, did not return until quite late in the day, the distance between Schleswig and Ludwigsburg being twenty miles or so, which made forty for the round trip. He reported rather confusing news: the mistress of the castle was then at Kiel, or Eckernförde, or else she was in Hamburg, if not in England. It seemed sad to visit Denmark only to leave a dog-eared card saying: ‘I shall not be back this way’.

A telegram was sent in triplicate to three places, and, while waiting for an answer, I wandered around Schleswig, which has a very particular physiognomy. The city is spread widely, on each side of the main street to which other alleys attach themselves, akin to the basals and radials attached to the dorsal bone of a fish. There, are found fine modern houses; as always, they possess not the slightest character, while the more modest homes have a genuinely local character; the latter consist of a very low ground floor, about seven or eight feet high, over which a large roof of fluted red tiles hangs. Wide windows occupy the entire front; behind these windows, in porcelain, earthenware, or varnished pots, all kinds of flowers flourish without exception: geraniums, verbenas, fuchsias, and succulents. The humblest house is full of flowers like the others. In the shelter of this sort of scented jalousie, the women work at their knitting or sewing, while gazing from the corner of their eye into a carefully-placed mirror in which is reflected the rare passer-by whose boots echo on the paving stones. Cultivating flowers is one of the passions of northern lands; in the countries where they grow naturally no one pays them any attention.

The church in Schleswig had a surprise in store for me. Protestant churches are generally of little interest from an artistic point of view, unless the Reformed mode of worship takes place in a Catholic sanctuary diverted from its original purpose. Usually one encounters only whitewashed naves, whitewashed walls, unpainted limewood, without bas-reliefs, and rows of shiny, well-polished oak benches. All is clean, and comfortable, but scarcely beautiful. The church at Schleswig contains a masterpiece by a great but little-known artist; a triptych altarpiece in carved wood representing, in a series of bas-reliefs separated by finely-worked borders, the various dramatic scenes of the Passion.

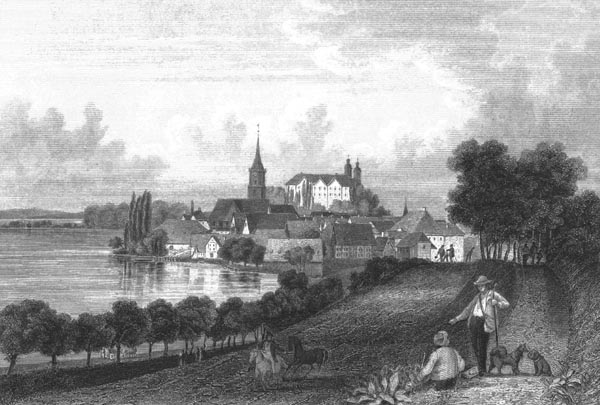

View of Plön, Schleswig-Holstein - Georg Michael Kurz, 1847

Rijksmuseum

This artist, worthy of being placed among sculptors like Michel Colombe, the Vischers (Peter Vischer the Elder and his five sons Hermann, Peter, Hans, Jakob and Paul), Juan Martínez Montañés, Pedro Duque y Cornejo, the Berruguetes (Alonso and Inocencio), and the Verbruggens (Peter I, Hendrik his son, and the former’s brother, Peter II) and other wood-carvers, was named Hans Brüggemann – a name little pronounced but worthy of being so.

In this regard, you may have noted how many sculptors, of equal and often superior talent, are less known than the painters. The weighty products of their art, linked to buildings and monuments, are not easily removed, are not commercial objects, and their severe beauty, devoid of seductive colour, fails to attract the attention of the crowd.

Around the church there are sepulchral chapels, of a noble funerary fancy, producing a fine decorative effect.

A vaulted room contains the tombs of the former Dukes of Schleswig, massive slabs emblazoned with coats of arms, and historiated with inscriptions not lacking in character.

Near Schleswig there are a number of vast saline ponds communicating with the sea. I walked the roadway, noting the play of light, and the patterns embossed by the wind, on those grey-tinted waters; sometimes I extended my walk as far as the castle, transformed to a barracks, and the public garden, a sort of miniature Saint-Cloud, with a stepped cascade adorned with dolphins and sea-monsters spouting nothing.

What a sinecure that Triton holds, in his Louis XIV basin! One could ask for nothing more. Tired of waiting for an answer that failed to arrive, and having exhausted the delights of Schleswig, I had a post-carriage harnessed and here I am, on the way to Ludwigsburg.

We drove for a long time, viewing to right and left sheets of water, extensive lagoons, on a road lined with rowan trees whose glistening red berries pleased the eye, their fiery tones brightened by the rays of the declining sun. Nothing was prettier than that avenue of trees with their crimson clusters; like an avenue of coral leading to the madrepore castle of an Undine.

The rowans were succeeded by birch, ash-trees, and pine, and we reached the post-house where there was no need to change the horses, but merely give them a feed of oats, while I myself enjoyed a mug of beer and smoked a cigar in a room with a low ceiling and transverse windows, in which serving-maids stood about talking with the postilions who puffed away at their porcelain pipes; their poses and the play of light being sufficient to inspire an Adriaen von Ostade or an Ernest Meissonier.

Meanwhile twilight descended, then the night, if bright moonlight can be called night; the journey, longer than I had thought at first, was lengthened, moreover, by my impatience to arrive, as the horses continued their peaceful trotting, accompanied by friendly caresses on the rump from a phlegmatic postilion.

At each cluster of houses, whose lights shone like eyes through gaps in the foliage, I leaned out to see if I had reached my goal, since I possessed a visiting-card, engraved in intaglio, adorned with a vignette of the castle to which I had been invited for a few days, long ago; but the end of our journey seemed to recede, and the postilion, who no longer appeared very sure of his route, exchanged two or three words with the country-folk he encountered, or whom the noise of the wheels attracted to their doors.

The road, however, was magnificent, sometimes shaded by large trees still full of leaf, sometimes surrounded by bright hedgerows, which the moon riddled with her thousand silver arrows, and the shadows of which drew the strangest silhouettes on the ground. When the foliage, parting, rendered the sky visible, I could see Donati’s Comet, flamboyant and dishevelled, stars mingling with the golden hairs of its tail.

I had seen the comet in the sky above Paris a few days before, its light weak, vague, and uncertain! In a week, it had grown in such a fashion as would have terrified an era more superstitious than our own. (Donati’s comet was visible with the naked eye from mid-August to late October 1858, brightening in September, and closest to Earth on the tenth of October. Gautier had left Paris on the fifteenth of September. The moon was full on the twenty-third.)

In the vague blue glow, transected by deep pools of shadow which the horses entered shivering, everything took on a strange and fantastic aspect. The road, following the undulations of terrain, climbed and descended; hedges or trees hid our view of the horizon, and I felt completely disoriented. At one moment, I thought we had reached the end of our journey. A dwelling of beautiful appearance, silvered by a shaft of moonlight, stood out against a background of dark greenery, its reflection glittering in a nearby sheet of water; it sufficiently resembled the description of Ludwigsburg, but the postilion paid it little attention. Soon the carriage entered an avenue of centuries-old trees which lined the avenue to the mansion-house. On the left, water shimmered, and buildings in considerable numbers emerged through the branches, but as yet I could discern nothing. Suddenly the post-chaise made a turn, and the wheels echoed on a bridge crossing a wide moat. At the end of this bridge a low arch opened into a sort of bastion, which lacked only the portcullis; the entrance crossed, we found ourselves in a circular courtyard akin to the interior of a dungeon, and a second arch swallowed the carriage, in darkness.

All this, glimpsed in moonlight, and bathed in shadow, had a feudal and medieval air, a fortress-like appearance that worried me a little. Had the postilion, by chance, made a mistake? Had he led us to the castle of Harald Hárfagri, Norway’s first king, or of Björn Eriksson of the glittering eye? All became legend and fantasy.

Finally, we emerged into an immense area bordered at the far end by large buildings, forming an elongated semicircle, the nature of which the night prevented us from comprehending, but which took on a rather formidable appearance in the darkness.

The string to this bow, which seemed to represent the interior of a rounded fortification, was formed by the manor itself, whose imposing and wholly isolated mass emerged from a sort of lake to display its canted roof, and high facade which the moon glazed with its bluish light, causing windows to gleam here and there like the scales of a fish.

Though it was not yet late, all seemed asleep in the château. One might have thought it a fairy-tale palace, beneath a burden of enchantment, awaiting the prince charged with breaking the spell.

The postilion tethered his horses in front of a bridge, which must once have been a drawbridge, and lights then appeared in the windows; the door opened a little way, servants approached the post-chaise, spoke a few words in German, and took my luggage while gazing at me with surprise mixed with a degree of distrust. It was impossible for me to question them, and I was unsure as to whether we really were at Ludwigsburg.

The bridge crossed a second moat, filled with water etched with a few touches of silver, and led to a portico flanked by two granite columns which granted access to a large vestibule, paved in black and white marble, and covered with oak panelling whose pilasters were topped with gilded capitals. Pictures of stag-hunting hung on the walls, and two small cannons of polished copper pointed their mouths at me. This seemed rather inhospitable — cannons in the vestibule in the nineteenth century! I was led to a living room furnished with all the accoutrements of modern elegance.

Among the paintings which adorned it was a portrait, the work of a famous painter, representing the mistress of the house in oriental costume, which I recognised immediately. I was not deceived. A young governess, who descended to receive us, spoke to me in a language I did not know, seemingly quite alarmed at our nocturnal invasion. I indicated the portrait while repeating the name of its subject, and handed her the visiting-card. All mistrust then vanished, and a charming little girl of about ten years of age (Marie von Ahlefeldt), who had held back until then, considering me with the deep dark gaze of childhood, stepped forward and said: ‘Moi, je comprends le français’ (‘Myself, I understand French’). I was saved. The mistress of the house, absent for two days, was to return next day, and had given orders accordingly.

I was served supper, and then escorted to my room via a monumental staircase which could have swallowed a Parisian house with ease. The servant placed two candlesticks, decorated with those German candles as long as tapers, on the table and withdrew.

The room, part of an apartment of three or four rooms, looked like a chamber out of some fantasy; on the fireplace, imp-like cherubs, lit by a reddish glow, heated themselves on the surfaces of a brazier with pretensions of allegorically depicting winter; through the windows, despite the candles, the moon cast a pale shaft of light which stretched mysteriously across the floor.

Moved by a sentiment akin to that which makes Ann Radcliffe’s heroines wander the corridors of ghost-ridden castles lamp in hand, I performed before going to bed, a reconnaissance of the place in which I found myself.

At the rear of the apartment a kind of small living-room, adorned with a mirror, and furnished with a sofa and armchairs, failed to offer any nooks suitable for accommodating ghosts. Mezzotint engravings of Esmeralda and her goat (see Victor Hugo’s novel ‘Notre-Dame de Paris’ for Esmeralda, and her goat Djali; Marix had posed for Charles Steuben’s paintings on the subject in 1839, and 1841, the latter engraved by Jean Jazet) reassured me as to its modernity.

The room preceding my bedroom was more concerning. Old darkened canvases lined the walls. They depicted hounds, as formidable as those in the portraits of dogs by Louis Godefroy Jadin, with their names written beside them, and restrained by leashes held by black African servants. Those creatures, in the flickering candle-light, seemed to flourish their crescent-shaped tails, opening and closing ivory-fanged mouths while silently barking, and to tug at their collars ready to assault me. The Africans rolled the whites of their eyes, and one of the dogs, named Raghul, looked at me with a dark gaze.

The three rooms were bordered by a corridor, folding back on itself, of which one wall, forming a gallery, was hidden beneath portraits of ancestors and historical figures.

There were men with fierce faces, in folio wigs of the time of Louis XIV, with steel breastplates studded with gold nails and traversed by large sashes, their right hands resting on commander’s batons like the Commendatore’s statue in Mozart’s Don Juan, their helmet set next to them, on a cushion; and high and powerful ladies, in costumes of various reigns, making coquettish advances from beyond the grave, and rendering graceful, outdated gestures from the depths of their frames. There were imposing but reluctant dowagers, and powdered young women, in large court dresses, with corsets à échelle (with a ladder of descending bows) and vast cages bearing ample damask skirts, in pink or salmon colours and brocaded with silver, who indicated with a careless hand, coronets of precious stones on tables with velvet coverings.

These noble characters, pale, discoloured by time, took on a spectral and alarming appearance; some of the portraits’ tones had withstood the years better than others, and this uneven deterioration had produced the weirdest effects: a young countess, otherwise graceful, had retained, amidst her bloodless pallor, lively carmine lips and blue pupils of an unaltered azure; the mouth and the gleaming eyes made a phantasmagoric contrast with that deadly whiteness which was less than reassuring. Someone seemed to be gazing at one from behind the canvas as if from behind a mask.

Portraits, as numerous as those shown by Ruy Gomez de Silva to King Carlos, in Hernani (see Victor Hugo’s play of that name) extended to the corner of the corridor.

Arriving there, not without having experienced the slight thrill that summons up, even in the bravest, in a dark, unknown, and silent place, visions of those who were once alive, and whose forms thus represented have long since fallen to dust, I hesitated, on seeing that the corridor continued indefinitely, filled with mystery and darkness. The glow of my candle did not reach its depths, but projected onto the wall my grim silhouette which accompanied me like a shadowy servant parodying my movements with an air of lugubrious buffoonery.

Not wishing to confess to cowardice, I continued my perambulation. Arriving at about the centre of the corridor, at a place where a projection of the wall seemed to indicate the passage of a chimney, a vent with a grille caught my attention. Raising my candle to the opening, I distinguished the angle of a staircase which rose from the depths of the building, and ascended to God knows where. The colour of the plaster around the grille denoted that the opening had been created after the construction of the staircase, doubtless to reveal its secrets.

Clearly the château of Ludwigsburg was built like a stage-set for Angelo, Tyrant of Padua (see Victor Hugo’s prose drama of that name), and at night one might hear, as he did, ‘footsteps in the walls.’ (see Scene I)

The corridor ended in a securely locked door, more recent than the rest, and if I had known the legend attached to the room thus condemned, I would, certainly, have had bad dreams. Fortunately, I did not; however, it was with no slight feeling of pleasure that I saw pure daylight filtering through the window-blinds, at dawn.

The nocturnal phantasmagoria having vanished, the feudal manor revealed itself in the form of an old but modernised château. It was the spectre of the ancient house, returning to haunt the moonlight, that I had glimpsed the previous evening, and the effect I had felt had not been entirely an illusion. In this once-fortified arena, the peaceful life of our time had taken up its quarters without destroying its main outline, and so in the darkness my error was allowable. The tall buildings arranged in a semi-circle, and worthy of a princely residence, before serving as stables and outhouses, must have been part of the emplacements; the entrance, with its two low arches, its drawbridge changed into a fixed bridge, and its wide moat, seemed adequate to resist an assault still. Above the first doorway, a bas-relief eroded by time suggested a Christ on the Cross accompanied by female saints, watching over two rows of encrusted coats-of arms, in stone, set into the solid brick surface.

The manor house, surrounded by water on all sides, its thick vermilion walls built on foundations of bluish granite was adorned with a roof of purple tiles, and pierced by well-proportioned windows.

On the rear facade, in line with the primary entrance, a second bridge spanned the first moat, and a little further on, when one had crossed the intervening ground, another bridge spanned the second moat, which encircled the house like a belt.

Beyond that lay the garden. Tall trees in a vigorous old age, still retaining all their leaves despite the autumn, and artfully grouped, formed the backcloth to this magnificent stage-set. A vast grassy area, green as an English lawn, interspersed with clumps of geraniums, fuchsias, dahlias, verbenas, chrysanthemums, Bengal roses, and other late-flowering plants, extended, like a flooring of velvet, to a bower from which a long avenue of lime trees opened, leading to a leap which formed a boundary with the lush pastureland dotted with cattle.

A globe of burnished metal, set on a truncated column, completed the view, by adding a greenish colour of fresh-cut hay. It was in the German style, of which the chatelaine should not stand accused. There is a similar globe in the courtyard of Heidelberg Castle.

On the right, a rustic pavilion, festooned with clematis and birthwort (aristolochia), offered its sofas and armchairs made of knotty or curiously misshapen branches, and a series of glasshouses lifted their panes to the lukewarm rays from the south. These greenhouses, at different temperatures, were linked to each other. In one, orange-trees, lemon-trees, and limes, loaded with fruit at varying degrees of maturity, gave the pretence of flourishing in their native land, not of regretting, like the shivering Mignon, ‘the land where the lemon-trees grow’ (see Goethe’s poem, from ‘Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre’; note that Marix was the model for paintings by Ary Scheffer, depicting Mignon, exhibited in 1836, and 1839). In the next glasshouse, large cacti bristled with thorns, banana-trees spread their large silky leaves, orchids hung their frail overflowing garlands from lamp bases of pink clay. A third contained arborescent camellias the metallic foliage of which, studded with buds, shone; another room was reserved for rare or delicate flowers, layered in the sun, on tiers of planks; painted or gilded cages, adorned with glasswork, hanging from the ceilings, were populated by birds who, deceived by the heat, sang and chirped as if it were Spring. The final room, decorated with artificial trellises, served as a gymnasium for the château’s young children.

In front of the greenhouses, a small artificial rock, covered with wall-plants, simulated a sort of fountain whose basin was formed by the valve of a monstrous shell. What a size the mollusc, the primitive inhabitant of this conch, must have been, one capable of bearing Aphrodite over the azure sea!

Further on, some reddening peaches with velvety cheeks hung from the branches of their espalier, and pale Chasselas grapes, whose vine-stems only were exposed to the open air, finished ripening behind glass cases attached to the wall.

A fir-wood spread dark greenery along the garden-side, which led to a slender footbridge spanning a deep channel half-filled with water. I committed all to chance. We know that the lower branches of fir-trees lose their colour as the trees grow, lifting their verdant spires towards the sky. The whole floor of the wood looked like a preparation for a bitumen landscape to which the artist, interrupted in his work, had only had time to add a few touches of green. The sun, amidst the warm red shade, cast handfuls of gold, here and there, which bounced from branch to branch and scattered themselves over the brown earth, devoid, as always in fir-woods, of any moss, and bare of all grass. A sweet, aromatic fragrance, drifted from the trees, stirred by a weak breeze, and the forest gave forth a vague murmur, like a sigh from a human chest. The path brought me to the edge of the woods, where the ditch separated the gardens from the plain, over which cows and free-ranging horses roamed. I retraced my steps and returned to the château.

Sometime later, the little girl who spoke French came running to tell me that her mother had arrived; I told the lovely chatelaine of my nocturnal wanderings through her mansion and expressed my regret at not possessing a dwarf, to sound the ivory horn at the foot of the keep to greet her; she asked me if I had slept well, despite the fearful location of my room, and whether the ghost of ‘the lady who died of starvation’ had appeared to me in dream or reality.

‘Every castle has its legend,’ she said, ‘especially if it is old. You probably noticed the mysterious staircase one might have supposed to be a chimney; it leads to a bedroom which cannot be seen from the outside and descends to the cellars. In this room, a lord of Ludwigsburg kept a charming, and devoted, mistress hidden from all eyes, especially those of his wife. His mistress had accepted a life of absolute seclusion, in order to live under the same roof as the one she loved. Every evening, this lord of Ludwigsburg himself prepared a nocturnal meal that he bore, from the kitchens below, to the captive. One day, called away on some expedition or other, he lost his life, and the prisoner, no longer receiving her food, died of starvation – many years afterwards, during the work of repairing and remodelling the house, workmen unmasked the secret door, and found the skeleton of the lovely creature, crouched, at the foot of the stairs in a desperate pose, amidst scraps of rich fabric, and on ascending found her sumptuously furnished retreat, rendered, for the unfortunate woman, a tower more sinister than that of Ugolino, who at least had his four sons to eat (see Dante’s ‘Inferno: Canto XXXIII’). Sometimes her ghost walks by night through the corridors, and if she meets a stranger, she seems to beg for food with frantic gestures. I’ll assign you a less gloomy room this evening.’

Guided by the chatelaine, I visited the reception-rooms, decorated in the style of the last century; in the dining room, old massive silverware, and porcelain services in ‘Vieux Saxe’, gleamed behind the panes of curiously carved dressers. The huge living room, with five windows facing, displayed, on its gold and white woodwork, royal portraits, and from its ceiling descended rock-crystal chandeliers with transparent branches, and pierced leaves. Next door, a smaller, living room clad in green damask, offered nothing in particular, to the eye, except a portrait of an armoured lord, with fluttering sash, wearing round his neck the decorations of the Order of the Elephant, and the Order of Dannebrog (Danish orders of chivalry), and smiling graciously upon his own little Versailles. Inadvertently, the artist had posed him with his back turned away from his counterpart, a young well-powdered lady, in a full taffeta court-dress of apple green glazed with silver, which fact seemed to have annoyed him greatly, because he was half-turning his head over his shoulder. The young lady would have been very pretty if it were not for her nose, which possessed too aristocratic a curvature, descending towards her mouth and making her look like a parrot about to eat a cherry. Her soft and sad eyes seemed to deplore this caricature of a Bourbon nose, which spoiled her charming face, regardless of any effort the artist might have made to attenuate it.

As we were gazing attentively at her singular physiognomy, both charming and ridiculous despite her noble air, the lady of the house said: ‘There is also a legend regarding this painting; but rest assured, there is nothing terrible involved. If you sneeze in passing before the countess with the long nose she responds to you with a nod or a ‘God bless you’ like the portraits in an inn-room in fairy tales. Take care to avoid coryzas (the common cold), and the picture will give not a sign of life.’

The bedrooms contained large tapestry or damask canopy-beds, the bedheads resting against the wall so as to form an alleyway at each side. In accord with the antique fashion, the hangings of one of these consisted of large hand-painted designs in tempera, done on canvas and forming part of the panels, representing shepherds, in which the German artist had tried to imitate Boucher’s gallantry, a pretension which had produced awkward poses and strange effects of colour. — ‘Would you prefer this room?’ I was asked. ‘The rococo style is most reassuring, and will counter nocturnal terrors.’ I refused. I dislike seeing, around me, in silence, solitude, and the feeble light of a lamp or a candle, figures which seem to wish to detach themselves from the hangings and request the soul that the painter had neglected to grant them. My choice fell upon a pretty room, with a Persian canopy over a small modern bed, located at the corner of the castle and pierced by two high windows, which possessed, to its rear, no dark corridor or spiral staircase, and whose walls, when struck with the hand, seemed solid — the only drawback was that to reach it, one had of necessity to pass before the lady with the parrot’s beak, and I admit, without shame, that too polished a portrait is not to my taste; but I was not suffering from a cold, and the young countess could rest in peace, in her armorial frame.

What was most interesting, was a sixteenth century room of the mansion, which had been preserved intact, and made me regret that the owners of the castle thought it necessary, at the beginning of the last century, to renew the decoration of their apartments in the style of Versailles. One cannot imagine how despotically this style reigned throughout a fairly long period of time. The room was panelled with oak, the frames, of equal size, having been enhanced with a few delicate arabesques of faded gold, in harmony with the wood tones. Each panel contained an emblematic oil painting, accompanied by a motto in Greek, Latin, Spanish, Italian, German or French, matching the subject represented. There were moral, gallant, or chivalrous ones; those of Christians or philosophers; proud ones, or resigned ones; complaining, spiritual, or obscure ones. Concetti (conceits) competed with agudezzas (witticisms). Puns were pricked out pointedly; Latin, frowning with enigmatic concision, adopted a Sphinx-like air and looked askance at the clearer expressions of Greek. Petrarchan Platonism, the amorous subtleties of François Scalion de Virbluneau (the late sixteenth century poet, author of ‘Loyalles et Pudiques Amours’) confused one, with their explications of complicated and scarcely intelligible subjects. Historiated thus, from plinth to cornice, the room could have provided mottos for coats of arms in the lists, for garters from Tembleque, knives from Albacete, the stamps in an engraver’s boutique, the wrappers in a confectionery shop, or the kazoos (mirlitons) of the Saint-Cloud fair; but amidst a lot of nonsense, childishness, and convoluted expressions, some haughty phrase suddenly gleamed with deep and unexpected meaning, worthy of being inscribed on the bezel of a signet-ring or the blade of a sword.

I am not aware of a similar example of decoration. Certainly, one encounters legends and ciphers entwined with ornamentation, but nowhere are emblems and mottos adopted as a unique decorative theme.

Now that the castle is known to you, let us tour the surrounding area. Two ponies as black as ebony, harnessed to a light phaeton, shake their dishevelled manes and stamp impatiently at the end of the bridge. The chatelaine takes the reins in her beautiful hands, and off we go. We cross, away from any road and at full speed, immense pastures where three hundred cows or more graze and ruminate, posed in a manner to rejoice the painters of such subjects, Paulus Potter and Constant Troyon. The bulls, more placid than those of Spain, leave us free to pass, without any more than a glance, and begin to graze again. Horses, excited by the speed of the ponies, accompany us for a while, then abandon us to our own affairs. The fields extend around us, rippling in low undulations, delimited by earth embankments crowned with hedges — two posts linked by a crosspiece serve as a gate to each field, and one has to leap from the phaeton to raise the barrier lest the fiery little creatures jump it dragging the carriage behind them.

In less than twenty minutes we have arrived at a wood, massed on a height to most picturesque effect: elms, oaks, and ash-trees, with powerful trunks and bushy foliage, grow there in various attitudes, with the odd projections and vigorous contortions that the slope of the land produces. The wood is full of deer, and badgers excavate their setts there, almost certain of not being disturbed by human beings. Here and there pines, reminding us that we are in the North, stretch out their arms, and dart forth their sprays of sombre green.