Théophile Gautier

Travels in Italy (Voyage en Italie, 1850)

Parts XXVI to XXXI - Padua, Ferrara, Florence

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Part XXVI: Details concerning Venetian Customs and Habits.

- Part XXVII: Padua.

- Part XXVIII: Ferrara and Bologna.

- Part XXIX: Florence.

- Part XXX: The Piazza della Signoria.

- Part XXXI: Foreigners and Florentines.

Part XXVI: Details concerning Venetian Customs and Habits

The season was advancing. Our stay in Venice had been prolonged beyond the limits that we had set in the general plan for our trip. We had delayed our departure from week to week, from day to day, and had always found some good reason to stay. Despite the light mists that began to hover in the morning over the lagoon, despite the sudden downpours that forced us to take refuge under the arcades of the Procuracies or the porch of a church, despite the fact that when we travelled by moonlight on the Grand Canal, the cold night air sometimes forced one to raise the window of the gondola, and unroll the black cloth of the felze, we nonetheless turned a deaf ear to the threat of autumn.

We were forever remembering a palazzo, church, or painting we had not seen. It was indeed essential, before leaving Venice, to visit the white church of Santa Maria Formosa, containing the famous Saint Barbara Polyptych, the work of Palma il Vecchio in which the saint is so well-portrayed, so heroically beautiful; and the house of Bianca Cappello, to which is linked the memory of a Venetian love-story full of a romantic charm which is scarcely dispelled on seeing the signboard of a French milliner, Madame Adèle Torchère, who sells hoods and hats in the room where, leaning nonchalantly on the balcony, the beautiful Bianca dreamed; and then the strange and superb church of San Zaccaria, where there is a wonderful altar painting, gleaming with gold, by Antonio Vivarini and Giovanni d’Alemagna, commissioned by Abbess Elena Foscari and Prioress Marina Donato, and the tomb of the great sculptor Alessandro Vittoria,

Qui vivens vivos duxit de marmore vultus: who when alive brought life from the solid marble

a magnificent conceit of an epitaph justified however, in this case, by a host of statues.

Or something else delayed us, a forgotten island, Mazorbo, or Torcello where there is an interesting Byzantine Basilica, and Roman antiquities; or a picturesque facade on a little frequented canal, of which it was necessary to take a sketch; a thousand reasons of this kind, all reasonable, all excellent, yet none of which was the true reason, although we pretended to believe in them. We had yielded, despite ourselves, to that melancholy which grips the heart of even the most determined traveller, when leaving, perhaps forever, a longed-for country, a place where one spent beautiful days and more beautiful nights.

There are certain cities from which we separate as from a beloved mistress, our heart full, and tears in our eyes; they are a species of elective homeland where we are far happier than elsewhere, to which we dream of returning to die, and which appear to us in the midst of the sadness and complications of life like an oasis, an Eldorado, a divine city to which trouble is denied access, and the memories of which return on soaring wings. Granada, for me, has been one of these celestial Jerusalems that shine under a golden sun in the distant azure, like a mirage. I had been dreaming of it since childhood; I departed with tears, and with endless regret. Venice will be for me another Granada, regretted perhaps even more.

Has it ever happened to you that you have only a few days left to stay with a loved one? We gaze at them for a long time, fixedly, painfully, to engrave their features clearly in our memory; we saturate ourselves with their features, we study them every day, we notice their little unique markings, the mole near the mouth, the dimple in the cheek, or palm; we note the inflections and melodies of their voice, we try to retain as much as we can of the adored image that absence will steal from us, and that we will be able to see again only in our heart; we remain beside them, we seek to enjoy their presence till last second of the last minute; even sleep seems to us a theft committed on those precious hours, and endless conversations, conducted hand in hand, prolong themselves, without our noticing that the lamplight has faded, and the blue glow of dawn is filtering through the curtains.

We felt this in regard to Venice. As the moment of departure approached, she became more valuable to us. Her worth was revealed at the moment of loss. We blamed ourselves for having taken poor advantage of our stay, and bitterly regretted a few hours of idleness, cowardly concessions to the annoying influence of the sirocco. It seemed to us that we might have seen more, taken more notes, made more sketches, relied less on our memories: and yet, God knows, we had consciously carried on our profession of traveller; one found us in the churches, galleries, at the Accademia, in Saint Mark’s Square, at the Doge’s Palace, at Sansovino’s Library. Our exhausted gondoliers begged for mercy; we barely took time to swallow an iced coffee at Florian’s, a bowl of sea-lice soup and polenta pasticcio at the Gasthof San-Gallo or at the Capello-Nero tavern. In six weeks, we had worn out three eye-glasses, damaged a pair of binoculars, and lost a telescope. Never did any two people indulge in such visual debauchery. We were gazing for fourteen hours a day without cease. If we had dared, we would have continued our sessions by torchlight.

In our last few days there, we were possessed by a true fever. We made a general tour, at racing pace, recapitulating our visits, with the clear swift glance of those who know what they are looking at, and go straight to the object they seek. Like those painters who retrace in ink the drawings done with a lead pencil that they fear will fade, we defined with a firmer stroke the thousand lineaments pencilled in our memory. We viewed once more the beauty of the Doge’s Palace, made expressly for the set of a drama or an opera, with its great pink walls, its white serrations, its double register of columns, its Arabian quatrefoils; that Hagia Sophia of the West, the prodigious Saint Mark’s Basilica, a colossal reliquary of vanished civilisations, its golden cavern variegated with mosaic, and immense columns of jasper, porphyry, alabaster, and ancient marble, a pirates’ cathedral enriched with the spoils of the world; the Campanile which bears its golden angel so far aloft in the azure, as protector of Venice, and guards Sansovino’s Loggetta, sculpted like a jewel, at its foot; the Clock Tower, on whose large gold and blue dial the hours parade in black and white; the Library, of a truly Athenian elegance, crowned with slender mythological statues, a smiling memory of neighbouring Greece; and the Grand Canal bordered by its double row of palaces, Gothic, Moorish, Renaissance, Rococo, whose diverse facades amaze with their inexhaustible fantasy and perpetual invention of detail that a lifetime would not be long enough to study, that splendid gallery of works on which the genius of Jacopo Sansovino, Vincenzo Scamozzi, Pietro Lombardo, Andrea Palladio, Baldassare Longhena, Guglielmo Bergamasco, Giovanni de’ Rossi, Alessandro Tremignon, and other wonderful architects was deployed, without counting the anonymous, humble masons of the Middle Ages whose efforts are no less admirable.

We took a ride in a gondola, from the point of the Dogana to the tip of Quintavalle, to fix forever in our mind that magical spectacle, that painting which speech is powerless to render, and allowed out eyes to devour, with desperate attention, that mirage, that Fata-Morgana, close to disappearing forever from our sight.

Now, as I am nearing the end of my tale, perhaps already too long, whose pages the impatient reader will have quickly turned, it seems to me that I have said nothing, that I have only feebly expressed my enthusiasm and depicted my superb models badly. Every monument, every church, every gallery demanded a volume where I could barely supply a chapter, and yet I have only talked about what is visible; I was careful not to disturb the dust of old chronicles, revive extinct memories, repopulate the deserted palaces with their former inhabitants because that would be the work of a lifetime, and I have had to be content to draw, on plain paper, photographic impressions which have no other merit than their sincerity.

Often the temptation seized me, to summon the patricians and grandees from their portraits by Titian, Bonifazio Veronese, or Paris Bordone, and to call from their carved frames the beautiful women, with brocaded dresses and hair of burnt gold, depicted by Giorgione and Paolo Veronese and to animate the décor which has remained intact and which is only missing the actors. The magic names of Dandolo, Foscari, Loredan, Marino Faliero, and Queen Catherine Cornaro, have more than once excited my imagination. But I wisely resisted. What is the point of recreating admirable poems in prose?

My task was a humbler one. Reading the tales of travellers, we wished for more exact, more familiar details, noted on the spot, for more precise remarks regarding the thousand small differences which tell us we have exchanged countries. General descriptions and historical overviews, in a pompous style, repeat for us, more or less adequately, what we already know, but yield paucity of information about the shape of hats, the cut of dresses, the qualities and names of local dishes, in such or such a city. I have garnered my spoils from all this and described houses, taverns, thoroughfares, landing-stages, theatre-posters, marionettes, Chinese shadow-puppets, cafes, street-musicians, children, old men, and young girls, everything that is usually disdained.

Is it not of more interest to know how a Venetian grisette dresses, and how her shawl’s folds lie on her shoulders, than to hear told, for the hundredth time, of the beheading of doge Marino Faliero on the Giants Staircase, which, incidentally, was only built a century or two after his death? Do you think it a matter of indifference to learn if the coffee is filtered, or heated with pomace brandy in the oriental fashion, at Florian’s and La Costanza? This little cup of dark coffee made in the Turkish-style, does that not say everything about Venice’s past? And if I copy for you, here, quite foolishly, a list of names gathered from the shop signs and walls, whose unique character announces that we are neither in Paris nor London, names such as Ermacora, Zamoro, Fogazzo, Zenobio, Dario, Paternian, Farsetti, Erizzo, Mangilli, Valmarana, Zorzi, Condulmer, Valcamonica, and Corner Zaguri, among others, will you not be amused and delighted by the form and euphony of these appellations so local, so romantic, so fluid, and so soft on the ear? Will not this litany bring you some echo of Venetian harmony?

I am a long way still from having fulfilled this program, however restricted it may be. The architecture I have rushed through, without needing to follow Nicolas Boileau’s precept (See Boileau’s poem ‘Tout doit tendre au bon sens’ advising restraint) in neglecting the festoon and the astragal The streets, with their ever-renewed spectacle, have many times prevented us entering the houses, which is not always easy to achieve for travellers, we inconstant birds of flight, that like swallows arrive and depart with the summer. The manners and morals of Venetian society gain perhaps too little space in these sketches, and the portrait often hides the man. But, in this century of hypocritical cant, I lack the joyful, masculine freedom of Charles des Brosses’ Italian letters, and it is difficult to speak of morals without being immoral.

To recount one’s own adventures is to appear conceited; to relate those of others indiscreet. How can one, moreover, betray the intimate secrets to which one has been cordially admitted, and repeat in a book what one was told in a whisper? The external forms of life are today the same almost everywhere, especially in good company. Is it really necessary to say that cicisbeos (cavalieri serventi) no longer exist, and that Venetian women take lovers like the women of Paris, London or any other place? If one desires a more local observation, let us add that they often take one, but rarely two, a moral trait which extends to all of Italy; furthermore, it is not in good taste for the lover to be an Austrian; which is a way of resisting oppression and isolating the enemy.

Ancient families who are ruined live in retirement, and poorly, the owner of a palazzo dining, in a room lined with paintings by the great masters, on a dish of polenta, fried-food, or shellfish that his sole remaining valet has purchased from the inn.

In the summer, Venetians spend their holiday in country houses festooned with vines, on the banks of the Brenta, or on small rural farms in Friuli, and return to winter in Venice, like we Parisians. Aristocrats who no longer have country homes and cannot travel due to lack of resources, cloister themselves throughout the season and only reappear when it is acceptable to frequent Saint Mark’s Square. To all this, naturally, there are exceptions: there are Venetian women lacking a lover, and the wealthy. Here the opposite to what I have said applies. Parties, balls, and dinners are rare. Fear of spies and informers makes for a very reserved form of society. Such folk only entertain themselves behind closed doors, and among those they trust. Luxury hides itself, and pleasure is muted, which makes it difficult to observe their manners on the wing.

Perhaps those who are kind enough to read this will criticise the myriads of artists’ names piled up here, as if on whim. Truly, I have not done so to parade, in vain, my erudition: the Venetian school is of such fabulous richness that my prolixity seems to me more like laconicism and ingratitude. The tree of art formed, in this fertile city, branches so fully, so luxuriantly, is so loaded with fruit, that one has as much difficulty in following its ramifications as those of the genealogical tree of the Virgin in Saint Mark’s Basilica, which simply displays kings, saints, patriarchs and prophets.

Beyond the four greatest names who personify Venetian art, Giorgione, Titian, Paolo Veronese, and Tintoretto, there are entire families of admirable painters. From Anthony Vivarini of Murano, to Tiepolo in whom the line was extinguished, a thousand-leafed Golden Book would be needed. to write the unknown names worthy of glory. The least of these artists would find fame today as a great genius, and those who currently pride themselves on their fame would make a poor showing among that mass of talents.

In reporting on the Accademia, I expressed my complete admiration for the wonderful Gothic school of Vivarini, Marco Basaiti, Carpaccio, and Giovanni and Gentile Bellini, who, to all the feeling of Andrea Mantegna, Pietro Perugino and Albrecht Dürer, joined a use of colour which anticipates Giorgione. But among the painters of that decadence which appeared following the death of Titian, what fertility, what ease, what a riot of invention, spirit, and colour!

Transcribing their names, here, would not stir any fresh thoughts; it would be necessary to add an analysis of their immense and innumerable works, to characterise their diverse styles, reconstruct their biographies, and recompose them in every aspect. It is a task that I might yet undertake, and which I have often attempted; but for that I would need a ten-year stay in Venice; which alone might tempt me to try. In the churches, and palazzos, they covered every surface with frescoes and paintings; they took advantage of every space Tintoretto left free.

What is insufficiently recognised is that Venice is full of sculptures, bas-reliefs, marble and bronze figures of the rarest merit, works of statuary equal to its paintings, but of which we never speak, and which we unreasonably ignore. We have named some of these artists; but anyone wanting a complete list would be faced with a very long litany. Human fame is capricious! Who now speaks of Alessandro Vittoria, of Tiziano Aspetti, of Alessandro Leopardi, of Jacopo Sansovino and so many other sculptors?

Part XXVII: Padua

Now, at whatever cost, we were obliged to depart. Padua, the city of Ezzelino (Ezzolino II da Romano) and Angelo (see Victor Hugo’s play ‘Angelo, Tyrant of Padua’) called us. Farewell, dear Campo San Moisè, where we spent such sweet hours; farewell to the sunsets framing the Salute, the effects of moonlight on the Grand Canal, beautiful blondes in the public gardens, cheerful dinners under the vines of Quintavalle; farewell to the beautiful art and splendid painting, the romantic palaces of the Middle Ages, and the Greek facades by Palladio; farewell to the doves of Saint Mark’s; farewell to the gulls over the lagoon, bathing on the Lido beach, our journeys by gondola; Venice, ‘fare thee well, and if forever, still forever, fare thee well!’ in the words uttered by Lord Byron, from the height of his disdain, regarding an altogether different relationship.

The railway carries us off, and already the Venus of the Adriatic has plunged her pink and white form, once more, beneath the azure of the sea.

Disembarking from the gondola to take one’s seat in a railway carriage is a discordant action. The two seem unsuited to being experienced together. One, expresses the memory of romance; the other, prosaic reality. Zorzi de Cataro, the gondolier, delivers you, abruptly, to George Stephenson, the engineer. You were in Venice, now you are in England or America. O Titian! O Paolo Veronese! Who would have thought that your turquoise sky would one day be stained by the smoke from a British engine, and the azure of your lagoons would reflect the arches of a viaduct? So, the world changes; but here the contrast is more acute, for the forms of a vanished age have remained otherwise intact, and the present still wears the skin of the past.

We had already travelled this road, but in the reverse direction, when passing from Verona to Venice. A storm, bursting upon us with thunder, lightning, and rain, revealed to us a landscape of a particularly fierce and fantastic character, a landscape which, seen in normal weather, offers a series of well-cultivated stretches, traversed by canals, garlanded with vines climbing happily from one tree to another, its lovely horizons rising to blue hills and dotted with villas, whose whiteness stands out against the green of the gardens; a rich aspect, abundant and fertile.

For travelling companions, in the railway carriage, we had two or three monks of a pleasant disposition, and some young priests tall, thin, and of a youthful gracefulness, with oval blissful faces, of that uniform pallor, that deathlike hue, beloved by the Italian masters, and who resembled Gothic angels from Fiesole, plucked of their wings, their golden nimbus replaced by a tricorn or Basel hat. One of them was exactly reminiscent of Raphael’s portrait; but the dull eye lacked a spark, and the mouth opened vaguely in a foolish smile; otherwise, his looks would have been perfect. The sight of these seminarians made me reflect that adolescence does not exist in France. That charming transition from childhood to youth is totally absent at home. Between the hideous middle-school gamin, with large red hands, and lanky appearance, and the gaillard who shaves or sports a beard, there is nothing. The Greek ephebe, the Algerian yalouled, the Italian ragazzo, the Spanish muchacho, fill, with a young grace, and a beauty still hovering between the sexes, the gap which separates the child from the man. It would be interesting to research the reasons why we are deprived of this nuance; especially since there are plenty of English adolescents who are beautiful, though a little awkward perhaps because of the sailor-suits they are condemned to wear.

While reflecting on this problem of physiology, we arrived at the station: ten leagues are soon devoured, even on an Italian railway. There, a crowd of rascally coachmen were waiting for us, as we disembarked to their shouts and fierce gesticulations; they fought over the travellers and their luggage, like the cochers de coucou (cabriolet drivers) on the Place de la Concorde in Paris, or the robeïroou in Avignon on the Quai du Rhône. One seizes your arm, another a leg; you are lifted from the ground, and, if you are not robust enough to calm their ardour with a few good blows, you run the risk of being quartered like a regicide and dragged away by four porters.

About twenty carriages, cabriolets, berlingots, and other vehicles, were parked at the gate to the station. It surprised and delighted us to see horses and carriages. It was almost two months since, if we except that lone horse on the isle of Murano, that the sight had presented itself. We rented a carriage to bear us and our trunk as far as Padua, which is some way from the railway station. Unaccustomed as we were to all noise of this kind by our silent locomotion through Venice, the sound of the wheels, and the trampling of the horses deafened us, and seemed unbearable; we needed several days for it to become familiar.

Padua is an ancient city, standing proud on the horizon, with its bell-towers, domes, and old walls, over which many a lizard scampers, wriggling about in the sun. Placed too close to the larger city which draws all life to itself, Padua is dead, with a well-nigh deserted air. Its streets, lined with twin rows of low arcades, seemed sad, and nothing there recalled the elegant graceful architecture of Venice. Its massive, heavy buildings, bear a somewhat serious frown, and the deep dark porches of the houses looked like mouths yawning from boredom.

We were taken to a large inn, probably established in some ancient palazzo, whose large rooms, debased by vulgar use, had once kept better company. It was a long journey from the vestibule to our room via host of stairs and corridors; it needed a map, or Ariadne’s clue, to find one’s way around.

Our windows opened onto quite a pleasant view: a river flowed at the foot of the wall, the Brenta or the Bacchiglione, I am not sure which, since both provide water to Padua. The banks of this watercourse were lined with old houses and long walls above which trees projected; picturesque embankments, from which fishermen cast their lines with a patience which characterises them in all countries, and huts with nets and cloths hanging from the windows to dry, formed, beneath scratchy rays of light, a charming motif for a watercolour.

After dinner, we visited Caffè Pedrocchi, famous throughout Italy for its magnificence. Nothing is more monumentally classic. Nothing but pillars, columns, ovals, and palmettes, in the neoclassical style of Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine, all very grand and heavy with marble. What was most interesting were immense geographical maps, forming a tapestry of sorts, representing the various parts of the world on an enormous scale. This somewhat pedantic ornamentation gave the room an academic air, and we were surprised not to see a pulpit instead of a counter, and a professor in his robes instead of a master lemonade -maker. As to that, since Padua is a university town, it is good that the students can continue their studies while enjoying their iced-drinks or coffee.

Padua - Palace of the Royal University

The University of Padua was once famous. In the thirteenth century, eighteen thousand young people, a whole army of scholars, followed the lessons of its learned teachers among whom Galileo later figured; one of his vertebrae is retained as a relic, that of a martyr who suffered for the truth. The facade of the University is very beautiful; four Doric columns grant it a severe and monumental look; but solitude has established itself in many of the lecture rooms, in the rest of which, today, scarcely a thousand students are taught.

The theatre posters announced Rossini’s The Barber of Seville, and a traditional ballet: we had found our evening’s entertainment. The stage was very simple; the set seemed to have been painted by a maker of stained-glass on a spree, and recalled the cardboard cut-out scenery that children love to employ. But the actors had lively voices and that natural taste which characterises the least of Italian singers. Rosina was young and charming, and Basilio reminded me of Antonio Tamburini, as regards the depth of his baritone voice.

The aria La calunnia was sung as well as it might have been sung in a first-rate theatre. But the ballet was truly strange, composed in the most entertaining fossilised, antediluvian style in all the world; one found oneself transported, as if by magic, to the heyday of classical melodrama, to the world of Guilbert de Pixérécourt and Louis-Charles Caigniez in all its purity; the scenario was reminiscent of Les Aqueducs de Cosenza; Robert, Chef des Brigands; Le Pont du Torrent, and other masterpieces neglected by the current generation. It was a tale of a traveller lost in the woods, of an inn of cutthroats, of a sensitive young girl, of bandits dressed as Cossacks, with voluminous red trousers, formidable beards, and an arsenal of cutlasses and pistols in their belts, all involved in dances and regular fights with sabres and axes, as in the ancient and most glorious days of the Théâtre des Funambules, in Paris, before Champfleury (Jules Fleury-Husson) introduced literature to that naive form of theatricals.

A handsome officer underwent terrible events with the obligatory heroism of all young leaders, followed about by a wretched Jocrisse (comedy valet). By a singular act of the imagination, this Jocrisse was played as a soldier of the Old Guard, dressed in a ragged uniform, made up like a macaque, adorned with a red nose which emerged from a bush of moustaches and grey sideburns, and possessing piercing eyes buried beneath crow’s-foot wrinkles traced out in charcoal. The comedy depended on his perpetual fright at the slightest stirring of leaves, and his chattering teeth and colic nature of a soldier of the Old Guard, crazed by terror and cowardice. Transforming a model of bravery into an example of cowardice, and representing a curmudgeon of the Grande Armée as prone to the anxieties of a pantomime Pierrot, seemed to us a risky and fantastic idea in poor taste. My chauvinism was aroused, and I was obliged to reflect on the role in which the Cirque Olympique has cast the Prussians to calm my mind.

The next day we went to visit the cathedral dedicated to Saint Anthony, who enjoys in Padua the same adoration as Saint Januarius in Naples. He is the Genius loci (spirit of the place), the saint venerated above all others. He performed no less than thirty miracles per day, if Giacomo Casanova is to be believed. He well deserved his nickname of the miracle worker; his prodigious zeal slowed somewhat, yet the saint’s credit was nonetheless undiminished, and so many masses are ordered at the altar, that the powers of the cathedral priests and the number of days in the year are inadequate to satisfying the demand. To liquidate the account, the Pope allows Masses to be conducted at the end of each year, every one of which carries a thousandfold value; in that manner, Saint Anthony avoids bankrupting the faithful.

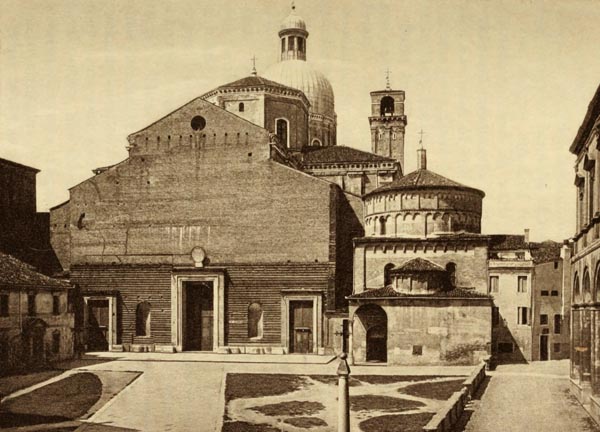

Padua - The cathedral

In the square which borders the cathedral, stands a beautiful bronze equestrian statue by Donatello, the first to be cast since antiquity, representing the condottieri leader, Gattamelata (Erasmo da Narni), a brigand who certainly did not deserve that honor. But the artist rendered him with a proud attitude and presence, and with a Roman Emperor’s baton, and that fully sufficed.

The Basilica of St. Anthony consists of an aggregation of domes and pinnacles, and a large facade in brick, with a triangular pediment, beneath which reigns a gallery with ribs and columns; three small doors,

pierced below high arches, front the three naves. The interior is excessively rich, cluttered with chapels and tombs of different styles. We saw examples there of the art of every era, from the naive religious and delicate art of the Middle Ages, to the excessive crumpled fantasies of the rococo style. We noted a most gallant chapel in the Pompadour manner; angels in wigs play dancing master’s violins, and perform an avant-deux (line dance) in the clouds. They lack only rouge and beauty-spots. What was more curious, was a black and white marble tomb, in the same playful and excessive taste. There Death plays the coquette, and smiles with bared teeth like Marie Guimard after a pirouette. Death presents an amorous appearance and gracefully advances fleshless shins. We had never imagined a skeleton could be so playful.

Fortunately, Giotto’s Genealogy of Jesus Christ, and a Madonna by the same painter, donated by Petrarch, correct this untimely cheerfulness somewhat, and Catholic seriousness regains its rights over tombs of the fourteenth and the fifteenth century, on which stiffened statues lie, gravely, with clasped hands. The cloister which adjoins the church is paved with funeral slabs, and its walls vanish under the mass of sepulchral monuments with which they are adorned; we read a number of the epitaphs, which were very beautiful. The Italians retain their ancestral secret as regards lapidary Latin.

The Abby of St. Justina is a huge basilica with a bare façade, and tediously sober and impoverished interior architecture. Good taste is always essential, but not when taken to such a point, and I prefer the wild exuberance and excessive contortions of rococo to such nothingness. A beautiful altar painting by Paolo Veronese (The Martyrdom of Saint Justina), highlights this poverty. If the church is dull and without character, one cannot say the same for the two gigantic monsters that guard it, lying on its stairs like faithful mastiffs. Japanese chimera never possessed a more frightening and dreadful appearance than those fantastic animals, a species of hideous griffin, with the rump of a lion, and the wings of an eagle, the foolish yet ferocious head, ending in a blunt beak pierced by oblique nostrils like that of the turtle. The monstrous creatures hold tight to their chests, beneath their claws, a warrior on horseback, caparisoned in medieval armour, whom they crush with a slow pressure, while gazing vaguely at something like the cow of which Victor Hugo speaks (see Hugo’s poem ‘La Vache’), and otherwise unconcerned by the convulsive efforts of the myrmidon crushed thereby.

What does the knight, caught with his mount in the relentless claws of these crouching monsters, signify? What myth is concealed in that dark sculptural fantasy? Do the pair of creatures illustrate some legend or are they simply sinister hieroglyphics indicating Fate? We could not guess, and no one knew or wished to tell us. The other day, in leafing through the album that Prince Alexey Soltykov brought back from India, we found an illustration showing, in the propylaea of a Hindu pagoda, an identical monster, also in the process of suffocating an armed man against its chest.

Whatever the meaning of these fearful creatures, I divine, there, vague confused memories of cosmogonic antagonism, and the struggle between the principles of good and evil: it is Ahriman conquering Ahura Mazda, or Shiva battling with Vishnu. Later, under the porch of the Cathedral of Ferrara, we saw two of these Chimeras, this time crushing lions.

One thing that should not be overlooked, when in Padua, is to visit the ancient Arena chapel, located at the bottom of a garden amidst dense and luxuriant vegetation, where one would certainly not expect it unless one were so advised.

The church interior was painted throughout by Giotto. No column, no rib, no architectural division interrupts the vast tapestry of frescoes; the general appearance is soft, azure, starry akin to a beautiful calm sky; ultramarine dominates, and sets the local tone; thirty large compartments, indicated by simple borders, contain the life of the Virgin and that of her divine Son, in extensive detail: one might describe them as illustrations, in miniature, to a gigantic missal. The characters, in one of those naive anachronisms so dear to history, are dressed in the fashions of Giotto’s day.

Below these compositions, of a charming sweetness and exhibiting the purest religious feeling, a painted plinth shows the seven deadly sins, and other allegorical figures, symbolised in an ingenious way, in a very accomplished style; a paradise and a hell, subjects which preoccupied many artists of this era, complete this wonderful group. There are odd touching details in these paintings; children come out of their tiny coffins so as to ascend to heaven with joyful alacrity, and race off to play on the flowery lawns of the celestial garden; others extend their hands to their half-resurrected mothers. We might also note that all the devils and vices are obese, while the angels and virtues are long and slender. The painter thus marks the preponderance of matter in some, and the spirit in others.

I must record here a remark of a picturesque and physiological nature. The female Paduan type differs greatly from that of the Venetian, despite the proximity of the two cities; the women’s beauty is more severe and more classical: dense brown hair, marked eyebrows, dark eyes and a serious gaze, a pale olive complexion, and a slightly matt oval face, recall the main features of the Lombard race; the black bautas which frame these beautiful girls’ faces, gives them, as they file in silence along the deserted arcades, a proud and fierce air, which contrasts with the vague smile and easy grace of the Venetians.

View, in Piazza Salone, the Palace of Justice (Palazzo della Ragione), a vast building in Moorish style, with galleries, columns, and denticulated battlements, which contains the largest room, perhaps, in the world, and recalls the architecture of the Doge’s Palace in Venice; and in the Scuola del Santo, the glorious frescoes by Titian, the only ones we know of produced by that great artist; and you will avoid major regret on leaving Padua.

They still display there, the instruments of torture, easels, straps, pliers, pincers, boots, toothed wheels, saws, and cleavers, which Ezzelino, most famous among tyrants, used on his victims and beside whom Angelo is nothing but an angel of kindness. I bore a letter to the enthusiast who preserves this bizarre collection, fit for an executioner's museum. We could not locate him, to my great regret, and we left the same evening for Rovigo, tearing ourselves away with difficulty from that sweet Lombardo-Venetian kingdom, which lacks nothing, except, alas, liberty!

Part XXVIII: Ferrara and Bologna

A horse-drawn omnibus takes a few hours to travel from Padua to Rovigo, at which we arrived in the evening. While awaiting our supper, we wandered through the streets of the city, lit by silvery moonlight which made it possible to discern the silhouettes of monuments; low arcades like those of the old Place Royale in Paris run along the sides of the streets, and with their alternating light and shadow form long cloisters which, that evening, recalled the effect of the stage-set of Act III of Meyerbeer’s Robert Le Diable with its Ballet of the Nuns.

Rare pedestrians passed by silently like shadows; a few plaintive dogs barked at the moon, and the city already seemed asleep, the windows everywhere unilluminated, with the exception of a few brightly-lit cafes, where the regulars, looking bored and sleepy, consumed an iced drink, a half-cup, or a glass of water in small spoonfuls, sipping slowly, wisely, and methodically, raising their heads now and then to read an insignificant article in the censored Diario, like people who have many hours to endure, and await the time when they can depart for bed.

In the morning, at dawn, we were obliged to climb into a sort of guimbarde (two-wheeled carriage) holding the middle ground between a French patache and a Valencian tartane. Delicate travellers may set here an elegy, filled with pathos, on the discomfort offered by these kinds of vehicles; but the Spanish galera (covered cart) and postal wagon, driven on the most abominable tracks in the world, had rendered me extremely philosophical as regards such small inconveniences. Besides, those who wish for all their home comforts only need to remain there. An Erler coupé on the macadam of the Champs-Élysées gives an infinitely softer ride, and it is indisputable that we dine better at the Freres-Provençaux (in the Palais Royale) than in some hotel on the main road.

The journey from Rovigo to Ferrara is not very picturesque: flat land, cultivated fields, Northern trees; one could believe oneself in a department of France.

We crossed the River Po, its waters yellowish; its low, bare banks vaguely recalling those of the Guadalquivir below Seville. The fiery Eridanus, deprived of its tribute of melting snow, looked quite calm and good-natured for the moment.

The River Po separates Romagna from the Lombardo-Venetian states, and Customs awaits you on exit from the ferry. One tends to complain a great deal about the Italian Customs and the endless vexations associated with them. I confess they have always leafed through our meagre luggage with less meticulousness, certainly, than would have been shown by the French Customs on such occasions; it is true that we always rendered up the keys with graceful insouciance and displayed our passport, whenever we were requested to do so, with the celerity and politeness of the monkey Pacolet (See Gérard de Nerval’s tale, ‘La Main Enchantée’)

The Romagnola Customs, after having carelessly rumpled our shirts and socks, and finding that we carried no literature other than a Guide Richard (travel guide), a superlatively benign and scarcely subversive book, closed our trunk with magnanimity, and permitted us in the most lenient manner possible, to continue our journey.

In the carriage we had the company of two rather elderly priests, large, fat, short, with oily yellow complexions, and shaved beards whose bluish tones rose to the cheekbones, and who unknowingly wore the costume of Basilio in Beaumarchais’ The Marriage of Figaro, as exaggerated a caricature as those the theatre-directors choose to present on stage. Among us ecclesiastical dress has almost disappeared. Priests in France secularise themselves as much as is possible; very few, since the revolutions of July 1830 and February 1848, wear a cassock, openly, in the street. A wide-brimmed hat, clothes of a black antique cut, long frock coats, a cape of a sombre colour, produce a mixed appearance, somewhere between religious and modern dress, like to that of a Quaker, or a serious fellow carefully attired. They are priests only by stealth, and it is only in church that they don priestly regalia. In Italy, on the contrary, they sit back and relax in character, take the upper hand, and are everywhere at home, flourishing their handkerchiefs amply, blowing their noses and coughing loudly, as people to whom all respect is due, and who must not be interfered with.

They had taken the best seats in the carriage, which we had yielded to them with the deference owed to their age and condition, and spread themselves generously, even though they had usurped them without the slightest word of apology and the slightest concern for our pleasure and comfort. It is true that we were in the Papal Sates, where the priest reigns as an absolute master, possessing the keys to both heaven and earth, to the other world and this one, and able to damn you, hang you, and destroy you, body and soul. The awareness of this enormous power, the greatest ever wielded, grants the priests of that country a security, poise, and masterful and sovereign ease of which we have no idea in the countries of the North.

Our two priests, for that was probably their rank in the ecclesiastical hierarchy, exchanged rare and mysterious words with each other with that reserve and prudence which a priest never abandons before secularists; or they slept; or muttered the Latin of their breviary from volumes with brown covers, the red-lettered sections separated by bookmarks; I cannot believe that, throughout the whole journey, they chose even once to look at the landscape beyond the carriage; did they know and fear the distractions of the outside world, the charm of eternal Nature behind which hides the great god Pan of antiquity, whom the Catholics of the Middle Ages persisted in viewing as the Devil?

These companions, certainly respectable but whose dull chill froze us, we parted from at Ferrara. Those pale faces, those black clothes made our vehicle resemble something like a funeral carriage, and we watched them leave with pleasure.

Ferrara rises alone, amidst a level tract of countryside which is prosperous rather than picturesque. When ones enter via the main street which leads to the square, the appearance of the city is imposing and monumental. A palace with a grand staircase occupies a corner of its vast terrain; it must serve as courthouse or town house, because people of all classes enter and exit its wide doors.

As we wandered the street, satisfying our curiosity at the expense of our appetite, and stealing from the time allotted to our lunch forty minutes in which to feast our eyes and fulfil our duties as a traveller, a strange apparition suddenly appeared before us, as unexpected as a phantom at midday ever is: it was a kind of spectre, masked in black, its head engulfed in a black hood, the body draped in a cloak, or rather a purple domino bordered with red, and with a red cross on the shoulder, a yellow copper crucifix hanging from its neck, and a red belt round its waist; this figure was silently shaking a small wooden box, a portable chest, which emitted the clinking of coins.

This scarecrow, whose eyes alone, seen shining through the holes in the mask, were alive, rattled its treasury in front of us a few times, into which, terrified, we let a handful of loose change flow, without knowing for what charity this lugubrious beggar was collecting. He continued on his way without saying a word, accompanied by a sinister, funereal, and metallic tinkle of coins, holding out his box into which everyone hastened to bury a handful of pennies.

We asked what Order this ghost, more frightening than the monks and ascetics of Francisco de Zurbarán’s paintings, belonged to, who thus brought the terror of nocturnal visions to the pure light of day and realised in the street a nightmare of troubled sleep. We were told that he was a penitent of the Confraternity of Death, begging in order to fund masses and biers for those poor devils who were going to be executed by firing squad that day; brigands, or republicans, of that we learnt no more. Such penitents take upon themselves the sad and charitable mission of accompanying the tortured and condemned to their death, supporting them in their supreme anguish, removing their mutilated bodies from the scaffold, laying them in their coffins, and providing them with Christian burial. They are citizens who dedicate themselves, out of feelings of pity, to these painful functions and thus bring a tender element, though veiled and masked, to the implacable and cold immolations of justice. These spectres defend the victims, to some extent, from sight of the executioner. It is a timid protest on behalf of Humanity. Often these charitable attendants on the scaffold feel the pain of the condemned, and are more troubled than the victims themselves.

This is not the place to discuss the legitimacy of the death penalty; voices which gain more attention than mine have developed, with great eloquence, the logical reasons for and against. But, given that this dreadful legal tragedy is to be upheld, it seems to me that the staging (please forgive the word) must be as fearsome as possible. It is not a matter of skilfully preventing the culprit comprehending their immediate fate, an operation which in no way improves the business, but a matter of setting a terrible example which will act on the imagination and deter crime. Whatever dismal spectacle can increase the effect of this bloody drama and impress it on the depths of the spectators’ memories in formidable form, must, in my opinion, be implemented. It is necessary that physical terror combine with moral terror.

Imagine for a moment these purple-robed Claude Frollos (see Victor Hugo’s ‘Notre Dame de Paris’) holding burning candles in their hands, walking in double line beside the ashen-faced condemned! ‘That’s out of an Ann Radcliffe novel, it’s pure melodrama’, serious thinkers will say: possibly so. But then what is the point of cutting off heads, if it terrifies no one? One must avoid hiding from realities, if one wishes them to produce the desired effect; a torment that terrifies is less hideous than a ‘civilised’ torment deprived, by mechanics and philanthropy, of its dreadful poetry. But enough of this unpleasant subject; let us return to less sombre matters.

Italy has largely retained the methods of Doctor Sangrado (see Alain-René Lesage’s novel ‘Gil Blas’), and the ilk, whose system, developed in kitchen-Latin in Molière’s play The Imaginary Illness, has not yet been done away with; this I say without disrespect to true medical talent. There are in the Peninsula quite numerous examples of Moliere’s doctors, Purgon, Diafoirus, Macroton, and Desfonandrès, and many another in the style of Molière; one is bled white for the slightest indisposition; these operations are carried out by barbers; one sees, on their shop signs, paintings of the most delightful surgical fantasies: here, one views a bare arm whose opened vein launches a purple jet as ample as those spurts of harmless beer pouring into the glasses of hussars or young girls on village inn-signs; there, chubby Cupids, crossing a deep blue sky, bear a dish which will receive the blood of a young woman in an interesting state, who is smiled upon tenderly by a husband dressed in the costume of the days of the Directory. In these bloodthirsty subjects, the verve of the sign-painters called to create these works does not shy away from a violence of tone and a use of contrast amazing to the colourist.

It was market-day, which produced a degree of excitement in a city which is usually so dreary. We saw nothing characteristic in terms of costume; uniformity pervades everything. The country folk around Ferrara were quite similar to ours, except for the southern brilliance of their black eyes, and a certain pride in their appearance which reminded us that we were in the land of the classics; autumn produce, grapes, pumpkins, peppers, tomatoes, along with coarse pottery, and rustic household utensils, were piled high in the square, where groups of customers and buyers were stationed, along with a few ox-carts much less primitive than those of Spain; a few donkeys loaded with packs of wood waited with patient melancholy for their masters to conclude their business and return; oxen knelt while ruminating peacefully; donkeys tugged, with the tips of their grey lips, at blades of grass springing from cracks in the pavement.

One detail peculiar to Italy was the presence of open-air money changers. Their stalls are of the simplest nature consisting of a stool and a small table where piles of scudi, baiocchi (one hundredth of a scudo), and other coins are stored. The money-changer, crouched like a dragon, looks at his little undefended heap of treasure with a worried and yellow eye, filled as he is with the incessant fear of thieves.

Let me note one more very Italian detail: a sonnet in praise of a doctor who had cured his patient of illness had been posted by the thankful convalescent on one of the most visible walls in the square. This sonnet, very flowery and full of mythological references, explained that the Fates had wished to cut the thread of the patient’s days, but that the doctor, accompanied by Aesculapius, the god of medicine, and Hygeia, the goddess of health, had descended into Hades to deflect Atropos’ scissors, and replenish Clotho’s spindle, Lachesis having since then spun a length of thread. We quite liked this ancient and naive way of expressing gratitude.

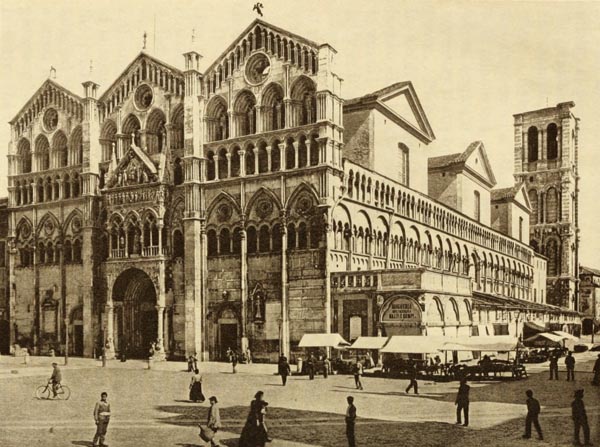

The cathedral, whose facade overlooks the square, is in that Italian Gothic style so inferior to our Northern Gothic. The porch offers curious details. Its pillars, instead of resting on bases like ordinary columns, are borne by chimeras, in the style of those beside the portal of the Basilica of Santa Justina in Padua, which the columns half-crush, and who take revenge for their pain by tearing captive Ninevite-style lions in their paws. These caryatid monsters seemed to writhe horribly beneath the enormous pressure, their eyes full of pain.

Ferrara - The cathedral

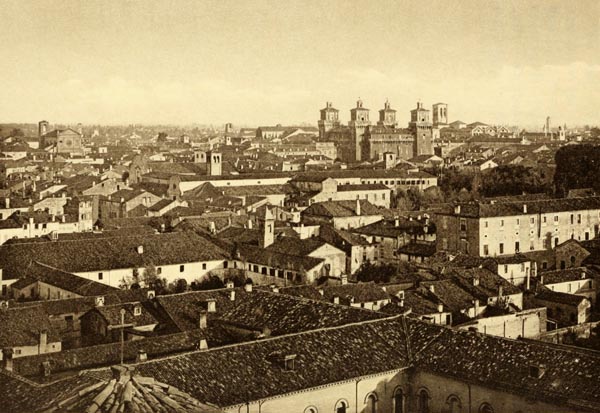

The castle of the former Dukes of Ferrara (Castello Estense), which can be found a little further on, has a fine feudal appearance. It is a vast cluster of towers, linked by high walls and crowned with lookout-points forming a cornice, emerging from a large moat full of water over which one passes by a well-defended bridge.

Ferrara - View of Castello Estense from the Bell-Tower of Saint Benedict

Regarding what I have just said, let none imagine a burg like those which bristle on cliffs along the Rhine. A stage-set in the Théâtre Italien, that of Federico Ricci’s Corrado d’Altamura, or Rossini’s Tancredi or some other chivalresque opera, would give a fair idea of the castle. The Gothic in Italy has by no means the same physiognomy as at home. No greenish stones, mossy sculptures, or mantles of ivy falling from old broken balconies; no trace of the rust of time, inseparable for us from a building of the Middle Ages: it is a Gothic which, despite its date, seems brand new; a white and pink Gothic, more pretty than serious, somewhat reminiscent, to be honest, of those feudal, troubadour mantelpiece clocks of the Restoration period. The castle of the Dukes of Ferrara, everywhere built from bricks or stones reddened by the sun, shows the vermilion hue of youth which detracts from its attempt at an imposing effect. It looks too much like a setting from melodrama.

In this castle lived the famous Lucrezia Borgia, whom Victor Hugo portrays as a monster, and Ariosto depicts as a model of chastity, grace and virtue; the blonde Lucrezia, who wrote letters breathing the purest love, and of whom Byron possessed a few strands of hair, fine as silk and gleaming like gold. This is where plays by Tasso, Ariosto and Giovanni Guarini were played; where those glittering orgies took place, full of poison and assassination, which characterise that period of learned, artistic Italy, refined and yet villainous.

It is customary to visit, piously, the dungeon where Tasso, mad with love and pain, passed so many years, according to the dubious poetic legend springing from his misfortunes. We lacked the time, and regretted it little. This dungeon, of which I have before me a very accurate drawing, has only its four walls, capped by a low vault. In the background is a grilled window with thick bars and an iron door with large bolts. It is most improbable that, in this dark hole covered with cobwebs, Tasso was able to work and rework his epic, compose his sonnets, and occupy himself with minor details of his clothing, such as the quality of the velvet used to produce his hat and the silk to make his breeches, and of his cuisine, such as the kind of sugar with which he wanted to sprinkle his salad, that which he was given not being fine enough for his liking; nor did we see Ariosto’s dwelling, another station on the obligatory pilgrimage. Besides my placing little faith in such inauthentic traditions, such characterless relics, I prefer to seek Ariosto in his Orlando Furioso, Tasso in his Gerusalemme Liberata or in Goethe’s fine dramatic work (Torquato Tasso).

Activity in Ferrara is concentrated on the Plaza Nueva, in front of the church and around the castle. Life has not yet abandoned the heart of the city; but as one moves further away, the pulse weakens, paralysis begins, death approaches; silence, solitude and grass invade the streets; one feels that one is wandering in a Thebaid populated by the shades of the past and from which the living flow away in a failing stream. Nothing is sadder than to see the corpse of a city slowly fall to dust beneath the sun and rain. At least we bury human corpses.

After a few hastily-swallowed mouthfuls, we returned to our berline, and headed for Bologna at a moderate pace that was further reduced by the ox-carts, piled high with cut reeds, obstructing the road: they looked like haystacks ambling along, a green wall receding before us, since the oxen completely disappeared beneath their mass. We had to wait until the path widened before overtaking them.

We halted at a vast inn with an arcade open to every breeze, in a place whose name I cannot exactly remember, it being a detail of little significance, but which, in all probability must have been Cento, and we ate a modest repast there, since we were due to arrive in Bologna in the early evening.

Of the route I can scarcely recall anything other than a vast horizon of crops and trees lacking the slightest interest. Perhaps the shadows of evening, which brought on a state of drowsiness and left me less light than the spark of my cigar, hid some beautiful scene from view; but that is unlikely, given the nature of that countryside.

Bologna is a city with arcaded streets, like most of the towns in that part of Italy. These porticos provide convenient shelter from the rain and sun; but they transform the streets into long cloisters, absorb the light, and make the cities look chilly and monastic. One may judge from the Rue de Rivoli, in Paris, the success of this system.

We descended at an inn, where by means of a most moving pantomime we obtained our supper, which included, for our benefit, salami (a cured meat, usually pork, sausage), mortadella (a large sausage of finely ground pork), bondiola (shoulder of pork), and Bologna sausage (its contents similar to bondiola), required to provide local colour.

After supper we went for a walk; a droll character, pale and greasy-faced, with a moustache brushing his teeth, decorations in cheap alloy, and a frock coat with loop fastenings, reminiscent of the type worn by Cavalcanti senior in Dumas’ novel (The Count of Monte Cristo), began to dog our footsteps and followed our every change of pace and direction whenever he detected that same. Bored with this manoeuvre, we told him to walk elsewhere, and did so in a rather brutal way, taking him for a police informer; but he refused to quit us, his claim, and his right, being that of acting as a guide to travellers. Moreover, in that capacity, we belonged to him, and he found it indelicate of us to seek to avoid the royalties he levied on such as ourselves. We were thieves who defrauded him of his revenue, who took the very bread from his mouth, and the coins from his pocket. He had counted on us for the enjoyment of a bottle of Picolit or Aleatico, to buy a scarf for his wife and a ring for his mistress. We were infamous scoundrels for disturbing his plans of ease and domestic happiness. We were setting a bad example to all future travellers, and he was resolved not to back down one iota. He wished to lead us to the diligence, whose lantern shone two steps in front of us, and to Via Galleria where we were. I had never seen a more obstinate and more stupidly opiniated fool. After the most energetic cursing, and cries of: ‘To the Devil with you!’ fiercely accented on our part, he recommenced his proposal as if we had said not a word, feigning that we would infallibly lose our way, and that he would not suffer it for anything in the world.

Realising that extreme action was required, I took a few steps back, and invoking, mentally, the memory of Hubert Lecour, our teacher of savate (street fighting) and how to wield a stick, I began to execute a beautiful arabesque with my cane that would have made Corporal Trimm (see Lawrence Sterne’s ‘Tristram Shandy’) envious of the complexities of its arcs and knots, and which, in that art, is termed the rose couverte.

When the scoundrel saw the rod flash by like lightning, and heard it hiss like a snake, three inches from his nose and ears, he leaned back muttering, and saying that it was not natural for proper travellers to refuse the services of an educated and considerate guide who had led the English about Bologna to their great satisfaction.

Remorse for not having broken his pate returns sometimes, on sleepless nights; but perhaps I would have regretted the good deed, and paid for harming that pumpkin-head. I ask forgiveness of all those travellers whom he may subsequently have annoyed, for not having knocked him senseless. It is an error I will repair, if I ever pass through Bologna again.

We had a letter of recommendation for Giacomo Rossini who, unfortunately, was absent and was not due to return for a few days. It is embarrassing not to have viewed the living face or heard the voice of a great contemporary genius. One should strive as much as is possible, to witness the external forms of beautiful spirits, and when we hear Semiramide, The Barber of Seville, or William Tell, it is painful to me to be able to add no more to my idea of Rossini than the engraving of him by Ary Scheffer, and the statue in marble, with under-straps, which clutters the box-office in the Opéra vestibule (there is a small bronze copy by Antoine Etex in the Louvre).

A puerile remark perhaps, but one that I have already made in my travels, is that one can judge the state of advancement of a civilisation by how small the number of barbers is in a given town or city. In Paris, there are very few; in London, there are none not at all. That home of razors shaves its own beard. Without wanting to accuse Romagna of barbarism, it is fair to say that nowhere have I seen a greater number of barbers than in Bologna; one street alone contained more than twenty in a very limited area, and, what is most amusing, is that the Bolognese city dwellers are frequently bearded.

It is the people of the countryside who form the barber-shops’ clientele, the barbers having a very light hand, as our skin can bear witness, without however possessing the dexterity of the Spaniards, the premier barbers in the world since the appearance of Figaro.

Leaving the barber’s shop, we chose and followed a street at random which led us, suddenly, to the square (Piazza di Porta Ravegnana) in which the Torre degli Asinelli and the Torre della Garisenda, have been tottering for many centuries already, without falling; towers which had the honor of providing Dante with an image. The great poet compares Antaeus bending towards the earth to the Garisenda (Inferno Canto XXXI), which proves that its inclination began before the fourteenth century.

These towers, viewed by moonlight, seem the most fantastic in the world; their strange deviation, belying all the laws of statics and perspective, makes one dizzy, and makes all the neighbouring buildings appear out of true. The Torre degli Asinelli is three hundred feet high; its inclination is three and a half feet. This extreme elevation makes it appear spindly, and can only be compared to one of those huge factory chimneys in Manchester or Birmingham. It rises from a crenelated base and has two further crenelated stages, the second less pronounced; an iron chain runs from the pinnacle which surmounts it to the base of the building.

La Garisenda, which is only half the height of the Torre degli Asinelli, is dreadfully out of true and from certain directions seems almost to touch its neighbour on the right. Although it has been standing for more than six hundred years, I preferred not to linger on the side towards which it inclines. It seemed to me that the instant of its ruin had arrived, and I would be crushed beneath the rubble; a moment of childish fear which it is hard for one to escape.

A bizarre and grotesque idea, which illustrates perfectly the extravagant effect of these towers, came to me while looking at them, which I shared with my travelling companion: they are two monuments which drank themselves into intoxication outside the barrier, and have returned home drunk, leaning against each other.

If the glow of the moon allowed us to see the towers of Asinelli and Garisenda, it was insufficient for us to examine the paintings in the museum, which according to the guide-book, include works by the three Carracci (Annibale, Agostino and Ludovico), Domenichino (Domenico Zampieri), Francesco Albani, and other great masters of the Bolognese school, and we returned, much to our great regret, to lie down on one of those enormous Italian beds, which would easily hold Hop-o’-My-Thumb’s six brothers, and the seven daughters of the Ogre, along with their fathers and mothers; you can rest there, pointed in all directions, up, down, or diagonally, without ever falling into the street below.

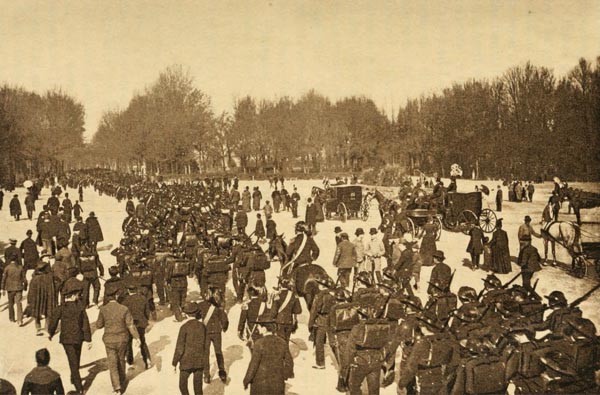

At four o’clock in the morning we rose, still half-asleep, to mount the Florence stagecoach, and we noticed a gathering of troops. They were preparing to execute some twenty people for political reasons. We left Bologna with the painful impression we had already experienced in Verona, and Ferrara, and which was awaiting us in Rome: but the thought of crossing the Apennines on a beautiful September day soon dispelled the gloomy feeling!

Part XXIX: Florence

The Armida (see Tasso’s ‘Gerusalemme Liberata’) of the Adriatic having detained us among her enchanted canals beyond the end of our intended stay, we were finally obliged to leave, despite the non-appearance of Ubalde the knight to make us blush at our tardiness by revealing the magical shield of diamond to our eyes; after our brief halts in Padua and Bologna, whose gloominess seemed more so having left Canaletto’s enchanted city behind, we headed as directly as possible towards Florence, the Athens of Italy.

We very much regretted not being able to visit, in passing, the Sanctuary of the Madonna of San Luca, near Bologna, a singular building, located on a hill, Monte della Guardia, and to which a corridor leads with, on the one side, a wall that is well over two miles long, and, on the other, six hundred and sixty-six arches framing a marvellous landscape. This immense portico, raised by Bolognese piety, climbs the side of the mountain in over five hundred steps, and conducts travellers and the devout, from the gates of the city to the sanctuary; but, in travelling as in everything else, one has to know how to make sacrifices; if one wants to arrive, one has to choose a course and follow it, while casting a look of regret at what escapes one. To wish to see everything results in seeing nothing; it is enough merely to see something.

The road from Bologna to Florence traverse the Apennines, the backbone of Italy; a backbone, indeed, of which each fleshless mound forms a vertebra. Even on the most seasoned of travellers, those well-accustomed to disappointment, there are certain names which exert a magical influence, that of the Apennines being one; it is a name found in Horace and the ancient authors, which one’s study of the classics includes among our first impressions, and it is difficult not to possess a ready-made idea of the Apennines, which viewing the reality singularly contradicts and amends.

The Apennine chain is made up of a series of arid, crumbling, excoriated hillocks; rough mounds, of scabby hills that look like piles of gravel and rubble; none of those gigantic cliffs, arduous peaks clothed with pine-trees, cloudy summits, silvery with snow, glaciers with a thousand glittering crystals, waterfalls where the rainbow reveals its bow, blue lakes like pieces of turquoise where chamois come to drink, or eagles soaring in great arcs against the light; nothing but Nature, poor, dull, and sterile, and seeming even more petty after the Olympian majesties of the Swiss Alps and the romantic horrors of the Gondo gorge of so picturesque and fearful a grandeur.

Certainly, our mania for comparisons is a quirk of the mind, and it is unfair to ask one place to be like another; but I could not help thinking, from the height of my imperial bench-seat atop the coach, which I had imprudently exchanged an interior corner for, so as to be able to examine the country more at ease, of the beautiful Spanish sierras, which no one speaks of and whose neglected beauties are far superior to the Italian slopes, which are vaunted perhaps to excess; I recalled the journey from Granada to Vélez-Málaga, through the mountains, by a forgotten track over which perhaps not two travellers a year pass, yet which exceeds all one could possibly imagine as regards accidents of form, light and colour.

I thought also about my excursion to Kabylia (in Algeria), its mountains gilded by the African sun, its valleys full of oleanders, mimosas, arbutus, and mastic trees, its streams inhabited by little turtles, its Kabyle villages surrounded by fences of cacti, and its horizon of varied serrations dominated ever by the imposing silhouette of the Djurdjura range, after which the Apennines seemed truly mediocre, despite their Classical reputation.

I am not given to repeating that famous paradox uttered in Marseille: ‘Freezing in Africa, burning in Russia.’ However, I must admit that we were shivering from the cold in our aerial position, despite layers of overcoats and pea-coats to rouse the envy of Joseph Méry, the chilly poet. I had never in Paris, during the most rigorous of winters, clad myself, at any one time, in such a mass of clothing, and yet it was only mid-September, a season we are accustomed to think of as warm and charming under the gentle Tuscan sky; it is true that the elevation of the land cools the air, and that the cold of hot countries feels particularly unpleasant due to the sudden contrast.

It is not with the aim of erecting a monument to our frozen fingers, and chattering teeth, that I record the remark. Whether we were hot or cold on the top of a stagecoach was a matter of small account to the universe; but the observation might prevent some naive and over-confident Parisian quitting Guiseppe Tortoni’s Café de Paris on the Boulevard Italiens for Florence, in August, in cotton trousers and a striped cotton hunting-jacket, and encourage him to include in his luggage a tartan plaid, a pilot’s overcoat, and a muffler, thus preventing various head and chest colds. The description of our suffering is therefore not personal; it is wholly philanthropic.

The violence of the wind is so great on those bare, peeled slopes, which alternately receive the cool breath of the Mediterranean breezes and those of the Adriatic, that the Grand Duke of Tuscany had a stone wall built, at the highest point of the road, to protect travellers from the icy gusts which might otherwise pierce and overcome them. Those who have felt the mistral at work, at the foot of the Castle of the Popes in Avignon, will understand the usefulness of such a wall. An inscription in the style of a hospice notes this kind attention bestowed by Leopold II, an attention for which we thank him from the bottom of our hearts.

At that point, one leaves Romagna and enters Tuscany; another Customs visit, an inconvenience of such States as these divided into small principalities. One spends one’s life opening and closing one’s trunk, a monotonous occupation, which ends up infuriating the most phlegmatic of travellers. Fortunately, we had developed a philosophical system prior to this, in response to the Romagnola Customs officers. We threw our key to whoever wished to take it, or left it in the lock, and went off to contemplate the landscape in peace, a facility that the implacable diligence does not always allow. From this point of view, it is perhaps to be regretted that there are not more Customs stations.

Although the road never achieves the abrupt escarpments, and impossible roller-coaster rides, of the passes of Sierra de las Salinas and the Col de la Descarga, in the Pyrenees, the slopes are often steep enough to require the help of oxen. We always viewed, with pleasure, the arrival of the ox-team, heads bowed beneath the yoke, with their damp muzzles, large peaceful eyes, and powerfully outstretched legs; firstly, they are picturesque in themselves and, secondly, they are always accompanied by a wild and rustic herdsman, often of great stature, with straggling hair, a pointed hat, a brown jacket, and a goad borne aloft like an ancient sceptre; however, there was a further reason for our delight.

I once asked Louis Cabat, the grand-master of our wonderful school of young landscape artists, how, during his excursions, he determined on the choice of the site that he wanted to paint. ‘I wander at random’, he replied,’ till I hear the frogs croaking. Where there are frogs, the scene is always attractive; frogs mean a pond, fresh grass, green reeds, osiers and willows.’

Our frogs were the oxen. Their appearance means a harsh summit, a high plateau, from which an immense view is suddenly revealed; an azure panorama of plains, mountains, valleys; a horizon strewn with towns and villas, shimmering in shadow and light. Our oxen no more failed us than the frogs did Cabat.

As the slopes of the Apennines begin to tilt towards Florence, the landscape acquires a greater beauty. The herpetic, warty hillsides disappear or are clothed with vegetation.

Villas begin to appear beside the road, cypresses elevate their black spires, Italian pines display their rounded green parasols; a warmer gentler breeze allows one to half-open one’s coat; the olive trees face the air without their sad and gloomy foliage trembling; one senses the stir of pedestrians, horses, carriages, the approach of a great living city, a rare thing in Italy, that ossuary of dead ones.

Night had fallen when we arrived at the San Gallo gate. Our rather meagre lunch, though washed down with passable wine contained in large glass flasks braided with white esparto grass, swallowed on the border of Tuscany, made us strongly desire, despite our usual sobriety, the sign of the Black Eagle, Red Lion, Golden Sun, or Maltese Cross, so as to attend, as Rabelais says, ‘à cette réparation de dessous le nez: to that reparation of what’s below the nose’ which so worried the good Panurge (see ‘Gargantua and Pantagruel’ Book II: ‘Comment Panurge gagnait les pardons’). Our eyes had consumed the meal for good or ill; but our stomachs had received only one, and then, again, a very meagre one!

Florence is corseted by a girdle of fortifications, and makes difficulties when one comes knocking on her door in the evening. We had to wait a full hour, before the gate, for I know not what meticulous police formalities to conclude, till, at last, the wooden barrier, a kind of peacetime portcullis which blocked the archway, was raised, and the carriage was able to traverse the cyclopean paving stones of Florence. I say cyclopean because, like walls which bear that name, the stones were of unequal shape, arranged at angles, like Chinese-puzzle pieces.

For a city of feasting and pleasure, whose name is perfumed like a bouquet, Florence offered us a strange reception, which might have made more superstitious people recoil at its ill-omened appearance.

In the first street that the coach navigated, we met with an apparition more fearful than that of the cart of the ‘Parliament of Death’ encountered by the resourceful knight of La Mancha near El Toboso (see Cervantes’ ‘Don Quixote’ Part II Chapter XI); only, here, it was not a question of the enactment of a piece of auto-sacramental theatre, but of a dreadful reality.

Two black lines of masked spectres, carrying resinous torches, from which streams of reddish light escaped amidst thick smoke, were walking, or rather running, before and behind a catafalque carried aloft, which could be vaguely distinguished through the brown fog of that funereal light; one of them was ringing a bell, and all were chanting a prayer for the dead beneath their breath, through bocca chiusa (closed mouths) behind their masks, in a stifled panting rhythm. Sometimes another black spectre emerged from a house, and hastily joined the dark herd, which quickly vanished at the crossroads. They were a brotherhood of black penitents who, as customary, escorted the coffin.

This dismal vision reminded of me of a poem by Auguste Brizeux, the poet of Marie and Les Bretons, a Celt naturalised in Florence, which proves to me that he had met like me with an unexpected spectacle of this kind and gained an impression similar to my own. Let me transcribe it here as a complement to my nocturnal sketch:

With blows, the Bargello’s bell resounds.

My pale neighbour quits the café.

Now ever-louder the tocsin sounds.

Another departs... ‘What is happening, pray?

Dear sir, we are lodged at the very same inn.

Why are these people masked, shrouded, in black?’

‘To bear candles, and carry the dead within.’

‘Their hands are so white! I’m taken aback.’

‘Dear traveller, none can know whom they see;

These men are shrouded, and masked, to do good:

A labourer, or the Grand Duke it may be.

Everyone is a Christian, under the hood!’

(Auguste Brizeux: ‘Les Frères de la Miséricorde’)

The people of the South, although brooding about death much less than those of the north, since they are constantly distracted by the pleasure of the climate, the spectacle of nature’s beauty, and the effects of hotter blood and hotter and livelier emotions, love these processions of dominoed ghosts; for they are seen throughout Italy. The Italians feel the need to give everything physical form, and to stir the imagination through dramatic spectacle. Not long since, the dead were borne along their faces uncovered; the appearance of those livid, immobile corpses under the cosmetics applied to hide a grimace frozen in agony and the initial process of decomposition, added a further sinister and fantastic effect to those funerals. Now there are only the monks who appear in this manner with robes to shroud them.

A strange thing! In England, the country of Edward Young’s Night Thoughts, the country where Shakespeare’s gravedigger tosses Yorick’s skull in the air like a ball; the native land of spleen and suicide; the dead are removed surreptitiously, almost in secret, in a sort of black upholstered carriage at an hour when the streets are deserted, and by circuitous paths; during four or five trips to London, I failed to encounter a single funeral. We fall from life to non-being without transition, and our useless remains are packaged up and hidden away with the greatest possible alacrity. Catholics present their staging of death in a superior manner, and a firm belief in the immortality of the soul diminishes their dread of funeral ceremonies.

We were directed to the hotel New York, on the lungarno, near the Carraia bridge, as providing a sufficiently comfortable stay. In fact, we found it to be a large house, run in a more or less English style, where one ate in a civilised fashion, something we had not done for a while. Travellers from other nations are not grateful enough to the English, those great educators of innkeepers, those brave islanders who transport their homeland with them everywhere, in compartmentalised trunks, and who, living in the wealthiest parts of London, such as the City or the West End, have, by deploying their powerful guineas, exclamations of surprise, and opiniated judgements, established rump-steak, chops, salmon, boiled vegetables, Indian curries, and a small pharmacy of spicy condiments, such as Guyanese red peppers, West Indian pimentos, Harvey’s sauce, anchovy sauce, and candied palm buds in vinegar, throughout the globe. Thanks to them, there is no desert island in the most unknown archipelago of Oceania where one cannot find, at any time of day or night, tea, sandwiches, and brandy, as at any tavern in Greenwich.

The meal over, we wandered the city for a while without a guide, according to our usual custom, trusting ourselves to an instinct as regards local topography which prevents our getting lost, even in places only known from a map or a quick glance; we traversed the lungarno as far as Ponte Santa Trinita; went down a street, and found ourselves in front of Caffè Doni, Florence’s equivalent to Tortoni’s in Paris; the carriages stop there when returning from the Cascine promenade, the city’s Champs-Élysées, to which folk take iced drinks in their vehicles.

Two tall girls, a little dark of complexion, but quite beautiful, dressed with a sort of elegance, and wearing those Italian straw hats, with fine braid, which one sees so frequently in Paris, and which are so expensive there, rushed towards us with a happy boldness, their hands full of flowers, and soon had made flowerbeds of our vests; every buttonhole of our clothing found itself starred, in the blink of an eye and without our being able to defend ourselves from their assault, with a carnation or a rose. Never was a page-boy at a wedding more adorned. The flower-girls, having spotted a novice, as they say in college, had seized upon their prey and greeted our arrival in their own way. Florence is the city of flowers; there is an enormous market for them; on outings, the seats of the carriages are cluttered with bouquets, flowers rain on them, the houses are full of flowers, and one climbs the stairways between flowery hedges. They say that in spring the countryside is enamelled with a thousand colours like a Persian carpet. That sight I can only mention as hearsay, since it was autumn.

While in the hands of these girls, we found ourselves addressed by three or four friendly voices as if we had been on the Boulevard des Italians, in Paris.