Théophile Gautier

Travels in Italy (Voyage en Italie, 1850)

Parts VI to X - Milan and Venice

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Part VI: Da Vinci’s The Last Supper – Brescia – Verona.

- Part VII: Venice.

- Part VIII: St Mark’s Basilica – The Exterior.

- Part IX: St Mark’s Basilica – The Interior.

- Part X: The Doge’s Palace.

Part VI: Da Vinci’s The Last Supper – Brescia – Verona

The daytime-theatre, which also serves as a circus, since horses and equestrian performances play a large part in its offering, has no ceiling: the vault of the sky takes its place. It consists of a parterre, which literally deserves its name, and open galleries in the form of boxes, but without partitions or rear wall. It was about half-past five and the play indeed began sub jove, crudo (under a bright sky), but soon dusk fell, then night. A candle was first lit, discreetly, to light the actor on stage, while the rest was plunged into darkness, almost like those performances by dancers from Algiers who, afraid to rely on the lighting of the room where they display their graces, retain an African to stand close by holding a candle, which he raises or lowers illuminating the eyes, waist, or feet, according to the progress of the dance. Then a timid light came to join the first; finally, a piece of planking rose, a few lamps clinging to it, and the daytime theatre was transformed into a poorly-lit night-time theatre. Of course, to act as gas-lights the room had only the stars.

The acting seemed quite good. Unfortunately, the Adrienne de Cardoville of The Wandering Jew was dour, thin, and dark, and made us regret the blonde and vivacious Alphonsine (Jeanne Benoit) of the Délassements-Comiques in Paris. The two young girls, though more pleasant, did not sufficiently justify Dagobert’s surveillance; but Prince Djalma was accomplished in every respect; we do not believe it is possible to realise a type more exactly; never did the head of an Indian character roll eyes so full of fire and lightning beneath bluish eyebrows and a white turban; with his thin arched nose, smooth cheeks, crimson mouth, and gold-coloured complexion, one thought of Rama setting out to conquer the island of Sri Lanka. He paced the stage in white clothing enhanced with scarlet decorations like blood-stained netting, with the motion of a young tiger, at the same time both languid and abrupt. Rodin, who is the whipping-boy of the play, and whom the public’s hatred prefers perhaps to address by another name, save for the hat with immense brims, possessed the complete physiognomy of Beaumarchais’ Basile (see ‘Le Mariage de Figaro’), with a nuance of his Tartuffe in addition: the black coat, short trousers, stockings and shoes indicated the priest most effectively; the actor, to please the public, had acquired all the ugliness that can be produced with coal, ochre and bistre; he was truly hideous, with a low forehead, dark eyes, livid cheeks and a bluish beard reaching to his cheekbones; the blue-cholera, on leaving the pestilential estuary of the Ganges, grants an appearance no more cadaverous or more dreadful. With each contortion that suffering drew from him, as that terrible illness gripped him, there was applause and a frantic stamping of feet. The foyer, where one can smoke, is in the open air; the actors, who have no dressing room, dress pell-mell behind the scenes, in a kind of wooden hut, as at the Hippodrome in Paris.

That evening, we halted near the cathedral, in front of the puppet-theatre, where the puppets were distributing blows from their sticks, and hanging over the edge of the stage, like the wooden actors of the Guignol theatre on the Champs-Élysées. The dialogue, in Milanese patois, was unintelligible to us, and the comedy was thus reduced to pantomime; the character who seems to fulfil the role of France’s Punchinello and England’s Mr. Punch, is a sort of Harlequin character who often hunches himself up to defend himself from his opponents’ blows.

On our return to the hotel, as we were gazing at an engraving of the Last Supper, by Leonardo da Vinci, which we thought completely lost, as reported by various travellers, we were informed that it still existed, and was still quite visible, in the convent, transformed into an Austrian barracks, next to the church of Santa Maria della Grazie.

The next day, our first visit was to that charming church, partially designed by Bramante, and built wholly of brick, which the plaster, fallen in many places, reveals like exposed flesh, and which gives the building, though dilapidated, a pink and white appearance, and a youthful lively air; the side-chapels are decorated with frescoes representing various torments; on the door of one of these chapels are framed two bronze medallions of the Virgin and Christ, done with flowing expressiveness and delicately worked; the low vaults, and the inlays of marble, mirror glass, and faceted crystal that decorate them, are entirely in the Spanish taste, and I saw a very similar effect achieved in the convent of San-Domingo, in Granada.

Leaving the Church through the sacristy, whose blue ceiling is strewn with golden stars, we emerged into the cloister of the old convent. War inhabits that ancient asylum of peace; soldiers, these violent monks, have replaced the previous monks, those peaceful soldiers; monasteries are well suited to use as barracks; military regiments and religious communities, those solitary multitudes, resemble each other in one regard: the absence of family. The pavements of the long arcades, troubled formerly by the monotonous sound of sandals, resonate today beneath the butts of rifles; the drums beat where bells rang; oaths are uttered where prayers were murmured; military life, with its brutality, spreads through the courtyards: here a shirt is drying; there a pair of trousers frolics in the wind; everywhere there are open boxes, racks of weapons, mess bowls and food parcels, the disciplined disorder of camp. Along the walls, scored by time or the carelessness and impious grossness of the soldiery, one can still discern paintings representing the miracles of the founder of the order, always busily thwarting the temptations of the devil, who sometimes appears to him in the shape of a cat, sometimes disguised as a monkey, or, worse still, in the guise of a beautiful woman.

Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper occupies the north wall of the refectory. The south wall is covered with a Crucifixion by Donato Montorfano, dated 1495. Talent is displayed in that work. But who can compare with Leonardo da Vinci? Certainly, the state of degradation of his masterpiece of human genius is forever regrettable; and yet it does not harm his reputation him as much as one might think. Leonardo is the painter par excellence of the mysterious, the ineffable, the twilit; his painting has the air of music in a minor key. His shadows are veils that he half-closes or deepens, so as to pursue a secret thought. His tones fade like the colours of moonlit objects, his contours are enveloped and drowned as if behind black gauze, and time, which hurts other painters, adds to his works by reinforcing the harmonious darkness in which he liked to immerse himself.

Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper

The first impression that this marvellous fresco makes is dreamlike, every trace of art has vanished; it seems to float on the surface of the wall, which absorbs it like a slight mist. It is the shadow of a painting, the spectre of a masterpiece that remains. The effect is perhaps more solemn, and speaks to one more religiously, than if the painting were vibrantly alive; the body has vanished, but the spirit survives in its entirety.

Christ occupies the middle seat at the table, with the beloved apostle Saint John on his right; Saint John’s attitude is one of swooning adoration, his look attentive and gentle, the mouth half-open, the face still; he leans towards Saint Peter respectfully, but affectionately, his heart heavy for his divine master. Leonardo has drawn the apostles with bold, strongly-accentuated outlines; for the apostles were fishermen, labourers, ordinary men. They indicate, by the energy of their features, by the power of their muscles, that they are the emerging Church. John, with his feminine figure, his pure features, his complexion fine and delicate in tone, seems rather to belong to the angels than to mankind; he is more aerial than terrestrial, more poetic than dogmatic, more a lover than a mere believer; he symbolizes the passage from humanity to the divine. Christ carries, imprinted on his face the ineffable gentleness of the willing victim, the paradisial azure behind his head gleams also in his eyes, as words of peace and consolation fall from his lips like heavenly manna in the desert. The tender blue of his eyelids, and the matt surface of his skin, echoes of which seem to have coloured the pallid face of Charles I, as painted by Anthony Van Dyck, reveal the sufferings of the Cross borne with a resigned conviction, within. He accepts his fate, resolutely, and does not turn from the sponge of gall at this last meal taken in freedom. One feels the presence of the entirely moral hero, whose power is of the spirit, portrayed in this figure of incomparable sweetness: the carriage of the head, the fineness of the skin, the delicate yet robust limbs, the pure line of the fingers, all denote an aristocratic nature set amidst the rustic and plebeian faces of his companions. Jesus Christ is the son of God; but he is also of the line of the kings of Judah. Did not a wholly spiritual religion require its revelation to be delivered by a tender, elegant and beautiful figure, whom little children could approach without fear? Sit Socrates in Jesus’ place, at this supreme moment, and the character of the scene is immediately altered: the former will ask that a cockerel be sacrificed to Aesculapius, the latter will offer himself as the hostia, the sacrificial victim; the serenity of Christian art overcoming, here, the beauty of the art of the Greeks.

We could have stayed several more days in Milan, paying visits to the sixteen ancient Columns of San Lorenzo, the great hospital (the Policlinico), the Villa Belgiojoso, and several rich or beautiful churches; but we adhered to the principle of not seeking anything further in a given place after an experience arousing profound emotion, and Leonardo’s Last Supper seemed unsurpassable; and then, Venice had an unconquerable attraction for us.

The railway runs to Treviglio; continuing from there by diligence we traversed Brescia at night, halting there for an hour. Of Brescia I can say nothing, except that the houses, vaguely outlined in the shadows, seemed extremely tall, and that the water of a fountain, in a square, reached by ascending a few steps, brought us the greatest of pleasures by its freshness. Groping about in the darkness, we drank several mouthfuls while the relay horses were harnessed.

In the brightly-lit porch of the inn, a theatre poster was visible. Two ballets were announced for the day of the next fair, the dances from Handel’s Alcina, and Giselle (whose story Gautier wrote with Jules-Henri Vernoy), performed by Augusta Maywood, an American dancer, who adorned the stage at the Paris Opéra several years ago. The Brescians were raised in our esteem from that moment, and the superiority of dance and mime, intelligible in every country, was increasingly demonstrated to us.

From Brescia to Verona there was little of note, except for a view of Lake Garda, near Peschiera, since we travelled like Homer’s deities, in a cloud; a cloud of dust.

Verona, whose name one cannot pronounce without thinking of Romeo and Juliet, where Shakespeare’s genius created two characters so real that history would like to accept them as such, presents itself to the traveller’s eye in a rather picturesque manner. We followed the Adige for a while, which is spanned by a large and singular bridge of red brick (Ponte di Castel Vecchio), with three arches of differing spans, parapets toothed with Moorish crenelations like the walls of Seville, and steps which inhibit carriages from crossing. Red saw-toothed towers raise their outlines fittingly against the horizon, and a beautiful antique portal, composed of two orders of columns and superimposed porticos, majestically receives the pilgrim.

The Montagues and Capulets could meet and quarrel, now, in the streets of Verona, and Tybalt kill Mercutio there; the scene has not changed: Shakespeare’s tragedy is wonderfully accurate. In Verona, as in Spanish towns, there is scarcely a house without a balcony, providing plenty of opportunities for a silken ladder. Few cities have better preserved their Medieval character: the pointed arches, the trefoil windows, open balconies, houses with pillars, sculpted street corners, and large mansions with bronze doorknockers and ornate grilles, their entablatures crowned with statues, glow with architectural details that the artist’s pencil alone can render, and transport you to a past century, so that one is astonished to see people in modern dress, and Austrian uhlans (lancers) traversing the streets.

Verona - View of the city from the bell-tower of San Zeno

This effect is especially noticeable in the crowded Market Square (Piazza delle Erbe) bright with watermelons, lemons, citrons, and tomatoes. The houses, painted with frescoes by Paolo Albasini, with their protruding miradors, sculpted ornaments, and robust pillars, display a most romantic physiognomy; columns with ornate capitals make of the square a motif for watercolourists and painters. It is the liveliest place in the city. Women show their faces everywhere at windows and in doorways, and a swarming crowd moves between the merchants’ stalls.

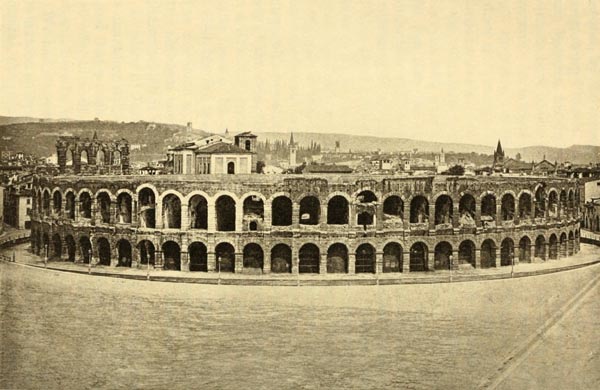

Between the apocryphal Tomb of Juliet, a sort of trough of reddish marble half-buried in a garden, the Scaliger tombs in Via Santa Maria Antica, and the ancient amphitheatre, we chose, being unable to visit everything, the Roman arena, which is better preserved than the Circus at Arles.

Verona - The Roman arena

All that is lacking in regards to this arena is the exterior wall; the five or six arches which remain intact would allow a straightforward restoration: a few weeks spent repairing the exterior would allow those bloodthirsty Games to be restarted. While ascending and descending the stone tiers, their edges as perfect as if they had been cut yesterday, we said to ourselves: ‘What an admirable place for a bullfight, and what fine blows Paquiro (Francisco Montes Reina), Chiclanero (José Redondo Dominquez), and Cucharès (Francisco Arjone Herrera), would have dealt the Gaviria and Veraguas bulls in this arena which drank the blood of lions and gladiators!’ We recognised the areas that had housed the gladiators, and the ferocious animals they fought; the entrances and exits for actors, the gangways for the crowd, and the outlets for water after a naumachia were perfectly visible; all that was missing was the audience, buried beneath the dust scattered by Jehoshaphat. As if the Veronese wish to contrast our modern mediocrity with ancient grandeur, they have built a stage of wooden planks within the arena, the seating for which barely covers a few rows of the tiered stands; twenty-two thousand people sat, at ease, in the Roman amphitheatre.

While on our way to the railway station which connects Verona to Venice, we heard drum-rolls and noted the movement of troops, and saw a crowd of people all heading in the same direction: we were told that seven brigands were to be executed, and that five had been shot to death the day before. If time had allowed, we would have attended the execution, which in our own country we would have fled from, since when travelling curiosity sometimes extends as far as barbarism, and eyes that seek the new do not always turn away from witnessing punishment, if the executioner is picturesque, and the victim exhibits local colour.

Fortunately, the guard’s whistle made us abandon this cruel thought, and we seated ourselves in the railway carriage, divided from end to end by an aisle, in which two venerable Capuchins had already taken their place, the first monks we had seen. It was six o’clock. We were due to arrive in Venice at eight-thirty.

Part VII: Venice

I feel a degree of shame on behalf of the Italian sky, which, in Paris, we had believed to be of an unalterable blue, in saying that large black clouds blocked the horizon on our departure from Verona; it is sad to begin a journey in the land of the sun with the description of a storm, but truth forces me to confess that the rain fell in vast tranches, first on the distant, then the nearest tracts of terrain, through which the railroad bore us.

Mountains crowned with clouds, hills brightened by castles and country-houses, formed the background to the picture. The foreground consisted of crops, of a very green, varied and picturesque appearance. The vine, in Italy, does not merely stand upright as in France; it is made to climb and hang in garlands from trellises after topping the poles it festoons with its foliage. Nothing is more graceful than the long rows of these vines which, linked by their twining arms, seem to join hands and dance about the fields in an immense farandole; they look like choirs of leafy bacchantes celebrating the ancient festival of Lyaeus, in silent transport: madly coursing from branch to branch, the vines grant the landscape an unimaginable elegance. Near and far, open porticos revealed the farm-workers happily eating their evening meal, and adding to the table’s liveliness.

Let me note here some specifics with regard to the Italian railway system. On the signs marking the distance travelled, there is also an indication of the steepness or elevation of the ground. Signalling is achieved by means of baskets of a particular shape, hoisted on large masts to agreed heights. The track is single with no return rail. At the stations, which are quite frequent, traders offer little pastries, lemonade, and coffee that you have to swallow while boiling, since one had better not raise the cup to one’s mouth when steam rises, the whistle emits its shrill cry, and the convoy starts moving again.

The railway skirts Vicenza, and soon arrives in Padua, of which I can say no more than the sentence which serves as an indication of the setting for Victor Hugo’s play Angelo, the Tyrant of Padua: ‘On the horizon, the silhouette of Medieval Padua.’ A bell-tower and a few domes outlined in black against a strip of pale sky, is all we were able to discern; but we will compensate for it later.

The weather failed to mend; gusts of wind, puffs of rain, and sudden flashes of lightning pursued the carriages in their flight; it was almost cold, and the good old peacoat which has rendered me such loyal service in Spain, Africa, England, Holland, and on the banks of the Rhine, granted me the convenient shelter of its vast bulk and long sleeves. Though the locomotive was pulling us along at a brisk pace, it seemed to me, so great was our impatience, that we were travelling on one of those chariots drawn by snails seen in Raphael’s Arabesques. Every man, poet or no, chooses one or two cities, as his ideals, which he inhabits in dream, imagining the palaces, streets, houses, views, according to some internal architecture, almost as Piranesi constructed his chimerical buildings with an etching needle, buildings which are nonetheless endowed with a powerful and mysterious reality. What creates the foundations of an inner city? It would be difficult to say. Tales, engravings, the view of some map; sometimes the euphony or singularity of a name; a story read when we were very young; the slightest particular, everything contributes, everything adds to its detail. For my part, three cities have always occupied my thoughts: Granada, Venice and Cairo. I was able to compare the real Granada to my Granada, and set up my camp-bed in the Alhambra: but life is so ill-constructed, time passes so awkwardly, that as yet I knew Venice only as an image traced in the darkened chambers of the brain, where images are often lodged so deeply that the reality scarcely erases them. We were only half an hour away from Venice itself, yet I, who have never wished a single grain of sand to accelerate its fall through the hourglass, so certain am I of death’s approach, would have gladly deleted those thirty minutes from my life. As for Cairo, that is another score to settle, and besides Gérard de Nerval has already viewed it on our behalf.

Despite the rain lashing our faces, we leaned out of the carriage-window to try and capture, in the darkness, a distant outline of Venice, the vague silhouette of a bell tower, a gleam of light; but night was deepening, and the shadows impenetrable; finally, at a station, an announcement warned those of us who wished to quit the train at Mestre. It was not long ago that one embarked for Venice there; now the track has rendered the gondola useless: an immense bridge spans the lagoon, and has welded Venice to dry land.

I had never experienced a stranger feeling. The train had just entered the length of track. The sky was like a dome of basalt striped with brownish veins. On both sides, the lagoon, in a moist darkness more sombre than night itself, stretched into the unknown. From time to time, pale lightning-flashes shook their torches over the water, which was revealed by each sudden blaze of fire, and the train seemed to ride the void like a hippogriff in nightmare, since we could distinguish neither sky, nor water, nor bridge. Certainly, it was not how I had dreamed of my entry to Venice; but this method exceeded in fantasy all that John Martin’s imagination might have produced by way of the mysterious, gigantic, and formidable in depicting an avenue in Babylon or Nineveh. The storm and the night had prepared the canvas in shades of darkness on which the lightning drew lines of fire; while the locomotive looked like one of those biblical chariots whose wheels whirled round like flames, delighting some prophet in the seventh heaven.

Our vertiginous course lasted only a few minutes, before the locomotive slowed and stopped. A large landing-stage, without any architectural adornment, receives travellers, who are asked for their passports, while being given a card to allow their later retrieval. Our luggage was piled onto an omnibus, a gondola fitted out like a flat-bottomed barge, and we set off. The Auberge d’Europe, which we had been informed of, was located at precisely the other end of the city, a circumstance that we were not then aware of, and which led to the most astonishing voyage one can imagine: it was not a journey beneath Friedrich Tieck’s blue azure, but a journey into the dark, as strange and mysterious as those performed in nightmares, on that demon of the night Smarra’s bat-like wings.

To arrive at night, in a city you have dreamed of for many a year, is simply an accident of travel, but one which seems guaranteed to drive the traveller, consumed by curiosity, to the last degree of exasperation. To enter the house of one’s chimera blindfolded is the most annoying thing in the world. We had already experienced the same in Granada, where the diligence ejected us at two in the morning in a darkness of desperate opacity.

Our barge first followed a wide canal, at the edge of which shadowy buildings were vaguely outlined, dotted with a few lighted windows and lanterns which poured streaks of glittering light over the black quivering water; then it navigated various narrow canals, aqueous streets which made complicated detours, or at least it seemed so to us because of our ignorance of our course.

The storm, which was sinking to a close, still illuminated the sky with a few livid lightning-bolts revealing profound perspectives, and the strange outlines of unknown palaces. At every moment, we passed beneath bridges whose two ends announced a luminous break in the dark compact mass of houses. At a corner some night-light trembled in front of a Madonna. Singular cries and guttural sounds sounded at every bend of the canal; a floating coffin, over the end of which a shadow leaned, sped past us; a low window, close by, gave us a glimpse of an interior lit by a lamp or some reflection, like a Rembrandt etching. Doors, their sills licked by the swell, opened on emblematic, vanishing figures; flights of stairs came to bathe their steps in the water and seemed to climb the shadows towards mysterious Babels; the colourful posts to which the gondolas are moored took on spectral attitudes.

From the summits of the arches, visages vaguely human, like mournful faces in a dream, watched us pass. Sometimes the lights vanished, and we moved, sinisterly, through four levels of darkness, oily shadows, deep and humid water, the stormy shadows of the night sky, and the opaque darkness of the walls on either side, on one of which the lantern of the boat would cast its reddish reflection revealing pedestals, fluted columns, porticos, and iron-grilles which instantly vanished. All objects touched in the darkness by some stray shaft of light revealed mysterious forms, fantastic, frightening, misproportioned. Water, always so formidable at night, added to the effect with its dull splashing, its seething, restless life.

The rays of the rare street lamps were extended there, in blood-stained trails, and the dense waves, as black as those of Cocytus, seemed to spread their complacent mantle over many a crime. We were surprised not to hear a body fall from the top of some balcony, or from a half-open door; reality has never looked less real than on that evening.

We thought ourselves immersed in some novel by Charles Maturin, ‘Monk’ Lewis, or Ann Radcliffe, illustrated by Goya, Piranesi, and Rembrandt. The old tales of the Three Inquisitors, the Council of Ten, the Bridge of Sighs, masked spies, the prisons those ‘wells’ and ‘leads’, executions at the Orfanello canal, all the melodrama and romantic stage-sets of ancient Venice were recalled to our memories in spite of ourselves, further darkened by reminiscences of Radcliffe’s novel The Confessional of the Black Penitents (‘The Italian’) and Johann Zschokke’s play Abellino the Great Bandit (‘Abällino der große Bandit’). A cold terror, as black and clinging as all around us, now gripped us, and I thought, involuntarily, of Malipiero’s tirade to Tisbe (in the first act of Hugo’s ‘Angelo, the Tyrant of Padua’) in which he expresses the fear that Venice inspires in him.

The description of this feeling, which may seem exaggerated, is the most exact truth, and I think it would be difficult, even for the most philistine of positivists, to defend oneself from such an emotion; I would go even further, and say that this is the true essence of Venice, which emerges, at night, from amidst its modern transformations; Venice, a city which appears as if planned by a theatre-designer, and whose manners a playwright seems to have arranged to enhance the interest of intrigues and their denouements.

Darkness restores to her the mystery of which daylight despoils her, hands the ancient masks and dominos to the common inhabitants, and grants the simplest movements of life the appearance of an intrigue or a crime. Every door that gapes, seems to emit a lover or a cavalier. Every gondola, that glides by silently, seems to be bearing away an amorous couple, or a corpse with a broken dagger in its heart.

Finally, the boat came to a stop, at the bottom of a marble staircase, its lower steps bathed by the sea, in front of a facade which shed a blaze of light through all its openings. We had arrived at the old Palazzo Giustinian, transformed today to a hotel, like several other palaces in Venice. Half a dozen gondolas were grouped together at the landing like carriages waiting for their owners: a large staircase, quite monumental in nature, led us to the upper floors, each composed of a room, long and deep, with broad windows, and side apartments, overlooking both the canal and solid ground.

While waiting for supper to be served, we leaned on the balcony, decorated with marble columns and Moorish arches. The rain had ceased. The sky, purified and cleansed, was resplendent with stars; the Milky Way speckled the dark azure with a hundred million white droplets; and the rocket-like flares of numerous meteors crossed the horizon and swiftly faded from sight. Various bright points of light, earthly stars, sparkled on the other bank, which they marked out for us; the indistinct silhouette of a dome was outlined to our right; on the far side of the water, by leaning outwards a little, we discovered to our left a glittering line of fire, which we judged to be the street-lamps of the Piazzetta (the extension, in the south-east corner, of St Mark’s Square, the Piazza San Marco). A few small sparks, similar to those scattered by burning paper, swayed in the black depths. They were the lanterns of gondolas going to and fro.

It was not yet late, and we could have taken the air; but we promised ourselves not to mar our first view of St Mark’s Square, and decided to wait until next day, when daylight would fill the scene. Hence, we had the strength of will not to leave our room, where we soon fell asleep, despite mosquito attacks, while revisiting in our mind’s-eye the Venice of Canaletto, Richard Parkes Bonington, Jules-Romain Joyant, and William Wyld.

In the morning, our first thought was to rush to the balcony: we were at the entrance to the Grand Canal, opposite the maritime customs-house (Punta della Dogana), a beautiful building with rustic columns adorned with bosses supporting a square tower, topped with two statues of Atlas kneeling back-to-back and supporting on their sturdy shoulders a terrestrial globe, on which stands a movable figure of naked Fortune, bald-headed behind, hair dishevelled in front, her hands holding the ends of a veil which acts as a weather-vane and yields to the slightest breeze, the statue being hollow like the Giralda in Seville. Near the Dogana, rose the rounded white dome of Santa Maria della Salute, with its convoluted scrolled buttresses, its partly pentagonal steps, and its population of statues.

Venice - The Schiaconi Quay from the Custom House

An Eve in the boldest of negligees, smiled at us from the summit of a ledge in a ray of sunlight. We recognized the Salute, immediately, from Canaletto’s beautiful painting (‘The Entrance to the Grand Canal, and Sante Maria della Salute’) which is in the Louvre; behind, we could see the tip of the Giudecca, and the island of San Giorgio Maggiore with, above an Austrian battery, the Palladian church, its Greek facade, oriental dome, and Venetian bell-tower coloured the brightest of pinks.

Venice - Church of the Salute

A swimming-school was based at the mouth of the canal, and various boats of different tonnages, and the outlines of fishing-boats, three-masted ships, and a steamboat were visible in the blue serenity of morning. The boats that supply the city are powered by sail or oar, depending on their place of origin. It was a delightful picture, as bright as that of the evening before had been gloomy.

Walking around Venice is difficult for the stranger. Our first objective therefore was to rent a gondola. The gondola has been much-abused in comic operas, romantic novels, and short stories; giving good reason to render it better known. I will give a detailed description, here. The gondola is a natural product of Venice, an animated being with an individual, local life; a species of fish that cannot survive except in the waters of a canal. The lagoon and the gondola are inseparable, and complement each other. Without the gondola, Venice is unnavigable. The city is a stony coral-reef whose polyps are the gondolas. The gondola alone can meander through the inextricable network, the endless capillaries, of its watery streets.

The gondola, long and narrow, raised at both ends, and drawing very little water, is shaped like a ski. The bow is armed with an iron plate, flat and polished, which vaguely recalls a swan’s curved neck, or rather that of a violin with its pegbox, as the six gapped teeth, with which it is sometimes decorated, contribute to the resemblance. The iron plate serves as an ornament, a defence, and a counterweight, the boat bearing a greater weight at the stern; on the side of the gondola, near the bow and stern are inset two pieces of wood, shaped like the yoke of an ox, where the gondolier standing on a little platform leans on his upright oar, his heel supported by a cleat.

The visible parts of the gondola are coated with tar or painted black. A carpet, more or less richly woven, garnishes the interior; in the middle is the cabin, the felze which can be easily removed and replaced with a canopy as required, a degenerate innovation which make every true Venetian groan. The felze is hung with black cloth throughout, and furnished with two soft Moroccan-style cushioned seats with curved backs in the same colour; in addition, there is a folding seat at each side, so that four people can be accommodated, and a window which one usually leaves open, but which can be shuttered in three ways, firstly by a Venetian mirror, bevelled or framed by flowers engraved in the glass; secondly, by a louvre blind so one can see without being seen; or thirdly, by a panel of fabric over which, to achieve even greater privacy, the felze’s canopy can be lowered: these different systems slide on a transverse runner. The door through which one enters backwards, since it would be difficult to turn around in the narrow space, is simply a wooden panel with a piece of glass inset. The panel is carved with more or less elegance, depending on the owner’s wealth or the gondolier’s taste. On the left jamb of this door a copper shield surmounted by a crown gleams, on which a coat of arms or a number is engraved; below it, a small openwork frame faced with glass contains an image to which the owner or gondolier is particularly devoted: of the Blessed Virgin, Saint Mark, Saint Theodore, or Saint George.

This is also where the lantern hangs, the use of which is beginning to fade; many gondolas travel without revealing that star on their brow. Because of the coat of arms, the saint and the lantern, the left is the place of honor; that's where women sit, the elderly, and people of note. At the rear of the cabin, a moving panel allows you to speak to the gondolier stationed at the stern, the only person to actually steer the boat, his oar acting as both oar and rudder. Two silk ropes with grips help you rise when you wish to disembark, since the seating is placed very low down; the canopy of the felze is embellished on the outside with silk tassels quite similar to those of priests’ hats, and, when one wants to enclose oneself completely, spreads across the rear of the cabin like an overly-long funeral pall on a coffin. To complete the description, let me add that on the interior planking a species of arabesque is engraved in white on its black wooden field. All this seems less than cheerful, yet, according to Byron’s poem Beppo, scenes as amusing as those which take place in funeral carriages transpire in these black gondolas. The opera-singer Maria Malibran, who disliked entering the little catafalques, tried, though without success, to have the colour changed. The black livery, which might seem gloomy, does not appear so to the Venetians, accustomed to the colour by the sumptuary edicts of the old republic, whose water-hearses, funeral-biers, and undertaker’s clothing are red, by way of contrast.

We chose a gondola with two oarsmen: the one at the stern, scorched and annealed by the sun, with a little Venetian cap on the top of his head, a thick tawny collar of a beard, with sleeves rolled-up, and a belt and wide trousers, recalled the ancient tradition; the other, in the bow, smaller and more modern in appearance, wore a cap from which a curly lock strayed, a striped jacket of Indian cotton, and formal trousers, thereby mingling with the gondolier’s air that of a domestic servant. As the weather was fine an awning with blue and white stripes replaced, to our great regret, the felze in which we would have gladly suffocated with heat given our excessive love of local colour.

We asked to be conveyed at once to St Mark’s Square, where that row of gaslights had been shining, or so we had assumed, the previous evening. By taking the broad route, we could examine the facade of our lodgings, which was truly magnificent with its three floors of balconies, its Moorish windows and its marble columns. Without the unfortunate sign planted above the portico which contained these words: ‘Hôtel d’Europe, Marseille,’ the Giustinian palace would have been still as one sees it in that marvellous woodcut by Albrecht Dürer (‘A Bird’s Eye View of Venice’, in the Correr Museum) with the exception of two windows on the third floor, located next to the original bay, which can still be discerned in the wall; and the former owners, if they returned from the other world in a gondola steered by Charon, ferryman of the Acheron, would easily find their residence on the Grand Canal intact, though a little dishonored. Venice is unique in that, though the drama of its existence is over, the adornments of its past remain in place.

Gondoliers row while standing, leaning on their oar. It is most surprising that they succeed at every moment in not falling overboard, since the whole weight of their body is tilted forwards. It is only long experience at the task that grants them the necessary poise to remain always suspended thus. Their apprenticeship must involve more than one ducking; their skill in avoiding collisions is unequalled, as is the precision with which they navigate a street corner, or approach a traghetto (ferry), or a staircase; the gondola is so responsive to the slightest touch, that it seems like a living being.

A few strokes soon brought us to one of the most marvellous spectacles the human eye has ever contemplated: the Piazzetta seen from the sea! Standing at the bow of the stationary gondola, we gazed for some time, in mute ecstasy, at a scene unrivalled in all the world, and the only one perhaps that the imagination cannot outdo.

To our left, viewed from the water, we saw the trees of the royal garden, tracing a verdant line beyond the white terrace, then the Zecca (the Mint), a building of robust architecture, and the old library (Biblioteca Marciana), the work of Jacopo Sansovino, with its elegant arcades, crowned with mythological statues.

To our right, separated by a space occupied by the Piazzetta, the vestibule of St Mark’s Square, the Doge’s palace offered its vermilion diamond-patterned facade of white and pink marble, its massive pillars supporting a columned gallery whose ribs contain quatrefoils, its six, pointed windows, its monumental balcony embellished with platforms, niches, pinnacles, and statuettes, dominated by the Goddess of Justice; its parapet piercing the blue of the sky with alternating acanthus leaves and stone spikes, and the spiral columns which clad its corners, topped by an open-work turret.

Venice - St Mark’s, Piazzetta

At the rear of the Piazzetta, on the side containing the Library, the Campanile rises to a prodigious height, an immense brick tower with a pointed roof surmounted by a gilded angel. On the side containing the Doge’s Palace, St Mark’s Basilica, seen from its flank, reveals a corner of its portal, which faces the Piazza. The Perspective ends in the arcades of the Procuratie Vecchie (the Old Procuracies), and the Clock Tower, with its bronze Jacquemartes (a pair of bell-strikers), its Lion of Saint Mark against a starred blue background, and its large azure dial, marking the twenty-four hours of each day.

In the foreground, opposite the gondola landing-stage, between the Library and the Doge’s Palace, stand two huge columns of African granite in one piece, once rose-red but now bleached to cooler tones by the wind and rain.

On the left, again looking from the sea, atop a column, stands a statue of Saint Theodore, handsome in appearance, in a triumphant attitude, his forehead topped with a metal nimbus, his sword at his side, a spear gripped in in his fist, hand resting on his shield, treading a crocodile underfoot.

On the right, atop a second column, the lion of Saint Mark in bronze, wings outspread, claw on the Gospel, the muzzle frowning, turns his back on Saint Theodore’s crocodile, with the fiercest and most sullen air that a merely heraldic animal can adopt. The two monsters seem not to want to associate with one another.

They say it is an ill omen to disembark between these two columns, where executions were once carried out, and we begged the gondolier, when putting us ashore, to moor alongside the steps in front of the Zecca or at the Ponte della Paglia bridge, not caring to end up like Doge Marino Faliero, who was upset at having been hurled by the storm at the foot of those formidable pillars.

Beyond the Doge’s palace, to the right, one sees the Prigioni Nuove (the New Prison), to which it is connected by the Bridge of Sighs, a kind of cenotaph suspended above the Rio de Palazzo north of the Ponte della Paglia; then a curving line of palaces, houses, churches, buildings of all kinds, which forms the Slavonic Quay (the Riva degli Schiavoni), and ends in the verdant massif of the public gardens, the tip of which juts out into the sea.

Near the Zecca, opposite the Punta della Dogana, the entrance to the Grand Canal forms the near end of the panoramic arc of Venice which stretches from the public gardens to that point, and which presents the city like a sea-born Venus, the salty pearls of her natal element now drying on shore.

I have indicated, as precisely as I can, the main lineaments of the picture; but what is lacking is the effect, the colour, the movement, the frisson of the air and the water that is life. How to express those pink tones of the Doge’s Palace, that seem those of living flesh; the snowy whiteness of the statues, their flowing lines revealed beneath the azure skies of Veronese and Titian; the redness of the Campanile, which the sun caresses; the flashes of distant gold, the thousand aspects of the sea, sometimes clear as a mirror, sometimes glittering with sequins like the skirt of a dancer? Who can portray the vaguely luminous atmosphere, full of rays of light and mist from which the sun fails to exclude the clouds; the to-ing and fro-ing of gondolas, barques, argosies, galiots; the sails gleaming red or white; the ships resting their figureheads familiarly on the quay, with their thousand picturesque features, their flags, their ropes and netting drying in the sun; the sailors loading and unloading the boats, the boxes they carry, the barrels they roll along, the motley pedestrians on the mole, Dalmatians, Greeks, Levantines, and the rest, whom Canaletto would have indicated with a single brushstroke? How to show all of this simultaneously, as in nature, in unfolding procession? For the poet, less fortunate than the painter or the musician, must progress line by line, while the former has a whole palette, the latter a whole orchestra?

The Piazzetta landing-stage is adorned with Gothic lanterns, and decorated with the figures of saints, planted on poles rising from the water. One of these lanterns was donated by the Duchess de Berry. Gondolas riot about in this area, the busiest of all. To approach the shore, the axe-like prow of the boat is employed as a wedge, with the help of which the mass of boats can be parted. As one approaches, a crowd of rascals, old and young, dressed in rags, came running, each holding in one hand a stick armed with a nail, which hooks the boat like a gaff, and holds it while one sets foot on the ground, an operation which at first presents a degree of difficulty, given the extreme mobility of the frail boat. You become aware that their concern is not simply to prevent you from falling into the water, or bathing your feet on the lower step, since a dusty hand or a greasy hat, humbly extended, invites you to drop therein a sou or an Austrian kreuzter, their reward for this small service.

On the bases of the two columns, sit the gondoliers waiting for a fare, the beggars, the skinny half-naked children looking to make a living on the stairways of Venice, a whole picaresque population, lover of far niente (idleness) and the sun. The column-bases were once decorated with sculptures now almost erased by friction, which seem to have represented figurines holding fruits and foliage. How many trouser-bottoms it must have taken to wear down the granite is a problem I leave to mathematicians with little to solve. To complete my comments regarding the columns, let me say that Saint Theodore’s leans a little in the library’s direction, while that supporting the lion of Saint Mark leans towards the Doge’s Palace.

The first steps we took towards the Piazzetta brought us to an Austrian gatehouse striped in yellow and black, alongside four cannons with yellow-painted mountings, their muzzles stoppered with tampions, their ammunition caissons behind, forming a kind of artillery park abutting on the pointed arcades of the Doge’s Palace. Political ideas aside, the scene shocks one like a dissonance in a symphony otherwise admirable in nature; it is a crudity that sits heavily with the poetry of the view.

The facade of the Doge’s Palace overlooking the Piazzetta, is like a face gazing at the sea; the one and the other form that monumental intersection where Daniele Manin, resigning the provisional government after the capitulation of Venice in 1849, harangued the populace for the last time.

At the end of the Piazzetta is the Piazza, which is at right-angles to it, and which, as its name indicates, is much larger.

The four sides of the Piazza are occupied by the façade of the Basilica of San Marco, north of the Doge’s Palace, the Clock Tower, the Old and New Procuracies, which blend with it, and an ugly modern palazzo in classical style, foolishly built, in 1809, to make a throne-room (the Napoleonic wing of the Procuracies), in place of the delightful church of San Geminiano, whose elegant style had corresponded so well to that of the Basilica. The Campanile, adorned at its base with a charming small building designed by Jacopo Sansovino, called the Loggetta, is isolated and stands at the corner of the New Procuracy; approximately in line with it, are planted the three masts which supported the standards of the republic.

By walking towards the rear of the square, one enjoys a truly magical scene that proves dazzling, however prepared for the sight one is by art-works, and description. San Marco is before you with its five domes, its porches gleaming with gold-ground mosaics, its openwork bell-towers, its immense arched glass window, in front of which the four horses of Lysippus paw their stone plinths, its columned galleries, its winged lion, its pointed flowery gables whose foliage bears statues, its pillars of porphyry and antique marble, its appearance of being at the same time temple, basilica and mosque: a strange and mysterious building, exquisite and barbaric, an immense pile of riches, a church built by pirates, formed of fragments stolen or won from every known civilisation.

The bright light made the great Evangelist shine, against his heavens starred with gold; the sparkling mosaics glittered; the domes, rounded like the domes of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, were a silvery grey, and clouds of doves flew from time to time about the cornices and balustrades, landing familiarly on the square. It seemed like an oriental dream, petrified by the power of some enchanter, a Moorish church, or a Mosque raised by a caliph converted to Christianity. During our walk I failed to take in all the detail, and the impression I will convey is therefore incomplete; rather it is a general one, coloured in the lively tones that one sees at first glance. We will now, if you wish, ascend the Campanile. Such is my habit when I arrive in a city: I prefer a relief map to all the plans and guides in the world. Thus, I immediately head for the highest point of each place in which I choose to stay.

Like the Giralda in Seville, the Campanile has no stairs: one ascends via a ramp that could be climbed on horseback, as the slope is quite gentle. The interior of the Campanile is filled by a brick cage around which the ramp turns, and which is windowed by large elongated openings. At each pillar a small loophole pierced in on one of the faces of the tower allows sufficient light. After climbing for a long while, one reaches the platform, where the bells hang. Columns of green and red marble support four arcades on each side below the Campanile’s summit, providing a view towards the four points of the horizon; a spiral staircase allows you to climb even higher, to the foot of the gilded angel, but it is an unnecessary task, since a complete panorama of Venice is visible from the lower level.

If, while leaning on the balustrade, face turned away from the sea, one looks down, one sees firstly the roof, populated by Venus, Neptune, Mars, and other allegorical figures, of Sansovino’s Library, today a royal palace, then that of the Doge’s Palace, covered with lead, the eye plunging also into the courtyard of the Zecca, while the Piazzetta, with its columns and gondolas, displays its patterned paving. Further off is the sea, with its scattered islands and boats.

San Giorgio Maggiore with its red bell tower, its two white bastions, its basin, and its line of vessels attracted by the free port, appears in the foreground. A canal separates it from the Giudecca, a maritime suburb of Venice which presents a line of houses towards the city, a belt of gardens towards the sea. The Giudecca has two main churches, Santa Maria della Presentazione (the Zitelle) and the Redentore (Chiesa del Santissimo Redontere), whose white dome houses a Capuchin convent.

Beyond San Giorgio to the south-east, we discover the Sanita a tiny islet; San Servolo, where the asylum for the insane is located; San Lazarro, with its Armenian monastery and college of oriental languages; and finally, the Lido, an arid and sandy beach, which, with the long, low, narrow tongue of land of Malamocco, provides Venice with a rampart against the tides of the Adriatic.

Beyond the Giudecca to the south, sinking less into the horizon, are La Grazia; San Clemente, a place of penance and detention for disciplined priests; Poveglia, off which vessels are quarantined; and, following the line of Malamocco, and almost invisible amidst the glitter of the waves, the village of San Pietro in Volta (on the island of Pellestrina). The islands are often marked by one of those tall red Venetian bell-towers of which the Campanile seems to be the prototype.

Over the water move a vast crowd of ships, gondolas, every manner of vessel: while we were on top of the bell-tower, the steam-boat from Trieste arrived spewing vapour, its paddles turning, and making great swirls in the tranquil sea of which, in places, we could see the bed; lines of piles mark routes through the lagoon passable by ships, for the depth is ordinarily only three or four feet; these stakes seen from above look like men fishing in water up to their thighs.

Further off, the eyes are lost among large azure circles that you might take for sky, if some sail gilded by a ray of sunshine did not warn you of your mistake.

The transparency of the air, the limpidity of the waters, the radiance of the light, the sharpness of the silhouettes, the depth and subtlety of tone, gave this immense view a dazzling, dizzying splendour.

Looking to the west of the Piazza, from south to north, the perspective presents itself thus: the line of the Giudecca; the Dogana with its statue of a dishevelled Fortune, whose globe, which is in process of being re-gilded, shines with a brand new gleam; Santa Maria de la Salute with its double dome; the entrance to the Grand Canal which, despite its width, soon vanishes between the houses; San Moisè and its bell tower, joined to the church by a bridge; Santo Stephano, its brick tower topped by a cross; the large reddish church of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, raising its angular facade above the roofs; the blackish-green dome of San Simeone Piccolo, the only dome in Venice of that colour, being covered in copper and not lead, which produces, amidst the silver casques of the other churches, the effect of the armour of the ‘unknown knight’ in some Medieval tournament; and then, at the end of the still invisible canal, San Geremia, whose dome and tower were shelled during the siege (of 1849). Beside San Geremia, the trees of the Botanical Gardens show their verdure, and the Chiesa degli Scalzi, next to the railway station, reveals its facade under repair, encumbered with scaffolding.

Between all these churches, which overtop the inferior buildings by the height of their conception, lies a tumultuous ocean of disordered roofs and tiles, of thousands of circular, square, and flared chimneys, crenelated and turreted, and blossoming like flower pots, of the weirdest and most unexpected shapes; ignore some pediment, some corner of a palace emerging from the hustle and bustle of the houses, and you have the foreground, bathed in a clear, warm, golden light, contrasting admirably with the vague blue of the sea beyond the roofs to the south-west, dotted only by two islands, Sant’Angelo delle Polvere and San Giorgio in Alga.

On the far horizon to the west, the Euganean hills, southerly offshoots of the Dolomites, undulate in azure lines. At the foot of the hills, wide green stripes indicate the fertile fields of the mainland, and Padua is silhouetted there, blurred by distance; an ashen beach, which the tide leaves uncovered, since there is an ebb and flow in the Adriatic though barely any in the Mediterranean, serves as a transition and half-tone between land and water. The railway-bridge, easily visible from this height, crosses the lagoon, connects Venice to the continent, and makes a peninsula of an island. Fusina and Mestre are on the far side, the former to the left of the railway, the latter to the right.

The third window of the Campanile, facing the Clock-Tower to the north, frames the Chiesa della Madonna dell’Orto, whose tall, red, domed bell-tower, and large tiled roof, stands out clearly; the Holy Apostles (Chiesa dei Santi Apostoli di Cristo), with its white turret, adorned with a dial, and a cross above a globe; and the Jesuits (Chiesa di Santa Maria Assunta detta I Gesuiti), its statues contorted and out-thrust from the pediment dancing against the blue of the sea; plus, the obligatory accompaniment of chimneys and roofs.

What is singular is that nowhere do we catch sight of the Grand Canal; there is not even a suspicion of its stretches of water that should appear like streets among the islands of houses; everything forms a compact block, a frozen tempest of tiles and attics, amidst which the churches float like ships at anchor.

By leaning a little to the east, one’s eye encounters the bell-tower and grey dome of the Basilica dei Santi Giovanni et Paulo, a vast brick building: then the elegant tower of Santa Maria Formosa, whose whiteness contrasts with the pinkish tones of the whole; further west in the sea lies the island fortress of San Secondo. Offshore, the cemetery-isle of San Michele, surrounded by pink walls, and flanked by two churches, San Cristoforo and San Michele, offers up its little green rectangle dotted with black crosses. In the same direction, in the middle of the lagoon, is Murano, where the Venetian glassware was made which still adorns dressers, the reddish bell-tower of its Church of the Angels (Santa Maria degli Angeli) attracting the eye, along with the roof of San Pietro Martire, and three tall cypresses, which rise like a trio of dark spires from a cluster of houses and trees.

From the fourth window of the Campanile, beyond the Doge’s Palace, we discover, to the east, San Francesco della Vigne and its bell tower, remarkable for its pinkish panels edged with white; San Zaccaria, whose greyish dome surmounted by a globe with a cross like St Mark’s column, and tall facade composed of three curved pediments, emerges from among the houses; the Arsenal, with its square towers, pink above, white below, its docks of shimmering water, its large hangars arched like aqueducts, its pulleys, machinery, and general appearance of a magazine and rope-making factory; and further off the dome and bell-tower of the Basilica di San Pietro di Castello, and the triangular pediment and spire of Sant’Elena.

Offshore, looking towards the open water to the north-east, the islands of Burano, Mazzorbo and Torcello, where the first Venetians lived, can be seen; the distance presents only flat isles lush with cultivation, a few scattered houses, and three churches, one more visible than the others.

Otherwise, all is sky and water, festooned with foam, a passing sail, a gull flapping its wings amidst blue and luminous vapour; a bright immensity, the greatest of immensities!

In the surround to this window carved in letters characteristic of the calligraphy of his day, can be read this inscription, engraved with a knife: Adrian Ziegler, 1604. Was this some ancestor of the modern painter of that name; one who left, in the surface of the Campanile, this trace of his visit to Venice?

Knowing its general configuration, we can now descend to the city, traverse it in every direction, and examine every detail; Italy, as everyone knows, has the shape of a riding-boot; Venice has the appearance of a thigh-boot. The upper part is formed by the districts of Dorsoduro and Santa Croce, the leg by St. Mark’s, Cannaregio, and Castello, the toe by the public gardens, the heel by the islands of San Pietro, and the under-strap by the Castello bridge. The Grand Canal, winding across the top of the boot, would represent the stitching on the flap.

Part VIII: St Mark’s Basilica – The Exterior

Venice - Saint Mark's Square

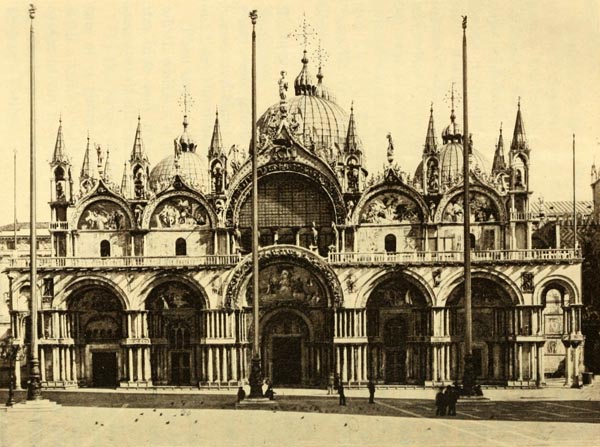

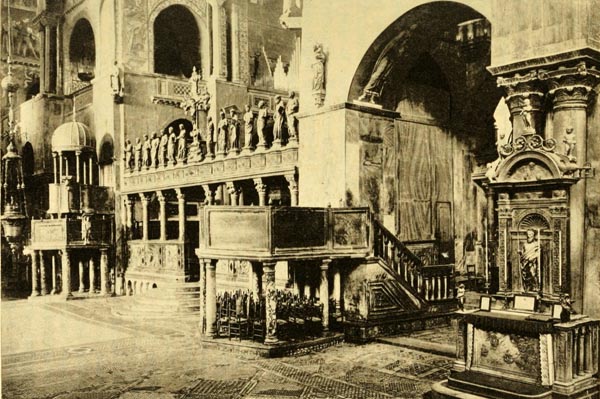

In describing the Piazza, I have given the general appearance general of Saint-Mark’s, as can be grasped at first sight; but Saint-Mark’s is a world of itself about which one could write volumes, and still return to create more.

Like the mosque of Cordoba, with which it shares more than one point of resemblance, the Basilica di San Marco, possesses more breadth than height, contrary to the habit of Gothic churches to rush towards the heavens defended by ogives, pinnacles, and spires. The large central dome is only one hundred and forty feet high. St Mark’s has retained the character of primitive Christianity, when, barely out of the catacombs and not yet having formulated a style of its own, it sought to build a church based on the remains of ancient temples, and the designs of pagan art. Begun in 979, under Doge Pietro I Orseolo, the present Basilica of Saint Mark was gradually completed, enriched, in each century, with some new treasure, some new beauty, yet this singular building, which eschews any notion of proportion, this collection of columns, capitals, bas-reliefs, enamels, and mosaics, this mixture of Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Arabic, and Gothic styles, exhibits an almost harmonious whole.

This incoherent temple, where the pagan might find his altar to Neptune, with its dolphins, tridents, and conch-shell serving as a font; where the Muslim might believe it a mosque, on seeing the inscriptions on the walls and the vaulted dome, much like suras of the Koran; where the Greek Christian might find his Panagia crowned as Empress of Constantinople, his barbarous Christ with an interlaced monogram, and the special saints of his calendar, done in the style of Manuel Panselinos and the artist-monks of the holy mountain (Mount Athos); where the Catholic feels, in these shadowy naves, illuminated by the tawny reflection of the golden mosaics, the living heartbeat of the absolute faith of the earliest days, of the submission to dogma and hieratic forms, of the mysterious and profound Christianity of the ages of belief; this temple, I say, made of bits and pieces that contradict each other, enchants and caresses the eye more truly than the most correct, most symmetrical architecture could achieve: unity is born from multiplicity. Full arches, ogives, trefoils, columns, fleurons, domes, marble slabs, the gilded backgrounds and bright colours of the mosaics, all this is arranged with a rare fortuity, and forms the most magnificent of monumental bouquets.

Venice - Saint Mark's, facade

The facade facing the square has five porches giving onto the church, and two leading to the exterior lateral galleries; in all, seven openings, three on each side of the large central porch. The main door is marked by a group of columns at each side, four of porphyry, and one of ‘antique green’ serpentine, and two groups of three serpentine columns above supporting the curve of the semicircular arch. The other porches possess only two columns on each level. I am speaking here only of the facade itself, since the areas between the porches are adorned with other columns in Cipollino marble, jasper, Pentelic marble, and other rare materials.

Let me examine the mosaics and the ornamentation of this marvellous portal in some detail. Starting with the first main arch on the seaward side, one notices, above a square a door closed by a grille, a black and gold Byzantine feature in the shape of a reliquary, with two angels attached to the ribs of the ogive. Above this, the tympanum of the semicircular arch, presents a large mosaic on a gold background, representing the body of Saint Mark removed from the crypts of Alexandria and smuggled through the Turkish guards between two sides of bacon, the pig being an animal Muslims consider filthy and are horrified by, and contact with which would drive them to endless purification and ablution. The infidels move away with gestures of disgust, and unwittingly allow the body of the apostolic saint to be borne away. This mosaic was executed according to the design created by Pietro della Vecchia, in about 1640. In the gap (spandrel) between the arches, on the right, is embedded an ancient bas-relief of Heracles carrying the Ceryneian Hind on his shoulders and treading the Lernaean Hydra underfoot, while on the left (from the spectator’s point of view), by one of these contrasts so frequent in St Mark’s, we see the angel Gabriel standing, winged, haloed and booted, leaning on his spear; a singular counterpart to the son of Zeus and Alcmene!

In the next arch to the left a wider door was cut, surmounted by a triple-arched window, at the top of which are two quatrefoils surrounded by a border of enamel. The mosaic of the tympanum, also on a gold background, like all those of Saint Mark, has as its subject the arrival of the body of the Apostle at Venice, where it was received, upon being disembarked from the ship, by the clergy and principals of the city; we see the vessel which transported it and the wicker baskets that contained it: this mosaic was also designed by Pietro della Vecchia.

A Saint Demetrius, seated, half-drawing the sword from the sheath, his name engraved near his head, his face being of a very fierce late-empire appearance, continues the line of bas-reliefs embedded in the facade of the basilica as on a museum wall.

We now arrive at the central door, the large porch, whose arch cuts into the marble balustrade that sits above the other doors; it is, as it should be, richer and more ornate; besides the mass of columns in antique marble which support it and grant it importance, minor arches, two interior and the other exterior, strongly outline the arch with their curvature. These three arcs with sculpted ornamentation, pierced and cut with wonderful patience, consist of a bushy spiral of branches, foliage, flowers, fruits, birds, angels, saints, figurines and chimeras of all kinds; in the widest, the arabesques spring from the hands of two statues seated at each end of the arc.

The door is furnished with leaves of bronze, and studded with the faces of fantastic animals, its crowning glory being a niche above, with two gilded, trellised, and perforated shutters, in the form of a triptych or cabinet.

A Last Judgment, of large dimensions, occupies the top of the arch. The composition, said to be by Antonio Zanchi, and its execution in mosaic by Giovanni di Pietro ‘Lo Spagna’ dating from around 1680, was restored in 1838 (by Liborio Salandri and Lattanzio Querena) in accord with the old design. The delineation of Christ, which is somewhat reminiscent of that by Michelangelo in the Sistine, separates the virtuous and the sinners. He has near him his divine mother and his beloved disciple Saint John, who appear to intercede for the sinners, and leans against his cross which supports a respectfully-concerned angel. Other angels sound their trumpets with full cheeks, to wake the stubborn sleepers from their graves.

Above this porch, on the gallery which surrounds the main facade of the church, are placed the famous horses, which under Napoleon adorned the triumphal arch of the Carrousel, posed on antique pillars as their bases. Opinion is divided with regard to them: some claim them to be Roman works from the time of Nero, transported to Constantinople in the fourth century; others, claim them to be Greek works from the island of Chios, brought, by order of Theodosius in the fifth century, to that same city, where they adorned the racecourse (the Hippodrome); and yet others affirm that the horses are from the hand of Lysippus. What is certain is that they are ancient, and that, in the year 1205, Marino Zeno, who was the podesta in Constantinople for the Venetians, had them removed from the Hippodrome and brought to Venice. These horses, of life size, somewhat short in the neck, with manes cut short like that of the horses of the Parthenon, can be classified among the most beautiful relics of antiquity. They are truly historic and of rare quality; their stance indicates that they were harnessed to some triumphal quadriga. Their material is no less valuable than their form; they are said to be made of Corinthian bronze, whose greenish patina can be seen through a gilding of varnish faded by time.

The fourth porch offers in its lower part a similar design to the second. The summit of the arch is occupied by a mosaic representing the Doge, senators, and patricians of Venice gathering to honor the body of Saint Mark which is lying on a shrine and covered with a drape in brilliant blue; in the corner cluster a group of Turks, confused at having allowed such a treasure to be stolen. This mosaic, one of the most dazzling in tone, was executed in 1728, by Leopoldo del Pozzo, based on a drawing by Sebastiano Ricci. It is very beautiful. The senator in the Purple Robe has a wholly Titianesque air. In the spandrel between it and the large portal, we see a Saint George in Graeco-Byzantine style; on the other side an angel or an unknown saint.

The fifth porch is the most curious. Five small windows, with gilded trellises of varied design, fill the lower portion. Above, the four evangelical creatures in gilded bronze, the ox, the lion, the eagle, and the angel, as fantastic in form as Japanese chimeras, cast suspicious glances at each other, while over them a strange rider, on a mount that might be Pegasus or the pale horse of the Apocalypse, paws the ground between two gold rosettes. The capitals of the columns are also executed with a wilder, more archaic, more ornate taste than elsewhere.

Above the arch, a mosaic, the work of an unknown artist of the twelfth century, contains a painting of great interest, a view of the basilica, built to receive the relics of Saint Mark, as it was eight hundred years ago. The domes, of which the design only allows us to see three, and the porches of the facade have approximately the same form as today; the horses, recently arrived from Constantinople, are already in place; the main arch is occupied by a large Byzantine Christ with his Greek monogram, the others are filled with rosettes, fleurons and arabesques. The body of the saint, carried on the shoulders of prelates and bishops, enters, in profile, the church dedicated to him. A host of characters, groups of women clad, as one imagines the Greek empresses were, in long dresses studded with embroidery, rush to see the ceremony.

The line of disparate bas-reliefs, whose subjects I have identified, ends on this side with Heracles in command of the Erymanthian Boar which seems to threaten a small being, grotesquely posed, waist-deep in a barrel. Beneath this bas-relief are two lions rampant, and, a little lower down, an ancient figure, carved in the round, holds an amphora on his shoulder. This theme, undoubtedly arising by chance, was happily repeated in the rest of the building.

This row of porches which forms the first register of the facade is topped by a white marble balustrade; the second contains five arches, the middle one, much larger than the others, curving behind the horses of Lysippus, is glazed instead of carrying a mosaic, and is decorated with four ancient pillars.

Six turrets (aediculae or tabernacles), each composed of four columns forming an openwork niche which contains a statue of an evangelist, beneath a pinnacle encircled by a gilded crown and topped with a weather vane, separate these arches whose tympani are semi-circular, and whose ribs taper to an ogival point. The four subjects of the mosaics they contain represent the Ascension; the Resurrection; Jesus raising Adam, Eve, and the patriarchs from Limbo; and the Descent from the Cross; the mosaics having been created by Luigi Gaetano, according to the designs of Maffeo Verona, in 1617. In the spandrels are placed the naked figures of slaves, life-size and carrying, on their shoulders, urns and amphoras tilted as if they wished to pour the water taken from a fount into a basin; their hollow vessels are aimed towards the gutters, and thus the slaves play the role of gargoyles. They possess a wide variety of poses, and are superbly done.

At the ogival point of the large middle window, on a dark blue background strewn with stars, stands the lion of Saint Mark, gilded, haloed, wings outstretched, claws on an open Bible on which these words are inscribed: Pax tibi, Marce, evangelista meus (Peace be with you, Mark, my Evangelist). It looks both apocalyptic and awe-inspiring, gazing towards at the sea like a watchful dragon; above this symbolic representation of the Evangelist, Saint Mark, this time in human form, stands at the tip of the gable, seeming to receive the neighbouring statues’ homage. The five arches are festooned along their pointed ribs with large scrolls, foliage, and richly-carved acanthus florets whose efflorescence is an angel or holy figure in an attitude of adoration. On each of the minor gables rises a statue, Saint John, Saint George, Saint Theodore, and Saint Michael, wearing haloes in the shape of hats.

At each end of the balustrade, there are two masts painted red to which are attached banners on Sundays and feast days; at the corner of the guardrail, on the side of the Campanile, is planted a severed head, of blood-red porphyry.

The lateral facade, which overlooks the Piazzetta and abuts on the Doge’s Palace, deserves to be examined. If, despite all my care and desired accuracy, my description seems a little confusing, please do not blame me too greatly: it is difficult to describe in orderly fashion a hybrid building, as composite and disparate as Saint Mark’s. From the Porta della Carta created by Bartolomeo Bon, which leads to the Giants staircase in the courtyard of the Doge’s Palace, the basilica reveals a flank decorated with marble slabs and Classical, Byzantine, and Medieval bas-reliefs, birds, chimeras, interlaced carvings, and creatures of all kinds: lions, ferocious beasts chasing hares; and children, half-swallowed up by dragons that resemble the Milanese biscioni, and holding in their hands a cartouche whose inscription is almost erased.

One of the curiosities of this angle of the building are two porphyry figures, repeated again in exactly the same pose (now known now as the Four Tetrarchs). They represent warriors, wearing approximately the same costume as the crusaders on entering Constantinople, and sculpted in a completely primitive and barbaric way, like naive Gothic bas-reliefs only more so. These men, carved in porphyry, with their hands on the hilts of their swords, seem to be consulting about the enactment of some violent plan: I imagined them to be Harmodius and Aristogeiton preparing to strike the tyrant Hipparchus (in 512BC). This is the accepted opinion. The learned scholar Andreas Moustoxydis recognises in them the four Anemuria brothers, who conspired against Alexius Comnenus, Emperor of the East. They might well simply be the four sons of Aymon (see the anonymous Medieval tale). I am leaning towards this opinion. According to others, these four porphyry figures represent two pairs of Saracen thieves who, having conceived the project of stealing the treasures of Saint Mark’s, mutually poisoned each other, while aiming to seize the larger part.

It is on this side that two large pillars are planted, taken from the church of Saint Sabas, in St Jean d’Acre (the city of Acre), and covered with bizarre ornamentation, and inscriptions in rather crude Kufic characters the secret of which is not well understood. A little further, at the corner of the basilica, there is a large block of porphyry in the shape of a column section, with a base and a capital of white marble; a sort of pillory on which bankrupts were once exposed. This usage has fallen into disuse; but it is rare, however, for anyone to sit there, and the Venetians, so quick to settle on the first pedestal or staircase they come to, seem to avoid it.

A bronze door leading to the baptistery chapel occupies the lower part of the first arch; it has for transom a window with columns, with a pointed arch and quatrefoils; two brightly coloured enamel shields, one of which is charged with a cross, and a rosette pierced in fish-slice fashion, completing the decoration of this tympanum. A mosaic of Saint Vitus, and one of an Evangelist holding a pen and book, are painted within niches carved at the two lower points of the arch. A small pediment in the style of the Renaissance, and white marble slabs, engraved with a green cross, fill the void of the second porch. A red, embossed bench from Verona offers, at the base of this pure type of facade, a convenient seat for a lazy person or a dreamer who, with feet in the sun and head in the shade, according to the Zafari method (see Victor Hugo’s play ‘Ruy Blas’, scene III), thinks of nothing and thinks of everything, gazing, from the foot of the Campanile, at Sansovino’s Loggetta, or at the blue sea and the isle of San Giorgio Maggiore, beyond the end of the Piazzetta.

On the serpentine capitals which support this arch, crouch two monsters from the Apocalypse, those extravagant forms glimpsed by Saint John in his visions on the island of Patmos: one, which has a curved beak like an eagle, holds a little heifer her legs folded beneath her; the other, which is part lion and part griffin, sinks its nails into the body of a child laid before it. One of its claws seems to poke out the eye of its victim.

The corner is formed by a squat detached column, which carries a bundle of five columns on its broad capital. On the vault of this open portal, covered with plaques of varied marble, there is a mosaic eagle, holding a book between its talons.

At either side of the arch, at a higher level, beautifully carved statues of two cardinal virtues, are revealed: Fortitude, caressing her familiar lion which stands there like a contented hound, and Justice holding her sword, with the air of a Bradamante (see Boiardo’s and Ariosto’s epic poems of Orlando). The sacristan baptises one with the name of Venice, and the other with the name of the Queen of Sheba (see her speech in the Bible, I Kings 10:9 ‘therefore made he thee king, to do judgment and justice.’).

Malachite inlays, various enamels, two little mosaic angels unfolding the cloth that holds the divine imprint, a large barbarous Madonna presenting her son to the adoration of the faithful, and flanked by two lamps which are lit every evening; a bas-relief of peacocks spreading their tail, brought here perhaps from an ancient temple of Juno; a Saint Christopher loaded with his burden, capitals woven into the shapes of baskets, and charmingly capricious; these are the riches that this angle of the Basilica presents to pedestrians in the Piazzetta.

The Basilica’s other lateral side overlooks a small square, an extension of the Piazza. At the entrance to this square squat two red marble lions, first cousins to those of the Alhambra in the naive fantasy of their forms and the grotesque ferocity of their muzzles and manes; they have acquired a prodigious polish, for since time immemorial the little city urchins have spent their days clambering over them and employing them like acrobats’ horses. At the end rises the palace of the Patriarch of Venice, of recent construction, most gloomy to look at, if it were not lost in the shadow of St Mark’s; while the ancient church of San Basso has a side facade on the square.

This side of the Basilica is a little less ornate than the other: it is covered with medallions, mosaics and enamels, cartouches, arabesques from all times and all countries, birds, peacocks, and oddly-shaped eagles like heraldic alerions and martlets. The lion of Saint Mark also plays its role in this symbolic menagerie: the hollow of the porches is filled, either by small windows surrounded by palms and arabesques, or by inlays of Classical or Byzantine fragments; in the medallions men and animals struggle together. If one looks closely, one may find a sacrificial Mithraic bull struck in the neck by the priest, for no religion is missing from this naive pantheist temple. Indeed, here is Ceres, seeking her daughter, a burning pine-branch in each hand for a torch, mounted on a chariot drawn by two rearing dragons. She looks like a Hindu idol, so archaic is the style, recalling the sculptures of Persepolis. It forms a strange pendant to Abraham sacrificing Isaac in bas-relief, which must date back to the earliest times of Christian art.