Théophile Gautier

Travels in Italy (Voyage en Italie, 1850)

Parts I to V - Geneva to Milan

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction.

- Travels in Northern Italy.

- Part I: Geneva – Plainpalais – A Herculean Acrobat.

- Part II: Lake Geneva (Lake Léman) – Brig – The Mountains.

- Part III: Simplon – Domodossola – Luciano Zane.

- Part IV: Lake Maggiore – Sesto Calende – Milan.

- Part V: Milan – The Duomo – The Daytime Theatre.

Translator’s Introduction

Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) was born in Tarbes, in the Hautes-Pyrénées region of south-west France, his family moving to Paris in 1814. He was a friend, at school, of the poet Gérard de Nerval, who introduced him to Victor Hugo. Gautier contributed to various journals, including La Presse, throughout his life, which offered opportunities for travel in Spain, Algeria, Italy, Russia, and Egypt. He was a devotee of the ballet, writing a number of scenarios including that of Giselle. At the time of the 1848 Revolution, he expressed strong support for the ideals of the second Republic, a support which he maintained for the rest of his life.

A successor to the first wave of Romantic writers, including Chateaubriand and Lamartine, he directed the Revue de Paris from 1851 to 1856, worked as a journalist for La Presse and Le Moniteur universel, and in 1856 became editor of L’Artiste, in which he published numerous editorials asserting his doctrine of ‘Art for art’s sake’. Saint-Beuve secured him critical acclaim; he became chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1862, and in 1868 was granted the sinecure of librarian to Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, a cousin of Napoleon III, having been introduced to her salon.

Gautier remained in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and the aftermath of the 1871 Commune, dying of heart disease at the age of sixty-one in 1872.

Though ostensibly a Romantic poet, Gautier may be seen as a forerunner to, or point of reference for, a number of divergent poetic movements including Symbolism and Modernism.

His Voyage en Italie is an account of his travels predominantly in Northern Italy, since Rome and the south are absent, and Florence is treated in brief only in the last section. The work centres on his account of Venice, which he claimed as one of the three cities of his dreams, namely Granada, Venice and Cairo.

This enhanced translation has been designed to offer maximum compatibility with current search engines. Among other modifications, the proper names of people and places, and the titles given to works of art, have been fully researched, modernised, and expanded; comments in parentheses have been added here and there to provide a reference, or clarify meaning; and minor typographic or factual errors, for example incorrect attributions and dates, in the original text, have been eliminated from this new translation.

Travels in Northern Italy

Part I: Geneva – Plainpalais – A Herculean Acrobat

I fear that our first steps in a foreign country were marked by an act of paganism, a libation to the rising sun! Catholic Italy which understands the Greek and Roman gods so well will forgive us, though strict Geneva will perhaps consider us a little too self-indulgent. At the crack of dawn, we drank a bottle of Arbois wine, bought while passing through Poligny, a pretty town at the foot of the high Jurassic wall one must cross on leaving France. Phoebo nascenti (Phoebus was born)! His first rays had revealed to us, suddenly, below the last mountain ridge, Lake Geneva, several patches of which glimmered through the silvery morning mist.

The road descended in several twists and turns, each bend forever revealing a new and charming perspective.

Breaks in the mist allowed us to divine, as through perforated gauze, the distant peaks of the Swiss Alps, and the lake itself, as big as a small sea, over which the white sails of various vessels floated, in the early morning, like doves’ feathers fallen from the nest.

We passed through Nyon, and already many a significant detail gave warning that one was no longer in France: pieces of wood shaped like rounded scales, or like tiles whose colour they almost share, cover the houses; the gables terminate in tin globes; the shutters and doors are made of boards laid crosswise and not lengthwise, as in France; red there replaces the green hue so dear to Jean-Jaques Rousseau’s enthusiastic grocers; Swiss French began to appear on the signage, the names having been previously designated in German or Italian.

The road, as we progressed, ran alongside the lake, whose transparent water dies on the pebbles in a regular motion which is sometimes augmented by the eddy from some steamboat decked out in the colours of the Swiss Confederation, heading for Villeneuve or Lausanne. On the opposite side of the road, were the mountains we had just descended, over whose flanks the clouds slid like smoke from shepherds’ fires. A large number of charabancs, light carriages where folk sit back-to-back or facing sideways, drawn by ponies or large donkeys, crisscrossed the dust. Villas and cottages multiplied, revealing beneath the shade of tall trees their tubs of flowers, their terraces, and brick walls: one feels one is approaching a city of some importance.

The idea of Madame de Staël, with her long black eyebrows and yellow turban, and her high waisted-dress in the Empire fashion, troubled us greatly while traversing Coppet. Although we knew she had been dead for a considerable while, we were forever expecting to see her beneath the columned peristyle of some villa, with Schlegel or Benjamin Constant at her side; however, we failed to do so. Ghosts never willingly risk themselves in broad daylight; they are too coy for that.

The mist had completely dissipated, and the mountain summits shone beyond the lake like gauze laminated with silver; Mont Blanc dominated the group in cold and serene majesty, beneath a diadem of snow no summer can melt.

The movement of carriages, carts, and pedestrians became more frequent; we were only a few hundred yards from Geneva. A childish idea, that not even lengthy travels can wholly dissipate, still leads one to imagine cities according to the products that render them famous: thus, Brussels is a giant cabbage patch, Ostend an oyster bed, Strasbourg a pâté de foie gras, Nérac a terrine, Nuremberg a toybox, and Geneva a watch, set with four rubies. We imagined to ourselves a vast intricate work of timekeeping, with toothed wheels, cylinders, springs, escapements, the whole mechanism ticking, and endlessly rotating back and forth; we imagined the houses, if there were any, as double-sided cases, in gold and silver, their doors opening with watch-keys. As to the suburbs, we accepted the houses there might be made of copper or steel. Instead of windows, we conceived of an infinity of dials all marking different times. Ah well! That dream vanished like many another; Geneva, we are forced to admit, looks not at all like a timepiece, which is unfortunate!

When we entered the place, a little slowly it seemed to us for so austere, republican, and Calvinist a city, we received, in exchange for our passports, a facetious notice, commencing like the comic strips involving Monsieur Crépin and Monsieur Jabot, as drawn by that witty caricaturist Rodolphe Töpffer, with the humorous recommendation: See below.... a host of formalities to complete.

Geneva has the serious, somewhat stiff, appearance, of Protestant cities. The houses there are tall, and uniform; straight lines, and right angles reign everywhere; everything is fashioned in squares and rectangles. Curves and ellipses are prohibited as too sensual and voluptuous: grey is welcomed everywhere, on walls and in clothing. Hairstyles, in a moment, turn into Quaker hats; one felt there must be a vast number of Bibles in the city, and very few paintings.

The only things that give Geneva a fantastic air are the metal chimneys. One could not imagine anything more bizarre and capricious. You know those acrobats that the English call acropedestrians who, on their backs with their legs in the air, juggle a wooden bar, or a pair of children covered in sequins. Imagine all the acropedestrians in the world rehearsing their acts on the roofs of Geneva, but in the form of bifurcated contorted, desperately-struggling, chimney pipes; their contortions must have as their cause the numerous gusts of wind that descend from the mountains, and rush through the valley. Perhaps the Piedmontese chimney-sweeps, before first travelling through France, perfected their talents in Geneva, and worked triumphs of chimney-sweeping there. The pipes are made of tin, freshly-polished and shining brightly in the sunlight. I spoke earlier about acropedestrians doing their job. Equally a routed army of knights, thrown from their steeds, their legs bent in the air, seems a good comparison also; but let us leave the chimney-pipes there.

It is strange how a great name seems to populate a city. That of Jean-Jacques Rousseau pursued us the whole time that we were in Geneva. It is difficult to comprehend that the body of an immortal spirit has disappeared, that the form which enclosed sublime thoughts has vanished without hope of return: and we were distressed not to meet on some street corner the author of La Nouvelle Héloïse, in his fur hat and Armenian clothes, with a worried and thoughtful air, his expression sad and gentle, looking to see if his dog was following him and not betraying him like humankind.

I shall say nothing regarding Saint-Pierre Cathedral, the city’s main place of worship: Protestant architecture consists of four walls brightened a little by mouse-grey and canary-yellow; as such it is too plain for my taste, since, in matters of art, I am Catholic, Apostolic and Roman.

Nonetheless, Geneva, somewhat cold and stiff though it may be, holds an item of interest sufficient to send Eugène Isabey and Eugène Cicéri, William Wyld, Émile Lessore and Hippolyte Ballue, into transports of joy, and fill the office of public works with despair. I mean a group of wooden buildings on the edge of the Rhône, at the point where it exits from the lake to head for France. I recommend, it in all conscience, to the watercolourists, who will thank us for the gift; nothing involved is straight or level; the various floors advance and retreat, the rooms project outwards in carved wooden lattice-work. The whole is an incredible mixture of half-timbering, planks, joists, nailed slats, trellises, and chicken-coop style balconies: all worm-eaten, cracked, blackened, mildewed, veined, bleared, frowning, and derelict, covered in leprous stains and calluses to delight a Richard Parkes Bonnington, or an Alexander-Gabriel Decamps; the windows, broken at random, and half-blocked by collapsed shards of glass, draped with garlands of tripe and pig-bladders, sweet-peas and nasturtiums, belonging to these pleasant dwellings; and paintwork in vinous, and blood-stained tones, part-effaced by the rain, completes the fierce and truculent appearance of these perilous hovels, whose reflection the Rhône, which passes beneath, with its dark-blue flow, obscures with foam.

Opposite the shacks are tanneries which cleanse calfskins, suspended from beams, in the current; they appear like drowned victims. These, if you wished to consider the matter from a Romantic and nocturnal point of view, might be travellers lured to the sinister huts we have just described by some pretty Maguelonne, slaughtered by the assassin Saltabadil (characters in Victor Hugo’s play ‘Le roi s’amuse’), and hurled into the river, from one of those upper windows seemingly dripping with blood.

Let us cleanse ourselves of these bloodthirsty images in the lake. Geneva is all Lake Geneva. It is impossible, there, to avert one’s eyes or ignore its shores: every window strives to gaze towards it, and the houses stand on tiptoe, seeking to glimpse it over the shoulders of buildings more favourably sited.

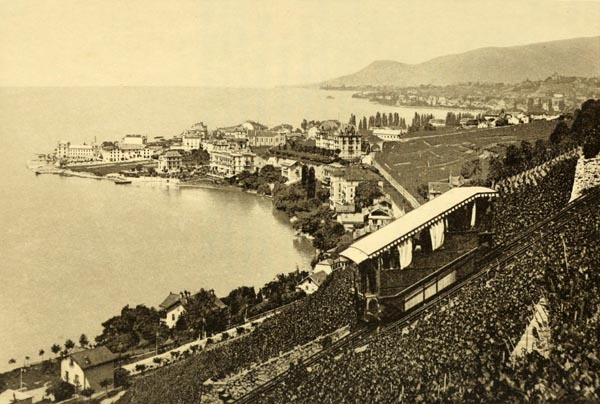

Lake of Geneva - Montreux and the Righi Railway

A flotilla of rowing boats, and vessels under canvas, with or without awnings, wait, near the mole where the steamboats stop, to address the whims of walkers and travellers.

Nothing is more charming than wandering over this blue tablecloth, as transparent as the Mediterranean, bordered by villas that bathe their feet in the water, and framed by layered mountains blue with distance. Mont Salève, the Dent de Morcles, and old Mont Blanc, which seems sprinkled with dust like that of Carrara marble, embroider the horizon on the Swiss side of the lake, while on the French side the last foothills of the Jura Mountains display their undulations. Fishing boats, their raised sails in the shape of open scissors, wander nonchalantly, trailing their lines or nets. Canoes, skiffs, and boats of all kinds, crewed by amateur sailors, flit from one bank to the other, in large enough numbers to make a lively tableau, but sparsely enough that they fail to overcrowd the scene.

Nonetheless, the lake, however calm and clear it may be, is not always free from danger. Its gusts sometimes mimic gales, and accidents occur. I was told of a jeweller from Paris, rich, retired from business, who had drowned, recently, along with his friend, the yacht he was sailing having been taken aback, and the boat having capsized. One of the bodies had been found, but not the other, though such clear water seems incapable of hiding its secrets. Skilled divers, descending with the aid of a stone attached to a thin cord which they severed when they wished to ascend, had searched the lake to a depth of five hundred feet, but in vain. Our boatman told us that the jeweller’s corpse must have been carried away by the flow of the Rhône, which traverses Lake Geneva, or dissected by crayfish on the lake-bed, which had prevented the corpse from returning to the surface. This story spoiled the lake a little for us, and we chose to avoid eating crayfish, under any circumstances, during our stay in Geneva.

It is our custom, when travelling, to read the billboards and notices, posted freely, and always on display to the passer-by. We viewed, on a notice giving the reports of various convicts, an idiomatic word peculiar to Geneva: it is the word grisallant used as an epithet instead of grisonnant, for greying eyebrows, in describing the features of some criminal or other. Our contemplation of the wall taught us that there was at Plainpalais, which is Geneva’s Champs-Élysées, a fairground suitably supplied with wooden horses, wheels of fortune, and acrobats. The poster, displayed by Karl Knie of Vienna, which announced a number of acrobatic performances, particularly appealed to me. Rope-dancing, which should have its own theatre in Paris, is a most interesting attraction, and very graceful in execution, and we never understood why the enthusiasm which greets ballet-dancers like Marie Taglioni, Fanny Elssler, Carlotta Grisi, and Fanny Cerrito, disdains tightrope-dancers, who are just as light of step, and whose art requires more courage, being more dangerous.

It is on the Plainpalais side of the lake that the aristocratic districts are located. The neighbourhoods where the seditious masses live, the suburbs of Saint-Marceau and Saint-Antoine, sprawl at the other end of the city, on the other side of the Rhône bridges.

A fairly eager but calm, and compact crowd, was heading towards the city gates. In this considerable gathering of people, we noted nothing particular by way of costume. The fashions were those of France, though somewhat out of date, and provincial; we noted a minor difference, a few of the men’s straw hats with black ribbons and braids of the same colour, and immense brims to the hats worn by women, brims that dip before and behind, so as to hide half of the neck, and the facial features.

The women themselves give to their French airs a North-American or Germanic twist, easier to view than to describe, and which derives from their religion. A Protestant neither sits nor walks like a Catholic, and their clothes hang differently on them. Their beauty, also, is different; they have a particularly penetrating look, though restrained, like a priest’s, a cool smile, a deliberate gentleness of physiognomy, a reticent modesty, like that of a governess or a clergyman’s daughter.

Herr Knie occupied a canvas enclosure, open to the heavens, and lit by a dozen lamps whose fiery tongues, stirred by the evening, breeze sometimes licked too ardently at their wooden supports.

Karl Knie, let me say at once, is a great artist, and impressed us deeply. No tightrope, stiff or slack, has supported any to compare. Perhaps you imagine a young man, slight, slender, an aerial human shuttlecock bouncing acrobatically up and down on its racket! You would be quite wrong.

Attention! The orchestra announces the performance with a triumphant fanfare; the bass-drum thunders, the double-bass hums, the cymbals quiver, the trombone bellows, the clarinet chirps, the fife squeaks; the musicians, employing the whole strength of their arms and lungs, extract from their instruments all the sonority they can; everything suggests the entry of a superior artist, the star of the troupe; a profound silence settles on the audience.

Onto the boxlike platform which serves as a stage for his acrobatics, bursts forth, impetuously, a large fellow, shaped like Hercules. He advances with an air of resolution towards the frame which supports the taut cable; he clings to it, with a strong grip, and with a leap stands upright, beside the cloth adorned with tinsel which decorates the X-shaped bars, from which the dancer departs and where he will come to rest.

Never, in Swiss stained-glass windows of the sixteenth century, or those woodcuts of Maximilian I’s triumph created by Albrecht Dürer, have I seen a lansquenet (mercenary soldier) or a reiter (cavalryman) of a more masterful and more formidable turn. From his brimmed hat, similar to that of Albrecht Gessler, escaped three bold and dishevelled feathers, more contorted than the heraldic lambrequins (mantling) of a burgrave’s coat of arms; his doublet was slashed in the Spanish-style, his belt clasped his stomach with some difficulty, and surely needed to be encircled with iron bands like Henri, the prince’s servant, in the tale of the Frog Prince, so as not to burst. His collar rose up to his skull in three large folds at the nape of the neck, like a mastiff’s ruff, bearing atop it a square, bold, fierce and jovial head, the head of one of Herod’s soldiers, an executioner on Calvary, or, if such comparisons are too biblical for you, of heroes of the Nibelungenlied in the illustrations by Peter von Cornelius. His enormous legs, revealing knots of clenched muscles beneath his white costume, looked like oaks from the Hyrcanian Forest clad in trousers; rolling his arms with every movement, he exhibited biceps like the cannonballs of ’48.

A balance-pole was thrown to this Polyphemus of the tightrope, probably shaped from a young pine torn from the mountain-side, and he began to leap about, with incredible grace, lightness and ease on the cable, that we feared might break at any moment. Picture to yourself the opera-singer Luigi Lablache on a wire wrought of brass.

This fellow, beside whom Hercules, Samson, Goliath, and Milo of Crotona would have appeared timid, soon disdained such facile exercises; he settled himself on his rope with chairs and a table, and ate a meal shared by a clown, and, to express his delight at the dessert, danced a gavotte with a child of between twelve and fifteen years old hanging from each foot. This exhibition of athletic strength, to augment a performance which seemed to require only flexibility and lightness, produced a singular effect.

His Cyclopean acrobatics were followed by a polka danced on parallel ropes, by two sisters of approximately the same size, with a good deal of grace, correctness, and precision. One of the two was really charming. She had a delicate, gentle look, and an intriguing smorfia (grimace) in place of the dancer’s obligatory smile. She appeared in a pair of costumes: first in a black bodice and white skirt studded with stars, and then in a yellow petticoat, with a red bodice trimmed with little teeth which pierced our hearts. After the polka, she danced a solo on the rope, a classic series of steps, bending back and forth, as on the Opéra stage. As she finished, by striking a pose, arms stretched out, body leaning over the void, executing a relevé, a voice, from a corner of the room, called out: ‘Higher, that’s not it!’ The dancer understood, blushed slightly, and with a smile bent a little, and without losing her balance made the bright white of her tights flicker beneath the gauze.

Who had uttered this exclamation? Was it some university student, a senior (a ‘bemoostes Haus’ or ‘maison mossue’) from Heidelberg, or a freshman (a ‘Fuchs’ or ‘renard’) from Jena, in a white cap, his frock coat clasped at the waist by a leather belt, or a French rapin on his way to Italy in search of the naive in art, or a plastique of the Olympian school, or a transcendental Hegelian? It’s hard to decide, and I leave the matter unresolved.

After the rope-dance, the girl performed the egg-dance; a certain number of eggs are placed on the ground in a chessboard pattern, and the dancer passes along the little alleys formed by the rows of eggs, blindfold, and without the feet touching any of the obstacles. The slightest clumsiness in doing so would deliver an omelette: Mignon, without doubt, could not have delivered his tour de force before Wilhelm Meister more adroitly than the young girl from Knie’s troupe before her Geneva public, and Goethe could not have had a more charming model from which to trace Mignon’s delightful face. I seemed to hear, fluttering on her lips, that melancholy song:

Kennst du das Land, wo die Citronen blühn?

Do you know the land where the lemon-trees grow?

The clown, Auriol, thwarted in his ambitions, displayed an aura of nostalgia amidst this Austrian caravan. He was French, from Nancy like Jacques Callot. Let us not forget, for one must be fair to all, a valet in red clothes, the best lackey that a trader in Swiss vulneraries or herbal teas could dream of. Oh, how inimitable his manner when stretching out a leg or straightening his back! Receive, unknown talent, the humble gift of admiration from a critic whose praise has pleased those more celebrated than yourself!

The show ended, everyone rushed off, in haste, for the city gate, which closed at a certain hour, after which time the gatekeeper required a small donation before opening it once more.

Part II: Lake Geneva (Lake Léman) – Brig – The Mountains

Geneva had given us all the pleasures that a Protestant Sunday permits; a voyage on the lake, a wonderful sunset over Mont Blanc, which turned pink like the Sierra Nevada above Granada, viewed at evening from the salon of the Alameda, and a charming fairground performance beneath beautiful trees and a starry sky; all that remained for us to do was leave.

We had initially wanted to make the trip in a four-wheeler, if only to see if the vetturino (carriage-driver) described in La Chasse de Castre (by Alexandre Dumas) was a true portrait; but, fortunately, such an extravagant price was demanded of us, we having, without doubt, been taken for Englishmen or Russian princes, that the suggestion lapsed, and we realised the benefit in not being dragged along in an antediluvian sedan by horses worthy of the old fiacres of Paris. The speed and convenience of the journey amply compensated us for this offence against local colour.

A diligence (stagecoach) was to take us to Milan over the Simplon Pass; not the same one, because we were required to change horses in nigh-on every territory we crossed, the government having a monopoly on transportation; though we had no other involvement but agreeing to transfer from a Genevan coach to a Savoyard coach, which would hand us over to a Swiss coach, which would deliver us to a Piedmontese car, which would turn us over to an Austrian mail-coach. Believe not that I intend the least comic exaggeration here; this shower of diligences is the truth itself: it is always reality that is unbelievable.

Leaving Geneva, we travelled to Cologny, from where one enjoys an admirable view. Geneva is visible at the end of the lake; the Alps and Mont Blanc rise to the left (looking towards Geneva), while to the right one sees the distant Jura mountains. Near Cologny there is a country-house set in a most picturesque location, which belonged to Théodore Tronchin, the doctor so celebrated in the eighteenth century. It is still occupied by a member of that illustrious doctor’s family.

The first Savoyard village one encounters is Douvain or Dovenia. We imagined seeing a population of young Savoyards, chimney-sweep’s brush in hand, clad in knee pads, armbands and leather-bottomed trousers, as portrayed in Voltaire’s verse, Joseph Hornung’s paintings, and the repertoire of François Dominique Séraphin’s shadow-theatre. It seemed to us that every chimney-pot was obliged to reveal a soot-smeared face, with bright eyes and gleaming teeth, its lips uttering the cry known to all little children: ‘Ramoni, ramona, chimneys cleaned of soot and tar!’

Not only were the Savoyards, who call themselves Savoisiens so as not to be confused with Auvergnats, not occupied in chimney-sweeping, they were celebrating a feast-day of some kind, and were shooting at a bird perched atop a fifty-foot mast. Every successful shot was greeted by fanfares and drum-rolls.

After Douvain, one loses sight of the lake, and crosses well-cultivated land with a fertile aspect. Fields of maize with its pretty tufted ears, terraced vineyards supported by low walls, and a few fig trees with large leaves foreshadow one’s approach to Italy.

Soon one encounters the lake again and follows its contours. One traverses Thonon-les Bains, and Évian, where we halted for a few moments, and which is one of the most favourable points for embracing a general view of Lake Geneva.

Never did a theatre-designer, with the exception of Charles Séchan, Jules Diéterle, Édouard Desléchin, or Joseph Thierry in collaboration with Charles-Antoine Cambon, create scenery to more wondrous effect than Évian has by the mere actions of Nature.

From the height of a terrace shaded by tall trees, one views below, in the depths, if you lean against the parapet, the treetops and disorderly roofs of wooden or flat stone tiles in the lower town. This foreground, in a warm, vigorous key, strikes a tone which provides a most excellent foil for the rest; the view terminates in vessels with tapered bows, salmon-coloured masts, and wide reefed yards, drawn up on the shore after their travels. The middle-ground is provided by the lake, and the background by the Swiss mountains, which extend twelve leagues or so.

These are the rough outlines of the picture; but what the brush would perhaps be even more powerless to render than the pen is the lake’s colour. The most beautiful summer sky is certainly less pure, less transparent. Rock-crystal and diamond are no clearer than this virgin water flowing from the neighbouring glaciers. Distance, the greater or lesser depth, and the play of light grant it vaporous hues, ideal in nature, impossible in effect, which seem to belong to another planet; the cobalt, outremer, sapphire, turquoise, or azure of the most beautiful blue eyes, are of earthly tones by comparison. Various reflections from a kingfisher’s wings, or the gleaming mother-of-pearl of various shells, alone, may give some idea of them, or even certain of those blue Elysian distances in Jan Breughel the Younger’s depictions of Paradise.

One wonders if it is water, sky, or the azure mist of a dream that one sees before one: the air, the waves and the earth reflect the light and mingle together in the strangest way. Often a boat, trailing its dark blue shadow, alone gives warning that what you had taken for a tract of sky is a portion of the lake. Mountains take on unimaginable shades, silvery and pearl greys; tints of rose, hydrangea, and lilac; and ash blues like Paolo Veronese’ ceilings. Here and there a few white dots gleam: they are Lausanne, Vevey, Villeneuve. The reflection of the mountains shadowing the water is so fine in tone, so transparent, that one loses one’s sense of objectivity; it is necessary, in order to regain it, to locate the slight shiver of silver with which the lake fringes its banks. Above the first mountain chain, the Dent de Morcles shows its two whitish pinnacles. This is where the Rhône enters the lake, the Rhône which we would follow as far as Brig.

At Saint-Gingolph, we said our farewells to Lake Geneva, whose vast riot of azure ceased for us there by terminating on the outskirts of Villeneuve. The whole day had passed like a dream, in a bath of tender blue light, a mirage, a Fata Morgana. How enchanting its harmony, how temperate its Attic grace, how ineffable its suavity, chaste its voluptuousness, mysterious its caress; how the sweetness of nature enveloped the soul!

This journey along the lake-shore reminded me of that day of celestial intoxication spent near Granada, on the heights of Mulhacen, on the same date, ten years earlier, amidst an ocean of azure light and snow.

Turning south from Lake Geneva, the road remains picturesque, though nothing can replace the effect of that immense mirror of sky mingled with water.

We followed a route lined with beautiful trees, whose freshness was maintained by the valley’s shade. The cliffs rose steeply on each side to prodigious heights: one of them seemed as if it terminated in a fortress, complete with a cluster of turrets, crenelated ramparts, keep, and pepper-pot gate-towers. The snow, silvering the projections and cornices of the rock, rendered the illusion even more complete: the imagination appointed it no other than the abode of that Job whom Victor Hugo so praised.

The Rhône flows along the valley bottom, sometimes near, sometimes further away, but always yellow and turbulent, rolling stones and sand along and often shifting in its bed like an anxious patient. The river has to pass through the filter of Lake Geneva before it can acquire that deep blue which characterises it on departing the city; because, as the great poet whom we cited a moment ago declared, the Rhône is blue like the Mediterranean towards which it races, and the Rhine green like the Ocean towards which it strolls. It is unfortunate that this charming landscape is plagued by goitres. At every turn one encounters women, often very pretty, in their traditional little hat, topped and bordered with ribbons set like little gun barrels, who are afflicted with this unpleasant infirmity. A goitre looks like that membranous pouch beneath a pelican’s beak. Some are huge. Is it the shade from the mountains, the rawness of the icy water, which causes this sad deformity? That we never really discovered. Women, especially old women are more prone to it than men: nothing is more afflicting. A sufferer with a bent head, and goitred neck, stopped near our coach, grunting and wheezing. A sad picture! The disease is enough to turn a man into an animal, a creature of mere instinct.

We dined at Saint-Maurice, on the banks of the Rhône, a large fortified town of rather forbidding appearance. On the walls of the hotel, hung lithographs representing Switzerland’s illustrious military men: General Guillaume-Henri Dufour surrounded by his staff, Hussy of Aargau, Eschmann, Frey-Hérosé, Pfonder of Lindenfrey, Zimmerli and others. There were also portraits of Ulrich Ochsenbein, president of the Federal Diet in 1847, and of Jakob Robert Steiger. We note this because hotel-adornments everywhere are usually purchased from the Rue des Maçons-Sorbonne, in Paris, and represent merely the four seasons, or the four corners of the world.

At Saint-Maurice, we were inserted into a ridiculous coupé in which one could neither stand upright nor bent, nor lie down, nor sit, so ingenious was its construction. This berlingot jolted us to Martigny, where we were taken up by a diligence. The night was foggy and icy, and we could barely discern the vast confused shapes of the mountains; half-awake we traversed Sion and, as daylight dawned, at the end of a valley dissected by torrents and rendered humid by marshland, there rose the bell towers and buildings of Brig, crowned with large tin globes, which gave it the air of a more modestly-sized Kremlin. Here the road to Simplon begins. Only a mountain ridge now separated us from that Italy whose name is so powerful, according to Heinrich Heine, that it makes even the philistines of Berlin sing ‘Tirily’.

The Simplon route we were about to follow is a marvel of human genius. Napoleon, recalling the difficulty Hannibal must have had in melting the Alps with vinegar, as we are told, in all seriousness, by the historians, wished to spare the returning conquerors of Italy such labour, and had them create this miraculous path in only three years. The vinegar of ancient times must have been of incredible strength; since sixteen million kilos of powder, and ten thousand men, were scarcely enough to carve the imperceptible strip called a road in the side of this savage mountain.

The land slopes gently upwards, between the mountains on either side, so close one might believe one could touch them with a finger though they are quite far apart; but in Alpine regions, the perpendicularity of the terrain constantly deceives with regard to distance, by the perpendicularity of its planes. The range we left behind was covered in snow; it is an offshoot of the Swiss Alps. On the flanks, which seem inaccessible, even to the feet of mountain-goats, villages are suspended, who knows how, villages betrayed by their bell-towers sometimes the sole visible evidence of their presence. Chalets, lost amidst the mountains, with wooden awnings, and roofs loaded with stones for fear the wind may rip them away, suddenly reveal the unexpected presence of humankind; this is where, blocked in by ice and avalanches, the shepherds spend their winters, far from human commerce. Where you think only to find eagles and chamois, you meet reapers and mowers: agriculture rising to dizzying heights; we saw a woman baling hay at the edge of a fifteen-hundred-foot precipice, on a meadow sloping like a roof, with a scattering of cows whose bells could be heard ringing.

Brig, on the floor of the valley, seemed no more than one of those toy-sets from Germany representing a village carved in wood. Its proportions were the same; the tin globes shone like balls of glitter in the morning sunlight. The Rhône seemed little more than a yellow thread. To the right of the road the mountainous horizon stretched as far as the eye could see, the peaks, their summits lifting one above another, forming a sublime panorama. A few snowy spires of Mont Blanc rose from the depths of this magnificent chaos. On the left, were forests with large firs of surprising vigour and beauty: the fir tree forms the grass of these mountains. It is to them as a covering of grass is to a meadow. The steep escarpment which appears clothed in a velvety manner, here and there, with patches of moss, is in fact cloaked in fir and larch trees sixty feet high. Those ‘blades of grass’ would make fine masts for ships; that skin-crawling cleft in the mountainside is a valley which could hide a village in its fold, and often does; this immobile whitish network, which one might take for a vein of snow, is a fierce torrent which descends swiftly, amidst a dreadful thunderous sound, unheard by us.

Nothing is more beautiful or more pleasantly grandiose than the commencement of the road to Simplon from Geneva; immensity fails to exclude charm; a certain voluptuous grace covers those colossal undulations; the fir trees are such a fresh green, so mysterious, so tender in its intensity; their attitude is so elegant, so open, so slender; their arms extend their sleeves of greenery towards you in so amiable a manner; their silvery trunks imitate columns so well; they cling so skilfully, their roots clasping the edge of some abyss or sheer wall; the streams babble so sweetly in their silvery voices beside you, among the stones and aquatic plants, the distant ones revealing such attractive blue tones; the precipices are so inviting, that I felt in a state of extraordinary exaltation, and that I could gladly launch myself, head first, into some pretty chasm.

For some time, we skirted a delightful abyss, at the bottom of which the Saltina performs foamy antics, twisting and turning in the most picturesque way. The forests of fir trees, in process of exploitation, offer a singular appearance. The tree-trunks, severed a few feet from the ground, have the appearance of the columns planted in Turkish cemeteries, and thus we wondered with astonishment at the vast number of Osmanlis buried on a Swiss mountain. Where such harvesting is recent, the cuts made by the axe, present light salmon tones which closely approach the colour of human flesh; they look like wounds caused to the bodies of those dryads the ancients thought inhabited trees. The fallen section then takes on an interesting and painful air; sometimes the ground slips from beneath its feet and it slips halfway into a chasm, held back, in its fall, by the arms of a few more firmly-rooted friends.

Here and there, in the distance, refuge-huts, marked with a numeral, and eight in number if my memory does not deceive me, awaited those travellers surprised by a storm, melting snow or an avalanche. In such places, so solitary, so seemingly lost, human forethought accompanies you, everywhere protecting you. When you think you are alone, between nature and God, drowned in the vast ocean of immensity, a roadman who humbly breaks stones and busies himself with filling the rut that might cause your vehicle to overturn, revives the general feeling of human solidarity. In deepest isolation, one of your brothers is laboring on your behalf; a herd of goats, alarmed, climb the sheer cliffs formed by the rock, jumping from outcrop to outcrop with incredible agility, despite the cries of the goatherd recalling them; a patch of cultivated land appears suddenly in an unlikely place; a cluster of dwellings indicates that here folk love and hate, joy and suffer, live and die, as on the plain and in the city; isolated cabins signal the presence of hearts with the strength to endure the spectacle of immensity without being overwhelmed, and to remain face to face with God, beyond all human distractions.

Arriving at a place where the valley is cut by a deep trough, where all the streams and torrents that flow from the mountain traverse the road through underground conduits, we crossed a bridge whose abutments were of a prodigious height, then negotiated a bend, and began to climb the further ridge.

This was where the relay station was located, the buildings of its two sections, linked together by a covered gallery in the manner of a bridge.

The mountain to the east which had been continuously visible in the background, hid its snowy head behind the horizon. Ahead now, to the south, was the Fletschhorn with its icy cap from which torrents filtered, while behind us, to the north, rose the Schinhorn, somewhat further off, hooded with clouds. The fir-trees were sparser, the vegetation noticeably poorer. However, bold plants ever keep company with humankind, reviving the feeling of life in places where all might seem dead. Rhododendrons display their perennial greenery and beautiful flowers, which they call, there, Alpine roses: blue gentians, saxifrages, moss campions with their pink flowers, forget-me-nots like little turquoise stars bravely climb the mountain beside one, profiting from a trickle of water, a handful of earth in the hollow of a rock, a crack in the shale, the slightest favourable accident: humankind, itself, refuses to yield. We build even amidst the ice, at risk of being swept away by water and snow; our self-esteem it seems is involved in our inhabiting uninhabitable places.

We had almost reached the highest point of the road, something like six thousand feet above sea level. There was nothing now between us and the sky except the Fletschhorn glacier, from which four perpendicular torrents fell, four downpours of melted mire and foam. We could see the first of these torrents, distinctly, springing as it did from the corner of the glacier through an arch of green crystal; it was strange and beautiful to see this soapy, earthy, water flowing from the summit of the peak, and passing beneath the road, covered by a vaulted gallery lined with stalactites, appearing, now, like a natural cave; various openings allow you to see the cataract below, as it falls, thundering, into the abyss. The other three torrents roared and fled by in silvery gushes, amidst snowy foam, with unimaginable noise and turbulence. The spectacle was wholly Romantic in its savagery. The Fletschhorn, at this height, displays only bare earth, rocks, ice, snow, and torrential streams; the skin of the planet appears in all its nakedness, which some compassionate cloud hides from time to time in its cotton mantle.

From there the path began to descend. We left the Swiss side of the ridge for the Italian side. A strange thing occurred! As soon as we had crossed the ridge which separates the two regions, we were struck by an extreme difference in temperature. On the Swiss side, it was charming, gentle, warm, bright weather; on the Italian slopes an icy breeze was blowing, and great clouds like fog passed over us and enveloped us: the cold was excruciating, primarily due to the acute contrast. The undercoat and topcoat we never failed to carry with us when we travelled in the South, scarcely sufficed to keep our teeth from chattering.

The ancient Simplon hospice could be seen at a lower level, to the right of the road leading from Switzerland; it is a yellowish building, topped with a fairly high bell-tower. The new hospice, much larger, is on the left; it receives travellers in distress or merely exhausted, and provides them with the care they need free of charge. Rich people donate something to the Church. As we passed the hospice, two priests emerged, one young the other old but vigorous, who were crossing from the Italian side; they both wore hats with rolled-up brims, short trousers, black stockings, and shoes with buckles, the ancient priest’s costume, with the easy and secure manner of ecclesiastics in solidly religious countries.

The character of the mountains, which one might expect to soften and become more cheerful as one approaches Italy, appeared on the contrary to be one of extraordinary harshness and savagery. It seemed as if Nature delighted in overturning one’s expectations, or wished to offer a repoussoir, as artists say, directing one towards the graceful perspectives succeeding. The reversal is most curious, since it is Switzerland which seems Italian, and Italy which seems Swiss, on this astonishing Simplon Pass.

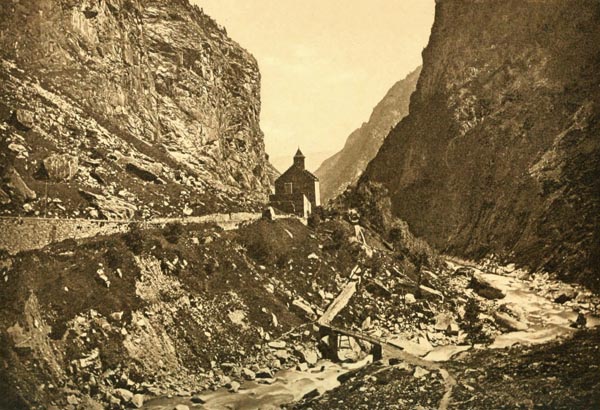

The River Doveria on the Simplon Pass

From the point where the descent to the village of Simplon commences, there are two more leagues to cover, which is quickly done: several times we crossed an extremely noisy and convulsive torrent, over which a conduit, constructed of wooden troughs, passes, like an aqueduct, towards the meadows it supplies with water.

While travelling, we compared the mountains with the Spanish Sierras we had traversed. Nothing could be more different: the Sierra Morena, with its broad platforms of red marble, its green oaks and cork-trees; the Sierra Nevada, with its diamantine torrents in which oleanders soak their roots, with its complex folds and satin reflections the colour of a pigeon’s throat, with its peaks reddening in the evening like young girls to whom one speaks of love; the Alpujarras, whose escarpments are bathed by the sea, with their old Moorish towns and watchtowers perched on inaccessible plateaus, and their slopes where the scorched turf imitates a lion’s skin; the Sierra of Guadarrama, bristling with masses of bluish granite that one might think are Celtic dolmens and menhirs; they, in no way, resemble the Alps, for Nature, while deploying apparently similar material, ever produces a variety of effects.

Part III: Simplon – Domodossola – Luciano Zane

The village of Simplon consists of a few houses clustered at the side of the road, and provides a degree of ease for the comfort of travellers. We halted there, and dined at a fairly clean inn. In the dining room was hung a painting on parchment, in grisaille, representing the conquest of India by the English, and which might have served as a set of illustrations for Joseph Méry’s La Guerre du Nizam, because of the mixture of lords and Brahmins, of ladies and bayaderes, carriages and palanquins, horses and elephants, half-naked peons and lackeys in livery, of sepoys and horse-guards, which rendered the tapestry an encyclopaedia of India, pleasant to consult while awaiting the soup. Several facetious artists had chosen to add moustaches to the Grand Bayadere, a pipe to Lady William Cavendish-Bentinck, a cotton cap to the Governor-General and a Phalansterian pig-tail to the most venerable of Pandits; but these capricious ornamentations failed to destroy the general harmony. This Anglo-Indian parchment was also employed for registering and receiving the names of travellers. A few sly jesters had coupled various parties who would have been greatly surprised to find themselves linked together.

The slopes became steeper and steeper; where the road bends the valley flows into a gorge; the mountains’ lateral slopes steepened dreadfully; the rocks were abrupt, perpendicular, sometimes even overhanging the road; the cliffs, which showed traces of mining everywhere, revealed that they had only offered a passage after long resistance, and that it had been necessary to ignite tons of powder to achieve this. The colours of the scenery turned darker, and light barely descended into the depths of the narrow cuttings; green patches, dark, almost black, in hue, which indicated fir-forest, striped the tawny rocks, much like a tiger’s hide, and granted them a savage appearance. The streams became waterfalls, and at the bottom of the gigantic cleft, which seemed as if created by an axe-blow from a Titan, roared and whirled the river Diveria, the type of raging torrent that, instead of water, churns a mixture of granite blocks, huge stones, and sodden earth, amidst a whitish spray; its bed, much wider than the river, in which it wallows and twists convulsively, looks akin to a street in some cyclopean city following an earthquake; it is a chaos of rocks, lumps of marbles, fragments of the mountainside which take the shapes of entablatures, architraves, sections of columns, and walls; in other places, the whitened stones form immense ossuaries; they appear like the burial-places of mastodons and other antediluvian creatures, brought to light by the passage of water. All is ruin, devastation, desolation, danger and menace: uprooted trees are twisted like blades of straw, rocks driven together shock the hearing with the fearful noise created, and yet we were there in the most favourable season. In winter, one’s passage must be something of a miracle or a sheer impossibility. One should hire those designers who invented that fantastic cleft (the Wolf’s Glen) in which the magic bullets are cast in Carl Maria von Weber’s opera Der Freischütz to pen some sketches of the Gondo Gorge.

The Diveria, however furious and all-consuming it may appear, nonetheless rendered a great service to humankind; without its efforts those colossal masses could not have been split. Its water, brooking no obstacle, paved the way for the engineer. The road follows a rough outline of its course. Torrent and road mutually coexist. Sometimes the torrent encroaches on the road, sometimes the road encroaches on the torrent. Sometimes a cliff raises a gigantic rampart in opposition that could not be crossed or diverted; at those places a cutting, pierced through the rock, with chisels and explosives, removed the difficulty. The Gondo cutting, pierced by two openings which render it the most admirable and melodramatic of semi-subterranean passages, is the longest, and follows on from that of Algaby. It is six hundred feet long, and carries a plaque opposite one of the side openings, bearing the short and noble inscription: Ære Italo 1805, Nap. imp.

Near its exit, the Frasinone and two other torrents, flowing from the Rossbode Glacier, rush, furiously, into the abyss with a dreadful noise. The road runs along a ledge projecting over the chasm. The rock walls, rough, black, bristling, dripping, and out of true, narrow even further, and prevent one seeing, between their summits, two thousand feet higher, anything but a narrow strip of sky which shines brightly, far distant from you, like a ray of hope. Below all is night; cold and deathly; never a shaft of sunshine falls there. It is the most savagely picturesque place in the pass.

Through this scene of natural disorder, rolls the road, bending, almost always, at right angles and most suddenly. Although, in Spain, I had, three times, descended this kind of roller coaster, called a descarga, at the triple gallop, amid the cries of the zagal, the mayoral, and the delantero, amidst a storm of whip-blows, harness-bells, and insults, I could not defend myself from a certain degree of emotion in tumbling down thus, on three wheels, the fourth restrained by a brake-shoe which gripped badly, the horses, barely under control, snorting above the void, down very steep slopes lacking a parapet in almost all the most dangerous places. It seemed we would overturn at any moment; however, that failed to occur, and the tips of the larches or rocks rising from the depths of the abyss were deprived of the pleasure of impaling us. During the winter season, sleds are employed, since, say the guides, if a sled slides into the abyss, one has time to throw oneself clear: a most striking benefit!

After traversing bold bridges, and prodigious underground passages, there being one where the whole weight of the mountain presses on a mere pile of masonry, we arrived at a slightly less-restricted portion of road. The valley widened, the Diveria broadened out, much more at its ease, the banks of cloud and mist dissipated in thinner streaks. Light filtered less stingily from the sky; the grey, green, harsh, and icy tints which characterise Alpine horrors, warmed a little. A few houses were emboldened enough to show their noses through the clumps of trees on the less steep stretches, and not long afterwards, we reached Iselle, a small village where we encountered the first Piedmontese customs-house.

The customs-house is a building surrounded by an arcaded portico supported by grey granite columns. I noticed a sundial on the wall, its role somewhat of a sinecure, since it must seldom feel the sun’s rays. It bore the following inscription: Torna, tornando il sol, l’ombra smarrita, ma non ritorna più l’eta fuggita: with the returning sun, the lost shadow returns, as ever, but the time we have lost returns to us never. An Italian concetto (conceit) is already at play with regard to philosophical thought in the words torna, tornando, ritorna. Oh, how much starker, and more terrible, was the warning that the dial of the church at Urrugne, on the border with Spain, once gave me, with its terrifying comment on the flight of time: Vulnerant omnes, ultima necut: all things wound, the last kills! Gnomons and dials, we understand your language; and our passports bear the stamp: Vivere memento: remember to live. As we pass before you, we hasten our steps, even if we are weary, and have found a pleasant place to pitch our tent; for we know we must hurry to view this earth, which will soon absorb us in her vast embrace.

The landscape brightened, and became more cheerful. Carts and oxcarts passed to and fro, country folk appeared from the byways; the women, quite pretty, their skirts with a broad red band above the hem, gazed at us from wide southern eyes. White villas, bell-towers rising amidst seas of greenery; vines spreading their cradling garlands; one felt, by a certain elegance, that one was no longer in Switzerland. The Diveria continued to flow in its stony bed, but at a respectful distance, like some rough, uncultivated companion who, at the entrance to the city, prefers to leave you; yet the roadway studded here and there with enormous stones where an arch of the bridge had previously washed away, testified to its poor character. Even Napoleon, who built for eternity, could not construct a bridge strong enough to defy the head-butts from its torrent: this graceful valley is named Dovearo.

A rather singular, and un-Italian detail, at least to our northern ideas, was the bourgeois umbrella, the patriarchal parapluie, carried by all the people we encountered, men, women and children; the very beggars themselves bore an umbrella. We soon learned why.

At the last bend in the road, stands a chapel overlooking a cemetery; then one arrives at the Crevola bridge, completing all Simplon’s prodigies with its marvellous construction. This bridge, with its two arches supported by a pier and abutments, of immense height since the cross of the church located below barely reaches the balustrade, heads the valley of Domodossola, which can be traversed from there in its entirety.

Next to the stone bridge, a wooden footbridge over the Diveria serves to connect the village’s houses scattered on either bank.

Italy presented itself to us in an unexpected aspect. Instead of the azure sky and warm orange tones we had dreamed of, though failing to consider that, after all, northern Italy could scarcely possess the climate of Naples, we met with a cloudy sky, vaporous mountains, perspectives bathed in bluish mist, like a view of some place in Scotland, done by an English watercolourist, a moist, verdant, velvety landscape worthy of being praised by a Lake poet.

Though not the picture we had imagined, the one we had before our eyes was no less beautiful; the mountains blurred by the clouds that dissolved in rain, the green flats strewn with villas, the road lined with houses festooned with vines supported by granite pillars, the gardens enclosed by upright stone slabs, formed, despite the storm which delivered a downpour, a graceful and magnificent ensemble. Already, every detail of construction revealed an instinct for beauty, and an attention to form, which exists neither in France nor in Switzerland.

We were approaching Domodossola, which we did not delay in entering, in pouring rain, which, for reasons that we said earlier, caught no one unprepared. The square in Domodossola, in the form of a trapezoid, is quite picturesque, with its archways on squat pillars, its projecting balconies, its overhanging roofs, its columned galleries, and its pavilions topped with weathervanes.

The inn where the stagecoach halted was painted, in the Italian fashion, with crude frescoes, or rather daubs in tempera, representing landscapes interspersed with palm trees and exotic plants. Round its central courtyard, as in a Spanish patio, a gallery with greyish columns reigned. It was seven in the evening; we were to leave at two in the morning; and it was raining like a latter-day Flood. We had dined in the village of Simplon, so the recourse of spending time over a meal was denied us. We asked the hotel waiter if by chance there was something of interest to attend in the town. The theatre was closed, and the impresario who had mounted his puppet-play there, had completed the final performance the day before; but he had not yet departed Domodossola. We had the idea of organising an evening for ourselves and, accompanied by a guide who thought we were mad, we leapt the puddles, in a dense shower of rain, in search of the marionnettista. While walking, we tried to take in various aspects of the town. In the fading daylight, we were able as yet to observe pious pictures on the walls, and statuettes of badly-painted madonnas, lit by lamps.

One of these frescoes took as its subject the Holy Virgin elevating souls from purgatory, accompanied by Saint Gervasius and Saint Protasius (the patron saints of Milan). Such representations are common in the streets and along the roads of Italy; at every step there are little monuments, with calvaries in relief, painted in natural colours, dedicated to Our Lady, guardian-angels, or devotions particular to the specific area.

The puppeteer was not at home; he had gone to dine at the osteria (wine-bar), and, though there was a certain cruelty involved in disturbing a poor man drinking his glass of red wine before a morsel of fried polenta, we were filled with the courage engendered by our whim, and Luciano Zane (for that was the impresario’s name) agreed for twenty francs, half his normal takings, to give us a special performance, being charmed, though a little surprised, by our caprice. He asked for an hour to gather together his orchestra, warn his partner, dress his actors, mount his set, and light the room.

After an hour, through the relentless rain, we walked to the theatre. A lantern was lit over a sign indicating the entrance that read: Performance Here. The town’s female urchins, whom we allowed in, had already filled the benches, and it was a pleasure to see the black eyes sparkle, and the pretty pink mouths smile, in the light of the lamps, repeated by the mirror placed behind to reflect them. Nothing was simpler than this auditorium; four whitewashed walls, a few benches, a wooden platform, and the puppet-theatre raised by three or four feet, on trestles. Its curtain, due to that vague memory of the artistic tradition which never fades in Italy, recalled the famous fresco Aurora, by Guido Reni, which can be admired at the Palazzo Pallavicini-Rospigliosi, in Rome, the engraving of which is popular, though this was in the strangest Etruscan, sugary-brown style to be found anywhere.

The orchestra, composed of the usual four musicians, one of whom beat time strongly with his foot, played a short overture, and the curtain rose to our great satisfaction, and that of all the little girls, who also rose somewhat, the better to view the performance.

Firstly, Girolamo, Caliph for Twenty-Four Hours, or The Living Who Pretended to be Dead, was performed; the tale of that drunkard from the Thousand and One Nights who was transported to the palace by Harun al-Rashid and his faithful Jafar mingled together with a comic-opera plot worthy of Eugène Scribe and Henri de Saint-Georges, and which perhaps derived from their collaboration. Girolamo, who spoke in the Piedmontese dialect, while the other actors delivered their words in purest Italian, wore a coloured French outfit the colour of currants, and a tousled wig embellished with a grotesquely braided pigtail. His grimacing mask showed a twisted mouth, and eyes starting from his head; he stammered, gesticulated and struggled like a man possessed. Girolamo is a character who reappeared in several acts, as Girolamo the music-master, Girolamo the doctor despite himself: he is a sort of Sganarelle (see Molière’s play ‘Le Médecin malgré lui’), but more cunning, meaner, less of an ass. In certain ways, he resembles Mayeux (a grotesque character created by Charles-Joseph Traviès de Villers): he is sensual, a seducer, a courtier, and where necessary a deceiver, all this with a certain stamp of stupidity and rusticity that the puppeteer, who animated this nervis alienis mobile lignum (wooden mobile worked by alien fingers), conveyed very effectively; every entrance Girolamo made was therefore greeted with great bursts of laughter.

It makes a strange spectacle, and one that soon takes on disturbing reality, this representation by means of marionettes. Never did a caricaturist create a more bitter parody of life. Hogarth, Cruikshank, Goya, Daumier, Paul Gavarni, none achieve this depth of involuntary irony. How many famous actors would blush with vexation if they saw their false, mannered gestures, their studied poses in front of the mirror, repeated with a mechanical stupidity crueller than all the criticism in the world! Is this not, moreover, the whole secret of human comedy? A few dozen automatons lacking minds and hearts, motley pieces of wood adorned with tinsel, to which two or three hidden hands grant a phantasm of existence, and which are made to speak, at will, in voices they themselves do not possess.

Luciano Zane and his partner gave utterance to Girolamo, Harun-al-Rachid, Jaffar, and various other characters; a woman’s voice, contralto in tone, lent its powers to the princess and the odalisques: it was the voice of Luciano Zane’s wife, perched on a bench, behind the backcloth, beside her husband.

The scenery was not too badly done, and by an exaggeration of perspective, looked like the views created by children’s optical toys. The interior of the Caliph’s palace showed an imaginative effort to portray oriental luxury; Africans bearing torches were depicted, acting as caryatids and supporting a ceiling reminiscent of the Alhambra. The main attraction was followed by a mythological ballet, The Revenge of Medea, regarding which the choreographer had failed to respect Horace’s precept that Medea should not slaughter her children in public (Ars Poetica:185); because the sorceress immolated, with the wildest fury, two resilient little dolls, forming a group which in no way recalled the painting by Eugène Delacroix (Medea About to Kill Her Children: Louvre). So as not to grieve some dancers we know, we will not describe the pas seul and pas de deux of the performers, which equalled Arthur Saint-Léon for elevation, and threatened the walls and scenery, at every moment. But what lovely attitudes in a constrained compass, and what savage choreography!

The ballet over, we dived backstage. Luciano Zane showed us his repertoire composed of several manuscripts in Italian with interlinear translations in dialect; the actors and their wardrobes were ranged tidily in various drawers; there they were, lying side by side in complete concord, the high priest, the king, the queen, the princess, the Caliph, Girolamo, the good genie, the evil genie, Death, David and Goliath, the Knight and his Lady, all the characters of that little world of automatons; the clothes with their sequins, piping, gauze, and frills, gleamed.

The sight made us think of the opening of Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship, where he recounts his childhood passion for puppetry, and where, in the evening, he brings Mariane, the actress with whom he is in love, and who perhaps anticipates a different kind of present, the figurines which entertained him so much in his youth and developed in him a taste for the theatre. He explains to the young woman at length the character, and role, of each doll, while she looks longingly at her bed from time to time and ends by falling asleep on his shoulder: a wise warning which one should profit from.

We returned, delighted with Luciano Zane, who writes his own plays, paints his own decorations, creates and clothes his own puppets, until we were told that the greatest talent in that genre, the illustrious, incomparable, and never to be praised highly enough practitioner of the art, was a certain Famiola (Gaspare ‘Giuseppe’ Colla, whose puppet-protagonist was Famiola) of Varallo, an admirable man whose puppets’ eyes and mouth moved, who did not recite but improvised, making political allusions of great finesse and incredible audacity, a charming man, addressing to the women, of whom his theatre was always full, a thousand jests and bon mots that made them laugh till they cried; he presented the taking of Peschiera (1848) with cannons, mortars and uniformed soldiers in exact detail; he made perfect little dancers perform, who made you die of love when they danced the saltarello, twisting their little wooden bodies about; Famiola, in sum, was the best of all: he only possessed one fault, that of being in Pallanza (at the Marionette theatre of Casa Borromeo, on Isola Bella) to the east of us, beside Lake Maggiore, which he might well have recently left. We dreamt of interrupting our journey, and setting ourselves to chase after Famiola, except that, before following him to the ends of the world to locate him, we had word that we were to take our places in the diligence Instead of following Famiola, as we wished, we departed for Milan. It was wiser to do so; but, while being driven through the darkness, we still dreamed of beautiful puppets who, with extravagant gestures, cavorted amidst our slumbers.

Part IV: Lake Maggiore – Sesto Calende – Milan

The rain continued, and the vague light of dawn drowned in clouds so low that they almost touched the earth and merged with the vapours that rose from the ground. We twice crossed a small torrential river, already swollen by the storm, by ferry, and, when day dawned, we were on the banks of Lake Maggiore, above Baveno; the water, agitated by the night’s troubled weather, undulated in an agitated manner, and the lake maintained a strong swell like the sea. However, the sky was clearing ahead of us; though huge grey and black clouds, still sending down gusts of rain, had piled against the mountains on the far side of the lake. These mountains, lively in hue owing to the vegetation covering them, highlighted the vaporous peaks of Monte Rosa, and those above the Simplon and Saint Gotthard passes, visible in the background; their reflections turned the waters brown, the landscape seemed severe; Lake Maggiore, which we had imagined to be a golden cup filled with azure, possessed a tempestuous and hostile countenance. We found beauty where we had expected grace.

Our route bordered the lake, and waves licked the roadway; we progressed beside an endless series of gardens, and villas with white peristyles, roofed with rounded tiles, and of terraces garlanded with lush vines, supported by granite props. There, granite fulfils the function of fir-wood at home. It is used for fencing, piles, and even plank-like slabs, on which washerwomen soap laundry by the lake, on their knees as if to ask its forgiveness for this outrage. On these terraces, often of several tiers, which support well-tended gardens, all kinds of flowers and shrubs flourish. We noted on several occasions, and not without astonishment, for it was the first time we had encountered the like, masses of gigantic hydrangeas, which, instead of displaying the pink or mauve colours common in France, offered charming shades of azure: these blue hydrangeas really struck us, since blue is the chimerical dream of horticulturists, who seek the blue tulip, the blue rose, the blue dahlia, without finding them, the number of flowers of that colour being extremely limited. I write this trembling with fear, lest I am scolded by Alphonse Karr, who is unforgiving where literary botany is concerned. But the hydrangeas of Lake Maggiore are undeniably blue. We were told that the colour was obtained by growing them in ericaceous compost. Such is the advice of the gardeners of the Borromean Islands, which must be good advice, since all these hydrangeas the colour of the sky, were magnificent. The same result can also be achieved by sprinkling the earth with iron salts.

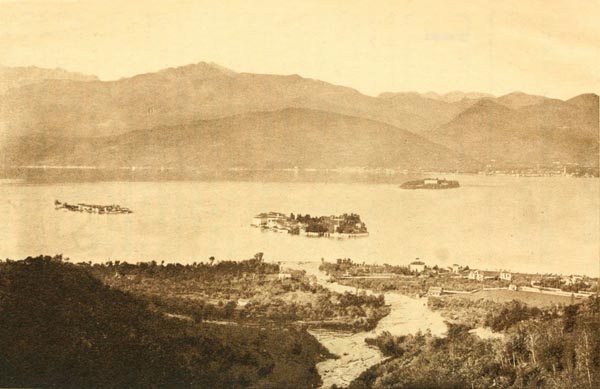

Lake Maggiore - The Borromean Islands

The Borromean Islands, three in number, Isola Madre, Isola Bella, and Isola dei Pescatori (along with two islets), are located in the eastern bay of the lake, which forms a kind of horn whose tip is turned towards Domodossola. The islands were originally bare and barren rocks. Vitaliano VI Borromeo had fertile soil brought there. and constructed gardens with a European reputation. I say constructed, deliberately; since masonry plays a wide role there, as in almost all Italian gardens, which are more works of architecture than gardens. There are more pieces of marble planted there than shrubs, and Vignola (the architect Giacomo Barozzi), had a greater influence upon the isle than André le Nôtre, or Jean de la Quintinie. Isola Madre like Isola Bella, is composed of an ascending series of receding terraces dominated by a palace. Isola Bella, which can be seen very distinctly from the road, is adorned with turrets, spires, statues, fountains, porticos, colonnades, vases, and all the richest architectural decoration. There are even trees such as cypresses, orange-trees, myrtles, lemon-trees, citrons, cedars and Canadian pines; but it is obvious that the vegetation is no more than an accessory; the simple idea of placing greenery, flowers and grass there, only dawned later, like all natural ideas. Isola dei Pescatori, whose rusticity makes a happy contrast with the somewhat pretentious grandeur of Isola Madre and Isola Bella, bathes the feet of its arcaded houses in the water.

These islands have been the subject of enthusiastic descriptions which they do not justify when seen from the shore. The ten terraces of Isola Bella, crowned by a unicorn, or terminating in a Pegasus, have a theatrical aspect which hardly suits the word humilitas, the motto of the Borromean family, inscribed in every corner. Isola Madre, with its seven embankments, supports a square place, tedious in its symmetry, and we were surprised that it is so warmly celebrated. There, one finds the ideal and prototype of the French garden as it was understood in the days of Louis XIV, a garden which Antoine, Boileau’s gardener, would have loved. The Romantic imagination, with all due respect to Jean-Jaques Rousseau, who wished to place his Julie there, would do well to choose another site for their heroines; this one would better suit Madame de Lafayette’s princesses.

It is in Belgirate, a little before Arona, that Alessandro Manzoni, the illustrious author of Promessi sposi (The Betrothed) lives. He is often seen sitting in front of his door, facing the lake, watching the passers-by. He has a benevolent, venerable, distinguished face, whose lean outlines recall the visage of Alphonse de Lamartine. Each day, whatever the weather, one of his friends, some profound philosopher or metaphysician, visits him, in order to commence one of these elevated discussions which find no solution here below, since they speak of the high mysteries of the soul, of the infinite and of eternity.

The lake, and the road, are very lively: the lake with fishing boats, passing yachts, and the pyroscaphes (steamboats) which ply the route between Bellinzona at the northern end of Lake Maggiore and Sesto Calende at the southern end; the road with oxcarts, carriages, and pedestrians armed with the inevitable umbrella. The countrywomen, sometimes pretty, are afflicted with goitres as in Valais; wherever they obtain, the proximity of mountains and snow water produce the same effects.

Approaching Arona, one sees on the hill to the right the Sancarlone, the colossal statue of San Carlo Borromeo, which dominates the lake; it is the largest statue created since the Colossus of Rhodes, or that of Nero, in the Golden House. The saint, posed in a simple and noble attitude, holds a book in one hand and with the other seems to bless the land that he protects and which extends at his feet. One can climb, within, to the head of this colossus, which is made of forged and cast iron, by a staircase made in the mass of masonry with which it is filled. This giant statue, which gradually emerges from the woods with which the hill is covered, and which ends by dominating the horizon like a solitary watchman, produces a singular effect.

Arona, where we halted for lunch, has a completely Spanish air. The houses possess projecting roofs and balconies, iron-grilles on the lower windows, painted frames, and Madonnas on the walls. The church, in which where there are beautiful paintings by Gaudenzio Ferrari, and which we lacked the time to visit, recalls the churches of Spain. In the inn, we found the interior courtyard decorated with columns and galleries as in Andalusia, and a thousand similar striking details.

The lake ends at Sesto Calende. The Ticino pours into Lake Maggiore at this point. Sesto-Calende is on the far bank, and we crossed the river by ferry, since the road to Milan passes through that little town. While the stagecoach was positioned in the loaded vessel, a weird, little old man, grimacing, with head tilted and fingers involved in extravagant exertions, performed a popular air, with a melody both joyful and melancholy, on a violin which was not from Cremona despite that town neighbouring on Milan. Encouraged by the donation of a small coin, he continued to play throughout the passage, and we made our entry to Sesto Calende to the sounds of music, which made us appear very dashing.

We quite liked Sesto Calende. It was market-day, a favourable circumstance for a traveller: because a market brings a characteristic crowd of people from the depths of the countryside who would be very difficult to observe otherwise. Most of the women wore their hair in the traditional style to charming effect, braided, carefully coiled above the nape of the neck, and secured with thirty or forty silver pins arranged in a halo and standing up above the head like the teeth of a comb; one more large pin, decorated at each end with an enormous metal oval and passed through the coils, completes this adornment, which reminded us of the women of Valencia. The pins, called spontoni, are quite expensive, and yet we have seen poor women, and young girls, wearing their hair like this despite their frayed skirts, and bare dusty feet; they doubtless sacrifice essential items to purchase this luxury. But is not a woman’s primary need that of being beautiful, and are not silver pins preferable to shoes? We were so delighted not to see them wearing those dreadful cotton kerchiefs from Rouen, which they had the right to employ according to the current fashion, that we could have kissed them, out of love for the tradition; the pretty ones of course. The men, though poorly dressed, were not in blouses, a thing which rendered us happy, and compensated for the deep pain that we experienced in the province of Gipuzcoa, on encountering that hideous garment unexpectedly, when we attended the Bilbao bullfight the previous year: yet some wore the calanes hat, with a turned-up brim, as in Spain, and their tanned complexions harmonised with that female hairstyle so superior to those rolls of hair, or explosions of curls à la Constance Pipelet, with which women, generally, believe they must crown themselves.

The tiled roofs ahead, the whitewashed walls, the complicated grilles on the windows, gave Sesto Calende an appearance far closer to Gipuzkoa’s Irun or Hondarribia, than one might think: the stalls burdened with watermelons, tomatoes, pumpkins, and coarse pottery, already had a very southern appearance; the annual whitewash on the walls of the houses had respected their frescoes some of which are quite old, and which display pious sentiments. One of these paintings, which presented itself to the eye on descending from the Ticino ferry, was a Madonna carrying the child Jesus in her arms: an inscription which I copied gives the date, Hoc opus fecit fieri Antonius Varallus, XIII Martis 1564. I also noticed on the apse of the church a Christ in a petticoat, like the Christ of Burgos.

Austrian rule began at Sesto Calende. The other shore of the lake is Piedmontese. It is in Sesto Calende that we encountered, for the first time, the tight blue trousers and white tunics of the Hungarian military, a uniform many examples of which one sees in the Kingdom of Lombardo-Venetia that we were going to explore. Our luggage was inspected, but summarily and without the trouble to be expected according to traveller’s tales. We were then asked for our passports, which were returned to us very politely after a few minutes spent, awaiting them, in a room decorated with maps and views of Venice, and whose window overlooked a courtyard populated with half-plucked chickens, with the most laughably fierce yet pitiful physiognomies in the world. These miserable poultry, ready for the spit, pecked about gravely with a scattering of feathers on their backs. However, as regards this promptness regarding the passports, I must add that our travel details had already been sent ahead from Paris, and copied into all the registers; thus, we travelled quickly, having only been detained for a day in Geneva.

Let me not complete my description of Sesto Calende without giving a portrait of a young girl who stood on the threshold of a shop. The dark interior provided a strong warm background, from which she emerged like a Giorgione portrait. We saluted, in her, southern beauty in its purest form. Her black eyes shone like coals beneath her amber-coloured forehead, amidst her dull pallor. She owned to that uniform complexion, that faccia smorta which is in no way due to sickliness, and which indicates that passion has concentrated all its owner’s blood in the heart. Her dense, coarse, shiny hair, curled in small waves, rose on her temples, as if the breeze had lifted it, and her neck joined her shoulders in a simple but powerful line. She, tranquilly, allowed us to gaze at her without anger or coquetry, thinking us painters or poets, perhaps both, and granting us the gift of her unintentional pose.

The Austrian postillion wore a rather picturesque costume, a green jacket with yellow and black aiguillettes, good strong boots, a hat rimmed with copper, and at his side that hunting horn which often echoes in Schubert’s melodies. A thing worthy of note was that the postillion, who in every country advances civilization in the form of the post, since civilization and circulation are, so to speak, synonymous, is one of the last adherents of local colour. He carries the English about in their mackintoshes and waterproofs, while retaining his colourful and characteristic livery; the past cracking its whip urges on the future.

From Sesto Calende to Milan, the road is lined with vineyards, and plantations of trees displaying the most vigorous and luxuriant vegetation. Their branches extend and block the view, and we advanced between two walls of verdure, bathed by streams of flowing water.