Chrétien de Troyes

Yvain (Or The Knight of the Lion)

Part IV

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2018 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Lines 5457-5770 Yvain defeats the two devils

- Lines 5771-5871 Yvain returns to King Arthur’s court

- Lines 5872-5924 All await the expiry of the time decreed

- Lines 5925-5990 The sisters insist on their respective causes

- Lines 5991-6148 Gawain and Yvain contest the issue

- Lines 6149-6228 The two fight to a standstill

- Lines 6229-6526 Their identities are revealed, Arthur gives judgement

- Lines 6527-6658 Yvain rides to the fountain, and rouses the tempest

- Lines 6659-6706 Lunete goes to find Yvain

- Lines 6707-6748 The lady finds Yvain is the Knight of the Lion

- Lines 6749-6766 The lady accepts she must reconcile with Yvain

- Lines 6767-6788 Yvain seeks their reconciliation

- Lines 6789-6803 Yvain and his lady are reconciled

- Lines 6804-6808 Chretien’s envoi

Lines 5457-5770 Yvain defeats the two devils

AFTER the Mass, my Lord Yvain,

In view of the warning, was fain

To leave, still believing naught

Would a swift departure thwart:

It happened not as he desired.

On saying: ‘I shall go now, sire,

If you please, and by your leave.’

‘As yet I cannot grant you leave,

My friend,’ the lord to him replied.

‘The reason you must be denied

Is that we practice here, you see,

A piece of violent devilry,

To which I’m bound to adhere.

For I’ll now summon to appear

Two great fellows, fierce and strong,

To whom, whether right or wrong,

A challenge you must now extend;

And if you can your life defend,

And defeat, and slay these two,

My daughter shall wed with you,

And of this castle you will win

The lordship, and thus all within.’

‘Sire,’ said he, ‘I wish for neither.

God grant me not your daughter,

And by your side may she remain;

The German Emperor would fain

Marry with her she is so lovely.’

‘Let me hear no more,’ said he,

‘Since there’s no escape for you,

My castle and my daughter too

He must have, with all my land,

Who defeats the two who stand

Full ready to assail you now.

You’ll not evade a fight, I vow,

Nor can renounce it any wise;

From sheer cowardice, I surmise

You would refuse my daughter,

Thinking that in such a manner

You might well escape the fight;

But know this as true, sir knight,

That contend with them you must.

For no knight escapes their thrust,

Who lodges in this perilous place.

Established custom now you face,

A custom which will long endure;

My daughter shall not wed before

I’ve seen them go down to defeat,

The two that you have yet to meet.’

‘Despite myself then, I must fight,

Though willingly, and with delight,

I assure you, I’d renounce the same.

And yet that honour I shall claim,

Reluctantly, since it must be so.’

Then there appeared, black as woe,

Those two sons, beloved of night,

Both of them bearing for the fight

A crooked club of cornel wood

Which they had clad, to draw hot blood,

In copper, and had bound with brass.

From the shoulder each one was

Armoured right down to the knee,

But the head and face were free,

And their legs were wholly bare,

Of which each had a brawny pair.

Armed thus they came towards him,

Bearing round shields, light and trim

Yet sturdy enough for the fight.

The lion quivered at the sight,

For from the weapons it could see,

And understand, most readily,

That, as enemies, they’d appeared

To fight its master, or so it feared.

It roused and bristled in a moment,

Shaking with rage and brave intent,

Thrashing the ground with its tail,

Thinking its efforts might avail

To rescue its master ere he die.

And, on seeing the lion, they cry:

‘Fellow, remove that lion from hence

That, menacing us, doth give offence.

Surrender yourself as our prisoner,

Or otherwise, we hereby declare,

You must set it where it can do

No harm to us, or give aid to you;

Where it cannot take part, in short.

You must come alone to our sport.

For there’s no doubt the lion would

Willingly aid you, if it could.’

‘Move him yourselves, if you fear,’

Said my Lord Yvain, loud and clear,

‘For I would be well-satisfied

If it came about that he terrified

Both of you, and gave aid to me.’

‘Indeed,’ they said, ‘it shall not be!

Do the very best you can alone;

Of other aid, you shall have none.

Single-handed, free of all others,

You must fight us both together.

If that lion kept you company

Two against two that would be,

For if his aid we should condone,

Then you’d not be fighting alone,

So you must, you’ll understand,

Remove the lion, as we demand,

However much you may object.’

‘Where then do you want him kept?

Where then would you have him be?’

Pointing to a room all could see,

They said: ‘Let the lion stay there.’

‘It shall be done, tis your affair,’

He said, and led the lion away.

When tis done, they send away

For armour to protect his body,

And his horse, saddled and ready,

They bring to him, and he mounts.

Then the two open their account

By riding at him to do him harm,

Since now the lion fails to alarm,

Being imprisoned in that room.

With their maces they seek his doom,

Landing such blows on helm and shield

That scant protection do they yield.

For, striking his helm, they begin

To beat and drive the metal in,

And his shield too they shatter

Like glass; the holes they batter

Are wide enough to insert a fist,

Since all their strength they enlist.

What can he do against these devils?

Urged on by shame, dreading evil,

He defends fiercely with all his might,

And, steeling himself to the fight,

Deals powerful and weighty blows;

They lose nothing for he bestows

Two blows for every gift of theirs.

But now the lion is in despair,

Grieved at heart, in his prison,

For he recalls the kindness done

Him by his master’s brave deed

Who must surely have great need

Now of his service and his aid.

His master might now be repaid,

In full measure, the whole amount

Of his kindness, with no discount,

If he could but escape from there.

So he searches the room with care;

Still he can find no clear way out,

Hearing the noise of blows without,

The fight being perilous and dire;

And rages, fuelled by his desire;

Yet his great grief pains him more,

So he revisits the well-worn door;

The thing is rotten about the sill,

He tears away at the wood until

He is through up to his haunches.

Meanwhile my Lord Yvain launches

Blow on blow, toiling and sweating.

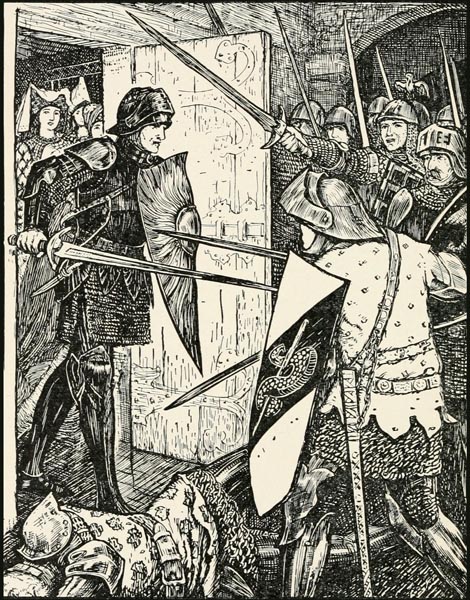

‘Yvain launches blow on blow, toiling and sweating’

The Book of Romance (p177, 1902) - Andrew Lang (1844-1912)

Internet Archive Book Images

Now these two devils he was finding

Strong and fell, to blows inured.

And many a blow had he endured,

And repaid them as best he could,

Yet every blow they withstood

Being well-skilled in the fight,

While their shields, unlike the knight’s,

Were such they resisted every blade,

However sharp twas and well-made.

So strong were the two, Lord Yvain

Knew that he now faced death again,

Yet he contrived to fight on alone

Till the lion escaped, on its own,

By tearing away at the door’s sill.

If these devils they cannot kill

Between them now, they never will,

For the lion will attack them till

He or they die, while it still lives.

It launches at one and doth give

Him such a blow, he falls like a tree.

The wretch himself, in terror is he,

But there is no man in that place

Without a look of joy on his face;

For the devil will ne’er rise again

Unless the other doth him sustain,

The lion having laid him full low.

The second devil seeing the blow

Runs to help, and himself defend

Lest the lion doth turn and rend

Him, once it has the other killed,

Whom to the earth it has spilled;

For he suffers from greater fear

Of the lion than its master here.

My Lord Yvain were now a fool

Seeing the back now of the ghoul,

Bare-necked, as his arm’s stronger,

If he spares his life much longer,

For the moment serves him well.

The neck bared, the head as well,

The villain was open to his blow,

And such a one now did follow

He beheaded him, like a shot,

So smoothly that he knew it not.

Then to the ground he descended

By the other, the lion had up-ended,

Wishing to assist and save him,

But in vain, for the lion had him,

Such that no doctor was of use.

It had attacked him, once twas loose,

Quite furiously, and wounding him

Had left him in the plight he was in.

Yet Yvain dragged the lion back,

And saw the shoulder had, alack,

Been torn from its socket clear.

Of the fellow he had lost all fear,

His club had fallen from his hand,

While he lay there like a dead man,

Who might neither move nor stir;

Yet he had strength to utter a word,

And said, as clearly as he could:

‘Remove your lion, if you would,

Fair sire, lest he work further harm;

You may do, without more alarm,

With myself whate’er you desire.

He who mercy asks and requires,

Should not be denied that grace,

Unless one pitiless he doth face.

I will defend myself no more,

Nor from here can I rise I’m sure,

For I’d have need of aid so to do,

And thus I entrust myself to you.’

‘Say then,’ said he, ‘that you render

Yourself defeated, and thus surrender.’

‘Sire,’ he replied, ‘the battle is lost.

Despite my efforts, I paid the cost.

And my submission I here tender.’

‘Then you need fear me no longer;

The lion will harm you no more.’

Onto the field a crowd now pour,

And they surround him, anew;

And the lord, and his lady too,

Embrace him joyfully, and seek

Of their daughter now to speak,

Saying to him: ‘You shall be

Lord and master of all that we

Possess, and wed our daughter,

For upon you we bestow her.’

‘Yet I hereby restore her to you.

Let those who have her keep her too.

I care not, though tis not disdain,

For your daughter,’ said Lord Yvain.

‘I cannot, and I must not, take her.

But deliver to me, at your pleasure,

The wretched women held here yet;

For the right of it is, lest you forget,

The terms dictate that go they may.’

‘Tis true,’ he said, ‘tis as you say,

And I surrender them, willingly,

For an end to all of it let there be.

But you will take, or so I advise,

My wealthy daughter, if you are wise,

For she is charming, prudent, fair;

Never so rich a marriage, I swear,

Shall you find if you take her not.’

‘Sir,’ he replied ‘you know naught

Of my commitments and my affairs,

Nor to explain them do I dare;

But know you this, if I refuse

What no man would e’er refuse,

Whose heart and will were free

To settle on a girl such as she,

I would willingly marry her,

If I could, and no harm incur.

But I cannot; nor your daughter

Nor, if truth be told, any other.

And so let me depart in peace,

For the demoiselle awaits me,

Who did accompany me here.

As she held to me, tis clear

I should seek to hold to her,

Whate’er to me might occur.’

‘You wish to go, fair sir, but how?

Never, unless I so allow,

And my judgement tells me to.

My gate will not open to you,

And you remain my prisoner.

You are prey to pride and error

If I ask that you, to your gain,

Wed my daughter and you disdain.’

‘Disdain, sir? No, upon my soul,

I can take none to have and hold,

Nor linger here, on any account.

I can do naught else but mount,

And ride with the maiden now,

But, by my right hand, I vow,

And swear to you, if you agree,

That I’ll return, plain as you see

Me now; that is, if ever I can,

And receive your daughter’s hand,

Whenever that seems good to you.

‘Fool be he who seeks from you

Pledge, or oath, or word, or promise!

If my daughter had pleased, I wist

Tis soon enough that you’d be back.

But you’ll return no sooner, alack,

For swearing that you will come;

So go now, I release you from

All pledges, oaths and promises;

Naught you do will me distress,

For I care not where’er you go!

My opinion of her is not so low

I’d bestow my daughter anywhere.

Now be you about your own affairs,

Tis all the same to me, this day,

If you go now, or if you stay.’

Lines 5771-5871 Yvain returns to King Arthur’s court

THUS my Lord Yvain turned away

From the tower, and would not stay,

And before him went the maidens,

Those so wretchedly imprisoned,

Poor, ill-clad, weary in every limb,

Whom the lord had released to him.

Now they are rich it seems to them,

For they are free of the tower again,

Preceding Yvain, two by two,

With no less joy, I say to you,

Than they would have felt if He

Who made this world of ours wholly,

Had descended from Heaven to Earth.

Those who’d deemed him of little worth,

The folk who’d warned him previously,

Now come to beg for mercy and peace;

And seek to escort him on his way.

He knows not why they beg he says:

‘What you mean by it, I cannot tell,

For you are free of blame as well,

And I can think of naught you said

That did me harm, or to harm has led.’

They are delighted so to hear,

And all hold his courtesy dear,

And, after escorting him some way,

They commend him to God alway.

And then the maidens, for their part,

Having asked his leave, so depart.

And, as they leave him, all do bow,

And they express the wish that now

God will grant him health and joy,

And protect him from all annoy,

Wherever it is that he might be.

Then he, being anxious to leave,

Replied: ‘God save you, equally.

Go, and safe and happy may He

Now conduct you to your country.’

Thus they part from him joyfully,

While, as they go, my Lord Yvain

Takes himself to the road again,

And in the opposite direction.

And all that week they hasten,

Led by the maid, for every day

She never fails to find the way,

Making the best speed they can

To the place where she had left

That lady of all her lands bereft.

But when the lady hears the news

And the maiden comes in view,

Leading the Knight of the Lion,

Her delight is second to none,

Such the joy that fills her heart;

For she believes that now her part

Of the inheritance, her sister must

Relinquish to her, as is only just.

She had been ill a goodly while

This lady, and but a little while

Recovered from the malady

That had troubled her greatly,

As was apparent from her face.

But now she hurried on, apace,

To greet them without delay,

And honour them in every way.

In every manner that she might.

Of the joy indoors that night,

I’ll not speak, though I surely could;

Yet not a word of that joy should

Be told, for it would take too long.

So I’ll neglect it, and pass along

To the morrow when they did ride,

And journeyed on till they espied

The castle wherein King Arthur

Had lodged a fortnight or longer.

Now, the elder sister lodges there

Who has stolen her sister’s share;

For she has kept close to the court,

Waiting her sister’s advent, in short,

Who’s on her way, and drawing near.

Yet the elder sister feels little fear,

Doubting the younger has on hand

Any knight who could withstand

The prowess of my Lord Gawain.

And only a day doth now remain,

Of the forty that were decreed;

And by law and justice, indeed

The inheritance is hers alone

And she can claim it as her own,

Once that certain day has passed.

And yet more might be done, at last,

Than she e’er believed or thought.

Humble are their lodgings, sought

Outside the castle, for the night,

Where none who know them might

Recognise them; if lodgings they

Take there within then many may,

And for that they do not care;

Their lodgings thus are mean and bare.

As morn is breaking they emerge,

But then with the dawn shadows merge,

Until the sun shines clear and bright.

Lines 5872-5924 All await the expiry of the time decreed

I know not how many days might

Have passed since my Lord Gawain

Had vanished, and all would fain

Have news of him, all of the court,

Except she whose cause he sought

To defend, that is, the elder sister;

For she knew he had hidden near,

But three or four short leagues away.

When he returned, on that day,

None who knew him at court

Recognised him, as they ought,

For he was wearing strange armour.

Openly, thus, the elder sister

Presented him to all the court,

As one whom she had brought

To defend her cause though she

Had wronged her sister utterly.

She said to the king: ‘Now, Sire

The time allotted has expired,

Tis almost noon, this is the day.

And I, for witness it now you may,

Am ready to maintain my rights.

If my sister could produce a knight

To fight for her then we should wait.

But, God be thanked, she is too late,

She neither sends word, nor is here.

Tis plain, she will not now appear,

And all her trouble was for naught,

While I have my champion brought

Prepared till this hour, at your sign,

To prove my right to what is mine.

I’ve proved it thus, without a fight.

And I may now, as is my right

Enjoy my inheritance in peace;

And no account of its increase

Henceforth to my sister give;

And sad and wretched may she live.’

But King Arthur who well knew

That the lady great wrong did do,

As disloyal to her younger sister,

Said: ‘It is the custom, my dear,

In royal courts, i’faith, to wait

While justice doth yet deliberate,

Until the king decides the case.

We’ll grant her a little grace,

For I think she may yet appear,

And we shall see your sister here.’

Before the king’s speech was done,

He beheld the Knight of the Lion,

And saw the younger sister too.

Alone, they advanced, these two,

Having left the lion, out of sight,

There, where they’d passed the night.

Lines 5925-5990 The sisters insist on their respective causes

THE king had the maid in view,

And at once her face he knew,

And he was filled with delight

To see her there beside the knight;

In his concern for what was right,

Holding she was wronged quite.

Full of joy, at seeing her near

He called out to her, loud and clear:

‘God save you! Approach, fair maid!’

The elder heard him and, afraid,

Turned about, and saw the younger,

And the knight too, whom her sister

Had brought, to aid and support her;

And her face turned black as thunder.

The maiden was welcomed, in short,

And, before the king and his court,

Cried: ‘King, if my rightful claim

Can by a knight be here maintained

Then it shall be so by this knight;

And he my thanks doth earn outright,

Whom I have brought to this affair,

Though he hath business elsewhere,

A knight so courteous and debonair;

Yet he’s taken such pity on me,

He has set aside, as you can see,

All other affairs for my own.

Let courtesy and right be shown

Now, by this lady, my sister dear,

Whom I love with a love sincere,

By yielding me what is my right,

So betwixt us peace shine bright;

For I ask of her naught that’s hers.’

‘Nor do I ask aught of my sister’s,’

The elder said, ‘for she has naught

Nor shall; and naught is the import

Of her words, and naught the gain.

Now may she wither away in pain.’

Then the younger sister, since she

Was wise in the ways of courtesy,

And was prudent too and charming,

Replied: ‘Grief to me it doth bring,

That two such gentlemen should fight,

On our behalf, to prove what’s right.

Though tis a small disagreement,

I may not renounce my intent,

For I am left in too great need;

So I’d be grateful to you indeed

If you would render me my share.’

The elder sister replied: ‘Whoe’er

Would do so must surely be mad.

May I with fire and flame be clad,

Before I seek to improve your lot!

The rivers will run boiling hot,

The sun elect to shine at night,

Before I will renounce this fight.’

‘God, and the right I claim in this,

In which my trust both was and is,

Always, until this present hour,

May they both now lend their power

To one whose kindness and pity

Is offered thus in service to me;

Though I know not who he may be,

And he doth know no more of me!’

Lines 5991-6148 Gawain and Yvain contest the issue

ONCE their words were at an end,

They led out the knights to defend

Their two causes, amidst the court.

And everyone a place there sought,

In the way folk are accustomed to

Whenever they’ve a wish to view

A fine battle between two knights.

But these two who are set to fight,

Who’ve shown love to one another,

Have failed to recognise each other.

Do they still love each other now?

Both ‘Yes,’ and ‘No’, do I avow.

And I will prove both to be true

In revealing my reasons to you.

In truth then my Lord Gawain

As his companion loves Yvain,

And Yvain him where’er he be;

Even here if he knew ‘twere he,

He would now make much of him

And he would give his life for him;

As he would give his life, Gawain,

Before harm came to Lord Yvain.

Is that not Love, entire and fine?

Yes, certainly. Is there no sign

Of Hate being equally present?

For one thing is indeed apparent,

This day they’d both wish to devote

To flying at one another’s throat,

Or in wounding the other so

He the depths of shame might know.

I’faith, tis wondrously revealed

That in one heart may be concealed

Faithful Love and mortal Hate.

Lord, how in one dwelling-place

Can things which are such contraries

Reside, as twould appear do these?

For in one dwelling, it seems to me

There cannot lodge two contraries.

Since they could not appear together

In that dwelling, in any manner,

Without some quarrel being aired

If each knew the other was there.

But as the body has several members,

As lodgings have several chambers,

Such might well be the case here:

I think Love’s chosen to disappear

Into the depths of a hidden room,

While Hate has chosen to assume

A seat high up, above the scene,

So as to be both heard and seen.

For Hate now is mounted on high,

And pricks and spurs so to outfly

Love, with ease, as oft may prove,

While Love indeed fails to move.

Ah, Love! Where art thou now?

Reveal yourself, regard the crowd

That the enemy brings against you;

Enemies makes of your friends too.

For enemies are these two friends,

Who love each other to holy ends,

With that love, nor false nor faint,

Precious, worthy of many a saint.

Here Love proves utterly blind,

And Hate is sightless too we find,

For if Love had recognised them,

He would them have obliged them

Never to attack each other

Or do harm to one another.

Thus, in this matter, Love is blind

Discomfited, to error consigned;

And those who are Love’s by right,

Love knows not in broad daylight.

And e’en though Hate cannot state

Why each the other doth so hate,

Hate would see them both frustrate

The other through such mortal hate.

No man loves another, or could,

Who’d do him harm, and draw blood,

Seek his death, or see him shamed.

How then? Would my Lord Yvain

Kill his friend, my Lord Gawain?

Yes, and he the other, the same.

Would then his friend, my Lord Gawain

With his own hands slay Yvain,

Or do some worse thing instead?

No, I swear not; as I have said,

Neither would his true friend disarm,

Nor bring him shame, nor do him harm,

For aught with which God graces man,

Or the Empire of Rome doth command.

And yet I cannot help but lie,

For one can plainly see, say I,

That with lances thus they hover

Ready to attack each other.

And each would strike his friend

And wound him though he defend,

And work him woe without restraint.

Gainst whom shall he lodge complaint?

Who has the worst then of the fight,

When conquered by the other knight?

For if they now should come to blows

The fear is great, I would suppose,

That each will fight against his friend,

Till one of them the fight shall end.

Could Yvain claim, in all reason,

If he is worsted, that tis treason;

That he has been hurt or shamed

By a man that he’d have named

As a friend, one who has never

Called him aught but that ever?

Or if injury were done Gawain,

Would he be right to complain,

He had therefore been betrayed,

If he were shamed in any way?

No, for he’d know not by whom.

Now, they grant each other room,

Prepared for their joint encounter.

At the first shock the lances shiver,

Though they are ashen and strong.

Neither uttered a word thereon,

Yet if they had exchanged a word,

Their meeting had proved absurd.

Neither lance nor sword, we know,

Would have dealt a single blow.

They’d have kissed and embraced,

Rather than each other have faced.

Yet as they face each other now

Their swords win naught, I vow;

Nor their helms nor their shields,

Which are dented as they yield;

While the keenness of each blade,

They blunt, the steel they abrade.

Many a harsh blow they pledge,

Not with the flat, with the edge,

And the pommels deal such blows

On the neck, and about the nose,

And on the cheeks and brow too,

That the skin is black and blue

For, beneath, the blood gathers.

And their chain-mail shatters,

While the shields are so unsound,

Beneath them dire harm is found.

So hard they labour, courting death,

They can scarcely catch their breath;

And so hotly they strive to win,

That every emerald and jacinth

That upon their helmets is inset,

Is crushed to shards at their onset;

While the two so pound away

With the pommels, both are dazed,

Almost braining one another.

Their eyes in their sockets glitter,

The heavy fists are firmly squared,

Solid the bones, and strong the nerves;

They strike each other about the face

As long as they can grip their blades,

Which offer them both good service,

While they wield them in their fists.

Lines 6149-6228 The two fight to a standstill

WHEN a long while they’d striven,

Till their helms were wholly riven;

And they with the steel had flailed

Fiercely enough to split their mail,

The shields too frail now to contest,

Both drew back a little, to rest;

To let the blood cool in their veins,

And so restore their breath again.

And yet they do not long delay,

But attack, strongly as they may,

More fiercely even than before;

And all confess they never saw

A pair of more courageous knights:

‘It is no manner of game this fight;

Their cause each strives to assert,

And their worth and true deserts

Will ne’er be rendered completely.’

The two friends heard them, surely,

And knew that all spoke together

Of reconciling sister to sister,

Yet had failed to devise a way

To pacify the elder that day,

Nor placate her in any manner;

While the intent of the younger

Was but the king’s word to obey,

Not contradict him in any way.

Yet the elder is so stubborn here

That even the queen, Guinevere,

And the lords also, and the king,

Most courteous in everything,

All side with the younger sister.

To the king requests are proffered,

That he, despite the elder sister,

Might grant title to the younger,

At least a third or a quarter part;

And might these two knights part

Who had displayed such courage;

For it would do the court damage

If one should now the other injure,

Or deprive him of any honour.

Yet now the king declares that he

Is unable to achieve a peace,

For the elder is such a creature

As desires not peace, by nature.

All this was fully understood

By the two knights who stood

Against each other there, while all

Marvelled at so equal a battle,

For none knew nor could attest

Which was worst, and which was best.

Even the two who are in the fight

Where pain wins honour as a knight,

Marvel now, and are taken aback,

That both prove equal in attack;

Such that each man wonders who

Is matched with him and doth pursue

Such fierce combat, while the light

Fades, and day draws on to night.

They have fought, and fight, so long.

That neither man waxes as strong,

Their bodies tire, the arms weary.

While warm blood, trickling slowly

From many a wound to the ground,

There beneath their mail runs down.

They are both in such distress,

No wonder if they wish to rest.

They feel no further urge to fight,

Partly because of the fall of night,

Partly through mutual respect,

Reasons that lead them to effect

A truce, and swear to keep the peace.

Yet, ere they leave the field, these

Two shall disclose their identities,

And affirm their love and sympathy.

Lines 6229-6526 Their identities are revealed, Arthur gives judgement

MY Lord Yvain it was spoke first,

Yvain, the brave and courteous;

Yet his good friend knew him not

From his speech, since he had got

Such a deal of blows his blood

Was sluggish and, though he stood,

His speech was both low and faint,

His voice yet subject to constraint.

‘Sir,’ said he ‘night doth approach,

I think nor blame nor reproach

Accrues to those parted by night.

But, for my part, I say, sir knight,

I admire you, and much respect you;

Never in my life have I so rued

A contest, so suffered in a fight,

Nor ever thought to see a knight

Whom I would so seek to know.

You grasp both how to land a blow

And how to employ your strength.

No knight I have fought at length

Has dealt me such blows as those.

Against my will, I took the blows

That I’ve received from you today.

My head felt every blow, I say.’

‘By my faith,’ said my Lord Gawain,

‘I am no less mazed and faint

Than you are, but rather more so;

Twill please you I think to know

If I but tell you the simple truth,

Of what I lent you, in good sooth,

You have rendered full account,

Adding interest to that amount;

For you were readier to render it

Than I to receive the half of it.

But now, however that may be,

As you wish to know from me

By what name I may be called,

I’ll not hide it from you at all;

Son of King Lot am I, Gawain.’

On hearing this, my Lord Yvain

Is sorely troubled and amazed,

And, by anger and sorrow mazed;

To the earth his sword he throws,

From which the blood yet flows,

And then his shattered shield also,

And down from his horse he goes,

Crying: ‘Alas! What mischance!

How, through mutual ignorance,

We have battled with each other

Not recognising one another!

If I had known that it was you

I would never have fought with you;

Before e’er dealing a single blow

I’d have yielded, as you well know.’

‘How so,’ cries my Lord Gawain,

‘Who art thou then?’ ‘I am Yvain,

Who loves you more than any man

In all the world doth love, or can.

For you have loved me always,

And honoured me, all my days.

And now, in this business too,

I’d make amends and honour you,

For I offer complete surrender.’

‘So much to me you’d render?’

Said the noble Lord Gawain,

‘Surely twould bring me shame,

To let you thus seek amends.

The honour is not mine, my friend,

But yours, to whom I thus resign it.

‘Ah! Speak, fair sir, no more of it!

What you have said can never be;

For I can endure no more you see,

I am so wearied from the fight.’

‘Surely, your wounds are but light,’

His friend and companion replied,

‘While I’m sore overcome,’ he sighed,

‘And I offer that not in flattery,

For there’s no stranger, equally,

To whom I would not say the same.

Rather than suffer further pain.’

So saying, Gawain descended

And to each other they extended

Their arms in friendly embrace,

Each swearing to the other’s face

Twas himself who’d met defeat,

Their protestations incomplete

When the king and his knights

Joining them, to assess their plight,

And finding them joined in amity,

Desired to know how this could be,

And who these two knights were

Who such mutual joy did aver.

‘Gentlemen,’ said the king, ‘tell me

What has brought about such amity

Between you both, this rare accord

After the enmity and discord

You have exhibited all day?’

‘Sire, your request I now obey,’

Replied his nephew, Lord Gawain,

‘The cause of conflict and the pain

That thus ensued, of that I’ll tell,

Since you attend us here as well,

To hear of it, and know the truth.

It is right to inform you, in sooth,

That I, sire, your nephew, Gawain,

Failed to recognise twas Yvain,

My companion, fought with me,

Till God was pleased, thankfully,

To prompt him to ask my name.

Once I replied, and he the same,

We knew the other, but not until

We both had fought to a standstill.

Already we had fought for long,

And if we had continued strong

And fought on as furiously

It would have gone most ill for me;

He’d have slain me, upon my life,

Given injustice caused this strife,

And given also Yvain’s prowess;

Much better it is, I now confess,

My friend defeats me than kills me.’

Rising to this claim, and fiercely,

My Lord Yvain replied, in one:

‘God aid me, my dear companion,

You are in error in saying so.

Let my Lord the King, now know,

That I was defeated in the fight,

And surrendered, as well I might.’

‘No, I.’ ‘No, I.’ Thus they dispute.

And both are so courteous, in truth,

That each the honour and the crown

Grants the other, and lays it down.

Neither gives way to the other here,

But strives to make King Arthur hear,

And all the people gathered round,

That defeated, he yields the ground.

Yet, after indulging them, a little,

The king ended the loving quarrel.

For he indeed took much pleasure

In what he heard, and the measure

Of these friends in warm embrace,

Though while fighting face to face

They had wounded each other too.

‘My lords,’ said he ‘twixt you two,

Lies great affection, as can be seen

By each conceding defeat, I mean;

So place yourself now in my hands

And I’ll arrange, as I have planned,

That in great honour you’ll be held

And I’ll be praised by all the world.’

Then they both swore, most willingly,

To obey his wish, and loyally

Accept all that he chose to say.

And then the king said, that today

He’d resolve the cause, and justly.

‘Where now,’ he asked, ‘is that lady

Who forcibly, by her command,

Has seized her own sister’s land?

‘Sire,’ cried the elder, ‘here I am.’

‘Are you there? Well then, advance,

You who claimed the inheritance.

For some time now have I known

That you your sister’s right disown,

But she’ll no longer be denied,

For you the evidence supplied;

You must now resign her share.’

‘Ah, sire,’ she answered,’ if I there

Spoke a thought, unwise, absurd,

Do not now take me at my word.

For God’s sake, do not harm me!

You are the king, and should be

Wary of every wrong and error.’

‘And that is why I wish to render

To your sister what is her right;

Against the wrong I’ll ever fight,’

Said the king, ‘You will have heard

How both your champion and hers

Have left the matter in my hands.

You’ll not have what you demand.

For its injustice is obvious.

Each claims that his was the loss,

Seeking so to honour the other.

But upon that I will not linger,

Since the judgement lies with me.

Either you obey me promptly,

In regard to what I pronounce,

Willingly, or I shall announce

My nephew it was that met defeat.

That would all your cause unseat;

Yet I would do so, against my will.’

He would never so have done, still

He said it to see whether she would

In fear of him, perform the good,

And render to her sister, at once,

Her share of the inheritance;

For the king quite clearly saw

That she would surrender naught,

Despite aught that he might say

Unless force or fear won the day.

And due to her doubt and fear

She replied: ‘Sire, it is clear,

I must yield to you, for my part,

Though indeed it grieves my heart.

But I will do what yet grieves me,

My sister shall have what she seeks,

As her share; and I will advance

As guarantor of her inheritance,

Your own self, to reassure her.’

‘Then, swiftly, restore it to her,’

Said the king, ‘and let her now stand

As your vassal, and from your hand

Receive her share, and then may you

Love her, and she to you prove true,

As her lady and her sister.’

Thus the king resolved the matter,

While the younger received her share

And thanked the king for all his care.

So then the king asked his nephew,

That knight most valiant and true,

That of his armour he be eased,

And Lord Yvain, if he so pleased,

To lay aside his armour too,

Who now might suffer so to do.

Thus they disarmed as he dictated,

And on equal terms they separated.

And while they were thus disarming,

They saw the lion come running,

That was seeking for its master.

As soon as the lion drew nearer,

It demonstrated its delight;

While all the folk there took fright,

Even the bold began to flee.

Then my Lord Yvain cried he:

‘Stay, why run, none chases you?

Fear not that it will mischief do;

The lion there that you now see

Is mine, and I am his; trust me,

If you but will, that we are one,

And each a true companion.’

Then those folk were assured

Who had heard voiced abroad

All the adventures of the lion

And all those of his companion,

That this was the very knight

Who’d killed the vile giant in fight;

And my Lord Gawain then said:

‘My dear friend, God be my aid,

You fill me with shame today.

I little merited of you, I say,

The service you rendered me

In saving my nephews and niece;

Slaying the giant, so fearlessly.

I have been thinking, fruitlessly,

Of whom that knight might be

For it was said that I and he

Were well-acquainted; indeed,

I thought a deal on it, you see;

But I could never come upon

A memory of a fighting man,

Whom I’d heard tell of anywhere,

In any land where I did fare,

And known by name to anyone,

As this same Knight of the Lion.’

They disarmed as Yvain replied,

And the lion came to his side,

To the place where his master sat,

And reaching him this giant cat

Showed all the joy a dumb beast might.

Then it was meet that both the knights

Be led to the infirmary, and there,

Receive a royal doctor’s care,

And have their wounds treated swiftly.

Now, Arthur, who loved them dearly,

Had the two men brought before him,

And a surgeon, he’d attached to him

As one who knew more than most,

He now had minister to them both.

And he worked on them so well

He returned them both to health

More swiftly than any other might.

And when he had healed the knights,

My Lord Yvain, whose heart was yet,

Without recourse, on his love set,

Knew that he would not last a day

But would die of his love alway,

If she, for love of whom, his lady,

He was dying, showed no mercy.

So he thought to leave the court

And go alone to where he’d fought

Beside the fountain that was hers,

And cause there such a mighty stir,

Such a tempest of wind and rain,

That perforce she must then again

Grant him peace, or there would never

Be an end to the business ever

Of the troubling of that fountain,

And all its storm of wind and rain.

Lines 6527-6658 Yvain rides to the fountain, and rouses the tempest

SO, now, once my Lord Yvain

Felt fully healed and sound again

He left the court, with none knowing

Where he and the lion were going;

For the lion wished its life to be

Spent in its master’s company.

They journeyed on until they saw,

The fount, and made the rain to pour.

Don’t think I seek to tell a lie

If I say the tempest, there on high,

Was so violent none could tell

A tenth of it; caught in its spell

It seemed the whole forest would drown;

While the lady feared for the town,

Lest it too foundered altogether.

The tower sways, the walls totter,

And, about to fall, hang perilously.

The bravest Turk would rather be

A prisoner in Persia than it befall

That he is trapped between such walls.

The folk are so filled with fear they

Revile their ancestors; thus they say:

‘Let that man’s name be accursed

Who, within this town, was first

To build a house; accursed its founder,

Who in this world could find no other

Place more evil, where but one man

May invade our territory, and can

Trouble us and torment us so!’

‘You must take good counsel though,

In this matter, lady,’ said Lunete,

‘For you will find no other yet

To aid you in this hour of need

Unless you seek far off indeed;

Or we shall never have repose

In this castle, nor dare expose

Our lives to aught beyond the wall.

Not a knight here will meet the call,

As well you know, for none will dare

To offer himself in this affair;

Even the best of them step back.

And should it appear that you lack

A knight to defend your fountain

You will seem a fool, for certain.

True, great honour to you accrues

If he who attacks it should choose

To withdraw now without a fight;

Yet you will be in sadder plight

If you can think of no better plan.’

‘If you, who are so wise then, can

Some better plan at once devise,

Then I will do as you advise,’

Cried the lady. ‘If I’d one, as yet,

I’d willingly share it,’ said Lunete,

‘But you have need for a greater

Source of wisdom than I can offer.

And since I can do no better,

With the others I will suffer

Both the wind and pouring rain

Until, please God, I see again,

At your court, some worthy knight,

Who’ll take it on himself to fight,

And bear the burden of the battle.

Although, as far as I can tell,

Today, no such thing shall be.’

‘No more of him!’ cried the lady,

Exceeding prompt in her reply.

‘You know, among my folk, that I

Have not one whom I might expect

To step forward and, to any effect,

Defend the fountain and the stone.

I ask, that you yourself, alone,

Determine what should be our plan!

In need, they say, woman or man,

May prove the value of a friend.’

‘Lady, if any knows where to send

For him who slew the giant outright,

And overcame the three knights,

Then he’d do well to do so now.

Yet while that knight, I do avow,

Knows his lady’s anger and scorn,

There is no man or woman born,

It seems to me, he would follow

Unless she swore, on oath also,

All in her power would be done

To set aside the enmity shown

By her, to him, for tis my belief,

He is dying of trouble and grief.’

And the lady said: ‘I will attest,

Ere you enter upon this quest,

To give you my word faithfully,

And swear, that if he comes to me,

I, without guile or deception,

Will do all that can be done

To bring about his peace of mind.’

And Lunete replied: ‘You will find,

My lady, that you may easily

Bring about such a state of peace,

If you so wish; yet before I may

Set out, myself, upon the way,

Do not be angry, I must also

Hear you swear it before I go.’

‘That is well.’ replied the lady.

Lunete, so full of courtesy,

Brought a precious relic to her

Immediately, on which to swear;

And the lady fell to her knees.

Then Lunete, most courteously,

Took her assertion upon oath.

And in administering that oath

She forgot naught that might

Be useful to serve the knight.

‘Lady,’ she said, ‘now raise your hand!

For I’d not wish, you understand,

That you lay some charge on me

After tomorrow, because, you see,

What you do is for you, not me!

Now you shall swear, if you please,

To display your good intention

Towards the Knight of the Lion,

Until he knows he has regained

All the love that once obtained,

As completely as ever he knew.’

The lady raised her hand anew,

And replied: ‘Thus, I swear true:

As you have said, so shall I do,

And if God aid me and the saints

My heart shall ne’er prove faint,

Nor fail to do all in its power.

If strength I own, love is his dower,

And the grace I’ll render him too,

That with his lady he once knew.’

Lines 6659-6706 Lunete goes to find Yvain

LUNETE had done her work full well,

She wished no more than there befell,

For all she’d wished, she had achieved.

Already a mount she had received,

A gentle palfrey, without delay,

Mounted, and set out on her way;

She rode along for some time,

Until she found beneath the pine

One whom she had scarcely thought

To find so near; the man she sought;

For she had expected far and wide

To seek, before that knight she spied.

As soon as e’er she came in view

She saw the lion and thus she knew,

And riding towards him swiftly

Descended to the earth promptly.

And my Lord Yvain knew her

As soon as he set eyes on her;

Gave her greeting, and she he,

Saying: ‘Sir, I’m more than happy

To find you here, so near at hand.’

Said Yvain: ‘Must I understand

That you are here then seeking me?’

‘Yes, my lord, and most joyfully,

More than e’er in my life before.

I’ve so wrought that my lady swore,

On pain, that is, of perjury,

She will be, as she used to be,

Your own lady, and you her lord.

This be the truth, be you assured.’

At this my Lord Yvain rejoiced,

And his deep gratitude he voiced,

Clasped her, and kissed her gently.

‘And his deep gratitude he voiced, Clasped her, and kissed her gently’

The Book of Romance (p122, 1902) - Andrew Lang (1844-1912)

Internet Archive Book Images

She said: ‘Let us away, swiftly!’

Then he demanded: ‘And my name

Have you told it her?’ ‘Nay, blame

Me not, for name have you none

To her, but the Knight of the Lion.’

Lines 6707-6748 The lady finds Yvain is the Knight of the Lion

THUS conversing they went along

The lion behind them following on,

Till to the castle all three came.

The lady before him, Lord Yvain,

As soon as he saw her thus, he fell

Straight to his knees, all armed as well.

And Lunete, who was standing by,

Said: ‘Lady, raise him, and apply

All your efforts, skill and sense

To granting peace and recompense

To one whom you should pardon;

For in all the world, there is none

Except it be you can grant this prize.’

Then the lady made him to rise,

And said: ‘My power is his alone

And willingly I’ll give all I own

If I can but bring him happiness.’

‘Lady, I’d not say this unless

The thing was true,’ said Lunete.

‘All this is now within your power;

You’ve ne’er had nor will you ever

Possess such a good friend as he.

God wills that between you and he

Such sweet love and peace shall be

It shall endure to eternity.

God has let me find him so near.

The proof of this will now appear,

And I have but one thing to say

Lady, grant him pardon today,

For he has no lady but you:

This is Yvain, your husband too.’

Lines 6749-6766 The lady accepts she must reconcile with Yvain

THE lady, trembling at what was said,

Replied: ‘God stand me in good stead,

For now at my own word you take me

And, despite myself, you’d make me

Love a man who accounts me naught.

Well indeed have you now wrought!

A great service now you’ve done me!

I’d rather my whole life should be

But wind and storm, and so endure!

And if ‘twere not that to perjure

Oneself were a vile thing, surely

He would ne’er find peace with me,

Nor true accord twixt us abide.

Always in my heart would hide,

As fire lurks among the cinders,

What I no longer wish to utter,

Nor care to mention here again,

Who seek accord now with Yvain.’

Lines 6767-6788 Yvain seeks their reconciliation

MY Lord Yvain now understood

His cause tended towards the good,

That he would have peace and accord,

And said: ‘Mercy one should afford

To a sinner, my lady. I have paid

For my madness, and dearly I say

I should have paid, full many a day.

Madness twas, made me keep away.

And rendered me guilty and forfeit.

And bold indeed do I prove in it,

By daring to come before you here.

But if you’d wish to keep me here,

Nevermore will I do you wrong.’

She replied: ‘I must go along

With that, for I’m perjured if I

Do not with all my powers try

To make peace now twixt you and me;

Thus, by my faith, the thing must be.’

‘Five hundred thanks, lady,’ said he.

For, may the Holy Spirit aid me,

Never a man in this mortal life

Has for a woman known such strife!’

Lines 6789-6803 Yvain and his lady are reconciled

NOW was my Lord Yvain at peace.

And this, the truth, you may believe,

That he had never such joy of aught,

Despite the trouble it had brought.

For all has turned out well we see,

And Yvain is loved by his lady,

And she by him is held the dearer.

His ills he no more remembers,

For, through joy, all are forgot,

That joy in her which is his lot.

And Lunete’ mind is now at ease,

Nothing is lacking her to please,

She has her contentment gained

In making peace between Yvain

And his dear and charming lady.

Lines 6804-6808 Chretien’s envoi

THUS Chrétien now ends his story,

His worthy romance of Yvain,

For no more doth the tale contain,

Than he has heard, or you may hear,

Unless one seeks to add lies here.

The End of the Tale of Yvain