Chrétien de Troyes

Yvain (Or The Knight of the Lion)

Part III

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2018 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Lines 3563-3898 Yvain promises to rescue Lunete

- Lines 3899-3956 Yvain agrees to fight the giant, Harpin

- Lines 3957-4384 Yvain slays the giant, then hastens to save Lunete

- Lines 4385-4474 Yvain champions Lunete

- Lines 4475-4532 Yvain fights the Seneschal and his brothers

- Lines 4533-4634 Yvain is victorious, and goes to seek his lady

- Lines 4635-4674 Yvain departs carrying the lion inside his shield

- Lines 4675-4702 Yvain and the lion are cured of their wounds

- Lines 4703-4736 The two daughters of the Lord of Blackthorn

- Lines 4737-4758 The younger daughter arrives at Arthur’s court

- Lines 4759-4820 The younger daughter requests a champion

- Lines 4821-4928 The maiden seeks the Knight of the Lion

- Lines 4929-4964 The maiden approaches the magic fountain

- Lines 4965-5106 Yvain agrees to champion the younger daughter

- Lines 5107-5184 The Castle of Ill Adventure

- Lines 5185-5346 The three hundred maidens

- Lines 5347-5456 Yvain receives an initial welcome in the castle

Lines 3563-3898 Yvain promises to rescue Lunete

WHILE Yvain bemoaned his fate

Our poor Lunete, in wretched state,

Imprisoned in the chapel there,

Heard, and saw this whole affair,

Through a crevice in the wall.

And as soon as Yvain was all

Recovered from his swoon, she cried:

‘Now tell me, who is this outside?

Who is it who complaineth so?’

He said: ‘Who is it who would know?’

‘I am,’ she said, ‘a wretched thing,

For I’m the saddest person living.’

And he replied: ‘Ah, fool, be silent!

Your grief is joy, your ill content.

Those who by great joy are won,

Are more saddened and more stunned

By grief than others, when it comes;

The weaker one, by use and custom,

May bear more weight than can another,

Though of greater strength, moreover,

Despite all that the latter would do.’

‘By my faith,’ she said, ‘tis true,

These words you utter I believe,

Yet tis no reason to conceive

That your ills are worse than mine,

And as for that, though you repine,

It seems to me that you are free

To go where’er you wish to be,

While I remain imprisoned here;

Such is my fate, it would appear,

Thus I shall be seized tomorrow,

And must to mortal justice bow.’

‘My God,’ said he, ‘for what misdeed?

‘Sir knight,’ she said, ‘let God indeed

Ne’er have mercy on my poor soul

If I have ever deserved such woe!

Nonetheless I’ll explain to you,

And every word I speak is true,

Why it should be I lie in prison:

I am here, then, accused of treason,

And to defend me can find none;

Tomorrow, I’ll be burned or hung.’

‘Well then,’ he replied, ‘I still say,

That my grief and sorrow outweigh

This grief and woe of yours, for you

Might be delivered by one who knew

Of the danger in which you lay.

Might that be so?’ ‘Why yes, I say!

But who that might be I know not,

There are only two men, God wot,

Who would dare to so defend me,

By warring against three enemies.’

‘What,’ said he, ‘then there are three?’

‘Yes, sir knight, ‘by my faith, there be

Three who call me a traitor, I know’

‘Who are the two who love you so,

That either would be daring enough

To go against these three, for love,

And save and protect you, say I?’

‘I will tell you, and speak no lie,

For the one is my Lord Gawain,

And the other is my Lord Yvain,

Through whom, unjustly, I shall be

Martyred tomorrow; tis death to me.’

‘Through whom? What say you?’ said he,

‘Sire,’ she said, ‘May God defend me,

Through the son of King Urien.’

‘And now,’ he said, ‘I comprehend!

You’ll not die except he dies too,

For I am Yvain, through whom you

Are now prisoned, in deep distress.

And you indeed must be, no less,

Than that Lunete who, most bravely,

Guarded and preserved my body

And life, twixt those portcullises,

When I was troubled and in distress,

Well-dismayed at being so caught.

I should have been killed for sport

Or taken then, if not for your aid.

So tell me then, my sweet maid,

Who is it accuses you of treason,

And keeps you here in this prison,

In such secluded confines too?’

‘Sire,’ she said, ‘I’ll hide naught from you,

Since you would have me tell you all;

Nor was I slow, as I recall,

To assist you in all good faith;

Twas upon my advice i’faith,

My lady took you as her sire,

And by my counsel did so desire;

And, by the sacred Paternoster,

I believed it was for her, rather

Than you, indeed, that I did so;

In all of this I’d have you know.

It was her honour and your desire

I served; God knows I am no liar.

But when it came about that you

Had not returned when you were due,

Within the year that you agreed,

My lady was furious with me,

And said that she had been deceived

By all I’d said, that she’d believed.

And once she’d told her Seneschal,

A cunning and a faithless rascal,

Who towards me bore great envy;

For on many a matter, you see,

She trusted him far less than me.

He knew to pursue his enmity

Against me, and claimed ere long,

In open court, all looking on,

I treacherously favoured you;

Nor had I aid or counsel true,

Except mine own, and yet I knew

Never had I sought to pursue

Treachery in deed, or thought.

So I answered, before the court,

Without taking counsel myself,

That I would be defended well,

By one who’d battle any three.

He was so lacking in courtesy

That he disdained to refuse,

Nor could I retreat, or excuse

Myself whate’er might happen.

At my word had I been taken;

So I was forced to furnish bail,

And in forty days, without fail,

Must find a knight to battle three.

Many courts I journeyed to see;

I travelled to King Arthur’s court,

But found no aid, nor what I sought,

Nor were there any there who could

Tell aught of you, for ill or good,

For of yourself they had no news.’

‘Where then was that kind and true,

And honest knight, my Lord Gawain?

Any maid that to him complained

On approaching him, her distress

He’d ne’er fail thus to address.’

‘If I had found Gawain at court,

Whatever it was that I now sought

He would ne’er have denied it me,

But some knight, so they told me,

Had lately carried off the Queen,

The King having, quite foolishly,

Let her abroad, in his company;

The King, I believe, sent Gawain

After the knight, and he was fain

To seek her, in his great distress.

Nor will he know a moment’s rest,

Until he again restores the lady.

Now have I, and in verity,

Told the whole of my adventure.

Yet tomorrow I’ll live no longer,

For a shameful death, I’ll meet,

All through you and your deceit.’

‘May God forbid,’ Yvain replied,

‘That e’er, for me, you should die!’

Nor shall you yet, while I am here.

Tomorrow, then, will I appear,

Prepared, with all my strength,

To employ my body, at length,

For your deliverance, as I ought.

Take care, if my name is sought,

To tell all those present naught!

And when the battle has been fought,

Still utter not a word of me.’

‘There’s no torment, of a certainty,

Would make me reveal your name,

Since you charge me with the same;

Sire, I would rather suffer death.

Yet I pray that you, nonetheless,

Do not battle thus for my sake.

I would not have you undertake

Such a desperate fight as this.

I thank you too for your promise

That you would willingly do so;

Think yourself free of it, though,

For better it is that I die alone

Than witness the pleasure shown

At your fate, as well as mine;

For to death they’ll me consign

Once they have seen you killed;

Tis better that you live on still,

Than that both encounter death.’

‘Now’ said Yvain, ‘I feel the breath

Of your despair, my dear friend;

I fear that either you intend

To seek death and not be saved,

Or do despise the willing aid

I bring to your deliverance.

Cease such pleas to advance,

For you have wrought so much for me

I shall not fail, of a surety,

To bring you aid, come what may.

Though I witness your dismay;

If it please God, in whom I trust

All three shall lie there in the dust.

Now no more, for now I should

Seek some shelter in that wood,

Since there can be no lodging here.’

‘She replied, ‘May God, my dear,

Give you good shelter and good night,

And, as I wish, keep you outright

From every danger there might be!’

My Lord Yvain, went guardedly

On his way, and the lion after.

They went on, a little further,

Reaching the castle of a baron,

Both well-fortified and strong,

Its walls high, with nary a fault;

Thus the castle feared no assault,

From catapult or mangonel,

Nor could it be stormed at will;

And outside the walls the ground

Had been cleared all around,

With never a hut or dwelling.

And you may hear at some fitting

Time the reason why that was so.

Now, my Lord Gawain did go

The shortest way to the castle,

And seven pages forth did amble,

Once the bridge had been lowered,

To meet him, and yet they cowered

When they had sight of the lion,

All being most afeared of him;

So they asked him, if he pleased,

Whether the lion, for their ease,

Might wait outside, before the gate.

Yvain replied: ‘No more! I state

That I’ll not enter without him;

Either we find lodgings within,

Or I’ll remain outside, myself,

For he is as dear as my own self.

Nonetheless you need fear him not,

For I will keep him close, God wot,

So all of you may be reassured.’

They answered: ‘Be it so, my lord!’

Then the castle they do enter,

And pass on till they encounter

Many a knight and fair lady,

Many a maid of high degree,

Who salute him with honour,

Helping him remove his armour,

Saying: ‘Welcome be yours, fair sir,

Who enter now among us here,

And God grant that you may stay

Until you leave us, on a day,

Rich in honour, and content.’

This, high and low, is their intent;

Their pleasure in him to display,

As they to the castle lead away.

But when their first joy is over,

A deep sadness they remember,

Which makes them forget their joy;

Tears and cries they now employ,

And begin themselves to cudgel.

Thus for a long while they mingle

Tears with joy, joy with sadness;

Joy still in honouring their guest,

Yet their thoughts are elsewhere,

For an event fills them with care

That they expect on the morrow,

Certain they are that it will follow;

Happening, indeed, before midday.

My Lord Yvain was so amazed

At all these frequent changes of tack,

From joyousness to grief, and back,

That he advanced that very question,

Asking the castle’s lord the reason:

‘Fair, dear and gentle sir,’ said he,

‘By God in heaven, please tell me

Why you all have honoured me so,

And thus mix your joy with sorrow?’

‘Yes, if such should be your pleasure,

Yet to know naught of the matter,

Would yet prove far wiser a wish;

To sadden you by speaking of this,

Is what I would ne’er seek to do,

For it can only bring grief to you.’

‘I must not do naught, leave all be,

And fail to hear the truth,’ said he,

‘For I wish greatly now to know,

What trial tis I must undergo.’

‘Well then, I’ll seek to tell you all.

A giant doth this realm appal,

By seeking after my daughter,

Who is more lovely, and by far,

Than any maiden to be found.

This fell giant, whom God confound,

Is named Harpin of the Mountain,

Who, every day, doth cause me pain,

By seizing, from me, all he can.

Better right than I hath no man

To complain, lament, and grieve;

I shall go mad, ah, I do believe,

For had not I six knightly sons,

In all the world the fairest ones,

And the giant has seized all six;

Before my eyes, two he picked

To kill, and the rest, tomorrow,

He will slay, to my great sorrow,

Except I can find one who might

For the lives of my four sons fight,

Or surrender my daughter to him,

Whom he says that he will ruin,

And give to the vilest of his court

The basest fellows, for their sport,

Since he himself loves her no longer.

Such the grief tomorrow offers,

If you or God deny me aid.

So tis not any wonder today

Fair sir, that we are full of sorrow;

Yet, for you, we try to borrow,

For a moment, a cheerful face,

And honour you in this place.

For he’s a fool who has as guest

A nobleman, and fails of his best,

And a noble man you seem to be.

Now have I explained wholly,

The whole cause of our distress;

For in neither town nor fortress

Has this giant left for us aught

Except all that here we brought.

If you have taken a look around,

Then indeed you’ll have found

He has scarce left an egg or two,

But for the walls which are new;

For he has almost razed the place.

When he has taken or defaced

All he wishes, the rest he fires,

And torments me as he desires.’

Lines 3899-3956 Yvain agrees to fight the giant, Harpin

MY Lord Yvain attention paid

To all that his host had to say;

When he had heard everything,

He was pleased to answer him:

‘Sire,’ said he, ‘your unhappiness

Yields me much sorrow and distress,

And yet to me it seems a marvel,

That you have ne’er sought counsel

At the court of good King Arthur,

For there’s no man of such power

That at his court he could not find

Many a knight who’d feel inclined

To prove themselves against him.’

Then this man of wealth tells him

That, at the court, indeed, he would

Have found true aid if any could

Have told him where to find Gawain.

‘Nor would I have asked in vain,

For my wife is his cousin germain:

But a foreign knight had been fain

To lead away the wife of the king,

Whom at the court he’d gone seeking,

Nor would he have succeeded too,

Not by any means that he knew,

Had not Kay beguiled King Arthur

Such that the king had placed her

In the man’s charge, in all innocence;

He a fool, she lacking prudence.

Great the harm and great the loss,

And great the both to me because

Tis certain that my Lord Gawain

Would have hastened here again

For his niece and for his nephews,

If of this matter he’d heard news;

But he knows naught, and so I grieve,

Enough to break one’s heart, I believe;

For he’s gone chasing after that same

Knight, to whom may God grant shame

And woe, for leading the Queen away.’

Hearing all this, my Lord Yvain

Doth frequently yield up a sigh,

And, driven by pity, doth reply:

‘Fair noble sir, right willingly

Will I, instead, take upon me,

This adventure, and its peril,

If the giant and your sons will

Only arrive tomorrow in time,

Delaying me but little, for I’m

Bound to be away, and soon;

Tomorrow at the hour of noon,

A promise I uttered I must keep.’

‘Fair sir, my thanks you shall reap,

A hundred thousand times indeed,’

Said the nobleman, ‘for this deed.’

And all the good folk in his castle,

They thank my Lord Yvain as well.

Lines 3957-4384 Yvain slays the giant, then hastens to save Lunete

THEN came forth from her chamber,

A lovely maiden, his fair daughter,

Her form graceful, her face pleasing.

She was simple, quiet, and grieving,

For her sorrow appeared endless;

Her head was inclined, in sadness.

And then her mother entered too,

For the host had summoned the two

To come to him, and meet his guest;

Both held their mantles to their heads

In order to conceal their tears,

But he urged them to calm their fears,

And uncover their faces straight,

Saying: ‘You should not hesitate,

To do as I now command you to;

God and good fortune have, today,

Brought you this noble man, I say,

And he will fight the giant for us.

Now give thanks to the courageous,

And throw yourselves at his feet!’

‘May God forbid, it is not meet;

Tis no way fitting for me to see

These ladies offer such courtesies,

Sister and niece to my Lord Gawain,’

In protest cried, my Lord Yvain.

And may God Himself defend me

From such pride as could ever see

Them humbling themselves at my name,

For I could never forget the shame.

But I would yet give thanks if they

Were comforted a little this day;

And then tomorrow they will see

If God Himself will grant them mercy.

Yet now I have no other prayer

But that the giant will be there,

And in good time, that I may not

Break my true word, for I must not

Fail to be present at noon elsewhere

Tomorrow, at a mighty affair,

The worst business I must say

I’ve undertaken for many a day.’

Thus doth Yvain show unwilling

To reassure them quite, knowing

That if the giant fails to appear,

In ample time, he must, he fears,

Still rescue Lunete, the maiden,

In the chapel as yet imprisoned.

Nevertheless what he doth promise

Leaves them full of hopefulness;

And he is thanked by one and all,

For his prowess, that men recall,

And think him a true nobleman

Seeing his lion, like a lamb,

As confident in man’s company

As any creature e’er might be.

The hope that they place in him

Comforts and brings joy to them,

And they lay aside their sadness.

And when the hour arrived for rest,

They led him to a fine chamber.

Both the maiden and her mother

Escorted him to a room, quite near,

For they already held him dear,

And a hundred thousand times more

Would have done so, I am sure,

If they’d known all his courtesy

And prowess; and the lion and he

Both lay down, and fell asleep.

But the others all feared the beast,

And shut the door up tight so they

Could not emerge, come what may;

Till the next day, when in the morn,

The door was opened wide at dawn.

Yvain arose, and next heard Mass,

And then, as promised, he let pass

The hour of prime, ere summoning

In the hearing of all, his host to him,

Then he addressed him, with honour:

‘Sire,’ he said, ‘I can wait no longer,

Let me leave, though you wish it not,

For though I linger here, I must not.

But I would have you know that I

Would gladly have stayed to defy

The giant, and I will, awhile at least,

For the sake of the nephews and niece

Of my Lord Gawain, whom I do love.’

At this the maiden is sorely moved,

Her every vein trembles in fear;

The lady and her lord appear

As moved, fearing he will depart,

Wishing from the depths of their hearts

That they might stoop there at his feet,

Yet knowing he’d think it not meet,

Deeming it neither well nor good.

So then his host offered him goods,

Either in land, or some other guise,

Could he but agree, in any wise,

That he with them might so remain.

‘God forbid,’ cried my Lord Yvain,

‘That I should accept aught of yours!

From the maiden the tears do pour;

Greatly she grieves, in her dismay,

Begging him thus that he might stay.

A maid distraught and in distress,

By the Queen of Heaven she begs,

By the angels, and the Lord above,

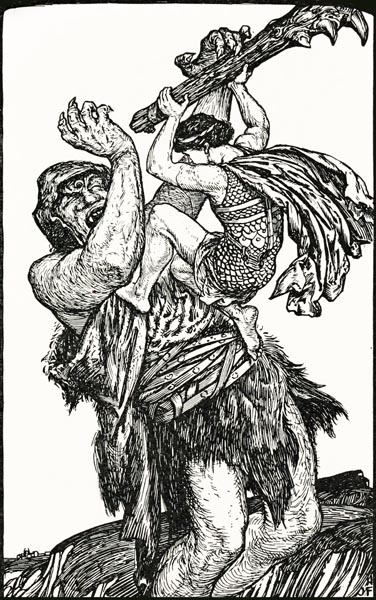

‘By the Queen of Heaven she begs, by the angels, and the Lord above’

The Book of Romance (p352, 1902) - Andrew Lang (1844-1912)

Internet Archive Book Images

That he will elect not to remove,

And for a little while might wait,

For her and for her uncle’s sake,

Whom he doth know, love and prize.

Then doth great pity within him rise,

On hearing her proffer her request,

In the name of the man he loves best,

And in that of the Queen of Heaven,

And God Himself, the sweet leaven,

The honey of mercy none may deny.

Full of anguish he heaves a sigh;

For the kingdom of Tarsus, he

Would not see Lunete, cruelly,

Burned at the stake, she to whom

He gave his promise, for his doom

Would be death, or madness again,

If too late to her help he came;

Yet, on the other hand, to recall

The great kindnesses, above all,

Of his dear friend, Lord Gawain,

Near breaks his heart in two again,

He knowing that he cannot stay.

And yet he doth not ride away,

But so delays and lingers near,

The giant doth suddenly appear,

Driving, in front of him, the knights,

And hanging there at neck-height,

He carries a stake, big and square,

Point before, spurring them there.

Nor were they clothed in aught

Worth a straw, dressed in naught

But torn shirts, filthy and soiled;

Hands and feet tied, they toiled

To stay aloft, on four tired hacks

Weak and thin, with broken backs,

That limped on, as best they could.

As they advanced, beside the wood,

A dwarf, hunchbacked and swollen,

Who’d knotted the horses’ tails in one,

Beat the knights, remorselessly

With a four-tailed scourge, till he

Had marred them from head to toe,

As though some prize for doing so

Were his. He beat them till they bled,

Thus were they shamefully sped,

Betwixt the giant and the dwarf.

The giant cried out to the lord,

Before the gate there, in the plain,

That his four sons would now be slain,

If he did not produce his daughter,

So as to avoid their slaughter;

Then the daughter he would offer

To his lads, to make sport of her,

For he’d not love, or have her, ever;

She’d have a thousand lads about her,

Often enough, and repeatedly,

Naked wretches, vile and lousy,

Scullery boys, scum from the kitchen,

Who’d all grant her their attention.

At this the lord was sore dismayed,

Listening to this fellow portray

What fate his daughter would face,

Or, should he save her from disgrace,

Hearing how his four sons would die.

And such distress is his, say I,

That he would rather die than live.

Full often a deep sigh he doth give,

And weeps and bemoans the day.

Then to him Lord Yvain doth say:

‘Sire, most vile, most insolent,

Boastful, indeed, is this giant.

Yet God above will ne’er suffer

Your daughter to be in his power!’

So says my frank and noble Yvain.

‘He insults her, and shows disdain.

Dire would be the misadventure,

If indeed so lovely a creature,

And one of such high import,

Were given to vile lads in sport.

Come, my armour, and my steed!

Lower the drawbridge now, with speed,

And let me forth, for forth I must.

One will be left here in the dust,

Whether he or I, I do not know;

Yet can I but humiliate, though,

This cruel felon at your gate

Who comes against you straight,

Such that he renders you your sons,

And, for his insults, have him come

And make amends to you, then I

May commend you to God on high,

And go about my own affairs.’

His horse was led to him there,

And a squire his armour brought,

And to arm him swiftly sought,

So that he was soon equipped.

In doing so they let naught slip,

Taking as little time as they might.

Once they had fully armed the knight,

There was naught remained but, lo,

To lower the bridge and let him go.

They lowered it and away he went

Nor was the lion, his friend, content

By any means, to remain behind;

While those who were so left, I find,

Commended him to Our Saviour,

For they greatly feared the power

Of that miscreant, their enemy,

Who’d conquered and slain so many,

On that field, before their eyes,

Anxious lest this end likewise.

So they pray God might defend

From death and save their friend,

And grant he might kill the giant.

And each man prays, as best he can,

Most silently to his God above.

For now the giant made a move,

A fierce advance, threatening too,

Crying: ‘The man who hath sent you

Loves you but little, by my eyes!

And for certain he could realise

Vengeance on you in no better way.

He wreaks his revenge well, I say,

For whatever wrong you’ve done.’

But Yvain, who was afraid of none,

Replied: ‘Mere empty speech I find.

Now do your best and I will mine,

You weary me with words in vain.’

And thereupon my Lord Yvain,

Now anxious to be on his way,

Struck the giant, in fierce assay,

Whose breast a bear-skin covered.

Though the giant soon recovered,

And ran towards him, full pelt,

My Lord Yvain a fresh blow dealt,

On his breast, that broke the skin,

And the tip of his lance drove in,

And tasted hot blood in its course.

Yet, wielding the stake with force,

The giant forced him to bow low.

Yvain drew his sword, fierce blows

Of which he could swiftly deal,

Knowing the giant lacked a shield,

Reliant on brute force instead,

Scorning armour, helm for his head;

Thus he, who had drawn his blade,

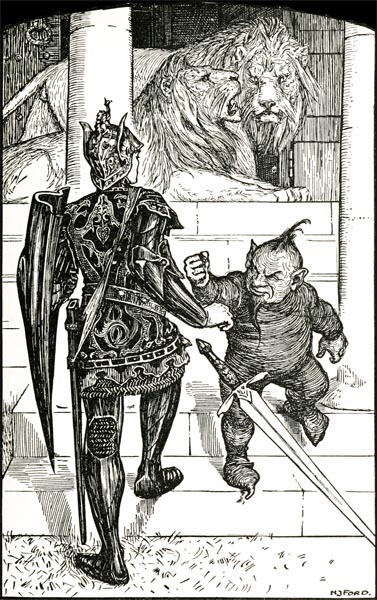

‘Against the giant now made assay, struck the giant a trenchant blow’

The Book of Romance (p260, 1902) - Andrew Lang (1844-1912)

Internet Archive Book Images

Against the giant now made assay,

Struck the giant a trenchant blow,

Not with the flat, but slicing so

As to cut from his cheek a steak,

While the other, wielding his stake,

Dealt Yvain such a blow he fell

Over his horse’s neck, as well.

At the blow, the lion, unafraid,

Rose up, to bring its master aid,

And leapt in anger, tooth and claw

Shredding the pelt the giant wore,

In its rage, like the bark of a tree.

Thus it tore away a massive piece

Of the thigh, with its layer of skin,

Flesh and sinew embedded within.

The giant fought free, with a fierce pull,

Roaring and bellowing, like a bull,

For the lion had wounded him badly.

Wielding his stake in both hands, madly,

He thought to strike the lion but failed,

For the cunning lion swift turned tail,

The giant’s blow was dealt in vain,

And he fell beside my Lord Yvain,

But without either of them touching.

Now did my Lord Yvain, wielding

His sharp sword, land two great blows,

Dealt quickly, before the giant rose,

And with the trenchant edge cut free

The arm and shoulder from the body;

With his next blow he drove the rest

Through the liver, below the chest,

Driving home the whole of his blade;

The giant fell; with his life he paid.

And if a massive oak were to fall,

Twould make no greater sound at all,

Than that giant made when he fell.

All those upon the wall were well

Pleased at seeing that mighty blow.

Then were the speediest seen below,

Longing to be first at the kill,

Like hounds in the chase that will

Run till they seize upon the deer;

So the men and women ran here,

Towards the giant without delay,

Where he now, face downward, lay.

And the lord hastened there as well,

And all the nobles from the castle,

And the daughter, and her mother;

While joy reigned among the brothers,

After the woe those four had suffered.

But though their services they offered,

They saw they could no longer detain,

Despite their prayers, my Lord Yvain;

And yet they beseeched him to return,

To stay and enjoy the rest he’d earned,

As soon as he’d done with the affair

That was summoning him elsewhere.

And he replied that he did not dare

To promise them aught for, once there,

He could say naught for certain, till

He knew if fate meant him good or ill;

But this much he did ask of the lord,

That his four sons seize the dwarf,

And with his daughter ride, amain,

To the court, to my Lord Gawain,

Once they knew of that knight’s return;

And all that happened, there, confirm,

And relate what he had done, alone;

For good deeds should be widely known.

The lord replied: ‘Twould not be right

To hide such kindness from the light,

And,’ he added ‘be sure we shall do

Whatever it is you’d wish us to;

But tell me now what should we say,

Sire, when we meet with Lord Gawain;

To whom should we grant the fame,

Having no knowledge of your name?’

And he replied: ‘This shall you say

When you stand afore him that day,

The Knight of the Lion is my name,

And that I told you to state the same.’

And I now make a request, that you

Convey, from me to him, this truth:

If he knows not then who I may be,

Yet I know him well as he doth me.

There is naught else I require of you,

And thus I must bid you all adieu;

That which doth me most dismay

Is that too long I extend my stay;

For ere the hour of noon is past,

I face elsewhere an ample task,

If I can indeed outrun the hour.’

Then swiftly he rode from the tower,

Though, before he went, his host

Begged him, to the very utmost,

To take with him his four sons,

For of the four there was not one

Would fail to serve him if he wished.

It pleases him not, though they insist,

That any should keep him company;

Forth he goes, that place doth leave,

And, careless of both life and limb,

As fast as his horse can carry him,

He now returns to the distant chapel.

The way ran straight toward the dell,

And he knew how to keep the road;

Before he reached the chapel though

They had dragged Lunete outside;

Already the pyre was raised on high,

On which she’d die in short shrift.

And there, naked but for her shift,

Bound before the pyre they held her,

All those who did her guilt infer,

Based on a plot that she denied.

And now it was that Yvain arrived,

Saw to what they would bring her,

And was thus consumed by anger;

For neither courteous nor wise

Are any who’d think him otherwise.

Indeed his anger proves immense,

But he trusts in God, and hence

That God and the right will see

Him right, they being of his party.

For in their company he will fight,

And no less trusts the lion’s might.

On the crowd he advances swiftly,

Crying: ‘Now, let the maid go free,

You sinful folk, as I do command!

It is not right that she should stand

Within the flames, though innocent.’

And on either side they now relent,

And part to leave him passage way,

Neither will he brook more delay,

Until his own eyes gaze on, there,

She whom he must aid, where’er

She might be, with all his heart;

So his eyes seek her, for his part,

Until he finds her, yet restrains

His heart, as one grasps the reins,

And holds in check, a lively steed.

Nonetheless, he is glad, indeed,

To see her, and sighs so to see,

Although he sighs not openly,

That none might see he does so,

Stifling all, that none might know.

And he is seized with pity also

When he sees, hears, and knows

The grief of the ladies, who cry,

With many a sad tear and sigh:

‘Ah God, thus, you forget us now,

Leave us in deep despair, we trow,

We who shall lose so dear a friend,

Who such good counsel us did lend,

And did intercede for us at court!

She it was for our comfort besought

My lady to clothe us in robes of vair;

All altered now will be our affairs,

For there’ll be none to speak for us.

Cursed be he who caused our loss,

For great is the harm he has brought.

There will be none to say at court:

“Dear lady, give that cloak of vair,

That surcoat and that fine gown there,

To such and such an honest maid,”

For so her charity she displayed,

“Truly, right well will you employ,

These things with which you toy,

For she is in need of them today.”

Such words as these none will say,

For none are so true and courteous;

Rather than helping others thus,

Each seeks their own to secure,

Though they need nothing more.’

Lines 4385-4474 Yvain champions Lunete

THUS did they lament their fate,

And my Lord Yvain, as I do state,

Among them all, heard their plaint,

Which was neither false nor faint:

He saw Lunete there, on her knees,

‘He saw Lunete there, on her knees’

The Book of Romance (p132, 1902) - Andrew Lang (1844-1912)

Internet Archive Book Images

In her shift, as the law doth please;

She had already made confession,

Besought God’s mercy for her sins,

And summoned up her punishment.

Yvain, who’d loved her deeply, went

Towards her, raised her to her feet,

And said: ‘Dear maid, where may I meet,

Those who’ve accused you from afar?

Let them come from where’er they are,

And, here and now, do battle with me.’

And she who’d neither sought to see,

Nor look at, him said: ‘Sire, indeed,

You come now in my hour of need,

On God’s behalf, for so it must be!

Those who bore false testimony,

They stand all about me here.

If you’d arrived much later, I fear,

I’d have been but ash and cinder.

But you are here, as my defender,

And may God grant you strength,

In accord with my innocence,

As regards the charge against me.’

The Seneschal listened to this speech,

With his two brothers by his side,

‘Ah, woman, truth averse,’ they cried,

‘But full ready with many a lie!

That knight’s a fool who seeks to die,

On your account, in this affair.

That knight is a sad rascal there,

Who comes now to challenge me,

When he is one, and we are three.

My advice to him is: retreat,

Before your downfall proves complete.’

Yvain replied, now angered quite:

‘Let those flee who fear, sir knight!

I’m not so scared of your three shields,

That without a blow I’d yield.

I would prove a rascal indeed,

Did I the field to you concede,

Body intact, without a wound!

As long as I am whole and sound,

I’ll not flee for all your threats.

But I’d advise you to forget

Your claim now, and free this maid,

Whom you unjustly have waylaid;

She has said, and I believe her,

For on her faith she doth swear,

On peril of her soul, that she

Hath never committed treachery

Against her lady, in word or deed,

Or thought; to all that I accede,

Thus I’ll defend her as best I can,

For innocence will aid a man.

Hear, if you would, the truth, sir knight,

God ever holds to what is right.

For God and Justice they are friends,

And if to me their aid they send,

Then I am in worthy company,

And worthier aid is granted me.’

Then the other foolishly replies

That he may try him in any wise,

As he should please, or as he can,

So long as the lion is banned.

And Yvain replies that the lion

Will not fight as his companion,

And that he needs no other there.

But should the lion attack, beware,

Let him defend himself full well,

For more than that he cannot tell.

‘Whate’er you say,’ said the Seneschal,

‘If your lion you will not call,

And keep it quiet on one side,

You shall no longer here abide.

Be gone at once, and be wise,

For, in this country, all realise

How this girl betrayed her lady;

Tis right that she suffer swiftly

The punishment she doth merit.’

‘Not so, by the Holy Spirit,’

Cried Yvain, who knew the truth.

‘Let God deny me joy, forsooth,

If I should fail to deliver her!’

Then he told the lion to defer,

Retreat, and lie down silently,

And as requested, so did he.

Lines 4475-4532 Yvain fights the Seneschal and his brothers

THE lion withdrew completely;

And the dispute and the parley

Being ended both retreated;

Then all three Yvain greeted,

As he rode towards them slowly,

Not wishing to be beaten wholly,

Or toppled at the very first blow.

Thus keeping his own lance whole

He let the three their lances wield,

Making a target of his shield,

Against which each man broke his lance;

Yvain withdrew, better to advance,

And halted eighty yards away,

But then, not wishing to delay,

Returned to confront them all.

Attacking, he met the Seneschal

Before he ever reached his kin,

Splintering a lance upon him,

Despite the shield, laying him low,

Giving him such a mighty blow,

Long he lay stunned, disarmed,

Without the means to work harm.

And then the two brothers attacked;

With bare blades, they dealt no lack

Of mighty blows, both together,

But greater blows he doth deliver,

For every one of his compares

In power to any two of theirs.

Thus he defends himself so well

They fail to make their strength tell,

Until the Seneschal now recovered

Adds his weight to his two brothers’;

And all three then make their stand,

Thus slowly gaining the upper hand.

The lion, watching Yvain defend,

No longer waits to aid his friend;

Yvain needs him, now or never;

While the ladies, gathered together,

Who are all devoted to Lunete,

Call upon God to help him yet,

Begging Him, most earnestly,

Not to grant those three victory,

Nor let Yvain be killed that day,

Who for her doth enter the fray.

The ladies aid him with their prayers,

The only weapons that are theirs.

And the lion assists also

Such that with its very first blow

It strikes so at the Seneschal,

Who has risen after his fall,

That links fly from his chain mail

Like loose straw blown in a gale;

With such force it bowls him over,

Tearing the flesh from his shoulder,

And all down his left flank beside.

Whatever it touches it tears aside,

So that his innards are laid bare;

While his brothers, vengeance dare.

Lines 4533-4634 Yvain is victorious, and goes to seek his lady

NOW their numbers are both equal,

For the Seneschal’s wound is mortal,

As he twists, and writhes, and claws

Through a wave of blood that pours,

In a crimson stream, from his body.

While he thus did suffer greatly,

The lion now attacked the brothers.

Though Yvain, to deter the creature,

Menaced it with threats and blows,

‘Yvain, to deter the creature, menaced it with threats and blows’

The Book of Romance (p122, 1902) - Andrew Lang (1844-1912)

Internet Archive Book Images

He failed to drive it backwards so.

And the lion doubtless knew,

Its master set no slight value

On its aid, but loved it the more;

So it attacked with greater force,

Till the brothers bent to its blows,

And it was wounded by its foes.

Yvain seeing the lion wounded,

Is pained to the heart, angered

By its treatment, and rightly so;

And in revenge strikes such blows

And presses them so hard that they

Are beaten back, and held at bay;

Till they are so weak defensively,

They throw themselves on his mercy;

Due most to the lion’s fierce attack,

Which had taken them so aback,

Though the beast was sore dismayed,

Wounded all over, by their blades.

Nor for his part was my Lord Yvain

In any the less distress and pain,

With many a wound to his body.

Though for his own self his worry

Is less than for the wounded lion.

And now has he deliverance won

For the maiden, as he has wished,

And the lady has now dismissed

The charge against her, of her grace.

And those are burned in her place,

Who for her had built the pyre.

For tis right and just we require

Those who accuse the innocent

To receive the very punishment

That they themselves pronounce.

Now her joy doth Lunete announce,

Being reconciled with her mistress;

And they enjoy such happiness

As never did any two such before.

And all now offered to their lord,

While they lived, loyal service,

Without recognising him, that is.

Even the lady, she who had got

His heart, and yet knew him not,

Begged him to stay if he pleased

Until he was once more at ease,

And he and his lion recovered.

He replied: ‘Lady, I could never

Remain a moment in this place,

Until I am no more in disgrace

And my lady free of her anger;

That alone can end my labour.’

‘Indeed,’ she said, ‘that troubles me.

That lady must fail in courtesy,

Who shows anger toward you.

She should not close her door to

A knight who is so valorous,

Unless he has proven traitorous.’

‘Lady’ he said, ‘though it hurts me,

What e’er she wishes pleases me;

But speak no more of the matter,

For the reason, or the crime rather,

I will say naught of, but to those

Who know how the affair arose.’

‘Does any know of it but you two?’

‘Yes, truly, lady.’ ‘Well, your name

Fair sir, now tell me that very same,

And then you are quite free to leave.’

‘Quite free, lady? I must say nay,

For I owe more than I can pay.

Yet I ought not to hide, I own,

The name by which I may be known.

Word of the knight of the lion

You may hear, tis of me alone.

By that title I would be called.’

‘By God, fair sir, I cannot recall

That I have e’er seen you before,

Nor heard this name of yours?’

‘Lady, from that you may see,

It is not widely known indeed.’

The lady returned to her theme:

‘Once more, if it doth not seem

Displeasing to you, please stay.’

‘Lady, I’d dare not linger a day,

Unless I knew, of a certainty,

Her goodwill encompassed me.’

‘Then may God grant, fair sir,

That all you endure and suffer,

He of His grace may turn to joy!’

‘Lady, God hear, and thus employ

Such grace!’ he said. Then silently:

‘Lady, tis you that holds the key.

You possess though you know it not

The casket wherein my joy is locked.’

Lines 4635-4674 Yvain departs carrying the lion inside his shield

THEN he departed in great distress,

None knowing who he was, unless

We except Lunete, for she alone

Rode with him some way on her own.

‘She alone, rode with him some way on her own’

The Book of Romance (p10, 1902) - Andrew Lang (1844-1912)

Internet Archive Book Images

Lunete alone kept him company,

And he requested her, frequently,

Not to reveal whom he might be

The champion who’d set her free.

‘Sire,’ she replied, ‘I never would.’

Then he requested that she should

Remember him and strive that he

Be thought of kindly by his lady,

Whene’er, that is, she had the chance.

She says that, in that circumstance,

She will, and she will not forget,

But work for him as loyally yet.

He thanks in her a thousand ways,

Then, pensively, he rides away,

Concerned for his lion which he,

As it cannot walk, must carry.

Of his shield he makes a litter,

Employing moss, fern, and other

Fronds, in which he lays the lion

Just as gently as ever he can,

And carries him half-concealed,

Within the inmost of his shield.

Thus he goes to seek his fate,

Until he stops before the gate

Of a mansion, strong and fair.

Finding it shut, he halted there,

And called, upon which a porter

Opened the gate in short order,

Requiring no second command,

But seized the reins in his hand,

Saying to him: ‘Fair sir, enter,

My master’s greetings I proffer;

May it please you to descend.’

‘A lodging I would welcome, friend,’

Yvain replied, ‘for I’m in need

Of his hospitality, indeed.’

Lines 4675-4702 Yvain and the lion are cured of their wounds

THUS through the gate he passed,

And saw the household, en masse,

Running forward there to meet him,

Help him dismount, and greet him.

On the ground a space they made

For his shield where the lion lay,

Then took his horse by the bridle

And led it quietly to the stable,

While, as was their duty, others

Relieved him of arms and armour.

The master having heard the news

Came, just as soon as he knew,

To greet him there in the court,

And then his lady he had brought,

And his sons and daughters all,

And a host of others, from the hall,

Who offer him lodging, in delight.

They gave him a room, full quiet,

For they saw that he was wounded,

And showed kindness unbounded

By placing the lion at his side,

Who silently did there abide;

And to minister to him two maids

Well versed in surgery, now stayed

By his side, daughters of the lord,

Remaining there till he was cured.

But just how long he was there,

Whether a long or brief affair,

Before he and the lion were well,

And went away, I could not tell.

Lines 4703-4736 The two daughters of the Lord of Blackthorn

BUT, within that time, it appears

The Lord of Blackthorn, old in years,

Was set to have it out with death,

Death so robbing him of breath,

That he was thus obliged to die.

After his death it seems, say I,

That of the lord’s two daughters

The claim was made by the elder

That she would now rule the land

For all the days at her command;

The younger would take no share.

She would go, cried the younger,

To the court of good King Arthur,

And there pursue her claim further.

And when the elder sister saw

The younger would not withdraw

Her rightful claim on the estate

She was in a most dreadful state,

Thinking, if possible, she ought

To be the first to arrive at court.

So she prepared for the journey,

And once equipped did not tarry,

But rode till to the court she came.

Her sister followed, but in vain,

For though after her she chased,

And at full speed she did haste,

The elder had already gained

A hearing with my Lord Gawain,

And he had quickly promised her

That upon which they did confer.

But between them they agreed

If she said aught of it, then he’d

Not take up arms for her again;.

And she swore thus to Gawain.

Lines 4737-4758 The younger daughter arrives at Arthur’s court

NOW the younger arrived at court,

And she was attired in a short

Mantle of scarlet cloth and ermine.

Twas the third day since the Queen

Had returned from the prison where

Maleagant had been holding her,

With many another, in captivity,

And Lancelot, through treachery

In that tower was forced to stay.

And upon that very same day

That the younger came to court

News of the vile Harpin was brought,

That giant, that monstrous felon

Whom the brave knight of the lion

Had mortally wounded and defeated.

In his name, Gawain was greeted

By the nephew, and the niece, who

Told him all that they both knew

Of the knight’s service and prowess

In aiding them in their distress.

And said Gawain knew him well,

Though who he was none could tell.

Lines 4759-4820 The younger daughter requests a champion

OF this the younger was aware,

Such that she knew great despair,

And sadness and deep dejection,

For she’d find scant protection

At the court, and little assistance,

If its finest knight was absent.

She had appealed frequently

And insistently but lovingly

For aid to my Lord Gawain,

Yet he replied: ‘My dear, tis vain

To beg for my involvement there,

For I have at hand another affair,

Which in no way dare I neglect.’

So the maiden left him, to direct

Her steps at once towards the king.

‘King,’ she said, ‘I come seeking,

Counsel, at court, and yet I find

None, and wonder in my mind,

Why I can win no counsel so.

But it would not be right to go,

Without taking my leave of you.

My sister should know, for tis true,

She could obtain by being kind,

Whatever she wished of mine,

But I shall never bow to force,

And lose my inheritance because

Of her; never, while I seek aid.’

‘You speak wisely,’ the king said,

‘And since she is here I advise

And urge and beg her to be wise,

And grant to you what is your right.’

But the elder, sure of that knight

Who was the finest one could see,

Replied: ‘Sire, God punish me

If I ever divest of aught, to her,

Town or castle or glade confer,

Woods or fields, or aught at all.

But if some knight answers her call,

Who e’er he may be, and would fight,

Such that he might assert her right,

Well, let him step forward now.’

‘That is no fair offer, I avow,’

Said the king, ‘if she doth wish

To seek out a champion in this,

Forty days is what she ought

To be awarded by any court.’

Then the elder replied; ‘Sire,

The king makes law as he doth desire,

As he so pleases, and it is good,

It is not for me, it is understood,

To contradict him in any way,

So I must bow to what you say,

And grant her leave, if she so wish.’

The younger says that indeed it is

Her wish, she demands this thing,

Then to God commends the king,

And thus from the court departs,

Thinking to seek in every part

Through all the world, ceaselessly,

For the Knight of the Lion, for he

Devotes himself to bringing aid

To women in need, and afraid.

Lines 4821-4928 The maiden seeks the Knight of the Lion

THUS she entered upon her quest;

Through many a land she progressed,

Without news of him, by dale and hill;

And felt such sorrow that she fell ill.

But from that ill good came to her,

For the house of a friend of hers,

She attained, who loved her well.

Clearly from her face they could tell

That she was sick and ill did fare.

They insisted she rested there,

And when she told them of her plight

Another maid went to seek the knight;

In her place, the quest she entered on,

Sent forth to find where he had gone.

So the one stayed and took her rest,

While the other started on the quest.

Riding alone all day, she wandered

Until the darkness drew upon her.

Night brought her great anxiety

And her ills were doubled indeed;

The heavens oped in a cloudburst

As if God sought to do His worst,

And she there, deep in the woods;

They at night brought her no good.

But worse than the woods at night

Was the rain deepening her plight.

And the path was so poor indeed

That many a time her weary steed

Was steeped, up to its girth, in mud,

Now any maid, alone in a wood,

Would be dismayed without escort

At night, and by bad weather caught.

In such darkness she could not see

Her horse beneath her, so that she

Called to God first, then her mother

Then all the saints, one and another;

And offered up many a prayer

God would lead her to safety there,

And reveal the path from the wood.

While in prayer, she thought she could

Hear a horn-cry, which gave her joy,

For whoe’er that horn did so employ

Might offer her shelter, she bethought,

If she could but find what she sought.

So then she turned towards the sound,

And came to a stretch of paved ground,

And this paved causeway led her on

Towards the cry of the distant horn;

For three times, both loud and clear,

Sounded the horn’s call to her ear.

So she followed the road straight

And travelled, at her quickest gait,

Towards it till she came across,

As she rode on, a wayside cross,

Standing before her, on her right;

And she thought that way might

Lie both the horn and its owner.

So she gave her horse the spur,

Till she came to a bridge and saw

The barbican and the blank walls

Of a castle, of a circular nature.

For she’d arrived, peradventure,

At the castle by following

The sound of that horn calling,

A horn that it appears was blown

By a watchman stationed alone,

On the heights of the castle wall.

When he saw her he gave a call

To greet her, and then descended,

And the key of the gate then did

He take, and oped the gate, and said:

‘Welcome who e’er you be, fair maid,

For tonight you’ll be lodged well’

‘And I ask no more, truth to tell,’

Said the maid; and he showed her in.

After the trouble and the pain

She had encountered that day,

Now happy to find a place to stay,

She enjoyed much comfort there.

After dinner her host addressed her,

And was pleased to enquire, in short,

Where she went and what she sought.

‘I seek a knight in arms whom I’ve

‘Never seen,’ the maid replied,

‘To my knowledge, and never known.

A lion goes with him, and doth own

Him as its master, and they say

That I may trust in him alway.’

‘I bear witness to that,’ he said,

‘For he struck my enemy dead,

The other day, so avenging me;

Before my eyes, and delighting me.

And there tomorrow you may see

Beyond the gate, the mortal body

Of the monstrous giant he slew,

So easily he scarce changed hue.’

‘For God’s sake, sir,’ said the maid,

‘Give me fresh news of him, i’faith,

Whether he lodges here at present,

Or if you know which way he went!’

‘I know not, as God is my witness,

But tomorrow, on the road no less

By which he departed, I’ll start you.’

‘May God,’ she said, ‘lead me to

A place where I’ll have news of him,

For great is my joy if I can find him!’

Lines 4929-4964 The maiden approaches the magic fountain

THUS they conversed, as I have said,

Till the hour came to retire to bed.

When dawn broke the following day

The maiden arose to go her way,

Anxious, not wishing to stay for aught

Till she had found the one she sought.

And the master of that mansion

Arose, and all his companions,

And pointed the road to the shrine,

By the fountain beneath the pine.

Then she promptly hastened away

To the castle, by that straight way;

And when she arrived, within sound

Of it, asked the first folk she found

If they’d at any time had sight

Of the lion and of the knight,

Travelling there in company.

And they told her that they did see

Him conquer three other knights

And in that very place, outright.

And she responded, instantly:

‘For God’s sake hide naught from me,

Since you’ve already spoken freely,

If you know more you must tell me.’

‘No,’ they said, ‘we know no more

Than we have spoken of before.

We know nothing of what became

Of him; if she, for whom he came,

Can give you no further news,

None here can enlighten you,

And if you wish to speak to her,

You need not go much further,

For she’s in prayer to God quite near,

And to that church has gone to hear

The Mass, and has been there so long,

Prolonged must be her orisons.’

Lines 4965-5106 Yvain agrees to champion the younger daughter

WHILE they were in conversation,

Lunete returned from her devotions.

‘Now,’ they cried, ‘you shall meet her.’

So the maiden ran to greet her;

And after greeting one another,

The maiden promptly asked her

For news of the knight she sought.

So Lunete asked to have brought,

And saddled, her own fair palfrey;

She’d keep the maiden company,

To where she’d last had sight,

In a meadow there, of the knight.

The maiden thanked her profusely,

And as soon as Lunete’s palfrey

Had been brought she mounted.

As they rode, Lunete recounted

How she’d been accused of treason

And imprisoned, without reason;

And how the fire had then been lit,

To which they’d have her submit;

And how he’d brought aid indeed

In that, her hour of greatest need.

And speaking thus Lunete led her

Along the road to the mead where

She’d parted from my Lord Yvain.

On reaching that same spot again,

She said to her: ‘Now take this road,

Until you come to a place I know

Were you’ll hear fresher news, if it

Pleases God and the Holy Spirit,

Than I can give to you, in truth.

I know I left him here, forsooth,

But know not where he was bound.

He needed dressings for his wounds,

When he parted thus from me.

I send you after him, you see;

If God wills you’ll find him well,

Tonight, tomorrow, I cannot tell.

Now go; to God I commend you,

For no longer may I ride with you,

Lest my lady’s displeased with me.’

Then the two parted company;

Lunete turned back, the maid rode on

Alone, till she reached the mansion,

Where Yvain sought bed and board,

Until his health was quite restored.

There, before the gate, she sees

Men-at-arms, and knights and ladies,

And the lord of the manse, also.

She greets them, and would know

If they have any news to tell

And can inform her, as well,

Concerning the knight she seeks.

‘What knight?’ they ask, ‘It is he

Whom a lion accompanies, they say.’

‘Fair maid,’ the lord says, ‘by my faith,

He hath parted but now from us.

By eve, if such be your purpose,

And you follow him without delay,

You may overtake him on his way.’

She says: ‘God save me from delay,

But tell me now, Sire, which way

I should follow.’ And he replies:

‘That road, ahead, he took, say I.’

Then they ask her to pass on

Their greetings to him, but she is gone,

Without heeding their courtesy,

Galloping away, at full speed.

Now the time passed all too slow,

It seemed, to her, even though

The palfrey’s pace was fast and good.

Thus she galloped through the mud,

And where the road ran flat and true,

Until the brave knight came in view,

With the lion in his company.

Then, in delight: ‘Thank God!’ cried she.

‘Now I see him who was long hidden!

Well have I sought, as I was bidden.

Yet, if I find him but naught attain,

In meeting him where is the gain?

Little, or nothing, that I can see;

For if he fails to return with me,

Then I have wasted all my pains.’

So saying, she pressed on again,

Such that her palfrey was all a-sweat.

At last she neared him, and they met,

And he replied, to her greeting:

‘God save you, fair maid, in meeting,

And deliver you from grief and woe!’

‘God save you, fair maid, in meeting’

The Book of Romance (p70, 1902) - Andrew Lang (1844-1912)

Internet Archive Book Images

‘And you, sire, who, or I hope so,

Will now deliver me of my task.’

Then she drew near, his aid to ask:

‘Sire, I have long sought for you.

For your renown and worth I knew,

Such that I’ve followed tirelessly

Many a long mile of this country.

So hard I followed, God of his grace

Hath led me to you in this place.

And whatever ill kept me company,

I no longer feel its malaise in me,

Nor complain of it, nor remember.

I feel lightness in every member,

For my sorrow has flown away,

On meeting here with you this day.

The need I speak of is not mine,

For I am sent by one more fine;

A woman nobler, more excellent.

But if her hope in you is spent,

And your renown is traitor to her,

She expects aid from no other.

For through you she seeks to end

Her sister’s suit, and so defend

Her right to her inheritance.

And she desires no other lance,

For none at all can persuade her

That any other knight could aid her.

By securing what is her share,

You would win, in this affair,

Honour, and love, sir knight,

By asserting her lawful right.

She herself was seeking you,

To ask all she hoped of you,

And here would be no other,

Had sickness not detained her,

Forcing her to take to her bed.

Now tell me, if you please,’ she said,

‘Whether you’ll dare to appear,

Or whether you will idle here.’

‘No,’ said he, ‘no man wins praise

By idling away his days.

Nor will I to idleness lend

Myself; I’ll follow you, sweet friend,

Willingly, where’er you please.

And if she has great need of me,

She for whom this knight you sought,

Banish all fear from your thought,

That I might fail in this, my duty.

Now God, of His good grace, grant me

Both the courage and the might

To thus defend her lawful right!’

Lines 5107-5184 The Castle of Ill Adventure

AND so, conversing together,

They ride, till they encounter

The Castle of Ill Adventure.

They’ve no wish then to ride further,

For the day is fast declining.

To the castle they come riding,

And the folk, seeing them come,

Call out to the knight, as one:

‘Ill-come here, sir, ill-come here!

This lodging doth to you appear

That you might suffer ill and shame:

An abbot e’en would swear the same!’

‘Ah, foolish folk and villainous,

Are you so vile and mischievous,

Are you so lacking in all pride;

Why assail me thus?’ he cried.

‘Why? That, you’ll soon discover,

If you advance a little further;

Yet you’ll learn nothing more

Until you do ascend the tower;

So climb you up to the fortress.’

Now doth my Lord Yvain address

The steep; and the folk cry out,

All as one, and loud they shout:

‘Ah! Wretch, where will you climb?

If ever, in life, there was a time

You found aught that brought you woe

And shame, whither you now go

Such, there, will be done to you

You’ll ne’er tell of what ensues.’

‘You folk, lacking honour or pity,

You folk, filled with audacity,

Why must you assail me like this?

What seek you? What is your wish,

That after me you yap this way?’

‘Friend, keep you your anger at bay.’

Cried a woman, wrinkled with age,

Who seemed most courteous and sage.’

‘They mean no harm by what they say,

They are merely warning you away;

And if you grasp what you hear aright,

You’ll not choose to stay the night.

Though they dare not tell you why,

They give fair warning with their cry,

Because they wish to rouse your fear.

And this they do for all who appear,

All who to the tower would climb,

To give them warning in due time.

The custom is that we outside

Grant no lodging, whate’er betide,

To any gentleman riding by,

Who would outside the tower lie.

What happens now be on your head,

None will thwart you, as I have said:

Should you wish it, you may ascend,

But take my advice, and turn again.’

‘Lady,’ said he, ‘were I to take

That path, twould be a dire mistake,

By which I might honour forego,

And furthermore I do not know

What other lodging I could find.’

‘By my faith, tis no concern of mine,’

She said: ‘and now I’ll silent be.

You may go where’er you please.

Nevertheless twould give me joy

Should you return again, my boy,

Without incurring too much shame,

Though tis unlikely,’ said the dame.

‘Lady, God grant your wish,’ said he,

‘In thrall my errant heart holds me,

I must do what my heart desires.’

And so to the gate he now retires,

The lion and maid in company;

And the porter calls full loudly,

Crying: ‘Come, and come apace,

Now are you destined for a place

Where you’ll be lodged with care,

And ill shall be your visit there.’

Lines 5185-5346 The three hundred maidens

THUS the porter made an end,

And hastening then to ascend,

After his ill speech, gave a sigh.

My Lord Yvain, without reply,

Passed straight on, and there he found

A great hall, both fine and sound;

Before it, was a walled courtyard,

By long and pointed stakes marred.

Seated amongst the stakes he saw

Three hundred maidens, and no more,

Upon the diverse cloths there spread;

With golden and with silken thread,

Each embroidered as best she knew.

Yet such was their wretchedness too,

That, hair unbound and loosely clad,

Full poor they looked, humble and sad.

And their garments were torn at best,

About the elbow and the breast,

About their necks the cloth was stale;

Their necks were slender, faces pale

With hunger, and with deprivation.

They looked at him, and he at them,

They bowed their heads low, and wept;

A long while motionless they kept,

Unable to attend to aught,

With their eyes the ground they sought,

So bowed down were they with woe.

When he awhile has viewed them so,

My Lord Yvain then turns about,

Towards the door that leads without,

But now the porter bars the way:

‘Wish not for that,’ he doth say,

‘You may not depart,’ fair master.

‘Now you wish you’d not entered,

Yet, upon my life, you wish in vain,

Before you go you’ll know such shame

More than you can ever have known.

You were not wise to enter though,

When you chose to venture here,

For you shall not depart, I fear.’

‘Nor do I seek to, fair brother,

But by the soul of my dear father,’

Says Lord Yvain, ‘now tell me

Whence came those maids I see,

Weaving cloths of silk and gold?

The work they do is fine, I hold,

Yet it distresses me to see

Them so thin in face and body,

Their skin so pale, and they so sad.

It seems to me if they but had

Everything they might desire,

They would be ladies to admire.’

‘I’ll not tell you,’ says he, ‘go play,

Go find some other who might say.’

‘So shall I, for I can do no more.’

Then he searched and found the door

Into the courtyard where the maids

At their embroidery were arrayed,

Greeted them all, and saw the flow

Of tears that from their eyes so

Poured down, as they did weep,

That their eyes more tears did reap.

Then he said: ‘May God be pleased

To lift from your hearts this grief,

Its cause I know not, and bring joy.’

And one replied: ‘May God employ

His grace, and so hear your prayer!

From you we shall not hide where

Tis we come from, and who we are,

Hoping such brought you from afar.’

‘For that,’ he said, ‘I’m here indeed.’

‘Sire, a great while ago, you see,

The King of the Isle of Maidens,

Went to seek fresh information

From every country, every court,

Until, like a born fool, in short,

He came upon this perilous place,

In an evil hour, for we now face,

We wretched maids, who are here,

The shame and misery and tears

We ourselves have not deserved.

And rest assured you’ll be served

With like shame, and such receive

Unless, ransomed, you may leave.

Regardless of that, twould appear

That our king indeed came here,

Where live two sons of the devil,

And do not think this all a fable,

For he begot them on a woman.

To fight the king was all their plan,

Whose terror was great indeed for he

Was aged but eighteen years, you see;

So they might easily dismember

One like a lamb and just as tender.

Now the king, but a fearful knight,

Escaped from them as best he might,

Swearing an oath that he would pay

Every year, on that very same day,

A tribute to them of thirty maids;

Thus was he freed, if he so paid;

And he swore to them this forfeit

Would last for just as long as it

Was the case that they still lived;

But on the day that they might give

Battle and die, or meet defeat,

He would be quit of it complete,

And all of us would then be free,

And relieved of all our misery,

And all this labour and distress.

We shall never know happiness,

For I spoke folly of this mischance,

Who talked of our deliverance,

We who will never leave this place;

We will weave cloth all our days,

Though we will ne’er be better clad;

We will always be bare and sad,

And ever hunger and ever thirst;

For we are poor, and we are cursed

Never to win ourselves better food.

We have bread, but scarcely good,

A little at morn and less at eve,

For none may earn, you may believe,

By her work, so much as to give

Four pence a pound on which to live,

And that is not enough we’ve found

To buy enough food all round,

For in a week not one shall gain

Twenty shillings despite her pains.

Yet each of us you may be sure

Turns out twenty shillings or more

Of well-sewn work for sale, which

Would any less than a duke enrich!

While we exist in great poverty

Rich from our labour grows he

For whom we thus toil each day.

Much of the night we work away,

And all the day for sordid gain,

For they forever threaten pain

To our bodies whene’er we rest,

And rest we dare not, I confess.

What more do you wish to hear?

All the shame and ill found here,

I could not tell you a fifth of it.

But what angers us most is this,

That we witness the deaths often,

Of armed knights, fine gentlemen,

Who with these two devils do fight.

He pays a high price, doth the knight

Who battles them, as you tomorrow,

Who must fight them to your sorrow

In single combat, willing or no;

Fight, and lose your fair name so,

Against these two known devils.’

‘May God, the true and spiritual,

Defend me,’ said my Lord Yvain,

‘And joy and honour grant you again,

If it is His will that such He’ll do!

Now it seems I must part from you

And seek those who dwell within,

And find what cheer I may win.

‘Go sire, and pray He fortune brings,

Who gives and takes away all things!’

Lines 5347-5456 Yvain receives an initial welcome in the castle

HE went on till he came to the hall,

Where he found no one at all,

Either good or bad, so he,

Passed on with his company,

Till they came to a garden, fair.

None spoke of stabling horses there,

Yet they were stabled readily,

By those who seemed to believe

That they were now theirs to own.

I know not why they thought it so,

For their master was still alive!

Yet the horses were set to thrive,

For they had their oats and hay.

Into the garden he made his way,

With all his company, and they

Saw there a gentleman reclining

On a silk rug, and a maiden reading

To him there, from, I assume,

Some romance, I know not by whom.

And to hear this romance through,

Recline, and gaze, and listen too,

A lady had come, who was her mother,

And a gentleman, who was her father,

For the two of them much enjoyed

Seeing and hearing her thus employed,

For no other child had they between

Them; she was not yet seventeen,

And so lovely, such grace within her,

The God of Love, if he had seen her,

Would have felt obliged to serve her;

Nor would he ever have made her

Love anyone, unless twas he.

He’d have doffed his divinity,

Becoming human, his own heart

Struck by a blow from that cruel dart

The wound from which is healed never,

Except through a treacherous doctor.

For it is wrong if we recover,

Unless treachery we suffer;

Who’s cured by other ministry

Ne’er loved his lover loyally.

Of such a wound I could speak

And still not finish in a week,

If, that is, you wished to list.

Though some indeed would insist,

My tale was merely tedious,

For folk are not now amorous,

Nor do they love as once they did,

And they would rather keep it hid.

But hear now with what courtesy

What manner of hospitality,

My Lord Yvain they did greet.

All of them rose to their feet,

All who in the garden were,

As soon as they saw him there,

Called to him: ‘Fair sir, this way;

With all that God may do or say

May he indeed bless all below,

Both you, and all you love also!’

Mayhap they sought to deceive him,

But with great joy they received him.

And made as if twould greatly please

Should he be lodged all at his ease.

And even the lord’s daughter

Treated him with great honour,

As one should treat a noble guest,

Helped him of his armour divest,

And nor was that the most she did,

For with her own hands she bid

Fair to bathe all his neck and face;

The lord wished that in that place

They might show him every honour;

So they did, and she did offer

A folded shirt from out a chest,

And white leggings, of the best,

Then with needle and thread she

To the shirt attached new sleeves,

Thus clothing him most carefully.

God pray it prove not too costly

All this service and attention!

Over his shirt, I should mention,

She dressed him in a fine surcoat,

With a mantle, up to his throat,

Scarlet and vair, good and new.

She takes such pains to serve him too

He feels embarrassed before her,

But so courteous is the daughter

So open-hearted and debonair,

Little she thought she did there,

Knowing it pleased her mother

To leave no service to another

That might win the knight’s praise.

That night, in as many ways,

He was so well served at dinner,

Those who carried in the platters

Were tired, there were so many.

That night they showed him any

Amount of courtesy; shown to

A comfortable bed, and left to

Rest his weary head, all replete.

And there the lion lay at his feet,

As was its habit so to do.

In the dawn when God renewed

His great light throughout the world,

As He would see all things unfurled,

Who hath all things in His command,

Yvain, once risen, took by the hand

The daughter, and accompanied her

To the chapel, and there they heard

A Mass said for them, as was fit,

To honour there the Holy Spirit.

The End of Part III of Yvain