Chrétien de Troyes

Yvain (Or The Knight of the Lion)

Part I

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2018 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Lines 1-174 Calogrenant is urged to recite a tale, at Arthur’s court

- Lines 175-268 Calogrenant tells of how he came to a wooden tower

- Lines 269-580 Calogrenant’s adventure in the wood

- Lines 581-648 Yvain takes up the challenge

- Lines 649-722 Yvain determines to adventure alone

- Lines 723-746 Yvain departs the court secretly

- Lines 747-906 Yvain repeats the adventure and the fight

- Lines 907-1054 Yvain is trapped in the knight’s palace

- Lines 1055-1172 Yvain is rendered invisible by the ring

- Lines 1173-1342 The dead knight’s wounds bleed

- Lines 1343-1506 Yvain falls in love with the dead knight’s lady

- Lines 1507-1588 The maiden plans to free Yvain

- Lines 1589-1652 The maiden seeks to advise the lady

- Lines 1653-1726 The maiden promotes Yvain’s interests

- Lines 1727-1942 The lady sends for Yvain thinking him at court

Lines 1-174 Calogrenant is urged to recite a tale, at Arthur’s court

ARTHUR of Britain, that true king

Whose worth declares: in everything

Be brave, and courteous, always,

Held royal court, on that feast-day

Of the descent of the Holy Ghost,

That is known to us as Pentecost.

The king was at Carduel in Wales;

After dinner, amid their wassails,

The noble knights took themselves

To wherever the fair damsels,

And fine ladies summoned them.

Some told stories to amuse them,

While others there spoke of Amor,

Of all the anguish and dolour,

And of the great joys, accorded

To the followers of his order,

To which, once rich and strong,

So few disciples now belong

That the order is nigh disgraced,

And Amor himself much abased.

For, once, those lovers among us

Deserved to be called courteous,

Brave, generous and honourable.

But now all that is turned to fable.

Those who know naught of it, say I,

Claim they love, but in that they lie;

True love seems fable to those I cite,

Who boast of love but lack the right.

Yet, to talk of those who once were,

Leave those to whom I now refer;

For worth more is dead courtesy,

To my mind, than live villainy.

Thus I take joy, now, in relating

Things indeed worth the hearing,

About that king of such great fame

That near and far they speak his name,

And, I concur here with the Bretons,

Shall do, as long as worth lives on;

And, through them, we remember,

His worthy knights who forever

Did labour in the court of love.

Yet, that day, wonderment moved

Them, at his rising from among them,

And some were troubled among them,

And on the subject spoke full more,

Since none had e’er seen him before

In mid-feast his apartments enter,

To rest or to sleep in his chamber.

But on this day, upon some whim,

The queen, it seems, detained him,

And he remained so long by her

He forgot himself in slumber.

Now, outside the chamber door,

Were Dodinel and Sagremor,

And there was my lord Gawain,

And nearby my lord Yvain,

And with them Calogrenant,

A handsome knight and elegant,

Who did, with a tale, a hearing claim,

One not to his honour, but his shame.

And as he commenced the story,

The Queen heard him and swiftly

Rising from beside the king, she

Came upon them all so secretly

That before ever she was seen

She was amongst them, I ween;

Calogrenant, but none other,

Rose to his feet to greet her.

Then Kay, who was divisive,

Deadly, sharp, and abrasive,

Cried: ‘By God, Calogrenant

I see you now, bold and gallant;

Indeed, it greatly pleases me

To see you outdo us in courtesy,

And seek to show your excellence,

Since you possess so little sense.

Of course my lady will agree

You exceed us all, as we see,

In boldness, and in courtesy.

Through boldness, mayhap did we

Or sloth, fail to rise; or again

Twas that we did not so deign?

In God’s name, sir, twas not so

But because we did not know

My lady was here till you rose.’

‘Truly, Kay, I must suppose,

On my honour,’ said the Queen,

That you are so full of spleen

You would burst if you could not

Pour out the venom that is your lot.

You’re a tiresome rascal, that I know,

To scorn all your companions so.’

‘Lady, ‘said Kay, ‘if we gain naught

Then indeed, let us not lose aught,

By your presence; I have not said

Aught of which I now stand in dread.

I beg you to speak no more of this.

Neither courtesy nor sense, I wist,

Lies in chasing after vain dispute.

Let us not then maintain pursuit,

Nor any here advance the matter.

But demand you the tale, rather,

So as to quell all such nonsense,

That he was ready to commence.’

At these words, Calogrenant

Prepared to render his account:

‘Sir,’ he said, ‘I care but little

To pursue any such quarrel,

Little it is, and small the prize;

If it pleases you so to despise,

That will never do harm to me.

You have troubled, frequently,

Better and wiser men than I,

My Lord Kay, and them defy,

For such is your custom, I think;

The midden, it will ever stink,

Horseflies bite, and bees buzz,

And so doth a bore torment us.

But I’ll not now begin my story

With due leave from my lady,

For I beg her to ask no more,

Nor this thing that I now abhor

Demand of me, in her mercy.’

‘All those who are here, my lady,’

Said Kay, ‘shall be in your debt,

Who willingly would hear it yet;

But do not ask this thing for me:

By the faith you owe the king, he

Who is your sovereign and mine,

Demand this, for ’twould be fine.’

‘Calogrenant,’ declared the Queen,

‘Ignore all that’s unfair and mean

In this Sir Kay, our Seneschal;

His custom is to speak ill of all,

And not to punish him is best;

I command you, and I request

You bear no anger in your heart

Nor for him cease your fair art,

A thing we would like to hear.

If you desire my favour here,

Begin again, and from the start.’

‘Lady, it will break my heart

To do as you order me to do;

This eye of mine I’d rather lose

Than tell more of my tale today,

If I did not seek your ire to allay;

So I will do what you ask of me

However much it may grieve me.

Who’s pleased to do so, then, attend!

Your heart and ears to me now lend,

For soon it is forgot, the word,

If by the heart it is not heard.

There are those who all they hear

Understand not, though they hear;

They listen with the ears alone,

While the heart is like a stone.

On their ears the words do fall

Like the wind that blows on all,

Yet never for a moment stays

And in an instant speeds away,

Unless the heart is wide awake

And the meaning thus doth take;

For it may seize it when it comes

And capture it and give it room.

The ears are the path whereby

A voice may enter, by and by,

And the heart within the breast

Seize the voice the ears accept.

Now who wishes to hear me

Must lend heart and ears to me,

For I shall not serve you a dream,

A fable, or some lying scheme,

As many another man would do,

But speak of what I know is true.’

Lines 175-268 Calogrenant tells of how he came to a wooden tower

IT chanced that seven years ago,

A lonely traveller on the road,

I was in search of fresh adventure,

Casting my net all at a venture,

Fully-armed, as the truest knight;

And came to a track on my right

Leading into the dense woodland.

The path was bad; on every hand,

Hedged about with thorns and briars.

What trouble it was, and pain entire,

That woodland track, iniquitous!

And for nearly a whole day thus,

I rode along, as best I could,

Till at last I issued from the wood;

That was in Broceliande.

From the forest onto open land

I came, and saw a wooden tower

A Welsh league away, no more,

And a moat, below its palisade,

Deep and wide, that round it lay.

And on the bridge above it stood

The lord of all this tower of wood,

With a moulted falcon at his wrist.

No sooner had I reached its midst,

And saluted him, than he did lend

Me his aid, and helped me descend.

I descended; I could not deny

I would need shelter by and by.

And he declared to me, at once,

More than seven times, if once,

That truly blessed was the way

By which I had come that day.

We passed beyond the bridge and gate

Into the inner courtyard straight.

Midst the court of this kind vavasor,

To whom God owes joy and honour

For all on me he bestowed that night,

Hung a gong, and with never a sight

Of iron or wood, for this I thought:

All of copper the gong was wrought.

And three times then did the master

Strike at the gong with a hammer

He had hung on a post nearby;

And those who were waiting nigh

High in the tower, heard the sound,

And soon descended to the ground

And came out into the yard below.

Some attended my horse, I trow,

Which the master was holding;

While I saw, towards me, coming

A right fair and noble maiden.

And saw, as she came nearer, then,

That she was tall, and slim, and true.

And skilled with my armour too;

She removed it swiftly and well,

And wrapped me in a fine mantle,

Green stuff with peacock feathers.

We were abandoned by the others,

She and I were left alone, quite,

None remaining, to my delight,

For I sought no more than her.

And she led me to sit with her,

In the sweetest mead to be found

And ringed by a wall all round,

There I found her so educated,

So well-spoken and cultivated,

Of such manner and character,

I was delighted to sojourn there,

Never wishing to part from her,

Nor evermore be obliged to stir.

But twilight came eventually,

And my host came seeking me,

Since it was the hour for dinner,

Which meant I could not linger,

So I followed him right away.

Of the dinner I’ll briefly say

That all was as I could wish it,

For the fair maid came to sit

Opposite where I was sitting.

After supper, we were talking;

My host confessed it must be

Who knows how long since he

Had welcomed a knight errant,

And one upon adventure bent,

To whom he’d shelter offered.

After which he then requested,

That as a favour, I promise him

On my return, to lodge with him.

And I replied: ‘Willingly, sir,’

Thinking it shameful to demur.

Lines 269-580 Calogrenant’s adventure in the wood

NOW I was well lodged that night

And saw, with the morning light,

My steed all saddled, for the way,

As I had sought the previous day,

When we had ended our supper.

My kind host, and his fair daughter,

To the Holy Spirit I commended,

Took my leave with none offended,

And departed swiftly as I could.

I’d not gone far, through the wood,

When I came upon, in a clearing,

Some savage bulls, freely roaming,

And sparring, among themselves,

With such load roaring that I fell

Back a little from them, in fear,

For no beast fiercer doth appear,

Nor is more dangerous, than a bull.

A fellow, black as mulberry, full

Hideous, massive beyond measure,

And as thoroughly ugly a creature,

More so than words could express,

I beheld, on a stump, seated at rest,

A mighty club gripped in his hand.

I then approached the fellow, and

Perceived that his head was bigger

Than a horse, or any other creature;

His brow below black tufts of hair,

For more than two spans, was bare;

His ears were mossy and full large,

Like an elephant’s as it doth charge;

His eyebrows thick, his face flat,

With owl’s eyes, nose like a cat,

And jaws like to a wolf, split so,

Teeth, a wild boar’s sharp and yellow;

Beard black and tangled, as for the rest,

His chin seemed merged with his chest,

His backbone long, hunched, twisted.

Propped on his club, he sat and rested,

Dressed in a mighty strange garment

Neither of wool nor of linen blent,

But of two bull or ox hides made,

Hung round his neck, newly flayed.

When toward him I made my way,

The fellow leapt up straight away

Seeing me there, nearing slowly,

I knew not if he would strike me,

Nor whether he’d offer offence,

But I was readying my defence

When I saw him take his stand

On a tree-trunk close at hand,

Straight and tall, and motionless,

Seventeen feet; not a fraction less.

He gazed; never a word did yield,

No more than a beast of the field,

And I assumed he lacked reason,

And could not utter like a man.

Nevertheless I ventured boldly,

Saying to him: ‘Come now, tell me

Whether thou art truly human!’

And he replied: ‘I am a man.’

‘What kind of man? ‘Such as you see;

I am no more than I seem to be.’

‘And what dost thou here; aught good?’

‘I guard the cattle in this wood.’

‘How, by Saint Peter of Rome?

Unless these cattle, as they roam,

Understand human speech, I know

In a wood you’ll not guard them so.’

‘I guard them so well and rightly,

They will scarcely stray from me.’

‘How is that? Come tell me true.’

‘When they see me come in view

They will not dare to move a yard.

For whenever I grip one hard

I give its horns such a wrench

The others from fear do blench,

For my grip is harsh and strong;

Then all around me they throng

As if they were crying mercy:

And none can do this but me,

For if it were another instead,

Once among them, he’d be dead.

So I am master of these beasts,

And now you must tell me at least

What you are and what you seek.’

‘I am,’ said I, ‘a knight, and seek

A thing I cannot find, God wot;

Long have sought it but found it not.’

‘And what is this you seek, say I?’

‘An adventure, to prove thereby

My prowess, and my bravery.

And now I request of you, tell me,

If you know, give me true counsel,

Of some adventure, or some marvel.’

‘Of that,’ said he, ‘you may report

That of adventure I know naught,

Nor have I e’er heard tell of any.

But if you’d wish to go and see

Some way from here, a fountain,

Your return will cost you pain,

If you fail to respect its power.

Close by you’ll find at any hour

A path to lead you there, I say:

Follow it true, on that true way,

If you’d employ your steps aright,

Or else you may end in sad plight;

For, there, full many a path uncoils.

There lies the fountain that boils

Yet colder than marble is maybe.

’Tis shaded by the loveliest tree

That ever was formed by Nature,

And its leaves they last forever,

Never lost in the harshest winter.

An iron basin hangs there ever,

Attached it is to so long a chain

That it will reach to the fountain.

A stone you’ll find, beside this spring

Such as you’ll see but, here’s the thing,

I cannot tell you what, I ween,

For it’s like I have never seen.

On the other side stands a chapel,

Though small ’tis very beautiful.

From the basin take some water,

On the stone the droplets scatter,

Then comes a tempest in the sky,

And every creature hence will fly,

Each stag and doe, fawn and boar,

And not a bird will linger more;

For you will see such lightning fall

Such gales that roar among it all,

That if you turn, and so depart,

If you can that is, by whatever art,

Without great trouble and mischance,

You will be better served, perchance,

Than any knight ever was yet.’

I left the fellow, and soon was set

Upon the path that he did show.

Tierce was almost past, I know,

And it was near to noon, maybe,

When I saw the chapel and the tree.

That tree standing there, tis true,

Was the loveliest pine that grew,

Ever, upon this earth of ours.

Never was there so dense a shower

That even a drop of rain could pass,

Within; all fell without, en masse.

From a branch hung a basin of gold,

Made of the purest metal sold

In any marketplace anywhere;

While the fountain I saw there

Like boiling water it seethed;

The stone was emerald, I believe,

Pierced like a cask all through,

With four rubies beneath it too,

More radiant and a deeper red

Than the sun risen from its bed

And lighting all the eastern sky;

For, know that I would never lie

To you, or speak a word untrue.

The marvel now I wished to view

Of the tempest, and the gales,

Not wise to all that it entailed,

But would have repented though,

Gladly, if I could have done so,

Hearing the pierced stone stir

With the fall of the basin’s water.

But I poured too much, I deem,

For straight I saw the heavens teem.

From far more than fourteen sides,

Blinding my eyes, the lightning rides,

And the clouds let fall, pell-mell,

Rain and hail, and snow as well.

It was so heavy, blew so strong

That I was almost dead and gone,

For the lightning struck all about,

And mighty trees were rooted out.

Know that it did me much dismay,

Until the clouds were snatched away.

For God then showed me such grace

That the tempest vanished apace,

And all the storm winds fell silent,

Not daring to counter God’s intent.

On seeing the air clear and bright

I was filled again with delight,

For joy, as I have noted often,

Causes all pain to be forgotten.

As soon as the storm had passed,

I saw so many birds amassed,

Believe it or not, on the pine,

Not a branch there, thick or fine,

That was not cloaked with birds,

Such that the tree proved lovelier.

For all the birds sang in that tree

So as to meld in harmony,

Yet each was singing its own song,

So that I heard not a single one

Sing the song that another sung.

And I felt joy, their joy among,

Listening to them all sing anew

Until their orisons were through.

I never heard such joyousness,

No other ear could be so blessed

Unless it too were there to hear

What did so please and endear

That in true rapture I was lost.

I stayed thus till I heard a host

Of knights, as it seemed to me,

Full ten at least, approaching me,

Yet all that great noise was made,

By one knight entering the glade.

When I saw that he came alone

On his steed, I caught my own,

And mounted it without delay,

While he still pursued his way

With ill intent, as an eagle flies,

And fierce as a lion, to my eyes.

From as far off as I could hear

His challenge floated to my ear,

Crying: ‘Vassal, you bring me

Shame and harm, with no enmity

Between us; if you would fight

You should challenge me of right,

Or seek the aid of justice before.

Upon my life, you declare war.

But, Sir Vassal, it is my intent

That on you falls the punishment

For all the harm that you dispense;

And around me lies the evidence,

Of my woods, and of their ruin.

His the complaint who falls victim;

And I have reason to complain

For with lightning, wind and rain,

You have driven me from my home.

You bring ruin, and you alone,

Cursed be he who thinks it well,

Upon my woods, and my castle.

You but now made such an attack

That no aid is of use to me, alack,

Men, nor arms, nor defensive wall,

No safety is here for a man at all

Whatever fortress may be his home

Whether of wood or solid stone.

From now on, ’tis war without cease

Between us, neither truce nor peace.’

At these words we rushed together,

While each one himself did cover,

Both grasping our shields full tight.

His steed was fitting for a knight,

His lance true; he, without doubt,

Was a head taller, or thereabout.

Mine then the risk, being smaller

Since he was so much the taller,

And his horse stronger than mine.

Amidst the truth, I know that I’m

But seeking to hide my shame.

The strongest blow I can claim,

I dealt him, giving of my best,

On the top of his shield, I attest,

And struck home with such force,

My lance shattered in its course.

His lance as yet remained whole,

And a heavier and longer pole

Than his lance was, I know not,

For no knight’s lance, God wot,

Not one, so massive, have I seen.

And the knight then struck at me

So hard he knocked me from my steed,

Over the crupper I flew, indeed,

And landed flat upon the ground;

He left me ashamed, I am bound

To say, and without another glance,

Took my horse, and off did prance,

Returning by the way he came:

And I, who scarcely knew my name,

Was left there, in anguished thought.

The fountain’s brink then I sought,

And sat me there awhile, to rest.

As for the knight, I thought it best

Not to pursue him, for fear lest I

Commit some folly by and by.

Besides I knew not where he’d gone.

In the end, my thoughts dwelt on

The promise to my host I’d made

To return to his house in the glade.

As the thought pleased me, so I did.

But of my armour myself I rid,

So as to walk more easily,

And thus returned, shamefacedly.

When I came to my host’s door

I found my host was as before,

Full of the same delight and joy,

That he did previously employ.

I observed not one thing, either

From himself or from his daughter,

To say they welcomed me less,

And the same honour, I confess,

Showed me as the previous night.

And I give thanks, as is but right,

For the honour all did me there.

And, as far as they were aware,

None before had escaped that strife,

But he who went there lost his life,

In that place, from which I came,

Or was taken captive in that same.

So I went, and so returned,

With the fool’s reward I earned.

Now have I told you of my shame,

Nor wish to speak of it again.’

Lines 581-648 Yvain takes up the challenge

‘BY my head’, said my Lord Yvain,

‘You are my own cousin-germane,

And we should love each other well,

Yet I find you foolish not to tell

Me of all this matter long ago.

If I have called you foolish though

I pray that you’ll take no offence,

For, if I win leave, I’ll go thence,

And take revenge for your shame.’

‘This is but an after-dinner game,’

Said Kay, who never went unheard.

‘In a wine-jug there are more words,

Than in a whole barrel of beer.

The cat that’s fed is full of cheer;

After dinner, and without stirring,

Every one of you would be fighting,

Wreaking vengeance on Nur ad-Din!

Are your saddle-bags full within,

And your greaves of steel shining,

And your banners yet unwinding?

Leave you tonight, in God’s name,

Or is it tomorrow, my Lord Yvain?

Tell us now; let us know, dear sir,

When do you go to act the martyr?

We would wish to convey you there.

Never a provost who, in this affair,

Would not, willingly, escort you.

But whate’er may occur, I beg you,

Don’t go without taking leave of us.

And if tonight some ominous

Dream you dream, then, do stay!

‘The Devil take you, my Lord Kay,’

The Queen cried, ‘must your tongue

Forever be running on and on?

Let that tongue of yours be cursed

That forever must speak the worst!

For sure, your tongue does you no

Good, or even worse, in doing so.

All say who hear that tongue of yours:

“That’s the tongue that ever more

Goes speaking ill, may it be damned!”

Your tongue utters ill of every man;

It makes you disliked everywhere.

No greater traitor to you is there

Than it, and know, if it were mine

I would it to some prison consign,

Any man who can’t be reformed

To divine justice should conform,

And be treated as one proven mad.’

‘Certain, my lady, never his bad

Or sad jests anger me,’ said Yvain,

‘Wit, wisdom, and worth, he claims,

Such that in any court, Lord Kay

Will ne’er be mute, but have his say.

For he can reply with courtesy

And good sense to every villainy,

And never has done otherwise.

Tell me if what I speak are lies.

But I have no care to squabble

Or begin some foolish quarrel.

He does not always win the fight

Who at first doth show his might,

But he who his revenge savours.

He should rather fight a stranger

Who would his companions stir.

I would not seem like some cur,

That growls and bites, on whim,

Because some other yaps at him.’

Lines 649-722 Yvain determines to adventure alone

WHILE they thus talked together,

The king emerged from his chamber

Where he’d been awhile dormant,

Sleeping deeply, till this moment.

As soon as the knights saw him,

They leapt to their feet to greet him,

Though he told them to be seated.

He sat by the queen, who greeted

Him with Calogrenant’s story,

Which she retold from memory

Recounting it all, word for word,

Skilled in retelling tales she heard.

The king, who listened willingly,

By his father’s soul swore three

Great oaths; by Uther Pendragon’s

That is, his mother’s, and his son’s,

That he would go see this fountain,

Before the next fortnight was done,

The storm and all the marvels there,

On St John the Baptist’s eve, where

He intended then to spend the night,

And that any of them who might

Wish to view the chapel as well,

Could journey with him to that dell.

Now all the court approved the plan;

The lords and bachelors to a man

Wished to be party to the visit,

Since the king desired to see it.

But whoever was thus delighted

Yet my Lord Yvain felt slighted,

For he had thought to go alone.

He, grieving, to himself made moan,

Now that the king himself would go.

For this, especially, grieved also

That he knew well the encounter

Would fall to my Lord Kay rather

Than him, should Kay so request;

For the king would elect the best;

Or even to my Lord Gawain

Who, perchance, would first lay claim.

A request from either of those two

The king indeed could ne’er refuse;

Yet he would not wait to see,

Not requiring their company,

For to go alone was all his wish

Whether to his joy, or his anguish.

And, whoever might stay behind,

The third day himself would find

In Broceliande, and if he could

He’d seek and take, in that wood,

The narrow path, the harsh way

To the strong castle in the glade,

And find the gentle maiden there

Who was so charming and fair,

And at her side her worthy sire,

Who to grant honour did desire,

Being so true, and well-meaning.

And then the bulls in the clearing,

He’d see, and that giant fellow,

Guarding them; he longed to know

That fellow who was so hefty,

So vast, misshapen, and ugly,

Black as a smith; then he would

Come to the stone, if he but could,

And to the basin, and the fountain,

The tree of birds, and rouse the rain,

And cause the great winds to blow.

But of his purpose none must know,

For of his plan he’d make no boast,

Until from it he received the most

It might grant, of shame or honour;

Only then be it known to others.

Lines 723-746 Yvain departs the court secretly

YVAIN from the court was gone

Without encountering anyone,

Then strode to his lodging house,

And his whole household roused,

Ordering them to saddle his steed.

Then a squire, privy to his needs,

He summoned up, immediately.

‘Come now,’ he said, ‘follow me,

To the yard, and bring my armour;

I’ll leave through that gate yonder,

On the palfrey, but have far to travel,

So ride my charger I’ve had saddled,

And then do you bring him after me,

Thus you can return on the palfrey.

But take good care, I now command,

When any my whereabouts demand,

That you offer them no news of me.

If you do, be sure, of a certainty,

You will have of me nothing good.

‘Sire,’ said he, ‘twill be as it should,

And none will learn aught from me.

Lead on, I’ll follow your palfrey!’

Lines 747-906 Yvain repeats the adventure and the fight

MY Lord Yvain mounts; his plan

To avenge the shame, if he but can

Ere he returns, his cousin garnered.

The squire runs to collect the armour,

The steed, and is mounted straight,

For his master will no longer wait;

Nor doth he lack spare shoes and nails.

Then he follows his master’s trail,

Until he sees him about to descend,

And waiting for him, at the bend

Of a track, far from the road, apart.

His arms and armour he doth cart

To his master, and so equips him.

My Lord Yvain now dismissed him,

And, once armed, made no delay,

But swiftly journeyed on each day;

Among the hills and dales did ride,

Through the forests deep and wide,

Places savage and most strange,

Many a wilderness did range,

Past many a peril, many a narrow,

Till the true path he found to follow,

Full of briars, and many a shadow;

But, once assured of the way to go,

Knowing he’d not wander astray,

He forged ahead along the way,

Nor would he halt until he gained

The pine that shaded the fountain

And saw the stone, knew the gale,

With all its thunder rain and hail.

That night, as you might know,

He had good lodging, though.

And greater grace and honour,

In his host, did he discover

Than he’d garnered from the story,

And a hundred times more beauty

Sense and charm in the maid,

Than Calogrenant had conveyed;

For one cannot rehearse the sum

Of what man or maid may become,

When either is intent on virtue;

And I could ne’er express to you

Nor could the tongue e’er relate

All the honour their deeds create.

My Lord Yvain found, that night,

Good lodging, much to his delight.

Moreover when the next day came

He saw the bulls and the villain,

Who showed him the path to take.

The sign of the cross he did make

A hundred times, viewing that monster,

Marvelling how Nature ever

Had made so ugly a person.

Then made his way to the fountain,

And saw all he had wished to see.

Without resting for a moment, he

Poured the basinful of water

Over the stone; from every quarter

The wind blew, down fell the rain,

As that tempest was roused again.

And when God calmed what stirred,

All the pine was covered with birds,

And sang with joy full marvellous,

Above the fountain perilous.

Before their joyful song had ceased

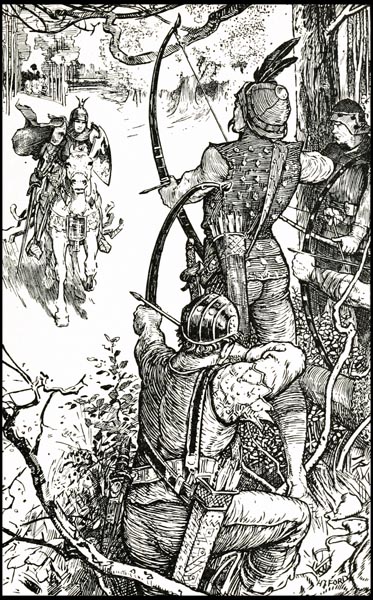

The knight arrived through the trees,

‘The knight arrived through the trees’

The Book of Romance (p168, 1902) - Andrew Lang (1844-1912)

Internet Archive Book Images

Ablaze like a fiery log, with anger,

As if chasing a lusty stag, but louder.

Then they charged, and clashed together,

While the signs, as each struck the other,

Of mortal hatred, they betrayed.

Each gripped a lance, stoutly made,

And did with blows the other assail

Piercing both shield and mail,

While the lances no better did fare

Scattering splinters through the air.

Then each the other doth assault

Attacking fiercely with the sword,

As the blades, in their swordplay,

Cut both their shield-straps away,

Slicing the shields, as they defend

From side to side, and end to end,

Till in the pieces, hanging down,

No useful cover can be found,

For they are now so torn by all

The blows, the bright blades fall

Upon their arms, along their sides,

Across the hips, and more besides.

Perilous now seems their attack,

But neither of them draws back,

Unyielding as two blocks of stone.

Never was such a battle known,

Each intent on the other’s death,

Seeking to waste nor blow nor breath,

But still strike out, as best they may.

On their helmets the blows they lay

Dent the metal, likewise their mail,

The hot blood’s drawn without fail,

And while the mail coats grow hot,

The defence they offer them is not

Much more help to them than cloth.

A lunge at the face reveals their wrath.

Wondrous it was, so fierce and strong

Their blows, the fight could last so long.

But both men were of such great heart

That neither of them would, for aught,

To the other yield a foot of ground,

Till he had dealt him a mortal wound.

Yet both from this did honour obtain:

They did not try, nor would they deign

To harm their mounts, in any way,

Yet remained astride them alway;

Not attacking their horses ever,

With feet planted on earth never;

Which rendered their conflict finer.

At last, my Lord Yvain did hammer

At the knight’s helmet so fiercely,

The blow stunned the knight wholly,

Such that he fainted right away,

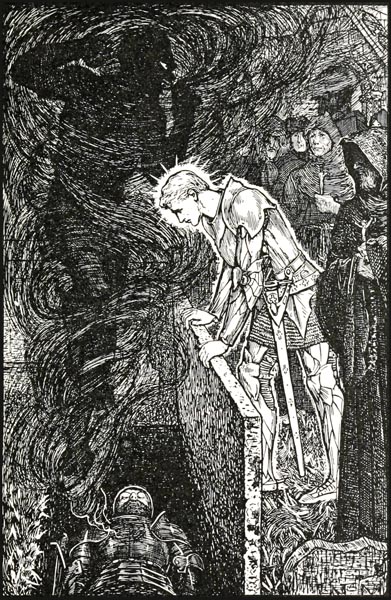

‘The blow stunned the knight wholly, such that he fainted right away’

The Book of Romance (p194, 1902) - Andrew Lang (1844-1912)

Internet Archive Book Images

He never having, until that day,

Felt such a blow; his skull split

With the tremendous force of it.

And now the outflow from it stains

His bright mail with blood and brains;

And he with such pain doth meet,

His heart almost neglects to beat.

He fled then, gasping for breath,

Being nigh wounded to death,

Such that he lacked all defence.

With that thought he rode hence,

Towards his castle, at full speed;

Its drawbridge is lowered at need,

Its entrance gate is opened wide.

Meanwhile my Lord Yvain doth ride,

Spurring his steed on, in his train;

As a gerfalcon stoops on a crane,

Seeing it afar, then drawing near,

Seeking to seize, yet forced to veer,

Thus doth Yvain his victim chase,

So near he has him in his embrace;

Yet cannot quite achieve his prey,

Though so close he hears him pray

And groan aloud in his distress,

Yet ever onwards seeks to press,

While Yvain pursues amain

Yet fears his effort will be in vain,

Unless he takes him alive or dead,

While the words run in his head

My Lord Kay spoke in mockery;

Of his pledge he is not yet free,

The promise made to his cousin,

Nor will they believe his win,

If no proof of it he can show.

The knight leads him onward though

From the drawbridge to the gate;

Both enter, neither dare hesitate;

No man or woman do they meet

As they go swiftly down the street,

Till both together terminate

Their ride before the palace gate.

Lines 907-1054 Yvain is trapped in the knight’s palace

THIS palace gate was high and wide,

Yet the way proved so narrow inside

That two knights astride their steeds

Could not ride there, abreast, indeed

Without encumbrance and great ill,

Nor two men pass each other at will.

This entrance way so narrow it was

A crossbow bolt could scarcely pass.

The gateway could be closed tight

By a mechanism, upon the knight,

With a blade above ready to fall

If but a lever were touched at all;

Beneath the way two levers set

Connected with a portcullis let

Into the stone, its sharpened teeth

Ready to mangle a man beneath;

If he to the lever weight did lend,

Then the portcullis would descend,

And capture or crush with a blow

Whoever was present there below.

And within this narrowest compass,

Lay the path that they must pass,

As a man pursues the beaten trail.

Along this straight and narrow vale,

Rode the knight most knowingly,

And Lord Yvain, most foolishly,

Hurtled after him at full speed,

So closely on his heels indeed

At the gate he seized him behind,

And was most fortunate to find

That bent forward, thus extended,

When the portcullis descended,

He escaped being cut in two,

His horse’s rear legs, on cue,

On the hidden levers treading,

While the iron spikes falling,

Hellish devils, in their course

Struck the saddle and the horse

Behind, severing them cleanly;

But scarce harming, God a mercy,

My Lord Yvain, grazed slightly

Where it touched his back lightly,

Though it severed both his spurs

Behind the heel, the tale avers.

As unhorsed, he fell, dismayed,

The other, wounded by his blade,

Escaped him in this manner;

Far ahead there was another

Gate, like the one left behind;

This gate the knight did find

Open for him, by this he fled,

After which it fell, like lead.

So my Lord Yvain was caught,

Greatly troubled and distraught,

Enclosed there, within this vale

Close studded with gilded nails,

Its stone walls all painted over

With fine work in precious colours.

But nothing gave him such pain

As not knowing where his bane,

The wounded knight, had gone.

The door of a chamber shone

In the wall of the narrow way,

As he stood there in dismay;

Through it, there came a maid,

Who beauty and charm displayed,

Closing it after her again.

When she saw my Lord Yvain

She was also dismayed at first:

‘Surely, sir knight, this is the worst

Time’ she said,’ to enter here.

If any other should appear

You will be done to death,

For my lord breathes his last breath,

And you it is that wrought the deed.

My lady is filled with grief, indeed

And all her people round her cry,

Of sorrow and anger like to die,

They know you are prisoned here

But their sorrow so great appears,

They cannot deal with you as yet.

If they’d hang you by the neck

They’ll be scarcely like to fail,

When these narrows they assail.’

And my Lord Yvain replied,

‘They could never if they tried

Take or kill me, if God so will.’

‘No,’ she cried, ‘for I have still

The power to protect you here.

He’s no man who shows his fear;

So I take you to be full brave

Seeing that you are not dismayed.

And rest assured that I will do

All I can to serve and honour you,

As you would do the same for me.

To the royal court, my lady

Sent me once to carry a message;

I suppose I was not of an age

To be as practised in courtesy

As a maiden at court should be;

But never a knight took the care

To say a single word to me there,

Except for one, now standing here;

But out of kindness to a mere

Maid, you did me honour and service;

And, for your fair honour, in this

Place you shall now win your reward.

I know the name that they accord

To you, for I recognise you again,

You are the son of King Urien,

And go by the name of Yvain,

And you may be sure and certain,

That if you listen to my advice

You’ll ne’er be caught in their vice.

So take now this ring from me,

And return it later, if you please,

Once I shall have delivered you.’

She added further fair words too,

As she handed him the ring:

It would conceal him, this thing

As sapwood by the bark of a tree

Is hidden away, so none can see.

But the ring must be worn aright,

So the stone was hid from sight,

For if the stone was so turned

He need have no more concern.

Even among his enemies

He need not fear their enmity,

For with the ring on his finger

None there would see him linger

However sharp their eye might be,

Any more than the inner tree,

Hid by the bark, showed plain.

All this pleased my Lord Yvain.

When her advice was complete,

She led him to a niche, its seat

Covered with a quilt more fair

Than had the Duke of Austria;

There she said that if he wished

To dine, she’d bring him a dish

Or two, he accepting her offer.

She sped quickly to her chamber,

And returned as swift as thought,

And a roasted fowl she brought,

And a cake and a napkin appear,

And wine then of a vintage year,

A full jar, capped by a drinking cup,

And last she invited him to sup.

And he who was in need of food,

Ate and drank, and found it good.

Lines 1055-1172 Yvain is rendered invisible by the ring

BY the time he’d finished eating,

The people within were stirring,

Searching for the knight, for they

Wished to avenge their lord that day,

Whom they’d laid now on his bier.

The maid said to him: ‘Do you hear,

My friend, all now come seeking you;

And a great noise and stir doth brew;

But no matter who comes and goes,

Move you not, nor the noise oppose,

For they will never find you, sir,

If from this seat you do not stir;

Soon you will see this place full

Of angry and ill-disposed people,

Who will expect to find you here.

This very way they’ll bring the bier

To bury his body on this day;

And they will begin to assay

The paving, walls, and this seat.

Such will prove a joy complete

To a knight who lacks all fear,

Watching them, searching near,

Yet blindly and in vain alway,

So discomfited, and all astray,

They’ll be awash with anger.

But here I can stay no longer,

Thus I’ll seek no more to say,

But thank God who, this very day

Has brought me to the only place

Where I might serve your grace,

As I so greatly wished to do.’

Then the maid vanished from view.

Even before she turned away,

The host were all making their way,

From beyond the gates, toward

The place, gripping club and sword;

Nearer and neared they pressed,

Hostile and angry in their quest,

And found the rear of his steed

Beyond the portcullis. Indeed

They also thought now to find

With the gate full open, confined

Within, the murderer they sought.

And so they lifted that iron port,

Which had brought a sudden end

To the lives of a vast host of men;

And as the levers were now unset,

There remained no obstacle as yet,

So they passed the gate two abreast.

There they discovered all the rest

Of Yvain’s charger that had died,

But never a searching eye espied

My Lord Yvain, silent and still,

Whom they gladly sought to kill.

Yet he could see them, in their rage,

Besides themselves, all engaged

In calling out: ‘How can this be?

Not one opening can we see,

By which a living being might

Flee, larger than a bird in flight,

A squirrel, marmot or another

Kind of similar small creature.

The gate’s a grid of iron bars,

And descended, where we are,

As soon as the master passed by.

Dead or alive, the man is nigh,

Since there’s no sign of him outside.

More than half of his saddle lies

Here within, as we all can see,

But nothing of the man, yet he

Has left these mangled spurs behind,

Sheared at the heel, for us to find.

Come, all this talking is in vain,

Let us look everywhere again,

He must be here still, I believe,

Or we by enchantment deceived,

Or evil spirits whisked him away.’

Thus in a rage they make survey,

Seeking him all about the place.

About the stone walls they race,

Looking on and under the seats.

And yet my Lord Yvain’s retreat

Remained free of all their blows,

Thus he remained unbeaten, though,

They thrashed around sufficiently,

And made as much noise as can be,

Laying about them with their clubs,

As a blind man pounds on his tub

Unable to see all the things inside.

As they were hunting, far and wide

And under the seats, uselessly

There entered the loveliest lady,

That any mortal man hath seen.

So fair a Christian dame, I mean,

Has ne’er been spoken of, although

She was nigh mad with sorrow,

As if seeking the means to die.

And suddenly she gave a cry,

So loud no cry could be louder,

Then fell forward with a shudder,

And when roused from her faint,

Like a madwoman made plaint,

Clawing her face in deep despair

And tearing fiercely at her hair;

She tore at her hair and her clothes,

And, at every step, fell then rose.

Nor was there any comfort here,

Forced to view her husband’s bier

Carried before her, and him dead,

She could no more be comforted;

Thus she cried loudly for her loss.

The holy water and the cross

And the tapers before him went,

Borne by nuns from the convent,

And the missal and the censers,

And the priests to mutter there

The absolution of the dead,

At the poor soul’s feet and head.

Lines 1173-1342 The dead knight’s wounds bleed

MY Lord Yvain heard the cries

Of a sorrow none could realise

In words nor could e’er describe

To see penned by some scribe.

Thus the sad procession passed,

But a large crowd were massed

In the space around the bier,

For warm crimson blood appeared

Trickling from the dead man’s wounds;

Thus the note of justice sounds,

Declaring present, without fail,

One whose actions had entailed

The dead man’s death and defeat.

Thus, with their quest incomplete,

They searched again and again,

Till all of them were weary, drained

By all of this trouble and toil

Created by their fresh turmoil,

On seeing the warm crimson blood,

That from the corpse did flood.

And my Lord Yvain, he too

Was well-nigh beaten black and blue,

Yet did not stir, while the crowd

All took to wondering aloud

As to why those drops were shed,

That blood that trickled from the dead,

For they’d found naught, and cried:

‘The murderer is still here, inside,

And yet no sign of him we see,

Here, then, is some strange devilry.’

At this the lady felt such pain

She fell in deathly faint again,

Then, as if she’d lost her mind,

Cried: God, why cannot they find

My good lord’s killer, that traitor,

That vicious unknown murderer?

Good? The best of all good men!

I know none other I may blame,

For God, yours will be the fault,

If you let such escape this vault,

For you are hiding him from view.

Aught so strange none ever knew,

Nor such a wrong as you do me,

In not permitting me to see

One who must be lurking here.

Well may I say, if he is near,

That some phantom from hell,

Among us, has cast its spell.

A dire enemy of some kind.

He’s a coward, to my mind,

And great cowardice he shows,

For cowardice we must suppose

In one so fearful of appearing.

A phantom is a cowardly thing.

Yet why so cowardly towards me,

When with my lord you made free?

A vain thing, and an empty thing,

Why are you not a captive being?

Why can I not grasp you now?

And how could it be, I trow,

That you could kill my lord

Unless treachery were abroad?

I doubt my lord would e’er have been

Defeated, if your face he’d seen.

Nor God nor man has met, I know,

His like, or could his equal show,

In this world now; if you indeed

Were mortal, both in form and deed,

With my lord you’d ne’er have dared

To fight, for none with him compared.’

Thus with herself she doth debate,

Thus she struggles with her fate,

Thus she exhausts herself anon,

And the people with her move on,

Showing the great grief felt by all,

As they bear the corpse to its burial.

After their efforts the crowd now rest,

Exhausted by their fruitless quest,

And leave off, in their weariness,

A search that brought no success,

In finding the miscreant, at least.

And now the nuns and the priests,

Having ended the funeral service,

All leave the church, and with this

Are on their way to the sepulchre.

But to all this not a moment’s care

Doth the maid in the chamber give;

My Lord Yvain her thoughts are with;

And swiftly she runs to him now

And says: ‘Fair sir, all that crowd,

Searching for you, are now at rest,

Having raised no small tempest,

And nosed about in every corner,

More closely than a setter ever

Searched for a partridge or a quail;

Fear then was yours, without fail.’

‘By my faith,’ said he, ‘you say true.

I never felt such fear; but a view,

Through some opening, would I

Willingly have as it goes by,

If such were possible of course,

Of the procession and the corpse.’

Yet he’s no interest to mention

In the corpse or the procession,

He’d gladly see them go up in sparks,

And happily pay a thousand marks.

A thousand marks? By God, three!

He speaks of them, but tis the lady,

That’s where his true interest lies.

The maiden lets him feast his eyes,

He, from a little window, gazing,

She, as best she can, repaying

Him for his display of honour.

From this window down upon her,

The lady that is, my Lord Yvain

Spies, as she cries aloud, in pain:

‘On your soul may God have mercy,

My fair lord, for none did see

A knight there in the saddle who,

In any manner, equalled you.

My dear lord, there was no other

Who might rival you in honour,

In courtesy, or chivalry;

Your friend was generosity,

And courage your companion.

So may your soul now make one

Among the saints, my fair sire!’

And then she tore at her attire

And all she laid her hands upon.

A hard thing when said and done

It was then for my Lord Yvain

Not to run, and her hands restrain.

But the maiden at first requested,

Then begged and, finally, insisted,

Though courteously and with grace,

That he not, rashly, show his face;

‘Here, all is well,’ said the maiden,

‘So move you not, for any reason,

Till all their sorrow has abated.

And all the turmoil they created,

For presently they will depart.

If you take my advice to heart,

And can restrain yourself, I say,

Good things may come your way.

Tis best if you are seated here,

And watch those who may appear,

As they pass, whom you can view,

While they can see naught of you,

In that there is great advantage.

But take care to commit no outrage,

For he who fails in self-restraint,

And gives good reason for complaint,

When tis neither the time nor place,

Folly, not courage, doth embrace.

Take care that your foolish thought

To foolish deeds doth ne’er resort.

The wise their foolish thoughts do hide,

And see their wiser thoughts applied.

So take care not to risk your head,

But dwell among the wise instead.

Your head will ne’er win a ransom;

Let self be your consideration,

And from all my good counsel learn;

Rest quietly here, till I return,

For I must now join the throng,

I have lingered here too long,

And I fear they must suspect me

If they now should fail to see me

Mingling there with all the rest,

And it would harm me, I confess.’

Lines 1343-1506 Yvain falls in love with the dead knight’s lady

SHE then departs, while he remains

With naught to show for all his pains.

He’s loath to see the corpse interred,

When he has naught but his own word

As evidence to prove aright

That he subdued and slew the knight,

Lacking a witness or guarantor

He can present on reaching court.

‘I’ll meet with scorn and mockery,

For Kay is spiteful, and fell is he,

Full of quips, scattered at whim;

I shall ne’er have peace from him.

He’ll be forever laughing at me,

With his taunts and his mockery,

Just as he did the other day.’

For the taunts from my Lord Kay

Still have power to wound his heart.

But Love a fresh quarry doth start;

Wild in the chase, Love hunts anew,

Stirring Yvain through and through,

And seizes on the prey wholly,

His heart snatched by his enemy.

He loves her who hates him most.

And the lady has avenged the loss

Of her lord, though unknowingly,

A vengeance far greater than she

Could ever have wrought unless

Love helped her to her success,

Who took him softly, by surprise,

The heart struck through the eyes,

A wound that longer doth endure

Than any dealt by lance or sword.

A sword-cut is soon made sound

Once a physician treats the wound,

But love’s wound is worse I fear

Whene’er the physician is near.

Such the wound of my Lord Yvain,

Of which he’ll ne’er be healed again,

For Love now is ensconced within.

All those places he once dwelt in,

Love abandons, and lives there,

Nor lodging nor host doth prefer

Above this one, and is most wise

To leave the hovel where he lies,

And not some other lodging seek,

Who often haunts dire hostelries.

Shame it is that Love doth such,

And seeks vile places overmuch,

Conducts himself in so ill a manner

Choosing places lacking honour,

Ever the lowliest ones, to rest,

Just as readily as the best.

But here he is most welcome, for

He will be shown great honour;

In such a place tis well to stay.

Love should always act this way,

Who is of so noble a nature

That it is strange such a creature

Will lie where shame is, and harm.

He is like one who spreads his balm

Over the embers, amongst the ash,

Hates honour, and loves the brash,

Blending sugar with agrimony,

Mixing acrid soot with honey.

Yet this time he hath not done so

But lodged nobly, here where no

Man can reproach him, instead.

When they have buried the dead,

The crowd of people go their way.

And not a clerk or sergeant stays

Nor any lady, but only she,

Who doth not hide her misery.

But she alone remains behind,

Wrings her hands, un-resigned,

Clutches her throat, beats her palms,

Or from her psalter reads a psalm,

A psalter illumined in gold.

All the while Yvain doth hold

His position, and gazes at her,

And the more that he regards her

The more he loves her, in delight.

He only wishes that she might

Cease her weeping, leave her book,

And yield him but a word or look.

Love has brought about this longing

There, at the window, Love found him.

Yet of his wish he now despairs,

For he neither thinks, nor dares

To hope, it can be realised,

And says: ‘A fool I am, unwise

To wish for that which cannot be;

Her lord met his death through me,

And yet I’d see us reconciled!

By God, I know less than a child,

If I know not she hates me now

More than anything; yet, I trow,

That I say ‘now’ shows wisdom,

For though she has good reason

A woman is of more than one mind,

And her mood now I hope to find

Altered, and alter it will, I’ll dare

To say, so I’d be mad to despair;

And may God grant it alters soon,

Since to be her slave I’m doomed

Always, for such is Love’s desire.

Whoever’s heart does not beat higher

When Love appears to him, then he

Commits a treason and felony.

I say to him, and let all men hear,

That he deserves no joy or cheer.

And yet of that say naught to me,

Since I must love my enemy,

As indeed I must hate her not

Or to betray Love were my lot;

I must love as he doth intend.

Should she then call me friend?

Yes, truly, for her love I’d claim.

And I thus call myself the same,

Though she hate me, as of right,

Since I killed her beloved knight.

Must I then prove her enemy?

No, her friend, of a certainty,

For I ne’er wished so for love, I own;

At her lovely tresses, I make moan;

Brighter than gold shines each tress;

I fill with anguish and distress,

Seeing her at those tresses tear;

And none can staunch the tears there;

The tears that from her eyes do flow.

And all these things distress me so!

Although they are filled with tears,

Of which an endless stream appears,

Never were eyes so beautiful,

And her tears render my eyes full;

Nor aught causes me such distress

As her face, that her nails address;

Such treatment it has not merited;

I ne’er saw a face so finely tinted,

So fresh, or so delicately formed.

It pierces my heart to see it harmed.

And how she clutches at her throat!

Surely she does to herself the most

Hurt that any poor woman could do,

And yet no crystal or glass, tis true,

Is as smooth, or e’er as lovely,

As her throat, in all its beauty.

God! Why must she wound herself so?

Wring her hands, and deal fresh blows

To her breast thus, and scar her body?

Would she not be a wonder to see,

If she was filled with happiness,

When she is so lovely in distress?

Yes, in truth, for I would swear,

That never has Nature anywhere

So outdone her own art, for she

Has passed beyond the boundary

Of aught, I think, she ever wrought.

How could such beauty be sought?

Its presence here, how understand?

God made her, with His naked hand,

That Nature might look on amazed.

For all her effort she would waste,

Wishing to forge her likeness here,

Since she could ne’er create her peer.

Not God Himself, were he to try,

Could know, tis my belief say I,

How to create her likeness again,

Whatever heights He might attain.’

Lines 1507-1588 The maiden plans to free Yvain

THUS my Lord Yvain spied upon

She whom grief had nigh undone;

Nor may it ever again occur

That some man held prisoner,

Should love in so strange a manner,

That he is unable to speak to her

On his own behalf or another do so.

So he watched there, at the window,

Until he saw the lady depart,

While the others, for their part,

Lowered the twin portcullises.

Another might have felt distress,

One who preferred deliverance,

To long imprisonment, perchance,

But he was otherwise disposed,

Careless of gates, open or closed.

He’d not have departed, certainly,

If the passage had been left free,

Unless she’d granted him leave,

And her pardon he’d received,

Freely, for the death of her lord;

Then indeed he might go abroad,

Whom Honour and Shame detain,

On either hand him to arraign.

For he would be ashamed to leave,

Since none at court would believe

All the outcome of his adventure.

And in addition there was the lure

Of a further sighting of the lady.

If that were granted, and that only!

So captivity gives him scant concern.

He would rather die there than return.

But now the maiden doth reappear,

Wishing to offer him good cheer,

And company, and provide solace,

And fetch and carry to that place

Whatever was needful he desired.

But she found him pensive, tired

By a longing that caused him pain,

And said to him: ‘My Lord Yvain,

How has it gone with you this day?’

‘I spent the time in a pleasant way.’

‘Pleasant? How can that be true?

How may one hunted, such as you,

Spend his time thus, pleasantly,

Unless his death he desires to see?’

‘Surely,’ he said, ‘my sweet friend,

I have no desire to meet my end,

What I saw has pleased me though,

And, God’s my witness, still does so,

And will please me, I know, forever.’

‘Now you may leave all that bother,’

She said: ‘For indeed I know well

Where such words lead; let me tell

You now, I’m no foolish innocent,

Ignorant of what those words meant.

But you come along now, with me,

For I shall find a way, presently,

To release you from this prison.

You shall soon have your freedom.’

And he replied: ‘Be certain I

Will not depart, though here I die,

Like a vile thief and in secret.

When all the people are met,

In the narrow way outside,

Then I can go, and need not hide,

Rather than leave here secretly.’

After these words then doth he

Follow her to the little chamber.

And the maiden, kindly as ever,

Seeking to serve, doth dispense

All there, for his convenience,

Everything that he might need.

And, as she does, reflects indeed,

On all that he had told her before,

All his delight with what he saw,

When they sought for him outside,

Intent on ensuring that he died.

Lines 1589-1652 The maiden seeks to advise the lady

THE maid was in such good standing

With the lady that there was nothing

She could not say to her, without

Regard to how it might turn out,

For she was her close companion.

Why then not give of her opinion,

In order to bring comfort to her,

If it might redound to her honour?

At first she says to her, privately:

‘My lady, it is a wonder to me

To see you so wild with grief.

Tis surely not, lady, your belief

You’ll recover your lord by sighs?’

‘No, I wished rather,’ she replies,

‘To die thus, of grief and sorrow ’

‘But why?’ ‘So that I might follow.’

‘Follow? Why may God defend you,

And as fine a lord yet send you

As is consistent with His might.’

‘What mischief is this you cite?

He could not send me one so fine.’

‘A finer, if you’ll make him thine,

He shall send you, as I will prove.’

‘Be gone, there is none so, to love.’

‘Such there is, if you wish, today.

For tell me now, if you can say,

Who it is will defend your land

When King Arthur is at hand,

Who in a week we’ll see riding

To the stone beside the spring?

You have warning of his intent,

For the Demoiselle Sauvage sent

Letters to you, to that effect;

Firm action now will you reject!

You should be taking counsel how

You might defend your fountain now.

And yet your tears you will not stay!

Now you ought not to delay,

For all the knights you can show

Are worth less, as well you know,

Than a solitary chambermaid:

If it please you, my lady,’ says the maid,

‘The best of them will never wield

To any purpose a lance or shield.

Of cowards you have many here,

Who are scarce brave enough I fear

Even to dare to mount a horse;

And the king comes in such force

He will seize all, and none defend.’

The lady knows it, and doth attend,

Aware that this counsel is sincere,

But to a foolishness doth adhere,

That is present in other women,

And seen in almost all of them,

Who of folly themselves accuse,

And what they truly wish, refuse.

‘Be gone,’ she said, ‘Spare me pain!

If I hear you speak of this again,

You will suffer, except you flee,

So greatly your words weary me.’

‘Well, God be praised, then, Madame,

Tis plain that you are a woman;

Who is angered if she hears

Good advice, when such appears.’

Lines 1653-1726 The maiden promotes Yvain’s interests

THEN the maiden went her way,

With the lady, having had her say,

Thinking she might be in error:

Wishing she could know moreover,

How, in truth, the maiden might

Show there lived a better knight

Than her lord had proved to be.

She’d listen now, and willingly,

But had forbidden her to speak,

No more advice could she seek,

Until the maid appeared again,

Whom no stricture could contain,

For she ran on in like manner:

‘Oh my lady must you rather

Choose then to die of grief?

From modesty, tis my belief

And shame you should desist,

For tis not seemly, in the least,

To lament your lord so long.

Remember to whom you belong,

Your people and your noble birth,

Think you all virtue and all worth

Have died together with your lord?

There are a hundred knights abroad,

As good or better, this day, say I.’

‘God confound you, if you lie!

Come name me but a single one

Thought to be as fine a man,

As my lord was all his days.’

‘If I were to sound the praise

Of such a one, you’d be angry,

And in less esteem hold me.’

‘I assure you, truly, I will not.’

‘Then may it brighten your lot,

And good come to you always,

That you let me sound his praise;

May God incline to your wish!

I see no reason to hide all this,

For not a soul’s listening to us.

Doubtless I may appear audacious,

But I will say how it seems to me:

Now when two knights, in chivalry,

Meet together, armed for the fight,

Whom do you think the better knight,

Should the one defeat the other?

As for me, I’d honour the victor

With the prize. Whom would you?’

‘It seems what you have in view

Is to entrap me with your words.’

‘By my faith, truth will be heard,

And my words shall prove true,

For, indeed, I shall prove to you

That much the better man is he

Who slew your lord than was he:

He undid your lord, then pursued

Him furiously, and what ensued

Was that he was then imprisoned.’

‘Now, hear the word of unreason,’

Cried the lady, ‘the wildest ever.

Be gone, ill spirit, and forever.

Be gone, you foolish, tiresome girl.

Never such vain invective hurl,

Nor show yourself here, again,

Or speak out in defence of him.’

‘Indeed, my lady, I well knew

I should earn no thanks from you.

And I said as much ere I began.

Yet you declared, for so it ran,

That you would reveal no anger,

Nor think the less of me, ever.

Badly your promise you keep;

For your anger I surely reap,

And all your ire on me is spent,

Who lose, in failing to be silent.’

Lines 1727-1942 The lady sends for Yvain thinking him at court

THEN she returns to that chamber

Where my Lord Yvain awaits her,

Which has concealed him with ease.

But to him naught now doth please,

For the lady he can no longer see.

He hears not, and pays no heed,

To the news that the maiden tells.

And, all night, the lady as well

Is in a like state of distress,

Thinking, in her unhappiness,

Of how to defend the fountain,

And repenting of her action

In blaming the maiden who

She had treated harshly too,

For she is now perfectly sure

That never, for any reward

Nor for any love she bore him,

Would the maid have spoken of him;

And that she loves her lady more,

Nor would bring her shame, or

Annoy, or ill advice intend.

For she is too much her friend.

Thus the lady is quite altered,

And as for her she has insulted,

She fears the maid will never

With a true devotion love her;

And he whom she denied, she

Now pardons, and most sincerely,

And with right, and with reason,

For he has done her no wrong.

Thus she argues as if he were

Now standing there before her;

Yet with herself debates, say I:

‘Come,’ she says, ‘can you deny,

That tis through you my lord died?

‘That,’ says he, ‘I’ve ne’er denied,

And yes, I slew him.’ ‘Why? Tell me,

Was this thing done to injure me,

Out of hatred perhaps, or spite?’

‘May death hound me without respite,

If I’ve done aught to injure you.’

‘Then you’ve done me no wrong, tis true,

Nor him, for to slay you he would

Have sought, and done so if he could.

As regards this, it seems, sir knight,

I judged well, and have judged aright.’

So she proves that her own opinion

Shows sense, and justice, and reason:

And to hate him would not be wise;

Thus what she wishes she justifies,

And lights a fire within by the same

Means which, like a bush when flame

Is set beneath it, smokes on and on

Till stirred a little or breathed upon.

If the maiden came to her now,

She’d win the argument, I trow,

For which reproach she’d earned,

And by it had been badly burned.

And return she did, with the day,

Commencing again, in a like way,

From the point she had reached;

Again, to the lady, she preached,

Who knew she had acted wrongly

In attacking the maid so strongly.

Now she wished to make amends

And asked, now they were friends,

His name, nature, and ancestry,

Wise now in her humility,

Saying: ‘I would cry you mercy,

In that I spoke so foolishly,

And hurt you, scorning, in my pride,

Advice that must not be denied.

But tell me now, all you know

Of the knight whom you have so

Praised to me, for I beg of thee,

What man is he, of what family?

If he is of such who might attain

Me, then the lord of my domain

I shall make him, I promise you,

If he, that is, will wed me too.

But he must act in such a way

None can reproach me and say:

‘There, is a lady who has wed

One by whom her lord is dead.’

‘In God’s name, lady, so will he;

This knight is of high nobility,

More so than any, in the bible,

That issued from the line of Abel.

‘How is he named?’ ‘My Lord Yvain.’

‘By my faith, he is no mere thane,

But, as I know, is of noblemen,

If he’s the son of King Urien.’

‘Indeed, my lady, you speak true.’

‘And when shall we see him too?’

‘In five days’ time.’ ‘Tis too long,

I wish he were already among

Us, say tomorrow, or tonight.’

‘Lady, not even a bird in flight

Could fly so far in a single day,

But I’ll send a squire without delay,

One who shall travel right swiftly,

And by tomorrow night may be

Arrived at King Arthur’s court;

At least, my lady, tis my thought

That is the place where he will be.’

‘This is too slow, it seems to me.

The days are long; tell him that he

Must be back by tomorrow eve,

And that he must brook no delay

But swiftly hasten on his way,

Swifter than he has ever done.

Two days journey he’ll make in one,

If he tries his hardest, and then

The moon shines bright again,

So let him turn night into day,

And when he returns I’ll repay

Him with whatever he might wish.’

‘Leave me then to take care of this,

And you will find Yvain is here,

As soon as ever he can appear.

Meanwhile your people command,

And of them counsel demand

Regarding the coming of the king.

To maintain that customary thing,

The sole defence of your fountain,

You must seek their counsel again;

Yet none will show himself so bold

As to boast he will there uphold

Its sole defence; then you may say

That you must wed, straight away;

A certain knight doth seek your hand,

Most suitable; they must understand

That you’ll not wed if they disagree.

And then the outcome you will see.

I know they are such cowards all,

That if on another man should fall

A burden far too heavy for them,

At your feet they will fall again,

And offer up their thanks to you,

For what’s beyond their power to do.

For the man who fears his shadow,

Will, gladly, if he can, forego

Any encounter with lance or spear,

‘The man who fears his shadow will, gladly, if he can, forego any encounter with lance or spear’

The Book of Romance (p96, 1902) - Andrew Lang (1844-1912)

Internet Archive Book Images

For that’s a game that cowards fear.’

‘By my faith,’ the lady replied,

‘Such is my wish; I so decide.

Indeed, I had already thought

Of this plan that you have wrought,

And so that is what we will do.

Why linger here? Be off with you,

Whilst my people I’m gathering.’

And when they finished speaking,

The maid feigned to send a man

To seek Yvain in his own land.

Meanwhile, each day she sees that he

Bathes and grooms himself, while she

Prepares for him robes of crimson,

Of good cloth, fine as any person’s,

New, and lined throughout with vair.

There is nothing that he needs there

She fails to bring, his body to deck.

For a gold clasp gleams, at his neck,

Ornamented with precious stones,

Such lend grace to a man, I own,

And a belt and a wallet made

Of some kind of rich brocade.

She fits him out handsomely,

And then goes to tell her lady

That the messenger has returned,

And his reward has truly earned.

‘So,’ she cries, ‘when doth he appear,

Your Lord Yvain? ‘He’s already here.’

‘Already here!’ Bring him to me,

Secretly, then, and in privacy,

For on me now no others attend;

And let no other this way wend,

There is no need here for a fourth.’

At this the maiden doth go forth,

And returns to her guest, apace,

But doth not reveal, in her face,

The joy that in her heart arose.

But feigns that her lady knows

She has concealed him somewhere.

And says to him: ‘By God, fair sir,

There is no point in hiding now.

The thing’s so widely known, I trow

That even my lady has heard.

She reproaches me, with every word,

And doubtless will blame me more;

And yet this she says, to reassure,

That I may still bring you before her,

Without harm, or risk, or danger.

No harm will come to you, I feel,

Except one thing I must reveal,

Or I’d commit an act of treason,

She’ll wish to keep you in prison.’

‘That,’ he said, ‘indeed, I’d wish,

Nor will it harm me in the least,

For in such a prison I long to be.’

‘And, by this right hand you see,

So you shall! But, swiftly, come,

And my advice is this, in sum,

You must act humbly before her;

Thus captivity will prove easier.

And as for that, feel no dismay,

I think perhaps that prison may

Not seem too tiresome to you.’

Thus the maid leads him on anew,

Now alarming, now reassuring,

Speaking, as onward they are stealing,

Of the prison to which he goes;

For love is a prison, God knows,

And they are right who so claim,

For all who love do seek the same.

The End of Part I of Yvain