Chrétien de Troyes

Perceval (Or The Story of the Grail)

Part III

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Lines 2970-3068 The Castle of the Fisher King.

- Lines 3069-3152 The Fisher King gifts the youth a sword.

- Lines 3153-3344 The youth has sight of the Grail

- Lines 3345-3409 The youth leaves with his questions unasked.

- Lines 3410-3519 The maid speaks of the Fisher King and the Grail

- Lines 3520-3639 She questions the youth, whose true name is Perceval

- Lines 3640-3676 The maid speaks of Perceval’s sword.

- Lines 3677-3812 A damsel in distress

- Lines 3813-3899 The Proud Knight of the Wood.

- Lines 3900-3976 The Proud Knight, defeated, is sent to Arthur’s Court

- Lines 3977-4053 The Proud Knight tells his tale at Court

- Lines 4054-4123 King Arthur determines to find the youth.

- Lines 4124-4193 The falcon, the wild goose, and the drops of blood.

- Lines 4194-4247 Sir Sagramore challenges the youth.

- Lines 4248-4345 Kay challenges the youth and his arm is broken.

- Lines 4346-4393 Gawain goes to speak to the youth.

- Lines 4394-4509 Gawain brings Perceval to the King.

- Lines 4510-4578 Perceval makes himself known to all

- Lines 4579-4693 The Ugly Maiden rails at Perceval’s failure.

- Lines 4694-4787 Gawain is challenged by Guinganbresil

Lines 2970-3068 The Castle of the Fisher King

AND on he journeyed all that day;

Yet encountered nothing human,

Neither Christian man nor woman,

Who might point him on his road;

Nor ceased to pray, as on he rode,

To the Glorious King, his Father,

That He’d lead him to his mother.

And he continued, praying still,

Until, descending from a hill,

He saw a river there below;

Swift and deep the current’s flow.

He gazed at it, but saw no ford.

‘Ah! Dear God, Almighty Lord,

Could I but reach the other side,

If she’s alive and well,’ he cried,

‘Then, indeed, I’d find my mother.’

So he rode on, along the river,

Until a cliff he neared apace;

There the water touched its face

Such that he could ne’er pass by.

And then a small boat met his eye,

Floating swiftly down the stream.

And, therein, two men sat, abeam.

While one man steered, by design,

The other fished with rod and line.

He stopped to wait, for he thought

That, as they flew on, they ought

To pass him closely, by and by;

Yet they stopped, as they flew by.

Then he spied the anchor gleam,

And they anchored in mid-stream.

And he who with line and hook,

Was seen to fish, the bait he took,

And then attached a little fellow,

Scarcely larger than a minnow,

To his hook. Not knowing where

To cross, he greeted then the pair,

Called aloud, and asked of them:

‘Can you advise me, gentlemen;

Is there a bridge to the other side?’

And he who fished, he then replied:

‘I’faith, dear brother, there is none,

And then, for twenty miles, not one

Vessel, I do believe, afloat

Larger than is this, our boat,

And this will only carry five.

On horseback none pass alive;

There’s no ferry, bridge or ford.’

‘Tell me then, by God our Lord,

Where I may find a place to stay.’

And he replied: ‘You’ll need, I’d say,

That and more, if I judge aright;

Tis I will lodge you for the night.

Ride up through that gorge ahead,

That cuts through the rock,’ he said,

‘And at the head, there, of the dale,

Below you, you will see a vale;

My house is in the neighbourhood,

Between the water and the wood.’

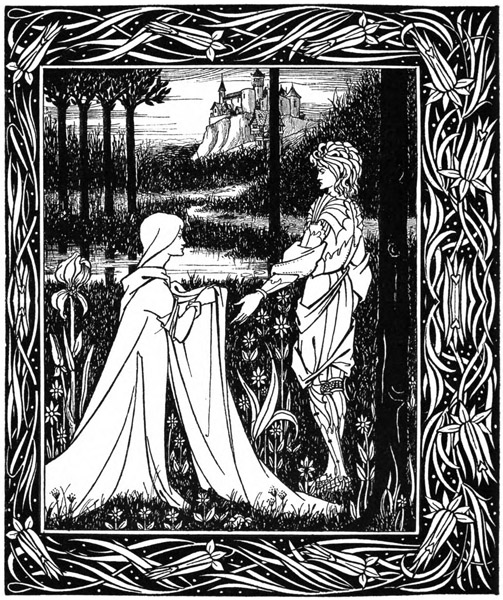

‘My house is in the neighbourhood, Between the water and the wood’

Adapted from Le Morte d'Arthur (1893)

Sir Thomas Malory (15th cent) and Ernest Rhys (1859-1946)

Internet Archive Book Images

So the youth rode, nor did he stop,

Yet when he came to the very top

He could see naught but earth and sky.

‘Did I come here for this, say I?

God bring shame and foul disgrace

On him who sent me to this place!

Tis all a jest, twas all deceit.

I’d find a house there at my feet,

He said, if I but climbed to see;

A fine guide he turned out to be!

Good sir, you who told me this,

You indeed did me ill service,

If you misled me out of spite.’

Then, of a tower he caught sight;

Which in the valley, there, did root;

None finer this side of Beirut,

Nor better sited, would you find.

Square, and of brownstone mined,

Two smaller turrets flanked its sides.

And a hall fronted it, besides,

And lodgings lay before the hall.

The youth rode down towards it all,

Saying now, he’d served him well

Who’d sent him to that hidden dell.

And then towards the gate he wound,

Before the gate, a drawbridge found,

And it was lowered so any might

Ride over it; as did the knight;

And squires now ran to greet him,

Two came and helped disarm him;

A third then led his mount away,

To feed his horse on oats and hay;

A fourth brought him a mantle too,

Of scarlet cloth, all fresh and new;

Then to his lodgings led the knight

Who found his rooms a finer sight

Than any this side of Limoges,

Rooms fine enough to house the Doge.

Lines 3069-3152 The Fisher King gifts the youth a sword

THE youth was in his lodgings till

The lord of the castle spoke his will,

And two squires came then to escort

Him to the hall, and thus the court.

He found the hall was square inside,

For it was long as it was wide.

Amidst the hall, upon a bed,

Sat a lord, grey-haired his head,

And upon that head was set

A fine mulberry-black chaplet,

And the cap was made of sable,

Trimmed with the cloth, of purple,

From which his robe too was made.

Propped on an elbow there he lay;

And before him a fire was alight,

Of dry logs, and it burned bright,

Four pillars there, surrounding it.

And four hundred men could sit

Around that one enormous fire,

Each as warm as he might desire.

Those pillars were good and strong,

Supporting the hood above, of bronze,

The chimney-hood both tall and wide.

When the squires at the youth’s side

Came before their lord, he stirred,

Greeting the young knight with a word:

‘Friend, be you not displeased if I

Cannot stand to greet you, for I

Am unable to do so with ease.’

‘By God, say naught, sire, if you please,

Of that; I mind not,’ said the boy,

‘If God yet grants me health and joy.’

The lord, such was his grievous pain,

Raised himself high on his bed again,

As best he could and: ‘Friend,’ he said,

‘Be not dismayed, draw near the bed.

If you sat beside me, here, I should

View it favourably, an if you would.’

He sat near; then the lord did say:

‘Now, friend, whence come you today?

‘Sire, said the youth, this morn I came

From Beaurepaire; such is its name.’

‘God save me,’ said the nobleman,

Twas a long journey for any man

The journey you have made this day.

You must have started on your way

Ere the watch had called the dawn.’

‘Twas, rather, the first hour of morn,

I do assure you,’ said the lad.

While they this conversation had,

A squire entered through the door;

Slung from his neck, a sword he bore,

From a rich sword-belt it did hang;

He handed it to the nobleman,

Who drew it half-way from its sheath,

So he might see above, beneath,

Where twas made, for there twas writ,

By the maker when he fashioned it,

And that it was of such fine steel

It would not break he did reveal,

Except in one perilous event,

Only known to him who blent

The metals and had forged the sword.

The squire said: ‘The maid, my lord,

Your niece, who is so good and fair,

Sends you this gift, and I declare

You’ll not find one of such strength

For its given breadth and length.

Give the sword to whom you choose,

She’ll be pleased if he shall use

It well, whom you do so reward,

For the one who forged the sword

Made but three, and now he dies;

He can forge no more, but lies

On his deathbed, this is his last.’

At once the lord the weapon passed

To the stranger, on him bestowed

The belt, the sheath, and its load,

For they formed a treasure, all told.

The pommel of the sword was gold,

Arabian or Greek the finish;

The gold-embroidered sheath from Venice.

This gift, and all so richly made,

The lord to the youth displayed,

And said: ‘The sword that you see,

Yours was it destined thus to be,

May it aid you, now and alway;

Take it, and unsheathe it, pray.’

Lines 3153-3344 The youth has sight of the Grail

HE thanked him, girding it on aright

Such that the belt was not too tight,

Then drew forth the naked blade,

And, gazing at it a little, then laid

It back in the scabbard once more.

He gazed at the sword, well he saw

It seemed at his side, as in his fist,

And looked as if it would assist

Him, at need, and most valiantly.

Behind him the squires he did see

Beside the brightly burning fire,

And so he turned towards the squire

Who kept his arms and commanded

He guard the sword, as he demanded.

Then he sat again, beside the lord.

Who him great honour did afford.

And the light there was as bright

As ever did shine the candlelight,

On a guest, in any house whatever.

They spoke of this and that together;

And from a room there came a squire,

And he passed by, between the fire

And bed, where sat the lord and knight,

And bore a lance of purest white

Holding it by the lance’s centre,

And all those there saw him enter,

The white lance, its gleaming wood,

And from the tip the drop of blood

‘The white lance, its gleaming wood, And from the tip the drop of blood’

Adapted from Le Morte d'Arthur (1893)

Sir Thomas Malory (15th cent) and Ernest Rhys (1859-1946)

Internet Archive Book Images

That issued forth, and from its end

Did to the squire’s hand descend;

Drop on drop, of pure vermilion.

The youth, who had but come upon

The place he was that very night,

Refrained from questioning outright

How this wonder had come about,

For he recalled, nor did he doubt,

The ruling Gournemant had taught,

That as a full-fledged knight he ought

To keep from speaking overmuch;

For ready questioning, as such,

Led swiftly in an ill direction.

So the youth asked no question.

Two more squires then appeared,

Candlestick in hand drew near.

Of gold, and inlaid with niello,

Were the candlesticks and, lo,

The squires they were passing fair;

And every candlestick borne there,

Ten lighted candles thus displayed.

And they were followed by a maid,

Fair, neat, and dressed with elegance,

Who bore a grail in her two hands;

‘And they were followed by a maid...Who bore a grail in her two hands’

Le Morte d'Arthur (1893)

Sir Thomas Malory (15th cent) and Ernest Rhys (1859-1946)

Internet Archive Book Images

And as she entered, on their tail,

And bearing in her hands the grail,

So great a brightness shone around,

And cast its light, the watchers found

The candlelight grow dim as, far

Off, dims the brightness of a star,

When the sun rises, or the moon.

After her, there followed soon

A maid who bore a silver plate.

The grail, which went ahead in state,

Was of pure gold, set with gems,

Such precious stones as diadems

Display, the richest to be found,

Beneath the sea, or underground;

Doubtless of much greater worth

Than all the other stones on earth,

The gems that from the grail shone.

From one room to another gone,

In the same manner as the lance,

Before their eyes all did advance.

And the youth, he saw them pass,

But of the grail, dared not, alas,

Ask: whom, with it, one served?

For, in his heart, he now observed

Ever, his wise teacher’s warning.

I fear that woe, to him, twill bring;

For I’ve oft heard it said, that we

At once, may yet too silent be,

As, with this tongue of ours, too free;

If good it bring us, or ill we see,

I ask not, nor did he enquire.

The lord did then command a squire

To see they had napkins and water,

And those his request did further,

Who were accustomed to the task.

They of the lord and youth did ask,

Then in warm water laved their hands,

And next two squires, upon command,

Brought forth a table of ivory,

Which, or so relates the story,

Out of a single piece was made.

Before their lord twas displayed

Then they showed it to the lad;

Then two other squires, who had

Followed them, the trestles brought

Which acquired, when they were wrought,

The property that they would never

Perish, but would last forever.

For they were made of ebony,

Which has the property, you see,

That it will never rot or burn,

But those two things will ever spurn.

The table on that pair they set,

Nor did the tablecloth forget.

Of the cloth what shall I state?

No pope, cardinal, or legate,

Has dined with a whiter one.

The first course was venison,

A whole haunch, peppered, roasted;

And clear wine the table boasted,

In golden cups, a pleasant one.

A squire served the venison,

Carving it on the silver platter,

Into slices, and then the latter

Placing on whole rounds of bread.

Meanwhile the grail, as they fed,

Passed before the youth again,

‘Meanwhile the grail, as they fed, Passed before the youth again’

Le Morte d'Arthur (1893)

Sir Thomas Malory (15th cent) and Ernest Rhys (1859-1946)

Internet Archive Book Images

And, of the grail, he did refrain

From asking: whom, with it, one served?

Thus he the warning still observed,

Which the lord had gently given

Against too much speech, unbidden,

One he remembered, in his heart.

Yet he proved too reticent by far.

At every course that was served

The grail’s passage he observed,

In open view, and yet, reserved,

He knew not whom, with it, one served.

And yet, indeed, he wished to know,

And he would seek the truth, or so

He thought, lest he himself do wrong,

From some squire there, ere long;

Yet till the morning he would wait

When he took leave, at the gate,

Of the lord and all his company;

And set the matter, quietly,

Aside, while they drank and ate.

Well-filled indeed was his plate,

Nor was the wine scarce at table;

Rather all proved delectable.

The dinner was both fair and fine.

Such a meal, such food and wine,

As king, and count, and emperor

Must eat, that night was served before

The lord and the knight, his guest.

Before they went to take their rest,

They sat there, and talked together,

While the squires, after the dinner,

Prepared the beds, served them fruit

And spices, the rarest kinds, to boot;

For pomegranates, figs, and dates,

Cloves, and nutmeg, graced the plates;

Herbs mixed with honey, before bed,

And Alexandrian gingerbread.

And spiced wine they drank; piment,

Without sweet honey or pepper blent;

Clear syrup; and mulberry liqueur.

The youth marvelled, more and more,

At things he knew not, without end;

Until the lord addressed him: ‘Friend,

Tis time to retire now, for the night;

I go, but trouble not, sir knight,

I must lie down in my chamber,

Yet you may, all at your leisure,

Sleep in this room here, outside;

And the being-carried I must abide,

For, over my body, I’ve no power.’

Four servants issued, at that hour,

From a chamber and, as they met,

Each seized hold of the coverlet

By a corner, twas spread alway

Upon the bed where the lord lay;

Thus they bore him to his place.

Other servants, with good grace,

Aided the youth, and they indeed

Did minister to his every need.

They undressed him, when he chose,

Divested him of his shirt and hose,

And in white linen sheets he slept.

And till the morn his bed he kept,

Though the household woke at dawn;

All had risen to greet the morn.

Lines 3345-3409 The youth leaves with his questions unasked

HE looked about him everywhere,

Yet, upon finding no one there,

Was forced to rise from bed alone.

And so, however he might moan,

Seeing he must, he rose from bed,

Having no choice when all was said,

And dressed alone, put on his shoes,

Took his armour, they did choose

To leave by the dais for him to find,

And armed himself again. Yet, mind,

Of what he’d brought he was bereft,

He donned the armour they had left.

When he had adorned his members,

He went out, toward those chambers,

He’d seen all oped the night before,

But closed he found was every door,

And so his wandering was in vain.

He shouted then he called again;

None opened there, or spoke a word.

When he’d ceased to call, unheard,

He went to the doorway of the hall,

Found it open, so, armour and all,

He thus descended the castle stair,

And found his horse, saddled, there,

And saw his shield, and his lance

Against the wall, and did advance,

And, mounting, looked on every side,

But not a soul did there abide,

Ne’er a single squire did he see.

He approached the gate, silently,

And there he found the drawbridge down,

Which the good people of the town

Had left thus lowered, I suppose,

So that, at any time he chose,

He could leave without delay.

He thought all the squires away

In the forest, all gone that day

By the bridge, to check their nets.

He cared not to wait, and yet,

Said to himself that he must go

To ask them if they might know

Of the lance that thus did bleed,

If they could tell of it, indeed,

And, of the grail, where it was borne.

So he rode on to greet the morn;

Yet before the bridge he’d cleared

His horses’ front hooves appeared

To rise, and rise, till in the air

His horse leapt, and leapt full fair,

And had the horse not leapt so well

Both had fallen, yet neither fell,

Neither the steed nor he who rode.

And he looked back along the road,

Wondering how this was, amazed

To see the drawbridge had been raised,

And called aloud, yet none replied:

‘You who raised the bridge’ he cried

‘Come you now, and speak with me!

Where are you that no eye can see?

Show yourself, grant me a view,

For there’s a thing I’d ask of you

The answer to it I would know.’

But all his words were wasted so,

For none there replied, nor would.

Lines 3410-3519 The maid speaks of the Fisher King and the Grail

SO he rode on towards the wood,

And entered on a path, and found

Horses’ hooves had marked the ground,

Where riders had passed that way.

‘This path,’ he said ‘they took this day,

Those squires whom I came to find.’

So through the woods he did wind,

While the hoof-prints he could see,

Till a maid, beneath a fine oak-tree,

He chanced upon, and she did moan,

And weep and wail there, and groan,

Like to some poor wretch in sorrow:

‘Alas,’ cried she, ‘ill was the morrow,

And ill was that day when I was born,

That destined me to a life forlorn!

Nothing worse could come to me!

Would to God my love, that I see,

And hold here in my arms, dead,

He’d preserved from death instead.

His death makes me to weep and pine.

Would that he lived, and death was mine!

Why take his soul, yet mine remains?

What is life worth, with all its pains,

When all that I loved here lies dead?

Without him I care naught, instead,

For this my life, or this my body.

Death, now snatch my soul from me,

To be a handmaid that would fain

Accompany his, if he so deign.’

Tears from her eyes she expelled,

For a knight whose corpse she held,

Whose head had been severed clean.

The youth, her sorrow having seen,

Halted not till he was before her,

Then he stopped and saluted her,

And she him with her head bowed;

Yet did not cease to weep aloud.

And the youth said: ‘Who did harm

To the knight who lies in your arms,

Demoiselle? Sire, twas a knight,’

Said the maid, ‘on this very morn.

Yet I marvel; you might rise at dawn,

God save me and my witness be

To this wonder that here I see,

And thirty-five leagues straight

Ride the way you came of late,

Before you ere might come upon

Lodgings, honest, clean, that one

Might find good; and yet your steed

Has gleaming flanks, as if indeed,

He’d been groomed at some inn,

And fed on oats and hay within,

Washed and brushed, for his coat

Could not be glossier, his throat,

His neck, nor he look better fed.

And you too, risen from some bed,

Or so it seems to me, fair knight,

Where you found rest and ease last night.’

‘I’faith, fair lady, and to my mind,

The best I might I there did find,

And if I show it tis only right.

If any were to shout outright

Now, from here, where we are,

They’d hear it there, tis not far,

There, where I did pass the night.

You cannot truly have had sight

Of all this land, nor traversed all.

I had lodgings, I thus recall,

That are the finest I have known.’

‘Ah, fair sire, then do you own

That you did find such fine lodging,

At the castle of the Fisher King?’

‘Maid, by the Saviour, I know not

If he’s king, fisherman, or what,

But he’s most wise and courteous.

I can but say, last eve it was

Two men I saw, and in one boat,

Which gently down the stream did float.

One man chose the course it took,

The other fished, with line and hook,

He spoke of his house, where I might

Find lodgings, as I did, last night.’

And the maiden said: ‘Fair sire,

He is a king, for I am no liar,

But in a battle he was maimed,

Wounded sorely, and so lamed

That naught is to be done at all.

The wound that did him befall?

A javelin pierced both his thighs,

And the pain doth him chastise,

Such that he cannot mount a horse,

Yet when he would have recourse

To sport or pleasure, in a boat

He is placed, and then, afloat,

Fish to his hook he doth bring;

Thus he’s called the Fisher King,

And that pleasure is his delight;

For there is naught else, sir knight,

That he may suffer or endure.

He cannot hunt now as before,

But huntsmen, wild-fowlers too,

Falconers, archers, not a few,

He has, to scour his realm for game.

So he is pleased, though he is lame,

To remain there in his retreat.

For in all the world, there’s no seat

So benefits him, and nowhere

Suits him as well, so tis there

Was built his house fit for a king.’

Lines 3520-3639 She questions the youth, whose true name is Perceval

‘I’FAITH, there’s truth in everything,’

Replied the youth, ‘that you do say.

I saw such wonders, yesterday;

As I stood at a distance there,

When to his hall I did repair,

He told me I should draw near,

And sit by him and, lest it appear

Twas from pride he failed to rise

And greet me, I should realise

He could not do so, and, at that,

Seeing he lacked the power, I sat.’

‘Surely, he did you great honour,

To seat you there in that manner!

And when you were seated there,

Say if you saw, and were aware

Of the lance, from which blood drains,

Though it has neither flesh nor veins?’

‘Did I see? Yes, i’faith, did I.’

‘And then, fair sire, did you ask why

It bled.’ ‘No, I asked naught at all.’

‘God save me then, whate’er befall,

You worked ill, that you did so fail.

Now tell me, did you see the grail?

‘Now tell me, did you see the grail?’

Le Morte d'Arthur (1893)

Sir Thomas Malory (15th cent) and Ernest Rhys (1859-1946)

Internet Archive Book Images

‘Yes, indeed.’ ‘And who held it near?’

‘A maid.’ ‘From whence did she appear?’

‘From a room she came; she did go

Into another, and passed me so.’

‘And the grail, did any go before?

‘Yes.’ ‘And who?’ ‘Two squires, no more.’

‘In their hands, what were they holding?’

Candlesticks, full of candles glowing.’

‘And behind the grail, what came after?

‘A maid.’ ‘And what held she before her?’

‘She held a little silver plate.’

‘And did you not ask, or soon or late,

Where it was they were going to?’

‘Naught from my lips did so issue.’

‘So much the worse; and God defend

Me, and have you a name, my friend?’

And he, who knew not his true name,

Divined it, saying from Wales he came,

And Perceval the Welshman was he,

Not knowing if he spoke truthfully;

Yet spoke true, though he knew it not.

And the maiden then, on hearing what

He’d said, rose up, from him who’d died,

And, as if in anger, she replied:

‘Your name is changed.’ ‘How?’ said he.

‘Now Perceval the Wretched be!

Ah, Perceval, the unfortunate,

What grave mischance has marred your fate;

That all you saw you failed to question!

For if you had but sought direction,

You’d have healed the crippled king,

Renewed the use of both his limbs,

And he’d have trod his realm again.

And great good would we have gained!

But now, you must know, ill will fall

On you, and on others cast its pall.

For your sin against your mother,

It ensues, and against no other,

For through you she died of grief.

I know you better, tis my belief,

Than you do me, for you know not

That I too am of your line begot;

For your mother’s house, that same,

Raised both; I, your cousin germain.

I grieve no less that you did fail

To seek to learn about the grail,

What is done with it, where tis borne,

Than for your mother I do mourn,

Nor, indeed, for this knight here

Whom I loved and held most dear,

And most for this, that he called me

His own dear friend, and guided me

As should a frank and loyal knight.’

‘Ah, cousin, if you speak aright,’

Said Perceval, ‘and all this is so,

Then tell me how it is you know.’

‘I know she’s dead,’ the maid replied,

‘As truly as those men who sighed

And placed her body in the ground.’

‘May God, for his goodness renowned,

Have mercy on her soul,’ said he.

‘An ill tale have you told to me.

And since she is beneath the earth,

What then is further effort worth?

For I was journeying for naught

Except to see her whom I sought.

Now I must choose another road.

But if with me you now would go

I am most willing; he, who here

Lies dead, can aid you not, I fear;

The living to the living,’ he said,

‘And likewise, the dead to the dead!

Let us go, you and I, together.

For tis folly and no other,

It seems to me, that you, alone,

Should guard the dead, and make moan.

Let us go seek him who did slay

Your love and if, upon the way,

I meet with him, I pledge,’ said he,

‘I’ll conquer him, or he’ll slay me.’

And she who could not supress

Her grief and her heart’s distress,

Replied: ‘Sire, there is no way

That I can go with you this day,

Nor leave him ere he is interred.

If you trust in me then, in a word,

Go you that way, the paved road,

For that way too the fell knight rode,

That proud knight who, so cruelly,

Has taken my sweet love from me.

And yet I don’t say that because

I’d have yourself take that course

God help me, and pursue him still;

Though I do wish him every ill,

As if twere my own self he’d slain.

Lines 3640-3676 The maid speaks of Perceval’s sword

BUT the sword, how did you gain

That weapon, hung at your left side,

That ne’er drew blood, nor man defied,

Nor e’er was drawn in time of need?

I know where it was forged, indeed

I know the hand that forged it too.

Take care, and trust it not, for you

That blade will utterly betray;

Amidst the battle, on that day,

Suddenly, twill break to pieces.’

‘My cousin, one of the fair nieces

Of my kind host, sent it last eve

To him, and he gave it to me.

I thought it a fine gift, but nay,

Now it fills me with dismay

If all that you have said is true.

Tell me if you know, say you,

If this blade should ever break,

Could any smith the sword remake?’

‘Yes, but great pains must he take.

Who knows the road to the lake

That lies beyond Cotouatre,

He might have the blade, thereafter,

Re-forged, and tempered, and made so.

If you should venture thus to go,

Then seek for none but Trebuchet,

The smith who forged it, on a day;

He made, and could remake it true,

As never another smith could do,

That you might meet with anywhere.

That no other so attempt, have care;

They’ll not succeed, tis my belief.’

‘Indeed, it would bring me grief,’

Said Perceval, ‘were it to break.’

She watched, as he his way did take,

Not wishing from the dead to part,

For whom she grieved in her heart.

Lines 3677-3812 A damsel in distress

PERCEVAL sped on, like a hound

Hot on the trail, until he found

A palfrey, so bone-tired and thin,

Treading the path in front of him,

So thin and wretched a creature,

It seemed in the course of nature

To have fallen into evil hands,

Subject to one and all’s demands,

Ill-cared for, as if it had, indeed,

Been nothing but a hired steed,

Labouring in the hours of light,

And much neglected overnight.

Such it was the palfrey seemed.

It shivered so you might have deemed

Half-frozen twas, the trembling horse,

Or feverish, and the mane, perforce,

Long vanished, ears drooping low;

Fit but to feed the dogs, although

The hounds and the mongrels would

Find only skin and bones, not blood,

Since only skin the bones did hide.

On its back, a saddle did reside,

On its head, a bridle did sag,

Such as were suited to the nag;

A maiden rode it, and made moan,

None more wretched ever known,

Yet she would have passed for fair

If she’d known better fortune there.

But she was then in such distress,

That not a palm’s breadth of her dress

Was whole, and then through the rips

Her breasts both displayed their tips.

With clumsy stitches here and there

The garment was sewn and patched;

Her skin too had been badly scratched,

By hail, and scorched by snow and frost.

Her hair hung loose, her veil was lost,

Thus, all exposed, appeared her face,

And it was marked by many a trace

Of tears that each had left its stain

As they fell, ceaselessly, like rain,

And trickled down to wet her breast

The garment in which she was dressed,

And all its cloth, down to her knees.

But sadder still than were all these

Was her heart, its weight of care.

As soon as Perceval saw all there,

He rode at full speed towards her,

While she sought to draw together

Her torn dress, to hide her better;

Though the holes seemed rather

Bent on growing, and moreover

As she sought each hole to cover,

Another hundred opened wide.

Pale and wretched thus, she sighed

And moaned, as Perceval drew near,

Bewailing, he could not but hear,

Her suffering, her loss of ease:

‘Lord,’ said she, ‘if it but please,

Let me not live in long duress!

Long I’ve endured wretchedness,

Yet these, my ills, are undeserved!

Too ill a fate’s for me reserved!

Lord, you know that I have not

Merited all that seems my lot,

So, God, send me, if you know,

Someone who might ease my woe,

Or deliver me from him I blame,

Who makes me to live in shame.

He shows such small mercy to me,

That I shall not, alive, go free;

And yet he wills not I should die,

And I know not the reason why

He seeks my company this way,

Unless some pleasure now it may

Grant him, my shame and misery.

Yet if he knew, and knew truly,

That I’d, indeed, deserved it all,

Then his mercy on me should fall,

Now that I have paid so dearly,

If I had pleased him, yet clearly

He loves me not at all, when he

Forces me to live so harshly,

Following him, and he cares not.’

‘God save you, lady, from your lot!’

Cried Perceval, now at her side,

And hearing him, she thus replied,

Hiding herself, voice soft and low:

‘Fair sire, who doth greet me so,

May your heart’s desire be granted,

Though your greeting is unwanted.’

Perceval, who blushed with shame,

Responded to her words of blame:

‘Halt then, my lady, tell me why?

For, at no time, I think, have I

Seen you before, nor in any way

Done wrong to you ere this day.’

‘Yes, you have,’ she said, ‘for I

Am so wretched, so gone awry,

That none should give me greeting.

I sweat with anguish on meeting

All who detain, or gaze at, me.’

‘I was not yet aware, most truly,’

Said Perceval, ‘of that mischance.

For I’d no intent, at this instance,

To cause you shame, nor this day

Came so to do; I chanced this way.

Yet since I see you weeping there

In such wretchedness, poor and bare,

No joy will I have, in my heart

If you do not now, for your part,

Say what has caused you such pain

And sorrow, as you now sustain.’

‘Ah, fair sire, have mercy on me!

Be silent now, for you must flee

And leave me here alone, in peace.

You do wrong, for you must cease

To linger; flee, if you’d be wise.’

‘If so,’ said he, ‘I’d be apprised

Of what threat, or from what abuse,

I should flee, where none pursues?’

‘From the Proud Knight of the Wood,

Who asks naught, tis understood,

Except the melee and the fight,

Or encountering some knight,

And who if he finds you here

Must surely slay you, I fear.

He hates it if I rest at all,

And none departs intact withal,

Who lingers thus to talk with me,

Should he arrive in time; you see,

He takes from every man his head,

And he, before he strikes them dead,

Tells each man why, with cruelty,

He worries and chastises me.’

Lines 3813-3899 The Proud Knight of the Wood

WHILE they talked, as any would,

The Proud Knight issued from the wood,

And came much like a lightning thrust

From thence, in clouds of sand and dust.

Crying: ‘You there, beside the maid,

Twas ill in truth when you waylaid

Her; know you that your end is come,

In that you made her halt, for some

Few steps, perchance, or only one.

Yet I’ll not slay you, ere I’m done

Telling you the reason why

For what crime, what misdeed I

Make the maid endure such shame.

Listen, and you’ll hear the same.

One day to the wood I was gone,

And behind, in my pavilion,

I’d left this maiden, whom I loved

More than all the stars above;

When, riding through the wood, there came

A Welshman; I know not his name,

Nor where he went to, after this,

But ere he went he stole a kiss

From her, by force, or so she said;

And if she lied, what then, instead?

Once he’d kissed her; despite his will

Would he not, then, have had her still?

Yes, indeed, none would believe

That he could simply kiss and leave,

Since one thing leads to another.

He who kisses and does no other,

When they are one on one, alone,

The choice is his, if all be known.

A woman who doth not protest

At the kiss, soon grants the rest,

Tis what she doth herself intend,

And though herself she doth defend

Tis known to all, without a doubt,

A woman would win every bout

Except that one melee of note

Where she grabs him by the throat,

Scratches, bites, and seeks to kill,

For she would be vanquished still,

Though she defends and doth delay.

Too cowardly to yield the day,

She wishes force to take its place,

Though he ingratitude will face.

And so I think he lay with her.

And took my ring, as I discover,

Which she wore upon her finger.

His taking it has fuelled my anger.

But ere he did he drank my wine,

And ate of three good pasties, mine;

The three were being kept for me.

So now a fine reward has she,

This lass of mine, as all can see.

Let them pay who yield to folly,

So they’ll not care to sin again.

I was full mad with anger then,

When of the truth I had sight.

Furious, what I did was right:

Her palfrey would not be fed

On oats, nor groomed, I said,

Nor be re-shod; and what she wore,

The cloak and tunic from before,

She should wear, until that hour

When I’d have him in my power

Who’d forced her, until he’d bled

In battle, and I’d won his head.’

When Perceval had heard him out

He replied, turn and turn about:

‘Friend, know this truth, for one,

She has more than penance done,

For I am the man who kissed her,

By force, and so much grieved her,

And from her finger took the ring

But did, and had, no other thing;

Though I did eat, I must confess,

One pasty and a half, no less,

And drank as much wine as I would,

Yet wisely, not all that I could.’

‘Upon my life, the knight replied,

‘The whole thing has me stupefied,

Tis a fine meal now that you serve!

Death you, assuredly, deserve,

If your confession is but true.’

‘My death is not so near; be you’

Said Perceval, ‘assured of that!’

Lines 3900-3976 The Proud Knight, defeated, is sent to Arthur’s Court

AND having dealt, thus, tit for tat,

Without more words, each spurred his steed

At the foe, so furiously indeed

They made splinters of their lances,

To the earth made their advances,

As from their saddles they were thrown.

But both leapt to their feet, I own,

And trusted to the naked blade,

And mighty blows each other paid.

The battle was both long and hard.

Of that no more, so says the bard,

To yield it time were time wasted,

Except to say that both men tasted

Enough of it, for the Proud Knight

To cry mercy, and, as was right,

Perceval, who had ne’er forgot

The lord who’d advised him not

To slay any knight who’d lost

And mercy sought, at any cost,

Declared: ‘No mercy yet is due

To you sir knight, I’faith, till you

Show some mercy to your friend,

For she has not, you may depend

Upon it, deserved the sorry ill,

That you make her suffer still.’

As she was the apple of his eye,

‘Fair sire, I will,’ was his reply,

‘I’ll make amends as you advise.

There is no task you can devise

That I’m unwilling to perform;

My heart is sad at all the storm

Of grief and woe I’ve made her bear.’

‘Go to your nearest dwelling, where

The maid can bathe herself and rest,

And be your manners of the best,

Till she is fully healed, and well;

Then, dressed in her best apparel,

Let her be led to Arthur’s court,

Greet the king for me; and sport

The same armour you now wear,

And go seek out his mercy there.

If he demands whence you come,

Say tis from the same lad whom

He made a knight, armed in red,

Thanks to the wise and prudent head

Of my Lord Kay the Seneschal.

And there repeat to one and all,

The penance that your maid did bear;

Go tell the king, the courtiers there,

Your tale, the queen, and every maid

Of whom she leads a fine brigade.

And I prize one, fair and lovely,

Who was, because she smiled at me,

Dealt by Sir Kay a vicious blow

That nigh on stunned the maiden so.

Seek her out, such is my command,

And tell her, she will understand,

That I’ll not enter, not for aught,

The hallows of King Arthur’s court,

Until I have avenged that blow;

Which she’ll be overjoyed to know.’

And he declared that he would go,

Most willingly, and tell her so.

His words he’d faithfully convey,

And do so without more delay

Than was needed for them to rest,

His maid be well, and be dressed,

And they equipped with all required;

And, he declared, he much desired

That Perceval lodge there, and rest,

To treat his wounds, twould be best,

Until his cuts and bruises healed.

‘Go, may fate good fortune yield,’

Said Perceval, ‘keep her in mind;

For other lodgings I shall find.’

Lines 3977-4053 The Proud Knight tells his tale at Court

THEIR talk thus ended for the day,

Both the knights brooked no delay,

And left, as swiftly as they might.

The one who’d lost, that very night,

Had his lover bathed, and dressed

And with such care was she blessed

To her full beauty she returned.

Then to the journey there they turned,

And to Carlion took their road,

Where King Arthur had his abode,

And he held a feast now, privily,

For he’d gathered there but three

Thousand worthy knights of note,

To them his presence did devote.

The knight entered Arthur’s court,

With his lover whom he’d brought,

And rendered himself his prisoner,

Before him did this speech deliver:

‘I’m here as your prisoner, sire,

To be dealt with as you desire,

Which is reasonable and right,

So commanded by that knight

Who crimson armour asked of you,

And then fought, and won it too.’

On hearing this, King Arthur knew

The matter he alluded to:

‘Remove your armour now, fair sire,

May he who sends you thus to me

Find fortune, and right joyous be.

Be welcome, for we hold you dear,

And you shall be most honoured here.’

‘Sire, one thing more he asked of me,

And this much I would ask of thee,

Ere I disarm, that the queen be here,

And her ladies, that they might hear

The substance of this further thing

This message I was asked to bring,

Which requires the presence though,

Of the maid who was dealt a blow

For a smile she gave, on a time,

And twas, that smile, her only crime.’

Here the Proud Knight’s speech ended.

The king hearing the thing depended

On the queen’s presence, sent for her;

She came and all her maids, together,

They hand in hand, and two by two,

So they might hear the message too.

When the queen was seated beside

Her lord, King Arthur, the knight cried:

‘Lady, his greetings one doth send,

One upon whom you may depend,

Who is a knight I prize, for he

By force of arms defeated me.

Of him I know no more to tell

But that he sends this maid as well,

To you, this friend I have beside me.’

‘I thank him then, my friend’ said she.

And then the knight retold that same

Tale of cruelty and shame,

You have heard, how for so long

She’d felt the weight of his wrong.

And hiding naught, but with a sigh,

He yielded all, and the reason why.

After his speech, they pointed out

The maid whom Kay had dealt a clout,

And the knight said: ‘He who sent

Me here, lass, said that his intent

Was that I greet you now from him,

Nor loose the boots from my limbs,

Until I’ve said that not for aught

Will he enter King Arthur’s court,

So help him God, till he’s repaid

The blow, the shame upon you laid,

That you, for him, were forced to bear.’

Lines 4054-4123 King Arthur determines to find the youth

AND then the fool leapt in the air,

At all he’d heard, and he did cry:

‘God bless me, Lord Kay, say I,

An you will pay the price, truly,

And it will be soon, most surely.’

After the fool, then spoke the king:

‘Ah, Kay, twas a discourteous thing

You did when you mocked the youth!

It was your mockery, in truth,

That drove him from me, forever.’

And then the knight, his prisoner,

The king made to sit before him,

And, freeing the knight, had him

Stripped of armour, at his command.

And he who sat at his right hand,

My Lord Gawain, did now enquire:

‘In God’s name, then who is he, sire,

Who has conquered, by arms alone,

As good a knight as e’er was known?

Through all the Isles in the sea,

I’ve never yet had named to me

Nor e’er seen a knight or known,

A peer to this knight here, I own,

In feats of arms or chivalry.’

‘His name it is unknown to me,

Dear nephew, replied the king.’

‘I saw him, yet asked not a thing

Of him, nor his name, I confess,

For he of me did make request

To dub him, on the spot, a knight,

I thought him noble, at first sight,

And said, thus: “Brother, willingly;

Do you dismount, and instantly,

Until here we may have brought

Gilded arms such as you sought.”

And he replied that he would not

Tread the ground, until he’d got

The crimson arms he coveted.

He’d have no other arms, he said,

His words stunning us outright,

But those sported by that knight

Who stole the golden cup from us.

Then Kay, who was discourteous,

And is, and will be so alway,

Who never good doth seek or say,

Cried: ‘Brother the king grants you

That armour, you may take it too!’

The lad who thought he meant it

Chased the knight and, in a minute,

Killed him with a javelin throw.

Though if you ask I do not know

How the combat thus began,

But the Knight in Vermilion

From the wood of Quinqueroi,

I know not why, struck the boy,

With his lance, all in his pride.

And thus, all proudly, he died,

Struck by the javelin, in the eye,

And, to the lad, arms did supply.

He’s served me so well, since then,

By Saint David, to whom the men

And the women of Wales do pray,

I’ll not abide more than a day

Or sleep two nights together

In the selfsame hall or chamber,

Till I know he lives; on land or sea,

Rather, I’ll seek him endlessly.’

And when they heard the king so swear

They knew, all those who were there,

That, he would truly seek him so.

Lines 4124-4193 The falcon, the wild goose, and the drops of blood

THEN you’d have seen them go

Fill the chests, and naught forget,

Not one sheet, pillow, or coverlet,

And burden the pack horses too,

And load the wagons, not a few;

So many the tents and canopies,

A well-lettered clerk might seize

His pen, and write all day, and yet

Not tally all, nor the sum be met

Of all they’d packed so rapidly.

Then the king departed swiftly,

From Carlion, and there behind

Rode all his barons, nor, you’d find

Did one handmaiden still remain;

All followed in the queen’s train,

To show her power and majesty.

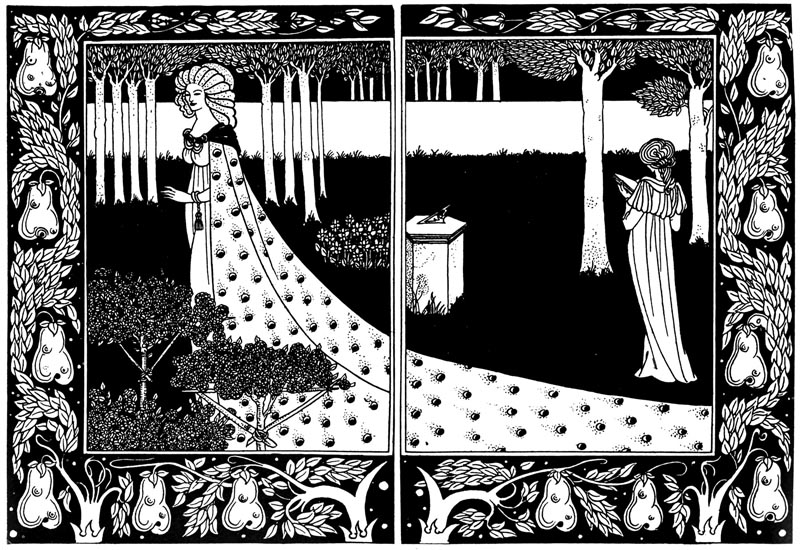

‘All followed in the queen’s train,To show her power and majesty’

Le Morte d'Arthur (1893)

Sir Thomas Malory (15th cent) and Ernest Rhys (1859-1946)

Internet Archive Book Images

That night in the fields did he

Set up his camp, beside a wood.

And that night snow fell, to hood

The land with its chill canopy.

Perceval, that morn, rose early

As he was wont to do, a knight

Who always wished to alight

Upon chivalry and adventure;

And he chanced, at a venture,

On that field where the king’s tent

Was with snow and frost all blent.

But ere he came that tent before

A flock of wild geese he saw

That had been dazzled by the snow.

He saw them and heard them, low

Above the ground, all flying

From a falcon that came crying

After them, at breakneck speed,

Till it spied one bird, indeed,

Separate from all the others,

Struck hard at the tail feathers,

Knocking the bird to the ground;

But proved too tardy, as it found,

Flew off, and failed to seize its prey.

Perceval swiftly made his way

To the place where he saw it fall.

The goose, wounded scarce at all,

Let fall, there, three drops of blood,

That dyed the snow, as if it could

Have been so tinted by nature.

So unharmed was the creature

That, when awhile it had lain

Where it was downed, it once again

Took to the air and flew away.

But Perceval say the disarray

Of the snow, where it had been,

And the blood still to be seen,

Where he leant upon his lance.

He well-nigh fell into a trance,

As it revealed the fresh colour

That graced the face of his lover,

For there he felt, in plain sight,

The crimson offset the white,

As these drops of blood had so

Dyed the whiteness of the snow;

And his mind as thus he gazed

Was with delight so fair amazed,

Dreaming twas the colour there

Of the face of his love so fair.

Perceval mused, and thus did eye

The blood all morn, till, by and by,

The king’s squires issued from the tent

And seeing him there, all intent

On his vision, thought him sleeping.

Lines 4194-4247 Sir Sagramore challenges the youth

THOUGH the king was still slumbering,

Where he lay, quietly, in his bed,

The squires encountered, instead

Before the king’s grand pavilion,

Where there was scarcely anyone,

Sir Sagramore, the Impetuous,

Or called such by the cautious.

‘Whence is it, you squires scurry?

Now, hide naught, why the hurry?’

‘Sire, over there we saw a knight

Sleeping on his horse, upright.’

‘And is he armed?’ ‘He is i’faith.’

‘Then I’ll go speak to him, i’faith,

And I shall bring him to the court.’

Sagramore then went and sought

The king’s bed, and woke the king.

‘Sire, there’s a knight slumbering

Outside,’ said he, ‘in the open field.’

The king his command did yield,

That Sagramore should swiftly go

Speak to the knight, plead, and so

Bring him to them, in due course.

So Sagramore called for his horse,

And said to bring his armour on,

And what he asked, that was done;

Thus he was soon armed indeed,

And, fully armed, spurred his steed,

And rode out, towards the knight:

‘Sire, now you must come, of right,

To the court.’ He spoke not a word,

The knight, as if he had not heard;

So Sagramore, he spoke again;

Silent the knight did still remain.

‘By Saint Peter,’ Sagramore cried,

‘You shall come, I’ll not be denied!

To sit here, and to plead with you,

That angers me; my words to you

Have proven thus but ill-employed!’

Then lance and pennant he deployed,

And on the field he took his stance,

And warned the knight he would advance

And strike him should he not beware.

Perceval looked towards him there,

And saw a fight was what he sought,

And so, emerging from his thought,

The knights met violently together.

As they encountered one another,

Sagramore’s lance broke in two,

But Perceval’s followed through,

And struck the knight with such force

It sent him tumbling from his horse,

While the steed, its head held high,

Sped on, and from the field did fly,

At full gallop, towards the tents.

Lines 4248-4345 Kay challenges the youth and his arm is broken

THE barons, knowing what it meant

To see the empty saddle, muttered.

But Kay who scarcely ever uttered

A kind word, cried out, jeeringly,

To the king: ‘Fair Sire, now see,

How Sagramore returns to you;

The knight held by the bridle too,

He leads him here against his will!’

‘Kay,’ said the king, ‘you do ill

In sneering at true gentlemen.

Go you there, and do better then

Than Sir Sagramore, if you can.’

‘Sire,’ said Kay, ‘tis pleased I am

That you, sire, would have me go.

By force, whether he will or no,

I’ll bring him here, the very same,

And I shall make him tell his name.’

Then he armed himself, carefully,

And armed, and mounted, thus did he

Go towards the knight who gazed

On three drops of blood, so mazed,

He gave no thought to other things.

He heard not Kay’s loud bellowing

From afar: ‘Fellow, attend the king!

You will go there, or I shall bring

You, and you shall pay most dearly.’

Perceval, now he heard more clearly

Kay’s menaces, wheeled his mount,

And with steel spurs gave account

Of his intent; and the horse sped on,

So that the two knights met head on,

Each longing to display his skill;

Each rode, as if he aimed to kill.

Kay struck as hard as he could,

But his lance broke like rotten wood,

While Perceval, gathering no moss,

Struck Kay above his shield boss,

Hurling him against a boulder,

So as to dislocate his shoulder,

And twixt it and the elbow there

Break the bone, and him impair,

Indeed it snapped like a dry stick;

Just as the Fool divined, full quick

What the Fool divined was done;

Proven true was his divination.

Kay fainted away in sore distress,

While his horse did flight address,

Galloping away towards his tent.

The Britons knew what it meant:

The horse, but not the Seneschal.

Squires ran, on the reins to haul,

And the knights and ladies stirred.

When of his fainting they all heard

They feared lest he might be dead.

The king was most discomforted,

And they were grieved one and all.

But on the three drops that did fall,

Perceval, propped upon his lance,

Returned to gaze, as if in trance,

The Seneschal was only wounded;

Now the king was greatly angered,

But the lords said: be not dismayed,

For Kay would heal, with the aid

Of a doctor who knew how to set

The collarbone in place, and let

The broken arm repair correctly.

And the king who cared dearly

For Kay, and loved him, at heart,

Sent a doctor, skilled in his art,

And three maidens, trained by him,

Who reset the collarbone for him,

And so strapped the broken arm

The bone would knit, without harm.

They carried Kay to the king’s tent,

And comforted him, on solace bent,

And said no sorrow should he feel,

For he’d be well, and swiftly heal.

My Lord Gawain said to the king:

‘Sire, it is but a sorry thing,

God save me, as you well know,

For you yourself have told us so,

Always, and have judged aright,

For others to disturb a knight

As these two have, when deep in thought

Upon any matter; and for naught.

Whether they’ve done wrong or not,

I cannot say, but grief’s their lot,

And great mishap, most certainly.

The knight mayhap, it seems to me,

Was thinking on some loss of his,

Or his lover whom he doth miss,

He was so troubled, ill at ease.

But I will go and, if it please,

View the knight’s countenance

And if I find, when I advance,

That his thoughts now are bright,

I will then request the knight

Comes and attends upon you here.’

Lines 4346-4393 Gawain goes to speak to the youth

AT this, Kay angered did appear

And said: ‘Ah, my Lord Gawain

No doubt by his hand you’ll be fain

To take him, though ill he vows!

You’ll do well, if he so allows,

And thereby concedes the fight.

So you’ve taken many a knight.

When the man was good and tired,

And a swift abatement he desired,

Then of the king you asked leave

His prompt surrender to receive!

Gawain, rain curses on my head,

If you’re any man’s fool, instead

We should take lessons from you!

You know the art of speaking too,

In words both pleasant and polite.

Would you e’er say, to a knight,

Things haughty, irritating, vile?

Those we know we would revile

Who’d think it, or e’er thought so!

In a silken gown you could go

To conduct this whole affair,

And never be obliged to bear

A sword now, or break a lance.

You only need seize your chance,

Get your tongue round a word or two,

Such as: “Fair sire, God save you,

And keep you alive and healthy,”

He’ll do your bidding instantly.

There is naught for you to learn,

Compliments are yours to turn,

You’ll stroke him as one strokes a cat,

And all will say: ‘In dire combat

My Lord Gawain fought manfully!’

‘Ah, Sir Kay, more courteously

You might speak to me,’ he said.

‘Will you vent your spleen on my head,

Treat me to your maliciousness?

Fair sweet friend, I will address

This matter, i’faith, and yet own

To no dislocated collarbone,

Or broken arm, as some today,

For, indeed, I like not such pay.’

‘Nephew, go now,’ said the king,

‘You’ve said many a courteous thing;

If you can do so, bring the knight

But go you armed, as if to fight,

For defenceless you shall not go.’

Lines 4394-4509 Gawain brings Perceval to the King

GAWAIN was armed, and swiftly so,

Whom, for his every virtue, they

Praised and prized, and straight away

Mounted a strong and willing steed,

And rode to the knight, at full speed,

Who leaning there, upon his lance,

Proved neither weary in his stance

Nor of his thoughts, where every one

Pleased him still, although the sun

Had melted two of the blood stains

That blent with the snow their remains,

And now the third was vanishing,

So that though absorbed in musing

He was not quite so entranced.

And my Lord Gawain advanced

Towards him at an ambling pace,

Nor threat nor anger in his face,

And said: ‘Sire, I’d have hailed you

Had I known your heart as I do

My own, and yet this I may say

I come to meet you here today

As a messenger of the king,

And, from him, a request I bring

That you will go and speak with him.’

‘Two have already come from him,

Said Perceval, ‘who thus disturbed

My pleasure, and would have curbed

My freedom, by leading me away;

For I was deep in thought, I say,

Thought that offered me delight,

And those two, who wished to blight

My liberty, sought not my good.

Three crimson drops of fresh blood

Lay there before me on the snow;

And twas illumined by their glow,

And, gazing there, it seemed to me

That in those colours I did see

The fresh hues of my lady’s face,

And would rest ever in that place.’

‘Indeed, sire’ said my Lord Gawain,

‘Such thoughts as these, I would maintain

Are far from base, but rare and sweet;

Brutes and fools those who compete

To draw your heart from such musing.

Yet I long to know this simple thing:

What you might wish, that being so;

For I would willingly have you go

See the king, should it not grieve you.’

‘First, tell me, sire, or e’er we do,

And tell me true,’ said Perceval

If Kay be there, the Seneschal?’

‘Yes, he is there, indeed tis true,

For he but now fought with you,

And that fight it did him harm,

For it has broken his right arm,

And put awry his collarbone.’

‘Then the maid’s avenged, I own,’

Cried Perceval, ‘whom Kay struck.’

These words of his, so uttered, took

Gawain aback; amazed, he cried:

‘God save me, for the king doth ride

In search of you, tis why he came.

Sire, may I ask of you your name?’

‘Perceval am I; and you are, sire?’

‘Know then that I, tis your desire,

Was given, when baptised, the name

Of Gawain.’ ‘Gawain?’ ‘Yes, the same.’

Perceval joyed at what he heard,

And said: ‘Fair sire, many a word

Of you I’ve heard in many a place,

And I would have we two embrace

In friendship, such I’d ask of you,

If you but chose to seek it too.’

‘Indeed,’ replied my Lord Gawain,

‘An twould please me no less to gain

Such friendship than twould you, withal;

More, I believe.’ ‘Then,’ Perceval

Cried: ‘I’faith, I will go with you,

Willingly, tis right and proper too;

And greater esteem doth me attend

That I may call myself your friend.’

Then each the other did embrace,

And then they started to unlace

Each his helmet and his ventail,

And free his head from the mail.

They left the spot, in great delight,

And the squires who witnessed knight

Clasp knight together thus, in joy,

From a hillside, did their legs employ,

And ran at once to tell the king:

‘Sire, sire, Lord Gawain is coming,

I’faith, he brings the knight to you,’

They cried, ‘and they do show, those two,

The greatest joy in one another.’

There was not one who did discover

The news, and failed to leave the tent,

And rush to be there at that event.

And Kay said to his lord, the king:

‘Thus all the honour in this thing

Goes to your nephew, Sir Gawain;

Hard went the battle, that is plain,

And perilous twas, assuredly,

For he returns of hurt as free

As when he went, I perceive,

And not one blow did he receive,

And no one had of him a blow,

And not one word of challenge; lo

By him are all the honours won,

And let all cry that he has done

What we two could ne’er achieve,

Though we showed there, I believe

All our prowess, and all our might!’

Thus Kay delivered, wrong or right,

His judgment there, as was his wont.

Lines 4510-4578 Perceval makes himself known to all

NOW Lord Gawain who did not want

To bring his new companion armed

Before the court, had him disarmed

By his own squires, within his tent,

And then his chamberlain was sent

To bring a robe from out his coffer

Which he to Perceval did offer.

When he was dressed, in finery,

Both cloak and tunic artfully

Sewn, and suiting him full well,

They went, hand in hand, to tell

The king, who was before his tent,

Of their meeting: ‘Sire, I present

To you,’ declared my Lord Gawain,

‘The very one, whom you would fain

Have met, most willingly, I trow,

This past fortnight, and I avow

Tis he of whom you often speak,

And whom you now go to seek.

I offer him to you, him I bring.’

‘My thanks to you,’ declared the king,

Fair nephew,’ and, so as to greet

Them both, he rose now to his feet.

And said: ‘Fair sire, be welcome here!

I’d have you say, that all might hear,

What name you’d have me call you by.’

‘I’faith, I shall hide naught, not I,’

Said Perceval,’ and thus comply:

Perceval the Welshman am I.’

‘Ah, Perceval, my dear sweet friend,

Since my court you’ll now attend,

I’ll not have you depart once more.

The thought of you has grieved me sore,

Since the first hour I saw you here,

Not knowing the fate, far or near,

For which God had destined you,

Though it was divined, it is true,

As all the court knows now, by rule,

Both by the maiden and the fool,

Struck by Sir Kay the Seneschal.

And you have now confirmed it all,

All that they prophesied about;

Of that none harbours any doubt,

Who, since, of all your chivalry

Has heard the true tale told to me.’

The queen appeared, upon this word,

For she of the whole thing had heard,

Of this knight come from elsewhere;

And when Perceval saw here there,

And he was told that this was she,

And saw the maiden, from whom he

Had won a smile when gazing at her,

He advanced to the encounter,

And said: ‘God grant joy and honour

To the noblest, the fairest ever

Of all the ladies that might be,

As all must say who her do see,

And all who her have e’er espied.’

And thus the queen to him replied:

‘You are more than welcome here,

As a knight whom it would appear

Has proved of fair and high prowess!’

Then the maid greeted their guest,

She who’d once smiled at Perceval;

She embraced him, and he, withal,

Cried: ‘Fair maid, should you have need

Of help, I’ll be that knight, indeed

Who’ll never fail to bring you aid.’

So she thanked him, the fair maid.

Lines 4579-4693 The Ugly Maiden rails at Perceval’s failure

GREAT joy to the queen and king

Doth Perceval the Welshman bring.

With his lords, doth the king recall

Him to Carlion, and thither go all.

And so by nightfall they returned.

All that night to pleasure they turned,

And so again the whole day through,

Till, on the third day, came in view,

A maiden, riding a dun mule, who

Clasped a whip in her right hand.

Her hair, bound in a double strand,

Was thick and black, and if tis true

What the book says of her, then you

Ne’er so ugly a thing could find,

In Hell itself, while, to my mind,

None has e’er seen iron so black,

Who’s been to earth’s end and back,

As the colour of her hands and face,

Yet the rest of her, in every place,

Was worse to view, in every way,

For her two eyes, I have to say,

Were holes as small as any rat,

Her nose that of an ape or cat,

Her lips those of an ox or ass.

For yellow egg-yolk might pass,

Her teeth, the colour was so rich,

And she was bearded, like a witch.

Her chest, before, was but a hump,

Behind, her spine a crooked lump,

And her shoulders and her thighs,

Not made for twirling, I’d surmise,

And, below, of stalks like twisted

Willow-wands the legs consisted.

Full fit was she to lead the dance!

Upon her mule she did advance,

Passing slow before each knight,

And ne’er before was such a sight

Seen at a king’s court; in the hall,

She hailed the king and barons all,

Except for Perceval alone,

Whom she thus declined to own,

But, mounted on the dun mule’s back,

She cried: ‘Ah, Perceval, alack,

Fortune’s locks are bare behind.

Curse the one that you doth find,

And fails to wish you no good,

For you did not, as you should,

Seize Fortune’s locks on sight!

At the Fisher King’s, sir knight,

You saw the lance that bleeds pass,

Yet twas so hard for you, alas,

To open your lips and speak

That you thereby failed to seek

The reason why that drop of blood

Fell from the lance of gleaming wood!

And then, of the grail that you saw,

You asked not what noble lord,

What rich man, one served with it.

Unhappy is he whose sky is lit

By perfect weather yet sits dumb,

And waits for better still to come.

And such are you, the sad disgrace,

Who saw it was the time and place

To speak to him, and yet said naught!

In evil hour, a folly you wrought!

In evil hour, you kept silence so,

Whereas, had you sought to know,

The worthy king, who is unsound,

Would have trod upon the ground,

And, healed, held his realm, in peace,

Of which he’ll hold nary a piece.

And know you, now, what will arise,

Now the king’s denied that prize,

And of his wound is yet unhealed?

Wasteland shall replace the field,

Widowhood be the woman’s fate,

Maidens shall prove disconsolate,

And shall as orphans live, for aye,

And many a knight shall sadly die,

And, through you, all shall come to ill.’

Then to the king she turned, at will,

And said: ‘King, fret not, I must go,

This night your court I must forego

And find me lodgings far from here.

I know not if you’ve chanced to hear,

Men speak of the Castle Orgulous,

Well, I must travel to that fortress.

Five hundred and sixty six knights,

That castle holds, all men of might,

And know that there is nary a one

Has not his lady there, every one

Of them noble, courteous and fair.

This I tell you, for none goes there

Without encountering some fight,

A joust, a battle, to delight,

If he’d do deeds of chivalry.

Should he seek them, no lack there’ll be.

And he who’d win the greatest prize

In all the world, I can apprise

Of the very place, the strip of ground,

Where such winning might be found,

If any would that venture dare.

On the very top of Montesclaire,

There is a maiden has her seat;

With great honour men would greet

Any man who the siege could raise

Free the maid, and reap the praise.

There would be fame seen and felt;

And the Sword with the Strange Belt

He thus could gird about him, too

If God had granted him so to do.’

Then the maiden’s speech ceased,

For she had uttered all she pleased,

And left without another word.

Lines 4694-4787 Gawain is challenged by Guinganbresil

GAWAIN when of that maid he heard,

At Montesclaire, rose, with a cry,

Claiming he’d rescue her, or die.

And Girflet, he the son of Do,

Said, God save him, he would go,

And find the Castle Orgulous.

‘And I to climb Mount Dolorous,’

Said Kahedin, ‘and never rest,

Until I reach its very crest.’

But Perceval spoke otherwise,

Saying while he was yet alive

He’d not lodge two nights together

In one place; nor fail to venture

Through any strange new-heard of pass;

Nor would he fail to surpass,

In battle, any knight who claimed

He was greater than those famed

In fight; nor would he shirk travail,

Until he’d learned, of the grail,

Whom with it was served, and he

The lance that bled again did see,

And to the proven truth was led,

Through being told of why it bled.

Another fifty bold knights there,

Rose to their feet, and did swear,

One to another, gave their word,

That from no fight of which they heard,

Or venture, would they turn away,

Though in some vile land it lay.

And while they spoke of this and more,

Guinganbresil came through the door,

Into the hall, and they made room

For him, when they saw him come.

And he did bear a golden shield,

With a band of azure on its field.

Guinganbresil, who knew the king,

Courteously gave him greeting,

But greeted not Gawain, for he

Accused that lord of treachery,

Calling out: ‘Gawain, you slew

My father, and you did so, too,

Without a challenge, to your shame.

Yours be the reproach, and blame,

Thus I accuse you here of treason,

And it is known to every baron

I’ve uttered not one word untrue.’

At this my Lord Gawain he flew

To his feet, burning with shame,

But Agravain, the Proud by name,

His brother, leapt up, to restrain

Him: ‘For the love of God, Gawain,

Bring not shame on your lineage;

From this blame, from this outrage,

The knight seeks to lay upon you,

I will, I promise, here defend you.’

He said: ‘My own self, and no other,

Must defend me, my dear brother,

For the defence is mine, you see,

Since he accuses none but me.

Yet if I could but bring to mind

But one misdeed, of any kind,

That I know of against this knight,

I’d make amends, seek peace outright,

And do all, that your friends and mine

Might think right, to make all fine.

Yet what he speaks, tis pure outrage,

I’ll prove my honour, see my gage,

Where’er he pleases, here or there.’

He said they’d settle the affair,

Before the King of Escavalon;

Who was, in his opinion,

Far handsomer than Absalom.

‘Then,’ said Gawain, ‘to that kingdom,

I pledge to follow you, sir knight,

And see, there, who is in the right.’

Then Guinganbresil went his way,

While Lord Gawain, without delay,

His preparations did advance.

Then all who had a sound lance,

Or shield, or helm, or fine sword,

Offered it, but he refused, that lord,

To take aught else but was his own.

Seven squires followed him, alone,

And, with each, a mount and shield.

And, now he sought to take the field,

The deepest grief was shown at court;

Torn hair, scarred flesh, faces fraught,

And many a beaten breast remained,

No dame so old but showed her pain,

And, for the knight, revealed her sorrow;

They wept, as there were no tomorrow,

As Lord Gawain went on his way.

Of his adventures, day by day,

Now I shall speak, and you shall hear.

The End of Part III of Perceval