Chrétien de Troyes

Lancelot (Or The Knight of the Cart)

Part III

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Lines 3685-3954 King Bademagu brings about conditional peace.

- Lines 3955-4030 Queen Guinevere is displeased.

- Lines 4031-4124 Lancelot sets out for the Sunken Bridge.

- Lines 4125-4262 Guinevere grieves on false news of Lancelot’s death.

- Lines 4263-4414 Lancelot grieves on false news of Guinevere’s death.

- Lines 4415-4440 Lancelot and Guinevere hear that the other still lives.

- Lines 4441-4530 The lovers are reconciled.

- Lines 4531-4650 The tryst by night.

- Lines 4651-4754 Lancelot in the queen’s bed.

- Lines 4755-5006 Kay the Seneschal, stands wrongfully accused.

- Lines 5007-5198 Gawain at the Sunken Bridge.

- Lines 5199-5256 King Bademagu initiates a search for Lancelot.

- Lines 5257-5378 The forged letter.

Lines 3685-3954 King Bademagu brings about conditional peace

WHEN Lancelot heard the shout,

He was not slow to turn about;

He turned, and there, high above,

The thing which he most did love,

Of all that in the world might be,

At the tower window, he did see.

From the moment that he saw her

He turned not again, nor from her

Moved the direction of his gaze;

Meleagant, in all the ways

He could, forcing the attack,

While Lancelot guarded his back.

Meleagant was filled with joy

Seeing the tactics so deployed;

His folk too were all delighted,

While the foreigners, affrighted,

Could scarce hold themselves upright,

Falling to their knees in fright,

Or lying prone upon the ground;

On one side, glad cries did sound,

But, on the other, shouts of pain.

Then the maiden called again,

From the window, up on high:

‘Ah! Lancelot! Now tell me why

You must behave so foolishly?

You were the height of chivalry,

Indeed, a paragon of virtue;

I never thought it could be true

That God would ever make a knight

Who could match you in a fight,

Or equal your worth and valour.

Now we see you well-nigh waver,

Lashing out with backhand blows,

Behind you, fending off your foe.

Move, so you’re on the other side,

Keep the tower before your eyes,

Such that you’ll not be blamed.’

Then Lancelot felt sore ashamed,

And angry with himself that he,

Had for a while, as all could see,

Suffered the worst of the fight,

Nor fought as fiercely as he might.

So he leapt back and, by force,

Placed Meleagant on a course

Between himself and the tower,

While Meleagant used his power

In trying to regain his place.

But Lancelot runs in apace,

And strikes him so violently,

Upon his body and his shield,

Whene’er he seeks to win ground,

That he is forced to whirl around,

Once or twice, at every blow.

Lancelot’s strength and courage grow,

Partly because Love grants him aid,

Partly because he’s ne’er displayed

Such hatred as towards this man;

With none has he been so enraged

As him with whom he is engaged.

Such love and such mortal hate,

That ne’er before waxed so great,

Made him so valorous and bold,

That Meleagant began to hold

Him in awe, the fight no jest;

For ne’er had he in fierce contest

Known or met with such a knight,

Nor been so wounded in the fight

By any knight, as now by this.

Further danger he would miss,

So must he sidestep and evade,

Hating the blows and half-afraid.

Nor were Lancelot’s threats in vain;

He pushed him to the tower again,

Where the queen watched on high.

Doing homage, he came so nigh

The tower’s wall that he was now

So very close to it, I vow,

That he must cease to see her face

Should he advance another pace.

Thus Lancelot oft drove him so

Hither and thither, to and fro,

In whatever manner he pleased,

And always halting, when he ceased,

Before the queen, his lady fair,

She who had kindled the flame there

Which did make him gaze so on her.

While the flame, in his heart, doth stir

Him so against Meleagant,

He can press him as he wants,

Driving him from place to place!

He leads him to and fro, apace,

Whether he will or no, resigned,

Like a cripple, or one who’s blind.

The king, seeing his son hard-pressed,

Is troubled, and pities his distress,

And would aid him speedily;

Yet to do so courteously

He must ask it of the queen.

So he began: ‘Since you have been

In my keep, Lady, and my purlieu,

I’ve loved, and served, and honoured you,

And naught that could be said and done

Has been willingly left undone

Which might be added to your honour;

Now reward me with your favour.

A boon I’d have you now approve

You should not grant except for love.

My son, pitted against my guest,

Now has the worst of this contest,

Yet not for that reason do I speak,

But that this Lancelot may not seek

His death, having him in his power;

Nor ought you, in such an hour;

For though he has not done well

By you, and wronged him as well,

Yet for me, who do beg you now,

Of your mercy, this boon allow,

That he not seek to kill my son.

For, if you do, then that guerdon

Repays all I have done for you.’

‘Fair sire, I am willing so to do,

At your request,’ replied the queen.

‘For even if my hatred had been

Mortal, toward your son, whom I

Do not love, yet so well in my

Service have you acted, to please

You I’d wish Lancelot to cease.’

And these were not merely words

Spoken in private, but were heard

By Lancelot and Meleagant.

Lovers are ever compliant,

And, where perfect love exists,

Swiftly, and willingly, insist

On what gives their mistress’ pleasure.

So must Lancelot, in full measure,

Who loved more than Pyramus,

If any man could e’er love thus.

Lancelot heard all her speech;

As soon as the last word reached

His ears from her lips, he cried:

‘Such a request I’ll not deny,

Since you wish it, and will halt.’

Now Lancelot dared not assault

His foe, or make the slightest move,

Even though his foe might prove

Hostile, and thus seek his death.

He moved not, scarce drew a breath,

While the other still tried to maim

Him, feeling both wrath and shame,

That they’d been forced to intervene.

For now the king had left the queen

And had descended, to upbraid him,

And entering the list delayed him,

Speaking sharply at their meeting:

‘How now, my son, is this fitting,

That he moves not, yet you strike?

You are too harsh and too warlike;

Your prowess is misplaced indeed,

For without doubt all are agreed,

He’s shown he’s your superior.’

Then Meleagant, in anger,

Choking with shame, replies:

‘You’ve lost the use of your eyes!

I doubt that you could see a thing,

He is blind who dies believing

That I was not the better man.’

‘Find any who think other than

That very thing!’ the king replies,

‘For all the folk here know who lies,

And whether you speak truth or no.’

Then to his barons the king doth go,

And bids them lead his son away

And they in turn make no delay

In carrying out the king’s command,

Departing with Meleagant;

But to draw Lancelot away

Scant force was required that day,

For he would have suffered woe,

Before he’d have touched his foe.

Then the king addressed his son:

‘So help me God, at last, have done,

Make peace, and render up the queen.

This whole quarrel that lies between

You and he must cease today.’

‘What nonsense, you ever say!

A wealth of nothing you declare!

Away! Leave us to our affair,

And do not tangle with our fight!’

Said the king: ‘Such is not right;

Since that this knight would kill you now

If I did leave you, all allow.’

‘Kill me? Tis most certain that I

Will kill the man rather than die,

If you’d but let us fight again;

We would see who conquered then.’

The king replied: ‘Now, yet again,

So help me God, you speak in vain.’

‘Why?’ ‘Since I wish it not,’ said he,

‘Neither in your pride nor folly

Will I so trust, and see you die.

Mad is he who seeks death, say I,

As you do now, unwise I trow.

That you hate me, well I know,

Because I seek to protect you.

God will not let me thus view

Your death, when I wish otherwise;

Too great the grief that would arise.’

His son he reproved, till concord

And peace was once again restored;

The terms of the truce such that he

To surrender the queen must agree,

If Lancelot consented to be

Summoned, and would willingly,

And within a year from the day

Of the summons, its terms obey:

To fight with Meleagant again.

This pact yields Lancelot no pain.

Peace being nigh, folk gather round,

And they suggest the battleground

Should be at King Arthur’s court;

There twas right it should be fought,

He holding Britain, and Cornwall.

The queen must now consent to all,

And Lancelot yield up his promise,

That if Meleagant conquer in this,

She and he must return together,

And none there seek to detain her.

The queen with all this concurred,

And then Lancelot gave his word,

And thus both sides were in accord,

And so resigned lance and sword.

The custom was in that country

That if one prisoner were set free,

All others might quit their prisons;

On Lancelot they rained benisons.

And you might rightfully surmise

That joy now shone in his two eyes,

And so it did, with nary a doubt.

The prisoners stood round about,

And they in Lancelot rejoiced,

Speaking aloud, as with one voice:

‘Sire, to us, in all truth, joy came,

As soon as we had heard your name,

For then we knew with certainty,

That we would thus delivered be.’

A great crowd about him pressed,

Pushing and striving to express

Their joy, and touch him if they could.

And those who succeeded in this

Were overjoyed, such was their bliss.

There was joy there but sorrow too,

For though all those freed from prison

Expressed their joy with abandon,

Meleagant and his countrymen

Saw nothing that delighted them;

All dark and pensive, sad of face.

The king now turned from that place,

Nor was Lancelot left behind,

Who begged him he might find

His way, that instant, to the queen.

‘I shall not fail; she shall be seen,’

Said the king, ‘for it seems right,

And if you wish me to, sir knight,

I’ll show you Kay, the Seneschal.’

Such joy had Lancelot withal,

He well-nigh knelt at the king’s feet;

But they now passed on to meet

The queen, where she sat in state,

In the hall, and did both await.

Lines 3955-4030 Queen Guinevere is displeased

ON seeing the king, who by the hand

Led Lancelot, the queen did stand,

Then curtsied low before the king;

Yet seeming angered at something,

With clouded brow, no word said she.

‘You see here, Lancelot, lady’

Said the king, ‘who comes to view

His queen; that should bring joy to you.’

‘I, sire? Me he cannot please,

To see his face gives me no ease.’

‘Come now, Lady,’ said the king

Courteous, frank, in everything,

‘Why do you adopt this stance?

You are too scornful of a man

Who has served you and loyally,

Such that he has oft on his journey

Exposed himself to mortal danger,

And rescued and defends you ever

Against Meleagant, my son,

Who to you great wrong has done.’

‘Sire, in truth, tis an ill employ;

For my part, I feel no annoy

In saying that I thank him not.’

Now this astonished Lancelot,

Yet he responded, however,

In the manner of a true lover:

‘Lady, though that surely grieves me,

I’ll not ask a reason of thee.’

Thus Lancelot voiced his sorrow,

While the queen his speech did follow,

But so to grieve him and confound

Him, not one word did she sound,

But hence, to her room, did depart.

Lancelot sent both eyes and heart

To the doorway, following after,

But, the nearness of her chamber

Meant his eyes must swiftly lose her;

He would gladly have pursued her,

Had that been possible, I’m sure,

But the heart, which is the more

Lord and master, and doth possess

Much greater power, now did press

On behind her, leaving, sadly,

Eyes full of tears, with the body.

In private now the king addressed

Lancelot; wonder he expressed:

‘What can this mean, how can it be

That the queen should refuse to see,

And is unwilling to speak to, you?

If she was accustomed so to do,

She should not disdain you now,

Nor speech with yourself disallow,

After all you have done for her.

So tell me then, if you know, sir,

Why for you she’s shown, indeed

Such bitter scorn, for what misdeed?’

‘I took no note, sire’ said Lancelot,

‘Yet the sight of me pleases her not,

Nor will she listen to aught I say,

It troubles and grieves me alway.’

‘Surely,’ the king said, ‘she does wrong,’

For you well-nigh risked death not long

Ago for her, amidst certain danger.

Fair sweet friend, let us not linger,

We’ll go speak with the Seneschal.’

He replied: ‘I’ll gladly go withal.’

So to the Seneschal they went.

Straight upon Lancelot’s advent;

The very first word that Sir Kay,

The Seneschal, to him did say,

Was: ‘How you do shame me!’ ‘How so?’

Said Lancelot, ‘that I may know,

Tell me what shame I’ve brought on you.’

‘That you have done what I couldn’t do,

Brings shame on me, as I believe;

For twas a thing I could not achieve.’

Lines 4031-4124 Lancelot sets out for the Sunken Bridge

THEN the king left them together,

And issued alone from the chamber,

And Lancelot asked the Seneschal

If there he’d met with ill at all.

‘Yes, and still do so, I avow,

I ne’er met with such ill as now,’

He said, ‘and I were dead long ago,

If not for the king, who doth show,

Out of his compassion and pity,

For me such kindness and amity,

That he would not knowingly

Let me lack for aught I might need;

For there is not a single thing

That to me they fail to bring,

As soon as he of it doth hear.

But against his goodness, I fear,

Meleagant takes the other part,

His son, all filled with evil art,

Who hath doctors, that here, on hand,

And treacherously, at his command,

Ointments to my wounds apply,

That must destroy me, by and by.

Thus have I father and step-father,

For when the king applies a plaster

To my wounds to do me good,

Wishing to ease me as it should,

So I might be healed completely,

Comes the son and treacherously

Seeking to kill me, then removes

All swiftly, and a traitor proves,

Replacing it with vile ointment.

But that tis not the king’s intent,

I am as certain as I can be:

Such a murderous felony

He’d not in any way condone.

And of the courtesy he’s shown

To my lady, you know naught.

Never did man so guard a fort

As vigilantly, I must remark,

Since old Noah built his Ark,

As he has guarded this lady;

For he forbade his son to see

The queen, though much aggrieved,

Except in courtly company,

Or in his own royal presence.

The honour shown her is immense,

And up to this present moment,

The king, of his mercy, is content,

To grant her all she might devise.

None could devise more, I surmise,

For she devises all that is done.

And the king prizes her, for one,

For the trust in him she has shown.

But is it true, as seems well known,

That she is so angry towards you

That, before all, she has refused

To speak with you, ne’er a word?’

‘The truth, indeed, you have heard,’

Said Lancelot, ‘the thing is so.

But tell me now, if you know,

For God’s sake, why she is displeased.’

Kay replied he could not conceive

The reason, twas wondrous strange.

‘Well let it be as she doth arrange,’

Said Lancelot, twas all he could say,

‘For I must now be upon my way,

And I’ll go seek my Lord Gawain,

Who with me entered on this terrain,

And who agreed that he would go

To the Sunken Bridge; thus I follow.’

He left the room, and swiftly went

To inform the king of his intent,

And asked his leave to go his way.

The king said willingly that he may.

But those that Lancelot had freed

From captivity, by his brave deed,

Asked him what they were to do.

And he replied: ‘All those of you

Who wish may come along with me.

While those of you who’d rather be

At the queen’s side may remain;

Such is your right, I do maintain.’

Those who wished all went with him,

More joyous now than they had been,

While with the queen there remained

Her maids, whom pleasure detained,

And many a knight and lady too;

And yet not one remained, tis true,

Who would not rather have gone

To their own country than stay on.

But thus the queen kept them near,

Waiting for Lord Gawain to appear,

Saying she’d make no move to leave

Till news of him she did receive.

Lines 4125-4262 Guinevere grieves on false news of Lancelot’s death

EVERYWHERE the news doth spread

That the queen from prison is led,

And the captives are now set free,

And may go about at liberty,

As it suits, when and wherever.

All the natives gather together,

Seeking the truth, as to what befell,

And cannot talk about aught else.

And all are angered that, at last,

The perilous ways have been passed,

So all, may come and go, as they please:

And naught is as it was wont to be!

And when the folk of that country

Who knew not, heard of the victory

That Lancelot achieved in the fight,

They took themselves to where they might

Have sight of him as he passed along

Thinking that they could do no wrong

In the king’s eyes, surely, if they

Seized Lancelot, and drew him away.

His men were all unarmed and thus,

When the natives, who waxed furious,

Came at them all armed, no wonder

That Lancelot must there surrender,

Our knight being unarmed also.

A prisoner back now he must go,

His feet tied beneath his horse,

While his men said: ‘You, by force,

Do evil, sirs, for the king’s decree

Protects us; in his safe care go we.’

But they said: ‘Of that we know naught,

But as we have seized you, to the court

You must go, and immediately.’

Then news was brought, erroneously,

To the king that his folk had seized him,

Then bound Lancelot, and killed him.

Great was his sorrow when he heard,

By his head he swore, and his word

Went out, that the killers would die.

No quarter must to them apply,

And, if they could but be found,

They must be hanged, or burned, or drowned.

If with rope, or fire, or water nigh,

They should attempt to deny

The deed, he’d not believe a word,

For, upon his heart, that vile herd

Had brought such sorrow and shame

Disgrace would e’er tarnish his name

If he did not his vengeance take;

Vengeance he’d have and no mistake!

The tidings spread, and flew unseen,

Until their import reached the queen,

Seated there, dining, at her table.

She almost died, hearing the fable,

The false news that had been brought,

Of the death of brave Lancelot;

For she believed what they did say,

And was plunged in such deep dismay

She well-nigh lost the power to speak;

Yet for those around her said, openly:

‘Truly, his death it grieves me much,

And tis not wrong it should do such,

For he did come to this land for me,

And on that account I should grieve.’

Then she murmurs to herself low,

That none can hear her murmur so,

Saying that no one there need pray

Her to eat or drink, that or any day,

If true word of his death they give,

He for whom she alone doth live.

Then she rises, on sorrow intent,

And, to herself, she doth lament,

So that none hears her or takes note.

Now she grasps often at her throat,

As if she is bent on her own death,

And confesses, beneath her breath,

Her own sin, one towards himself;

Blaming, and reproaching, herself,

For the wrong that she has wrought,

Against one whom she has thought

To be her own, and been hers ever,

And had he lived, proved so forever.

So distressed is she by her cruelty,

That it greatly mars her beauty,

For her cruelty and her disdain

Now do prove her beauty’s bane

More than all her vigils together

And her fasting marred it ever.

All her misdeeds, as one, arise;

She reviews them and often cries:

‘Alas! What was I thinking of

When before me stood my love,

That I disdained to greet him there,

And would not hear his words so fair?

When I denied him speech and look,

Was that not pure folly, to brook?

Folly? Rather, so God help me,

All was violence and cruelty.

As a jest I intended it, but no,

No jest; he did not think it so

For indeed he pardoned me not.

None but myself killed Lancelot;

The mortal blow was mine alone.

When all smiling he was shown

To where I was, thinking that I

Would welcome him, by and by,

And not a glance did I bestow;

Was not that then a mortal blow?

When my speech I did him deny,

At once, with that blow then, did I

Rob him of heart and life together.

Those twin blows his life did sever.

No other murderer caused his death.

Dear God! Can I ever, by my faith,

Atone for this murder, for this crime?

Never, indeed, sooner shall time

Drain all the rivers and the seas!

Alas! What comfort it would be,

How it would heal me, if that I

For just one moment, ere he died

Had held him here in my two arms.

What? Naked, laid bare my charms,

The better my joy in him to take.

If he’s dead, twould prove my mistake

Were I not to take my life also.

How can it hurt my lover though

If after his death I am still living,

If I take no pleasure in anything

Except this sorrow I harbour so?

If after his death such grief I know,

Sweet to him, could he see it, this,

This deep sorrow that now I wish.

Wrong is she who would rather die

Than weep for her lover, and sigh.

Surely it is sweeter that I,

In lengthy mourning, grieve and cry.

I’d rather live, and suffer blows,

Than die and in the grave repose.’

Lines 4263-4414 Lancelot grieves on false news of Guinevere’s death

FOR two days the queen mourned so,

And to all food and drink said no,

Until all thought that she must die.

Many are those who will, say I,

Carry bad news rather than good.

The tidings Lancelot understood

Were of his love’s and lady’s death.

Great was then his sorrow, i’faith;

It was clear to all folk that he

Was sad and most melancholy.

Indeed, if you would know the truth

He was so downcast, forsooth,

He held his life as little worth,

Wishing soon to leave this earth;

But first arose his long lament.

A running noose, with sad intent,

He knotted at one end of his belt,

Weeping, sighing the pain he felt:

‘Ah! Death! How you do ensnare me,

And, in my prime, now destroy me!

I am brought low, yet feel no ill,

Except this grief that doth me kill.

This grief is ill, in truth tis mortal.

Yet I would wish it so, withal,

And, if God wills it, I shall die.

Yet is there no other way that I

Can die, without God’s consent?

Yes, if He sanctions my intent,

To place this noose about my neck,

For I may then my own death effect

And, even against Death’s will, die so.

For Death indeed only covets those

Who fear to die, and will come not,

To me, yet with this selfsame knot

I’ll draw Death near, this very hour,

And once I have Death in my power,

Then Death shall execute my wish.

Truly, Death proves too slow in this,

Such my longing to grasp Death now!’

Then no more time doth he allow,

But over his head slips the noose,

Then about his neck, still loose,

And then so its full effect be felt,

Fastens now the end of the belt

Tightly about his saddle-bow,

Such that his men do not know.

Then he lets himself slip down,

So that thus, to his charger bound,

He might be dragged to his death,

Disdaining another hour of breath.

But when the rest of his company

Witness him falling, perilously,

They suppose him to be in a faint,

For none can see the tight constraint

Of the noose looped round his neck.

Swift, in their embrace, they collect

Their lord, supporting him together,

Thus do they all the noose discover,

Which about his throat he’d placed,

Thinking he had Death embraced.

Swiftly the belt they did sever;

The tightness of the noose however

Had done his throat so much harm

That for a while his voice was gone;

The veins in all his neck and throat

Swollen so much he’d almost choked;

Yet now, even if twas his will,

He could do himself no more ill.

It grieved him they had wrought so;

He was consumed with rage also

For he would willingly have died

If they his action had not espied.

Now that he could catch his breath,

He cried: ‘Ah, vile shameless Death,

By God, why had you not the power,

And virtue to slay me ere that hour

When my lady was doomed to die?

Twas because you would not, say I,

Deign to have done so kind a deed,

Spared me, through villainy indeed,

And of you one may expect no less.

Ah! What service and what kindness!

How well you now employ them here!

Cursed be the man who gives you fair

Thanks for such service as this I see!

I know not who’s more my enemy,

Life that makes me weep and sigh,

Or Death that will not let me die,

One or the other torments me so;

Yet, God help me, tis right I know,

That despite myself, I live on.

I should have been dead and gone,

Once indeed my lady the queen

Showed such hatred of me, I mean.

She’d not do so from ill intention,

Rather she did so with good reason,

Although I know not what that was.

But if I’d known what was the cause,

Before her spirit to God ascended,

Then my fault had been amended,

So as to please her, and so richly

She’d have granted me her mercy.

Lord! What could my crime have been?

I think she knew that I was seen

To have clambered onto the cart.

What other crime twas I know not

If not that. That has undone me.

If twas for that she did hate me,

Lord! Why should that deed harm me?

For any who sought to reproach me,

Must indeed know naught of Love;

No mouth should open to reprove

A single thing that for Love is done,

Love that rules lovers, every one.

Tis a mark of love and courtesy,

Whatever one does for one’s lady.

And yet for ‘my love’ I did it not.

Ah, what to call her I know not!

Whether to say ‘my love’ or no,

I dare not call her such, I know.

But of love this I know, I’d deem,

She should have shown no less esteem

For me, if she loved me ever,

But rather called me her true lover,

When an honour it seemed to me

To do whatever Love asked of me,

Even to clamber onto the cart.

She should have charged it to the heart;

For there was proof if e’er there be,

That Love thus tries the devotee,

And so identifies Love’s own.

Yet her displeasure was shown,

At such service; as I discovered,

By the face she showed her lover.

And yet for her he did that deed

For which many others decreed

That he bear reproach and shame.

And for that act me they do blame,

And turn to bitterness my sweet,

I’faith, for such treatment they mete

Out to us, knowing naught of love,

And honour itself shameful prove:

And he who dips honour in shame,

Cleanses it not but soils the same;

They are but ignorant of Love,

Who go thus despising Love,

Who far above Love would appear,

And Love’s commands do not fear.

For, without fail, the better man

Is he who honours Love’s command.

All things are pardonable there;

He’s the coward who does not dare.’

Lines 4415-4440 Lancelot and Guinevere hear that the other still lives

THUS Lancelot doth make lament,

And they all grieve who are intent

On his care, his protection too.

And news arrives as they so do,

That the queen is, in truth, not dead.

Then Lancelot is comforted,

And if he had felt grief before,

Thinking her dead, his joy is more,

A thousand times greater again,

Is this delight than was the pain.

They found themselves that day,

But six or seven leagues away

From King Bademagu’s seat,

And thus the king had receipt

Of pleasing news of Lancelot:

That he had reached that very spot,

And was alive, both safe and sound.

The king, all courtesy, went and found

The queen, and gave the news to her.

And she replied to him: ‘Fair sir,

Since you say it, I know tis true.

An if he were dead, I swear to you

That I would ne’er feel joy again.

For all my joy would turn to pain,

If, in my service, a true knight

Was slain, and he denied a fight.’

Lines 4441-4530 The lovers are reconciled

THEN from her the king did part,

While the queen longed in her heart

To see her love, her joy, again.

She had no wish now to retain

Anger toward him, she confessed.

Then rumour, that never rests

But flies about unceasingly,

Reached the queen, most suddenly,

That, for her sake, Lancelot would

Have slain himself, if he but could.

She feels delight, and thinks it so,

And yet for naught would have it so,

Too great a sorrow it had brought.

But Lancelot had reached the court,

Arriving swiftly, and in haste,

And now the king ran to embrace

Him, and kissed him on sight.

He felt as if he would take flight,

Light-hearted, full of joy was he,

But joy did fade, when he did see

Those who’d made him prisoner.

The king said evilly they’d fare,

For all would now be put to death.

And they responded with one breath

That they had thought he wished it so.

‘Tis I you have insulted though,’

Said the king, ‘clear is his name;

To him you have brought no shame,

Only to me his protector,

Shame is on me, and no other.

You’ll find it no laughing matter,

When your heads are on a platter!’

Lancelot, at this angry speech,

Makes every effort now to preach

Peace and reconciliation;

And his firm determination

Meeting with success, the king

Him to Guinevere doth bring.

Now upon seeing the queen,

He sees she no longer means

To lower her eyes to the floor,

But meets his gaze as before,

Honouring him all she might;

Thus beside her sits the knight.

There they could talk at leisure

Of whatever gave them pleasure,

Nor did their speech fail them,

For Love did there regale them.

And when Lancelot saw that he

Could indeed say naught but pleased

The queen, in confidence, he said:

‘Lady, I wonder why, instead

Of this face, you turned to me

Your other face, when you did see

Me, the day before yesterday,

Nor had a single word to say.

Never a word to me you said,

Such that I was almost dead.

Nor had I the courage to ask

Why I was so taken to task,

As I dare now ask it of you.

For I will make amends, anew,

If you will only choose to say

What fault of mine caused your dismay.’

And the queen spoke again:

‘What? Did you not hesitate, then,

To mount upon the cart, for shame?

Were you not loath to do that same,

And thus for two whole steps delayed?

That, in truth, is why I repaid

You, by denying word or glance.’

‘In future, in such circumstance,

May God save me from like folly,’

He said: ‘may God deny me mercy,

If you were not, then, in the right.

For God’s sake, lady,’ said the knight,

‘At once receive amends from me,

And if I might e’er pardoned be,

Then, for God’s sake, tell me now!’

‘Friend, said the queen, ‘Thus I vow,

That of your guilt you shall be free;

I pardon you most willingly.

‘Lady,’ he said, ‘my thanks to you,

Yet here I cannot say to you

All indeed that I wish to say,

I would speak with you if I may

At greater leisure; soon or late.’

To him the queen doth indicate

A window, with a glance of her eye,

‘Come speak with me,’ she doth reply,

‘At the window, there, tonight,

When you deem all asleep, sir knight.

Come through the garden secretly;

Think not to enter bodily,

Such is not possible, I mean;

You’ll be without, and I within.

Think not that any man may enter;

I may yet touch you however,

With my lips and with my hand.

And, if it please, you understand,

I’ll stay till morn for love for you.

But more than this we cannot do,

For in the room, and close by me,

Lies Kay, the Seneschal, for he

Languishes there, of his wounds.

Closed is the door to the room,

Tightly bolted and guarded well.

When you come, take care, I tell

You, that of you none have sight.’

‘If I can, lady,’ said the knight

I’ll make sure none spy on me,

Who might evil think or speak.’

Thus having talked, heart to heart,

Filled with joy, they both depart.

Lines 4531-4650 The tryst by night

FROM the room went Lancelot,

So joyfully that he forgot

All about his troubles quite,

Yet so impatient for the night,

It seemed that the day was longer

Than if he’d been forced to suffer

A hundred others, or a year.

He would have sought to appear

Before her, if only it were night!

Yet conquering, at last, the light,

A darkness, deep and shadowy,

Wrapped day in its mystery,

To lie beneath its cloak, all hid.

Once of the daylight he was rid,

He feigned to be good and tired,

And claimed he must now retire

For he was much in need of sleep.

But you, who do such vigil keep,

Know that he was merely waiting

For all the folk in his lodging

To think him slumbering in repose.

Yet he would not sleep, God knows,

Nor for his bed hath any care;

He cannot now, nor would he dare

Do so, nor, as he waits the hour,

Desires the courage or the power.

Not long after he rose quietly,

Nor was he disturbed unduly

That moon nor star shone bright,

Nor, in his lodgings, candlelight;

Neither lamp not lantern burned.

Outside, here and there he turned,

But none was there to see him,

All within thought him sleeping,

In his bed throughout the night.

Without an escort thus, our knight

Swiftly went toward the garden,

Meeting none, nor seeking pardon,

And to his good fortune found

A stretch of wall lay on the ground,

Where it had fallen recently.

Through this he passed silently,

And proceeded till he came

To the window, the very same;

There he stood, quiet as you please,

Seeking not to cough or sneeze,

Unmoving, taking every care,

Until the queen arrived there,

In the whitest white chemise,

No coat or cloak had she seized,

But thrown a short cape about her,

Of scarlet cloth and dormouse fur.

As soon as Lancelot saw the queen,

Who at the window-sill did lean,

Behind cruel iron bars stationed,

He gave her a gentle salutation.

And she him greeting did offer,

Both desirous of each other,

Both he of she, and she of he.

They speak no triviality,

Nothing tiresome do they say.

Each to the other strains alway,

As they clasp each other’s hand;

So distressed, you understand,

At being near, and yet so far,

That they curse those iron bars.

But Lancelot claims, boastfully,

That if the queen will but agree

He’ll be inside at once with her,

Nor iron bars keep him from her.

And to him the queen replies:

‘Do you not see their strength and size,

Hard to bend, and hard to shatter?

You could never twist and batter

Pull, or draw them, this I know,

As ever to dislodge them so.’

‘Lady,’ said he, ‘now do not quail!

These bars will prove of no avail;

Naught but yourself will hinder me

From embracing you completely.

If you will but grant your leave

The way is open here for me,

Though if you should not agree

Then is it blocked so utterly

There is no path I might follow.’

‘Your wish,’ she says, ‘is mine, and so

My consent need not detain you,

But, a moment now, restrain you,

Till I may seek my bed again,

That no mischief may you pain;

For twould be no jest, I fear,

If the Seneschal, who lies here,

Hearing a noise, should awake.

It must be right that I betake

Myself to bed, since I do fear

Much ill, should he find me here.’

‘Go then, my lady,’ he replies

But have no fear at all that I

Will make the slightest noise at all;

So soft I’ll draw these bars withal,

And, as I work, such care I’ll take,

That not one person shall awake.’

Lines 4651-4754 Lancelot in the queen’s bed

THEN the queen, silently, withdrew,

While Lancelot prepared to do

His utmost to unbar the window,

Grasping, wrenching, tugging so

That the bars bent at their base,

And he could draw them from their place.

But so very sharp the bars were

That the tip of his little finger

Was sliced almost to the bone,

And then the first joint alone

Of the next was well-nigh severed.

But to the blood, they delivered,

And the wounds he paid no heed;

His mind on other things indeed.

The window’s not so very low,

Yet through it Lancelot doth go,

Most swiftly, and right easily.

There he finds Kay, sleeping soundly,

And seeks the bed where lies the queen,

Whom he adores, and doth esteem

More than the relicts of some saint.

There the queen doth him acquaint

With her embrace, and he doth rest,

Clasped so tightly against her breast,

He’s drawn into the bed, beside her,

Where she her fairest gifts delivers

To him, the sweetest that she can,

And Love and the heart grant a man.

Love would have her treat him so,

Yet, if she loves, he doth also,

A thousand times as much as her;

And Love is lacking in every other

Heart, compared to the love in his,

For Love has so entered into this

Man’s heart, Love doth it so fill,

That all other hearts Love treats ill.

Thus has Lancelot all his wish,

Now the queen doth freely relish

His affection, and company,

Now in his arms he holds her tightly,

And she in her arms him doth greet.

So is their play both fine and sweet;

And such the kisses they employ,

Without a lie, they feel such joy,

A joy so marvellous, that never

Was its equal delivered ever,

Or has e’er been known or heard.

But silence upon it be conferred,

For in story it must not be told.

Of the joys which this pair enfold

The most delightful and choice

Are those our tale denies a voice.

More of such joy and delight

Did Lancelot enjoy that night.

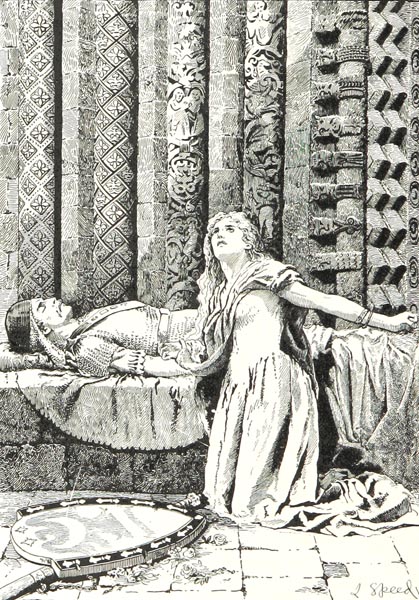

But day comes, sorrow its bride,

For he must leave his lover’s side.

‘But day comes, sorrow its bride, For he must leave his lover’s side.’

The Blue Poetry Book (p140, 1891)

Andrew Lang (1844-1912), H. J. Ford (1860–1941) and Lancelot Speed (1860–1931)

Internet Archive Book Images

On rising, it costs him such pain

To leave her, and depart again,

It seems to him pure martyrdom.

His heart disdains to be gone,

And with the queen doth remain.

He has no power now to reclaim

His heart, for so the queen doth please

It would not have its pleasure cease;

The heart remains, the body goes.

Straight to the window they chose

He returns, but enough remains

Of his body, for his blood stains

The sheets, fallen from his fingers.

Lancelot now no longer lingers,

Departing full of sighs and tears.

No time has been set, he fears,

For them to meet; it cannot be.

He leaves by the window, sadly,

Where he so gladly did enter,

Wounded now in each finger,

So badly had he cut them there.

Yet still the bars he doth repair,

And sets them in their former place,

So that whichever way one face,

Toward the one or the other side,

It seems no one has ever tried

To dislodge or remove the bars.

When from there he doth depart,

He bows, as a man doth incline

Before the altar, or a shrine;

Then goes, in great anguish still,

And meets none he knows until

To his lodgings he doth come.

There, without waking anyone,

He threw himself naked on his bed,

Wondering that his fingers bled,

From the wounds that he’d received.

Yet by these he was not grieved,

For he was certain in his mind

That any wounds that he might find

Were made when he’d drawn the bars.

And he was less concerned by far

Than he might have been if he

Had entered not; would rather be

Lacking both his arms, indeed.

Yet if through any other deed

He had been hurt so grievously,

Sad would he have been, and angry.

Lines 4755-5006 Kay the Seneschal, stands wrongfully accused

NEXT morn the queen lay deep in slumber;

There, within her curtained chamber.

Sweet sleep had overtaken her,

Of the bloodied sheets unaware,

For though stained with Lancelot’s blood,

She knew not but they were good,

White, clean, and presentable.

Now, as soon as he was able,

Up and dressed, all elegant,

To the chamber, Meleagant,

Made his way, and found the queen

Full wide awake, and, readily seen,

Spots of fresh blood on the white.

He showed them to his fellow knights,

Then he, suspecting ill alway,

Looked to the Seneschal, Kay,

And saw his sheets blood-stained,

For that night, I should explain,

All his wounds had oped again.

‘Lady,’ he cried, ‘Now do I gain

Such evidence as I desired!

Truly, in folly is that man mired

Who a woman would confine,

He wastes his effort and his time;

For he who guards her loses her

Sooner than he who ignores her.

A fine watch upon you has kept

My father, gainst me, while you slept!

He has guarded you well from me,

Yet Kay, looking on you freely,

In spite of him, this past night,

Of you had satisfaction quite,

As may be proven, readily.’

‘How?’ she cried. ‘Here I may see,

Blood on your sheets, true witness,

Such that they lead me to express

My conclusion; by them I know,

From this my proof, that it is so;

The spots on your sheets, and on his,

From his wounds, are witnesses.’

Then the queen seeing, as he said,

Bloodstains there on either bed,

Wondered at them, and with shame

She blushed, her cheeks all aflame,

And said: So help me God, the stain

Upon these sheets, I do maintain,

Was not made here by Sir Kay;

But my nose bled ere light of day;

From my nose the blood did fall.’

She thinking it the truth, withal.

‘Upon my life,’ said Meleagant,

‘There is naught in that, I’ll grant;

There is no need for lying words,

For now you’re caught, I do aver,

And the truth I soon shall prove.’

Then he said: ‘Sirs, do not move!’

To the guardsmen standing there,

‘Till I return, do you have care

These sheets remain upon the bed.

I shall have justice, as I have said,

When the king has seen this thing.’

He searched till he had found the king,

And, kneeling at his feet, he cried:

‘Come, see what cannot be denied,

Sire, how your defence has failed.

Come and see the queen you jailed,

See the evidence, true and sound,

For I’ll reveal what I have found.

But ere you go, I pray that you,

Both right and justice there will do,

And that you’ll do so without fail.

You well know the sore travail

I’ve undertaken for the queen,

Yet you my enemy have seemed,

Who under guard keep her from me.

This very morn I went to see

Her in her chamber, and did view

Her bed, and proved it to be true

That Kay lies with her every night.

Sire, by God, am I not right

Thus to be troubled and complain?

Be not angered, for I’m disdained

By one who scorns me, and hates me,

While Kay’s to lie with her nightly.’

‘Quiet!’ said the king, ‘Tis but deceit.’

‘Then come, Sire, and view the sheet,

See the trail Lord Kay doth leave.

Since my words you’ll not believe,

And even seem to think I lie,

Sheet and quilt will meet your eye

Stained with blood from his wound,

All will be still as there I found.’

‘Then, let us go, now,’ said the king,

‘For I wish to verify this thing:

My eyes will judge of the truth.’

So the king goes to see the proof,

Into the chamber, where he finds

The queen who rises, at his sign.

He sees the blood upon her sheets,

And Kay’s alike, and her he greets

With: ‘This is ill, if tis as he said,’

And she replies: ‘God be my aid,

Never, even in dream, has so

Evil a lie been spoken. No,

I’d deem that Kay, the Seneschal,

Is so courteous and so loyal,

He’d ne’er commit such a deed.

As I’d not expose myself, indeed,

In the market-place, no more would I

Offer my body to any that try.

Kay’s not the man for such outrage,

Nor have I wish to encourage

Such a thing, nor would do so ever.’

‘Sire,’ said Meleagant, ‘to his father,

‘I’d be much obliged to you if Kay

For this outrage were made to pay,

And the queen exposed to shame.

Justice I now request and claim,

Justice is yours thus to declare,

Kay has betrayed King Arthur there.

His lord who so believed in him

Had entrusted the queen to him,

The thing he loves most, say I.’

‘Sire, suffer me now to reply,

And exonerate myself,’ said Kay.

When my soul flees, on that day,

May God deny to it His mercy,

If ever I lay with my lady.

I would rather be dead and gone,

Than ever such vile and ugly wrong

Commit toward my lord and master.

And may God never grant better

Health to me than I now possess;

Kill me rather, inflict no less,

If such a thought e’er came to me.

Rather my wounds bled profusely,

As I lay, last night, in my bed,

Thus my sheets they dyed all red.

For that your son doth me indite,

Yet, to do so, he hath no right.’

And Meleagant to him replied:

‘So help me God, devils, say I,

And evil spirits have you betrayed.

Last night, heated and disarrayed,

Your exertions and your excess

Have opened your wounds afresh.

Your denial does you no good,

On both beds the trail of blood

Is evident, your guilt we see.

Right it is that whoe’er may be

Caught, openly, in such a way,

For his crime should swiftly pay.

So famed a knight did ne’er commit

Such baseness, shame on you for it.’

‘Sire, sire,’ to the king, cried Kay,

‘Against what your son doth say

I’ll defend myself and the lady.

Pain and distress he causes me,

Yet he is wrong to treat me so.’

‘To fight my son would harm you though,’

Said the king, ‘you are wounded still.’

‘Sire,’ he answered, ‘though I am ill,

I’ll fight with him, if you so allow,

And prove to all men here, I vow,

That I am not guilty of the shame

With which he would mar my name.’

Meanwhile the queen to Lancelot,

All secretly, her word had got,

And told the king she would send

A knight who would Sir Kay defend

From the charge, gainst Meleagant,

If, in his pride, he’d not recant.

And Meleagant at once replied:

‘There is no knight I e’er espied

I’d shrink from meeting in a fight,

Till one of us be conquered quite,

Not if he were a giant, indeed.’

Then Lancelot appeared, and he

Brought with him such a rout of knights

They filled the great hall outright.

As soon as he had entered, the queen

Told young and old upon the scene

The nature of the thing, and she

Cried: ‘Lancelot, this infamy

Meleagant will impute to me,

And claim I lie, this falsity,

Before all here, to be a fact,

If you do not make him now retract.

Last night indeed, he claims, Sir Kay

Lay with me, for he doth display

My sheets and his all stained with blood.

And says that therefore Kay should

Be charged unless he can defend

Himself, or if he wishes, a friend,

On his behalf, stand forth and fight.’

‘You need not ask it,’ said the knight,

‘Where’er I am, such is your right.

May it ne’er be pleasing in the sight

Of God, that you or Kay should e’er

Be discredited, in this affair.

I’m ready to prove, in battle’s court,

That he ne’er harboured such a thought.

For Kay I’ll fight, with all my power

And defend him mightily this hour.’

Then Meleagant leapt to his feet,

And said: ‘So help me God, I’ll meet

With him, it pleases in all respects,

And let none think that I object.’

Lancelot said: ‘Sir King, before,

I’ve met with lawsuits, and the law,

And with pleas and judgements too.

We should not fight without us two

Swearing an oath, in such a case.’

Meleagant replied, from his place,

And answered him, immediately:

‘I will swear, most willingly;

Bring the saint’s relics ere we fight,

For I know well that I am right!’

And Lancelot answered him again:

‘So help me God, I here maintain,

He knoweth not the Seneschal,

Who’d him, in this, a liar call.’

Then their steeds they demanded,

That arms be sought they commanded;

All was brought prompt to the assay;

The valets arm them; armed are they.

The holy relics are brought to bear,

Meleagant, his oath to swear,

Steps forward, Lancelot equally,

And both men fall to their knees;

Then Meleagant lays his hands

On the relics, as truth demands:

‘So help me God, and this saint,

The Seneschal, tis my complaint,

Lay with the queen, all last night,

And of her, then, took his delight.’

‘And I take you for a perjurer;

He touched her not, nor lay with her,’

Cries Lancelot, ‘and so I swear,

And may a vengeful God not spare

Him who lies, and may he bring

The truth to light anent this thing.

Moreover I will take another

Oath, and swear that, whomever

It displeases and doth annoy,

If this day should bring me joy,

And Meleagant I should conquer,

So help me God and none other

Except the saint whose bones I see,

I’ll show to this knight no mercy.’

But when this latter oath he heard,

The king took no joy in its words.

Lines 5007-5198 Gawain at the Sunken Bridge

ONCE their oaths have been duly sworn,

Their horses, fine and nobly born,

Are brought forward, and proudly shown,

While each man now mounts his own.

Then against each other they ride,

As swiftly as their steeds will fly.

When their steeds are in mid-course

They seek each other to unhorse,

So that not a fragment is left

Of the stout lances that they heft.

Each brings the other to the ground,

Yet their wounds are not profound,

For each knight rises to his feet,

And he the other knight doth meet,

Each with his bright naked sword.

Then sparks from their helms upward

Fly high towards the sky above.

So hot and fiercely do they move,

The naked blades in their hands,

That as now, to and fro, each man

Strikes, encountering the other,

Both are so enmeshed together,

They dare not pause to take a breath.

The king fearful of his son’s death,

Now called aloud to the queen,

Who in the tower could be seen

At a window, watching on high:

‘By God, the Creator,’ thus he cried,

‘Let these two men be kept apart!’

‘Whate’er is dear to your heart,

Replied the queen, ‘in honesty,

Meets no objection from me.’

Now Lancelot it seems had heard

The queen’s answer, every word,

To this request made by the king,

And so he sought now to bring

An end to it, and cease outright;

But Meleagant maintained the fight,

Struck at him, and would not rest.

So the king toward them pressed

And seized his son, who yet swore

He wished no peace, but as before:

‘I seek to fight, no peace for me.’

And the king said: ‘Come, quietly,

Listen to me if you’d prove wise.

No hurt or shame now I apprise

Will come to you if you obey,

And do now as you ought this day!

Recall you not that you agreed

To fight again, and are indeed

Destined for King Arthur’s court?

And see you not that to have fought

And conquered will bring you, there,

Much greater honour than elsewhere?’

Thus the king, to see if he could

So influence him that he would

Be appeased, and the knights part.

While Lancelot, with all his heart,

Wishing to go and find Gawain,

Did, to the king, his need explain,

Asking his, and the queen’s, leave.

And, this granted, taking his leave,

To the Sunken Bridge made his way,

While to accompany him that day,

There followed a host of armed men.

Though he’d have preferred, again,

If most of them had stayed behind.

Down many a road they did wind,

Till the Sunken Bridge was nigh,

A league off, hidden from the eye;

Yet, before they reached the place,

Upon a horse, fit for the chase,

A dwarf it was who came in sight,

Holding a whip with which he might

Spur on his great hunter, at need,

And to the chase incite his steed.

Doing as he had been commanded,

Of the knights, he now demanded:

‘Which of you men is Lancelot?

I’m of your party; hide him not;

For assuredly, be it understood,

I ask you thus for your own good.’

Lancelot replied, in his own right,

Saying: ‘I am that very knight

Whom you enquire for, and see.’

‘Ah! Honest knight, trust in me,’

Said the dwarf, ‘quit this company,

And, all alone, come you with me,

For I’ll lead you to a goodly place;

Let none follow you now apace,

But let them wait here patiently,

Until we return, and presently.’

Lancelot, suspecting no ill,

Bids all his men wait there still,

And after this false dwarf doth fare;

While all his men, remaining there,

Must await him, long time indeed,

For those folk who him have seized,

Wish not to render him again.

His men are in such grief and pain,

At Lancelot’s failure to return,

They know not which way to turn.

They all say the dwarf’s a traitor,

And, sadly, that to enquire after

Him would prove to be in vain.

Yet they begin to search again,

Though how to find him they know not,

Nor where to seek for Lancelot;

So they take counsel together.

Then among them, one or other,

Of the most rational and wise,

Persuaded them, as I surmise,

To go to the Sunken Bridge nigh,

And if they could find thereby

My Lord Gawain, in wood or plain,

With him, renew the search again.

With this they were all in accord;

So much so there was no discord.

Towards the Sunken Bridge they went,

Thus rewarded in their intent,

For my Lord Gawain they saw,

Fallen from the Bridge, before,

Into the water which was deep.

Now he sinks, and now doth leap,

Now they see him, now he’s lost.

But with branches, at the cost

Of some effort, with hook and pole,

They raise him, from the watery hole.

He’d his chain-mail; on his head

A helmet worth more, it is said,

Than ten others; his greaves too,

Stained with sweat, of rusty hue;

For he had suffered much travail,

Of trials and perils great the tale,

Which he had passed and tamed.

His lance and shield yet remained,

With his horse, on the other shore.

Whether he lived they were unsure,

As they dragged him from the depths;

Water he’d swallowed in excess,

And until his lungs were clear

Not a word from him did they hear.

But once the weight was off his heart,

His throat, and mouth, and every part,

And once they heard and understood

All those sounds of speech he could

Deliver, and what they might mean;

Twas news he sought, of the queen,

And whether those who stood around

Had of her gained sight or sound.

And those who answered him replied

That yet at King Bademagu’s side

She remained, and that with honour

He treated her, and waited on her.

‘Has none yet sought for her again,

In this land?’ said my Lord Gawain.

‘Yes’ they answered him. ‘And who?’

‘Lancelot of the Lake, passed through,

O’er the Bridge of the Sword, ere he

Rescued her, and thus set her free,

And with her all the rest of us;

Yet we’re betrayed by a vicious,

Humpbacked, pot-bellied, dwarf,

Who deceived us, without remorse,

Seducing Lancelot away,

Nor do we know now what he may

Have done with him.’ ‘When?’ said Gawain.

‘Today, so wrought that devil’s bane,

Near this place, when with Lancelot

In company for you we sought.’

‘And how has he been occupied

Since in this land he did reside?’

And so their tale began to flow,

All was told him, blow by blow,

Not forgetting a single word,

And thus of the queen he heard,

Who awaited him, ‘and tis true,’

They said, ‘that till she sees you

She’ll not depart from this land,

Till news of you comes to hand.’

My Lord Gawain then replied,

‘When from this bridge we ride,

Shall we not seek for Lancelot?’

Not one of them would rather not,

Preferring to go and see the queen,

And let the king seek him. Between

Them they deem that the king’s son

Meleagant, holds him in prison,

For, treacherous, he hates him so.

Yet if the king comes to know

Of it, he’ll force him to free

Lancelot, of a surety.

Lines 5199-5256 King Bademagu initiates a search for Lancelot

WITH this counsel they all agreed,

And rode away, full swiftly indeed,

Till their company reached the court

Where the king and queen they sought,

And found them with the Seneschal,

Sir Kay, and also that disloyal

Son, so filled with treachery

Who’d caused such great anxiety,

Among those who now arrived.

They feel betrayed, scarce alive,

Sadness on them weighs heavily.

Tis not news filled with courtesy,

That thus brings sorrow on the queen;

Nevertheless she still is seen

To bear herself as best she may.

She resolves to endure the day,

For the sake of my Lord Gawain,

Yet she cannot so hide her pain

As to conceal its hurt completely.

Joy and sadness must mingled be:

For Lancelot, her heart is pained,

And yet, before my Lord Gawain,

She must show an excess of joy.

All must feel sadness, unalloyed,

Who hear the news that Lancelot

Is lost, for such cannot be forgot.

The king indeed would have been

Delighted that he now had seen

Gawain, and made his acquaintance,

Were he not so sad at the absence

Of Lancelot, lost and betrayed,

Which saw him utterly dismayed.

And Queen Guinevere begs the king

To send out men to search for him,

Here and there and up and down,

Without delay, till he is found.

And my Lord Gawain, and Kay,

Beg too, and all, in their array,

Add their prayers and requests.

‘Leave this to me and for the rest

Speak no more of it!’ said the king.

‘I have arranged that very thing;

Without another word or prayer,

He shall be sought for everywhere.’

All bowed to him in gratitude,

While he his own commands issued;

Messengers now scoured the land

The wisest men, of those to hand,

Who went about the whole country

Seeking what news there might be.

They made enquiry everywhere

But no certain news was there.

Finding none they return again

To where Kay and my Lord Gawain

Wait for them, among the knights,

Who all declare, armed for the fight,

Lances levelled, that they will go,

Nor send another to seek him so.

Lines 5257-5378 The forged letter

ON a day, after they had all

Eaten, they armed, in the hall,

And had reached the moment where

Naught was to do but onward fare,

When a valet entered the place,

Passing among them till he faced

The queen, Guinevere, whose colour

Seemed scarcely healthy, however,

For she was grieving for Lancelot,

Not knowing if he lived or not,

So deeply, that her looks were pale.

Then the valet the queen did hail,

And the king who was by her side,

And then the rest who stood nearby,

And Kay and then my Lord Gawain.

He held a letter, that much was plain,

Which he now offered to the king,

Who asked a man of true learning

To read the letter to all those there,

For he, who did its contents share,

Knew how to voice whate’er he read.

Lancelot sent greetings, he said,

To the king as his good master,

And thanked him for the honour

He had done him, and the service,

As one who, on account of this,

Was forever at his command.

The king was now to understand

That he was at King Arthur’s court,

And all safe and sound, in short,

And that he bid the queen come there,

If she would do so, in the care

Of my Lord Gawain and Sir Kay.

In proof of which he affixed that day,

His seal, which they should know, and did.

Much joy was now exhibited:

All the court echoed with delight,

And on the morrow, when twas light,

They said, they would indeed depart.

And so they all prepared to start,

And were ready at break of day.

They rise and mount and are away,

And with great joy and ceremony

The king doth them accompany,

For a good distance on the way.

To the border he doth convey

Their party, and when he has seen

Them safe, takes leave of the queen

And then, indeed, of all the rest.

The queen most courteously expressed

Her thanks for kindnesses received,

To the king, as he took his leave.

She threw her arms about his neck,

Offered and promised her respect,

Her service, and that of her lord:

Nor indeed could she offer more.

And then my Lord Gawain also

Promised his services, and so

Did Kay, as to a lord and friend,

And then the king did commend

Them to God, ere they rode away.

After these three, the king did pay

Respects to all, and turned for home.

Not for a day did the queen roam,

Straying from the road, or tarry,

Until to the court they might carry

News of her, and her company,

News that doth make Arthur happy,

On hearing of his queen’s approach;

He for his nephew has no reproach

But joy at heart and great delight,

Thinking that by his skill the knight

Has brought about the queen’s return;

And Kay’s and all, he hopes to learn.

But the truth was other than he thought.

Emptied is both the town and court,

As all there go to encounter

The company and, all together,

Whether true knights or vassals plain,

Cry: ‘Welcome to my Lord Gawain,

Who brings the queen, in company

With many a once-captive lady

Whom from prison he doth render!’

And Gawain replied, in answer:

‘Gentlemen, now praise me not

Let your compliments be forgot,

For naught is attributable to me.

Such acclaim brings shame on me,

For I reached not the queen in time,

My own delay must seem a crime.

But Lancelot came there indeed,

And has such honour by his deed,

As not another knight has won.’

‘Fair sir, where is he then, the one

You speak of, for we see him not?’

‘Where?’ said Gawain: ‘at the court

Of my lord the king, is he not here?’

‘No, by my faith, he is not, I fear,

Nor in this country for many a day;

For since my lady was led away

Of Lancelot we’ve had no word.’

Gawain, hearing, at once inferred

That the letter was false, and they

Had been deceived and betrayed;

All misled by a traiterous letter.

Then their grief indeed was bitter,

And grieving they came to court.

Where at once King Arthur sought

News concerning the whole affair.

Many a man could tell him there,

All that Sir Lancelot had done,

And how he had freed from prison

The queen herself and all the rest,

And with what treachery his guest

The dwarf had then stolen away.

And all this did the king dismay,

And much sorrow and grief it brought.

But his heart felt joy at the thought

Of the queen’s return, such that he

Found joy eclipsing misery.

Now that he had what he loved best,

He cared little for all the rest.

The End of Part III of Lancelot