Chrétien de Troyes

Lancelot (Or The Knight of the Cart)

Part II

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Lines 1841-1966 The marble tomb.

- Lines 1967-2022 The father and son, and the maid, depart

- Lines 2023-2198 The Knight of the Cart acquires new companions.

- Lines 2199-2266 The Pass Of Stones.

- Lines 2267-2450 The Knights of Logres invade the country.

- Lines 2451-2614 Fresh lodgings and an encounter.

- Lines 2615-2690 The Knight of the Cart accepts a challenge.

- Lines 2691-2792 The Knight of the Cart defeats his opponent.

- Lines 2793-2978 A maiden seeks the defeated knight’s head.

- Lines 2979-3020 Approach to the Bridge of the Sword.

- Lines 3021-3194 The crossing.

- Lines 3195-3318 King Bademagu and his son Meleagant disagree.

- Lines 3319-3490 King Bademagu offers the Knight of the Cart his aid.

- Lines 3491-3684 The knight is revealed as Lancelot of the Lake.

Lines 1841-1966 The marble tomb

THEREUPON the knight of the cart

Turned, and prepared to depart,

For in the mead he would not stay,

And thus he led the maid away.

Swiftly, at full speed, they rode,

The father and son both followed.

Through the mown fields they went,

Till, with mid-afternoon’s advent,

They came upon a place full fair,

A church, and by the chancel there

A graveyard bordered by a wall.

Circumspect, respectful in all,

The knight into the church went;

To pray to God twas his intent;

While the maiden held his horse,

Until his return in due course.

When he had made his prayer,

And while returning to her there,

An aged monk thus met his eyes

Who’d come upon him likewise.

As they met, the knight politely

Asked what that place might be

Since to him twas all unknown.

The monk said that the wall of stone

Enclosed a graveyard; he replied:

‘So help you God, show me inside.’

‘Willingly, sir,’ the old monk said.

And, the monk going on ahead,

Entering, he saw the finest tombs

You’d find as far as Pampelune,

Or Dombes, and letters there were cut

On every tomb, at head and foot,

Giving the names of those who’d lie

Within the tombs there, by and by.

And he himself began to read

The names in order, so decreed,

And found: ‘Herein will lie Gawain’,

And here ‘Louis’, and there ‘Yvain’.

And, after these three, thus the names

Of many another dear and famed

Knight, the most prized, and the best

Of this land, and of all the rest.

Among the others, one he found

Of marble, among those around

New, richer, finer than them all.

The knight then to the monk did call,

Saying: ‘What purpose do they serve,

These tombs, here?’ The monk observed:

‘You have viewed the writing there;

If you’ve deciphered it with care

What’s written there you’ll recognise,

And what each tomb thus signifies.’

‘The largest of them, long and wide,

What is its meaning?’ He replied,

‘I’ll tell you truthfully, that tomb,

‘So large the ground it doth consume,

Surpasses every other made,

So richly carved, and so arrayed,

None other finer can be shown;

Inside and out tis fine, you’ll own.

Yet none of that is your concern,

Tis naught to you, as I discern;

For you shall never see inside.

Seven huge strong men, at its side,

Would be needed to lift the lid,

If to ope it any man would bid.’

For that lid is of heavy stone,

And to raise it, I’ll make known,

Seven strong men it would need,

Stronger than you or I, indeed.

And there are letters written there:

“Who lifts this stone,” they declare,

“And that solely by his own strength,

Will free all those women and men

Who are imprisoned in this land,

Of whom nor slave nor nobleman

Who is not born of this country

Can escape from their captivity;

All strangers are imprisoned so,

While natives they may come and go,

In and out, however they please.”’

The knight of the cart now seized

The stone, and raised it easily,

As if it weighed naught to such as he,

More readily indeed than any ten

Men might do, being thus bidden.

The monk was utterly amazed,

And nearly stumbled as if dazed,

In bearing witness to this marvel;

For he had ne’er seen aught to equal

This wonder all his days before.

He cried: ‘Good sir, I do implore

You to reveal your name to me;

Will you disclose it?’ ‘No, truly,

I’faith, I will not,’ said the knight.

‘That saddens me, for if you might,’

The monk said, ‘twere a courtesy,

And you some benefit might see.

Who are you now, and from whence

Do you come, and travel thence?’

‘I am a knight, as you can see,

The realm of Logres my country,

And such is all I choose to say;

But you, for your part, tell me pray,

Who within this tomb shall lie?’

‘Sire, he who liberates, say I,

All held in this realm in prison,

From which escape there is none.’

When his tale was done and ended,

The knight right promptly commended

The monk to God and all his saints,

Feeling, thus free of all constraint,

He might return now to the maid;

While the aged monk then made

To escort him from the church.

He thought to resume his search,

And, while the maiden mounted,

The monk, at her side, recounted,

Faithfully what the knight had done

Within, praying her, if twas known,

To tell him the knight’s true name;

Yet, she replied, of that very same

She had no knowledge, but one thing

She, indeed, could say concerning

Him: where’er the wind did blow

None such as he did come and go.

Lines 1967-2022 The father and son, and the maid, depart

OF the monk the maid takes leave

And after her the knight doth weave.

Now arrive the father and son,

Following after, who see the monk,

Standing beside the church alone.

The aged knight, in courteous tone,

Asks: ‘Sir, tell us now, if you might,

If you, perchance, have seen a knight,

Accompanied by a maid, go by?’

‘I’ll not be loath,’ is his reply,

To tell you all that I have seen,

For they not long ago have been

Where you are; the knight, within,

Performed so wondrous a thing

As to raise high the lid of stone,

That tops the marble tomb, alone,

Without the slightest sign of strain.

He’s gone to seek the queen, again,

And he will doubtless rescue her

And, with her, all the others there.

That twill be so, to you is known,

For you have read upon the stone

The letters that are written there.

There was never knight, I swear,

Born of woman, who sat a steed

Was equal to this knight indeed.’

Then turned the father to his son:

‘How seems it now? Is he not one

Full worthy who performs this feat?

Who’s in the wrong you may see:

You well know if twas you or I,

I’d not have you fight this knight,

For all the city of Amiens;

And yet you’d struggle on and on

Before relinquishing your aim.

We may as well return again,

For great folly it would be

To follow him, it seems to me.’

His son conceded: ‘I do agree:

To follow would be vanity.

If it so please you, let us go!’

And wise they were in doing so.

Meanwhile the maid doth ride

Close by the knight’s left side,

Striving to make him heed her,

Seeking his name to discover;

She asks him to speak it plain,

Begging him, time and time again,

Till, all annoyed, he answers her

‘Have I not but now made it clear,

Of Arthur’s realm I am, no less?

I swear, by God and his goodness,

That my name you’ll never know!’

She bids him give her leave to go,

That she might thus return, and he

Grants her request right willingly.

Lines 2023-2198 The Knight of the Cart acquires new companions

THEREON the maiden did depart,

While till late the Knight of the Cart

Rode on, free of her company.

After vespers, near compline, he

Saw, as he his road pursued,

A knight approaching, who issued

From the hunt in a wood nearby.

His helmet-mail was all untied,

And on a great steed he did ride

To which the venison was tied,

That God had granted him to take.

The hunter swift his way did make

Towards the knight, to whom he

Now offered hospitality:

‘Night,’ he said, ‘will soon be here;

Time to seek lodgings that is clear,

And you being here upon my land

I have a house quite near to hand,

To which I thus might lead you now.

None has lodged you better, I vow,

Than I have the power to do;

I’d be pleased, if it pleases you.’

‘I should be pleased indeed,’ said he,

So his host, immediately,

Sent his son ahead to prepare

The house, and devote all his care

To making sure supper was ready.

Without delay, the lad gladly

Ran to execute his command.

Right willingly he set on hand

The preparations, while the rest

Followed on, host, maid and guest,

Wending their way, all leisurely,

Till the host’s house they did see.

The host it seems shared his life

With a most accomplished wife,

And five sons he held most dear,

Two were knights it would appear,

And two daughters, noble and fair,

Who were maids, still in his care.

None of them were native-born,

But were from their country torn,

And held in durance many a year,

For they were prisoners of fear,

Who hailed from the realm of Logres.

When his host, at his own request,

Had led the knight into his court,

His lady ran out to meet her lord

And all his sons and daughters too,

Vying in their efforts to do

The guest honour, on their account,

Greet him, and help him to dismount.

His five sons and his daughters

Gave scant attention to their father,

Knowing that such was as he wished.

But warmly they honoured their guest.

Once they’d eased him of his armour,

One of his host’s fair daughters

Draped a mantle about his shoulder

That did her own shoulders cover.

I need not say that, at supper, he

Was served well and fulsomely;

And when the meal was at an end

They showed no hesitation then

In speaking of matters various.

Firstly, his host proved curious

As to the knight’s own origin,

His land, and with that did begin,

Yet he asked not after his name.

The knight responded to this same:

‘From the realm of Logres am I,

And never before have cast an eye

Upon this land.’ And when his host

Heard this, then he did appear most

Troubled and worried for his guest,

His wife, and children too, distressed.

For then indeed, his host did say:

‘Woe that you came here, this day,

Fair sir, trouble will come to you!

For, like ourselves, to servitude

And exile you will be reduced.’

Said the knight: ‘Then, whence come you?’

‘From your land, sir, we have come,

And, of that land, is many a one

Now imprisoned in this country.

Accursed may such customs be,

And those who do them maintain!

For here no stranger ever came

Who was not forced to remain,

Whom this country did not detain.

Who so wishes may enter here,

But must remain, year upon year.

Of you own fate you may be sure:

Doubtless, you’ll depart no more.’

‘Be sure I will,’ the knight replied,

‘If I can,’ but his host now sighed:

‘What? You think to depart still?’

‘Yes, if it should be God’s will;

And I do all within my power.’

‘Well then, at that very same hour

All the others would be set free,

For when one man genuinely

Issues forth from out this prison,

All the others without question

Unchallenged, may do the same.’

Then the knight’s host explained

That he indeed had heard it said

That a great knight, to virtue bred,

Had made his way into that land,

Seeking the queen, whom Meleagant,

The king’s son, had there detained;

And said to himself: ‘I do maintain

That this is he, and will tell him so.’

So said: ‘Hide not from me, though,

Sire, aught of your purpose here,

On the understanding, be you clear,

I’ll give you the best advice I can.

I myself will gain, you understand,

If you indeed achieve success.

Tell me the truth,’ he begged his guest,

‘For your own benefit and mine.

I think you have come, by design,

Into this land to seek the queen,

Among these heathen folk, I mean,

Who are far worse than Saracens.’

And the knight answered him again:

‘I came here for no other reason.

I know not where my lady’s prison

Might be, but I would rescue her.

Good advice I lack, in this affair;

Give me wise counsel if you can.’

His host replied: ‘You have on hand

A grievous task, sire, for the way

You travel will take you, this day,

Straight to the Bridge of the Sword.

Advice you need, of that I’m sure:

If thus my counsel you will take,

To that bridge your way you’ll make

By a more certain path, and fair,

And I’ll see you escorted there.’

He who the most direct path sought:

Then asked: ‘Is that road as short

As the other way that I may go?’

And his host answered him: ‘No,

The path is longer, but it is sure.’

And he said: ‘Tell me no more

Of it, then, but instruct me now

In that other which I will follow.’

‘Sir, truly there you shall fare ill:

If to take the other path you will,

Tomorrow you will reach a pass

Where you’ll find sorrow, alas;

Its name is: The Pass of Stones.

The troubles that passage owns

Would you that I told you now?

A horse’s width it will allow,

Two men cannot go side by side;

So guarded is it, none can ride

There safely, and so well-defended.

Your journey may soon be ended

The moment you reach it; know

You will encounter many a blow

From lance and sword, and render

Many, before you travel yonder.’

Yet, when the host’s tale was done,

His son then spoke, and he was one

Who was a knight, to this effect:

‘If, father, you do not object,

With this lord now I shall go.’

And another of his sons arose

And cried: ‘Then, I will go also.’

And the father gave leave to both,

Willingly yielding his consent.

Now, accompanied, as he went,

Our thankful knight would be,

Right pleased to have their company.

Lines 2199-2266 The Pass Of Stones

THE conversation over, they led

The Knight of the Cart to his bed;

And he was glad to take his rest.

At daybreak he rose and dressed

As soon as ever it was light,

And the son who was a knight,

Rose also, as did his brother.

The two knights donned their armour,

Took their leave, while they were led

By the young brother who rode ahead,

And in company they took their way

Till to the Pass of Stones came they;

The hour of prime was close at hand.

A tower in the midst did stand,

Where was placed a man on guard.

As they approached it from afar,

He on the tower espied the three;

Seeing our knight, he cried, loudly:

‘He comes for ill! He comes for ill!’

And then they saw, armed to the hilt

In bright armour, a mounted knight

From the tower come forth to fight,

And two servants, one either side,

Carrying axes, strode there beside.

And as the company neared the pass,

He who defended that crevasse

Reproached the Knight of the Cart:

Crying: ‘Vassal, full bold thou art,

And foolish indeed must thou be

Thus to have entered this country.

No man should ever venture here

Who in that cart did e’er appear;

And may God ne’er grant him joy!’

Then both did their spurs employ,

And drove their steeds full hard,

And he who the pass did guard

Shattering his lance, at a stroke,

Let fall the remnants, as it broke;

While the other his lance did wield

To strike the neck above the shield,

Throwing his foe to the stones

Leaving him lying there to groan.

Then the axe-men at once up-rose

Yet sought not to land their blows,

Not wishing to harm him indeed,

Neither the knight, nor his steed.

And the knight perceiving that they

Declined to strike him in any way

Showing no wish to do him harm,

Drew not his sword nor gave alarm,

But passed on by them, full swiftly,

And, after him, his company.

And then the one axeman cried

To his fellow: ‘No such knight

Have I seen, for he has no peer.

Wondrous tis what we saw here,

That a passage he made by force!’

‘For God’s sake, spur your horse,’

Cried his brother to the younger,

‘And hasten on then to our father,

And tell him of all this adventure.’

But the lad swore he’d not venture

To carry the message back, not so,

He would not leave the knight to go,

Till that knight had dubbed him true,

And had rendered him a knight too.

Let him take the message and go,

If his brother cared about it so.

Lines 2267-2450 The Knights of Logres invade the country

SO the three rode on together, there,

Till nearly nones, the time of prayer.

And, towards nones, they did see,

One who asked who they might be

And they answered: ‘Knights, who fare

Here, busy about our own affairs.’

And the man said to the knight:

‘Hospitality I offer this night

To you and all your company.’

This he said to the one that he

Took to be the lord and master,

Who replied: ‘I seek no shelter

At this hour; for tis not right

That any man doth rest ere night

Or at his ease in comfort lies

When set on some great enterprise.

And such business I have on hand

As yet I stay not, you understand.’

And the man answered him thus:

‘My house is not so near to us,

Some little distance tis away;

You would arrive at close of day

And find good lodging, as I state;

When you reach it, twould be late.’

‘Then I’ll go thither,’ the knight said.

At which the man went on ahead,

Leading them on, along the road.

And, after him, the three knights rode.

And when they had gone some way,

They met a squire, while yet twas day,

Who was galloping along that road,

And the mount the squire bestrode

Was like an apple plump and round.

He to the man did warning sound:

‘Sire, sire, come you on, in haste,

For those of Logres come against

This land, and all the people here,

And they commence a war, I fear;

Already there is battle and strife,

And they declare, upon my life,

A knight has entered this country

Who has been in battles a-plenty;

Nor can his passage be denied,

Wherever he wishes he will ride,

All let him pass, reluctantly.

They say that those in this country,

All who are captive, he will free;

While we shall endure captivity.

So take my counsel and make haste!’

Thus after him the man now raced.

But the three knights felt delight,

They were now eager for the fight,

Hearing this, and to aid their side.

And the elder son, he loudly cried:

‘Sire, you heard what the squire said.

Let us then gallop on ahead,

And aid our people in their fight!’

Meanwhile the man had fled outright,

Never pausing, whilst heading for

A fortress high which rose secure

Upon a hill, well-fortified,

And to its gate did swiftly ride,

As after him the others pounded.

This high fortress was surrounded

By a great wall, and moat beside.

The moment they were all inside

A portcullis fell, at their heels,

That the passage-way did seal

Behind them, offering no escape.

‘On, on!’ they cried, ‘in this scape

We must not linger.’ On they rode

After the man, and at speed did go,

Till they came to where it ended,

An exit, which was undefended;

Yet as soon as the man was through

A portcullis appeared there too,

Closing the passage to the three.

They were much dismayed to see

Themselves caught in such a plight,

Thinking themselves enchanted quite.

But he of whom I shall say more

A ring upon his finger bore,

Whose stone was of such virtue

That those who held it in their view

Saw through all enchantment’s lies.

He held the ring before his eyes

And, gazing at the stone, said he:

‘Lady, ah, God help me, lady,

Of your aid have I great need;

If you can aid me now, indeed.’

This lady was of faery kind,

She had to him the ring assigned,

And cared for him from infancy.

In what place he e’er might be,

He had true confidence that she

Would bring him aid in misery;

Yet after gazing on the ring,

And upon his lady calling,

He knew enchantment was there none

And all was real that had been done,

And they shut in, and prisoned hard.

Yet they found there a postern barred,

A doorway, both low and narrow.

Drawing their swords together, lo,

They struck with the blades so hard,

All at once, they shattered the bar.

They saw, on exiting the tower

A battle had begun that hour,

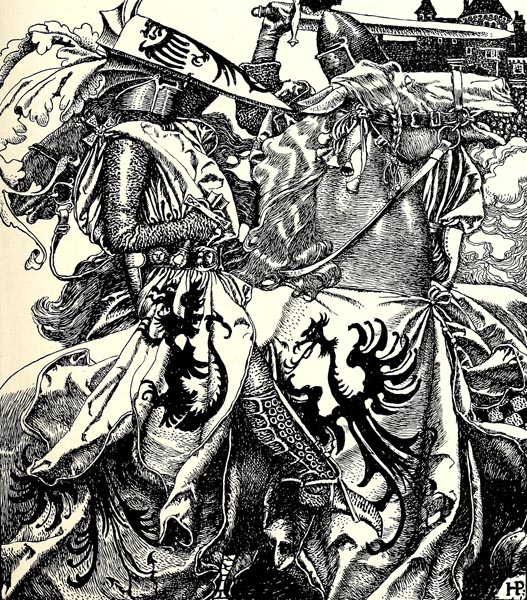

‘They saw, on exiting the tower A battle had begun that hour’

The Romance of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table (p15, 1917)

Sir Thomas Malory (15th cent), Alfred William Pollard (1859-1944), Arthur Rackham (1867-1939)

Internet Archive Book Images

In the meadows, fierce and hot,

And a thousand knights, God wot,

Fought on one side and the other,

Beside the mass of foot-soldiers.

While descending to the meadow,

Both wise and temperate did show

The elder son, who now did say:

‘Ere entering the field this day,

It would be wise, I think, to know

By enquiry, which side below

Is ours, and where our people are.

I am not certain, but near or far

I will go wander, and ascertain.’

‘I wish you would so and again

Return to us, and that directly.’

Swiftly he went, returned as swiftly,

And said: ‘Good fortune serves our turn,

For I was able to discern

These are our troops, on this side.’

Then the knight at once did ride

Straight into the thick of the fight,

Encountered an advancing knight,

Jousting with him, struck his head

About the eye, and left him dead.

‘Struck his head About the eye, and left him dead.’

The Blue Poetry Book (p106, 1891)

Andrew Lang (1844-1912), H. J. Ford (1860–1941) and Lancelot Speed (1860–1931)

Internet Archive Book Images

Then the younger son dismounts

And seizes the dead man’s mount;

Then the armour he doth possess,

Cladding himself with adroitness.

And once clad, he takes the field,

Mounting, grasps the dead man’s shield,

The painted lance, strong, and heavy,

Straps the sword to his side swiftly,

A sharp blade, and gleaming bright,

Following his brother and the knight

Into the melee there obtaining;

His lord the knight maintaining

Himself right well for a great while,

Shattering, rending shields in style,

And bright helms, and coats of mail.

No wood or steel slowed his assail,

He left there, defenceless, instead,

Unhorsed, the wounded and the dead.

Unassisted, so well he wrought

That he discomfited all he fought,

While the brothers did as well as he,

Those two who kept him company.

The folk of Logres marvelled then

Not knowing him, and asked his men,

His host’s sons, who he might be.

Such the demands, and: ‘This is he,

Gentlemen,’ they gave answer, ‘who

Will end our exile, the misery too

Endured in this captivity,

Where we’ve long languished unfree;

Honour on him we should bestow

Since, to free us from prison so,

Many a peril he has passed

And many more shall, ere the last.

Much will he do and much has done.’

All were delighted now, bar none;

Upon hearing all that they said,

All rejoiced, thus the news spread,

Travelling so swiftly, all around,

Everywhere the word did sound,

Till all had heard and all men knew.

With all the joy that did ensue

Strength and courage rose anew,

And many an enemy they slew,

Working such great havoc there,

It seems to me, in that affair,

Because of one knight’s deeds, rather

Than those of all the rest together.

And had nightfall not been so near

They’d have slain them all tis clear;

But night came on, and so dark a night

That they were forced to end the fight.

Lines 2451-2614 Fresh lodgings and an encounter

THEN those defeated in the fight

They all pressed about the knight,

Gathering round him as he did ride,

Grasping his reins, on either side,

And thus they all began to choir:

‘True welcome be to you, fair sire.’

Each saying: ‘By my faith, sir knight,

You shall lodge with me tonight;

By God sir, by his holy name,

No other lodging shall you claim.’

What each says they all do say,

Wishing to lodge the knight that day,

Both the youngsters and the old,

Crying, a multitude all told:

‘Better with me than lodge elsewhere.’

So each claimed, before him there,

And they, all jostling one another,

Sought to claim him from each other,

And, with that, almost came to blows.

Then he declared, to act like foes

Was great foolishness, pure folly.

‘Now cease,’ he cried, ‘this rivalry,

That does no good to you or me.

Among us let no quarrelling be,

Rather go lend each other aid.

No outcry should you have made

In seeking to lodge me, instead

You should seek, as I have said,

To lodge me now in such a place

That all may benefit, then haste

Me thence upon the way I go.’

Then they all, as one, did bellow:

‘At my house then! No, at mine!’

‘Say nothing more, for I decline,’

Said the knight, ‘and add no fuel,

For the wisest of you is a fool

To set yourself to arguing there.

You should advance my affairs,

Yet you seek to divert my aim.

If you have one and all the same

Intent concerning me in this,

To do me such honour and service,

As any man was ever shown,

Then I, by all the saints in Rome,

Could be no more obliged to you,

Than I am now, and do so express.

God give me health and happiness,

Your intentions please me as much

As if you each had shown me such

Kindness and honour here, indeed;

So let the wish stand for the deed.’

He appeases and woos them so;

Then to a knight’s house they go

At their ease, to grant him lodging,

And there they all seek to serve him.

They do him honour and service,

Each deriving great joy in this,

All evening till bedtime is near,

For they all hold him most dear.

At dawn when it is time to leave

Each seeks to join his company,

Presents himself, and so offers,

But tis not his wish or pleasure,

That any man with him shall go,

Except the two sons of his host

Whom along with him he’d brought;

With them alone, the way he sought.

All that day, from early morning,

They rode on, until the evening,

Meeting not with any encounter.

Yet when issuing, however,

From a forest, galloping along,

A knight’s manse they came upon,

His wife there, seated by the door,

Who seemed a fine lady and more.

And as soon as ever she did see

The approach of the knights three,

She arose from her seat to meet

The travellers, and them did greet,

With delight, saying: ‘Welcome all!

Be pleased to enter now my hall;

Here is lodging, and so descend!’

‘Lady, to your command we bend,

Descend we shall,’ said the knight,

‘Grateful to lodge here this night.’

They descended, and as they did

Their mounts were led as she bid

To the stables; here all was order.

Then she called her sons and daughters;

To her side swiftly they did run,

Handsome and courteous the sons,

And the daughters they were fair.

Then she bade the lads take care

To unsaddle and groom the steeds;

None would disobey her indeed,

But did good service willingly.

The knights they disarm all three,

The daughters assisting readily;

The armour removed, they swiftly

Bring them short mantles to wear,

Leading the three men, then and there,

Into the manse, full large and fine.

Its lord was absent at that time,

Out in the woods, and also there

Two of his sons with him did fare;

He soon returned, and all did run,

Being well-mannered every one,

To greet their master at the door.

The venison the three men bore

They soon removed and untied,

Crying the news to him, inside:

‘Sire, sire, though you know it not yet,

Three fair knights have you for guests.’

‘God be praised for that,’ said he,

Then he and the two sons, all three

Glad welcome to their guests display;

All the household, without delay,

Even the least of them, prepared,

To perform their functions there.

Some seek to hurry the meal along,

Others light candles, and bring on

Towels and basins so as to offer

Their guests the use of clean water,

With which they might wash their hands,

As all do gladly where they stand.

Having washed, all take their seats,

Not one thing the hosts complete

Seems a trouble or burdensome.

But, as the meal begins, doth come

A knight who waits outside the door,

Prouder than a bull, equipped to gore,

Such being a most proud beast indeed;

For he sits there, upon his steed,

Fully armed from head to toe.

One foot is in the stirrup below,

The other foot is jauntily placed

Along his horse’s neck with grace,

Thus adding to his careless air.

Behold, this knight advanced there,

Though none saw him or took note

Till he was before them, and spoke:

‘Who is that man, I seek to know,

Who such pride and folly doth show,

Who possesses such an empty head

He comes to this land, being led

To cross o’er the Bridge of the Sword.

Yet all his effort shall be ignored,

And all his journey prove in vain.’

Then he, who felt for this disdain

No fear, with confidence replied:

‘I’m he who o’er the Bridge would ride.’

‘You? You? Dare you dream it so?

You should consider e’er you go,

Before you undertake this thing,

The end to which tis bound to bring

All this intent of yours and you,

And think on the memory too,

Of the cart on which you rode.

What pain you feel I cannot know

At how you were transported there,

But no wise man in this affair

Would dare now to show his face,

If he felt shame at such disgrace.’

Lines 2615-2690 The Knight of the Cart accepts a challenge

AT all that was said and heard,

He deigned not to say a word;

But the master of the mansion,

And the rest, with good reason,

Now openly expressed wonder,

‘Ah, God, such misadventure!’

Each to himself said, inwardly,

‘Now cursed be the hour, utterly,

That hateful cart was first conceived,

A vile thing was thus achieved.

Ah God, of what was he accused?

And by the cart was thus abused?

For what crime was he to blame?

All his days he’ll bear the shame.

If of reproach he now were free

In all the world there could not be,

However his prowess were shown,

Such a knight, both seen and known,

To equal this knight now in merit.

Indeed, to tell the truth of it,

If all fine knights were compared

None were as noble or as fair.’

Thus all folk in common sighed.

But the newcomer, full of pride,

Recommenced that speech of his:

‘Sir knight, now, who, hearing this,

To the Bridge of the Sword do go:

If you would cross the water so,

Most safely and most easily,

I’d have you do so, and swiftly,

For in a skiff you may ride.

But, when you reach the other side,

For that trip I’d have you pay,

And take your head then, I may,

Or hold you there at my mercy!’

Our knight replies he doth not seek

Any trouble or misadventure;

He his head will not so venture,

Nor risk the passage so, for aught.

To which the other makes retort:

‘Since you will not have it so,

Whoever’s be the shame and woe,

You must come forth, willingly,

And fight hand to hand with me.’

To content him, our knight said:

‘If I could refuse, I would, instead,

Most willingly decline to fight,

But I would rather do what’s right

Than be forced to commit a wrong.’

Rising from the table, ere long,

Where they were sitting, the knight then

Made request of the serving-men

To go, quickly, and saddle his steed,

And seek out his arms, with speed,

And bring to him his armour there.

They performed his orders with care;

One now saddled and brought his horse,

Another armed him and, in due course,

Mounted, fully armed, he appeared,

Know you, clad in his warlike gear,

Grasping his shield by the leathers,

Astride his steed, like one forever

Destined, to be, where’er men dare,

Counted among the brave and fair.

His steed seemed to be his alone,

It suited so, twas as if his own,

As seemed the shield he gripped, they said;

And the helmet, laced to his head,

Seemed to cleave to it so well

You’d have been hard put to tell,

That the helm might borrowed be;

For he’d have pleased you so that he

Was born to it, you’d have inferred.

For all this you may take my word.

Lines 2691-2792 The Knight of the Cart defeats his opponent

OUTSIDE the gate, on open ground,

There is a fitting place to be found,

Where the encounter is to be.

As soon as they each other do see,

They meet each other full swiftly,

Coming together right furiously,

Dealing such blows with the lance,

The weapons break at their advance,

Flying to pieces, each splintering.

Then to their good swords retreating,

They hew at helm and mail and shield,

‘They hew at helm and mail and shield’

St. Nicholas [serial] (p44, 1873), Mary Mapes Dodge (1830-1905)

Internet Archive Book Images

Slicing the wood, shearing the steel,

Dealing each other many a wound.

Such fell blows they land these two

Tis as if they’ve struck some pact;

While many a blow upon the back

Of one mount or the other falls,

Till the blades are wet with blood,

Bathing their flanks with a flood;

Such that of both steeds they dispose,

Each falling dead beneath their blows.

Once their feet are on the ground,

The knights upon each other round,

As if possessed by mortal hatred,

Their energy could not be bettered,

Wielding their swords most cruelly,

As often, and as recklessly,

As one who would his fortune make

At dice, will ever double his stake,

Whene’er he loses, and play on.

Yet this game proves a different one,

For here there’s no loss or failure,

Only blows, and sharp encounter,

Fierce and cruel under the sun.

All had issued from the mansion,

Sire and lady, sons and daughters,

None remained, friend or other,

All the household standing there,

In line, to witness that affair,

Keen to see who might yield,

On that broad and level field.

Ashamed, the Knight of the Cart,

Fearful of seeming faint of heart,

Seeing his host there looking on,

And all the crowd gazing as one,

Standing close, in line together,

Feels his heart swell with anger,

Thinking he ought, full long ago,

Surely, to have felled this foe,

Who so engages him in combat.

He launches himself fiercely at,

The other; like a tempest dread,

Striking him full upon the head,

Pushing, pressing him so fiercely

He near dislodges him completely;

From his ground he drives his foe

Till the other’s near exhausted, so

As to offer but slight defence.

Then he recalls the dire offence

His foe has committed at the start,

Shaming him concerning the cart.

So he assaults him and beats him

Till he’s broken at the neck-brim

Every leather strap and tie,

Making the other’s helmet fly

From his head, and his ventail.

Such is his foe’s pain and travail,

That he is forced to cry for mercy,

Like to the lark that cannot flee,

Nor withstand the hawk’s attack,

Since all protection it doth lack,

As its foe passes and surmounts it.

So, shamed, for his own benefit,

Must the knight at once beg for,

Mercy, since he can do no more.

When the Knight of the Cart heard

His plea, his blow he thus deferred,

And said: ‘Mercy it is you’d seek?’

‘This is no great wisdom you speak,’

Replied the other: ‘a fool could see

I never wished for aught, woe’s me,

As much as I wish for mercy now.’

Our Knight replied, ‘Then, I avow,

That you must in the cart now ride;

Naught you may say upon your side

Counts aught for me if you do not

Mount the cart; let that be your lot,

And atone for all that so vilely your

Foolish lips have reproached me for.’

‘May it please God I’ll ne’er do so,’

Replied his defeated enemy. ‘No?’

Said the knight, ‘then you shall die.’

‘Sire, you can kill me,’ came reply,

‘Yet for God’s sake, I beg of you

Mercy, and only ask that you do

Not compel me to mount the cart,

There’s naught I’ll not accept, apart

From that, howe’er painful to me;

But a hundred times I’d rather be

Slain, than suffer such disgrace;

Naught else is there I would not face,

That, of your goodness and mercy,

You might choose to inflict on me.’

Lines 2793-2978 A maiden seeks the defeated knight’s head

WHILE the knight thus sought mercy,

The Knight of the Cart did perceive

A maid in the field, nearing, who

Rode upon a mule of dusky hue;

Her clothes dishevelled, head bare,

A whip grasped in her hand there,

She struck the mule mighty blows,

And ne’er a steed at full gallop goes

Faster, in truth, than did that mule

As she rushed on towards the duel.

‘God give you joy and fill your heart,’

She cried, to the Knight of the Cart,

‘With all that doth please, sir knight!’

And he, who heard her with delight,

And gladly gave ear to all she said,

Replied: ‘God bless you, my maid,

And grant you good health and joy!’

Then she begged him for his employ:

‘Sir knight,’ she said, ‘I, from afar,

Come, in great need, where you are,

To ask of you a favour, whose

Value to me and worth to you

Is as great as ever it could be,

And you will yet, I do foresee,

Have need of me in this affair.’

And he replied: ‘Tell me, my fair,

What you wish then, and if I may

I’ll grant it you, without delay,

Unless it should prove too dear.’

And she replied: ‘Tis the head, here,

Of this knight that you do conquer.

For, truth to tell, you could never

Find a wretch so vile and faithless.

You’ll do no wrong, I may confess,

No sin, but a goodness and charity;

For the most faithless there could be

Of all wretches in this world is he.’

Now when his defeated enemy

Heard that she desired his death:

‘Believe her not! With every breath,

She breathes hatred of me,’ he said,

‘I beg that you show mercy, instead,

By that God at once Son and Father,

He who chose as His Son’s Mother

His handmaiden and His daughter!’

‘Ah, believe you not this traitor,

Good sir knight!’ now cried the maid,

‘May God grant you, all your days,

All you desire of joy and honour,

And grant you, in your endeavour,

All the success that might be won.’

And now the knight was so taken

With her words, he stood in thought

Perplexed, as to whether he ought

To grant her the head she desired,

Or if, by kindness and mercy fired,

He ought to take pity on his foe.

For regarding her, and him also,

He wishes to grant their demands;

Largesse and Pity both command

Him to do right toward these two,

For he is kind and generous too;

But if she bears the head away

Mercy and pity die that day;

And yet if she bear it not thence,

Largesse he cannot dispense.

So do both pity and largesse,

Hold him confined, and in distress,

Tormented, driven by each in turn.

The maiden for the head doth burn,

That she wishes him to grant her;

While his enemy, upon the other

Hand, seeks pity and kindness;

And since he has made request

For mercy, should not it be his?

Yes, for in such like case as this

Where he has felled an enemy,

And forced him to sue for mercy,

He’s never failed to heed that cry,

Never such mercy has he denied,

Not once has he refused it ever,

Nor e’er born a grudge thereafter.

Surely he could not now be seen,

Since such his custom it has been,

To refuse a man the like request?

And should he grant, at her behest,

The head? Why yes, if he but could.

‘Sir knight,’ he said, ‘now I would

That you should fight with me again,

And such mercy now, for your pains,

I shall indeed to you extend,

That you might your head defend,

As to grant you to arm your body,

And take your helm, and be ready.

As completely as e’er you might.

But if I conquer you, sir knight,

Once again, then you shall die.’

‘No more I seek,’ came the reply,

‘Nor other mercy do I demand.

And I will fight thee as I stand,

And give thee the advantage that

I shall not move, for this combat,

From the place where I am now.’

He clads himself and, with a bow,

They return to the fight, eagerly.

Yet our knight conquered more swiftly,

After the mercy he’d rehearsed,

Than e’er he’d done at the first.

And thus, at once, the maid did cry:

‘Spare the wretch not, now, say I,

Sir knight, whatever he may say!

If he had conquered you this day

He’d not have spared you at all.

If you believe words he lets fall,

Know he’ll beguile you once more.

Cut off the head, and so be sure,

Of the most faithless man that we

Have in this land, and grant it me!

For, grant it me you ought, indeed,

Since I shall reward so fine a deed,

Full well, when the day shall arise,

While, if he can, with his vile lies,

He will beguile thee for your pains.’

The other seeing death close again,

Begged him for mercy, long and loud.

But his pleas prove worthless now,

Whatever words he seeks to say;

By the helm he’s dragged away.

The leather straps no more avail,

The white coif, and the ventail,

From his head, away these fly;

While he doth loud, and louder, cry,

‘Mercy, for God’s sake, sire! Mercy!’

The knight replies: ‘Full wise I’ll be,

Having once granted you mercy,

No longer shall I show you pity.’

‘Ah,’ says he, ‘now ill would it be

To heed her, who’s my enemy,

And kill me in such a manner.’

While she who seeks the favour

Exhorts the Knight of the Cart

To sever his head, for her part,

And not trust a word of his lies.

He strikes, and away the head flies,

To the ground, doth the body fall;

Thus the maid is satisfied withal.

The Knight of the Cart then takes

The head by the hair, and makes

To give it to her, who of it has joy,

Who says: ‘So may your heart enjoy

Joy as great, from your every wish,

As doth my own heart here in this,

All that I most have coveted.

By naught was my sorrow fed,

But that the man was still alive.

A boon, since for me you did strive,

You shall have at the proper hour;

For you shall gain for this favour

A worthy reward, I promise you.

Now I will go, commending you

To God, may He guard you from ill.’

And so the maiden departs at will,

As they to God commend each other.

But all of those who came together

To view the fight, of that country,

Now filled with joy at his victory,

At once relieve him of his armour,

In their joy, and show all honour

To him, in every way they can.

Once again they rinse their hands,

And take their places for a meal,

Happier than they were wont to feel,

And so they eat more joyfully still.

When at length they’d had their fill,

His host said to his honoured guest,

Seated by him, not among the rest:

‘Twas long ago we came, I fear,

From the kingdom of Logres, here.

There were we born, thus we wish

That honour come to you in this

Country, and joy and fortune too,

For we would profit as much as you;

And twould profit many another

Should you gain fortune and honour,

In this your journey, and task also.’

And he replied: ‘God make it so.’

Lines 2979-3020 Approach to the Bridge of the Sword

THE host ceased speaking to his guest,

And once his voice had sunk to rest,

One of the sons followed the knight,

And said: ‘We ought to grant outright

All that we have, now, in your service,

Rather than simply yield a promise;

If you have need of us, tis clear

We should not merely linger here,

Waiting for you to ask our aid.

Thus sir, no longer be dismayed

About your horse that sadly died,

We have fine horses here to ride;

I would have you take one of ours,

Choose the best and make it yours,

Take from us aught that you need.’

The knight replied: ‘I will indeed.’

Then, their beds having been made,

They retired. And when it was day,

They rose again, early, and dressed,

Ready to leave, both sons and guest.

Upon departure they fail in naught,

But take their leave as they ought

Of master, lady, and all the others.

But I must mention that the brother’s

Gift the knight was most unwilling

To accept, and kept insisting,

He would not now mount the steed

Granted to him, though he’d agreed.

Rather he made, as I must recount,

One of the other two it to mount,

The sons who kept him company;

And upon the other’s horse did he

Mount, for it pleased him so to do.

When all were astride, the knight too,

All three upon the road did post,

Having taken leave of their host,

Who had, in every way he might,

Served and honoured them the night.

Along the road they went riding,

Until, the evening sun declining,

To the Bridge of the Sword they

Did come, at the ending of the day.

Lines 3021-3194 The crossing

AT the head of this bridge of woe,

They gazed at the water below,

All dismounting from their steeds.

Black and turgid, it raged and seethed,

As foul and dreadful, and as evil

As if twas conjured by the devil.

Then, twas so deep and perilous,

In all the world naught but must

Be lost, in falling, as certainly,

As if it had plunged into the sea.

The bridge that did that gulf breast

Differed, as well, from all the rest;

For never was there such, in sooth.

Never was there, if you seek truth,

So ill a bridge, or so evil a beam;

The bridge across that chill stream,

Was a polished and gleaming blade.

Its steel was strong and well-made,

And at least two lances in length;

And at each end, for greater strength,

A tree-trunk where the blade was set.

And none need fear a fall, as yet,

Due to its bending or shattering,

For such was that blade’s tempering

That a massive weight it might bear.

But much discomfort it gave there

To the two in our knight’s company;

And they thought that they could see

Over the stream, on the farther side,

A pair of lions, or leopards, tied

To a great rock where the bridge ended.

The stream and the bridge, thus defended,

So filled the two with terror and dread,

Both men trembled with fear and said:

‘Take counsel, fair sir, and consider

What it is that you see thither,

For you needs and must so do.

Tis badly made and fashioned too,

This bridge, the carpentry is ill.

If you repent not now at will,

You’ll be forced to repent later.

You must indeed now consider

Which course you mean to take,

If you must the crossing make,

Though that thing can never be,

No more than you the wind’s free

Flight can halt, so twill not blow,

Or may prevent the birds’ song so;

No more than if birds sang a mass,

No more than if it came to pass,

A man re-enter his mother’s womb

And be re-born, fresh life assume,

For these are things that cannot be,

No more than emptying the sea;

Do you think that those two fierce

Lions, chained there, will not pierce

You, then kill you, drink the blood

From out your veins, ere they would

Eat your flesh, and gnaw the bones.

Tis enough for me to chance, I own,

To look at them, and meet their eyes;

If you take not good care, say I,

They will devour you, for sure.

Your body they will tear and gnaw,

Inflicting upon you grievous pain.

Mercy they lack, and so will maim.

Have mercy and remain, however,

So that we might stay together!

It would be reprehensible,

To place yourself in mortal peril,

And to do so intentionally.’

The knight replied, then, laughingly:

‘Sirs, I must now give thanks to thee,

For showing such concern for me,

It comes of your loveing kindness;

I know you’d ne’er wish distress

On myself, whate’er might chance;

But I with faith and trust advance,

So God will guard me, through all;

I fear nor bridge nor stream, at all,

No more than I fear this dry land;

So ready to cross, here I stand,

And this adventure I shall try,

I’ll not turn back, I’d rather die.’

The two sons offer no reply

But from pity they weep and sigh,

Profusely, as well they might;

While, readying himself, the knight

Prepares to cross as best he may;

And does a strange thing this day,

By laying bare his hands and feet;

He shall scarce arrive complete

When he reaches the other side.

Along the sword he now did slide,

Which was sharper than a scythe.

Naked, hands and feet did writhe,

For from his feet he did dispose

Of soles and uppers, then the hose.

And yet the pain he did not dread,

Though bare feet and hands ran red,

Rather he chose to bear it all

Than from the vile bridge to fall

Into that stream, with no egress.

With no small pain and distress,

He crawled across to solid land,

Wounded in feet, knees and hands;

Yet all the suffering and pain

Love, who led him, soothed again,

And, even there, Love made all sweet.

Using his hands and knees and feet,

Thus to the far bank he did slide,

Then looked about from side to side,

Thinking to see those lions there

That the other two had declared

They had seen; he looked around;

But ne’er a lizard there was found,

Or aught else harmful in that place;

He raised his hand towards his face,

And, gazing intently at his ring,

Proved neither lions nor anything

Were present that the two had seen,

For mere enchantment it had been,

And he found nothing living there.

Those on the other side did share

Their joy that he was safe across,

Rightly, and yet more so because

They knew naught of his injuries;

Though he himself was greatly pleased

That he’d not suffered greater harm,

Despite the blood that trickled warm

From his wounds to drench his shirt.

Before him he spied a tower, girt

With stone, right strongly built I mean;

So strong a tower he ne’er had seen.

No finer a tower could one show,

And seated at a high window

Appeared the king, Bademagu,

Most scrupulous, exacting too,

As to honour and what was right,

And it was this king’s delight

To prize and practise loyalty.

His son, who, on the contrary,

As far as he might, every day,

Disloyalty loved to display,

And who of working villainy,

And treason, and all felonies,

Never tired, whate’er betide,

Stood there, at the king’s side.

They’d seen, from the tower’s height,

The painful passage of the knight

Over that bridge of woe and pain.

And Meleagant, the son, was fain

To darken with intense displeasure,

Foreseeing challenge to his seizure

Of the queen; yet he was a knight

Who dreaded no man in a fight,

However fierce or strong he seem,

Nor would there e’er have been

A finer were he not disloyal,

But he had a heart, though royal,

Of stone, devoid of love or pity.

That which made the father happy,

Was sorrow and grief to his son.

The king, indeed, knew the one

Who had crossed the bridge to be

Far greater a knight than any;

For no man would have spent

Such pains in whom ill-intent

Dwelt, that shames the evil more

Than virtue the good doth honour;

And virtue’s works seem ever less

Than those of idle wickedness,

For, beyond doubt, tis ever true,

More evil than good may we do.

Lines 3195-3318 King Bademagu and his son Meleagant disagree

MORE on this subject I could say,

If so to do caused not delay;

But to other matters I must turn,

Who to my tale shall now return.

And you shall hear how the king

Schools his son in this very thing:

‘My son,’ says he, ‘it proved good,

That we, here, at the window stood

Both you and I, and thus perceived

As reward, what must surely be

The greatest deed that e’er was wrought,

Or of which any man e’er thought,

Performed by a knight, as we saw.

Tell me now if you are not more

Well-disposed towards the man

Who fulfilled this wondrous plan.

Make peace, and release the queen!

Scant glory shall you gain, I ween,

But rather great harm shall arise,

If you fight. Show yourself wise,

And courteous, and send the queen

To him ere you yourself are seen.

Show him honour in our country,

And that which he has come to seek

Grant to him ere he makes demand;

For you know well and understand

He comes seeking Queen Guinevere.

Do not be seen as stubborn here,

Or viewed as one foolish and proud!

If, all alone, he comes here now,

Then you should keep him company,

For noble with noble should agree,

And each show the other honour,

Not be strangers to one another.

Honour to him who honour shows;

Honour will thus be yours, I know,

If you show honour and do service

To one who showed himself by this,

The best knight in the world today.’

‘God confound me,’ his son did say,

‘If as good or better is not found here!’

Ill done, that he did not hide, I fear,

That he thought himself no less a man.

He added: ‘Kneeling, with clasped hands,

You’d see me swear myself as his,

And hold my lands in his service?

God help me, I’d rather be seen

As his than surrender the queen!

God forbid that in such a manner

I should agree to her surrender!

She’ll never be rendered up by me,

But rather defended, endlessly,

Against all who foolishly dare,

In search of her, to hither fare.’

Then said the king to him again:

‘My son, were you but to refrain

From this twould be more courteous.

I pray you maintain peace among us.

You know that honour will belong

To this knight if he waxes strong

And wins her from you in battle.’

He’d rather win her so I can tell

Than through all your courtesy,

For that would increase his glory.

It seems to me he seeks her here

Not that he might to peace adhere,

But rather to regain her by force.

So twould be your wisest course,

Not to fight with him recklessly.

That you are foolish saddens me,

And, if my counsel you despise,

Twill prove worse for you than I,

And evil will come to you, I fear,

For this knight in his sojourn here

Has none to trouble him but you.

As for myself, and household too,

I’ll offer him peace and security,

I’ve ne’er acted with disloyalty,

Committed treason or felony,

Nor will for you do villainy,

Any more than for a stranger;

Nor will prefer you, but rather

I hereby promise that the knight

Shall lack for naught that he might

Need; armour, steed shall be his own,

Due to the courage he has shown

In coming to our kingdom thus.

And he shall be defended by us,

Against all other men here too,

And protected, except from you.

And I would have him understand

That, if against you he shall stand,

He need have fear of none other.’

‘I have listened, in silence, father,

Long enough,’ said Meleagant,

‘You may say whate’er you want,

But little I care for all your speech.

Tis no hermit, to whom you preach,

Filled with pity, and charitable,

Nor shall I be so honourable

As to give him what I most prize.

His object he’ll not realise

So easily, nor half so soon,

As you and he may both conceive.

We need not quarrel, I believe,

Even if you should aid him so.

If with you and your household

He makes peace, what’s that to me?

Naught in my heart fails, for, see,

I’m the more pleased, God save me,

That he need fear myself merely.

I wish you to do for me naught,

Not a thing that might be thought

To smack of disloyalty or treason.

Play as you please the virtuous one,

And leave it to me to be cruel.’

‘What? You will not yield, you mule?’

‘No,’ said he. ‘Then words shall cease.

Do your best; I leave you in peace,

And I’ll go speak to this knight.

For I’ll now offer him outright

My aid and my counsel in all;

I’ll take his side, whate’er befall.

Lines 3319-3490 King Bademagu offers the Knight of the Cart his aid

THE king descended to the court,

And had his royal charger brought.

To him was led a handsome steed,

And he mounted promptly indeed,

Taking some few for company,

A pair of squires, and knights three,

Who go with him, and none beside.

Nor did they cease from their ride

Till of the bridgehead they had sight.

Arriving there, they found the knight

Wiping his wounds free of blood;

This man, the king now understood,

Must be his guest till all was well,

Though the king felt, truth to tell,

That one might sooner drain the sea.

Then the king dismounted swiftly,

And the sorely wounded knight

At once dragged himself upright,

Though twas the king he knew not,

As if all his anguish were forgot,

All the pain in his hands and feet,

And he himself sound and complete.

The king, at the effort this incurred,

Hurried to greet him, with kind word:

‘Sir, I am occupied with wonder

At how you’ve come from yonder,

To fall upon us in this country.

Be welcome, for it seems to me,

None will attempt the like again.

That past and future, as is plain,

Saw not, nor shall see, such a deed,

Or meet such peril, I must concede.

And know that I love you the more

For doing what no man has before

Either himself conceived, or dared.

You will find me disposed to care

For you; and true and courteous.

And I, as the king here, among us,

Offer you, willingly, all there is

Of my good counsel and service;

And know, full well, my thinking

As to what you come here seeking,

For I believe you seek the queen.’

‘Yes, sire,’ he said, ‘and her I mean

To find; naught else brings me here.’

‘Friend, you’ll suffer pain, I fear,’

Said the king, ‘ere you regain her.

And I see you already suffer;

I see your wounds, and the blood.

He’ll not be generous, as I would,

He who led her here, that knight,

And surrender her without a fight.

But you must stay, so we may see

To your wounds, till you may be

Healed, and are whole completely.

The ointment of the Three Mary’s,

Or a better if such may be found,

I will give, that you may be sound,

Seeking thus your health and ease.

The queen is so imprisoned she’s

Not accessible to mortal man,

Not even my son, Meleagant,

Who led her here, and takes it ill.

Ne’er did man with rage so fill

As he, who’s sore and angry too.

But I, who look kindly upon you,

So help me God, will gladly give

Whate’er you need, as I do live.

Not even my son, who I will not

Favour in this, armour has got

As fine as that I shall give you

And the horse that you need too.

Whoever is angered, yet I will

Protect you from all others still.

And you need fear no man, I say,

Except the one who brought away

Queen Guinevere and led her here.

None’s been so berated, I fear,

As this son of mine has by me,

Well nigh driven from this country

By my displeasure, for that he

Will not surrender her to thee.

He is my son, but trouble not,

For he shall never do you a jot

Of harm, against my will, unless

In battle with you he prove best.’

‘I give you thanks, sire!’ he replied,

‘Yet time is a-wasting here, say I,

Time indeed that I would not waste.

Naught of this is to my distaste,

Nor do my wounds hinder me.

Lead me then to wherever we

May meet, for with this my armour

I will happily endeavour

To render blows and blows receive.’

‘Friend, twould be better to leave

Such matters for a fortnight or so,

To see your wounds healed or no.

Best if you stay with me, sir knight,

And for at least this next fortnight.

For I’ll not suffer it, anyway,

Nor could I witness the display,

If you were to fight before me

With the arms and gear I see.’

And he replied, ‘If it so please,

No other weapons than these

Would I willingly use to fight

This battle, nor do seek respite,

Nor adjournment, nor delay,

But would fight with these today.

Yet, in deference to you, I state

That till tomorrow I will wait,

But then whate’er any may say

I shall brook no further delay.’

And so the king replied, to this,

He should have his every wish,

And had him to his lodgings led,

And then to all his servants said

They must serve him well that day,

And they did willingly obey.

Then the king who gladly would

Have wrought a truce if he could,

Went straight away to see his son,

And, speaking to him then as one

Who wished for peace and accord,

Said: ‘Fair son, cease this discord,

Be reconciled without a fight!’

He has not come here, this knight,

To chase the deer or hunt the boar,

He comes here in search of honour,

To enhance his praise and renown,

And he is much in need, I found,

Of rest and healing; would that he

Had taken good counsel from me,

So I this battle need not expect,

Neither this month or the next,

Of which he seems so desirous.

What could prove so disastrous

About your rendering him the queen?

Fear no dishonour, that I mean,

For on you will fall no blame.

Rather tis wrong now to retain

That to which you have no right.

Most willingly would this knight

Engage in battle straight away,

Though his hands and feet, I say,

Are not whole, but cut and raw.’

‘Right foolish you are, and more,’

Said Meleagant, to his father,

‘By the faith I owe Saint Peter,

I’ll hear you not in this affair.

If I did so, torn apart, I swear,

By horses, I’d deserve to die.

If he seeks honour, so do I.

If he seeks glory, I seek mine.

And if he wishes battle, fine,

That I wish a hundred times more.’

‘Set on blind folly, as before,

Folly you’ll find,’ said the king,

‘Tomorrow you may try the thing,

Since you so please, with this knight.’

‘May no more troublesome a fight’

Said Meleagant, ‘visit me ever!

I wish it were this day rather

Than that it should be tomorrow.

See my countenance of sorrow;

I look more downcast than before.

My eyes are wilder than of yore,

And much paler seems my face.

Until I meet him, tis the case

That I’ll have neither joy nor ease,

Nor is there aught that can please.’

Lines 3491-3684 The knight is revealed as Lancelot of the Lake

THE king could see by his manner

Advice was useless, as was prayer,

And dismissed his son, reluctantly,

Chose arms and a good strong steed,

And sent them for him to enjoy

Who was worthy of their employ.

There he also sent a surgeon,

One known as a good Christian,

And none more trusted anywhere,

A doctor more skilled in such care,

Than all those of Montpellier;

And he treated the knight that day,

With all the means that were to hand,

In accord with the king’s command.

The news had gone abroad already

Among all the lords and ladies,

And the maidens and the knights,

And set the country round alight;

And all that night, until broad day,

Friends and strangers made their way

Toward the castle, hour by hour.

By morning, all about the tower,

So great a crowd had gathered, there

Was not a foot of ground to spare.

And in the morn the king arose,

The battle adding to his sorrows,

And went first thing to see his son,

Who’d but now laced his helmet on,

A helm well-made in Poitiers;

Since there could now be no delay,

Nor was there any chance of peace,

For though his efforts did not cease,

The king’s attempts lacked power.

Amid the square, before the tower,

According to the king’s command,

Where all the people now did stand,

Was the place where they would fight.

The king sent for the unknown knight,

At once, and led him to the square.

Which was tight-packed everywhere,

With folk from the realm of Logres.

For as they to the church progress

Each year, to hear the organ play,

On Pentecost, or Christmas Day,

As they’re accustomed so to do,

So all the folk had gathered too

Here, in assembly, in full array.

And for the space of three days,

All the foreign maidens there

From Arthur’s court, feet bared,

In their shifts, had fasted straight,

So that God might of his great

Grace grant strength and virtue

In the fight that must now ensue

To him who for the captives fought.

While those of Bademagu’s court

Prayed on behalf of the young lord

God would him the honours afford,

And grant to him the victory.

Ere prime did sound, full early,

Both of the knights, now were led

To the square, armed from foot to head,

On horses clad with plates of steel.

Meleagant came to the field

Handsome, graceful and alert,

With his close-knit mail shirt,

And his helmet, and his shield

That his neck and side concealed;

All these did become him well.

But as to the other, all could tell,

Even those who wished him ill,

And vowed, that Meleagant was still

Worth naught compared to this knight.

As soon as they were placed aright,

In the square, the king appeared,

Detained them, as the time neared,

Seeking peace, before everyone,

But yet could not persuade his son;

And so he said: ‘Now grasp the rein,

And you your eager steeds restrain,

Until I’ve mounted to the tower.

This small favour’s in your power,

To wait a moment more for me.’

Then he left them, sorrowfully,

And to that very place did climb,

Where he knew that he would find

The queen, who the night before

Had asked that he might afford

To her a clear view of the fight.

This he had granted her outright,

So now he went to escort her,

Concerned to show her honour,

And serve her with all courtesy.

At one window there sat she,

And at another, upon her right,

He sat to view the coming fight.

And also sitting with those two

There was many a knight too,

And prudent lady, and a band

Of maidens born in that land;

And there were many prisoners

All intent upon their prayers,

Who were captive in that country.

For our knight they prayed, freely,

And their orisons did sayeth.

In God and him they place their faith

And hopes of deliverance.

Then both the knights advance,

Forcing the folk to move aside,

Clash shields with elbows as they ride,

Gripping them with their arms fiercely,

Each strikes the other so violently

Through the shield he drives his lance;

Two arms’ length deep it doth advance.

Cracks like a branch in the fire’s heat;

While head to head the horses meet,

And clash together breast to breast;

And shield on shield, in this contest,

And helmet doth with helmet clash,

Much as doth peal the thunder crash,

Which echoes with so great a sound

It seems to shake the solid ground.

Never a breast-strap, girth or rein,

But parted sharply with the strain,

Nor surcingle; their saddle-bows,

Though strong, were broken by the blows.

Twas no great shame that these two

Both tumbled to the ground, in view

Of their sudden misadventure.

They leap to their feet, to ensure

Both can fight on once more,

Fiercer than boar against boar;

And do all threatening words forego,

To deal, with the blade, blow on blow,

Like men whom hatred doth renew.

Often they slice so fiercely through

Helmet, or gleaming coat of mail,

The blood springs forth without fail.

A fine battle they did provide,

Inflicting wounds on either side,

From heavy blows that on them rained.

Many fierce bouts they long sustained,

Struggling together mutually,

Such that the onlookers could see

No advantage to either knight.

But it was plain that in the fight

He who had crossed the bridge must be

Much hampered by his hands which he

Had wounded, in entering that land.

Much dismayed were those on hand,

Full many inclined to his side,

Seeing his blows falling wide,

Thinking he would defeated be.

Now weakening, it seemed that he

Would have the worst of the fight while

Meleagant would win in style;

And all around began to murmur.

But at the window of the tower

Sat a maid who was full wise,

And of herself she did surmise

The knight did not thus undertake

The dread encounter for her sake,

Or for these folk that stood about,

Who merely came to watch the bout,

But that his only thought had been

Simply to battle for the queen;

And she thought that if he knew

The queen sat at the window too,

So that she might the battle view,

His strength and courage would renew.

And if she had but known his name,

She would have cried out the same,

That he might look above his head;

So she came to the queen and said:

‘Lady, for God’s and for your sake

And ours, this enquiry I make,

As to the name of that brave knight,

So I may aid him in the fight.

Tell me his name, if you do know.’

‘The question that you ask doth show,

Fair maiden,’ replied the queen,

‘No hatred or ill, but it has been

Asked with good intent, I see.

His name I know, for he must be

Lancelot of the Lake, this knight.’

‘God! How my heart fills with delight,’

Exclaimed the maid, and cried aloud,

Leaning forward, above the crowd,

Such that, whether they would or not,

All heard her calling: ‘Lancelot!

Turn about now that you may see,

Who it is who takes note of thee.’

The End of Part II of Lancelot