Chrétien de Troyes

Lancelot (Or The Knight of the Cart)

Part I

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Lines 1-30 Chrétien’s Introduction.

- Lines 31-172 Sir Kay accedes to the Queen’s request.

- Lines 173-246 King Arthur grants Kay’s demand.

- Lines 247-398 The Knight of the Cart.

- Lines 399-462 The tower and the maid.

- Lines 463-538 The bed and the lance.

- Lines 539-982 The encounter at the ford.

- Lines 983-1042 The Knight of the Cart dines with a maiden.

- Lines 1043-1206 The Knight defends the maiden.

- Lines 1207-1292 The Knight resists the maiden.

- Lines 1293-1368 The Knight and the maiden ride out together.

- Lines 1369-1552 The fountain, the comb, and the tresses of hair.

- Lines 1553-1660 The Knight of the Cart champions the maiden.

- Lines 1661-1840 A father’s command avoids an immediate encounter.

Lines 1-30 Chrétien’s Introduction

SINCE my Lady of Champagne,

Would have me take my quill again,

And pen a romance, I write anew,

Willingly, as a man who’d do,

Without seeking to flatter her,

All he can in the world for her.

But if one did, in such a matter,

Wish to offer praise, and flatter,

He might say, and I’d so attest,

This lady doth exceed the rest,

Of all those who meet our eyes,

Much as the breeze that doth arise

In April and May proves best of all.

I’faith, I’ll not such speech recall;

‘This lady doth exceed the rest, Of all those who meet our eyes’

The Romance of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table (p530, 1917)

Sir Thomas Malory (15th cent), Alfred William Pollard (1859-1944), Arthur Rackham (1867-1939)

Internet Archive Book Images

Not being one to flatter his lady,

Shall I say: ‘What a gem may be

Worth, in pearls and chalcedony,

The Countess is worth in royalty?’

Nay, I shall say naught I may rue,

Though, in spite of me, it is true:

But this I’ll say, that her command

Has more to do with this at hand,

Than any effort that I’ll bestow.

Here Chrétien begins it, though,

His book of the Knight of the Cart;

Whose matter and sense, for her part,

The Countess grants, and he but tries

To set forth, in his thoughts’ guise,

Her concerns and her intention.

Lines 31-172 Sir Kay accedes to the Queen’s request

I say that once, upon Ascension,

King Arthur held a worthy court,

Rich and fine as ever was sought,

For such was fitting for the day.

After dinner he chose to stay,

Not forsaking his companions;

In the room was many a baron,

And the queen was present too,

And she had with her not a few

Of her fair and courteous ladies,

Speaking French most fluently.

Kay who’d furnished the tables,

Was eating with the constables;

And there, where Kay sat to eat,

Came a knight, armed complete,

All equipped as one who fought,

And so appeared before the court.

The knight, suddenly advancing,

Came and stood before the king,

Where Arthur sat among his lords;

All form of greeting he ignored,

Saying: ‘Arthur, in my prisons

I have knights, ladies, maidens,

Of your realm and your household;

But this thing to you I have told

Not that to you I may them render;

Rather I wish this truth to tender,

That you have not the power here

To regain those that you hold dear;

Know indeed that death shall find you

Before you can effect their rescue.’

The king replied that he must suffer

What he had not the power to cure,

But nonetheless it grieved him deeply.

Then the knight turned, much as if he

Wished to depart, tarrying no longer,

Not waiting for the king, but rather

Seeking out the door of the hall;

And yet, before he left them all,

Halting upon the stair, said he:

‘King, if at your court there be

A knight in whom you have such trust

That the queen you’d dare entrust

To him, to lead her, after me,

Into the woods where I journey,

I promise to await him there,

And give the prisoners into his care,

Whom I hold exiled in my land,

Should he defeat me, you understand,

And bring her safely back to you.’

Many in the palace heard him too,

And the court was in commotion.

Kay listened to him, with emotion,

Where he sat with the constables.

He leaped to his feet, left the table

And went straight before the king,

As if he was in anger speaking:

‘King, I have served you long indeed

Faithfully, and yet now I plead

To take my leave, and issue forth,

For I shall never serve you more.

I’ve no wish to attend upon

Or serve you from this moment on.’

The king was grieved by what he heard,

And, once he could summon a word,

His astonishment he expressed:

‘Kay, speak you in earnest, or in jest?’

And Kay replied: ‘Fair sire, indeed

For jesting I’ve nor taste nor need,

I request your leave most earnestly;

No other wages do I seek

Nor reward for all my service;

I have decided, my wish it is

That I depart without delay.’

‘Is it through anger or spite, pray,’

Said the king: ‘that you wish to go?

Seneschal, stay at court, and know,

As tis your wont to be here, so I

Possess naught in this world that I

Would not grant you most willingly

Should you consent to stay with me.’

‘Sire,’ said Kay, ‘that will not serve;

I’d not accept, to stay and serve,

An ounce of the purest gold a day.’

Thereon, the king, in great dismay,

Hurried away, the queen to see.

‘Lady, you’ll not believe,’ said he,

What the Seneschal doth request;

He would leave the court, I attest,

Though for what reason I know not.

Yet he will do for you, God wot,

That which he will not do for me;

So go to him now, my dear lady!

Though to stay for me he’ll not deign,

Beg him for your sake to remain.

Fall at his feet, if such needs be,

For if I should lose his company

I’d never again know happiness.’

The king sends the queen, no less,

To the Seneschal; she doth light

On him among the other knights;

And, when before him, she doth say:

‘I encounter great sorrow, Kay,

Surely, if this sad news be true,

That which I hear, but now, of you.

It grieves me, this, that I am hearing,

That you would wish to leave the king;

How so? And for what purpose?

I cannot think you as courteous,

Or as wise, as has been your wont;

That you should stay is what I want,

So Kay, remain, I beg of you.’

‘Lady,’ says he, ‘my thanks to you,

But nonetheless I cannot stay.’

The queen again makes her assay,

And with her all the knights, en masse,

While Kay says he wearies, alas,

Of such unprofitable service.

The queen, at this reply of his,

Falls prostrate, at my Lord Kay’s feet,

Kay now begs her to rise, but she

Says she will ne’er do so, unless

He chooses to grant her request,

And do her bidding willingly.

Kay then promises, faithfully,

If the king grants him a boon then he,

Will stay, and she must grant the same.

‘Kay,’ she said, ‘if you will remain

We’ll grant the boon, whate’er it is;

Come now, and tell him that on this,

Your sole condition, you will stay.’

So, away with the queen went Kay

And they both came before the king.

‘I’ve prevented Kay from leaving,

Though not easily, Sire,’ said she,

‘On the understanding that what he

Requests of you, you will so grant.’

The king sighed with pleasure, and

Said that whate’er he might demand,

He would obey Sir Kay’s command.

Lines 173-246 King Arthur grants Kay’s demand

‘SIRE,’ said Kay, ‘hear now what I

Desire, and the favour, in reply,

That you yourself have promised me;

Fortunate am I that you agree

To grant this boon, of your mercy.

Sire, my lady whom here you see,

You must entrust to me outright,

That we may follow the knight

Who in the forest now awaits us.’

The king is grieved, and yet he does,

For he’s a man of his word, alway.

Though he cannot but display

In his face, his deep displeasure.

The queen too grieves, in full measure,

And all say what Kay has sought,

Out of pride and madness wrought,

Is an outrageous boon to grant.

But the king now, by the hand,

Takes the queen and says to her:

‘My lady, now, without demur,

You must Sir Kay accompany.’

And Kay says: ‘Trust her to me,

And have no fear, Sire, of aught,

For I will return her, as I ought,

To you, safe and sound, and happy.’

So the king does, so they both leave,

And all there would seek to follow,

For not one there is free of sorrow.

You should know, the Seneschal

Fully armed, for his mount did call,

Which into the courtyard, was led

Together with a palfrey, one bred

For the queen’s use, exclusively.

The queen approached the palfrey,

One neither restive nor obstinate;

Then grieving, sighing at her fate,

She mounted, and close to tears,

Said to herself, so none could hear:

‘Alas, if you but reflected now,

I am sure you would ne’er allow

One pace, unchallenged, I be led!’

She thought none knew what she’d said,

But Count Guinable had heard her,

Who as she mounted stood beside her.

Among them all such tears started,

Men and women, as they departed,

Twas as if she lay dead on her bier,

For they did not hope to see her

Ever again, while they still lived.

The Seneschal, tis to be believed,

Led her to where the knight waited.

But to none came the belated

Thought to follow them instead,

Until my Lord Gawain now said,

To the king, his uncle, speaking:

‘Sire, you have done a foolish thing,

A thing at which I marvel greatly,

But, if you’ll take counsel of me,

While they are both, as yet, nearby

We shall ride after them, you and I,

And any others who may so wish.

Since I, regarding my part in this,

Will pursue them, straight away,

As it would not be right, I say,

Not to follow, at least until

We can from it all the truth distil,

As to what has become of the queen,

Or news of Kay’s intentions glean.’

‘Ah, fair nephew,’ the king replied,

‘Your courtesy ne’er will be denied.

And since you manage this affair

Order our mounts to be prepared,

Bridled and saddled so that we

Have naught to do, but ride speedily.’

Lines 247-398 The Knight of the Cart

THEIR horses were quickly brought,

Apparelled and saddled, to the court.

First, the king mounted amain;

And after him my Lord Gawain,

Then all the others rapidly.

Each man of that company

Then departed as he pleased.

Some of them their weapons seized,

My Lord Gawain was one of these,

While others went weapon-free;

Gawain made his two squires lead

Two extra mounts, in case of need;

As they thus approached the forest

They saw Kay’s horse make egress;

All there recognised his charger,

And the reins, they saw further,

From the bridle, had been torn.

The horse seemed quite forlorn,

The stirrup straps were blood-stained,

And, though the saddle-bow remained,

The saddle was all broken behind

All there were now troubled in mind,

Nudged each other and shook their heads.

My Lord Gawain had ridden ahead,

Far in front, half a league or more,

And thus it was not long before

He saw a knight approaching slowly

On a horse panting and weary,

Sore, and covered with sweat.

The knight was first, as they met,

To offer a greeting to Gawain,

Which he then returned again.

Then the knight recognising

My Lord Gawain, and halting,

Said: ‘Sire, you no doubt see

My mount is tired and weary,

Such that he is no use to me?

And those two horses that I see,

Are surely yours, so I ask of you,

Pledging that I shall return you

Both the service and the favour,

The gift or loan of whichever

You might choose to grant to me.’

Then choose whichever that you see,’

Replied Gawain, ‘best pleases you.’

Of which was the finer of the two

The knight, though, took little heed,

Nor the taller, being in great need,

But swiftly leapt onto the nearer,

Rather than seeking for the fairer,

And rode away, through the forest.

The mount he’d left, deprived of rest,

And ridden till foundered, fell dead,

Misused and wearied, as I have said.

The knight then, without taking rest,

Now spurred away through the forest,

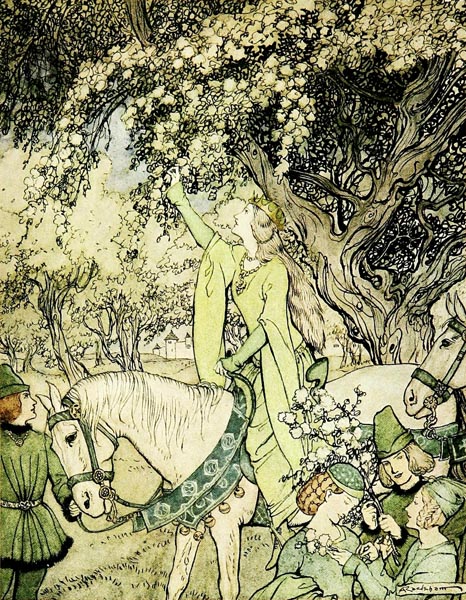

‘The knight then, without taking rest, Now spurred away through the forest’

St. Nicholas [serial] (p695, 1873)

Mary Mapes Dodge (1830-1905)

Internet Archive Book Images

With my Lord Gawain racing after,

Chasing and following with fervour,

Until he reached the foot of a hill.

On riding a distance further still,

He found the mount, dead outright,

Which he had gifted to the knight.

Horses had trampled the ground

And there was a scatter he found

Of shields and lances lying there.

It seemed there’d been a fierce affair

Involving several armed knights.

He, seeing he had missed the fight,

Was grieved not to have been there.

However he did not linger where

The fight had been, but went on,

Until by chance he came upon

The knight, on foot, and in haste,

All armed and with his helmet laced,

Shield at his neck, and sword girt,

Overtaking a cart, with a spurt.

(A pillory is now reserved

For the purpose a cart then served.

And where a thousand now are found

In every fine substantial town,

In those days there was only one,

And this cart was used in common

As the pillory is in our day

For those who murder and betray,

And those who commit perjury,

And those who steal property,

Thieves who snatch things from others,

Or are blatant highway robbers.

Those convicted of some crime,

Were set in the cart for a time,

And dragged through every street;

Their loss of rights was complete,

Nor in any court were they heard,

Nor welcome nor honoured there.

Since the cart was, at that day,

Regarded with such great dismay,

There was a saying: ‘If you see

A cart, if such encounters thee,

Cross yourself, and loudly call

On God, lest evil doth befall.’)

The knight then, without a lance,

Upon the cart doth now advance

And sees a dwarf seated aloft,

Who holds, as any carter doth,

A long goad in his two hands.

And of the dwarf the knight demands

‘Dwarf, by God, now tell to me,

If you have seen the king’s lady,

Go riding past you, recently.’

The wretched dwarf of low degree

Gave him not a word of news,

But said: ‘If you would climb up too

Onto this cart I’m riding here,

Tomorrow you will surely hear

What has become of the queen.’

Then continued the way he’d been

Going, and gave him no more heed.

The knight took but two steps indeed,

Before he swiftly climbed aboard;

Yet ill for him, who so abhorred

The shame, that he did not so do

At once, for that he’d later rue!

Yet Reason, that’s divorced from Love,

Warned him from making such a move,

Counselling him thus to refrain,

Telling him all things to disdain

That presage reproach and shame.

Reason then must share the blame,

Reaching the lips, but not the heart.

So Reason counselled, for its part;

Yet Love, enclosed within the heart,

Urged him to mount aboard the cart.

That he did, since Love wished it so,

Careless of what shame might follow,

Since it was Love’s wish and command.

My Lord Gawain, now close at hand,

Spurred on and overtook the pair,

While at the knight now seated there

Wondering greatly, and said loudly

To the dwarf: ‘Can thou tell me,

Aught of the queen, if you know?’

He said: ‘If you hate yourself so,

Like this knight who sits by me,

Then climb aboard, if you please,

And I will carry you both along.’

When Lord Gawain heard his song,

He thought the thing a great folly,

And said he did not, nor would he,

It being shameful, for a start

To exchange a horse for a cart.

‘But you go onwards, as you will,

And I will follow after still.’

Lines 399-462 The tower and the maid

SO onward they went journeying,

Two on the cart, and one riding,

Trundling along, all together,

Till they reached a castle at vespers;

And a fine castle, you must know,

With beauty and riches, all aglow.

And all three entered by the gate.

Its people wondered at the fate

Of the knight upon the cart,

Showing contempt, on their part,

Taunting him, both high and low,

The little children, the very old,

Shouting aloud along the street;

Thus the strange knight they greet,

With base villainy and scorn.

‘To what punishment is borne

This knight?’ they all enquire:

‘Is he to be scorched with fire,

Hanged, drowned, or grace a heap

Of thorns? Tell us, oh dwarf, who keep

The cart, in what crime was he caught?

Is he accused of stealing aught?

Is he a thief or a murderer?’

Not a word did the dwarf utter,

Neither looking to left or right.

To lodgings he led the knight,

Closely followed by Gawain,

Off to a tower, standing plain

Above the town which lay below,

While beyond stretched a meadow;

The tower high on a rock, sheer,

Close by the town, did thus appear.

Into the tower Gawain now went,

And there in the hall an elegant

And charming maiden he did see,

The fairest maid in that country;

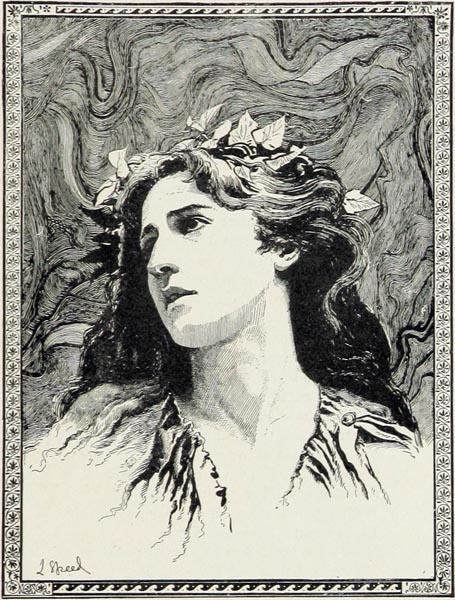

‘The fairest maid in that country’

The Blue Poetry Book (p173, 1891)

Andrew Lang (1844-1912), H. J. Ford (1860–1941) and Lancelot Speed (1860–1931)

Internet Archive Book Images

And two girls accompanying her,

Both noble and beautiful they were.

As soon as they saw my Lord Gawain

They greeted him, and they made plain

Their joy on welcoming him there;

Then asked, of the other knight aware:

‘Dwarf, for what is this knight to blame,

That he is borne like one who’s lame?’

The dwarf showed no desire to answer,

But made the knight descend the faster,

And then he and the cart withdrew;

Where he was going to none knew.

Then dismounted my Lord Gawain,

And valets then disarmed the same,

Relieving both knights of their armour.

Two green mantles the maiden ordered

To be brought, which they assumed.

When the hour for supper loomed,

A fine meal was swiftly served,

And a place was there reserved

For the maiden, beside Gawain,

Nor were the two knights fain

To change their lodging for another,

For she showed them great honour

And fine and pleasant company,

All that evening long, was she.

Lines 463-538 The bed and the lance

WHEN they’d supped long enough there,

Two beds, long and high, were prepared,

In the midst of the tower hall;

And another, the fairest of all,

Was also prepared by their side;

And it, as the tales testify,

Possessed every fine quality

That in a bed could ever be.

And when the time came for rest,

The maiden led away her guests,

With a show of hospitality,

To those beds, long and wide, and she

Said to them: ‘Both those beds there

To ease your bodies were prepared,

But in that further bed, say I,

Only the worthiest may lie.

It was not set there for your use.’

The knight who’d suffered the abuse

Of the cart, at once, gave answer,

Disdaining this warning from her,

And speaking to the maiden said:

‘Tell me the reason why that bed

Should be forbidden, as you say.’

The maid answered, straight away,

Though she knew the reason well:

‘Such things to you I may not tell

Who have no right to so enquire!

For every knight is shamed entire,

Who has been carried in that cart;

Nor is it meet that I should part

With an answer to such requests,

Nor he indeed be that bed’s guest,

A thing for which he’d surely pay.

It was not made for you this day,

So richly, and so carefully.

You would indeed pay, and dearly

For ever harbouring such a thought.’

‘You will soon see,’ was his retort,

‘I shall see?’ ‘Yes, now, and truly;

I know not who will pay,’ said he,

‘But upon my life, whoever may be

Troubled by it, or it may grieve,

I would lie down there on that bed,

And at my leisure so rest my head.’

Then he disrobed, and there did lie,

On the bed which was long and high,

Two feet higher than the other two,

Clothed with silk of yellow hue,

And a coverlet starred with gold.

The furs were neither vair nor old,

But were fresh and were of sable;

Fit for a king in some rare fable

Were the covers that graced him,

Nor was the mattress under him

Woven of rushes, nor of straw.

Yet, of a sudden, midnight saw

A lance descend from high above

As if its steel tip, falling, would

Pierce the knight through the side,

Coverlet, and white sheets beside,

And pin him there, where he lay.

And the lance a pennant displayed

Which was fair wreathed in flame,

And setting light to all that same,

Fired the coverlet and the sheets,

And the bed itself, all complete.

And the lance-tip passed so close

That it pierced the skin almost,

But without forming a deep wound.

Then the knight woke, as yet still sound,

Quenched the fire, and seized the lance,

And into the room did it advance,

Hurled it away, but kept his bed,

And once more laid down his head,

And slept as soundly, now secure,

As he’d lain down to rest before.

Lines 539-982 The encounter at the ford

THE next morning, at break of day,

The maid of the tower, straight away,

Had the Mass said for her guests,

And bade them both rise and dress.

When for them Mass had been said,

The knight who’d in the cart been led,

Sat pensively beside a window

That looked out over the meadow,

And gazed upon the fields below.

The maid came to another window,

And there she held conversation

With my Lord Gawain stationed

There, awhile, though upon what

Subject they spoke I know not,

For I know naught of their intent;

But, while upon the sill they leant,

Through the fields, along the river,

They saw men carrying a bier,

And on the bier there lay a knight

And three maids kept it in sight,

Making a deep show of mourning.

They saw, too, a host approaching,

Behind the bier, and before it came

A tall knight. By her horses’ rein,

On his left, he led a fair lady.

The knight at the window did see

And recognise she was the queen;

And, as long as she could be seen,

With close attentiveness, the knight,

Continued to gaze, in deep delight.

And when he could see her no more,

He was determined as never before

To throw himself from that height,

And he would have done so quite

Had not Lord Gawain realised

His purpose, and dragged him aside,

Saying: ‘I beg you, sir, desist!

For God’s sake think no more of this,

Commit you not so mad a deed!

Tis wrong to despise life, indeed.’

But: ‘He is right!’ the maiden cried,

‘For news will travel far and wide

Of his disgrace, and it be known

How in the cart his shame was shown,

Rather he’d wish then to be dead,

Better die thus than live instead.

Life henceforth must him distress,

Filled with shame and unhappiness.’

But the knights asked for their armour,

Arming themselves, then and there,

And the maid showed them courtesy,

Regard and generosity,

For though she had mocked the knight,

And scorned him, as well she might,

She yet gave him a horse and lance,

From goodwill and kindness perchance.

Thus, politely and courteously,

The two knights took their leave,

Of the lady, saluting her,

Then, taking the path away from her,

Followed the way the host went,

Issuing forth from the castle, bent

On pursuit, and speaking to none.

Swiftly, the way the queen had gone,

They took their path, but could not make

Sufficient speed to overtake

The host that, passing quickly on,

From fields into a glade were gone;

But there they found a beaten road,

And onward through the wood they rode,

Until it might be nearly prime,

And at a crossroads, at that time,

They met a maiden there whom they

Saluted, and did ask and pray

To tell them, if indeed she knew

And might thus inform them too,

Which way the queen had been led.

She looked knowingly, and said:

‘If you both pledge your word to me,

I could set you, and right swiftly,

On the true road, and so declare,

To you both, what land lies there,

And what knight it is that leads her;

But who would that same land enter

He must endure great suffering,

Before he can achieve the thing!’

Then my Lord Gawain replied:

‘So help me God, fair maid, so I

Promise to you, regarding this,

That I will offer, in your service,

All my strength, as you please,

If you will tell the truth to me.’

After which, the Knight of the Cart,

Not merely promising, on his part,

All his strength, also proclaimed,

As might a man by Love sustained,

Empowered, and ready for aught,

That he would promise her aught

She wished, at once, without delay,

And in her service was that day.

‘Then I will tell you all,’ said she,

And the maid told them this story:

‘I’faith, my lords, one Meleagant,

A knight as hard as adamant,

Son of the King of Gorre, has her,

And to that realm he has led her

From which no stranger doth return,

But in that country must sojourn

In exile and in servitude.’

So her tale they then pursued,

Asking: Maid, where is this land?

Where then, may we understand,

Lies this place?’ And she replied:

‘You shall know; yet first, say I,

Many a danger you must pass,

For to find entrance there at last

Is hard, except its king allow;

Bademagu’s his name I trow.

One can enter, nevertheless,

By two paths, both perilous,

By two ways, and both appal;

One, the Sunken Bridge they call,

Because below the water it lies;

Above it doth the water rise

To the same measure as below,

As deep here as there doth flow,

Such that the bridge lies between,

But a foot and a half wide, I ween,

And the same thickness it shows.

Better to choose it not, although

It is the less perilous of the two,

Yet it brings further dangers too,

Of which I shall say naught here.

The other bridge is more to fear,

Where such great peril must be met,

That none has ever crossed it yet;

For it is like a sharpened blade,

And so its name is as tis made;

The Bridge of the Sword tis called:

And now I have told you all

The truth I can say, and know.’

But then they asked of her also:

‘Fair maiden, would you now deign

To show us both the bridges plain?’

To which the maiden now replied:

‘The direct way lies on this side

To the Sunken Bridge, while there

To the Bridge of the Sword you’d fare.’

Then the knight, he who had been

Borne on the cart, intervened:

‘Sir,’ he said, ‘without prejudice,

I will grant you the choice in this,

Take whichever path you prefer

And leave the other to my care.’

‘By my faith,’ said my Lord Gawain,

‘Both now threaten peril and pain,

Both the one and the other passage;

Which the most ill doth presage,

I know not, nor which is best,

But tis not right that I protest

When you have given me to choose.

The Sunken Bridge I’ll not refuse.’

‘Without more ado then, it is right,

The Bridge of the Sword,’ said the knight,

‘I should take, and shall, willingly.’

Thereupon they parted, all three,

Commending each other courteously

To God, while the maid said, said she,

Watching them leave: ‘Remember me,

For each owes me a favour, and so be

Sure not to forget, when I do send.’

‘Truly, we shall not, my sweet friend,’

Called out both the knights as one;

Then each took his path and was gone.

And he of the cart is lost in thought,

Like a man who cannot in aught

Defend himself gainst Love that binds;

And his thoughts are of such a kind

He forgets himself, like one instead

Who knows not if he’s alive or dead,

Who cannot remember his own name,

Nor whether he is armed, the same,

Nor where he comes from nor goes.

For nothing do his thoughts enclose

Except one person, and she he finds

Has driven all others from his mind.

And he thinks of her so incessantly

Naught else doth he now hear or see.

And his mount bears him, at speed,

Not by some wandering path indeed

But by the best and straightest way,

Carrying him onwards all the day

Till a wide, open land, they gain.

Now, there was a ford in that plain,

And on the far side loomed in sight,

Guarding the ford, an armed knight,

And a maid was in his company,

Who’d ridden there on her palfrey.

Mid-afternoon the day did see,

But the Knight of the Cart still he

Tirelessly pursued his thought,

While his thirsty mount of naught

But the fine clear stream did think;

And reaching it hastened to drink.

Then he who kept the other side:

‘This ford I guard, knight!’ he cried,

‘In case you may desire to cross.’

But in his thoughts the other lost

Neither heard him nor gave heed;

While in the meantime his steed

Had moved swiftly to the water.

The knight called to him further,

That he’d be wise to keep away,

For he’d not pass there that day;

And swore by the heart in his side

That he’d attack him if he tried.

But the other heard not his shout,

So for a third time he called out:

‘Knight, do not, against my will,

Enter the ford, I’ll deny you still.

Upon my life, ill shall you fare

If I should see you enter there.’

But the other still heard him not;

While, eagerly, his horse had got

Into the water, at a single leap,

Quenching its thirst, and drinking deep.

The knight declared that he must pay;

Nor would he gain in any way

From the shield and hauberk on his back;

His horse he spurred to the attack,

Urging a gallop from the steed,

And struck his enemy hard indeed,

So that our knight was upended

Amidst the ford, so well defended;

From his hand the lance now flew,

And the shield from his neck too.

Shocked, as he the water did greet,

Though stunned, he leapt to his feet,

Like a man aroused from slumber,

Listening, gazing about in wonder,

To see who might have dealt the blow.

Then facing the other knight, his foe,

He cried: ‘Vassal, now tell me why

You have attacked me, speak no lie,

For you were unbeknown to me,

And I have done you no injury.’

‘I’faith,’ he answered, ‘you wronged me,

Did you not treat me disdainfully

When I thrice forbade you the ford,

For my calls to you were ignored

Though I spoke loud as I might?

You heard me challenge you, sir knight,

Two of those three times, or more,

Yet in spite of that, entered the ford,

Though I told you that ill you’d fare

If I saw you in the water there.’

The Knight of the Cart then replied:

‘Damned if I heard you, if you cried;

Whoever else might, I heard naught!

It may well be I was deep in thought

When you denied the ford to me;

I’ll do you ill and presently

If one of my hands I can lay

On your horse’s bridle today.’

And the other answered: ‘What of that?

You may grasp my bridle pat

If you dare, and I so allow.

A handful of ashes I do vow

Is the worth of your threats to me.’

And he replied: ‘Then we agree,

For I would lay my hands on you,

Whatever outcome might ensue.’

Then, as the knight, leaving shore,

Rode to the middle of the ford,

He seized, in his left, the bridle tight

And grasped the knight’s leg with his right,

And pulled and dragged and squeezed

So roughly that the knight, displeased,

Thought that such force would surely

Tear his leg straight from his body;

And begged that he might be let go,

Calling out: ‘Should it please you so,

With me, on equal terms to fight,

Then take your horse, and shield, sir knight,

And grasp your lance, and joust with me.’

The Knight of the Cart replied, briefly:

‘I’faith, I’ll not, for I think you’ll flee,

As soon as ever I set you free.’

The knight, on hearing, felt great shame,

And said: ‘Sir knight, now mount again,

With confidence, upon your horse,

For you shall have my oath, of course,

That I will neither flinch nor flee,

For the shame of it would trouble me.’

The Knight of the Cart replied once more:

‘You must swear me that oath before,

And give your word most faithfully

That you will neither flinch nor flee,

Nor shall you launch any attack

Till you see me on my steed’s back,

Nor shall you hover too near to me,

For I’ll be treating you generously

If in my hands I yet let thee go.’

The knight could do naught but so,

And when he had heard him swear,

He seized his shield and lance there

Which were floating in the stream,

And, by this time, it would seem

Had drifted some distance away;

Then turned to mount, without delay.

Once astride, he seized his shield

And by the straps he did it wield,

And couched his lance in its rest.

Then each knight the other did test,

Spurring his mount to full speed,

Though he who kept the ford indeed

Was the first to strike his enemy

And attacked his man so fiercely

That his lance was splintered quite;

Yet engaged by the latter knight,

And thrown prostrate in the ford

Twas over him the water poured.

Then the Knight of the Cart withdrew

Dismounting, thinking he could hew

And drive a hundred such away.

If his sword he brought in play,

The other leapt up and also drew

His gleaming blade, fine and new.

There they clashed, hand to hand,

Shield before, each made his stand,

On which the gold glittered bright,

Wielding their swords with might,

Never resting, warring ceaselessly.

They landed many a blow, bravely,

And for so long the fight sustained,

The Knight of the Cart felt ashamed,

In his heart’s depth, at how badly

He’d fared on a path chosen freely,

If having elected to go this way

He’d yet encountered such delay

In conquering a single knight.

For if a hundred such he might

Have met with the previous day

They must surely have given way;

Yet now he was angered and grieved,

To be so weary, since he perceived

His blows fell short, the day waned;

Thus he ran at the other, and so gained

Upon him that the other knight fled;

Leaving, reluctantly, in his stead,

The ford unguarded, its passage free.

But the Knight of the Cart eagerly

Chased the man till he fell to his knees,

And then he swore by all he could see

That the man should rue that day

When he’d upset him on his way

And had so disturbed his reverie.

She, of the knight’s company,

The maid who’d ridden at his side,

Heard this threat and more beside;

Filled with fear, she begged that he

For her sake, would grant him mercy.

But he replied he could not do so,

No drop of mercy could he show,

Since he had suffered such shame.

Then, with drawn sword, once again

He neared the knight, who, in dismay,

Cried: ‘For mine and for God’s sake,

Grant me the mercy I ask of you.’

And he replied: ‘God’s love, tis true

No man shall e’er sin against me

To whom I would not show mercy,

For God’s sake, if on God he call,

One time at least, if it so befall.

Now therefore I must grant it, too

Since I ought not to deny it you,

When you’ve asked it thus of me;

But give me your word faithfully

To be my prisoner whenever I

Shall summon you to me, thereby.’

This he did, though reluctantly.

The maiden then said, right swiftly:

‘Since, of your goodness, sir knight,

You have granted, as if of right,

Mercy to him, as he begged you,

Then if you free all prisoners too,

Release this prisoner to me.

At my request now, set him free,

On condition that, come the day,

I’ll do all I can to repay

You in any way you please.’

The Knight of the Cart then agreed,

Accepting all she promised there,

And freed the knight into her care;

Though she was yet in some bother,

Lest he might now recognise her,

Which was a thing she wished not;

But he departed, and lingered not.

So to God they commended him,

And thus they took their leave of him.

He granted it, and went his way,

Until ere vespers, late in the day,

He saw a maiden approaching

Who was both fair and charming,

Well-attired, most richly dressed.

The maiden greeted him, I attest,

Both prudently and courteously.

‘Health and happiness, fair lady,

May God grant you!’ he replied.’

‘My house, sire,’ next, she cried,

‘Is all prepared to welcome you,

If you’ll accept my gift to you

And welcome such hospitality;

You may stay, if you lie with me,

Such is my offer, and my intent.’

Not a few would have been content,

To thank her then five hundred fold,

But he towards the maid proved cold

For now he responded otherwise.

‘Maiden, I thank you,’ he replied,

‘For the lodging, and hold it dear,

But to lie there with you, I fear,

Though it please, I shall not do.

‘That or nothing, I offer you,’

She answered, ‘by my two eyes.’

Then, unwilling to act otherwise,

He consented to what she wished,

Though his heart rebelled at this;

Reluctance now, yet unhappiness

He’ll know later and great distress,

And she’ll have much travail and pain,

The maid, who to lead him on is fain,

For she may find she loves him so

That she’s unwilling to let him go.

Now as soon as he’d granted her

All she wished at her good pleasure,

She led him on to a strong bailey,

None fairer from there to Thessaly,

Which was enclosed all around

By a high wall and a moat profound;

And there was not another there

Except the knight, now in her care.

Lines 983-1042 The Knight of the Cart dines with a maiden

HERE had been set for her delight

Many a handsome room and bright,

With a great hall, spacious and fair.

Thus, riding along the river there,

They came to the maiden’s tower,

Where the drawbridge was lowered,

To allow passage to them both.

So over they ride, nothing loath.

Here the great hall they discover

That is all roofed with tiles over.

They passed through the open door,

And there a table they saw before

Them, covered with a broad white

Cloth, all the dishes laid aright,

And about the table their eyes met

Tall candlesticks with candles set,

And there were cups of silver-gilt,

And two jugs of wine, one filled

With red, and the other with white.

Beside, on a bench-end, the knight

Espied two basins of warm water,

To wash their hands, on the other

End, a towel, finely worked, clean

And white, to wipe their hands, was seen.

Not one valet, servant or squire

Did he see, to work their desire;

And so, himself, the knight did take

The shield from his neck, and make

It all secure, by hanging it there,

On a hook, set true and square;

And then he placed his lance also

On a rack, with the shield below.

Then he dismounted from his steed

And went to help the maid but she

Had herself dismounted, with ease;

At which the knight was pleased,

That she cared not that he attend

On her, or help her to descend.

As soon as she touched the ground,

Without delay, she ran and found

A cloak of scarlet from her room,

And brought it to the knight whom

She then attired in the mantle.

The great hall was lit with candles

Though the stars above shone bright;

Tall twisted tapers shed their light.

Thus burning there, they lit the hall,

Clearly illuminating all.

About his neck she threw the cloak,

Then to him the maiden spoke:

‘Friend,’ she said, ‘here is water

And a towel, with none to offer

Either but she whom you now see;

Wash your hands, and dine with me;

Here’s food and drink for your pleasure,

So be seated at your leisure,

The hour demands it, as you see.’

He washed his hands, and willingly

Took his place, and there did bide

While she was seated at his side;

Then they ate and drank together

Until they rose, the meal over.

Lines 1043-1206 The Knight defends the maiden

WHEN they’d taken their last bite,

Said the maiden to the knight:

‘Sir, feel free to roam outside;

No hurt to you is thus implied.

Remain alone there, if you will,

And wait there by yourself, until

You think that I must be abed.

Be you not troubled, as I said,

For you may then come to me,

If you would do as we agreed.’

‘I’ll keep my word,’ replied the knight,

‘And I shall, when the time is right,

Return, as you have asked me to.’

Then he retired, to admire the view

Outside, and waited in the court,

Until the time arrived, he thought,

To keep the promise he had made,

But found no trace of the maid

In the hall, on returning there;

No sign of his ‘friend’ anywhere.

Finding the maid nowhere in sight:

‘Where’er she is,’ declared the knight,

I shall seek her till I may find her.’

And straight he set out to discover

Her, bound as he was by his word.

Now, entering a room, he heard

A maiden uttering loud cries,

And hearing them he realised

Twas she with whom he must lie.

Then an open door he did spy

To a second room, and in full view,

Before his eyes, a knight there, who

Had overcome her, she half-naked

‘In full view Before his eyes, a knight there, who Had overcome her’

The Romance of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table (p214, 1917)

Sir Thomas Malory (15th cent), Alfred William Pollard (1859-1944), Arthur Rackham (1867-1939)

Internet Archive Book Images

And held there helpless on the bed.

Then, trusting he came to her aid,

‘Grant me succour!’ cried the maid,

‘Sir knight, who are now my guest,

If you should not this creature best

None other is there so to do;

He’ll do me wrong in sight of you,

If you do not now rescue me;

For you it is must lie with me,

As you indeed have sworn to do.

Shall he before you, in plain view,

Impose his will on me by force?

Gentle knight, my sole recourse,

Grant me then succour, instantly!’

Our knight saw that most cruelly

The other held the maiden there,

For to the waist was she laid bare.

And he was angered and ashamed,

To see her naked to naked claimed,

Although he felt no jealousy;

If any was cuckold, twas not he.

Now at the doorway, armed aright,

Stood as guards, two tall knights,

And each man held a naked blade,

And behind them were displayed

Four men-at-arms each with an axe,

With which you might hew the back

Of a cow’s carcase, cut it to suit,

As easily as you’d slice the root

Of a clump of broom or juniper.

He halted at the doorway there

And said: ‘God, what am I to do?

Though committed elsewhere too,

In quest of the queen, Guinevere,

Yet to show the heart of a hare,

Does not befit me on such a quest.

If Cowardice doth my heart arrest,

And I should follow its command

I’ll ne’er achieve what I’ve on hand.

Shame is mine if I here remain;

I feel for myself sheer disdain.

At even considering holding back,

My heart grows sad, my mind black;

I am so shamed and sore distressed,

I would gladly die, thus oppressed,

For having lingered here so long.

Not out of pride, for that were wrong,

Do I ask that God show me mercy,

For wishing to die here honourably

Rather than live a life of shame.

If this passage were free, this same,

What honour would I gain? Alas,

If they but gave me leave to pass

Without challenge, then indeed

The greatest coward, I concede,

That ever lived, would pass by.

And all the while I hear her cry

Calling for help continually;

Of my promise reminding me,

Heaping upon me dire reproach.’

So the doorway he did approach,

Thrusting in his head and shoulder.

Glancing upwards, entering further,

He saw two swords descend outright;

He drew backwards, but the knights

Could not check their blows’ course.

They’d wielded their swords with force,

Such that both blades were the more

Damaged now as they struck the floor.

Seeing the blades break he was then

Less concerned by the four axe-men,

Fearing and dreading them no more;

For now he rushed towards all four,

Striking a guard and then another

In the side, and jostling those nearer

With his shoulder and arm such that

Toppling both he knocked them flat;

Then the third guard missed his aim,

As the fourth, attempting the same

Stroke, struck him and his mantle tore,

Cut his shirt, the white flesh scored,

So that from his shoulder he found

A stream of blood flowed to the ground.

Yet he still fought without restraint,

Of his wound making no complaint,

Pressing again more vigorously now,

Till he struck right upon the brow

Of him who was forcing his hostess.

He wished that now in her distress

He might fulfil his promise to her.

He dragged the man upright further,

Whether he would or no; but he

Whose aim had failed, suddenly

Came at him, to repeat his blow,

Hoping with his axe-blade so

To strike him as to split his head;

Yet he, defending himself instead,

Thrust the first foe at the other,

So that the axe, in its encounter,

Where the neck and shoulder meet

Cleft the one from the other complete.

Then our knight he seized the axe,

From the guard who’d just attacked,

And let go of the man he still held,

Since to defend himself seemed well;

The knights from the doorway again

Attacking him, with the three axemen,

And assailing him most cruelly.

To save himself he leapt promptly

Between the bed there and the wall,

And cried aloud: ‘Now, come you all!

For if you were five and thirty yet,

To receive you I am now well set,

And you’ll meet with battle enough;

I’ll not be beaten by such poor stuff.’

But the maid who gazed at him said:

‘By my eyes, you need have no dread

Of all such in future where I may be.’

And she dismissed, immediately,

All the knights and men-at-arms,

And they retired, free of more alarms,

Raising no objection, without delay.

While she took it upon herself to say:

‘Sir, you have defended me bravely

Against all my household company;

Come now, and I’ll lead you, withal.’

Hand in hand, they entered the hall,

Yet, as to her, he felt no pleasure,

Though set to enjoy her at leisure.

Lines 1207-1292 The Knight resists the maiden

A BED was there, amidst the hall,

Its sheets were not disturbed at all,

But broad and white, and covered o’er;

Nor was this bed a thing of straw,

Nor with coarser fabrics spread;

A twin coverlet of silk instead,

Upon its mattress had been laid.

Down upon it now lays the maid,

But without shedding her chemise,

While he is scarcely at his ease

Untying and removing his hose,

Sweating to divest of his clothes;

Yet in the midst of his distress

His promise doth upon him press.

Whence is its power? Such its force

It urges and dictates his course,

Promise demands the debt be paid,

He must lie down beside the maid.

So down he lies now without delay,

But does not his naked form display,

Retaining his shirt as had she.

Nor does he touch her carelessly,

But keeps afar, and turns away,

Not a word to her doth he say

Like a novice forbidden speech,

Once he his own cot doth reach.

Nor does he turn on her his gaze,

Nor look towards her in any way.

He can show her not one courtesy.

Why? His heart’s not moved you see.

She was gentle indeed and fair,

But not everything gentle and fair

Pleases everyone equally.

The heart he possessed was not free,

He had but one heart, and moreover

It was commanded by another.

He could not bestow it elsewhere.

Love, that has all hearts in its care,

Allows them all their proper place.

All? Only those in its good grace.

Who Love deigns to rule by law,

Ought to esteem himself the more.

Love so prized and esteemed his heart

It thus constrained him; for his part,

He was so proud of Love’s decree,

I could not blame him certainly

For spurning what Love did not wish,

Holding to what he should cherish;

While the maid could clearly see

He was averse to her company,

Nor would he suffer it willingly,

And, having no desire to be

With her, would not seek to please her.

‘If it would not displease you, sir,’

She said, ‘I’ll leave you here, and I

Will go to my own bed by and by,

So that you will be more at ease,

For I believe they cannot please,

My company, my society.

Do not think it a treachery,

If I but tell you what I feel;

And now let sleep upon you steal,

For you have so kept your promise,

That there is nothing more I’d wish

To ask of you, nor have the right.

I commend you to God, sir knight,

And thus I go.’ So doth she leave,

Nor at their parting does he grieve,

But lets her leave him, willingly,

As one committed previously

To another; as the maid well sees,

And knows thus the thing must be.

So to her room she went instead,

Retiring, full naked, to her bed,

And there to herself she mused:

‘Of all the knights I ever knew,

I know not one, compared to him,

Worth the third part of an angevin;

I see he pursues some great affair,

Graver than knight did ever dare,

And, equally, far more perilous.

God grant he return victorious!’

Then, falling asleep, she slept on

Till the sun shone clear at dawn.

Lines 1293-1368 The Knight and the maiden ride out together

AS soon as it was day, then she,

Rose and dressed immediately.

And the knight, he too awoke,

Dressed himself, and donned his cloak,

And armed himself, without aid.

And soon there arrived the maid

Who saw he was already dressed.

‘May this day prove of the best,’

She said, on seeing him, ‘for you.’

‘And for you may it prove so too,’

Answered the knight, for his part,

Adding that he would make a start

If but his horse be brought outside.

The maiden now called up his ride,

And said: ‘Sir, I would travel today,

Awhile with you, along the way,

If you’d escort me beside you

And so conduct me according to

The custom and usage I once knew

Before we were held in Logres.’

(This custom, these privileges

Were such that a knight, at that day,

Meeting a lone maid, on his way,

Would no more mistreat the same

Nor dishonour her, if he his fame

Would maintain as a man of note,

Than he would seek to cut his throat.

If he treated her ill in short,

He’d be shunned in every court.

But if, on the way, another knight

Challenged him to stand and fight,

And then by arms fairly won her

The latter could then do with her

As he wished, and without shame,

Or attracting an ounce of blame.)

That is the reason that the maid

Said that she’d go with him that day,

If he was brave enough and would,

According to custom, be so good,

As to protect her from all harm.

And he replied: ‘Have no alarm,

None shall offend, I promise you,

Without he first pay me his due.’

‘Then I will go with you,’ she said.

She ordered her palfrey to be led

To her, saddled, and it was done.

Her palfrey was brought at once,

And his war-horse to the knight,

Then they both mounted outright,

Without aid, and they rode away.

She spoke to him, but he no way

Cared for aught that she offered,

And not one word did he proffer.

Thought pleased him, words did not.

Oft Love re-opened, if he forgot,

The wound that it had dealt before,

Yet for neither comfort nor cure

Did he seek to address his wound,

Having no wish to ease his wound,

Nor seek a doctor or any balm,

Should it do him no greater harm,

But one whom he’d seek willingly.

Thus they took their way directly,

By roads and tracks, in the main,

Until they arrived at a fountain.

The fountain, set amidst a meadow,

Fell to a stone basin below,

And on the stone, we must assume,

Someone had left, I know not whom,

A comb of ivory inlaid with gold,

Such as never, since days of old,

Was seen by the foolish or the wise;

And wound in its teeth there lies

Almost half a handful of hair

Left by her who’d used it there.

Lines 1369-1552 The fountain, the comb, and the tresses of hair

WHEN the maiden, and she alone,

Saw the fount and basin of stone,

She, not wishing the knight to see,

Then took another path, hurriedly;

While, lost in his thoughts, the knight,

Who in his thoughts did much delight,

Did not at once perceive that she

Had turned aside, misleadingly;

But once the turn he did perceive,

Thought it designed to deceive,

And that she had turned aside

From the path they both did ride

To escape some danger there.

‘Maiden, ‘he cried, ‘now beware,

You go astray; the way lies here;

For none do go aright, I fear,

Who from the true road depart.’

‘Sir, on the better path we start,’

Said the maiden, ‘so I believe.’

He replied: ‘What you conceive,

My maid, to me is less than clear,

But plain enough I see that here,

Before me, lies the beaten way,

And, having come thus far, I say

I will not take some other road;

Take with me the path we rode,

For to this path I shall adhere.’

So they advanced till they came near

The stone, and now the comb he saw.

‘I cannot,’ said the knight, ‘I’m sure,

Remember seeing, far or near,

So fine a comb as I see here.’

‘Hand it’ the maiden said, ‘to me.’

And he replied: ‘Most willingly.’

Then he bent, and took the comb.

As he held it, his gaze did roam

Over the hair entwined, awhile,

At which the maid began to smile.

Seeing this, he begged her to say

Why she smiled in such a way.

And she replied: ‘Be silent, now,

For I shall tell you naught, I vow.’

‘Why?’ said he, ‘Because I choose.’

He, on hearing her thus refuse,

Conjured her, as a believer

In lover staying true to lover,

Each he to she, and she to he:

‘If you, ‘he says, ‘a lover be,

My maid, by that I conjure you,

And beg, and implore you too,

Hide not the reason then from me.’

‘You press me so hard,’ said she,

Indeed you cannot be denied,

I’ll tell you all and nothing hide.

This comb, if I know nothing more,

It was the queen’s, I am full sure.

And this, I say, you may believe,

That those strands of hair you see,

So fine and radiant and bright,

Woven in the teeth, sir knight,

The queen’s head itself has owned,

They in no other place have grown.’

‘By my faith,’ the knight replied,

‘Here many a king and queen abide,

Whom do you speak of, which queen?’

And she said: ‘By my faith, I mean

King Arthur’s wife, for it is she.’

When he heard this he could barely

Keep from bowing his head low,

Bending towards his saddle-bow.

Seeing his feelings thus displayed,

She wondered at him, for the maid

Fearing the consequence of all,

Thought him now about to fall.

If she was afraid, blame her not,

For he might swoon she thought.

And that were true, for so he might

So near to swooning was the knight;

For in his heart he felt such grief,

His colour paled, his power of speech

Was for a long while suspended.

The maiden quickly descended,

And ran as swiftly as any maid

To support him and bring him aid;

Not for anything would she seek

To see him fall there at her feet.

On seeing her, the knight felt shame,

And wishing to know why she came

To his aid, said: ‘What need is here?’

Do not think she confessed her fear

Or told him the why and wherefore.

For it would have brought him more

Shame and anguish had she spoken,

And grieved him more than a token,

If she’d confessed the truth indeed,

So she concealed it tactfully:

‘I descended to seek the comb,

Sir, for that reason have I come,

No more delay could I stand

Before I held it in my hand.’

And he who wished her to have

The comb gave it her now, save

That he first drew forth the hair.

Never did human eye, I declare,

See anything receive such honour;

For he commenced then to gather

It to him, so he might adore

The hair a hundred times and more,

Touching it to lips, eyes and brow;

Showing such joy as hearts allow.

Happy he feels himself and wealthy.

He places the tresses now, gently,

Beneath his shirt against his heart.

He’d not exchange them for a cart

Filled with emeralds and rubies.

Nor does he fear now that he

Will be afflicted with sores and pains;

Ground gems and pearls he disdains,

And the pleurisy and the leprosy,

For St. Jacques, St. Martin, has he

No need, he’s such faith in her hair

He requires no other comfort there.

What did these tresses resemble?

If I say, you’ll think I dissemble,

Or that I play the fool indeed.

When at the fair near St Denis

The stalls are full, riches galore,

By all of them he’d set no store

Unless he found those tresses there,

In proven truth, that shining hair.

And if of me the truth you’d find,

Then gold a hundred times refined,

And then as many more, its light

Would prove darker than the night

When tis compared to brightest day,

The brightest of the year, I say,

If beside the gold you set that hair,

And one with another did compare.

But why should I the tale prolong?

The maid remounted before long,

With the comb, while the knight

Transported was, in sheer delight

At bearing the tresses at his breast.

Leaving the plain they progressed

Through a forest, without delay,

Until they came to a narrow way,

Where one must ride after another,

It being impossible to do other,

Since two could not ride abreast.

The maid rode ahead of her guest,

Swiftly along this straight row,

And where it was most narrow,

They saw a knight approaching.

The maiden at once recognising

Him, when she saw him nearer,

Turned to the knight behind her

And said: ‘Sir knight, do you see

This man who approaches swiftly,

All armed and ready for the fray?

He will hope to lead me away

With him, thinking me defenceless.

For his intentions I can guess;

He loves me, though tis all unwise,

He sends me messages and tries

To woo me, and long has done.

But my love’s not for such a one,

I could not take him as my lover;

So help me God, I would rather

Die than on him bestow my love.

I do not doubt that joy doth move

Him now, and he feels great delight

As if he already owns me outright;

Yet now shall I see what you can do,

And you may show your bravery too;

Then shall I see, and you may show

That you can protect me from woe.

If you can guarantee my safety

Then I’ll proclaim, and truthfully,

That you are right noble and brave.’

And he replied: ‘On! And no delay!’

And that was as much as to say:

‘At nothing need you feel dismay,

For little am I concerned at all

By these words that on me do call.’

Lines 1553-1660 The Knight of the Cart champions the maiden

WHILE they rode on conversing so,

The other knight advanced also;

He was alone, and riding swiftly

So as to meet with them directly;

All the more eager to make haste,

Thinking not the chance to waste;

By his own good fortune moved,

On seeing her whom he so loved.

As soon as he comes closer to her,

With heartfelt words he greets her,

Saying: ‘May she I most long for,

Though grief not joy cometh before,

Be most welcome, where’er come from!’

Tis not fitting that she play dumb,

Given the warmth of his greeting,

Or be tardy in replying,

To his welcome with her tongue.

The knight though is done no wrong,

By her saluting him aright

For indeed her words are light,

Nor does the effort cost her aught.

Yet had he victoriously fought

In some joust or tournament

He’d not have felt, at that moment,

Worthier, nor could have found

More honour there or more renown.

Feeling his own self-worth regained,

He seized her horse’s bridle-rein,

Saying: ‘Now I shall lead you away;

For I’ve sailed well and true this day,

To reach so fine a harbour here.

My troubles are at an end, tis clear:

From danger have I come to port,

From sorrow to the joy I sought,

From great ill to perfect health,

Now have I my wish, my wealth,

Finding your state such as I see,

Where I may lead you on with me,

At once, without your saying no.’

She replied: ‘Naught tells you so,

For this knight is escorting me.’

‘He’ll prove of little worth to be,’

He said, ‘when I lead you away.

Sooner a peck of salt, or three,

He might eat, this knight, I see,

Than defend you now from me.

No knight there is, in my view,

From whom I would not win you.

Finding you here so opportunely,

Despite what he may do to thwart me,

I’ll lead you off, before his eyes,

While his every effort I despise.’

The Knight of the Cart ignored

This show of pride, voiced abroad,

But, without boast or impudence,

Challenged him, in her defence,

Saying: ‘Be not, sir, in such haste,

Nor your words so lightly waste,

But speak a little more reasonably;

For I shall not deprive you, I see,

Of any right, in her, you possess.

In my care and protection, no less,

The maid is here, so do no wrong;

Leave her, for you hold her too long;

She is not yet under your protection.’

The other knight gives him direction

To burn him, if he take her not despite

Him, but he replies: ‘No, sir knight;

It would not be well if I so allowed.

I would prefer to fight you, I vow.

Yet, indeed, if we wish to fight,

Here we cannot do so aright,

In this narrow road, I maintain.

Let us go to some place again,

Wide enough, an open field or

Meadow.’ He demands no more,

The knight replies: ‘Most certainly,

You are not wrong, for I agree

This place is too narrow, I fear;

My steed is so hampered here,

That ere I can make him wheel

His flanks will be crushed I feel.’

Then, in much distress, he wheeled,

Though his steed no hurt revealed,

Nor was it harmed in any manner,

And said: ‘Indeed, it doth me anger

That no better a place can we muster

For our fight, nor be seen by others,

For I’d wish all to understand

Which of us is the better man.

But come now, let us make haste,

And we’ll find near to this place

Somewhere wide open and clear.’

Thus they came to a meadow near:

And this meadow was full of girls,

A host of knights and demoiselles,

Who that pleasant place employed

For the diverse games they enjoyed.

Nor were their games mere emptiness,

Some played backgammon, some chess,

While others played dice, happily;

Plus poins, hazard, and passe-dix.

Most of the folk played at these,

But others there they took their ease

Reliving their childhood joyfully;

Danced roundels, caroles, merrily,

Sang, and tumbled, leapt in the air,

Or wrestled each other, pair by pair.

Lines 1661-1840 A father’s command avoids an immediate encounter

ON the far side of the green

An elderly knight could be seen,

Mounted upon a Spanish sorrel;

Golden were his saddle and bridle,

And his hair was tinged with grey.

One hand rested, with easy grace

At his side; in shirt-sleeves was he,

Since the day was clear and lovely,

Watching the dances and the play.

Over his shoulders he did display

A fine mantle of scarlet and vair.

On the other side, by the path there,

Were twenty armed knights and three,

All mounted on good Irish steeds.

As soon as the newcomers appeared,

All ceased their play, as they neared,

And round the meadow cried loudly:

‘Now yonder comes the knight, see,

Who was carried along in the cart!

Let none here their games restart,

While this knight is here among us;

Cursed be those who continue thus,

Cursed be those who seek to play

While he is in this meadow today.’

Meanwhile the other knight, he

Who loved the maiden loyally,

And held her to be his delight,

Being son to the elderly knight,

Approached his father and said:

‘Sire, I have won great happiness,

Who would hear me, hear now,

For God has given me, I vow,

All I wish, nor were it a greater

Gift if He had crowned me here,

No greater thanks would I owe,

Nor greater gain would I show,

For what I gain is good and fair.’

‘I know not if tis thine, I swear,’

Said the noble father to his son.

Swiftly the knight replied in one:

‘You know not? Can you not see?

Before God, Sire, doubt not me,

While you can see I hold her fast.

In the wood through which I passed

I met with her now, on the way.

I think God led her there today,

And I have taken her for my own.’

‘I know not that he will condone

Such, who follows after you now;

He’ll challenge you, I do avow.’

While they spoke all were pleased

To listen, for the games had ceased

On the instant our knight arrived,

All pleasure and gaiety had died,

Due to their scorn and enmity.

But the Knight of the Cart swiftly

After the maid now did follow,

Saying: ‘Knight, let the maid go,

She to whom you have no right!

If you’re brave enough, I’ll fight,

And I will defend her from you.’

Then the elderly knight spoke too:

‘Did I not claim it would prove so?

Fair son, now let the maiden go,

No longer seek her to detain.’

His son, displeased, is not fain

To do so; he swears he will not,

Saying: ‘May God to this my lot

Deny all joy, if I yield her though!

I have her and will hold her so,

As a thing that is bound to me.

Every strap of my shield shall be

Severed, and it be torn away

And I must lose all faith, I say,

In my arms, and in my defence,

My lance and sword, and my strength,

Before I will yield the one I love.’

His father replied: ‘I’ll not approve

Such an encounter, nonetheless.

You trust too much in your prowess;

Instead, do now as I command.’

‘Am I a child, who at your demand,

Should be filled with fear? Nay, with pride

Rather, I should boast,’ he replied,

‘That there’s no knight, from sea to sea,

Where’er within this land may be,

Strong enough that I’d e’er yield her;

Not one whom I would fail, I aver,

To defeat, and in no short order.’

‘I know, dear son’ said his father,

‘That this you do believe; indeed

You trust your powers, I concede,

And yet I would not wish this day

To see you thus attempt the fray.’

‘I would be shamed, so I avow,

‘Were I to accept your counsel now,’

His son replied. ‘For cursed be he

Who doth; such must a recreant be

On account of you, nor seek to win.

Tis true we fare ill among our kin;

A better bargain I could make

With some stranger, and no mistake.

I swear that in some other place

I’d be received with better grace.

None who were unknown to me

Would thwart my will to this degree,

Yet here is annoyance and torment,

And great, therefore, my discontent

That you would find fault with me;

Yet he who finds fault so readily

Will ne’er bring a man to shame,

Merely his will the more inflame.

Should I not all my strength employ

In this, may God ne’er grant me joy,

But rather, in spite of you, I’ll conquer.’

‘I see,’ said his father, ‘by Saint Peter

‘And the faith I hold in him, that my

Advice is worth nothing in your eyes,

And I’d waste my time rebuking you.

But I shall summon up means anew

Such that, despite what you desire

Yet will you do all I require,

And will submit to my command.’

Straight away he summoned a band

Of stalwart knights; it being done,

He ordered them to detain his son,

Whom he would see safe and sound.

And said: ‘I shall have him bound,

Rather than he be allowed to fight;

You here are my band of knights,

Who owe me love and loyalty;

By the lands you hold from me,

I have summoned you to my side.

My son appears drunk with pride,

Half-mad indeed it seems to me,

He scorns to behave respectfully.’

They reply they will handle him,

Nor while they have charge of him

Will they allow the son to fight,

And he shall renounce outright,

Despite his wishes, the fair maiden.

They seized him, as they were bidden,

Gripping him by neck and shoulder.

‘Do you not think’, said his father,

‘Yourself a fool now? Confess tis true,

Your strength proves little use to you,

You lack the power to joust or fight,

However difficult it might

Be, or painful, to say tis so.

You will be wise to do also

What pleases me and I desire.

Do you not know what I require?

So as to lessen your frustration

We’ll follow, if tis your inclination,

This knight, today and tomorrow,

Through every last grove and hollow,

And each well-mounted, you and I.

We may perhaps at length descry

From his bearing and character,

That I would be right to concur,

And let you fight him as you wish.’

His son felt bound to accept all this,

Despite himself; like one who must

Accept whatever he can’t adjust,

He said that he would suffer it so,

Provided that both of them did go.

When the folk in the meadow knew

Of the adventure both had in view,

They said: ‘See how, by some art,

He who was mounted on that cart

Has gained such honour here today

That this maiden he leads away,

The friend of the son of my lord,

And my lord allows it. Be assured,

He must find some worth in him now

That this departure he doth allow.

Yet him a hundred times cursed be

Who halts his sport for such as he!

Play on.’ And they began once more

Their games and dances, as before.

The End of Part I of Lancelot