Chrétien de Troyes

Érec and Énide

Part II

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2018 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Lines 1845-1914 Érec fulfils his promise to his host

- Lines 1915-2024 Arthur summons the counts and kings to court

- Lines 2025-2068 Érec and Énide are wed

- Lines 2069-2134 The wedding-night

- Lines 2135-2292 The tournament

- Lines 2293-2764 Énide’s mischance

- Lines 2765-2924 Érec defeats the three robbers

- Lines 2925-3085 Érec defeats the five knights

- Lines 3086-3208 Érec and Énide meet a squire and reach a town

- Lines 3209-3458 The Count desires Énide: she deceives him

- Lines 3459-3662 Érec escapes and defeats the Count, who recants

Lines 1845-1914 Érec fulfils his promise to his host

WHEN the kiss had been received,

As customary, and none aggrieved,

Érec, both kindly and courteous,

Now proved himself solicitous.

For he showed no wish to evade

The promises that he had made.

Right well he kept the covenant;

For to the freeman now he sent

Five sumpter mules, fat and strong,

Bearing clothes and goods along,

Buckrams, scarlets, robes of state,

Golden marks, and silver plate,

Furs of vair, of grey, and sable,

Purples, silks, the stuff of fable.

The mules loaded, as he’d agreed,

With all a gentleman might need,

He ordered a troop of ten knights,

And sergeants, his men by right,

To accompany the baggage train

To his host, and salute the same,

Greeting the man as he might do,

Showing him great honour too,

And honouring his wife equally,

As he would do, if it were he;

And when they had presented both

With the mules, the goods and cloth,

The gold and silver, and rich things,

With all the rest of the furnishings

That were in those bags and bales,

Into his new realm of Far Wales

They were to conduct the freeman,

And his wife, while honouring them.

He had promised them two towns,

Best situated and most renowned,

And the least likely to be assailed

In all that country of Far Wales.

Montrevel was the name of one,

And the other was called Roadan.

When they arrived in his kingdom,

Those two castles would become,

Theirs, with their rents, in law,

As he had promised them before.

And these things were done then,

As Érec had commanded them.

The mules, silver, and the gold,

With the robes, of which, all told,

There were a host, they presented

To the freeman as Érec intended;

Then escorted him swiftly there,

With no lack of thought or care.

They led him into Érec’s realm,

And sought to attend him well,

Arriving there on the third day;

Now both towns his rule obey.

King Lac at this made no demur,

But welcomed him with honour,

Befriending him for Érec’s sake,

Granting him title to his estates,

And thus establishing his rights

Over the burghers and the knights,

Who were to reverence him now

As their liege lord, and so did vow.

And when all was accounted for,

The escort returned once more,

To Érec, their own lord, and he,

Received them right joyfully;

Asked for news from his men,

Of the host, his wife, and then

Of his father and of the realm;

And they had only good to tell.

Lines 1915-2024 Arthur summons the counts and kings to court

NOT long after, it would appear

An appropriate time drew near,

To celebrate the wedding day.

Érec had sorrowed at the delay;

He could not endure the waiting,

So sought audience of the king,

To ask him, if it pleased his lord,

To see them married at the court.

The king granted him that boon,

And sent messengers, full soon,

To all the counts and the kings

Who held land as his liegemen,

Saying it would be to their cost,

Not to be present at Pentecost.

None dared refuse the demand,

It being the king’s command;

They must all attend the court.

Now, attend me, as you ought!

I will list the counts and kings:

There, with a wealthy gathering,

Brandes, Count of Gloucester,

And then a hundred followers.

After him came Menagormon,

Who was Count of Clivelon.

And he of the Haute Montaigne,

With his rich company he came;

The Count of Treverain, also,

With a hundred knights in tow;

And after him Count Godegrain

With no less numerous a train.

With those above I mentioned,

Came Maheloas, a great baron,

The Lord of the Isle of Voirre.

In that isle no tempests lower;

No thunder, no lightning there,

There no toads or serpents fare,

Nor does it ever freeze or burn.

Graislemier of Fine Posterne,

Brings, with twenty companions,

The Lord of the Isle of Avalon,

Who is his brother, Guigomar,

And of the latter, they said afar

He was friend to Morgan le Fay:

It was proven truth they say.

Davit of Tintagel, he was there,

Who never suffered grief or care.

The Duke of Haut Bois, Guergesin,

He brought gear of worth with him.

Dukes and counts, many they saw,

But of kings there were still more.

Garras of Cork, a king of might,

Came with five hundred knights,

In mantles and fine hose arrayed,

And tunics worked in silk brocade.

Riding a Cappadocian stallion,

Came Aguisel, King of Scotland;

Nor his two sons did he forget,

He brought both, Coi and Cadret,

Two knights both well-acclaimed.

Along with those I have named,

Came King Ban of Gomeret,

His company young men as yet;

All those with him appeared

Without moustache or beard;

Many a joyful youth he brought,

Two hundred from his court,

And each man had, so they tell,

A female falcon, or a tiercel,

A merlin or a sparrow hawk,

Or a fine mewed goshawk.

Kerrin, the old King of Riel,

Brought with him no youths at all,

But three hundred of his peers,

The youngest had seven score years.

Their hair was white as snow,

(For they were born long ago)

With beards down to their waists,

Arthur welcomed them with grace.

The Lord of the Dwarfs next he sees,

Bilis, the King of Antipodes.

That king, he was a dwarf also,

Yet the brother of Brien; though

Bilis was the smallest of all,

Brien was tallest of the tall,

A half-foot, or a hand, taller,

Was that knight than any other.

Showing wealth and authority,

Bilis brought, in his company,

Two kings, both dwarfs again,

Who held from him their terrain,

Named Grigoras and Glecidalan,

All marvelled at them, to a man.

When to the court they came,

They were treated just the same,

As kings; like kings at court,

All three esteemed, in short;

For they were true gentlemen.

When, in brief, Arthur, then

Saw his nobles play their part,

He felt great joy at heart.

Then to enhance his delight,

In order to dub each a knight

A hundred squires were bathed there.

Each of them had a robe en vair,

Rich brocade of Alexandria,

Each one choosing to appear

In whichever one took his fancy.

Yet in one coat of arms all agree,

And in horses swift, all aquiver,

The least worth a hundred livres.

Lines 2025-2068 Érec and Énide are wed

NOW when his wife to Érec came,

He needs call her by her true name:

For a woman is not truly wed,

If her true name is left unsaid.

As yet her name was a mystery;

Now it was first known openly;

Her baptismal name was ENIDE,

The Archbishop of Canterbury,

Who had travelled to the court,

Blessed the couple, as he sought.

When they were gathered there,

No minstrel dwelling anywhere,

Who possessed a pleasing skill,

Came not to court of his own will.

In the great hall all were alight,

Each providing what he might;

Leaping, tumbling, conjuring,

One recites, while others sing,

One whistles, one sounds a note,

One on the harp, one the rote,

One the flute, and one the fiddle,

One the pipe, and one the viol.

All the girls there dance and sing,

Happily, with each other, vying.

There is naught that we employ

Of all that fills the heart with joy,

That was not performed that day.

Sounds the tabor, sounds away

The timbrel drum, the reed pipes,

Trumpets, horns, fifes, bagpipes.

What more is there to mention?

Every gate and door was open,

Every egress and every entry

Was free to all, squire or gentry,

Rich or poor, none turned away.

King Arthur, generous that day,

Gave it out that all the bakers,

All the cooks, and the butlers,

Should serve everyone freely

Whatever they wished for greatly;

Bread and wine and venison,

And no request from anyone

Without them being satisfied

And no wish of theirs denied.

Lines 2069-2134 The wedding-night

GREAT the joy in the palace,

Yet over most of it I will pass,

And tell of the joy and delight

In the bed-chamber, that night.

Bishops, archbishops were there

On that night they spent together,

Their very first, and in their case,

No Brangien took Iseult’s place,

All was as true as had gone before.

The queen herself, she oversaw

It all, in a manner most sincere,

For both to her were very dear.

The hunted stag whose thirst is sore

Does not desire the fountain more,

Nor does the sparrow hawk return

To hand, more swiftly, its food to earn,

Then did these two come together,

In close embrace, the naked lovers,

That single night compensating

For their long hours of waiting.

Once all depart their presence,

They gratify their every sense.

Their eyes delight in every gaze,

Being of love the true pathways,

Bearing a message to the heart:

Deeper the gaze, sharper the dart.

After the message of the eyes,

Comes the greater sweetness lies

In kisses, that to love invite.

Both in this sweetness delight,

And their hearts drink so deep,

They can barely think of sleep:

With kisses then at first they toy,

And the love that brings such joy,

Fills the maiden with boldness,

So that she, free of all coyness,

Bears all that she must suffer,

Before she wakes, as another.

She has lost the name of maid.

A woman, by the dawn, remade.

The minstrels were full of glee,

Rewarded, that day, handsomely,

Recompensed for all they played,

With many a fine gift well repaid;

With fair robes, ermine and vair,

With cony-skins, rich purple wear,

Scarlet cloth, and silken stuff:

Whether a horse, or coin enough,

Each man, according to his skill,

Was granted whatever he will.

Thus the court and wedding feast

Lasted a fortnight at the least,

Full of joy, and held at leisure.

For his glory and his pleasure,

And for Érec’s greater honour,

The knights were told by Arthur

To stay a fortnight, at his command,

And when the third week began

All agreed, by common consent,

To enact a lavish tournament;

And my lord Gawain gave surety

On his side that the site would be

Between Evroic and Tenebroc;

While Meliz and Meriadoc

Gave surety on the other side.

All then dispersed, far and wide.

Lines 2135-2292 The tournament

ONE month after Pentecost

They assembled for the joust,

In the plain below Tenebroc,

Many a banner there en bloc,

Vermilion, white and blue,

Many a sleeve and veil too,

Bestowed as a love token;

Many a lance was broken,

With pennant argent seen,

Azure, gold, heraldic green;

And many a device there,

Some striped, some en vair.

Many a helmet was laced,

Gold or bright steel braced,

Green, yellow, red, I say,

Mirroring the sun that day;

So many swords tightly girt,

Scutcheons and white hauberks;

So many shields fresh and new,

Silver, green, and azure blue,

With buckles of solid gold;

So many steeds fine and bold,

Black, white, sorrel, and bay,

Gathered for the grand affray.

With arms the field is littered,

On either side the ranks quiver,

The roar not destined to abate.

The shock of the lance is great;

Shield pierced, lance shattered,

Iron mail is dinted, battered;

Saddles empty, knights roam,

The horses sweat and foam.

Swords are swiftly directed

At all those noisily ejected.

Some seek to be ransomed,

By others that disgrace shunned.

Érec rode a white steed, his own,

At the head of the line, alone,

Ready to joust with any knight.

Against him, a splendid sight,

Came Orguelleus de la Lande,

Astride his mount from Ireland,

Bearing him with fire and zest.

On the shield before his breast,

Érec struck him with such force

He knocked him from his horse.

He left him prone and passed on,

Then came against him Raindurant,

Son of the Old Dame of Tergalo;

He in blue candal silk was clothed,

A knight he was of great prowess.

Each one the other now addressed,

And dealt each other fierce blows

Where at the neck the shields rose.

Érec, from a lance’s length, found

Strength to lay him on the ground.

As he rode slowly back then he

Met with the King of the Red City,

Who was both valiant and bold.

Of their reins they take tight hold,

Grasp their shields by the leather,

Both equipped with solid armour,

And fine horses, swift and strong,

The shields new, fresh the thongs.

With such force they dash together

That their two lances splinter;

Never was such a fierce clash seen:

Hurtling over the ground between,

Went horses, shields, and weapons.

Not girth, breast-strap, reins, none

Could prevent the king, unhorsed,

Striking the ground, in his course.

Sent flying, thus, from his steed,

Saddle and stirrup and, indeed,

Even the reins of the bridle,

Are carried away in his fall.

All the crowd standing there,

Marvelling at the fall, declare,

It will cost him dear to fight

With such a skilful knight.

Érec wished to capture neither

The horse nor its fallen rider,

But to joust and win the field,

That his prowess be revealed.

Before him the lines tremble;

His prowess now heartens all

The men who fight on his side.

Knights, and the mounts they ride,

He takes, to his foe’s discomfort.

Of how my lord Gawain fought,

I’d now speak, for he did well,

For he there unhorsed Guincel,

And took Gaudin of the Mount;

Captured both knight and mount:

He fought well, my lord Gawain.

Girflet, the son of Do, Yvain,

And Sagramor the Headstrong,

So drove their opponents along,

They harried them to the gate,

Capturing many, soon and late.

Before the entrance to the town

Fresh cause to fight they found,

Those inside fought those before,

And there unhorsed Sagramor,

Who was a very valiant knight.

He was near captured in the fight,

But Érec spurred on to the rescue,

Breaking a lance to save him too;

He strikes one on the breast so

He quits the saddle at the blow.

Then wields the sword, advances

Crushing helms, breaking lances.

Some flee, and some evade him;

For even the boldest fear him.

He deals many a thrust and blow,

Freeing Sagremor from the foe;

Into the town then drives them all.

Now, vespers done, shadows fall.

So well did Érec contest the affray,

He was the best who fought that day.

Yet on the morrow he did better,

Taking so many knights moreover,

Leaving so many saddles bare,

That none but those present there

Could believe how well he fought.

On both sides those of the court

Said that with sword and shield

He had conquered all the field.

Now Érec had won such honour,

That men murmured of no other,

Not one was held in such grace:

He resembled Absalom in face,

In wisdom seemed a Solomon,

In boldness a very Samson,

And in generosity and candour

The equal of King Alexander.

After the tournament, returning,

Érec had audience of the king.

He requested leave, humbly,

To travel to his own country;

But first he gave thanks to Arthur

For showing him such great honour,

As one frank, courteous and wise;

Deep was his gratitude likewise.

Then asked to be granted freedom

To go and visit his own kingdom,

And take his wife with him also.

To this the king could not say no;

Yet he wished Érec might stay.

He gave him leave, yet did pray

That he would return full soon;

For in his court there was none

Finer or more valiant, he knew,

Save Gawain, his dear nephew;

With whom none could compare.

After him the most prized there

Was Érec, who to him was dearer

Among his knights than any other.

Lines 2293-2764 Énide’s mischance

EREC stayed no longer there,

Telling his wife to prepare,

As soon the king gave leave;

Retaining in his company,

Sixty worthy mounted men,

Cloaked in vair or grey, and then

Once he was ready for the road

He tarried no more in that abode;

But took leave of the queen again,

Commending to God his men;

The queen grants leave to depart.

At the hour of prime they start,

From the heights of the palace.

Before all he mounts his horse,

And his wife mounts the palfrey

Ridden from her own country;

Then all his company mounted,

More than seven score all counted,

Of knights, and squires, and all.

After full four days of travel,

Over hill and dale and through

Forests, plains, and rivers too,

To Carnant on the fifth they came,

Which place King Lac had claimed

As his seat, a pleasant town.

None did a more pleasant own:

With forest and meadow-land,

Vineyards and farms to hand,

Fountains and orchards fair,

Knights and ladies everywhere,

And youths a plenty in fine fettle,

Well-mannered clerks and gentle,

Who spend their money freely;

Charming girls too, and lovely;

With prosperous burghers, also

The town and castle overflow.

Before Érec reached the site,

In advance he sent two knights,

To tell the king of his coming.

As soon as they gained a hearing,

He had knights, clerks, and damsels,

Mount their horses, while the bells

He promptly ordered to be rung,

And all the streets to be hung

With tapestries and silks bright,

To welcome his son with delight:

Then he himself mounts his steed.

Four score clerks of noble breed,

Honourable, gentle, and right able,

In grey cloaks trimmed with sable;

And five hundred knights that day,

On sorrels, bays, or dapple greys;

Burghers and their wives are there,

The crowd vast, beyond compare.

He and Érec advanced together,

Until each recognised the other,

Then dismounted to meet as one,

In fond embrace, father and son.

Long they embrace and do greet

In the place where they first meet,

Not stirring, clasping one another,

The father the son, the son the father.

In Érec the king does much delight,

Then he separates from the knight,

And turns his face towards Énide,

On either side on honey does feed.

Both he kisses and does embrace,

Which pleases more he cannot say.

They with pleasure enter the castle,

Advancing now to the peal of bells,

All in honour of Érec’s presence.

Irises, reeds, mint, make pleasant,

The streets where they are strewn,

And overhead like sun and moon

Hang coverings and tapestries,

Bright silk and satin subtleties.

There was great joy on every side:

People gathered from far and wide,

To catch a sight of their new lord

And greater delight none ever saw,

Than shown here by old and young.

First to the church he walks along:

The people, in procession, express

All their devotion and devoutness.

At the Altar of the Crucifix, he

Made reverence, on his knees.

While Érec’s lovely bride, she

Was led to the statue of Our Lady.

When she had offered up a prayer,

She stepped back, pausing there,

Crossing herself with her right hand,

In a manner the noble understand.

Then from the church they exited,

And entered the palace in its stead.

There the festivities began.

That day had Érec gifts in hand,

From the burghers and the lords,

From one a palfrey of the north,

From another a cup of gold;

One presents a goshawk bold,

One a greyhound, one a setter,

A sparrow-hawk, and a better

Gift still, a Spanish stallion;

One a shield, an ensign one,

One a helmet, one a sword.

Never a prince with such accord

To his realm was welcomed yet,

Nor with more delight was met;

All striving to serve him well.

But more was made, I must tell,

Of Énide, than was made of him,

For her beauty, without and in;

And still more for her openness.

She was seated, their royal guest,

On a brocaded cushion, brought

From Thessaly to King Lac’s court;

Round her was many a lovely lady,

Yet she was many times more lovely:

As the brilliant gem that glows

Outshines dull flint, or as the rose

Exceeds the poppy, so lovelier

Was this Énide than any other

Woman or maid in all the world,

Wherever might dwell such a girl.

She was so gentle, so honourable,

So wise in speech, and so affable

Fine at heart, and fine in bearing,

No one could ever be so glaring

As to accuse her of any folly,

Malice, or scheme of villainy.

She had been so well schooled

That she had acquired all virtue,

All to which any girl might own,

With wisdom and kindness sown.

All loved her for her openness:

All felt themselves doubly blessed,

Who could serve her in any form.

None claimed she brought any harm;

For none knew of any harm to claim.

No woman with so virtuous a name

Lived in that realm, nor in any other.

But Érec with such a love loved her,

He cared for arms no more, nor went

Desiring the joys of tournament,

Nor wished to joust any longer,

Rather his love for her grew stronger.

She was his lover and his friend,

His heart was devoted to that end;

Kissing her oft, in fond embrace;

Seeking no other kind of solace.

His companions quietly grieved,

And among themselves believed

That he now loved her to excess.

It was afternoon before he dressed,

Before he chose to leave her side.

He was happy, none could deny.

He forever sought her society,

Yet nevertheless was still as free

And open-handed with his men,

Arming, clothing, enriching them.

There was never a tournament

To which the men were not sent,

Well-equipped, and finely dressed.

Whatever the cost they had the best;

Fresh horses he gave freely,

For the jousting and the tourney.

All the knights sang this tune,

It was sad, a misfortune,

That such a valiant man as he

Should turn away from chivalry.

On every side he was blamed

By knights and squires named,

Till Énide heard the murmur

That her lord desired no longer

To pursue his deeds of arms,

His mind averse to such charms.

She was grieved to know it,

Yet did not dare to show it;

Her lord might take a dim

View if she spoke to him.

So the thing lay hidden,

Until one morning when

They in their bed together

Had delighted one another,

Lip to lip had embraced,

So they true love did taste;

He half-asleep, she wakeful,

Thinking of all the shameful

Words said about her lord,

And all now bandied abroad.

So grieved was she by it all,

She allowed her tears to fall.

Such her chagrin, her sorrow,

She, by chance, spoke also

Words for which, in due course,

She would feel great remorse;

Though she had meant no ill.

She observed her lord until

Viewing his body head to toe,

His form, his honest face also,

Her tears fell so copiously

Over his chest they flowed free.

And she cried: ‘Oh, woe is me,

That I ever left my own country!

What have I here to look for now?

Earth should swallow me, I vow,

When the very best of knights,

Strong and brave in every fight,

The fairest and most courteous

That ever king or baron was,

Has relinquished, and for me,

Every fine deed of chivalry?

Thus, on him, a shame I bring

I’d not have brought for anything.’

Then ‘Unhappy man!’ she said;

Then was silent as the dead.

Érec, though dozing there,

Half-awake, was yet aware

Of what she had said, and he

Marvelling her tears to see,

How she wept, spoke to her,

Spoke and sought an answer:

‘Tell me my sweet friend, my dear,

Why weep in this manner here!

Why now such grief and sorrow?

Surely it is my desire to know.

My sweet friend, come tell me,

Take care, hide naught from me.

Why did you say, “unhappy man”?

You said it of me, I understand.

I heard clearly the words you said.’

Then was Énide discomforted,

Most fearful, much dismayed.

‘Sir,’ she answers, ‘I am afraid

I know nothing of what you say.’

‘Lady, what are you hiding, pray?

Concealment is idle,’ he replies,

‘Tears are gleaming in your eyes,

Will you pretend you wept idly?

Though half-asleep, I stirred me,

And thus I have heard everything’

‘Oh, fair sire, you heard nothing,

I think perhaps it was a dream.’

‘Now you’re lying it would seem,

I hear the deceit in what you say,

But you’ll repent of it this day,

If you conceal the truth from me.’

‘Sire, you torment me so, I see

I must tell you the truth entire,

Hiding nothing, as you desire,

Yet it will trouble you I know.

Throughout the land men go,

The dark, the blonde, the tawny,

Saying how great the pity

That you renounce chivalry;

Your fame suffering equally.

They used to say, one and all,

In this world none could recall

A finer or more gallant knight;

There was no equal in might.

Now they go mocking at you, all,

Young and old, great and small,

Calling you recreant, plain coward,

Think you not it grieves me hard,

When I hear you slandered there?

It grieves me greatly everywhere

And it grieves me all the more

That all this they blame me for;

Yes they put all the blame on me,

Saying the reason’s plain to see,

That I so trap you and enslave

That all your merit is decayed,

Seeking company in none but me.

Another course you must seek.

So you may now erase this stain,

And thus your former name regain;

For I have heard too much of this,

Yet dared not say aught was amiss.

Often when I think on it, you see,

My anguish forces tears from me.

Such chagrin I felt but now,

I could not help but speak aloud,

And there I said: ‘Unhappy man!’

‘Lady,’ he said, ‘I understand,

You and they are right, and so,

Go dress yourself for the road,

Be ready to ride straight away!

Rise now, and dress you may

In your finest robe as yet.

And order your saddle set

There, on your finest palfrey!’

Now rose Énide, all fearfully,

Very sad and pensive too,

Reproaching herself as a fool

For the words she’d said, afraid

She must lie in the bed she’d made.

‘Ah,’ she cried, ‘my evil folly!

For now I was but too happy,

I lacked not a single thing,

God! Why did I risk everything,

Speaking to him in such a way?

God! Did he not love me alway?

In faith, alas, he loved too well.

And now in exile I must dwell!

But of this I have greater grief,

No sight of him will bring relief,

Who loved me in such a manner

That none other he held as dear.

The finest man that ever was born

Held all others in such scorn

He looked only towards me.

I lacked for nothing equally;

Then did I live most happily,

But then my pride stirred in me,

And of my pride I suffer now

That I did such words allow

It is right I suffer, I don’t deny:

None knows the good till the ill they try.’

So the lady sighed with distress,

While she was swiftly dressed

In the finest of robes, as we recall,

Yet nothing pleases her at all,

But simply adds to her chagrin.

Then she has her handmaiden,

Summon her squire, and she,

Bids him saddle her fine palfrey,

Born of northern stock, a mount

Finer than those of king or count.

As soon as her command is given

The squire runs to do as bidden,

Quickly saddles the dapple grey.

Érec calls his squire straight away

Orders him to bring his armour,

And with armour his body cover.

Then to a tower room he was led

A Limoges tapestry was spread

Before him there on the ground

And when the squire had found

The armour as commanded, he

Set it down on the tapestry.

Now Érec took his seat opposite,

A leopard woven where he did sit,

Clear on that tapestry portrayed,

And he prepared to be arrayed:

First he laced up his greaves,

Of polished steel their leaves,

Next he donned a coat of mail,

So finely made it could not fail.

This hauberk was so richly plied

That neither outward nor inside,

Was there iron to forge a needle,

Nor could aught rust the metal,

For all was wrought of silver,

Of close triple-weave all over;

And it was formed so subtly,

That I can swear most certainly

No man wearing it complete

Was troubled by it in the least:

No more a silken jacket hurt,

When worn atop an undershirt.

Every squire and every knight

Began to question at this sight,

Why Érec should his armour don,

But none dared ask why it was on.

When he was in his mail-coat,

A helmet with a band of gold,

Brighter than a glass, the said

Squire now laced upon his head.

Then he donned his sword, ordering

That they saddle for him and bring,

His bay-steed, reared in Gascony.

Then calling to a valet, said he:

‘Valet, run to my lady’s bower,

To the chamber beside the tower,

Which is my wife’s room, and say

She is causing me much delay.’

She is taking too long to dress!

The need for haste on her impress,

For I am waiting here to mount.’

The valet goes, to render account,

Finds her ready, in tears and grief,

And addresses her immediately:

‘Lady, why do you thus delay?

My lord is keen to be on his way,

He has his full armour on,

And would already be gone

Had you been ready to proceed.’

She marvelled at her sire indeed,

Wondering what was his design.

But of this she showed no sign,

Wisely choosing to appear

At her happiest, as she drew near.

She found him midst the courtyard,

Upon her King Lac followed hard.

The knights came too, as I am told.

There is neither young nor old

That fails to demand and know

If any of them might ride also;

Each himself offers and presents,

But he swore it was not his intent

To take with him any companion

Except his wife, and save her none;

For, as for others, they went alone.

The king, when this was known,

Said: ‘Fair son, what do you there?

You must apprise me of this affair,

You should hide nothing from me.

Where do you go, to what country?

You wish it seems on no account

To have knight or squire go mount

And solace you with their company.

If you’ve undertaken to meet, you see,

In single combat with some knight,

Nevertheless you should of right

Take men to ride escort with you,

Many a knight and squire on view,

Both wealth and lordship showing.

For the son of a king, that is fitting.

Fair son, load the packhorses now,

And, as companions, then allow

Thirty or forty knights or more;

Of gold and silver carry a store,

Whatever a nobleman may need.’

Then Érec answered as he decreed,

And told him all he had planned

For the journey he had on hand.

‘Sire,’ he said, ‘it must be so.

I take but one mount when I go,

Nor have I need of gold or silver,

Nor of squires or knights either;

Nor do I wish for company

Save my wife to go with me.

But I pray you, whate’er may pass,

Should she return, and I die alas,

That you love her, hold her dear,

For love of me, this is my prayer,

And grant her half of all your land,

With no contention from any man,

As long as she lives, as her share.’

The king, on hearing his prayer,

Said: ‘I so promise, my fair son,

Yet it grieves me you go alone

Without company, all the day,

You’d not do so if I had my way.’

‘Sire, it must be so, thus we two

Will go; to God I commend you.

But keep my companions in mind,

For them mounts and armour find,

And whatever a knight may need.’

The king could not keep, indeed,

From tears at parting from his son.

The people round him wept as one:

The ladies and the knights weeping,

Shedding tears and him bemoaning.

There were none that did not grieve:

Many swooned, as you may believe;

Weeping kissed him, and embraced;

With sorrow they were almost dazed.

I doubt they could have wept more,

If he’d been dead or wounded sore.

Then Érec said, to ease their sorrow:

‘My lords, why are you grieving so?

I’m neither imprisoned nor in pain,

From this grief you’ve naught to gain.

Though I go today, I’ll return to you,

If it pleases God and I can so do.

I’ll commend you, one and all, also

To God, if you give me leave to go:

For far too long you keep me here.

I am sorry to see you shed a tear,

It brings me great distress and pain.’

Each commends each to God again.

Lines 2765-2924 Érec defeats the three robbers

AMIDST great sorrow, are they gone,

With Érec leading his wife along,

Knowing not where, but at a venture.

‘Come, ride,’ says he, ‘and be sure

Not to be so rash as to speak to me

Of anything you may chance to see:

Say nothing to me; be not heard.

Oh, take care never to say a word,

Unless a word to you I have said,

Now with confidence, ride ahead,

And swiftly for we must be gone.’

‘Sire, she said, ‘it shall be done.’

She rode ahead and held her peace.

Both of them travelled silently;

But Énide was troubled at heart,

And within herself grieved apart,

Soft and low, so he might not hear.

‘Alas,’ she said, ‘to such joy I fear

Has God raised and exalted me,

He casts me down as suddenly;

Fortune, I thought to command,

Now silently withdraws her hand.

And alas, I mind it all the more,

That I dare not speak to my lord.

For I am distressed and mortified

That he will not ride at my side.

He has turned against me, I see,

Since he declines to speak to me.

And I myself am not so daring

As even to seek to look at him.’

While she was lamenting deeply,

A knight who lived by robbery

Appeared from among the trees.

With him were two accomplices,

And all three armed in every way;

They coveted the dappled grey

That mount Énide was riding.

‘Friends,’ cried he, ‘good tidings,’

Addressing his two companions,

‘We are nothing but rapscallions

And are marvellously unlucky

If this haul we take proves puny.

Here comes a lady wondrous fair;

Married or not, that’s her affair,

But very richly is she dressed.

And the palfrey and that harness,

And the saddle and the trappings

Worth easily a thousand shillings.

The palfrey I covet, I confess,

And you may have all the rest!

I desire no more for my share.

That knight who follows there

Shall not lead the lady away,

God save me, I’ll see him pay;

Such a thrust I mean to deal him.

For was I not the first to see him?

Thus it must be my right as well,

Now to challenge him to battle.’

They consent, he takes the field,

Crouched low behind his shield,

While the others remain behind.

Twas use and custom then, I find,

That two knights may not together

Join in attack against one other;

Thus if they had combined jointly,

It would have seemed pure treachery.

Énide had seen the robber knight,

And felt great fear at the sight,

‘God,’ she cried, ‘must I be dumb?

My lord will be taken or succumb;

Since they are three and he’s alone,

Tis no fair conduct, and unknown,

For one man to contend with three.

He’ll strike now advantageously,

For my lord has not taken guard.

God, shall I prove now such a coward

As not to dare say a single thing?

I’ll not be a coward for anything;

I will speak to him without fail.’

Then she turned and did him hail,

Saying: ‘Fair sire, do you not see?

There come riding knights three,

Who will surely work you harm.

Their coming fills me with alarm.’

‘What,’ cried Érec, ‘do you speak?

Do you think me a fool and weak!

You must surely be more than bold

To scorn what you have been told,

My command and my prohibition.

On this occasion you are forgiven;

But if you trespass a further time

You’ll obtain no pardon of mine.’

Then, adjusting shield and lance,

Towards the robber he advanced,

Who challenged him, in an instant;

But Érec, hearing, remained defiant.

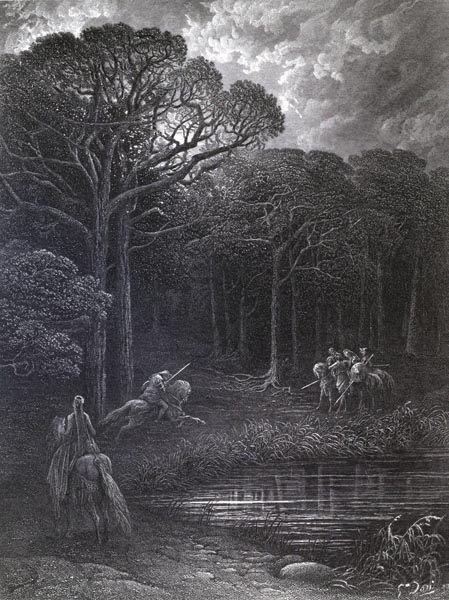

‘Fair sire, do you not see? There come riding knights three’

Enid (p82, 1868) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892) and Gustave Doré (1832-1883)

The Internet Archive

Both gave spur, and clashed together,

Their lances pointing at each other;

The knight failed to strike his man,

While Érec, whose was the better plan,

Dealt the robber a world of harm;

He aimed at the other’s shield arm,

Splitting the knight’s shield in two,

Piercing his chest through and through,

Nor was the chain-mail any defence;

He thrust the steel point of the lance

A foot and a half deep in his body;

Retreating, drew it forth completely,

The robber fell, and die he would,

For the steel had drunk of his blood.

But then a second knight advanced,

His companion staying at a distance,

He rode towards Érec, threateningly.

But Érec, grasping his shield firmly,

Attacked him, and put him to the test:

The knight held his before his breast;

They struck against the emblems there,

The knight’s lance shattered in the air,

And into two separate pieces split.

Upon the breast Érec’s weapon hit;

He drove that lance a quarter deep.

The knight no other harm could reap:

Érec, knocking him from his horse,

Towards the third knight set a course.

When the latter saw Érec advance,

His own escape he swiftly planned

Fearful, not daring to await him,

He fled to the woods to evade him.

But his flight did him little good,

Érec followed, seeking his blood:

Cried: ‘Vassal, vassal, turn around,

And prepare to defend your ground,

Lest I should kill you as you flee!

Flight is in vain, as you can see.’

But the robber cares not to return;

To fly the field is his sole concern.

Érec follows, forcing him to yield,

Striking him on his painted shield,

Driving him into the earth full hard.

All three may Érec now disregard:

The first is dead, the second hurt,

And he has just unhorsed the third,

Forcing him swiftly from his steed.

He seizes the mounts of all three,

Tying them by the reins together:

Each from each in colour differ,

The first like milk shows pure white,

The second is fine, and black as night,

While the third is a dappled grey.

Back to the road Érec took his way,

Where Énide awaited his return.

He made the horses her concern,

He bade her drive them on ahead,

Warned her to heed what he said,

That she must not appear so bold,

As to let one single word unfold,

Save he gave her leave to do so.

She said: ‘I’ll not a word bestow,

Fair sir, if that is your solemn wish.’

They ride on, she holds her peace.

Lines 2925-3085 Érec defeats the five knights

BARELY a league had they gone

When before them, riding along

In a vale, were five knights, all

Of them with lances levelled,

Their shields up, and their bright

Helms on head, and enlaced tight.

They were all after plunder too.

Énide, approaching, they view,

Leading on those three horses,

And Érec after on his courser.

As soon as they both came in sight,

The five agreed what each knight

Should receive as his fair share,

As if they’d already seized the pair.

Covetousness is an evil thing;

Yet it gained them not a thing,

For they met with a stern defence.

Much of a fool’s aims are nonsense,

Many a man fails of his intent:

And so it occurred in this attempt.

One declared he would possess

The lady or die, nothing less;

Another said the dappled grey

Should his own share defray

Of what was won in the attack.

The third said he’d take the black.

‘And I the white,’ cried the fourth.

The fifth, not shy in holding forth,

Claimed that he would seize indeed

The knight’s armour and his steed.

In single combat he would conquer,

And would be the first to venture,

If they would only grant him leave;

Which they willingly agreed.

So they part, he rides forward;

On his fine and agile courser.

Érec saw him, yet he feigned,

Not to, and as yet disdained

To take guard. But when Énide

Saw him her heart beat indeed,

With dread and deep dismay.

‘Alas,’ she said ‘I may not say

A single word, what shall I do?

My lord truly warned me too,

Swore to punish me severely,

If a single word escapes me.

But if my lord’s life were over

No comfort might I discover:

I’d be mistreated, death my lot.

God! My lord sees them not!

Fool that I am, why hesitate?

I am too chary, the risk great,

In granting speech no room.

I well know those that come

Some vile wickedness do seek.

But Lord! How can I speak?

He’ll slay me. Ah, let him so!

To warn him I cannot say no.’

Then she called softly: ‘Sire!’

‘What,’ he said, ‘is your desire?’

‘Sire, your mercy! I am afeared,

Five knights but now appeared

From that thicket, to my dismay.

Having seen them I have to say

They seem ready to attack you.

Four of them wait there ‘tis true,

But the fifth knight comes on,

As fast as his courser can run;

I’m fearful of what he may do.

The other four await their cue,

But they remain not far away;

And will aid him if they may.

Érec replied: ‘You thought ill

In disobeying my clear will,

A thing I had forbidden you.

Nevertheless I surely knew

You hold me in low esteem.

Your services go awry, I deem,

For I owe you no thanks for this,

Angry your tongue runs amiss;

I have told you, and do so again,

Once more my pardon you obtain,

But another time have a care,

Not to turn to watch me there;

You would be foolish so to do.

For a third speech you will rue.’

Then he spurred over the field,

Seeking to make the other yield.

They moved to attack one another.

Érec thrust so fiercely at the other

His shield flew, the neck uncovered,

And Érec the collar bone shattered;

The stirrup breaks, he falls, in pain,

Without the power to rise again;

For he is so wounded and battered;

One of the other four now appears,

And they attack each other fiercely.

Érec, with no great difficulty,

Thrusting his well-forged steel in

Pierces the throat beneath the chin,

Slicing through arteries and bone,

Beyond the neck the blade has flown.

See the hot blood crimson flow

Down on both sides from the blow,

The heart fails, and the spirit flies.

A third knight now met his eyes,

Advancing across the nearby ford,

From his steed the water poured.

Érec gave spur and met the knight

Before he had left the water quite;

Striking at him so hard, withal,

That both horse and rider fall.

The steed falls upon his master,

So the weight holds him under;

The horse seals his fate complete

Then struggles to regain its feet;

Thus has Érec conquered three.

The others take council, and flee,

Thinking they might outpace him,

Both unwilling now to face him;

They gallop along the river side.

Érec follows them as they ride,

Till he strikes one on the spine;

Over the saddle-blow he inclines.

All Érec’s strength was in the blow,

And the lance shattered on his foe.

So that he fell head foremost there.

Érec pays him dearly for his share

In breaking the lance, there beneath,

Drawing his sword from its sheath:

The knight in folly reared up again,

Érec dealt him three strokes plain,

So that his steel sword drank deeply.

Slicing the shoulder from the body,

Such that it toppled to the ground.

Then sword drawn, at a bound,

He attacked the last who swiftly fled,

Leaving the others wounded or dead.

Finding Érec takes up the chase,

He is so afraid he dare not face

The knight, but cannot turn aside;

So he is forced to forgo his ride,

Not trusting in his mount that day.

His shield and lance he hurls away,

Slips from his steed to the ground.

Though Érec no longer felt bound

To pursue the knight, now on foot,

He yet seized the lance by the butt:

Not wishing to leave it lying there,

Given his own was beyond repair.

He took the lance, and rode away,

With the horses taken in that affray:

All five he seizes, a pleasant haul.

Énide is at pains to lead them all:

He hands her the five and three,

Tells her to ride along swiftly,

And keep from speaking a word,

Lest trouble and evil be incurred;

With nary a word does she reply,

Nor does she even utter a sigh,

Leading the horses on, all eight.

Lines 3086-3208 Érec and Énide meet a squire and reach a town

THEY rode along till it was late,

Without reaching town or shelter,

And at nightfall they took cover

In a near meadow, beneath a tree.

Érec bids his lady sleep while he

Undertakes to keep the watch.

She replies that she will not,

It is not right, should not be so;

He must sleep who needs it though.

Érec hears and is pleased to yield.

Under his head he sets his shield,

While his lady her cloak does put

Over her lord from head to foot.

He sleeps, she keeps watch in lieu,

Stays awake the whole night through,

Holding those horses’ reins tight,

In her hands, till clear daylight.

And much she reproached herself,

Ashamed of those words that fell

From her lips, for acting badly,

Having been treated more kindly

Than she felt she deserved by right.

‘Alas,’ said she, ‘revealed tonight,

Is all my pride and presumption!

I should know, without question,

There is no knight who is better

Than my lord, he’s like no other.

I knew so, but know better now,

For my eyes have witnessed how

He has defeated three then five.

A plague on my tongue for I’ve

Spoken with outrageous pride,

And thus of shame almost died!’

So she grieved the night through

Till dawn brought the day anew.

Érec rose with the dawn amain,

And they took to the road again,

She in front and he behind her.

At noon they see a squire appear,

Before them in a little valley.

And with him are two lackeys

Bearing along bread and wine,

And good cheese, rich and fine,

To the fields of Count Galoain,

For his haymakers in the plain.

The squire was awake, indeed,

For seeing Eric and Énide

Coming from the woods behind,

It immediately sprang to mind

They must have sojourned there,

No food or water for their share,

Since that way, for many an hour,

Neither castle, town nor tower

Stood, nor stronghold, nor abbey,

Hospice, nor place of sanctuary.

So setting an honest aim in play

He turned his steps their way,

Saluting them politely and then

Said: ‘Sir, I believe it is plain

That you have spent the night

In those woods, until daylight,

Sleepless, thirsting and unfed.

I offer some of this white bread,

If you to eat of such are fain.

I say it not in hopes of gain;

For I do request naught of you,

The bread is of good grain too,

And I’ve good wine and cheese,

Fine jugs, and a cloth to please.

If you would like to eat there,

You need not seek elsewhere.

Under this beech, on green turf,

Lay your armour on the earth.

And rest yourself a while here.

Dismount, I say, without fear.’

Érec set foot on the ground

Saying: ‘A fair friend found!

I will eat, and my thanks to you,

Without seeking to ride anew.’

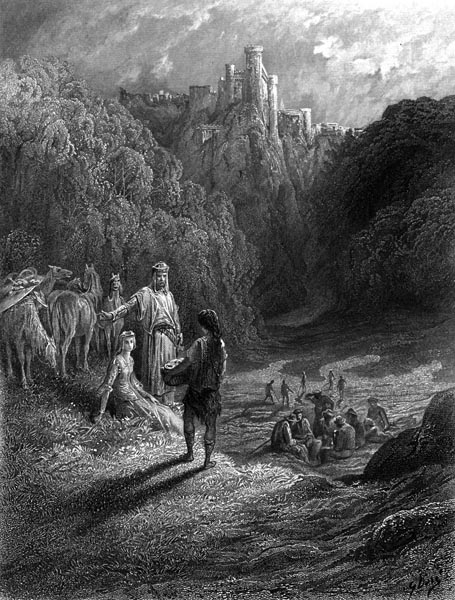

‘Under this beech, on green turf, lay your armour on the earth’

Enid (p91, 1868) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892) and Gustave Doré (1832-1883)

The Internet Archive

The squire, well-bred of course,

Helped the lady from her horse

And the lads accompanying him

Tethered their mounts for them.

Then they are seated in the shade.

The squire Érec’s helm now laid

On the grass, so he might unlace

The ventail from before his face.

The tablecloth then he spread,

Before them, on the grassy bed;

He handed them bread and wine,

Served the cheese, sliced it fine.

Hungry, they ate, and drank until

Of the wine they’d had their fill.

The squire served them readily,

With every care that might be.

Having drunk and eaten enough,

Érec proved kind and generous:

‘Friend,’ said he, ‘in gratitude,

A horse of mine I give to you.

Take the one you like best of all;

And if it prove not too much trouble,

Return to the town that lies ahead,

And find me good board and bed.’

The squire then replied that he,

Would do Érec’s will, right gladly.

So of the horses he made assay,

Choosing with thanks the dapple grey,

For that seemed best. He sprang up

Mounting then by the left stirrup,

And leaving them both behind

Rode swiftly to the town to find

And reserve fine lodgings there.

Behold, to them he again repairs;

‘Now, mount sir, swiftly,’ says he,

You’ll have good lodging presently.

Érec mounted, and his lady after;

The town being not much farther,

To their lodgings soon they came.

They were welcomed to the same,

By their new host, whose pleasure,

It was to meet, and in full measure,

All their wishes, and with goodwill,

And all delight, their needs fulfil.

Lines 3209-3458 The Count desires Énide: she deceives him

WHEN the squire has done them all

The honour he can, then to their stall

He would lead their horses; mounts,

Passes a window-room, the Count’s,

To reach the stables, as he desires.

The Count and three other squires

Are leaning from the window there.

The Count seeing his squire appear,

And mounted on the dapple grey,

Asks of him: ‘Who owns it, pray?’

The squire replied that it was his.

The Count marvelled much at this.

‘How is this?’ he said, ‘Do tell me.’

‘A knight whom I esteem greatly,

Sire,’ he said, ‘gave me the palfrey,

I’ve brought him to town with me,

Found him lodgings for the night.

And he is a most courteous knight,

The handsomest I have ever seen.

Upon my oath indeed I ween.

I could not convey half of how

Handsome he is to you, I avow.

The Count asked him in reply:

‘He cannot be more so than I?’

‘By my faith, Sire,’ said the squire,

‘You are as fine as one may desire,

There is no knight in this country,

No noble born in your territory,

Whom you do not in looks excel;

But this knight, I say, looks well;

He’d outdo yourself, I tell no tale,

If he were not, beneath his mail,

Bruised and sore, black and blue.

In those woods did battle ensue,

He fought with eight knights alone,

And took their mounts for his own.

And with him there rides a lady,

So fair that no other, it may be,

Is even half as lovely as she is.’

When the Count heard of this,

His pride prompted him to see

Whether it were truth or falsity.

‘I never heard of such’, said he,

‘Lead me then to this hostelry;

For certain, I desire to know

Whether you lie or it is so.’

He replied: ‘Sire, willingly,

Here lies the way, follow me,

The lodgings are not far away.’

Said the Count: ‘I’ll brook no delay’.

From his window-room, the Count

Descended, as did from his mount

The squire, so the Count might ride;

Then ran on, to Érec and his bride,

To tell them of the Count’s visit.

Érec’s lodgings were of great merit,

The kind that a nobleman prefers.

There were a great host of tapers

And fine candles spaced around.

Three companions only, they found,

Attended the Count and no more.

Érec rose now to greet the four,

Being a man of gracious manner,

Saying: ‘My lord, be welcome here!’

The Count in like terms replied.

Then they sat down side by side,

On a couch that was soft and white,

So to converse, the Count and knight.

The Count offers, states his intent,

Begging him, pray, to give consent

To his providing for all they need;

But Érec does not deign to accede,

Saying he has much coin to hand;

Needs naught the Count may command.

They talk awhile of many a thing,

But the Count restlessly viewing

All, and glancing here and there,

Casts his eyes on the lady fair.

Seeing her beauty he is caught,

On her he fixes all his thought,

Gazes at her, as best he might;

He covets her, she does so delight

That he is in love with her beauty.

He asks permission, most slyly,

Of Érec to converse with her.

‘May I ask a favour, dear sir,

If it be not displeasing to you,

Of courtesy, and for pleasure too,

I would sit beside your lady.

Out of kindness I came to see

Both, you must no harm expect:

I wish to offer, with all respect,

Whatever service I might pay her.

Know, I would obey her pleasure,

For the love you inspire in me.’

Érec saw no cause for jealousy,

Suspecting no treachery or ill.

‘Sir, ‘he said, ‘such is my will.

You may sit and speak together.

Do not think it displeases, rather,

My permission I freely grant you.’

The lady was sitting about two

Lance-lengths away from them;

So, there, the Count then came;

Sat on a low stool at her side.

The lady turned to him beside,

She being wise and courteous.

‘Ah,’ said he, ‘It grieves me thus

To see you in such humble state!

My sadness and distress is great.

Yet, if you but believe me, you

May have honour and riches too,

Great advantage would be yours.

To such beauty indeed of course

Are honour and distinction due.

My lady, I would wish to see you

The mistress of all I possess.

When, out of love, I make request,

You ought not to disdain my suit;

Your lord I know beyond dispute

Does not love and prize you so.

A worthy lord you shall know

If you remain with me, my dear.’

‘Sir, all this is nothing, I fear!

For better I had not been born,

Or been burnt on a pile of thorn

And my ashes scattered abroad,

Than ever I was false to my lord,’

Said Énide, ‘for it cannot be,

That I should think treachery

Towards my lord, or any ill.

You would err toward me still,

If you insisted on such a thing.

I’ll not behave so for anything.’

But now the Count waxed angry.

‘So, you do not deign to love me,

Lady,’ said he, ‘Your pride is great.

You will not deign to capitulate

To flattery, nor prayers, you say.

The more one begs and flatters today,

The more a woman’s pride grows;

Insult and wrong her, I suppose,

And she’ll prove more tractable.

I swear if you are not pliable,

If you will not obey my will,

I will have my swordsmen kill

Your lord, now, without a fight,

Whether that be wrong or right,

And here, before your very eyes.’

‘Ah no, my lord,’ Énide cries,

‘Seek to act more honourably;

You would work vile treachery,

Should his death here ensue.

Restrain yourself, I beg of you;

I will do your pleasure, hear me.

As your own you may take me:

Since I am yours, and wish it so.

My words not from pride did flow,

But I sought, and would prove,

Whether you indeed might love

My very self with a true heart.

But I would not, for any part,

Wish you to commit a treason.

My lord has not a single reason

To mistrust you, so that, if you

Slay him, treason you would do,

And I would be blamed entirely.

They would say in all this country

That it was done with my consent.

Go rest yourself then for the present;

In the morning my lord will rise,

And his harm you may devise

Without blame or reproach, you see.’

Her thoughts and words do not agree.

‘Sire,’ she cries, ‘believe me now,

Do not thus furrow your brow,

But send here, in the dawn light,

Your squires and your knights

To carry me away by force:

He will defend me, in due course;

He’s a proud and courageous man.

Then by intent, but as if unplanned,

Have him seized and treated ill,

Or even beheaded if you will.

I’ve led this manner of life too long,

I like not to trail, in this way, along

Behind my lord. I would no longer;

With you I would rather linger;

In your bed, naked to naked go.

Since this is the course we follow,

Of my love you may rest assured.’

The Count replied: ‘Lady, for sure,

You were born in a propitious hour:

And you will be held in great honour.’

‘Sire,’ she replied: ‘I so believe;

Yet your word I would receive,

That you will ever hold me dear,

Or I should not trust you, I fear.’

Glad and joyful the Count replied,

‘Here I will pledge that, on my side,

Faithfully, as a count, my lady,

I will do all you wish, entirely;

And you need have no fear of that.

All that you wish for you shall have.’

Now she has won from him his word

Of little worth, though little she cared

Except as a way to save her lord.

She knows how to snare with words

Any fool, when she gives it thought;

Better that he with lies were caught

Than that her lord should be slain.

The Count stands at her side again,

Commends her to God a hundredfold;

Small value however shall it hold

The pledge to him that she has made.

Érec hears nothing of what they say,

That they are speaking of his death,

But God will aid his every breath,

As I believe He will so do now.

Érec is in great danger, I allow,

Knows not that he must beware,

That the Count plots evil there,

Thinks to steal his wife away,

And Érec, all defenceless, slay.

The Count slyly takes his leave:

‘To God I commend you,’ says he.

‘So do I you, Sir,’ Érec replies,

Taking leave of him likewise.

The night was already part over.

There, in a secluded chamber,

Two beds were set on the ground.

On one of them Érec lay down,

Énide retired to the other bed,

Filled with anxiety and dread.

She slept not at all that night,

Keeping good watch till daylight,

For she knows the Count to be,

As it has been given her to see,

A man filled with wickedness.

And knows too that if in duress

He holds her lord, he will not fail

To do him harm, and her assail;

Surely he will slay her knight,

For whom she wakes this night.

Distressed she guards her man;

But before dawn, if she but can

Bring it about, and he believe,

They may be full ready to leave.

Lines 3459-3662 Érec escapes and defeats the Count, who recants

EREC slumbered long and deep,

Securely, all that night, in sleep,

Until the dawn light drew near.

Then Énide realised, in fear,

That she must delay no longer.

Her heart toward him was tender,

Like a true and loyal wife,

Free of deceit, as was her life.

She rose, made ready to ride abroad,

Then she went to wake her lord:

‘Ah, Sire,’ she cried, ‘forgive me!’

You must arise now, instantly,

For you are beset by treachery,

Though you of any guilt are free.

The Count is a proven traitor,

And if he comes upon you here

You will not escape this place,

He’ll slay you before my face.

He desires me, and thus hates you,

But if God pleases, who sees the true,

You will not now be taken or slain.

Last night he sought your life to gain,

But I this Count truly deceived:

I’d wed and love him he believed.

Soon you will see him reappear:

He wishes to seize and keep me here,

And slay you if he finds you too.’

Now is it proven to Érec how true

His wife is and how loyal a lady.

‘Wife,’ he cried, ‘run, instantly,

Have our mounts saddled, then away

And go summon our host, and say

That he must his presence afford:

For treason is but now abroad.’

Soon the horses are made ready,

And the host summoned swiftly.

Érec is now armed and dressed.

The host has run to attend his guest.

‘Sire,’ he cries, ‘why such haste!

Why do you your sleep thus waste,

Surely the night is not yet done?’

Érec replies: he must be gone,

The road is long, long the journey,

And therefore he has made all ready,

It being for some time in his thought.

‘Sir,’ he added, ‘you’ve not yet brought

Me any account of my expenses:

You’ve shown me honour and kindness,

And that redounds to your great merit,

The seven horses will settle the debt,

The mounts I brought along with me.

Don’t disdain them, take them of me!

I could not increase my gift further,

Not even by adding a single halter.’

His host, delighted with every steed,

Bowed low, to his very feet indeed,

Expressing his deepest gratitude.

Then Érec mounted, and so issued

His farewells, and was on his way.

While often to Énide, he did say,

That if anything she should see

She should not thus, so daringly,

Speak to him of it, but be silent.

Meanwhile, possessed of ill intent,

A hundred armed knights entry made

To the lodgings, and were dismayed

To find that Érec was no more there.

Thus the Count found that the fair

Lady had tricked him completely.

Their horses’ hoof prints they see,

And all at once follow the trail.

The Count against Érec doth rail,

And declares that if he finds him,

Nothing indeed will restrain him

From beheading him there and then.

‘A curse on whoever slows again,’

He cries, ‘or fails to spur instead.

Whoever shall bring me the head

Of this knight, whom I hate, I say,

Will have served me well this day.’

Then they drove onward swiftly

All filled with a deep hostility

Towards a man they had never

Seen, nor had he hurt them ever.

They rode on till they saw him,

Even at the woodland margin,

Before he was lost in the trees.

Not one of them but in rivalry

Charges onwards; Énide hears

The sound as the force appears,

The noise of horses and arms,

Filling the vale, to her alarm.

Now Énide could not, on seeing

Them, stop herself from speaking.

‘Alas, Sire,’ she cried, ‘Alas!

See what a force the Count has

Brought, a very host attacks you!

Sire, ride faster now, till you

And I are hidden by the trees.

I think we can escape with ease,

For they are yet far behind us.

If you continue to amble thus,

Death will prove hard to evade;

Both are not equally arrayed.’

‘Little it is you think of me,

You neglect my orders utterly’

Érec replied. ‘My kind prayers

Cannot restrain you it appears.

But if God is merciful and I

Escape from this, by and by,

You’ll pay dearly for speaking,

Unless I feel more forgiving.’

Then Érec promptly turning

Sees the Seneschal nearing,

On a steed swift and strong.

Before them all he rides on

Four crossbow lengths away.

Érec was armed for the fray,

And thus well-set to fight.

He assesses the foe’s might,

And sees a full hundred there.

Then the Seneschal prepares

To attack him, swift he rides.

Soon together they collide,

Striking each other’s shield

With blows from their steel,

Érec with his trenchant blade

Does the other’s guard invade,

Whose shield and coat of mail

No more than blue silk doth avail.

Now the Count spurs to the fight,

Who was a fine and sturdy knight,

So the tale goes, but the Count

Had been ill-advised to mount

With only his shield and lance,

Seeing his prowess as his defence,

Thinking he needs naught else.

He shows his bravery, himself

Racing ahead, and at a distance,

A dozen rods or so in advance.

When Érec saw him riding clear

He turned; the Count, lacking fear,

Charged, and they met violently.

The Count struck Érec so fiercely,

With such force against his chest,

That if he had not been well-set

He would yet have been unhorsed.

The wood of his shield was forced

And split, the lance pierced through.

But Érec’s defences were proof

Against all, saving him from hurt

Without harm to his mail shirt.

The Count was strong, his lance broke:

Then Érec dealt him such a stroke

On his shield, all painted yellow,

More than a yard into the fellow

Driving his lance, so deep indeed

The Count toppled from his steed.

Then Érec turned and rode away,

Not wishing to prolong his stay:

Into the forest, straight, he rode,

Spurring his horse along the road.

Now Érec is amongst the trees,

Leaving the field to his enemies,

Who tend to those who have fallen,

And swear to follow him, and then,

By every solemn oath ensure,

After two or three days, or more,

They will capture him, and slay.

The Count, hearing what they say,

Though he is wounded grievously,

Draws himself up, most carefully,

And opens his eyes a little way.

He sees the ill begun that day,

All the evil wrought, complete:

He asks the knights to retreat,

Saying: ‘My lords, let no soul

Strong or weak, high or low,

Be so rash as to dare advance

A single step, at this instance.

Return now, all, immediately!

I have behaved most villainously:

But of my villainy I now repent.

Courteous, honourable, prudent,

Is that lady who deceived me.

I fell in love so with her beauty,

She so filled me with desire,

To slay her lord did I aspire,

And so by force possess her.

I deserved ill and found no other:

For see how ill has come to me.

What bad faith, what treachery,

How vile I was in my madness!

Never was knight born who less

Deserved it, nor any man better.

He’ll have no harm of me, rather

I’d seek to prevent it now alway.

I demand you return: now obey.’

Back they all went, disconsolate,

Bearing the Seneschal, whom fate

Had dealt his death, upon his shield

Reversed. The Count too from the field

They bore, yet not wounded mortally:

Thus was Érec delivered, as we see.

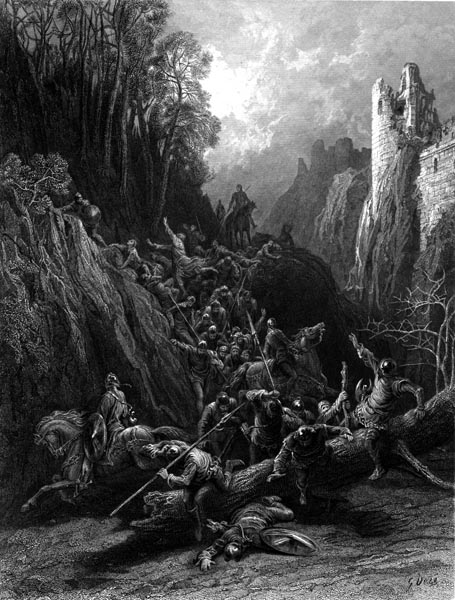

‘Back they all went, disconsolate, bearing the Seneschal’

Enid (p111, 1868) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892) and Gustave Doré (1832-1883)

The Internet Archive

The End of Part II of the Tale of Érec and Énide