Chrétien de Troyes

Cligès

Part III

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2018 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Lines 3621-3748 Fenice is captured by the Duke’s men

- Lines 3749-3816 Cligès completes his defeat of the twelve captors

- Lines 3817-3864 The lovers’ diffidence

- Lines 3865-3914 On love and fear

- Lines 3915-3962 Cligès and Fenice return to the camp

- Lines 3963-4010 Cligès accepts the Duke’s challenge

- Lines 4011-4036 Cligès arms himself as the white knight

- Lines 4037-4094 Battle commences

- Lines 4095-4138 Fenice faints while watching the fight

- Lines 4139-4236 The duke makes peace with Cligès

- Lines 4237-4282 Cligès pleads for leave to visit Britain

- Lines 4283-4574 Fenice reflects on Cligès’ departure

- Lines 4575-4628 Cligès prepares for a tournament at Oxford

- Lines 4629-4726 Cligès fights, anonymously, in his black armour

- Lines 4727-4758 King Arthur has search made for the black knight

- Lines 4759-4950 Cligès, the knight of many colours

- Lines 4951-5040 Cligès is received at King Arthur’s court

- Lines 5041-5114 Cligès reveals his name, is feted, but returns home

- Lines 5115-5156 Cligès reaches Constantinople

- Lines 5157-5280 The lovers converse together

- Lines 5281-5400 Fenice proposes to feign death

- Lines 5401-5456 Fenice involves her nurse Thessala in the plan

- Lines 5457-5554 The sculptor, artist, and mason, named John

Lines 3621-3748 Fenice is captured by the Duke’s men

A spy to the Duke now came

With tidings to delight the same:

‘Sire,’ he said, ‘not one is left

In the Greek camp but is bereft

Of any means for his defence.

The emperor’s daughter I sense

Could be seized from her tent

While the Greeks are all intent

On the wounded, or the fight.

Lend me a hundred knights,

And you will have her today;

For by an ancient hidden way

I’ll lead them there so secretly

That not a man of Germany

Will know of, or encounter, us,

Till the maid from her tent thus

They can seize and lead away,

And not a man to say them nay.’

This filled the Duke with delight,

And more than a hundred knights

He assigned the spy; this company,

Being guided so fortunately,

They seized the maiden in due course,

Without employing brute force,

But easily leading her away.

Far from the tents, on their way,

Twelve were detailed to escort her,

The rest departing not long after,

The twelve accompanying the maid,

While the rest the news relayed

To the Duke of their success.

Since the Duke doth now possess

What he desires, he doth agree

A truce with the Greek enemy,

The truce to last till the next day.

The Duke’s men then rode away,

The Greeks without more ado

Returning to their tents anew.

But Cligès remained behind,

On a hill where none would mind

Him, till there came in sight

The maiden and the twelve knights,

Carrying her away swiftly.

Cligès, in his lust for glory,

Charged them, at a thought;

Their flight is not for naught,

His heart and mind both agree.

So, when he sees them flee,

He spurs after them. But they

Wrongly think that this may

Be the Duke, for, by and by:

‘Reign in a moment,’ they cry,

‘He has parted from the host,

And after us alone doth post.’

Not a man but thinks this so,

All wish to greet him though,

And turn around, one by one.

Meanwhile Cligès had gone

Into a dip between the hills,

And might have lost them still,

If they had not paused a while

Nor ridden back, in single file.

Six now ride to the attack,

Each alone, as they turn back.

The others lead the maiden on

At a slow amble, they are gone,

Or trotting onwards gently;

While the first six spur briskly,

Galloping along the vale,

Till the swiftest came in hail,

And seeing Cligès cried loudly:

‘God save the Duke of Saxony!

My Duke, we now have the lady,

No more the Greeks will she see,

And now her to you we render.’

When this shout, all in error,

Cligès hears, this fellow’s cry,

His heart is much pained thereby.

No wonder then if he is enraged,

Never was wild beast, uncaged,

Whether lion, tiger, leopard,

On seeing its cubs captured

So stirred, angered so fiercely,

Or roused to fight so ardently,

As Cligès, who death doth vow,

Should he abandon his love now.

Better that he die than fail her,

His distress spurs on his anger,

His courage thus mounting higher.

He spurred on the Arab charger

And struck his enemy’s shield

With such force that it did yield;

In truth, so great a blow did deal,

That his foe’s heart felt the steel.

He spurs the Arab charger on

A dozen rods and more is gone,

Strengthened by his encounter,

Until he meets a second comer,

For they approach him singly,

Each man attacking fearlessly.

Thus Cligès fights them, one by one.

And since each meets him alone,

They cannot turn about for aid.

A charge at the second he made,

Who like the first thought to cry

The news that Cligès must die,

And take joy in it, as the other,

But Cligès cares not for his chatter,

Nor does he stop to hear him speak.

Rather he thrusts his lance flesh deep,

So the blood spurts on withdrawal,

Stealing his foe’s speech, life and all.

After these two he meets the third,

Who thinking to find him perturbed,

And give him joy of his own fate,

Spurs his mount against him straight,

But before he can say a single word

Cligès runs his lance, by a third,

Through the centre of his body.

The fourth he strikes such a blow that he,

Is left senseless on the ground.

After the fourth a fifth is downed,

And the sixth after number five;

None strong enough to survive.

He leaves them all silent, mute.

Less afeared of the rest, in pursuit

He presses more fiercely after them,

Leaving behind him six dead men.

Lines 3749-3816 Cligès completes his defeat of the twelve captors

SUCCEEDING in this, the first test,

Cligès rides on to present the rest

With a debt paid in shame and woe,

As with the captive maid they go.

Approaching them he makes assault

As a lean and hungry wolf will vault

All obstacles to reach its prey,

Now he feels fate turned his way,

Where he can show his chivalry

And his bravery openly,

Before one who is his delight.

Now will he die, our brave knight,

Or save her, while she’s equally

Close to dying, of anxiety,

Not knowing he’s so near to her.

An attack Cligès now delivers,

Lance couched, which pleases him,

Striking one foe, then after him

Another, dashing to earth, again,

With a single charge, both of them,

While his ash lance splinters too,

As they, run through and through,

Fall to the ground in such great pain

They lack the will to rise again

And work him any harm or ill.

The other four attack him still,

Enraged they face Cligès together,

But he neither quails nor wavers,

Nor can they bring him to grief.

Swiftly drawing from its sheath

His sword, with sharpened blade,

Against a foe his charge he made,

In order that delight might move,

The one who waited on his love,

Striking with his sword fiercely

Such that he severed from the body

Half the man’s neck, and the head,

His sense of pity now limited.

Fenice who had watched all this,

Had not yet recognised Cligès;

She wished that it might be he,

Yet, such the peril, she could see

That might seem a foolish notion.

Thus she showed her deep devotion,

Feared his death, but sought his honour.

Thus Cligès faces his attackers,

Who fight bravely, nor will yield,

But splinter and hole his shield;

Yet, trying to down him, they fail,

Nor can they pierce his iron mail;

While when Cligès strikes his foe,

Naught remains beneath the blow;

Moving faster than top doth skip

Lashed and driven by the whip,

He leaves all torn and split apart.

Skill, and the love within his heart,

Render him steadfast in the fray:

The men of Saxony, in that melee,

He pressed so hard, all were dead

Or their spirits were almost fled.

To one alone he grants escape,

Showing him mercy, face to face,

Who to the Duke might tell the tale

Of woe, how their attempt did fail.

Lines 3817-3864 The lovers’ diffidence

LEARNING thus of the disaster

The Duke feels great grief and anger.

Cligès with Fenice doth remain,

Love of whom is trouble and pain.

Yet if he does not now confess

His love, he’ll know endless distress,

And she, should she fail to employ

The words that will bring him joy;

For they can grant mutual audience

To the workings of the inner sense,

Yet he fears she may refuse him,

While she would speak all to him,

But dreads lest he may her refuse;

Although their eyes would accuse

Each other of their secret thought,

If of them they had heeded aught.

Their eyes converse at a glance,

But their tongues in this instance

Prove cowards, fearing to speak

Of the love that doth them pique.

And yet if she dare not begin,

(For an innocent, fearful thing

A maid must be, tis no wonder)

Why doth Cligès stand yonder,

Who fought so bravely but now,

Yet once alone with her is cowed?

My God, whence comes his fear,

Of an innocent maid, a mere

Lone girl, timid, weak and mild?

As if our eyes were now beguiled

By the hound that flees the hare;

The fawn that terrifies the bear,

The lamb the wolf, the dove the hawk;

The peasant scorning his pitchfork,

With which he has to earn a living;

The hawk from the pigeon fleeing,

The falcon flying from the heron,

A pike that doth the minnows shun,

The stag behind, and the lion first,

And all things turned to their reverse.

So I feel the desire in me,

To reason on this mystery,

As to why lovers lose all sense,

All their courage held in suspense,

And fail to say what’s in their mind,

Though the perfect time and place they find.

Lines 3865-3914 On love and fear

ALL you, wise in the ways of Love,

Who the manners and forms approve

Of his wide court, most faithfully,

Upholding his laws, most loyally,

Whatever he may inflict on you,

Tell me if aught is known to you

That, born of love, delights us here,

Yet brings not trembling and fear.

If any deny me their assent,

I’ll yet refute their argument;

For unless we tremble in fear,

And sense and memory disappear,

We are seeking to obtain by stealth

What by right is another’s wealth.

A servant who fears not his master

Should never in his employ linger,

Nor seek to labour in his service.

Fear’s wedded to esteem in this:

Lack of esteem means lack of love,

Which deceit doth quickly prove,

By stealing what is not its own.

The servant with fear should groan,

If his master’s service so demands;

And who is under Love’s command

Owns him as his lord and master:

Tis right that he does him honour,

Fears and serves with due reverence,

If he would maintain a true presence

At his court. For Love without fear,

Doth like chill flameless coals appear,

Day without sun, flowerless summer,

A honey-less hive, a frostless winter,

A moonless night, a book sans letters.

And so my logic must all prefer:

If fear doth not direct intention,

Love is hardly worth a mention.

Who would love, must know fear,

Or Love himself will not appear;

But he must fear his love alone,

And for her sake defend his own.

So no wrong did Cligès do,

In fearing his love, tis true.

Even so he’d not have failed

To speak, and thus his love regaled

With fair words of love, outright,

Despite all, and come what might,

If she’d not been his uncle’s wife.

This the wound that plagues his life,

And grieves and pains the more, that he

Dare not utter what he’d speak.

Lines 3915-3962 Cligès and Fenice return to the camp

SO to their own camp they return.

And if to speak of aught they turn

It is to little of great import.

Each mounted on a spirited horse,

They ride to their people swiftly,

Who are lost in sorrow wholly.

The whole host is plunged in grief,

But they are wrong in their belief

Who think that Cligès is dead.

That is the cause of all their dread,

And Fenice’s fate doth them pain,

Thinking never to win her again.

So for him, and for her no less,

The whole host is in great distress.

But the aspect of the whole affair

Must alter once they are there,

And as they reach the camp again,

Then new joy cometh after pain.

Joy returns and sorrow flies,

As all come to feast their eyes,

The whole host quickly gather.

Both the emperors together

On hearing of the glad tidings,

Of Cligès and the maid arriving,

Go out to meet them joyfully.

And each of them can barely

Wait to hear of how Cligès

Has rescued the new empress.

Cligès tells them, and listening

They both marvel at the thing,

Praising his courage and devotion,

But the Duke’s contrary emotion,

Is such that he determines, swears,

To fight with Cligès, if he dares,

The duel to be between the two,

And there to be a condition too,

That if this Cligès wins the fight

The emperor shall proceed aright,

And freely take with him the maid,

While if Cligès he beats or slays,

Who has worked him great injury,

No truce or stay shall there be,

But each shall after do his will.

This the Duke would see fulfilled,

And ensures that his interpreter,

With Greeks and Germans doth confer,

Such that the two emperors know,

He’d wish the contest handled so.

Lines 3963-4010 Cligès accepts the Duke’s challenge

THE interpreter gave his message,

In one and then the other language,

So all might clearly understand.

The whole army took their stand,

Proclaiming God forbid Cligès

Should in such a duel engage:

While the emperors having learned

Of the challenge are concerned.

But Cligès kneels at their feet,

Telling them not to fear defeat,

But that if he had e’er pleased them,

He prays he might fight for them,

As a guerdon, and as his reward.

For if his plea be now ignored,

He cannot aid his uncle further,

Nor serve his cause, nor his honour.

Alis who held his nephew dear,

As he ought, was most sincere

Raising him swiftly by the hand,

Saying: ‘Dear nephew, understand,

It grieves me that you wish this so,

That after joy we attend on sorrow.

That you pleased me I’ll not deny,

Yet it must force from me a sigh

To send one yet so young, thus

Into battle to fight for us.

Yet I know your heart’s so high,

There’s not a thing I can deny,

That you are pleased to demand.

Know, solely at your command

Shall this be done, so go forth,

But if my prayer is of any worth,

You will turn from battle today.’

‘Sire, plead with me no more, I pray,’

Cried Cligès, ‘may God confound me,

If I should win the world before me,

Yet shirk to undertake this feat.

And why then should I further seek

Respite from it, or long delay?’

The emperor then, giving way,

Wept with pity, while Cligès

Wept with joy, at his success.

Many a tear is shed that day,

They ask no respite, or delay;

The Duke’s own messenger goes

Before prime, and doth disclose

That the challenge is accepted

As the Duke himself expected.

Lines 4011-4036 Cligès arms himself as the white knight

THE Duke is quietly confident

That Cligès will ne’er prevent

Death or disaster at his hands;

Armed and ready now he stands.

Cligès, who awaits the fight,

For all that, trusts in his might,

Sure of acquitting himself well.

Arms that may the Duke repel

He asks of the emperor, of right,

And that he dub him now a knight.

The emperor grants him armour;

He takes the gift, battle-eager,

Much desiring to bring it on;

Swiftly all that armour he dons.

Once he is armed, head to toe,

The emperor filled with sorrow,

Girds the sword at Cligès’ side;

The white Arab steed he’ll ride.

Now Cligès mounts, in full armour,

Round his neck, on straps of leather,

He hangs his shield, white ivory,

Not to be shattered easily,

And free of emblem or design.

All his armour white doth shine,

And the harness, and the charger,

All are white as snow, and whiter.

Lines 4037-4094 Battle commences

Cligès and the Duke are mounted.

Each to the other had suggested,

That they should meet half-way,

And their companies should stay

Beside, without sword or lance;

And should this pledge advance

That each of them standing there,

During the space of this affair,

Would no more move, whate’er his wish,

Than he would an eye relinquish.

This agreed, they met together,

Each of them ready and eager

To win the conflict gloriously,

And know the joy of victory.

But before a blow was dealt,

Fenice came there, since she felt,

Concerned to know Cligès’ fate,

For it had seemed to her of late

If he were dead, then she must die;

For no comfort would be nigh

To stop her joining him in death;

Naught without him worth a breath.

With the audience there, all told,

High and low, young and old,

And the guards now all in place,

Each of them his lance doth take,

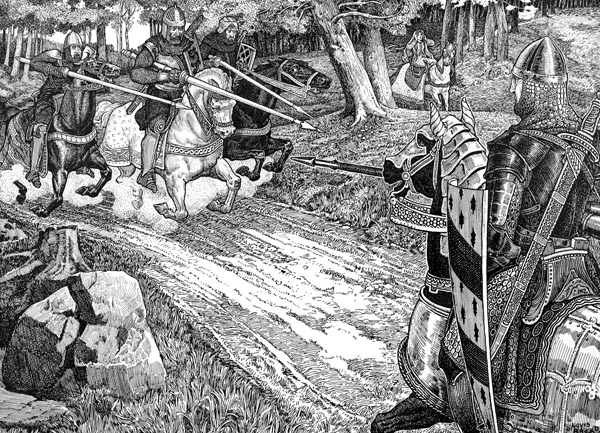

‘And the guards now all in place, Each of them his lance doth take’

Idylls of the King (p32, 1898) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892)

Internet Archive Book Images

And charge, so their lances shatter,

As with force they clash together.

And, unable to keep their seat,

Both fall to the ground beneath.

Yet as neither man was wounded

To their feet they swiftly bounded.

They run at the foe without delay;

While on their helmets they play

Such a tune with their swords,

To the onlookers it affords

The sight of their helms on fire,

The sparks struck flying higher.

For when those swords rebound

Glittering sparks fly, at the sound,

Like those from the smoking steel

When the blacksmith’s anvil peals,

As he beats metal from the furnace.

Both these warriors are generous

In dealing a myriad of blows,

And each intends, as he shows,

To give back what he receives;

The one and the other heaves

Repaying, without count, all

Both interest and capital,

Promptly, and without respite.

But the Duke is troubled quite

Filled with anger and distress

That, in the first assault, Cligès,

Has neither been killed nor yielded.

He deals Cligès a blow, wielded

With such wondrous force, that he

Falls, before him, on his knees.

Lines 4095-4138 Fenice faints while watching the fight

WHEN this fierce blow downed Cligès,

The emperor was much distressed,

No less than if he, in the field,

Were himself behind the shield

Of him to whom it had occurred.

Nor could Fenice prevent a word

Escaping; so dismayed was she,

That she cried out: ‘Saint Marie!’

As loudly as it might be uttered,

But only that one cry was heard,

Before her voice failed her wholly,

And, fainting, she fell awkwardly,

While slightly bruising her face.

Two noblemen helped her apace,

And raised her to her feet, while she

Regained her thoughts completely.

And yet none who saw her guessed

Despite her seeming so distressed,

The reason why she had fainted.

And not a man there blamed her,

But rather they were full of praise,

For each one there thought someday

She might for him feel the same

As Cligès whom her pity claimed;

But as to that they were in error.

When Fenice cried out in terror,

Cligès heard her, and was aware

Of her voice, and its note of care,

For leaping to his feet bravely,

He attacked the Duke strongly,

And so seemingly unafraid

That the Duke was now dismayed.

For now he found him fiercer still,

Strong, agile, keen to show his skill;

More so it seemed than when first

They had met to wage their worst.

Because he now feared his fury,

He cried: ‘Young man, God save me,

I see you prove both bold and true,

And if it were not for my nephew,

Whom I am sworn never to forget,

I could make peace with you yet,

And quit all this dispute with you,

And scorn to trouble you anew.

Lines 4139-4236 The duke makes peace with Cligès

‘DUKE, which path will you choose’,

Cligès cried, ‘must a man not lose

A right of choice he can’t recover?

And must he not choose the lesser

Of two evils with which he’s faced?

When he thought after me to chase,

Your nephew indeed was not wise

And I shall treat yourself likewise,

As I will do now, if I so please,

Unless you agree my terms of peace.’

With Cligès, launched or in defence,

Grown in strength and confidence,

The Duke decides he’d best desist,

Before he lacks strength to resist,

And halt the fight in mid-career,

Before aught worse doth appear,

And he is sent on an evil road.

Nevertheless, he does not show

The bitter truth of this openly:

‘Young man,’ he says, ‘you I see

Are noble, true, full of courage,

Yet still are of quite tender age,

Such that it doth appear to me,

That if I killed or injured thee,

I should gain but small success,

Nor would I wish to confess

To any, expert in chivalry,

That I had battled against thee,

To your honour, and my shame.

But, if honour you would claim,

A mighty honour, all your days,

Twill be that you held me at bay

For two whole rounds in this fight.

Heart and mind now speak aright:

That I end the quarrel is their plea,

And thus no longer fight with thee.’

‘Duke,’ said Cligès, ‘that will not meet

My need; all this you must repeat

Openly, for it must ne’er be said

You granted grace to me instead,

Or that you showed mercy to me.

In the presence of both companies

You must say all you said to me,

If reconciled you’d seek to be.’

The Duke, agreeing, did so record,

And they established their accord.

But, however it might be regarded,

To Cligès all honour was awarded,

And the Greeks were thus delighted.

Yet those of Saxony felt slighted,

Having viewed their lord but now

Wearied quite, with head bowed;

For there was but little doubt

That had he not been worn out,

Peace would ne’er have been won,

And Cligès’ spirit swiftly gone

From out his body, if possible.

The Duke repaired to his citadel,

Sad, downcast, filled with shame,

For none now but must maintain

That he’d been utterly defeated,

Disgraced, and thoroughly worsted.

Those of Saxony, full of shame,

Retreat to Saxony again,

While the Greeks, quickly turn

And to Constantinople return,

In great joy and great delight,

For Cligès, their brave knight,

Has opened the way for them.

No longer now escorting them,

The emperor of Germany,

Takes leave of all the company,

Of Cligès and of his daughter,

Last of Alis, and then close after

His return to his palace follows.

While the Greek emperor goes

On his way, filled with delight.

Cligès, that brave and courteous knight,

Reflects now on his father’s orders;

Of his uncle, the emperor,

He must now request consent

To go to Britain, so present

Himself before him, seeking

To visit his great-uncle, the king,

Whom he would both see and know.

Before the emperor then, he goes

And makes request, submits a plea,

That he be allowed to take leave,

To see his great-uncle in Britain.

He spoke most courteously again,

But his uncle steadfastly denied

Him his request, and thus replied,

When he had listened to his plea:

‘Fair nephew,’ he said, ‘it pains me

That you desire so to depart.

This leave, this request to part,

I never could grant without regret:

It is my pleasure and my wish yet,

That my comrade you should be

And rule the empire, alongside me.’

Lines 4237-4282 Cligès pleads for leave to visit Britain

NOW Cligès is much dismayed

When his uncle reply has made,

To his plea, denying him leave.

‘Sire,’ he says, ‘most dear to me;

Neither wise nor versed in chivalry

Enough am I, that any with me

The work of government should share,

Or the burden of the empire’s care.

I am young, and lack experience.

They put gold to the test, hence

They prove if that metal is fine.

And I now wish to assay mine,

And prove myself by such a test,

There where I may, among the best.

For in Britain, the brave may hone

Themselves on a true whetstone:

If I am brave, by that true test

I too may prove my own prowess.

For in Britain are the noblemen

Of honour and of prowess blent;

And he who honour would gain

In such company should remain.

Honour he’ll have, and will gain

Who their company doth attain.

To travel there I seek your leave,

And if you grant it not, believe,

That if, in denying your consent,

You seek my journey to prevent,

I will depart without your leave.’

‘Fair nephew, I grant you leave,

Seeing indeed from your manner,

That I cannot by force or prayer,

Retain you here, and at my side.

May God grant that you not abide

There, and that you wish to return.

Since my prohibition cannot earn

A change of heart, nor force nor prayer,

Of gold and silver a full measure

I would have you take with you,

And horses for your pleasure too,

I give to you to ride when there.’

On hearing his speech so fair,

Cligès thanked him graciously,

And all that the emperor indeed

Intended, and had granted him,

Was then swiftly brought to him.

Lines 4283-4574 Fenice reflects on Cligès’ departure

Cligès had all that Alis promised;

The companions too that he wished.

And for his use selected too

Four horses of differing hue;

Sorrel, dun, black and white.

But I have passed over quite

Something I should not omit;

For Cligès now thought fit

To ask leave of Fenice, seeking

To place her in God’s safe-keeping.

Once before her, on his knees,

He sheds tears so bitterly,

Robe and tunic are drowned,

His eyes fixed on the ground,

Not daring to raise them higher,

As though he hath conspired

To commit some crime towards her,

And thus from shame doth suffer.

While Fenice, gazing silently,

Timidly and fearfully,

Knows not why he is there.

She speaks with difficulty: ‘Fair,

Friend, rise now, dear brother!

Sit beside me, weep no further,

And tell me all your pleasure.’

‘Lady, what then shall I utter?

I come to ask leave of you so,

Because to Britain I must go.’

‘Tell me then why you believe,

You must come to seek my leave.’

‘Lady, before my father died,

He begged me, with his last sigh,

To obey him, and for my sake,

The journey to Britain undertake,

As soon as I was made a knight.

And since indeed it must be right

Ne’er to ignore such a request,

I must not falter in that quest,

Until I have so journeyed there.

And as Greece is far from where

We are, and if I travel to Greece,

The distance would only increase,

That I must travel to reach Britain,

I should ask your leave for certain,

As one who is yours completely.’

Many a sob and sigh, covertly,

Marked these two lovers’ parting,

But neither was there any hearing,

Nor any sight sharp enough

To know with any certain proof,

That there was truth in the thought

That between the two was aught.

Cligès, despite his pain and grief,

Now seizes the first chance to leave;

He is thoughtful as he sails away,

Alis too, but, of those who stay,

Fenice is the most pensive of all,

To her there seems no end to all

The thoughts with which she’s occupied

Such are her cares multiplied;

And pensive still on reaching Greece.

The honour shown her doth increase,

As their noblest lady and empress;

But her heart rests still with Cligès,

And all her hopes, where’er he be,

And ne’er her heart’s return doth she

Desire, unless he that brings it her

Is dying of the ill that’s killing her;

If he recovers then so will she,

Yet he can never a victim be,

Without her proving one also.

Her illness in her face doth show,

For it is changed, pallid in colour;

From her face, with all its pallor,

Is lost all the fresh, clear, pure

Colour granted her by Nature.

She often weeps, often sighs,

Little the empire doth she prize,

Nor all the honour shown to her.

Cligès, she doth ever remember,

How she saw his face alter,

And the tears, and his pallor.

How he had wept before her,

As if compelled to adore her,

Humbly, simply, on his knees.

All this is pleasant and sweet

To recall and to contemplate.

And then, as a sweet aftertaste,

Instead of spice, on her tongue

She shapes the word that hung

On his lips, that not for all Greece

Would she now have him cease

To use in the way he had, truly,

For she lives on no other dainty,

And nothing else pleases her so.

That word sustains her though,

For it can assuage all her ills.

No other food or beverage will

She, so often, seek and taste;

For when Cligès left in haste,

He said he was hers ‘completely’.

The word is so good that, sweetly,

From the tongue to heart it flows,

Thus she savours it, in repose,

In order to render it more sure.

Nor would she dare to secure

That treasure with another key;

Nor could it be held so closely

In any place but in her heart;

Nor will she let it stand part

From herself, for fear of thieves;

Yet need not fear their deceits,

Nor cry out on birds of prey,

For she possesses it alway;

And it is like some edifice

That no harm can prejudice,

Nor flood nor fire can deface

Never moved from its true place.

Yet she still lacks confidence,

For she strives to make good sense

Of her state, and understand

How all of the matter stands,

Reading it in various ways.

These arguments she displays

For and against his position:

‘What then could be the reason

For Cligès to say ‘completely’,

If Love did not prompt him to?

What power have I then to rule

Him, that he should prize me so

And make me mistress of his heart?

Does he not play a nobler part;

Is he not fairer far than I?

Naught but Love can I descry,

That could grant me such honour.

As one subject to Love’s power,

I’ll show he’d not, unless he loved me,

Claim to be mine ‘completely’;

No more indeed than I should be

All his, if Love, it seems to me,

Had not placed me in his hands;

Nor would Cligès, as I understand,

Confess he was all mine, unless

Amor now held him, under duress.

If he loved not, he’d show no fear.

I hope Amor, who gives me here

To him, likewise grants him to me.

Yet I am still troubled, frequently;

The thought is often used in quite

A trivial way, and so seems trite.

For there is many a flatterer

Who’ll say, to a total stranger:

‘I, and all I have, am yours’,

In idle chatter, like a jackdaw’s,

So I’m filled with uncertainty,

For it might be perhaps that he

Said the words merely to flatter;

And yet I saw his colour alter,

And saw him weep piteously.

In my judgement, thus to be

So changed in face and pale,

Indicates no treacherous tale,

No treachery there or trickery.

Those eyes told no lie to me,

From which I saw the tears fall.

For if I know aught at all,

I saw the very signs of love:

Yes, that sickness I approved;

Woe I had of it, and have still,

My mischance it proved, and will.

Mischance? In truth, God wot,

For I die when I see him not,

Who has stolen my heart from me,

By fawning, and by flattery.

Through his flattery and fawning,

My heart is lost from its dwelling,

And doth its habitation shun,

Avoiding me, and my mansion.

By my faith, he’s mistreated me,

Who holds my heart in captivity.

Who steals what is mine, ah no,

He cannot love me, well I know.

Know? Why then all his tears?

Why? Unsurprising it appears,

He had good reason, certainly.

I must not think they were for me.

For parting from all we know,

Will frequently distress us so.

Thus in leaving those he knew

If he was sad and troubled too,

And wept, well that is no marvel.

But he who offered him this counsel,

That he should go dwell in Britain,

Could not have been, this is certain,

Crueller to me; my heart is flown;

Ill must be theirs who lose their own,

But I have deserved none of this.

Alas, and woe, why should Cligès

Have slain me who am innocent?

Yet why charge him of ill intent?

For I have no reason so to do.

Cligès would not, in my view,

Deign to act thus, at any time,

If his own heart were matched with mine.

But matched with mine it cannot be.

For if with mine it kept company

Mine would never part from his,

Nor his depart now without mine,

For mine would follow his covertly,

They form such goodly company.

And yet, I would say, in all verity,

That they are diverse and contrary.

How are they contrary and diverse?

His is the master and mine serves,

The servant has no will of their own,

But obeys the master’s will alone,

And so forsakes all other affairs.

For my concerns he hath no care,

Nor for my heart, nor my service.

It troubles me sorely then, all this;

One serves, the other rules both.

Why to serve me is my heart loth,

While his heart serves him alone;

Why are not equal powers shown?

My heart is captive, not to move,

Unless his own its motion prove.

And whether his heart goes or stays

Mine, it seems, is prepared always,

To pursue, so follow after his heart.

My God, why are our bodies apart,

So, I cannot my own heart retrieve,

In some manner I might conceive?

Retrieve it? Ah, what foolish folly,

To remove it from sweet ease wholly,

Would indeed its death soon prove.

Let be! I’d not wish for its remove,

But with its lord it should remain,

Till he feels some pity for its pain,

For rather than here, tis there, that he

To his servant should show mercy,

Since both dwell in a foreign land.

If my heart doth flattery understand,

As one must do to serve at court,

Twill do well ere it again reach port.

Who’d wish to stand well with their lord,

And sit on his right hand at board,

Must, as custom doth now assume,

From his own cap remove the plume.

Though it may have no plume at all.

But here is the sore point, I recall,

For while he smooths him outwardly,

Though his lord may own inwardly

Naught but ill-will and villainy,

He’ll never pay him the courtesy

Of saying so, but will ever swear

That none with him could compare,

In depth of wisdom or prowess.

He’ll let him think he doth confess

The truth. For though he is a bear

In manners, or cowardly as a hare,

Mean, or foolish, or knock-kneed,

Or a villain both in word and deed,

He will praise his lord to his face,

Who behind his back calls him base;

And will praise him in his hearing,

When to another he is speaking,

Though his lord feigns not to hear

What either of them says, I fear;

Yet, if his lord cannot so hear,

Then at his master he will jeer;

And if his master seeks to lie,

He with that wish will comply.

Who lords and courts doth frequent

To the ready lie must give consent.

So must my heart meet the case,

If it would garner its lord’s grace;

It must be obsequious and flatter.

Yet Cligès asks no such matter;

A knight so open, fair and true,

Needing naught false or untrue

From my heart, to sing his praise,

For naught is ill in him, it says.

Thus my heart shall him serve,

For as we say in our proverb:

‘Tis a wretched servant fails to be

Improved in his lord’s company.’

Lines 4575-4628 Cligès prepares for a tournament at Oxford

THUS Amor torments Fenice,

Yet it delights her completely,

This torment that never wearies.

While Cligès in his travels is

Come at last to Wallingford;

Occupies lodgings and board,

At great expense, in fine style.

But thinks of Fenice the while,

Nor forgets her for a single day.

While there he cultivates delay,

His men are given to understand,

On enquiring at his command,

For it indeed is told them often,

That King Arthur’s noblemen,

It being also the king’s intent,

Have appointed a tournament.

On the plain in front of Oxford,

Which lies north of Wallingford,

The parties are to make assay,

And the whole to last four days.

Now Cligès while staying there

Has ample time still to prepare,

And buy aught that he must get,

For a fortnight must pass as yet,

Before the start of this tourney.

At once three squires journey

To London at his command,

There to buy, they understand,

Three sets of arms of different colour,

One black, one red, the other

Green, and each set of arms he

Ordered, on their way, to be

With some plain cloth covered,

So if any on the road hovered

About them, he should not know

What hue the arms were below.

The squires take their way, and

Reach London, and find to hand

The equipment that they require.

All being done, they then retire;

Returning swiftly as they can.

The arms, purchased thus to plan,

Shown to Cligès, win them praise.

He has these arms hidden away,

With all those that the emperor

Had given him, by Danube’s shore,

When Cligès was knighted there.

All were now concealed with care,

But if you ask me to say why,

I will not tell you yet, say I,

For I will tell you, and explain,

When at the tourney on the plain,

The highest nobles of the land,

In search of fame, are all on hand.

Lines 4629-4726 Cligès fights, anonymously, in his black armour

King Arthur with his finest knights

Whom he had chosen for the fight,

Before Oxford, now took his stand,

While near Wallingford, as planned,

Ranged most of the other chivalry.

Think you now, I should delay me,

By telling you how, in this affair:

‘This king was here, this count was there,

And so, and so, and so, were present.’?

As was the custom, now was sent

From out the massed gathering, then,

Between the assembled lines of men,

A knight of outstanding bravery

One of King Arthur’s company,

To commence the tournament,

But none advanced their intent

To joust, from the other party,

All held back from the tourney.

And there were those who asked:

‘Why are none of our party tasked

With riding from the ranks to fight,

Surely we will confront this knight?’

While others answered promptly:

‘Do you not see what an adversary

The other side have sent forth?

Who does not know he is worth

Three of the best knights here,

Will quickly learn of it, I fear.

‘Who is he then?’ ‘Do you not see,

Sagramor the Destroyer, is he.’

‘That is he?’ ‘Yes, most certainly.’

Cligès hears this, mounted quietly

On Morel, his charger; blacker

Than a mulberry is his armour;

For all his armour is jet black.

He rides forth to the attack,

Spurs Morel on to the fight

But there’s not one, at this sight,

Who does not say to his neighbour:

‘He rides well, lance couched before,

He looks most skilful, this knight,

And see, he bears his arms aright,

‘He looks most skilful, this knight, and see, he bears his arms aright’

Idylls of the King (p26, 1898) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892)

Internet Archive Book Images

His shield about his neck hangs true,

Yet he must still be thought a fool,

To undertake to win success

By jousting freely with the best

Of all those known in this country.

Where was he born then? Who is he?

Who knows him? ‘Not I.’ ‘Nor I,

Yet naught white about him, say I.’

Now, while they converse amain,

The knights give their mounts full rein,

Being no less on this battle intent

Than they are both keen and ardent

To joust and contend together.

Cligès swiftly attacks the other

Pinning shield to arm, to chest.

Sagramor falls at this first test;

He declares himself a prisoner.

The tourney is fair begun here,

And adversaries meet one on one.

Cligès about the field is gone

Seeking adversaries to fight,

And there is not a single knight

He meets whom he does not conquer.

For he takes all the glory; wherever

He goes to joust and so contend,

The fight comes swiftly to an end.

Only a knight of great prowess

In this tourney dare him address,

For there’s more glory in this fight

In facing him than some other knight,

And if he be conquered by Cligès

From that fact alone glory is his,

In having dared to stay and joust.

Cligès then achieved the most

Of any in that tournament.

At evening swiftly though he went

To his lodgings, and secretly,

So that none there might see,

And meet with him and speak.

And lest any there might seek

A sight of the black armour,

He hid it close in his chamber,

So as not to be found or seen;

Then he hung the suit of green

Above the doorway of the inn,

So if they were seeking him,

The passers-by would see it there,

And not know where his lodgings were.

Lines 4727-4758 King Arthur has search made for the black knight

THUS Cligès, though lodged in town,

By this ruse could not be found,

And those who were his prisoners,

Though they wandered everywhere,

Asking for the black-clad knight,

None could answer them aright.

Even King Arthur had the town

Search for him, both up and down:

But all cried: ‘We’ve not seen any

Trace of him, since the tourney,

And know not what became of him.’

More than twenty squires seek him,

Whom King Arthur has bidden

Search, yet he’s so well hidden,

There’s no sign of our Cligès.

The king is most amazed at this,

When they tell him that no one

Great or small can find the man,

Or any sign that he lodges here,

More than if he were in Caesarea,

Toledo, or Heraklion,

‘By my faith,’ says he, ‘what anyone

Says of it, I know not, yet tis to me

A wonder; some phantom it may be,

That has appeared here in our midst.

Many a knight unhorsed in the lists

Many of the best, indeed, have sworn

A pledge, to one whose very door

They know not, no more his country;

A pledge they must now fail to keep.’

Thus the king aired his discontent,

But might as well have stayed silent.

Lines 4759-4950 Cligès, the knight of many colours

MUCH spoke the noblemen that night,

On the subject of the black-clad knight.

Indeed they spoke of little else.

On the morrow they armed themselves,

Again without summons or request.

And to undertake the first conquest,

Lancelot of the Lake rides out,

Who lacks not courage in the joust.

Lancelot waits for the first-comer:

Cligès is there, clad in green armour,

Far greener than the meadow grass,

And wherever Cligès doth pass,

On his long-maned fallow steed,

None, whether with hair indeed,

Or bald as a coot, that doth not gaze

And to his next door neighbour says:

‘This knight is much more graceful

And is in all respects more skilful

Than yesterday’s black knight did seem,

As the pine eclipses the hornbeam,

And the laurel doth the elder tree.

We still know not who he may be,

He of yesterday, but will tonight

Know the name of this fair knight.

If you know him now, then say.’

But each man tells the other nay,

Nor of seeing him ever is aware,

But than the other he is more fair,

More than Lancelot of the Lake.

If clad in a sack, for goodness sake,

And Lancelot clad in silver or gold,

He’d yet be the fairer, say the bold.

And all of them support Cligès,

And the two men together press,

Spurring their mounts full hard.

Cligès strikes Lancelot and mars

The golden lion on his shield,

So that unhorsed he must yield,

Cligès stands waiting his surrender.

Lancelot yields himself a prisoner,

Unable to mount a fresh defence.

Now doth the tourney commence,

With the sound of splintering lances.

All have faith, as Cligès advances,

Who are supporters of his party,

For, of those he presses closely,

None is of such strength that he

Is not unseated from his steed.

Thus Cligès performed so well,

Took many captive, as many fell,

He gave his side twice the delight,

Won twice the glory in the fight,

That he had on the previous day.

At eventide, he hastened away,

Returning to his lodgings where

He had swiftly displayed there

His red armour, and the trappings,

While that he had been wearing,

He now ordered to be concealed;

So that his name was not revealed.

For his captives sought that night

The lodgings of this green knight,

And yet could see no sign of him.

Most of those who spoke of him

In their lodgings, sang his praise.

All then returned, the next day,

Joyful, fresh, to fight once more.

Now, from the ranks before Oxford,

A knight of great renown there came,

Perceval of Wales was his name.

As soon as Cligès saw him appear,

And heard his name spoken clear,

And knew that this was Perceval,

He yearned to bring about his fall.

From the ranks Cligès issues forth,

Riding a Spanish sorrel horse,

Clad in his vermilion armour,

And all gaze at him in wonder,

Marvelling more than before,

Declaring that they never saw

A knight so truly outstanding;

While the two men go spurring

Toward each other without delay.

Each, bringing his lance into play,

Strikes hard at the other’s shield,

So hard the lances bend and yield,

Though they are short and stout.

Now those watching raise a shout,

For Cligès has struck at Perceval

So hard he falls from the saddle,

And Cligès takes him prisoner,

Without it seeming a great affair.

Once Perceval has pledged his word,

The ranks of knights again are stirred,

As all the contestants meet together.

And Cligès never attacks another,

Without unhorsing his foe swiftly.

There is never an hour that he

Is absent that day from the field,

As all the other knights wield

Their weapons, singly, of course,

Against this rock, never in force,

For that was not the custom then,

Upon his shield these other men

Pound, as hammer on anvil hits;

Hewing, and shattering it to bits.

But every blow he doth repay

Toppling them to earth alway.

And none there, without a lie,

Could say at evening, or deny

That all were forced to yield

To the knight of the red shield.

And all the noblest and the best

Now wished to befriend Cligès.

But that would not soon occur,

For Cligès took his departure,

On seeing the sun about to set.

He doffed his red armour, yet

Had the white armour brought

In which when dubbed he first fought,

And stood the other suits of armour,

And their trappings, before the door,

While tethering his mounts there too.

Now is it seen, by those who view

The armour, that one man singly

Has discomfited, and defeated, many;

And has disguised himself each day,

Changed horse and arms, so he may

Seem not the one who last appeared.

Now for the first time is this clear,

And my lord Gawain says, for one,

He has ne’er seen such a champion.

And since he would meet this same

In the tourney, and learn his name,

Tomorrow he would be first to stir

When all the knights were there.

Yet naught he boasts of, but fully

Expects, if considered carefully,

The other to show, in his advance,

Superiority with the lance,

And yet of the sword however

Might not show himself the master

(For Gawain had no master there).

Now it was his intent in this affair

To prove himself to the stranger

On the morrow, he whose armour,

Mount, and harness change each day.

For he will have moulted four ways,

If every day he changes costume,

To doff the old and a new assume.

Cligès doth so, and is renewed;

The following morn, he is viewed,

Whiter than shines the fleur-de-lis,

The shield gripped by him tightly;

And he, as planned the night before,

On his white Arab steed goes forth.

Gawain the illustrious, the brave,

Once on the field, seeks no delay,

But spurs his steed and advances,

Eager to joust and break lances,

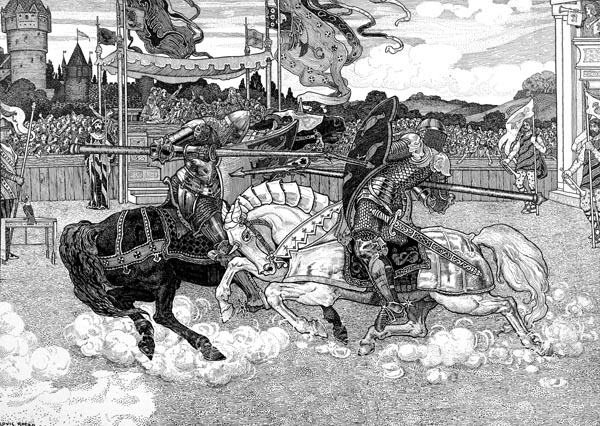

‘Eager to joust and break lances’

Idylls of the King (p78, 1898) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892)

Internet Archive Book Images

If he can meet with his opponent.

And they will meet in a moment,

For Cligès has no wish to delay,

Once he has heard what others say,

They murmur: ‘There rides Gawain,

On horse or foot, a champion plain,

He is one whom none will attack.’

Cligès, hearing this at his back,

Races up-field with couched lance,

The one, and now, the other advance,

With the same leap they meet here,

Swifter than the stag that doth hear

The baying of hounds in the chase.

Shields now against lances brace,

And the blows that they then take

Produce such havoc that they break,

Shiver and splinter and shatter,

Saddle-bows give way, the leather

Girths and their breast-straps snap;

Both are unhorsed at this mishap,

Rise, and draw their naked blades.

All the other knights undismayed

Gathering round to watch the fight.

At last, Arthur parts the knights,

And calls for peace not the sword.

Though before they’d reached accord,

The white hauberks that they wore

They rent, their shields split and tore,

While great blows did they both deal,

That of their helms crushed the steel.

Lines 4951-5040 Cligès is received at King Arthur’s court

FOR a while the king regards them,

Well pleased by the sight of them,

And many another doth confess,

That he now doth esteem no less

The white knight’s deeds on the plain,

Than those of my lord Gawain;

Nor is he ready as yet to rehearse

Which is better and which is worse,

Nor who was likeliest to have won

If they’d been allowed to fight on,

Until the contest was completed:

The King wished neither defeated,

Nor permitted more than was done.

He parted them, before everyone,

And cried: ‘Hold you now, cease all!

Ill shall arise if more blows fall,

Make peace now, and be friends!

Far nephew Gawain, I here extend

My plea to you, without a quarrel

Nor hatred, tis not desirable,

For gentlemen to prolong a fight;

But if to my court, this fair knight,

Wishes to come, and join our play,

It would bring him no harm, I say.

Ask him nephew.’ ‘Willingly sire.’

It accords with Cligès’ own desire.

And he consents to go there gladly,

Once they have ended the tourney.

For he has now quite fulfilled,

All that which his father willed.

But the king declares he has no wish

For them to prolong the finish,

They might cease without delay.

Thus the knights take their way,

At the king’s wish and command.

Cligès his armour doth demand

To follow the king’s company:

Then makes for the court swiftly,

Though altering his guise, to plan,

Presenting himself as a Frenchman.

When he was once arrived at court,

All hastened to meet him; in short

They made such joy and festival

As ne’er was seen, and they did call

Him ‘my lord’ whom he had taken,

And made prisoners in the tourney,

But he would have them all go free,

Not wishing now to hurt their pride,

If they were fully satisfied

That it was he to whom they’d fallen.

Not one claimed he was mistaken,

All cried: ‘We know well it was you;

We value your acquaintance too,

And ought to esteem you highly,

And name you as our lord rightly,

For none of us can equal you.

And just as the sun, risen anew,

Doth outshine all the lesser stars,

And their light fades, much as ours,

When the bright sun rises clear,

So our prowess now, we fear,

Is likewise dimmed and shamed.

Though we too once were famed

In this world, for some like display.’

Now Cligès knows not what to say,

For it seems to him, they praise

Him more than he deserves always;

Though it pleases, still he blushes,

The blood to his cheeks so rushes

It reveals his modesty to all.

Leading him to the great hall,

They bring him before the king;

Their compliments now ceasing,

Their words of praise complete.

Now the hour had come to eat,

Those who do such things enable

Hastened to arrange the tables,

And swiftly these were all set,

Throughout the hall; some wet

Towels, others hold the basins,

To lave all those now entering.

Once laved, all were then seated.

Taking his hand, the king greeted

Cligès, and bade him sit near,

For he was eager now to hear

Who he was, if he might so do.

Of the meal I’ll say naught to you,

But that the dishes were as many

As if cattle were two a penny.

Lines 5041-5114 Cligès reveals his name, is feted, but returns home

WHEN all the dishes had been served

The king no more his speech reserved:

‘My friend,’ he said, ‘I wish to know

If it was pride that delayed you so,

Not deigning to visit my court

As soon as these shores you sought;

And why you kept aloof from others,

And why you changed your armour.

Then confess your name to the king,

And say from what people you spring.’

Cligès replied: ‘I will hide naught.’

All that of him the king now sought,

He told to him, and did him regale.

And when the king had heard the tale,

He embraced Cligès, with delight,

As did the gathering of knights,

‘He embraced Cligès, with delight, as did the gathering of knights’

Idylls of the King (p56, 1898) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892)

Internet Archive Book Images

And my lord Gawain above all

Clasped and embraced him in that hall;

All joined in greeting him together.

And speaking of him to each other

Praised his looks and courage anew.

More than the rest of his nephews,

The king loves him, does him honour.

And Cligès, till the next summer,

Follows the court, with the king,

Through all of Brittany travelling,

The realm of France, and Normandy,

And, by his displays of chivalry,

Proves his worth where he doth go;

The love that wounds him, though,

Is never eased nor assuaged.

The desire with which he’s plagued,

Maintains him always in desire;

To Fenice his thoughts aspire,

Who from afar afflicts his heart.

He longs to return, too long apart,

Deprived for far too long is he,

No longer would he deprived be,

Of sight of the one more desired

Than any other could be desired:

For Greece he prepares to start,

Takes his leave, and doth depart.

My lord Gawain did much grieve,

And so did the king, as I believe,

On failing to keep him there.

Long it seems, that return to her

Whom he loves and desires so,

As over land and sea he doth go;

So long that voyage doth appear,

Great the delay till she is near

Who has stolen his heart away.

But in full she doth him repay,

Restores to him all he has lost,

For her heart doth bear the cost,

Which, as his, is worth no less.

Yet he’s uncertain nonetheless,

Possessing no deed, or covenant,

Thus great is now his troublement.

Nor is she by such pains less rent,

Whom Love plagues and torments.

Taking no pleasure in any sight

That meets the eye, or that might,

Since the hour she saw him last.

What if he lives not? She’s aghast,

Sad, at heart, at that very thought.

Yet Cligès is slowly nearing port,

And fortune has kept him in sight,

The winds have veiled their might.

With joy, journey’s end he marks;

At Constantinople he disembarks.

The news ran swiftly through the city,

And none need ask if the court were happy:

For if it brought joy to the emperor,

The empress felt it a hundred times more.

Lines 5115-5156 Cligès reaches Constantinople

CLIGÈS and all his company

Returning to Greek territory,

Have landed at Constantinople.

All the wealthiest and most noble

Are come to the port to meet him,

And here the emperor greets him,

Who is there before all the rest

Side by side with the empress;

Before all, he doth him embrace,

And welcomes him with grace.

Fenice welcomes him with care;

Both blush to see the other there,

And marvellous it is how they,

Brought so close in every way,

Neither move to embrace, nor kiss

Those kisses that are Love’s bliss;

Yet mad folly that would prove.

The crowd on all sides are moved

To see him, and lead him through

The city. Thus the way they pursue,

Many on foot, on steeds the rest,

Until they reach the imperial palace.

The joy that was there in excess

No words of mine could e’er express,

For his uncle gave him as his own,

All that he had, except the crown.

And asks that he take at leisure

All that might serve his pleasure,

Of gold or silver that he doth hold,

Yet what cares he for silver or gold,

Who does not dare, as yet, reveal

His thoughts to her, who his rest doth steal,

Yet has the chance to explain,

But for his fear of her disdain;

For now he sees her every day,

Sits beside her, and none say nay;

They raise no opposition, I meant,

Thinking naught here of ill intent.

Lines 5157-5280 The lovers converse together

SOME time after his return home

He came one day to the room, alone,

Of her who was not his enemy;

And you may know, of a surety,

The door for him was open wide.

Cligès takes his seat by her side,

The others have all moved away

So none can hear what they say,

Through seated close nearby.

Fenice was the first to try

A few words concerning Britain,

Enquiring about my lord Gawain,

His nature and his appearance,

Until her tongue made acquaintance

With the subject she most feared.

She asked if he was enamoured

Of any lady in that country.

Cligès showed himself not tardy:

He was ready with his reply,

The moment she had spoken:

‘Lady,’ he said, ‘I did love then,

Yet I loved none from that country.

A piece of bark torn from the tree

Was my flesh, forsaking its heart,

For when from Germany I did depart,

I know not what became of my heart,

Except that it never left these parts.

Here was my heart, there my flesh,

I was not there truly, I confess.

For my heart has remained here,

And that is why I thus reappear.

Yet it will not come back to me,

I cannot entice it back you see.

Nor would I seek to if I could.

Has this country now proved good

To you since you came here?

Have you found true joy and cheer?

Like you this people, and this land?

Yet I should, of you, no more demand

Than whether you like this land at all.’

‘It has not pleased, but now it shall

Be both a joy to me and a pleasure.

And know that not for any treasure

Would I desire to forsake it now:

I’d not wrest my heart away, I vow,

Nor would I seek to use such force.

My body bark of the tree, as yours,

So I live, and exist without a heart.

I know not Britain, and yet my heart

Has passed a lengthy sojourn there;

I know not whether in joy or care.’

‘Lady, how could your heart be there?

Tell me then, how it journeyed there,

At what hour, and in what season,

If this be matter that, in reason,

You can tell to me, or another;

And whether I was there moreover.’

‘Yes, indeed, though you knew it not,

Twas there while you were there, I wot,

And with you took its departure.’

‘My God, I saw and knew it never.

Why did I not? If I had known,

For sure, lady, I would have shown

It every pleasant company.’

‘Yet only paid what you’d have owed me,

My friend, much as you ought I ween,

For very gracious would I have been

To your heart if it had pleased

To be where it would have been received.’

‘Lady, it surely came to you?’

‘To me? Then no exile it knew.

For mine came to you also.’

‘Lady, if what you say is so,

Then both our hearts are with us now,

For mine is yours wholly I vow.’

‘And you, friend, you too have mine.

Thus perfectly do we combine.

And know, as God is my sanctuary,

Your uncle has had no part in me:

It pleased me not, and nor could he,

He has, therefore, never known me

As Adam knew Eve who was his wife.

Tis wrong to so name me, upon my life,

For who names me a wife has made

An error, and knows not I am a maid.

Even your uncle he knows it not,

For a sleeping potion he hath got,

And thinks he wakes when he’s asleep,

So that he fancies he doth keep

Company with me in his dream,

Clasped in my embrace, it seem;

But he has never so lain with me.

Yours is my heart, yours my body.

And none shall my example employ

To teach how looseness doth destroy:

When my heart took itself to you,

It gave the body, and promised, too,

None other should have part of me.

Love has wounded me so deeply,

On your account, there is no cure;

Such the pain he’d have me endure.

If I love you, and you love me,

No Tristan ever shall you be,

Nor shall I be Isolde to you,

For then our love would not be true,

But full of blame, and void of right.

No more in me shall you delight,

Bodily, than you do today,

If you cannot find out a way

By which I can be rendered free

Of your uncle and his company,

Without his recovering me again,

Or on us laying all the blame,

Or ever knowing where I am gone.

Tonight, all this go think upon,

And tomorrow then let me know

The best plan that comes to you so,

And I too thus will make surmise.

So tomorrow then, when I arise,

Come at morn and speak with me;

We’ll share our thoughts openly,

And then proceed to execute

Whatever tis best to prosecute.’

Lines 5281-5400 Fenice proposes to feign death

ONCE Cligès knew of her desire,

He agreed with her wish entire,

And said it were best so to do,

Left her happy, and was happy too;

And that night each lay in bed,

And each of them thus delighted,

To plan what might be for the best.

The next morning, from their rest

They met together again, swiftly,

And there took counsel privately,

As indeed they had to, tête-à-tête.

Cligès spoke first when they met,

Of what came to him in the night:

‘Lady,’ he said, ‘I think it right,

And see we could do no better,

Than go to Britain, moreover

I think to see you safely there.

Do not refuse my loving care;

For never with such great joy

Was Helen received in Troy,

When Paris carried her away,

As you would find displayed

And more; for joy we’d bring,

To all the realm of that king,

My uncle; and if you disagree,

Of your own thoughts tell me,

For no matter what occurs, I

With your decision will comply.’

She responded: ‘What I will say,

Is you and I must not run away,

For me the world would insult

As just another blond Iseult,

And speak of you as a Tristan;

If we were to pursue your plan,

All and sundry, everywhere,

Would speak ill of this affair.

None would believe or ought

That all was as was thought,

Who would believe I had made

My escape, while still a maid,

If from your uncle I run away?

A dissolute, and a wanton they

Would call me, and you, a fool.

Saint Paul’s words are as new,

Good to remember and retain;

If any wish to loosen the rein,

Saint Paul counsels them to act

So wisely that they fail to attract

All blame, reproach, or outcry.

It is well to arrest the evil lie;

In this, if it causes you no grief,

I would be the plotter in chief,

For my thoughts suggest to me

That I might feign death easily.

I shall fall sick in a little while,

And you may seek meanwhile,

To ready for me my sepulchre.

And to this devote all your care.

Make you the sepulchre and bier

Such that I shall not stifle here,

And die when I should survive.

Be it unguarded while I’m alive,

And then to retrieve me be ready,

At night, when you will rescue me,

Such that of us no sight be caught;

And let none other bring me aught

I need but you, to whom I render

Myself, and to whom I surrender.

Never in all my life would I rather

Be served in this way by any other.

My friend and servant you shall be,

Whatever you do is fine by me,

I’ll ne’er be mistress of an empire

If you are not its lord and master.

Any mean, wretched hovel at all

Will seem far fairer than palace hall.

And if this thing is done with care,

None shall be the worse for wear.

For none will know of it to speak ill,

Throughout the empire all men will

Think I am shut beneath the earth.

Tessala, who was my nurse at first,

A woman in whom I place great trust,

Will give me her aid, now; she must,

For she is wise, I have faith in her.’

Cligès, once he had heard his lover,

Replied: ‘Lady, if you can do so,

And you believe you nurse also

Will give true counsel to both of us,

We have naught further to discuss,

But must prepare and do it swiftly.

Yet if we fail to enact it wisely,

We are lost without hope of aid.

I have a mason who, if I may

I will consult, for wondrous things,

Are his, he’s famed for his carvings;

Not a land where he’s not known,

For masonry he has made his own.

John is his name, a serf of mine,

There is no artist, however fine,

Who would not take himself to John

To learn from all that he has done;

To him they’re novices or worse,

Say an infant, that’s put to nurse.

And by imitating his work, also,

They have learnt all that they know,

Those masons of Antioch and Rome;

Nor is any man more true to home.

Now I would prove his great skill,

And if I find him as loyal still,

Then he and his heirs will I set free.

And I will reveal all willingly,

And tell him of our secret plan,

If he will swear, as a loyal man,

That he will help me faithfully,

And never betray or you or me.’

Lines 5401-5456 Fenice involves her nurse Thessala in the plan

FENICE replied: ‘So, let it be!’

Cligès then, by her grace set free,

Now went forth and took his way.

She called her nurse straight away.

Tessala, whom she had brought

From her native land, she sought,

And Tessala came there swiftly,

Without delay, or seeming tardy,

Yet not knowing the reason why.

In private speech she sought reply

As to Fenice’s wish and pleasure.

She concealed naught from her

But told Thessala all her plan.

‘Nurse,’ she said, ‘I understand

That anything I share with you

Will never be brought to view,

For in proving you thoroughly,

I found you wise and trustworthy,

Love you for all you’ve done for me,

And in all my ills tis you I seek,

Never accepting other counsel.

Why I lie awake, you know well,

And what I wish for and desire,

My eyes see nothing, they aspire

To one thing only, that delights;

But I cannot enjoy such a sight,

Except I must pay a heavy cost.

I’ve found the one I love the most,

For if I seek him, he seeks me too,

And if I grieve he grieves anew,

For all my sorrow and my pain.

So to you I must needs explain

The thoughts and proposition,

We two, alone in discussion,

Saw fit to confirm and agree.’

Then she told her, privately,

That she wished to feign illness,

And so imitate a true sickness,

She would then appear to die.

He’d steal her away, by and by,

‘So we will be together always.’

There is no other way, she says,

By which they might be sure

Of this, but if she were assured

That Thessala would help her

They might arrange the matter

According to both their wishes.

‘For I am full weary of all this

Longing for joy and happiness.’

Thessala assured her mistress

That she would help her in all,

She need have no fear at all,

Saying she would set in motion

The means to produce a potion

Such that any examining her

Would then immediately infer

That the soul had left the body.

For once swallowed, secretly,

It would turn her veins frigid;

Her body, pale, blotched, rigid,

Seeming without speech or will,

Yet she would be living still,

Feeling nothing, good or bad.

Nor was any harm to be had

From a day and night there,

Entombed in that sepulchre.

Lines 5457-5554 The sculptor, artist, and mason, named John

ONCE she had fully digested

Her nurse’s words, Fenice said:

‘Nurse, I commit myself to you,

And have all confidence in you;

I am yours, so act now for me,

And tell everyone that you see

There is naught for them here,

I am ill, they trouble me I fear.’

To everyone, the wise nurse said

‘Friends, my lady is ill in bed,

And requests you not to stay

You speak too loudly she says

And the noise is troubling her,

She can get no rest moreover

While you are near her chamber,

And she, as far as I remember,

Has never felt such pain before,

Nor suffered with such dolour.

Please leave, yet take no alarm,

Your voices may work her harm.’

And they depart at her command.

Meanwhile Cligès doth demand

That John comes to him secretly

And speaks to him, privately:

‘John, here is what I wish to say;

You are my slave, and I today

Am your master, so I may sell

Or give you away, as any chattel,

Your body or possessions, either.

But if I can trust you in a matter,

That in my mind I have planned,

You’ll be free as any in this land,

You and all your heirs, forever.’

And John replies, who is ever

Desirous of winning his liberty:

‘Sire, there is nothing in verity

I would not do, if it might be

That I could achieve my liberty,

And my wife’s and children’s too.

Give your orders; thus will I do;

For there is no work so toilsome,

It can ever prove too irksome

Or too laborious for me.

Besides, however it might be,

I must ever attend to your cares,

And neglect my own affairs.’

‘True, John, but this is a matter

That my mouth is loath to utter,

Unless you swear an oath to me,

And do assure me, faithfully,

You will give me of your aid,

And never will I be betrayed.’

‘Willingly, sire,’ John replied,

‘Do not fear, by such I’ll abide,

For I pledge to you and swear

That I will never do anywhere,

All the days of my life, or say,

Aught to harm you in any way.’

‘John, not even for martyrdom

Dare I speak of this to anyone,

This, in which I seek your advice;

I had rather pluck out my eyes.

You will obey, I trust, my pleasure;

Help, and be silent, in equal measure?’

‘Truly, Sire, and may God aid me!’

Then Cligès tells him all openly,

And reveals all the plan to him,

And when he has explained to him

Everything of which you know,

For you have heard me tell you so,

Then John assures his master

That he will build a sepulchre

To the very best of his skill;

And furthermore that he will

Take him to see a fine building

Of which none knows a thing,

Not even his wife or children.

He will show what he has done,

If Cligès desires to go, and see,

Where he carves and paints; free

Of anyone but himself alone;

The loveliest place, the finest known

To him, anywhere, both far and wide.

‘Let us go, then!’ Cligès replied.

The End of Part III of Cligès