Aloysius Bertrand

Gaspard de la Nuit

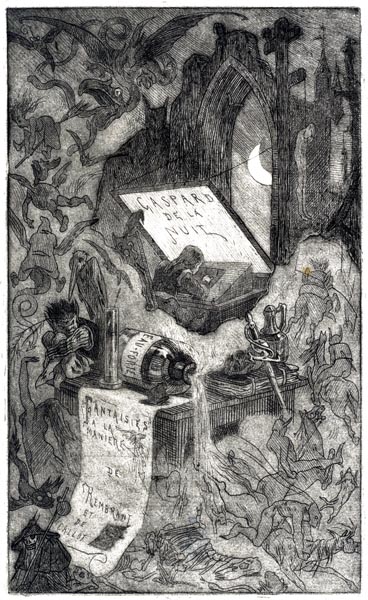

Gaspard de la Nuit, 1868

Félicien Rops (French, 1833-1898) - National Gallery of Art

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2024 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction.

- Bertrand’s Prologue.

- Gaspard’s Preface.

- Dedication: To Victor Hugo.

- Gaspard de la Nuit: Book One.

- The Flemish School – I: Harlem.

- The Flemish School – II: The Mason.

- The Flemish School – III: The Schoolboy from Leiden.

- The Flemish School – IV: The Pointed Beard.

- The Flemish School – V: The Tulip-Seller.

- The Flemish School – VI: The Fingers of One Hand.

- The Flemish School – VII: The Viola da Gamba.

- The Flemish School – VIII: The Alchemist.

- The Flemish School – IX: Leaving for the Sabbath.

- Gaspard de la Nuit: Book Two.

- Old Paris – I: The Two Jews.

- Old Paris – II: The Beggars.

- Old Paris – III: The Lantern.

- Old Paris – IV: The Tour de Nesle.

- Old Paris – V: The Model of Refinement.

- Old Paris – VI: The Evening Office.

- Old Paris – VII: The Serenade.

- Old Paris – VIII: Messire Jean.

- Old Paris – IX: Midnight Mass.

- Old Paris – X: The Bibliophile.

- Gaspard de la Nuit: Book Three.

- Night and its Enchantments – I: The Gothic Chamber.

- Night and its Enchantments – II: Scarbo.

- Night and its Enchantments – III: The Madman.

- Night and its Enchantments – IV: The Dwarf.

- Night and its Enchantments – V: Moonlight.

- Night and its Enchantments – VI: The Dance Under the Belltower.

- Night and its Enchantments – VII: A Dream.

- Night and its Enchantments – VIII: My Great-Grandfather.

- Night and its Enchantments – IX: Ondine.

- Night and its Enchantments – X: The Salamander.

- Night and its Enchantments – XI: The Sabbath Hour.

- Gaspard de la Nuit: Book Four.

- The Chronicles – I: Master Ogier (1407).

- The Chronicles – II: The Postern Door to the Louvre.

- The Chronicles – III: The Flemings.

- The Chronicles – IV: The Hunt (1412).

- The Chronicles – V: The Retreat-Seekers.

- The Chronicles – VI: The Big Battalions.

- The Chronicles – VII: The Lepers.

- The Chronicles – VIII: For a Bibliophile.

- Gaspard de la Nuit: Book Five.

- Spain and Italy – I: The Cell.

- Spain and Italy – II: The Muleteers.

- Spain and Italy – III: The Marquis of Aroca.

- Spain and Italy – IV: Henriquez.

- Spain and Italy – V: The Alarm.

- Spain and Italy – VI: Father Pugnaccio.

- Spain and Italy – VII: The Song of the Mask.

- Gaspard de la Nuit: Book Six.

- Sylvan Pieces – I: My Cottage.

- Sylvan Pieces – II: Jean des Tilles.

- Sylvan Pieces – III: October.

- Sylvan Pieces – IV: Chèvre-Morte.

- Sylvan Pieces – V: Another Spring.

- Sylvan Pieces – VI: Mankind For A Second Time.

- Afterword – To Monsieur Saint-Beuve.

- Pieces Extracted from the Author’s Portfolio.

- Le Bel Alcade: The Handsome Judge.

- The Angel and the Faery.

- The Rain.

- The Two Angels.

- Evening on the Water.

- Madame de Montbazon.

- The Night After the Battle.

- The Citadel of Wolgast.

- The Dead Horse.

- The Gibbet.

- Scarbo.

- To Monsieur David d’Angers, sculptor.

Translator’s Introduction

Louis Bertrand (1807-1841), better known by his pen name Aloysius Bertrand, was born in Ceva, Piedmont (then in France, now in Italy). He studied at the Collège Royal in Dijon, from 1818 to 1826. Praised for his early writings by Hugo and Saint-Beuve, he moved to Paris in 1828 but was relatively unsuccessful there, returning to Dijon in 1830 where he became editor of a Republican newspaper, Patriote de la Côte-d’Or. In 1833, he was back in Paris where the manuscript of Gaspard de la Nuit was accepted for publication, though the work was not printed until after his death. In Paris, he led a financially precarious life as a poet and playwright, contracting tuberculosis which resulted in his death in 1841.

In Gaspard de la Nuit Bertrand is credited with inventing the prose-poem, which later inspired Baudelaire to pen his set of prose-poems Le Spleen de Paris, while Bertrand was also admired by Mallarmé and the Symbolists, and later the Surrealists. Gaspard de la Nuit inspired a painting by Magritte, and three piano solos by Ravel.

Bertrand’s Prologue

‘On our way to Cologne, my friend, of a Sunday,

There in Dijon, at the heart of Burgundy,

Did we not admire spires and gateways, for hours,

Old mansions in courtyards, and lofty towers.’

Saint-Beuve, The Consolations.

A Gothic Dungeon,

A Gothic Spire,

To the skies aspire,

And there’s Dijon.

Her vineyards, joyful,

Possess no equal;

Her bell-towers, then,

At a count, made ten.

Guyton’s Rat sculpted

Pints there, or painted.

There, portals, well-made,

Fanlike, are displayed.

Moult te tarde! Dijon,

While my lute, nose-flat,

Sings your mustard, bonne,

And your Quarter-Jack!

I love Dijon as the child does his nurse whose milk he sucked, as the poet does the girl who inspired his heart. — Childhood and poetry! How ephemeral the one, how deceptive the other! Childhood is a butterfly that hastens to burn its pale wings in the flame of youth, while poetry is like the almond tree: its flowers are fragrant, its fruits are bitter.

One day I was sitting alone in the Jardin de l’Arquebuse — so named for the weapon which in other days was so often a feature of the Knights of the Papeguay there. Immobile on a bench, one might have compared me to the statue on the Bazire bastion. That masterpiece by the figurist Sévallée and the painter Guillot represented an abbot sitting and reading. Nothing was missing from his costume. From a distance, he might be taken for a real person; nearer-to, you could see that it was a plaster-cast.

A cough from a passer-by dispersed my swarm of dreams. He was a poor devil whose exterior announced only wretchedness and suffering. I had already noted, in those same gardens, his threadbare overcoat which buttoned to his chin, his shapeless felt hat which had never been brushed, his long hair hanging down like a weeping willow, and tangled like brushwood, his gaunt hands, like ossuaries, his mocking, sulky and sickly physiognomy thinned by a Nazarene beard; and my conjectures had charitably ranked him among those minor artists, fiddle-players, and portrait painters, whom an insatiable hunger and an inextinguishable thirst condemn to roam the world in the footsteps of the Wandering Jew.

There were now two of us on the bench. My neighbor was leafing through a book, from the pages of which a dried flower escaped without his knowledge. I rescued it, and returned it to him. The stranger, thanking me, raised it to his withered lips, and replaced it in the mysterious book.

– ‘That flower,’ I ventured to say to him, ‘is doubtless the symbol of some sweet love, long-buried? Alas! We all have a time of happiness in the past which disenchants us with the future.’

– ‘Are you a poet?’ he replied, smiling.

The thread of conversation was knotted now; on what reel would it be wound?

– ‘A poet, if to be a poet is to have sought out art!’

– ‘You searched for art! And did you find it?’

– ‘Would to heaven that art was not a chimera!’

– A chimera! ... Yet I too sought it!’ he exclaimed with the enthusiasm of genius, and an emphatic air of triumph.

I begged him to tell me to which maker of spectacles he owed his discovery, art having proved to me like a needle in a haystack...

– ‘I had resolved,’ he said, ‘to seek art as, in the Middle Ages, the Rosicrucians sought the philosopher’s stone; art, is the philosopher’s stone of the nineteenth century! An initial question exercised my scholastic powers. I asked myself: What is art — Art is the poet’s Science — A definition as clear as a diamond of the first water. But what are the elements of art? A second question which I hesitated for several months to answer.

— One evening as I was digging amidst the powdery dust of a second-hand bookstore by the light of a smoky lamp, I unearthed a small book, written in an unintelligible and baroque language, the title of which, emblazoned with a heraldic winged-serpent, displayed, on a banner, these two words: “Gott — Liebe”. A few sous paid for this treasure. I climbed to my attic room, and there, as, filled with curiosity, I attempted to spell out the words of that enigmatic book, before my window bathed in moonlight, it suddenly seemed to me to me as if the finger of God was touching the keyboard of some universal organ. So do buzzing moths emerge from the hearts of flowers whose lips pale beneath the kisses of night. I leaned from the window and looked down. A surprise! Was I dreaming? There was a terrace whose existence I had not suspected exhaling the sweet emanations of its orange-trees; a young girl dressed in white, who played on a harp; and an old man dressed in black who prayed on his knees! — The book fell from my hands.

I descended to join the occupiers of the terrace. The old man was a minister of the Reformed religion who had exchanged the cold homeland of his native Thuringia for the lukewarm exile of our Burgundy. The musician was his only child, a blonde, frail beauty, seventeen years of age, who was suffering from a wasting sickness; and the book I had claimed was a German prayer-book for the use of churches of the Lutheran rite and bearing the arms of a prince of the house of Anhalt-Coëthen.

Ah! sir, let us not stir the dormant ashes! Elisabeth is no more than a Beatrice in an azure dress. She is dead, sir, dead, and here is the prayer-book over which she poured out her timid heartfelt prayer, the rose into which she breathed her innocent soul — like her a withered flower, a book, closed like the book of her fate! — Blessed relics that she will not fail to recognize in eternity, relics drenched with tears, when, the Archangel’s trumpet having broken the stones of my tomb, I will fling myself beyond the worlds to be with that adored virgin, to sit beside her at last, beneath God’s gaze! ...

– ‘And art?’ I asked him.’

– ‘That which in art is sentiment was my painful conquest. I had loved, I had prayed. “Gott — Liebe”, God and Love! — But that which in art is idea still drew my curiosity. I believed I would find the complement of art in nature. So, I studied nature.

I would leave my house in the morning and not return till evening. Sometimes, leaning on the parapet of some ruined bastion for many an hour, I loved to breathe the wild and penetrating perfume of the scented stock which speckles with golden bouquets the ivy-covered fabric of Louis XI’s feudal and defunct citadel; to view the tranquil landscape troubled by a gust of wind, a shaft of sunlight, or a shower of rain, the ortolans, and the fledglings piping from their nest in the hedgerows, dappled with light and shade, the thrushes hastening from the hill-slopes to feed on vines tall and bushy enough to hide the fabled deer, the crows descending from every corner of the sky, in wearisome flocks, to pluck at the carcass of a horse abandoned by the flayer of horses in some green valley; to listen to the washerwomen beating the clothes joyfully on the banks of the Suzon, and to the child singing a plaintive melody while turning the rope-maker’s wheel beneath the walls. — Sometimes I chose for my reveries a path of moss and dew, silence and tranquility, far from the city. How often have I robbed the bushes of their red and acid fruits among the haunted thickets of the Fount of Youth, and the hermitage of Notre-Dame-d’Étang, that Fount of the Spirits and the Fairies, and that Devil’s hermitage! How often have I gathered petrified whelk, and fossilised coral on the stony heights of Saint-Joseph, ravaged by a storm! How often have I fished for crayfish in the disheveled fords of the Tilles, those streams filled with watercress that shelter the icy salamander, and water lilies whose indolent flowers yawn! How often have I spied a grass snake on the mired strands of Saulons, which hear only the monotonous call of the coot and the funereal cry of the grebe! How many times have I illumined with a candle the underground caves of Asnières, where stalactites slowly distill their eternal water-drops from the clepsydra of the centuries! How many times have I sounded my horn, on the vertical cliffs of Chèvre-Morte, as the coach climbed, painfully, the track three hundred feet below my fogbound-throne! And the nights, those summer nights, balsamic and diaphanous; how many times have I not I moved like a lycanthrope about the fire that I lit in the grassy, deserted valley, until the first blows of the woodcutter’s axe shook the oaks! Ah, sir, how many attractions solitude offers to the poet! I would have been happy to live in the woods and make no more noise than the bird quenching its thirst at the spring, the bee buzzing about the hawthorn, and the falling acorn breaking through the leaves!’ ...

— ‘And art?’ I asked him.

— ‘Patience! Art remained in limbo. I had studied the spectacle of nature; I now studied the monuments of men.

Dijon has not always spent its idle hours at concerts performed by its harmonious children. It donned the hauberk — capped its head with the morion helm — brandished the partisan — unsheathed the sword —primed the arquebus — aimed the cannon from its ramparts — coursed the field with beating drums and torn ensigns, and, like the grey bearded minstrel who sounded the trumpet before scraping at the rebec, it would have wondrous stories to tell you, or rather, its crumbling bastions would, that contain in their soil mixed with debris the leafy roots of its horse-chestnut trees, and its ruined castle would, whose bridge trembles under the exhausted step of the gendarme’s mare returning to barracks, — everything attests to two Dijons: the Dijon of today, the Dijon of yesteryear.

I had soon disinterred that Dijon of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries about which ran a ring of eighteen towers, with eight gates, and four portelles or posterns — the Dijon of Philippe-le-Hardi, of Jean-sans-Peur, of Philippe-le-Bon and Charles-le-Téméraire, with its cob houses, their gables pointed like a madman’s cap, their facades barred with Saint Andrew’s crosses; and its fortified hôtels, with narrow barbicans, double wicket-gates, and cobbled courtyards: — with its churches, its holy chapel, its abbeys, its monasteries, forming processions of bell towers, spires, needles, deploying as banners their stained-glass windows of gold and azure, parading their miraculous relics, kneeling to the dark crypts of their martyrs, or the repository of their flowering gardens; — with its flowing Suzon whose course, replete with little wooden bridges and flour mills, separated the territory of the abbot of Saint-Bénigne from the territory of the abbot of Saint-Étienne, like a bailiff in parliament setting his rod and his cry of ‘Hold!’ between two litigants puffed-up with anger; — and, finally, with its populous suburbs, one of which, that of St-Nicolas, spread its twelve streets to the sun, like no more nor less than a fat pregnant sow displaying her twelve udders. — I had galvanized a corpse into life, and the corpse had risen.

Dijon rises; rises, walks, runs! Thirty church-bells chime away, in an ultramarine blue sky such as old Albrecht Dürer painted. The crowds flock to the inns of the Rue Bouchepot, to the bathhouses of Porte aux Chanoines, to the promenade on Rue St-Guillaume, to the exchange on Rue Notre-Dame, to the arms factories of Rue des Forges, to the fountain on Place des Cordeliers, to the communal oven on Rue de Bèze, to the market halls on Place Champeaux, to the gibbet on Place Morimont; bourgeoisie, nobles, freemen, scoundrels, priests, monks, clerics, merchants, servants, Jews, Lombards, pilgrims, minstrels, officials belonging to parliament and the ‘chamber of accounts’, tax-officials, officers of the duke’s household: proclaiming, whistling, singing, moaning, praying, grumbling — in carts, litters, on horseback, on mules, on Saint Francis’ nag. — How can we doubt this resurrection? There floats in the breeze the silk standard, half green, half yellow, embroidered with the city’s coat of arms, red with golden vines leafed with green (gueules au pampre d’or feuillé de sinople).

But what cavalcade is this? It is the duke, off to enjoy the chase. The duchess has already preceded him to the Château de Rouvres. The magnificence of the equipage, the endless procession! Monseigneur the duke spurs on a dappled grey, which shivers in the sharp, pungent air of morning. Behind him prance and strut the Rich of Châlons, the Nobles of Vienne, the Braves of Vergy, the Pride of Neuchâtel, the Good Barons of Beaufremont — And these two who ride at the back of the file? The younger, distinguished by his oxblood-velvet suit and his quivering cap, screams with laughter; the older, clad in a black cloth cape from beneath which he removes a voluminous psalter, lowers his head in confusion: one is the King of the Rascals, the other is the duke’s chaplain. The fool asks the wise man questions the latter cannot answer; and while the populace shouts Noël! — how the palfreys neigh, the bloodhounds bark, the horns sound their fanfare, they, the reins loose on the necks of their ambling mounts, discourse in a familiar manner of the wise lady Judith, and the brave Maccabeus.

A herald, however, blows his trumpet on the tower of the duke’s dwelling. He points to the huntsmen, in the plain, letting fly their falcons. It is rainy weather; a greyish mist in the distance hides the abbey of Citeaux from him, its woods bathed by the marshes; but a shaft of sunlight reveals to him the Castle of Talant, closer and more distinct, whose terraces and platforms raise their crenellations to the clouds, — the manors of the Lord of Ventoux and the Lord of Fontaine, whose weathervanes pierce the mass of greenery, — the monastery of Saint-Maur whose dovecotes stand like spires in the midst of a flock of pigeons,— the leprosarium of St-Apollinaire which has only one door and no windows, — the chapel of St-Jacques de Trimolois, which looks like a pilgrim covered in shells; — and under the walls of Dijon, beyond the farms of the abbey of St-Bénigne, the cloisters of the Charterhouse, white as the robes of the Carthusian disciples of Saint Bruno.

The Charterhouse of Dijon! The Saint-Denis of the Dukes of Burgundy! Oh, why must children be jealous of their fathers’ masterpieces! Visit the site of the Charterhouse, nowadays, and your feet will stumble over stones in the grass, stones which were once the keystones of arches, altar tabernacles, tombstones, oratory slabs; stones about which incense has smoked, wax has burned, the organ has murmured, where dead dukes have bowed their foreheads. — O nullity of grandeur and glory! We plant pumpkin seeds in the ashes of Philippe-le-Bon! — The Charterhouse is no more! Yet I am wrong. — The church portal and the bell-tower’s turret are still standing; the turret slender and light, a tuft of wallflower in its ear, resembles a youth leading a greyhound on a leash; the portal of hammered stonework would still be a jewel if hung about the neck of a cathedral. In addition to this, in the courtyard of the cloister, a gigantic pedestal is set, from which the cross is absent and about which are nestled six statues of prophets, admirable in their desolation. — And what do they mourn? They mourn the cross that the angels have borne back to heaven.

The fate of the Charterhouse was that of most of the monuments which embellished Dijon at the time of the union of the duchy with the royal domain. The city is nothing more than a shadow of its former self. Louis XI stripped it of its power, the revolution decapitated its bell-towers. There remain but three churches from seven churches, a holy chapel, two abbeys and a dozen monasteries. Three of the city’s gates are blocked-up, its posterns demolished, its suburbs razed, its Suzon stream plunged into the sewers; its population has shed its leaves, and its nobility have fallen to earth. — Alas, only too clearly, we see Charles-le-Téméraire and all his chivalry departing for battle — nigh-on four centuries ago —and not returning.

And I wandered among these ruins like the antiquary who searches for medals in the furrows of a Roman fort after a heavy rainstorm. Dijon, though expired, still retains something of what it was, similar to those rich Gauls who were buried with a gold coin in their mouth, and another in their right hand.’

— ‘And art?’ I asked.

— ‘I was occupied one day, in front of the church of Notre-Dame, in gazing at the Quarter-Jack (Jacquemart) and his wife and child, who were hammering away at noon. — The exactitude, the weightiness, the phlegmatic appearance of Jacquemart would attest to his Flemish origin, even if we ignore the fact that he dispensed the hours to the good bourgeois of Courtrai (Kortrijk, Belgium) during the sack of that city in 1383. Gargantua stole the bells of Paris, Philippe-le-Hardi the clock of Courtrai; each prince according to his stature. A burst of laughter was heard above, and I saw, on a corner of the Gothic building, one of those monstrous figures that the sculptors of the Middle Ages attached by their shoulders to the cathedral eaves; an atrocious face of the damned who, a prey to suffering, stuck out his tongue and gnashed his teeth, while wringing his hands. — It was he that had laughed.

— ‘You had a speck of dust in your eye!’ I cried.

— ‘Neither a speck in the eye, nor wax in the ear. — The stone face had laughed, — laughed with a grimacing, dreadful, infernal laugh — but sarcastic — incisive — picturesque.’

I felt ashamed for having granted this a monomaniac so much of my time. However, with a smile, I encouraged this Rosicrucian of art to continue his droll story.

— ‘The experience,’ he continued, ‘gave me food for thought. — I reflected that, since God and Love were the primary aspects of art, that which in art is sentiment — Satan could well be the secondary aspect, that which in art is idea — Was it not the devil who built the cathedral of Cologne?

Behold me in quest of the Devil. I redden over Cornelius Agrippa’s books of magic, and I slaughter my neighbor the schoolmaster’s black hen. The Devil no more appears than at the end of a devotee’s rosary! Nonetheless he exists: — Saint Augustine, with his pen, made the thing official: Daemones sunt genere animalia, ingenio rationabilia, animo passiva, corpore aerea, tempore aeterna (Devils are living beings, intellectually rational, spiritually passive, ethereal in body, eternal in time). This is certain. The Devil exists. He speaks in the chamber, he pleads in the palace, he plays the stock market. We engrave him in vignettes, weave him into novels, dress him up in plays. We see him everywhere, as I see you. It was the better to pluck hairs from his beard that pocket mirrors were invented. Punchinello missed his enemy and ours. Oh, if only he’d hit the back of his head with his truncheon!

I drank the Paracelsian elixir in the evening before going to bed. It gave me colic. Nowhere did the Devil in horns and a tail appear.

A further disappointment: that night a storm soaked to the bone the old city crouched in sleep. How blindly I groped among the crevices of Notre-Dame, to commit my sacrilege. There is no lock to which crime lacks the key. — Pity me! I had need of a holy wafer and a sacred relic — A light pricked the darkness, several more appeared, successively, and I could soon distinguish the figure whose hand, extended by a long lamplighter’s pole, distributed flame to the candles of the high altar. It was the quarter-jack, Jacquemart, who, no less imperturbable than usual beneath his patched iron shell, completed his work without appearing worried by, or even aware of, the presence of a profane witness. Jacqueline, his wife, kneeling on the steps, remained perfectly motionless, rain flowing from her lead skirt arranged in the Brabant fashion, from her sheet-metal throat-piece piped like Bruges lace, from her varnished wooden face with the cheeks of a Nuremberg doll. I was stammering out a humble question to her regarding the Devil and art, when Maritorne’s arm sprang forth with the sudden and brutal force of a spring, and, to the hundred-fold echoing sound of the heavy hammer which she grasped in her fist, the crowd of abbots, knights, and benefactors who populate the Gothic vaults of the church with their Gothic effigies, flocked in procession around the altar, bright with the vivid winged splendours of the Christmas crib. The black Virgin, the Virgin of barbarous times, a cubit high, with her shimmering golden crown, her stiff dress of pitch and pearl, the miraculous Virgin before whom a silver lamp glows, leapt down from her seat, and flew across the flagstones with the speed of a spinning-top. She approached from the depths of the nave, with graceful, uneven leaps, accompanied by a little Saint John of wax and wool, which was ignited by a spark, and which melted in blue and red. Jacqueline had armed herself with scissors, to shear the occiput of her swaddled child; far off a candle illuminated the baptistery chapel, and then...

— ‘What then?’

— ‘And then, the sun shining through a crack, the sparrows pecking at my windows, and the bells muttering an antiphon to the clouds woke me. It was a dream.’

— ‘And the devil?’

— ‘Does not exist.’

— ‘And art?’

— ‘That exists.’

— ‘But where?’

— ‘In God’s breast!’ — And his eye, where a tear swelled, probed the sky — ‘We are, sir, only the Creator’s copyists. The most magnificent, the most triumphant, the most glorious of our ephemeral works is never more than a shameful counterfeit, the extinguished spark of the least of His immortal works. All originality is an eaglet that only breaks from its shell in the sublime and thunderous region of Sinai — Yes, sir, I have long sought absolute art! O delirium! O madness! Behold this forehead furrowed by the iron crown of misfortune! Thirty years! And the mystery, the arcanum I have solicited with so many stubborn vigils, to which I have sacrificed youth, love, pleasure, fortune, that arcanum dwells, inert and insensible, like the meanest pebble, among the ashes of my illusions! Nullity fails to grant life to nullity.’

He rose. I showed my commiseration in a hypocritical and banal sigh.

— ‘This manuscript,’ he added, ‘will inform you of the many shapes my lips attempted before arriving at one which sounds a pure and expressive note, the many brushes I employed on my canvas before seeing the vague dawn of chiaroscuro appear. Here are recorded various procedures, new perhaps, involving harmony and colour, the only result, the only reward that my lucubrations may have obtained. Read; you can return it to me tomorrow. Six o’clock strikes from the cathedral; the hours chase the sun which slips away from that row of lilacs. I shall lock myself away and write my will. Good evening to you.’

— ‘Monsieur!’

Bah! He was far away. I remained as quiet and sheepish-looking as a president whose clerk has caught a flea that was riding his nose. The manuscript was entitled: Gaspard de la Nuit, Fantasies in the manner of Rembrandt and Callot.

The next day was a Saturday. Nobody occupied the garden of the Arquebus except some Jews who were celebrating their Sabbath. I ran through the town enquiring for Monsieur Gaspard de la Nuit of every passer-by. Some replied: ‘Oh! You joker!’ — Others: — ‘May he wring your neck!’ — And they all immediately abandoned me to my own devices. I approached a wine-seller from the rue Saint-Felebar, dwarfish and hunchbacked, who stood in his doorway laughing at my embarrassment.

— ‘Do you know Monsieur Gaspard de la Nuit?’

— ‘What do you want from that fellow?’

— ‘I want to return a book he lent me.’

— ‘A grimoire, a book full of spells!’

— ‘What, a grimoire!... Say where he lives, I beg you.’

— ‘Over there, where that claw-head hangs.’

— ‘But that house... that’s the house of a priest.’

— ‘I’ve just seen someone tall and dark-haired enter, one who changes their black clerical garb for white.’

— ‘What do you mean?’

— ‘I mean that Monsieur Gaspard de la Nuit sometimes dresses as a young and pretty girl to tempt devout people — witness his adventure with Saint Anthony, my patron.’

— ‘Spare me your malice; tell me where Monsieur Gaspard de la Nuit may be.’ — ‘In Hell, if he’s not elsewhere.’

— ‘Ah! I think I understand, at last! Then, Gaspard de la Nuit must be ...

— ‘Why, yes... the Devil!’

— ‘Thanks, my friend!... If Gaspard de la Nuit is in Hell, let him roast there! I’ll publish his book.’

Gaspard’s Preface

Art always has two antithetical sides, as a medal for example, might show on one side the likeness of Paul Rembrandt and the other side that of Jacques Callot — Rembrandt as the white-bearded philosopher who curls up in his corner, absorbed in meditation and prayer, who closes his eyes to collect himself, who converses with the spirits of beauty, science, wisdom and love, and who is wholly concerned with penetrating the mysterious symbols of nature — Callot, on the other hand, as the swaggering and ribald foot-soldier who struts in the square, makes a noise in the tavern, caresses the gypsy girls, swears only by his rapier and his carbine, and is concerned with nothing but the waxing of his moustache — Well, the author of this book has considered art according to this dual personification; but was none too exclusive, since here, in addition to fantasies in the style of Rembrandt and Callot, are studies as per Van Eyck, Lucas de Leyden, Albrecht Dürer, Pieter Neefs, Breughel the Elder, Breughel the Younger, Van Ostade, Gerrit Dou, Salvator Rosa, Murillo, Fuseli and several other masters of the various schools.

And if we ask why the author does not, at the start of his work, advocate some fine literary theory, he will be forced to answer that nor does Monsieur François Séraphin reveal the mechanism of his ‘Chinese shadows’, and that Punchinello hides from the curious crowd the thread that works his arm. — He is content to sign his work: Gaspard de la Nuit.

Dedication: To Victor Hugo

Portrait of Victor Hugo (anonymous) - Wikimedia Commons

‘Glory knows not my unknown dwelling.

All alone, I sing my song of mourning,

Possessing a charm for none but me.’

Charles Brugnot, Ode.

‘A straw for your wandering spirits!’ said Adam Woodcock;

‘I mind them no more than an earn cares for a string of wild-geese –

they have all fled since the pulpits were filled with honest men

and the people’s ears with sound doctrine.’

Walter Scott, The Abbot, Chapter XVI.

Your graceful volume of verse, will be the cherished possession in a hundred years’ time, as it is today, of powerful ladies, gentlemen, and minstrels; an anthology of chivalry, a Decameron of love, to lend charm to the noble idleness of mansion houses.

But this little book, that I dedicate to you, will suffer the fate of everything mortal, after having, for a morning perhaps, entertained both the court and the city which both amuse themselves with petty things.

Then, if some bibliophile takes it into his head to exhume this mouldy and worm-eaten work, he will find, amidst its first pages, your illustrious name, that will have failed to save mine from oblivion.

His curiosity will free my frail swarm of spirits, so long imprisoned by the silver-gilt locks of their parchment jail.

And it will be for him a discovery no less precious than that of some printer’s legend in Gothic lettering, emblazoned with a unicorn or two storks, is to us.

Paris, September 10, 1836.

Gaspard de la Nuit: Book One

Here begins the first

Book of the Fantasies

Of Gaspard

De la

Nuit

The Flemish School – I: Harlem

‘When Amsterdam’s gold rooster crows, that day,

The golden hen of Harlem will lay.’

The Centuries of Nostradamus.

Harlem, that admirable ‘bambochade’ (scene of ordinary life) which sums up the Flemish school; Harlem painted by Jean Breughel, Pieter Neefs, David Teniers and Paul Rembrandt;

And the canal, where blue water trembles, and the church where gold glazing blazes, and the ‘stoël’ (stone balcony) where laundry dries in the sun, and the roofs, green with hops;

And the storks that beat their wings about the city clock, stretching their necks from the heights and catching the raindrops in their beaks;

And the carefree burgomaster who strokes his double chin with his hand, and the love-struck florist who wastes away, his gaze fixed on a tulip;

And the gypsy who swoons over her mandolin, and the old man who plays the ‘Rommelpot’ (friction drum), and the child inflating a bladder;

And the drinkers who smoke in the one-eyed tavern, and the maid-servant who hangs a dead pheasant from the window.

The Flemish School – II: The Mason

Master Mason: – ‘Look now at those

Bastions, buttresses, you’d suppose

Built to endure through all eternity.’

Schiller, William Tell, Act I, Scene III.

The mason Abraham Knupfer sings, trowel in hand, in the scaffolded air, at such a height that, reading the gothic verses of the lowest bell, his feet are level both with the church and its thirty flying buttresses and the city with its thirty churches.

He sees the dragon-shaped stone gargoyles vomiting water from the slates onto the confused abyss of galleries, windows, pendants, bell-towers, turrets, roofs and wooden frames, over which the motionless indented tercelet’s wing casts a grey shadow.

He sees the star-shaped fortifications, the citadel puffed up as if by the filling in a cake, the palace courtyards where the sun dries the fountains, and the monastery cloisters where shadows wheel about the pillars.

The imperial troops are lodged in the suburbs. Behold, a horseman drumming there. Abraham Knupfer can see his three-cornered hat, his aiguilettes of red wool, his cockade traversed by a braid, and his queue tied with a ribbon.

Further off, he sees soldiers who, in the park plumed with gigantic branches, on its wide emerald lawns, riddle with arquebus-shots a wooden bird stuck on the tip of a Maypole.

And, at evening, as the harmonious nave of the cathedral fell asleep, arms extended in the shape of a cross, he saw from his ladder a village on the horizon set alight by the soldiers, which blazed like a comet in the azure.

The Flemish School – III: The Schoolboy from Leiden

We cannot take too many precautions

at the current time, especially,

since the counterfeiters have

established themselves in this country.

The Siege of Bergen op Zoom.

He sits in an armchair upholstered with Utrecht velvet, Messire Blasius, his chin in his fine lace ruff, like a fowl some cook has roasted, set on an earthenware pot.

He sits down at his bank-counter to tell over the half-florins; I, a poor schoolboy from Leiden, with a cap and openwork breeches, standing on one foot like a heron on a paling.

Here are the portable scales which emerge from their lacquer box, with its bizarre Chinese figures, like a spider that, folding its long arms, takes refuge in a tulip tinted with a thousand colours.

Might one not say, on seeing the long face the master pulls, the trembling of his fleshless fingers unpicking the gold coins, that one looked upon a thief caught in the act and forced, with a pistol at his throat, to render to God what he’d won with the Devil’s assistance?

My florin that you examine, with distrust, through your magnifying glass shows less equivocation and suspicion than your little grey eye, smoking like a poorly-quenched lantern.

The portable scales have returned to their lacquer box with its glowing Chinese figures, Messire Blasius has half risen from his armchair upholstered with Utrecht velvet, and I, bowing to the ground, exit backwards, the poor schoolboy from Leiden with openwork stockings and breeches.

The Flemish School – IV: The Pointed Beard

‘If our heads aren’t held high,

Our beards curly, say I,

Moustache proud and spry,

Ladies scorn us, and sigh.’

Charles d’Assoucy, Poems.

Now, it was a holy day in the synagogue, which was dimly starred with silver lamps, and the rabbis, in robes and spectacles, were kissing their Talmuds, mumbling, muttering, spitting or blowing their noses, some seated, others not.

And suddenly, among the crowd of many rounded, oval, and square beards, which foamed, curled, and exhaled amber and benzoin, a pointed beard attracted notice.

A scholar named Elebotham, crowned with a flannel turban that sparkled with precious stones, stood up and cried: ‘Profanation! There’s a pointed beard here!’

— A Lutheran beard! — A short cloak! — Slay the Philistine.’ — And the tumultuous onlookers, stamped with anger in their pews, while the priest bellowed: — ‘Samson, lend me your donkey’s jaw!’

But the knight, Melchior, had produced an authentic parchment with the Imperial coat-of-arms: —'Order,’ it read, ‘for the arrest of the butcher Isaac van Heck, to be hanged as a murderer; a swine of Israel, between two swine of Flanders.’

Thirty halberdiers detached themselves, with a ponderous clicking of the feet, from the corridor’s shadows. ‘To Hell with your halberds!’ sneered Isaac the butcher. – And hurled himself from a window into the Rhine.

The Flemish School – V: The Tulip-Seller

The tulip is, among the flowers,

what the peacock is, among birds.

One lacks scent, the other voice;

the one takes pride in her dress,

the other takes pride in his tail.

The Garden of Rare and Curious Flowers.

Not a sound, except the rustling of sheets of vellum under the fingers of Doctor Huylten, who only took his eyes from his Bible, strewn with Gothic illuminations, to admire the gold and purple of a pair of fish imprisoned between the damp sides of a jar.

The hinged sides of the doors rolled open: it was a florist who, his arms loaded with several pots of tulips, apologized for interrupting the reading of so learned a person.

— ‘Master,’ he said, ‘here is the treasure of treasures, the wonder of wonders, the sort of flower-bulb of which only one blooms each century in the seraglio of the Emperor of Constantinople!’

— ‘A tulip!’ the angry old man cried, ‘A tulip! That symbol of the pride and the lust which engendered, in the miserable city of Wittenberg, the detestable heresies of Luther and Melanchthon!’

Master Huylten stapled the clasp of his Bible, returned his spectacles to their case, and drew back the curtain over his window, to reveal, in the sunlight, a passion-flower with its crown of thorns, its sponge, its whip, its nails, and the five wounds of Our Lord.

The tulip-seller bowed respectfully, and in silence, disconcerted by an inquisitive look from the Duke of Alba, whose portrait, a masterpiece à la Holbein, hung on the wall.

The Flemish School – VI: The Fingers of One Hand

An honest family in which

there was never a bankruptcy,

and no one at all was ever hanged.

The Lineage of Jean de Nivelle.

The thumb is this fat Flemish innkeeper, of a mocking and ribald humour, who smokes on his doorsill, beneath a sign promoting double-strength ‘Spring’ beer.

The index-finger’s his wife, a virago as dry as a hake, who from morning to night beats her servant of whom she’s jealous, and caresses the bottle with which she’s in love.

The middle-finger’s their son, a fellow hewn with an axe, who’d be a soldier if he wasn’t a brewer, and a horse if he wasn’t a man.

The ring-finger’s their daughter, the nimble, annoying Zerbine, who offers lace to the ladies but won’t offer smiles to their cavaliers.

And the little-finger’s the Benjamin of the family, a crying brat, always clutching at his mother’s belt like a little child hanging from the fangs of an ogress.

The hand’s five fingers form the most fantastic five-leaved wallflower that ever embroidered the flowerbeds of the noble city of Harlem.

The Flemish School – VII: The Viola da Gamba

He recognized, without doubt, the pale face

of his intimate friend Jean-Gaspard Dehureau,

grand buffoon of the Théâtre des Funambules,

who regarded him with an indefinable look

of malice and bonhomie.

Théophile Gautier, Onuphrius.

‘All in the bright moonlight,

My good friend Pierrot

Lend me your pen to write

Just a word or so.

My candle’s dead, I say,

My fire is no more;

For the love of God, I pray,

Open wide the door.’

The Popular Song – ‘Au claire de la lune’.

The choirmaster had barely addressed the sounding viol with his bow when it responded, as if it had indigestion in its belly from some Italian comedy, with a farcical gurgle of florid and risible sounds.

At first it seemed the duenna, Barbara, was scolding that imbecile of a Pierrot, for having, maladroitly, dropped Monsieur Cassandre’s wig-box, and spilt the powder all over the floor.

Then it was Monsieur Cassandre, picking up his wig, most pitifully, as Harlequin kicked the idiot in the behind, Columbine wiped away a tear of mad laughter, and Pierrot’s floury grimace widened from ear to ear.

But not long after, in the moonlight, Harlequin, whose candle had died, was begging his friend Pierrot to open the door and grant him some light, which he did, that traitor, and kidnapped the girl along with the old man’s casket.

— ‘To the Devil with Job Hans, the instrument-maker who sold me that E-string!’ cried the choirmaster, returning the dusty viol back to its dusty case. — The string had broken.

The Flemish School – VIII: The Alchemist

Our art is learned in two ways, that is to say through a master’s teaching,

mouth to mouth, not otherwise; or by divine inspiration and revelation;

or equally from books, many of which are obscure and confusing;

such that to find agreement and truth in them it is necessary

to be subtle, patient, studious, and vigilant.

Pierre Vicot, Key to the Secrets of Philosophy.

Nothing yet! — For three days and nights, have I leafed, in vain, through the hermetic books of Raymond Lulle, by the lamp’s dim light.

No, not a thing, except the hissing of the glittering retort, and the mocking laughter of a salamander that makes a game of troubling my meditations.

Sometimes it sets my beard aflame, sometimes it shoots a fiery bolt from a crossbow into my robe

Or if it polishes its armor, ashes from the furnace blow over the pages of my formula, and into the ink on my writing desk.

And the ever-more-glittering retort hisses the same tune as the Devil does when Saint Eloi pinches his nose in his forge.

But nothing yet! — For three more days and nights I’ll leaf through the hermetic books of Raymond Lulle by the lamp’s dim light!

The Flemish School – IX: Leaving for the Sabbath

She rose at night, and, lighting the candle,

took a box and anointed herself,

then with a few words she was transported to the Sabbath.

Jean Bodin, Démonomanie des Sorciers.

A dozen of them were eating soup and drinking beer, each with the bone of a dead man’s forearm to use as a spoon. The fireplace shone red with embers, the candles were fading to smoke, and the plates gave off the smell of a ditch in spring.

And when Maribas laughed or wept, you heard the groan of a bow on the three strings of a dilapidated violin.

Meanwhile the paid-help spread open, diabolically, on the table, by the light of the tallow, a book of spells on which a roasted fly frolicked.

This fly was still buzzing when, dragging its enormous, hairy belly, a spider climbed the edge of the magical folio.

But the wizards and witches had already flown up the chimney, some astride brooms, some on pokers or tongs, and Maribas on the frying-pan’s tail.

Gaspard de la Nuit: Book Two

Here begins the second

Book of the Fantasies

Of Gaspard

De la

Nuit

Old Paris – I: The Two Jews

‘Sixty or more,

Jealous old bore,

Husband, be sure

To bolt the door.’

Old Song.

Two Jews, who had halted beneath my window, were counting, mysteriously, the slow hours of the night on their fingertips.

— ‘You have money, Rabbi?’ the younger asked of the older. ‘It’s not a bell, this purse,’ replied the other.

But then a crowd of folk rushed noisily from the neighboring dens; their cries bursting over my stained-glass windows like a silvery flood from a pipe.

They were thievish beggars who ran joyously towards the Market Square, from which the wind blew burning straw and a scorched odour.

— ‘Oh! Oh! Lanturelu!’ — ‘My reverence to Madam Moon!’ — ‘This way goes the Devil’s cowl! Two Jews outside during curfew!’ — ‘Beat them! Beat them! Daylight for Jews, night-time for beggars!’

And the cracked bells chimed, on high, from the Gothic towers of Saint-Eustache: ‘Ding-dong, ding-dong, sleep on, ding-dong!’

For Monsieur Louis Boulanger, painter

Old Paris – II: The Beggars

‘I endure

Cold and more;

Tough, for sure.’

The Song of a Poor Devil.

— ‘Ah! Sort yourselves, so we can get warm!’ — ‘All you need do is straddle the fire! This clown has legs like pincers.’

— ‘One o’clock!’ — ‘The wind’s howling! Know you, my screech-owls, what makes the moon so bright? It’s cuckolds’ horns they’re burning.’

— ‘Red embers flare in the coals!’ — ‘How the flame on them dances blue! Oh! Who’s the rascal whose beating his rascal?’

— ‘My nose is frozen!’ — ‘My ears are roasted!’ — ‘Can you see aught in the fire, Choupille?’ — ‘Yes, a halberd!’ — ‘And you, Jeanpoil?’ — ‘An eye’.

— ‘Make way, make way for Monsieur de la Chousserie!’ — ‘Are you there, Mister Prosecutor, warmly furred and gloved for the winter!’ — ‘Yes, it’s true! Tomcats don’t get frostbite!’

— ‘Ah, here are the Gentlemen of the Watch!’ — ‘Your boots are steaming.’ — ‘The cloak-snatchers? We killed two of them with our arquebuses; the others escaped across river.’

And so, at the fire that night, the beggars were joined by a gallivanting parliamentary prosecutor and the Gascon Gentlemen of the Watch who recounted, unsmilingly, the exploits of their worn-out arquebuses.

Old Paris – III: The Lantern

The Mask. — ‘It’s dark;

lend me your lantern.’

Mercurio. — ‘Bah! cats have

two eyes to light them.’

Carnival Night.

Ah! Why did I, little guttersnipe that I am, think there was room this evening to hide from the storm in Madame de Gourgouran’s lantern!

I laughed to hear some sprite, soaked in the downpour, buzzing around the bright mansion, unable to find the door through which I’d entered.

In vain, complaining hoarsely, he begged me to allow him at least to relight his ‘cellar-rat’ candlestick from my candle to find his way.

Suddenly the lantern’s yellow paper ignited, shattered by a gust of wind, that caused the street-signs hanging like banners to creak and groan.

— ‘Jesus! Have mercy!’ cried the Beguine, crossing herself with the fingers of one hand. ‘Devil take you, witch,’ I cried, spitting more sparks than a serpentine firework.

Alas! I, who, again, this morning, rivalled in grace and adornment the goldfinch with earflaps of scarlet cloth, the pet of the young Lord of Luynes!

Old Paris – IV: The Tour de Nesle

Paris with Tour St. Jacques and Notre Dame at evening

Anton Melbye (1818–1875) - SMK.Open

There was a guardhouse in the Tour de Nesle

in which the watch lodged at night.

Brantome (Pierre de Bourdeille), .

‘Jack of Clubs! — Queen of Spades, to win!’ And the soldier, who lost, sent his stake flying to the floor as he punched the table.

But then Messire Hugues, the provost, spat into an iron brazier with the grimace of a beggar who has swallowed a spider while eating his soup.

— ‘Ugh! Are the pork-butchers scalding their pigs at midnight? God’s belly! There’s a boatload of straw burning on the Seine!’

The fire, which at first was just an innocent will-o’-the-wisp lost in the mists of the river, soon made the devil of a noise like a volley of cannon-fire and that of violent arquebusades across the water.

An innumerable crowd of thievish rascals, beggars on crutches, heretics all, rushed to the shore, dancing a jig in front of the spirals of smoke and flame.

Which reddened the face of the Tour de Nesle, from which the watch emerged shouldering carbines; and the Tour du Louvre, from whose windows, the king and queen saw all, without being seen.

Old Paris – V: The Model of Refinement

A show-off

A refined fellow

The Poetry of Scarron.

‘Each bar of my moustache, shaped to a point, is like the tail of a monstrous lizard, my linen white as the restaurant’s tablecloths, my waistcoat no older than the crown wallpaper.

Would you ever imagine, given my dapper appearance, that lodged in my stomach, hunger — the executioner’s wife! — pulls on the rope there and strangles me like a man being hung!

Oh, if only a roast fowl had fallen into the crown of my hat, from that window, where the gaslight crackles, to replace these withered flowers!

The Place Royal, this evening, is as bright with its lights as a chapel! — ‘Clear the rubbish away! — Fresh lemonade! — Naples Macaroons!’ — Now, my friend, let me taste your trout in herb sauce with my finger! How droll! Your April Fool’s jest lacks spice.

Is that not Marion Delorme on the Duke of Longueville’s arm? Three little long-haired dogs follow her, yapping. Her eyes are fine diamonds, that young courtesan! — His nose bears fine rubies, that old courtier!’

And the model of refinement stood fist on hip, elbowing the men passing by, smiling at the ladies. He’d had nothing to eat; he’d purchased a bunch of violets instead.

Old Paris – VI: The Evening Office

When, at Christmas or Easter, the church at evening,

Is filled with confused footsteps, and candles flaring.

Victor Hugo, The Songs of Twilight.

Dixit Dominus Domino meo: sede a dextris meis.

The Lord said to my Lord, sit thou at my right hand.

The Office of Vespers.

Thirty monks, poring, leaf by leaf, through Psalters as soiled as their beards, praised God and sang the Devil to scorn.

— ‘Madame, your shoulders are banks of lilies and roses’. As the rider leant down, he blinded his servant in the eye with the tip of his sword.

— ‘Joker,’ she simpered, ‘do you seek to distract me?’ — ‘Is that the Imitation of Christ that you read Madame?’ — ‘No, it’s the Game of Love and Gallantry.’

But the service was done. She closed her book and rose from the chair. ‘Let’s go,’ she said, ‘enough prayers for one day!’

And I, a pilgrim, kneeling to one side below the organ, seemed to hear the angels descending melodiously from heaven.

I received, from afar, a drift of perfume shed by the censer, and God allowed me to glean the poor man’s ear of corn, after such rich harvest.

Old Paris – VII: The Serenade

At night, all cats are grey.

Popular Proverb.

A lute, a bass guitar and an oboe. A discordant, ridiculous symphony. Madame Laure on her balcony, behind a blind. No lanterns in the street, no lights in the windows. A horned moon.

— ‘Is it you, d’Espignac?’ — ‘No, alas!’ — ‘So, it’s you, little Fleur d’Amande?’ — ‘Neither one nor the other’ — ‘What! You again, Monsieur de la Tournelle? Bonsoir! Go make trouble elsewhere.’

The Musicians in capes: ‘Monsieur the Counsellor’s set for a cold. Has he no fear of the husband?’ — ‘Oh, the husband’s in the West Indies!’

And what were those two whispering together? ‘A hundred louis a month’ — ‘I’m charmed!’ — ‘A carriage and pair’ — ‘Superb!’ — ‘A manse in the princes’ quarter!’ — ‘Magnificence, indeed!’ — ‘And my heart full of love! — ‘Oh, that pretty slipper fits my foot!’

The Musicians still in their capes: ‘I can hear Madame Laura laughing’ — ‘That cruel flirt grows almost human’ — ‘Yes! Orpheus’s art seduced tigresses in days of old!’

Madame Laura: ‘Come closer, my darling boy, so I can slip you my key, tied in a ribbon!’ But the counsellor’s wig was wetted with dew not distilled by the stars. ‘Now, Gueudespin!’ cried the naughty cocotte, shutting the balcony doors: ‘Run quickly, find me a whip to dry Monsieur!’

Old Paris – VIII: Messire Jean

A grave personage whose gold chain

and white wand intimated his authority.

Walter Scott, The Abbot, Chapter IV.

— ‘Messire Jean,’ said the queen, ‘go and see why those two greyhounds are fighting each other in the palace yard!’ And off he went.

When he arrived, the seneschal was scolding the greyhounds who fought over a ham-bone.

But, pulling at his black breeches, and biting his red stockings, they toppled him as easily as a gouty man on crutches.

— ‘Help! Help! Aid me!’ And the guards at the gate, came running bearing their polearms, the muzzles of the two hollow-flanked creatures having already searched the good fellow’s tasty codpiece.

Meanwhile the queen was fainting with laughter at a window, in her tall Mechlin-lace wimple as stiff and pleated as a fan.

— ‘And why were they fighting, sir?’ — ‘They were fighting, Madame, because the one maintained, contrary to the other, that you are the most beautiful, wisest, and greatest princess in the universe.’

For Monsieur Sainte-Beuve

Old Paris – IX: Midnight Mass

‘Christus natus est nobis;

venite, adoremus.’

‘Christ is born to us;

Come, let us adore him.’

The Nativity of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

‘We’ve neither fire nor station.

Grant us the Lord’s portion.’

Old Song.

The good lady and noble lord of Chateauvieux were breaking the evening bread, and the chaplain blessing the food, when the clattering of clogs was heard at the door. Here came the little children, carol-singing.

— ‘Good lady of Chateauvieux, hurry now, people are off to church; hurry now, lest the candle, which burns on your prie-dieu in the chapel of the Angels, dies, and scatters its drops of wax on the Book of Hours’ vellum, and the shelf’s velvet! — There’s the first peal of bells for midnight mass!’

— ‘Noble Lord of Chateauvieux, hurry now, lest the Lord of Grugel, who is passing-by with his paper lantern, seizes, in your absence, the place of honour on the bench of the confreres of Saint-Antoine! — There’s the second peal of bells for midnight mass!’

— ‘Monsieur the Chaplain, hurry now! the organ’s roaring, the canons are chanting, hurry, the faithful are gathered and you still at table! — There’s the third peal of bells for midnight mass!’

The little children blew on their fingers, but they’d not long to wait, and on the Gothic threshold, white with snow, the chaplain gave them each, in the name of the masters of the house, a griddle-cake and a silver coin.

Now the bells no longer rang. The good lady plunged her arms up to her elbows in a muff, the noble sire smothered his ears beneath his cap of state, and the humble priest, in his hooded shoulder-cape, walked behind them, his missal under his arm.

Old Paris – X: The Bibliophile

An Elzevir edition roused in him

sweet emotions; but what plunged

him into ecstatic rapture was one

that was printed by Henri Etienne.

Biography of Martin Spickler.

It wasn’t some painting of the Flemish school, a David Teniers, or a Breughel the Younger, so darkened by smoke not a devil could be seen.

It was a manuscript nibbled by rats at the edges, with involved writing, and blue and red ink.

— ‘I suspect this author,’ the bibliophile said, ‘lived near the end of Louis XII’s reign, that king of rich paternal instincts.’

‘Yes,’ he murmured with a serious and meditative air, ‘yes, he’ll have been a clerk, in the household of the lords of Chateauvieux.’

Here, he leafed through a massive folio entitled The Nobility of France, in which he found only the lords of Chateauneuf mentioned.

— ‘No matter,’ said he, a little confused, ‘Chateauneuf, Chateauvieux, new or old, it’s the same chateau. Just as it’s time to rename the Pont-Neuf, Pont-Vieux.’

Gaspard de la Nuit: Book Three

Here begins the third

Book of the Fantasies

Of Gaspard

De la

Nuit

Night and its Enchantments – I: The Gothic Chamber

Nox et solitudo plenae sunt diabolo.

At night my room is full of devils.

The Church Fathers.

‘Oh, the earth,’ I murmured to the night, ‘is an embalmed calyx whose pistil and stamens are the moon and stars!’

And, with eyes heavy with sleep, I closed the window inlaid with a Calvary cross, black against the yellow halo of the stained-glass pane.

Still, — if only it were not midnight, — the hour emblazoned with dragons and devils! — the gnome who gets drunk on the oil from my lamp!

If it were only the nurse rocking a stillborn infant, in my father’s cuirass, to her monotonous song!

If it were only the mercenary’s skeleton prisoned in the woodwork, his forehead touching his elbow and knee!

If it were only my ancestor descending on his own two feet from his worm-eaten picture-frame to dip his gauntlet into the fount’s holy water.

But it’s Scarbo, the goblin, who bites my neck and cauterizes the blood-stained wound, by plunging his iron finger, red from the furnace, within!

Night and its Enchantments – II: Scarbo

‘God, grant me at the hour of my death,

A praying priest, the cloth for a shroud,

A pinewood coffin, and a dry grave.’

The Paternosters of Monsieur le Maréchal.

‘Whether you die absolved or damned,’ Scarbo muttered that night, in my ear, ‘your shroud will be a spider’s web, and I’ll bury the spider with you!’

— ‘Oh, grant me at least, for a shroud,’ I replied, my eyes red from weeping so, ‘an aspen leaf in which the lake’s murmurs will cradle me.’

— ‘No,’ — sneered the mocking gnome — ‘you’ll be food at eve for the snail that hunts dead midges made blind by the setting sun!’

‘So, you’d rather,’ I replied, eyes still filling with tears, ‘you’d rather see me sucked up by that tarantula with an elephant’s trunk?’

‘Well,’ he added, ‘console yourself; your shroud will be gold-spotted strips of snake-skin, with which I’ll swaddle you like a mummy. And from the dark crypt of St-Bénigne, where I’ll stand you upright against the wall, you’ll be able to listen, at leisure, to the children weeping in limbo.’

Night and its Enchantments – III: The Madman

‘A golden coin of King Charlemagne, dear sir,

Or a Golden Lamb of King John, if you prefer.’

Manuscripts in the Royal Library.

The moon disentangled her hair with an ebony comb, silvering the hills, meadows, and woods with a shower of glow-worms.

On the roof, Scarbo, the gnome, whose treasures abound, winnowed, to the cry of the weather vane, ducats and florins leaping in rhythm, the counterfeit coins littering the street.

How that madman sneered, roaming the empty city each night, one eye on the moon and the other — punctured!

— ‘Perish the moon!’ he grumbled, gathering the devil’s tokens, ‘I’ll buy a pillory and warm myself in the sun!’

But the moon, the setting moon, still shone — and Scarbo in my cellar, silently minted florins and ducats to the strokes of a pendulum.

While, with its outstretched horns, a snail, wandering the night, sought its path on my luminous stained-glass window.

Night and its Enchantments – IV: The Dwarf

‘You, on horseback!’ ‘And why not then?

I’ve oft-times ridden a greyhound’s back;

Twas the bitch of the Laird of Linlithgow.’

Scottish Ballad.

I captured from my seat, in the shadow of the curtains, this furtive moth hatched from a ray of moonlight or a drop of dew.

A quivering insect which, to free its captive wings from between my fingers, paid me a ransom in fragrances!

The errant creature, suddenly, flew away, to leave in my lap — oh, horror! — a deformed and monstrous larva with a human head!

— ‘Where is your soul, for me to ride!’ — ‘My soul, lame and sore from the day’s weariness, now rests on the golden litter of dreams.’

It escaped in fear, my soul, through the livid spider’s-web of twilight, over the black horizon, jagged with black Gothic bell-towers.

But the dwarf, hanging upon its neighing flight, rolled like a spindle among the wisps of its white mane.

Night and its Enchantments – V: Moonlight

‘Awake, all those that sleep aright.

Pray for those that died this night.’

The Night Watchman’s Cry.

Oh, how sweet it is, as the hour chimes in the bell-tower at night, to gaze at the moon whose nose seems like a golden coin of Charlemagne’s!

Two beggars were whining under my window, a dog howled at the crossroads, and the cricket on the hearth was chirping quietly.

But soon my effort to hear was answered only by deep silence. The lepers had returned to their kennels, to the sound of Jacquemart beating his wife.

The dog had gone down an alley, in front of the guards’ polearms rusted by rain and chilled by the wind.

And the cricket had fallen asleep, as soon as the last spark had emitted its last glow in the ashes of the hearth.

And it seemed to me — so bemusing is a fever — that the moon, its face a grimace, thrust out its tongue at me like one who’s been hanged!

For Monsieur Louis Boulanger, painter

Night and its Enchantments – VI: The Dance Under the Belltower

The cemetery gate (the churchyard)

Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) - Wikimedia Commons

It was a heavy building, almost square,

surrounded by ruins, whose principal tower

which still possessed its clock,

dominated all the neighborhood.

Fenimore Cooper.

Twelve magicians danced a round-dance under the tall belltower of Saint-Jean. They evoked the storm one after the other, and from the depths of my bed I counted, with horror, twelve voices which traversed the darkness in turn.

At once, the moon hastened to hide behind the clouds, and a rainstorm mingled with lightning and whirlwinds lashed at my window, while the weathervanes cried like a flock of cranes standing sentinel over those who burst through the woodland downpour.

The upper-string of my lute, hanging from the partition, snapped; my goldfinch beat its wings against its cage; and some questing spirit turned over a leaf of the Roman de la Rose which lay sleeping on my desk.

But suddenly lightning roared on the summit of Saint-Jean. The enchanters swooned, struck dead, and I saw from afar their books of magic spells burning like torches in the black bell tower.

That fearful glow painted the walls of the Gothic church with the red flames of hell and purgatory, and cast the gigantic statuesque shadow of Saint John onto the neighboring houses.

The weather vanes rusted; the moon melted the pearl-grey clouds; the rain fell only drop by drop from the edges of the roof, and the breeze, opening my half-closed window, threw on my pillow flowers of my jasmine shaken loose by the storm.

Night and its Enchantments – VII: A Dream

I’ve dreamed again and again,

But understood not a word.

Pantagruel, Book III.

It was the depths of night. Firstly, I saw — and what I saw, I relate — an abbey, its walls pierced by moonlight —a forest intersected by winding paths — and the Morimont, Dijon’s place of execution, teeming with capes and hats.

Then I heard — and what I heard, I relate — the funereal toll of a bell to which a funereal sobbing from the prison replied — plaintive cries and ferocious laughter that shook every leaf on the trees — and the murmured prayers of the black-clad penitents who accompany the criminal to execution.

Lastly, I dreamed — and the end of my dream, I relate — of a dying monk lying among the ashes of the dying — a young girl struggling, hanged from the branch of an oak-tree — and myself, disheveled, bound by the executioner to the spokes of the wheel.

Dom Augustin, the dead prior, dressed in Franciscan garb, will receive the ardent honours of the chapel; Marguerite, slain by her lover, will be buried in the white dress of innocence, four wax candles about her.

But as for myself, the executioner’s iron-bar broke like glass, at the first blow; the black-clad penitents’ torches were quenched by a torrent of rain, and the crowd flowed away with its swift overflowing streams — while I chased other dreams towards my waking.

Night and its Enchantments – VIII: My Great-Grandfather

All in that room was still in the same state,

except that the tapestries were in shreds,

and spiders wove their webs in the dust.

Walter Scott.

The venerable characters on the Gothic tapestry, stirred by the wind, saluted each other, and my great-grandfather entered the room — my great-grandfather who died nigh-on eighty years ago!

There — before the prie-dieu — he knelt, my great-grandfather the counsellor, his beard kissing that yellowed missal spread open at the place marked by a ribbon.

All night, he muttered prayers, without uncrossing his arms from his purple silk mantle for a moment, or casting a single glance towards me, his posterity, who lay on his bed, his dusty four-poster bed!

And I noticed with horror that his eyes were empty, though he seemed to be reading — that his lips were motionless, though I heard him praying — that his fingers were fleshless, though they glittered with precious gems!

And I wondered if I was awake or sleeping — if the pallid light was that of the moon or Lucifer — if it was midnight or dawn!

Night and its Enchantments – IX: Ondine

‘………………………I thought I heard,

Enchanting sleep, some vague harmony,

As like murmurings rose, all about me,

Songs, weaving many a sad tender word.’

Charles Brugnot, Les deux Génies.

— ‘Listen! — ‘Listen! — It is I, Ondine, who brushes with drops of water your window’s sonorous panes lit by the dim rays of the moon; and there, in her silk moiré dress, is the lady of the manor, who contemplates from her balcony, the beauty of the starry night, and of the slumbering lake.

Every wave’s an Ondine swimming the current, each current a path that winds towards my palace, and my palace is built of water, on the floor of the lake, in a triangle of fire, earth and air.

Listen! — Listen! — My father beats the frog-loud surface with a branch of green alder, and my sisters caress with arms of foam fresh islands of reeds, irises, water lilies, or laugh at the bearded weeping-willow fishing the stream.’

Murmuring her song, she begged me to set her ring on my finger, to wed an Ondine and visit her palace, there to be king of the lake.

But when I replied that I loved a mortal, sulking and disappointed, she wept a few tears, gave a burst of laughter, and vanished in showers of water, streaming white down my stained-glass windows tinted with blue.

Night and its Enchantments – X: The Salamander

He threw some sacred holly-leaves

Into the fire, that crackled and burned.

Charles Nodier, Trilby.

— ‘Grillon, my friend, are you dead; deaf to the sound of my whistling, blind to the light of the fire?’

But the cricket, however affectionate the salamander’s words, failed to respond, either sleeping a magical sleep or else choosing to sulk.

‘Oh, sing me your evening song in your angle of ashes and soot, behind the iron plate, emblazoned with three heraldic fleurs-des-lys!’

But the cricket still failed to reply, and the salamander, weeping, sometimes listened as if to something other than his voice, sometimes hummed with a varied flame, in pink, blue, red, yellow, violet, and white.

‘He’s dead, he’s dead, the cricket, my friend!’ And I listened to sighs and sobs, as the flame, now livid, grew less in the saddened hearth.

‘He’s dead! And since he’s dead, I wish to die!’ All the branches of vine were consumed, and the flame dragged itself across the embers, bidding farewell to the hearth, as the salamander died of inanition.

Night and its Enchantments – XI: The Sabbath Hour

‘Who passes through the vale so late?’

Henri de Latouche, The King of the Alders.

It’s here! And already, in the depths of the thickets barely lit by the phosphoric eye of the wild cat lurking below the branches;

On the flanks of the rocks soaking their brushwood hair in precipitous night, streaming with dew and glow-worms;

On the banks of the torrent spraying white foam on the fronts of the pines, drizzling grey vapour on the fronts of the chateaux;

There gathers an innumerable crowd, which the old woodcutter, lingering on his way, a load of wood on his back, hears but cannot see.

And from oak to oak, from mound to mound, a thousand confused, lugubrious, frightening cries echo: ‘Hum! Hum!’ — ‘Schup! Schup!’ — ‘Cuckoo! Cuckoo!’

Here’s the gallows-tree! — And there in the mist a Jew appears, searching for something in the damp grass, by the golden glow of a hand of glory.

Gaspard de la Nuit: Book Four

Here begins the fourth

Book of the Fantasies

Of Gaspard

De la

Nuit

The Chronicles – I: Master Ogier (1407)

The said king, Charles VI by name,

Was most debonair, and much loved,

The people hating with great hatred

The Dukes of Orléans and Burgundy,

Who imposed excessive taxes

Throughout the whole kingdom.

The Annals and Chronicles of France from the Trojan War to Louis XI, by Master Nicolle Gilles.

— ‘Sire,’ Master Ogier asked the king, who was looking through the small window of his oratory at old Paris brightened by a ray of sunshine, ‘do you hear those greedy sparrows frolicking in the courtyard of your Louvre in that branched and leafy vine?

— ‘Yes, indeed!’ answered the king, ‘it’s a most diverting sound.’

— ‘The vine is in your garden; yet you’ll not gain from the harvest,’ replied Master Ogier, with a benign smile. ‘Sparrows are bold thieves, and so pleased by their pecking they’ll peck away forever. They’ll harvest your vineyard for you.’

— ‘Oh, no, my friend! I’ll chase them off!’ cried the king!’

He set the ivory whistle to his lips, the whistle that hung from a ring of his gold chain, and drew from it sounds so shrill and piercing that the passerines flew to the eaves of the palace.

— ‘Sire,’ said Master Ogier, ‘allow me to deduce a moral from this. The sparrows are your nobles, the vine is the people. The former feast at the expense of the latter. Sire, who cheats the servant, cheats the master. Enough of their depredations! Blow your whistle, and harvest your grapes yourself.’

Maître Ogier rolled the crown of his cap between his fingers with an embarrassed air. Charles VI shook his head sadly, extending his hand to the burgher of Paris: — ‘You’re a wise man!’ he sighed.

The Chronicles – II: The Postern Door to the Louvre

This elvish Dwarf………………...

He was waspish, arch, and litherlie,

But well Lord Cranstoun served he.

Walter Scott, The Lay of the Last Minstrel.

The little light had crossed the frozen Seine, beneath the Nesle tower, and now was only a hundred yards away, dancing amidst the fog, oh infernal prodigy, with a tinkling sound like mocking laughter.

— ‘Who goes there?’ cried the Swiss guard at the window of the Louvre’s postern.

The little light hastened to approach, in no hurry to respond. But soon the figure of a dwarf appeared, dressed in a tunic with spangles of gold, wearing a cap with a silver bell, a feeble red light shining through the glazed diamond panes of the lantern he swung in his hand.

‘Who goes there?’ the Swiss guard repeated in a trembling voice, raising his arquebus.

The dwarf quenched the light of his lantern, and the guard made out his gaunt and wrinkled features, the eyes shining with mischief, the beard white with frost.

‘Oho! Oho! My friend, take care not to fire your weapon. Come, come! God’s blood! You breathe ever death and carnage!’ cried the dwarf in a voice no less concerned than that of the guard.

— ‘Friend, yourself! Ouf! Who are you then?’ asked the Swiss, somewhat reassured. And he placed the fuse of his arquebus back in his iron helm.

— ‘My father is King Nacbuc and my mother Queen Nacbuca. Ioup! Ioup! Iou!’ replied the dwarf, sticking out his tongue and pirouetting twice on one foot.

At this, the soldier’s teeth chattered. Happily, he recalled he’d a rosary hanging from his ox-hide belt.

— ‘If your father is King Nacbuc, paternoster, and your mother Queen Nacbuca, qui es in coelis, are you the devil then, sanctificetur nomen tuum?’ he stammered, half dead with fright.

— ‘Oh no!’ cried the lantern holder, ‘I’m the dwarf of Monseigneur the king, come this night from Compiègne, who hurries ahead to open the postern door of the Louvre. The password is: Lady Anne of Brittany and Saint Aubin of Cormier.’

The Chronicles – III: The Flemings

The Flemings, a people mutinous and stubborn.

The Memoirs of Olivier de la Marche.

The battle had lasted nine months, when the army of Bruges yielded, turning their backs on the fight. There ensued, on the one hand, such deep disarray, and, on the other, such fierce pursuit, that in crossing the bridge a good number of rebels collapsed, pell-mell, men, standards, and carts, into the river.

Next day the Count entered Bruges with a wondrous throng of knights. His heralds preceded him, sounding their trumpets loudly. The plunderers, dagger in hand, ran here and there, while before them fled the frightened swine.

The neighing cavalcade was headed towards the town hall. There the mayor and aldermen knelt, calling for mercy, hooded capes in the dust. But the count had sworn, two fingers on the Bible, to slay the red boar in its wallow.

— ‘My lord!’

— ‘Let the city be burned!’

— ‘My lord!’

— ‘Let the burghers hang!

One city district alone was set on fire, the militia captains alone were hung from the gallows, and the red boar erased from the banners. Bruges had bought its safety for a hundred thousand gold crowns.

The Chronicles – IV: The Hunt (1412)

‘Let us go chase the deer a while,’ said he.

Unpublished Poems.

And the hunt was away, away, the day being bright, by hill and dale, through wood and field; the varlets running, the horns blaring, the dogs barking, the hawks flying, and the two cousins riding side by side, piercing deer and wild boars with their spears midst the undergrowth, and, with their crossbows, herons and storks in the air.

— ‘Cousin,’ said Hubert to Regnault, ‘it seems to me, though we sealed our peace this morning, you are not yet in good spirits?

— ‘Yes, indeed!’ he replied.

Regnault possessed the red eyes of the mad or the damned; Hubert was anxious; as the hunt went forever away, away, the day being bright, by hill and dale, through wood and field.

But, all of a sudden, a troop of foot-soldiers, concealed in a faerie glade, rushed, lances lowered, upon the joyous hunt. Regnault unsheathed his sword, but only — cry horror! — to pierce, with several blows, the body of his cousin who fell from his horse.

— ‘Kill, kill!’ shouted that Ganelon.

Our Lady, have pity! — And the hunt coursed away by hill and dale, through wood and field, no more, though the day was bright.

With God may the soul of Hubert rest, the Sire de Maugiron, pitifully slain, on the third of July, in the year fourteen hundred and twelve; and the Devil take the soul of Regnault Sire de l’Aubépine, his murderer, and cousin! Amen.

The Chronicles – V: The Retreat-Seekers

Now, one day Hilarion was tempted by a female demon

Who presented him with a cup full of wine and flowers.

The Lives of the Desert Fathers.

Three females, dressed in black, skirts hitched like gypsies, pretended, by way of a ruse, to be seeking spiritual retreat at the monastery-door at midnight.

— ‘Hello, there! Hello!’

One of the three, stood upright in the stirrups.

— ‘Hello! Give us shelter from the storm! Are you wary? Open the door! Are we, the charming trio these cruppers bear, with these little wine-sacks that hang from our shoulder-straps, other than girls of fifteen with wine to drink?’

— The monastery seemed asleep.

— ‘Hello, there! Hello!’ cried one of them, shivering with cold.

— ‘Hello! A lodging, in the name of our Saviour’s blessed Mother! We’re pilgrims astray. The glass of our reliquaries here, the rims of our hoods, the folds of our cloaks are streaming with rain, and our horses, stumbling from weariness, have lost their shoes on the road.’

A light shone from a crack in the midst of the door.

— ‘Be gone, you demons of night!’ cried the prior and his monks, there in procession, armed with their candles.

— ‘Be gone, daughters of lies! If you’re flesh and blood, and not ghosts, God forbids us from harboring pagans, or schismatics at least, among us!

— ‘Be gone! Be gone!’ — cried the shadowy riders — ‘Be gone! Be gone!’ And the sound of their horses’ hooves was swept far off by a whirlwind of air, midst river and woods.

— ‘To deny fifteen-year-old sinners so, whom we might have induced to confess!’ grumbled a young fair-headed monk with the cheeks of a cherub.

— ‘Brother!’ the abbot murmured in his ear, ‘You forget that Madame Eleanor and her niece are waiting above to perform that very thing.’

The Chronicles – VI: The Big Battalions

Urbem ingredientur, in muro

Current, domos conscendent

Per fenestras intrabunt quasi fur.

They shall run to and fro in the city;

they shall run upon the wall,

they shall climb upon the houses;

they shall enter in at the windows like a thief.

The Prophet Joel, Chapter II, 9 (The Vulgate, and the King James Bible).

I

A band of mercenaries, camped in the woods, were warming themselves at a fire, around which the shadows of a ghostly grove thickened.