Charles Baudelaire

Le Spleen de Paris

(Petits Poèmes en prose, 1869)

‘Spleen et Idéal’ - Félix-Hilaire Buhot (French, 1847-1898)

National Gallery of Art

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2024 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction.

- Prologue: To Arsène Houssaye.

- 1. The Stranger (L’Étranger)

- 2. The Old Woman’s despair (Le Désespoir de la vielle)

- 3. The Artist’s confession (Le Confiteor de l’artiste)

- 4. A Jester (Un Plaisant)

- 5. The Dual Room (La Chambre double)

- 6. Everyone their own Chimera (Chacun sa Chimère)

- 7. The Madman and the Statue of Venus (Le Fou et La Vénus)

- 8. The Dog and the Perfume-Bottle (Le Chien et Le Flacon)

- 9. The Wretched Glazier (Le Mauvais Vitrier)

- 10. At One in the Morning (À Une Heure du Matin)

- 11. The Wild Woman and the Little-Mistress (La Femme Sauvage et La Petite-Maîtresse)

- 12. Crowds (Les Foules)

- 13. Widows (Les Veuves)

- 14. The Old Acrobat (Le Vieux Saltimbanque)

- 15: The Cake (Le Gâteau)

- 16: The Clock (L’Horlogue)

- 17. A Hemisphere in a Head of Hair (Un Hémisphère dans une Chevelure)

- 18. The Invitation to the Voyage (L’Invitation au voyage)

- 19. The Poor Child’s Toy (Le Joujou du Pauvre)

- 20. The Fairies’ Gifts (Les Dons des Fées)

- 21. The Temptations, or Eros, Plutus, and Glory (Les Tentations, ou Éros, Plutus et La Gloire)

- 22. The Shadows of Evening (Le Crépuscule de Soir)

- 23. Solitude (La Solitude)

- 24. Projects (Les Projets)

- 25. The Lovely Dorothée (La Belle Dorothée)

- 26. The Eyes of the Poor (Les Yeux des Pauvres)

- 27. A Heroic Death (Une Mort Héroïque)

- 28. The Counterfeit Coin (La Fausse Monnaie)

- 29. The Generous Player (Le Joueur Généreux)

- 30. The Rope (La Corde) – To Édouard Manet

- 31. Vocations (Les Vocations)

- 32. The Thyrsus (Le Thyrse) – To Franz Liszt

- 33. Be inebriated (Enivrez-vous)

- 34. Already (Déjà)

- 35. Windows (Les Fenêtres)

- 36. The Desire to Paint (Le Désir de Peindre)

- 37. The Gifts of the Moon (Les Bienfaits de la Lune)

- 38. Which is Real? (Laquelle est la Vraie?)

- 39. A Racehorse (Un Cheval de Race)

- 40. The Mirror (Le Miroir)

- 41. The Harbour (Le Port)

- 42. Portraits of Mistresses (Portraits de Maîtresses)

- 43. The Gallant Marksman (Le Galant Tireur)

- 44. The Soup and the Clouds (La Soupe et Les Nuages)

- 45. The Shooting-Gallery and the Cemetery (Le Tire et le Cimitière)

- 46. The Lost Halo (Perte d’Auréole)

- 47. Miss Scalpel (Mademoiselle Bistouri)

- 48. Anywhere out of the World (N’importe où hors de Monde)

- 49. Let’s Thump the Poor (Assommons les Pauvres)

- 50. The Good Dogs (Les Bons Chiens) – To M. Joseph Stevens

- Epilogue.

Translator’s Introduction

Baudelaire’s Le Spleen de Paris, also known as Paris Spleen or Petits Poèmes en prose, is a collection of fifty short pieces published posthumously in 1869. The work strongly influenced the modernist movement, in particular Rimbaud’s later prose-poems. Though inspired by Gaspard de la nuit, a work by Aloysius Bertrand, Baudelaire’s texts illustrate the Parisian life of his times, rather than Bertrand’s use of a medieval backcloth, and incorporate a number of themes and titles from Baudelaire’s earlier and more famous collection of poetry, Les Fleurs du mal.

The title of the work refers to the psychological meaning of the word spleen: an ill-tempered disgust with the world. Here, Baudelaire displays his views on good and evil, sin and pleasure, men and women, the artist and the philistine, time and mortality, solitude and the crowd, and much more.

Prologue: To Arsène Houssaye

My dear friend, I am sending you a little work of which one could not say, without doing it an injustice, that it has neither tail nor head, since all is, on the contrary, at once head and tail, in alternating and reciprocal fashion. Consider, I pray you, what an admirable convenience this construction offers us all, yourself, myself, and the reader. We can leave off, wherever we wish, I my reverie, you this manuscript, the reader their reading; for I do not choose to suspend the latter’s restless will with an interminable fine-spun thread of a plot. Remove any vertebra and the two resulting parts of this tortuous fantasy will rejoin themselves effortlessly. Split it into numerous fragments, and you will see that each can exist apart. In the hope that some of these segments will be lively enough to please and amuse you, I dare to dedicate the whole serpentine creation to you.

I have a small confession to make. It was while leafing through, for the twentieth time at last, Aloysius Bertrand’s famous ‘Gaspard de la Nuit’ (has not a book well-known to you and I, and a number of our friends every right to be called famous?) that I had the idea of attempting something analogous, of applying to the description of modern life, or rather of a particular more modern and abstract life, the process which he had applied to the depiction of the life of previous times, so strange to us and picturesque.

Who among us has not, in his days of ambition, dreamed of the miracle of a poetic and musical prose without rhythm or rhyme, flexible and striking enough to be adapted to the lyrical movements of the soul, the undulations of reverie, the leaps of consciousness?

It is above all from frequenting enormous cities, from the intersection of their innumerable relationships that this obsessive ideal is born. Have not you yourself, my dear friend, attempted to translate the glazier’s shrill cry to a song, and to express in lyrical prose all the mournfully suggestive sounds that his cry sends to the attics, through the most elevated mists of the street?

But, to tell the truth, I fear that my jealousy has not brought me luck. As soon as I had begun the work, I noticed that not only did I remain far from my mysterious and brilliant model, but also that I was achieving something (if it can be called something) singularly different, an accidental outcome of which anyone other than I would undoubtedly be proud, but which can only deeply humiliate a mind which considers it the greatest honor of the poet to accomplish exactly what he intended to do.

Your most affectionate

C. B.

1. The Stranger (L’Étranger)

— Whom do you like best, enigmatic man? Your father, mother, sister or brother?

— I have no father, mother, sister or brother.

— Your friends?

— You employ a word whose meaning has remained unknown to me to this day.

— Your country?

— I know not at which latitude it is located.

— Beauty?

— I would love her willingly, a goddess and immortal.

— Wealth?

— I hate it, as you hate God.

— Oh! What do you love, extraordinary stranger?

— I love the clouds... the passing clouds... on high... the marvellous clouds!

‘The Dream’ - Henri Rousseau (French, 1844-1910)

Artvee

2. The Old Woman’s despair (Le Désespoir de la vielle)

The wizened little old woman was full of happiness when she saw the pretty infant whom everyone celebrated, whom everyone wanted to please; that pretty being, as fragile as her, the little old woman, and, like her, also toothless and hairless.

And she approached him, desiring to smile at him, and make pleasant faces.

But the frightened child struggled on being caressed by the good, yet decrepit, old woman, and filled the house with his cries.

Then the good old soul withdrew into her eternal solitude, and wept in a corner, saying to herself: — ‘Alas, for us unfortunate old females the age of pleasing even the innocent has passed; and we horrify the little children we long to love!’

3. The Artist’s confession (Le Confiteor de l’artiste)

How penetrating the end of the autumn days! Ah, penetrating to the point of pain! Because there are certain delicious sensations whose vagueness does not exclude intensity; and there is no sharper point than that of the Infinite.

The pure delight of drowning one’s gaze in the immensity of sky and sea! The solitude, the silence, the incomparable chastity of the azure, some little quivering sail on the horizon which by its smallness and isolation imitates my irremediable existence, the monotonous melody of the swell, all these things think through me, or I think through them (since, in the grandeur of reverie, the ‘I’ is soon lost)! They think, I say, but musically and picturesquely, without quibbles, without syllogisms, without deductions.

However, these thoughts, whether they emerge from me, or arise from things, soon become far too intense. The energies of pleasure create discomfort and positive suffering. My over-stretched nerves yield nothing but screamingly painful vibrations.

And now the depth of the sky dismays me; its limpidity exasperates me. The insensibility of the sea, the immutability of the spectacle, revolt me... Ah, must one suffer eternally, or flee eternally from beauty? Nature, pitiless enchantress, ever-victorious rival, leave me be! Cease from tempting me to desire and to pride! The study of beauty is a duel, in which the artist cries out in fear before being vanquished.

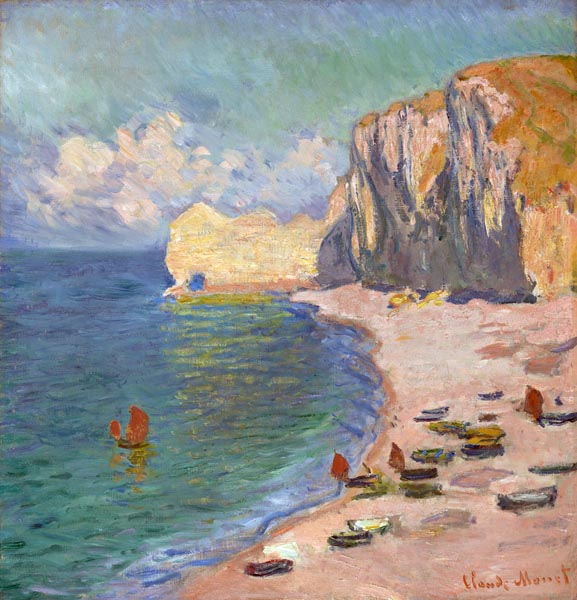

‘Étretat, The Beach and the Falaise d’Amont’ - Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Artvee

4. A Jester (Un Plaisant)

It was the New Year explosion: a chaos of mud and snow, traversed by a thousand carriages, glittering with toys and sweets, teeming with greed and despair, the official delirium of a big city designed to trouble the brain of the most strong-minded solitary.

In the midst of this hustle and bustle, a donkey trotted briskly, harassed by a wretch armed with a whip.

As the donkey was about to turn the corner of a sidewalk, a handsome gentleman, gloved, gleaming, cruelly-bound in a cravat, and imprisoned in brand new clothes, bowed ceremoniously before the humble beast, and said to it, while removing his hat: ‘I wish you well and happy!’ Then he turned towards his unknown comrades with a fatuous air, as if to beg them to add their approbation to his complacency.

The donkey failed to see this handsome jester, and continued to trot, zealously, to wherever his duty summoned him.

On my part, I was seized, suddenly, by immeasurable rage against that magnificent imbecile, who seemed, to me, to concentrate within himself the whole spirit of France.

5. The Dual Room (La Chambre double)

A room that feels like a daydream, a truly spiritual room, where the stagnant atmosphere is lightly tinged with pink and blue.

The soul takes a bath of laziness there, flavored by regret and desire. — It partakes somewhat of the twilight, bluish and pinkish; a dream of voluptuousness during an eclipse.

The furniture takes elongated, prostrate, languid shapes. The furniture has a dreamlike quality; one might consider it endowed with somnambulistic life, like plants and minerals. The fabrics speak a silent language, as do flowers, skies, setting suns.

The walls lack artistic abominations. Relative to pure dream, to unanalyzed impressions, definite art, positive art, is a blasphemy. Here, everything has the adequate clarity and delicious obscurity of harmony.

An infinitesimal scent, one most exquisitely choice, with which is mingled a very slight humidity, swims in this atmosphere, where the slumbering mind is lulled by the sensations aroused by a warm greenhouse.

Muslin rains down abundantly in front of the windows and the bed; it flows into snowy cascades. On this bed lies the Idol, the sovereign of dreams. But how comes she here? Who brought her? what magical power installed her on this throne of reverie and voluptuousness? No matter? Behold! I recognize her.

Hers are the eyes whose flame traverses the twilight; those subtle and terrible orbs that I recognize by their fearful malice! They attract, they subjugate, they devour the gaze of the imprudent person who contemplates them. I have often studied them, those black stars that command curiosity and admiration.

To what benevolent demon do I owe being surrounded, thus, by mystery, silence, peace and perfume? O bliss! That which we generally call life, even in its most fortunate expansion, has nothing in common with this supreme life, which I now know and savor, minute by minute, second by second!

No! There are no more minutes, there are no more seconds! Time has vanished; it is Eternity that reigns, an eternity of delights!

But a dreadful, heavy knock sounded at the door and, as in some infernal dream, I seemed to receive a pickaxe-blow to the stomach.

And then a Ghost entered. A bailiff, come to torture me in the name of the law; an infamous concubine come to cry misery and add the trivialities of her life to the pains of mine; or an errand-boy from some newspaper editor who demands the rest of the copy.

The heavenly room, the idol, the sovereign of dreams, the Sylphide, as the great Chateaubriand called her, all that magic vanished at the brutal blow struck by the Spectre.

Horror! I remember now! I remember! Yes! This hovel, this abode of eternal boredom, is indeed mine. Here is the stupid, dusty, dog-eared furniture; the fireplace without flame or embers, soiled with phlegm; the sad windows where the rain has left furrows in the dust; the manuscripts, scrawled over, or incomplete; the calendar on which a pencil has marked sinister dates!

And that perfume from another world, with which I was intoxicated with a perfection of sensitivity, is replaced, alas, by a fetid odour of tobacco mixed with some nauseous dankness. One breathes, here and now, the rancidness of desolation.

In this narrow world, so full of disgust, one familiar object alone smiles at me: the laudanum vial; an old and dreadful friend; like all friends, alas, rich in caresses and treacheries.

Ah! Yes! Time has reappeared; Time now reigns supreme; and with that hideous old creature have returned all his demonic cortége of Memories, of Regrets, Spasms, Fears, Anxieties, Nightmares, Angers and Neuroses.

I assure you that, now, the seconds are strongly and solemnly accentuated, and each one, springing from the clock, cries: — ‘I am Life; unbearable, implacable Life!’

There is only one second in human life whose mission is to announce good news, that good news which arouses, in all, an inexplicable fear.

Yes! Time reigns; he has resumed his brutal dictatorship. And he drives me on, as if I were an ox, with his forked goad. — ‘Yah, fool! Sweat, slave! Live, and be damned!’

‘The Apparition’ - Gustave Moreau (French, 1826-1898)

Artvee

6. Everyone their own Chimera (Chacun sa Chimère)

Under a wide grey sky, on a large dusty plain, without paths, without grass, without a thistle, without a nettle, I met several men bent over as they walked.

Each of them carried on his back an enormous Chimera, as heavy as a sack of flour or coal, or the equipment of a Roman soldier.

But the monstrous beast was not an inert weight; on the contrary, she enveloped and oppressed the man by exercising her powerful and elastic muscles; she clung with her two vast claws to the chest of her mount; and her fabulous head surmounted the man’s brow, like one of those dreadful helmets with which ancient warriors hoped to increase their enemy’s terror.

I questioned one of these men, and asked him where they were going, thus burdened. He replied that he knew not, neither he nor the others; but that they were evidently going somewhere, since they were driven by an unconquerable need to walk.

A curious thing to note: none of these travelers seemed irritated by the fact that a ferocious beast hung from their neck, and was fixed to their back; it was as if he considered it a part of himself. None of those fatigued and serious faces showed any sign of despair; under the splenetic dome of the sky, their feet bathed in the dust of a wasteland as desolate as the sky, they walked with the resigned countenance of those who are condemned to everlasting hope.

And the procession passed me by, and plunged into the atmosphere of the horizon, to the place where the curved surface of the planet eludes the curiosity of the human gaze.

And for a few moments I persisted in my desire to understand this mystery; but soon an irresistible Indifference descended upon me, by which I was more heavily overwhelmed than were they themselves by their oppressive Chimeras.

7. The Madman and the Statue of Venus (Le Fou et La Vénus)

What an admirable day! The vast park swoons beneath the burning eye of the sun, like Youth dominated by Love.

The universal ecstasy of things is not expressed by means of any noise; the waters themselves are as if asleep. Differing greatly from human celebration, this is an orgy of silence.

It seems as if an ever-growing increasing light causes objects to glitter more and more; that the excited flowers burn with a desire to rival the azure of the sky through the energy of their colors, and that the heat, rendering the perfumes visible, causes them to rise towards the sky like smoke.

Yet, amidst this universal enjoyment, I saw an afflicted being.

At the feet of a colossal Venus, one of those feigned madmen, one of those willing jesters charged with making kings laugh when Remorse or Ennui obsesses them, decked out in a brilliant but ridiculous costume, capped with horns and bells, huddled hard against the pedestal, raises eyes full of tears towards the immortal Goddess.

And his eyes declare: — ‘I am the last and most solitary of humans, deprived of love and friendship, and in that way far inferior to the most imperfect of creatures. However, I too am born to feel and understand immortal Beauty! Ah! Goddess, take pity on my sadness and my delirium!’

But implacable Venus gazes afar, at I know not what, with her marble eyes.

8. The Dog and the Perfume-Bottle (Le Chien et Le Flacon)

‘Nice dog, good dog, my little darling, come near and breathe in this excellent perfume, purchased from the best perfumier in this city.’

And the dog, while wagging its tail, which is, I believe, among those poor beings, the signal corresponding to smiling or laughter, approaches, and with curiosity sets its moist nose to the uncapped bottle; then, suddenly retreating in fear, barks reproachfully at me.

— ‘Ah! Wretched creature, had I offered you a dish of excrement, you would have sniffed it with delight and perhaps devoured it. Thus, unworthy companion of my sad life, you yourself resemble the public, to whom one should never present delicate perfumes which only exasperate it, but rather ordure, chosen with care.’

9. The Wretched Glazier (Le Mauvais Vitrier)

There are natures purely contemplative and wholly unsuited to action, who nonetheless, gripped by a mysterious and unknown impulse, sometimes act with a rapidity of which they would have believed themselves incapable.

Those who, fearing to hear sad news from their concierge, wander in a cowardly manner for an hour or so in front of their door without daring to return; those who keep a letter for two weeks without opening it, or only resigning themselves to embarking, after six months, on an action that was needed a year ago, feel themselves precipitated, brusquely, towards action, by an irresistible force, as if by the arrow of a bow. The moralist and the doctor, who claim to know everything, cannot explain whence comes such mad energy, so suddenly, to these idle and voluptuous souls, and how, being incapable of accomplishing the simplest and most needful things, they often find, at a given instant, the excessive courage to carry out the most absurd and even dangerous acts.

A friend of mine, the most inoffensive dreamer who ever existed, once set fire to a forest to see, he said, if the fire caught as easily as is generally claimed. Ten times in a row, experience fails; but, at the eleventh attempt, it succeeds only too well.

Another, shy to the point that he even lowers his eyes before the human gaze, to the point that he has to summon all his poor will to enter a café, or pass the ticket-office of a theatre, where those in charge appear to him invested with the majesty of Minos, Aeacus, and Rhadamanthus, will suddenly leap at the neck of some old man, passing by, and embrace him enthusiastically before an astonished crowd.

– Why? Because... because that face appealed, irresistibly, to his sympathy? Perhaps; but it is more legitimate to suppose that he himself does not know why.

I have more than once been the victim of these crises and impulses, which lead us to believe that malicious demons slither into us, and make us perform, without our knowledge, their most absurd wishes.

One morning I rose in a sullen mood, sad, weary of idleness, and driven, it seemed to me, to deliver something great, an act of brilliance; and, alas, I opened the window!

(Observe, please, that the spirit of perversity which, in some people, is not a result of overwork or confusion, but of chance inspiration, partakes a great deal, if only in its ardent desire, of that mood of hysteria according to the medical men, or satanism, according to those who think more deeply than they, which drives us, without resistance, towards a host of dangerous or inappropriate actions.)

The first person I viewed, in the street below, was a glazier whose piercing, discordant cry reached me through the stale and heavy Parisian atmosphere. It would be impossible, however, for me to say why I was seized with so sudden and despotic a hatred towards the poor fellow.

– ‘Hey! You, there!’, I shouted, summoning him to ascend. However, I reflected, not without some cheerfulness, that, the room being on the sixth floor and the staircase very narrow, the man would experience some difficulty in making that ascent, while striking the corners of his fragile merchandise against many a surface.

At last, he appeared: I examined, with curiosity, all his panes of glass, and then cried: What? You have no stained glass? No pink, red, blue panes of which to form magic windows, paradisial windows? What impudence! You dare to wander the poorest quarters, yet you lack the very panes of glass designed to show life in all its beauty!’ And I pushed him, swiftly, towards the stairs, down which he stumbled, grunting.

I approached the balcony, seized a small flower-pot, and, when the man appeared through the doorway, let my engine of war fall perpendicularly to strike the rear ends of his carrying-hooks. The shock knocked him over, and ended up shattering all his meagre ambulatory wealth beneath his back, which emitted the brilliant sounds of a palace of crystal pierced by lightning.

And, drunk with my madness, I shouted furiously: ‘The beauty of life! The beauty of life!’

Such agitated pleasantries are not uttered without danger, and one may often pay dearly for them. But what does an eternity of damnation matter to one who has found an infinite moment of joy?

10. At One in the Morning (À Une Heure du Matin)

At last! Alone! All one hears is the rumble of a few tired and belated cabs. For a few hours we shall have silence, if not rest. At last! The tyranny of the human face has disappeared, and I will no longer suffer except on account of myself.

At last! I am allowed to take my ease in a bath of darkness! First, a double turn of the lock. It seems to me that this twofold turn of the key will add to my solitude and strengthen the barriers that truly separate me from the world.

Dreadful life! Dreadful city! Recapitulation of my day: having seen several men of letters, one of whom asked me if one could go to Russia overland (he probably mistook Russia for an island); having argued forcefully with the editor of a magazine, who answered every objection with: ‘This is the work of honest people,’ implying that all the other newspapers are written by rascals; having greeted some twenty people, fifteen of whom were unknown to me; having granted handshakes in the same proportion, and this without having taken the precaution of buying gloves; having ascended, in order to kill time, during a downpour, to the house of an acrobatic ‘dancer’ who asked me to design a costume for her, that of a devotee of Venus; having paid court to a theatre director, who said to me, on dismissing me: ‘— You would perhaps do well to contact Z…; he is the dullest, most foolish, and most famous of all my playwrights, with him you could perhaps achieve something. See to it, and then we will see;’ having boasted (why?) of several unpleasant actions that I’ve never committed, and having, in a cowardly manner, denied some other misdeeds that I accomplished with joy, delighting in bluster, a crime against human respect; having refused to do a straightforward favour for a friend, and having given a written recommendation to a complete clown; ouf! is it truly over?

Discontented with everyone, discontented with myself, I would wish to redeem myself and derive some pride from the silence and solitude of the night. Souls of those whom I have loved, souls of those I have sung, strengthen me, sustain me, rid me of the lies and corrupting vapours of the world, and you Lord, my God, grant me the grace to produce a few beautiful verses, so as to prove to myself that I am not the lowest of men, that I am not inferior to those I despise!

11. The Wild Woman and the Little-Mistress (La Femme Sauvage et La Petite-Maîtresse)

Truly, my dear, you weary me beyond measure, and beyond pity; one might say, hearing your sighs, that you suffer more than any sixty-year-old scavenger, more than any old beggar collecting crusts of bread at the tavern-doors.

If your sighs only expressed remorse, at least, they would do you some honour; but they only reflect the satiety of well-being and the lassitude of rest. And then, you never cease pouring out useless words: ‘Love me deeply! I need it so! Console me here, caress me there!’ Come, then, I shall try to remedy the problem; we will perhaps find the means, for two sous, in this entertainment, and without going far.

Let us consider, carefully, I pray you, this solid iron cage behind which moves, howling like the damned, shaking the bars like an orangutan exasperated by exile, often imitating to perfection, sometimes, the curving leaps of a tiger, sometimes the stupid waddling of a polar-bear, this monster with hair, whose shape vaguely imitates yours.

The monster is one of those animals that we generally call ‘My angel!’ which is to say a woman. That other monster, who screams at the top of his lungs, with a stick in his hand, is a husband. He has chained his lawful wife like an animal, and he displays her in the suburbs, on market days, with permission from the magistrates needless to say.

Pay close attention! Behold with what voracity (perhaps unfeigned!) she tears up live rabbits and squawking poultry thrown to her by her keeper.’ ‘Come’ says he, ‘you are not to eat all your spoils in one go,’ and, with this wise speech, he cruelly rips away the prey, whose uncoiled guts are left clinging, for a moment, to the teeth of that ferocious beast; the woman, I mean.

Come! A good blow from that stick to calm her down! For she darts dreadful covetous glances at the stolen food. Good Lord! His stick is no theatre prop, do you not hear the flesh resound, despite the false hair? Her eyes, too, are leaping from their sockets, she screams in a most natural way. She gives off sparks everywhere, in her rage, like iron being beaten.

Such are the conjugal manners of these two descendants of Eve and Adam, these works of your hands, O Lord! The woman is incontestably wretched; though the titillating pleasures of notoriety are, after all, perhaps not unknown to her. There are more irremediable misfortunes, and ones without compensation. Yet, in the world into which she has been thrown, she can never believe that women deserve a different fate.

Now for the two of us, my precious dear! Seeing the hellish forms with which the world is peopled, what would you have me think of your pretty form, you who only repose on fabrics soft as your skin, who only eat the tenderest cooked meats, and for whom a skillful servant carves the pieces?

And what can all those little sighs that swell your perfumed breast mean to me, my vibrant coquette? Or all those affectations learned from books, and that indefatigable melancholy, designed to inspire in the spectator a sentiment quite other than pity? In truth, I sometimes wish to teach you what real unhappiness is.

To see you like this, my delicate beauty, with your feet in the mud and your eyes turned mistily towards the sky, as if seeking a prince, one might liken you to a young female frog invoking the ideal. Though you despise the nonentity (which I now am, as you well know), shun the heron that will seize you, swallow you, and slay you, at its pleasure!

As poetical as I am, I am not as much of a dupe as you wish to believe, and if you weary me too often with your precious whining, I will treat you like a wild woman, or throw you out of the window like an empty bottle.’

12. Crowds (Les Foules)

It is not given to everyone to take a bath among the multitude: enjoying the crowd is an art; and he only can make, at the expense of the human race, a lively feast of it, in whom a fairy instilled, in his cradle, the taste for disguise and the mask, a hatred of home, and a passion for travel.

Multitude, solitude: equal and transposable terms for the active and fecund poet. He who knows not how to people his solitude, is equally ignorant of how to be alone in a busy crowd.

The poet enjoys this incomparable privilege, that he can, as he pleases, be himself or others. Like those wandering souls searching for a body, he enters, whenever he wants, into the character of each person. For him alone, everything is open; and if certain places appear to be closed to him, it is because in his eyes they are not worth the effort of visiting.

The solitary and pensive walker derives a singular intoxication from this universal communion. He who readily espouses the crowd knows feverish pleasures, of which egoists, closed like a coffer, and the lazy, enclosed like a mollusk, will be eternally deprived. He adopts as his own all the professions, all the joys, and all the miseries that circumstances present.

What men call love is very slight, restricted, and feeble, compared to this ineffable orgy, to this sacred prostitution of the soul which gives itself entire, its poetry and charity, to the unexpected that reveals itself to the passing stranger.

It is good to sometimes teach the happy folk of this world, if only to humiliate their stupid pride for a moment, that there are happinesses superior to theirs, vaster and more refined. The founders of colonies, the leaders of peoples, the missionary priests exiled to the ends of the earth, undoubtedly know something of these mysterious intoxications; and, amidst the vast family that their genius has made for itself, they must laugh sometimes at those who pity them for a fate so troubled and a life so chaste.

13. Widows (Les Veuves)

Vauvenargues says that in public gardens there are paths haunted mainly by disappointed ambition, by unhappy inventors, by aborted glories, by broken hearts, by all those tumultuous and shuttered souls, in whom the last sighs of a storm rumble, and who retreat far from the insolent gaze of the joyful and the idle. Such shady retreats are the meeting-places of those crippled by life.

It is above all towards these places that the poet and the philosopher like to direct their eager conjectures. There is sure nourishment there. Because if there is one region that they disdain to visit, as I insinuated earlier, it is above all that of the joys of wealth. That turbulence in the void has nothing that attracts them. On the contrary, they feel irresistibly drawn towards everything that is feeble, ruined, saddened, orphaned.

An experienced eye is never mistaken. In these rigid or dejected features, in these eyes, dull and hollow, or glittering with the last flashes of the struggle, in these deep and numerous wrinkles, in these steps so slow or spasmodic, he instantly deciphers the innumerable legends of love deceived, devotion gone unrecognized, effort unrewarded, hunger and cold humbly and silently endured.

Have you never noticed the widows on those lonely benches, the poor widows? Whether they are grieving or not, it is easy to recognize them. Besides, there is always something lacking in the mourning-dress of the poor, an absence of harmony which renders it the more heartbreaking. Poverty is forced to be economical. Wealth wears its grief entire.

Who is the saddest and most saddening widow, she who carries a toddler with whom she cannot share her reveries, or she who is completely alone? I am unsure... I once happened to follow an old woman, afflicted in this way, for long hours; she walked stiffly and erectly, cloaked in a little worn shawl, displaying with all her being a stoic pride.

She was obviously condemned, by her absolute solitude, to pursue the habits typical of an old bachelor, and the masculine character of her manner added a mysterious piquancy to its austerity. I know not how or in which wretched café she lunched. I followed her to the reading room; and watched for a long time while she searched the newspapers, with active eyes, once burned by tears, for news of some powerful and personal matter.

Finally, in the afternoon, under a charming autumn sky, one of those skies from which a host of regrets and memories descend, she sat apart in a garden, to hear, far from the crowd, one of those concerts whose regimental music gratifies the citizens of Paris.

This was doubtless the sole small debauchery of this innocent old woman (or this old woman purified by life), the well-earned consolation of one of those days that weigh so heavily, one without friends, without gossip, without joy, without a confidant, which God had burdened her with, perhaps for many years, three hundred and sixty-five days a year!

Then again: I can never help casting a glance, which if not universally sympathetic is at least curious, at the host of pariahs who crowd the grounds of some public concert. The orchestra hurls the sound of celebration, triumph, or pleasure into the night. The trailing dresses shimmer; eyes meet; the idlers, wearied by doing nothing, parade about, feigning, indolently, to enjoy the music. Here one sees nothing but wealthy, happy people; nothing that fails to breathe and inspire carefreeness and the pleasure of allowing oneself to live; nothing, that is, except the appearance of the throng over there leaning against the exterior barrier, catching gratis, on the breeze, a scrap of music, and gazing at the sparkling interior of this furnace.

It is always interesting to view a reflection of the rich man’s joy in the depths of the poor man’s eye. But one day, amidst that throng dressed in blouses and cotton fabrics, I saw a being whose nobility made a striking contrast with her trivial surroundings.

This was a tall, majestic woman, so noble in all respects that I cannot remember having seen her like amongst all the gathered images of the aristocratic beauties of the past. A perfume of haughty virtue emanated from her entire person. Her face, sad and thin, was in perfect accord with the grand mourning in which she was dressed. She too, like the common folk among whom she mixed and whom she scarcely saw, viewed that luminous world with a profound gaze, and listened while gently nodding her head.

A singular vision! ‘To be sure,’ I said to myself, ‘such poverty, if poverty there be, cannot admit of sordid economy; so noble the face that appears to me there. Why then does she voluntarily remain in an environment in which she forms so striking an anomaly?’

But as I passed by her, in my curiosity, I thought I divined the reason. The richly-clad widow was holding by the hand a little boy, dressed like her in black; However modest the price of entry, the amount would suffice perhaps to pay for one of the little fellow’s needs, or better still, something superfluous, some toy or other.

And she must have returned on foot, meditative and dreaming, alone, always alone; because the child is turbulent, selfish, lacking in gentleness or patience; and cannot, like a simple creature, a dog or a cat, serve as a confidant to the sad and solitary.

14. The Old Acrobat (Le Vieux Saltimbanque)

Everywhere spread the crowd of folk on vacation, engaged in enjoying themselves. It was one of those solemn feast-days on which, for a long time, acrobats, conjurers, animal trainers, and itinerant traders have relied, to compensate for the seasons of bad weather.

It seems to me that, on such days, people forget all their work and suffering; they become like little children. For the common crowd, it’s the horrors of school suspended for twenty-four hours. For their masters it’s an armistice concluded with the maleficent powers of life, a respite from universal conflict and struggle.

Even the man-of-the-world and the man engaged in spiritual labour find it difficult to escape the influence of this popular feast. They absorb, without wanting to, their share of the carefree atmosphere. For myself, I never fail, as a true Parisian, to view all the booths on parade at these solemn times.

They were, in truth, in formidable competition: they squawked, bellowed, howled. It was a mix of screams, brassy detonations, and aerial explosions. The swarthy-faced clowns and jesters convulsed their features, shriveled by wind, rain and sun, and, with the aplomb of actors sure of their effects, threw out witticisms and jokes as solid and heavy as those of Molière. The various versions of Hercules, proud of the enormity of their limbs, lacking brows or craniums, like orangutans, lounged majestically clad in tights washed for the occasion the previous day. The dancers, as beautiful as fairies or princesses, jumped and cavorted beneath the fiery lanterns that made their skirts sparkle.

All was light, dust, cries, joy, tumult; some spent, others profited, both equally joyful. Children hung on their mother’s petticoats to obtain a stick of sugar, or climbed on their father’s shoulders to win a better view of the conjurer, dazzling them like a god. And everywhere, dominating all the scents, lingered a smell of fried food, which was the incense to this celebration.

At the end, at the far end of the row of booths, as if he had exiled himself, in shame, from all these splendors, I saw a poor acrobat, bent, hunched over, decrepit, a ruin of a man, leaning against one of the posts of his booth; a booth more wretched than that of the most stupid savage, the distressed state of which two candle-ends, pouring out smoke, nonetheless illuminated all too well.

Everywhere else was joy, profit, debauchery; everywhere the certainty of bread for tomorrow; everywhere a frenzied explosion of vitality. Here, absolute poverty, poverty dressed, to heighten its horror, in comedic rags, a contrast introduced far more by necessity than art. He was not laughing, the poor wretch! He gave no cry, danced not, made no gesticulation, uttered no shouts; he sang no song, neither joyful nor lamentable, he did not seek to attract. He was silent and motionless. He had renounced, he had abdicated. His fate was sealed.

But what a deep, unforgettable gaze he cast upon the lights, and the crowd whose constant flow ceased a few paces from his repulsive wretchedness! I felt my throat squeezed in the dreadful grip of hysteria, and my eyes, it seemed to me, were offended by rebellious tears which did not wish to fall.

What could I do? What was the point of asking the unfortunate man what curiosities, what wonders he had to show in the stinking darkness behind his torn curtain? In truth, I dared not; and, even if the reason for my reticence makes you laugh, I admit that I went in fear of humiliating him. I had, at last, decided to drop some coins onto the boards, hoping he would divine my intention, when a powerful ebb of people, caused by I know not what disturbance, swept me away from him.

On returning, obsessed by this vision, I tried to analyse my sudden pain, and said to myself: I have seen, just now, the image of the old literary fellow who survives the generation which he has once entertained so brilliantly; the old poet devoid of friends, family, or children; degraded by poverty and public ingratitude; into whose booth the neglectful world no longer desires to enter!

‘Equestrienne (At the Cirque Fernando)’ - Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (French, 1864-1901)

Artvee

15: The Cake (Le Gâteau)

I was travelling. The landscape, in the midst of which I was placed, was of irresistible grandeur and nobility. Something undoubtedly passed through my soul at that moment. My thoughts fluttered with a lightness equal to that of the atmosphere; vulgar passions, such as hatred and profane love, now appeared to me as distant as the clouds which moved through the depths beneath my feet; my soul seemed to me as vast and pure as the dome of the sky in which I was enveloped; the memory of terrestrial things only reached my heart in weakened and diminished form, like the sound of the bell from a herd of cattle that grazed, imperceptibly, far, far away, on the slope of another mountain. On the small still lake, black due to its immense depth, the shadow of a cloud sometimes passed, like the reflection of the mantle of an aerial giant flying across the sky. And I remember that the rare and solemn sensation caused by its immense, perfectly silent motion, filled me with joy mixed with fear. In short, I felt, thanks to the enthusiasm engendered by the beauty with which I was surrounded, at perfect peace with myself, and with the universe; I even believe that, in my state of perfect beatitude and total forgetfulness of all earthly evil, I found the newspapers, that claim that man is born good, no longer so ridiculous; — when inescapable matter renewed its demands, I thought of easing the fatigue and relieving the appetite caused by such a long ascent. I took from my pocket a large piece of bread, a leather cup, and a bottle of a certain elixir that pharmacists sold to tourists at that time to be mixed, now and then, with melt-water.

I was quietly slicing the bread, when the slightest of sounds made me look up. Before me stood a little ragged, black and disheveled, creature, whose hollow, fierce, pleading eyes devoured the piece of bread before me. And I heard him sigh, in a low and hoarse voice, the word: cake! I couldn't help but laugh when I heard the term with which he wanted to honour my almost-white bread, and I cut a goodly slice, and offered it to him. He approached, slowly, never removing his gaze from the object of his desire; then, snatching the piece with his hand, drew back swiftly, as if he feared that my offer was insincere or that I already repented of it.

But at that very moment he was knocked aside by another little savage, who had come from I know not where, one so exactly similar to the first that he could have been taken for his twin brother. Together they rolled on the ground, fighting over the precious spoil, neither it seemed wishing to sacrifice half of it to his brother. The first, exasperated, grabbed the second by the hair; he gripped his ear with his teeth and spat out a small bloody piece with a superb curse in the local patois. The rightful owner of the cake tried to sink his little nails into the usurper’s eyes; he, in turn, applied all his strength to strangling his opponent with one hand, while attempting, with the other, to slip the prize derived from this duel into his pocket. But, revived by despair, the loser arose, and tumbled the winner to the ground with a headbutt to the stomach. What would be the point of describing the hideous struggle that indeed lasted longer than their childish strength seemed to promise? The cake traveled from hand to hand, and changed pockets at every moment; but, alas, it also changed volume; and when at last, exhausted, panting, bleeding and unable to continue they ceased, they no longer had, to speak truthfully, reason to fight; the piece of bread had vanished, scattered in tiny crumbs akin to the grains of sand with which they now mingled.

This spectacle had clouded the landscape for me, and the calm joy, which had amazed my soul before viewing these little fellows, had wholly disappeared; I remained saddened by it for a good long time, repeating to myself endlessly: ‘There is then a fine country where bread is called cake, a delicacy so rare that it is enough to cause a perfectly fratricidal war!’

16: The Clock (L’Horlogue)

The Chinese tell the hour by gazing into a cat’s eyes.

One day a missionary, walking in the suburbs of Nanking, noticed that he had forgotten his watch, and asked a little boy what time it was.

That urchin of the Celestial Empire hesitated at first; then, reconsidering, replied: ‘I’ll tell you.’ A few moments later, he reappeared, holding in his arms a very large cat, and gazing, as they say, into the whites of its eyes, he affirmed without hesitation: ‘It’s not quite noon yet.’ Which was true.

For myself, if I lean towards the lovely Feline, so aptly named, who is at one and the same time the honour of her sex, the pride of my heart, and the perfume of my spirit, whether at night, or during the day, whether beneath a bright light or in opaque shadow, I always see, in the depths of her adorable eyes, the time distinctly marked, and ever the same, a vast, solemn hour, as extensive as space, without division into minutes or seconds, — a motionless hour which is not indicated on the clocks, and yet is light as a sigh, rapid as a glance.

And if some importunate person came and disturbed me while my gaze rested on this delightful dial, if some dishonest and intolerant Genie, some Demon of inopportune time came and said to me: ‘What are you looking at there, so intently? What are you searching for in the eyes of this being? Do you wish to mark the hour there, prodigal and lazy mortal?’ I would answer without hesitation: ‘Yes, I mark the hour; it’s the hour of Eternity!’

Is this, madame, not a truly meritorious madrigal, as emphatic as yourself? In truth, I had so much pleasure embroidering this pretentious piece of gallantry, I will not ask aught of you, in return.

17. A Hemisphere in a Head of Hair (Un Hémisphère dans une Chevelure)

Let me breathe for long, long hours, the odour of your hair, plunge my whole face into it there, as a thirsty man plunges his face in a stream, and shake it about with my hand like a fragrant handkerchief, to shake memories into the air.

If you could only know all that I see! All that I sense! All that I hear in your hair! My soul is transported by perfume as the souls of others by music.

Your tresses contain a whole dreamlike scene, full of sails and masts; they contain vast seas whose monsoons carry me towards delightful climes, where space is deeper and bluer, where the atmosphere is perfumed by fruits, by leaves, and the surface of human skin.

In the ocean of your hair, I glimpse a harbour teeming with melancholy songs, vigorous men of every nation, and ships of all kinds that display their fine and complex structures against the immense sky basking in eternal heat.

In the caresses of your hair, I find again the languor of long hours spent on some divan, in the cabin of some graceful vessel, lulled by the imperceptible rolling of the harbour’s waves, amidst pots of flowers, and refreshing drinks.

In the fiery bed of your hair, I breathe the scent of tobacco mingled with opium and sugar; in the nocturnal depths of your hair, I see the glow of an infinite tropical azure; on the downy shores of your hair, I am intoxicated by the combined odour of tar, and musk, and coconut oil.

Let me bite your heavy, black tresses for hours. When I bite your elastic and rebellious hair, it seems to me I am consuming memories.

18. The Invitation to the Voyage (L’Invitation au voyage)

There’s a magnificent land, a land of Cockaigne, they say, that I’ve dreamed of visiting with a dear mistress. A unique land, drowned in our Northern mists, that you might call the Orient of the West, the China of Europe, so freely is warm and capricious Fantasy expressed there, so patiently and thoroughly has she adorned it with rare and luxuriant plants.

A true land of Cockaigne, where all is lovely, rich, tranquil, honest: where luxury delights in reflecting itself as order: where life is full and sweet to breathe: from which disorder, turbulence, the unforeseen are banished: where happiness is married to silence: where the food itself is poetic, both rich and exciting: where everything resembles you, my dear angel.

Do you know the fevered malady that seizes us in our chilly wretchedness, the nostalgia for an unknown land, the anguish of curiosity? There’s a country you resemble, where everything is lovely, rich, tranquil and honest, where Fantasy has built and adorned an occidental China, where life is sweet to breathe, where happiness is married to silence. There we must go and live, there we must go to die!

Yes, there we must go to breathe, dream, prolong the hours with an infinity of sensations. Some musician has composed The Invitation to the Waltz: who shall compose The Invitation to the Voyage, that one might offer to the beloved, the sister of one’s choice?

Yes, it would be good to be alive in that atmosphere, – there where the hours pass more slowly and contain more thought, where the clocks chime happiness with a deeper, more significant solemnity.

On gleaming wall-panels, on walls lined with gilded leather, of sombre richness, blissful paintings live discreetly, calm and deep as the souls of the artists who created them. The sunsets that colour the dining-room, or the salon, so richly, are softened by fine fabrics, or those high latticed windows divided in sections by leading. The furniture, vast, curious, bizarre, is armed with locks and secrets like refined souls. The mirrors, metals, fabrics, plate and ceramics play a mute, mysterious symphony for the eyes: and from every object, every corner, the gaps in the drawers, the folds of fabric, a unique perfume escapes: the call of Sumatra, that is like the soul of the apartment.

A true land of Cockaigne, I tell you, where all is rich, clean, and bright like a clear conscience, like a splendid battery of kitchenware, like magnificent jewellery, like a multi-coloured gem! The treasures of the world enrich it, as in the house of some hard-working fellow, who’s deserved well of the whole world. A unique land, superior to others, as art is to Nature, re-shaped here by dream, corrected, adorned, remade.

Let them search and search again, tirelessly extending the frontiers of their happiness, those alchemists of the gardener’s art! Let them offer sixty, a hundred thousand, florins reward to whoever realises their ambitious projects! I though, have found my black tulip, my blue dahlia!

Incomparable bloom, tulip re-found, allegorical dahlia, it is there, is it not, to that beautiful land so calm and full of dreams, that you must go so as to live and flower? Would you not be surrounded by your own analogue, could you not mirror yourself, to speak as the mystics do, in what corresponds to you, in your own correspondence?

Dreams! Always dreams! And the more aspiring and fastidious the soul, the more its dreams exceed the possible. Every man has within him his dose of natural opium, endlessly secreted and renewed, and how many hours do we count, from birth to death, that are filled with positive pleasure, by successful deliberate action? Shall we ever truly live, ever enter this picture my mind has painted, this picture that resembles you?

Those treasures, items of furniture, that luxury, order, those perfumes, miraculous flowers, are you. They are you also, those great rivers and tranquil canals. Those huge ships they carry, charged with riches, from which rise monotonous sailors’ chants, those are my thoughts that sleep or glide over your breast. You conduct them gently towards that sea, the Infinite, while reflecting the depths of the sky in your sweet soul’s clarity: – and when, wearied by the swell, gorged with Oriental wares, they re-enter their home port, they are my thoughts still, enriched, returning from the Infinite to you.

19. The Poor Child’s Toy (Le Joujou du Pauvre)

I’d like to suggest a means of innocent entertainment. There are so few amusements that are guiltless!

When you saunter forth, in the morning, with the decided intention of strolling along the high street, fill your pockets with little trinkets costing a sou — such as the cut-out Pulcinella moved by a single wire, the blacksmith who beats his anvil, the horseman on his horse whose tail is a whistle, — and along the fronts of the café-cabarets, at the foot of the trees, pay homage to the poor and unknown children you meet. You will see their eyes widen immeasurably. At first, they will not dare to accept; they will doubt their happiness. Then their hands will quickly snatch the gift, and they will flee like cats to eat, far from you, the morsel you gave them, having learned to mistrust humankind.

On a road, behind the gate of a vast garden, at the end of which appeared the white facade of a pretty castle struck by the sun, stood a clean and beautiful child, dressed in those country clothes which are so full of coquetry.

Luxury, carefreeness, and the habitual spectacle of wealth render such children so pretty that one would believe them to be made of a different mould than the children of mediocrity or poverty. Beside him, on the grass, lay a splendid toy, as clean as its master, varnished, gilded, dressed in a purple robe, and covered with plumes and beads. But the child was not taking care of his favorite toy, for this is what he was looking at:

On the other side of the gate, on the road, among the thistles and nettles, there was another child, dirty, puny, black with soot, one of those outcast brats whose beauty an impartial eye would discover, if, as the eye of the connoisseur detects an ideal painting under a coachbuilder's varnish, it was to clean it of the disgusting patina of poverty.

Through the symbolic bars separating their two worlds, the highway and the chateau, the poor child showed the rich child his own toy, which the latter eagerly examined like a rare and unknown object. Now, this toy, which the little wretch harassed, tossing it about, and shaking it, in a box with a barred grille, was a live rat! The parents, no doubt to save money, had provided a toy plucked from life itself.

And the two children laughed at each other, in a fraternal manner, with teeth of an equal whiteness.

20. The Fairies’ Gifts (Les Dons des Fées)

There was a great gathering of the Fairies, to perform a distribution of gifts among all the newborns who had begun their lives within the last twenty-four hours.

Those ancient and capricious Sisters of Destiny, those bizarre Mothers of joy and pain, were all very diverse: some had a sombre and reticent air, others, a playful and mischievous one; some, young, having always been young; others, old, having always been old.

All the fathers who believed in Fairies had come, each bringing their newborn in their arms.

The Gifts: Faculties, Good Luck, unalterably beneficial Circumstance, were set before the court, like prizes on the platform at a distribution of prizes. What was unusual here was that the Gifts were not rewards for effort, but on the contrary a grace granted to those who had not yet lived, a grace capable of determining their destiny. and becoming as much the source of misfortune as of happiness.

The poor Fairies were very busy, since the crowd of petitioners was great, and the intermediate world, set between Humankind and God, is subject like us to the terrible law of Time and its infinite descendants, the Days, Hours, Minutes, and Seconds.

In truth, they were as stunned as ministers on a day of hearings, or employees of the Institutional Pawnshop, when a National Holiday permits free clearances. I believe that from time to time they even looked at the clock-hands with as much impatience as human judges who, having sat since morning, cannot help but dream of dinner, of the family, and their beloved slippers. If there is a degree of haste and chance in supernatural justice, let us not be surprised if the same is sometimes the case in human justice. In this matter we ourselves would be unjust judges.

Indeed, some blunders were committed that day which might well be considered bizarre, if prudence, rather than caprice, were the distinctive, eternal character of the Fairies.

Thus, the power to magnetically attract wealth was awarded to the sole heir of a very rich family, who, being endowed with no feelings of charity, nor any desire for the most visible possessions of life, was later to find himself prodigiously embarrassed by his millions.

Thus, the love of Beauty and poetic Power were given to the son of an obscure wretch, a quarryman by trade, who could not, in any way, assist in developing the faculties, nor relieve the needs of his deplorable offspring.

I neglected to tell you that the distribution of gifts, in these solemn matters, is final, and that no donation can be refused.

All the Fairies rose, believing their chore accomplished; since no gifts remained, no further largesse to scatter among all this human fry, when a bold man, a poor little tradesman I believe, stood up, and seizing by her dress of multicolored mist, the Fairy who was closest to him, cried: Oh! Madame! You’ve forgotten us! There is still my little one! I’d not wish to have come for naught.’

The Fairy might have been embarrassed; since there was nothing left. However, she remembered, in time, a well-known law, though one rarely applied in the supernatural world, inhabited by intangible deities, friends to humankind, and often forced to adapt to its passions, such as the Fairies, Gnomes, Salamanders, Sylphides, Sylphs, Nixies, Merfolk and Undines, — I mean the law which grants to a Fairy, in a case similar to this, that is to say a case of the exhaustion of lots, the possibility of granting one more, supplementary and exceptional, provided however that she has sufficient imagination to create it immediately.

So, the good Fairy replied, with an aplomb worthy of her rank: ‘I give your son… I give him… the Gift of pleasing!’

‘What? Of pleasing? …Why that?’ asked the stubborn little shopkeeper, who was undoubtedly one of those all-too-common rationalists incapable of rising to the logic of the Absurd.

‘Because! Because!’ replied the angry Fairy, turning her back on him; and, joining the long procession of her companions, cried: ‘What do you think of this conceited little Frenchman, who wishes to comprehend all; one who, having obtained the best of gifts for his son, still dares to question and dispute the indisputable?’

21. The Temptations, or Eros, Plutus, and Glory (Les Tentations, ou Éros, Plutus et La Gloire)

Two superb Satans and a She-Devil no less extraordinary last night climbed the mysterious staircase by means of which Hell attacks a man’s weaknesses while he sleeps, and communicates with him, in secret. They came and stood gloriously before me, as if on a platform. A sulphurous splendour emanated from those three personages, detaching themselves from the opaque background of the night. They looked so proud and so full of authority that, at first, I took all three of them for true gods.

The face of the first Satan was of an ambiguous gender, and there was, also, in the lines of his body, the softness of the ancient Bacchus. His lovely languid eyes, of a dark and uncertain color, resembled violets still weighed down by the heavy tears of a storm, and his lips, half-opened, lit censers, which breathed out the fine odour of a perfumery; while each time he sighed, musky fluttering insects were illuminated by the ardour of his breath.

About his purple tunic was coiled, like a belt, a shimmering serpent which, with raised head, turned fiery eyes languorously upon him. From this living belt were suspended brilliant knives and surgical instruments, alternating with vials full of sinister liquors. In his right hand he held another vial whose contents were a luminous red, and which bore these strange words on its label: ‘Drink, this is my blood, a perfect cordial’; in his left, a violin which undoubtedly served him to sing his pleasures and pains, and spread the contagion of his madness on Sabbath nights.

From his delicate ankles trailed sundry links from a broken gold chain, and when the resulting inconvenience forced him to lower his eyes to the ground, he contemplated, with vanity, his toenails, as brilliantly polished as well-wrought gemstones.

He looked at me with inconsolably heartbroken eyes, from which an insidious intoxication flowed, and he said to me in a singing voice: ‘If you wish, if you wish, I will make you the lord of souls, and you will be the master of living matter, even more than a sculptor could ever be of clay; and you will experience the pleasure, constantly renewed, of emerging from yourself to lose yourself in others, and of attracting other souls to the point of confusing them with yours.’

And I replied: ‘Thanks, indeed! I have nothing to do with such trash, beings who, doubtless, are no better than my poor self. Though I am somewhat ashamed of my memories, I’ve no wish to forget a thing; and even if I failed to recognise you, you old monster, your mysterious instruments, your dubious vials, the chains which entangle your feet, are symbols which reveal most clearly the disadvantages of any friendship with you. Keep your gifts.’

The second Satan had neither his air, which was both smiling and sad, nor those beautiful insinuating manners, nor his delicate and fragrant beauty. He was a large fellow, with a broad, eyeless face, whose heavy paunch hung over his thighs, and whose entire skin was golden and decorated, as if tattooed, with a crowd of little figures in motion illustrating the many forms of universal misery. There were small, scrawny men who hung themselves, voluntarily, from nails; there were little deformed, skinny gnomes, whose pleading eyes begged for alms, more so, even, than their trembling hands; ancient mothers carrying abortions clinging to their exhausted breasts; and many another.

The large Satan pounded his fist on his immense belly, from which came a long and resounding clank of metal, which ended in a vague moan made by numerous human voices. And he laughed, impudently, revealing his ruined teeth, with an enormous imbecile laugh, like certain men of all countries when they have dined too well.

Then he addressed me: ‘I can give you that which wins all, which is worth all, and replaces all!’ And he slapped his monstrous belly, whose sonorous echo commented upon his crude words.

I turned away with disgust, and replied: ‘I’ve no need of anyone’s misery, in order to enjoy myself; nor do I desire the saddening wealth, like wall-paper, of all those miseries represented on your skin.’

As for the She-Devil, I would be lying if I failed to admit that, at first sight, I found her strangely attractive. To define her charm further, I can compare it to nothing better than that of a most beautiful woman, past her prime, who nonetheless no longer ages, and whose beauty holds the penetrating magic of ancient ruins. She looked both imperious and gangling, and her eyes, though bruised, held a fascinating force. What struck me most was the mystery of her voice, in which I found memories of the most delicious contralti and also a little of the hoarseness of throats incessantly cleansed by brandy.

‘Do you wish to know my power?’ said the false goddess, in her charming and paradoxical voice. ‘Listen.’

And she set to her mouth a gigantic trumpet, wreathed in ribbons, like a mirliton, with the titles of all the newspapers in the universe inscribed upon them, and through this trumpet she proclaimed my name, which thus rolled through space with the noise of a hundred thousand peals of thunder, and returned upon me, reverberating, in an echo from the furthest planet.

‘The Devil!’ I cried, half-captivated, ‘She’s something precious!’ But on examining that seductive virago more closely, it seemed to me that I recognized her, vaguely, from having seen her clinking glasses with some rascals of my acquaintance; and the hoarse sound of the brass trumpet brought to my ears the memory of some harlot’s turned-up nose.

So, I replied, with complete disdain: ‘Be off with you! I was not born to wed the mistress of certain folk I’ve no wish to name.’

22. The Shadows of Evening (Le Crépuscule de Soir)

Evening falls. A vast peace descends upon wretched spirits wearied by the day’s work; and their thoughts now assume the tender and indecisive colors of twilight.

Yet, from the heights of the hill a great howl reaches my balcony, through the transparent evening clouds, a howl composed of a host of discordant cries, that space transforms into a lugubrious harmony, like that of the rising tide rising or an awakening storm.

Who are those unfortunates whom the evening fails to calm, and who, like owls, take the coming of night for a sign of the Sabbath? The sinister chant comes to us from that blackened institution for the sick and destitute perched on the heights; and from the evening, contemplating, in wreaths of smoke, the rest of the immense valley, bristling with houses, each window of which says: ‘Here, now, is peace; here is the joy of family!’ I can, when the wind blows from on high, lull my astonished thoughts to this imitation of the harmonies of hell.

Twilight excites the mad. — I recall that I had two friends whom the dusk rendered quite wretched. One ignored, then, all the ties of friendship and politeness, and mistreated the first-comer like a savage. I saw him hurl an excellent plate of chicken, in which he thought he saw some insulting hieroglyph, at the brow of the head-waiter. The evening, precursor of profound delight, spoiled, for him, the most succulent things.

The other, a wounded man of ambition, became, as the daylight faded, more bitter, gloomy, and sarcastic. Forgiving and sociable during the day, he was merciless in the evening; and it was not only towards others, but also towards himself, that this twilight mania was so furiously exercised.

The first died mad, incapable of recognising his wife or child; the second bears within him the inquietude of a perpetual malaise, and though he were gratified with all the honors republics or princes can confer, I believe twilight would still kindle in him a burning desire for imagined honours. The night, which brought its darknesses to their minds, brings light to mine; and, although it is not rare to see the same cause generate two contrary effects, it always intrigues and alarms me.

O night! O refreshing darkness! For me you are the signal of an inner celebration, a deliverance from anguish! You are, in the solitude of plains, in the stony labyrinths of a capital city, the scintillating stars, the bright explosions, the fireworks of the goddess Liberty!

Twilight, how sweet and tender you are! That rose-coloured light which still lingers on the horizon, like the agony of day at the victorious oppression of night, those flaring candelabras which stain in opaque red the last glories of the setting sun, those heavy draperies drawn by an invisible hand from the depths of the Orient, imitate all the complex feelings which struggle in the heart of man, in the most solemn hours of life.

One might even describe it as one of those strange dancers’ dresses, where a transparent black gauze allows a glimpse of the full splendor of a glittering skirt, past delight transpiercing the dark present; the tremulous stars of gold and silver, with which it is strewn, representing those fires of fantasy which only shine brightly beneath Night’s mourning robes.

23. Solitude (La Solitude)

A philanthropic journalist tells me that solitude is bad for human beings; and to support his thesis, he cites, like all unbelievers, the words of the Fathers of the Church.

I know that the Devil frequents arid places willingly, and that the Spirit of murder and lechery is set ablaze marvelously by solitude. But it may well be that such solitude is only dangerous for the idle and itinerant soul that populates it with its passions and chimeras.

It is certain that a speaker whose supreme pleasure consists of addressing us from the heights of a pulpit or platform, would be at great risk of running berserk, if he were on that isle of Robinson Crusoe’s. I do not demand of my journalist the courageous virtues of a Crusoe, but I ask that he not level accusations against lovers of solitude and mystery.

There are individuals among our chattering classes who would accept the ultimate fate with less reluctance, if they were allowed to deliver a copious harangue from the scaffold without fearing that the drum-roll ordered by the guards-captain, Santerre, would unexpectedly interrupt their speech.

I pity them not, since I suspect that their oratory effusions grant them a pleasure equal to those that others derive from silence and meditation; but I despise them.

I desire, above all, that my wretched journalist allows me to amuse myself in my own way. ‘So, you never feel the need,’ he asked me, in a most apostolic nasal tone, ‘to share your pleasure?’ Behold the subtle envy of this person! He knows that I disdain his, and tries to insinuate himself into mine, the vile spoilsport!

‘That great misfortune of being unable to be alone! …’ says La Bruyère somewhere, as if to shame all those who run to lose themselves in the crowd, doubtless fearing that they will prove unable to endure themselves.

‘Nearly all our misfortunes derive from not knowing how to stay in our own room,’ says another wise man, Pascal, I think, thus recalling to their meditative retreat all those panicked people who seek happiness in movement, and in a form of prostitution which I might call fraternal, if I wished to employ the fine language of my century.

24. Projects (Les Projets)

While walking in a vast solitary park, he said to himself: ‘How beautiful she would look, in a complex and sumptuous court dress, descending, amidst the atmosphere of a lovely evening, the marble steps of a palace, facing the wide lawns and fountains! Since, by nature, she has the air of a princess.’

Later, traversing a street, he halted before a shop selling engravings, and, finding, in one box, a print representing a tropical landscape, said to himself: ‘No! It is not in a palace that I would like to share her dear life. We would scarcely feel at home there. Besides, those walls adorned with gold would leave no space to hang her likeness; in those solemn galleries, there’s not a single private corner. Clearly, this landscape is where I should dwell wherein to cultivate my life’s dream.’

And, while analyzing, visually, the details of the engraving, he continued, thoughtfully: ‘At the edge of the sea, a neat wooden hut, enveloped by all these exotic glowing trees whose names I forget… an intoxicating, indefinable odour in the air… a hut filled with the powerful perfume of rose and musk… further away, behind our little domain, mastheads, swayed by the swell… around us, beyond the room lit with a rose-coloured light, dimmed by the blinds, decorated with fresh matting and heady flowers, with rare Portuguese rococo seats, of a heavy and dark wood (where she would rest, calm, fanned by the breeze, smoking tobacco blended with a mild opiate!), beyond the veranda, the cries of birds drunk with the light, and the chatter of little black girls….., and, at night, to serve as an accompaniment to my dreams, the plaintive musical whisper of the trees, the melancholy casuarinas! Yes, in truth, there is the setting I was looking for. What have I to do with palaces?’

Further on, as he followed a broad avenue, he came upon an inn, tidy in appearance, where two smiling faces leaned from a window brightened by colourful Indian curtains, and immediately said to himself: ‘My mind must be a vagabond indeed, to seek so far away what is so near to me. Pleasure and happiness are to be found in the first inn that comes along, in the inn of chance, so fecund with delight. A large fire, showy faience crockery, a passable supper, a bottle of rough wine, and a double bed with sheets that are somewhat coarse perhaps yet fresh; what better?’

And on returning home alone, at that hour when the counsels of Wisdom are no longer muffled by the hum of external life, he said to himself: ‘I possessed today, in dream, three dwellings in which I took equal pleasure. Why oblige my body to change its place of residence when my soul travels so nimbly? And why execute the project, when the mere conceiving of it provides sufficient enjoyment?’

25. The Lovely Dorothée (La Belle Dorothée)

The sun overcomes the city with its fierce and terrible light; the sand dazzles, and the sea shimmers. The stupefied world cowers and takes its siesta, which is a kind of delicious death where the sleeper savours the half-conscious pleasure of annihilation.

Meanwhile Dorothée, strong and proud as the sun, advances into the deserted street, the only person alive at this hour beneath the immense azure, a gleaming black shape in the light.

She advances, gently swinging her slim torso on wide hips, her silk dress clinging to her, its pale pink tone contrasting sharply with the darkness of her skin, and outlining, with exactness, the shape of her long waist, her hollow back, and her tapering throat.

Her red parasol, filtering the light, projects the crimson shadow of its reflections onto her dark face.

Her enormous mass of hair, which is almost blue in colour, pulls her delicate head back, and gives her a look of idle triumph. Heavy pear-shaped brilliants whisper, privately, into her charming ears.

From time to time, the sea breeze raises her flowing skirt by one corner, and reveals a superb glistening leg; while her foot, like those of the marble goddesses that Europe imprisons in its museums, faithfully prints its shape on the fine sand. For Dorothea is so prodigiously coquettish that the pleasure of being admired prevails over the pride of the liberated woman, and, though she is free, she walks shoeless.

She advances thus, harmoniously, happy to be alive and smiling a bright smile, as if she views a mirror, in the far distance, reflecting her approach and her beauty.

At the hour when the very dogs moan painfully in the sun that afflicts them, what powerful motive induces the idle Dorothea, beautiful and cold as bronze, to promenade thus?

Why has she left her little hut, so coquettishly arranged, whose flowers and mats make so perfect and inexpensive a boudoir; in which she takes so much pleasure in combing her hair, smoking, cooling herself or gazing into the mirrors set in her large feathered-fan, while the sea, which beats on the beach a hundred paces away, provides a powerful and monotonous accompaniment to her indecisive daydreams, and the iron pot, where a crab stew, made with rice and saffron, is heating, sends her, from the depths of the courtyard, its exciting perfumes?

Perhaps she has a meeting with some young officer who, on some distant shore, heard from his comrades about the famous Dorothée. She will not fail to beg him, being a simple creature, to describe for her the ball at the Opéra, and will ask if one can attend barefoot, as at the dances on Sundays, where even the old African women become wild and drunk with joy; and then, if the beautiful ladies of Paris are all more beautiful than her.

Dorothée is admired and pampered by everyone, and she would be perfectly happy if she were not obliged to pile coin on coin to buy back her little sister who is eleven years old, and who is already mature, and so beautiful! She will undoubtedly succeed, good Dorothée, the child’s master being so miserly, too miserly to understand any other beauty than that of wealth!

‘Three Tahitian Women’ - Paul Gauguin (French, 1848-1903)

Artvee

26. The Eyes of the Poor (Les Yeux des Pauvres)

Ah! You wish to know why I hate you today. It will undoubtedly be harder for you to understand than for me to explain; since you are, I believe, the finest example of feminine impermeability that one can encounter.

We had spent a long day together that seemed short to me. We had promised each other that all our thoughts would be mutual, and that our two souls would henceforth become one; — a dream which contains nothing in the least original, except that, dreamed by all men, it has been realised by none.

That evening, a little tired, you wished to sit down in front of the new café on the corner of the new boulevard, still full of rubble, yet already showing, gloriously, all its unfinished splendors. The café gleamed. Even the gas-light displayed the ardour of beginnings, and illuminated, in all its strength, the blindingly white walls, the brilliant sheets of mirrors, the gilding of the mouldings and cornices, the plump-cheeked page-boys dragged along by dogs on leashes, the ladies smiling at hawks perched on their fists, the nymphs and goddesses carrying fruits, pâtés, and game on their heads, the Hebes and the Ganymedes presenting with outstretched arms a small Bavarian amphora, or a bi-coloured obelisk of variegated iciness; all of history and all mythology placed at the service of gluttony.

Directly before us, in the roadway, stood a brave fellow, about forty years of age, with a weary face and a greying beard, clasping a little boy by one hand and carrying, on the other arm, a little creature who was too feeble to walk. He had assumed the office of a nursemaid, and was allowing his children to enjoy the evening air. All were in rags. Their three faces were extraordinarily serious, while three pairs of eyes stared, fixedly, at the new café, showing equal admiration, though nuanced variously according to age.