Geoffrey Chaucer

Troilus and Cressida

Book II

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2001, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

1.

Out of these black waves for to sail,

O wind, O wind, begin the weather to clear:

for in this sea the boat has such travail,

that with my cunning I can hardly steer.

This sea I call the tempestuous matter

of the despair that Troilus was in:

but now the first days of hope begin.

2.

O lady mine, you who are called Clio,

speed me from this time forward, be my muse,

to rhyme this book well, till I have so

done. I need no other art to use,

since, to every lover, I make excuse

that of my own feeling I take no flight,

but out of Latin into my own tongue write.

‘Clio’

Hendrick Goltzius, 1592

The Rijksmuseum

3.

Therefore I will have neither thanks nor blame

for all this work, but pray you humbly,

blame me not if any word be lame:

for as my author said, so say I.

And though I speak of love unfeelingly,

that is no wonder, for it nothing new is:

a blind man cannot judge well what the hue is.

4.

You know also that forms of speech change

within a thousand years, and words, lo!

that had a value, now wondrous odd and strange

we think them: and yet they spoke them so,

and did as well in love as men do now.

And to win love in sundry ages,

in sundry lands, there were sundry usages.

5.

And therefore whether it happens, anywise,

that there be any lover in this place,

that listens, as this story shall devise,

to how Troilus came to his lady’s grace:

and thinks, I would not love so purchase:

or wonders at his speech and his doing,

I cannot know: but for me there is no wondering.

6.

For every man that to Rome went

took not the same route, in the same manner:

and in some lands the game were lost to all intent,

if they did in love as men do here,

as open in their doings, or as they appear,

in their visiting, their formalities, or

in speech, as they say, each country has its law.

7.

And there have scarcely been in this place two

that have, in love, said and done like in all:

since for your purpose this thing may please you,

and you no way, yet say it all you do or shall.

And some men carve a tree, some a stone wall,

as it chances: but since I have begun,

I shall follow my author if I can.

8.

In May, that mother is of months glad,

when fresh flowers, blue, and white, and red,

quicken again, that winter has made dead,

and with balm is every meadow full fed:

when Phoebus does his bright beams spread

right in the white bull, it so occurred

as I shall sing, on May’s day the third,

9.

that Pandarus, for all his wise speech,

felt his own part of love’s shots so keen,

that though he could so well of loving preach,

it often made his colour by day true green:

it so chanced that on that day he had been

crossed in love, and with woe to bed he turned,

and before the day, in many a torment churned.

10.

The swallow, Procne, with a sorrowful lay,

when morning came began her lamenting,

why she new-altered was: and ever lay

Pandar in bed, half in a slumbering,

till she so near to him made her twittering

of how Tereus began her sister forth to take,

that with her noise he began to wake.

‘Procne Revealing Itys's Head to Tereus’

Wilhelm Janson (Holland, Amsterdam), Antonio Tempesta (Italy, Florence, 1555-1630)

The Rijksmuseum

11.

And began to call, and address himself to rising,

remembering the errand to be run

for Troilus, and his great undertaking:

and cast a chart, with good aspects for the moon

to do a journey, and took his way quite soon

to his niece’s palace close beside.

Now Janus, god of entries, be his guide!

‘Janus Opens the Door’

Robert van Audenaerd, after Carlo Maratti, 1685 - 1723

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art

12.

When he was come to his niece’s place,

‘Where is my lady?’ to her folk said he.

And they told him, and in he began to pace,

and found two other ladies sitting, and she

within a paved parlour: and the three

hearing a maiden reading the story to them

of the siege of Thebes, while it pleased them.

‘Siege of Thebes’

Epicteti Enchiridium una cum Cebetis Thebani tabula Graec. & Lat. (p226, 1723)

Gronovius, Jacobus, 1645-1716 Schröder, Johann Caspar Hooghe, Romeyn de, 1645-1708

Internet Archive Book Images

13.

Said Pandarus: ‘Madame, God bless thee,

and all your book and all the company!’

‘Ah, my uncle, welcome indeed,’ said she:

and up she rose, and by the hand, in a trice,

she took him fast, and said, ‘This night thrice,

may it turn to good, I dreamed of you!’

And with that word she sat him down too.

14.

‘Yes, niece, you will fare well and better too,

if God will, all this year,’ said Pandarus.

‘But I am sorry I have interrupted you

listening to the book you praise thus:

for God’s love, what does it say? Tell it us.

Is it of love? Oh teach me some good from there!’

‘Uncle, ‘she said, ‘your mistress is not in here.’

15.

At that they laughed and then she said:

‘This romance is of Thebes that we read:

and we heard about King Laius who is dead

through Oedipus his son, and all that deed:

and here we stopped at these letters red,

how the bishop (as the book can tell)

Amphiaraus, fell through the ground to hell.’

16.

Said Pandarus: ‘All this I know myself,

and all the siege of Thebes, its woe and care:

for there have been made out of it books twelve.

But let this be and tell me how you are:

Away with your veil, and show your face bare:

Away with your book, rise up, and let us dance,

and let us show the May month’s observance.

17.

‘Ah, God forbid,’ she said, ‘are you mad?

Is that the life a widow has, God save?

By God, you fill with me such dread,

you are so wild, it seems as if you rave.

It would suit me better in a cave

to rest, and read on holy saint’s lives:

let maidens go and dance, and young wives.

18.

‘As ever I may thrive,’ said Pandarus,

‘I could still tell a thing to make you play.’

‘Now uncle dear,’ she said, ‘tell it us

for God’s love: is the siege then done away?

I am so fearful of Greeks that I die.’

‘No, no,’ he said, ‘as ever I may thrive!

It is a thing of those worth any five.’

19.

‘Ah, holy God!’ she said, ‘what thing is that?

What! Better than any five such? Oh, no, I guess!

For all the world I cannot imagine what

it could be: some jest, I think, is this:

and, unless you yourself say what it is,

my wit is far too slender, far too lean:

so help me God, I know not what you mean.’

20.

‘And I tell you, that never shall by me

this thing be told to you, so may I thrive.

‘And why so, uncle mine, why so?’ said she.

‘By God,’ he said, ‘that I will tell as blithe:

for there would be no prouder woman alive,

if you knew it, in all the town of Troy:

I jest not, if ever I might have joy.’

21.

The she began to wonder more than before

a thousand fold, and down her eyes cast.

For never, since the time she had been born,

had she so desired to know a thing, and fast:

and with a sigh she said to him at last:

‘Now, uncle mine, I will not tease you,

nor ask again what may displease you.’

22.

So after this with many words glad,

and friendly tales, and with merry cheer

they played and entered into this and that

of many a strange and glad and deep matter,

as friends do when they meet together,

until she began to ask how Hector fared

that was the town’s wall and the Greeks’ scourge.

23.

‘Full well, I thank God,’ said Pandarus,

‘except that in his arm he has a little wound:

and so is his brave brother Troilus

the wise, a worthy Hector the second,

in whom every virtue likes to abound,

as all truth, and all gentleness,

wisdom, honour, freedom, and worthiness.’

24.

‘In good faith, uncle,’ she said, ‘that I like:

they fare well, God save both the two!

For truly I hold it fitting and right

a king’s son in arms well to do,

and to have good qualities too.

For great power and moral virtue here

are seldom seen in one person clear.

25.

‘In good faith that is so,’ said Pandarus:

but in truth the king has two sons say I,

that is to say, Hector and Troilus,

that certainly, though I should die,

are as void of vices, without lie,

as any men that live under the sun,

their might and knowledge is well known.

26.

Of Hector there is no need to tell:

in all this world there is no better knight

than he, that is of worthiness a well:

and he has still more virtue than might.

This is known by many, worthy and right.

The same praise has Troilus, I say to you.

God help me so, I know not such a two.’

27.

‘By God,’ said she, ‘of Hector that is true:

of Troilus the same belief have I.

For certain, men say that he too

in arms does day by day so worthily,

and bears him here at home so courteously

to everyone, that all the praise has he

of them that I would most wish to praise me.’

28.

‘You speak the truth, I think, ‘ said Pandarus,

for yesterday whoever is with him and sees,

he might have wondered at Troilus:

for never yet so thick a swarm of bees

flew, as the Greek from him flees.

And through the field, in every man’s ear,

there was no cry but ‘Troilus is here!’

29.

‘Now here, now there, he hunted them so fast,

there was but Greeks’ blood; and Troilus,

now he hurt them, and them all down he cast:

ay, where he went it happened thus:

he was their death, and shield and life to us:

so that that day there was no one dare withstand

him as he held his bloody sword in hand.

30.

Add too that he is the friendliest man

of great position I ever saw in my life:

and whenever he wishes, best fellowship can

offer to such as he thinks worthy to thrive.’

And with that word then Pandarus, as blithe,

took his leave and said: ‘I will go hence.’

‘No, I would be to blame, my uncle,’ said she then.

31.

‘What makes you weary thus so soon,

especially of women? Will you so?

No sit down: by God I have business with you,

for you to speak your wisdom before you go.’

And everyone who was near to them so,

hearing that, began far from them to stand,

while those two dealt with what they had on hand.

32.

When the story was all brought to an end

about her estate and its governance,

Pandarus said: ‘Now it is time I went:

but still I say, rise and let us dance,

and cast your widow’s dress, at a chance:

why do you wish yourself to disfigure,

since to you has fallen so fine an adventure?’

33.

‘Ah, well remembered, for love of God’ said she,

‘shall I not learn what you mean by this?’

‘No this thing needs leisure,’ then said he,

‘and it would grieve me greatly, as it is,

if I told it and you took it amiss.

Yes, it were better to hold my tongue still

than say a truth that was against your will.

34.

For niece, by the Goddess Minerva,

and Jupiter, who makes the thunder ring,

and by the blissful Venus that I serve,

you are the woman, in this world living,

except my lovers, to my knowing,

that I best love, and loathest am to grieve:

and that you know yourself, I believe.’

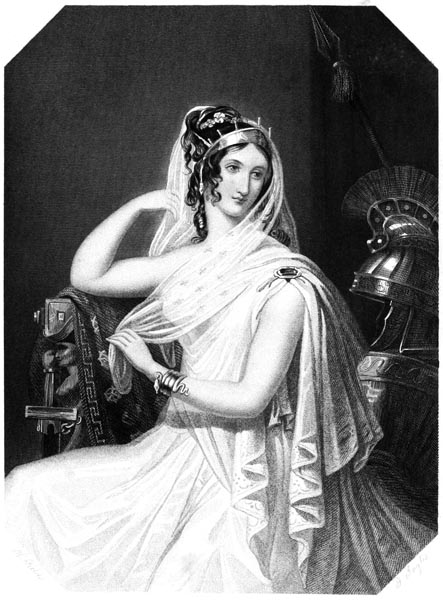

‘Minerva’

Jan Harmensz. Muller, 1598 - 1602

The Rijksmuseum

35.

‘I know, my uncle,’ she said, ‘grant mercy:

I have ever found your friendship true:

I am to no man beholden truly,

so much as you, and have so little repaid you:

and with the grace of God, if I can so do,

through my own fault, I’ll never you offend,

and if I have before now, I’ll make amend.

36.

But for the love of God I you beseech,

as you are him whom I most love and trust,

leave off your obscure manner of speech,

tell all to me, your niece, as you must.’

And with that word her uncle now her kissed,

and said: ‘Gladly, beloved niece, my dear,

take in good part all that I tell you here.’

37.

With that she began her eyes down to cast,

and Pandarus began to cough a mite,

and said: ‘Niece, always, lo! at the last,

however much some men take delight

with subtle art their tales to make bright,

yet, for all that, in their intention,

their tale is all to form a conclusion.

38.

And since the end is every tale’s strength,

and the end of this matter looks so fittingly,

why should I paint it or draw it out at length

to you, who have been my friend so faithfully?’

And with that word he began inwardly

to behold her, and gaze upon her face,

and said: ‘On such a mirror fall such grace!’

39.

Then thought he thus: ‘If I my tale spin

too long, or make procession any while,

it will be one she’ll take less pleasure in,

and think I would her willfully beguile.

For tender wits think all a cunning wile

that they cannot plainly understand:

so I must find the glove to fit the hand.’

40.

And he looked at her quite intently,

and she was aware that he beheld her so,

and said: ‘Lord! So closely you study me!

Did you not know me till now? What say you? No?’

‘Yes, yes,’ he said, ‘and better before I go:

but by my truth I wondered now if ye

have had good luck, for now men shall it see.

41.

For everyone some goodly adventure

is sometimes shaped, if he can receive it:

and if when it comes he chooses to ignore

it willfully, and take no notice of it,

lo, neither chance nor fortune cause it,

but simply his own sloth and wretchedness:

and such a one is to be blamed, I guess.

42.

Good adventure, O fair niece, have ye

readily found, if you can it grasp:

and for the love of God and of me

seize it now lest adventure lapse.

Why should I longer story of it make?

Give me your hand for in this world is none

if this pleases you, who fortune so shines on.

43.

And since I speak with good intention

as I have told you truly here before,

and love as truly your honour and renown,

as that of any creature to this world born:

by all the oaths that I have you sworn,

if you are angered or think these lies,

I shall never see you again with these eyes.

44.

Do not be aghast or quake: why should you?

and do not change, from fear so, your hue:

for indeed, the worst of this is through.

And though my tale as now be to you new,

yet trust me always, and you will find me true:

and if it were a thing I thought unfitting,

to you I would not such a tale bring.’

45.

‘Now my good uncle, for god’s love I pray’

she said, ‘Be quick and tell me what it is:

since I am both aghast at what you’ll say,

and yet also I long to know of this.

For whether it be good or something amiss

say on, let me not in this fear dwell.’

‘So I will do: now listen, I shall tell.

46.

Now, my niece, the king’s dear son,

the good, wise, worthy, fresh and free,

who always wishes what he does well done,

the noble Troilus, so loves thee,

that, unless you aid him, it will his bane be.

Lo, here is all of it, what more say I?

Do what you will, to make him live or die.

47.

But if you let him die, I’ll take my life:

have here my truth, niece: I will not lie,

I would cut my throat with this knife.’

At this the tears burst from his eyes,

and he said: ‘If you cause us both to die,

both guiltless, then good fishing you’ve enjoyed.

What do you gain if we are both destroyed?

48.

Alas, he who is my lord so dear,

that true man, that noble gentle knight,

who desires nothing but your friendly cheer,

I see him dying though he stands upright:

and hastens on, with all his might,

to be cut down, if fortune gives assent.

Alas that God you such beauty sent!

49.

If it be so that you so cruel be

that in his death you no take no interest

(he so true and worthy, as you see),

no more than that of trickster or of wretch:

if you be such, your beauty may not stretch

as far as atonement for so cruel an act:

it is good to consider well before the fact.

50.

Woe to the fair gem that is virtueless!

Woe to the herb also that does no good!

Woe to that beauty that is ruthless!

Woe to the man who treads others underfoot!

And you, that are of beauty the crop and root,

if, with all that, in you there is no ruth,

then it’s sad you are alive, by my truth.

51.

And also think well that this is no fraud:

for I would rather you and I and he

were hanged, than that I should be his bawd,

so high that men might all openly us see.

I am your uncle: it would be shame to me,

as well as you, if I gave assent,

through abetting him, and he your honour rent.

52.

Now understand, that I do not desire

to bind you to him formally,

but only that you show him better cheer

than you have done till now, and be

more kind, so his life is saved, at the least.

This all and some, and plainly, is my intent.

God help me so, I have no other meant.

53.

Lo this request is reasonable, it is:

there is no cause for doubt, by God no:

I think the worst that you might dread is this,

that men would wonder to see him come and go:

Against that I straight away argue so,

that ever man, unless he’s a fool by kind,

will judge it friendship’s love in his mind.

54.

What? Who will judge, though he see a man

to temple go, that he the images eat?

Think, then, how well and wisely he can

govern himself, that nothing he forgets,

that, where he comes, praise and thanks he gets:

and add to that, he shall come here so seldom,

what matter that all the town beheld him?

55.

Such love between friends rules all this town:

and hide yourself with that cloak, forever so:

And as God is ever my salvation,

as I have said, your best is to do so,

but always, good niece, to soothe his woe,

soften a little your disdain,

that for his death you are not to blame.’

56.

Cressida who heard him speak in this wise,

thought: ‘I shall find out what his meaning is.’

‘Now uncle,’ she said, ‘what would you devise,

what do you think I should make of this?’

‘That is well said,’ he answered: best it is

for you to love him again for his loving,

as love for love is just rewarding.

57.

Think then how age wastes, every hour,

in every one of you, a part of beauty:

and therefore, before age you devours,

go love, for old no man will want thee.

Let this proverb as a law to you be:

“ ‘Aware too late’, said Beauty, ‘when it’s past.’ ”

And age defeats disdain at the last.

58.

The king’s fool is given to cry aloud,

when he thinks a woman is too high:

“So long may you live, and just as proud,

till the crow’s-feet grow under your eye,

and send for a mirror then for you to pry

in, where you may see your face tomorrow!”

Niece, I cannot wish you greater sorrow.’

59.

With this he ceased, and cast down his head

and she burst out weeping at once,

and said: ‘Alas, for woe! Why am I not dead?

For in this world all faith is gone.

Alas what would strangers to me have done

when he I thought the best friend to me,

tells me to love, yet should forbid me?

60.

Alas! I could have trusted, doubtless,

that if I through any misadventure

had loved either him, or Achilles,

Hector or any mortal creature,

you would have had of mercy no measure

for me, but always reproached me,

this false world, alas!, who may it believe?

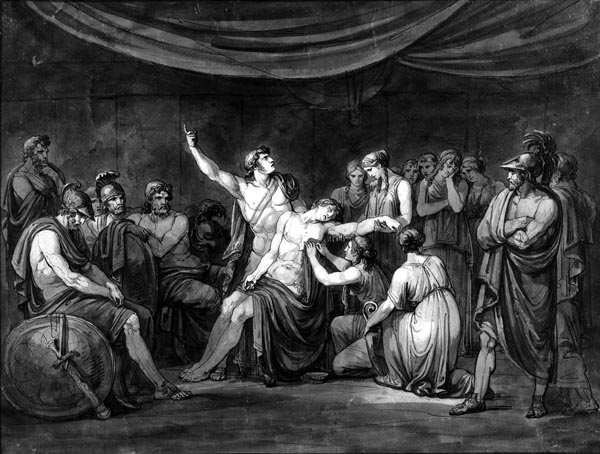

‘Achilles Swears an Oath to Avenge the Dead Patroclus, Killed by Hector’

Bartolomeo Pinelli, Italian, 1781 - 1835

Yale University Art Gallery

61.

What? Is this all the joy and all the feast?

Is this your counsel: is this my blissful case?

Is this, of your promise, the true bequest?

Is all this specious argument, alas,

only for this sin? O lady mine, Pallas,

you in this dreadful case for me provide,

for I am so astonished that I die.’

62.

With that she began sorrowfully to weep.

‘Ah, can you do no better?’ said Pandarus:

‘By God, I shall come here no more this week:

not, before God, if I am mistrusted thus.

I see full well you care little for us,

or of our death. Alas! I’m a sad wretch!

If he might live, it’s no matter where I fetch.

63.

O cruel god, O merciless Mars,

O Furies Three of hell, to you I cry

never let me out of this house depart,

if I meant any harm or villainy!

But since I see my lord must needs die,

and I with him, here I confess, and say I

that wickedly you cause us both to die.

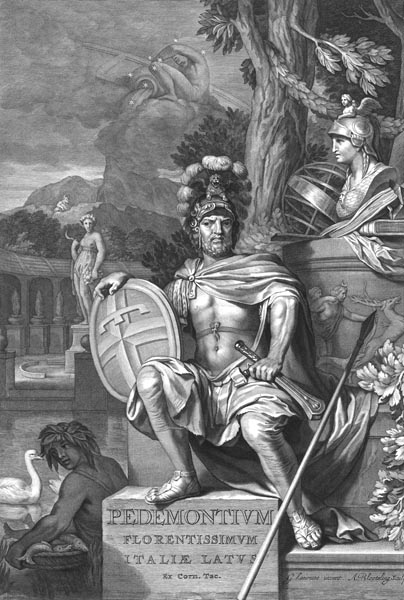

‘Mars’

Abraham Bloteling, after Gerard de Lairesse, 1682

The Rijksmuseum

64.

But since it pleases you that I be dead,

by Neptune, that is god of the sea,

from this time forth I never shall eat bread

until my own heart’s blood I see:

for certain, I shall die as soon as he.’ –

And up he started, and his way he sought,

till she again him by the sleeve caught.

‘Neptune Stabbing a Sea Horse’

Maarten van Heemskerck, c. 1550 - c. 1560

The Rijksmuseum

65.

Cressid, who was well nigh dead of fear,

as she was the fearfullest one there might

be, and not only heard in her ear,

but saw, the sad earnestness of the knight,

and in his prayer nothing but what was right,

and the more harm that might befall, as he said,

she began to relent, and was sore afraid.

66.

And thought thus: ‘Misfortunes fall thickest

always, for love, and in such manner because

men are cruel in themselves and wicked.

And if this man should kill himself, alas!

in my presence, that will be no solace.

What men would think of it I cannot say:

it behoves me with great subtly to play.’

67.

And with a sorrowful sigh she said times three:

‘Ah, lord! To me has fallen such mischance!

For my estate now lies in jeopardy,

and my uncle’s life lies in the balance,

but nonetheless, with God’s governance,

I shall do so, that my honour I shall keep,

and he his life’: and she ceased to weep.

68.

‘Of two harms, the lesser is the one to choose:

I would rather show him some good cheer,

in honour, than my uncle’s life to lose.

You say you nothing else of me require?’

‘No indeed,’ he said, ‘my own niece dear.’

‘That’s well,’ she said, ‘and I will take great pain:

I shall my heart against my will constrain.

69.

‘But I will not show him a false hand:

I cannot ever love a man, nor may

against my will: otherwise, I will be fond,

saving my honour, and please him from day to day:

I never once would have wished to say nay

to it, except for fears that are but fantasy.

But ceaseth the cause: ceaseth the malady.

70.

And here I make a protestation,

that in this process if you deeper go,

for certain, not for your preservation,

though you are dying, both of you,

nor though all the world that day is my foe,

will I ever for him show greater ruth.’

‘I accept that,’ said Pandar, ‘by my truth.

71.

‘But may I have a perfect trust,’ said he,

‘that in this thing you promise to me here,

you will keep to it, truly, for me?’

‘Yes, certainly,’ she said, ‘my uncle dear.’

‘And that I shall have no cause in this matter,’

‘he said, ‘to complain at you, or preach?’

‘Why, no, indeed: what need of further speech?’

72.

Then they fell to talking of other tales glad,

till at the last, ‘O good uncle,’ she said, ‘so,

for love of God that both of us has made,

tell me how you first learnt of his woe:

does no one know but you?’ He said: ‘No.’

‘Can he speak well of love?’ she said, ‘I pray

tell me, that I may better myself array.’

73.

Then Pandarus began a little to smile,

and said, ‘By my truth, you I will tell.

The other day, but past a little while,

in the palace garden, by a well,

he and I spent half a day, so it fell,

purely to speak about a strategy

to defeat the Greeks and make the victory.

74.

Soon after that we began to leap,

and hurl our spears, to and fro,

till at the last he said he would sleep,

and on the grass he laid himself down, so:

and I began to roam, to and fro,

till I heard, as I walked alone,

how he began woefully to groan.

75.

Then I began to tread softly behind,

and certainly, and truth to say,

as I recall again to my mind,

he began, to Love, thus to complain.

and said: “Lord have pity on my pain,

though I have been a rebel in intent:

now mea culpa, lord! I repent.

76.

O God, who at your discretion

decree the death, by just providence,

of everyone, my humble confession

accept with favour, and send me such penance

as pleases you: but from despair’s lance

(that may separate my soul from thee),

be you my shield, in your benignity.

77.

For certain, Lord, she has me so sore wounded

who stood there in black, with the gaze of her eye,

that to my heart’s depth it has sounded,

because of which I know that I must needs die.

This is the worst thing: I dare not show why:

and all the hotter the coals glow red,

that men cover with ashes pale and dead.”

78.

With that he dropped his head straight down,

and began to mutter, I know not what, truly.

And I at that began to turn around:

and acted as if no knowledge of it had I:

and came again and stood nearby,

and said: “Awake! you sleep far too long:

it seems that love does not make you to long,

79.

who sleeps so deep no man can you wake.

Who ever saw before so dull a man?”

“Well, friend,” he said, “let your head ache

for love, and let me live as I can.”

But though, for woe, he was pale and wan,

yet he showed then as fresh a countenance

as though he were leading off the next dance.

80.

This lasted, until, the other day,

it happened I came roaming all alone

into his chamber, and found that he lay

on his bed: but such a human groan

I never heard, and what was his moan

I know not: since, as I was nearing,

all suddenly he left off his complaining.

81.

which filled me with some suspicion,

and I came near, and found he wept sore

and, as God is, I know, my salvation,

I never felt pity for anyone more.

For neither with invention, nor lore,

could I for certain him from death keep:

so that for him I still feel my heart weep.

82.

And God knows never since I was born

did I preach so hard to any man before,

and never was to any man so sworn,

before he told me, who could be his cure.

But now to rehearse to you all his speech,

or all his woeful words for me to sound,

don’t bid me, or I’ll fall to the ground.

83.

But to save his life, and not for ought

else, and not to harm you, I so labour:

and for the love of God, who has us wrought,

so that he and I might live, show him great favour.

Now have I plainly opened my heart to yours:

and since you know that my intent is clean,

take note of it, for I no evil mean.

84.

And right good luck, I pray to God, have you,

who have caught such a one without a net:

if you are wise as you are fair to view,

then in the ring is the ruby well set.

There will never be two so well met,

when you are wholly his, as he is yours:

may mighty God grant that we see those hours!’

85.

‘No, I spoke nothing of that, ah!’ said she,

‘God help me, you twist everything so.’

‘O mercy, dear niece,’ quickly answered he,

‘Whatever I said I meant for well not woe,

by Mars the god, who with steel helmet goes.

Now do not be angry, my blood, niece dear.’

‘Well now,’ she said, ‘it is forgiven here.’

86.

With this he took his leave, and home he went:

and lord! how he was glad, well satisfied.

Cressid arose, delaying not a moment,

but straight into her closet she did glide,

and still as a stone sat her down inside,

and every word he had said began to wind,

up and down, as it passed through her mind:

87.

and some astonishment possessed her thought,

in that new situation. But when she

fully considered it, she found nought

perilous, or why in fear she ought to be,

for man may love the possibility

of a woman so, his heart may burst in two,

yet she not love him again, unless she choose.

88.

But as she sat alone and thought thus,

the sound rose of a skirmish, from without,

and men cried in the street: ‘See, Troilus

has just now put the Greek horde to rout!’

With that all her household began to shout:

‘Ah, come and see, open the lattice wide,

for through this street he must to the palace ride:

89.

from that gate, another way there’s none,

of Dardanus, where open is the chain.’

With that he came with all his folk at once

at easy pace, riding in groups twain,

happy, as this, his day, was, truth to say,

wherefore, as men have it, may not altered be

all that must happen of necessity.

90.

This Troilus sat on his bay steed,

all armed, save his head, full richly,

and his horse was wounded (and began to bleed)

on which he rode at gentle pace full softly.

But such a knightly sight, truly,

as to look on him, was without fail,

to look on Mars, that is god of war’s tale.

91.

So like a man of arms and a knight

he was seen, full of high prowess:

for he had both the body and the might

to do the thing, as well as hardiness.

And then to see him in his armour dressed,

so fresh, so young, so active seemed he,

it was a very heaven him to see.

92.

His helmet was cut through in twenty places,

that by a cord hung down his back behind:

his shield was scarred, by swords and by maces,

in which men might many an arrow find

that had pierced horn, and sinew and rind.

And ever the people cried: ‘Here comes our joy,

and, next his brother, holder-up of Troy.’

93.

For which he blushed a little red for shame

(when he heard the people on him cry),

so that to see it was a noble game,

how soberly he cast down his eye.

Cressida began on his looks to spy,

and let them so softly into her heart sink,

that to herself she said: ‘What do I drink?’

94.

For with her own thought she blushed all red,

remembering truly thus: ‘Lo, this is he

that my uncle swears must soon be dead

unless I have mercy on him and pity.’

And with that thought, for pure shame, she

began to draw in her head, and fast,

while he and all the people passed.

95.

And began to cast about, roll up and down,

within her thought, his excellent prowess,

and his state, and also his renown,

his wit, his form, and his nobleness:

but most in favour was that his distress

was all for her, and she though it a ruth

to kill such a man, if he meant it in truth.

96.

Now might some envious person mutter thus:

‘This was a sudden love: how can it be

that she so easily loved Troilus

right at first sight, yes, very easily?

Now, who says it, never prosper thee!

For everything has to begin somehow

before it can be done, without a doubt.

97.

For I do not say that she so suddenly

gave him her love, but that she inclined

to like him first, and I have told you why:

and after that his manhood, how he pined,

made love within her dig his mine,

by which due process and by good service

he won her love, and not with suddenness.

98.

And also blissful Venus well arrayed

sat in her seventh house of heaven so,

well disposed, and good aspects made,

to help poor Troilus in his woe.

And truth to tell she was not a foe

to Troilus either, at his nativity,

God knows, and all the quicker prospered he.

99.

Now let us leave off Troilus for a throw,

who rides away, and let us turn fast

to Cressida, who hung her head full low,

where she sat alone, and began to cast

her thought on how to behave at the last,

if it so was, her uncle would no less

for Troilus, on her, continue to press.

100.

And lord! so she began in her thoughts to argue

this matter, the which I have you told,

of what was best to do, and what eschew,

thoughts she plaited often in many a fold.

Now her heart was warm, now it was cold:

and what she thought, a little of it I’ll write,

as much as my author has brought to light.

101.

She thought it good that Troilus’s person

she knew by sight, and so his nobleness,

and thus she said: ‘Though it is not done

to grant love so, yet given his worthiness,

it would be honour with light heart and gladness,

in honesty, with such a lord to deal,

for my support, and also for his weal.

102.

I know indeed my king’s son is he:

and since in seeing me he takes delight,

if I were his sight utterly to flee,

perhaps he might hold me in despite,

through which I might end in a worse plight.

Now would I be wise, hate to purchase,

without need, where I might meet with grace?

103.

In everything, I know, there is measure.

For though a man forbids drunkenness,

he does not forbid that every creature

be drink-less forever, or so I guess.

And since I know that I cause his distress,

I ought not for that him to despise,

since it is true he means well in my eyes.

104.

And moreover I have known for a long time gone

his character is good, and he’s not foolish.

Nor a boaster, men say, certain he’s none:

he is too wise to enter into vice:

nor will I ever him so cherish

that he may boast of it, with just cause:

he will never bind me to such a clause.

105.

Now the worst case of all indeed is,

that men might think that he loved me:

what dishonour would it be to me, this?

Can I stop him doing it? No indeed!

I know also, and often hear and see,

men love women all this town about:

be they the worse? Why no, there is no doubt.

106.

I think also how he might have

of all this town the loveliest

to be his love, and she her honour save:

for out and out he is the worthiest,

except for Hector, who is the best.

And yet his life lies all in my care:

but such is love, and destiny’s affair.

107.

That he loves me, a wonder that is not:

since I well know myself, God prosper me,

although I wish no one to know my thought,

I am one of the fairest, there might be

and goodliest, to any man who can see:

and so men say in all the town of Troy.

What wonder is it if in me he joy?

108.

I am my own mistress, quite at ease,

I thank God, as befitting my state:

young, and free in meadows that please,

without jealousy or fierce debate.

No husband shall say to me, “checkmate!”

For either they are full of jealousy,

or masterful, or chasing novelty.

109.

‘What shall I do? To what purpose live I thus?

Shall I not love, if that pleases me best?

What, heaven knows! I am not religious!

And though I settle my heart to rest

upon this knight, who is the worthiest,

keeping always my honour and my name,

in all justice, it will do me no shame.’

110.

But just as when the sun shines bright

in March, that often changes face,

and a cloud is born with the wind in flight

to overspread the sun for a space,

a cloudy thought through her soul began to pace,

that overspread her bright thoughts all,

so that for fear she almost began to fall.

111.

The thought was this: ‘Alas! Since I am free,

should I love now, and put in jeopardy

my independence, enslave my liberty?

Alas! How dare I think on that folly?

Can I not well in other folk espy

their fearful joy, their distress, their pain?

None loves, without some reason to complain.

112.

For love is yet the most stormy life,

in its own self, that ever was begun.

Ever some mistrust or foolish strife

is there in love, some cloud is over the sun,

so that we wretched women get nothing done

when we are woeful, but weep and sit and think:

our misfortune is that we our own woes drink.

113.

Also these wicked tongues we can trust

to do us harm, and men are so untrue,

that, as soon as ceased is their lust,

so ceaseth love, and they go to love a new:

but harm once done is done, however we rue.

For though these men, for love, at first them rend,

too sharp a beginning, often breaks at the end.

114.

How many times has it been known to me,

the treason, that to woman has been done?

To what end such love is, I cannot see,

or what becomes of it when it is gone.

There is no one that knows, I think though,

what becomes of it: lo, no one learns:

what first was nothing, into nothing turns.

115.

How careful, if I love then, I must be

to please those that chatter of love and condemn,

and stop them from saying harm of me.

For though there be no cause, it seems to them

that all is harmful if folks please their friend.

And who can stop every wicked tongue,

or the sound of bells when they are rung?’

116.

And after that her thought began to clear,

and she said: ‘He that nothing undertakes

nothing achieves, however he holds it dear.’

And with another thought her heart quakes:

then hope sleeps, and after it fear awakes,

now hot, now cold: but thus between the two

she rose up and went off to her play.

117.

Down the stair straight away she went

into the garden with her nieces three

and up and down there, to their heart’s content,

Flexippe, she, Tharbe, and Antigone,

played so that it was a joy to see:

and other of her women, a great rout,

followed her in the garden all about.

118.

This yard was large, and all the alleys railed,

and well-shadowed with blossomy bowers green,

and new-benched, and sanded all the ways,

in which they walked, arm in arm between:

till at the last Antigone, fair to be seen,

began a Trojan song to sing out clear,

so that it was heaven her voice to hear.

119.

She sang: ‘O love, to whom I have and shall

been a humble subject, true in my intent,

to you, as best I can, lord, I give all

my heart’s desire, as tribute, ever meant,

for never has yet your grace to any sent

such blissful cause as me, my life to be led

in all joy and surety, free from dread.

120.

You blissful God have so disposed of me

in love, and well, that all that bears life

could not imagine how it should bettered be.

For, lord, without jealousy or strife,

I love one who is the most alive

to serve me well, unweary and unfeigning,

that ever was, and least harm entertaining.

121.

As he is the well of loyalty,

the ground of truth, mirror of seemliness,

Apollo of wit, stone of security,

virtue’s root, finder and head of happiness,

through whom all my sorrow is made less,

so then, I love him best, and he does me:

now good luck to him, wherever he may be.

‘Apollo and the Muses’

Pieter Sluyter, after Louis de Châtillon, Charles de Lafosse, 1693

The Rijksmuseum

122.

Whom should I thank but you, god of Love,

for all this bliss where to bathe I begin?

And thank you, lord, that I am in love.

This is the true life that I am in,

to banish every kind of vice or sin.

This makes me to virtue so attend,

that, day by day, by my will, I amend.

123.

And whoever says that loving is vice

or slavery, though he feels in it distress,

he either is envious or overnice,

or is unable, through his brutishness

to love: for such manner of folk, I guess,

defame love, who nothing of him know:

they speak, but they never bent his bow.

124.

What? Is the sun worse, in proper light,

though a man, through feebleness of eye,

cannot endure to see it full and bright?

Or is love worse, though wretches on it cried?

No goodness of worth that sorrow has not tried.

And for sure, he who has a head of glass,

should beware of any hostile stones that pass!

125.

But I with all my heart and all my might,

as I have said, will love till the last,

my dear heart, and my own knight,

to whom my heart is bound so fast,

and his to me, that it will ever last.

Though I feared at first to love him, to begin,

now I well know, there is no harm within.’

126.

And with that word her song reached its end,

and with it, ‘Now, niece,’ said Cressid,

‘Who made this song with such good intent?’

Antigone answered at once and said:

‘Madam, for sure, the loveliest maid

of high estate in all the town of Troy:

who leads her life in greatest honour and joy.’

127.

‘Certain, it seems so, by her song,’

said Cressid then, and began at that to sigh,

and said: ‘Lord, is there such bliss among

these lovers, as they so sweetly write?’

‘Yes, truly,’ said fair Antigone, the bright,

‘for all the folk that have been or are alive

cannot the true bliss of love describe.

128.

But think you every wretch knows what

this perfect bliss of love is? Why no:

they think all is love, if one part be hot:

no way, no way! Nothing of it they know.

Men must ask the saints if there is

anything fair in heaven. (Why? They can tell.):

and ask the fiends, “is it foul in hell?”’

129.

Cressid to that subject nothing answered,

but said: ‘Yes, night is falling fast.’

But every word of hers that she had heard,

she began to imprint in her heart fast:

and love began to make her less aghast

than before, and sank into her heart,

so that she found it easier to start.

130.

The day’s honour and the heaven’s eye,

the night’s foe (all these I call the sun)

began to set fast, and downward slide,

like one who had his day’s course run:

and white things became shadowy and dun

for lack of light, and stars to gather,

so she and all her folks went in together.

131.

So when it pleased her to go to her rest,

and they had left her presence all who ought,

she said that she was ready to sleep at last.

Her women soon to her bed her brought.

When all was hushed, then lay she still and thought

of all this thing, the manner and the wise,

it need not be rehearsed, for you are wise.

132.

A nightingale upon a cedar green,

under the chamber wall in which she lay,

sang full loud against the moonlight’s sheen,

perhaps, in his bird’s fashion, a lay

of love, that made her heart fresh and gay.

She hearkened to it so long with sweet intent,

that into a deep sleep at last she went.

133.

And as she slept, straight away she dreamed

that an eagle, feathered white as bone,

under her breast his long claws reamed,

and rent out her heart, it was done,

and his heart into her breast was gone:

at which she felt neither fear nor smart,

and forth he flew, leaving heart for heart.

134.

Now let her sleep, and we’ll the tale unfold

of Troilus, who to the palace rode,

from the skirmishes, of which I told,

and in his chamber sat, and there abode

till two or three of his messengers took the road

to Pandarus, and sought him out full fast,

till they had found him, and brought him at the last.

135.

At this Pandarus came running in at once,

and said: ‘Who did the Greeks well beat

today with swords and sling-stones,

but Troilus, who has the fever’s heat?’

And began to jest, and said: ‘Lord, how you sweat!

But rise and let us eat then go to rest.’

And he answered him: ‘We’ll do as you wish.’

136.

With as proper a haste as they might

they sped them from supper to bed:

and every man out of the door took flight

and where he wished upon his way he sped:

but Troilus, who felt how his heart bled

for woe until he had heard some tiding,

said: ‘Friend, shall I weep now, or sing?’

137.

Said Pandarus: ‘Lie still and let me sleep,

and put on your hood, all’s well with thee:

and choose if you will sing or dance or leap:

in brief words, you will have to trust in me:

Sir, my niece will do well by thee,

and love thee best, by God and by my truth,

unless from sloth you fail in the pursuit.

138.

‘For so far forth have I your work begun,

from day to day, until this very morrow,

her love, in friendship, have I to you won,

and she’s pledged her faith: on it you can borrow,

therefore one foot is lamed of your sorrow.’

Why should I any longer a sermon hold?

What you have heard before: all that he told.

139.

But just as flowers, through the cold of night

all closed, drooping on their stalks so low,

stand erect again when the sun is bright,

and spread their blooms by nature in a row,

jus so he began his gaze upwards to throw

this Troilus, and said: ‘O Venus dear,

your power, your grace, praised be it here.’

140.

And to Pandar he held up both his hands

and said: ‘Lord, all is yours that I have:

for I am free, all broken are my bands.

Whoever a thousand Troys me gave,

one after another, God me save,

could not gladden me so: Lo, my heart,

it swells so for joy, it will burst apart.

141.

But lord, what should I do, how shall I live?

When shall I next my dear heart see?

How shall this long time away be driven,

till you are gone again to her from me?

You may answer, “Abide, abide!” but he

who is hanging by the neck, truth to say,

abides in great torment filled with pain.’

142.

‘Be easy now, for the love of Mars,’

said Pandarus: ‘for all things have their time:

abide as long as it takes the night to depart.

For just as surely as you lie here by me,

by God, I will be there at morning prime,

and therefore do as I shall say,

or on some other man this charge lay.

143.

For, by heaven, God knows, I have ever yet

been ready to serve you, and to this night

have nothing feigned, but with all my wit

done all your wish, and shall with all my might.

Do now as I shall say and fare aright:

but if you will not, blame yourself for your cares,

no fault belongs to me if your luck evil shares.

144.

I well know you are wiser than I

a thousand times: but if I were you,

God help me so, I would decidedly,

in my own hand, write to her right now

a letter, in which I would tell her how

I fared amiss, and beseech her pity.

Now help yourself, and shake off lethargy.

145.

And I myself will, with it, to her go:

and when you know that I am with her there,

mount on your charger and then so

yes, boldly, dressed in your best gear,

ride right by the place, as if it were

by chance, and if I can you’ll find us sitting

at a window onto the street looking.

146.

And if you wish, then you may us salute,

and upon me direct your countenance:

but, by your life, beware, be too astute

to linger there: God shield us from mischance!

Ride on your way, and hold your governance.

And we will talk of you somewhat, I know,

when you are gone, to make your ears glow.

147.

Touching your letter, you are wise enough:

I would not pretentiously try it:

by using arguments that are tough

to understand, clerkly, nor with cunning write.

Blot it with your tears a bit you might:

and if you write a goodly word all sweet,

though it be good, do not it oft repeat.

148.

For though the best harper who is alive

were, on the best sounding sweetest harp

there ever was, with all his fingers five,

to touch only one string, on one note harp,

even though all his nails were pointed sharp,

it would make everyone who heard him dull,

to hear his glee, and his strokes full.

149.

Do not mix discordant things together,

as thus, to use the terms a doctor might

in speaking of love: give to your matter

the proper form, always, and make them like:

for if a painter were to paint a pike

with asses feet, and head it like an ape,

there’s no accord, and it is but a jape.

150.

This counsel was pleasing to Troilus,

but as a fearful lover, he said this:

‘Alas, my dear brother Pandarus,

I am ashamed to write, in this,

lest in my innocence I say amiss,

or lest she would not, in despite, receive it.

Then I were dead: and nothing might relieve it.

151.

To that Pandarus answered: It is best

to do as I say, and let me with it go:

for by the Lord that formed both East and West,

I hope to bring an answer to it, so,

in her own hand: and if you say no,

let be, and sad be the man alive

that against your will helps you to thrive.’

152.

Said Troilus: ‘By God then, I assent:

since you wish it, I’ll arise and write:

and God of bliss, I pray, with good intent,

the enterprise, and the letter, both aright,

to speed: and you Minerva, the Bright,

give me the wit the letter to devise’:

and he sat down, and wrote after this wise.

153.

First he began her his true lady to call,

his heart’s life, his desire, his sorrow’s cure,

his bliss, and then those other terms, all

that in such a case these lovers adore:

and in a humble way, as in speech before,

he began to recommend him to her grace:

to tell it all would ask too great a space.

154.

And after this quite humbly her he prayed

to be not angered, though he, in folly, ay,

was so bold as to her to write, and said

love made him do it, or else he must die,

and piteously for mercy began to cry.

And after that he said, and lied aloud

that he was of little worth, and nothing proud:

155.

and that his skill by her should be excused,

being so little, and that he feared her so,

and his unworthiness he then accused:

and after that, he began to tell his woe,

but that was endless, without end, so

he said he would to loyalty always hold:

read it over, and began the letter to fold.

156.

And with his salt tears he began to bathe

the ruby in his signet, which he set

into the wax, as quickly as one may.

With that, a thousand times before he let

it go, he kissed the letter his tears had wet,

and said: ‘Letter, a blissful destiny

waits for you, my lady you will see.’

157.

Then Pandar took the letter, betimes,

and that morrow, to his niece’s palace made a start:

and he swore firmly that it was past nine,

and began to jest, and said: ‘Oh, my heart,

is so fresh, although it feels sore smart,

that I can never sleep in a May morrow,

I have a jolly woe, a lusty sorrow!

158.

Cressid, when she her uncle heard,

with fearful heart, desirous to hear

the cause of his coming, thus answered:

‘Now by your faith, my uncle,’ she said, ‘dear,

what manner of wind now blows you here?

Tell us your jolly woe and your penance,

how far you are placed within love’s dance.’

159.

‘By God,’ he said, ‘I always hop behind.’

And she laughed out loud, fit to burst.

Said Pandarus; ‘Yes, always look to find

a joke with me, but listen to me first:

there is right now come into town a guest,

a Greek spy, who tells us some new things,

of which I come to give you the tidings.

160.

Into the garden go, and we shall hear,

all privately, of this, a long sermon.’

With that they went arm in arm, the pair,

into the garden, from the chamber, down.

And when he was far enough that the sound

of what he said no other man might know,

he said this to her, and the letter showed:

161.

‘Lo, he that is all wholly yours and free

recommends himself humbly to your grace,

and sends this letter here to you, through me:

Consider it yourself when you have space,

and set some goodly answer in its place:

or otherwise, God help me, to speak plain,

he may not live much longer in such pain.’

162.

Full of fear she halted and stood still,

and took it not, but her look of humble cheer

began to change, and she said: ‘All you will,

(for love of God) that touches on such a matter

bring it me not: and also uncle dear

have more respect for my position, I pray,

then for his desires. What more can I say?

163.

And consider now if this is reasonable,

and do not, out of favour or laxity,

speak an untruth: now is it suitable

to my position, by God and your honesty,

to take it or to show him any pity,

harming myself or earning censure?

Carry it back to him, by God, for sure.’

164.

At this, Pandarus began, at her, to stare,

and said: ‘Now this is the greatest wonder

that ever I saw! This is indeed nice fare!

May I be struck dead in the storm’s thunder

if, even for the city that stands yonder,

I would to you a letter bring, or one take

to harm you: why do you of it such issue make?

165.

But so you women do, some or well nigh all,

that he who most desires you to serve,

to him you care least what might befall,

and whether he live or die at your word.

But in return for all that I deserve,

refuse it not,’ he said, and held her just,

and in her bosom the letter down he thrust.

166.

And he said to her: ‘Now cast it away at once,

so that the folk may see and gape at us, ay.’

She said: ‘I can abide till they are gone,’

and began to smile, and said: ‘Uncle, I

pray you yourself will the answer provide,

for truly I will not write a letter, I say.’

‘No? Then I will,’ he said, ‘if you dictate.’

167.

At that she laughed, and said: ‘We will dine,’

And he began to mock himself at last,

and said: ‘Niece, I so greatly pine

for love, that every other day I fast’:

and began his best jests to broadcast,

and made her laugh so, at his folly,

that she for laughing thought she would die.

168.

And when she had come into the hall,

‘Now, uncle,’ she said, ‘we’ll go dine at once’,

And she began on some of her women to call,

and straight away into her chamber was gone.

But of her business there, this was one

among other things, indeed,

quite privately the letter to read.

169.

She studied it word by word, in every line,

and found no fault, she thought it good:

and put it away, and went in to dine.

And Pandar, who in meditation stood,

before he was aware, she caught by the hood,

and said: ‘You were caught before you knew.’

‘I grant it, ‘ he said, ‘what you wish to, do.’

170.

Then they washed, and sat down to eat:

and after noon quite slily Pandarus

began to draw near the window on the street,

and said: ‘Niece, who has adorned thus

yonder house that stands opposite us?’

‘Which house?’ she said, looking to behold,

and knew it well, and whose it was him told:

171.

And they fell into discussion of some detail,

and sat in the window, and there they stay.

When Pandarus saw a chance to tell his tale

and clearly saw her folk were all away,

‘Now, my niece, tell on,’ he said, ‘I say,

how do you like the letter you read, though?

Can he write? For, in truth, I do not know.’

172.

At that all rosy-hued starting to blush, she

began to hum, and said: ‘Well, I think so.’

‘Repay him well, for God’s love,’ said he:

‘For my reward, I will the letter fold,’

and held his hands up, and knelt down low,

‘Now, good niece, be it never so slight,

give me the labour of sealing it up tight.’

173.

‘Yes, for I could so write,’ she said though,

‘and yet I don’t know what I to him should say.’

‘No, niece, ‘ said Pandarus, ‘say not so:

but at the least thank him, I pray,

for his good will, don’t let him waste away.

Now for the love of me, my niece dear,

do not refuse to listen now to my prayer.

174.

‘By heaven!’ she said, ‘God grant that all is well!

God help me so, this is the first letter

that ever I wrote, yes, or any part, so to tell.’

And into her closet to consider it better

she went alone, and began her heart to unfetter

from the prison of disdainfulness a mite,

and sat herself down, and began to write.

175.

To tell of it briefly is my intent,

the substance, as far as I can understand.

She thanked him for all the good he meant

towards her: but take him by the hand

she would not, nor would she be bound

in love, but like a sister, him to please,

she would be glad to set his heart at ease.

176.

She closed it up, and to Pandarus did go,

where he was sitting, gazing at the street:

and she sat down beside him on a stone

of jasper, on a cushion of gold complete,

and said: ‘May God help me in this, so be it,

I never did a thing with greater pain

than write this, to which you me constrain.’

177.

And gave it him. He thanked her and said:

‘God knows, of things reluctantly begun

often the end is good: and, my niece, Cressid,

that you have only with trouble now been won

he should be glad, by God and yonder sun!’

Because men say, impressions which are slight

are always the readiest to take flight.

178.

But you have played the tyrant far too long:

your heart indeed was hard to engrave.

Now cease, and no longer on it hang,

though you wish your aloofness to save.

But make haste that he of you may joy have:

for trust this well, too long a harshness

often indeed breeds scorn from distress.

179.

And just as they spoke of this matter,

lo, Troilus, right at the street’s far end,

came riding in a company of ten,

all quietly, and his course began to tend

to where they sat, as this was his way to wend

towards the palace: and Pandarus him spied,

and said: ‘Niece, see who comes here to ride.

180.

‘O flee not in (he sees us, I suppose),

lest he think that you his sight eschew.’

‘No, no,’ she said, and turned as red as rose.

At that he began her humbly to salute

with fearful face, and often changing hue:

and his look pleasantly up he cast,

and nodded to Pandar, and then rode past.

181.

God knows if he sat his horse aright,

or was fair to see on that day.

God knows if he was like a manly knight.

Why should I stop to tell of his array?

Cressid, who watched him all his way,

to tell in short, she liked, in any case,

his person, his array, his look, his face,

182.

his goodly manner, and his nobleness,

so well that never yet since she was born

had she such pity for his distress:

and however harsh she had seemed before,

I hope to God she now can feel the thorn.

She shall not pull it out this week or next:

God send more thorns like that, is my text.

183.

Pandar, who stood next her closely,

felt the iron was hot and began to strike,

and said: ‘Niece, I pray you earnestly,

answer me what I ask you, as you like:

a woman who brought his death in sight,

without him being guilty, but lacked ruth,

would that be well? Said she, ‘No, in truth.’

184.

‘God help me so,’ he said, ‘you say no:

you feel in yourself I do not lie.

Lo! There he rides.’ Said she: ‘Yes, he does so.’

‘Well,’ said Pandar, ‘as I have told you thrice,

let folly go, and shame, be not too nice,

and speak with him to ease his heart:

Let niceties not make you both to smart.’

185.

But about it there was toil still to be done:

considering everything it might not be:

and why? From shame, and it was too soon

to grant him so great a liberty.

For plainly her intent, so said she,

was to love him in secret if she might

and reward him with nothing but with sight.

186.

But Pandarus thought: ‘It shall not be so

if I can help it, this nice opinion

shall not be held for a year or two.’

Why should I make of this a long sermon?

He must agree to her conclusion

for the while: and when that it was eve,

and all was well, he rose and took his leave.

187.

And on his way homeward quick he sped,

and he felt his heart with joy to dance:

and Troilus he found alone in bed,

who lay, as do these lovers, in a trance,

between hope and desperation’s glance.

But Pandarus, straight at his in-coming,

sang out, as one who says, ‘Look what I bring.’

188.

And said: ‘Who is in his bed so soon

and buried thus?’ ‘It is I, friend,’ said he.

‘Who? Troilus? No, by help of the moon,’

said Pandarus, ‘you shall rise and see

a charm that was sent just now to thee

which can heal you of your distress,

if you now complete the business.’

189.

‘Ah, through the power of God!’ said Troilus

And Pandarus made him the letter take

and said: ‘By heaven, God has helped us:

have here a light, and look on all this black.’

As often the heart joyed or began to quake

of Troilus, when he opened it and read,

as the words gave him hope or dread.

190.

But finally he took all for the best

that she had written, for something he beheld

on which, he thought, his heart might rest,

though she hid the words beneath a shield.

So to the more worthy part he held,

so that in hope and at Pandarus’s request,

his great woe he abandoned at the least.

191.

But as we may ourselves any day see,

the more the wood or coal, the more the fire,

just so increase of hope, from wherever it be,

full often with it increases the desire:

just as an oak comes from a little spire,

so through this letter, which she sent,

the desire increased, with which he burnt.

192.

Wherefore, I say, always, day and night,

out of this, Troilus began to desire more

than he did before, from hope, and with might

pressed on, helped by Pandar’s lore,

and wrote to her of his sorrows sore:

from day to day he let not things grow cold,

and by Pandar wrote of something or had it told.

193.

And also did other observances

that belong to lovers in this case:

and after that as the dice chances

so was he either glad or said: ‘Alas!’

and from the luck of the throw set the pace:

and according to such answers as he had,

so were his days either sorry or glad.

194.

But to Pandar always he had recourse,

and began to turn piteously to him to complain,

and sought advice of him, and help of course:

and Pandarus, who saw his bitter pain,

grew well nigh dead for pity, truth to say,

and busily with all his heart he cast

around to ease his woe, and that right fast.

195.

And said: ‘Lord and friend and master dear,

God knows your dis-ease give me woe,

but if you will only cease this woeful cheer,

by my truth, before two days shall go,

and with God’s help, I will shape things so

that you will come into a certain place

where you yourself may ask for her grace.

196.

And certainly, I know not if you know’st,

but those who are expert in love this say,

that it is one of the things that furthers most,

for a man to have a chance to pray

for grace, and in a proper place, if he may:

for on a good heart pity it will impress,

to hear and see the guiltless in distress.

197.

Perhaps you think: “Though it might be so

that nature would cause her to begin

to have some manner of pity on my woe,

disdain says: ‘No, me you will never win.’

Her heart’s spirit so rules her within

that though she bends yet she stands rooted:

how is this to my advantage suited?”

198.

Think, in answer, when the sturdy oak

that men hack at often, one by one,

has received the final felling stroke,

swaying greatly it comes down at once,

as do these rocks or these millstones.

For falling more swiftly comes a thing of weight,

when it descends, than does a thing that’s light.

199.

And the reed that bows down at every blast,

so easily, when the wind ceases will arise:

but so will not an oak when it is cast:

it does not need me to give you more advice.

Men will rejoice in a great enterprise

well done, that stands firm, without a doubt,

though they have been the longer there about.

200.

But, Troilus, yet tell me with the rest,

a thing that now I will ask of thee:

which of your brothers do you love the best,

as in your very heart’s privacy’

‘It is my brother Deiphebus,’ said he.

‘Now,’ said Pandarus, ‘before hours twice twelve

he shall ease your woe, yet know it not himself.

201.

Now let me alone to work as I may,’

he said, and went then to Deiphebus,

who had his lord and great friend been always:

no man he loves so much but Troilus.

In short, to tell, without more to discuss,

Pandarus said: ‘I pray you that you might be

friend to a cause which touches me.’

202.

‘Yes, by heaven,’ said Deiphebus, ‘well you know,

in all that ever I may, and God before,

for no man more, except him I love most

my brother Troilus, But say what for

and how it is: for since I was born

I have not, nor never will be, against anything,

I think, that might you to good fortune bring.’

203.

Pandar began to thank him, and to him said:

‘Lo, sire, I have a lady in this town,

that is my niece and is called Cressid,

whom men would cause to suffer oppression,

and would wrongfully have her possessions.

Wherefore of your lordship I beseech

to be our friend, without further speech.’

204.

Deiphebus answered: ‘Oh, is not this

whom you speak of as if she were a stranger,

Cressid, my friend?’ He said: ‘It is.’

‘Then you need, ‘said Deiphebus, no more

speech: for, trust well, I will be to her

her champion with whip and with spur:

I care not if all her enemies heard.

205.

But tell me, you who know all this matter,

how I might best assist: let me now see.’

Said Pandarus: ‘If you my lord so dear,

are ready now to do this honour for me,

to beg her tomorrow, lo, that she

should come to you and her complaints cite,

her adversaries would at that take fright.

206.

And if I might pray further even now,

and require you to undergo such travail

as to have your brothers here with you,

that might her cause better avail,

then I know well, she might never fail

to be helped, either at your instance,

or with her other friends’ governance.’

207.

Deiphebus, who was of that kind

that to all honour generously consent,

answered: ‘It shall be done, and I can find

yet more help to add to my intent,

what would you say if I for Helen sent

to speak of this? I think that for the best,

for she can lead Paris at the least.

208.

For Hector, that is my lord, my brother,

there is no need to pray him friend to be:

For I have heard him at one time or another,

speak such honour of Cressida that he

can speak no higher, such virtue to him has she.

There is no need his help to crave:

he’ll be as true as we’d have him behave.

209.

You yourself also speak to Troilus

on my behalf, and ask him with us to dine.’

‘Sire, all this shall be done,’ said Pandarus,

and took his leave, and wasted no time,

but to his niece’s house in a straight line

he came, and found her ready from the meat to rise:

and sat him down, and spoke to her in this wise.

210.

He said: ‘O the true God, how I have run!

Lo, my niece, do you not see how I sweat?

I don’t know if to your thanks you’ll add one.

Are you aware how that false Polyphete

is now about to lodge an appeal,

and bring on you advocacies new?’

‘I? No,’ she said, and her face changed hue.

211.

‘What is he trying now, to trouble me

and do me wrong? What shall I do, alas?

Yet, of himself, to me it would no care be

were it not for Antenor and Aeneas,

that are his friends in such a case:

but for the love of God, my uncle dear,

it matters not: let him take all, I fear:

212.

without it I still have enough for us’

‘No,’ said Pandar, ‘it shall not be so:

for I have been just now to Deiphebus

and Hector, and my other lords, though,

and quickly made each of them his foe,

so that, through my care, he shall never win

for aught he can do, when he begin.’

213.

And as they thought what should best be done,

Deiphebus, out of his own courtesy,

came to ask her, in his own person,

to keep him, on the morrow, company

at dinner, and she must not him deny,

and readily she said she would obey.

He thanked her, and went upon his way.

214.

When this was done, Pandar rose alone,

to tell this briefly, and began to wend

his way to Troilus, who was still as stone,

and all this thing he told him, end to end,

and how he used Deiphebus as a friend:

and said to him: ‘Now is the time if you can

bear yourself well tomorrow, and all is won.

215.

Now speak, now beg, now piteously complain:

waver not through shame or fear or sloth.

Sometimes a man must tell of his own pain:

believe it, and she will show towards you ruth:

you will be saved by your own faith, in truth.

But well I know you are now in fear,

and what it is, I bet you, is right clear.

216.

You think now, “How am I to do this?

For by my face folk must espy

that it is for her love I fare amiss:

yet I had rather unknown for sorrow die.”

Now think not so, for you do folly, I

right now have found out a manner

of trick to cover your situation here.

217.

You shall go overnight, and that so blithe,

to Deiphebus’s house, as if to play,

your malady the better away to drive,

because you seem sick, truth to say.

Soon after that, down in the bed you lay,

and say you can no more being up endure,

and lie right there, and await your adventure.

218.

Say that the fever is used in you to take

the same time, and lasts until the morrow:

and let’s see how much out of it you can make,

for, by heaven, he is sick that is in sorrow,

Go now, farewell: and Venus’s aid we borrow,

I hope, and if you hold this purpose firm,

your favour she shall fully there confirm.’

219.

Said Troilus: ‘Alas, you needlessly

counsel me that sickness I should feign,

since I am sick in earnest, as you see,

so that I well nigh die of the pain.’

Said Pandarus: ‘You will the better complain,

and have the less need to counterfeit,

for men think he is hot that they see sweat.

220.

Lo, keep you, at close station, and I

shall the deer well towards your bow drive.’

With that he took his leave all softly.

And Troilus to the palace went so blithe.

He was never so glad to be alive.

And to Pandarus’s advice gave all consent.

And to Deiphebus’s house at night he went.

221.

What need have I to tell you all the cheer

that Deiphebus for his brother made,

or his fever, or his sickly manner,

how men had him with sheets arrayed,

when he was abed, and how they wished him glad?

But all for nothing, he stuck as was wise

to the plan he had heard Pandarus devise.

222.

But certain it is, before Troilus was abed,

Deiphebus had begged him overnight

to be a friend, in helping of Cressid.

God knows he granted that all right

to be her full friend with all his might.

But there was as much need to have done

that, as to bid a madman run.

223.

The morning came, and it grew near the time

to eat, when the fair queen Helen

prepared to visit, an hour after prime,

with Deiphebus, to whom she did not feign:

but as his sister, familiarly, truth to tell, then,

she came to dinner, pure in intent,

Only God and Pandar knew what all this meant.

224.

Came Cressid also (all innocent of this)

Antigone, her sister Tharbe also:

but to flee from prolixity best is,

for love of God, and let us quickly go

right to the matter, without tales, so,

as to why these folks assembled in this place,

and let us pass over their greetings apace.

225.

Great honour did Deiphobus do them for certain,

and fed them well with all that might delight.

But evermore ‘Alas!’ was his refrain,

‘My good brother Troilus, does lie

still sick’. And with that he began to sigh:

and after that he tried to make them glad

as far as he might, and with what cheer he had.

226.

Complained also Helen of his sickness

so faithfully, that it was pitiful to hear,

and everyone began for feverishness

to be a doctor, and said: ‘In this manner

men cure folk: by this charm I will swear.’

But there sat one, though she did not choose to teach,

who thought: ‘I could yet be his best leech.’

227.

After that complaint, they began to praise

as folk do still when someone has begun

to praise a man, and up with praise him raise

a thousand-fold yet higher than the sun:

‘He is, he does, what few lords are and can.’

And Pandarus, whatever they might affirm

did not forget their praising to confirm.

228.

Cressid heard all this thing well enough,

and every word began to note, with pride,

though sober-faced her heart began to laugh:

for who is there would not be glorified

to govern if such a knight lived or died?

But I pass by this, lest you too long dwell: