Storming Heaven

A. S. Kline

II - Essex

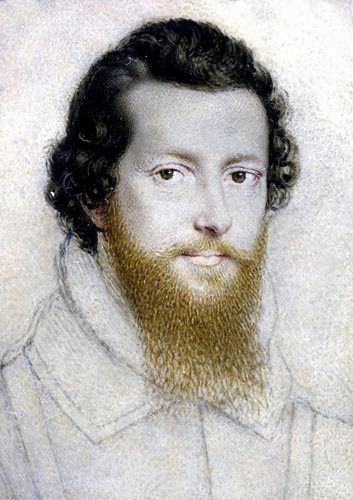

‘Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex’

Isaac Oliver, ca. 1565–1617, French

The Yale Center for British Art

Pride is a high opinion of one’s own abilities, arrogance in attitude or conduct, awareness of exalted position, a sense of what is appropriate to that position. To aspire is to desire seriously, to climb towards, to yearn, to covet. As Robert Devereux, Second Earl of Essex went to the block shortly after sunrise on a February morning in 1601, Mars, the soldier’s planet, guardian of his life’s energies, of his passions, was conjunct the Sun in the watery sign of Pisces. Icarus had fallen into the sun, into the sea, his waxen wings melted and destroyed. That same Mars was burning brightly in Leo at his birth. Leo the sign of a man fixed in his opinions, intolerant, power-hungry, but also generous, enthusiastic, with a sense of the dramatic, the theatrical. In an age of theatre his life was lived on stage. Dying at thirty-three he was young enough to be an Icarus, not falling unnoticed but mourned, in spite of the aged Queen, by his public. ‘The difficulty my good lord is to conquer yourself’. Lord Keeper Egerton offers his placatory advice. Icarus in flight gives an unequivocal reply. ‘What! Cannot Princes err? Cannot subjects receive wrong? Is an earthly power or authority infinite? I can never subscribe to these principles.’

Or is he Phaethon who rode the chariot of the sun and scorched the earth? Zeus killed him with a thunderbolt so that he fell into the water, a royal prince sacrificed in ritual to ensure the safe continuance of kingship. Both analogies have power. ‘I was ever sorry that your lordship should fly with waxen wings, doubting Icarus’ fortune’ says Francis Bacon. A subtle analogy. Icarus flies with wings made for him by his father Daedalus not with his own wings. Icarus flies too near the sun, and fails, not because of pride, but because of inability to follow instructions, to control his flight. Yet there is sympathy with Icarus, he is innocent. The situation is not of his making, but is forced on him. In the end his journey is beyond his abilities, and he falls foul of circumstance. Francis Bacon, once faithful supporter, becomes an agent of prosecution, seeing which way the wind blows, choosing a new course to steer, aligning himself with power. Clever but not loyal. Wise but not generous. He too would eventually discover what it was like to fall into the depths.

Pride and aspiration. The Tower is where he dies, where Raleigh dies. Bran’s castle, the White Hill, the place of the magical severed head. ‘Take my head,’ Bran said, ‘and carry it to the White Hill in London’ in an early version of the Grail Legend which is embedded in the Mabinogion. Both are sacrificed to ensure the continuance of kingship, which is the obverse of the real or assumed threat to that kingship. Elizabeth and James are terrified of the challenge to their power, a power, arbitrary, hereditary: terrified of the challenge to order. Order is divine order in their minds. It is artificial order in the mind of a Marlowe, the order held by a Tamburlaine, the Scythian shepherd risen to be God’s scourge, teetering always on the brink of chaos. No wonder Elizabeth was fearful. The pent-up discontent that leads to the Civil War is already a pressure building under the surface of her society. Shakespeare, sharing in that fear, political conformist, holds back that pressure only by verbal magic in his imaginary kingdoms.

Phaethon was a bad driver. His sun-chariot first flew too high so that the earth was chilled, then too low till the world was in flames. Ovid says that he had asked for the reins of his Father Helios’s chariot for one day, to be allowed, for one day, to control and drive the wing-footed horses. ‘It is unsuited to your strength or to your years. You are mortal, and aim at something not granted even to the gods. A firm guiding hand is necessary.’ Phaethon the rebel, attempting what is beyond his powers. Inexperience, arrogance, foolishness, inability. That is Elizabeth’s view. The middle way is safest. Shakespeare’s view. ‘He had not the skill to handle what had been entrusted to him’ says Ovid ‘He was filled with indecision, neither able to let go of the reins, nor strong enough to keep hold of them.’ Phaethon was flung headlong and fell through the air, leaving a meteor trail behind. Ovid describes the subsequent mourning. And England mourned its Phaethon. ‘Sweet England’s pride is gone’. Elizabeth also mourned.

Icarus was only a sweet lad who died of the mistake made by his father Daedalus in creating a course of action which set Icarus up for disaster, which demanded an impossible adherence to his own flight. ‘Follow me closely, do not set your own course.’ As they flew the shepherds and the ploughmen gazing upwards mistook them for gods. But when Daedalus looked back, there was no Icarus, only a scattering of feathers on the surface of the sea.

Phaethon wished to show his sisters what he could be and do. Penelope Devereux, one of Essex’s sisters, was Sidney’s Stella, whose hundred and eight sonnets of Astrophil the star-lover, to Stella, the star, signified the hundred and eight suitors of Penelope in the Odyssey. Phaethon was too weak to control the fierce white horses. He veered to extremes, before, like Milton’s Mulciber, ‘he fell from heaven...sheer oe’r the crystal battlements...dropt from the Zenith like a falling star’. Mulciber, the Son of Morning, full of that pride which challenged the deity. Ovid says that Phaethon’s sisters mourned for him so much they were transformed to trees whose branches shed drops of blood which hardened into amber.

Mars is moving with the Sun, conjunct it on the eighth of February when his foolish rising comes to nothing, the looked-for popular support non-existent in the empty streets near the Strand, and still conjunct it on the twenty-fifth when he goes to his death. Mars rises with the sun on his dark day, the executioner needing three blows to achieve the ritual murder, the sacrifice.

Aspiration is also a breathing-in. His birth was in the early November of 1567, and his astrological chart therefore shows the sun in Scorpio. Astrology is theatre, just as the Elizabethan period was theatre. The Elizabethan attitude to it was, like ours, highly ambivalent, suspecting that it had no substance but intrigued by its symbolism. Astrology is merely chance pattern but even a random play of images can illuminate, and we can use it in that way for its ability to highlight aspects of personality. What fits is useful. What does not fit is discarded. It is in no way a predictive mechanism. Not science but art.

The Elizabethans themselves frequently use the analogy of theatre for their age. It was how it seemed to them, and how it seems to us. Dramatic, often violent, prone to passions, to extremes of anger, envy, jealousy, and pride. Tragic. Gruesomely comic. Sweetly pastoral. Filled with the silvery romance of the Renaissance, translated through France from Italy, to the green countryside of England. There are sharp defining lines. Though we cannot enter into these people, though they remain opaque, defined more by what they fail to say, than the words they do say and write, they are brilliantly coloured. Hilliard and Oliver limn them in jewelled ovals. They themselves drip jewellery and exhibit costume.

Essex is quintessential aspiration. The Sun and Mercury combust together at his birth. Jupiter is conjunct both. Expansive, ambitious, stubborn, conceited, fortunate enough to win a Queen’s favour. A volatile mind. Pluto the ruler of Scorpio is unaspected, a loose cannon of fate. His destruction will come from within, from his own unconscious urges and impulses. Uranus, Neptune and Saturn sit in a tense t-square. There is no need to believe in astrology as any more than theatre, in order to see the depressions, moodiness, strain and tension of Saturn square to Uranus, the self-will, paranoia, involvement with large impractical projects of Neptune square Saturn, or the emotional intensity of Uranus opposing Neptune. These three planets activate the signs of Virgo, the Queen, Sagittarius the archer firing at the stars, and Pisces where the sun will lie on the morning of his death.

Theatre. ‘What is our life? a play of passion’ says Raleigh, ‘our mirth the music of division, our mothers’ wombs the tiring houses be, where we are dressed for this short comedy. Heaven the judicious sharp spectator is, that sits and marks still who doth act amiss. Our graves that hide us from the searching sun, are like drawn curtains when the play is done. Thus march we playing to our latest rest, only we die in earnest, that’s no jest’.

Theatre. One of the keys by which we learn to understand the Elizabethan court and city. A drama played with intensity for effect. Under it the terrible and terrific tensions of religion, the desire for money and wealth, the transience of existence, the vagaries of fortune, the explosion of geographic discovery, the spread of knowledge, the recognition through the Renaissance and its rediscovery of Rome, of Man, the measure of all things. The theatre is lifted to a new level by Marlowe, at the same time as the greater Elizabethan theatre is embroiled in its own drama.

Essex arrives at court in 1584, aged sixteen. Elizabeth is fifty-one. Raleigh favourite for two years by now is thirty-two. For neither man is Elizabeth a young goddess newly arrived at power. She has been queen since 1559, for twenty-five years. We are easily deceived by imagery and symbolism, and brought to earth by calendar dates and realities. Was it all flattery then, flattery aimed at power? Flattery of an older woman to gain a material end?

‘No cause but a great action of your own may draw me out of your sight’ Essex writes to her later, ‘ for the two windows of your...chamber shall be the poles of my sphere’. Raleigh writes his Last Book of the Ocean to Scinthia, the moon-goddess, the Faerie Queen, ‘She is gone, She is lost, she is found, she is ever fair! ‘A Queen she was to me’, ‘Such force her angellike appearance had, to master distance, time, or cruelty, such art to grieve, and after to make glad, such fear in love, such love in majesty’. Mere words, or was there a reality of emotion and affection, even a self-delusion, a fanciful transposition of desire and sexual energy? What, in these men, translated and transmuted itself into their attitude to the woman, made her the Virgin Queen, the incarnation of Diana the huntress? True, it was an age of obsequious flattery, those endless dedications, Shakespeare’s among them, which make us squirm as the greater bows to the lesser, an inordinate respect for institutionalised authority and power, for the links in the chain, for level and order. No sign of that in Marlowe though. No obsequiousness there.

The young Essex stays at Court a while, and then goes on the Low Countries expedition of 1585, where Philip Sidney dies, after being wounded at Zutphen, and England loses its courtier-poet. He leaves his sword ‘to beloved and much honoured Lord, the Earl of Essex’. He also leaves his mantle of the romantic knight, the perfect gentleman, the Petrarchean poet (his equivalent of Petrarch’s beloved Laura is Penelope, Essex’s sister) which Essex cannot fill, and a young wife Frances Walsingham whom Essex later marries. He steadily becomes Elizabeth’s favourite, gradually displacing Raleigh, though she rarely trusts him when he is out of sight, and starves him of resources, playing a cat and mouse game, jealous of her power.

Essex builds a military and political career, bringing round him a group of able men, among them Francis and Anthony Bacon (Burleigh’s nephews, sons of Nicholas Bacon, Elizabeth’s first Lord Keeper of the Great Seal), and Henry Wotton. He forges private connections in Europe. Anthony Bacon’s nest of secret agents will draw in Christopher Marlowe to his service. Sir Henry Wotton is a friend of John Donne. Essex is seen as material for greatness. Or as a route to power. He finds difficulty in handling the Queen diplomatically. Power is too attractive to him. He is not like Raleigh a well-born but untitled man, risen to greatness through rare talents and abilities. He is aristocracy, inherited title. His talents are an adjunct to his greatness.

Essex is ‘a great resenter’. Or is it merely the transparency of his emotions, which he hides with more difficulty than other men? ‘He can conceal nothing, he carries his love and hatred on his forehead’. Never believing that he has what he deserves, is he that Achilles, vain, spoilt, argumentative, a complainer, petulant, the Achilles that Shakespeare paints in Troilus and Cressida ‘full of his airy fame’ and ‘dainty of his worth’? Or is he that Achilles, brave, generous in friendship, doomed to a short life, cheated by Agamemnon the King, ‘eating his heart out by his fast ships, nursing his anger’?

Achilles like Essex is defined and limited by that anger, the root of the Iliad. Both men have that same opaqueness, that definition by their actions, by their destinies. Either we invent motivations for them that are overly complex, or we underestimate the intricacy of their lives. We are either too simplistic or too subtle. They remain in the mind as semi-mythological icons. Both are the symbols of rebellion, passive in Achilles case, active eventually in that of Essex. Both are frustrated, ambitious of glory, free energies that need direction. Both are silent even when they seem to speak, since what they say is only what we expect them to say. Both have a doom-laden fate hovering over them, which they run to meet sword in hand. Both hate the idea of a long, inglorious life.

One imagines Essex, like Achilles, a tall figure striding helplessly through the Underworld; one who would rather be a live dog than a dead lion. Like Achilles, Essex sulks, but also like Achilles his blind courage is indisputable. Though military genius is sadly nowhere in evidence Essex is never cowardly in physical combat. He is the last great aristocrat fighting for the crown, at the same time fighting for himself and his country. He is part of an Old World of amateurs, gifted amateurs, with immense charisma, brilliant style, open-handed, attractive, loyal. No one ever accuses Essex of disloyalty until the final period, and then it is a disloyalty, in his eyes, to a hollow crown.

Like Raleigh he finds himself, in the end, opposed by the administrators, the lawyers, the bureaucrats, the servants, the ones who have arrived by professionalism, by intellect, by skill, by craft. Like Achilles one doubts his competence as a general, it is all amateurishness, but one has sympathy with him. There is always a suspicion that the unlovable Elizabeth, as the unlovable Agammenon (both adepts at sacrifice to gain favourable winds) set up situations and then disown them; cripple their heroes and then accuse them; show anger instead of placating. The heroes' complaints are tedious. They whine. But perhaps there is substance behind their complaints, some injustice. Spoilt favourites they are nevertheless full of promise. Yet with a weakness, a vulnerability in themselves which allows their ultimate destruction.

So Achilles dies again and again, shining out. The tall figure sword in hand, who gathers about him an undiminishable brightness, not justified perhaps by his actions, destroyed at last by the coward who had stolen Helen, but unassailable in his own wrong-headed magnificence, clothed in his own exaggerated idea of fame, of heroism, of self, of passion. ‘And so the famous Achilles was defeated’ says Ovid, ‘If he had to die by a woman’s hand, he would rather have fallen beneath the axe of an Amazon Queen’.

Anthony Bacon created for Essex a secret service to rival that of Burleigh, Anthony’s uncle, who in turn had inherited that built by Sir Francis Walsingham, father of Essex’s wife. Anthony had lived abroad. He had been befriended by Henry of Navarre, who became Henry IV of France, the ‘vert galant’. He had been arrested for sodomy at Montauban, but escaped death through Henry’s intervention. He had known Montaigne whose essays inspired his brother Francis to create the form in English. Suffering from chronic gout he had returned to England, after twelve years, in 1592. Living in his half-brother Edward’s house (leased from the Queen until 1595), Twickenham Lodge, he worked for Essex, gathering information, employing the dubious agents of Elizabethan London to investigate Catholics, atheists, plotters, enemies of the Essex faction and the Crown.

Twickenham Lodge was pleasantly sited on the Thames opposite Richmond Palace. There was a garden, embellished by Francis, and a great park. Later Essex had it in his gift and granted it to Francis in 1594 as a consolation prize for failing to advance him with the Queen. He took it back in 1601 when Bacon switched allegiance. Twickenham Park is the ‘Ferie Meade’ eighty-seven acres of park and meadow, orchard and wood, alongside the river. At Twickenham Francis Bacon entertains a group of young men from the lawcourts who make verses. A poem of John Donne’s survives alongside ones by Bacon and Henry Wotton that are part of a poetic debate on the merits of life in the country, City, and Court. Later Donne’s poem Twickenham Garden is set among the spring breezes there, as he struggles with ‘the spider, love’ and the sighs and tears at York House.

Anthony’s web extends out to the twilight world of Frizer, Poley and Skeres, the men who are at Deptford with Kit Marlowe when he dies, stabbed in the eye. Donne, in the light, Marlowe, in the shadows, touch on the Essex circle. Anthony himself dies in May 1601 a few months after Essex, at the age of forty-three.

The Moon has a dark side, which Essex comes to know, as does Raleigh. Elizabeth is not an emotionally attractive figure. A true daughter of Henry and Anne Boleyn. Once having learnt how to grasp and hang on to power she was cautious, indecisive when it served her purposes, mean, a user-up of men and their talents, a woman who traded brilliantly on the power of the female mythology. Sinthia is demanding and mentally cruel. She exhausts her servants. She throws them away when they no longer serve her purpose. Like Artemis, the huntress, she deserts them at the end, since Artemis cannot ‘corrupt her eyes with a mortal’s death throes’ as Euripides says.

It is the myth of Actaeon and Artemis that comes to mind when one reads of the mad ride Essex made from Ireland in September 1599 after his disastrous campaign there (outsmarted by Tyrone), between Monday the twenty-fourth and Friday the twenty-eighth. Crossing from Ireland with a few companions, then riding non-stop through Wales, the Vale of Evesham, the Cotswolds and Chilterns, he reached the Lambeth Ferry, commandeered a change of horses, finally rode the ten miles or so to Nonesuch Palace where the Queen was staying, through the muddied autumn lanes. Rushing in on her ‘she being not ready, and he so full of dirt and mire that his very face was full of it’. He was punished for that exposure of the Goddess, like Actaeon who caught Diana bathing naked, breaking the taboo, and earning a sacrificial death. Essex catches Elizabeth without her make-up, her artifice, sees the naked power instead invested in the ugly old woman, ‘crooked as her carcass’ in his own words.

When Tiresias saw her bathing Athene blinded him. Actaeon is turned into a stag at bay by Diana, and is brought down by his own hounds, an image Francis Bacon might have appreciated. ‘Falling to his knees, as if in prayer’ Ovid says ‘he moved his head about in silence, stretching out his arms in supplication.’ Essex before the Council. Essex at the block. As Actaeon, so Pentheus stumbling across the Maenads’ mysteries, pulled down by the Bacchae. ‘Now he was panic-stricken, now he was less violent; he cursed himself and confessed his fault.’ ‘Help me, let the ghost of Actaeon move you to pity me!’ Agave tore the head from his shoulders in blind response, calling out ‘See this victory, my own achievement.’ ‘Quickly’ says Ovid ‘as a tree is stripped by the autumn wind, after a deep frost, so those terrible hands tore him apart’.

Sacrifice is a purification and a re-dedication. Sacrifice expels the guilty one, and by the ritual of his death brings him back to his society. What cannot be assimilated, used, digested, has to be expelled and rejected. When the veil is removed, then there is no way back to innocence or artifice. The court of law can also appear like a gang, a band of accomplices designed to destroy. The guilty and the innocent come together and the mantle of each falls over the other. ‘Her choler did outrun all reason’ said Roland Whyte. His fate was still Phaethon’s, that of a man who tried.

Michael Drayton in verses published in 1603 whose subject is Edward the Second’s Queen, Isabella, and her lover Roger Mortimer, First Earl of March, used poetry to make reference to the recently executed Essex. He affirmed an attitude to Essex, prevalent at the time, that to aspire and to attempt, to fulfil one’s ambition even if it meant death, was still a kind of glory, a storming of the sunlit heavens. And he used a historical analogy with the aspirations of the rebellious Mortimer to do so. He and Isabella are studying a painting of the Greek myth that is Essex’s analogue. ‘Looking upon proud Phaethon wrapped in fire, the gentle Queen did much bewail his fall; but Mortimer commended his desire to lose one poor life or to govern all: What though (quoth he) he madly did aspire and his great mind made him proud Fortune’s thrall? Yet in despite, when she her worst had done, he perished in the chariot of the Sun.’

According to Ovid it was the Italian nymphs who buried Phaethon’s body, inscribing on the rock above his grave: ‘Here Phaethon lies, who the sun’s journey made - dared all, though he by weakness was betrayed.’

Why was he executed? There is something ridiculous about his rebellion. Temporarily imprisoning Egerton and his deputation, Knollys, Popham, Worcester, in Essex House. Wandering through the streets with his few supporters, easily arrested. Was he a real threat to the Crown? Stating clearly at his execution that he thanked God he had never been numbered amongst the friends of Spain, or the Catholics or atheists. Was it necessary, any more than Raleigh’s execution was necessary? Was it a sop to Spain to further potential marriage negotiations?

The idea of order in the universe was strong in Elizabethan thinking, the Medieval idea, challenged but not overturned by the Renaissance or the new science. Shakespeare is full of it, that ideal order animating earthly order. There is a corresponding nervousness at disorder. But the Elizabethans were not appalled by newness. They lapped up new discoveries, new worlds, new words, plants, drugs, new translations from the Latin and Greek, new plays, new commerce. There was a tension between religious order, with the associated beliefs in the Fall and Redemption; and humanism, experiment, ‘essays’, the re-evaluation of the classics and the Roman and Greek past. But that tension between authority and freedom was nothing new. It existed throughout the Medieval period, in the troubadours, in Abelard and Heloise, and then in the Italian Renaissance itself.

The Elizabethan obsession with order seems to issue from the Court rather than from society. It is Elizabeth who is so afraid of trouble, and James after her. A daughter of the usurping Tudor dynasty, risen to power through battle. The daughter of a king who severed England from Rome. A woman invested with the symbols of male kingship. It is fear of the boat of power being rocked that is strongest.

Shakespeare is frenetic in his attempts to bolster the Tudor legitimacy, and cement the idea of natural order around the monarchy, but there is also Marlowe, showing the other side, in Tamburlaine risen from nowhere to be many times king. The tension is acute, but perhaps more so in Elizabeth’s mind, and those with interests vested in her power, than in some others.

Where the Florentine Renaissance was blessed with a certain lightness which Shakespeare’s comedies capture, so Elizabethan England shares also its intensity of conflict between Reason and Passion, Will and Authority, the worship of God and the worship of the Goddess. There is an antagonism between the forces of Chaos and Order, New and Old, which is part of its deep theatre, its tragic vision. Is Essex a sacrifice to the obsession with order, with clean endings, a level playing field? Was he disposed of, as one feels Raleigh was, to make things neater, tidier? It was against the wishes of the people. He was mourned, we remember. ‘Sweet England’s pride is gone’ He had written to Elizabeth that ‘ No cause but a great action of your own may draw me out of your sight.’ ‘When your Majesty thinks that heaven too good for me I will not fall like a star but be consumed like a vapour by the same sun that drew me up to such a height’. ‘Therefore for the honour of your sex show yourself constant in kindness’. She made him, but could not control him? She made him, and betrayed him, threw him away?

As a woman she was denied the heroic gestures of action and discovery, a sovereign who no longer went to war. What was possible for her was the Mind, policy, betrayal. She was an old woman full of fear, fixed ideas, lacking constancy and forgetting past services when it suited her, wilful, recalcitrant. She had authoritarian powers.

Perhaps Raleigh had it right? ‘Undutiful words do often take deeper root than the memory of ill deeds. The late Earl of Essex told the Queen that her conditions were as crooked as her carcass, but it cost him his head, which his insurrection had not cost him, but for that speech’. Actaeon has gone too close, uncovered the nakedness of the Divine power that was monarchy, lifted the veil.

Whitehall had become less significant as a palace, more significant now as a place where clever men, toughened by political infighting and the exercise of power, replaced poetry with administration, the military centre with a judicial and legislative one. Where trade and goods in the holds of ships were more important than mythologies however powerful. The modern world was emerging, and like the genie from the bottle it spelt also the end of monarchy, the end of nobility, the diminishment of theatre. Elizabeth and James buy time, but their age is already passing.

It is Raleigh the parliamentarian (‘I think the best course is to set at liberty and leave every man free’) who is the future. It is Essex in a different role, as Privy Councillor in 1593 the year of Marlowe’s death, ‘carrying himself with honourable gravity and singularly liked of both, in Parliament and Council-table, for his speeches and judgement’ who presages a different England, though not as directly as Raleigh. The Queen may win, but the victory is hollow. The Civil War, the Parliamentary forces are only a few decades away.

He was frustrated with the woman. His military expeditions are under-funded and controlled by her. She gives him rope and then hangs him out to dry. He also is an unlucky, if not an incompetent, commander. There is a kind of desperate charm in his disasters. He is as unlucky as Actaeon, or Pentheus. Francis Bacon tells him he is presenting the wrong image, unruly, appealing directly to the affections of the people, a soldier not a courtier. It is ‘a dangerous image’. He should dissemble more, play the game, play the Courtier, bow the head more, stop arguing with her.

Then he is underfunded, because England is underfunded. Four years of poor summers and disastrous harvests, 1594 to 1597; an increasing population; inflation due to the injection of gold and other metals into the economy; the poor state of the cloth trade; and the costly wars. Were the people in the 1590’s bored with the myth, with their Virgin Queen, with Tudor repression? There is a new scepticism at the end of the century, the power of the Commons is rising, ‘the new Philosophie’, according to Donne, ‘calls all in doubt’. Machiavelli is taken more seriously, religion is bound up with freedom of thought, Copernicus is becoming understood, the known world is expanding.

Elizabeth seems increasingly mean-spirited, indecisive, ungrateful. Still, Essex is accident-prone. The expedition to Cadiz in 1596 is militarily effective. Raleigh is there. So is the young John Donne, a gentleman adventurer. But the Spanish merchant ships are set on fire and gutted. There is little plunder. Elizabeth is furious. In 1597 the Islands Voyage to the Azores is dogged by bad weather. Donne is there again, writing poems about the storms and calms. Raleigh upstages Essex at Fayal, and the old rivals fall out again. Still Raleigh, generous as ever towards Essex, writes to Cecil. ‘God having turned the heavens with fury against us, a matter beyond the power or wit of man to resist’. The Spanish treasure ship is missed at Terceira. No money. Elizabeth is furious.

Bad luck, some of it self made, dogs him. Is it the man or his stars, fate or will? The French Ambassador says in 1598 ‘he is a man who in nowise contents himself with a petty fortune, and aspires to greatness’. Roland Whyte in 1597 reports that ‘Her Majesty as I heard resolved to break him of his will, and to pull down his great heart, who found it a thing impossible, and says he holds it from the mother’s side.’

When two myths collide there is a conflict. It throws up strangeness, rawness, incompatibility. It throws up a Leonardo Da Vinci, where the Christian mystery and the natural reality blend curiously together, or a Christopher Marlowe merging in himself Latin culture, Medieval Christianity, and Renaissance thought. Elizabethan England comes late to the Renaissance, is rushed upon it, as though time has been compressed. Individual man, no longer a stone in the Gothic Cathedral of the Middle Ages, no longer a degree in the tuned order of the Deity, but something unique and self-determining, struggles caught between massive forces. On the one hand an inherited and supposedly inviolable order, a ladder of being with its path to salvation through worship of one who ‘died for the world’, so as to redeem man from the sin of the Fall. On the other a new universe of emerging science, geographic discovery, questioning rationalism, observation and achievement.

As in the modern world the attempt is made to fit new thought to old by expanding the terms of religion, but the result is unsatisfactory, unappealing. The physical world seems to deny the short biblical time span, there are self-contradictions in theology, free will does not seem to accord with an all-powerful deity. The very rationalism that the Tudors admire in their administrators, the conquest of Passion by Mind and Will, of itself undermines the irrational orders of monarchy and church. Marlowe is an extreme, but it is the very individuality of men like Essex and Raleigh, which challenges the state, their curiosity, their wide-ranging interests, their ambitions, their energy. The free powers of the individual mind meet the established order in a condition of challenge, a precursor to the great scientific endeavour where the world becomes explicable in terms of the how rather than the why, and Occams razor dispenses with deity.

At the same time the Protestant world-view suppresses and devalues the Goddess, the ancient mythological powers of Nature, makes the world a mechanism to be wielded rather than a sacred space to be hallowed. Elizabeth takes on herself the mantle of the Virgin, Catholicism’s transformed and weakened Goddess image. Elizabeth transfers, from a religion, which no longer contains it, Nature in its sacred depth, and makes it an aspect of herself. She is to be the Virgin, without child. She is to be the Moon, mistress of the tides. By transference the powers of the Goddess are both secularised and defused. Equally individualism, the Puritan one to one relationship with the deity, must be strictly controlled and brought within a rigid and blander ritualisation.

‘ Do not go too low,’ says Helios to Phaethon ‘nor force your way through the upper atmosphere. Drive too high and you will set heaven on fire, too low and you will scorch the earth. The middle way is safest.’ Conservatism, caution, is the order of the day. But the enormous forces of collision are at work. The momentum of individualism gathering speed since the Middle Ages, re-energised in the Renaissance where, through Plutarch’s Lives and other works, a world of individuals is regained in Greece and Rome. That momentum suddenly absorbed by impact with the Medieval world order, and the Christian myth.

A history created in every moment, meets a history generated long ago in one supra-historical moment. The fluid meets the fixed. And this happens in England in a very short space of time, most intensely in the 1590’s, throwing up individuals who must clash with the order that Monarchy and Church desperately seek to regain and ensure. Shakespeare works away at it in nearly every play, the desire for order, an order that is in doubt.

On the Queen all the power of the nation converges. Exactly as it converges on Agamemnon in the Iliad. Achilles however is the Individual. He is ephemeral, short-lived, naked in his vulnerability, lacking in hereditary authority, not consecrated, not a nexus of power, but unique, and aware. He is unstable, prone to moody silences, capable of introversion, reclusiveness, but he is also expansive, formidable, energetic when roused, fatal. He is a brief flare in the darkness, but one that flawed though it is, sheds a luminescence on the age.

‘The great Achilles whom we knew’. How can Elizabeth not fear these younger men whom she raises up, these shining faces full of grace, talent, wit and energy, whose royalty is within, whose power is only an individual power, but by its nature self-generated and essentially legitimate? An Essex, a Raleigh, challenge her to play as a woman, as an intellect, as a partner, as a friend, as a lover, beyond the rules she sets. Always Elizabeth has to consciously strive to bring them back to the game, to work within the rules, within her laws.

It tires her. She is rested by the Burleighs, the Walsinghams, the Egertons. They are within the circle of her crown. But these others play outside it. Sulk in their tents, challenge her judgements, dislike her conditions. But how the safe men bore her! She likes the risk. Where risk is, the hero is born.

With risk is associated the great prize, the golden flower stolen from the underworld, the beautiful lover claimed, the Grail glimpsed. And with risk comes transience, fleeting joy, ultimate sorrow, a name, and silence. These are men who are attracted to risk, prepared to take great risks, who succeed through taking them, and who finally fail through overestimating the humanity and greatness of their enemies. They fall foul of that banality, that legalistic process, which are judgement but not justice.

The risk taking is another aspect of that collision of myths. Where more than one order exists then there is no safety anywhere. Where the laws are incompatible then we must think for ourselves. It all becomes more difficult, harder to understand. The Goddess becomes the Queen, but the Queen is illegitimate order, where the Goddess, mute and troubled, is legitimate, natural order. The Individual must conform by asserting the power of the impersonal State at the whim of an individual Queen, and while asserting by their very individuality the ultimate defeat of what they assert.

So the speeches before execution where these men ask to be forgiven seem to us a sad falling off, yet declare by contrast the deeper rebellion of their lives. Raleigh’s History of the World in asserting its orthodox religious views seems antiquated, almost medieval. Yet the man himself, the prisoner in the Tower, creates an unforgettable, mythic image, and a symbol of the self-sufficient world to come, the scientist in his laboratory, the artist in his room, the modern individual life, lived for itself, for its richness and its transience.

Devereux’s mother is Lettice Knollys, one of those indomitable Elizabethan women, Bess of Hardwick is another, who live long lives, and challenge the Queen. Usually they survive in a sufficiently distant part of the country, Herefordshire, or Derbyshire. They live well north of the furthest summer progressions of Elizabeth and her entourage, those expensive visits that help preserve the royal wealth to the detriment of her subjects. They live sufficiently far away from Court to offer havens to those in distress (Arabella Stuart for example is sent to Hardwick to the Cavendishes). Lettice marries four times. Her second husband is the Earl of Essex, Robert’s father, who dies in Ireland when Robert is a boy. Her third is the Earl of Leicester, (to Elizabeth’s secret dismay) her fourth Sir Christopher Blount, making this near contemporary of Essex, and faithful follower, his stepfather. Blount is executed for his part in Essex’s insurrection.

Lettice stirs Elizabeth up enough to have her ears boxed and be banished from court, for upstaging Elizabeth. Elizabeth thinks he gets his ‘high heart’ from his mother. Elizabeth’s own heart is high. She never lacks courage. In her it is always the war between bravery and caution, between achieving the crown and risking her mother’s fate. That Anne Boleyn whom Wyatt, adapting a sonnet of Petrarch, wrote of, a woman dangerous to follow after or aspire to. ‘Whoso list to hunt, I know where is a hind...And graven with diamonds with letters plain there is written her fair neck round about: Noli me tangere, for Caesar’s I am, and wild to hold, though I seem tame.’

As Queen, Elizabeth must hold the middle way. Bowed under the weight of the sacred crown, that circle over the head of the monarch that creates an intercourse with glory and power; an Athene denying her body to gods and men, blinding those who like Tiresias see her naked; the Goddess restrains her wildness. She substitutes for it a dalliance with risk-taking young men, with Odysseus, or Achilles. She is ruthless in the end, helping them, sharpening their minds and their actions, empowering their swords, appreciating the quick intelligence, the deft action, the brilliant moment, but when necessary withdrawing her protection, forcing the hero to attend, to be aware of her, to have respect, to recognise her power in the everyday and the banal. ‘I will be here again’ says Essex, ‘and follow on the same course, stirring a discontent in her.’ ‘I was ever sorry that your lordship should fly with waxen wings’ Bacon coolly assesses. Essex remains the symbol of all those promising individuals who outreaching their own capabilities and wisdom fall out of the sky.

Why are they so attractive to us, these people who often seem arrogant, wasteful, vain? Because our minds also aspire? Because they attempted greatness? Because their end completes their beginning, their sin is expiated by their death, the circuit completed not by the winning chariot of the sun, but by the blazing meteor that is their transit over the horizon, their bright fall? Because they stir in us the mythological, the archetypal? Because their lives illuminate a fascinating story? Because they fight clear of regret and remorse, and blame, and cowardice? Because even though they beg for their lives and turn on their followers in extremity, they make a good end? Because they embrace that transience and that nearness to death, that risk in living, which touches us all? Because they are not trivial? They give of their best, and at the last seem cheated. ‘I see the fruits of these kinds of employment.... and call to mind’ says Essex, ‘the words of the wisest man who ever lived....Vanity of Vanities.’

The Elizabethan age remains close to the mythic. The Church replaced the pagan festivals with its own Saint’s days and holy days, but the pagan gods lived on disguised, or mutilated, like worn Gothic statues, the Green Men masked in leaves, carved out of stone. It is Shakespeare who reveals most nakedly the meaning of that loss of sacred Nature, the loss of an ancient respect for what is Female, the loss of the Goddess. His Catholic family background left him sensitive to that image of the sacred mother, still virgin, and of that goddess of the natural world, always silent but the centre of truth. Artemis, whose shrine was at Delos, who is Diana the huntress, hides in Nature, surrounded by her virgin companions, she is the silent heart of the wood, the gleaming of Moon and water. Demeter, the Mother, sees her daughter Persephone, the Maiden, abducted, raped and abused, condemned through that forcing of her innocence to a life on Earth, but also a second twilight life in Hades. Cordelia, likewise, is the Kore, the beloved Delian heart, the ‘coeur de’ Lear, the silence at the centre of the world, the soul of the protagonist.

Elizabeth appreciated the effect of the severance from Rome and thereby from the rituals of the Goddess. They were the ancient rituals of Venus and Adonis, of Attis and Cybele. They were the rituals of the cycle of the natural year, whereby Nature, the Great Goddess, must see her consort the sun destroyed and resurrected, buried and brought to life from the ground, executed and revived, harvested and germinated, dismembered and made whole again. The Church was forced to assimilate the great myth into itself because its own myth was a variant, but a crucial variant, on the theme of the god who dies to save the natural world.

Christianity’s more important messages for the Elizabethans concerned sin and redemption, the fall of humanity and its potential salvation, the advent of divine mercy, pity, peace and love, as valid poles of social as well as private morality. Nevertheless Elizabeth sought continually to take on herself the mantle of the Virgin, the attributes of the goddess. So she is poeticised as Belphoebe, Gloriana, Virginia, Artemis, Cynthia the moon goddess, Astraea the virgin goddess of justice, impartial, wise, severe, but granting affection. Elizabeth was born under Virgo, and associated herself with that constellation, which the Greek myth suggests was formed when Astraea, tired of the crimes of men, climbed to the heavens, to rejoin her father Zeus, the oak god. Astraea punishes crimes, hates disorder, is intolerant of chaotic failure, impatient with mankind.

Raleigh writes of her as the Moon Goddess, endlessly. ‘Praised be Diana’s faire and harmless light’, ‘If Synthia be a Queen, a princess and supreme’, ‘A queen she was to me, no more Belphebe’, ‘A vestal fire that burns, but never wasteth’. She was the Faerie Queen in Spenser’s poem dedicated to Raleigh. For that poem Raleigh wrote his introductory verse, A Vision. ‘Methought I saw the grave where Laura lay’. He refers to the vestal flame, within the temple, Elizabeth outshining Petrarch’s beloved Laura enough to make Petrarch himself weep. Raleigh calls it a vision ‘upon this conceit of the Faery Queen’. Does the conceit display a faith, a belief, a genuine love, or is it merely a Courtier’s tribute, a sophisticated intellectual game? Can poetry and theatre truly help to transfer the veil of the Goddess to the mortal woman? Did Raleigh really love this woman twenty years older than himself, reaching her sixties in the 1590’s when he was in his forties, in his prime? She was thirty-five years older than Essex. An aged Virgin. But power is power, and it was focused on her.

Should we be cynical in that way? Raleigh never is. Essex may well have been. It shows perhaps the difference in age between the two men, the difference in temperament, the difference in background. She made Raleigh, but Essex was already nobility. Essex also wrote poetry about her. Henry Wotton served Essex, before becoming, among other things, ambassador to Venice and ultimately Provost of Eton College under Charles the First. He said of Essex that ‘he liked to evaporate his soul in a sonnet’ as Wotton himself, friend of Donne in his early days, also did. ‘Change thy mind since she doth change’ wrote Essex in his complaining mode.

Raleigh blames himself or fate, but submits to the Goddess. He fails to understand his subsequent fall, but his response is not complaint but lament. Essex prefigures his own future fall in his dissatisfaction, envy and sense of injustice. ‘Life, all joys are gone from thee, others have what thou deservest. Oh! my death doth spring from hence. I must die for her offence.’ Henry Wotton in his verse was more sober, realistic, and penetrating, understanding political risk and self-deception, writing in his lines on the fall of Somerset ‘Dazzled thus with height of place, whilst our hopes our wits beguile, no man marks the narrow space twixt a prison and a smile’.

In Elizabeth the rational mind is always uppermost, that intellect which watches, waits, has learnt caution, demands order, duty, control, is in itself its own power, and wields absolute power over the conscious brain. The psyche, the soul, the woman herself is in some way suppressed. She takes on the role of a man, diverts into anger, tantrums, coquetry the irrational part of her self, the hidden subconscious. She is divorced from her soul. Her answer to any challenge from her soul is to annihilate it. This is the Puritan reflex. The need for order, to legitimise the Tudor dynasty, demands that needs are controlled, that wishes are sublimated. Her femininity is translated into pageantry, the wit of courtiers, pseudo-worship of the divine queen. The myth itself, the greater life, of biology, nature, and instinct, of love and truth, simplicity and beauty, the apolitical life of silence and reverence, is bypassed, short-circuited, defused. The true Goddess is buried.

The Queen is Virgin, but it is not the sweet, sacred virginity of the maiden, rather the chilly virginity of Athene, the power which rules in sterility, demanding obedience but chary of affection. It is for her, a woman taking on the mantle of divine kingship, an absolute necessity to wear this mask. It is imposed by male society. It is a condition of maleness. The mysteries, the private worlds, the internal communions, magic, extremism, heresy, disorder, rebellion, must be viciously suppressed. It is a condition demanded of arbitrary kingship, of hereditary, unmerited power, that its survival, if it is not to be at the whim of the crowd, must be ensured by oppression and tyranny, by ruthless control, by a continually reiterated call to duty and responsibility. Uncivilised nature, passion, the attacks of the body on the mind, of appetite on reason, are inimical to the king.

Since we can only achieve peace by laying down power, then the position of power is always at odds with peace, with our best interests, with the interests of the spirit and the soul. Since the king cannot relinquish command except through self-transformation he must bury deep everything that does not support the kingdom. So the king must search out the perfect servant, the uncomplaining aspect of the soul, the Burleigh, who in a strange sexual reversal is the woman to Elizabeth’s man. This is not to deny Burleigh his masculinity also. Those aspects of femininity which support the crown, its love of ornamentation, its coquetry, its sacred distance, its willingness to serve, its maternal solicitude, its remote chastity, its loyalty and reliability, are acceptable. Those aspects which undermine the crown, passion, appetite, irresponsibility, sexuality, desire for power, ambition, sorcery, promiscuity, generation, violence, heresy, must be destroyed, and punished.

The man, like Essex, or Raleigh who challenges, who displays his capability to bear children, who shows ambition, is ungrateful or petulant, violent or offensive, must be punished, or destroyed. The women who consort with them Frances Walsingham, Elizabeth Throckmorton, Lettice Knollys (who married Elizabeth’s Robin, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester) must be banished from Court as representatives of the irrational alter ego, the vessels of appetite, of nature, of potential threat.

Those who wear the mask of the Goddess, can never be ultimately trusted. In a moment the Goddess can alter from her benign to her malificent aspect, split in two, show her passionate nature, as the emblem of the total earth of which rationality is only a part. She, visible as he or she, is daemonic, other-worldly, an amoral witch, a faithless bride, a forbidden destination for the mind, a hidden soul out of consciousness, a boiling up from the deep psyche of everything true that is also everything to be denied and falsified.

The favourite, the blessed one, for whom affection is shown, on whom gifts are showered, wealth as a substitute for closeness, for sexuality, for love, is also to be feared. The soul may rise in rebellion, ambition may become insurrection, aspiration may become lust, affection may make demands and seek to demonstrate power, love may become treachery. Elizabeth is the masculine kingship, the force of reason, the source of order. In that role she must suppress the Goddess, and she does, as Catholicism, as Mary the rival Queen, as heresy, as sorcery, as deviant ambition. Her tragedy is that nature denied is barren. The Virgin Queen can have no heir. The rational mind alone cannot achieve totality of vision, and reconciliation. Nature and the Goddess conceal the face of Death behind the mask of conception and birth. The aged body is not immortal.

The irony of her denial of the Goddess in the name of rational government, is that the destruction of the myth of the Goddess brings down with it the myth of royalty and kingship. If one is not sacred neither is the other, since it is from hereditary accident that the power derives. The generation of nature is also the generation of kings. In the following centuries the suppressed Goddess will continue to be suppressed, buried below the surface of society, or openly denied. For the Victorians, Woman is sacred, because otherwise she is the Goddess in her demonic form. Therefore she splits in two into the ‘angel in the house’ and the ‘fallen’ woman of the city’s underworld. Men pay homage to both. This is what we call the Victorian hypocrisy. For the true Church similarly woman must be the virgin or the lesser vessel, lest she become Diana of the Ephesians at whose temple women prostituted themselves on behalf of the Goddess.

.

Elizabeth and Essex show the surface of events, the visible motivations, the tensions of politics. Behind them though are the forces and pressures, which may explain their hysteria, their over-reaction to events, the tragic outcome of those events. The transference of the myth to herself, which Elizabeth engineered, reacted viciously on the Stuarts who succeeded her. Paradoxically while it tried to rob the Catholic remnants of the Goddess myth of their power, it identified the Crown with the myth, correctly, and thereby guaranteed Puritan opposition to the monarchy if it failed to act in line with the nation’s aspirations. The one jealous God would not lie down with the Goddess.

James, whom Henry of Navarre called ‘the wisest fool in Christendom’, carried on her work, but without her intellect, her instincts, her balance. Dissenting Mind was now disengaged from the royal myth. It had passed into the social structure where it would fight the Goddess from below rather than above, and into the Church which espoused Jehovah and the myth of sin and redemption, itself not yet understanding the destruction of all myth which was under way. Catholicism had been defeated but at the cost ultimately of kingship. Kingship would be defeated, leaving Religion standing as the last mythical nexus. That awaited the onslaught of science. Through science, democracy, law and commerce, reason triumphed. At the cost of the myths, at the price of ejecting Humanity into the Wasteland.

Who decided that Essex should die on Ash Wednesday? It is the day after Shrove Tuesday and marks the beginning of Lent, the period of repentance and fasting, commemorating Jesus of Nazareth’s forty days solitude in the desert. Appropriate then, as a Christian time to repent one’s sins. Ash Wednesday however is also an ancient festival. The Carnival, the week before Lent, was a time of riot and indulgence celebrated in festivity in Catholic countries (the Latin ‘carnem levare’ means to put away meat). The pre-Christian festival contained rituals that surround the killing of the old representative of the vegetation god in order to convey the spirit to a new incarnation. The divine king is killed in order to quicken the fields and to resurrect the god in a younger and newer form. The original hunting ritual where the slain god was an animal (Actaeon as a deer, Adonis linked to a wild boar) continued in the agricultural world. In Provence an effigy called Caramantran was stoned on Ash Wednesday. In the Ardennes a personification went through mock execution. In Normandy an effigy was rolled down the hill and then set alight, before being thrown through the air into the river, a death by all the elements. In Germany a straw man was formally condemned, beheaded, laid in a coffin, and buried in the churchyard. And so on. The young god, the former king, is deposed and executed in order to guarantee the resurrection of the god at the next turn of the sacred wheel. Why was Essex beheaded on Ash Wednesday?

February-March is the Celtic lunar ash month, the ash tree being the third letter of the tree alphabet, nion, after birch and rowan. Ash Wednesday also coincided with the start of the third zodiacal month, when the sun is in Pisces. It is in Pisces then that the Sun, conjunct Mars, rises on that February morning. Wednesday is Mercury’s day. Mercury, the mind, in Aquarius the sign of change, is troubled, squaring Saturn the planet of constriction and severity in Scorpio Essex’s sun sign. The Sun and Mars, his life’s energies and selfhood, are debilitated, squaring the Moon as she moves into Scorpio, his birth sign. Jupiter is setting conjunct his natal Saturn, signifying the end of good fortune, falling below the horizon in Virgo, Elizabeth’s sign.

At that sunrise Pluto the planet of fate, is alongside Uranus the planet of change. Pluto and Mars are the rulers of Scorpio. On the day of his insurrection, Pluto was conjunct the darkening Moon, while Mars conjunct the Sun was square his natal Sun in Scorpio and opposed by Neptune planet of illusion and self-deception. Essex carries out his insurrection in a failing dream, his fate obscured by the Queen, his energies opposed to his natural energies. He dies with fading fortune, attacked by the Moon, under the sign of altered fate.

We know there is no scientific basis for Astrology. The Elizabethans were taught by their religion that God left human beings with free will, and that Euripides was in error when he said that ‘What is ordained is master of the gods and thee’. The chances of finding significant alignments in any astrological chart are high. Any two planets have better than a one in eight chance of forming a major alignment, that is a conjunction, opposition, sextile, trine or square, with each other, assuming that a tolerance of three degrees is accepted. With sixty-six pairings, from the ten ‘planets’ plus the ascendant and midheaven, to play with, any chart will therefore show up major aspects. In addition the wealth of symbolism associated with planets and signs offers the possibility for endless interpretations. The mind unconsciously focuses on elements of the chart that ‘fit’ the subject and mutes or discards the others. As a symbolic pattern however astrology does provide interesting ways of thinking about personality and character traits, and offers a symbolic theatre where the game of fate is ‘played’ out. It is this language available for thinking about personality which is attractive to us in the absence of any profound alternative. Certainly Freud and Jung and their successors have not provided an accessible or credible means of describing normal human character and behaviour. A deep scepticism about astrology is appropriate, and in itself it can have no predictive power, but the theatre remains strangely attractive.

Perhaps we might say that in the Elizabethan age these things would have been taken seriously, where in our age it is hard to do so, and thereby legitimise an astrological view of the events of that time? Essex ‘fits’ his charts. He is the moody, touchy, fatal, attractive Scorpio par excellence, his birth chart full of tension. Typecast as Sydney’s successor, courtier, soldier, horseman, he is a part of the aristocratic culture. He is faced with a new breed of men, rising to that aristocracy, who were not raised on Castiglione’s ‘The Courtier’, who rarely if ever held a weapon. He is also a last romantic, an intense personality steam-rollered by a rising order based on intelligence, cunning and pragmatism. He was doomed to fail.

The planet Pluto, unknown in Elizabethan times, is now assigned to Scorpio, and links to the fundamental interior of the psyche. Pluto is identified in its movements through the skies as the gateway to humility, to acceptance of greater powers than oneself. Helios warns his son Phaethon that he must pass the Scorpion’s cruel pincers on his journey through that circuit where there are no sacred groves, or cities of the gods, past Taurus the white bull of Mithras, Sekhmet the lion-goddess, the Archer and the Crab, past every sign of the Zodiac, in order to return. It was a Scorpion that attacked Orion, in that aggression characteristic of the sign, ruled also by fiery Mars, lord of violent catastrophes. And Scorpion-men rebelled against Osiris in the Egyptian myth.

Scorpio erupts from the bowels of the earth, from underground, from the hidden realm, from the waters of beginning, the moisture of generation, primal, natural, powerful, and creative. The waters of Artemis’s sylvan pool, secret and leaf-shadowed become the fearful tears of Actaeon as he sees his transfigured shape as a deer, and then become the blood and fluids seeping into the ground from his torn carcass. They are the libation to the earth, the token of sacrifice, the flesh and blood, the transubstantiated wine and bread, the veins and flesh. That place of dampness is the place of offering. From the dark grove in the woods, to the stone altar. In all the intimate exchanges of life.

Essex is part of the mythological tension and power of Elizabethan times. They move us because they are close to the archetypal patterns of existence in a way our times are not. Yet he is also part of that process of challenge, rebellion, refusal of the crooked conditions, which destroyed the myths. He and Elizabeth argue. He turns his back on her, she, furious, boxes his ears. He storms out leaving the spectators dumbfounded. She is mortal, and mortally offended. He aspires, and is not afraid to challenge her. Can Essex really be a precursor of the Protestant ethic? Can the last of the aristocratic challengers be also the forerunner of the Civil War, of the men who wrested power from the Crown and vested it in Parliament? Can the receiver of Royal favours, spell also the end of Royal prerogatives? Is Essex, that sacrifice to ensure the continuity of a reign, the fruitfulness of the established order, also the revelation of that injustice and arbitrary despotism which will lead to the execution of a king, and the end of that order?

Regardless of what he himself thought, his end had symbolic meaning for others. That is also true of Raleigh. Discontent with the judgements against them, was added to that simmer of discontent, that desire for freedom, which is always apparent below the surface of Tudor and Elizabethan society. Desire for freedom of thought, for justice, for liberty of conscience and religion, for participation in the exercise of power, for removal of the burden of arbitrary taxation, for access to the means of livelihood. Ironic that Sir Edward Coke, the man who conducted travesties of justice in the trials of Essex and Raleigh, should by the end of his life have rejected the manipulation of the courts by the crown. Overturning his own prior judgements, he went on to enshrine in his exposition of the Common Law rules of justice, for future generations to enhance.

The English people preferred fair play to arbitrary justice, even arbitrary mercy. The mythic crown, the crown of power, was losing its sacred inviolability. Ideas were the new coinage, enshrined in words, passed from mind to mind, that would seal the contracts of the future. Essex did not challenge the crown in the name of the people. But the people took up the challenge in their own name. History may make myths out of men who in themselves embody something other, even something opposite. History too is confused by the bright, glittering light, and the image silhouetted against the dawn.

And that idealism too, derived from the Italian Renaissance. The idealism, which drives the fantasy of the Virgin Queen, the chivalry of the courtier-poet, that, encourages transmutation of the sordid realities for a greater dream. It is the gorgeous hyperbole of Marlowe’s line. It is the sweetness of Shakespeare’s verse. It is Hilliard’s miniatures, those icons of jewelled excellence. It is the windowed form of the Tudor great houses, and the freshness and clarity behind the music and poetry of the age. It is the intensity and excitement, which intoxicates minds. That idealism is transferred in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, from the arts to politics, from thought to action, from the glamour of the old England to the struggle for power and liberty of the new.

It was an age obsessed with the concept of order, because it was an age reaching out for the new, and like ours struggling with the challenge of absorbing that newness into the fabric of the old. The Elizabethan frontiers were global exploration, trade, and the birth of science and empire. Our frontiers are technology, genetics, the environment, and human misery. At stake in both societies: individuality and freedom to fulfil human potential. At stake in both societies the potencies of the past, of nature and the Goddess: and the potencies of the future, the transformation of minds and bodies, the power of commerce and wealth.

The clamour at Essex’s death was a small part of that great challenge the inception of which, through an irony, Elizabeth’s reign saw. It challenged the ancient powers of sacred law and inherited structure. The Elizabethan Age opened the floodgates to new knowledge, allowed out the genie that can never be bottled up again, raised the lid on Pandora’s box, ate from the tree. The Elizabethans continued the destruction of the Goddess. As Cordelia, as Desdemona, as Cleopatra, the loving and the carnal Goddess. They altered the forms of prayer to de-mystify. They turned power away from the Church. And what was started, what men like Marlowe, and Essex, Raleigh and Donne furthered, was an exaltation of reason and intellect, of individuality and secular energy, of direct communication with a masculine God, with Jehovah, of democratic procedure, of written law, of commerce run by men, of science carried out by men. Shakespeare’s concern with justice, with the war between the rational and the bestial, understanding and blind instinct, will and appetite, reflects the fierceness with which the battle for pure reason was addressed in his age and the next.

The Goddess, metaphorically speaking, went down to defeat in the Civil War alongside the sacred crown. The irrational, the mythical, the passionate life of the feelings, the caring and loving, the power of the female, was suppressed. In the following centuries and in our own times it lives on in the arts, in music, the novel, and poetry; in environmentalism; in charitable activities; in the private and personally motivated world. But power in the secular and social world has irreparably passed. Science, commerce, consumption of the resources of nature, nature seen as a resource, the economic weight of a materialistic society, raises the secular odds against the Goddess.

The people of classical Athens also struggled with the same issues and failed to resolve them. How were spiritual needs to be fulfilled in a rational age? Were religions which originated in an outmoded social context meaningful in modern times, when the Gods were being discarded from intellectual discourse, or relegated to fringe cults, and suspect mysticism? Where was the emotional substitute for the ancient values which rationalism eroded? Yet for them and for us, the survival of the spirit, seemed absolutely to depend on the survival of sacredness and love, that is the Goddess in her benign aspects. At stake also the survival of the natural world, the survival of the very concept of the human mind and body, the survival of liberty, of freedom in time, space and thought. The rampant militarism of the imperialistic Macedonians, of Philip and Alexander, provided no answer.

There is an analogy in classical Greece also for the envy and pettiness that seems to corrode Elizabethan public life, a wasteful carelessness where talent and originality are concerned, as though the supply of greatness and originality from the tap is endless. Athens at the same time that it recognised the power and excellence of the creative individual grew nervous, exercised ostracism by vote. Cimon, Themistocles, Aristeides, were all exiled. Miltiades and Socrates imprisoned and eliminated.

Jealousy is a powerful motive, in public opinion or in a monarch. Elizabeth resented those who encroached on her power, loved those who exercised it by gift on her behalf so long as they exercised it in the way she wanted. James’s envy of Raleigh was an element in Raleigh’s destruction. Who else combined intellect with courage, control with eloquence, good looks with manners, grace with wit, achievement with endurance, and longevity with multifarious energies as Raleigh did? Hard not to be envious of such a Renaissance man. Jealousy and Envy - apprehension of losing what one believes is one’s own, grudging contemplation of the more fortunate other. The individual, Essex, is countered by the loyal factions, by the law, by propaganda, by control and penalty, by conditions, crooked if necessary, that bind him into the body politic.

Not just those who have seen or betrayed a secret, Sisyphus, Prometheus, Actaeon, Pentheus, but also those who deviate from the norm, who pursue an individual course, must be punished. Those who exhibit excess in all its aspects are punished by gods or men. Arachne for weaving too well, Ariadne for loving too well, Lucifer and Phaethon for pride, for aspiring to be equal with the deity, Midas for love of gold, Narcissus for love of his own beauty. The individual is punished. The gods are jealous of their powers, and envious of those powers mirrored in a mortal. They are also the purveyors of justice, and punish those who overstep the mark. Hubris, pride, ends in ate, downfall.

In Shakespeare’s major tragedies his male protagonists are driven by a corrupting vision to passion and by passion to excess. They are punished by the loss of their soul often embodied in a woman they loved, whose purity of motive in action is the silence of the loving spirit. Shakespeare identifies these heroines with natural order, with speechless simplicity and sincerity, with the Goddess in her beneficent mode. The passion that causes their agony is a vision of the Goddess in her malificent mode, carnal, anarchic, festering, goading and seductive. The heroines are an incarnation of natural reason. The heroes an incarnation of irrational passion. But both arise from nature. Shakespeare’s problem is our problem, how to live rationally without killing the spirit, without chilling the soul, how to be passionate without destroying order, without calling down on ourselves the wrath of the gods, the wrath of society. His answer is Love. A temporary almost momentary magic exercised through creativity, awareness, intelligence, respect, and grace. Essex is a passionate protagonist who sees a corrupted vision of the Goddess. His reaction seems like madness. Is it a false vision, in which case Elizabeth plays the role of the betrayed Goddess, and Essex’s failure is the failure to offer humility, loyalty, and love? Or does it have substance, in which case Elizabeth is the Queen of Hell, tormenting, frustrating, wronging, and discarding the abused hero?

Essex steps out of line, almost wilfully. His insurrection is a half-baked affair, without sensible resources or support, unfocused, amateurish, misaligned with public opinion. It is the act of a frustrated man, frustrated with himself. Has he been scheming with James and Cecil over the Stuart succession? Elizabeth herself has accepted that succession. He is near bankrupt, how will this craziness help his depleted finances? Is he ill, deranged? Likely his summons to appear before the Privy Council, which he refuses, forces his hand. A badly planned coup is executed prematurely. The plot if there is one is forestalled. The timing is destroyed by Egerton, Knollys and Popham arriving at Essex House where they are promptly held as hostages. The Earl’s march into the City runs into the soldiers in Ludgate Street. Empty streets, an unprepared populace, a nervous Sheriff, it is all an execrable fiasco.

The keynotes seem to be hysteria on Essex’s part, foolish support from his immediate circle, and a lack of clear purpose or leverage. Strange. He appears as a man at the end of his tether, isolated, against the wall. To pursue him therefore, as Elizabeth now does, seems vindictive in the extreme. She too seems hysterical. They are more like crazed lovers, the pair of them, than sensible agents of power. Coke and Bacon and Egerton do the dirty work for her. On that Sunday the eighth of February the Earl of Essex effectively throws his life away. On the ninth he is in the Tower.

Why not imprison him under house arrest as had been done before? He had failed the Queen in Ireland, stormed in on her at Nonesuch. She was furious. Her response on that occasion was to place him in the custody of Lord Keeper Egerton in York House on the Strand, Egerton’s official residence. Access to his wife and newly born child was denied. He stayed there all winter and was released to his own Essex House, in March of 1600. In the June of 1600 a case against him was opened in front of eighteen Commissioners at York House. Francis Bacon spoke for the Crown after the Attorney General Coke. Essex was accused of disloyalty, of having made a bad treaty with Tyrone in Ireland, and of other things.

The Queen was interested in allusions to the play of Richard the Second, which had been performed for the Essex set, as it came dangerously close to raising the Tudor claim to the throne. Bacon quoted from a letter where Essex had said the Queen was obdurate. ‘By the common law of England’ said Bacon referring to Elizabeth ‘a prince can do no wrong.’ Essex knelt in front of his judges, was humble, and expressed his loyalty and devotion. Essex was to return to his own house, effectively imprisoned there, barred from the Privy Council, dismissed as Earl Marshal. Bacon told the Queen she had won a victory over fame and a great mind and that she might now receive Essex again with tenderness after his humiliation.

Shakespeare in Troilus and Cressida suggests through Ulysses’s (Raleigh’s) mouth the necessity of that humiliation. ‘The seeded pride, that hath to this maturity blown up in rank Achilles must or now be cropp’d or, shedding, breed a nursery of like evil to overbulk us all.’ Essex exchanged letters with Bacon. Bacon explaining that his higher loyalty was with the Queen, and speaking of Icarus. Essex was accepting and courteous in reply, professing himself a stranger to poetical conceits, and saying that if he had wings he was no bird of prey. Not the letter of a hysteric or a madman.

What was so heinous about his offence this time that required his death rather than imprisonment? Seeking to gain the popular support of the people of London, acting aggressively under the influence of Mars the soldier’s planet, conspiring with the Scots? Essex, anti-Spanish, staunch Protestant, was an unlikely rebel, and his emotional appeal to the people was hardly vindicated by their indifference, their lack of support demonstrating their dislike of wilful insurrection and violence.

His defence at his trial was that he feared being attacked by his enemies; that there was a plot against him; that England was at risk from a secret deal with the Spanish Infanta over the succession. ‘If I had purposed anything against other than my private enemies, I would not have stirred with so slender a company’ said Essex. But it was judged treason, though Essex claimed he had no intent against the Queen. Something had mortally offended her. Raleigh’s words, about Essex being too free with comments about her crookedness? The references to Richard the Second and the issue of Tudor legitimacy? Her fears that the desire of England for an English succession focused unrealistically on this man? His anti-Spanish stance? The vindictiveness of an old woman? A desire for tidiness and order? Or was it merely an opportunity to demonstrate the power of the Crown, and the punishment for dissent? Was it merely the conditioned reflex of an increasingly authoritarian State?

Raleigh the rival, the Captain of the Queen’s Guard, was required officially to be present at the execution. Prevented by Essex’s friends from coming too near the platform, or deliberately sacrificing his own place on the platform to them, Raleigh watched the execution from a window of the Armoury. Later it was said he had smiled at the execution, puffed tobacco smoke at the Earl. He himself was told that Essex had asked for him at the end, to enable a reconciliation. He bitterly regretted that it had not happened, and mentioned it at his own execution. Raleigh could see which way the wind was blowing.

The world of myth, of daring, of enterprise, of the bright glare of the sun, is the world of risk. Everything there is larger than life, beyond life, toying with death, understanding death’s many masks. The libation is poured on the ground. It is the hero’s blood. Execution is a ceremony with a priest, like marriage, or coronation. The individual alone has come so far, now, limited by what the god allows, he completes the mortal journey. The grave marker is also a winning post; the stele is also a herm. To do the wrong thing at the wrong time, to worship the wrong god, is sin. Having fallen with Adam, the individual acknowledges sin, and seeks salvation through a return to the redeeming light.

The shape of Essex’s fate is mythologically visible, an attempted ascent beyond the limits ordained, a Fall, and then through confession and redemption a re-ascent. It is the shape of Protestantism. It is the shape of Genesis completed by the Crucifixion and the Ascension. Life can be cured in death. To fall is only temporary in the soul that confesses. Essex confesses and regrets his crimes. He forgives those around him. They are actors in a ritual who shall not carry individual blame for an act of expiation and renewal. He is not sliding down the slippery slope to infernal torment, has not fallen forever from the glittering crest of the great wave. Now he is returning to God, on the day of the Goddess.

In myth, sacrifice, demanded by justice, or freely accepted, is a confirmation, an offering. It can be seen as purification. A mythological circuit is completed. The action burns itself out, and the promise of the myth is fulfilled, confirmed and renewed. The social bond is asserted. The sacrificed one is a victim, but also triumphs, goes down, but also goes beyond. The mortal one is the bride or bridegroom of death: is wreathed like the winner at the Games, like the poet or poetess, with laurel leaves. He or she becomes Royal. The sacred wreath is also a crown. The crowd are participants, celebrants. They are purged by tragedy, by the reliving of the myth in the emotions, and along the nerves. The community becomes a communion, a meeting in accepted truth, in common faith.

Where there is injustice however, regardless of its final acceptance by the individual sacrificed, then the crowd is not a group of participants, but of alienated spectators. Nothing is purged. Grief and burning memories are created. Tragedy is born, not reconciliation. Myth is made and charged with the energy of uncompleted business. The sacrificed one is a martyr, and the sacrifice is only absorption, destruction, annihilation, holocaust.

Out of the unjust sacrifice, as out of the mouth of raped Cassandra, comes a dark stream of warning, of ‘ancestral voices prophesying war’. Essex’s trial was seen as a travesty, his sentence the result of his enemies’ connivance, his execution as unjust. William Camden, the historian, writing in James’s reign commented ‘To this day there are but few that thought it a capital crime.’ Cecil and Raleigh were vilified at the time. Essex’s death became part of the complaint of ‘axes and taxes’ which expressed London’s discontent as Elizabeth’s reign ended, in the perception of authoritarianism combined with meanness, that stemmed from an inadequate economy and the aged Elizabeth’s mortal insecurity.

Essex’s mistakes were forgotten. His glittering presence, tempered with an apparent regard for the people of London, was the image of him that was taken up in the popular ballads. He represented, in some way, the glory of English arms. The military success at Cadiz was remembered, even though to Elizabeth the venture was unsatisfactory, in failing to benefit the exchequer. Essex’s death ensured his posthumous popularity. For Essex to achieve that popularity it is clear that the Tudor regime had become deeply unpopular. ‘The country hath constantly a blessing for those whom the court hath a curse.’ The apparent injustice of his death fed those hidden fires that were burning under Tudor and Stuart England, a deep resentment, whose fruits were to come.