Geoffrey Chaucer

The Canterbury Tales

XI

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2007, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

The Squire-Franklin Link

Here follow the words of the Franklin to the Squire and the words of the Host to the Franklin

‘In faith, Squire, well you did yourself acquit

And right nobly too; I applaud your wit,’

Quoth the Franklin, ‘considering your youth,

Feelingly you spoke, sire, all praise to you!

In my opinion, not a one that’s here

Can match your eloquence, or be your peer,

While you’re alive; God give you now good chance,

And of your powers send you continuance,

In your speech I took great pleasure, truly.

I have a son, and by the Trinity,

Rather than have twenty pounds in land,

Though right now it came into my hand,

I’d have him be a man of such discretion

As you are. Fie, then, on mere possession,

If a man be but virtuous withal!

I my son have chided, and shall do more,

For he to virtue’s word will ne’er attend,

All he can do is play at dice, and spend,

Lose all that he has, through such ill usage.

And he’d rather talk with some lowly page

Than commune with a true gentle knight,

From whom he might learn gentleness aright.’

‘That, for your gentleness!’ quoth our Host.

‘What, Franklin! Pardee, sire, well you know

That every one of you must tell the rest

A tale or two, or deny my sworn request.’

‘That know I well, sire,’ quoth the Franklin,

‘I pray you, hold me not in your disdain,

Though to the Squire I spoke a word or two.’

‘Tell on your tale, let’s have no more ado!’

‘Gladly, sir Host,’ quoth he, ‘I will obey

Your every wish; now hark to what I say.

I will be contrary to you in no wise,

As far as my humble wit may suffice.

I pray to God that it may please you, too;

Then will I know that it is good, and true.

The Franklin’s Prologue

The Prologue to the Franklin’s Tale

The noble Breton lords, in olden days,

From various adventures, fashioned lays,

Rhymed them in the earliest Breton tongue,

Which lays to their instruments were sung,

Or else were read to them for their pleasure;

And one I do recall, in some measure,

Which I’ll relate as well as ever I can.

But sirs, since I’m an unlearned man,

At the beginning first I do beseech

That you excuse my unpolished speech.

I never learned rhetoric, that’s for certain;

And whatever I speak is bare and plain.

I never slept awhile on Mount Parnassus,

Nor studied Cicero, that’s Marcus Tullius.

Adornments I have none, ah, true indeed,

Only such colours as adorn the mead,

Or else such as are used to dye and paint.

Rhetoric’s hues to me are dull and quaint

My spirit knows little of them, I fear.

But if you listen, you my tale shall hear.

The Franklin’s Tale

Here begins the Franklin’s Tale

In Armorica, now called Brittany,

There was a knight that loved, and truly he

Strove to serve his lady in best wise.

And many a labour, many an enterprise

He for his lady wrought ere she was won;

For she was among the fairest under the sun,

And also she came of such a high kindred

That the knight scarcely dared, for dread

To tell her of his woe, pain, and distress.

But at the last, seeing his worthiness,

And especially his humble obeisance,

She took such pity on his true penance

That privately they entered in accord,

She to make him her husband and her lord,

With such lordship as men have over wives.

And to live in greater bliss all their lives,

Of his free will he swore to her as knight

That never in all his life, day or night,

Would he take upon himself the mastery

Against her will, nor show her jealousy,

But obey her, and follow her will in all,

As any lover in his lady’s thrall;

Save that the name alone of sovereignty

Should he have, lest it shame his dignity.

She thanked him, and with full great humbleness

She said: ‘Sire, since, of your gentleness,

You’ll allow me to have so great a rein,

May God grant that never between us twain,

Through guilt of mine, be any war or strife.

Sire, I will be your humble loyal wife;

Or may my heart break first, such is my pledge.

Thus were they both in quiet and at rest.

For one thing, goods sirs, I may safely say,

That lovers must one another fast obey,

If they’d keep company for many a day.

Love will not be constrained by mastery;

When mastery comes, the God of Love anon

Beats his wings, and farewell, he is gone!

Love is a thing as any spirit free.

Women, by nature, wish for liberty,

And not to be constrained, as in thrall,

And so do men, and truth is this for all.

Look who is most patient in their love,

Has the advantage and so towers above.

Patience is a high virtue, that’s certain,

For it achieves, as clerics do maintain,

Things that force is unable to attain.

At every word we must not chide, complain;

Learn to accept, or else, for here below,

You shall learn, whether you will or no.

And in this world, indeed, no one exists

Who does not sometimes speak a word amiss.

Ire, sickness, or the stars’ configuration,

Wine, woe, or our humours’ alteration

Often gives cause to do amiss or speak.

Revenge for every wrong may no man wreak;

According to the time, act with temperance

All you that understand good governance.

And therefore had this wise and noble knight,

Sworn patience, so as to live at ease, aright,

And she to him as earnestly did swear

That he should never find a fault in her.

Here may men see a humble, wise accord!

Thus she makes him her servant and her lord –

Servant in love, and yet her lord in marriage;

Thus was he both in lordship and in bondage.

Bondage? – Nay, in lordship high above,

Since he had both his lady and his love;

His lady, certain, and his wife also,

Which the law of love accords with, though.

And now he had met with such prosperity,

Home with his wife he went to his country,

Not far from Penmarch Point, his dwelling was,

Where he lived in bliss and in solace.

Who can know, unless he wedded be,

The joy, the ease, and the prosperity

That is between a husband and a wife?

A year and more lasted this blissful life,

Till the knight whose story I discuss,

Of Caer-rhud, and called Arveragus,

Determined to go and live a year or twain,

In England, that was also called Britain,

To seek in arms both worship and honour,

For all his pleasure won he from such labour,

And dwelt there two years; the book says thus.

Now I’ll cease to speak of Arveragus,

And I will speak of Dorigen his wife,

That loved her husband as her heart’s life.

At his absence she wept sore and sighed,

As does when she will the noblest bride.

She mourned, waked, wailed, fasted, cried;

While longing for his presence thus denied,

So that all this wide world she set at naught.

Her friends, who knew the burden of her thought,

Comforted her, when they could, in every way.

They preached at her, telling her night and day,

That she was killing herself, in vain, alas!

And every comfort possible that was

Useful they gave, made it all their business,

To try and put and end to her heaviness.

By a slow process, known to everyone,

Men may carve away so long in stone

That some figure may thus imprinted be.

So long had they comforted her that she

Received, through hope and through reason,

The imprint of their endless consolation,

And they began her sorrow to assuage;

She must not always let her feelings rage.

And Arveragus, amongst all this care,

Had sent letters, speaking of his welfare,

And how he would return swiftly again;

Else this sorrow would her heart have slain.

Her friends saw her sorrow start to abate,

And begged her on their knees, for God’s sake,

To come and roam about in company,

To drive away her gloomy fantasy.

And finally she granted their request,

Because she saw that it was for the best.

Now, her castle stood close by the sea,

And often with her friends wandered she,

To take her pleasure, on a bank full high,

Where she saw many a ship and barge go by,

Sailing their course, wherever they chanced to go.

But that too was a portion of her woe,

For to herself, full oft, ‘Alas!’ said she,

‘Is there no ship, of all these that I see,

Will bring me my lord again? Then my heart

Would be cured of bitter sorrow’s smart.’

At other times she would sit and think,

And cast her eyes downward from the brink.

Yet when she saw the ghastly rocks all black,

For fear indeed her heart would almost crack,

On her feet she could scarce herself maintain.

Then would she sit upon the grass again,

And piteously the flowing tide behold,

And speak as thus, with sorrowful sighs cold:

‘Eternal God that through your providence

Lead the world in certain governance,

You made nothing in vain and yet, alack,

Lord, these fiendish, grisly rocks all black,

That seem to me rather a foul confusion

In their work, than any fair creation

Of such a wise and perfect God, thus able,

Why have you wrought this work unreasonable?

For by this work, south, north, west or east

There is nurtured neither man nor beast.

It does no good, to my mind, but annoys.

See you not, Lord, how mankind it destroys?

A hundred thousand souls, among mankind

These rocks have slain, no more brought to mind;

Yet mankind’s so fair a portion of your work

You made it in your image, says the clerk.

Thus it seems you had both love and charity

Towards mankind; so how then may it be

That you created such means to destroy?

– Which do no good, but evermore annoy.

I know, indeed, that clerics will attest,

To arguments, that show all’s for the best,

Though what the reasons are I do not know.

But may the God that made the winds to blow

Keep safe my lord! – That is my conclusion.

To clerks I leave all the disputation.

But would to God that all these rocks so black

Were sunken into Hell, and came not back,

For his sake, they slay my heart with fear!’

– Thus she did say, with many a piteous tear.

Her friends could see she derived no sport

Roaming by the sea, but pure discomfort,

And chose to take their pleasure somewhere else.

They led her among rivers, and by wells,

And through other places all delightful;

Danced, played chess, backgammon, to be helpful.

So one day, right in the morning-tide,

Unto a garden that was there beside,

Into which had been taken as they planned

Victuals and other things at their command,

They went to sport and play the livelong day.

And this was on the sixth morn in May,

When May had painted with his softest showers

The garden, filled with leaves and with flowers;

And man’s handicraft so skilfully

Arrayed had all this garden, truthfully,

That never was there a garden so prized,

Unless it were the ancient Paradise.

The odour of flowers and the fresh sight

Would have rendered any heart light

That ever was born, unless some great sickness

Or great sorrow consumed it with distress,

So full it was of beauty and elegance.

And after dinner they began to dance

And sing as well, save Dorigen alone,

Who ever made plaint, and ever made moan,

For in the dance she saw not him below,

Who was her husband and her love also.

But nonetheless she must a while abide,

Be of good hope, and let her sorrow slide.

Now in this dance, among the other men,

There pranced a squire before Dorigen,

Who fresher was and jollier in array,

As I do live, than is the month of May.

He sang and danced better than any man,

That is, or was, since ever the world began.

And then he was, if I should him describe,

One of the handsomest of men alive;

Young, strong, right virtuous, and rich and wise,

And well beloved, considered a great prize.

And briefly, truth to tell, as I recall,

Unbeknown to Dorigen at all,

This gallant squire, a servant true of Venus,

Who by name was called Aurelius,

Had loved her the best of any creature,

As was his fate, for two years and more,

But never dared proclaim his suffering;

He drank his sorrow straight from the spring.

He had despaired; nothing he dared say,

Save in his songs something he’d convey

Of all his woe, while generally lamenting.

He said he loved, but was beloved by nothing.

Of such matter he made many lays,

Songs, plaints, rondeaux and virelais,

How that he dare not of his sorrow tell,

But languished as a Fury does in Hell;

And die he must, he said, as did Echo,

For Narcissus, who dared not tell her woe.

In no other manner than this, as I say,

Dare he to her his woe at all betray;

Save that, perhaps, sometimes at a dance,

Where the young folk will keep observance,

It may well be he looked upon her face

In such a manner as man asks for grace,

Though she knew nothing of his intent.

Nonetheless, it chanced, ere they went thence,

Because he happened to be her neighbour,

And was a man of good repute and honour,

And she had known him some time before,

They fell to talking, and more and more

Towards his purpose drew Aurelius.

And when he saw his chance, he spoke up thus:

‘Madame,’ quoth he, ‘by God who this world made,

If I had known your heart felt no dismay,

I wish that day when your Arveragus

Crossed the sea, that I, Aurelius,

Had gone too, never to return again.

For I see now my service is but vain;

My reward is but the breaking of my heart.

Madame, have pity on my bitter smart,

For with a word you may me slay or save.

Here at your feet, would God, they dug my grave!

I have no time to say what I would say;

Have mercy, sweet, or death is mine today.’

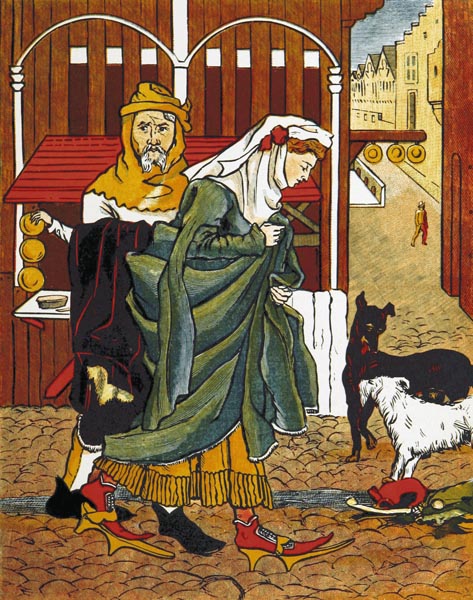

‘Dorigen and Aurelius’

She began to stare at Aurelius.

‘Is that your thought,’ quoth she, ‘and say you thus?

Never have I suspected what you meant.

But now, Aurelius, knowing your intent,

By that God who gave me soul and life,

Know, I shall never play the faithless wife

In word or deed, as far as I have wit;

I will be his to whom I have been knit.

Take that for a final answer now from me.’

But after it teasingly thus said she:

‘Aurelius, by the high God above,

As I wish I might have been your love,

Since I hear you so piteously complain.

Lo, that day when from Brittany’s main,

You remove every reef, stone by stone,

So no ship is hampered through that zone –

I say, when the coast is rendered so clean

Of rocks, that never a stone can be seen –

Then I will love you more than any man.

Hear my truth said, as plainly as I can.’

‘Is there no better grace in you?’ quoth he.

‘No, by the Lord,’ quoth she, ‘who fashioned me,

For I know full well it shall never betide.

Let such folly out of your heart slide!

What pleasure is added thus to a man’s life

In making love to another man’s wife,

Who can have her body when he will?

Aurelius was ever in deeps sighs still;

Woe was Aurelieus, when this he heard,

And with sorrowful heart he answered her:

‘Madame, to lose you is impossible!

So let death come, sudden and horrible.’

– And with that he turned away anon.

Her other friends appeared, many a one,

And in the alleyways roamed up and down,

Knowing nothing of this sad conclusion.

And suddenly the revels began anew,

Till the bright sun had lost his yellow hue,

Since the horizon robbed them of his light –

Which is as much as to say, that it was night.

And home they went, in joy and in solace,

Save only poor Aurelius, alas!

He to his house has gone, with sorrowful heart.

That he and death shall not be long apart,

He feels, and senses his heart grow cold.

Up to the heavens he his hands does hold,

On his bare knees then he sets him down,

And in a rage of feeling says his orison.

For woe his wits were addled in his head;

He knew not what he spoke, but thus he said.

With piteous heart his plaint was thus begun

Unto the gods, and first unto the sun.

‘Apollo,’ said he, ‘God and governor

Of every plant, and herb, tree and flower,

Who gives, according to your declination,

To each of them its time and season,

As your position changes, low or high,

Lord Phoebus, cast now your merciful eye

On sad Aurelius, wretched and forlorn!

Lo, Lord, my lady now my death has sworn

Though I am guiltless, your benignity

Upon my doomed heart may yet take pity.

For I know, Lord Phoebus, if you wished,

You, save for my lady, could help me best.

Now vouchsafe me that I might advise

You how I may be helped, and in what wise.

Luna, your sister blest, who bright does sheen,

And of the sea is chief goddess and queen,

(Though Neptune has the mastery of the sea,

Yet empress high above him still is she),

You know, Lord, that just as her desire

Is to be quickened, lighted from your fire,

And thus she follows you diligently,

So does the sea desire, naturally,

To follow her, since she is the goddess

Of both the sea and rivers, great and less.

Wherefore, Lord Phoebus, this is my request –

Perform this miracle, or my heart may burst –

That even now at your next opposition,

When you are in the sign of the Lion,

Beg that she so great a flood will bring

That five fathom at the least it may spring

Higher than the highest rock in Brittany,

And for two years let this great flood be.

Then, surely, to my lady I may say,

“Hold to your pledge; the rocks are all away.”

‘Lord Phoebus, do this miracle for me:

Ask her to run her course no more swiftly

Than you, I say, request that your sister go

No faster than you, these two years though.

Then she will be at full the entire way,

And the spring flood last both night and day.

And if she’ll not vouchsafe in that manner,

To grant to me my sovereign lady dear,

Beg her to sink each rock deeper down

Into her own dark region underground

The shadowy kingdom Pluto dwells in,

Or nevermore shall I my lady win.

Your temple at Delphi I’ll barefoot seek,

Lord Phoebus, see the tears run down my cheek,

And on my pain have some compassion!’

And with that he swooned after a fashion,

And lay on the ground a long time in a trance.

His brother, who knew of this mischance,

Caught him up, and to bed had him brought.

Despairing, filled with his tormented thought,

I’ll leave this sorrowing creature there to lie;

Let him choose whether he’ll live or die!

Arvegarus, in health, with great honour,

Like one who was of chivalry the flower,

Is home again, with other noblemen.

O joyous are you now, sweet Dorigen,

Who have your gallant husband in your arms,

The fresh knight, the worthy man at arms,

Who loves you as he loves his own heart’s life!

Nothing made him suspect that to his wife

Any man had spoken, while he voyaged about,

Of love indeed, nor was he plagued with doubt.

He gave not a thought to any such matter,

But danced, jousted, and made much of her.

And so in joy and bliss I’ll let him dwell,

And of the ill Aurelius I will tell.

Languishing, and in torment furious,

Two years and more lay sad Aurelius,

Before the ground he dare set foot upon.

Of comfort all this time he had none,

Save from his brother, who was a clerk.

He knew of all this woe and all this work;

For to no other creature, it is certain,

Dare he a single word of this explain,

In his breast bore it discretely rather,

More so than Pamphilus for Galatea.

His breast was whole, as outwardly was seen,

But in his heart was ever the arrow keen;

And a wound unhealed, with surface scar,

In surgery is perilous of cure

Unless they touch the arrow, or come thereby.

His brother wept, away from public eye,

Till finally he fell into remembrance

That while he was at Orleans in France –

As students who are young and zealous

To read in arts abstruse and curious

Seek every nook and cranny, in turn,

The recondite sciences for to learn –

He recalled that once, upon a day,

In the college, at Orleans, as I say,

A book of natural magic, he saw

Because his friend a bachelor of law,

Though he was there for other study,

Left it lying, on his desk, discretely.

Which book spoke fully of the operations

Touching the eight and twenty mansions

Belonging to the moon, and suchlike folly,

Considered, in our day, not worth a flea;

For Holy Church’s faith, to our belief

Allows no like illusion to bring grief.

And when this book entered his remembrance,

Swiftly his heart for joy began to dance,

And to himself he said thus, privately:

‘My brother will be cured right swiftly;

For I am certain there are true sciences

By which men conjure up appearances,

Such as the subtlest conjurors display.

For often at feasts, have I heard men say,

Conjurors within a hall, full large,

Have filled a space with water and a barge,

And in the hall have rowed up and down.

Sometimes a grim lion have they shown,

And sometimes flowers sprang up instead,

Sometimes a vine with grapes white and red,

Sometimes a castle, all of lime and stone,

And when they chose, they banished it, anon;

Or so it seemed, to everyone in sight.

‘Now then, I deduce, that if I might

At Orleans some old learned fellow find

Who has the lunar mansions in his mind

Or other natural magic, as above,

He could ensure my brother had his love.

For by illusions a learned man, in fact,

Could make men think that all the rocks black

Of Brittany had vanished every one,

And ships along the shore might go and come,

And then maintain the sight a week or so,

So may my brother be cured of his woe;

Then she must keep to all her promises,

Or bring shame on herself, I’d suggest.’

Why must I make a longer tale of this?

To his brother’s bed he came, and all his

Comfort brought, urging him to be gone

To Orleans, that he started up anon,

And forward on the road did he fare,

Hoping to be eased of all his care.

When they had almost come to that city,

Only two furlongs short, or maybe three,

A young clerk, roaming by himself, they met,

Who greeted them in Latin, at the outset,

With great politeness, and this wondrous thing:

‘I know,’ quoth he,’ the reason for your coming

And before a foot more they onward went,

He told them all about their true intent.

Our Breton scholar asks him then to say

What has become of scholars of past days,

Whom he once knew: dead as it appears,

At which he weeps a plethora of tears.

Down from his horse Aurelius got, anon,

And with the magician forth was gone

Home to his house: he set them at their ease.

They lacked no refreshment that could please;

So well provisioned a house as was this one

Aurelius in all his life had seen none.

Conjured for him, ere they went to supper,

Were forests, parks, filled with wild deer;

Where he saw stags with antlers high,

The largest ever seen by human eye.

He saw a hundred of them slain by hounds,

Some, shot by arrows, bled from bitter wounds.

And when they had all vanished, these wild deer,

Came falconers beside a river fair,

Who with their hawks had many heron slain.

Then he saw knights jousting on a plain;

And after this in conjured elegance,

He saw his lady there as she did dance,

And he himself was dancing, as he thought.

And when the master who this magic wrought

Saw it was time, he clapped his hands, and lo,

Farewell all our revel, it vanished so!

And yet they had not moved from the house,

While viewing all this sight so marvellous,

But in his study, with his books, the three

Of them sat still, and no one else to see.

His squire then was summoned by the master,

Who said to him: ‘Is all prepared for supper?

Almost an hour it is, and no mistake,

Since I bade you our supper swiftly make,

While these worthy men I took with me

Into the study, to view my library.’

‘Sire’ quoth the squire, ‘I’ll make a vow

That it is ready, you may eat right now.’

‘Let us go sup, then, ‘quoth he, ‘that is best.

Amorous people too must sometimes rest!’

After the supper they bargained freely

As to what sum the master’s prize should be

For removing all the rocks from Brittany,

From Gironde too, to the Seine’s estuary.

He showed reluctance, swore, for God’s sake,

Less than a thousand pounds he would not take,

Certainly, for that sum he would have none.

Aurelius with blissful heart anon

Answered thus: ‘Fie on your thousand pound!

This wide world of ours, men say is round,

I would give that, if I were lord of it!

The bargain’s made, take what you think fit;

You shall be paid, truly, on my oath.

But look you now, no negligence or sloth

Must keep us here longer than tomorrow.’

‘Nay,’ quoth the scholar, ‘on my faith, I vow.’

Aurelius went to bed, as he thought best,

And well nigh all that night he took his rest.

Tired with his labour, yet with hopes of bliss,

Ease to his woeful heart came not amiss.

On the morrow, as soon as it was day,

To Brittany they rode the nearest way,

Aurelius, with the scholar at his side,

And descended, where they would abide.

It was, then, say the books, as I remember,

The cold and frosty season, in December.

Phoebus waxed old, and in this station

Dull brass was he, who in high declination

Shines like burnished gold with rays so bright;

But now in Capricorn he shed his light,

Where full pale he shone, I dare maintain.

The bitter frosts, with winter’s sleet and rain,

All the garden greenery had interred.

Janus sat by the fire with double beard,

And from his bugle-horn he supped his wine,

Before him brawn of the sharp-tusked swine,

And ‘Sing, Noel!’ cried every lusty man.

Aurelius, doing all that ever a man can

Gave the master good cheer and reverence,

And prayed him to employ his diligence

To release him from his pain’s fierce smart,

Or plunge a sword into his very heart.

The subtle clerk took pity on the man

And night and day as swiftly as one can

Sought out a time to achieve conclusion,

That is to say create the right illusion

By deft appearance, conjuror’s mystery –

I lack the terms for such astrology –

That she and everyone would think and say

That from Brittany the rocks were all away,

Or else had been sunken underground.

So, at last, the proper date was found

To try his tricks and work the wretchedness

Of all such superstitious cursedness.

His Toledan tables forth he brought,

Rightly corrected, so he lacked for naught,

Neither for blocks nor individual years,

Nor to fix the root, lacked nothing here

For his equations of centre, argument,

And the proportionals convenient

For the calculation of everything:

So, from the stars’ eighth sphere, in his working,

How far the moon’s first mansion had moved

From the first point of Aries above,

That in the ninth sphere considered is;

Full subtly he calculated this.

When he had located the first mansion,

He knew all the rest by due proportion,

And in which sign the moon rose he knew well

And in which face and term, and so could tell

Which was now the moon’s precise mansion,

As a result of all this operation:

And he knew the right observances,

To create such illusions and mischances

As heathen folk employed in olden days.

After which there were no more delays,

And through his magic, for two weeks I’d say,

It seemed that all the rocks were cleared away.

Aurelius, still in despair through all of this,

As to whether he’d have his love or fare amiss,

Waited night and day to see this miracle.

And when he knew there was no obstacle –

And that the rocks had vanished every one –

Down at the master’s feet he fell anon,

And said: ‘I, woeful wretch, Aurelius,

Thank you, lord, and my lady Venus,

Who have freed me from my cares cold!’

And to the temple then away did go,

To where he knew he should his lady see.

And when he saw his opportunity,

With fearful heart, full humbly did appear,

And greeted then his sovereign lady dear.

‘My true lady,’ quoth this woeful man,

‘Whom I most dread and love, deep as I can,

Whom I would in this world least displease,

Had I not suffered for you such miseries

That I must die here at your feet anon,

I’d not have shown that I was woebegone.

But surely I must die, or still complain;

You slay me, guiltless, merely from the pain.

But though to sorrow for my death you’re loath,

Think a while before you break your oath.

Repent you so, and think of God above,

Before you punish me who seek your love.

For, Madame, now recall the pledge I cite –

Though I may claim nothing of you by right

My sovereign lady, but only ask your grace –

Yet in the garden, yonder, in that place,

You well know what you have sworn to me,

And there your troth you plighted loyally

To love me best – God’s witness, you said so,

Albeit that I am unworthy though.

Madame, your honour I speak for, I vow,

More than to save my heart’s life right now:

I have done all that you commanded me,

And if you deign to, you may go and see.

Do as you will; yet have your oath in mind,

For quick or dead, there you shall me find.

With you it lies, to save my life or slay;

But true it is the rocks are now away.’

He took his leave, and she astonished stood.

In her whole face was not a drop of blood.

She had thought never to fall into this trap.

‘Alas!’ quoth she, ‘to suffer this mishap!

I thought it an impossibility

That such a monstrous miracle could be!

It defies the processes of nature.’

And home she went, a sorrowful creature;

For fear, indeed, she could scarcely move.

She wept, she wailed there, for a day or two,

And swooned so, that it was sad to see.

But why she did so, not a soul told she,

For far from town was her Arveragus.

Yet to herself she spoke, lamenting thus,

With pallid face, and sorrowful did appear

In her lament, as you may truly hear.

‘Alas, Fortune, of you I will complain,

Who suddenly have snared me in your chain,

To escape from which I find no succour,

Save only death, or else yet dishonour;

One of these two I must clearly choose.

Yet, nonetheless, I had much rather lose

My life, than see my body suffer shame,

Or know myself as false, and lose my name.

And by my death I may be quit of this.

Has not many a noble wife, and foolish

Maiden, slain herself before now, alas,

Rather than bring her body to that pass?

Yes, for certain; lo, these tales bear witness.

When thirty tyrants full of wickedness

Had Phidon slain, in Athens at a feast,

They ordered his daughters to be seized

And brought before them, humbled in their sight,

All naked, to assuage their foul delight,

And in their father’s blood they made them dance

Upon the pavement – God send them mischance!

For which these woeful maidens, full of dread,

Rather than they should lose their maidenheads,

Broke away, and leapt into a well,

And drowned themselves, as the old books tell.

The Messenians requested that men seek

In Lacadaemon, fifty maidens meek,

On whom they might work their lechery.

But there was none of all that company

That did not slay herself, with good intent,

Choosing to die rather than to assent

And be robbed there of their maidenhead.

Why then of death should I remain in dread?

Lo, then, the tyrant, Aristoclides,

Who loved a maiden called Stimphalides,

Who when her father slain was in the night,

Unto Diana’s temple fled outright,

And grasped hold of her statue too,

From which statue she could not be loosed.

No one there could tear her hands away,

Till in that selfsame place, they did her slay.

Since these maidens died before they might

Be defiled by man’s foul appetite,

A wife should rather kill herself than be

Defiled by any man, it seems to me.

What shall I say of Hasdrubal’s fair wife

Who at Carthage deprived herself of life?

For when she knew the Romans had the town,

She took her children all, and so leapt down

Into the fire, and chose to perish there

Rather than any Roman ravage her.

Did not Lucrece slay herself, alas,

At Rome when she oppressed was

By Tarquin, because she thought it shame

To be alive when she had lost her name?

Of Miletus, the seven maids also

Slew themselves indeed, for dread and woe,

Rather than let the Gauls them oppress.

More than a thousand stories, I should guess,

Might I now tell about the matter here.

When Abradatas fell, his wife so dear

Slew herself, and let her life-blood glide

Into Abradatas’ wounds both deep and wide,

And said: “My body, at the least, I say,

No man shall defile, for I go my way.”

What need of more examples, to explain

How so many women themselves have slain

Rather than be defiled, in misery?

I conclude that better it is for me

To slay myself than be defiled thus.

I will be true to my Arveragus,

Or I will slay myself in some way here,

As did Demotion’s daughter dear,

Because she would not defiled be.

O Scedasus, the heart fills with pity

Reading how your daughter died, alas,

Who slew herself in a similar pass.

As great a pity was felt, or even more,

For the Theban maid who foiled Nicanor

And slew herself, a case of equal woe.

Another Theban maiden died also,

Because a Macedonian her oppressed;

Her death repaid her loss of maidenhead.

What shall I say of Niceratus’ wife,

Who in like case bereft herself of life?

How true also to Alcibiades,

His lover was, who chose to die, as these,

Rather than let his body unburied be?

Lo what a wife Alcestis was!’ quoth she.

‘What says Homer of good Penelope?

All Greece knew her wifely chastity.

Of Laodamia is it written thus,

That when at Troy died Protesilaus,

She would no longer live beyond his day.

The same of noble Portia, I may say:

Without Brutus, she too could not live,

For his was all the heart she had to give.

The perfect wife was Artemisia,

Honoured in Barbary by every peer.

O, Teuta, queen, your wifely chastity

To every wife may as a mirror be!

The same thing I may say of Bilia,

Of Rhodogue, and of Valeria.’

So Dorigen, a day or two, did sigh,

Ever purposing that she would die.

But nonetheless, on the third night,

Home came Avergarus, the noble knight,

And asked her why she wept so sore;

At which she began to weep even more.

‘Alas,’ quoth she, ‘that ever I was born!

Thus have I said,’ quoth she, ‘thus have I sworn’ –

And told him all that you have heard before;

No need to repeat it here for you once more.

Her husband, with kind face, in friendly wise,

Answered, and said as I shall now advise:

‘Is there aught else, Dorigen, but this?’

‘Nay, nay,’ quoth she, ‘God help me, as it is,

It is too much, were it God’s own will!’

‘Yet, wife,’ quoth he, ‘let sleep on what is still.

All may be well, perchance, even today.

You must keep your promise, by my faith!

For, and may God have mercy upon me,

I would rather be slain, mercilessly,

For the very love I have for you, I say,

Than that your word you not keep always.

His word is the noblest thing a man may keep.’

– Yet with these words he began to weep,

And said, ‘I forbid you, on pain of death,

Ever, while left to you are life and breath,

To tell a single soul of this adventure.

As I best may, this woe I will endure;

And show you no countenance of heaviness,

Lest folk may think harm of you, or guess.’

He summoned forth a squire and a maid;

‘Go forth anon, with Dorigen’ he said,

‘And bring her to the place she tells, anon.’

They took their leave and on their way were gone,

But they knew not why she thither went;

He told no one at all of his intent.

Perchance a heap of you, a crowd that is,

Consider him a foolish man in this,

Seeking to place his wife in jeopardy.

Hear the tale, then you may judge her truly;

She may have better fortune than it seems;

Judge when you know whether the tale redeems.

That squire, you will remember, Aurelius,

He, who to Dorigen had proved so amorous,

Happened by chance our Dorigen to meet,

In the town, and right in the busiest street,

‘Lady Crossing the Street’

As she was about to take the road, outright,

To the garden where her troth she did plight.

And he was walking garden-ward also,

For he spied on her wherever she may go

From her house to any manner of place.

So thus they met, by chance or yet by grace,

And he saluted her with glad intent,

And asked her then whitherward she went.

And she answered, as though she were half-mad,

‘Unto the garden as my husband bade,

To keep my word to you, alas, alas!’

Aurelius, stunned at what had come to pass,

Felt, in his heart, a true compassion

For her, and the cause of her lamentation,

And for Arveragus, the worthy knight,

Who bade her keep her word, come what might,

So loath was he to let her stray from the truth.

And in his heart such pity filled the youth,

He thought, considering it from every side,

That he should rather let intention slide,

Than commit such churlish wretchedness

Against generosity and gentleness.

So, briefly, in a few words, he said thus:

‘Madame, say to your lord Arveragus,

That since I perceived his great nobleness,

His treatment of you, in your great distress,

That he would rather be ashamed – sad truth –

Than let you break your word to me, forsooth,

Then I would rather suffer lasting woe

Than ever harm the love between you so.

I release, you, Madame, from your bond,

Quit of every promise, out of hand,

That you have made to me heretofore,

As free as on the day when you were born.

My troth I plight, that I shall never grieve

You for promise given; and take my leave

Of you, the best and the truest wife

That ever I have known in all my life.

Now wives beware of oaths and, for the rest,

Remember Dorigen, let me suggest!

Thus may a squire do a gentle deed

As well as any knight, as you can see.’

She thanked him then, on her knees all bare,

And home to her husband she did fare,

And told him everything you’ve heard said.

You may be sure, he more joy displayed

Than it were possible for me to write.

What more of this story should I cite?

Arveragus and Dorigen his wife

In sovereign bliss lived out their life.

With never any anger there between;

He cherished her as if she were a queen,

And she was true to him for evermore.

Of these two folk, now, you’ll hear no more.

Aurelius, who all the cost had borne,

Cursed the day that ever he was born.

‘Alas,’ quoth he, ‘the promise that I made

Of purest gold a thousand pound in weight

To this philosopher! What shall I do?

I see I must be ruined by loving, too!

My inheritance I needs must sell,

And be a beggar – here I may not dwell,

To shame all my kindred in this place –

And yet he may reveal a better grace.

For nonetheless, perhaps, I might assay

On certain days, year by year, to pay,

And thank him then for his great courtesy.

My word I will keep; no lies for me.’

With sore heart he went to his coffer,

And took his gold to the philosopher,

In value, some five hundred pounds I guess,

And beseeched him, of his gentleness,

To grant him time to pay the remainder;

And said: ‘Master, this boast I make here,

I’ve never failed of my word as yet.

Be sure, I will be quit of all the debt

Towards you, however I may fare,

Though it mean I must beg, and go bare.

If you would vouchsafe, on security,

To give me respite for two years or three,

All would be well, for else I must sell

My heritage; there is no more to tell.’

The philosopher soberly him answered,

And said thus, when he the words had heard:

‘Did I not keep covenant with thee?’

‘Yes, and well and truly, too,’ quoth he.

‘Did you not win your lady, tell no lie?’

‘No, no,’ quoth he, and sorrowfully did sigh.

‘What was the reason? Tell me if you can.’

Aurelius his tale anon began,

And told him all that you have heard before;

No need for me to tell it you once more.

He said: ‘Arveragus, in his nobleness,

Would rather die in sorrow and distress,

Than let his wife to her word be false.’

Dorigen’s sorrow also he told him of,

How loath she was to prove a wicked wife,

Would rather that day have lost her life,

And that she gave her word in all innocence;

She’d never heard of magical disappearance.

‘It made me feel for her such deep pity,

That as freely as he sent her to me,

As freely I sent her to him again.

That’s the long and short; the sense is plain.’

The philosopher replied: ‘My dear brother,

Each of you dealt nobly with the other.

You are a squire, and he is a knight;

But God forbid, in His blissful might,

That a clerk may not do a noble deed

As well as either of you may, indeed!

Sire, I release you from your thousand pounds,

As if you had but now crept out of the ground,

And never, before now, had known of me.

For sire, I will not take a penny from thee

For all my skill, no, naught for my travail.

You have paid well for my bread and ale;

That is enough, and so farewell, good day!’

And then to horse, and forth he took his way.

Lordings, this question will I ask you now:

Who was the most generous, sayest thou?

Now tell me that, ere you farther wend!

I can no more; my tale is at an end.

Here is ended the Franklin’s Tale