François de Chateaubriand

Travels in Italy

(Voyage en Italie)

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2010 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- About This Work

- First Letter to Monsieur Joubert

- Journal

- Second Letter to Monsieur Joubert

- Third Letter to Monsieur Joubert

- Tivoli, and Hadrian’s Villa

- The Vatican

- The Capitoline Museum

- The Doria Gallery

- A Moonlit Walk through Rome

- A Trip To Naples

- Pozzuoli and Solfatara

- Vesuvius

- Patria, or Liternum

- Baiae

- Herculaneum, Portici, Pompeii

- To Monsieur de Fontanes

About This Work

Chateaubriand’s Voyage en Italie, describes his Italian travels in the years 1803-4, during the first of his visits to the country. From France he crossed the Alps to Rome and its environs, from which he subsequently travelled to Naples, where Vesuvius, Baiae, and Pompeii figured amongst the sights he visited. His knowledge of the Classical world informs his wanderings among its ruins, and he enjoys the poetry of the picturesque while reflecting on the grandeur of the past. Rome, for him, represents a meeting of the Classical and Christian worlds, magnificent but in many ways a hollow tribute to human vanity, a theme he will revisit in his later travels to Greece, the Levant and the Holy Land. Naples represents a more picturesque and vibrant Italy. Articulating both cultural quest and voyage for pleasure, Chateaubriand writes of his journey as a ‘tourist’ rather than a scholar or adventurer, penning the work in the form of letters, derived from his travel notes and designed for his interested friends. Here he mingles personal memories with aesthetic and historical perceptions, against the background in which he is most at home, the European heritage, the works of the great poets, landscape and ruins, allowing him to muse freely on transience, the human voyage, and on beauty, found or created.

First Letter to Monsieur Joubert

(Monsieur Joubert, the elder brother of the Advocate General at the Court of Annulment, a man of rare spirit, a superior and benevolent soul, a charming and steadfast companion, with talents that would have won him a well-deserved reputation if he had not desired seclusion; a man too soon snatched from his family, and from that select society bound together by his presence; a man whose death has left in my life one of those voids the years impose on us, and which they cannot repair.)

Turin, the 17th June, 1803

I was unable to write to you from Lyon, my dear, friend, as I promised. You know how much I love that excellent city, where I was welcomed so warmly last year, and even more warmly this. I saw again the old Roman walls, defended in our day by the brave Lyonnais when the cannon-shot of the Convention forced our friend Fontanes to find another hearth for his daughter’s cradle. I saw the Abbey of the Two Lovers and Rousseau’s Fount. The hill-slopes along the Saône are more picturesque and delightful than ever, the little boats which sail that sweet river (the mitis Arar of Lucan: Pharsalia I) shrouded with canvas, lit at night by lamps, and piloted by young girls, delight the eye. You love the sound of bells: come to Lyon then; all the monasteries scattered about its hills seem to have regained their solitary inmates.

‘Lyons from Quayside on the Rhone’

James Duffield Harding, 1798 - 1863, British

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

You already know that the Academy of Lyon has done me the honour of admitting me among its members. Here is a confession: if cleverness has merit, don’t look to my pride for the virtue it possesses; you know you would even seek to view hell in its most favourable light. The greatest pleasure I have experienced in my life is that of being honoured, in France and abroad, with unexpected expressions of interest. Occasionally, while I was staying in some wretched village inn, I would find a father and mother enter with their son; they had brought their child, they said, to thank me. Was it self-love that granted me then the intense pleasure of which I speak? In what way could it flatter my vanity that these obscure though worthy people should testify to their gratification, beside the open road, in a place where no-one but I could hear them? What moved me, or at least I venture to think so, was to have done some good; to have solaced afflicted hearts; to have rekindled in the depth of a mother’s breast the hope of rearing a Christian son, in other words, a dutiful son, respectful, and devoted to his parents. I have no idea what value my work (The Spirit of Christianity: Le Génie du Christianisme) may possess; but would I have tasted such pure delight if I had written, with all imaginable skill, a book which struck a blow at morality or religion?

Convey to our little circle, my dear friend, how much I miss it. It has an inexpressible charm, because one feels that people who speak so naturally of everyday matters are capable of discussing the most elevated subjects, and that their simplicity of discourse is not due to poverty of thought, but a matter of choice.

I left Lyon, the other day, at five in the morning. I will not give you a eulogy on that city: its ruins are there; they speak to posterity; and while courage, loyalty, and religion, find honour amongst men, Lyon will never be forgotten. (It is very sweet to find, twenty-four years later, in a neglected manuscript, the expression of feelings that I, more than ever, profess for the people of Lyon; it is even sweeter to have recently received from them the same marks of esteem with which they honoured me nearly a quarter of a century ago.)

Our friends have made me promise to write to them en route; my progress, however, has been too swift, and I lacked the time to honour my word. I merely scribbled with a pencil, in a pocket-book, the journal I now send you. You will find in the Postal List, the names of unknown places I came across; such as Pont-de-Beauvoisin and Chambery; but you have so often repeated to me the necessity of taking notes, notes, at every opportunity, that our friends can have no reason for complaint if I have followed your advice.

Journal

The road is gloomy enough on quitting Lyon. From Tour-du-Pin as far as Pont-de-Beauvoisin the countryside is bleak hedged farmland. On the approaches to Savoy you see three mountain ranges almost parallel, rising one above the other. The plain at the foot of these mountains is watered by the little river Guiers. This plain seen from a distance seems flat; but from close to is found to be dotted with irregular hills, and you encounter woods, wheat-fields, and vineyards. The mountains in the background are verdant and mossy, or crowned with crystal-like rocks. The Guiers flows through so deep a channel one might term its bed a valley; indeed, the inner reaches are overshadowed by trees. I have only seen this before in certain American rivers, particularly around Niagara.

In one place, you rub shoulders closely with the river; the opposite bank of the stream is formed of a barrier of stones resembling a high Roman wall, similar to those of the arena at Nîmes. (I had not then seen the Coliseum.)

On reaching Échelles the country becomes wilder. You follow, in order to seek an egress, tortuous defiles among rocks variously horizontal, shelving, or perpendicular. Over these rocks hang masses of white cloud, like the morning mists that rise from the earth, over low ground. These clouds rise above or sink below the huge granite masses, so as to reveal the mountain tops, or fill the space between them and the sky. The whole forms a chaos whose indefinite boundaries seem to belong to no specific element.

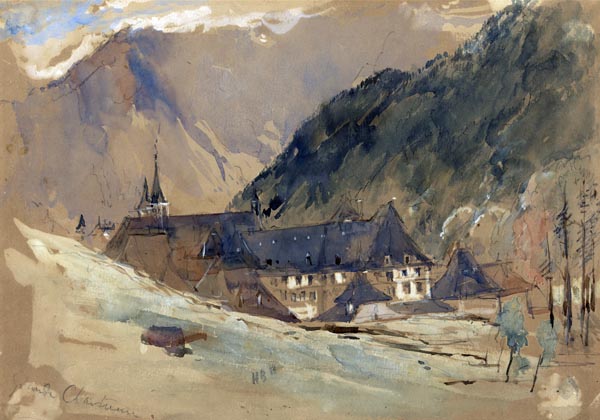

On the highest summit of these mountains is situated the Grande Chartreuse, the Carthusian monastery, while at their foot runs the road built by Charles Emmanuel II, Duke of Savoy (between 1667 and 1670). Religion dispenses its benefits from a point approaching Him who is in the heavens: the duke located his near to the dwellings of men.

‘Grande Chartreuse’

Hercules Brabazon Brabazon, 1821 - 1906, British

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

There was formerly an inscription here, announcing that Emmanuel, for the public good, had caused the hill to be cut through. During the revolutionary era, this inscription was effaced; Bonaparte had it restored; he merely added his name: if only he had always acted with similar nobility!

Formerly one penetrated the very heart of the rock, by a subterranean passage. This passage is now closed. I saw only tiny mountain birds, in this place, who float silently at the mouth of the cavern, like the dreams placed by Virgil at the entrance to hell: Foliisque sub omnibus haerent: clinging beneath every leaf (Aeneid VI:284).

Chambéry is situated in a hollow, whose elevated boundaries are quite bare: but you approach it through a charming defile, and leave by way of a lovely valley. The mountains which enclose this valley were partly clothed with snow. They revealed and hid themselves ceaselessly, under an ever-changing sky, formed of cloud and vapour.

It was at Chambéry that a man was welcomed by a woman, and as recompense for the hospitality he had received from her, the friendship she showed him, believed himself philosophically obliged to dishonour her. Either Jean Jacques Rousseau looked upon the conduct of Madame de Warens as a mere commonplace affair, and then, what becomes of the pretensions of our citizen of Geneva to virtue? Or he was of the opinion, that her conduct was reprehensible, and then sacrificed his memory of his benefactress to the vanity of writing a few eloquent pages; or perhaps Rousseau persuaded himself that his praise, and the charm of his style, might gloss over the sins he imputes to Madame de Warens, thus exhibiting the most odious species of self-love. Such is the danger of literature: the desire for fame sometimes overcomes noble and generous sentiments. Had Rousseau never become known, he would have buried in the valleys of Savoy the frailties of the woman who had cherished him, he would have sacrificed himself rather than expose his friend, he would have solaced her in her old age, instead of giving her a gold snuff-box, and then vanishing. But as all is now over for Rousseau, what can it matter to the author of the Confessions whether his dust is celebrated or unknown? Ah, may the echoes of friendship betrayed never be heard about my tomb!

The traces of history count for much in a traveller’s pleasure or disappointment. The Princes of the House of Savoy, adventurous and chivalrous, have closely wedded a memory of them to the mountains that adorned their little empire.

After Chambéry, the current of the Isére is worth viewing from the bridge of Montmélian. The Savoyards are agile, fairly well-built, of pale complexion, and regular figure; they share aspects of both the Italian and the Frenchman; and exhibit, like their valleys, an air of poverty short of outright destitution. Throughout their country, you come upon crosses erected beside the roads, and Madonnas carved from the trunks of pines and walnut-trees; indicating the devout nature of the people. Their little churches, enveloped in trees, form a touching contrast with their vast mountains. When the whirlwinds of winter descend from the summits, charged with eternal ice, the Savoyard finds sanctuary in his rural temple, and prays, beneath its thatched roof, to He who commands the elements.

The valleys one enters above Montmélian are bordered by heights of diverse form, sometimes half-denuded, sometimes clothed with forest. The bottoms of these valleys closely resemble, with regard to cultivation, the variations in terrain and the intricacies around Marly, conjoined there with more abundant streams and a river. The highway has less the air of a public road than of a path through a park. The walnut-trees with which this path is shadowed, reminded me of those we admired on our walks at Savigny. Will those trees find us together once more beneath their shade? (They have not found us so.)

The poet (Guillaume Amfrye de Chaulieu, writing of his birthplace Fontenay), in a melancholy moment, exclaimed:

‘Fair trees, that once saw my birth, Soon now you will see me die!’

Those who pass away beneath the shadow of the trees which witnessed their birth, have they any reason to lament?

The valleys I speak of terminate at a village bearing the pretty name of Aiguebelle. When I entered this village, the heights which overlook it were covered with snow: melting in the sun, it had descended with long crooked radials into the black and green cavities of the rock; you would have taken them for a firework spray, or a fine swarm of white snakes lancing from the summit of the mountains into the valley.

Aiguebelle seems quite close to the Alps: but soon, on turning past a large isolated rock that has tumbled into the road, you see new valleys which sink into the chain of hills that line the course of the River Arc. These valleys are of a more austere and savage character.

Mountains rise on both sides: their flanks soon become perpendicular; their sterile summits start to reveal glaciers; torrents, hurtling down from every direction, swell the Arc, which flows strongly. Amidst this tumult of waters I noticed a slight and noiseless cascade, which fell with infinite grace, screened by willows. Its moist drapery, shaken by the wind, might have seemed poetically the billowing robes of a Naiad, seated on a lofty precipice. The ancients would not have failed to dedicate an altar to the Nymphs in this spot.

Soon, the landscape took on its full grandeur: the forests of pine-trees, which up to that point had looked quite young, appeared much older; the road climbed, bending to and fro above the abyss: wooden bridges served to cross the gulfs, where you could see the water seething, and hear its roar.

Having passed Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne, arriving toward sunset at Saint-André I could obtain no horses, and was therefore obliged to stop. I went for a walk beyond the village. The air on the mountain summits cleared, their outlines traced with extraordinary clarity against the sky, while deep night slowly spread from the feet of the hills, and rose slowly toward their crests.

I heard the voice of the nightingale and the cry of an eagle; I saw the service-trees in flower along the valley, and snow on the heights: a castle, according to popular tradition the work of the Carthaginians, exhibited its ruins on a rocky crag. All the work of men’s hands in these regions is pitiful and transitory; sheepfolds, made of interwoven rushes; mud huts, built in a couple of days; as if the goatherd of Savoy, faced with the eternal masses that surround him, has not thought it worthwhile to trouble himself with the passing needs of his brief life! As if Hannibal’s ruined tower warns him of the transience and vanity of human effort!

Whilst contemplating this wilderness, I could not help admiring with awe, however, the hostility, more powerful than any obstacle, of that man who, from the Straits of Cadiz, forged a path over the Pyrenees and the Alps, to seek out the Romans! That the accounts handed down from antiquity do not tell us Hannibal’s exact route matters little: it is certain that this great general traversed the pathless heights, their inhabitants wilder even than the mountain streams, cliffs, and forests. I am told I shall gain a better understanding at Rome of that furious hatred, which the battles of the Trebia, Thrasimene, and Cannae, could not sate: I am assured that the walls of the Baths of Caracalla are scarred by the blows of pikes to the height of a man. Were not the hands of Germans, Gauls, Goths, Vandals, and Lombards raised against them? It was right that human vengeance should fall heavily on a people, themselves free, who founded their greatness only on the blood and slavery of others.

I left Saint-André at day-break, and arrived at about two in the afternoon at Lanslebourg, at the foot of Mont Cénis. On entering the village, I saw a peasant grasping a young eagle by its legs, whilst a pitiless mob aimed blows at that young monarch of the air, insulting the frailty of youth, and fallen majesty: the parent birds had both been killed. They offered to sell him to me; but he died of the ill treatment he had received, before I could free him. Is not this the very portrait of the little Louis XVII, his father, and mother?

Here you begin to ascend Mont Cénis (they were working on the road; it was not yet finished, and they were completing it); leaving behind the little river Arc, which leads you to the foot of the mountain: on the other side of Mont Cénis, the River Doria, Doria Riparia, opens the gate of Italy to you. I have often had occasion, in the course of my travels, to observe the usefulness of rivers. Not only are they (as Pascal says) great high roads which themselves travel onwards, but they point the way to men, and facilitate our passage of the mountains. In coasting by their banks, nations were discovered; and the first inhabitants of earth penetrated the wilderness, with the aid of their currents. The Greeks and Romans offered sacrifices to the rivers, which the myths make the offspring of Neptune, because they are formed from the Ocean vapours, and lead to the discovery of lakes and seas; wandering children who return to the paternal bosom and the grave.

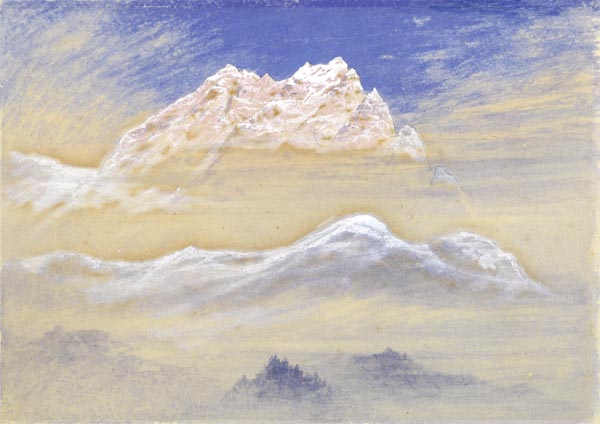

Mont Cénis on the French side is unremarkable. The lake on the plateau seemed to me no more than a pond. I was disagreeably surprised, at the beginning of the descent toward Novalesa: I expected, I know not why, to view the plains of Italy; I only saw a deep black abyss; a chaos of torrents and precipices.

In general, the Alps, though higher than the mountains of North America, do not strike me as possessing that original character, that purity of aspect, you observe in the Appalachians, or even the elevated regions of Canada: the hut of a Seminole under a magnolia, or of a Chippewa under a pine, has a wholly different character to the cabin of a Savoyard under a walnut-tree.

‘Portion of the Chain of the Terglon Alps as seen from near Rudmannsdorf, Italy’

Elijah Walton, 1832 - 1880

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Second Letter to Monsieur Joubert

Milan, Monday Morning, the 21st June, 1803.

My dear friend, I always begin my letter, without knowing when I shall have time to finish it. My total apologies to Italy! You will have seen, from my little journal, postmarked Turin, that I was not very impressed at first sight of her. The appearance of the neighbourhood of Turin is fine; but is still feels like France; one might fancy oneself in some Normandy close to mountains. Turin is a new city, clean, orderly, well-adorned with palaces, but possessing rather a sad aspect.

My opinions changed while crossing Lombardy. This result, however, is only produced in the traveller by degrees. You find, at first, countryside of great richness everywhere, and you say: ‘This is pleasant’, it is only when you start to consider the details that enchantment arrives. Meadows, whose greenness exceeds the freshness and delicacy of English turf, are mingled with fields of maize, rice, and wheat, surmounted by vines spreading from one prop to another, forming garlands above the corn; the whole studded with mulberry-trees, walnuts, young elms, willows, and poplars, and watered by rivers and canals. Scattered over the landscape, may be seen the country-men and women, bare-footed, large straw hats on their heads, singing as they mow the fields or reap the corn, or drive teams of oxen, or steer their boats upstream and downstream. This scene continues for forty leagues, increasing in richness as you approach Milan, the centre of the portrait. On the right you can see the Apennines; on the left the Alps.

You travel swiftly; the roads are excellent; the inns superior to those of France, and almost equal to those of England. I really begin to think that same France, well-ordered as it is, somewhat barbarous. (One must remember that this letter was written in 1803. If travelling was so convenient in Italy then, when it was merely a military outpost of France; how much easier to traverse that beautiful country today, in a time of profound peace, and with a plethora of new roads open? We are summoned there by our every wish! The Frenchman is a strange enemy: he is at first found to be somewhat insolent, cheerful, active, and far too restless; but he has no sooner left than he is regretted. The French soldier shares the work of the host under whose roof he lodges: his good-humour gives life and interest to every thing; at length he is seen as a sort of conscript belonging to the family. As for the roads and inns of France, they are far worse now than in 1803. In truth, we are in this respect, behind all the other countries of Europe, Spain excepted.)

I am no longer surprised at the contempt which the Italians have always entertained for us trans-Alpine peoples; Visigoths, Gauls, Germans, Scandinavians, Slavs, Anglo-Normans; our leaden skies, smoky cities, and muddy villages, must fill them with horror! The towns and villages here have quite another aspect; the houses are large, with exteriors of brilliant white; the streets are wide and frequently intersected by streams of running water, in which the women wash their clothes and bathe their children. Turin and Milan possess the regularity and cleanliness of London streets, with the architecture of the best quarters of Paris. They even own to a special refinement; in the middle of the streets (so that the movement of the carriage may be smoother) they set two rows of flat stones, over which the wheels run; so you escape the unevenness of the ground.

The temperature is delightful, though they tell me I will not experience the true Italian climate until I have passed the Apennines: the height and size of the apartments prevents ones suffering from the heat.

June the 23rd.

I have seen Murat: he received me with kindness and courtesy; and I have handed him a letter from the excellent Madame Bacchiochi (later Princess of Lucca, eldest sister to Buonaparte, who, at that time, was only First Consul); I have passed the day amongst aides-du-camp and young officers; no one could be more courteous. The French army is ever the same; always honourable.

I dined in great style with Monsieur de Melzi; he was involved in holding a fête on the occasion of the baptism of Murat’s child. Monsieur de Melzi knew my unfortunate brother, of whom we talked a while together. The Vice-President is a man of very dignified manners: his mansion is that of a prince, and of one who has always held that rank. His treatment of me has been cool but very polite, and he found me of an exactly similar disposition. I say nothing, my dear friend, of the works of art in Milan, and above all, of the cathedral (which they are completing). The Gothic style, even its marble, seems out of sympathy with the sun and the manners of Italy. I leave this instant; I will write to you from Florence (my letters from Florence cannot be found); and Rome.

Third Letter to Monsieur Joubert

On arrival at Rome, the evening of the 27th June, 1803.

Here I am at last! All my reservations have vanished. I am overwhelmed, haunted, by what I have encountered; I have seen, I believe, what no one else has seen; certainly what no other traveller has attempted to describe: those idiots; glacial spirits; barbarians! When they arrive here, have they too not traversed Tuscany; that English garden, in whose midst a temple rises; that is to say, Florence? Have they too not passed, in company with eagles and wild boars, the wilds of this second Italy, called the Roman States? Why do such people travel at all? Arriving as the sun was setting I found the whole population about to take their walk in the Arabia Deserta at the gates of Rome. What a city! What memories!

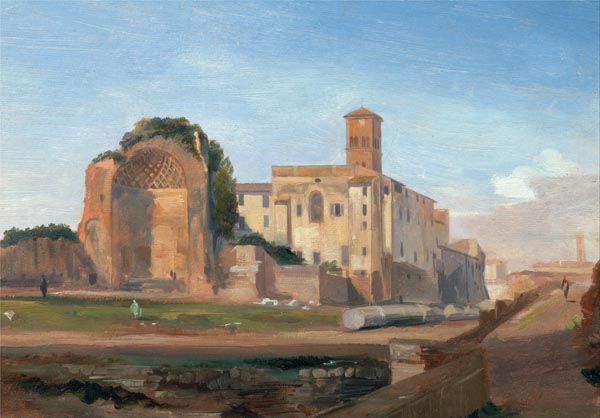

‘Modern Rome - Campo Vaccino’

Joseph Mallord William Turner (British, 1775 - 1851)

Getty Open Content Program

June the 28th, 11 pm.

I have been running about all this day, which is the eve of the festival of St. Peter. I have already seen the Coliseum, the Pantheon, Trajan’s Pillar, the Castle of St. Angelo, and St. Peter’s: and who knows what else? I saw the illuminations and fireworks which herald the grand ceremony tomorrow, dedicated to that Prince of Apostles. While I pretended to be admiring a light set on top of the Vatican, I was actually watching the effect of the moon on the Tiber, the Roman mansions, and the ruins, which are scattered about on every side.

‘A View of Trajan's Forum, Rome’

Charles Lock Eastlake (1793 - 1865), British

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

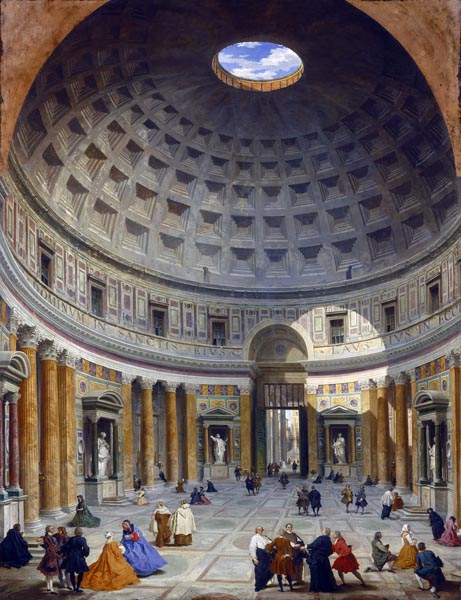

‘Interior of the Pantheon, Rome’

Giovanni Paolo Panini, Italian, 1691 - 1765

NGA Open Access

June the 29th.

I have just come from divine service at St. Peter’s. The Pope has a wonderful face; pale, sad, devout, all the tribulations of the Church seem written on his brow. The ceremony was superb; and at certain times, especially, overwhelming; but the singing mediocre, the church deserted; nobody there!

‘Interior of Saint Peter's, Rome’

Giovanni Paolo Panini, Italian, 1691 - 1765

NGA Open Access

July the 3rd, 1803.

I really do not know whether all these scraps of writing constitute a letter. I would be ashamed, my dear friend, of telling you so little did I not wish, before trying to describe things, to see them more clearly. Sadly, I find that modern Rome is already vanishing in its turn: everything comes to an end!

His Holiness received me yesterday. He made me sit down beside him in the most affecting manner, and told me, in an obliging way, that he had read Le Génie du Christianisme, a volume of which, indeed, lay open on his table. There cannot be a better man, a more worthy prelate, or a more unaffected prince; do not mistake me for Madame de Sévigné. The Secretary of State, Cardinal Consalvi, is a man of great wit and temperate character. Adieu! I must, after all, commit these scraps to the post.

Tivoli, and Hadrian’s Villa

December the 10th, 1803.

I am perhaps the first foreigner who has made an excursion to Tivoli in a frame of mind little suited to sightseeing. Witness my arrival alone at seven in the evening, on the 10th of December, at the Temple of the Sybil inn. I occupy a little room at the extremity of the house, facing the waterfall, whose roar I hear. I tried to take a look at it, but was only able to distinguish, in the depths of darkness, several glimmers of white produced by the movement of the water. It seemed to me that I perceived in the distance an enclosure formed of trees and houses and about this enclosure a ring of mountains. I do not know what alteration the daylight will make to this nocturnal landscape.

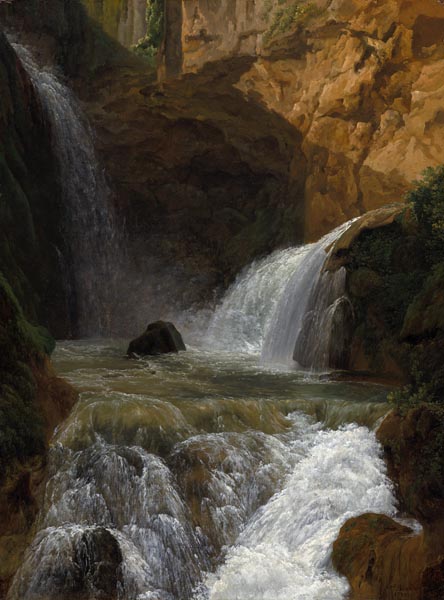

‘View of the Waterfalls at Tivoli’

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld (French, 1758 - 1846)

NGA Open Access

The place is suited to reflection and reverie. I recall my past life; I feel the weight of the present, and seek to penetrate the future. Where shall I be; what shall I be doing; who shall I be, twenty years hence? Whenever we reflect deeply on the future, a giant obstacle looms, opposing all the vague projects we conceive; an uncertainty caused by a certainty; that obstacle, that uncertainty is death, dreadful death that halts all, felling ourselves or others.

Are they friends you have lost? You have a thousand things to say to them, in vain: unhappy, isolated, a wanderer on this earth, with no one to whom you can confide pain or pleasure, you summon your friends, yet they can no longer appear, to ease your cares or share your joys! They can no longer tell you whether you were wrong, or right, in acting as you have. Now you must journey alone. What value is there in being rich, powerful, or famous? What use has prosperity without a friend? One thing has destroyed all; death! You waves, leaping into that profound darkness from which I hear your roar emerge, are you vanishing more swiftly than the days of man, or can you tell me what man is; you, who have seen so many generations pass by your banks?

December the 11th.

As soon as daylight appeared, I opened my windows. My first impression of Tivoli in the darkness was fairly accurate; though the waterfall looked tiny, and the trees which I thought I had seen, did not exist. A cluster of wretched houses occupied the far bank of the river; the whole was surrounded by bare mountains. However, a bright dawn behind the mountains, and the Temple of Vesta four paces from me, overlooking the grotto of Neptune, consoled me. Immediately above the fall, a herd of oxen, horses and asses were ranged along a sandbank: all these beasts had taken a step into the Teverone (Aniene), and with bowed necks were drinking, in a leisurely manner, from the water which passed before them like lightning, before vanishing over the fall. A Sabine peasant, clothed in a goat-skin, and wearing a kind of mantle rolled back over his left arm, leaned on his staff, and watched his charges drinking; a scene contrasting, in its silence and immobility, with the sound and movement of the waters.

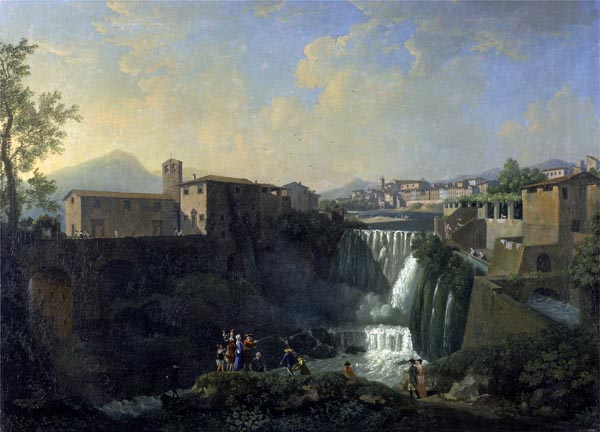

‘A View of Tivoli’

Thomas Patch, 1725 - 1782, British

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

My breakfast ended, they brought me a guide in whose company I was to cross the bridge over the cascade (I had previously seen the Niagara Falls). From the bridge over the cascade we descended to the Cave of Neptune, so named, I believe, by Claude Vernet. The Anio, after the first waterfall below the bridge, plunges among rocks and reappears in this Cave of Neptune, in order to descend a second fall to the Cave of the Sirens.

The basin in the Cave of Neptune has the form of a chalice, and I have seen doves drinking at it. A dove-house excavated in the rock, but resembling an eagle’s eyrie rather than a shelter for doves, offers these poor birds illusory refuge; they think themselves perfectly safe in that seemingly inaccessible spot, they build their nests there; but a secret passage leads to it: during the hours of darkness, some raptor snatches away the chicks, which sleep without fear to the sound of the waters, from under their mothers wing. Observans nido implumes detraxit: on seeing them, snatched them featherless from the nest. (Virgil: Georgics IV, 513)

‘The Grotto of Neptune in Tivoli’

Johann Martin von Rohden (Germany, Kassel, 1778 - 1868)

LACMA Collections

Returning from the grotto of Neptune to Tivoli, and taking the Angelo Gate, the gate to the Abruzzo region, my guide led me towards the country of the Sabines; pubemque sabellum, and the Sabine race (Virgil Georgics II:167) I walked downstream along the Anio as far as a field of olives, where a picturesque view of this celebrated wilderness opens. At a glance, you could see the Temple of Vesta; the Caves of Neptune and that of the Sirens; and the little cascades that emerge from one of the porticoes of the Villa of Maecenas. A bluish vapour spread over the landscape, softening its outlines.

You gain some idea of the grandeur of Roman architecture when you consider that these structures, raised so many ages ago, have passed from the service of man to that of the elements; that they sustain today the weight and motion of a mass of waters, and have become the immoveable rocks above these tumultuous falls.

My walk lasted six hours; at the end of it I re-entered my inn, situated in a dilapidated court, to the walls of which memorial stones were fixed, covered with mutilated inscriptions. I have transcribed some of these:

DIS. MAN.

ULLAE PAULIN

VIXIT ANN. X.

MENSIBUS DIEB. 3.

SEI. DEUS.

SEI. DEA.

D. M.

VICTORIAE.

FILIAE QUAE.

VIXIT.ANN. XV

PEREGRINA,

MATER. B. M. F.

D. M.

LICINIA

ASELERIO

TENIS.

What could possibly prove more futile than all this? I read upon a block of stone the expressions of regret that some living person bestowed on the dead; the survivor has perished in turn and I, a barbarous Gaul, arrive two thousand years later, and surrounded by the ruins of Rome pore over these epitaphs in their secluded retreat; I, as indifferent to the mourner as to the mourned; I, who to-morrow will leave this place forever, and vanish, shortly, from the earth!

All the Latin poets who visited Tibur (Tivoli) wept on considering the brevity of life. Carpe diem: seize the day, cried Horace (Odes I:11); Te spectem suprema mihi cum venerit hora: Let me gaze on you, when my last hour has come: exclaimed Tibullus (I.1:59). Virgil (Georgics IV:494) depicts the last hour so: Invalidasque tibi tendens, heu! non tua palmas: stretching out to you, alas, hands no longer yours. Who has not lost some object of his affections? Who has not seen helpless arms extended toward him? A dying man has often wanted his friend to grasp his hand, as if doing so might win him to life, at the very moment when he feels death dragging him down. Heu! non tua!: alas, no longer yours! That exclamation of Virgil’s is admirable in its tenderness and sorrow. Woe to him that loves not the poets! I would almost say of such individuals what Shakespeare says of men insensible to music (The Merchant of Venice Act V Scene 1, 83-85).

Returning to my room, I found again the solitude I had left outside. The little terrace, belonging to the inn led to the Temple of Vesta. Painters know that patina of the centuries that time applies to old monuments, which varies with climate: it is there in the Temple of Vesta. You can make the circuit of the little building between the peristyle and the cella, in sixty paces. The true Temple of the Sybil is distinguished from this one by its square shape and the severe style of its architecture. When the falls of the Anio were located a little more to the right, as is assumed, the temple must have been suspended immediately above their cascade; the place was a perfect setting for the priestess’s inspired utterances, and the religious enthusiasm of the crowd.

I cast a last glance on the northern peaks, which the mists of evening had covered with a white veil, on the valley to the south, and on the entire landscape, and returned to my solitary room. At one in the morning, the wind blowing most violently, I rose, and spent the rest of the night on the terrace. The sky was filled with clouds: the wind, among the columns of the temple, added its moan to the noise of the falls: you might have thought you were hearing sad voices from the vents of the Sybil’s cave. The spray of the waterfall climbed back towards me from the depth of the abyss like a white ghost: it was indeed a genuine apparition! I imagined myself transported to the shores or heaths of my native Armorica (Brittany), amidst an autumn night; the memories of my paternal roof replaced those of the dwellings of the Caesars: everyone bears within themselves a little world composed of all they have seen and loved, to whose sanctuary they constantly retreat, even when traversing, and seeming to inhabit, an alien world.

In a few hours time, I am off to visit Hadrian’s Villa.

December the 12th.

The grand entrance to Hadrian’s Villa was through the hippodrome, on the ancient Via Tiburtina, and not far from the Tomb of the Plautii. There remain no vestiges of antiquity within the hippodrome, converted into a vineyard.

‘Hadrian's Villa’

Richard Wilson RA, 1714 - 1782, British, active in Italy (1750 - 1756)

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

On exiting a narrow side-road, an avenue of pollarded cypresses led to a wretched farm-house, whose crumbling staircase was filled with sundry pieces of porphyry, verd-antique, granite, white marble rosettes, and various architectural ornaments. Behind this farm is the Roman theatre, in a fairly good state of preservation; a semicircle composed of three rows of seats. The base of this semicircle is a straight wall, which serves as diameter: the orchestra and the stage faced the Emperor’s box.

The son of the farmer’s wife, a little lad about twelve years old, almost naked, pointed out this box, and the dressing-rooms of the actors. Underneath the benches intended for the spectators, in a place where the farm-labourers now deposit the implements of their husbandry, I found the torso of a colossal Hercules, buried amidst ploughshares, harrows, and rakes: empires are born of the plough, and vanish beneath it.

The interior of the theatre serves as the farmyard and garden; it is planted with plum and pear-trees. The well that has been excavated in its centre, is adorned with two pillars, to which the buckets are attached; one of the pillars is made of dried earth and stones heaped together at random; the other from the lovely shaft of some fluted column: but, to erase the magnificence of this latter and assimilate it to the rusticity of the former, nature has draped it with a mantle of ivy. A herd of black pigs were raking and turning up the turf that covered the benches of the theatre. In order to overthrow the seats of the masters of the earth, Providence needed only to sow a few roots of fennel between the joints, and to deliver over that ancient enclosure’s Roman elegance to the unclean swine of loyal Eumaeus.

From the theatre, ascending by way of the farm’s staircase, I reached Palestrina (Praeneste), strewn with sundry ruins. The vaulted ceiling of a hall exhibited ornamentation in exquisite taste.

From here the valley starts, which Hadrian named the Vale of Tempe.

Est nemus Haemoniae, praerupta quod undique claudit silva. There is a grove in Haemonia, closed in on every side by wooded cliffs. (Ovid:Metamorphoses I:568-569)

At Stowe, in England, I have seen, a replica of this imperial fantasy: but Hadrian had laid out his English garden as became a man who possessed the world.

At the end of a little wood of green elms and oaks, you see ruins stretching the whole length of this Vale of Tempe; double and triple porticoes, which served to sustain the terraces of Hadrian’s creation. The vale extends farther than the eye can reach, toward the south; its floor is planted with reeds, olive-trees, and cypresses. The hill to the west, representing the ridge of Olympus, is adorned by the mass of Palace, Library, and Hospices, the Temples of Hercules and Jupiter, and the long arcades, festooned with ivy, that support these structures. A parallel, but lower height, borders the valley to the east; behind this hill rises the amphitheatre of mountains above Tivoli, which would have represented Ossa.

In a field of olive-trees, an angle of the wall of the Villa of Brutus forms a companion to the ruins of the Villa of Caesar. Liberty rests in peace beside despotism: the dagger of one and the axe of the other are now nothing more than rusty iron buried beneath the same rubble.

From the immense building which, according to tradition, was dedicated to receiving visitors, crossing rooms open on all sides, you arrive at the library. Here a maze of ruins begins, interspersed with young coppices; clumps of pine; and patches of olive-trees, diversely planted, that delight the eye and sadden the heart.

A fragment, suddenly detached from the vaulted roof of the library, fell at my feet, as I passed by: a little dust was raised, and several plants were broken and dragged down in its fall. The seeds of these plants will thrive again to-morrow; the noise and dust vanished on the instant: behold this new ruin, destined to lie for centuries near those which seemed to await it! Empires likewise plunge into eternity, where they rest in silence. Men are not unlike these ruins that tumble, one after another, to earth: the only differences among them, as among these ruins, is, that some fall in the presence of spectators, while others sink without witness.

I passed from the Library to the Circus of the Lyceum: they had just been cutting the bushes for firewood. This Circus adjoins the Temple of the Stoics. In the passage leading to it, glancing behind me, I could see the towering but dilapidated walls of the Library, which dominate the lower ones of the Circus. The former, half-hidden in the upper branches of wild olive-trees, were themselves overtopped by an enormous umbrella-pine; and above this rose the ultimate crest of Mount Calvo, capped with cloud. Never were heaven and earth, the works of nature and those of man, better wedded in a single picture.

The Temple of the Stoics (the Philosopher’s Hall) is not far from the Parade Ground. Through the opening of a portico as if through a telescope, you see, at the extremity of an avenue of olives and cypresses, Mount Palomba, crowned by the first Sabine village. On the left of the Pecile, and beneath the Pecile itself, the visitor descends into the Cento-Cellae (The Hundred Chambers) of the Praetorian Guard: these are vaulted chambers about eight feet square, of two, three, or four stories, having no communication with each other: light being admitted through their doorways. A moat runs the whole length of these cells, used for military purposes, which were most probably entered by means of a drawbridge. When the hundred bridges were let down, when the Praetorians passed, back and forth, over them, it must have formed a singular spectacle to adorn the gardens of the philosopher-Emperor who added another god to Olympus. These days, farm-workers, under the patrimony of St. Peter, come to dry their grain in the barracks of the Roman legionaries. When the imperial nation and its masters erected all those fine buildings, they little thought they were building cellars and granaries for a Sabine goatherd, or a farmer of Albano.

After exploring a portion of the Hundred Chambers, I still had time to visit that part of the gardens attached to the Thermae, the women’s baths: there, I was overtaken by rain. (See the letter which follows, regarding Rome, to Monsieur de Fontanes.)

When standing amidst Roman ruins, there are two questions I have often asked myself: the houses of private men were composed of a multitude of porticoes, vaulted chambers, chapels, halls, subterranean galleries, and dark secret passages: what was the use of all this display to an individual owner? Rooms for the slaves, guests, and dependents, generally appear to have been built apart.

In resolving this first question, I imagine the Roman citizen, at home, to have been a sort of monk, who erected cloisters for his private use. Perhaps that reclusive life, indicated only by the form of the buildings, may be a cause of the calmness we remark in the writings of the ancients? Cicero found, once more, in the long galleries of his dwelling, in the domestic temples it enclosed, that tranquillity he had lost in his commerce with men. Even the light which entered these rooms would seem to lend itself to quietude: it almost always fell from above, or from high windows: this perpendicular light, so uniform and tranquil, with which we illume our art-galleries, served the Romans, if you will allow the metaphor, to illuminate their meditations on the portrait of life. As for us, we must have windows open to the street, the market-place, the crossroad. Every thing that agitates or makes a noise delights us: contemplation, seriousness, silence fill us with ennui.

‘Market Scene in Rome, Piazza Navonna’

Manner of Michael Sweerts, 1650 - 1680

The Rijksmuseum

The second question which has always concerned me is this: why were so many edifices dedicated to the same uses? One sees endless halls dedicated to libraries; yet there were few books among the ancients. We find Thermae (Baths) at every step: the Baths of Nero, Titus, Caracalla, Diocletian, etc. Even had Rome been three times as populous as it ever has been, a tenth of these baths would have been sufficient for public use.

I answer that these monuments were probably abandoned and in a state of ruin, almost from the very moment of their erection. One emperor overturned or despoiled the works of his predecessors, with a view to undertaking similar ones himself, and these were, in turn, swiftly abandoned by his successor. The blood and sweat of the people were exhausted on useless works generated by individual vanity, till that moment when the world’s redeemers issued from the depths of the forests to plant the humble standard of the cross on these monuments to pride.

The rain having ceased, I visited the Garden Stadium; examined the temple of Diana, in front of which stands that of Venus; and penetrated amongst the rubble of the Emperor’s palace. The best preserved part of this formless ruin is a sort of cellar or cistern, of square shape, under the courtyard of the palace itself. The walls of this subterranean area are double, each wall two and a half feet deep, the space which separates them being about two inches.

‘Temple of Venus and Rome, Rome’

Edward Lear (1812 - 1888), British

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Emerging, and leaving the palace behind me on the left, I walked to the right, toward the Roman Campagna. Passing over a field of corn, sown above underground vaults, I arrived at the Thermae (Baths), as yet still called halls of the philosophers, or Praetorian barracks; these are some of the most imposing ruins within the entire Villa. The beauty, height, strength, and lightness of the arches, the various inter-lacings of the porticoes which cross, intersect, or run parallel to the building, the landscape that adorns the background of this fragment of great architecture, produce an astounding impression. Hadrian’s Villa has furnished several precious remnants of the art of painting: the few arabesques that I have seen are of very skilful design, and the drawing is equally pure and delicate.

The Naumachia, situated behind the Thermae, is a basin excavated by human hands, into which enormous pipes, still visible, conducted the water. This basin, now dry, was then full, and hosted mock naval battles. It is well known, that, at these entertainments, one or two thousand men were often slaughtered for the amusement of the populace.

Around the Naumachia, terraces were built for the spectators; these terraces were supported by porticoes, which served as construction sites or shelter for the galleys.

A temple, imitating that of Serapis, in Egypt, adorned this scene: one half of the great dome (the Canopus) of this temple has fallen. At the sight of its sombre pillars, concentric arches, and a sort of cavity, from which the Oracle murmured, you would think you were no longer amongst the works of Italy or Greece, but that the genius of some other people had presided over this monument. An old sanctuary exhibits a few marks on its green and humid walls. I know not what plaints stray through that abandoned edifice.

I gained the temple of Pluto and Proserpine, commonly termed the Entrance to Hell. The temple is now the home of a vine-dresser; I could not therefore explore it; the owner, like the god, being absent. Below the Entrance to Hell, runs a valley known as the Vale of the Palace: you might take it for the Elysian Fields. Advancing south, and following a wall which supported the terraces attached to the Temple of Pluto, I saw the furthest fragments of the Villa, more than a league away.

Retracing my steps, I wanted to see the Academy, consisting of a garden, a Temple of Apollo, and various buildings intended for the use of the philosophers. A farm-worker opened a gate leading into the field of some other proprietor, and I found myself at the Odéon and the Greek Theatre; quite well preserved in form. Some melodious spirit must surely still haunt this spot dedicated to harmony; since I heard the notes of a blackbird, on the 12th of December: a troop of children, gathering olives, made the place echo with their songs; echoes which perhaps had once repeated the verse of Sophocles and the music of Timotheus.

Here my survey ended; a much longer one than is generally made: I owed as much to that Imperial traveller. Further on you can see the grand Portico, of which little remains; and still further, the relics of some other buildings, of unknown purpose: finally, the Colle di San Stephano, where the grounds of the Villa terminate, and on which stand the ruins of the Prytaneum.

From the Hippodrome to the Prytaneum, the Villa of Hadrian occupies the sites at present known as Roccabruna, Palazza, Aqua Fera, and Colle di San Stephano.

Hadrian was a remarkable prince, though not one of the greatest of the Roman emperors; yet he is one of those whose names we best remember today. He has left traces every where; including Hadrian’s Wall in Great Britain; the arena at Nîmes and the Pont du Gard, it may be, in France; temples in Egypt; aqueducts at Troy; new areas of the cities of Jerusalem and Athens; in Rome itself a bridge which is still in use, and a host of other monuments, attesting to his taste, activity, and power. He was himself poet, painter, and architect. His age was that of a restoration of the arts.

‘Castel Sant'Angelo, Rome’

John Inigo Richards RA, 1730/31? - 1810, British

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

The fate of Hadrian’s Tomb (Castel Sant’Angelo, in Rome) is singular. The ornaments of this sepulchre served as weapons against the Goths. Civilization hurled columns and statues at the head of Barbarism, whose entrance, however, it could not prevent. The mausoleum became a fortress of the Popes, and was converted into a prison; which scarcely belies its original intent. These vast edifices erected over the ashes of men fail to increase the dimensions of the grave! The dead, in their sepulchral houses, are like the statue seated in that over-small Temple of Hadrian’s; if they wished to rise, they would strike their heads against the ceiling.

‘Fanciful View of the Castel Sant'Angelo, Rome’

Francesco Guardi, Italian, 1712 - 1793

NGA Open Access

Hadrian, on mounting the throne, said loudly to one of his enemies: ‘Behold, you are spared!’ The statement was magnanimous. But we fail to extend the same clemency to genius that we extend to political opponents. The jealous emperor, on seeing the master-works of Apollodorus, said quietly to himself: ‘Behold, he is lost!’ and the artist was slain.

I could not leave Hadrian’s Villa without first filling my pockets with little bits of porphyry, alabaster, verd-antique, painted stucco, and mosaic work; I have since thrown them away.

Now, these ruins exist for me no longer, since it is not likely that I shall be led again to the spot. Every instant you mourn, some moment, some thing, some person, you will never see again: life is continual death. Many travellers who preceded me inscribed their names on the marble of Hadrian’s Villa: they hoped to prolong their existence by attaching to a famous place a token of their visit: they were deceived! As I attempted to read one of these names, newly traced in pencil, a name which I thought I recognized, a bird flew from a clump of ivy; it shook down a few drops of the recent rain; the name vanished.

To-morrow, to the Villa d’Este. (See the letter below regarding Rome.)

The Vatican

December 22nd, 1802.

I visited the Vatican at one o’clock; a fine day, brilliant sun; the air extremely mild.

Solitude reigns over the vast flights of steps, or rather terraces that you could ascend with mules; solitude reigns over the galleries adorned with the master-pieces of genius, which in other days the Popes, in all their pride, traversed; solitude reigns over the works which so many celebrated artists have studied, so many illustrious men admired; Tasso, Ariosto, Montaigne, Milton, Montesquieu, kings and queens, powerful or fallen, and hosts of pilgrims from every quarter of the globe.

‘St. Peter's, the Basilica and the Piazza’

Francesco Panini (Italy, 1745 - 1812)

LACMA Collections

God dispelling Chaos.

I noted the angel that followed Lot and his wife.

A beautiful view of Frascati, over the roofs of Rome, from a corner or angle of the gallery.

The entrance to the Halls. — The Battle of Constantine; the tyrant and his horse drowning.

St. Leo halting Attila. Why has Raphael given a fierce instead of a religious air to the group of Christians? In order to express a feeling of divine aid.

The Holy Sacrament, Raphael’s first work; cold, and inexpressive of piety, but the disposition of the figures and the figures themselves admirable.

Apollo, the Muses, and the Poets. — The character of the poets very well expressed; but the whole presents a strange medley.

Heliodorus chased from the Temple. — A notable angel, a celestial female, imitated by Girodet, in his Ossian.

The Burning of a Town. — The woman bearing a vase: copied endlessly. The contrast between the man stupefied with fright and one who is trying to reach a child. The art too apparent. The mother and infant painted by Raphael a thousand times, and always excellently.

The School of Athens: I like the Cartoon quite as much.

The Deliverance of St. Peter. — The effect of the three lights quoted everywhere.

The Library: an iron gate bristling with spikes: truly the gate of science. The arms of one of the Popes — three bees — a happy symbol.

A magnificent Nave: the books invisible. Were they exhibited, one might here find materials capable of wholly reconstituting modern history.

The Christian Museum. — Instruments of martyrdom: iron claws to tear at the skin; a scraper to remove it; iron hammers; small pincers: what fine Christian antiquities! How did men suffer in the past? Just as at present — witness these instruments. In matters of suffering, the human race is stuck fast.

Lamps found in the Catacombs. — Christianity begins at the grave; from a funeral lamp that torch was kindled which lights the world. — Ancient crosses, ancient chalices, ancient implements, with which to administer communion. — Paintings brought from Greece, to preserve them from the Iconoclasts.

An ancient depiction of Jesus Christ, since reproduced by the painters; it can scarcely be older than the eighth century. Was Christ the most handsome of men, or was he ugly? The Greek and Latin fathers are divided in their opinion: I incline to the former view.

A Donation to the Church on papyrus: — the world recommences here.

The Museum of Antiquities. — A female head of hair found in a tomb. — Is it that of the mother of the Gracchi? — Is it that of Delia, Cynthia, Lalage, or Lycimnia (Terentia), of whose hair Maecenas, if we may believe Horace (Odes II.12), would not exchange a single strand for all the wealth of a Phrygian king?

Aut pinguis Phrygiae Mygdonias opes permutare velis crine Lycimniae? Would you exchange one strand of Lycimnia’s for the Mygdonian wealth of fertile Phrygia?

If anything embodies the idea of fragility, it is the hair of a young girl, which might have been an object of idolatry to that most fleeting of passions, and yet has survived the Roman Empire! Death, which breaks all chains, has not shattered this frail reed.

A beautiful twisted column of alabaster. — A winding-sheet of green fibrous chrysolite, recovered from a sarcophagus. Death, however, has nonetheless consumed his prey.

An Etruscan chalice. Who drank from this cup? One of the dead! Everything in this Museum is a treasure from the grave, whether it was used in the funeral rites, or appertained to the living.

The Capitoline Museum

December the 23rd, 1803.

A columnar Mile-Stone. — In the Courtyard, the feet and head of a Colossus: intentionally created so?

In the Senate-House; the names of modern senators; a She-Wolf struck by lightning; the geese on the Capitol.

Là sont les devanciers avec leurs descendants;

Tous les règnes y sont; on y voit tous les temps;

There are the forefathers with their descendants.

All reigns are there: one views there all the ages; (Père Le Moine: Saint Louis)

Ancient measures of corn, oil, and wine, in the shape of altars, with the heads of lions.

Paintings representing the most important events of the Roman Republic.

A statue of Virgil: the countenance is countrified but grave, the brow melancholy, the eyes animated; and there are lines diverging from the nostrils and terminating at the chin, furrowing each cheek.

Cicero: a certain regularity, with an expression of lightness; less force of character than philosophy; as much wit as eloquence.

The Alcibiades did not strike me with its beauty: something of the clown and the fool.

A young Mithridates, resembling an Alexander.

Consular regalia, both ancient and modern.

The Sarcophagus of Alexander Severus and his mother.

A bas-relief of the infant Jupiter on the Island of Crete: admirable.

A column of oriental alabaster, the most beautiful known to be extant.

An antique plan of Rome, in marble; the perpetuity of the Eternal City.

A bust of Aristotle: something intelligent and forceful there.

A bust of Caracalla: the eyes tense, the nose and mouth pointed; a wild and fierce expression.

A bust of Domitian: the lips pursed.

A bust of Nero: the visage large and round, sunken about the eyes, so that both forehead and chin project: the air of a debauched Greek slave.

Busts of Agrippina and Germanicus: the second long and thin; the first grave. A bust of Julian: the forehead small and narrow.

A bust of Marcus Aurelius: a broad brow, the eyes and the eyebrows lifted toward Heaven.

A bust of Vitellius: a large nose, thin lips, puffed cheeks, small eyes, and the head bent forwards a little, like that of a pig.

A bust of Caesar: the face thin; deeply furrowed; a prodigiously intellectual expression; the forehead very prominent between the eyes, as if the skin were puckered and intersected by a perpendicular wrinkle; the eyebrows low and touching the eyes; the mouth large, and singularly expressive; one might think it about to speak, it almost smiles; the nose prominent, but not as aquiline as it is usually represented; the temples flattened like those of Buonaparte; scarcely any dimension to the back of the head; the chin round and double; the nostrils a little contracted; a figure of imagination and genius.

A bas-relief: Endymion asleep, seated on a rock; his head bent to his chest, and leaning slightly towards the shaft of his spear, which rests upon his left shoulder; the left hand, resting carelessly on his spear, holds the lead of his dog, loosely, while the creature standing on its hind legs, endeavours to look over the rock. This is perhaps one of the most exquisite bas-reliefs in existence. (I made use of this pose in Les Martyrs).

From the windows of the Capitol, one can see the whole Forum, the Temples of Fortune and Concord, the two columns of the Temple of Jupiter Stator, the Rostra, the Temple of Faustina, the Temple of the Sun, the Temple of Peace, the ruins of Nero’s Golden Palace, those of the Coliseum, the triumphal arches of Titus, Septimus Severus, and Constantine; a vast cemetery of the ages, with their funeral monuments, bearing the date of their expiry.

‘View of the Arch of Constantine with the Colosseum’

Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal) (Italian, 1697 - 1768)

Getty Open Content Program

The Doria Gallery

December the 24th, 1803.

A large landscape by Gaspar Poussin: Views of Naples: illustration of a ruined temple standing on a plain.

The waterfall at Tivoli, and the Temple of the Sybil.

A landscape by Claude Lorraine. The Flight into Egypt, by the same master; the Virgin, halted at the edge of a wood, with the Child on her knees; an angel presents food to the Child, while St. Joseph removes the pack-saddle from an ass: a bridge in the background, over which several camels, with their drivers, are passing; on the horizon barely perceptible the buildings of a great city; the tranquillity of the light is quite marvellous.

Two more small landscapes by Claude Lorraine; one of which represents the marriage of some patriarch in a wood; this is perhaps the most finished work by the famous master.

‘Pastoral Landscape’

Claude Gellée, called Claude Lorrain, French, active in Rome, 1604 - 1682

Yale Universty Art Gallery

The Flight into Egypt, by Nicolas Poussin: the Virgin and Child riding an ass, which an angel leads, descend a hill in a wood; St. Joseph follows; the effect of the wind is observable in the movement of their robes and the trees.

Several Dominichino landscapes: the colour bright and lively; the subject matter pleasant; but in general a raw vegetal tone, and a light lacking in mystery and the ideal: strange that French eyes have caught the light of the Italian atmosphere more truly!

A landscape by Annibale Carracci: great truth, but no elevation of style.

Diana and Endymion, by Rubens: the concept is good. Endymion is sleeping lightly, in the position of the beautiful Capitoline bas-relief. Diana, hovering in the air, rests one hand gently on the shoulder of the hunter, about to kiss the sleeper without waking him. The hand of the Goddess of Night is of the moon’s whiteness and her head scarcely distinguishable from the azure of the firmament. The whole is well drawn; but what Rubens drew well he painted badly; the great colourist forgot the power of his pencil when he picked up his palette.

Two heads, by Raphael. The Four Misers, by Albrecht Durer. Time plucking the feathers of Love, either by Titian or Albano: cold and mannered; the flesh-colours realistic.

The Aldobrandini Nuptials, copied from Nicolas Poussin: ten figures on the same level, forming three groups, of three, four, and three. The background is a grey expanse, breast-high: the attitudes and drawing possess the simplicity of sculpture, one might say of a bas-relief. No richness of ground-colour, no detail, draperies, furniture, trees, no accessories whatever; nothing but the figures grouped naturally.

A Moonlit Walk through Rome

From the top of the Trinità dei Monti, the steeples, and other buildings far off, look like first drafts blocked out by a painter, or like jagged coasts seen from the sea, while on board a ship at anchor.

The shadow of the Obelisk: how many have gazed at this shadow in Egypt and Rome?

Trinità dei Monti deserted: a dog barking in this French sanctuary. A little light in a high room of the Villa Medici.

‘The Villa Medici, Rome’

John Warwick Smith (1749 - 1831), British

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

The Corso: the calmness and whiteness of the buildings, the depth of the transverse shadows. The Colonna Square. The Antonine Column half-illuminated.

The Pantheon: beautiful by moonlight.

The Coliseum: its grandeur and silence in this same light.

‘The Colosseum, Rome’

John Inigo Richards (1731 - 1810), British

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

St. Peter’s: the effect of the moon on the dome; the Vatican, the Obelisk, the two fountains, and on the circular colonnade.

A young girl asked me for alms; her head enveloped in her raised robe: la poverina resembled a Madonna: she had chosen her time and place well. Had I been Raphael, I would have painted a picture of her. Romans will beg when dying of hunger, and are not importunate if refused: like their ancestors, they make no effort to sustain life; either the senate or their prince must support them.

Rome slumbers amid her ruins. That orb of the night, that globe which some have imagined to be a depopulated and deserted world, displays her pale solitudes above the solitudes of Rome; she lights streets without inhabitants; enclosures; squares; gardens where no one passes; monasteries no longer echoing with the voices of cenobites; cloisters as deserted as the porticoes of the Coliseum.

What was happening here eighteen centuries ago, at this hour? Not only is ancient Italy no more, but the Italy of the Middle Age has vanished. Nevertheless, traces of both are still plainly apparent at Rome; if the modern city vaunts her St. Peter’s and all her masterpieces, ancient Rome counters with her Pantheon and her mass of ruins; if the one marshals from the Capitol her consuls and emperors, the other leads from the Vatican her long succession of pontiffs. The Tiber separates these rival glories: founded in the same dust, Pagan Rome sinks faster and faster into her grave, while Christian Rome re-descends little by little into the catacombs from which she came.

I have in my mind subjects for a score of letters upon Italy, which might be published, if I could express my ideas as vividly as they are conceived; but the days are going by, and I must rest. I feel like a traveller, who, conscious that he must depart to-morrow, has sent his luggage on before. Our baggage consists of our illusions and our years: every minute some new fragment is given to what the Scripture calls that swift runner Time. (Of this score of letters which I have in my head, I have written only one; namely, that regarding Rome, to Monsieur de Fontanes. The several fragments that have preceded and follow might have formed materials for other letters; but I have given a description of Rome and Naples in the fourth and fifth books of Les Martyrs. Only the historical and political portion of what I wished to say concerning Italy is lacking.)

A Trip To Naples

Terracina, December the 31st.

Behold the people, carriages, things and objects one encounters pell-mell on the roads of Italy: The English and the Russians, who travel at great expense in fine sedans, with all the customs and all the prejudices of their respective countries; Italian families, journeying in old calashes, in order to travel economically to harvest the vines; monks on foot, leading by the bridle a restive mule, laden with relics; labourers driving carts drawn by large oxen, and bearing a little image of the Virgin on the pole or beam of a staff; country-women veiled, or with hair fantastically braided, wearing short brightly-coloured skirts, bodices open at the breast, and laced with ribbons, necklaces and bracelets of shells; wagons drawn by mules adorned with little bells, feathers, and red cloth; ferry-boats, bridges, mills; herds of asses, goats, and sheep; horse-dealers; couriers, with heads enveloped in a net, like the Spaniards; children quite naked; pilgrims, mendicants, penitents, in black and white robes; soldiers jolting along in wretched carts; squads of police; old men mingling with young girls. A great air of good-humour but a great air of curiosity too. They follow you with their eyes as long as they can; they look as if they wished to speak, but never say a word.

Ten at night.

I have just opened my window: the waves are breaking at the base of the walls of the inn. I never gaze at the sea again without a feeling of joy and almost tenderness

Gaeta, January 1st, 1804.

Another year gone by!

On the road from Fondi, I greeted the first orange-grove. The fine trees were as fully laden with ripe fruit as the most productive Normandy apple-trees. I write these few lines at Gaeta, on a balcony, at four in the afternoon, by the light of a brilliant sun, with the ocean in full view. Here Cicero died, in the land, as he himself said, which he had saved. Moriar in patria saepe servata (Seneca the Elder, quoting Livy. Seneca: Suasoriae 6:17) Cicero was slain by a man whom he had formerly defended; history is full of such ingratitude. Antony received, in the Forum, the head and hands of Cicero: he gave a golden crown, and a sum equal to two hundred thousand livres, to the assassin, for something beyond price: the head was nailed to the public tribune, between the orator’s hands. Under Nero, Cicero was highly praised; he was not spoken of under Augustus. In Nero’s day vice was perfected; previous assassinations ordered by the divine Augustus faded into insignificance, attempts seeming almost innocent when compared with the new. Besides, the people were far from free; they no longer knew what the word meant: were the slaves who attended the Games, in the Circus, capable of being inspired by the dreams of a Cato or a Brutus? The rhetoricians, in all the safety of servitude, were free to praise Cicero, the peasant from Arpinum. Nero himself would have been the first to harangue others on the excellence of liberty; and if the Roman people fell asleep during such a harangue, as one might imagine, their lord and master, according to custom, would have resorted to sharp blows, in order to make them applaud.

‘View of the Bridge and Part of the Town of Cava, Kingdom of Naples’

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld (French, 1758 - 1846)

Getty Open Content Program

Naples, the 2nd of January.

The Duke of Anjou, king of Naples, brother of Saint Louis, had Conrad, the legitimate heir to the crown of Sicily, put to death. Conrad, on the scaffold, threw his glove into the crowd. Who picked it up? Louis XVI, a descendant of Saint Louis.

The kingdom of the Two Sicilies must be regarded as something apart from Italy. Greek under the Romans, it has been since that time Saracen, Norman, German, French, and Spanish.

Medieval and Renaissance Italy was the Italy of two great factions, Guelf and Ghibelline; the Italy of republican rivalries and petty tyrannies: nothing was proclaimed but crime and liberty; everything was achieved at the point of a knife. The adventures of this Italy are full of romance: who has not heard of Ugolino, Francesca da Rimini, Romeo and Juliet, Othello? The Doges of Genoa and of Venice, the Princes of Verona, Ferrara and Milan, the warriors, navigators, writers, artists, and merchants, of this Italy, were all men of genius: Grimaldi, Fregose, Adorni, Dandolo, Marino Zeno, Morosini, Gradenigo, Scaligieri, Visconti, Doria, Trivulzio, Spinola, Carlo Zeno, Pisani, Christopher Colombus, Amerigo Vespucci, Gabato, Dante, Petrarch, Bocchacio, Ariosto, Machiavelli, Cardan, Pomponazzi, Achellini, Erasmus, Poliziano, Michelangelo, Perugino, Raphael, Giulio Romano, Dominichino, Titian, Correggio, the Medicis; yet amongst them all not a single knight; in fact, none of the ethos of Transalpine Europe.

At Naples, on the contrary, chivalry blended with the Italian character and noble exploits with popular uprisings. Tancred and Tasso; Joan of Naples; and the good king Réné who never reigned there; the Sicilian Vespers; Massaniello; and the last Duke of Guise; such is the history of the Two Sicilies. The breath of Greece expired at Naples; Athens pushed its frontiers as far as Paestum: its temples and tombs are ranged in line at the far horizon of an enchanted sky.

I was not impressed with Naples on arrival: from Capua, and its delights, to here, the country is fertile, but hardly picturesque. You enter Naples almost without seeing it, by a deeply-cut road. (You can no longer follow the old route, even if you desire to do so. In the last period of French rule, another entrance was made, and a fine road has been created round the hill of Posillipo.)

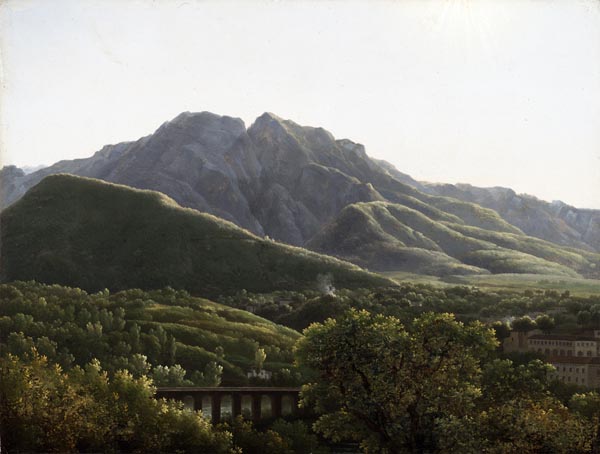

‘Mountain Landscape with Road to Naples’

Jean-Charles-Joseph Rémond (French, 1795 - 1875)

Getty Open Content Program

January the 3rd, 1804.

Visited the Museum.

A statue of Hercules, of which there are copies everywhere. Hercules in repose, leaning on the trunk of a tree: the lightness of the club. Venus: beauty of form; wet drapery. A bust of Scipio Africanus.

Why should ancient sculpture be so superior to the modern (this assertion, generally true, admits of numerous exceptions. Antique statuary has nothing that surpasses the Caryatids of the Louvre, by Jean Goujon. We have these master-works daily before our eyes, yet we fail to notice them. The Apollo has been praised far too much: the metopes of the Parthenon alone exhibit the perfection of Greek sculpture. What I said respecting the Arts, in Le Génie du Christianisme, is eccentric, and often incorrect. At that time I had not visited Greece, Italy, or Egypt.), while modern painting is apparently superior or, at all events, equal to the ancient?

With regard to sculpture, I reply:

The manners and customs of the ancients were more serious than ours, their passions less turbulent. Now, sculpture, which is unable to mark subtle nuances or movements, accommodates itself more easily to the tranquil gesture and grave physiognomy of the Greeks or Romans. Moreover, the antique draperies display the naked figure in part, a nakedness which was therefore always visible to the artist’s eye, whilst it is only rarely exposed to that of the modern sculptor; finally, the human form was more beautiful then.

With regard to painting, I would say:

Painting admits a higher degree of freedom in the way figures are posed; consequently, matter, when unfortunately it is visible, detracts less from the fine effects of drawing. The rules of perspective, with which sculpture has little involvement, are better understood by the moderns. We are likewise acquainted with a greater range of colours, although it is yet to be discovered whether they are purer or more brilliant.

In my review of the Museum, I admired Raphael’s Mother, painted by her son; unassuming and beautiful, she somewhat resembles Raphael himself, as the virgins of this divine master resemble angels.

Michelangelo, painted by himself.

Armida and Rinaldo; the scene involving the magic mirror.

Pozzuoli and Solfatara

January the 4th.

At Pozzuoli (Puteoli) I examined the Temple of the Nymphs, Cicero’s house, which he named the Puteolana, from which he often wrote to Atticus, and in which he probably composed his Second Philippic. This villa was built to the plan of the Academy in Athens; later embellished by Antistius Vetus, it was turned into a palace under the Emperor Hadrian, who died there, bidding farewell to his soul in the well-known lines:

Animula vagula, blandula,

Hospes comesque corporis…

Little soul, pale and wandering,

Guest and friend of my body…

‘Cicero's Villa and the Gulf of Pozzuoli’

Richard Wilson (1714 - 1782), British

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

He asked for an inscription on his tomb to the effect that he was killed by his physicians:

Turba medicorum regem interfecit: a crowd of doctors killed an Emperor (Dio 69.22.4)

The science has since progressed.

At that epoch, all men of talent were either Christians or ‘philosophers.’

A fine view from the Portico in which you see: a little orchard now occupying the site of Cicero’s house, the Temple of Neptune, and some tombs.

Solfatara: a volcanic field. The sound of springs of boiling water; the sound of Tartarus to the poets.

The view of the Gulf of Naples while returning: a cape outlined by the light of the setting sun; the reflection of this light on Vesuvius and the Apennines; the concord or harmony between this radiance and the sky. Diaphanous vapours on the surface of the water and half-way up the mountain. The white sails of vessels entering the port. The isle of Capri in the distance. The hill of the Camaldolese, with its convent and clump of trees, aboveNaples. The contrast of all this with Solfatara. A Frenchman inhabits the island to which Brutus retired. The Grotto of Aesculapius. The Tomb of Virgil, from which can be seen the birthplace of Tasso (Sorrento).

Vesuvius

January the 5th, 1804.

Today, the 5th of January, I left Naples, at seven in the morning; here I am at Portici. The sun has dispersed the cloud in the east, but the top of Vesuvius is, as ever, cloaked in mist. I ascend the mountain with a guide, who provides two mules, one for me, another for himself: we are off.

‘Lago d'Agnano with Vesuvius in the Distance’

Richard Wilson (1714 - 1782), British

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

I begin my journey by a tolerably wide road, between two plantations of vines, trained up poplar-trees. I walk straight into a wintry easterly. I see, a little above the vapour descended from the middle regions of the air, the tops of some trees: they are the elms of the hermitage. The wretched dwellings of vine-dressers are visible on either side, among an abundance of Lachrymae Christi vine-stocks. For the rest: parched soil everywhere, naked vines mingled with pine-trees shaped like umbrellas, some aloes in the hedge, innumerable unstable stones, not a single bird.

I reach the first plateau. A bare plain stretches before me. I can see the twin summits of Vesuvius; on the left Mount Somma, on the right the present mouth of the volcano: these two heights are enveloped in pale clouds. I proceed. On one side the Somma slopes away, on the other I begin to distinguish the ravines cut into the cone of the volcano which I am about to climb. The lava from 1766 and 1769 covers the plain I am crossing. It is a smoky desert, where the lava, thrown out like dross from a forge, displays, on a black ground, its whitish scum exactly like dried moss.

With the cone of the volcano on the right, I follow the road to the left, and reach the foot of a hill or rather wall, formed of the lava which overwhelmed Herculaneum. This wall of sorts is planted with vines on the borders of the plain, and on the other side is a deep valley, filled by a copse. The cold becomes biting.

I climb this hill to visit the hermitage on the other side. The heavens lower: the clouds stream over the ground like grey smoke, or ashes driven before the wind. I begin to hear the murmur of the hermitage elm-trees.

The hermit came out to greet me. He held the bridle of my mule and I alighted. The hermit is a tall man with a frank expression and fine countenance. He invited me to his cell; laid the table, and set out bread, apples, and eggs. He sat opposite me, resting his elbows on the table, and conversed calmly while I breakfasted. The clouds gathered all round us, and not a thing could be seen from the windows of the hermitage. In this vapour-filled abyss you only hear the whistling of the wind, and the distant noise of the waves breaking on the shore of Herculaneum; a tranquil scene of Christian hospitality, set in a small cell at the foot of a volcano in the midst of a tempest!