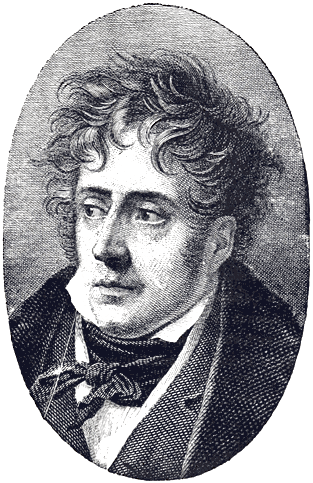

François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Testamentary Preface 1833

‘Portrait de Chateaubriand’

Zig-Zags en Bretagne, etc. Illustré - H. Dubouchet (p283, 1894)

The British Library

Sicut nubes.quasi naves.velut umbra:

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

Testamentary Preface 1833

Paris, 1st December 1833

Preface:Sect1

As it is impossible for me to foresee the moment of my death; as, at my age, the days granted to man are only days of grace, or rather of hardship, I intend, for fear of being taken by surprise, to explain the nature of a work destined to beguile for me the boredom of these last lonely hours, that no one wants, and that one does not know how to employ.

The Mémoires, at whose head this preface is placed, embrace or will embrace the entire course of my life: they were begun in the year 1811, and have been continued down to today. I recount in what has been completed, and will recount in what has only been sketched out so far, my childhood, my education, my youth, my entry into the service, my arrival in Paris, my presentation to Louis XVI, the opening scenes of the Revolution, my travels in America, my emigration to Germany and England, my return under the Consulate, my occupations and works under the Empire, and finally the complete history of that Restoration and its fall.

I have met almost all the men who have played a large or small role, both abroad and in my own country, from Washington to Napoleon, from Louis XVIII to Czar Alexander, from Pius VII to Gregory XVI, from Fox, Burke, Pitt, Sheridan, Londonderry, and Capo-d’Istria, to Malesherbes, Mirabeau, etc; from Nelson, Bolivar, Mehemet Ali, Pasha of Egypt, to Suffren, Bougainville, La Pérouse, Moreau, etc. I have formed one of an unprecedented triumvirate: three poets of different interests and nationalities, found themselves, almost at the same moment, Foreign Ministers: myself of France, Mr Canning of England, and Señor Martinez de la Rosa of Spain. I have traversed in succession the empty years of my youth, the full years of the Republican era, the splendours of Napoleon and of the reign of the Legitimacy.

Preface:Sect2

I have explored the seas of the Old World and the New, and trodden the soil of the four quarters of the Earth. Having camped in the cabins of Iroquois, and beneath the tents of Arabs, in the wigwams of Hurons, in the remains of Athens, Jerusalem, Memphis, Carthage, Granada, among Greeks, Turks and Moors, among forests and ruins; after wearing the bearskin cloak of the savage, and the silk caftan of the Mameluke, after suffering poverty, hunger, thirst, and exile, I have sat, a minister and ambassador, covered with gold lace, gaudy with ribbons and decorations, at the table of kings, the feasts of princes and princesses, only to fall once more into indigence and know imprisonment.

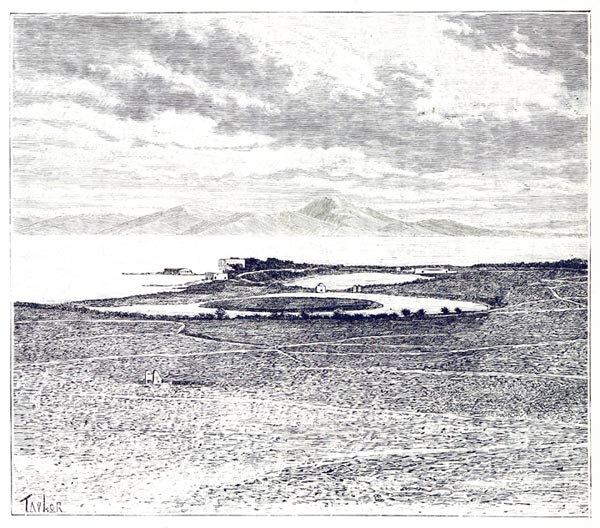

‘Les Anciens Ports de Carthage’

La France et les Colonies, Illustré - Onésime Reclus (p14, 1887)

The British Library

I have had dealings with a host of famous celebrities in the military, the Church, politics, the judiciary, the arts and sciences. I possess an immense mass of material, more than four thousand private letters; the diplomatic correspondence from my various embassies; and those of my stay at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; among which are items private to myself, unique and unpublished. I have borne the musket of a soldier, the traveller’s cane, and the pilgrim’s staff: as a sailor my fate has been as inconstant as the wind: a kingfisher, I have made my nest among the waves..

I have been party to peace and war: I have signed treaties, protocols, and along the way published numerous works. I have been made privy to party secrets, of court and state: I have viewed closely the rarest disasters, the greatest good fortune, the highest reputations. I have been present at sieges, congresses, conclaves, at the restoration and demolition of thrones. I have made history, and been able to write it. And my solitary life, of a dreamer and poet, traversed this world of realities, catastrophes, tumult, noise, with the sons of my dreams, Chactas, René, Eudore, Aben-Hamet: with the daughters of my imaginings, Atala, Amélie, Blanca, Velléda, Cymodocée. Within and alongside my age, perhaps without wishing or seeking to, I have exerted upon it a triple influence, religious, political and literary.

Preface:Sect3

I have no more than four or five contemporaries of established fame still around me. Alfieri, Canova and Monti are gone: Italy retains only Pindemonte and Manzoni from its days of brilliance, Pellico has spent his best years in the dungeons of Spielberg; the talents of Dante’s native land are condemned to silence, or forced to languish on foreign soil: Lord Byron and Mr Canning died young: Walter Scott has left us, Goethe has quit us loaded with glory and years. France has almost nothing left now of her rich past; she begins a new era: I remain to bury my age, like the old priest who, at the sack of Béziers, had to ring the bell before dying himself when the last citizen had expired.

When death lowers the curtain between me and the world, it will be found that my drama is divided into three acts.

From my early youth until 1800, I was a soldier and traveller; from 1800 to 1814, under Consulate and Empire, my life was literary; from the Restoration until the present day my life has been political.

In my three successive careers, I have always set myself a great task: as a traveller, I wished to open up the Polar regions; as a writer I tried to re-establish religion on its own ruins; as a statesman I endeavoured to give the nations the true system of constitutional monarchy with its various freedoms: I have at least helped to win that which equals all of them, can take their place, and stands instead of a constitution, the freedom of the Press. If I have often failed in my enterprises, it has been in my case the fault of destiny. Foreigners who have succeeded in their projects have been favoured by fortune: they had powerful friends supporting them, and a country at peace: I have not had that happiness.

Preface:Sect4

Of the modern French authors of my age, I am almost the only one whose life resembles his works: traveller, soldier, poet, publicist, it was in the forest that I sang of forests, aboard ship that I described the sea, in camp that I spoke of weapons, in exile that I learned about exile, at court, in assemblies, amongst public affairs, that I studied princes, politics, law and history. The orators of Greece and Rome were involved in public life and shared its destiny. In the Italy and Spain of the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the foremost geniuses of literature and the arts participated in social evolution. What stormy and beautiful lives, those of Dante, Tasso, Camoëns, Ercilla and Cervantes.

In France, our ancient poets and historians wrote and sang in the midst of pilgrimages and battles: Thibault IV, Comte de Champagne, Villehardouin, Joinville, owe the felicities of their style to the adventures they lived: Froissart searched for history on the high roads, learned it from the knights and priests he met, with whom he rode. But from the reign of Francis I, our writers have been isolated individuals whose talents could express the spirit but not the events of their time. If I were destined to survive, I would represent in person, as they are presented in my Mémoires, the principles, ideas, events, catastrophes, the epic of my time, all the more so because I have seen a world begin and end, and the opposing characteristics of that end and that beginning are involved in my opinions. I found myself between two centuries as at the confluence of two rivers; I plunged into their troubled waters; regretfully leaving the ancient strand where I was born, and swimming hopefully towards the unknown shore where new generations will land.

Preface:Sect5

These Mémoires, divided into books and chapters, were written at different dates and in different places: these divisions naturally give rise to a species of prologue that recall the incidents which have occurred since the previous dates, and describe the places in which I pick up the thread of my story. The varied events and changing forms of my life thereby involve one another: so, in moments of prosperity I speak of times of poverty, and in days of tribulation recall days of happiness. The varied sentiments of my various years, my youth penetrating my old age, the gravity of my years of maturity saddening my green years; the rays of my sun from its rising to its setting, crossing and meeting like separate reflections of my existence, give a kind of indefinable unity to my work: my cradle speaks of my tomb, my tomb of my cradle; my sufferings become pleasures, my pleasures sorrows, and one does not know if these Mémoires are the work of a young head or an old one.

I am not saying a word of this to justify myself, since I am not sure it is a good idea: I say what is, what happened, without consideration, through the very inconstancy of the tempests unleashed against my barque, and which have frequently left me only the reef on which I have been shipwrecked to write this or that fragment of my life.

I have shown a paternal partiality towards these Mémoires; I would like to come back to life at the witching hour to correct the proofs: the dead are in haste.

The notes that accompany the text are of three kinds: the first, placed at the end of the books, consist of clarifications and written proofs; the second, at the foot of the pages, are from the same period as the text; the third similarly at the foot of the pages, have been added since the composition of the text, and carry the place and date where they were written. One or two years of solitude in some corner of the earth would suffice to complete these Mémoires; but I have had no peace except for the nine months when my being lay in my mother’s belly: it is probable that I shall never recover that ante-natal peace, except in the womb of our communal mother, after death.

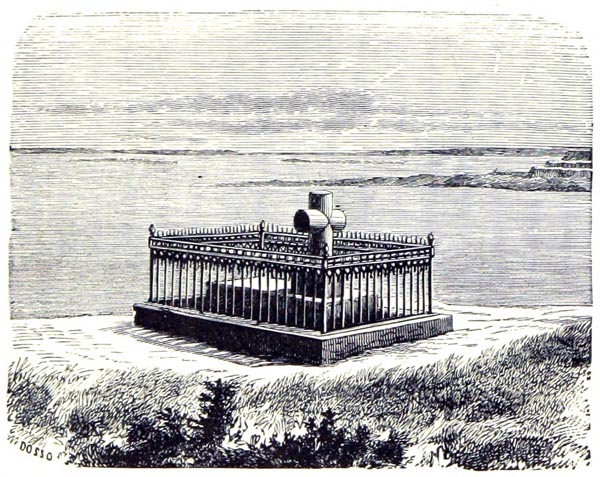

Several of my friends have urged me to publish part of my story now; I could not accede to their wish. Firstly, despite myself, I would inevitably be less frank and truthful, and secondly I have always imagined I was writing while seated in my coffin. The work has acquired from that a certain religious quality which I could not remove without doing harm; it would pain me to suppress that distant voice from the tomb that can be heard throughout the whole course of my tale. It will not seem strange if I defend certain weaknesses; if I am preoccupied with the fate of a poor orphan, destined to remain after me on earth. If I have suffered enough in this world to be a happy shade in the next, a little light from the Elysian Fields, illuminating my last portrait, may serve to render the artist’s failings less obvious: life suits me ill; perhaps death will become me better.

‘Tombeau de Chateaubriand’

La France Pittoresque. Ouvrage Illustré - Jules Gourdault (p88, 1893)

The British Library

End of the Testamentary Preface 1833