François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XLII: Conclusion 1834-1841

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XLII: Chapter 1: THE PRESENT POLITICAL SITUATION: – Louis-Philippe

- Book XLII: Chapter 2: Monsieur Thiers

- Book XLII: Chapter 3: Monsieur de Lafayette

- Book XLII: Chapter 4: Armand Carrel

- Book XLII: Chapter 5: VARIOUS WOMEN: A Lady from Louisiana

- Book XLII: Chapter 6: Madame Tastu

- Book XLII: Chapter 7: Madame Sand

- Book XLII: Chapter 8: Monsieur de Talleyrand

- Book XLII: Chapter 9: The Death of Charles X

- Book XLII: CONCLUSION

- Book XLII: Chapter 10: Historic antecedents: from the Regency to 1793

- Book XLII: Chapter 11: The Past – The old European Order expires

- Book XLII: Chapter 12: Inequality of wealth – Dangers in the nature of intellectual and material growth

- Book XLII: Chapter 13: The demise of monarchy – The withering away of society and the progress of the individual

- Book XLII: Chapter 14: The Future – The difficulty of comprehending it

- Book XLII: Chapter 15: Saint-Simonians – Phalansterians – Fouriérists – Owenites – Socialists – Communists – Unionists - Egalitarians

- Book XLII: Chapter 16: The Christian ideal is the future of the world

- Book XLII: Chapter 17: A Recapitulation of my life

- Book XLII: Chapter 18: A summary of the changes which have occurred around the globe in my lifetime

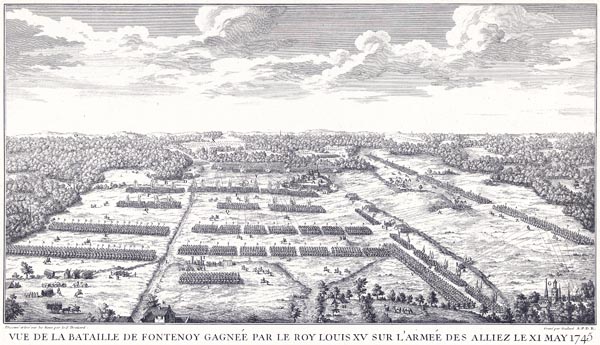

Book XLII: Chapter 1: THE PRESENT POLITICAL SITUATION: – Louis-Philippe

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, 1837 (Revised, June 1847)

BkXLII:Chap1:Sec1

If, as I pass from the politics of the Legitimacy to politics in general, I re-read what I published on those politics in the years 1831, 1832, and 1833, my predictions have been accurate enough.

Louis-Philippe is an intelligent man whose tongue is set in motion by a torrent of commonplaces. He pleases a Europe which reproaches us for not recognising his worth; England loves to see that we, like her, have dethroned a king; the other sovereigns have deserted the Legitimacy which they have not found obedient. Philippe dominates those about him; he toys with his Ministers; he appoints them, dismisses them, re-appoints them, and dismisses them once more, having compromised them, if anything these days can compromise anyone.

Philippe’s superiority is real, but it is only relative; place him in an age when society was vibrant, and the mediocrity within would be revealed. Two passions detract from his qualities: his exclusive love for his children, and his insatiable desire to increase his wealth: on those two matters he will always show blindness.

Philippe does not feel for France’s honour as the elder branch of the Bourbons do; he has no need of honour: he has no fear of popular uprisings as those nearest to Louis XVI feared them. He is protected by his father’s murder; hatred for wealth does not touch him: he is an accomplice not a victim.

Understanding the exhaustion of the age and the baseness of men’s souls, Philippe takes comfort from the situation. Legal intimidation has suppressed our freedoms, as I predicted at the time of my farewell speech to the Chamber of Peers, and nothing has lessened it; arbitrary powers have been employed; murder has been done in the Rue Transnonain, protesters bombarded at Lyons, numerous prosecutions begun against the Press; citizens arrested and held in prison for months or years as a preventative measure, to public applause. The country, weary, no longer understanding anything, endures everything. There is scarcely a man one could not set against himself. Month after month, year after year, we have written, spoken and acted in a manner completely contrary to the way we have formerly written, spoken and acted. Through being forced to blush we no longer blush; our self-contradictions escape our notice, they have multiplied so. To end discussion we take the position of affirming that we have never changed, or that we have only changed through progressive modification of our ideas and through our century’s clarification of our understanding. The rapidity of events has aged us so swiftly that when we recall our actions of past days, we seem to be speaking of others rather than ourselves; and then, to have changed is only to have done as everyone else has.

‘Rue Transnonain, Lithograph by Honoré Daumier’

Skämtbilden och Dess Historia i Konsten - Carl Gustaf Johannes Laurin (p181, 1910)

Internet Archive Book Images

Philippe did not believe, as the restored monarchy did, that he was obliged to control every village in order to rule; he judged it sufficient to be master of Paris; now, if he could only put the capital on a war footing with an annual quota of sixty thousand praetorian guards, he would believe himself safe. Europe would allow it because he would persuade the sovereigns that he was acting with a view to stifling revolution in his old cradle, depositing as a guarantee, in the hands of foreigners, France’s liberty, independence and honour. Philippe is a police-sergeant: Europe might spit in his face, he would wipe it, say thank you, and show his royal patent. However, he is the only prince the French are currently capable of tolerating. The debasement of elected leadership is his strength: we find enough in him, momentarily, to satisfy our royalist habits and our democratic tendency; we obey a power that we think we have the right to insult; that is all we need of liberty: a nation on its knees, we snuffle round our master, privilege re-established at his feet, equality in his face. Cynical and cunning, a Louis XI for the age of philosophy, our chosen monarch skilfully sails his boat over a sea of mud. The elder branch of Bourbons has withered save for one bud; the younger branch is rotten. The leader inaugurated at City Hall thinks only of self; he sacrifices the French to what he believes to be his own security. When people discuss what is necessary for our country’s greatness, they forget the sovereign’s character; he is persuaded that he will perish by the very means which would save France; according to him, what would ensure the survival of the monarchy would destroy the king. Moreover, none have the right to hold him in contempt, since everyone is equally contemptible. But, in the final analysis, whatever prosperity he dreams of, neither he nor his children will prosper, because he abandons the people who brought him everything. Yet on the other hand, legitimate kings, abandoning legitimate kings, will fall: one cannot renounce principles with impunity. If Revolution has for an instant deviated from its course, it will no less add to the torrent that undermines the ancient edifice: no one has played his part, no one will be saved.

Since power among us is inviolable, since the hereditary sceptre has fallen to the ground four times in thirty-eight years, since the royal fillet tied by victory has twice been unbound from Napoleon’s head, since the July monarchy has been increasingly assailed, one must conclude that it is monarchy and not the Republic which is untenable.

France is under the domination of an ideal inimical to the throne: a crown whose authority is at first recognised, which is then trodden underfoot, then picked up to be trodden underfoot again, is no more than a vain temptation and a symbol of disorder. A master is imposed on men who appear to demand him for memory’s sake but will not support him morally; he is imposed on generations who, having forgotten social moderation and decency, know only how to insult the royal personage or replace respect with servility.

Philippe has within him something that hinders destiny; he has nothing within him that can halt it. The democratic party alone advances, because it is marching towards the future. Those who will not concede the general trends which are destroying the basis for monarchy will seek in vain for action from the Chambers to free us from the yoke; the Chambers will not consent to reform because reform would signal their death. The industrialised opposition, for its part, will never willingly bring the king products from its factories, as it did Charles X; it shifts about to create room for itself, it whines, and is difficult; but when it finds itself face to face with Philippe, it retreats, since though it wants to gain control of affairs, it does not want to reverse what it has created and what it lives for. Two fears inhibit it: fear of the Legitimacy’s return, fear of populist rule; it sticks to Philippe whom it does not love, but whom it treats as a protector. Satisfied by wealth and work, abdicating its will, the opposition obeys what it knows to be worthless and sleeps in the mud; that is the bed of down invented by an industrial century; it is not as pleasant but it costs less.

Notwithstanding all that, a sovereignty of a few months, or even a few years if you wish, will not alter the irrevocable future. There is hardly anyone now who does not consider the Legitimacy preferable to the usurpation, in terms of security, liberty, property, and foreign relations, since the principle behind our current monarchy is inimical in principle to European sovereignty. Though it pleased him to accept the investiture of the throne, at the pleasure of, and with the sure methods of democracy, Philippe has forgotten his point of departure: he should have leapt onto his horse and galloped to the Rhine, or rather he should have resisted the impulse that carried him to a crown regardless of conditions: the most durable and fitting institutions emerge from such resistance.

It is said that: ‘Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans could not have rejected the crown without plunging us into appalling problems’: the logic of cowards, dupes and rogues. Doubtless conflict would have occurred; but it would have been followed by a swift return to order. What has Philippe done for the country? Would there have been more blood spilt by his refusing the sceptre, in Paris, Lyons, Anvers and in the Vendée, than has been shed by his accepting it, without taking into account the rivers of blood that have flowed on account of our elective monarchy in Poland, Italy, Portugal and Spain? Has Philippe given us liberty, in compensation for these ills? Has he brought us glory? He has spent his time begging for legitimisation by the powers that be, degrading France by making her a servant of England, and leaving her a hostage; he has tried to make the century come to him, and render him and his race venerable, not wishing to renew himself with the century.

Why did he not marry his eldest son to some lovely plebeian girl of his own country? That would have been to wed France herself; that union of the people and royalty would have made foreign kings repent; since those kings, who have already taken advantage of Philippe’s subservience, will not be content with what they have gained: that popular power which is revealed behind our municipal monarchy terrifies them. The monarch of the barricades, in order to be completely acceptable to absolute monarchs, must above all destroy freedom of the Press and abolish our constitutional institutions. In the depths of his soul, he detests them as much as they do, but he has to act in moderation. All this procrastination irritates other monarchs; they cannot be made to tolerate it except by our giving way to them completely abroad: to accustom us to being Philippe’s bondsmen at home, we have begun by becoming the vassals of Europe.

I have said a hundred times and I will repeat it once more, the old society is dead. I am not enough of a common man, not enough of a charlatan, not deceived enough in my hopes, to take the least interest in what now exists. France, the most mature of present-day nations, will probably be first among them. It is likely that the elder branch of the Bourbons, whom I will support until death, will even now obtain scant shelter from the old monarchy. The successors of a murdered monarch have never worn his torn robe for long; there is mistrust on both sides: the prince no longer dares trust the nation; the nation cannot believe that a restored family will show forgiveness. A scaffold raised between a people and its king prevents them seeing one another: there are graves which never close. The head of Capet was so high, that the diminutive executioners were obliged to cut it off to take his crown, as the Caribs cut down a palm tree to gather its fruit. The Bourbon stock was propagated in various stems around it; it put out branches which in bowing took root in the earth and rose again as proud offshoots: that family, after having been the pride of other royal races, seems to have become their fate.

But would it be reasonable to believe that Philippe’s descendants have a greater chance of reigning than Henri IV’s young descendant? It is fine to combine diverse political concepts, but moral truth remains immutable. There is an inevitable reaction, educative, magisterial, and vengeful. The monarch who initiated our freedom was forced to expiate in his own person Louis XIV’s despotism and Louis XV’s corruption; and who is to say that Louis-Philippe, he or his descendants, will not pay a debt for the Regency’s depravations? Was that debt not contracted anew by Egalité on Louis XVI’s scaffold, and has not Philippe his son added to the paternal debt, when, as a disloyal tutor, he dethroned his pupil? Egalité bought nothing in the losing of his life; tears at the moment of death purchase nought: they merely wet the breast, but do not fall on conscience’s soil. If the Orléans branch were to reign by virtue of the vices and crimes of its ancestors, where then would Providence be? No more terrible temptation would ever have tried men of goodwill. Our illusion is that we can weigh the eternal design in the scale of our short life: we vanish too swiftly for God’s punishment always to occur in the brief moment of our existence; punishment descends at the right moment; it no longer strikes the initial offender, but strikes his race which provides it with space to act.

In the universal scheme of things, Louis-Philippe’s reign, whatever its duration, will be no more than an anomaly, a momentary offence against the enduring laws of justice: they are violated, those laws, in a narrow and relative way; they are followed in a limitless and general one. From an enormity apparently consented to by Heaven, one must draw the greatest of consequences: one must deduce a Christian proof of the coming abolition of royalty itself. It is that abolition, not some individual punishment, which must expiate Louis XVI’s death; no one will be allowed, according to this exercise of justice, to wear the crown, witness Napoleon the Great, and Charles X the Pious. It may have been permitted for the son of a regicide to lie down for a moment, in imitation of kingship, on a martyr’s blood-stained bed, in order to render monarchy odious.

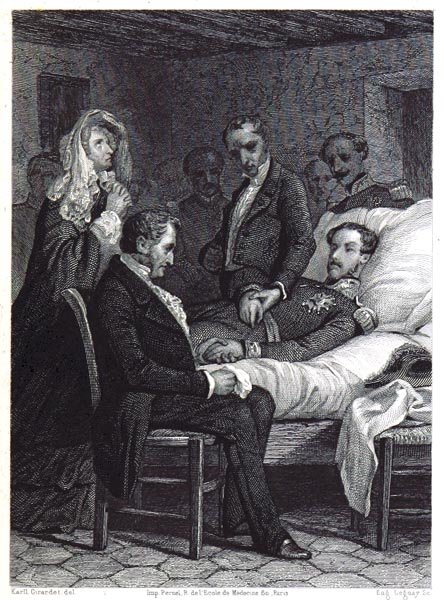

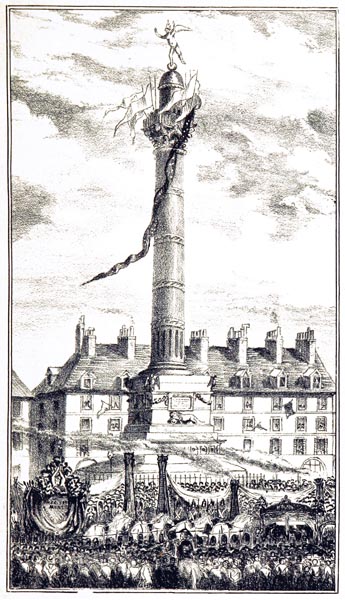

‘Mort du Duc d'Orléans’

Le Dernier Roi - Alexandre Dumas (p603, 1854)

The British Library

Finally, all this reasoning, correct though it may be, will never weaken my loyalty to my young King: if I am all that is left to him in France, I will be forever proud to have been the last subject of one who may be the last king.

Book XLII: Chapter 2: Monsieur Thiers

BkXLII:Chap2:Sec1

The July Revolution found a king: has it found a representative? I have described the men of various epochs who have appeared on the scene from 1789 to the present day. Those men belonged more or less to the human race as was: there was a scale of proportion on which to measure them. We have arrived at generations who are no longer part of the past; studied beneath a microscope, they seem incapable of life, and yet they merge with the elements in which they move; they can breathe air one would have thought un-breathable. The future may invent formulas to calculate the rules of existence of these beings; but the present has no means of assessing them.

Without the power then to explain the altered species, here and there one notices a few individuals on whom one can seize, because specific faults or distinct qualities make them stand out from the crowd. Monsieur Thiers, for example, is the one man the Revolution has produced. He founded the school that admires the Terror, a school to which he belongs. If the perpetrators of the Terror, those deniers and denied of God, were such great men, the authority of their opinions would carry some weight; but those men, tearing each other apart, declared that the party whose throats they were cutting was a band of rogues. Read what Madame Roland says of Condorcet, what Barbaroux, principal actor of the 10th of August, says of Marat, what Camille Desmoulins writes in criticism of Saint-Just. Should Danton be assessed according to Robespierre’s view, or Robespierre according to Danton’s? When the members of the Convention had such a poor opinion of one another, how, without lacking in the respect one owes, dare one hold an opinion differing from theirs?

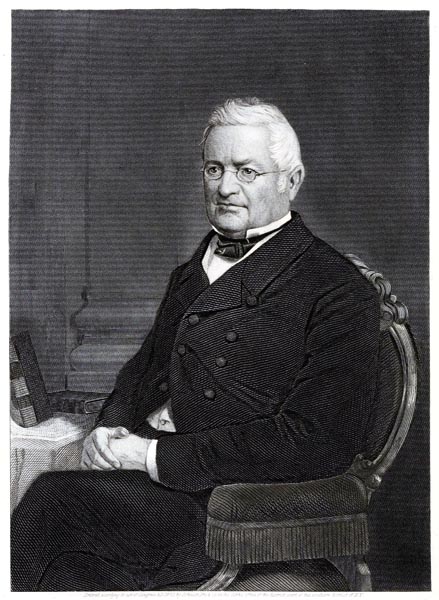

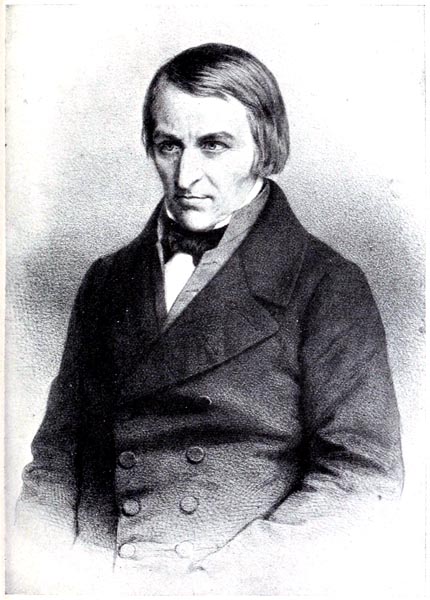

‘A. Thiers, from the Original Painting by Chappel’

Portrait Gallery of Eminent Men and Women of Europe and America - Evert Augustus Duyckinck (p519, 1873)

Internet Archive Book Images

I very much fear however that those who been have taken for extraordinary individuals were brutes worth little more than the wheels on a machine. The machines and its cogs have been confused: the machine was powerful, but it was not the wheels that made it. Who invented it then? God: he created it for necessary ends that also derived from Him, at a moment of society which was foreseen.

With its materialistic approach, Jacobinism did not perceive that the Terror had failed, incapable of fulfilling the conditions for its continuation. It could not achieve its end because it could not cause enough heads to roll; it fell four or five hundred thousand or more short: now, time was lacking to execute these lengthy massacres; only unfinished crimes remained whose fruit no one knew how to gather, the last hours of the storm having failed to ripen it.

The secret of the contradictory nature of the men of today lies in a lack of moral sense, in the absence of settled principles and in the cult of force: whoever succumbs is guilty and without merit, at least without that merit that adjusts itself to events. One must be aware of what is hidden behind the liberal phraseology of devotees of the Terror: success deifies. To adore the Convention is merely to adore a tyrant. The Convention once overthrown, you pass with your bundle of freedoms to the Directory, then to Bonaparte, without suspecting your metamorphosis, without considering what you have done. A sworn dramatist, while considering the Girondins as feeble devils because they were vanquished, you will make of their deaths no less fantastic a picture: they are fine young men marching to the sacrifice crowned with flowers.

The Girondins, a cowardly faction, which spoke in favour of Louis XVI then voted for his execution, behaved marvellously well, it is true, on the scaffold; but who did not bow their head before death in those days? Women distinguished themselves by their heroism; the young girls of Verdun mounted the altar like Iphigenias; the workers, about whom they are discretely silent, those plebeians of whom the Convention made so great a harvest, braved the executioner’s steel as resolutely as our grenadiers did that of the enemy. For every priest and nobleman, the Convention destroyed thousands of working people in the lowest classes of society; that is what no one chooses to remember.

Does Monsieur Thiers proclaim principles? Not in the least; he advocated massacre, and would preach humanity in just as edifying a manner; he would give himself out to be fanatical about freedom, and yet he oppressed Lyons, fired on the Rue Transnonain, and has stood for and against all the September 1835 laws: if he were ever to read this, he would take it for a eulogy.

As President of the Council, and Foreign Minister, Monsieur Thiers is enraptured by diplomatic intrigues of the school of Talleyrand; he exposes himself to being taken for a serial parasite, lacking in nerve, gravity and discretion. One might disdain seriousness and grandeur of soul, but one should not say so, without having first led a subjugated world to take part in one’s orgies at Grand-Vaux.

Yet Monsieur Thiers combines inferior manners with noble instincts; while the surviving feudalists, now impoverished, become stewards on their own lands, Monsieur Thiers, a great Renaissance lord, travelling about like a new Atticus, buys works of art on the road and revives the prodigality of the ancient aristocracy: it is a kind of distinction: but while he sows with as much facility as he reaps, he needs to guard against his old habits of camaraderie: esteem is one of the ingredients of a public persona.

Stirred by his mercurial character, Monsieur Thiers set out to crush anarchy in Madrid as I suppressed it in 1823: a project all the braver in that Monsieur Thiers was in conflict with Louis-Philippe’s intentions. He may consider himself a Bonaparte; he may believe his letter-knife to be merely an elongation of a Napoleonic sword; he may persuade himself he is a great general, he may dream of conquering Europe, by reason of having constituted himself narrator, and in a very ill-considered move by having Napoleon’s remains brought back here. I accede to all these pretensions; I will merely say that, regarding Spain, at the moment at which Monsieur Thiers thought of invading it, his calculations were in error; he would have ruined his monarch in 1836, while I saved mine in 1823. The essential thing is to do what one desires at the right time: there are two forces: the force of men and the force of events; when the two are in opposition, nothing can be accomplished. At this moment, Mirabeau would sway no one, even though his corruption might not harm him: since no one is disparaged for vice these days; one is only denounced for one’s virtues.

Monsieur Thiers has one of three courses to take: name himself the representative of the republican future, cling to the counterfeit July Monarchy like a monkey on a camel’s back, or revive the Imperial order. The latter course is to Monsieur Thiers taste; but an empire without an emperor, is that credible? It is more natural to believe that the author of a History of the Revolution will allow himself to be consumed by vulgar ambition: he wishes to remain in or re-enter power; in order to keep or re-gain his place, he will utter all the palinodes that the moment or his interests would seem to require; there is a certain audacity in disrobing in public, but is Monsieur Thiers still young enough for his good looks to serve as a veil?

Setting Deutz and Judas aside, I recognize in Monsieur Thiers a supple mind, quick, subtle, flexible, heir to the future perhaps, understanding all, save the greatness that derives from the moral order; free of envy, without pettiness or prejudice, he stands apart from the dull and obscure crowd of mediocrities around him. His exaggerated pride is yet not odious, because it does not involve contempt for others. Monsieur Thiers has resource, variety, favourable gifts; he is scarcely bothered by differences of opinion, bears no grudges, never fears compromising himself, does another man justice, not through probity or because of what he thinks but because of his worth; which would not prevent him from strangling us of all if the need arose. Monsieur Thiers is not what he might be; age will alter him, to the extent that swollen pride does not inhibit it. If his mind holds firm and he is not carried away by some sudden impulse, events will reveal unknown superiorities in him. He will rise or fall swiftly; there is the possibility that Monsieur Thiers will become a great Minister or remain half-formed.

Monsieur Thiers has already shown lack of resolve when he held the fate of the world in his hands: if he had given the order to attack the English fleet, superior in strength as we then were in the Mediterranean, our success would have been assured; the Turkish and Egyptian fleets, combining in the port of Alexandria, would have augmented ours; victory over England would have electrified France. We would have instantly found 150,000 men to send into Bavaria and hurl at whatever positions in Italy were unprepared or had not foreseen an attack. The whole world might yet have been altered. Would our aggression have been justified? That is another matter; but we might have demanded of Europe whether she had acted in good faith towards us in those treaties through which, abusing the victory they had won, Russia and Germany were immeasurably swollen, while France was reduced to her former curtailed borders. Be that as it may, Monsieur Thiers dared not play his last card; analysing his life, he has never been sufficiently purposeful, and yet it is because he has committed nothing to the game that he should have been able to gamble everything. We are fallen at the feet of Europe: a similar opportunity to rise again may not present itself for some time.

But would it have been right to set the world ablaze once more? A profound question! Nevertheless, the President of the Council’s mistakes being bound up with national feeling, ennoble him.

Ultimately, Monsieur Thiers, to rescue his policy, has reduced France to a space of fifty leagues bristling with fortresses; we will see whether Europe has occasion to smile at this childish behaviour on the part of a great mind.

Behold how, led my by pen, I have dedicated more space to a questionable man of the future than I have to people whose remembrance is certain. It is the unfortunate result of having lived too long: I have entered a sterile epoch in which France faces nothing but meagre generations: Lupa .carca nella sua magrezza: a she-wolf. full in her leanness. These Memoirs diminish in interest with the passage of history, diminish in what they have borrowed from great events; their tail-end, I fear, will be shaped like those of the daughters of Acheloüs. The Roman Empire, announced magnificently by Livy, fades and dies obscurely in the works of Cassiodorus. You were happier, Thucydides and Plutarch, Sallust and Tacitus, when telling of the factions that divided Athens and Rome! You were at least certain to enliven them, not merely by your genius, but by the brilliance of Greek and the gravity of Latin! What can we say of our waning society, we Celts, in our jargon confined to its narrow and barbarous bounds? If these final chapters reproduced our courthouse repetitions, those eternal redefinitions of the law, our fighting over portfolios, would they, fifty years from now, be anything more than the unintelligible columns of an old newspaper? Of a thousand and one conjectures, would a single one prove true? Who can foresee the strange leaps and bounds of the mercurial French spirit? Who knows why its execrations and infatuations, its blessings and curses, transform themselves for no apparent reason? Who can divine why it strays from one political system to another, how, with freedom on its lips and slavery in its heart, it can believe in one version of the truth in the morning and a contrary version by evening? Let us toss a little dust about: like Virgil’s bees, we will cease our battles and fly elsewhere.

Book XLII: Chapter 3: Monsieur de Lafayette

BkXLII:Chap3:Sec1

If by any chance some measure of greatness still stirs here below, our country will continue to slumber. The loins of a decomposing society are fruitless; even the crimes it engenders are still-born, marred as they are by the sterility of their source. The age we are entering is like a tow-path along which generations, fatally condemned, haul the old world towards a world unknown.

In this year of 1834, Monsieur de Lafayette died. I may already have done him an injustice in speaking of him; I may have represented him as a kind of fool, with twin faces and twin reputations; a hero on the other side of the Atlantic, a clown on this. It has taken more than forty years to recognise qualities in Monsieur de Lafayette which one insisted on denying him. At the rostrum he expressed himself fluently and with the air of a man of breeding. No stain attaches to his life; he was affable, obliging and generous.

‘Marquis de Lafayette’

William Russell Birch (British, 1755 - 1834)

Yale University Art Gallery

Under the Empire he was noble and lived quietly; under the Restoration he did not preserve his dignity so effectively; he abased himself inasmuch as he allowed himself to be known as the father of the French Carbonari sections (ventes), and the leader of minor conspiracies; he was fortunate to escape justice at Belfort, as a common adventurer. At the commencement of the Revolution, he kept aloof from the murderers; he fought them weapon in hand and wished to save Louis XVI; but though abhorring the massacres, and obliged though he was to flee them, he found it in himself to praise those scenes where heads were carried along on the ends of pikes.

Monsieur de Lafayette is celebrated because he survived: there is a fame that arises spontaneously based on talent, which death enhances by arresting that talent in youth; there is another kind of fame, a tardy offspring of time, which is the product of age; deficient itself in greatness, it is so because of the revolutions in the midst of which it is placed by chance. The bearer of such fame, by dint of existing throughout, becomes involved in everything; his name becomes the insignia or banner of all: Monsieur de Lafayette will be eternally identified with the National Guard. The results of his actions were, in an extraordinary manner, often in contradiction to his ideas; a Royalist, in 1789 he overthrew a monarchy eight centuries old; a Republican, in 1830 he created a monarchy of the barricades: he was off to endow Philippe with the crown he had taken from Louis XVI. Moulded by events, his image will be found, when the alluvia of our misfortunes settle, embedded in the revolutionary sediment.

His enthusiastic reception in the United States uniquely enhanced his reputation; a nation, rising to salute him, covered him with the glory of its gratitude. Everett ended his speech of 1824 with this apostrophe: ‘Welcome, friend of our fathers, to our shores!...Enjoy a triumph such as never conqueror nor monarch enjoyed. Above all, the first of heroes and of men, the friend of your youth, the more than friend of his country, rests in the bosom of the soil he redeemed. On the banks of his Potomac he lies in glory and in peace. You will re-visit the hospitable shades of Mount Vernon, but him, whom you venerated as we did, you will not meet at its door. But the grateful children of America will bid you welcome in his name. Welcome, thrice welcome, to our shores, and whithersoever throughout the limits of the continent your course shall take you, the ear that hears you shall bless you.’

In the New World, Monsieur de Lafayette contributed to the creation of a new society; in the old world, to the destruction of an old one: freedom invokes him in Washington, anarchy in Paris.

Monsieur de Lafayette had only one idea, and happily for him it was that of the century; the fixity of that idea created his empire; it served to blinker him, it prevented him looking to right or left; he marched with a firm step on a single track; he advanced, without tumbling over precipices, not because he saw them, but because he did not; blindness took the place of genius in him: everything fixed is fatal, and whatever is fatal is powerful.

I can still see Monsieur de Lafayette, at the head of the National Guard, passing, in 1790, along the boulevards to reach the Faubourg Saint-Antoine. On the 22nd of May 1834, I saw him again, lying in his coffin, following the same boulevards. Among the cortege could be seen a band of Americans, each person with a yellow flower in their buttonhole. Monsieur de Lafayette had a quantity of earth transported to the United States sufficient to cover him in his grave, but his plan was not fulfilled.

‘And you shall ask instead of holy oil

A few urns of earth in American soil,

And then return that pillow sublime,

So that after death, his dear remains

Might, in his homeland, own six feet at least

Of free earth in which to sleep.’

In his final moments, forgetting both his political dreams and the romance of his life, he wished to rest at Picpus next to his virtuous wife: death sets everything in order.

At Picpus are interred victims of that Revolution begun by Monsieur de Lafayette; there stands a chapel where they say perpetual prayers in memory of the victims. To Picpus I accompanied Monsieur le Duc de Montmorency, a colleague of Monsieur de Lafayette in the Constituent Assembly; in the depths of the grave the rope twisted that Christian’s bier askew, as if he had turned on his side to pray once more.

I was in the crowd, at the entrance to the Rue Grange-Batelière, when Monsieur de Lafayette’s procession filed past: at the top of the boulevard the hearse halted; I saw it, gilded by a fugitive ray of sunlight, gleaming above the weapons and helmets: then the shadows returned and he vanished.

The multitude flowed by; women selling pastries (plaisirs) cried their wares, vendors of toys, here and there, hawked paper windmills that turned in the same breeze whose sighs had stirred the plumes of the funeral car.

At the session of the Chamber of Deputies on the 20th of May 1834, the President spoke: ‘The name of General Lafayette,’ he said, ‘will remain celebrated in history. In expressing to you the condolences of the Chamber, I add, dear colleague (Georges Lafayette), my personal assurances of affection.’ After these words, the note-taker to the session placed in parentheses the word: (Hilarity).

That is what one of the weightiest of lives is reduced to: hilarity! What remains of the deaths of the greatest men? A grey cloak and a cross of straw, like those over the body of the Duc de Guise, assassinated at Blois.

In earshot of the public news-vendor who, by the railings of the Tuileries Palace, sold the tidings of Napoleon’s death for a sou, I heard two charlatans singing the praises of their Venice treacle (orviétan); and in the Moniteur of the 21st of January 1793, I read these words beneath an account of Louis XVI’s execution:

‘Two hours after the execution, nothing proclaimed that he who was once leader of the nation had just suffered the punishment reserved for criminals.’ Following those words this announcement appeared: ‘Ambroise, a comic opera.’

The last actor in a drama played for fifty years, Monsieur de Lafayette was left behind on stage; the final chorus of the Greek tragedy proclaims the moral of the piece: ‘Learn, blind mortals, to turn your gaze on the last hour of life.’ And I, a spectator seated in an empty theatre, its boxes deserted, its lights extinguished, I alone, of all my age, remain before the lowered curtain, in silence and the night.

Book XLII: Chapter 4: Armand Carrel

BkXLII:Chap4:Sec1

Armand Carrel threatened Philippe’s future, as General Lafayette haunted his past. You know how I came to know Monsieur Carrel; since 1832 I never ceased to communicate with him until the day I followed him to the Saint-Mandé cemetery.

‘Armand Carrel’

Histoire de la Révolution Française Depuis 1814 Jusqu'à 1830...Revue et Continuée par M. Auguis, Vol 04 - Jacques Antoine Dulaure (p998, 1838)

The British Library

Armand Carrel was anxious; he began to fear that the French were incapable of any rational feeling for freedom; he had some presentiment of the brevity of his life: as something on which he could not count and to which he attached scant worth, he was always ready to risk that life on a throw of the dice. If he had died in his duel with young Laborie, over Henri V, his death would have been in a great cause at least, and in itself a noble drama; his funeral would probably have been honoured by violent demonstrations; yet he has left us because of a wretched quarrel not worth a hair of his head.

He was in one of his innate fits of melancholy when he inserted an article in the National to which I replied in this note:

‘Paris, 5th of May 1834.

Monsieur, your article is full of that sensitive feeling for situations and conventions which elevates you above all the other political writers of our day. I do not speak of your rare talent; you know that, even before I had the honour of meeting you, I rendered it full justice. I will not thank you for your praise; I like to think it is due to what I regard now as an old friendship. Sir, you are rising higher; you are becoming more isolated as all men do who are made for great things; gradually the crowd, which cannot follow, deserts them, and they are seen all the more clearly for standing apart.

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

I sought to console him in another letter of the 31st of August 1834, after he had been condemned for a Press offence. I received this reply; it displays the man’s opinions, regrets and hopes.

‘TO MONSIEUR LE VICOMTE DE CHATEAUBRIAND.

Sir,

Your letter of the 31st of August was only passed to me on my arrival in Paris. I would have thanked you earlier, if I had not been forced to spend the little time allowed me by the police, who were informed of my return, in preparations for my entering prison. Yes, Monsieur, here I am, condemned to six months in prison by the magistrates, for an imaginary offence and in virtue of an equally illusory law, because the jury intentionally dismissed the charge against me, on the most substantial accusation, after a defence which, far from attenuating my guilt in speaking the truth to Louis-Philippe, aggravated that crime by establishing it as the right of the entire opposition Press. I am pleased that the difficulties of so bold a thesis, in times like these, seemed to have been virtually overcome by that defence, which you have read, and in which it benefited me to invoke the authority of that book with which, eighteen years ago, you educated your own party as to the principles of constitutional responsibility.

I often ask myself sadly what end writings such as yours have served, Monsieur, and those of the most eminent leaders of public opinion to whom I myself belong, when that concurrence of the noblest intellects in the land, in constant defence of the laws of free speech, has not resulted for the mass of thinkers in France in a party determined from now on under all regimes, to demand from whatever politics may be victorious, freedom of thought, speech and writing, as the prime responsibility of whichever legitimate authority is in power. Is it not true, Monsieur, that when you demanded, under the previous government, total freedom of debate, it was not for the sake of the temporary benefit that your political friends might accrue, in their opposition to adversaries who had become masters of the power of intrigue? Some used the Press thus, as has indeed been shown since; but you, Sir, you demanded freedom of debate for the whole of society, a forum, and general protection, for all ideas past or current; it is that which has earned you, Sir, the recognition and respect of those thinkers whom the July Revolution brought fresh to the lists. That is why our work is linked to yours, and why we quote your writings, less as admirers of the incomparable talent that produced them than as aspirants from afar to the continuation of the same task, young soldiers as we are of a cause in which you are the most glorious of veterans.

What you have desired for thirty years, Monsieur, and what I would wish, if I am allowed to name myself alongside you, is to guarantee, to the interests that share in our noble France, more humane rules of engagement, laws more civilised, more fraternal, more decisive than civil war, and only debate can prevent civil war. When shall we succeed in replacing faction by ideas, and intrigue, egotism and greed by legitimate and worthy interests? When shall we see persuasion, and the word, control those inevitable transactions that the duelling of parties and the shedding of blood wearily bring about, but too late for the dead of both camps, and too often without benefit to the wounded survivors? As you have said, sadly, Monsieur, it seems that much that was learnt has been forgotten and that in France no one knows, any longer, what it costs to shelter beneath a tyranny promising silence and peace. Nevertheless we must continue to speak, write and publish; unforeseen benefits sometimes emerge from constancy. And, Sir, of all the fine examples you have given us that which is most constantly before my eyes is comprised in the single word: Persevere.

Accept, Sir, the feelings of undying affection with which I am happy to sign myself,

Your most devoted servant, A. CARREL.

Puteaux, near Neuilly, the 4th of October 1834.’

BkXLII:Chap4:Sec2

Monsieur Carrel was imprisoned at Sainte-Pélagie; I went to see him there two or three times a week: I found him standing at the bars of his window. He reminded me of his neighbour, a young African lion in the Jardin des Plantes: motionless behind the bars of his cage, that scion of the desert allowed his vague and melancholy gaze to wander over the objects outside; it was obvious he would not live. Then we went downstairs, Monsieur Carrel, and I; the servant of Henri V walked with the enemy of kings in a damp courtyard, sombre, narrow, and surrounded by high walls like a well. There were other Republicans walking up and down the courtyard too: young and ardent revolutionaries, with moustaches, beards, long hair, German or Greek caps, and pallid faces, looking about, with a threatening aspect, and the cast of ancient souls in Tartarus before their emergence to the light: they were ready to burst back into life. Their clothes acted on them as a uniform does on a soldier, like Nessus’ blood-stained shirt on Hercules: they represented a vengeful world hidden behind current society and prepared to make it tremble.

In the evenings they gathered in their leader, Armand Carrel’s, room; they talked about what they would do when they came to power, and the necessity of shedding blood. Debates took place about the mighty citizens of the Terror: some, partisans of Marat, were atheists and materialists; others, admirers of Robespierre, adored that new Christ. Did not Saint Robespierre say, in his speech on the Supreme Being, that belief in God gave the strength to brave misfortune, and that innocence on the scaffold would make the tyrant in his triumphal chariot grow pale? The equivocation of an executioner speaking tenderly of God, misfortune, tyranny, the scaffold in order to persuade men that he was only slaying the guilty, and indeed as an act of virtue; an anticipation of those miscreants, who, sensing the approach of punishment, stand like Socrates before the judge, seeking to ward off the blade by threatening him with their innocence!

His stay in Sainte-Pélagie did Monsieur Carrel harm: imprisoned with those ardent spirits, he contested their ideas, berated them, and defied them, nobly refusing to celebrate the 21st of January; but at the same time he was made irritable by suffering and his powers of reason were weakened by the murderous sophisms that rang in his ears.

Mothers, sisters, young men’s wives came to care for him each morning and carry out the domestic tasks. One day, passing through the dark corridor that led to Monsieur Carrel’s room, I heard a delightful voice coming from a neighbouring cell: a lovely woman hatless, hair unbound, sitting on the edge of a pallet bed, mending the tattered garments of a kneeling prisoner, who seemed less a captive of Philippe than of the woman at whose feet he was enchained.

Freed from captivity, Monsieur Carrel came in turn to visit me. A few days before his end, he came to bring me an issue of the National in which he had taken pains to include an article on my Essais sur la littérature anglaise, where he quoted with excessive praise the pages that terminate the Essais. Since his death, I have been sent this article in his own hand, which I will keep as a pledge of his friendship. Since his death! What words I have just traced without thinking!

Despite being an essential supplement to the law which does not recognise crimes of honour, duelling is dreadful, especially when it destroys a life full of promise and deprives society of one of those rare individuals who only appears after a century of effort, in the wake of certain ideas and events. Carrel fell in the woods that saw the Duc d’Enghien fall: the shade of the great Condé’s descendant served as the famous commoner’s witness and bore him away. Those fatal woods have twice made me weep: at least I cannot reproach myself for any lack of essential sympathy or grief engendered by those two catastrophes.

Monsieur Carrel, who, in other encounters, never thought of death, thought of it before this: he spent the night writing his last testament, as if he had been forewarned of the result of the duel. At eight in the morning, on the 22nd of July 1836, he went, swift and keen, to those leafy shadows at the very hour when the deer are at play.

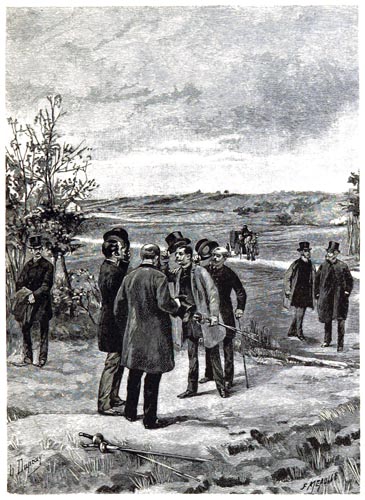

‘Meeting of the Seconds’

The Praise of Paris...Illustrated - Theodore Child (p167, 1893)

The British Library

Placed at the measured distance, he walked rapidly forward, and fired without flinching, as was his custom; he seemed never to have enough of danger. Wounded to death and supported in his friends’ arms, as he passed before his adversary who was himself wounded, he said: ‘Are you much hurt, Sir?’ Armand Carrel was as thoughtful as he was intrepid.

On the 22nd, it was late when I heard of the incident; on the morning of the 23rd, I went to Saint-Mandé; Monsieur Carrel’s friends were extremely anxious. I wanted to enter, but the surgeon advised me that my presence might excite the dying man too much and extinguish the feeble ray of hope that still remained. I withdrew in consternation. On the following day, the 24th, Hyacinthe whom I had sent on ahead, came to tell me that the unfortunate young man had died at five-thirty, after having experienced severe pain: life despite all its efforts had lost its desperate struggle with death.

The funeral took place on Tuesday the 26th. Monsieur Carrel’s father and brother had arrived from Rouen. I found them shut in a little room with three or four of the closest friends of the man whose loss we deplored. They embraced me, and Monsieur Carrel’s father said: ‘Armand should have remained a Christian like his father, mother, brothers and sisters: the needle has but a few hours to move before reaching the final point on the dial.’ I will regret forever not having seen Carrel on his death-bed: I would not have despaired, at the supreme moment, of helping the needle travel that space beyond which it might have reached Christ’s hour.

Carrel was not as anti-religious as has been suggested: he had doubts; when from firm disbelief one passes to indecision, one is quite near to certainty. A few days before his death, he said: ‘I would give all this life to believe in the other.’ In giving an account of Monsieur Sautelet’s suicide he wrote these forceful paragraphs:

‘I have been able in thought to extend my life to that instant, rapid as lightening, when the sight of objects, motion, sound, and feeling shall escape me, and in which the last efforts of my spirit shall gather to form the idea: I am dying; but for the minute, the second that follows immediately upon that, I have always felt an indefinable horror; my imagination always refuses to distinguish anything further. To plumb the depths of hell seems a thousand times less fearful than that universal uncertainty:

“To die, to sleep,

To sleep! Perchance to dream!”

‘I have seen how all men, whatever their strength of character or belief, own to that same impossibility of going beyond their last earthly impression, and the mind is lost there, as if in arriving at that boundary you find yourself suspended above a ten thousand foot precipice. You dispel that fearful sight in order to go out and fight a duel, attempt an attack on a redoubt, or confront a stormy sea; you even appear to scorn life; you adopt a confident expression, calm and contented; but it is because your imagination holds out to you victory rather than death; it is because the mind dwells less on danger than on the means of escaping it.’

These words on the lips of a man destined to die in a duel are noteworthy.

In 1800, when I returned to France, I was ignorant of the birth of one of my friends in that land where I disembarked. In 1836, I saw that friend descend into the grave without those consolations of religion whose memory I brought to my country in the first year of the century.

I followed the coffin from the mortuary to the burial place; I walked next to Monsieur Carrel’s father and gave my arm to Monsieur Arago: Arago has measured the heavens I have sung.

Arriving at the gate of the little rural cemetery, the convoy halted; speeches were pronounced. The absence of the cross told me that the sign of my grief must remain buried in the depths of my soul.

Six years previously in the July Days, passing before the colonnade of the Louvre, near an open ditch, I met those young men who carried me off to the Luxembourg where I was to protest in support of a monarchy which they had just toppled; six years later, I returned, on the anniversary of the July celebrations, to associate myself with the sorrow of those young Republicans, as they had associated with my loyalty. Strange destiny! Armand Carrel sighed out his last breath at the house of an officer of the Royal Guard, who had not sworn the oath to Philippe; a royalist and a Christian, I had the honour of bearing a corner of the shroud which covers those noble remains but cannot hide them.

Many kings, princes, ministers, men who thought themselves powerful, have passed before me: I did not deign to raise my hat to their coffin or dedicate a word to their memory. I have found more to study and describe in the intermediate ranks of society than in those whose livery is displayed; a piece of silk embroidered with gold is not worth the fragment of flannel that the ball drove into Carrel’s chest.

Carrel, who remembers you? Only the mediocrities and cowards do, whom your death has freed from their fear of your superiority, and I who did not share your views. Who thinks of you? Who recollects you? I congratulate you on having completed that journey, with a single step, whose trajectory when prolonged becomes so sickening and empty, on having brought the goal of your travels within range of a pistol-shot, a distance which still seemed too great to you, and which you shortened by advancing to a mere sword’s length.

I envy those who have departed before me: like Caesar’s soldiers at Brundisium, I gaze at the open sea from the cliff-heights and look towards Epirus to see if I can glimpse the vessels that transported the earlier legions returning to carry me off in my turn.

A few days after the funeral, I went to Monsieur Carrel’s house: the apartment was shut: when the shutters were opened, the daylight which could no longer reach the absent owner’s eyes, flooded the deserted rooms. My heart was heavy contemplating his books, his table, which I have bought, his pen, the insignificant words scribbled at random on a few scraps of paper; everywhere traces of life, and death everywhere.

A person dear to Monsieur Carrel uttered not a word; she was sitting on a sofa, I sat down next to her. A little dog came to gaze at us. Then the young woman burst into tears. Pushing back the hair from her brow and seeking to gather her thoughts, she said: ‘You wish to see Monsieur Carrel?’

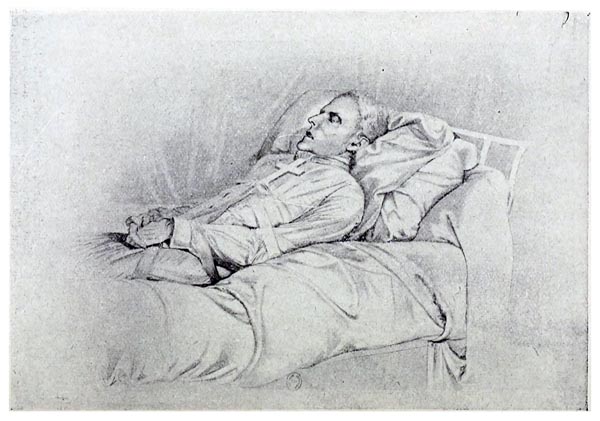

She rose, took up a picture covered by a cloth, removed the cloth and revealed a portrait of the unfortunate man drawn by Monsieur Scheffer a few hours after death. ‘When I saw him dead,’ the young woman said: ‘he was disfigured by his final agony; his face softened afterwards, and Monsieur Scheffer told me his smile looked like that.’ The portrait, a striking resemblance indeed, revealed something of the martyr, sombre and energised, but the mouth smiled sweetly as if the dead man smiled at being freed from this life.

She who would have married Carrel some day, covered up the portrait once more and added: ‘It would be well if you could give me a letter that I could show my relatives; they would be happy if you esteem me: I could use it in my defence.’

In order to try and distract her, I spoke about the papers Monsieur Carrel had left behind. ‘There they are,’ she said, ‘he had a great affection for you, Monsieur, and he valued very few people and kept only a handful of letters, there are not many here, some letters from yourself, and then a letter from his mother which he kept because of its harshness.’

I left that unfortunate house: from then on vainly I have thought myself incapable of sharing young women’s sorrows, since the years besiege and chill me; I force a way through them with difficulty, as the cabin-dweller in winter is obliged to open a path through the fallen snow at his door to seek out a ray of sunlight.

Having re-read this in 1839, I will add that having visited Monsieur Carrel’s tomb in 1837, I found it quite neglected, but I saw a black wooden cross that his sister Nathalie had planted near the grave. I paid Vaudran, the gravedigger, the eighteen francs still owing for the metal railings; I asked him to take care of the site, lay some turf and grow some flowers there. I go to Saint-Mandé as the seasons alter, to pay the fee and reassure myself that my intentions have been faithfully executed.

Book XLII: Chapter 5: VARIOUS WOMEN: A Lady from Louisiana

BkXLII:Chap5:Sec1

Preparing to complete my collection of portraits, and casting a glance around me, I glimpse various women I have involuntarily neglected; angels grouped at the foot of my painting, they lean on the frame to view the end of my life.

In the past I have met women variously known and celebrated. Women today are altered in manner: for the better or for the worse? It is simply that I incline towards the past; but the past is clothed with a mist in which objects take on a complexion pleasant but often deceptive. My youth, to which I cannot return, has left with me impressions of my grandmother; I barely remember her and should be delighted to see her again.

A lady from Louisiana arrived from the Mississippi to see me: I thought I was meeting the virgin of last love. Célestine wrote me several letters; they might have been dated the Moon of flowers; she showed me fragments of her memoirs composed in the savannahs of Alabama. Some time later, Célestine wrote saying that she was dressing for her presentation at Philippe’s court: I had donned my bearskin. Célestine had been changed into an alligator from the Florida swamps: may Heaven bring her peace and love, as long they endure!

Book XLII: Chapter 6: Madame Tastu

BkXLII:Chap6:Sec1

There are people who, interposed between you and the past, prevent your memories surfacing; there are others who immediately remind you of what you once were. Madame Tastu produced this latter impression. Her mode of speech is natural; she has abandoned Gallic patois to those who seek to appear younger by hiding in our ancestor’s costume. Favorinus told a Roman who affected the Latin of the Twelve Tables: ‘Are you trying to communicate with Evander’s mother?’

Voyage en France par Mme A. Tastu - Madame Sabine Casimire Amable (p479, 1852)

The British Library

Since I have touched on antiquity, I will say a few words of the women of those days while descending the scale towards our own day. Greek women were sometimes celebrated philosophers; more frequently they followed another divinity: Sappho remains the immortal sibyl of Gnidus; no more is known of Corinne after her conquest of Pindar; Aspasia taught Socrates about Venus:

‘Socrates, accept my teaching. Fill yourself with poetic inspiration: with its powerful charms you will learn to bind what you love; you shall enchain with the music of the lyre, bearing to the heart through the ear the living form of passion.’

The Muse’s sigh, passing over the women of Rome without leading them to create, animated Clovis’ nation, as yet in its cradle. The langue d’Oïl had its Marie de France; the langue d’Oc its Dame de Die, who, in her castle of Vaucluse, sang of her cruel lover.

‘I would know, my fine and handsome lover, why you treat me so cruelly, and so savagely: per que m’etz vos tan fers, ni tan salvatage.’

The Middle Ages transmitted such songs to the Renaissance. Louise Labé wrote:

‘Oh! Would I were snatched away into the lovely breast

Of him for whom I go languishing!’

Clémence de Bourges, nicknamed the Eastern Pearl, who was buried with her face uncovered and her head crowned with flowers because of her beauty, the two Marguerites and Mary Stuart, all three of them queens, expressed simple frailties in simple language.

I had an aunt about the time of our Parnassian era, Madame Claude de Chateaubriand; but I am more embarrassed by Madame Claude than by Mademoiselle de Boisteilleul. Madame Claude, disguised under the name of The Lover, addresses seventy sonnets to a mistress. Reader, pardon my aunt Claude’s twenty-two years: parcendum teneris: be indulgent to youth. If my aunt Boisteilleul was more discrete, well, she was seventy-seven when she sang, and the traitor Trémigon appeared to her aged thoughts as a warbler as much he did a Sparrow-hawk. Be that as it may, here are a few lines of Madame Claude’s, which truly set her among the ancient poetesses:

SONNET LXVI

‘Oh, in love how strangely am I treated,

Since I dare not show my love’s truth plain,

Nor of my hardships dare to you complain,

Nor demand of you what I wish so deeply!

The eye then must serve me as a tongue,

Thus to ensure that I proclaim my song.

Hear, if you can, what I say with the eye.

Sweet invention, could you but find a way

To hear with the eyes what the eyes do say

The word that I am not bold enough to cry!

As the language became fixed, freedom of feeling and thought became restricted. There is barely a memory of that Madame Deshoulières, of Louis XIV’s day, over-praised and over-neglected. The elegy was maintained as a form through female sorrow, during Louis XV’s reign and into that of Louis XVI, when the grand elegies of the people commenced: the old school ended with Madame de Bourdic, now little known, yet who left us a noteworthy Ode to Silence.

The new school has cast its thought in another mould: Madame Tastu walks amidst the choir of modern women poets, in prose or verse, Allart, Waldor, Desbordes-Valmore, Ségalas, Revoil, Mercoeur etc: Castalidum turba: the Castalian throng. Must it not be regretted that they have failed, as regards the example given by the Aonides, to celebrate that passion which, according to antiquity, brightened Cocytus’ brow, and made him smile at Orpheus’ sighs? At Madame Tastu’s gatherings, love only speaks in hymns borrowed from foreign tongues. That reminds me of what is recounted of Madame Malibran: when she wanted to know the name of a bird she had forgotten she imitated its song. From the verse of several Maeonides, there breathe the regrets of women who, feeling time steal upon them, wish to hang their harp up as an offering: one would wish to rid them of the former and keep the latter in their hands! An indefinable complaint issues from our lives: the years are a long sad lament with one refrain.

Book XLII: Chapter 7: Madame Sand

BkXLII:Chap7:Sec1

I thanked Madame Dudevant, otherwise known as George Sand, for having mentioned René in the Revue des Deux Mondes; she did not reply. Some time later she sent me Lélia, and I did not reply! Soon a brief exchange, in the form of an explanation, took place between us.

‘I dare to hope that you will forgive me for not having replied to the flattering letter you were so good as to write me when I mentioned René, on the re-publication of Oberman. I know not how to thank you for all the kind expressions you have employed in regard to my work.

I have sent you Lélia, and sincerely hope that she will gain from you the same protection. The greatest privilege of an accepted and universal fame such as yours is to gather together, and encourage the debut of, inexperienced writers for whom there is no lasting success without your patronage.

Accept the assurance of my deepest admiration, and believe me, Monsieur, one of your most loyal followers.

‘GEORGE SAND.’

At the end of October 1834, Madame Sand made me the present of a copy of her new novel, Jacques: I accepted the gift.

‘30th October 1834.

Madame, I hasten to offer you my sincerest thanks. I will read Jacques in the Forest of Fontainebleau or by the seashore. When I was younger, I would have been less brave; but my age will defend me from solitude, without detracting from the passionate admiration I profess for your talent and which I conceal from none. You have, Madame, given new prestige to that city of dreams from which I once left for Greece with a world of illusions: returning to his point of departure, René lately, on the Lido, paraded his regrets and his memories, between Childe-Harold who had vanished, and Lélia who was about to appear.

‘CHATEAUBRIAND.’

Madame Sand possesses a talent of the first order; her descriptions have the verisimilitude of Rousseau in his reveries, and Bernardin de Saint-Pierre in his Études. Her clear style is not flawed by any of the faults of the day. Lélia, painful to read, and lacking the delightful scenes of Indiana and Valentine, is nevertheless a masterpiece of its kind: extreme in nature, it is without passion, and yet disturbs one like a passion; soul is absent from it, and yet it weighs on the heart; depravity of maxim, abuse of moral rectitude, could go no further; but over this abyss the author casts her talent. In the vale of Gomorrah, dew falls by night over the Dead Sea.

Madame Sand’s works, her novels, the poetry of matter, are born of the age. Despite her superiority it is to be feared lest the author has, by the very nature of her writings, limited her circle of readers. George Sand will not suit all ages. Of two men, equal in genius, of whom one preaches order and the other disorder, the former will attract the greater audience: the human race denies universal applause to whatever harms morality, the pillow on which weakness and justice can rest; the books which cause our first blushes, and whose text has not been learnt by heart on emerging from the cradle, will hardly be associated with all our life’s memories; books only read in hiding, which have not been our sworn and cherished friends, which are part neither of the candour of our feelings, nor the integrity of our innocence. Providence has enclosed that success which does not have its source in the good, in narrow limits; and given universal glory to whatever encourages virtue.

‘Jeanne, lui Dit la Jeune Gracieus Châtelaine’

Œuvres illustrées de George Sand - George Sand (p282, 1852)

Internet Archive Book Images

I reason here, I know, as a man whose narrow-minded view fails to embrace the vast horizon of Humanity, as a man of the past, attached to a risible morality: an obsolete morality of long ago, at very best suitable only for unenlightened spirits, in society’s infancy. A new Gospel is constantly being born far beyond the commonplaces of that conventional wisdom which arrests the progress of the human species, and prevents the restoration of that impoverished body, so calumniated by the soul. When women run about the streets; when it suffices, for a marriage, to open a window and call God to the wedding as witness, priest and guest: then all modesty is destroyed; espousals will be everywhere and people will rise, like doves, to the heights of nature. My criticism of the genre in which Madame Sand writes has no value then, other than as part of the vulgar order of things past; thus I trust she will not be offended by it: the admiration I profess for her must excuse remarks which owe their origin to the misfortune of my age. In the past I would have been swept away more by the Muses; those daughters of heaven were once my sweet mistresses; today they are no more than old friends: they keep me company of an evening at the fireside, but leave me swiftly; because I go to bed early, and they go to watch over Madame Sand’s hearth.

Doubtless in this way she will display her intellectual omnipotence, and yet she will please less because she will be less original; she will think to augment her power by entering the depths of reveries beneath which we lie buried, we, the vulgar and deplorable: but she will be wrong: since she is far above that extravagance, that vagueness, that presumptuous nonsense. At the same time as a rare, but over-flexible, skill should be alerted to superior folly, it should also be warned that the penning of fantasies, intimate portraiture (as the jargon has it), is limited, that its source is in youth, that every instant its flow reduces, and that after a certain number of works, one ends in feeble repetition.

Is it so certain that Madame Sand will always take the same delight in what she now creates? Will not the merit and understanding of the passions of twenty be lowered in her estimation, as the works of my own youth have depreciated in mine? Only the works of the ancient Muse never alter, sustained as they are by a nobility of manners, beauty of language, and majesty of feeling belonging to the whole human race. The fourth book of the Aeneid will remain forever open to human admiration, because it is suspended in the heavens. The fleet which brings the founder of the Roman Empire; Dido the founder of Carthage stabbing herself after having predicted Hannibal’s birth:

‘Exoriare aliquis nostris ex ossibus ultor;

From my bones may some avenger rise.’

Love making the rivalry between Rome and Carthage spurt from his torch, then setting fire with his flame to the funeral pyre whose blaze the fleeing Aeneas saw reflected on the waves, is all quite different from a dreamer walking through a wood, or a libertine vanishing by drowning himself in a lake. Madame Sand will, I hope, wed her talent one day to subjects as durable as her genius.

Madame Sand will only be converted by the preaching of that missionary with the bald head and white beard, called Time. A less austere voice currently holds the poet’s ear captive. Now, I am persuaded that Madame Sand’s talent is partially rooted in corruption; she would be commonplace if she were modest. It would be otherwise if she had permanently resided in that sanctuary unfrequented by men; her power of love, restrained and hidden beneath a virginal fillet, would have drawn from her breast those seemly melodies which belong to woman and the angels. However that may be, audacity in doctrine and voluptuousness in morals represent ground not yet tilled by a daughter of Adam, who, given over to feminine culture, has produced a harvest of unknown flowers. Let us suffer Madame Sand to give birth to such perilous marvels till winter approaches; she will sing no more when the North Wind blows; while waiting let us hope that, less lacking in foresight than the Cicada, she will make provision of her glory for the day when a dearth of pleasure strikes. Musarium’s mother told him: ‘You will not be eighteen forever. Will Chaereas always remember his vows, tears, and kisses?

Furthermore, many women have been seduced as if transported by their youth; nearer autumn, retreating to the maternal hearth, they have added a sombre or plaintive string to their cithara with which to express religion or misfortune. Old age is a traveller by night; the earth is hidden from it, it only sees the heavens glittering above its head.

I have not met with Madame Sand dressed as a man, or wearing the blouse and carrying the iron-shod staff of a mountaineer: I have not seen her drink of the Bacchantes’ cup, or smoke indolently while seated on a sofa like a Sultana: natural or affected idiosyncrasies which for me add nothing to her charm or genius.

Is she any more inspired, when she makes a cloud of vapour rise from her lips to wreathe her hair? Did Lélia escape from her mother’s brain as a puff of smoke, as Sin emerged in a wreath of flame from the head of the guilty Archangel, according to Milton? I do not know who passes to the sacred courts; but down here, Nemea, Phila, Lais, the spiritual Gnathene, Phryne, who made Apelles despair of his brush, Praxiteles of his chisel, Leaena who was loved by Harmodius, the two sisters surnamed Aphyes, because they were small and large-eyed, Doricha, whose hair-ribbon and scented robe were consecrated in Venus’ temple, all those enchantresses, in the end, knew only Arabia’s perfumes. Madame Sand, on her side, has, it is true, the authority of the Odalisques and young Mexican girls who dance with cigars between their lips.

What effect has the sight of Madame Sand had on me, following that of the few gifted women, and many delightful women whom I have known, following that of those daughters of the earth, who like Madame Sand said with Sappho: ‘Come, Mother of Love, to our delicious banquets, fill our cups with the nectar of roses?’ In my addressing now fiction now reality, the author of Valentine has made on me two very different impressions.

Regarding fiction I shall not speak, since I ought no longer to understand its language; regarding reality, as a man of mature age, cherishing notions of propriety, attaching as a Christian the highest value to the virtue of modesty in women, I have no idea how to express my unhappiness at such qualities bestowed on those prodigal and faithless hours that are consumed only to vanish.

Book XLII: Chapter 8: Monsieur de Talleyrand

Paris, 1838.

BkXLII:Chap8:Sec1

In the spring of this year, 1838, I was occupied with The Congress of Verona, which I was obliged to publish according to the terms of my literary contract: I have spoken of it in the appropriate place in these Memoirs. A man has died; that guardsman of the aristocracy follows the powerful plebeians who have already vanished.

When Monsieur de Talleyrand first appeared on the stage of my political career, I spoke a few words to him. Now his whole existence is revealed to me by his last hour, in accord with that fine saying of the ancients.

I had dealings with Monsieur de Talleyrand; as a man of honour I was loyal to him, as you have seen, especially regarding the falling-out at Mons, when I sacrificed myself freely for him. Quite simply, I shared in disagreeable things that happened to him, and I pitied him when Maubreuil slapped his face. There was a time when he pursued me in a charming manner; he wrote to me at Ghent saying, as you have read, that I was a strong man; when I was lodging at the house on the Rue des Capucines, he sent me, with perfect gallantry, a Foreign Office seal, a talisman engraved no doubt under the sign of his constellation. Perhaps it was because I did not abuse his generosity that he became my enemy without any provocation on my part, when I achieved a little success which was not his work. His remarks travelled the world and failed to offend me since Monsieur de Talleyrand could not have offended anyone; but his intemperate language absolved me, and since he allowed himself to criticise me, he left me free to employ the same right in his regard.

Monsieur Talleyrand’s vanity deceived him; he mistook his status for genius; he thought himself a prophet in fooling everyone: his authority regarding future events was worthless: he saw nothing in advance, he only saw in retrospect. Lacking insight and the light of conscience he revealed nothing that superior intellect can, he valued nothing that probity does. He took a leading part in chance events, when those events, which he never foresaw, had occurred, but only on his own behalf. He was ignorant of that breadth of ambition, which submerges personal interests in public glory as the treasure most profitable to private interest. Monsieur de Talleyrand did not belong then to that class of beings fitted to become fantastic creations around which public opinion, deceived or disappointed, is forever weaving its fantasies. Nevertheless it is certain that various sentiments, in sympathy with diverse ideas, worked to create an imaginary Talleyrand.

Firstly that kings, governments, former foreign ministers, and ambassadors were erstwhile dupes of this man, and incapable of grasping him, is proof that they merely obeyed a higher reality: they would have doffed their hats to Bonaparte’s kitchen-boy.

Then, the members of the old French aristocracy linked to Monsieur de Talleyrand were proud to have a man among their ranks who was so kind as to reassure them of its importance.

Finally, the revolutionaries and the generations without morals, while ranting against titles, have a secret leaning towards aristocracy: these curious converts willingly seek baptism and think to acquire fine manners by it. At the same time, the Prince’s dual apostasy delighted the young democrats’ pride in another way: since they concluded from it that their cause was just, and that noblemen and priests are quite contemptible.

Whatever we make of these obstacles to the light, Monsieur de Talleyrand was not great enough to create a lasting illusion; he had not within him enough power of belief to turn his lies into heightened stature. He was seen too clearly; he will not live, because his life was linked neither to a national idea that has survived him, nor a celebrated action, nor peerless talent, nor some useful invention, nor some epoch-making concept. Remembrance with regard to virtue is denied him; danger did not even deign to honour his days; he spent the reign of Terror outside the country, he only returned when the forum transformed itself into the antechamber.

Diplomatic records prove Talleyrand’s mediocrity: you cannot cite an action of any worth which is due to him. Under Bonaparte, none of the important negotiations were his; when he was free to act alone he let the opportunity slip and marred what he touched. It is well attested that he brought about the death of the Duc d’Enghien; that bloody stain cannot be effaced: far from having pursued the Minister in my account of the prince’s death, I have been too lenient with him.

In his statements in defiance of the truth, Monsieur de Talleyrand displayed fearful effrontery. I have not spoken, in the Congress of Verona, of the speech which he made to the Chamber of Peers relative to my address regarding the War in Spain; his speech began with these solemn words:

‘It is sixteen years ago now that, summoned by the man who governed the world at that time, to give him my advice on engaging in conflict with the Spanish people, I had the misfortune to displease him by unveiling the future, by revealing to him all the host of dangers which would ensue from an aggressive action no less unjust than foolhardy. Disgrace was the fruit of my sincerity. A strange fate it is that brings me, after such an extent of time, to make the same effort, and to offer the same counsel, to a legitimate sovereign!’

There are fits of forgetfulness or deceit which terrify: you open your ears, you rub your eyes, not knowing whether you are awake or asleep. When the imperturbable individual to whom you owe such assertions descends from the rostrum and takes his seat impassively, you follow him with your gaze, suspended as you are between a kind of astonishment and a sort of admiration; you are unsure whether the man has not received some authority from nature giving him the power to recreate or annihilate the truth.

I did not reply; it seemed to me that the shade of Bonaparte would rise to speak, and repeat the terrifying rebuttal he had once given Monsieur de Talleyrand. Witnesses to that scene were still sitting among the Peers, including Monsieur le Comte de Montesquiou; the virtuous Duc de Doudeauville recounted it to me, having heard it from the lips of that same Monsieur de Montesquiou, his brother-in-law; Monsieur le Comte de Cessac, present at the time, repeated his account of it to whoever would listen: he had thought that on leaving the room, the Grand Elector would be arrested. Napoleon, in his anger, shouted at his whey-faced Minister: ‘That’s fine, for you to speak against the Spanish War, you who advised it, you from whom I have a pile of letters in which you sought to prove to me that such a war was as necessary as it was politic.’ Those letters vanished when the archives were removed from the Tuileries in 1814.

Monsieur de Talleyrand in his speech claimed that he had the misfortune to displease Bonaparte by unveiling the future, by revealing all the dangers which would ensure from an act of aggression no less unjust than foolhardy. Let Monsieur de Talleyrand console himself in his tomb, he had not that misfortune; he need not add that calamity to his life’s afflictions.

Monsieur de Talleyrand’s principal crime regarding the Legitimacy was to turn Louis XVIII away from the idea of concluding a marriage between the Duc de Berry and a Russian princess; Monsieur de Talleyrand’s inexcusable crime regarding France was to have agreed to the disgusting Treaty of Vienna.

The result of Monsieur de Talleyrand’s negotiations was to leave us without proper frontiers: the loss of a battle at Mons or Coblenz would lead in a week to enemy cavalry deploying beneath the walls of Paris. Under the old monarchy, not only was France encircled by a ring of fortresses, but she was protected on the Rhine by the independent States of Germany. An invasion of the Electorates or agreement with them was needed to approach us. On another front, Switzerland remained free and neutral; it possessed few roads; nothing would violate its territory. The Pyrenees were impassable, guarded by the Spanish Bourbons. Monsieur de Talleyrand understood none of this; such are the crimes that will condemn him forever as a statesman: crimes that robbed us in a day of Louis XIV’s labours and Napoleon’s victories.