François-René de Chateaubriand

Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem et de Jérusalem à Paris

(Record of a Journey from Paris to Jerusalem and Back)

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2011 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Part Four: Jerusalem

I occupied myself for several hours scribbling notes on the places I had seen; a manner of proceeding which I pursued during my entire stay in Jerusalem, exploring by day and writing by night. The Father Procurator visited me, early in the morning of the 7th of October; he told me the outcome of the disagreement between his Father Superior and the Pasha. We agreed what we must do. My firmans were sent to Abdallah. He lost his temper, shouted, threatened, but finished however by demanding a slightly lower amount from the monks. I regret being unable to give here a copy of a letter written by Father Bonaventura da Nola to General Sébastiani; I received the copy from Father Bonaventura himself. It contains, along with the tale of the Pasha, comments which are as much to the credit of France as they are to General Sébastiani. But I could not publish the letter without the permission of the person to whom it is written, and unfortunately the general’s absence robs me of all means of obtaining that permission.

It took all my desire to be as helpful as possible to the Fathers of the Holy Land to occupy myself with anything other than visiting the Holy Sepulchre. I left the monastery that very day, at nine in the morning, accompanied by two monks, a dragoman, my servant and a Janissary. I went on foot to the church that contains the tomb of Jesus Christ.

Every traveller has described this church, which is the most venerable on earth whether one considers the matter as philosopher or simply as a Christian. Here I encounter a real embarrassment. Should I give an exact description of the holy places? But then I will merely be repeating what others have said before me: never was a subject perhaps less well known to modern readers, and yet never was a subject more utterly exhausted. Should I omit a portrait of those sacred places? But would that not remove the most essential part of my journey, and defeat its end and purpose? After considering the matter for a long time, I am determined to describe the principal Stations of Jerusalem, for the following reasons:

l. No one reads about former pilgrimages to Jerusalem nowadays; and what was once very familiar is likely to appear quite new to most readers;

2. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is no more; it was burned to the ground (in 1808) since my return from Judea: I am, so to speak, the last traveller to have seen it; and can act, for that very reason, as its last historian.

But as I have no ambition to retouch a picture that has already been very well painted, I will profit from the works of my predecessors, taking care only to clarify them by means of my own observations.

Among these works, I would have preferred to choose those of Protestant travellers, because of the spirit of the age: we are always ready to reject these days what we believe as originating from an overly religious source. Unfortunately I have not found anything satisfactory on the Holy Sepulchre in Pococke, Shaw, Maundrell, Hasselquist and others.

Quoting scholars and travellers who have written in Latin concerning the antiquities of Jerusalem, such as Adamannus, Bede, Brocard (Burchard of Mount Sion: Descriptio Terræ Sanctæ, 1284), Willibaldus (Saint Willibald, Bishop of Eichstatt), Breydenbach (Bernhard von Breydenbach: Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam, 1486), Sanut (Marinus Sanutus Torcellus: Liber Secretorum Fidelium Crucis super Terrae Sanctae), Ludolph (Ludolph of Saxony), Reland (His book, Palaestina ex monumentis veteribus illustrata, is a miracle of erudition), Andrichomius, Quaresmius, Baumgarten, Fureri (Christoph Furer von Haimendorff: Itinerarium), Bochart (Samuel Bochart), Arias Montanus (Benito Arias Montano), Reuwich (Erhard Reuwich), Hese (Johannes Witte de Hese: Itinerarius), or Cotovicus (Johann van Kootwyck: his description of the Holy Sepulchre gives almost all the hymns sung by the pilgrims at each station) would oblige me to translate passages, which, in the last result, would teach the reader nothing new (there is also a description of Jerusalem in Armenian, and one in Modern Greek: I have seen the latter. Ancient descriptions, like those of Sanutus, Ludolph, Brocard, Breydenbach, and Willibaldus; or those of Adamannus, or rather Arculf, and the Venerable Bede, are interesting, because in reading them one can judge of the alterations since made to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; but they would be useless as regards the building as I saw it). I am therefore obliged to French travellers (Juan Cerverio de Vera, in Spanish, is very concise, yet very clear; Giovanni Zuallardo, in his Il Devotissimo Viaggio di Gerusalemme, 1586, writing in Italian, is confused and vague; Pierre de La Vallée is charming, due to the unusual grace of his style, and his singular adventures, but is not authoritative) and, among these latter, I prefer the description of the Holy Sepulchre by Deshayes (Louis Deshayes, Baron de Courmenin), and this is why:

Belon (Pierre Belon du Mans: 1546-49), celebrated enough otherwise as a naturalist, says hardly a word concerning the Holy Sepulchre: his style also is extremely antiquated. Other writers, even older than he, or his contemporaries, such as Cachermois (Jean de Cachermois, 1490), Regnault (François Regnault, 1522), Salignac (Barthélemey de Salignac, 1522), Le Huen (Nicolas Le Huen, 1525), Gassot (Jacques Gassot,1536), Renaud (Antoine Renaud, 1548), Postel (Guillaume Postel, 1553), and Giraudet (Gabriel Giraudet, 1575), also use a language too remote from that which we now speak (some of these authors wrote in Latin, but there are old French versions of their works). Villamont (Henri de Villamont, 1588) drowns in detail, and has neither method nor judgement. Père Boucher (1610) is so exaggeratedly pious, it is impossible to cite him. Bénard (Nicolas Bénard, 1616) writes with wisdom enough, although he was only twenty years old at the time of his journey, but he is diffuse, flat and obscure. Père Pacifique (Père Pacifique de Provins, 1622) is vulgar, and his narrative is too concise. Monconys (Balthasar de Monconys, 1647) deals only with medical prescriptions. Doubdan (Jean Doubdan, 1651) is clear, knowledgeable, worthy of being consulted, but long, and prone to dwell on little things. Frère Roger (Eugène Roger, 1653), attached for five years to the service of the holy places, has knowledge, judgment, and a lively and animated style: his description of the Holy Sepulchre is too long, that is what led me to exclude him. Thévenot (Jean Thévenot, 1656), one of our best known travellers, has described the Church of Saint-Saveur to perfection, and I urge readers to consult his book (Voyage au Levant, XXXIX), but he is quite close to Deshayes: Père Nau, the Jesuit (1674), combines his knowledge of Eastern languages with the advantage of performing his journey to Jerusalem with the Marquis de Nointel (Charles-Marie-François Olier), our ambassador to Constantinople, the same to whom we owe the first drawings of Athens: it is a pity that the learned Jesuit is of an intolerable prolixity. The letter from Père Néret in the Lettres édifiantes, is excellent in many ways, but omits too much. I would say the same of Du Loiret de La Roque (Jean de la Roque). As for the modern travellers, Müller (Angelo Maria Müller: Reise nach Jerusalem, 1735), Venzow (Heinrich Venzow: Reise nach Jerusalem 1740), Korte (Jonas Korte, or Kortens: Travels, 1751), Bscheider (Fr. Gratus Bscheider: Das Heilige Land, 1792), Mariti (Giovanni Mariti: Travels, 1792), De Volney (Constantin François de Chassebœuf, Comte de Volney: Travels,1787), Niebuhr (Carsten Niebuhr: Travels, 1792), and Browne (William George Browne: Travels, 1799), are almost entirely silent on the holy places.

Deshayes (Baron Louis Deshayes de Courmenin: Voyage du Levant, 1621), sent by Louis XIII into Palestine, seems to me deserving of his narrative being adhered to:

1. Because the Turks were themselves eager to show the ambassador around Jerusalem, and he could have entered the mosque on the Temple mount if he had so wished;

2. Because his secretary’s slightly antiquated style is so clear and precise, which Paul Lucas (Voyage du Sieur Paul Lucas au Levant, 1704) has copied word for word, without risk of plagiarism, according to his usual practice;

3. Because D’Anville (and this is the most compelling reason), used Deshayes’ map as the subject of an essay that is perhaps our famous geographer’s masterpiece (such was the opinion of the learned Monsieur de Sainte-Croix, Guillaume, Baron de Sainte-Croix. D’Anville’s dissertation is entitled Dissertation sur l’étendue de l’ancienne Jérusalem). Deshayes will thus provide us with material regarding the Church of the Holy Sepulchre to which I will add my comments.

‘The Holy Sepulchre, with the majority of the holy places, are cared for by the Franciscan monks (Cordeliers), who are sent there for three year periods; and though all nations are represented among them, they nevertheless all pass for Frenchmen, or Venetians, and only survive because they are under the protection of our king. For nigh on sixty years they dwelt outside the city, on Mount Sion, at the very place where our Lord partook of the Last Supper with his apostles, but their church having been converted into a mosque, they have dwelt ever since within the city on Mount Gihon, the site of their monastery, known as Saint-Sauveur. That is where the Custodian lives, with the bulk of the order, providing monks to all the sites in the Holy Land as they are needed.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is not two hundred paces from the monastery. It includes the Holy Sepulchre, Mount Calvary, and several other holy places. It was Saint Helena who built a portion of it to cover the Holy Sepulchre; but the Christian princes who followed augmented it to include Mount Calvary which is only fifty paces from the Holy Sepulchre.

In ancient times, Mount Calvary was outside the city, as I have mentioned; it was the place of execution for condemned criminals; and in order that all the people might be present there was a large open space between the mountain and the city wall. The rest of the mountain was surrounded by gardens, of which one belonged to Joseph of Arimathea, a covert disciple of Jesus Christ, and in which he had made a tomb for him, in which was placed the body of Our Lord. It was not the custom among the Jews to bury a corpse as we Christians do. Each person, according to their means, carved, in some rock or other, a small room in which the body was placed, laid out on a platform of the same rock, and then they closed the cave, with a stone placed before the door, which was usually no more than four feet tall.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is of very irregular shape, dictated by the sites it was desired to enclose within it. The Church is roughly in the form of a cross, being one hundred and twenty paces long, not including the descent to the Chapel of the Discovery of the Holy Cross (Cave of the Cross), and seventy paces in width. There are three domes of which that which covers the Holy Sepulchre is the nave of the church. It is thirty feet in diameter, and is open at the top like the rotunda of Rome (the Pantheon). It is true that there is no vaulting; the dome is supported only by large rafters of cedar, which were brought from the Mountains of Lebanon. The church was once entered by any of three doors; but today there is only one, the keys of which the Turks guard jealously, lest the pilgrims enter without paying the nine zecchinos, or thirty-six livres, entrance fee which is owed, I mean those who come from Christendom, since Christian subjects of the Grand Seigneur pay less than half that amount. The door is always closed, and has only a small window divided by an iron bar, through which those outside supply food to those inside, who are of eight different nations.

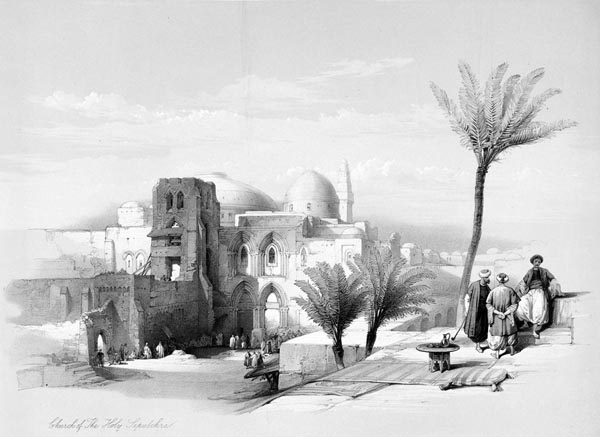

‘Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Exterior View’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

The first nation is that of the Romans or Latins, the Cordeliers of the Franciscan Order. They maintain the Holy Sepulchre, the site of Calvary where our Lord was nailed to the cross, the cave where the Holy Cross was found, the Stone of Anointing (Stone of Unction), and the chapel where Our Lord appeared to the Virgin after his resurrection (Chapel of Mary Magdalene).

The second nation is that of the Greeks, who maintain the choir of the church, where they officiate, in the middle of which is a small circle of marble (the compas), which they believe marks the centre of the earth.

The third nation is that of the Abyssinians; they maintain the chapel (of the Blessed Sacrament) which contains the Impropere pillar (the Pillar of the Flagellation).

The fourth nation is that of the Copts, who are the Egyptian Christians, they have a small chapel (the Coptic Chapel) near the Holy Sepulchre.

The fifth is that of the Armenians, they maintain the Chapel of Saint Helena, and one where the clothes of our Lord were shared out, and they cast lots for them.

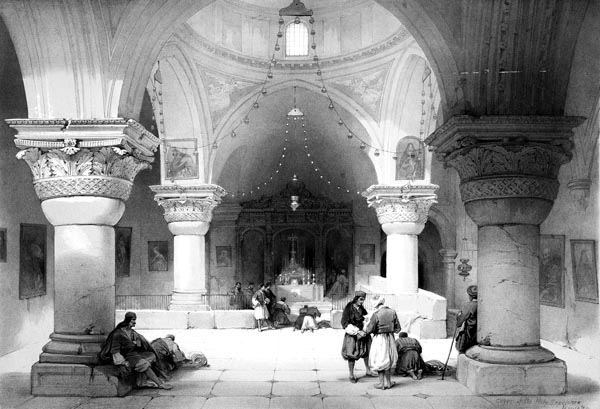

‘Chapel of St. Helena - Crypt of the Holy Sepulchre’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

The sixth nation is that of the Nestorians or Jacobites, who come from Chaldea and Syria; they have a small chapel near the place where Our Lord appeared to the Magdalene, whom she took for a gardener, and it is therefore called the Chapel of the Magdalene.

The seventh nation is that the Georgians who live between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea; they maintain the site of Calvary, where the cross was erected, and the prison where Our Lord remained, while the hole was dug in which to set it.

The eighth nation is that of the Maronites, who live in the Mountains of Lebanon; they recognize the Pope as we do.

Each nation, in addition to those places that all within can visit, has another special place in the vaults, and corners of the church to serve them as a retreat, and where they perform their offices according to their custom: for the priests and monks who visit usually remain for two months or so, without leaving the building, until the monastery in the city sends others to serve in their place. It would be impossible to remain there long without becoming ill, because there is very little fresh air, and because the arches and walls produce a quite unhealthy coolness, however we found a good hermit there, who had taken the habit of Saint Francis, and lived twenty years in the place without leaving, though he had so much work to do maintaining the two hundred lamps, and cleaning and adorning all the holy places, he was unable to rest for more than four hours per day.

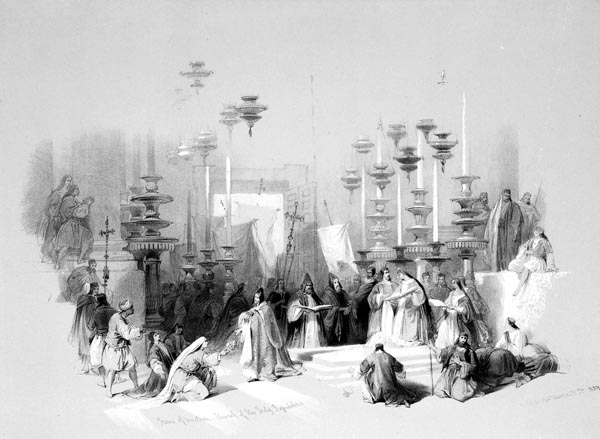

On entering the church, we see the Stone of Unction, on which the body of Our Lord was anointed with myrrh and aloes, before being placed in the tomb. Some say it is of the very rock of Mount Calvary, while others hold that it was brought to that place by Joseph and Nicodemus, secret disciples of Jesus Christ, who rendered him that pious office, and that it is of a green hue. Be that as it may, because of the indiscretion of some pilgrims who damaged it, they were forced to cover it with white marble, and surround it with a small iron rail, to prevent anyone walking on it. It is seven feet nine inches long, and one foot eleven inches wide, and above it are eight lamps which burn continuously.

‘Stone of the Unction - Church of the Holy Sepulchre’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

The Holy Sepulchre is thirty feet from the stone, exactly beneath the middle of the great dome of which I have spoken: it is like a small cave that has been excavated and shaped in solid rock with a chisel. The door facing east is only four feet high and two and a quarter wide, so that one must bow very low to gain entry. The interior of the sepulchre is almost square. It is six feet one inch long, five feet ten inches wide, and from floor to roof, is eight feet one inch high. There is a solid platform of the same stone, which remained after excavating the rest. It is two feet four and a half inches high, and occupies half the tomb, being five feet eleven inches long, and two feet eight and a half inches wide. It was on this table that the body of Our Lord was laid, with the head towards the west and the feet towards the east, but because of the superstitious devotion of the Orientals, who believe that having laid His head on the stone, God would never abandon them, and also because the pilgrims broke off pieces of it, it became necessary to cover it with the white marble on which the Mass is now celebrated. Forty-four lamps continually burn in this holy place, and to allow egress to the smoke, three holes have been made in the ceiling. The outside of the sepulchre is covered with marble tablets, and several columns, with a dome above.

‘The Shrine of the Holy Sepulchre’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

At the entrance door of the tomb, there is a stone which is a foot and a half square, and is raised a foot, which is of the same rock, and which served to support the large stone that closed off the entrance; it was from this rock that the angel spoke to the two Marys (Matthew:28); and on account of this mystery, and lest one entered prematurely into the Holy Sepulchre, the early Christians created a small chapel in front, which is called the Chapel of the Angel.

Twelve paces from the Holy Sepulchre, in turning towards the north, one encounters a large stone of grey marble, which is about four feet in diameter, set there to mark the place where Our Lord appeared to the Magdalene, she supposing him to be the gardener (John:20:15).

Further on is the Chapel of the Apparition (the Franciscan Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament), where tradition holds that Our Lord first appeared to Mary after his resurrection. This is the place where the Franciscan monks perform their offices and to which they repair: since from there they enter rooms that have no other access except by way of the chapel.

Continuing our tour of the church, one encounters a small vaulted chapel, which is seven feet long and six feet wide, otherwise known as the Prison of Our Lord, because he was confined in this place until they had dug the hole in which to set up the cross. This chapel is opposite Calvary, so that the two locations are aligned to the crucifix-form of the church, since Calvary is to the south and the chapel to the north.

Quite close to this is another chapel, five paces long and three wide, which is the very place where Our Lord was stripped of his clothes by the soldiers before being nailed to the cross, and where his clothes were shared out and they cast lots for them (John:19:24).

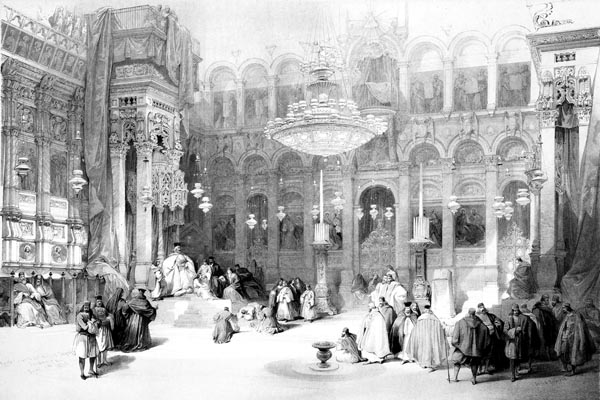

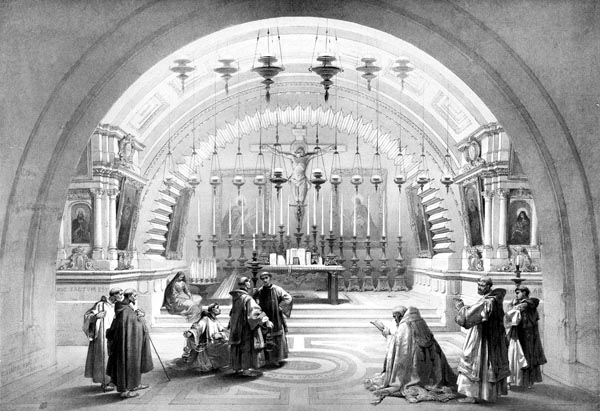

‘Interior of the Greek Church of the Holy Sepulchre’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

Leaving the chapel, we find a grand staircase to our left, which pierces the wall of the church and goes down to a kind of cave carved in the rock. After descending thirty steps, there is a chapel on the left which is commonly called the Chapel of Saint Helena, because she prayed there while seeking the Holy Cross. We descend a further eleven steps to the place where it was found along with the nails, the crown of thorns and the blade of the spear, which had been hidden in this place more than three hundred years.

Near the top of this level, turning towards Calvary, is a chapel four paces long and two and a half wide, under the altar of which is visible a column of grey marble, inlaid with black markings, which is two feet high and one foot in diameter. It is called the Pillar of the Impropere (the Pillar of the Flagellation), because there Our Lord was made to sit to be crowned with thorns.

At ten paces from the chapel, we encounter a little narrow stair, the steps of which are of wood at the beginning and stone at the end. There are twenty in all, by which one mounts to Calvary. That place, once so heinous, being sanctified by the blood of Our Lord, was given great attention by the early Christians; and, after removing all the dirt and earth covering it, they enclosed it with walls; so that it is now like a tall chapel, enclosed within the greater church. It is clad in marble inside, and split in two by an archway. To the north is the place where our Lord was nailed to the cross. There are always thirty-two lamps burning there, maintained by the Franciscans, who also celebrate Mass daily in this sacred place.

‘Calvary - Holy Sepulchre’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

In another part, to the south, the Holy Cross was erected. One can still see the hole which was dug about a foot and a half into the rock, beneath the earth that covered it. The place where the thieves’ crosses stood are close by. That of the good thief was to the north, and the other to the south, so that the former was on the right hand of Our Lord, who had his face turned to the west, and his back to Jerusalem, on the east. Fifty lamps burn continually to honour this sacred place.

Below the chapel are the tombs of Godfrey of Bouillon and his brother Baldwin I, where these inscriptions may be read:

HIC JACET INCLYTUS DUX GODEFRIDUS DE

BULION, QUI TOTAM TERRAM ISTAM AC-

QUISIVIT CULTUI CHRISTIANO, CUJUS ANIMA

REGNET CUM CHRISTO, AMEN.

BALDUINUS REX, JUDAS ALTER MACHABAEUS,

SPES PATRIAE, VIGOR ECCLESIAE, VIRTUS UTRIUSQUE,

QUEM FORMIDABANT, CUI DONA TRIBUTA FEREBANT

CEDAR ET AEGYPTUS, DAN AC HOMICIDA DAMASCUS,

PROH DOLOR! IN MODICO CLAUDITUR HOC TUMULO.

Here lies the famous Duke Godfrey

Of Bouillon, who won all this land

For the Christian faith, may his soul

Reign with Christ, Amen.

King Baldwin, a second Judas Maccabeus,

The hope of his country, the strength of the Church, the pride of both,

Feared by all, to whom gifts were brought

By the tribes of Kedar and Egypt, Dan and man-slaying Damascus,

Is enclosed, alas, in this narrow tomb!

(Besides these tombs are four others half-destroyed. On one of these tombs can be read, though with much difficulty, an epitaph reported by Cotovicus.)

Calvary is the last station of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; for twenty paces from it we again find the Stone of Unction, at the entrance to the church.’

Deshayes having thus described the holy stations of so much of the site in order, it only remains for me to reveal those places to the reader in their entirety.

We see, firstly, that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is composed of three churches: that of the Holy Sepulchre, that of Calvary, and that of the Discovery of the Holy Cross.

Properly speaking, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is built in the valley of Mount Calvary, and on the terrain where we know that Jesus Christ was buried. The Church forms a cross: the chapel of the Holy Sepulchre itself is in fact the great nave of the building: it is circular like the Pantheon in Rome; and is lighted only by the dome, beneath which is found the Holy Sepulchre. Sixteen marble columns adorn the perimeter of the rotunda; they support, on seventeen arches, an upper gallery, also composed of sixteen columns and seventeen arches, smaller than the former columns and arches that bear them. Niches, corresponding to the arches, rise above the frieze of the upper gallery, and the dome rises from the circle of niches. These were once decorated with mosaics depicting the twelve apostles, Saint Helena, the Emperor Constantine and three other unidentified portraits.

The choir of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (the Choir of the Crusaders) is to the east of the nave of the tomb: it is double, as in other ancient basilicas, that is to say, there is first an area with stalls for the priests then a secluded sanctuary, raised above the former by two steps. Around this double sanctuary, run the twin wings of the choir, and in these wings are placed the chapels described by Deshayes.

From the right wing, behind the choir, two staircases also run, one to the Chapel of Calvary, the other to the Chapel of the Discovery of the Holy Cross: the first ascends to the summit of Calvary, the second descends beneath Calvary itself; indeed, the cross was erected on the summit of Golgotha, and found beneath that mount. Thus, to summarize, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is built at the foot of Calvary: it touches that summit on its eastern side, beneath which, and above which, two other churches were built, which are attached by walls and vaulted staircases to the main building.

The architecture of the church is obviously of the age of Constantine; the Corinthian order prevails everywhere. The pillars are heavy or slender, their diameter almost always being out of proportion to their height. Various linked columns which support the frieze to the choir, however, are of a fine style. The church is tall and expansive, its cornices strike the eye with sufficient grandeur; but in the past sixty years they have lowered the arch separating the chancel from the nave, the horizontal line is broken, and one can no longer enjoy a view of the whole vault.

The Church has no porch; it is entered by two side doors; and there is never more than one of them open. Thus, the building appears to have no external decoration. It is also masked by the huts, and the Greek monastery, attached to the walls.

The small marble monument that covers the Holy Sepulchre takes the form of a catafalque, decorated with connected semi-gothic arches on the blank sides of this catafalque; it rises elegantly below the dome which illuminates it: but is spoilt by a bulky chapel that the Armenians were granted permission to build at one of its extremities. The interior of the catafalque reveals a plain tomb of white marble, attached on one side to the wall of the building, and serves as an altar for the Catholic faith: it is the Tomb of Jesus Christ.

The origins of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre are of some antiquity. The author of the Epitome of the holy wars (Epitome Bellorum Sacrorum) claims that, forty-six years after the destruction of Jerusalem by Vespasian and Titus, the Christians obtained permission from Hadrian to build or rebuild a temple over the tomb of their God, and to enclose in the new city other places revered by Christians. He adds that the temple was enlarged, and repaired, by Helena, mother of Constantine. Quaresmius contests this account, ‘because’, he says, ‘until the reign of Constantine the faithful were denied permission to erect such temples.’ This scholar of religion forgets that before Diocletian’s persecution, the Christians owned to many churches, and celebrated their mysteries publicly. Lactantius and Eusebius attest to the wealth and happiness of believers at that time.

Among other trustworthy authors, Sozomen, in the second book of his History (Historia Ecclesiastica), Saint Jerome in his Epistles to Paulinus and Rufinus; Severus (Sulpicius Severus: Chronica) in Book II, Nicephorus (Nicephorus of Constantinople: Historia Ecclesiastica) in Book XVIII, and Eusebius in his Life of Constantine; tell us that the pagans surrounded the holy places with a wall; that they erected a statue of Jupiter over the tomb of Jesus Christ, and another statue of Venus on Calvary; and that they dedicated a grove to Adonis over the birthplace of the Saviour. These testimonies also demonstrate the antiquity of the true faith in Jerusalem by the very profanation of previously sacred places, and show that Christians had sanctuaries in those same places.

Regardless of that, the foundation of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre dates back to at least the reign of Constantine; we still have a letter from that emperor, commanding Saint Macarius, Bishop of Jerusalem (312-335AD), to erect a church on the site where the great mystery of the salvation was accomplished. Eusebius preserved this letter. The Bishop of Caesarea then describes the new church, the dedication of which lasted eight days. If Eusebius’s narrative needs to be supported by the testimonies of others, we possess those of Cyril, Bishop of Jerusalem (c350AD: Catecheses: 1,10,13), Theodoret (of Cyrus), and even the Itinéraire de Bordeaux à Jérusalem, of 333: ibidem, jussu Constantini imperatoris, basilica facta est mirae pulchritudinis: in that very place, by order of the Emperor Constantine, a basilica was built of wondrous beauty.

That church was destroyed (614AD) by Chosroes II, King of Persia, nearly three centuries after it was built by Constantine. The Emperor Heraclius restored the true cross (629AD), and Modestus, Bishop of Jerusalem, rebuilt the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Not long afterwards, the Caliph Omar took Jerusalem (c638AD), but left the Christians free to exercise Christian worship. In 1009, the Caliph Hequem or Hakem (Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah), who ruled Egypt, brought desolation on the tomb of Jesus Christ. Some say the mother of this prince, who was a Christian, had the walls of the ruined church rebuilt; others, that the son (Ali az-Zahir) of this Caliph of Egypt, at the solicitation of the Emperor Argyros (Romanos III Argyros), allowed the faithful to enclose the holy places in a new building. But since, in the reign of Hakem, the Christians of Jerusalem were neither rich enough nor skilful enough to erect the building that now covers Calvary (it is said that Mary, wife of Hakem, and mother of the new Caliph, built it anew, and she was assisted in this pious enterprise by Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos); and since, despite a very dubious passage in William of Tyre’s Historia, there is no indication that the Crusaders built a church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, it is likely that the church founded by Constantine has always existed much as it is, at least as regards the walls of the building. Inspection of the architecture alone of this edifice would suffice to demonstrate the truth of what I say.

The Crusaders having captured Jerusalem, on the 15th of July 1099, snatched the Tomb of Jesus Christ from the hands of the infidels. For eighty-eight years it remained under the control of the successors of Godfrey of Bouillon. When Jerusalem fell once more under the Muslim yoke, the Syrians ransomed the Church of the Holy Sepulchre for gold, and the monks came, to defend with their prayers the sites entrusted in vain to the weapons of kings: it is thus, that despite a thousand vicissitudes, the faith of the early Christians preserved to us a temple that it was given to our century to see destroyed.

The first travellers were extremely fortunate; they were not obliged to enter into all these details: firstly, because they found in their readers a religion that never disputes the truth; and secondly, because all were convinced that the only way to see a country as it truly exists is to view it with all its customs and memories. It is, indeed, with the Bible and the Gospel in our hands that we must travel to the Holy Land. If one wishes to bring to it a spirit of contention and argument, it is not worth the trouble of making the long journey to Judea. What would we say of a man who, in travelling through Greece and Italy, spent his time merely contradicting Homer and Virgil? Yet that is how we travel nowadays: the real result of our own self-esteem, which encourages us to appear clever by expressing our disdain.

Christian readers may well be wondering what feelings I experienced on entering this redoubtable place; I can not really say. So much presented itself simultaneously to my mind that I failed to hold on to any specific thought. I remained for about half an hour on my knees in the little chamber of the Holy Sepulchre, my gaze fixed on the stone, unable to look elsewhere. One of the two monks who was guiding me, remained prostrate beside me, his forehead against the marble; the other, Gospel in hand, read to me, by lamplight, the passages relating to the holy tomb. Between each verse he recited a prayer: Domine Jesu Christe, qui in hora diei vespertina de cruce depositus, in brachiis dulcissimae Matris tuae reclinatus fuisti, horaque ultima in hoc sanctissimo monumento corpus tuum exanime contulisti, etc: O Lord Jesus Christ, who in the evening hour of the day, brought down from the cross, lay in the arms of your most sweet Mother, and whose lifeless body at the last hour was bestowed in this sacred place, etc. All I can state, is that in sight of that victorious tomb I felt only my own feebleness; and when my guide exclaimed with Saint Paul: Ubi est, Moria, victoria tua? Ubi est, Moria, stimulus tuus? Death, where is thy victory? Death where is thy sting? (Vulgate: 1 Corinthians 15:55), I listened as if Death might respond that he had been conquered, and was enchained in that monument.

We walked round the stations as far as the summit of Calvary. Where might one find anything as moving in all antiquity, anything as wonderful as the last scenes of the Gospel? Here are not the bizarre adventures of some deity alien to mankind: here is a story filled with pathos, a story that not only causes one to shed tears at its beauty, but of which the consequences, applied to the universe, have changed the face of the earth. I had just visited the monuments of Greece, and was still filled with their greatness; but they were far from inspiring in me what I felt at the sight of the holy places!

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, composed of several churches, built on uneven ground, lit by a multitude of lamps, is singularly mysterious; darkness reigns there favourable to piety and soulful meditation. Christian priests of various sects live in different parts of the building. From the heights of the arches, where they nestle like doves to the depths of the chapels and underground vaults, the emit their chants at all hours of day and night; the organ-music of the Latin priest, the cymbals of the Abyssinian, the voice of the Greek, the prayer of the Armenian solitary, the plaint-like chant of the Coptic monk, strike alternately or simultaneously on your ear; you do not know from whence these sounds arise; you breathe the smell of incense without seeing the hand that ignites it: you only see the pontiff passing by, vanishing behind the pillars, losing himself amongst the shadows of the temple; the pontiff, who will celebrate the most redoubtable mysteries in the very places where they were enacted.

I could not leave those sacred precincts without pausing at the monuments to Godfrey and Baldwin: they face the door of the church and are attached to the wall of the choir. I saluted the ashes of those royal knights, who deserve to rest near to the great sepulchre they had delivered. Those ashes are French, the only ones buried in the shadow of the tomb of Jesus Christ. What a badge of honour for my homeland!

I returned to the monastery at eleven o’clock, and went out again at noon, to follow the Via Dolorosa: so the route is called that the Saviour of the World traversed from the house of Pilate to Calvary.

Pilate’s house (the governor of Jerusalem once lived in this house, but now only his horses lodge among the remains) is a ruin from which one can see the vast foundations of Solomon’s temple, and the mosque built on those foundations.

Jesus Christ having been scourged, crowned with thorns, and clothed in a purple tunic, was presented to the Jews by Pilate: Ecce Homo: Behold the Man’ (Vulgate: John: 19:5) cried the judge, and we may still see the window from which he uttered those memorable words.

According to the Latin tradition in Jerusalem, the crown of Jesus Christ was made from the thorny shrub lycium spinosum. But Hasselquist, knowledgeable botanist that he is, believes that the nabka of the Arabs was employed for this purpose. The reason he gives is worth mentioning:

‘There is every indication,’ the author says ‘that nabka (Paliurus spina-christi) provided the crown placed on the head of Our Lord: it is common in the East. One could not choose a plant more suited to this purpose, because it is armed with prickles; its branches are flexible and pliant, and its leaf is dark green, like ivy. Perhaps the enemies of Jesus Christ chose it, to add insult to his injuries, a plant similar to that used to crown emperors and military generals.’

Another tradition, found in Jerusalem, preserves the sentence pronounced by Pilate on the Saviour of the world:

‘Jesum Nazarenum, subversorem gentis, contemptorem Caesaris, et falsum Messiam, ut majorum suae gentis testimonio probatum est, ducite ad communis supplicii locum, et eum in ludibriis regiae majestatis, in medio duorum latronum, cruci affigite. I, lictor, expedi cruces: conduct to the common place of execution, Jesus of Nazareth, seducer of the people, scorner of Caesar, and, according to the testimony of the elders of his people, false Messiah; crucify him between two thieves, with the derisive title of King. Go, lictor, prepare the crosses.’

A hundred and twenty paces from the Ecce Homo, I was shown the ruins, on the left, of an old church dedicated to Our Lady of Sorrows. It was in this place that Mary, driven away at first by the guards, met her son burdened by the cross. This fact is not reported in the Gospels, but is generally believed on the authority of Saint Boniface and Saint Anselm. Saint Boniface says that the Virgin fell like one half-dead, and could not utter a single word: Nec verbum dicere potuit. Saint Anselm assures us that Christ greeted her with these words: Salve, Mater! As we find Mary at the foot of the cross (John:19:25) this account by the Fathers is more than probable, faith is not contrary to these traditions: they show how the marvellous story of the Passion was etched in the memory of mankind. Eighteen centuries rolling by, persecutions without end, revolutions eternal, ruins ever falling, could not efface or hide the traces of a mother come to mourn her son.

Fifty paces farther we came to the place where Simon of Cyrene helped Jesus carry the cross.

‘And as they led him away, they laid hold upon one Simon, a Cyrenian, coming out of the country, and on him they laid the cross, that he might bear it after Jesus.’ (Luke:23:26)

Here the path, which was heading east-west reached a bend and turned north, and I saw, on the right hand, the place where Lazarus the beggar lay, and opposite, on the other side of the street, the house of the rich sinner.

‘There was a certain rich man, which was clothed in purple and fine linen, and fared sumptuously every day:

And there was a certain beggar named Lazarus, which was laid at his gate, full of sores,

And desiring to be fed with the crumbs which fell from the rich man's table: moreover the dogs came and licked his sores.

And it came to pass, that the beggar died, and was carried by the angels into Abraham's bosom: the rich man also died, and was buried;

And in hell he lift up his eyes, being in torments, and seeth Abraham afar off, and Lazarus in his bosom.’ (Luke 16:19-23)

Saint Chrysostom, Saint Ambrose and Saint Cyril believed that the story of Lazarus and the rich sinner was not simply a parable, but a true and established fact. The Jews themselves have preserved the name of the rich sinner, whom they call Nabal (see 1 Samuel:25).

After passing the rich sinner’s house, one turns right, and takes a westerly direction. At the entrance to the street that ascends towards Calvary, Christ met the holy women, weeping.

‘And there followed him a great company of people, and of women, which also bewailed and lamented him.

But Jesus turning unto them said, Daughters of Jerusalem, weep not for me, but weep for yourselves, and for your children.’ (Luke:23:27-28)

A hundred and ten paces from there is the site of the house of Veronica, and the place where that pious woman wiped the face of the Saviour. The woman’s original name was Berenice; it was subsequently changed to Vera-Icon, a true image, by the transposition of two letters; moreover, the transmutation of B to V is quite common in ancient languages.

After a further hundred paces one reaches the Judicial Gate: this was the gate through which criminals emerged who were executed on Golgotha. Golgotha, now contained within the new city, was outside the walls of ancient Jerusalem.

From the Judicial Gate to the summit of Calvary one takes about two hundred paces: there the Via Dolorosa ends, being about a mile in length. We have seen that Calvary is now included within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. If those who read the Passion in the Gospel are struck with holy sadness and profound admiration, imagine what it is like to recall those scenes, at the foot of Mount Sion itself, in sight of the Temple, and the very walls of Jerusalem!

After the description of the Via Dolorosa and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, I will say only a few words regarding the other places of worship found within the precincts of the city. I will simply name them in the order that I visited them during my stay in Jerusalem.

1. The house of Annas the High Priest, near to the Gate of David (Jaffa Gate), at the foot of Mount Sion, inside the city wall: the Armenians maintain the church built on the ruins of this house;

2. The site of the Saviour’s appearance to Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Mary Salome (Mark:16:1), between the castle and the gate of Mount Sion;

3. The house of Simon the Pharisee (Luke:7:36); the Magdalene there confessed her sins; it is a church, wholly in ruins, on the east of the city;

4. The monastery of Saint Anne, mother of the Blessed Virgin; and the Grotto of the Immaculate Conception, beneath the monastery church; the monastery has been converted into a mosque; but you can enter by paying a few coins (medins). Under the Christian kings, it was inhabited by nuns. It is not far from the house of Simon.

5. The Prison of St. Peter, near the Calvary; it consists of old walls, where they show iron clamps;

6. The house of Zebedee, not far from the Prison of Saint Peter, is a large church that belongs to the Greek Patriarch;

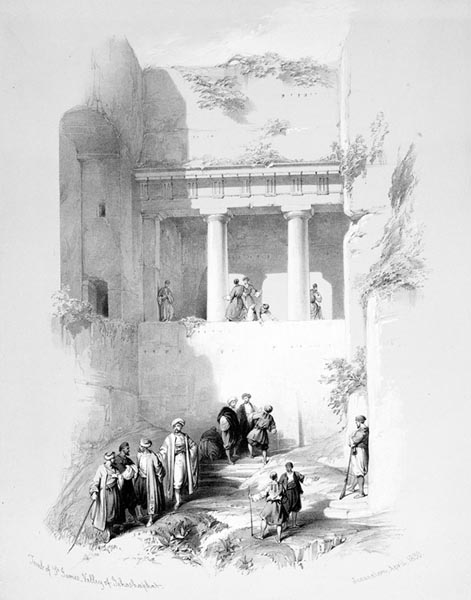

7. The house of Mary, mother of John Mark, where Saint Peter stayed when he had been delivered by the angel (Acts:12:12), is a church maintained by the Syrians;

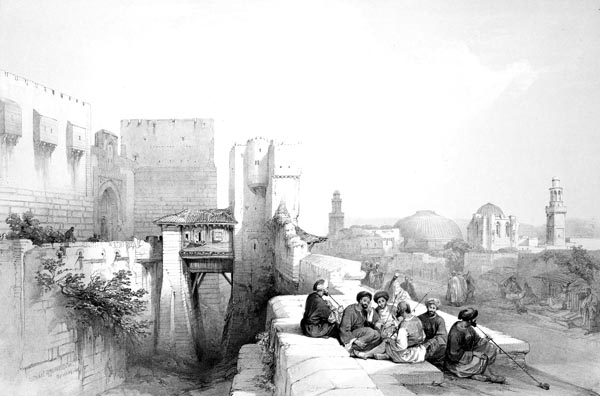

‘Jerusalem - the Church of the Purification’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

8. The site of the martyrdom of Saint James the Greater (Acts:12:1-2). It is the Armenian monastery; the church within is very rich and elegant. I will speak of the Armenian Patriarch a little later.

Readers now have a complete picture of the Christian monuments of Jerusalem before their eyes. We will now visit the exterior of the holy city.

I had taken two hours to traverse the Via Dolorosa on foot. I took care each day to revisit this sacred path, and the church of Calvary, so that no essential detail might escape my memory. It was two o’clock then, on the 7th of October, when I finished my first review of the holy places. I next mounted my horse, and was accompanied by Ali-Aga, Michel the dragoman, and my servants. We left via the Jaffa Gate to make a complete circuit of Jerusalem. We bristled with weapons, were dressed in the French manner, and were very determined not to suffer any insult. One can see how much times have changed, thanks to the renown of our victories, since Deshayes, Louis XIII’s ambassador, had the greatest difficulty in obtaining permission to enter Jerusalem armed with his sword.

We turned left on leaving the city gate; we rode south, and passed the pool of Beersheba, a wide deep ditch, but devoid of water; then we climbed the mount of Sion, part of which lies outside Jerusalem.

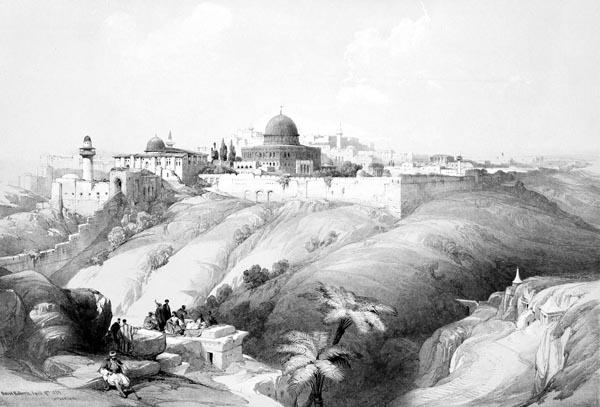

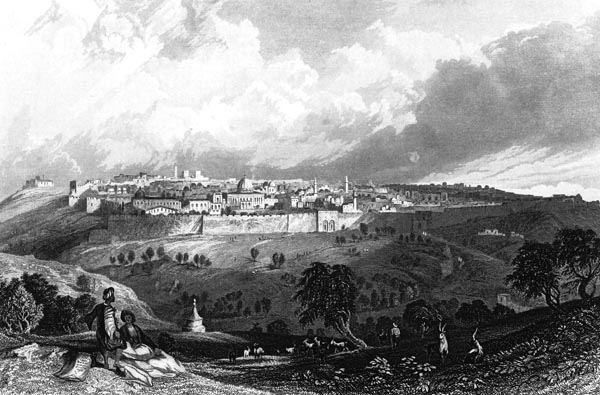

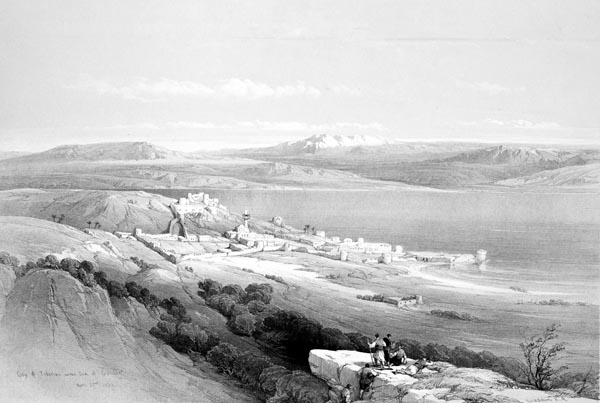

‘Jerusalem from the South’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

I assume that the name Sion awakens profound memories in the minds of my readers; and that they are curious to know about this mount so mysterious in Scripture, so celebrated in the songs of Solomon, this object of the prophets’ blessings and tears, and whose misfortunes Racine has lamented (see Racine’s Esther: Act I Scene I).

It is a hill of a yellowish barren aspect, opening out in a crescent-shape towards Jerusalem, about the height of Montmartre, but more rounded at the top. The sacred summit is marked by three monuments or rather by three ruins: the house of Caiaphas; the Holy Cenacle (the site of the Last Supper); and the tomb or palace of David. From the heights of the mountain you can see the Valley of Ben Hinnom (Gehenna) to the south; beyond that valley is the Field of Blood (Akeldama), bought by Judas for thirty pieces of silver, the Mount of Evil Council, the tombs of the judges and all the desert towards Hebron and Bethlehem. To the north, the walls of Jerusalem, which stretch towards the summit of Sion, prevent you from seeing the city; the latter slopes down to the valley of Jehoshaphat.

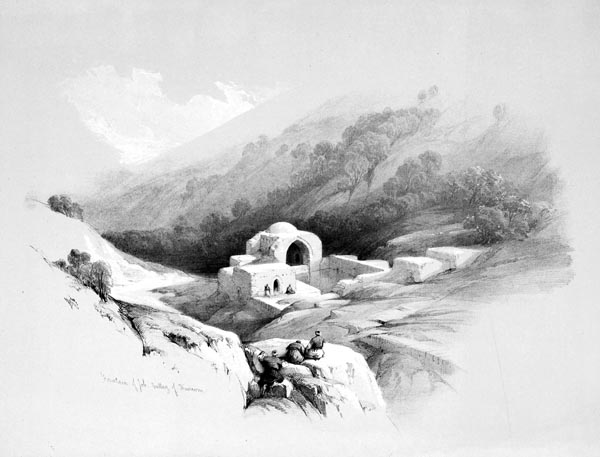

‘Fountain of Job - Valley of Hinnom’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

Caiaphas’s house is now a church maintained by the Armenians; the tomb of David is a little vaulted room where there are three tombs of blackened stone; the site of the Holy Cenacle is now occupied by a mosque and a Turkish hospital, which were formerly a church and monastery occupied by the Fathers of the Holy Land. This latter shrine is equally famous in both the Old and New Testament: David built his palace and his tomb there, and there he watched over the ark of the covenant for three months (2 Samuel:6;11), Jesus Christ partook of the last Passover, and instituted the sacrament there of the Eucharist; he appeared to his disciples there on the day of resurrection; there too the Holy Spirit descended upon the apostles. The Holy Cenacle became the first Christian church that the world had ever seen; there Saint James the Lesser was consecrated as the first bishop of Jerusalem, and Saint Peter held the first council of the Church there; finally it was from there that the apostles were ordered, poor and naked as they were, to mount the thrones of the earth, and: Docete omnes gentes: teach all the nations (Vulgate: Matthew:28:19)!

The historian Josephus has left us a magnificent account of the palace and tomb of David (Jospehus: Antiquities:VII). Benjamin of Tudela (Itinerary:Jerusalem) tells a curious tale regarding the discovery of the tomb.

Descending the mountain of Sion, on the east, one reaches, in the valley, the fountain and pool of Siloam, where Jesus Christ healed the blind man (John:9:1-7). The spring emerges from a rock, it goes softly, cum silentio, according to the testimony of Isaiah (Isaiah:8:6), which contradicts a passage of Saint Jerome (Commentary on Isaiah:III.VIII:119); it has a kind of ebb and flow, sometimes pouring forth its waters like the fountain of Vaucluse, sometimes retaining them so that they barely flow. The Levites sprinkled the water of Siloam on the altar at the Feast of the Tabernacles, singing: Haurietis aquas in gaudio de fontibus Salvatoris: with joy shall ye draw water out of the wells of Salvation (Vulgate: Isaiah:12:3). Milton cites that stream, at the beginning of his poem, instead of the Castalian Fount:

‘Upper fountain of Siloam - Valley of Jehoshaphat’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

‘………………......Or if Sion Hill

Delight thee more, and Siloa’s Brook that flow'd

Fast by the Oracle of God, etc.

Delille (Jacques Delille: Paradise Lost, 1805 translation) has rendered these fine verses marvellously well.

Some say this fountain emerged suddenly from the earth to quench Isaiah’s thirst when the prophet was sawn in half with a wooden saw by order of Manasseh (Talmud: Mishnah: Yevamot, fol. 49,2); others claim they saw it appear in Hezekiah’s reign, from which we have the wonderful song recorded in Isaiah (Isaiah:38:9, and see Jean-Baptiste Rousseau’s: Ode tirée du Cantique d’Ézéchias, whose first two lines Chateaubriand now quotes).

J'ai vu mes tristes journées

Décliner vers leur penchant;

According to Josephus, this miraculous spring flowed for the army of Titus, and refused its waters to the guilty Jews (Josephus: Jewish Wars: IX:4). The pool, or rather the twin pools of the same name, is quite near the source. They serve now as before for washing clothes, and we saw women there who shouted abuse at us as they fled. The water of the fountain is quite salty and unpalatable to the taste; people bathe their eyes there in memory of the healing of the blind man.

‘Lower Pool of Siloam - Valley of Jehoshaphat’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

Nearby is shown the place where the prophet Isaiah suffered the punishment of which I spoke. There is also a village there called Siloan; at the foot of this village is another fountain, that the Scriptures call Rogel (En-Rogel: the Fountain of the Fuller): facing this fountain, at the foot of Mount Sion, is a third fountain, which bears the name of Mary. It is believed that the Virgin came to fetch water, as the daughters of Laban came to the well from which Jacob rolled the stone: Ecce Rachel veniebat ovibus patris sui cum: Rachel came with her father’s sheep, etc. (Genesis 29:9). The Fountain of the Virgin mingles its waters with those of the pool of Siloam.

Here, as noted by Saint Jerome, we are at the base of Mount Moriah beneath the walls of the Temple, almost opposite the Gate of Sterquilinus (god of fertilisation, hence manure: this is the Dung Gate, Bab al-Maghariba). We proceeded towards the eastern corner of the city wall, and entered the valley of Jehoshaphat. It runs from north to south between the Mount of Olives and Mount Moriah. The Kidron River runs through it; the river is dry for part of the year; in storms, or during the spring rains, it yields a reddish coloured water.

The Valley of Jehoshaphat is also called in Scripture the Valley of Shaveh, the Valley of the King, the Valley of Melchizedek (regarding all this there are different opinions. The Valley of the King may well have been nearer the mountains of Jordan, and that location is more appropriate to the story of Abraham). It was in the Valley of Melchizedek that the king of Sodom sought Abraham to congratulate him on his victory over the five kings (Genesis:14:17). Moloch and Belphegor (Baal-Peor) were worshipped in that same valley. It later took the name Jehoshaphat, because the king of that name erected his tomb there. The Valley of Jehoshaphat seems always to have served as a cemetery for Jerusalem; one meets there with monuments of the remotest ages, and of recent times: Jews come there to die from the four corners of the world; a stranger sells them, for their weight in gold, a little ground in which their corpse is to be buried, in the fields of their ancestors. The cedars which Solomon planted in this valley (Josephus relates that Solomon clothed the plains of Judea with cedars: Josephus: Antiquities: VIII.7.4), the shadow of the temple with which it was covered, the river that flowed through it (Kedron is a Hebrew word which signifies darkness and sadness; one notes that there is an error in the Greek text, and hence in the Vulgate, of verse XVIII:1 of the Gospel of Saint John, which calls it the river of cedars; the error derives from an incorrect letter, omega for omicron, χεδρων instead of χεδρον), the songs of mourning that David wrote there, the lamentations that Jeremiah gave tongue to there, rendered it fitting for sadness, and the peace of the tomb. In commencing his passion in that solitary place, Jesus Christ consecrated it again to sorrow: the innocent David there poured out, to wash away our sins, the tears that a guilty David shed to atone for his own errors. There are few names that rouse the imagination to thoughts at once more moving and more formidable than that of the valley of Jehoshaphat, a valley so full of mysteries that, according to the prophet Joel, all men will one day have to appear there before the redoubtable judge: Congregabo omnes gentes, et deducam eas in vallem Jehoshaphat, et disceptabo cum eis ibi: I will also gather all nations, and will bring them down into the valley of Jehoshaphat, and will plead with them there (Joel: 3:2). ‘It is reasonable,’ says Père Nau, ‘that the honour of Jesus Christ should be publicly restored in the place where He was robbed of it with such insults and indignities, and that He shall judge men justly in the place where they so unjustly judged Him.’

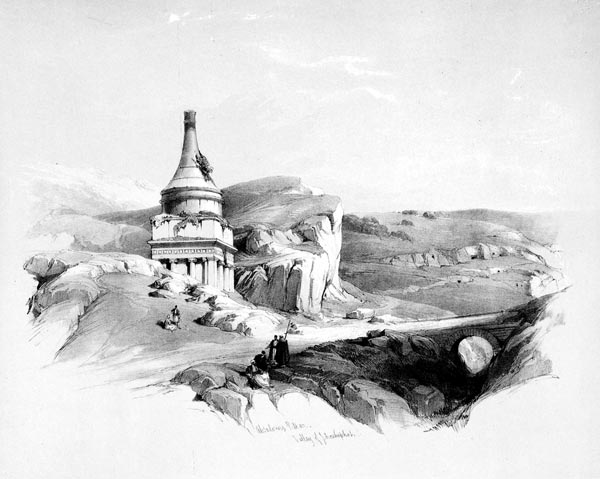

The Valley of Jehoshaphat has a desolate aspect: the western side is a high chalk cliff that supports the gothic walls of the city, above which one can see Jerusalem; the eastern side is formed by the Mount of Olives and the Mountain of Offence, Mons Offensionis, so named from Solomon’s idolatry (Vulgate:2 Kings: 23:13). These two mountains, which are connected, are almost bare, and of a red and sombre colour: on their deserted flanks one sees, here and there, black scorched vines, a few clumps of wild olive-trees, wasteland covered with hyssop, chapels, oratories and ruined mosques. At the bottom of the valley is a bridge, a single arch, thrown across the ravine of the River Kidron. The stones of the Jewish cemetery seem like a mass of debris, at the foot of the Mountain of Offence (also the Mountain of Scandal), below the Arab village of Siloan: it is hard to distinguish the village hovels from the graves with which they are surrounded. Three ancient monuments, the tombs of Zechariah (ben Jehoiada), Absalom and Jehoshaphat, rise from this field of destruction. Given the sadness of Jerusalem, from which no smoke rises, from which no sound emerges; given the solitude of the mountains, where no living being can be seen; given the ruins of those broken, damaged, half-open tombs, it is as if the trumpet of Judgement had already sounded in the valley of Jehoshaphat, and that the dead were about to rise.

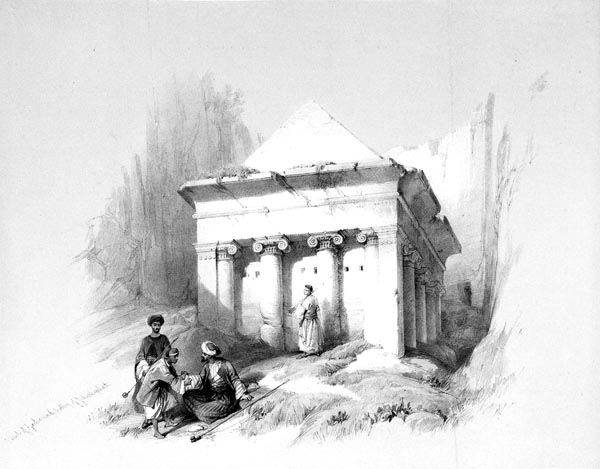

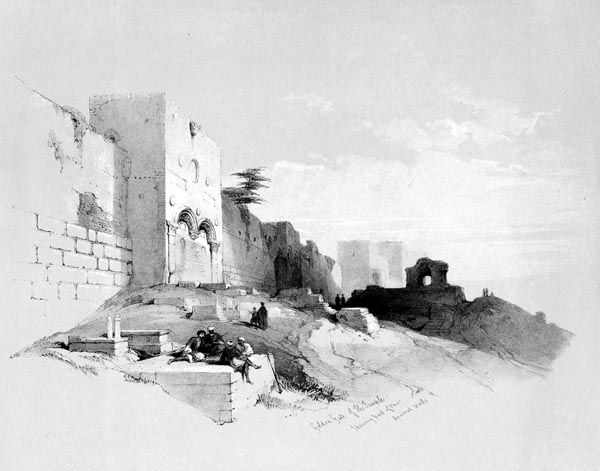

‘The Tomb of Zacchariah, Valley of Jehoshaphat’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

At its rim, and close to the source of the River Kidron, we entered the Garden of Olives; it belongs to the Latin Fathers, who bought it with their own money: there, eight large olive trees of extreme decrepitude are to be seen, The olive tree is virtually immortal, because it is reborn from its roots: on the citadel of Athens, they care for an olive tree whose origin dates back to the founding of the city. The olive trees, of the garden of that name, in Jerusalem date from at least the time of the Late Empire; here is proof: in Turkey, any olive tree found by the Muslims when they invaded Asia, is taxed at one piece of silver (medin), while half the crop from any olive tree planted since the conquest is owed to the Grand Seigneur (this law is as absurd as most others in Turkey: how bizarre to spare the vanquished from a time of conquest, when violence may bring injustice and overwhelm the subject in peace-time!): thus, the eight olive trees we are speaking of are taxed at eight medins. We dismounted at the entrance to the garden to visit the Stations of the mountain on foot. The village of Gethsemane is some distance away from the Garden of Olives. These days it is identified, in error, with the garden itself, as noted by Thévenot and Roger.

We first entered the sepulchre of the Virgin. It is a subterranean church, which you descend by fifty quite beautiful steps: it is shared among all Christian sects: the Turks themselves have a chapel in that place; the Catholics maintain the tomb of Mary. Although the Madonna did not die in Jerusalem, she was (in the opinion of several Fathers of the Church) miraculously buried at Gethsemane by the apostles. A certain Euthymius tells the story of the wonderful happenings at the funeral. Saint Thomas having opened the coffin, nothing was found but a virgin’s robe, the poor and simple clothing of that Queen of glory whom the angels had lifted to heaven (See Saint John Damascene: Homily on the Dormition).

The tombs of Saint Joseph, Saint Joachim and Saint Anne are also to be seen in this underground church.

Emerging from the tomb of the Virgin, we went to see the cave, in the garden of Olives, where the Saviour sweated blood, saying: Pater mi, si possibile est, transeat a me calix iste: O my Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from me (Vulgate: Matthew: 26:39).

The cavern is irregular; altars have been erected there. Outside, some few paces distant, one may see the place where Judas betrayed his master with a kiss. To what kind of humiliation did Jesus Christ not consent to descend! He experienced those terrible degradations in life that virtue itself finds difficulty in overcoming. And the moment an angel is obliged to descend from heaven to support Divinity, faltering under the burden of human misery, that merciful Divinity is betrayed by Mankind!

Leaving this cave of the cup of bitterness, and climbing a winding path strewn with pebbles, the dragoman halted us near a rock where it is claimed Jesus Christ looked upon the guilty city, weeping over the impending desolation of Sion. Baronius (Cardinal Cesare Baronio: Ecclesiastical Annals) observes that Titus erected his tents in the place where the Saviour had foretold the destruction of Jerusalem. Doubdan, who disagrees with this suggestion, without citing Baronius, believes that the Sixth Roman Legion camped on the summit of the Mount of Olives, and not on the slopes of the mountain. His opinion is excessively critical, while Baronius’s remark is no less beautiful or just.

From the Rock of Prediction we climbed to the caves which are to the right of the path. They are called the Tombs of the Prophets; they are unremarkable, and little is known as to which prophets were supposedly buried there.

A short distance above the caves we found a kind of cistern, composed of twelve arches; it was there that the apostles created the first embodiment of our belief. While the world worshipped a thousand false deities under the sun, twelve fishermen, concealed in the bowels of the earth, uttered their profession of faith on behalf of the human race, and recognized the unity of God, the creator of those stars beneath which they dared not, as yet, proclaim his existence. If some Roman of Augustus’s court, passing that subterranean place, had seen the twelve Jews who composed that sublime work, what contempt he would have shown for that superstitious band! With what contempt he would have spoken of those first believers! And yet they would overthrow that Roman’s temples, destroy the religion of his fathers, alter the laws, politics, morality, reasoning, and even the thoughts of mankind. Let us never despair then of the salvation of nations. Christians today mourn the waning of faith; who knows if God has not planted in some neglected place that grain of wild-mustard seed that multiplies in the fields? Perhaps we are unable to keep that hope of salvation before our eyes, perhaps it appears to us as ridiculous and absurd. But who could ever have conceived the folly of the Cross?

Climbing a little higher, one encounters the ruins, or rather the abandoned site, of a chapel: a continuous tradition teaches that Jesus Christ in this place recited the Lord's Prayer.

‘One day Jesus was praying in a certain place. When he finished, one of his disciples said to him, “Lord, teach us to pray, just as John taught his disciples.” He said to them, “When you pray, say: ‘Father, hallowed be your name, your kingdom come, etc.’” (Luke:11:1-2)

Thus were composed, at almost the same place, that profession of faith on behalf of all mankind, and a prayer capable of being spoken by all mankind.

Thirty yards away, a little towards the north, is an olive tree at whose foot the Son of the Almighty Judge predicted the universal judgement.

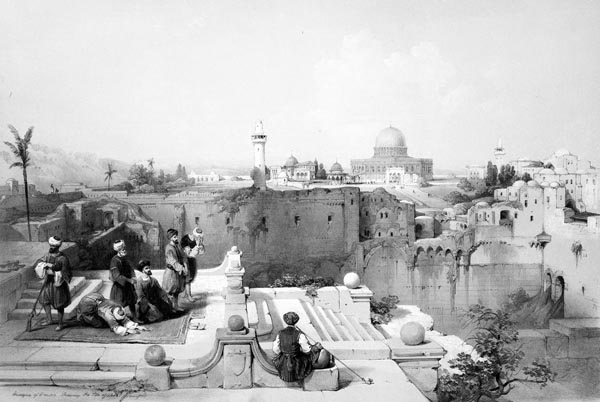

Finally, about fifty yards across the mountain-side, one arrives at a small mosque, octagonal in shape, the remains of a church once built on the spot where Jesus Christ ascended into heaven after his resurrection. One can distinguish in the rock a man’s left footprint; traces of that of the right foot were once visible too: the majority of pilgrims claim that the Turks removed the second imprint, to adorn the Temple mosque, but Père Roger positively asserts that it is not present in that place. I bow silently, out of respect, while as yet remaining unconvinced, before the considerable weight of authority: Saint Augustine, Saint Jerome, Saint Paulinus, Sulpicius Severus, the Venerable Bede, tradition, and all ancient and modern travellers, assure us that it is the footprint of Jesus Christ. Examination of the footprint led to the conclusion that the Saviour’s face was turned toward the north at the time of his ascension, as if to reject a southerly direction infested with errors, to summon to the faith those barbarians who were to overthrow the temples of their false gods, to create new nations, and plant the banner of the cross on the walls of Jerusalem.

Several of the Fathers of the Church believed that Jesus Christ rose to heaven amidst the souls of the patriarchs and prophets, delivered by him from the chains of death: his mother, and one hundred and twenty disciples, bore witness to his ascension. He stretched out his arms like Moses, says Saint Gregory of Nazianzus, and presented his disciples to the Father; then he crossed his powerful hands while lowering them over the heads of his beloved friends (Tertullian), and it was in this way that Jacob blessed the sons of Joseph; then, leaving the earth with wondrous majesty, he ascended slowly to the eternal realms, and vanished in a glowing cloud (Ludolph).

Saint Helen ordered a church built where the octagonal mosque now stands. Saint Jerome tells us that the vault of the church where Jesus Christ ascended through the air could never be roofed over. The venerable Bede assures that in his day, on the eve of the Ascension, the Mount of Olives appeared covered with lights, throughout the night. Nothing requires us to believe these traditions, which I record solely to illuminate history and tradition; but if Descartes and Newton had maintained philosophical doubts regarding these wonders, Racine and Milton would not have repeated them in poetry.

In this way, evangelical history is illustrated by means of its monuments. We have seen it begin in Bethlehem, progress to its denouement before Pilate, arrive at the catastrophe of Calvary, and end on the Mount of Olives. The actual scene of the Ascension is not quite at the top of the mountain, but two or three hundred feet below its highest summit.

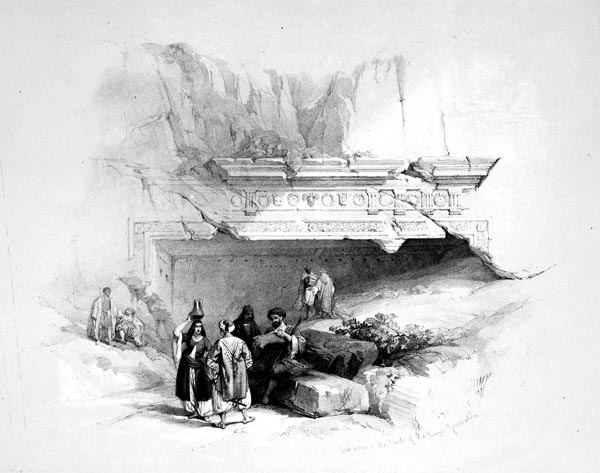

‘Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives’

Syria, the Holy Land, Asia Minor - John Carne, Thomas Allom, William Henry Bartlett, William C. Stafford (p490, 1861)

The British Library

We descended the Mount of Olives, and, remounting our horses, continued our journey. We left behind us the Valley of Jehoshaphat, and rode by steep tracks to the northern corner of the city; from there turning west and along the wall that faces north, we arrived at the cave where Jeremiah wrote his Lamentations. We were not far from the tombs of the kings, but we renounced seeing them, because it was too late in the day. We returned to the Jaffa Gate, through which we had left Jerusalem. It was precisely seven o’clock when we reached the monastery.

Our outing had taken five hours. On foot, and following the walls of the city, it only takes an hour to make the circuit of Jerusalem.

On the 8th of October, at five in the morning, I set out with Ali-Aga and the dragoman Michel to view the interior of the city. It is necessary to digress here to glance at the history of Jerusalem.

Jerusalem was founded in the year 2023, by the high priest Melchizedek: he named it Salem, that is to say Peace; it then occupied only the two mountains of Moria and Acra.

Fifty years after its founding, it was taken by the Jebusites, descendants of Jebus, son of Canaan. They built a citadel on Mount Sion, to which they gave the name of Jebus, their father; the city then took the name of Jerusalem, which means Vision of Peace. All Scripture praises it magnificently: Jerusalem, civitas Dei…Luce splendida fulgebis:et omnes fines terrae adorabunt te: Jerusalem, City of God…Thou shalt shine with a glorious light: and all the ends of the earth shall worship thee. (Vulgate: Tobias: 13:11,13) etc.

Joshua took the lower city of Jerusalem, on the first year of his entry into the Promised Land: he killed the king Adonizedek, and the four kings of Hebron, Jarmuth, Lachish and Eglon (Joshuah: 10:1-3). The Jebusites remained masters of the city, or the high citadel, of Jebus. They were not driven out until the time of David, eight hundred and twenty-four years after their entry into the city of Melchizedek.

David added to the fortress of Jebus, and gave it his own name. He also built, on Mount Sion, a palace and a tabernacle, in which to place the Ark of the Covenant.

Solomon added to the holy city: he built that first temple whose wonders Scripture and the historian Josephus describe for us, and for which Solomon himself wrote songs of great beauty.

Five years after the death of Solomon, Shishak, king of Egypt, attacked Rehoboam, and took and plundered Jerusalem (1 Kings:14:25).

It was sacked again, one hundred and fifty years, later by Joash king of Israel (2 Chronicles:25:23).

Again invaded by the Assyrians, Manasseh, king of Judah, was taken captive to Babylon (2 Chronicles:33:11). Finally, during the reign of Zedekiah, Nebuchadnezzar razed Jerusalem to the ground, burned the temple, and transported the Jews to Babylon (2 Kings:25). Sion quasi ager arabitur,’ said Jeremiah, ‘et Hierusalem in acervum lapidum erit: Sion shall be plowed like a field, and Jerusalem shall become heaps (Jeremiah 26:18). Saint Jerome, in order to paint the loneliness of this desolate city, said one could not see a single bird flying there.

The first temple was destroyed, four hundred and seventy years, six months and ten days after its foundation by Solomon, in the year 3513 about four hundred years before Christ: four hundred and seventy seven years had elapsed from David to Zedekiah, and the city had been ruled by seventeen kings.

After seventy years of captivity, Zerubbabel began to rebuild the temple and the city. This work, interrupted for several years, was completed by Ezra and Nehemiah.

Alexander passed through Jerusalem in the year 3583 (c332BC), and offered sacrifices in the temple.

Ptolemy I Soter (Lagides) became master of Jerusalem (320BC); and the city was treated well under Ptolemy II Philadelphus, who endowed the Temple with magnificent gifts.

Antiochus III, the Great, recaptured Judea from the kings of Egypt (c201BC), and then handed it over to Ptolemy VIII Euergetes. Antiochus IV Epiphanes sacked Jerusalem again, and set up the image of Olympian Zeus in the temple (167BC).

The Maccabees freed their country, and defended it against the kings of Asia.

Unfortunately Aristobulus and Hyrcanus disputed the crown; they had recourse to the Romans, who at the death of Mithridates had become the masters of the East. Pompey advanced to Jerusalem; entering the city, he besieged and took the temple (63BC). Crassus lost no time in pillaging that august monument, which Pompey had treated with respect.

Hyrcanus II, protected by Caesar, was maintained in the high priesthood. Antigonus II, the son of Aristobulus II, embittered by the Pompeians, made war on his uncle Hyrcanus, and summoned the Parthians to his aid. The latter, descending on Judea, entered Jerusalem, and took Hyrcanus prisoner (40BC).

Herod the Great, son of Antipater, a distinguished officer at the court of Hyrcanus, seized the Kingdom of Judea with the support of the Romans. Antigonus, whom the fortunes of war had allowed to fall into Herod’s hands, was sent to Mark Antony. The last descendant of the Maccabees, the rightful king of Jerusalem, was bound to a stake, beaten with rods, and put to death, by order of a Roman citizen.

Herod, remaining sole master of Jerusalem, filled it with beautiful monuments, of which I will speak later. It was during his reign that Jesus Christ was born.

Archelaus, the son of Herod and Mariamne, succeeded his father (4BC), while Herod Antipas, also a son of Herod the Great, held the tetrarchy of Galilee and Peraea. It was he who beheaded John the Baptist, and sent Jesus Christ to Pilate. This Herod the Tetrarch was banished to Lyon by Caligula (39AD).

Herod Agrippa, the grand-son of Herod the Great, obtained the kingdom of Judea, but his brother Herod V, King of Chalcis, had power over the temple, the sacred treasure and the high priesthood.

After Herod Agrippa’s death, Judea was reduced to a Roman province. The Jews having rebelled against their masters, Titus besieged and took Jerusalem. Two hundred thousand Jews died of starvation during the siege. From the 14th of April until the 1st of July of the year 70AD, one hundred and fifteen thousand, eight hundred and eighty corpses were carried through just a single gate of Jerusalem (is it not strange that a critic has reproached me regarding all these calculations, as if they were mine, as if I were doing anything else than following the historians of antiquity, including Josephus? The Abbé Antoine Guenée and several other scholars have shown, moreover, that these calculations are not exaggerated). The people ate the leather of their shoes and shields, they were reduced to feeding on hay, and ordure found in the sewers of the city: a mother ate her dead child. The besieged swallowed their gold; the Roman soldiers, witnessing this, slaughtered their prisoners, and then sought the treasure hidden in the entrails of those unfortunates. Eleven hundred thousand Jews perished in the city of Jerusalem and two hundred and thirty-eight thousand, four hundred and sixty in the rest of Judea. I exclude from this number women and children, and the elderly who died from hunger and the flames of sedition. Finally there were ninety-nine thousand, two hundred prisoners of war; some were sentenced to labour at public works; the rest were reserved for Titus’s triumphs: they appeared in the amphitheatres of Europe and Asia, where they killed each other to amuse the populace, throughout the Roman Empire. Those males who had not attained the age of seventeen years were auctioned along with the women; they sold for thirty to the penny. The blood of the Righteous had been sold for thirty pieces of silver in Jerusalem, and the people cried: Sanguis eius super nos et super filios nostros: His blood be on us and on our children (Matthew:27:25). God heard that desire of the Jews, and for the last time he granted their prayer, after which he averted his eyes from the Promised Land and chose a new people.

The temple was burned thirty-seven years after the death of Jesus Christ; so that many who heard the Saviour’s prophecy could witness its accomplishment.

The remnant of the Jewish nation rose again. Hadrian finished the destruction of what Titus had left standing of ancient Jerusalem. He raised on the ruins of the city of David another city, to which he gave the name Aelia Capitolina; he forbade entry to Jews on pain of death, and had a hog sculpted over the gate leading to Bethlehem. Saint Gregory of Nazianzus, however, assures us that the Jews were allowed to enter Aelia once a year to wail there; Jerome adds that for their weight in gold they were granted the right to shed tears over the ashes of their homeland.

Five hundred and eighty-five thousand Jews died, according to Cassius Dio (Cassius Dio: Roman history: 69.13.2-3), at the hands of the soldiers in Hadrian’s wars. A multitude of slaves of both sexes were marketed at the fairs in Gaza and Mamre; fifty castles were razed and nine hundred and eighty-five towns.

Hadrian built his new city, in exactly the same place that it now occupies; and by a special providence, as Doubdan observed, he enclosed Mount Calvary within the city walls. At the time of the persecution of Diocletian, the very name of Jerusalem was so completely forgotten, that a martyr having replied to a Roman governor that he was from Jerusalem, the Governor imagined that the martyr was talking about some factious town, built secretly by the Christians. Towards the end of the seventh century, Jerusalem still bore the name Aelia, as seen in Arculf’s Travels in Adamannus’s version, or in that of the Venerable Bede.

Various changes seem to have taken place in Judea, under the emperors Antoninus, Severus, and Caracalla. Jerusalem, having become pagan in her old age, at last recognized the God she had rejected. Constantine and his mother threw down the idols erected over the Tomb of the Saviour, and re-dedicated the holy places with buildings that are still visible.

It was in vain that Julian, thirty-seven years later, gathered the Jews again in Jerusalem to rebuild the temple: the men laboured at this work with baskets, spades and shovels of silver; the women carried earth in the folds of their finest dresses, but globes of fire emerging from the half-dug foundations scattered the workers, and prevented the completion of the project.

There was a Jewish revolt under Justinian, in the year 501AD. It was also under that emperor that the Church in Jerusalem was elevated to patriarchal dignity.

Destined to struggle continually against idolatry, and to vanquish false religions, Jerusalem was taken by Chosroes, king of Persia, in the year 614AD. The Jews, spreading throughout Judea, bought ninety thousand Christian prisoners from that prince, and slaughtered them.

Heraclius defeated Chosroes in 627AD, recaptured the True Cross which the Persian king had removed, and returned it to Jerusalem.

Nine years later, the Caliph Umar, the third successor of the prophet Mohammed, took Jerusalem, after besieging it for four months: Palestine and Egypt fell under the yoke of the conqueror.

Umar was assassinated in Jerusalem in 644AD. The establishment of several caliphates in Arabia and Syria, the fall of the Ummayad dynasty and the rise of that of the Abbasid, filled Judea with disorder and misery for more than two hundred years.

The Turk, Ahmad Ibn Tulun, who from governor of Egypt rose to become its ruler, conquered Jerusalem in 868AD; but his son being defeated by the caliphs of Baghdad, the holy city was subject once more to the rule of the caliphs, in 905AD.

Another Turk, named Muhammad bin Tughj Al-Ikhshid, having in turn taken possession of Egypt, extended his domains, and subdued Jerusalem in 936AD.

The Fatimids, emerging from the sands of Cyrenaica in 968AD, drove the Ikhshidids from Egypt, and conquered several cities in Palestine.

Another Turk, by the name of Ortok, favoured by the Seljuks of Aleppo, became master of Jerusalem in 984AD, and his children reigned after him.

Al-Aziz Billah, Caliph of Egypt, forced the Ortokids to leave Jerusalem.

Hakem or Hekem (Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah), successor to Al-Aziz and the sixth Fatimid caliph, persecuted the Christians of Jerusalem from the year 996, as I have already recounted, when speaking of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This caliph died in 1021.

Malik Shah (Jalal al-Dawlah Malik-shah I), a Seljuk Turk, took the holy city in 1077AD, and ravaged the whole country. The Ortokids, who had been driven from Jerusalem by the Caliph Al-Aziz, returned, and held it against Redouan (Fakhr al-Mulk Radwan), prince of Aleppo. But they were expelled again by the Fatimids in 1077AD: they still reigned when the Crusaders appeared on the borders of Palestine.