François-René de Chateaubriand

The Last of the Abencerrajes

(Les Aventures du Dernier Abencérage)

Illustrated with lithographs by Francisco Javier Parcerisa, courtesy of Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2011 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

About This Work

Chateaubriand’s tale of a great love thwarted by religion and destiny, is set in 15th century Spain, and centres on the last of the Moorish tribe of the Abencerrages who, legend has it, held high position in the kingdom of Granada. The city was the last to be governed by the Moors, and its surrender to Ferdinand and Isabella, in 1492, by Muhammad XII (Boabdil) marked the end of the Reconquista and the final expulsion of the Moors from Spain.

The idea of a doomed relationship between a Christian and a Muslim protagonist appears in a number of earlier works in Europe, for example the 12th or 13th century French chantefable of Aucassin and Nicolette, while the theme of lovers separated by fate, exemplified by Romeo and Juliet or the historical 12th century figures of Abélarde and Héloïse, had particular appeal for Chateaubriand, who gives us variations of the idea in his American novellas Atala and René.

A particular strength of this story of Granada, besides the charm of its telling and the beauty of its setting, is Chateaubriand’s ability to give equal weight and sympathy to two diverse cultures, while himself believing in the ultimate superiority of the Christian faith. This exaltation of human virtues above particular time and circumstance is one of Chateaubriand’s most endearing characteristics.

The Last of the Abencerrajes

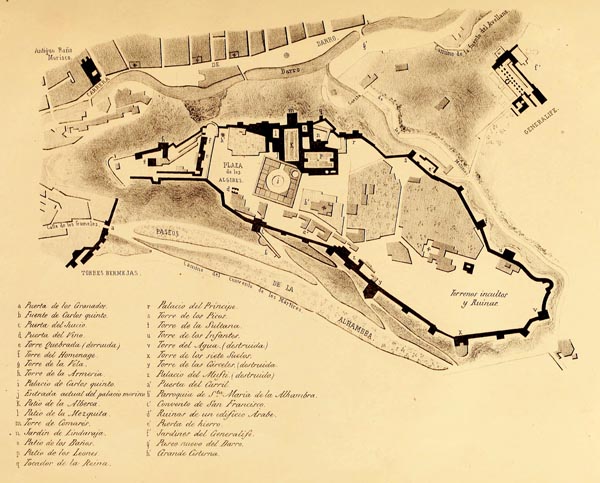

‘Plano de la Fortaleza de la Alhambra’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p608, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

When Boabdil, the last king of Granada, was forced to abandon the kingdom of his fathers, he halted on the heights of Mount Padul. From this elevated place the sea was visible, on which the unfortunate monarch was about to sail for Africa; Granada was visible too, the Vega and the River Genil, beside which stood the tents of Ferdinand and Isabella. At the sight of this beautiful country and the cypresses that marked the scattered graves of the Muslims, Boabdil began to weep. The Sultana, Aixa, his mother, who accompanied him into exile with the great men who had once composed his Court, said: ‘Thou weepest now like a woman for a kingdom thou wast unable to defend like a man.’ They descended the mountain, and Granada vanished from their eyes forever.

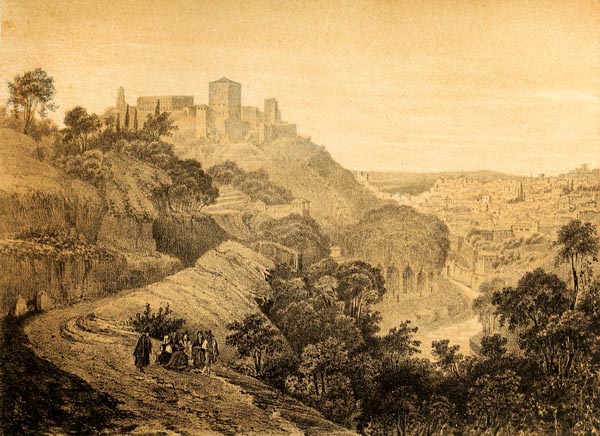

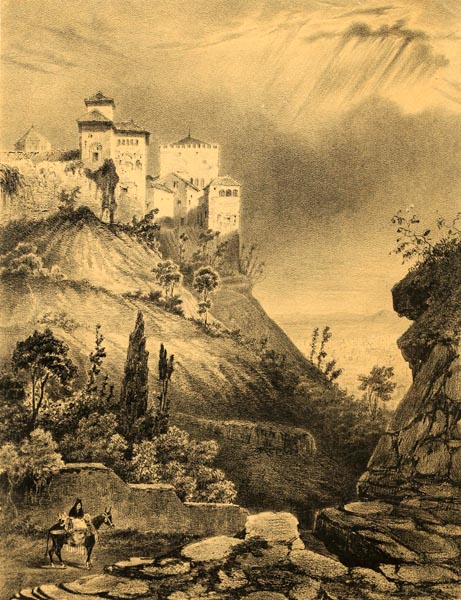

‘Vista de la Alhambra desde los Nopales del Monte Sacro’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p445, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

The Moors of Spain, who shared the fate of their king, dispersed throughout Africa. The tribes of the Zegris (Thegris) and the Gomeles settled in the kingdom of Fez, from which they derived their origin. The Vanegas and the Alabes settled on the coast, from Oran to Algiers; and finally the Abencerrajes (Beni Serraj) established themselves on the outskirts of Tunis. They founded, within sight of the ruins of Carthage, a colony that can still be distinguished today from the other Moorish colonies of Africa, by the elegance of its manners and the temperance of its laws.

These families carried with them to their new country the memory of their former homeland. The Paradise of Granada lived forever in their memories, mothers repeating its name to their infants while they were still suckled at the breast. They rocked them to sleep with tales of the Zegris and the Abencerrajes. Five times a day they prayed in the mosque, turning towards Granada. Allah was invoked, in order that he might render once more to his elect that land of delights. In vain the land of the Lotus-eaters offered the exiles its fruits, its water, its greenery, its bright sun; far from the Vermilion Towers, there was neither pleasant fruit, nor limpid fountains, nor fresh verdure, nor sunlight worthy of regard. If one who had been banished was shown the plains of the Bagradas (Medjerda River), he shook his head and exclaimed with a sigh: ‘Granada!’

The Abencerrajes, especially, retained the most tender and faithful memory of their homeland. They had quitted with mortal regret the scene of their glory, and the shores which had so often sounded to their cry to arms: ‘Love and Honour.’ No longer able to raise a lance in the desert, nor don the helmet among a colony of farmers, they had devoted themselves to the study of medicine, a calling as esteemed among the Arabs as the profession of arms. Thus, this race of warriors, who had once inflicted wounds, now occupied themselves with the art of healing. In that they had retained something of their primary inspiration, since the knights often themselves tended the wounds of the enemy they had conquered.

The home of this tribe, which once possessed palaces, was not situated in the village colonised by the other exiles, at the foot of the mountain of Mamelife (Hammam-Lif); it was built among the very ruins of Carthage, beside the sea, in the place where St. Louis died, on a bed of ashes, and where today a Moslem shrine is to be seen. To the walls of the house were attached shields of lion-skin bearing two savage figures on an azure field, shattering a city with wooden clubs. Around the device, these words could be read: ‘A mere nothing!’ the arms and motto of the Abencerrajes. Lances adorned with white and blue pennants, cloaks (albornoz), and tunics of slashed silk, were mounted next to shields, that gleamed amongst scimitars and daggers. Gauntlets could still be seen hanging here and there, bridles enriched with precious stones, large silver stirrups, long swords whose sheathes had been embroidered by the hands of princesses, and the golden spurs that valiant knights who had dedicated themselves to Isolde, Guinevere, and Oriana, formerly wore.

On tables, at the foot of these trophies of glory, were placed the trophies of a life of peace: herbs gathered on the summits of the Atlas Mountains and in the deserts of the Sahara; several had even been brought from the plain of Granada.

Some of these were best suited to relieve the ills of the body; others had the power to ease the sorrows of the soul. The Abencerrajes especially valued those that served to calm vain regrets, to dispel those foolish illusions and hopes of happiness forever nascent, forever disappointed. Unfortunately these medicines had opposing virtues, and often the scent of a flower from their homeland acted as a species of poison on those illustrious exiles.

Twenty-four years had passed since the taking of Granada. In this short space of time fourteen of the Abencerrajes had perished under the influence of the new climate, through the accidents of a wandering life, and above all through grief, silently undermining human strength. One sole offspring was all the hope of that illustrious house. Aben-Hamet bore the name of that Abencerraje who was accused by the Zegris of having seduced the Sultana, Alfaima. He united in himself the beauty, valour, courtesy, and generosity of his ancestors, with the gentle demeanour and slight expression of sadness produced by misfortunes nobly born. He was only twenty-two when he lost his father; he resolved then to make a pilgrimage to the land of his ancestors, to satisfy his heart’s desire, and to accomplish a purpose which he hid carefully from his mother.

He embarked from the jetty at Tunis; a favourable wind conducted him to Cartagena; he left the ship, and immediately took the road to Granada: he announced himself as an Arab physician who had arrived to collect plants among the rocks of the Sierra Nevada. A peaceable mule carried him slowly through the countryside where the Abencerrajes once flew by on warlike steeds: a guide walked ahead, leading two other mules decorated with bells and multi-coloured tufts of wool. Aben-Hamet traversed the great wastelands, and the palm-groves of the kingdom of Murcia: judging by the age of these palms, he reflected that they would have been planted by his ancestors, and his heart was filled with regret. Here a tower arose, where the sentry kept watch during the wars between the Moors and Christians; there a ruin was revealed, whose architecture announced its Moorish origin; a further source of pain to the Abencerraje! He alighted from his mule, and under the pretext of searching for herbs, he concealed himself for a moment among the ruins, to give vent to his tears. Then he resumed his journey, dreaming to the sounds of the bells from the caravan, and the monotonous chant of his guide. The latter only interrupted his long ballad to urge on his mules, calling them beautiful and valorous, or by way of scolding them, calling them lazy and obstinate.

Flocks of sheep driven by their shepherds like armies over the yellow uncultivated plains, and a few lone travellers, far from bringing life to the road only served to make it appear sadder and lonelier. These travellers all carried a sword at their side: they were wrapped in cloaks, and wide-brimmed hats, pulled well down, covered half their faces. They hailed Aben-Hamet in passing, who of their noble salutes could only comprehend the words God, Lord or Knight. That evening at a country inn (venta) the Abencerraje took his place among the strangers there, without being disturbed by their indiscreet curiosity. No one spoke to him, no one questioned him; his turban, robe, weapons, excited no astonishment. Since Allah had willed that the Moors of Spain should lose their beautiful homeland, Aben-Hamet could not help but esteem its sombre conquerors.

Emotions yet more vivid awaited the Abencerraje at the end of his journey. Granada is built at the foot of the Sierra Nevada, on two hills separated by a deep valley. The houses sited on the hill slopes, and in the depths of the valley, give the city the air and form of a half-open pomegranate (Spanish: granada), from which it derives its name. Two rivers, the Genil and the Darro, of which the former flows over golden gravel, and the latter over silver sands, wash the foot of the hills, meet, and then meander through the centre of a delightful plain, called the Vega. This plain, which Granada overlooks, is covered with vines, pomegranate-trees, fig-trees, mulberries, and orange-trees; it is surrounded by mountains of an admirable form and colour. Enchanted skies, a clear and delightful atmosphere, plunge the mind into a secret languor, from which travellers, even merely as passers-by, can scarcely defend themselves. It would seem that in this country the tender passions would swiftly extinguish the heroic ones, if love, to appear valid, had not the need to be always accompanied by glory.

When Aben-Hamet saw the roofs of the first buildings in Granada, his heart beat so violently that he was obliged to halt his mule. He folded his arms across his chest, and eyes fixed on the sacred city, he remained silent and motionless. The guide stopped in turn, and as all noble sentiments are easily understood by a Spaniard, he seemed moved, and guessed that the Moor was in sight once more of his former homeland. The Abencerraje finally broke the silence.

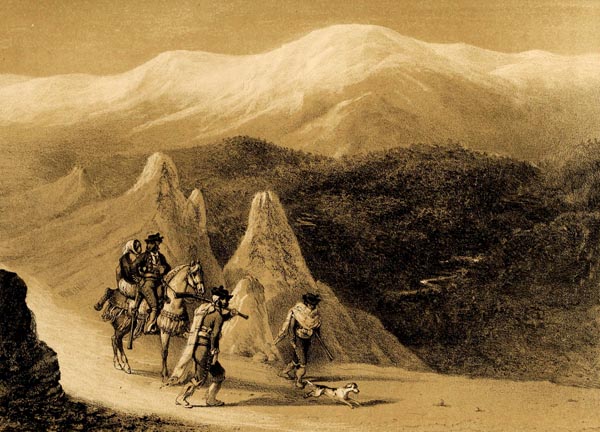

‘Camino de la Fuente del Avellano (Alrededores de Granada)’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p438, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

‘Guide,’ he cried, ‘be happy! Do not hide the truth from me, since calm reigned over the waves at the hour of thy birth, and the moon was entering on its crescent. What are those towers that shine like stars above a green forest?’

‘That is the Alhambra,’ replied the guide.

‘And that other castle, on the second hill?’ asked Aben-Hamet.

‘That is the Generalife,’ said the Spaniard. In that castle there is a garden, planted with myrtles, where they claim the Abencerraje was surprised with the Sultana Alfaima. Further off, you can see the Albaicin, and closer to us the Vermilion Towers.’

‘Jardin de Generalife’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p561, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

Every word the guide spoke pierced Aben-Hamet’s heart. How cruel it was to him that he must have recourse to strangers to identify the monuments of his ancestors, and be told by those indifferent to them the history of his family and friends! The guide, putting an end to Aben-Hamet’s reflections, exclaimed: ‘Continue, Sir Moor, continue, God willing! Have courage! Is not Francis this very day a prisoner in our Madrid (Francis I of France was imprisoned at Madrid, from 1525 to 1526, after losing the battle of Pavia), God willing?’ He took off his hat, made a great sign of the cross, and prodded his mule. The Abencerraje, urging on his own mule in turn, said: ‘So it was written,’ and they descended towards Granada.

They passed close to the great ash tree, made famous by the battle between Muca (a prince of the Abencerrajes) and the Grand Master of the Order of Calatrava, serving under the last king of Granada. They made a circuit of the Alameda, and entered the city through the Gate of Elvira (Puerta de Elvira). They ascended the Rambla and soon reached a spot surrounded on all sides by houses of Moorish design. A caravanserai was built on this spot by the Moors of Africa, drawn to Granada en masse by the trade in silks of the Vega. To this the guide led Aben-Hamet.

The Abencerraje was too agitated to enjoy even a brief repose in his new dwelling; his presence in his homeland so tormented him. Unable to resist the feelings that troubled his heart, he went out at midnight to wander the streets of Granada. He tried to recognize by sight or touch some of the monuments the old men had so often described. Perhaps this tall building whose walls he saw through the darkness was once the home of the Abencerrajes; perhaps it was in this lonely square that those parades were conducted that raised the glory of Granada to the skies. There, they danced quadrilles, superbly dressed in brocades; there, galleys advanced loaded with weapons and flowers; dragons breathing flames, hiding illustrious warriors in their flanks; ingenious devices of pleasure and gallantry.

‘Vista de la Alhambra las Torres Bermejas y Calle de los Gomeles (Granada)’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p590, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

But, alas! Instead of the sound of the anafil (an Arabic straight trumpet), the music of flutes, and the songs of love, a profound silence reigned around Aben-Hamet. The inhabitants of that mute city were no longer those of before, and the victors rested on the bed of the vanquished. ‘They sleep, then, these proud Spaniards’ exclaimed the young Moor indignantly, ‘beneath those roofs from which they banished my ancestors! And I, an Abencerraje, I watch unknown, solitary, desolate, at the gate of my forefathers’ palace!’

Aben-Hamet, reflected thus on human destiny, on the vicissitudes of fortune, on the fall of empires, on that Granada, finally surprised by its enemies in the midst of pleasures, and suddenly exchanging its garlands of flowers for chains; he seemed to see its citizens abandoning their homes in their festive clothes, like guests who, in the chaos of their finery, are suddenly driven from the banqueting hall by a fire.

All these images, all these thoughts thronged Aben-Hamet’s soul; full of pain and regret, he dreamed above all of executing the plan that had brought him to Granada: daylight surprised him. The Abencerraje was lost: he found himself far from the caravanserai, in a suburb outside the city. All slept, not a sound disturbed the silence of the streets; the doors and windows of the houses were closed: only the voice of the cockerel proclaimed, in the habitations of the poor, the return of hardship and travail.

After wandering long, without being able to find his way, Aben-Hamet heard a door open. He saw a young woman emerge, dressed much as those queens carved on the Gothic monuments of our ancient abbeys. A black corset, trimmed with jet, shaped her elegant figure, her short skirt, tight and without folds, revealed a shapely leg and charming foot; an equally black mantilla was thrown over her head: with her left hand she held this mantilla closed tight like a veil beneath her chin, so that all one could see of her face were her eyes and rosy lips. A duenna accompanied her; a page in front carried a prayer book; two servants, dressed in her livery, followed the beautiful stranger at a distance: she was on her way to morning prayers, which the ringing of a bell announced from a nearby monastery.

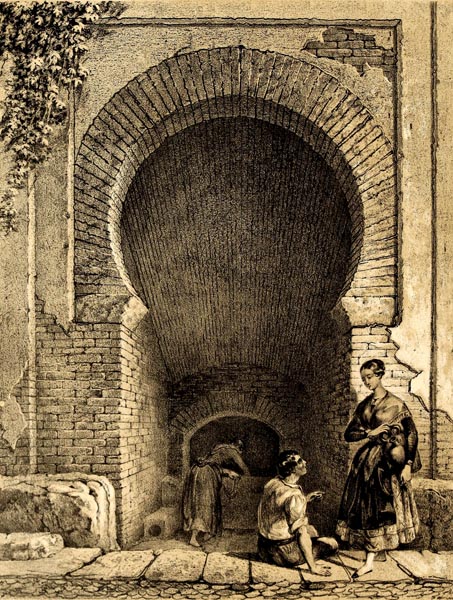

‘Aljibe árabe en el Albayzín’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p573, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

Aben-Hamet thought he had seen the angel Israfil, or perhaps the youngest of the Houris. The Spanish girl, no less surprised, gazed at the Abencerraje, whose turban, clothing and weapons further adorned his noble figure. Recovering from her initial astonishment, she beckoned to the stranger to approach with the grace and freedom peculiar to the women of that country. ‘Sir Moor,’ she said, ‘you seem newly-arrived in Granada: are you lost?’

‘Sultana of the flowers,’ replied Aben-Hamet, ‘delight to the eyes of man, O Christian slave, more beautiful than the virgins of the mountains of Georgia, thou hast divined it! I am a stranger to this city: lost in the midst of these palaces, I cannot find the caravanserai of the Moors. May Mohammed touch thy heart, and reward thee for thy hospitality!’

‘The Moors are renowned for their gallantry,’ said the Spanish girl, with the sweetest of smiles, ‘but I am neither a Sultana of the flowers, nor a slave, nor pleased to be commended to Mohammed. Follow me, Sir Knight: I will guide you to the caravanserai of the Moors.’

She walked lightly, ahead of the Abencerraje, led him to the door of the caravanserai, pointed to it with her hand, passed behind a palace, and vanished.

Where then went life’s repose? His homeland no longer occupied the mind of Aben-Hamet solely and entirely. Granada has ceased to seem deserted, abandoned, widowed, and solitary; it was dearer than ever to his heart, but a new glory embellished its ruins; the memory of his ancestors was mingled now with another charm. Aben-Hamet discovered the cemetery where lay the ashes of the Abencerrajes; but while praying, while bowing, while shedding filial tears, he imagined that the young Spanish girl sometimes passed by those graves, and he no longer considered his ancestors so unfortunate.

In vain did he wish to occupy himself solely with his pilgrimage to the land of his fathers; in vain he traversed the banks of the Darro and Genil, to collect plants at the break of dawn: the flower he now sought was the beautiful Christian. What vain efforts too he made to find his enchantress’s palace once more! How many times he tried to find again those streets that had led him to his divine guide! How many times he thought he recognized the sound of the bell, the cry of the cockerel, he had heard near the residence of the Spaniard! Deceived by such echoes, he hastened immediately towards them, yet no magic palace offered itself to his gaze! Often even the dresses of the women of Granada gave him a moment of hope; from afar all the Christian women resembled the lady of his heart; yet not one possessed her beauty or her grace. Aben-Hamet finally traversed all the churches in search of the stranger; he even penetrated to the tomb of Ferdinand and Isabella, the greatest sacrifice he had yet made to love.

One day he was collecting herbs in the Darro Valley. The hillside on the south supported on its flowery slopes the walls of the Alhambra, and the gardens of the Generalife; the hill to the north was adorned by the Albaicin, by smiling gardens, and by caves inhabited by numbers of people. At the western end of the valley the bell-towers of Granada could be seen rising among ilexes and cypresses. At the other end, towards the east, on the rocky heights, were visible convents, monasteries, the ruins of ancient Illiberis, (Pliny’s Illiberi Liberini) and in the distance the heights of the Sierra Nevada. The Darro flowed through the middle of the valley, revealing, along its course, cool watermills, noisy cascades, the broken arches of a Roman aqueduct, and the remains of a bridge from the days of the Moors.

Aben-Hamet was neither wretched enough, nor happy enough, to enjoy the charm of solitude in all its fullness: he traversed the enchanted riverside distractedly and with indifference. Walking at random, he followed an avenue of trees which encircled the slopes of the Albaicin. A country house, surrounded by an orange grove, soon presented itself to his eyes: approaching the trees, he heard the sound of a voice and a guitar. Between the voice, features, and glances of a woman, there is a correspondence that never deceives a man possessed by love. ‘It is my houri!’ said Aben-Hamet; and he listened, with beating heart: at the name of the Abencerrajes several times repeated, his heart beat still faster. The unknown girl sang a Castilian song which traced the history of the Abencerrajes and the Zegris. Aben-Hamet could not restrain his emotion; he clambered through a hedge of myrtle and tumbled into the midst of a crowd of frightened young women who fled screaming. The Spanish girl, who had just been singing and who still held the guitar, cried: ‘It is Sir Moor!’ And she recalled her companions. ‘Favoured of the Spirits,’ said the Abencerraje, ‘I have sought for thee as the Arab seeks a spring in the heat of noon; I heard the sound of thy guitar; thou wast celebrating the heroes of my country; I divined it was thee from the beauty of thy accents, and I cast at thy feet the heart of Aben-Hamet.’

‘And I,’ said Dona Blanca, ‘was thinking of you as I repeated the ballad of the Abencerrajes. Ever since I saw you, I have thought that you resemble one of those Moorish knights.’

A slight blush rose to Blanca’s brow as she uttered these words. Aben-Hamet felt ready to fall at the feet of the young Christian, and tell her that he was the last of the Abencerrajes; but a vestige of prudence restrained him; he feared that his name, infamous in Granada, might trouble the governor. The Moorish Wars were scarcely over, and the presence of an Abencerraje at that moment might justly inspire fear among the Spaniards. It was not that Aben-Hamet feared danger, but he shuddered at the thought of being forced to separate for ever from this daughter of Don Rodrigo.

Dona Blanca was descended from a family that traced its origin to El Cid, Rodrigo of Bivar, and Ximena, daughter of Gomez, Count of Gormas. The descendants of the conqueror of Valencia the Beautiful had fallen, through the ingratitude of the Court of Castile, into extreme poverty; it was even thought, for several centuries, that the line had become extinct, so obscure had they become. But around the time of the conquest of Granada, the last scion of the race of the Bivars, the grandfather of Blanca, became well known less for his true titles than for the brilliance of his valour. After the expulsion of the Infidels, Ferdinand granted the Cid’s descendant the property of several Moorish families, and created him Duke of Santa Fé. The new Duke established his residence in Granada, and died young, leaving but one son who had already married, Don Rodrigo, Blanca’s father.

Dona Theresa of Xérès, the wife of Don Rodrigo, bore a son who received at his birth the name of Rodrigo as had all his ancestors, but was called Don Carlos, to distinguish him from his father. The great events that Don Carlos witnessed from his earliest youth, the dangers to which he was exposed throughout almost the whole of his childhood, only served to render more severe and rigid a character naturally inclined to austerity. Don Carlos was barely fourteen when he followed Cortez to Mexico (1519): he had endured every danger, he had witnessed all the horrors of that astonishing venture; he had been present at the fall of the last king of a world till then unknown. Three years after that catastrophe, Don Carlos could be found in Europe, at the Battle of Pavia, as if to gaze on royal honour and valour succumbing to the blows of fortune. The aspects of the new world, the long voyages over as yet unknown seas, the spectacle of revolutions and vicissitudes of fate, had badly shaken the religious and melancholy mind of Don Carlos: he had entered the chivalric Order of Calatrava, and, renouncing marriage despite the entreaties of Don Rodrigo, he gave all his possessions to his sister.

Blanca of Bivar, Don Carlos’s only sister, and much younger than he, was the idol of her father; she had lost her mother, and was entering on her eighteenth year, when Aben-Hamet appeared in Granada. Everything to do with this enchanting woman was seductive; her voice was ravishing, her dancing lighter than the breeze: sometimes she liked to drive a carriage like Armida; sometimes she flew along on the back of the fastest courser in Andalusia, like these lovely fays who appeared to Tristan and Galaor (the brother of Amadis de Gaul) in the forest. Athens would have taken her for Aspasia (the mistress of Pericles), and Paris for Diane de Poitiers, who was beginning to shine at court. But allied to the charms of a French woman, she had the passion of a Spaniard, and her natural coquetry stole nothing from the steadiness, constancy, force, and elevation of the sentiments of her heart.

Don Rodrigo had rushed to the scene at the cries of the young Spanish girls when Aben-Hamet had dashed into the grove. ‘Father,’ said Blanca, ‘this is the Moorish lord I told you of. He heard me sing, he recognized me; he entered the garden to thank me for having shown him the way.’

The Duke of Santa Fé received the Abencerraje with the grave and yet simple politeness of the Spaniards. There is nothing of a servile manner to be seen in that nation, none of those turns of phrase that denote abjection of thought or degradation of spirit. The language of the great lord and of the peasant is one, greetings, compliments, habits, customs, all are at one. Both their trust in, and the generosity of that people towards, foreigners are boundless, just as their vengeance is terrible when betrayed. Heroic in their courage, unfailing in their patience, incapable of yielding to evil fortune, they must overcome it or be crushed. They have little of what we call wit, but the exalted passions take the place of that enlightenment that comes from subtlety and abundance of ideas. A Spaniard who spends the day without speaking, who has seen nothing, who cares to see nothing, who has read nothing; studied nothing; compared nothing, still finds in the grandeur of his resolutions the resources required to face the hour of adversity.

It was Don Rodrigo’s birthday, and Blanca held a reception (tertulia) for her father, a little gathering, in charming seclusion. The Duke of Santa Fé invited Aben-Hamet to sit among the young women, who were charmed by the stranger’s turban and robe. Velvet cushions were brought, and the Abencerraje reclined on the cushions in Moorish style. He was questioned regarding his country and his adventures: he replied with wit and gaiety. He spoke the purest Castilian; he could have been mistaken for a Spaniard, had he not almost always said thee instead of you. This word seemed so sweet in his mouth, that Blanca could not but be secretly vexed, when he employed it in addressing one of her companions.

‘Casa del Chapiz (Albaycin)’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p456, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

Numerous servants appeared: they brought chocolate, baked fruits, and pastries covered with sugar, from Malaga, white as snow, light and porous as sponges. After Refreshments (Refresco), Blanca was requested to execute one of those local dances, in which she surpassed the ablest Gipsy (Gitano). She was obliged to yield to the wishes of her friends. Aben-Hamet had remained silent, but the pleas his eyes expressed spoke in default of his lips. Blanca chose to dance a Zambra (a flamenco, the Zambra Mora, performed by Gitanos), an expressive dance the Spaniards had borrowed from the Moors.

One of the young women began playing the foreign air on her guitar. Don Rodrigo’s daughter removed her veil, and clasped the castanets of ebony in her white hands. Her black hair fell in curls to her alabaster neck; her mouth and eyes smiled in concert; her complexion was animated by the beating of her heart. Suddenly she clicked the castanets loudly, sounded the measure three times, struck up the rhythm of the Zambra, and mingling her voice with the notes of the guitar, whirled like lightning.

What variety in her steps! What elegance in her poses! Now she raised her arms eagerly; now she let them fall gently. Sometimes she leapt forward as if intoxicated with delight then drew back as if grief-stricken. She turned her head, seeming to call to someone unseen, modestly offered a rosy cheek to the kiss of a new husband, fled in shame, returned bright and consoled, strutted with a noble almost warlike step, then leapt once more over the grass. The harmony of her footsteps, her singing, and the sounds of the guitar was perfection. Blanca’s voice, slightly husky, held that kind of tone that stirs the passions to the depths of the soul. Spanish music, composed of sighs, lively transitions, sad refrains singing that is suddenly arrested, offers a singular mixture of gaiety and melancholy. That music and dance settled the fate of the last Abencerraje irrevocably: they would have sufficed to disrupt a heart less afflicted than his.

In the evening, they returned to Granada, along the Darro Valley. Don Rodrigo, charmed by Aben-Hamet’s noble and polished manner, would not part with him until he had promised to visit often and amuse Blanca with the marvellous tales of the Orient. The Moor, it chiming with his wishes, accepted the Duke of Santa Fé’s invitation; and from that day he frequented the palace where breathed one he loved more than the light of day.

‘Cuesta de Los Molinos (Granada)’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p441, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

Blanca soon found herself drawn into a profound passion, by the very impossibility, as she had thought, of any human being ever experiencing it. To love an Infidel, a Moor, a foreigner, seemed so strange a thing to her that she took no precaution against the malaise that was beginning to creep into her veins; but soon as she recognised its effects, she accepted that malaise like a true woman of Spain. The dangers and sorrows she foresaw did not lead her to step back from the edge of the abyss for a moment, nor did they cause her to deliberate for long within her heart. She said: ‘Let Aben-Hamet become a Christian, let him love me, and I will follow him to the ends of the earth.’

The Abencerraje felt on his side all the power of an irresistible passion: he lived only for Blanca. He no longer occupied himself with the aims that had brought him to Granada: it would have been simple for him to obtain the enlightenment he was seeking, but he had lost sight of all other interests but that of his love. He even dreaded those insights which might have caused his life to alter. He asked for nothing, there was nothing he desired to know, he said to himself: ‘Let Blanca become a Muslim, let her love me, and I will serve her till my dying breath.’

Aben-Hamet and Blanca, fixed thus in their resolution, only awaited the moment to reveal their feelings to one another. On one of the finest days of the year, the daughter of the Duke of Santa Fé, said to the Abencerraje: ‘You have not yet seen the Alhambra. If I credit some words that escaped you, your family is originally from Granada. Perhaps you would like to visit the palace of your former kings? I myself will be your guide this evening.’

Aben-Hamet swore by the Prophet that no visit could be more agreeable.

The hour fixed on for their pilgrimage to the Alhambra having arrived, the daughter of Don Rodrigo mounted a white mule accustomed to climb the rocks like a deer. Aben-Hamet accompanied the brightly-lit Spanish girl, on an Andalusian horse equipped in the Turkish manner. During the young Moor’s swift progress, his purple robe swelled behind him, his curved sword clattered against the tall saddle, and the wind stirred the plume that surmounted his turban. The people, delighted with his graceful air, said, as they watched him pass by: ‘He is some infidel prince whom Dona Blanca seeks to convert.’

‘Paseos al Rededor de la Alhambra’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p558, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

At first, they followed a long street which still bore the name of an illustrious Moorish family (Calle de los Gomeles); this street led to the outer wall of the Alhambra. Then they traversed a grove of elm-trees, arrived at a fountain, and soon found themselves before the inner wall of the palace of Boabdil. Piercing a wall, flanked by towers and surmounted by battlements, a gate opened which was called the Gate of Justice (Puerta de la Justicia). They passed through this first gate, and continued by a narrow path that wound between high walls, and among half-ruined hovels. This path led to the square of the Aljibes (Plaza de los Aljibes), alongside which Charles V was then building his palace. From there, they turned north, to halt in a deserted courtyard, at the foot of an unadorned wall ruined by time. Aben-Hamet, leaping lightly to the ground, offered his hand to Blanca so that she might descend from her mule. The servants knocked at an abandoned doorway, its sill hidden in the grass: the door opened, allowing a sudden view of the remaining secrets of the Alhambra.

‘Puerta del Juicio (Alhambra)’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p480, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

All the charms of his homeland, all his regrets, mingled with the glamour of love, seized the heart of the last Abencerraje. Motionless and silent, he gazed with astonished eyes into this dwelling-place of Genies; he thought himself transported to the entrance of one of these palaces whose description we read of in the Arabian Nights. Floating galleries, canals of white marble lined with lemon and orange trees in flower, fountains, and solitary courtyards, were revealed on every side to Aben-Hamet’s eyes, and through the elongated arches of the porticoes, he perceived fresh labyrinths and new enchantments. The azure of a most beautiful sky showed between the columns that supported a string of Gothic arches. The walls, decorated with arabesques, imitated to the eye those Oriental fabrics that the caprice of some slave girl weaves amidst the boredom of the harem. Something sensual, religious, and yet warlike, seemed to breathe through this magical edifice; a kind of cloister of love, a mysterious retreat in which the Moorish kings tasted all the delights, and forgot all the duties, of life.

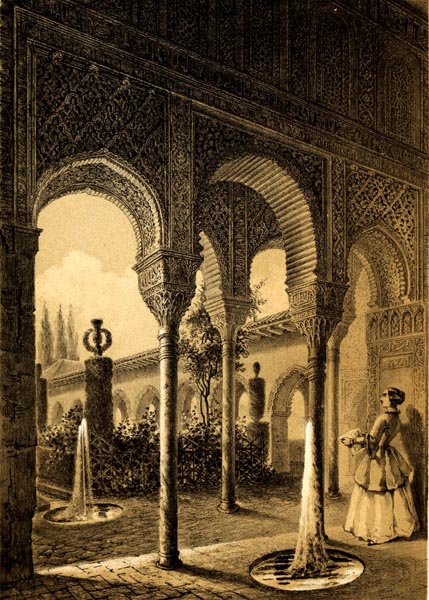

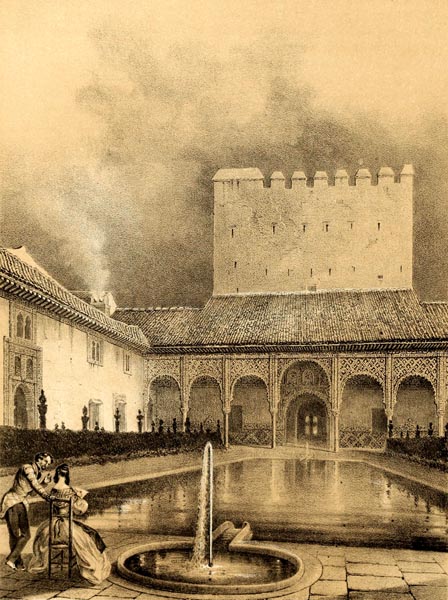

‘Patio de la Alberca (Alhambra)’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p485, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

After a few moments of mute astonishment, the two lovers entered this dwelling of vanished power and past happiness. They first made the round of the Mexuar palace, amid the perfume of flowers and freshness of water. Then they penetrated the Court of the Lions. Aben-Hamet’s emotion increased at every step. ‘If thou didst not fill my soul with delight, he said to Blanca, ‘with what grief I would be obliged to ask thee, thee a Spaniard, the history of these rooms. Ah, this place was created as a sanctuary for happiness, and I...!’

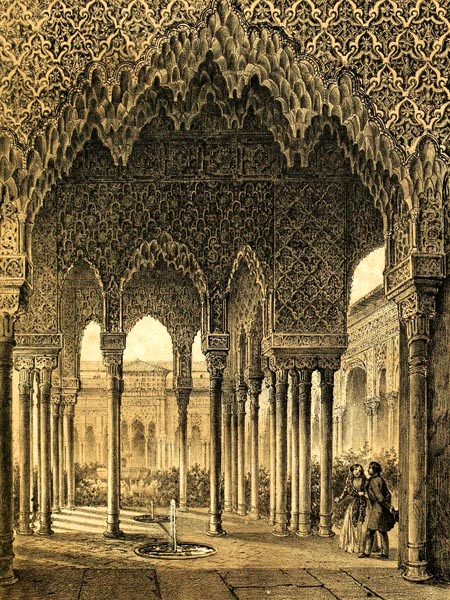

‘Entrada al Patio de Los Leones (Alhambra)’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p502, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

Aben-Hamet recognised the name of Boabdil inscribed in the mosaics. ‘O my king,’ he cried, ‘what has become of thee? Where shall I find thee in thy deserted Alhambra?’ And tears of fidelity, loyalty and honour filled the eyes of the young Moor. ‘Your former masters,’ said Blanca, ‘or rather your ancestral kings, were ungrateful.’ – ‘How should they not be,’ replied the Abencerraje, ‘they were unhappy!’

As he spoke these words, Blanca led him into a room (La Sala de los Abencerrajes) that seemed the very sanctuary of the Temple of Love. Nothing could equal the elegance of this retreat: the whole vault, painted blue and gold, and composed of arabesques carved so as to admit the sun’s rays, let in the light as through a flowery fabric. A fountain gushed in the midst of the edifice, and its waters, falling like dew, were received in a conch of alabaster. ‘Aben-Hamet,’ said the daughter of the Duke of Santa Fé, ‘look closely at this fountain; it received the mutilated heads of the Abencerrajes. You may still see on the marble the bloodstain left by those unfortunates whom Boabdil sacrificed to his suspicions. That is the manner in which they treat men who seduce credulous women in your country.’

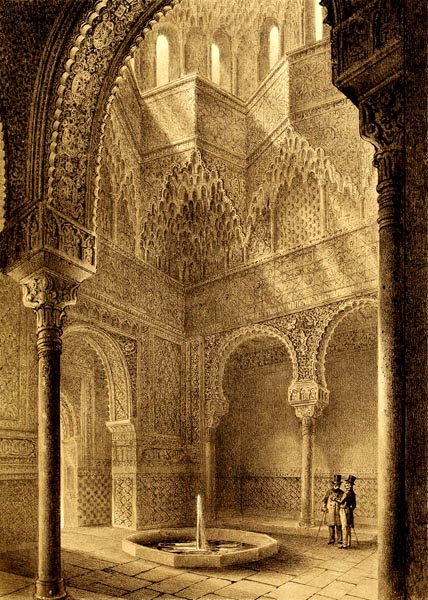

‘Sala de los Abencerrajes (Alhambra)’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p526, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

Aben-Hamet no longer heard Blanca; he prostrated himself and kissed the bloodstain left by his ancestors, with respect. Rising, he exclaimed: ‘O Blanca, I swear by the blood of those knights, to love thee with the constancy, fidelity and ardour of an Abencerraje!’

‘You love me then?’ Blanca replied, clasping her two beautiful hands together, and raising her eyes to heaven. ‘But have you forgotten that you are an Infidel, a Moor, an enemy, and I am a Christian and Spanish?’

‘O Sacred Prophet,’ said Aben-Hamet, bear witness to my oath...!’ Blanca interrupted him: ‘What faith can I place in the oaths of one who persecutes my God? How do you know whether I love you?’ What gives you the assurance to credit me with like language?’

Aben-Hamet replied in consternation: ‘It is true, I am no more than thy servant; thou hast not chosen me as your knight.’

‘Moor,’ said Blanca, ‘forgo such ruses; thou hast seen in my eyes that I love thee; my madness for thee passes all measure; become a Christian, and nothing can stop me from being thine. But if the daughter of the Duke of Santa Fé dare speak to thee plainly, thou mayest judge from that very statement that she knows how to command herself and that an enemy of the Christians can have no right to her.’

Aben-Hamet in a transport of passion, seized Blanca’s hands, and placed them upon his turban and then his heart. ‘Allah is powerful,’ he cried, ‘and Aben-Hamet is happy! O Mohammed! Let this Christian understand your law, and nothing can...’ – ‘Thou blasphemest,’ said Blanca: ‘let us leave this place.’

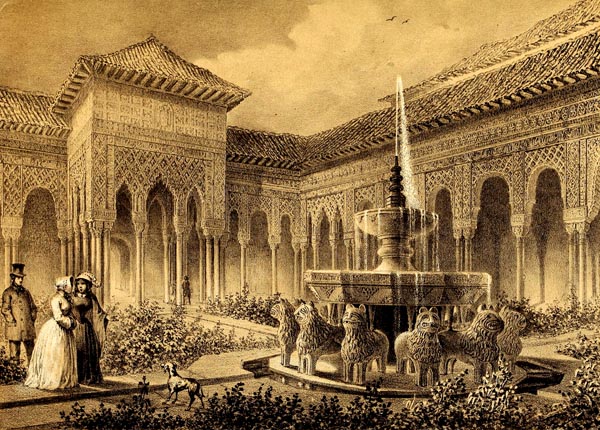

She leant on the arm of the Moor, and approached the Fountain of the Twelve Lions, which gives its name to one of the courts of the Alhambra: ‘Stranger,’ said the innocent Spanish girl, ‘when I look at thy clothes, thy turban, thy weapons, and I think of our love, I think I see the ghost of that handsome Abencerraje, walking in this secluded retreat, with the unfortunate Alfaima. Translate the Arabic inscription for me, engraved on the marble of the fountain.’

‘Plato de Los Leones (Alhambra)’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p516, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

Aben-Hamet read these words (of Ibn Zamrak, secretary to Mohammed V of Granada)

‘…In this garden are there not wonders

God has made peerless in their beauty,

Sculptures of pearl, translucent with light,

Whose borders are edged with seeds of pearl?

…A lover whose eyelids brim with tears’

…the rest of the inscription was barely legible.

‘The inscription was made for thee,’ said Aben-Hamet. Beloved Sultana, these palaces were never as beautiful in their youth as they are now in their ruin. Listen to the sound of the fountains whose foam deflects the water; look at these gardens revealed through half-fallen archways, contemplate the sun setting among these porticoes: how sweet it is to wander with thee through this place! Thy words embalm these retreats, like roses of Yemen. With what charm I recognize in thy language accents of the language of my ancestors! The mere brushing of thy dress against the marble makes me shudder. The air is only fragrant because it has touched thy hair. Thou art beautiful as the Spirit of my homeland, amidst these ruins. But dare Aben-Hamet hope to win thine heart? What is he beside thee? He has traversed the mountains with his father; he knows the plants of the desert...alas there is none to heal the wound that thou hast dealt him! He bears arms, but he is no knight. I was wont to say: “The waters of the sea that sleep safe in the hollows of the rocks are mute and tranquil, while all the great sea is troubled and filled with sound. Aben-Hamet, such shall be thy life, peaceful, silent, unknown in some forgotten corner of the earth, while the Sultan’s court is overwhelmed by storms.” So I spoke, young Christian, yet thou hast proved to me that the storm may also disturb the drop of water in the hollow of the rock.’

Blanca listened with delight to this language new to her, and whose Oriental flavour seemed so well suited to this home of the Fays, she traversed with her lover. Love penetrated her heart on all sides; she felt weak; and was forced to lean more heavily on the arm of her guide. Aben-Hamet supported the sweet burden, and as they walked said: ‘Ah, would I not make a brilliant Abencerraje!’

‘Thou wouldst please me less,’ replied Blanca, ‘because I would be more tormented; remain obscure and live for me. Often a famous knight neglects love for fame.’

‘Thou wouldst not have that danger to fear’ Aben-Hamet replied ardently.

‘And how then wouldst thou love me, if thou wast an Abencerraje?’ said the descendant of Ximena.

‘I would love thee,’ replied the Moor, ‘more than glory and less than honour.’

The sun had set below the horizon, during the two lovers’ walk. They had traversed the whole Alhambra. What memories of the past offered themselves to Aben-Hamet’s musings! Here the Sultana received through openings the vapour of perfumes that burned below. Here, in this secluded sanctuary (Peinador de la Reina) she displayed herself in all the finery of the Orient. And it was Blanca, a woman he adored, who recounted these details to the handsome young man she idolized.

The moon, rising, poured her wavering light over the abandoned retreats, and deserted courts of the Alhambra. Her white rays described, on the turf of the flowerbeds, on the walls of the rooms, the tracery of an aerial architecture, the arches of the cloisters, the moving shadows of the gushing waters, and those of the shrubs swaying in the breeze. A nightingale sang in a cypress-tree which pierced the domes of a ruined mosque, and the echoes repeated its plaint. Aben-Hamet wrote Blanca’s name, by the light of the moon, on the marble of the Hall of the Two Sisters (Sala de Dos Hermanos): he traced the name in Arabic characters, so that the traveller would have one mystery more to divine in this palace of mysteries.

‘Moor, these pastimes are cruel,’ said Blanca, ‘let us leave this place. My life’s destiny is fixed forever. Retain these words deep in thine heart: “While thou art a Muslim, I am thy lover, yet one without hope; if thou wert a Christian, I would gladly be thy wife.”’

Aben-Hamet replied: ‘While thou art a Christian, I am your sad slave, if thou wert a Muslim girl, I would be proud to be thy husband.’

And thus these noble lovers emerged from that palace of danger.

Blanca’s passion grew day by day, and that of Aben-Hamet increased with the same violence. He was so delighted to be loved for himself alone, of owning to no alien reason for the feelings he inspired, that he avoided revealing the secret of his birth to the daughter of the Duke of Santa Fé: he would take delicate pleasure in informing her that he was of an illustrious family, on the very day that she agreed to give him her hand. But he was suddenly recalled to Tunis: his mother, seized by an incurable disease, wished to embrace her son and grant him her blessing before abandoning life. Aben-Hamet presented himself at Blanca’s palace. ‘Sultana,’ ‘he said, ‘my mother is dying. She has asked for me to close her eyes. Wilt thou preserve thy love for me?’

‘Thou art forsaking me,’ said Blanca growing pale. ‘Shall I ever see thee again?’

‘Come,’ said Aben-Hamet. ‘I require an oath of thee, and one that death alone can break. Follow me.’

They walked together; they arrived at a cemetery which was once that of the Moors. Here and there, could still be seen small funeral columns on which the sculptor had once carved a turban; but the Christians had since replaced the turbans with crosses. Aben-Hamet led Blanca to the foot of one of these columns.

‘Blanca,’ he said, ‘my ancestors lie here; I swear by their ashes to love thee until the day on which the Angel of Judgement calls me to the tribunal of Allah. I promise thee never to commit my heart to another woman, and to take thee as my wife as soon as thou knowest the Prophet’s holy light. Each year, at this time, I will return to Granada to see if thou hast kept faith with me, and whether thou wishest to renounce thy errors.’

‘And I,’ said Blanca, in tears, ‘I will wait for all time; I will keep till my last breath the vow that I have sworn to thee, and I will receive thee as my husband when the Christian God, more powerful than thy lover, has touched thy infidel heart.’

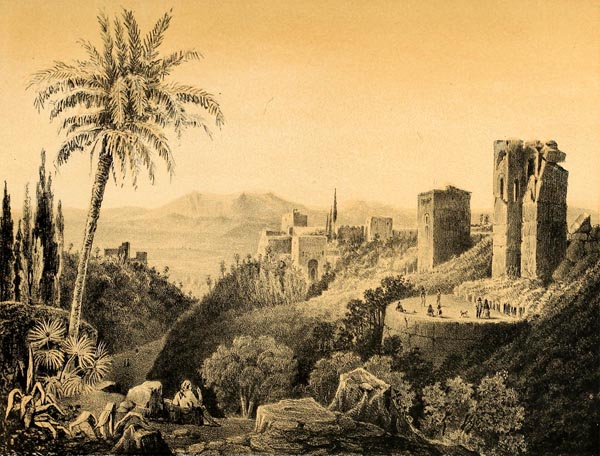

‘Recuerdos del Generalife’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p568, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

Aben-Hamet departed; the wind carried him to African shores: his mother had just then expired. He cried; he embraced her coffin. The months passed: now wandering among the ruins of Carthage, now sitting beside the tomb of St. Louis, the exiled Abencerraje summoned up the day that would lead him to Granada once more. The day dawned at last: Aben-Hamet embarked, and his prow turned towards Malaga. With what transports, what joy mingled with fear, he saw the promontories of Spain appear! Did Blanca await him on these shores? Did she still remember the poor Arab, who had never ceased to love her beneath the desert palms?

The daughter of the Duke of Santa Fé was not unfaithful to her vow. She asked her father to take her to Malaga. From the mountains fringing the uninhabited coast, her eyes followed the distant ships and fugitive sails. During a storm, she watched with horror the seas raised by the winds: then she loved to lose herself in the clouds, to expose herself to the dangers of the passage, to feel herself bathed by the same waves, driven on by the same whirlwind that threatened Aben-Hamet’s life. When she saw the plaintive gull skim the waves with his great curved wings, and fly towards the shores of Africa, she charged it with all those words of love, all those senseless wishes that emerge from a heart consumed by passion.

‘Màlaga’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p383, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

One day, as she wandered on the shore, she caught sight of a long vessel with an elevated prow, the sloping mast and lateen sail proclaiming the elegant genius of the Moors. Blanca ran to the harbour, and was soon gazing as the Barbary ship entered port, making the waves foam with the rapidity of its course. A Moor, handsomely dressed, stood on the bow. Behind him two black slaves held an Arabian horse by the bridle, its smoking nostrils and streaming mane revealing both its natural ardour, and the fear that the waves inspired. The boat arrived, lowered its sails, and docked at the pier, presenting its flank: the Moor leapt to the shore which resounded to the clatter of his weapons. The slaves allowed the dappled horse to leap down like a leopard, the steed neighing and rearing with joy at regaining land. Other slaves gently lowered a basket in which a gazelle was resting among palm leaves. Her slender legs were tied and bent beneath her, lest they be broken by the motion of the vessel: she wore a necklace of aloe seeds, and on a gold plaque that served to link the two ends of the necklace, were engraved, in Arabic, a name and a talismanic charm.

Blanca recognized Aben-Hamet: she dared not betray herself to the eyes of the crowd; she withdrew and sent Dorothea, one of her ladies, to tell the Abencerraje that she would wait for him at the palace of the Moors. Aben-Hamet was at that moment presenting to the governor his firman (credentials) written in azure letters on a rich vellum and enclosed in a silken sheathe. Dorothea approached and led the happy Abencerraje to Blanca’s feet. What delight, on each finding that the other had remained faithful! What happiness to meet again after being separated for so long! What endless fresh vows of eternal love!

The two black slaves led the Numidian horse, who, instead of a saddle, had a lion-skin on his back, attached by a purple strap. Then they brought forward the gazelle. ‘Sultana,’ said Aben-Hamet, ‘this is a deer from my country, almost as light-footed as thou.’ Blanca freed the delightful creature herself, which seemed to thank her, with the gentlest of glances. During the absence of the Abencerraje, the daughter of the Duke of Santa Fé had studied Arabic: she read with tender gaze her own name on the collar of the gazelle. The latter, restored to liberty, could hardly stand; its feet had been bound for so long; it lay down on the ground, and leaned its head on its mistress’s lap. Blanca offered it fresh dates, and stroked this offspring of the desert, whose soft skin retained the perfumes of aloe wood and the roses of Tunis.

The Abencerraje, the Duke of Santa Fé, and his daughter, left together for Granada. The happy couple spent their days as they had the previous year: the same walks, the same regrets at the sight of his homeland, the same love, or rather an ever-increasing love, endlessly shared; but also the same attachment by the two lovers to the religions of their fathers. ‘Become a Christian,’ said Blanca. ‘Become a Muslim,’ replied Aben-Hamet, and they separated again without succumbing to the passion that drew them to one another.

‘Torre de los Picos (Alhambra)’

Recuerdos y Bellezas de España : Bajo la Real Proteccion de ... la Reina y el Rey - Francisco Pí y Margall, Francisco Javier Parcerisa (p554, 1850)

Internet Archive Book Images

Aben-Hamet reappeared for a third year, like one of those birds of passage that love brings back to us when it is spring in our climate. He found no Blanca on the shore, but a letter from his beloved informed the faithful Arab of the departure of the Duke of Santa Fé for Madrid, and the arrival of Don Carlos in Granada. Don Carlos was accompanied by a French prisoner, a friend of Blanca’s brother. The Moor felt his heart sink on reading this letter. He sailed from Malaga to Granada, with the gloomiest of forebodings. The mountains seemed dreadful in their solitude, and he often turned his head to gaze at the sea he had just traversed.

Blanca, during her father’s absence, could not leave the brother she loved, a brother who wished to relinquish all his wealth in her favour, and whom she saw again after an absence of seven years. Don Carlos possessed all the courage and pride of his nation: fierce as the conquerors of the New World, alongside whom he had first fought; religious as the Spanish knights who had conquered the Moors; he nourished in his heart that hatred against the infidels which he had inherited from El Cid.

Thomas de Lautrec, of the illustrious house of Foix, in which the beauty of their women and the valour of their men seemed a hereditary gift, was the younger brother of the Countess of Foix, and of the brave and unfortunate Odet de Foix, Lord of Lautrec. At the age of eighteen years, Thomas had been knighted by Bayard, during the retreat which cost the life of that knight ‘sans peur et sans reproche’ (without fear and without reproach). Some time later, Thomas was badly wounded and taken prisoner at Pavia (1525), while defending the King, who fighting as a knight lost all there save honour.

Don Carlos of Bivar, who witnessed Lautrec’s bravery, had cared for the young Frenchman’s wounds, and between them one of those heroic friendships was quickly established, to which esteem and virtue form the foundation. Francis I had been returned to France, but Charles V retained the other prisoners. Lautrec had the honour to share his king’s captivity, and to sleep at his feet in prison. Remaining in Spain after the departure of the monarch, he had been placed on parole by Don Carlos, whom he had recently accompanied to Granada.

When Aben-Hamet presented himself at the palace of Don Rodrigo, and was introduced into the room containing the daughter of the Duke of Santa Fé, he felt torments hitherto unknown to him. At Dona Blanca’s feet sat a young man who was gazing at her in silence, in a sort of rapture. This young man wore knee-breeches of buffalo hide, and a doublet of the same colour, fastened by a belt from which his sword hung in a sheath decorated with fleur-de-lis. A silk mantle was thrown over his shoulders, and his head was covered by a narrow-brimmed hat, adorned with plumes: a lace ruff, falling over his chest, left his neck exposed. A moustache, black as ebony, gave his naturally gentle face a manly and warrior-like aspect. Large boots, whose folds fell towards his feet, bore gold spurs, a mark of chivalry.

At some distance, another knight stood leaning on the iron cross-guard of his sword: dressed as was the former knight, but apparently much older. His austere air, though ardent and passionate, inspired respect and fear. The red cross of Calatrava was embroidered on his doublet, with this motto: ‘For her and for my king.’

An involuntary cry escaped Blanca when she saw Aben-Hamet. ‘Knights,’ she said immediately, ‘this is the infidel of whom I have spoken so extensively, be fearful lest he erases your victory. The Abencerrajes were made as he is, and no one surpassed them in loyalty, courage and gallantry.’

Don Carlos faced Aben-Hamet. ‘Sir Moor,’ said he, ‘my father and my sister informed me of your name; you are considered of noble race and brave; you yourself are distinguished by your courtesy. Charles V, my master, must shortly wage war against Tunis, and I trust we will see you take the field.’

Aben-Hamet put his hand to his breast, seated himself on the ground without answering, and fixed his gaze on Blanca and Lautrec. The latter, with the curiosity of his countrymen, admired the superb robe, brilliant weapons, and handsome visage of the Moor; Blanca seemed in no way embarrassed; her whole soul was in her eyes: the sincere Spanish girl made no attempt to hide the secret of her heart. After a few moments of silence, Aben-Hamet rose, bowed to the daughter of Don Rodrigo, and withdrew. Surprised by the Moor’s manner and Blanca’s gaze, Lautrec left with a suspicion which was soon converted to a certainty.

Don Carlos remained alone with his sister. ‘Blanca,’ he said, ‘explain yourself. From whence does this disturbance arise that the sight of this stranger causes you?’

‘My brother,’ Blanca replied, ‘I love Aben-Hamet, and if he desires to become a Christian, my hand is his.’

‘What!’ cried Don Carlos: ‘You are in love with Aben-Hamet! A daughter of the Bivars loves a Moor; an Infidel; an enemy we have driven from this palace!’

‘Don Carlos,’ Blanca replied, ‘I love Aben-Hamet; Aben-Hamet loves me; for three years he has renounced my company rather than renounce the religion of his fathers. Nobility, honour, chivalry, are his; I will worship him till my last breath.’

Don Carlos was capable of appreciating the generosity of Aben-Hamet’s resolution, though he deplored that Infidel’s blindness. ‘Wretched Blanca,’ he said, ‘where will this love lead thee? I had hopes that Lautrec, my friend, would become my brother.’

‘You were wrong,’ said Blanca: ‘I cannot love that stranger. As for my feelings for Aben-Hamet, I do not have to account to anyone for them. Keep thy vows of knighthood as I will keep my vows of love. Know only, as a solace to thee, that Blanca will never be the wife of an Infidel.’

Our family will vanish from the earth.’ cried Don Carlos.

‘It is for thou to revive it,’ said Blanca. ‘Besides what use are descendants thou wilt never see, and who will lapse from thy virtue? Don Carlos, I feel that we are the last of our race; we are too far out of the common order for our race to flourish after us: the Cid was our ancestor, he will be our posterity.’ Blanca left.

Don Carlos flew to the Abencerraje. ‘Moor,’ he said, ‘renounce my sister or accept my challenge.’

‘Wert thou charged with this message by thy sister,’ replied Aben-Hamet, ‘to ask me to revoke the vows she made me?’

‘No,’ replied Don Carlos, she loves thee more than ever.’

‘Ah: a brother worthy of Blanca!’ cried Aben-Hamet, interrupting him, ‘I owe all my good fortune to thy race! ‘O happy Aben-Hamet! O blessed hour! I thought Blanca disloyal to me out of regard for this French knight...’

‘And in that lies thy misfortune,’ said Don Carlos, in turn, beside himself: ‘Lautrec is my friend; without thee he would be my brother. Render me satisfaction for the tears thou forcest my family to shed.’

‘Indeed, I am willing,’ replied Aben-Hamet, ‘but though born of a race that may have fought thine, I am not yet a knight. I see none here that might confer upon me the order that would enablest thee to measure thyself against me without betraying thy rank.’

Don Carlos, being struck with this reflection of the Moor’s, gazed at him with a mixture of admiration and fury. Then suddenly, he said: ‘I myself will grant thee knighthood. Thou art worthy.’

Aben-Hamet knelt before Don Carlos, who gave him the accolade, striking him three times on the shoulder with the flat of his sword; then Don Carlos girded him with the very sword that the Abencerraje might well be about to plunge into his chest: such was the former idea of chivalry.

Both rushed to their horses, left the walls of Granada behind, and flew to the Fountain of the Pine. The duels of the Moors and Christians had long made this fountain famous. It was there that Malik-Alabez fought against Ponce de Léon, and that the Grand Master of Calatrava slew the valiant Albayaldos. The remnants of the Moorish knight’s weapons could still be seen hanging from the branches of the pine-tree, and carved on the bark of the tree could be seen a few letters of a funeral inscription. Don Carlos pointed out the tomb of the Albayaldos to the Abencerraje: ‘Imitate,’ he cried, ‘that brave Infidel; and receive baptism and death at my hand.’

‘Death, it may be,’ said Aben-Hamet, ‘but long live Allah and the Prophet!’

They immediately took the field, and rushed furiously at one another. They had only their swords: Aben-Hamet was less skilful in battle then Don Carlos, but the superiority of his blade, tempered at Damascus, and the agility of his Arabian steed, still gave him the advantage over his enemy. He urged his courser forward as the Moors do, and with his large and sharp-edged stirrup slashed the right leg of Don Carlos’s horse below the knee. The wounded horse fell, and Don Carlos, dismounted by the chance blow, made at Aben-Hamet with sword raised. Aben-Hamet leapt to the ground and received Don Carlos fearlessly. He parried the initial blows from the Spaniard, who broke his sword on the Damascene blade. Twice betrayed by fortune, Don Carlos shed tears of rage, and shouted to his enemy: ‘Strike, Moor, strike; Don Carlos disarmed defies thee: thou and the whole of thine infidel race.’

‘Thou wert free to kill me,’ replied the Abencerraje, ‘but I have never thought to do thee the least injury: I wished only to prove to thee that I was worthy of being thy brother, and to prevent thee from despising me.’

At this moment a cloud of dust was visible: Lautrec and Blanca galloping on two mares from Fez, lighter than the wind. They arrived at the Fountain of the Pine and saw that the combat had ceased.

‘I am vanquished,’ said Don Carlos, ‘this knight has granted me my life. Lautrec, perhaps you may be more successful than I.’

‘My wounds, said Lautrec in a noble and gracious voice, ‘permit me to refuse combat with this courteous knight. I prefer,’ he added, blushing, ‘not to know the subject of your quarrel, or penetrate a secret that would perhaps bring death to my heart. Soon my absence will restore peace among you, unless Blanca orders me to remain at her feet.’

‘Knight,’ said Blanca, ‘you shall stay beside my brother; you shall regard me as a sister. All the hearts that are here are experiencing pain; you will learn from us how to endure life’s ills.’

Blanca would have wished the three knights to clasp hands; all three refused to do so: ‘I loathe Aben-Hamet!’ cried Don Carlos. – ‘I envy him,’ said Lautrec. – ‘And I,’ said the Abencerraje, ‘I esteem Don Carlos, and I pity Lautrec, but I cannot love them.’

‘Let us be endlessly patient,’ said Blanca, ‘and sooner or later friendship will succeed esteem. Let the fatal event that brought us here be forever unknown to Granada.’

From that moment, Aben-Hamet was a thousand times dearer to the daughter of the Duke of Santa Fé: love adores valour; he lacked nothing of the virtues of the Abencerrajes, since he was brave, and Don Carlos owed him his life. Aben-Hamet, on Blanca’s advice, abstained for a few days from appearing at the palace, to allow Don Carlos’s anger to abate. A mixture of sweet and bitter feelings filled the Abencerraje’s soul: if on the one hand the assurance of being loved with such fidelity and zeal was to him an inexhaustible source of delight, on the other the certainty of never attaining happiness unless he renounced the religion of his fathers, quelled Aben-Hamet’s courage. Several years had passed without bringing a remedy for his ills; was he to see the rest of his life pass in this way?

He was lost in the depths of the most serious and most tender reflection one evening, when he heard the sound of that Christian prayer that announces the end of day. It came to his mind to enter the temple of Blanca’s God, and seek advice from the Lord of Creation.

He soon came to the door of an ancient mosque converted into a church by the faithful. His heart seized by sorrow and religion, he penetrated the temple that was once that of his God and his homeland. The prayer had just ended: there was no one in the church. A sacred gloom reigned throughout the host of pillars which resembled the serried ranks of trees planted in some forest. The airy architecture of the Arabs was married to the Gothic, and without losing its elegance had acquired the gravity appropriate to meditation. A few lamps barely lit the recesses of the vaults; but by the light of several burning candles, the altar within the sanctuary still shone: it glittered with gold and jewels. The Spaniards consider it glorious to despoil themselves of their wealth in order to adorn the objects of their worship; and the image of the living God set amidst veils of lace, crowns of pearls and sprays of rubies, is worshipped by a half naked people.

No seats were to be seen in the midst of the vast enclosure: a marble pavement that covered the tombs, served for both great and small to prostrate themselves before the Lord. Aben-Hamet advanced slowly through the deserted aisles which echoed to the solitary sound of his footsteps. His spirit was torn between the memories that this ancient edifice, once dedicated to the religion of the Moors, traced in his mind, and the feelings that the Christian religion gave birth to in his heart. He saw, at the foot of a column, a motionless figure, which he at first took for a statue over a tomb. He approached; he saw that it was a young knight, kneeling, his head bowed in respect and his arms folded across his chest. The knight did not move at the sound of Aben-Hamet’s footsteps; no distraction, no outward sign of life could disturb his profound state of prayer. His sword lay on the ground before him, and his hat, decked with plumes, was placed on the marble at his side: he seemed as if fixed in that attitude by the agency of some enchantment. It was Lautrec: ‘Ah,’ said the Abencerraje to himself, ‘this young and handsome Frenchman asks some signal favour of the heavens; this warrior, already celebrated for his courage, pours out his heart before the Lord of Heaven, like the humblest and most obscure of men. Let me also pray thus to the God of knighthood and glory.’

Aben-Hamet was about to throw himself headlong onto the marble floor, when he saw, in the lamplight, an Arabic verse from the Koran, which appeared beneath the half-ruined plaster of the wall. Remorse awoke in his heart, and he hastened to leave the building where he had considered renouncing his loyalty to his religion and country.

The cemetery which surrounded the ancient mosque was a species of garden planted with orange-trees, cypress and palm-trees, and watered by two fountains; a cloister enclosed it. Aben-Hamet, passing beneath one of it colonnades, saw a woman about to enter the church. Though she was enveloped by a veil, the Abencerraje recognised the daughter of the Duke of Santa Fé; he stopped her, saying: ‘Dost thou seek Lautrec in this temple?’

‘Forsake these common jealousies,’ Blanca replied; ‘if I no longer loved thee, I would tell thee; I would scorn to deceive thee. I come here to pray for thee, thou alone art now the object of my prayers: I neglect my soul for thine. Thou should’st not have intoxicated me with the poison of thy love, or thou should’st have consented to serve the God I serve. Thou troublest all my family; my brother hates thee, my father is overwhelmed with sorrow, because I refuse to choose a husband. Dost thou not see that my health is suffering? Look on this sanctuary of death; it is enchanted! I will soon be at rest here, if thou dost not hasten to adopt my faith before the Christian altar. The struggles I undergo are slowly undermining my existence; the passion that thou inspirest in me will not support my frail existence forever: consider, O Moor, to speak to thee in thine own language, that the fire which lights the torch is also the fire that consumes it.’

Blanca entered the church, leaving Aben-Hamet overwhelmed by these last words.

It was done: the Abencerraje was vanquished; he would renounce the error of his religion; he had struggled long enough. The fear of seeing Blanca’s death outweighed all other feelings in the heart of Aben-Hamet. After all, he told himself, the God of Christians may well be the true God. That God is still a God of noble souls, since he is worshipped by Blanca, Don Carlos and Lautrec.

Reflecting thus, Aben-Hamet waited impatiently for the following day to make his resolution known to Blanca, and change a life of sadness and tears for a life of joy and happiness. He could not go to the palace of the Duke of Santa Fé until the evening. He learned that Blanca had gone with her brother to the Generalife, where Lautrec was holding a celebration. Aben-Hamet, stirred by fresh suspicions, flew in Blanca’s footsteps. Lautrec blushed on seeing the Abencerraje appear; as for Don Carlos, he received the Moor with cold politeness, behind which esteem was nonetheless evident.

Lautrec had arranged for the finest fruits of Spain and Africa to be served in a room of the Generalife, called the Hall of Kings (Sala de los Reyes). All around this room were hung portraits of the princes and knights who had conquered the Moors; there were Pelayo, El Cid, and Gonzalo Fernandez de Cordoba. The sword of the last king of Granada hung beneath the portraits. Aben-Hamet swallowed his pain, and merely said, like the lion in La Fontaine (Fables III, 10), as he gazed at these paintings: ‘We have no talent for portraiture.’

The generous Lautrec, who saw the eyes of Abencerrajes turn despite himself to gaze at Boabdil’s sword, said: ‘Sir Moor, had I anticipated that you would do me the honour to attend my celebration, I would not have received you here. Every day a sword is lost, and I have seen the most valiant of kings surrender his to his fortunate enemy.’

‘Ah,’ cried the Moor, covering his face with a fold of his robe, ‘it is one thing to lose one’s sword as Francis I did; another to do so like Boabdil...!’

Night fell; torches were brought; the conversation changed direction. Don Carlos was asked to tell of the conquest of Mexico. He spoke of that previously unknown world with the proud eloquence natural to the Spanish nation. He told of the misfortunes of Montezuma, the way of life of the Native Americans, the prodigies of Castilian valour, and even the cruelties of his countrymen, which seemed to him to deserve neither blame nor praise. These tales enchanted Aben-Hamet, whose passion for the story betrayed his Arab blood. He in turn described the Ottoman Empire, newly established in the ruins of Constantinople, not without expressing regret for the days of the first Mohammedan empire; that happy era when the Commander of the Faithful (Harun al-Raschid) saw glittering around him Zobeide (his wife); his favourite slave-girls, the Flower of Beauty, the Nourisher of Hearts, and the Tormentor; and the generous Ganem (the son of Abou Ayoub), called the Slave of Love. As for Lautrec, he described the gallant Court of Francis I: the rebirth of the arts from the barbaric womb; honour; loyalty; the chivalry of former times united to the manners of civilised centuries; Gothic turrets embellished according to Greek architectural orders; and Gallic ladies enhancing the richness of their ornaments with Athenian elegance.

After these speeches, Lautrec, who wanted to amuse the goddess of that gathering, took up a guitar, and sang the ballad he had composed to a tune from the mountains of his country:

‘How sweet is the remembrance

Of my birthplace that enchants!

My sister, how joyful were those days

In France!

O my land, let that love exist, heart says,

Always!

Dost thou remember how our mother,

At the entrance to our home there,

Pressed us to her heart, so joyfully

My dear;

And we kissed her white hair gently,

You and me.

My sister, doth memory yet restore

The chateau bathed by the waters of the Dore,

And that old ancient tower,

Of the Moors,

Where the trumpet sounded, to your bower,

The dawn hour.

Dost thou recall that tranquil lake

Where the agile swallows deftly take

The breeze that sets the bending reed

To shake,

Till the sun’s rays, on the water, recede

Sweet indeed?

Oh! Who’ll bring back my Helen, to me;

Those mountains; and our old oak-tree?

The memory of them all fills my days

With misery:

My land, may you be my love, heart says,

Always!’

Lautrec, as he ended the last verse, with his glove wiped away a tear, prompted by his memories of the noble land of France. The handsome captive’s regrets were felt as deeply by Aben-Hamet, who deplored like Lautrec the loss of his homeland. Asked, in turn, to play the guitar, he excused himself, saying he only knew a ballad which would scarcely please the Christians.

‘If it concerns the Infidels, who bemoan our victories,’ Don Carlos retorted scornfully, ‘you may sing; the vanquished are allowed their tears.’

‘Yes,’ said Blanca, ‘and that is why our ancestors, once subjected to the yoke of the Moors, have left so many plaints.’

So Aben-Hamet sang his ballad, which he had been taught by a poet of the tribe of the Abencerrajes:

‘Don Juan the King

One day out riding

Saw beneath the Sierra

Spanish Granada;

Said he: ‘As I stand,

City so lovely,

My heart I give thee,

With my hand.

I’ll marry thee,

I’ll give to thee,

To serve your will,

Cordoba, Seville.

Sweet attire, my dove,

And pearls so fine

If thou art mine

Shall mark our love.

Granada answered him:

Oh, Leon’s great King

To the Moor, instead,

I’m already wed.

Your gifts leave un-given:

I yet have here,

Rich, lovely gear

And sweet children.

So thou may’st say;

Yet thou errest, today;

O mortal injury!

Granada’s perjury!

An accursed Christian,

Of the Abencerraje

Will have the heritage:

So it is written!

The camels shall never

Bring Hadjis from Medina,

To the fountain, and room

By the pool, to the tomb.

An accursed Christian,

Of the Abencerraje

Will have the heritage:

So it is written!

O lovely Alhambra!

O Palace of Allah!

City of Fountains!

River of green plains!

An accursed Christian,

Of the Abencerraje

Will have the heritage:

So it is written!’

The simplicity of this plaint even moved the proud Don Carlos, despite the imprecations against Christians. He had indeed wished to be granted the dispensation to sing; but as a courtesy to Lautrec had thought he ought to yield to that prior request. Aben-Hamet now gave the guitar to Blanca’s brother, who celebrated the exploits of his illustrious ancestor El Cid:

‘Set to leave for the shores of Africa,

The Cid, all armed, brilliant in valour,

On his guitar, at the feet of Ximena,

Sang these verses dictated by honour:

Ximena had said, ‘Go fight the Moor;

In this, above all, return as the victor.

I’ll believe Rodrigo must truly adore

One he leaves for the love of honour.

Give me my helmet, give me my spear!

I wish to show that Rodrigo’s the braver:

In this battle, to show he’s no fear,

His cry will be: his lady and honour.

Moors praised for thy gallantry,

My noble song, over thine the victor,

The rage of Spain, some day, shall be,

Since it sings of true love with honour.

In the valleys of our Andalusia,

Christians there will sing of my valour:

He preferred, his God, his king, his Ximena,

To life itself, and above all: his honour.’

Don Carlos seemed so proud, singing these lyrics in a sonorous masculine voice, that he might have been taken for the Cid himself. Lautrec shared his friend’s warlike enthusiasm; but the Abencerraje grew pale at the name of El Cid.

‘That knight,’ he said, ‘whom Christians call the Flower of Battles, has a name among us for his cruelty. If only his mercy had matched his valour...!’

‘His mercy,’ Don Carlos replied, interrupting Aben-Hamet vigorously, ‘surpassed even his courage, and no Moor shall slander the hero to whom my family owes its existence.’

‘What is this, thou sayest?’ cried Aben-Hamet, leaping from the seat where he was reclining: ‘thou countest the Cid amongst thy ancestors?’

‘His blood flows in my veins,’ replied Don Carlos, ‘and I recognise that noble blood by the hatred that burns in my heart for the enemies of my God.’

‘So,’ said Aben-Hamet, gazing at Blanca, ‘thou art of that same House of Bivar that following the conquest of Granada invaded the homes of the unfortunate Abencerrajes and dealt death to an old knight of that name who sought to defend the tomb of his ancestors!’

‘Moor!’ cried Don Carlos, inflamed with anger, ‘Know that I will allow no further questioning. If I today possess the spoils of the Abencerrajes, my ancestors gained them at the cost of their blood, and owe them simply to their prowess with the blade.’

‘One word, yet.’ said Aben-Hamet increasingly troubled: ‘Exiled as we are, we were ignorant of the fact that the Bivars bear the title of Santa Fé: that is what has led to my error.’

‘It was,’ replied Don Carlos, ‘upon that same Bivar, the conqueror of the Abencerrajes, that the title was conferred by Ferdinand II of Aragon, called the Catholic.’

Aben-Hamet’s head bent on his breast: he stood silent between Don Carlos, Lautrec and the astonished Blanca. Two streams of tears fell from his eyes onto the knife attached to his waist. ‘Forgive me,’ he said; ‘men, I know, should not shed tears: from this moment mine will flow no more, though much remains to weep over: listen to me, Blanca, for my love for thee burns like the hot winds of Arabia. I was vanquished; I could no longer live without thee. Yesterday, the sight of this French knight at prayer, thy words in the cemetery of the temple, made me resolve to know thy God, and sacrifice my faith for thee.’

A movement of joy from Blanca, and surprise from Don Carlos, interrupted Aben-Hamet; Lautrec hid his face in his hands. The Moor divined his thoughts, and shook his head with a heartbreaking smile: ‘Knight,’ he said, ‘do not lose all hope; and thou, Blanca, weep forever for the last of the Abencerrajes!’

Blanca, Don Carlos, Lautrec, all three raised their hands to heaven, and exclaimed: ‘The last of the Abencerrajes!’

Silence reigned; fear, hope, hate, love, astonishment, jealousy, stirred their hearts; Blanca soon fell to her knees. ‘God of Kindness,’ she said, ‘Thou justifiest my choice! I could only love a descendant of heroes.’