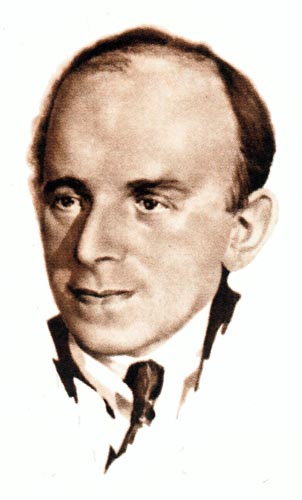

Osip Mandelshtam

Twenty-four Poems

‘Osip Mandelstam 1891-1938’

Post of the USSR, designer Yu. Artsimenev / Почта СССР, художник Ю. Арцименев

Wikimedia Commons

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- ‘Only to read childrens’ books’

- ‘On the pale-blue enamel’

- ‘What shall I do with this body they gave me,’

- ‘A speechless sadness’

- ‘There is no need for words’

- Silentium..

- The Shell

- ‘Orioles are in the woods, and in tonic verse’

- ‘Nature –is Rome, and mirrored there.’

- ‘Insomnia. Homer. Taut canvas.’

- ‘Herds of horses whinny and graze’

- ‘In transparent Petropolis we will leave only bone’

- ‘From a Fearful height, a wandering light’

- ‘Brothers, let us glorify freedom’s twilight’ –

- The Age.

- ‘This night is irredeemable.’

- Tristia.

- ‘Sisters – Heaviness and Tenderness – you look the same’

- ‘I don’t remember the word I wished to say.’

- ‘For joy’s sake, from my hands,’

- ‘The ranks of human heads dwindle: they’re far away.’

- ‘Your thin shoulders whips will redden’

- ‘This is what I most want’

- ‘A flame is in my blood’

- Index by First Line.

‘Only to read childrens’ books’

Only to read childrens’ books,

only to love childish things,

throwing away adult things,

rising from saddest looks.

I am wearied to death with life.

There’s nothing it has that I want,

but I celebrate my naked earth,

there’s no other world to descant.

A plain swing of wood;

the dark, of the high fir-tree,

in the far-off garden, swinging;

remembered by feverish blood.

‘On the pale-blue enamel’

On the pale-blue enamel,

that April can bring,

birch branches’ imperceptible

sway, slipped towards evening.

A network of finely etched lines,

is the pattern’s finished state,

the carefully-made design,

like that on a porcelain plate,

the thoughtful artist set,

on the glazed firmament,

oblivious to sad death,

knowing ephemeral strength.

‘What shall I do with this body they gave me,’

What shall I do with this body they gave me,

so much my own, so intimate with me?

For being alive, for the joy of calm breath,

tell me, who should I bless?

I am the flower, and the gardener as well,

and am not solitary, in earth’s cell.

My living warmth, exhaled, you can see,

on the clear glass of eternity.

A pattern set down,

until now, unknown.

Breath evaporates without trace,

but form no one can deface.

‘A speechless sadness’

A speechless sadness

opened two huge eyes.

A vase of flowers woke:

splashing crystal surprise.

The whole room filled,

with languor - sweet potion!

Such a tiny kingdom

to swallow sleep’s ocean.

Wine’s slight redness,

May’s slight sunlight –

fingers, slender, and white,

breaking wafer-fragments.

‘There is no need for words’

There is no need for words:

nothing must be heard.

How sad, and fine,

an animal’s dark mind.

Nothing it must make heard:

it has no use for words,

a young dolphin, plunging, steep,

along the world’s grey deep.

Silentium

She has not yet been born:

she is music and word,

and therefore the un-torn,

fabric of what is stirred.

Silent the ocean breathes.

Madly day’s glitter roams.

Spray of pale lilac foams,

in a bowl of grey-blue leaves.

May my lips rehearse

the primordial silence,

like a note of crystal clearness,

sounding, pure from birth!

Stay as foam Aphrodite – Art –

and return, Word, where music begins:

and, fused with life’s origins,

be ashamed heart, of heart!

The Shell

Night, maybe you don’t need

me. From the world’s reach,

a shell without a pearl’s seed,

I’m thrown on your beach.

You move indifferent seas,

and always sing,

but you will still be pleased,

with this superfluous thing.

You lie nearby on the shore,

wrapped in your chasuble,

and the great bell of the waves’ roar,

you will fasten to the shell.

Your murmuring foam will kiss

the walls of the fragile shell,

with wind and rain and mist,

like a heart where nothing dwells.

‘Orioles are in the woods, and in tonic verse’

Orioles are in the woods, and in tonic verse

the length of vowels is the only measure.

Once in each year nature’s drawn to excess,

and overflows, like Homer’s metre.

Today yawns, like the caesura’s suspense:

From dawn there’s quiet, and laborious timelessness:

oxen at pasture, and golden indolence;

from the reed, to draw a whole note’s richness.

Note: The metre of Homeric poetry is quantitative, based on vowel length (Mandelstam calls this ‘tonic’). The caesura is a pause or break in the line.

‘Nature –is Rome, and mirrored there.’

Nature - is Rome, and mirrored there.

We see its grandeur, civic forms parade:

a sky-blue circus in the clear air,

fields a forum, trees a colonnade.

Nature - is Rome, therefore,

it seems vain now for prayers to be made:

there are sacrificial entrails, to foretell war;

slaves, to keep silent; stones, to be laid!

‘Insomnia. Homer. Taut canvas.’

Insomnia. Homer. Taut canvas.

Half the catalogue of ships is mine:

that flight of cranes, long stretched-out line,

that once rose, out of Hellas.

To an alien land, like a phalanx of cranes –

Foam of the gods on the heads of kings –

Where do you sail? What would the things

of Troy, be to you, Achaeans, without Helen?

The sea, or Homer – all moves by love’s glow.

Which should I hear? Now Homer is silent,

and the Black Sea thundering its oratory, turbulent,

and, surging, roars against my pillow.

Note: The catalogue of ships appears in Homer’s Iliad Book II (equivalent to counting sheep for the insomniac!) Hellas is Greece, and the Achaeans are the Greeks journeying to the Trojan War. Homer compares the clans to the flocks of geese, cranes, or long-necked swans that gather by the River Cayster in Asia Minor. Troy is near the entrance to the Hellespont, the gateway to the Black Sea. The abduction of Helen was the cause of the War: Paris’s love for her the root of the conflict.

‘Herds of horses whinny and graze’

Herds of horses whinny and graze.

This valley turns, like Rome, to rust.

Time’s clear torrents wash away

a Classic Spring’s dry gilded dust.

In Autumn’s solitary decline,

treading on oak leaves, my path goes,

remembering Caesar’s pure outline,

feminine features, treacherous curved nose.

Capitol and Forum, far-off: Nature’s fall.

Here on the world’s edge I hear

Augustus’s Age, its orblike ball

rolling, majestically, an earthly sphere.

When I am old, let my sadness shine.

Rome bore me: she returns.

Autumn, my she-wolf, kind:

over me, August – month of the Caesars – burned.

Note: Mandelstam identifies with the exiled Ovid on his Black Sea shore, sent there for ‘a poem and a mistake’ (carmen et error), by Augustus. In his essay ‘Word and Culture’ he said ‘Yesterday has not been born yet, has not yet truly existed. I want Ovid, Pushkin and Catullus to live once more…’

‘In transparent Petropolis we will leave only bone’

In transparent Petropolis we will leave only bone,

here where we are ruled by Proserpina.

We drink the air of death, each breath of the wind’s moan,

and every hour is our death-hour’s keeper.

Sea-goddess, thunderous Athena,

remove your vast carapace of stone.

In transparent Petropolis we will leave only bone:

Here Proserpine is our Tsarina.

Note: Petropolis, a Greek version of Petersburg, was Pushkin’s and Derzhavin’s name for St. Petersburg, Peter the Great’s granite city on the River Neva, his ‘window on Europe’. The poem was written during the early years of the Revolution.

‘From a Fearful height, a wandering light’

From a fearful height, a wandering light,

but does a star glitter like this, crying?

Transparent star, wandering light,

your brother, Petropolis, is dying.

From a fearful height, earthly dreams are alight,

and a green star is crying.

Oh star, if you are the brother of water and light

your brother, Petropolis, is dying.

A monstrous ship, from a fearful height

is rushing on, spreading its wings, flying -

Green star, in beautiful poverty,

your brother, Petropolis, is dying.

Transparent spring has broken, above the black Neva’s hiss,

the wax of immortality is liquefying.

Oh if you are star – your city, Petropolis,

your brother, Petropolis, is dying.

‘Brothers, let us glorify freedom’s twilight’ –

Brothers, let us glorify freedom’s twilight –

the great, darkening year.

Into the seething waters of the night

heavy forests of nets disappear.

O Sun, judge, people, your light

is rising over sombre years

Let us glorify the deadly weight

the people’s leader lifts with tears.

Let us glorify the dark burden of fate,

power’s unbearable yoke of fears.

How your ship is sinking, straight,

he who has a heart, Time, hears.

We have bound swallows

into battle legions - and we,

we cannot see the sun: nature’s boughs

are living, twittering, moving, totally:

through the nets –the thick twilight - now

we cannot see the sun, and Earth floats free.

Let’s try: a huge, clumsy, turn then

of the creaking helm, and, see -

Earth floats free. Take heart, O men.

Slicing like a plough through the sea,

Earth, to us, we know, even in Lethe’s icy fen,

has been worth a dozen heavens’ eternity.

The Age

My beast, my age, who will try

to look you in the eye,

and weld the vertebrae

of century to century,

with blood? Creating blood

pours out of mortal things:

only the parasitic shudder,

when the new world sings.

As long as it still has life,

the creature lifts its bone,

and, along the secret line

of the spine, waves foam.

Once more life’s crown,

like a lamb, is sacrificed,

cartilage under the knife -

the age of the new-born.

To free life from jail,

and begin a new absolute,

the mass of knotted days

must be linked by means of a flute.

With human anguish

the age rocks the wave’s mass,

and the golden measure’s hissed

by a viper in the grass.

And new buds will swell, intact,

the green shoots engage,

but your spine is cracked

my beautiful, pitiful, age.

And grimacing dumbly, you writhe,

look back, feebly, with cruel jaws,

a creature, once supple and lithe,

at the tracks left by your paws.

‘This night is irredeemable.’

This night is irredeemable.

Where you are, it is still bright.

At the gates of Jerusalem,

a black sun is alight.

The yellow sun is hurting,

sleep, baby, sleep.

The Jews in the Temple’s burning

buried my mother deep.

Without rabbi, without blessing,

over her ashes, there,

the Jews in the Temple’s burning

chanted the prayer.

Over this mother,

Israel’s voice was sung.

I woke in a glittering cradle,

lit by a black sun.

Note: Written in 1916 it glitters with a terrible prophecy. The black sun recurs as an image in Mandelshtam, associated also with Pushkin’s burial at night and Euripides’ ‘Phaedra’. See the fragments of Mandelshtam’s unpublished essay ‘Pushkin and Scriabin’, the poem Phaedra in ‘Tristia’, and the poem ‘We shall meet again in Petersburg.’ (Translated in my small selection of Russian Poems: ‘Clear Voices’)

Tristia

I have studied the Science of departures,

in night’s sorrows, when a woman’s hair falls down.

The oxen chew, there’s the waiting, pure,

in the last hours of vigil in the town,

and I reverence night’s ritual cock-crowing,

when reddened eyes lift sorrow’s load and choose

to stare at distance, and a woman’s crying

is mingled with the singing of the Muse.

Who knows, when the word ‘departure’ is spoken

what kind of separation is at hand,

or of what that cock-crow is a token,

when a fire on the Acropolis lights the ground,

and why at the dawning of a new life,

when the ox chews lazily in its stall,

the cock, the herald of the new life,

flaps his wings on the city wall?

I like the monotony of spinning,

the shuttle moves to and fro,

the spindle hums. Look, barefoot Delia’s running

to meet you, like swansdown on the road!

How threadbare the language of joy’s game,

how meagre the foundation of our life!

Everything was, and is repeated again:

it’s the flash of recognition brings delight.

So be it: on a dish of clean earthenware,

like a flattened squirrel’s pelt, a shape,

forms a small, transparent figure, where

a girl’s face bends to gaze at the wax’s fate.

Not for us to prophesy, Erebus, Brother of Night:

Wax is for women: Bronze is for men.

Our fate is only given in fight,

to die by divination is given to them.

Note: Mandelstam wrote: ‘In night’s stillness a lover speaks one tender name instead of the other, and suddenly knows that this has happened before: the words, and her hair, and the cock crowing under the window, that already crowed in Ovid’s Tristia. And he is overcome by the deep delight of recognition....’ in ‘The Word and Culture’ in Sobraniye sochineniy. The reference is to the night before Ovid’s departure to his Black Sea exile, in his Tristia Book I iii.

Divination was carried out by girls, who melted candle wax on the surface of a shallow dish of water, to form random shapes.

Erebus was the son of Chaos, and Night his sister. In versions of the Greek myths Eros and Nemesis are the children of Erebus and Night. Erebus is also a place of shadows between Earth and Hades.

Verse 3 echoes Tibullus’s poem to Delia Book I III 90-91 and Pushkin’s early (1812) poems to‘Delia’.

‘Sisters – Heaviness and Tenderness – you look the same’

Sisters - Heaviness and Tenderness- you look the same.

Wasps and bees both suck the heavy rose.

Man dies, and the hot sand cools again.

Carried off on a black stretcher, yesterday’s sun goes.

Oh, honeycombs’ heaviness, nets’ tenderness,

it’s easier to lift a stone than to say your name!

I have one purpose left, a golden purpose,

how, from time’s weight, to free myself again.

I drink the turbid air like a dark water.

The rose was earth; time, ploughed from underneath.

Woven, the heavy, tender roses, in a slow vortex,

the roses, heaviness and tenderness, in a double-wreath.

Note: Mandelstam in his essay ‘Word and Culture’ said ‘Poetry is the plough that turns up time, so that the deepest layer, its black earth, is on top.’

‘I don’t remember the word I wished to say.’

I don’t remember the word I wished to say.

The blind swallow returns to the hall of shadow,

on shorn wings, with the translucent ones to play.

The song of night is sung without memory, though.

No birds. No blossoms on the dried flowers.

The manes of night’s horses are translucent.

An empty boat drifts on the naked river.

Lost among grasshoppers the word’s quiescent.

It swells slowly like a shrine, or a canvas sheet,

hurling itself down, mad, like Antigone,

or falls, now, a dead swallow at our feet.

with a twig of greenness, and a Stygian sympathy.

O, to bring back the diffidence of the intuitive caress,

and the full delight of recognition.

I am so fearful of the sobs of The Muses,

the mist, the bell-sounds, perdition.

Mortal creatures can love and recognise: sound may

pour out, for them, through their fingers, and overflow:

I don’t remember the word I wished to say,

and a fleshless thought returns to the house of shadow.

The translucent one speaks in another guise,

always the swallow, dear one, Antigone....

on the lips the burning of black ice,

and Stygian sounds in the memory.

Note: Mandelstam uses the term Aonides for the Muses, so called because their haunt of Mount Helicon was in Aonia an early name for Boeotia. (See Ovid Metamorphoses V333, and VI 2). The Antigone referred to may be the daughter of Laomedon turned into a bird, Ovid VI 93 says a stork, rather than Sophocles’s Antigone. The crane or stork was associated with the alphabet. (See Graves: The White Goddess). In dark times the word is a bird of the underworld communing with the shades of the dead. Recognition is a key word for Mandelstam, see the poem Tristia. He considers himself no longer mortal, beyond the living, and therefore inspired by the darkness, and not the light of love and recognition.

‘For joy’s sake, from my hands,’

For joy’s sake, from my hands,

take some honey and some sun,

as Persephone’s bees told us.

Not to be freed, the unmoored boat.

Not to be heard, fur-booted shadows.

Not to be silenced, life’s dark terrors.

Now we only have kisses,

dry and bristling like bees,

that die when they leave the hive.

Rustling in clear glades of night,

in the dense forests of Taygetos,

time feeds them; honeysuckle; mint.

For joy’s sake take my strange gift,

this simple thread of dead, dried bees,

turned honey in the sun.

Note: Persephone, the Goddess of the Underworld as an aspect of the Triple Goddess, equates to the Great Goddess of Crete, to whom the bees, honey and the hive were sacred. Wax and honey were products of the goddess, and symbolise poetry and art, the products of artifice, made by the craft of the bees, and embodied in them. Persephone’s bees are therefore the songs of the darkness, of dark times. Taygetos, the mountain range above Sparta (extending from Arcadia to Taenarum, separating Laconia and Messenia) sacred to Apollo and Artemis (the God of Art, and the incarnation of the Great Goddess respectively) produced a darker honey than Hymettos near Athens. The Russian state is equated to Sparta and its militaristic mode of governance. The dried, dead bees are the poems, strung on a thread of spirit, that, when they leave the lips, ‘die’ into the stillness of the word.

‘The ranks of human heads dwindle: they’re far away.’

The ranks of human heads dwindle: they’re far away.

I vanish there, one more forgotten one.

But in loving words, in childrens’ play,

I shall rise again, to say – the Sun!

‘Your thin shoulders whips will redden’

Your thin shoulders whips will redden,

whips will redden, and ice make leaden.

Your childish arms will heave rail-tracks,

heave rail-tracks and sew mail-sacks.

Your tender feet will tread naked on glass,

tread naked on glass; and blood-wet sand pass.

And for you, I am here, to burn - a black flare,

to burn - a black flare, frightened of prayer.

‘This is what I most want’

This is what I most want

un-pursued, alone

to reach beyond the light

that I am furthest from.

And for you to shine there-

no other happiness-

and learn, from starlight,

what its fire might suggest.

A star burns as a star,

light becomes light,

because our murmuring

strengthens us, and warms the night.

And I want to say to you

my little one, whispering,

I can only lift you towards the light

by means of this babbling.

Note: Written for his wife, Nadezhda.

‘A flame is in my blood’

A flame is in my blood

burning dry life, to the bone.

I do not sing of stone,

now, I sing of wood.

It is light and coarse:

made of a single spar,

the oak’s deep heart,

and the fisherman’s oar.

Drive them deep, the piles:

hammer them in tight,

around wooden Paradise,

where everything is light.

Note: A poem from his early collection ‘Stone’ here translated, out of historical sequence, as an envoi, setting lightness against the heaviness of that stone world that Mandelstam encountered, and, in the spirit, overcame.

In his essay ‘Morning of Acmeism’ (1913, published 1919) Mandelshtam took stone as a symbol of the free word, quoting Tyutchev, and saw poetry architecturally as in Dante, and in the context of the human being as an anonymous, indispensable, stone in the Gothic structure, of his essay on Villon (1910 published 1913). This poem however suggests to me a movement forward from this concept to poetry as the dark ploughed earth, and then the more fluid bird-flight and flute-music of his later poetry, the word as Psyche, wandering around the thing, and freely choosing its places to live in, as he suggests in the important essay ‘Word and Culture’ (1921, revised 1928)

Index by First Line

- Only to read childrens’ books,

- On the pale-blue enamel,

- What shall I do with this body they gave me,

- A speechless sadness

- There is no need for words:

- She has not yet been born:

- Night, maybe you don’t need

- Orioles are in the woods, and in tonic verse

- Nature - is Rome, and mirrored there.

- Insomnia. Homer. Taut canvas.

- Herds of horses whinny and graze.

- In transparent Petropolis we will leave only bone,

- From a fearful height, a wandering light,

- Brothers, let us glorify freedom’s twilight –

- My beast, my age, who will try

- This night is irredeemable.

- I have studied the Science of departures,

- Sisters - Heaviness and Tenderness- you look the same.

- I don’t remember the word I wished to say.

- For joy’s sake, from my hands,

- The ranks of human heads dwindle: they’re far away.

- Your thin shoulders whips will redden,

- This is what I most want

- A flame is in my blood