Federico García Lorca

Poems of Love and Death

Y mi sangre sobre el campo

sea rosado y dulce limo

donde claven sus azadas

los cansados campesinos.

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2007-2023, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Please note that Federico García Lorca's original, Spanish works may not be in the public domain in all jurisdictions, notably the United States of America. Where the original works are not in the public domain, any required permissions should also be sought from the representatives of the Lorca estate, Casanovas & Lynch Agencia Literaria.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction

- From: Libro de Poemas, 1921

- Weather-Vane (Veleta)

- New Songs (Cantos Nuevos)

- Dream (Sueño)

- Ballad of the Small Plaza (Balada de la placate)

- The Ballad of the Salt-Water (La balada del agua del mar)

- Wish (Deseo)

- Invocation to the Laurel (Invocación al laurel)

- From: Poema del cante jondo, 1921

- The Little Ballad of the Three Rivers (Baladilla de los tres ríos)

- Landscape (Paisaje)

- The Guitar (La guitarra)

- The Footsteps of la Siguiriya (El paso de la siguiriya)

- Cellar Song (Cueva)

- Paso (The Images of the Passion)

- Journey (Camino)

- Lola (La Lola)

- Village (Pueblo: poema de la soleá)

- Juan Breva

- Singing Café (Café cantante)

- Malagueña

- From: Primeras canciones, 1922

- Variation (Variación)

- Remanso, Final Song (Remanso, Canción final)

- Captive (Cautiva)

- From: Canciones, 1921-1924

- Little Song of Seville (Cancioncilla sevillana)

- Adelina Walking By (Adelina de paseo)

- Song of the Rider (Canción del jinete)

- It’s True (Es verdad)

- Tree, Tree (Arbolé, arbolé)

- Prince (Galán)

- Venus

- The Moon Wakes (La luna asoma)

- Two Moons of Evening (Dos lunas de tarde)

- Second Anniversary (Segundo aniversario)

- Schematic Nocturne (Nocturno esquemático)

- Lucía Martínez

- Farewell (Despedida)

- Little Song of First Desire (Cancioncilla del primer deseo)

- Prelude (Preludio)

- Song of the Barren Orange Tree (Canción del Naranjo seco)

- Serenade (Serenata)

- Sonnet (Soneto)

- From: Poemas sueltos (Uncollected poems)

- Every Song (Cada canción)

- Earth (Terra)

- Berceuse for a Mirror sleeping (Berceuse al Espejo dormido)

- Ode to Salvador Dalí (Oda a Salvador Dalí)

- Night-Song of the Andalusian Sailors (Canto nocturno de los marineros andaluces)

- Running (Corriente)

- Towards (Hacia)

- Return (Recodo)

- Flash of Light (Ráfaga)

- Madrigals (Madrigales)

- The Garden (El Jardín)

- Print of the Garden II (Estampas del jardín II)

- Song of the Boy with Seven Hearts (Cancíon del muchacho de siete corazones)

- The Dune (Duna)

- Encounter (Encuentro)

- Two Laws (Normas)

- Sonnet (Soneto)

- From: Gypsy Ballads (Romancero Gitano), 1924-1927

- Romance de la Luna, Luna

- Preciosa and the Breeze (Preciosa y el aire)

- The Quarrel (Reyerta)

- Romance Sonámbulo

- The Gypsy Nun (La monja gitana)

- The Unfaithful Wife (La casada infiel)

- Ballad of the Black Sorrow (Romance de la pena negra)

- Saint Michael (San Miguel)

- Saint Gabriel (San Gabriel)

- Romance of the Spanish Civil Guard (Romance de la Guardia Civil española)

- Thamar and Amnon (Thamar y Amnón)

- From: Poet in New York (Poeta en Nueva York), 1929-1930

- The Dawn (La aurora)

- Double Poem of Lake Eden (Poema doble del lago Edén)

- Death

- Ode to Walt Whitman

- The Poet Arrives in Havana (El poeta llega a la Habana)

- From: Bodas de sangre: Blood Wedding: Act I: 1933

- Lullaby of the Great Stallion (Nana del caballo grande)

- From: Llanto por Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, 1935

- Lament for Ignacio Sánchez Mejías

- From: Six Galician Poems (Seis poemas Gallegos), 1935

- Madrigal for the City of Santiago

- Nocturne of the Drowned Youth

- Dance of the Santiago Moon

- From: The Tamarit Divan (Diván del Tamarit), 1936

- Ghazal of Unexpected Love (Gacela del amor imprevisto)

- Ghazal of the Terrible Presence (Gacela de la terrible presencia)

- Ghazal of the Bitter Root (Gacela de la raíz amarga)

- Ghazal of the Flight (Gacela de la huida)

- Ghazal of Dark Death (Gacela de la muerte oscura)

- Casida of One Wounded by Water (Casida del herido por el agua)

- Casida of the Weeping (Casida del llanto)

- Casida of the Branches (Casida de los ramos)

- Casida of the Recumbent Woman (Casida de la mujer tendida)

- Casida of the Impossible Hand (Casida de la mano imposible)

- Casida of the Rose (Casida de la Rosa)

- Casida of the Golden Girl (Casida de la muchacha dorada)

- Casida of the Dark Doves (Casida de las palomas oscuras)

- From: Sonnets of Dark Love (Sonetos del amor oscuro), 1936

- Wounds of Love (Llagas de amor)

- Sonnet of the Wreath of Roses (Soneto de la guirnalda de las rosas)

- The Poet asks his Love to write (El poeta pide a su amor que le escribe)

- O Secret Voice of Hidden Love! (Ay voz secreta del amor oscuro!)

- Sonnet of the Sweet Complaint (Soneto de la dulce queja)

- Night of Insomniac Love

- The Beloved Sleeps on the Breast of the Poet (El amor duerme en el pecho de poeta)

- Index of First Lines

Translator’s Introduction

Federico García Lorca (1898-1936), poet, playwright, and theatre director was a member of the early twentieth century group of Spanish poets who introduced the tenets of European movements (including symbolism, futurism, and surrealism) to Spanish literature. He was born in Fuente Vaqueros, near Granada, and educated in Granada and Madrid, where he befriended Dalí, Buñuel and Jiménez. His work became widely known on the publication of Romancero gitano (Gypsy Ballads, 1928), which incorporated themes and motifs from his native Andalusia, in a stylistically avant-garde manner. After his visit to the Americas, and New York City (1929 -1930), the latter recalled in the poems of Poeta en Nueva York (Poet in New York, 1942) Lorca returned to Spain where he wrote his later plays, Blood Wedding (1932), Yerma (1934), and The House of Bernarda Alba (1936).

The poet was executed by Nationalist forces at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. His remains have not been found, while the motive for his death remains in dispute; speculatively it was aroused by his sexual orientation, his politics, or both, while a personal dispute nonetheless remains a strong possibility. Lorca’s poetry appeals through its immediacy, its skilful exploitation of the vibrant Spanish language, its transmission of iconic elements of Andalusian culture, and its emotional intensity and honesty. Its apparent simplicity is often deceptive, while its resonances are moving and profound; though, truly, little can be said of it that is not better expressed by the poems themselves.

From: Libro de Poemas, 1921

Weather-Vane (Veleta)

(July 1920, Fuente Vaqueros, Granada)

Wind of the South.

Dark-haired, ardent,

you come over my flesh

bringing me seed

of brilliant

gazes, soaked

in orange blossom.

You make the moon red

and make a sobbing

in the captive poplars, but you come

too late!

I’ve rolled up the night of my story

on the shelf!

Without any wind,

Look out!

Spin, heart;

spin, heart.

Breeze of the North,

white bear of the wind!

you come over my flesh

trembling with auroras

boreales,

with your cloak

of spectral captains

and screaming with laughter

at Dante.

O polisher of stars!

But you come

too late.

My chest is covered with moss

and I’ve lost the key.

Without any wind,

Look out!

Spin, heart;

spin, heart.

Gnomish airs, and winds

from nowhere.

Mosquitoes of the rose

with pyramidal petals,

Trade winds weaned

among the rough trees,

flutes in the tempest,

leave me be!

Strong chains hold

my memory,

and the bird is captive

whose warbling draws

the evening.

The things that are gone never return,

all the world knows that,

and among the clear crowd of the winds

it’s useless to complain.

Isn’t that so, poplar, master of the breeze?

It’s useless to complain!

Without any wind,

Look out!

Spin, heart;

spin, heart.

New Songs (Cantos Nuevos)

The afternoon speaks: ‘I am thirsty for shadows!’

The moon speaks: ‘I thirst for stars.’

The crystalline fountain asks for lips

and the wind for sighs.

I am thirsty for perfumes and laughter.

I thirst for new songs

without moons or irises,

and without loves that have died.

A song of the morning that might tremble

the quiet still pools

of the future. And fill with hope

their waves and mud.

A song, luminous and restful,

full of pensiveness,

innocent of miseries and anguish,

innocent of dream.

A song without lyric substance that fills

the silence with laughter.

(A flock of blind doves

thrown into mystery.)

A song that might go to the soul of things

and to the soul of the winds

and that might rest at last in the joy

of the eternal heart.

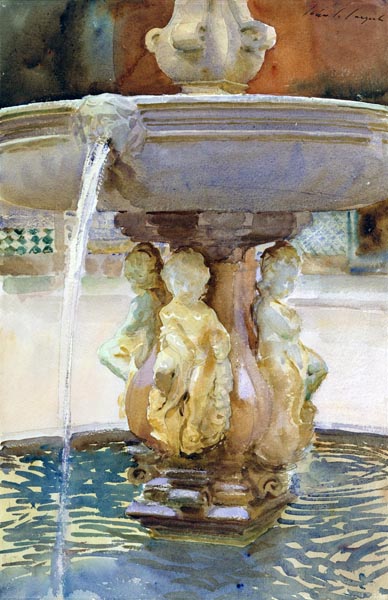

Dream (Sueño)

My heart rests, by the cold fountain.

(Fill it with threads,

spider of silence.)

The fountain-water sang it the song.

(Fill it with threads,

spider of silence.)

My heart, waking, sang its desires.

(Spider of nothingness,

spin your mystery.)

The fountain-water listened sombrely.

(Spider of nothingness,

spin your mystery.)

My heart falls into the cold of the fountain.

(White hands, far-out,

hold back the water.)

The water carries it, singing with joy.

(White hands, far-out,

nothing there in the water!)

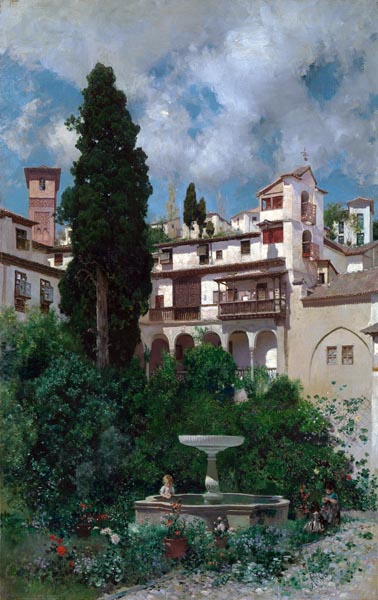

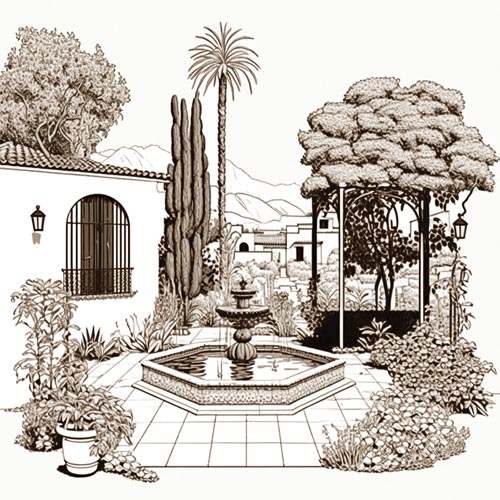

Spanish Fountain (1912)

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925)

Artvee

Ballad of the Small Plaza (Balada de la placate)

Singing of children

in the night silence:

Light of the stream, and

calm of the fountain!

The Children What does your heart hold,

divine in its gladness?

Myself A peal from the bell-tower,

lost in the dimness.

The Children You leave us singing

in the small plaza.

Light of the stream, and

calm of the fountain!

What do you hold in

your hands of springtime?

Myself A rose of blood, and

a lily of whiteness.

The Children Dip them in water

of the song of the ages.

Light of the stream, and

calm of the fountain!

What does your tongue feel,

scarlet and thirsting?

Myself A taste of the bones

of my giant forehead.

The Children Drink the still water

of the song of the ages.

Light of the stream, and

calm of the fountain!

Why do you roam far

from the small plaza?

Myself I go to find Mages

and find princesses.

The Children Who showed you the road there,

the road of the poets?

Myself The fount and the stream of

the song of the ages.

The Children Do you go far from

the earth and the ocean?

Myself It’s filled with light, is

my heart of silk, and

with bells that are lost,

with bees and with lilies,

and I will go far off,

behind those hills there,

close to the starlight,

to ask of the Christ there

Lord, to return me

my child’s soul, ancient,

ripened with legends,

with a cap of feathers,

and a sword of wood.

The Children You leave us singing

in the small plaza.

Light of the stream, and

calm of the fountain!

Enormous pupils

of the parched palm fronds

hurt by the wind, they

weep their dead leaves.

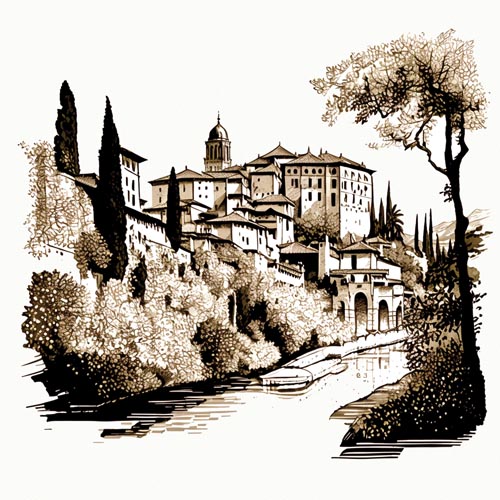

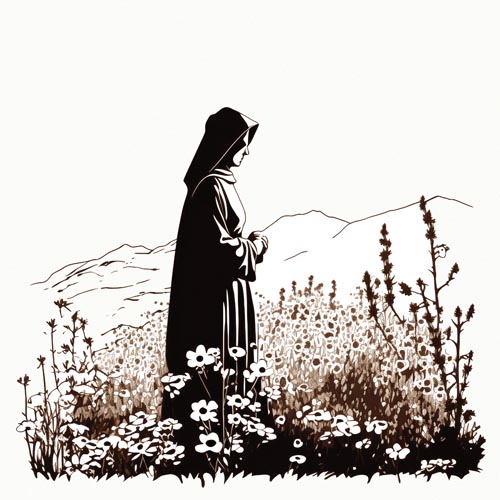

A Spanish Garden (1871)

Martin Rico y Ortega (Spanish, 1833-1908)

Artvee

The Ballad of the Salt-Water(La balada del agua del mar)

The sea

smiles far-off.

Spume-teeth,

sky-lips.

‘What do you sell, troubled child,

child with naked breasts?’

‘Sir, I sell

salt-waters of the sea.’

‘What do you carry, dark child,

mingled with your blood?’

‘Sir, I carry

salt-waters of the sea.’

‘These tears of brine

where do they come from, mother?’

‘Sir, I cry

salt-waters of the sea.’

‘Heart, this deep bitterness,

where does it rise from?’

‘So bitter, the salt-waters

of the sea!’

The sea

smiles far-off.

Spume-teeth.

Sky-lips.

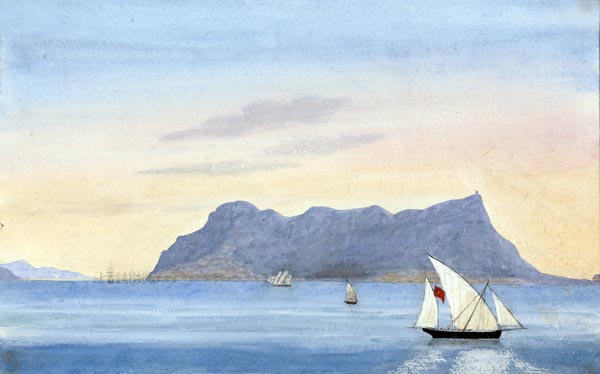

The Rock of Gibraltar from Algeciras(Spain) (1843)

George Lothian Hall (English, 1825-1888)

Artvee

Wish (Deseo)

Just your hot heart,

nothing more.

My Paradise, a field,

no nightingales,

no strings,

a river, discrete,

and a little fountain.

Without the spurs,

of the wind, in the branches,

without the star,

that wants to be leaf.

An enormous light

that will be

the glow

of the Other,

in a field of broken gazes.

A still calm

where our kisses,

sonorous circles

of echoes,

will open, far-off.

And your hot heart,

nothing more.

Invocation to the Laurel (Invocación al laurel)

(1919 For Pepe Cienfuegos)

Over the horizon, lost in confusion,

came the sad night, pregnant with stars.

I, like the bearded mage of the tales,

knew the language of stones and flowers.

I learned the secrets of melancholy,

told by cypresses, nettles and ivy;

I knew the dream from lips of nard,

sang serene songs with the irises.

In the old forest, filled with its blackness,

all of them showed me the souls they have;

the pines, drunk on aroma and sound;

the old olives, burdened with knowledge;

the dead poplars, nests for the ants;

the moss, snowy with white violets.

All spoke tenderly to my heart

trembling in threads of rustling silk

where water involves motionless things,

like a web of eternal harmony.

The roses there were sounding the lyre,

oaks weaving the gold of legends,

and amidst their virile sadness

the junipers spoke of rustic fears.

I knew all the passion of woodland;

rhythms of leaves, rhythms of stars.

But tell me, oh cedars, if my heart

will sleep in the arms of perfect light!

I know the lyre you prophesy, roses:

fashioned of strings from my dead life.

Tell me what pool I might leave it in,

as former passions are left behind!

I know the mystery you sing of, cypress;

I am your brother of night and pain;

we hold inside us a tangle of nests,

you of nightingales, I of sadness!

I know your endless enchantment, old olive tree,

yielding us blood you extract from the Earth,

like you, I extract with my feelings

the sacred oil

held by ideas!

You all overwhelm me with songs;

I ask only for my uncertain one;

none of you will quell the anxieties

of this chaste fire

that burns in my breast.

O laurel divine, with soul inaccessible,

always so silent,

filled with nobility!

Pour in my ears your divine history,

all your wisdom, profound and sincere!

Tree that produces fruits of the silence,

maestro of kisses and mage of orchestras,

formed from Daphne’s roseate flesh

with Apollo’s potent sap in your veins!

O high priest of ancient knowledge!

O solemn mute, closed to lament!

All your forest brothers speak to me;

only you, harsh one, scorn my song!

Perhaps, oh maestro of rhythm, you muse

on the pointlessness of the poet’s sad weeping.

Perhaps your leaves, flecked by the moonlight,

forgo all the illusions of spring.

The delicate tenderness of evening,

that covered the path with black dew,

holding out a vast canopy to night,

came solemnly, pregnant with stars.

From Sevilla in Spain (1882)

Christian Skredsvig (Norwegian, 1854 – 1924)

Artvee

From: Poema del cante jondo, 1921

The Little Ballad of the Three Rivers

(Baladilla de los tres ríos)

The Guadalquivir’s stream

runs past oranges and olives.

The two rivers of Granada,

fall to wheat-fields, out of snow.

Ay, Love, that goes,

and never returns!

The Guadalquivir’s stream

has a beard of clear garnet.

The two rivers of Granada

one of sorrow, one of blood.

Ay, Love,

vanished down the wind!

For the sailing-boats,

Seville keeps a roadway:

Through the waters of Granada

only sighs can row.

Ay, Love, that went,

and never returned!

Guadalquivir – high tower,

and breeze in the orange-trees.

Darro, Genil – dead turrets,

dead, above the ponds.

Ay, Love,

vanished down the wind!

Who can say, if water carries

a ghost-fire of cries?

Ay, Love, that went,

and never returned!

Take the orange petals,

take the leaves of olives,

Andalusia, down to your sea.

Ay, Love,

vanished on the wind!

Alcazar, Segovia, Spain (1836)

David Roberts (Scottish, 1796-1864)

Artvee

Landscape (Paisaje)

The field

of olives

opens and closes,

like a fan.

Over the olives,

deep sky,

and dark rain,

of frozen stars.

Reeds, and blackness,

tremble, by the river.

Grey air shivers.

The olives

are full of cries.

A crowd

of imprisoned birds,

moving long tails

in shadow.

The Guitar (La guitarra)

It begins, the lament

of the guitar.

The wineglass of dawn

is broken.

It begins, the lament

of the guitar.

It’s useless to silence it.

Impossible

to silence it.

It cries monotonously

as the water cries,

as the wind cries

over the snow.

Impossible

to silence it.

It cries for

distant things.

Sands of the hot South

that demand white camellias.

It cries arrows with no targets,

evening with no morning,

and the first dead bird

on the branch.

Oh, the guitar!

Heart wounded deep

by five swords.

Spanish Dance (1882)

Ernst Josephson (Swedish, 1851 - 1906)

Artvee

The Footsteps of la Siguiriya (El paso de la siguiriya)

Through black butterflies

goes a girl with dark hair

joined to a white serpent

of mistiness.

Earth of light,

Sky of Earth.

She goes tied to the trembling

of a rhythm that never arrives:

she has a heart of silver

and a dagger in her hand.

‘Where do you go, Siguiriya

with a mindless rhythm?

What moon will gather up your

grief of lime and oleander?

Earth of light,

Sky of Earth.

Note: La Siguiriya, is a gipsy song, a basic form of canto jondo, the ‘deep song’ of Andalusia. Its emotionally intense lyrics do not depend on rationality and are usually in four verse lines with assonant rhyme, and syllables 6-6-11-6.

Cellar Song (Cueva)

From the cellar issue

great sobs.

(The purple

above the red.)

The gypsy evokes

distant countries.

(High towers and men

of mystery.)

On his faltering voice

his eyes travel.

(The black

above the red.)

And the whitewashed cellar

trembles in gold.

(The white

above the red.)

Paso (The Images of the Passion)

Virgin in a crinoline,

Virgin of Solitude,

spreading immensely

like a tulip-flower.

In your boat of light,

go –

through the high seas of the city.

through turbulent singing,

through crystalline stars.

Virgin in a crinoline

through the roadway’s river

you go,

down to the sea!

Journey (Camino)

A hundred riders in mourning,

where might they be going,

along the low horizon

of the orange grove?

They could not arrive

at Sevilla or Cordoba.

Nor at Granada, she who sighs

for the sea.

These drowsy horses

may carry them

to the labyrinth of crosses

where the singing trembles.

With seven nailed sighs,

where might they be going

the hundred Andalusian riders

of the orange-grove?

Lola(La Lola)

Under the orange-tree

she washes baby-clothes.

Her eyes of green

and voice of violet.

Ay, love,

under the orange-tree in bloom!

The water in the ditch

flowed, filled with light,

a sparrow chirped

in the little olive-tree.

Ay, love,

under the orange-tree in bloom!

Later, when Lola

has exhausted the soap,

young bullfighters will come.

Ay, love,

under the orange-tree in bloom!

Village (Pueblo: poema de la soleá)

A calvary,

on the naked hillside.

Clear water.

Centenarian olives.

Through the narrow alleys,

men with cloaks on,

and on turrets,

wind-vanes, circling.

Eternally

rotating.

O lost pueblo,

in Andalusia of sorrows!

Juan Breva

Juan Breva had

the body of a giant

and the voice of a young girl.

Nothing was like his warbling.

It was itself

pain singing

behind a smile.

He evoked the lemons

of Málaga, the sleepy one,

and had in his weeping tones

the brine of the ocean.

Like Homer, he sang

blind. His voice held

something of sea with no light

and an orange squeezed dry.

Singing Café (Café cantante)

Lamps of crystal

and green mirrors.

On the dark stage

Parrala holds

a dialogue

with death.

Calls her,

she won’t come,

Calls her again.

The people

swallow their sobbing.

And in the green mirrors

long trails of silk

move.

Malagueña

Death

enters, and leaves,

the tavern.

Black horses

and sinister people

travel the deep roads

of the guitar.

And there’s a smell of salt

and of female blood

in the fevered tuberoses

of the shore.

Death

enters and leaves,

and leaves and enters

the death

of the tavern.

From: Primeras canciones, 1922

Variation (Variación)

The remanso of air

under the branch of echo.

The remanso of water

under a frond of stars.

The remanso of your mouth

under a thicket of kisses.

Note. A remanso is a still pool in a running stream.

Remanso, Final Song (Remanso, Canción final)

The night is coming.

The moonlight strikes

on evening’s anvil.

The night is coming.

A giant tree clothes itself

in the leaves of cantos.

The night is coming.

If you came to see me,

on the path of storm-winds....

The night is coming.

...you would find me crying,

under high, black poplars.

Ay, girl with the dark hair!

Under high, black poplars.

Captive (Cautiva)

Through the indecisive

branches

went a girl

who was life.

Through the indecisive

branches.

She reflected daylight,

with a tiny mirror,

which was the splendour,

of her unclouded forehead.

Through the indecisive

branches.

In the dark of night,

lost, she wandered,

weeping the dew,

of this imprisoned time.

Through the indecisive

branches.

From: Canciones, 1921-1924

Little Song of Seville (Cancioncilla sevillana)

At the dawn of day

in the orange grove.

Little bees of gold

searching for honey.

Where is the honey

then?

It’s in the flower of blue,

Isabel.

In the flower

there, of rosemary.

(A little gold chair,

for the Moor,

A tinsel chair,

for his spouse.)

At the dawn of day

in the orange grove.

From Sevilla in Spain (1882)

Ernst Josephson (Swedish, 1851 - 1906)

Artvee

Adelina Walking By (Adelina de paseo)

The sea has no oranges,

Sevilla has no love.

Dark-haired girl, what fiery light.

Lend me your parasol.

It will give me green cheeks

- juice of lime and lemon -

Your words – little fishes –

will swim all around us.

The sea has no oranges.

Ay, love.

Sevilla has no love!

Palm Sunday in Spain (1873)

Jehan Georges Vibert (French, 1840 – 1902)

Artvee

Song of the Rider (Canción del jinete)

Córdoba.

Far away, and lonely.

Full moon, black pony,

olives against my saddle.

Though I know all the roadways

I’ll never get to Córdoba.

Through the breezes, through the valley,

red moon, black pony.

Death is looking at me

from the towers of Córdoba.

Ay, how long the road is!

Ay, my brave pony!

Ay, death is waiting for me,

before I get to Córdoba.

Córdoba.

Far away, and lonely.

It’s True (Es verdad)

Ay, the pain it costs me

to love you as I love you!

For love of you, the air, it hurts,

and my heart,

and my hat, they hurt me.

Who would buy it from me,

this ribbon I am holding,

and this sadness of cotton,

white, for making handkerchiefs with?

Ay, the pain it costs me

to love you as I love you!

Tree, Tree (Arbolé, arbolé)

Sapling, sapling,

Dry and green.

The girl with the lovely face,

goes, gathering olives.

The wind, that towering lover,

takes her by the waist.

Four riders go by

on Andalusian ponies,

in azure and emerald suits,

in long cloaks of shadow.

‘Come to Cordoba, sweetheart!’

The girl does not listen.

Three young bullfighters go by,

slim-waisted in suits of orange,

with swords of antique silver.

‘Come to Sevilla, sweetheart!’

The girl does not listen.

When the twilight purples,

with the daylight’s dying,

a young man goes by, holding

roses, and myrtle of moonlight.

‘Come to Granada, my sweetheart!’

But the girl does not listen.

The girl, with the lovely face,

goes on gathering olives,

while the wind’s grey arms

go circling her waist.

Sapling, sapling,

Dry and green.

Prince (Galán)

Prince,

little prince.

In your house they’re burning thyme.

Whether you’re going, whether you’re coming,

I will lock the door with a key.

With a key of pure silver.

Tied up with a ribbon.

On the ribbon there’s a message:

My heart is far away.

Don’t pace up and down my street.

All that’s allowed there is the wind!

Prince,

little prince.

In your house they’re burning thyme.

Venus

(So, I saw you)

The young girl dead

in the seashell of the bed,

naked of flowers and breezes

rose in the light unending.

The world was left behind,

lily of cotton and shadows,

revealing in crystal panes

the infinite transit’s coming.

The young girl dead,

ploughed love inside.

Among the foaming sheets

her hair was wasted.

The Moon Wakes (La luna asoma)

When the moon sails out

the bells fade into stillness

and there emerge the pathways

that can’t be penetrated.

When the moon sails out

the water hides earth’s surface,

the heart feels like an island

in the infinite silence.

Nobody eats an orange

under the moon’s fullness.

It is correct to eat, then,

green and icy fruit.

When the moon sails out

with a hundred identical faces,

the coins made of silver

sob in your pocket.

Two Moons of Evening (Dos lunas de tarde)

(For Laurita, friend of my sister)

I

The Moon is dying, dying:

but will be born again in the spring.

When on the brow of the poplars

is curled the wind from the south.

When our hearts have given

their harvest of sighing.

When the rooftops are wearing

their little sombreros of weeds.

The moon is dying, dying:

but will be reborn in the spring.

II

(For Isabelita, my sister)

The evening is chanting

a berceuse to the oranges.

My little sister’s chanting:

the Earth is an orange.

The moon weeping cries:

I want to be an orange.

You cannot be, my child,

even if you were reddened.

Not even if you turned lemon.

What a shame that is!

Note: A berceuse is a French cradle-song.

Second Anniversary (Segundo aniversario)

The moon lays a long horn,

of light, on the sea.

Tremoring, ecstatic,

the grey-green unicorn.

The sky floats over the wind,

a huge flower of lotus.

(O you, walking alone,

in the last house of night!)

Schematic Nocturne (Nocturno esquemático)

The fennel, a serpent, and rushes.

Aroma, a sign, and penumbra.

Air, earth, and solitariness.

(The ladder lifts up to the moon.)

Lucía Martínez

Lucía Martínez.

Shadowy in red silk.

Your thighs, like the evening,

go from light to shadow.

The hidden veins of jet

darken your magnolias.

Here I am, Lucía Martínez.

I come to devour your mouth

and drag you off by the hair

into the dawn of conches.

Because I want to, because I can.

Shadowy in red silk.

Farewell (Despedida)

If I should die,

leave the balcony open.

The child is eating an orange.

(From my balcony, I see him.)

The reaper is reaping the barley.

(From my balcony, I hear him.)

If I should die,

leave the balcony open.

Little Song of First Desire (Cancioncilla del primer deseo)

In the green morning

I wanted to be a heart.

Heart.

And in the ripe evening

I wanted to be a nightingale.

Nightingale.

(Soul,

go the colour of oranges.

Soul

go the colour of love.)

In the living morning

I wanted to be me.

Heart.

And at evening’s fall

I wanted to be my voice.

Nightingale.

Soul

go the colour of oranges.

Soul,

go the colour of love!

Prelude (Preludio)

(From Amor: with wings and arrows)

The poplar groves are going,

but leave us their reflection.

The poplar groves are going,

but leave us the breeze.

The breeze is shrouded

full length below the heavens.

But it has left there, floating,

its echoes on the rivers.

The world of the glow-worms

has pierced my memories.

And the tiniest of hearts

buds from my fingertips.

Song of the Barren Orange Tree (Canción del Naranjo seco)

Woodcutter.

Cut out my shadow.

Free me from the torture

of seeing myself fruitless.

Why was I born among mirrors?

The daylight revolves around me.

And the night herself repeats me

in all her constellations.

I want to live not seeing self.

I shall dream the husks and insects

change inside my dreaming

into my birds and foliage.

Woodcutter.

Cut out my shadow.

Free me from the torture

of seeing myself fruitless.

Serenade (Serenata)

(Homage to Lope de Vega)

By the river banks

the night is moistening itself

and on Lolita’s breasts

the branches die of love.

the branches die of love.

The naked night sings

over the March bridgeheads.

Lolita washes her body

with brine and tuberoses.

the branches die of love.

The night of aniseed and silver

shines on the rooftops.

Silver of streams and mirrors.

Aniseed of your white thighs.

the branches die of love.

Sonnet (Soneto)

A long ghost of silver moving

the night-wind’s sighing

opened my old hurt with its grey hand

and moved on: I was left yearning.

Wound of love that will grant my life

endless blood and pure welling light.

Cleft in which Philomel, struck dumb,

will find her grove, her grief and tender nest.

Ay, what sweet murmurs in my head!

I’ll lie down by the single flower

where your beauty floats without a soul.

And the wandering waters will turn yellow,

as my blood runs through the moist

and fragrant undergrowth of the shore.

From: Poemas sueltos (Uncollected poems)

Every Song (Cada canción)

Every song

is the remains

of love.

Every light

the remains

of time.

A knot

of time.

And every sigh

the remains

of a cry.

Earth (Terra)

We travel

over a mirror

without silver,

over a crystal

without cloud.

If the lilies were to grow

upside down,

is the roses were to grow

upside down,

if all the roots

were to face the stars

and the dead not shut

their eyes,

we would be like swans.

Berceuse for a Mirror sleeping (Berceuse al Espejo dormido)

Sleep.

Do not fear the gaze

that wanders.

Sleep.

Not the butterfly

or the word

or the furtive ray

from the keyhole

will hurt you.

Sleep.

As my heart

so, you,

mirror of mine.

Garden where love

awaits me.

Sleep without a care,

but wake

when the last one dies

the kiss on my lips.

Ode to Salvador Dalí (Oda a Salvador Dalí)

A rose in the high garden that you desire.

A wheel in the pure syntax of steel.

The mountain stripped of impressionist mist.

Greys looking out from the last balustrades.

Modern painters in their blank studios,

Sever the square root’s sterilized flower.

In the Seine’s flood an iceberg of marble

freezes the windows and scatters the ivy.

Man treads the paved streets firmly.

Crystals hide from reflections’ magic.

Government has closed the perfume shops.

The machine beats out its binary rhythm.

An absence of forests, screens and brows

Wanders the roof-tiles of ancient houses.

The air polishes its prism on the sea

and the horizon looms like a vast aqueduct.

Marines ignorant of wine and half-light,

decapitate sirens on seas of lead.

Night, black statue of prudence, holds

the moon’s round mirror in her hand.

A desire for form and limit conquers us.

Here comes the man who sees with a yellow ruler.

Venus is a white still life

and the butterfly collectors flee.

Cadaqués, the fulcrum of water and hill,

lifts flights of steps and hides seashells.

Wooden flutes pacify the air.

An old god of the woods gives children fruit.

Her fishermen slumber, dreamless, on sand.

On the deep, a rose serves as their compass.

The virgin horizon of wounded handkerchiefs,

unites the vast crystals of fish and moon.

A hard diadem of white brigantines

wreathes bitter brows and hair of sand.

The sirens convince, but fail to beguile,

and appear if we show a glass of fresh water.

O Salvador Dalí, of the olive voice!

I don’t praise your imperfect adolescent brush

or your pigments that circle those of your age,

I salute your yearning for bounded eternity.

Healthy soul, you live on fresh marble.

You flee the dark wood of improbable forms.

Your fantasy reaches as far as your hands,

and you savor the sea’s sonnet at your window.

The world holds dull half-light and disorder,

in the foreground humanity frequents.

But now the stars, concealing landscapes,

mark out the perfect scheme of their courses.

The flow of time forms pools, gains order,

in the measured forms of age upon age.

And conquered Death, trembling, takes refuge

in the straightened circle of the present moment.

Taking your palette, its wing holds a bullet-hole,

you summon the light that revives the olive-tree.

Broad light of Minerva, builder of scaffolding,

with no room for dream and its inexact flower.

You summon the light that rests on the brow,

not reaching the mouth or the heart of man.

Light feared by the trailing vines of Bacchus,

and the blind force driving the falling water.

You do well to place warning flags

on the dark frontier that shines with night.

As a painter you don’t wish your forms softened

by the shifting cotton of unforeseen clouds.

The fish in its bowl and the bird in its cage.

You refuse to invent them in sea or in air.

You stylize or copy once you have seen,

with your honest eyes, their small agile bodies.

You love a matter defined and exact,

where the lichen cannot set up its camp.

You love architecture built on the absent,

admitting the banner merely in jest.

The steel compass speaks its short flexible verse.

Now unknown islands deny the sphere.

The straight line speaks of its upward fight

and learned crystals sing their geometry.

Yet the rose too in the garden where you live.

Ever the rose, ever, our north and south!

Calm, intense like an eyeless statue,

blind to the underground struggle it causes.

Pure rose that frees from artifice, sketches,

and opens for us the slight wings of a smile.

(Pinned butterfly that muses in flight.)

Rose of pure balance not seeking pain.

Ever the rose!

O Salvador Dalí of the olive voice!

I speak of what you and your paintings tell me.

I don’t praise your imperfect adolescent brush,

but I sing the firm aim of your arrows.

I sing your sweet battle of Catalan lights,

your love of what might be explained.

I sing your heart astronomical, tender,

a deck of French cards, and never wounded.

I sing longing for statues, sought without rest,

your fear of emotions that wait in the street.

I sing the tiny sea-siren who sings to you

riding a bicycle of corals and conches.

But above all I sing a shared thought

that joins us in the dark and golden hours.

It is not Art, this light that blinds our eyes.

Rather it is love, friendship, the clashing of swords.

Rather than the picture you patiently trace,

it’s the breast of Theresa, she of insomniac skin,

the tight curls of Mathilde the ungrateful,

our friendship a board-game brightly painted.

May the tracks of fingers in blood on gold

stripe the heart of eternal Catalonia.

May stars like fists without falcons shine on you,

while your art and your life burst into flower.

Don’t watch the water-clock with membranous wings,

nor the harsh scythe of the allegories.

Forever clothe and bare your brush in the air

before the sea peopled with boats and sailors.

Night-Song of the Andalusian Sailors (Canto nocturno de los marineros andaluces)

From Cádiz to Gibraltar

how fine the road!

The sea knows I go by,

by the sighs.

Ay, girl of mine, girl of mine,

how full of boats is Málaga harbour!

From Cádiz to Sevilla

how many little lemons!

The lemon-trees know me,

by the sighs.

Ay, girl of mine, girl of mine,

how full of boats is Málaga harbour!

From Sevilla to Carmona

there isn’t a single knife.

The half-moon slices,

and, wounded, the air goes by.

Ay, boy of mine, boy of mine,

let the waves carry off my stallion!

Through the pale salt-seams

I forgot you, my love.

He who needs a heart

let him ask for my forgetting.

Ay, boy of mine, boy of mine,

let the waves carry off my stallion!

Cádiz, let the sea flow over you,

don’t advance this way.

Sevilla, on your feet,

so, you don’t drown in the river.

Ay, girl of mine!

Ay, boy of mine!

How fine the road!

How full of boats the harbour,

and how cold it is in the square!

Merida, Spain

John Varley (English, 1778-1842)

Artvee

Running (Corriente)

That which travels

clouds itself.

The flowing water

can see no stars.

That which travels

forgets itself.

And that which halts itself

dreams.

Towards (Hacia)

Turn,

Heart!

Turn.

Through the woods of love

you will see no one.

You will pour out bright fountains.

In the green

you will find the immense rose

of Always.

And you will say: ‘Love! Love!

without your wound

being closed.

Turn,

Heart!

Turn.

Return (Recodo)

I want to return to childhood

and from childhood to the shadows.

Are you going, nightingale?

Go!

I want to return to the shadows,

and from the shadows to the flower.

Are you going, fragrance?

Go!

I want to return to the flower

and from the flower

to my heart.

Are you going, love?

Farewell!

(To my abandoned heart!)

Flash of Light (Ráfaga)

She passes by, my girl.

How prettily she goes by!

With her little dress

of muslin.

And a captive

butterfly.

Follow her, my boy, then

up every byway!

And if you see her weeping

or weighing things up, then

paint her heart over

with a bit of purple

and tell her not to weep if

she was left single.

Madrigals (Madrigales)

I

Like concentric ripples

over the water,

so, in my heart

your words.

Like a bird that strikes

against the wind,

so, on my lips

your kisses.

Like exposed fountains

opposing the evening,

so, my dark eyes

over your flesh.

II

I am caught

in your circles,

concentric.

Like Saturn

I wear

the rings

of my dream.

I am not ruined by setting

nor do I rise myself.

The Garden (El Jardín)

Never born, never!

But could come into bud.

Every second it

is deepened and renewed.

Every second opens

new distinct pathways.

This way! That way!

Go my multiplying bodies.

Traversing the villages

or sleeping in the sea.

Everything is open! There are

locks for the keys.

But the sun and moon

lose us and mislead us.

And beneath our feet

the roadways are confused.

Here I’ll contemplate

all I could have been.

God or beggar,

water or ancient pearl.

My many pathways

lightly tinted

make a vast rose

round my body.

Like a map, but impossible,

the garden of the possible.

Every second it

is deepened and renewed.

Never born, never!

But could come into bud.

Print of the Garden II (Estampas del jardín II)

The Moon-widow

who could forget her?

Dreaming that Earth

might be crystal.

Furious and pallid

wishing the sea to sleep

combing her long hair

with cries of coral.

Her tresses of glass

who could forget them?

In her breast the hundred

lips of a fountain.

Spears of giant

surges guard her

by the still waves

of sea-flats.

But the Moon, Moon

when will she return?

The curtain of wind

trembles without ceasing.

The Moon-widow

who could forget her?

Dreaming that Earth

might be crystal.

Song of the Boy with Seven Hearts (Cancíon del muchacho de siete corazones)

Seven hearts

I hold.

But mine does not encounter them.

In the high mountains, mother,

the wind and I ran into each other.

Seven young girls with long fingers

carried me on their mirrors.

I have sung through the world

with my mouth of seven petals.

My galleys of amaranth

have gone without ropes or oars.

I have lived in the lands

of others, My secrets

round my throat,

without my realising it, were open!

In the high mountains, mother,

(my heart above the echoes

in the album of a star)

the wind and I ran into each other.

Seven hearts

I hold.

But mine does not encounter them.

The Dune (Duna)

On the wide sand-dune

of ancient light

I found myself confused

without a sky or road.

The moribund North

had quenched its stars.

The shipwrecked skies

rippled slowly.

Through the sea of light

where do I go? Whom do I seek?

Here the reflection wails

of veiled moons.

Ay! Let my cool sliver

of solid timber

return me to my balcony

and my living birds!

The garden will follow

shifting its borders

on the rough back

of a grounded silence.

Encounter (Encuentro)

Flower of sunlight.

Flower of water.

Myself Was that you, with breasts of fire,

so that I could not see you?

She How many times did they brush you,

the ribbons of my dress?

Myself In your sealed throat, I hear

white voices, of my children.

She Your children swim in my eyes,

like pale diamonds.

Myself Was that you, my love? Where were you,

trailing infinite clouds of hair?

She In the Moon. You smile? Well then,

round the flower of Narcissus.

Myself In my chest, preventing sleep,

a serpent of ancient kisses.

She The moment fell open, and settled

its roots on my sighs.

Myself Joined by the one breeze, face to face,

we did not know each other!

She The branches are thickening, go now.

Neither of us two has been born!

Flower of sunlight.

Flower of water.

Two Laws (Normas)

Sketch of the Moon

The law of the past encountered

in my present night.

Splendour of adolescence

that opposes snowfall.

My two children of secrecy

cannot yield you a place,

dark-haired moon-girls of air

with exposed hearts.

But my love seeks the garden

where your spirit does not die.

Sketch of the Sun

Law of hip and breast

under the outstretched branch,

ancient and newly born

power of the Spring.

Now, bee, my nakedness wants

to be the dahlia of your fate,

the murmur or wine

of your madness and number:

but my love looks for the pure

madness of breeze and warbling.

Sonnet (Soneto)

I know that my outline will be tranquil

in the north-wind of a sky without reflections,

mercury of watching, chaste mirror

where the pulse of my spirit is broken.

Because if ivy and the coolness of linen

are the law of the body I leave behind,

my outline in the sand will be the ancient

unembarrassed silence of the crocodile.

And though my tongue of frozen doves

will never hold the flavour of flame,

only the lost taste of broom,

I’ll be the free sign of laws forced

on the neck of the stiff branch

and the endless aching dahlias.

From: Gypsy Ballads (Romancero Gitano), 1924-1927

Romance de la Luna, Luna

The moon comes to the forge,

in her creamy-white petticoat.

The child stares, stares.

The child is staring at her.

In the breeze, stirred,

the moon stirs her arms

shows, pure, voluptuous,

her breasts of hard tin.

‘Away, Luna, Luna, Luna.

If the gypsies come here,

they’ll take your heart for

necklaces and white rings.’

‘Child, let me dance now.

When the gypsies come here,

they’ll find you on the anvil,

with your little eyes closed.’

‘Away, Luna, Luna, Luna,

because I hear their horses.’

‘Child, go, but do not tread

on my starched whiteness.’

The riders are coming nearer

beating on the plain, drumming.

Inside the forge, the child

has both his eyes closed.

Through the olive trees they come,

bronze, and dream, the gypsies,

their heads held upright,

their eyes half-open.

How the owl is calling.

Ay, it calls in the branches!

Through the sky goes the moon,

gripping a child’s fingers.

In the forge the gypsies

are shouting and weeping.

The breeze guards, guards.

The breeze guards it.

Spanish Peasants Dancing the Bolero (1836)

John Frederick Lewis (English, 1805-1876)

Artvee

Preciosa and the Breeze (Preciosa y el aire)

Preciosa comes playing

her moon of parchment

on an amphibious path

of crystals and laurels.

The silence without stars

fleeing from the sound,

falls to the sea that pounds and sings,

its night filled with fish.

On the peaks of the sierra

the carabineers are sleeping

guarding the white turrets

where the English live.

And the gypsies of the water

build, to amuse themselves,

bowers, out of snails

and twigs of green pine.

Preciosa comes playing

her moon of parchment.

Seeing her, the wind rises,

the one that never sleeps.

Saint Christopher, naked

full of celestial tongues

gazes at the child playing

a sweet distracted piping.

- Child, let me lift your dress

so that I can see you.

Open the blue rose of your womb

with my ancient fingers.

Preciosa hurls her tambourine

and runs without stopping.

The man-in-the-wind pursues her

with a burning sword.

The sea gathers its murmurs.

The olive-trees whiten.

The flutes of the shadows sound,

and the smooth gong of the snow.

Run, Preciosa, run,

lest the green wind catch you!

Run, Preciosa, run!

See where he comes!

The satyr of pale stars

with his shining tongues.

Preciosa, full of fear,

way beyond the pines,

enters the house that belongs,

to the English Consul.

Alarmed at her cries

three carabineers come,

their black capes belted,

and their caps over their brows.

The Englishman gives the gypsy girl

a glass of lukewarm milk,

and a cup of gin that

Preciosa does not drink.

And while, with tears, she tells

those people of her ordeal,

the angry wind bites the air

above the roofs of slate.

The Quarrel (Reyerta)

In mid-ravine

the Albacete knives

lovely with enemy blood

shine like fishes.

A hard light of playing-cards

silhouettes on the sharp green

angry horses

and profiles of riders.

In the heart of an olive-tree

two old women grieve.

The bull of the quarrel

climbs the walls.

Black angels bring

wet snow and handkerchiefs.

Angels with vast wings

like Albacete knives.

Juan Antonio of Montilla,

dead, rolls down the slope,

his corpse covered with lilies

and a pomegranate on his brow.

Now he mounts a cross of fire

on the roadway of death.

The judge, with the civil guard,

comes through the olives.

The slippery blood moans

a mute serpent song.

‘Gentlemen of the civil guard:

here it is as always.

We have four dead Romans

and five Carthaginians.’

The afternoon delirious

with figs and heated murmurs,

fainted on the horsemen’s

wounded thighs.

And black angels flew

on the west wind.

Angels with long tresses

and hearts of oil.

Romance Sonámbulo

Green, as I love you, greenly.

Green the wind, and green the branches.

The dark ship on the sea

and the horse on the mountain.

With her waist that’s made of shadow

dreaming on the high veranda,

green the flesh, and green the tresses,

with eyes of frozen silver.

Green, as I love you, greenly.

Beneath the moon of the gypsies

silent things are looking at her

things she cannot see.

Green, as I love you, greenly.

Great stars of white hoarfrost

come with the fish of shadow

opening the road of morning.

The fig tree’s rubbing on the dawn wind

with the rasping of its branches,

and the mountain thieving-cat-like

bristles with its sour agaves.

Who is coming? And from where...?

She waits on the high veranda,

green the flesh and green the tresses,

dreaming of the bitter ocean.

‘Brother, friend, I want to barter

your house for my stallion,

sell my saddle for your mirror,

change my dagger for your blanket.

Brother mine, I come here bleeding

from the mountain pass of Cabra.’

‘If I could, my young friend,

then maybe we’d strike a bargain,

but I am no longer I,

nor is this house, of mine, mine.’

‘Brother, friend, I want to die now,

in the fitness of my own bed,

made of iron, if it can be,

with its sheets of finest cambric.

Can you see the wound I carry

from my throat to my heart?’

‘Three hundred red roses

your white shirt now carries.

Your blood stinks and oozes,

all around your scarlet sashes.

But I am no longer I,

nor is this house of mine, mine.’

‘Let me then, at least, climb up there,

up towards the high verandas.

Let me climb, let me climb there,

up towards the green verandas.

High verandas of the moonlight,

where I hear the sound of waters.’

Now they climb, the two companions,

up there to the high veranda,

letting fall a trail of blood drops,

letting fall a trail of tears.

On the morning rooftops,

trembled, the small tin lanterns.

A thousand tambourines of crystal

wounded the light of daybreak.

Green, as I love you, greenly.

Green the wind, and green the branches.

They climbed up, the two companions.

In the mouth, the dark breezes

left there a strange flavour,

of gall, and mint, and sweet-basil.

‘Brother, friend! Where is she, tell me,

where is she, your bitter beauty?

How often, she waited for you!

How often, she would have waited,

cool the face, and dark the tresses,

on this green veranda!’

Over the cistern’s surface

the gypsy girl was rocking.

Green the flesh is, green the tresses,

with eyes of frozen silver.

An ice-ray made of moonlight

holding her above the water.

How intimate the night became,

like a little, hidden plaza.

Drunken Civil Guards were beating,

beating, beating on the door frame.

Green, as I love you, greenly.

Green the wind, and green the branches.

The dark ship on the sea,

and the horse on the mountain.

Note: Cabra is south-east of Córdoba, and north of Málaga, in the mountains of Andalusia. Lorca said ‘If you ask me why I wrote “A thousand tambourines of crystal, wounded the light of daybreak – Mil panderos di cristal, herían la madruga” I will tell you that I saw them in the hands of trees and angels, but I cannot say more: I cannot explain their meaning. And that is how it should be. Through poetry a man more quickly reaches the cutting edge that the philosopher and the mathematician silently turn away from.’

The Gypsy Nun (La monja gitana)

Silence of lime and myrtle.

Mallows in slender grasses.

The nun embroiders wallflowers

on a straw-coloured cloth.

In the chandelier, fly

seven prismatic birds.

The church grunts in the distance

like a bear belly upwards.

How she sews! With what grace!

On the straw-coloured cloth

she wants to embroider

the flowers of her fantasy.

What sunflowers! What magnolias

of sequins and ribbons!

What crocuses and moons

on the cloth over the altar!

Five grapefruit sweeten

in the nearby kitchen.

The five wounds-of-Christ

cut in Almería.

Through the eyes of the nun

two horsemen gallop.

A last quiet murmur

takes off her camisole.

And gazing at clouds and hills

in the strict distance,

her heart of sugar

and verbena breaks.

Oh, what a high plain

with twenty suns above it!

What standing rivers

her fantasy sees setting!

But she goes on with her flowers,

while standing, in the breeze,

the light plays chess

high in the lattice-window.

The Unfaithful Wife (La casada infiel)

So, I took her to the river

thinking she was virgin,

but it seems she had a husband.

It was the night of Saint Iago,

and it almost was a duty.

The lamps went out,

the crickets lit up.

By the last street corners

I touched her sleeping breasts,

and they suddenly had opened

like the hyacinth petals.

The starch

of her slip crackled

in my ears like silk fragments

ripped apart by ten daggers.

The tree crowns

free of silver light are larger,

and a horizon, of dogs, howls

far away from the river.

Past the hawthorns,

the reeds, and the brambles,

below her dome of hair

I made a hollow in the sand.

I took off my tie.

She took off a garment.

I my belt with my revolver.

She four bodices.

Creamy tuberoses

or shells are not as smooth as

her skin was, or, in the moonlight,

crystals shining brilliantly.

Her thighs slipped from me

like fish that are startled,

one half full of fire,

one half full of coldness.

That night I galloped

on the best of roadways,

on a mare of nacre,

without stirrups, without bridle.

As a man I cannot tell you

the things she said to me.

The light of understanding

has made me most discreet.

Smeared with sand and kisses,

I took her from the river.

The blades of the lilies

were fighting with the air.

I behaved as what I am,

as a true gypsy.

I gave her a sewing basket,

big, with straw-coloured satin.

I did not want to love her,

for though she had a husband

she said she was a virgin

when I took her to the river.

A road near Seville, Spain

John Frederick Lewis (English, 1805-1876)

Artvee

Ballad of the Black Sorrow (Romance de la pena negra)

The beaks of cockerels dig,

searching for the dawn,

when down the dark hill

comes Soledad Montoya.

Her skin of yellow copper

smells of horse and shadow.

Her breasts, like smoky anvils,

howl round-songs.

‘Soledad, who do you ask for

alone, at this hour?’

‘I ask for who I ask for,

say, what is it to you?

I come seeking what I seek,

my happiness and myself.’

‘Soledad of my regrets,

the mare that runs away

meets the sea at last

and is swallowed by the waves.’

‘Don’t recall the sea to me

for black sorrow wells

in the lands of olive-trees

beneath the murmur of leaves.’

‘Soledad, what sorrow you have!

What sorrow, so pitiful!

You cry lemon juice

sour from waiting, and your lips.’

‘What sorrow, so great! I run

through my house like a madwoman,

my two braids trailing on the floor,

from the kitchen to the bedroom.

What sorrow! I show clothes

and flesh made of jet.

Ay, my linen shifts!

Ay, my thighs of poppy!

‘Soledad: bathe your body

with the skylarks’ water

and let your heart be

at peace, Soledad Montoya.’

Down below the river sings:

flight of sky and leaves.

The new light crowns itself

with pumpkin flowers.

O sorrow of the gypsies!

Sorrow, pure and always lonely.

O sorrow of the dark river-bed

and the far dawn!

Saint Michael (San Miguel)

(Granada)

They are seen from the verandahs

on the mountain, mountain, mountain,

mules and mules’ shadows

weighed down with sunflowers.

Their eyes in the shadows

are dulled by immense night.

Salt-laden dawn rustles

in the corners of the breeze.

A sky of white mules

closes its reflective eyes,

granting the quiet half-light

a heart-filled ending.

And the water turns cold

So, no-one touches it.

Water maddened and exposed

on the mountain, mountain, mountain.

Saint Michael, covered in lace,

shows his lovely thighs,

in his tower room,

encircled by lanterns.

The Archangel, domesticated,

in the twelve-o-clock gesture,

pretends to a sweet anger

of plumage and nightingales.

Saint Michael sings in the glass,

effeminate one, of three thousand nights,

fragrant with eau-de-cologne,

and far from the flowers.

The sea dances on the sands,

a poem of balconies.

The shores of the moonlight

lose reeds, gain voices.

Field-hands are coming

eating sunflower seeds,

backsides large and dark

like planets of copper.

Tall gentlemen come by

and ladies with sad deportment,

dark-haired with nostalgia

for a past of nightingales.

And the Bishop of Manila,

blind with saffron, and poor,

speaks a two-sided mass

for the women and the men.

Saint Michael is motionless

in the bedroom of his tower,

his petticoats encrusted

with spangles and brocades.

Saint Michael, king of globes,

and odd numbers,

in the Berberesque delicacy

of cries and windowed balconies.

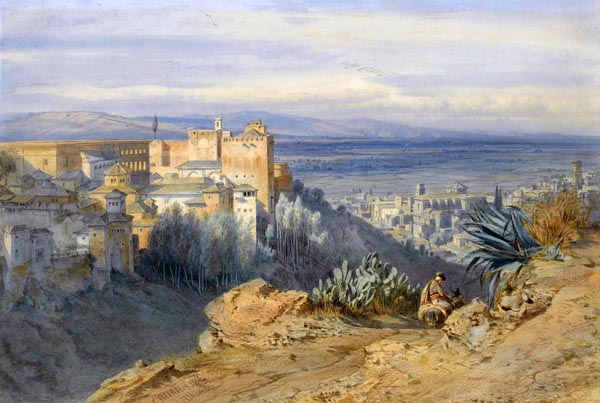

Alhambra, Spain (1856)

Carl Friedrich Heinrich Werner (German, 1808-1894)

Artvee

Saint Gabriel (San Gabriel)

(Seville)

1

A lovely reed-like boy,

wide shoulders, slim waist,

skin of nocturnal apple-trees,

sad mouth and large eyes,

with nerves of hot silver,

walks the empty street.

His shoes of leather

crush the dahlias of air,

in a double-rhythm beating out

quick celestial dirges.

On the margins of the sea

there’s no palm-tree his equal,

no crowned emperor,

no bright wandering-star.

When his head bends down

over his breast of jasper,

the night seeks out the plains,

because it needs to kneel.

The guitars sound only

for Saint Gabriel the Archangel,

tamer of pale moths,

and enemy of willows.

‘Saint Gabriel: the child cries

in his mother’s womb.

Don’t forget the gypsies

gifted you your costume.’

2

Royal Annunciation,

sweetly moonlit and poorly clothed

opens the door to the starlight

that comes along the street.

The Archangel Saint Gabriel

scion of the Giralda tower,

came to pay a visit,

between a lily and a smile.

In his embroidered waistcoat

hidden crickets throbbed.

The stars of the night

turned into bells.

‘Saint Gabriel: Here am I

with three nails of joy.

Your jasmine radiance folds

around my flushed cheeks.’

‘God save you, Annunciation.

Dark-haired girl of wonder.

You’ll have a child more beautiful

than the stems of the breeze.’

‘Ah, Saint Gabriel, joy of my eyes!

Little Gabriel my darling!

I dream a chair of carnations

for you to sit on.’

‘God save you, Annunciation,

sweetly moonlit and poorly clothed.

Your child will have on his breast

a mole and three scars.’

‘Ah, Saint Gabriel, how you shine!

Little Gabriel my darling!

In the depths of my breasts

warm milk already wells.’

God save you, Annunciation.

Mother of a hundred houses.

Your eyes shine with arid

landscapes of horsemen.’

In amazed Annunciation’s

womb, the child sings.

Three bunches of green almonds

quiver in his little voice.

Now Saint Gabriel climbed

a ladder through the air.

The stars in the night

turned to immortelles.

Romance of the Spanish Civil Guard (Romance de la Guardia Civil española)

The horses are black.

The horseshoes are black.

Stains of ink and wax

shine on their capes.

They have leaden skulls

so, they do not cry.

With souls of leather

they ride down the road.

Hunchbacked and nocturnal

wherever they move, they command

silences of dark rubber

and fears of fine sand.

They pass, if they wish to pass,

and hidden in their heads

is a vague astronomy

of indefinite pistols.

O city of the gypsies!

Banners on street-corners.

The moon and the pumpkin

with preserved cherries.

O city of the gypsies!

Who could see you and not remember?

City of sorrow and musk,

with towers of cinnamon.

When night came near,

night that night deepened,

the gypsies at their forges

beat out suns and arrows.

A badly wounded stallion

knocked against all the doors.

Roosters of glass were crowing

through Jerez de la Frontera.

Naked the wind turns

the corner of surprise,

in the night silver-night

night the night deepened.

The Virgin and Saint Joseph

have lost their castanets,

and search for the gypsies

to see if they can find them.

The Virgin comes draped

in the mayoress’s dress,

of chocolate papers

with necklaces of almonds.

Saint Joseph swings his arms

under a cloak of silk.

Behind comes Pedro Domecq

with three sultans of Persia.

The half-moon dreamed

an ecstasy of storks.

Banners and lanterns

invaded the flat roofs.

Through the mirrors wept

ballerinas without hips.

Water and shadow, shadow and water

through Jerez de la Frontera.

O city of the gypsies!

Banners on street-corners.

Quench your green lamps

the worthies are coming.

O city of the gypsies!

Who could see you and not remember?

Leave her far from the sea

without combs in her hair.

They ride two abreast

towards the festive city.

A murmur of immortelles

invades the cartridge-belts.

They ride two abreast.

A doubled nocturne of cloth.

They fancy the sky to be

a showcase for spurs.

The city, free from fear,

multiplied its doors.

Forty civil guards

enter them to plunder.

The clocks came to a halt,

and the cognac in the bottles

disguised itself as November

so as not to raise suspicion.

A flight of intense shrieks

rose from the weathercocks.

The sabers chopped at the breezes

that the hooves trampled.

Along the streets of shadow

old gypsy women ran,

with the drowsy horses,

and the jars of coins.

Through the steep streets

sinister cloaks climb,

leaving behind them

whirlwinds of scissors.

At a gate to Bethlehem

the gypsies congregate.

Saint Joseph, wounded everywhere,

shrouds a young girl.

Stubborn rifles crack

sounding in the night.

The Virgin heals children

with spittle from a star.

But the Civil Guard

advance, sowing flames,

where young and naked

imagination is burnt out.

Rosa of the Camborios

moans in her doorway,

with her two severed breasts

lying on a tray.

And other girls ran

chased by their tresses

through air where roses

of black gunpowder burst.

When all the roofs

were furrows in the earth

the dawn heaved its shoulders

in a vast silhouette of stone.

O city of the gypsies!

The Civil Guards depart

through a tunnel of silence

while flames surround you.

O city of the gypsies!

Who could see you and not remember?

Let them find you on my forehead:

a play of moon and sand.

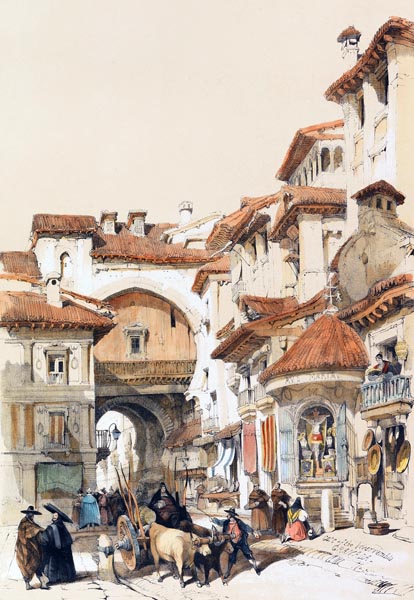

Sketches in Spain (1837)

David Roberts (Scottish, 1796-1864)

Artvee

Thamar and Amnon (Thamar y Amnón)

The moon turns in the sky

over lands without water

while the summer sows

murmurs of tiger and flame.

Over the roofs

metal nerves jangled.

Rippling air stirred

with woolly bleating.

The earth offered itself

full of scarred wounds,

or shuddering with the fierce

searing of white light.

Thamar was dreaming

of birds in her throat

to the sound of cold tambourines

and moonlit zithers.

Her nakedness in the eaves,

the sharp north of a palm-tree,

demands snowflakes on her belly,

and hailstones on her shoulders.

Thamar was singing

naked on the terrace.

Around her feet

five frozen pigeons.

Amnon, slim, precise,

watched her from the tower,

with thighs of foam,

and quivering beard.

Her bright nakedness

was stretched out on the terrace

with the murmur in her teeth

of a newly struck arrow.

Amnon was gazing

at the low, round moon,

and, in the moon, he saw

his sister’s hard breasts.

Amnon lay on his bed

at half past three.

The whole room suffered

from his eyes filled with wings.

The solid light buries

villages in brown sand,

or reveals the ephemeral

coral of roses and dahlias.

Pure captive well-water

gushes silence into jars.

The cobra stretches, sings

in the moss of tree-trunks.

Amnon moans among

the coolness of bed-sheets.

The ivy of a shiver

clothes his burning flesh.

Thamar enters silently

through the room’s silence,

the colour of vein and Danube,

troubled by distant footprints.

‘Thamar, erase my vision

with your certain dawn.

The threads of my blood weave

frills on your skirt.’

‘Let me be, brother,

your kisses on my shoulder

are wasps and little breezes

in a double swarm of flutes.’

‘Thamar, you have in your high breasts

two fishes that call to me,

and in your fingertips

the murmur of a captive rose.’

The king’s hundred horses

neighed in the courtyard.

The slenderness of the vine

resisted buckets of sunlight.

Now he grasps her by the hair,

now he tears her under-garments.

Warm corals drawing streams

on a light-coloured map.

Oh, what cries were heard

above the houses!

What a thicket of knives

and torn tunics.

Slaves go up and down

the saddened stairs.

Thighs and pistons play

under stationary clouds.

Gypsy virgins scream

around Thamar,

others gather drops

from her martyred flower.

White cloths redden

in the closed rooms.

Murmurs of warm daybreak

changing vines and fishes.

Amnon, angry violator,

flees on his pony.

Dark-skinned men loose arrows at him

from the walls and towers.

And when the four hooves

become four echoes,

King David cuts his harp-strings

with a pair of scissors.

From: Poet in New York (Poeta en Nueva York), 1929-1930

The Dawn (La aurora)

New York’s dawn holds

four mud pillars,

and a hurricane of black doves,

paddling in foul water.

New York’s dawn

moans on vast stairways,

searching on the ledges,

for anguished tuberoses.

Dawn breaks and no one’s mouth breathes it,

since hope and tomorrow, here, have no meaning.

Sometimes coins, furiously swarming,

stab and devour the abandoned children.

The first to go outside know in their bones

Paradise will not be there, nor wild loves.

They know they go to the swamp of law, and numbers,

to play without art, and labour without fruit.

The light is buried by chains and by noise,

in the shameless challenge, of rootless science.

All across the suburbs, sleepless crowds stumble,

as if saved, by the moment, from a shipwreck of blood.

Double Poem of Lake Eden (Poema doble del lago Edén)

Our cattle graze, the wind breathes

It was my ancient voice

ignorant of thick bitter juices.

I sense it lapping my feet

beneath the fragile wet ferns.

Ay, ancient voice of my love,

ay, voice of my truth,

ay, voice of my open flank,

when all the roses flowed from my tongue

and grass knew nothing of horses’ impassive teeth!

Here are you drinking my blood,

drinking my tedious childhood mood,

while in the wind my eyes are bludgeoned

by aluminium and drunken voices.

Let me pass the gates

where Eve eats ants

and Adam seeds dazzled fish.

Let me return, manikins with horns,

to the grove where I stretch

and leap with joy.

I know a rite so secret

it requires an old rusty pin

and I know the horror of open eyes

on a plate’s concrete surface.

But I want neither world nor dream, nor divine voice,

I want my freedom, my human love

in the darkest corner of breeze that no one wants.

My human love!

Those hounds of the sea chase each other

and the wind spies on careless tree trunks.

O ancient voice, burn with your tongue

this voice of tin and talc!

I long to weep because I want to,

as the children cry in the last row,

because I’m not man, nor poet, nor leaf,

but only a wounded pulse circling the things of the other side.

I want to cry out speaking my name,

rose, child and fir-tree beside this lake,

to speak my truth as a man of blood

slay in myself the tricks and turns of the word.

No, no. I’m not asking, I, desire,

voice, my freedom that laps my hands.

In the labyrinth of screens, it’s my nakedness receives

the moon of punishment and the ash-drowned clock.

Thus, I was speaking.

Thus, I was speaking when Saturn stopped the trains,

when the fog and Dream and Death were seeking me.

Seeking me

where the cows, with tiny pages’ feet, bellow

and where my body floats between opposing fulcrums.

Death

What effort!

What effort the horse exerts

To be a dog!

What effort the dog to become a swallow!

What effort the swallow to become a bee!

What effort the bee to become a horse!

And the horse,

what a sharp shaft it steals from the rose!

what grey rosiness lifts from its lips!

And the rose,

what a flock of lights and cries

caught in the living sap of its stem!

And the sap,

what thorns it dreams in its vigil!

And the tiny daggers

what moon, and no stable, what nakedness,

skin eternal and reddened, they go seeking!

And I, in the eaves,

what a burning seraph I seek and am!

But the arch of plaster,

how vast, invisible, how minute,

without effort!

Ode to Walt Whitman

By the East River and the Bronx

boys sang, stripped to the waist,

along with the wheels, oil, leather and hammers.

Ninety thousand miners working silver from rock

and the children drawing stairways and perspectives.

But none of them slumbered,

none of them wished to be river,

none loved the vast leaves,

none the blue tongue of the shore.

By East River and the Queensboro

boys battled with Industry,

and Jews sold the river faun

the rose of circumcision

and the sky poured, through bridges and rooftops,

herds of bison driven by the wind.

But none would stop,

none of them longed to be cloud,

none searched for ferns

or the tambourine’s yellow circuit.

When the moon sails out

pulleys will turn to trouble the sky;

a boundary of needles will fence in memory

and coffins will carry off those who don’t work.

New York of mud,

New York of wire and death.

What angel lies hidden in your cheek?

What perfect voice will speak the truth of wheat?

Who the terrible dream of your stained anemones?

View of South Street, from Maiden Lane, New York City (ca. 1827)

William James Bennett (English, 1787−1844)

Artvee

Not for a single moment, Walt Whitman, lovely old man,

have I ceased to see your beard filled with butterflies,

nor your corduroy shoulders frayed by the moon,

nor your thighs of virgin Apollo,

nor your voice like a column of ash;

ancient beautiful as the mist,