Virgil

Georgics: Book IV

Bee-Keeping (Apiculture)

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- BkIV:1-7 Introduction

- BkIV:8-66 Location and Maintenance of the Apiary

- BkIV:67-102 The Fighting Swarms

- BkIV:103-148 The Surrounding Garden

- BkIV:149-227 The Nature and Qualities of Bees

- BkIV:228-250 Gathering The Honey

- BkIV:251-280 Disease in Bees

- BkIV:281-314 Autogenesis of Bees

- BkIV:315-386 Aristaeus And His Mother Cyrene

- BkIV:387-452 The Capture of Proteus

- BkIV:453-527 Orpheus and Eurydice

- BkIV:528-558 Aristaeus Sacrifices to Orpheus

- BkIV:559-566 Virgil’s Envoi

BkIV:1-7 Introduction

Next I’ll speak about the celestial gift of honey from the air

Next I’ll speak about the celestial gift of honey from the air.

Maecenas, give this section too your regard.

I’ll tell you in proper sequence about the greatest spectacle

of the slightest things, and of brave generals,

and a whole nation’s customs and efforts, tribes and battles.

Labour, over little: but no little glory, if favourable powers

allow, and Apollo listens to my prayer.

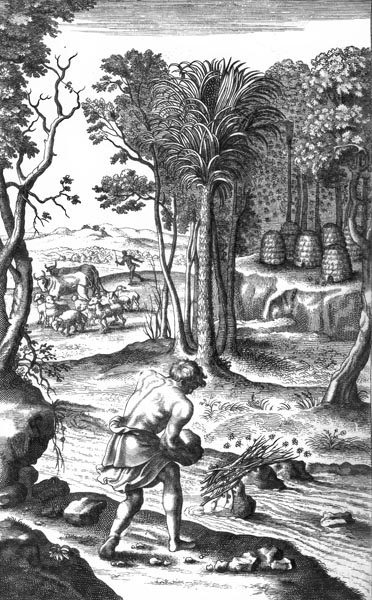

BkIV:8-66 Location and Maintenance of the Apiary

First look for a site and position for your apiary,

where no wind can enter (since the winds prevent them

carrying home their food) and where no sheep or butting kids

leap about among the flowers, or wandering cattle brush

the dew from the field, and wear away the growing grass.

Let the bright-coloured lizard with scaly back, and the bee-eater

and other birds, and Procne, her breast marked

by her blood-stained hands, keep away from the rich hives:

since they all lay waste on every side, and while the bees are flying,

take them in their beaks, a sweet titbit for their pitiless chicks.

But let there be clear springs nearby, and pools green with moss,

and a little stream sliding through the grass,

and let a palm tree or a large wild-olive shade the entrance,

so that when the new leaders command the early swarms

in their springtime, and the young enjoy freedom from the combs,

a neighbouring bank may tempt them to leave the heat,

and a tree in the way hold them in its sheltering leaves.

Whether the water flows or remains still, throw willows

across the centre, and large stones, so that it’s full

of bridges where they can rest, and spread their wings

to the summer sun, if by chance a swift Easterly

has wet the lingerers or dipped them in the stream.

Let green rosemary, and wild thyme with far-flung fragrance,

and a wealth of strongly-scented savory, flower around them,

and let beds of violets drink from the trickling spring.

Let the hives themselves have narrow entrances,

whether they’re seamed from hollow bark,

or woven from pliant osiers: since winter congeals

the honey with cold, and heat loosens it with melting.

Either problem’s equally to be feared with bees:

it’s not for nothing that they emulate each other in lining

the thin cells of their hives with wax, and filling the crevices

with glue made from the flowers, and keep a store of it

for this use, stickier than bird lime or pitch from Phrygian Ida.

If rumour’s true they also like homes in tunnelled hiding-places

underground, and are often found deep in the hollows

of pumice, and the caverns of decaying trees.

You keep them warm too, with clay smoothed by your fingers

round their cracked hives, and a few leaves on top.

Don’t let yew too near their homes, or roast

blushing crabs on your hearth, or trust a deep marsh

or where there’s a strong smell of mud, or where hollow rock

rings when struck, and an echoed voice rebounds on impact.

As for the rest, when the golden sun has driven winter

under the earth, and unlocked the heavens with summer light,

from the first they wander through glades and forests,

grazing the bright flowers, and sipping the surface of the streams.

With this, with a delightful sweetness, they cherish their hive

and young: with it, with art, they form

fresh wax and produce their sticky honey.

So, when you look up at the swarm released from the hive,

floating towards the radiant sky through the clear summer air,

and marvel at the dark cloud drawn along by the wind,

take note: they are continually searching for sweet waters

and leafy canopies. Scatter the scents I demanded,

Look up at the swarm released from the hive

bruised balm and corn parsley’s humble herb, and make

a tinkling sound, and shake Cybele’s cymbals around:

they’ll settle themselves on the soporific rest sites:

they’ll bury themselves, as they do, in their deepest cradle.

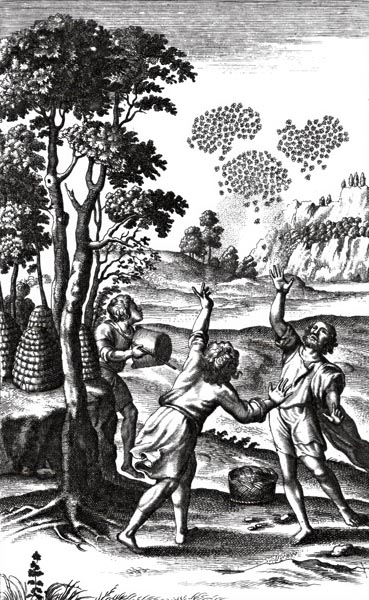

BkIV:67-102 The Fighting Swarms

But if on the other hand they’ve gone out to fight –

because often discord, with great turmoil, seizes two leaders:

and immediately you may know in advance the will of the masses

and, from far off, how their hearts are stirred by war:

since the martial sound of the harsh brass rebukes the lingerers,

and an intermittent noise is heard, like a trumpet blast –

then they gather together restlessly, and their wings quiver,

and they sharpen their stings with their mouths, and flex their legs.

And they swarm round their leader, and the high command,

in crowds, and call out to the enemy with loud cries:

So, when they’ve found a clear spring day, and an open field,

they burst out of the gates: there’s a clash, the noise rises high

in the air, they’re gathered together, mingled in one great ball,

and fall headlong: hail from the sky’s no thicker,

nor is the rain of acorns from a shaken oak-tree.

The leaders themselves in the middle of their ranks,

conspicuous by their wings, have great hearts in tiny breasts,

determined not to give way until the victor’s might has forced

these here, or those there, to turn their backs in flight.

The tossing of a little dust restrains and calms

these fits of passion and these mighty battles.

When you’ve recalled both generals from the fight,

give death to the one that appears weaker, to avoid waste:

and let the stronger one hold power alone.

That one will shine with rough blotches of gold,

since there are two kinds: the better is distinguished in looks,

and bright with reddish armour: the other’s shaggy from sloth,

and ingloriously drags a swollen belly.

As the features of the leaders are twofold, so their subjects’ bodies.

Since some are ugly and bristling, like a parched traveller who

comes out of the deep dust, and spits the dirt from his dry mouth:

others gleam and sparkle with brightness, their bodies

glowing and specked with regular drops of gold.

These are the stronger offspring: in heaven’s due season,

you’ll take sweet honey from these, and no sweeter than it is clear,

and needed to tame the strong flavour of wine.

BkIV:103-148 The Surrounding Garden

But when the swarms fly aimlessly, and swirl in the air,

neglecting their cells, and leaving the hive cold,

you should prevent their wandering spirits from idle play.

It’s no great effort to stop them: tear the wings

from the leaders: while they linger no one will dare

to fly high or take the standards from the camp.

Let gardens fragrant with saffron flowers tempt them,

and let watchful Priapus, lord of the Hellespont, the guard

against thieves and birds, protect them with his willow hook.

He whose concerns are these, let him bring thyme and wild-bay,

himself, from the high hills, and plant them widely round his house:

let him toughen his hands himself with hard labour, let him set

fruitful plants in the ground himself, and sprinkle kind showers.

And for my part, if I were not at the furthest end of my toil,

furling my sails, and hurrying to turn my prow towards shore,

perhaps I too would be singing how careful cultivation ornaments

rich gardens, and of the twice-flowering rose-beds of Paestum,

how the endive delights in the streams it drinks,

and the green banks in parsley, and how the gourd, twisting

over the ground, swells its belly: nor would I be silent about

the late-flowering narcissi, or the curling stem of acanthus,

the pale ivy, and the myrtle that loves the shore.

Since I recall how I saw an old Corycian, under Tarentum’s towers,

where the dark Galaesus waters the yellow fields,

who owned a few acres of abandoned soil,

not fertile enough for bullocks to plough,

not suited to flocks, or fit for the grape harvest:

yet as he planted herbs here and there among the bushes,

and white lilies round them, and vervain, and slender poppies,

it equalled in his opinion the riches of kings, and returning home

late at night it loaded his table with un-bought supplies.

He was the first to gather roses in spring and fruit in autumn:

and when wretched winter was still splitting rocks

with cold, and freezing the water courses with ice,

he was already cutting the sweet hyacinth flowers,

complaining at the slow summer and the late zephyrs.

So was he also first to overflow with young bees,

and a heavy swarm, and collect frothing honey

from the squeezed combs: his limes and wild-bays were the richest,

and as many as the new blossoms that set on his fertile fruit trees

as many were the ones they kept in autumn’s ripeness.

He planted advanced elms in rows as well, hardy pears,

blackthorns bearing sloes, and plane-trees

already offering their shade to drinkers.

But I pass on from this theme, confined within narrow limits,

and leave it for others to speak of after me.

BkIV:149-227 The Nature and Qualities of Bees

Come now and I’ll impart the qualities Jupiter himself

gave bees, for which reward they followed after

the melodious sounds and clashing bronze of the Curetes,

and fed Heaven’s king in the Dictean cave.

They alone hold children in common: own the roofs

of their city as one: and pass their life under the might of the law.

They alone know a country, and a settled home,

and in summer, remembering the winter to come,

undergo labour, storing their gains for all.

For some supervise the gathering of food, and work

in the fields to an agreed rule: some, walled in their homes,

lay the first foundations of the comb, with drops of gum

taken from narcissi, and sticky glue from tree-bark,

then hang the clinging wax: others lead the mature young,

their nation’s hope, others pack purest honey together,

and swell the cells with liquid nectar:

there are those whose lot is to guard the gates,

and in turn they watch out for rain and clouds in the sky,

or accept the incoming loads, or, forming ranks,

they keep the idle crowd of drones away from the hive.

The work glows, and the fragrant honey is sweet with thyme.

And like the Cyclopes when they forge lightning bolts

quickly, from tough ore, and some make the air come and go

with ox-hide bellows, others dip hissing bronze

in the water: Etna groans with the anvils set on her:

and they lift their arms together with great and measured force,

and turn the metal with tenacious tongs:

so, if we may compare small things with great,

an innate love of creation spurs the Attic bees on,

each in its own way. The older ones take care of the hive,

and building the comb, and the cleverly fashioned cells.

But at night the weary young carry back sacs filled with thyme:

they graze far and wide on the blossom of strawberry-trees,

and pale-grey willows, and rosemary and bright saffron,

on rich lime-trees and on purple hyacinths.

All have one rest from work: all have one labour:

they rush from the gates at dawn: no delay: when the evening star

has warned them to leave their grazing in the fields again,

then they seek the hive, then they refresh their bodies:

there’s a buzzing, a hum around the entrances and thresholds.

Then when they’ve settled to rest in their cells, there’s silence

in the night, and sleep seizes their weary limbs.

If rain’s threatening they don’t go far from their hives,

or trust the sky when Easterlies are nearing,

but fetch water from nearby, in the safety of their city wall,

and try brief flights, and often lift little stones,

as unstable ships take up ballast in a choppy sea,

and balance themselves with these in the vaporous clouds.

And you’ll wonder at this habit that pleases the bees,

that they don’t indulge in sexual union, or lazily relax

their bodies in love, or produce young in labour,

but collect their children in their mouths themselves from leaves,

and sweet herbs, provide a new leader and tiny citizens themselves,

and remake their palaces and waxen kingdoms.

Often too as they wander among harsh flints they bruise

their wings, and breathe their lives away beneath their burden.

so great is their love of flowers, and glory in creating honey.

And though the end of a brief life awaits the bees themselves

(since it never extends beyond the seventh summer)

the species remains immortal, and the fortune of the hive

is good for many years, and grandfathers’ grandfathers are counted.

Besides, Egypt and mighty Lydia and the Parthian tribes,

and the Median Hydaspes do not pay such homage to their leader.

With the leader safe all are of the same mind:

if the leader’s lost they break faith, and tear down the honey

they’ve made, themselves, and dissolve the latticed combs.

The leader is the guardian of their labours: to the leader

they do reverence, and all sit round the leader in a noisy throng,

and crowd round in large numbers, and often

they lift the leader on their shoulders and expose their bodies

in war, and, among wounds, seek a glorious death.

Noting these tokens and examples some have said

that a share of divine intelligence is in bees,

and a draught of aether: since there is a god in everything,

earth and the expanse of sea and the sky’s depths:

from this source the flocks and herds, men, and every species

of creature, each derive their little life, at birth:

to it surely all then return, and dissolved, are remade,

and there is no room for death, but still living

they fly to the ranks of the stars, and climb the high heavens.

BkIV:228-250 Gathering The Honey

Whenever you would unseal their noble home, and the honey

they keep in store, first bathe the entrance, moistening it

with a draught of water, and follow it with smoke held out

in your hand. Their anger knows no bounds, and when hurt

they suck venom into their stings, and leave their hidden lances

fixed in the vein, laying down their lives in the wound they make.

Twice men gather the rich produce: there are two seasons

for harvest, as soon as Taygete the Pleiad has shown

her lovely face to Earth and spurned the Ocean stream

with scornful foot, and when that same star fleeing watery Pisces

sinks more sadly from the sky into the wintry waves.

But if you fear a harsh winter, and would spare their future,

and pity their bruised spirits, and shattered fortunes,

who would then hesitate to fumigate them with thyme

and cut away the empty wax? For often a newt has nibbled

the combs unseen, cockroaches, light-averse, fill the cells,

and the useless drone sits down to another’s food:

or the fierce hornet has attacked with unequal weapons,

or the dread race of moths, or the spider, hated by Minerva,

hangs her loose webs in the entrances.

The more is taken, the more eagerly they devote themselves

to repairing the damage to their troubled species,

and filling the cells, and building their stores from flowers.

BkIV:251-280 Disease in Bees

Since life has brought the same misfortunes to bees as ourselves,

if their bodies are weakened with wretched disease,

you can recognise it straight away by clear signs:

as they sicken their colour immediately changes: a rough

leanness mars their appearance: then they carry outdoors

the bodies of those without life, and lead the sad funeral procession:

or else they hang from the threshold linked by their feet, or linger

indoors, all listless with hunger and dull with depressing cold.

Then a deeper sound is heard, a drawn out murmur,

as the cold Southerly sighs in the woods sometimes,

as the troubled sea hisses on an ebb tide,

as the rapacious fire whistles in a sealed furnace.

Then I’d urge you to burn fragrant resin, right away,

and give them honey through reed pipes, freely calling them

and exhorting the weary insects to eat their familiar food.

It’s good too to blend a taste of pounded oak-apples

with dry rose petals, or rich new wine boiled down

over a strong flame, or dried grapes from Psithian vines,

with Attic thyme and strong-smelling centaury.

There’s a meadow flower also, the Italian starwort,

that farmers call amellus, easy for searchers to find:

since it lifts a large cluster of stems from a single root,

yellow-centred, but in the wealth of surrounding petals

there’s a purple gleam in the dark blue: often the gods’ altars

have been decorated with it in woven garlands:

its flavour is bitter to taste: the shepherd’s collect it

in valleys that are grazed, and by Mella’s winding streams.

Boil the plant’s roots in fragrant wine, and place it

as food at their entrances in full wicker baskets.

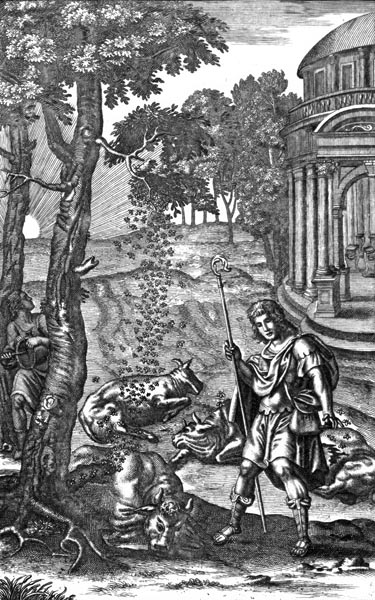

BkIV:281-314 Autogenesis of Bees

But if someone’s whole brood has suddenly failed,

and he has no stock from which to recreate a new line,

then it’s time to reveal the famous invention of Aristaeus,

the Arcadian master, and the method by which in the past

the adulterated blood of dead bullocks has generated bees.

I will tell the whole story in depth, tracing it from its first origins.

Where the fortunate peoples of Pellaean Canopus live

by the overflowing waters of the flooded Nile,

and sail around their fields in painted boats,

where the closeness of the Persian bowmen oppresses them,

and where the river’s flow splits, in seven distinct mouths,

enriching green Egypt with its black silt,

the river that has flowed down from the dark Ethiopians,

all in that country depend on this sure stratagem.

First they choose a narrow place, small enough for this purpose:

they enclose it with a confined roof of tiles, walls close together,

and add four slanting window lights facing the four winds.

Then they search out a bullock, just jutting his horns out

of a two year olds forehead: the breath from both its nostrils

and its mouth is stifled despite its struggles: it’s beaten to death,

and its flesh pounded to a pulp through the intact hide.

They leave it lying like this in prison, and strew broken branches

under its flanks, thyme and fresh rosemary.

This is done when the Westerlies begin to stir the waves

before the meadows brighten with their new colours,

before the twittering swallow hangs her nest from the eaves.

Meanwhile the moisture, warming in the softened bone, ferments,

and creatures, of a type marvellous to see, swarm together,

without feet at first, but soon with whirring wings as well,

and more and more try the clear air, until they burst out,

like rain pouring from summer clouds,

or arrows from the twanging bows,

whenever the lightly-armed Parthians first join battle.

BkIV:315-386 Aristaeus And His Mother Cyrene

Muses, what god produced this art for us?

How did this new practice of men begin?

Aristaeus the shepherd, so the tale goes, having lost his bees,

through disease and hunger, leaving Tempe along the River Peneus,

stopped sadly by the stream’s sacred source,

and called to his mother, with many groans, saying:

‘O mother, Cyrene, you who live here in the stream’s depths,

why did you bear me, of a god’s noble line,

(if Thymbrean Apollo’s my father, indeed, as you say)

to be hated by fate? Or why is your love taken from me?

Why did you tell me to set my hopes on the heavens?

See how, though you are my mother, I even relinquish

this glory of mortal life itself, that skilful care

for the crops and herds hardly achieved for all my efforts.

Come and tear down my fruitful trees, with your own hands,

set destructive fire to my stalls, and destroy my harvest,

burn my seed, and set the tough axe to my vines,

if such loathing for my honour has seized you.’

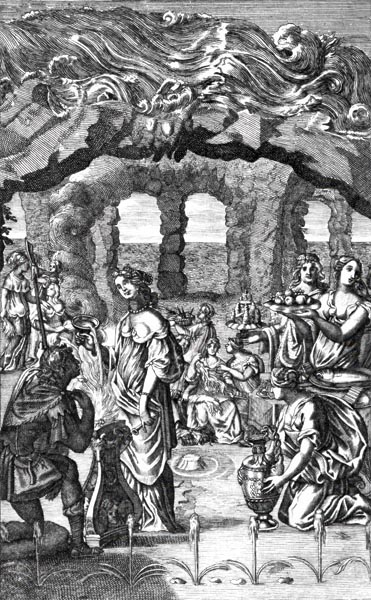

But his mother felt the cry from her chamber in the river’s depths,

Around her the Nymphs were carding fleeces

from Miletus, dyed with deep glassy colours:

Drymo and Xantho, Phyllodoce, Ligea,

their bright hair flowing over their snowy necks,

Cydippe and golden-haired Lycorias, one a virgin,

the other having known the pangs of first childbirth,

Clio and her sister Beroe, both daughters of Ocean,

both ornamented with gold, clothed in dappled skins:

Ephyre and Opis, and Asian Deiopea,

and swift Arethusa, her arrows at last set aside.

Among them Clymene was telling of Vulcan’s

baffled watch, and Mars’s tricks and stolen sweetness,

and recounting the endless loves of the gods, from Chaos on.

And while they unwound the soft thread from the spindles,

captivated by the song, Aristaeus’s cry again struck

his mother’s ear, and all were startled, sitting on their crystal seats:

But Arethusa, before all her other sisters, lifted her golden hair

above the wave’s surface and, looking out, called from far off:

‘O Cyrene, sister, your fear at such loud groaning is not idle,

it is your own Aristaeus, your chief care, standing weeping

by the waters of father Peneus, calling, and naming you as cruel.’

His mother, her heart trembling with fresh fear, calls to her:

Bring him, bring him to me: it’s lawful for him to touch

the divine threshold’: at that she ordered the river to split apart

so the youth could enter. And the wave arched above him like a hill

and, receiving him in its vast folds, carried him below the stream.

Now, marvelling at his mother’s home, and the watery regions,

at the lakes enclosed by caves, and the echoing glades,

he passed along, and, dazed by the great rushing of water,

gazed at all the rivers as, each in its separate course, they slide

beneath the mighty earth, Phasis and Lycus

and the source from which deep Enipeus first rises,

the source of father Tiber, and that of Anio’s streams,

and rock-filled sounding Hypanis, and Mysian Caicus,

and Eridanus, with twin golden horns on his forehead,

than whom no more forceful river flows

through the rich fields to the dark blue sea.

As soon as he had reached her chamber, with its roof

of hanging stone, and Cyrene knew of her son’s useless tears,

the sisters bathed his hands with spring water, and, in turn,

brought him smooth towels: some of them set a banquet

on the tables and placed brimming cups: the altars

blazed with incense-bearing flames. Then his mother said:

‘Take the cup of Maeonian wine: let us pour

a libation to Ocean.’ And with that she prayed

to Ocean, the father of things, and her sister Nymphs

who tend a hundred forests, a hundred streams.

As soon as he had reached her chamber, with its roof of hanging stone

Three times she sprinkled the glowing hearth with nectar,

three times the flame flared, shooting towards the roof.

With this omen to strengthen his spirit, she herself began:

BkIV:387-452 The Capture of Proteus

‘A seer, Proteus, lives in Neptune’s Carpathian waters,

who, sea-green, travels the vast ocean in a chariot

drawn by fishes and two-footed horses.

Even now he’s revisiting the harbours of Thessaly,

and his native Pallene. We nymphs venerate him,

and aged Nereus himself: since the seer knows all things,

what is, what has been, what is soon about to be:

since it’s seen by Neptune, whose monstrous sea-cows

and ugly seals he grazes in the deep.

You must first capture and chain him, my son, so that he

might explain the cause of the disease, and favour the outcome.

For he’ll give you no wisdom unless you use force, nor will you

make him relent by prayer: capture him with brute force and chains:

only with these around him will his tricks fail uselessly.

When the sun has gathered his midday heat, when the grass thirsts,

and the shade’s welcome now to the flock, I’ll guide you myself

to the old man’s hiding place, where he retreats from the waves

when he’s weary, so you can easily approach him when he’s asleep.

When you seize him in your grip, with chains and hands,

then varied forms, and the masks of wild beasts, will baffle you.

When you seize him in your grip, with chains and hands

Suddenly he’ll become a bristling boar, a malicious tiger,

a scaly serpent, or a lioness with tawny mane,

or he’ll give out the fierce roar of flames, and so slip his bonds,

or he’ll dissolve into tenuous water, and be gone.

But the more he changes himself into every form,

the more you, my son, tighten the stubborn chains,

until, having altered his shape, he becomes such as you saw

when he closed his eyes at the start of his sleep.

She spoke, and spread about him liquid perfume of ambrosia,

with which she drenched her son’s whole body:

and a sweet fragrance breathed from his ordered hair,

and strength entered his supple limbs. There’s a vast cave

carved in a mountain side, from which many a wave

is driven by the wind, and separates into secluded bays,

safest of harbours at times for unwary sailors:

Proteus hides himself in there behind a huge barrier of rock.

Here the Nymph placed the youth, hidden from the light,

she herself stood far off, veiled in mist.

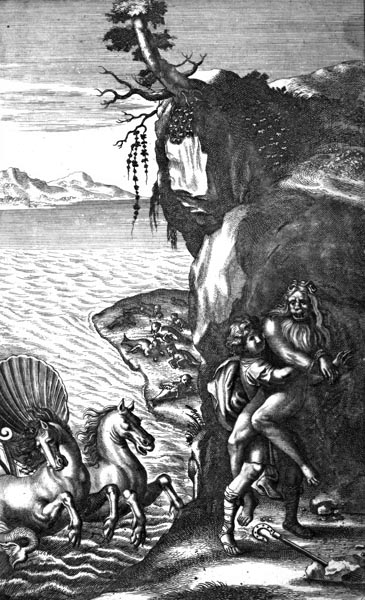

Now the Dog Star blazed in the sky, fiercely parching

the thirsty Indians, and the fiery sun had consumed

half his course: the grass withered, and deep rivers were heated

and baked, by the rays at their parched sources, down to the mud,

when Proteus came from the sea, to find his customary cave.

Round him the moist race of the vast sea frolicked,

scattering the salt spray far and wide.

The seals lay down to sleep here and there on the shore:

he himself sat on the rock in the middle, as the guardian

of a sheepfold on the hills sometimes sits, when Vesper brings

the calves home from pasture, and the bleating of lambs rouses

the wolf, hearing them, and the shepherd counts his flock.

As soon as chance offered itself, Aristaeus,

hardly allowed the old man to settle his weary limbs

before he rushed on him, with a great shout, and fettered him

as he lay there. The seer does not forget his magic arts,

but transforms himself into every marvellous thing,

fire, and hideous creature, and flowing river.

but when no trickery achieves escape, he returns

to his own shape, beaten, and speaks at last with human voice:

‘Now who has told you to invade my home, boldest of youths?

What do you look for here?’ he said, but Aristaeus replied:

‘You know, yourself, Proteus, you know: you are deceived

by nothing: but let yourself cease. Following divine counsel,

I come to seek the oracle here regarding my weary tale.’

So he spoke. At that the seer, twisting in his grip, eyes blazing

with grey-green light, and grimly gnashing his teeth,

opened his lips at last, and spoke this fate:

BkIV:453-527 Orpheus and Eurydice

‘Not for nothing does divine anger harass you:

you atone for a heavy crime: it is Orpheus, wretched man,

who brings this punishment on you, no less than you deserve

if the fates did not oppose it: he raves madly for his lost wife.

She, doomed girl, running headlong along the stream,

so as to escape you, did not see the fierce snake, that kept

to the riverbank, in the deep grass under her feet.

But her crowd of Dryad friends filled the mountaintops

with their cry: the towers of Rhodope wept, and the heights

of Pangaea, and Thrace, the warlike land of Rhesus,

and the Getae, the Hebrus, and Orythia, Acte’s child.

Orpheus, consoling love’s anguish, with his hollow lyre,

sang of you, sweet wife, you, alone on the empty shore,

of you as day neared, of you as day departed.

He even entered the jaws of Taenarus, the high gates

of Dis, and the grove dim with dark fear,

and came to the spirits, and their dread king, and hearts

that do not know how to soften at human prayer.

The insubstantial shadows, and the phantoms of those without light,

came from the lowest depths of Erebus, startled by his song,

as many as the thousand birds that hide among the leaves,

when Vesper, or wintry rain, drives them from the hills,

mothers and husbands, and the bodies of noble heroes

bereft of life, boys and unmarried girls, and young men

placed on the pyre before their father’s eyes:

round them are the black mud and foul reeds

of Cocytus, the vile marsh, holding them with its sluggish waters,

and Styx, confining them in its nine-fold ditches.

The House of the Dead itself was stupefied, and innermost

Tartarus, and the Furies, with dark snakes twined in their hair,

and Cerberus held his three mouths gaping wide,

and the whirling of Ixion’s wheel stopped in the wind.

And now, retracing his steps, he evaded all mischance,

and Eurydice, regained, approached the upper air,

she following behind (since Proserpine had ordained it),

when a sudden madness seized the incautious lover,

one to be forgiven, if the spirits knew how to forgive:

he stopped, and forgetful, alas, on the edge of light,

his will conquered, he looked back, now, at his Eurydice.

In that instant, all his effort was wasted, and his pact

with the cruel tyrant was broken, and three times a crash

was heard by the waters of Avernus. ‘Orpheus,’ she cried,

‘what madness has destroyed my wretched self, and you?

See, the cruel Fates recall me, and sleep hides my swimming eyes,

Farewell, now: I am taken, wrapped round by vast night,

stretching out to you, alas, hands no longer yours.’

She spoke, and suddenly fled, far from his eyes,

like smoke vanishing in thin air, and never saw him more,

though he grasped in vain at shadows, and longed

to speak further: nor did Charon, the ferryman of Orcus,

let him cross the barrier of that marsh again.

What could he do? Where could he turn, twice robbed of his wife?

With what tears could he move the spirits, with what voice

move their powers? Cold now, she floated in the Stygian boat.

They say he wept for seven whole months,

beneath an airy cliff, by the waters of desolate Strymon,

and told his tale, in the icy caves, softening the tigers’ mood,

and gathering the oak-trees to his song:

as the nightingale grieving in the poplar’s shadows

laments the loss of her chicks, that a rough ploughman saw

snatching them, featherless, from the nest:

but she weeps all night, and repeats her sad song perched

among the branches, filling the place around with mournful cries.

No love, no wedding-song could move Orpheus’s heart.

He wandered the Northern ice, and snowy Tanais,

and the fields that are never free of Rhipaean frost,

mourning his lost Eurydice, and Dis’s vain gift:

the Ciconian women, spurned by his devotion,

tore the youth apart, in their divine rites and midnight

Bacchic revels, and scattered him over the fields.

Even then, when Oeagrian Hebros rolled the head onwards,

torn from its marble neck, carrying it mid-stream,

the voice alone, the ice-cold tongue, with ebbing breath,

cried out: ‘Eurydice, ah poor Eurydice!’

‘Eurydice’ the riverbanks echoed, all along the stream.

BkIV:528-558 Aristaeus Sacrifices to Orpheus

So Proteus spoke, and gave a leap into the deep sea,

and where he leapt the waves whirled with foam, under the vortex.

But not Cyrene: speaking unasked to the startled youth:

‘Son, set aside these sad sorrows from your mind.

This is the cause of the whole disease, because of it the Nymphs,

with whom that poor girl danced in the deep groves,

sent ruin to your bees. Offer the gifts of a suppliant,

asking grace, and worship the gentle girls of the woods,

since they’ll grant forgiveness to prayer, and abate their anger.

But first I’ll tell you in order the method of worship.

Choose four bulls of outstanding physique,

that graze on your summits of green Lycaeus,

and as many heifers, with necks free of the yoke.

Set up four altars for them by the high shrines of the goddesses,

and drain the sacred blood from their throats

leaving the bodies of the steers in the leafy grove.

Drain the sacred blood from their throats, leaving the bodies of the steers in the leafy grove

Then when the ninth dawn shows her light

send funeral gifts of Lethean poppies to Orpheus,

and sacrifice a black ewe, and revisit the grove:

worship Eurydice, placate her with the death of a calf.’

Without delay he immediately does as his mother ordered:

he comes to the shrines, raises the altars as required,

and leads four chosen bulls there of outstanding physique,

and as many heifers with necks free of the yoke.

Then when the ninth dawn brings her light,

he sends funeral gifts to Orpheus, and revisits the grove.

Here a sudden wonder appears, marvellous to tell,

bees buzzing and swarming from the broken flanks

among the liquefied flesh of the cattle,

and trailing along in vast clouds, and flowing together

on a tree top, and hanging in a cluster from the bowed branches.

BkIV:559-566 Virgil’s Envoi

So I sang, above, of the care of fields, and herds,

and trees besides, while mighty Caesar thundered in battle,

by the wide Euphrates, and gave a victor’s laws

to willing nations, and took the path towards the heavens.

Then was I, Virgil, nursed by sweet Parthenope,

joyous in the pursuits of obscure retirement,

I who toyed with shepherds’ songs, and, in youth’s boldness,

sang of you, Tityrus, in the spreading beech-tree’s shade.

The End of The Georgics