Suetonius: The Twelve Caesars

Book VI: Nero

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2010 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book Six: Nero

- Book Six: I The Domitian Family

- Book Six: II Nero’s Ancestors

- Book Six: III Nero’s Great-Grandfather

- Book Six: IV Nero’s Grandfather

- Book Six: V Nero’s Father

- Book Six: VI Nero’s Birth and Infancy

- Book Six: VII His Boyhood and Youth

- Book Six: VIII His Accession to Power

- Book Six: IX His Display of Filial Piety

- Book Six: X His Initial Benevolent Intentions

- Book Six: XI Chariot Races and Theatricals

- Book Six: XII Shows and Contests

- Book Six: XIV His First Four Consulships

- Book Six: XV His Administration of Affairs

- Book Six: XVI His Public Works and Legislation

- Book Six: XVII Actions to Combat Forgery and Corruption

- Book Six: XVIII His Lack of Imperial Ambition

- Book Six: XIX His Planned Foreign Tours and Expedition

- Book Six: XX His Musical Education and Debut in Naples

- Book Six: XXI His Debut in Rome

- Book Six: XXII Chariot-Racing and the Trip to Greece

- Book Six: XXIII His Anxiety When Competing

- Book Six: XXIV His Behaviour in Competition

- Book Six: XXV Return from Greece

- Book Six: XXVI His Evil Nature

- Book Six: XXVII His Increasing Wickedness

- Book Six: XXVIII His Sexual Debauchery

- Book Six: XXIX His Erotic Practices

- Book Six: XXX His Extravagance

- Book Six: XXXI Public Works and the Golden House

- Book Six: XXXII His Methods of Raising Money

- Book Six: XXXIII His Murder of Claudius and Britannicus

- Book Six: XXXIV His Murder of his Mother and Aunt

- Book Six: XXXV More Family Murders

- Book Six: XXXVI The Pisonian Conspiracy

- Book Six: XXXVII Indiscriminate Persecution

- Book Six: XXXVIII The Great Fire of Rome

- Book Six: XXXIX Disasters and Abuse

- Book Six: XL Uprising in Gaul

- Book Six: XLI Continuing Rebellion

- Book Six: XLII Galba’s Insurrection

- Book Six: XLIII Nero’s Reaction to the Gallic Rebellion

- Book Six: XLIV His Preparations for a Campaign

- Book Six: XLV Popular Resentment

- Book Six: XLVI Dreams and Omens

- Book Six: XLVII Preparations for Flight

- Book Six: XLVIII A Last Hiding-Place

- Book Six: XLIX His Death

- Book Six: L His Funeral

- Book Six: LI His Appearance, Health and Mode of Dress

- Book Six: LII His Knowledge of the Arts

- Book Six: LIII His Desire for Popularity

- Book Six: LIV His Last Vow to Perform as Actor and Musician

- Book Six: LV His Desire for Fame and Immortality

- Book Six: LVI His Superstitious Beliefs

- Book Six: LVII Conflicting Emotions after his Death

Book Six: Nero

Book Six: I The Domitian Family

Of the Domitian family, two branches acquired distinction, namely the Calvini and the Ahenobarbi. The founder of the Ahenobarbi, who first bore their surname, was Lucius Domitius, who was returning from the country one day, so they say, when a pair of youthful godlike twins appeared and told him to carry tidings of victory (at Lake Regillus, c498BC) to Rome, news that would be welcome in the City. As a sign of their divinity, they are said to have stroked his face and turned his beard from black to the colour of reddish bronze. This sign was inherited by his male descendants, the majority of whom had red beards.

Attaining seven consulships, a triumph and two censorships, and enrolment among the patricians, they continued to employ the same surname, while restricting their forenames to Gnaeus and Lucius, use of which they varied in a particular manner, sometimes conferring the same forename on three members of the family in succession, sometimes varying them in turn. So, we are told that the first three Ahenobarbi were named Lucius, the next three Gnaeus, while those that followed were named Lucius and Gnaeus alternately.

I think it useful to give an account of several notable members of the family, to illustrate more clearly that Nero perpetuated their separate vices, as if these were inborn and bequeathed to him, while failing to exhibit their virtues.

Book Six: II Nero’s Ancestors

So, beginning quite far back, Gnaeus Domitius, Nero’s great-great-great-grandfather, when tribune of the commons (in 104BC) was angered with the College of Priests and transferred the right to fill vacancies to the people, after the College failed to appoint him as successor to his father, also named Gnaeus. His father it was who during his consulship (in 122BC) had defeated the Allobroges and the Arverni, and ridden through the province on an elephant, surrounded by his troops, in a kind of triumphal procession. The orator Licinius Crassus said of the son that his bronze beard was hardly surprising considering that he had a face of iron and a heart of lead.

His son in turn, Nero’s great-great-grandfather, Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus while praetor (in 58BC), summoned Julius Caesar before the Senate at the close of his consulship on suspicion that the auspices and laws had been defied under his administration. Later in his own consulship (54BC) he tried to remove Caesar from his command of the troops in Gaul, and was named successor to Caesar by his own party. At the beginning of the Civil War he was taken prisoner at Corfinium (in 49BC). Given his freedom, he heartened the people of Massilia (Marseille), who were under heavy siege, by his presence, but abruptly abandoned them, falling a year later at Pharsalus. Lucius was irresolute, but with a violent temper. He once tried to poison himself in a fit of despair, but was terrified by the thought of death and vomited the dose, which his physician, knowing his master’s disposition, had ensured was not fatal. Lucius gave the man his freedom as a reward. When Pompey raised the question of how neutrals should be treated, Lucius was alone in classifying those who had sided with neither party as enemies.

Book Six: III Nero’s Great-Grandfather

Lucius left a son Gnaeus, who was without question the best of the family. Though not one of Caesar’s assassins, he was implicated in the conspiracy and condemned to death under the Pedian Law (in 43BC). He therefore fled to join Brutus and Cassius, his close relatives. After the death of the two leaders, he kept command of the fleet and augmented it, only surrendering it to Mark Antony after the rest of his party had been routed, and then of his own free will as if conferring a favour. He was the only person condemned under the Pedian Law who was allowed to return home, successively holding the highest offices.

When the Civil War was renewed (in 32BC), he was appointed one of Antony’s commanders, and offered the supreme command by those who found Cleopatra an embarrassment, but a sudden illness inhibited him from accepting it, though he never positively refused. He transferred his allegiance to Augustus, but died a few days later (31BC). His reputation was tarnished further by Antony’s declaration that Gnaeus had only changed sides to be with his mistress, Servilia Nais.

Book Six: IV Nero’s Grandfather

Gnaeus was the father of that Lucius Domitius who later became well-known as Augustus’s executor, and was named in his will as the (symbolic) purchaser of his household goods and other assets. He was equally famous in his youth as a charioteer and later for winning triumphal insignia in the German campaign. However he was arrogant, extravagant and cruel.

When he was only an aedile, he ordered Munatius Plancus the Censor (in 22BC) to make way for him in the street. While holding the offices of praetor and consul (in 16BC) he encouraged Roman knights and married women to act in a farce on stage. The inhuman cruelty exhibited in the bear-baiting shows he staged, both in the Circus and all over the City, and in a gladiatorial show he mounted, led to a private warning from Augustus which was disregarded, and ultimately therefore a restraining order against him.

Book Six: V Nero’s Father

Lucius had a son Gnaeus Domitius by Antonia the Elder. This was Nero’s father, a detestable man in every way.

When he served in the East under the young Gaius Caesar (in 1BC), he murdered one of his own freedmen simply for refusing to drink as much as he was ordered. Dismissed in consequence from Gaius’s staff, he lived no less lawlessly. For example, while driving through a village on the Appian Way he deliberately whipped up his team, ran over a boy, and killed him. And in the Forum he gouged a Roman knight’s eye out because he criticised him too freely.

He was dishonest too. He not only cheated some financiers over payment for goods he had purchased, but during his praetorship he defrauded the victorious charioteers of their prizes. When his elder sister Domitia made this a subject for scornful mockery of him, and the managers of the chariot teams complained, he issued an (ironic) edict declaring that in future the value of prizes should be paid on the spot.

Shortly before Tiberius died, Domitius was charged with treason, adultery and incest with his younger sister Lepida, but was saved by the transfer of power. He died of oedema at Pyrgi (in 40AD), after formally acknowledging his paternity of Nero, his son by Germanicus’s daughter Agrippina the Younger.

Book Six: VI Nero’s Birth and Infancy

Nero was born nine months after the death of Tiberius, at Antium, at sunrise on the 15th of December AD37. The sun’s rays therefore touched the child even before he could be set on the ground.

His horoscope occasioned many ominous predictions, and a remembered comment of his father’s was also regarded as a prophecy. Domitius had said that nothing born of Agrippina and himself could be anything but detestable and a public evil. Another clear indication of future misfortune occurred on the day of Nero’s purification ceremony. When Caligula was asked by his sister to name the child, he glanced at his uncle Claudius, emperor to be, and in due course Nero’s adoptive father, and said, as a joke, that Claudius was the name he chose. Agrippina scornfully rejected the proposal, Claudius being at that time the butt of the whole Court.

When he was three his father died (in 40AD), leaving him a third of his estate, though he failed to receive this, because Caligula his co-heir seized the whole. His mother was banished, and Nero was raised in his aunt Lepida’s house, and subject to a degree of personal deprivation, his tutors being a dancer and a barber! But on Claudius becoming Emperor (in AD41), Nero not only found his inheritance restored, but also received a bequest from his stepfather, Passienus Crispus.

Now that his mother had been recalled from banishment and reinstated, Nero acquired such prominence due to her influence that it later transpired that Messalina, Claudius’s wife, viewing him as a rival to Britannicus, had despatched her agents to strangle him while he was taking a midday nap. An elaboration of this piece of gossip is that the would-be assassins were only deterred by a snake which darted from under his pillow. The sole foundation for this tale was simply a snake’s sloughed skin found in his bed near the pillow, nevertheless at his mother’s prompting he had the skin encased in a gold bracelet, which he wore for a long time on his right arm. Later when everything reminding him of his mother was hateful to him, he threw it away, only to search for it in vain at the end.

Book Six: VII His Boyhood and Youth

While he was still a young stripling he took part in a successful performance of the Troy Game in the Circus, in which he exhibited great self-possession. At the age of twelve or so (sometime in AD50), he was adopted by Claudius, who appointed Annaeus Seneca, already a member of the Senate, as his tutor. The following night, it is said, Seneca dreamed that his young charge was really Caligula, and Nero soon proved the dream prophetic by seizing the first opportunity to reveal his cruel disposition. Simply because his adoptive brother, Britannicus, continued to address him as ‘Ahenobarbus’, he tried to convince Claudius that Britannicus was a changeling. And when his aunt Lepida was on trial, he gave public testimony against her to please his mother Agrippina who was doing everything possible to destroy her.

At his first introduction to the populace in the Forum, he announced the distribution of monetary gifts to the people, with cash bonuses for the army, and headed a ceremonial display by the Praetorian Guard, shield in hand, before giving a speech of thanks to Claudius in the Senate. While Claudius was consul (in AD51) Nero presented two pleas before him, the first delivered in Latin on behalf of the citizens of Bononia (Bologna), the second in Greek on behalf of those of Rhodes and Troy.

His first appearance as judge was as City Prefect during the Latin Festival, when the most eminent lawyers brought cases of the greatest significance before him, not just the customary batch of trivial ones, despite the fact that Claudius had explicitly forbidden them to do so.

Shortly afterwards, he married Claudia Octavia (in AD53) and held Games and a wild-beast show in the Circus, dedicating them to the good-health of his new father-in-law Claudius.

Book Six: VIII His Accession to Power

After Claudius’s death (AD54) had been announced publicly, Nero, who was not quite seventeen years old, decided to address the Guards in the late afternoon, since inauspicious omens that day had ruled out an earlier appearance. After being acclaimed Emperor on the Palace steps, he was carried in a litter to the Praetorian Camp where he spoke to the Guards, and then to the House where he stayed until evening. He refused only one of the many honours that were heaped upon him, that of ‘Father of the Country’, and declined that simply on account of his youth.

Book Six: IX His Display of Filial Piety

He began his reign with a display of filial piety, giving Claudius a lavish funeral, speaking the eulogy, and announcing the deceased Emperor’s deification.

He showed the greatest respect for the memory of his natural father Domitius, while leaving the management of all private and public affairs to his mother Agrippina. Indeed on the first day of his reign he gave the Guard’s colonel on duty the password ‘Best of Mothers’, and subsequently he often rode with her through the streets in her litter.

Nero founded a colony at Antium, his birthplace, of Praetorian Guard veterans along with the wealthiest of the leading centurions whom he compelled to relocate, and he also built a harbour there at vast expense.

Book Six: X His Initial Benevolent Intentions

He made his good intentions ever more apparent by announcing that he would rule according to the principles of the Emperor Augustus, and seized every opportunity to show generosity or compassion, and display his affability.

He eased or abolished the more burdensome taxes; reduced by three-quarters the bounty paid to informers for reporting breaches of the Papian law; distributed forty gold pieces to every commoner; granted the most distinguished Senators lacking means an annual stipend, as much as five thousand gold pieces in some cases; and granted the Guards’ cohorts a free monthly allowance of grain.

When asked to sign the customary death-warrant for a prisoner condemned to execution, he commented: ‘How I wish I had never learnt to write!’

He greeted men of all ranks by name, from memory. When the Senate asked him to accept their thanks he replied: ‘When I have deserved them.’

He allowed even commoners to watch his exercises in the Campus, and often declaimed in public, reading his poetry too, not only at home but in the theatre, prompting a public thanksgiving voted to him for his delightful recital, while the text he had given was inscribed in gold letters and dedicated to Capitoline Jupiter.

Book Six: XI Chariot Races and Theatricals

He gave many entertainments of varying kinds, including the Juvenales, or Coming-of-Age celebrations, in which even old men of consular rank and old ladies took part; chariot races in the Circus; theatricals; and a gladiatorial show.

At the Games in the Circus he reserved special seats for the knights, and raced four-camel chariots. A well-known knight rode down a tight-rope while mounted on an elephant.

At the Ludi Maximi, the name he decreed for a series of plays dedicated to ‘The Eternity of Empire’ men and women of both Orders took part. The actors in a play called ‘The Fire’ by Afranius were allowed to keep the furniture they carried from the burning house. Gifts were granted daily to the audience, including a thousand birds of every species on each occasion, various foodstuffs, as well as tokens and vouchers for clothing, gold and silver, gems and pearls, paintings, slaves, beasts of burden, wild animals that had been trained, and even ships, blocks of apartments, and whole farms. Nero watched these plays from the top of the proscenium.

Book Six: XII Shows and Contests

The gladiatorial show was mounted in a wooden amphitheatre, built inside a year, on the Campus Martius (in AD58). None of the participants was put to death, not even the criminals, but four hundred Senators and six hundred knights, some being very wealthy yet of unquestionable virtue, were forced to fight in the arena. And the two Orders also had to participate in the wild beast contests, and perform the necessary tasks in the arena.

He staged a naval battle too, with sea monsters swimming in a lake of saltwater; accompanied by Pyrrhic dances. These were executed by Greek youths to whom he gave certificates of Roman citizenship at the end of their performance. The dances represented mythological scenes. In one Pasiphae, hidden in a heifer made of wood, was mounted by the bull, or at least to many spectators it appeared so. In another, Icarus while attempting flight fell close by the Imperial couch, spattering the Emperor with blood. Nero avoided presiding, but would view the Games, while reclining on this same couch, at first through curtained openings, but later with the entire podium uncovered.

He also started (in AD60) a five-yearly festival in the Greek-style, comprising, that is, performances to music, gymnastics and horse-riding. He called this the Neronia. At the same time he opened his baths and gymnasium, and provided free oil for the knights and Senators. He appointed ex-consuls chosen by lot to judge and preside, who occupied the praetors’ seats.

He received the prize for Latin oratory and verse, himself, which was unanimously awarded to him by all the contestants, comprising the most renowned orators and poets, descending into the orchestra, among the Senators, to accept it. But on being offered the laurel-wreath for lyre-playing by the judges, he bowed before it and ordered it to be laid at the feet of Augustus’s statue.

He held the gymnastics contest in the Enclosure (Saepta), shaving off his first beard while a splendid sacrifice of bullocks was made, and enclosing the shaved-off hair in a gold box adorned with priceless pearls, later dedicating it on the Capitol. He also invited the Vestal Virgins to view the athletic contests since the Priestesses of Demeter-Ceres were granted the same privilege at Olympia.

Book Six: XIII The Entrance of Tiridates

The entrance of Tiridates, King of Armenia, to the City (in AD66) ought rightly to be included in the list of Nero’s spectacular events. The king had been lured to Rome with extravagant promises, while poor weather prevented him being shown to the people on the day proclaimed. However at the first decent opportunity, Nero produced him. The Emperor was seated in a curule chair on the Rostra dressed as a triumphant general, and surrounded by military ensigns and standards, the Forum being filled with Praetorian Guards drawn up in full armour in front of the various temples.

Tiridates approached up a sloping ramp, and Nero allowed him first to fall at his feet, then raised him with his right hand and kissed him. As the king made his supplication, and a translator of praetorian rank proclaimed his words in Latin to the crowd, Nero took the turban from the king’s head and crowned him with a diadem. Tiridates was then led to Pompey’s Theatre, and when he had made further supplication Nero seated him on his right. The people then hailed Nero as ‘Imperator’, and after dedicating a triumphal laurel wreath on the Capitol he had the double doors of the Temple of Janus closed, to signify that the Empire was at peace.

Book Six: XIV His First Four Consulships

Of his first four consulships, the initial one was for two months, the second and fourth for six months each, and the third for four months. The second and third were in successive years (in AD57 and 58), while a year intervened between these and the first and last (in AD55 and 60).

Book Six: XV His Administration of Affairs

In matters of justice, he was reluctant to give his decision on the case presented until the following day, and then in writing. Instead of the prosecution and defence presenting their pleas as a whole, he insisted on each point being separately presented by the two sides in turn. And on withdrawing for consultation, he would not discuss the case with his advisors in a body, but made each of them give his opinion in writing. He read the submissions alone in silence, and then delivered his own verdict as if it were the majority view.

For a long while he excluded the sons of freedmen from the Senate, and refused office to those whom his predecessors had admitted. Candidates for whom there was no vacancy won command of a legion as compensation for the postponement and delay.

He usually appointed consuls for a six-month period. When one died just before New Year, he left the post vacant, commenting with disapproval on the old instance of Caninius Rebilus who was made consul for a day.

He conferred triumphal regalia on men of quaestor rank as well as knights, and occasionally for other than military service. Regarding the speeches he sent to the Senate on various subjects, he usually had them presented by one of the consuls, and not the quaestors whose duty it was to read them.

Book Six: XVI His Public Works and Legislation

Nero introduced a new design for City buildings, with porches added to houses and apartment blocks, from the flat roofs of which fires could be fought. These he had erected at his own cost.

He laid down plans to extend Rome’s walls as far as Ostia, and to excavate a sea-canal from there to the City.

Many abuses were punished severely, or repressed during his reign, under a spate of new laws: limits were set to private expenditure; public banquets were replaced by a simple distribution of food; and the sale of cooked food in wine-shops was limited to vegetables and beans, instead of the wide range of delicacies available previously.

Punishment was meted out to the Christians (from AD64), a group of individuals given over to a new and harmful set of superstitions.

Nero ended the licence which the charioteers had enjoyed, ranging the streets and amusing themselves by robbing and swindling the populace, while claiming a long-standing right to immunity. He also expelled the pantomime actors and their like from the City.

Book Six: XVII Actions to Combat Forgery and Corruption

During his reign various measures to combat forgery were first devised. Signed tablets had to have holes bored in them, and were thrice threaded with a cord (and sealed, concealing an inner copy). In the case of wills, the first two leaves were to be signed by the witnesses while still displaying no more than the testator’s name, and no one writing a will was allowed to include himself among the legatees.

Clients were again allowed to pay lawyers a fixed but reasonable fee for their services, but seats in court were to be provided free of charge by the public Treasury.

And as regards pleas, those to do with the Treasury were to be heard by an arbitration board in the Forum, with any appeal against the verdict to be made to the Senate.

Book Six: XVIII His Lack of Imperial Ambition

Far from being driven by any desire or expectation of increasing and extending the Empire, he even considered withdrawing the army from Britain, and changed his mind only because he was ashamed of appearing to belittle his adoptive father Claudius’s achievement.

He only added the realm of Pontus to the list of provinces, on the abdication of Polemon II (in AD62) and that of Cottius II in the Alps when that chieftain died.

Book Six: XIX His Planned Foreign Tours and Expedition

Nero planned two foreign trips.

His trip to Alexandria he abandoned on the day he was due to set out, as the result of a threatening portent. While making a farewell round of the temples, he seated himself in the Temple of Vesta, but on attempting to leave his robe was caught, and then his eyes were filled with darkness so that he could not see.

His trip to Greece (in 67AD) involved an attempt to cut a canal through the Isthmus. The Guards were summoned and instructed to begin work after a trumpet call was sounded, at which he would break the ground with a mattock, and carry off the first basketful of soil on his shoulders.

He also prepared an expedition to the Caspian Gates, enrolling a new legion of Italian-born recruits, all nearly six foot tall, whom he called ‘The Phalanx of Alexander the Great’.

I have compiled this description of Nero’s actions, some of which merit no criticism, others of which even deserve slight praise, to separate them from his foolish and criminal deeds, of which I shall now give an account.

Book Six: XX His Musical Education and Debut in Naples

Having acquired some grounding in music during his early education, he sent for Terpnus, on his accession, who was the greatest lyre-player of the day, and after hearing him sing after dinner for many nights in succession till a very late hour, Nero began to practise himself, gradually undertaking all the usual exercises that singers follow to strengthen and develop the voice. He would lie on his back clasping a lead plate to his chest, purge himself by vomiting and enemas, and deny himself fruit and other foods injurious to the voice.

Encouraged by his own progress, though his singing was feeble and hoarse, he soon longed to appear on the stage, and now and then would quote the Greek proverb to close friends: ‘Music made secretly wins no respect.’

He made his debut at Naples, where he sang his piece through to the end despite the theatre being shaken by an earth tremor. He often sang in that city, for several days in succession. Even when he took time out to rest his voice he could not stay out of sight, visiting the theatre after bathing, and dining in the orchestra, where he promised the crowd in Greek that when he had ‘oiled his throat’ a little he would give them something to make their ears ring.

He was thrilled too by the rhythmic clapping of a group of Alexandrians, from the fleet which had just put in, and sent to Alexandria for more such supporters. Not content with that, he chose some young men from the Equestrian Order along with five thousand energetic young commoners who were divided into three separate groups, known as the ‘Bees’, ‘Tiles’ and ‘Bricks’, to learn the various styles of Alexandrian acclaim and employ them vigorously whenever he sang. They were easy to recognise by their bushy hair, splendid clothes, and the lack of rings on their left hands. Their leaders were paid four hundred gold pieces apiece.

Book Six: XXI His Debut in Rome

Considering it vital to debut in Rome as well, he held the Neronia again before the five-year date. A universal plea from the crowd to hear his celestial voice received the reply that if anyone wished to hear him he would perform later in the Palace gardens, but when the Guards on duty added their weight to the appeal, he happily agreed to oblige there and then. He immediately added his name to the list of entrants for the lyre-playing, and cast his lot into the urn with the rest. When his turn came round he appeared, accompanied by the Guards commanders carrying his lyre, and followed by a group of colonels and close friends. After taking his place on stage and giving the usual introduction he announced via the ex-consul Cluvius Rufus that he would sing ‘Niobe’, which he did, until early evening, deferring the prize-giving for the event and postponing the rest of the contest until the following year, to provide another opportunity for singing.

But since that seemed to him too long to wait, he continued to perform in public from time to time. He even considered taking part in the public shows given by magistrates, after receiving an offer of ten thousand gold pieces from a praetor if he would agree to perform opposite the professional singers.

Nero also sang in tragedies, assuming the part of a hero or god, even on occasions of a heroine or goddess, wearing a mask modelled on his own features or, for the female parts, on the features of whatever woman he happened to be enamoured of at the time. Among his performances were ‘Canace in Childbirth, ‘Orestes the Matricide’, ‘Oedipus Blinded’, and ‘The Crazed Hercules’. During his performance as Hercules, or so the tale goes, a young recruit guarding the entrance seeing his Emperor in ragged clothes and weighed down with chains as the part demanded, dashed forward to lend him aid.

Book Six: XXII Chariot-Racing and the Trip to Greece

Nero was interested in horsemanship from an early age, and could not be prevented from chattering endlessly about the races in the Circus. On one occasion when his tutor scolded him for bemoaning, to his fellow pupils, the fate of a charioteer of the Green faction who had been dragged behind his horses, he claimed untruthfully that he had been talking about Hector.

At the start of his reign he used to play with ivory chariots on a board, and came up from the country to attend the Games, however insignificant they might be, in secret at first and then so openly that everyone knew he would be in Rome that day.

He made his longing for extra races so clear that prizes were added until events lasted so late in the day that the managers of the various factions fielded their teams of drivers in expectation of a full day’s racing.

He soon set his heart on driving a chariot himself, and even competing regularly, so that after a trial run in the Palace gardens with an audience of slaves and idlers, he made his public appearance in the Circus, one of his freedmen dropping the napkin to start the race from the seat usually occupied by a magistrate.

Not satisfied with demonstrating his skills in Rome, he took a trip to Greece (in 67AD), as I have said, influenced primarily by the fact that the cities holding music contests had started awarding him all their prizes for lyre-playing. He was delighted by these, and would not only give precedence to the Greek delegates at his audiences, but would also invite them to dine with him in private. They begged him to perform after dinner and greeted his singing with such wild applause that he used to say that the Greeks alone had an ear for music, and were worthy of his efforts.

So he did not hesitate to set sail, and once arrived at Cassiope (Kassiopi on Corfu) he made his Greek debut as a singer at the altar of Jupiter Cassius, before making a round of the contests held by various cities.

Book Six: XXIII His Anxiety When Competing

In order to achieve this he ordered that the various contests, though normally held at different intervals, should all be staged in his presence, even forcing some to be repeated that year. He also introduced a music competition at Olympia contrary to normal practice. He refused to be distracted or hindered in any way while preoccupied with these contests, and when his freedman Helius reminded him that Imperial affairs required his presence in Rome he answered: ‘Advise a swift return if you wish: but better to hope and advise I return having done justice to Nero.’

While he was singing no one could leave the theatre however urgent the need, forcing women to give birth there, or so they say. Many spectators, wearied with listening and applauding, furtively dropped from the wall at the back, since the doors were closed, or pretended to die and have themselves carried off for burial.

His nervousness and anxiety when he took part, his acute competitiveness where rivals were concerned, and his awe of the judges, were scarcely credible. He would treat the other contestants with respect almost as if they were equals, and try to curry favour with them, while abusing them behind their backs, and occasionally to their faces if he encountered them elsewhere, even offering bribes to those who were particularly skilled to encourage them to perform badly.

Before he began his performance he would address the judges with the utmost deference, saying that he had prepared as well as he could, and that the outcome was in the hands of Fortune, but that they were equipped with the knowledge and experience to ignore the effects of chance. When they had reassured him, he would take his place with greater equanimity, but not without a degree of anxiety even then, interpreting the diffidence and taciturnity of some as severity and malevolence, and declaring that he was doubtful of their intentions.

Book Six: XXIV His Behaviour in Competition

He observed the rules scrupulously while competing, not daring to clear his throat, and wiping sweat from his brow only with his bare arm. Once, while acting in a tragedy, he dropped his sceptre and quickly recovered it, but was terrified of being disqualified as a result, and his confidence was only restored when his accompanist whispered that the slip had passed unnoticed amidst the delight and acclamation of the audience. He took it upon himself to announce his own victories, and so always took part in the competition to select the heralds.

To erase the record of previous victors in the contest, and suppress their memory, he ordered all their busts and statues to be toppled, dragged away with hooks and thrown into the sewers.

At many events he also raced a chariot, driving a ten-horse team at Olympia, although he had criticised Mithridates in one of his own poems for doing just that, though after being thrown from the chariot and helped back in, he was too shaken to stay the course, though he won the crown just the same. Before his departure, on the day of the Isthmian Games, he himself announced, from the midst of the stadium, that he granted the whole province of Achaia the freedom of self-government, and all the judges Roman citizenship plus a large gratuity.

Book Six: XXV Return from Greece

Returning to Italy, Nero landed at Naples, since he had made his first stage appearance there. He had part of the city wall levelled, as is the custom for welcoming back victors in the sacred Games, and rode through behind a team of white horses. He made a similar entry to Antium (Anzio), Albanum (Albano Laziale), and finally Rome.

At Rome he rode in the same chariot that Augustus had used for his triumphs in former times, and wore a purple robe, and a Greek cloak decorated with gold stars. He was crowned with an Olympic wreath, and carried a Pythian wreath in his right hand, while the other wreaths he had won were borne before him inscribed with details of the various contests and competitors, the titles of the songs he had sung, and the subjects of the plays in which he had acted. His chariot was followed by his band of hired applauders as if they were the escort to a triumphal procession, shouting as they went that they were the companions of Augustus, and his victorious troops. He progressed through the Circus, the entrance arch having been demolished, then via the Velabrum and Forum to the Palatine Temple of Apollo. Sacrificial offerings were made all along the route and the streets were sprinkled with fragrances, while song-birds were released, and ribbons and sweetmeats showered on him.

He scattered the sacred wreaths around the couches in his sleeping quarters, and set up statues of himself playing the lyre. He also ordered a coin to be struck bearing the same device. Far from neglecting or moderating his practice of the art thereafter, he would address his troops by letter or have his speeches delivered by someone else, to preserve his voice. And he never carried out anything in the way of business or entertainment without his elocutionist beside him, telling him to spare his vocal chords, and proffering a handkerchief with which to protect his mouth.

He offered his friendship to, or declared his hostility towards, hosts of people depending on how generous or grudging towards him they had shown themselves by their applause.

Book Six: XXVI His Evil Nature

His initial acts of insolence, lust, extravagance, avarice and cruelty were furtive, increasing in frequency quite gradually, and therefore were condoned as youthful follies, but even then their nature was such they were clearly due to defects of character, and not simply his age.

As soon as darkness fell, he would pull on a cap or wig and make a round of the inns or prowl the streets causing mischief, and these were no harmless pranks either; since he would beat up citizens walking home from a meal, stabbing those who resisted and tumbling them into the sewer. He broke into shops and stole the goods, selling them at auctions he held in the Palace as if in a marketplace, and squandering the proceeds.

In the violence that ensued from his exploits he often ran the risk of losing his sight or even his life, being beaten almost to death by a Senator whose wife he maltreated. This taught him never to venture out after dark without an escort of Guards colonels following him at a distance, unobserved.

In daytime he would have himself carried to the theatre in a sedan chair, and would watch from the top of the proscenium as the pantomime actors brawled, urging them on and joining in, when they came to blows and threw stones and broken benches, by hurling missiles at the crowd, on one occasion fracturing a praetor’s skull.

Book Six: XXVII His Increasing Wickedness

Gradually, as the strength of his vices increased, he no longer hid them, or laughed them off, but dropped all disguise, and indulged freely in greater depths of wickedness.

His revels lasted from noon to midnight. If it were winter he restored himself by a warm bath, or in summer plunged into water cooled with snow.

Occasionally he would drain the lake in the Campus Martius, and hold a public banquet on its bed, or in the Circus, waited on by harlots and dancing-girls from all over the City. And whenever he floated down the Tiber to Ostia, or sailed over the Gulf of Baiae, temporary eating and drinking houses appeared at intervals along the banks and shores, with married women playing the role of barmaids, peddling their wares, and urging him on, from every side, to land.

He extracted promises of banquets from his friends too; one spending forty thousand gold pieces on a dinner with an Eastern theme; another consuming an even vaster sum on a party themed with roses.

Book Six: XXVIII His Sexual Debauchery

Nero not only abused freeborn boys, and seduced married women, but also forced the Vestal Virgin Rubria. He virtually married the freedwoman Acte, after bribing some ex-consuls to perjure themselves and swear she was of royal birth.

He tried to turn the boy Sporus into a woman by castration, wed him in the usual manner, including bridal veil and dowry, took him off to the Palace attended by a vast crowd, and proceeded to treat him as his wife. That led to a joke still going the rounds, to the effect that the world would have been a better place if Nero’s father Domitius had married that sort of wife.

Nero took Sporus, decked out in an Empress’s regalia, to all the Greek assizes and markets in his litter, and later through the Sigillaria quarter at Rome, kissing him fondly now and then.

He harboured a notorious passion for his own mother, but was prevented from consummating it by the actions of her enemies who feared the proud and headstrong woman would acquire too great an influence. His desire was more apparent after he found a new courtesan who was the very image of Agrippina, for his harem. Some say his incestuous relations with his mother were proven before then, by the stains on his clothing whenever he had accompanied her in her litter.

Book Six: XXIX His Erotic Practices

He debased himself sexually to the extent that, after exploiting every aspect of his body, he invented an erotic game whereby he was loosed from a cage dressed in a wild animal’s pelt, attacked the private parts of men and women bound to stakes, and when excited enough was ‘dispatched’ by his freedman Doryphorus. He even became Doryphorus’s bride, as Sporus was his, and on the wedding night imitated the moans and tears of a virgin being deflowered.

I have been told, more than once, of his unshakeable belief that no man was physically pure and chaste, but that most concealed their vices and veiled them cunningly. He therefore pardoned every other fault in those who confessed to their perversions.

Book Six: XXX His Extravagance

Nero thought a magnificent fortune could only be enjoyed by squandering it, claiming that only tight-fisted miserly people kept a close account of their spending, while truly fine and superior people scattered their wealth extravagantly. Nothing so stirred his admiration and envy of Caligula, his uncle, as the way he had run through Tiberius’s vast legacy in such a short space of time. So he showered gifts on people and poured money away.

He spent eight thousand gold pieces a day on Tiridates, though it seems barely believable, and made him a gift on parting of more than a million. He presented Menecrates the lyre-player and Spiculus the gladiator with mansions and property worthy of those who had celebrated triumphs, and gifted the monkey-faced moneylender Paneros town-houses and country estates, burying him with well-nigh regal splendour when he died.

Nero never wore the same clothes twice. He placed bets of four thousand gold pieces a point on the winning dice when he played. He fished with a golden net strung with purple and scarlet cord. And he rarely travelled, they say, with less than a thousand carriages, the mules being silver-shod, the drivers’ clothes made of wool from Canusium (Canosa), escorted by Mauretanian cavalry and couriers adorned with bracelets and medallions.

Book Six: XXXI Public Works and the Golden House

There was nothing more ruinously wasteful however than his project to build a palace extending from the Palatine to the Esquiline, which he first called ‘The Passageway’, but after it had burned down shortly after completion and been re-built, ‘The Golden House’. The following details will give a good idea of its size and splendour.

The entrance hall was large enough to contain a huge, hundred-foot high, statue of the Emperor, and covered so much ground the triple colonnade was marked by milestones. There was an enormous lake, too, like a small sea, surrounded by buildings representing cities, also landscaped gardens, with ploughed fields, vineyards, woods and pastures, stocked with wild and domestic creatures.

Inside there was gold everywhere, with gems and mother-of-pearl. There were dining rooms whose ceilings were of fretted ivory, with rotating panels that could rain down flowers, and concealed sprinklers to shower the guests with perfume. The main banqueting hall was circular with a revolving dome, rotating day and night to mirror the heavens. And there were baths with sea-water and sulphur water on tap.

When the palace, decorated in this lavish style, was complete, Nero dedicated the building, condescending to say by way of approval that he was at last beginning to live like a human being.

He began work on a covered waterway flanked by colonnades, stretching from Misenum to Lake Avernus, into which he planned to divert all the various hot springs rising at Baiae. And he also started on a ship-canal connecting Avernus to Ostia, a distance of a hundred and sixty miles, of a breadth to allow two quinqueremes to pass. To provide labour for the tasks he ordered convicts from all over the Empire to be transported to Italy, making work on these projects the required punishment for all capital crimes.

Nero relied not merely on the Empire’s revenues, to fuel his wild extravagance, but was also convinced by the positive assurances of a Roman knight that a vast treasure, taken to Africa long ago by Queen Dido on her flight from Tyre, was concealed in extensive caves there, and could be retrieved with the minimum of effort.

Book Six: XXXII His Methods of Raising Money

When the tale proved false, he found himself in such desperate straits, so impoverished, that he was forced to defer the soldiers’ pay and veteran’s benefits, and turn to blackmail and theft.

Firstly, he introduced a law stating that if a freedman died who had taken the name of a family connected to himself, and could not justify why, five-sixths of their estate rather than merely half should be made over to him. Furthermore those who showed ingratitude by leaving him nothing or some paltry amount forfeited their property to the Privy Purse, and the lawyers who had written and dictated such wills were to be punished. Finally, anyone whose words or actions left them open to being charged by an informer was liable under the treason laws.

He recalled the gifts he had made to Greek cities which had awarded him prizes in their contests. After prohibiting the use of amethystine and Tyrian purple dyes, he sent an agent to sell them covertly in the markets, and closed down all the dealers who bought, confiscating their assets. It is even said that on noticing a married woman in the audience at one of his recitals wearing the forbidden colour he pointed her out to his agents who dragged her out and stripped her there and then, not only of her robes but also her property.

Nero would never appoint anyone to office without adding: ‘You know my needs! Let’s make sure no one has anything left.’

Ultimately he stripped the very temples of their treasures and melted down the gold and silver images, including the Household Gods (Penates) of Rome, which Galba however recast not long afterwards.

Book Six: XXXIII His Murder of Claudius and Britannicus

He began his parricidal career with the death of Claudius, for even if he did not instigate that Emperor’s murder, he was certainly privy to it, as he freely admitted, and thereafter was wont to praise mushrooms, by means of which his adoptive father was poisoned, as the ‘food of the gods’ in accord with the Greek proverb.

After Claudius’s death, he abused his memory in every way, in both words and actions, accusing him of idiocy or cruelty, it being a favourite joke of his to say that Claudius being dead could no longer ‘entertain mortal life’ stressing the first syllable of ‘entertain’. He set aside many of Claudius’s acts and decrees as the work of a feeble-minded old man, and enclosed the place where Claudius was cremated with nothing more than a low makeshift wall.

He tried to do away with Britannicus by poisoning him too, no less through envy of his voice, which was more mellifluous than his own, than for fear that his father’s memory would win him greater popular approval. He procured the venom from a certain Lucusta, an expert in such substances, summoning her when the poison’s effects proved sluggish, flogging her himself, and claiming she had provided him with medicine not poison. When she explained she had used a small dose to save his action from detection, he replied: ‘Do you think I’m afraid of the Julian law?’ before insisting that she prepare the fastest-acting most certain mixture she knew, before his eyes, in that very room. He tested it on a kid, but the creature took five hours to die, so he had her make a more concentrated brew and gave it to a pig which died on the spot. He then had it administered to Britannicus with his food. The lad dropped dead after the very first taste, but Nero lied to the guests claiming it as an instance of the epileptic fits to which the boy was liable. The next day he had Britannicus interred, hastily and unceremoniously, during a heavy downpour. Lucusta was rewarded with a free pardon for past offences, and extensive country estates, and Nero also provided her with a stream of willing acolytes.

Book Six: XXXIV His Murder of his Mother and Aunt

His mother Agrippina annoyed him deeply, by casting an over-critical eye on his words and actions. Initially he discharged his resentment simply by frequent attempts to damage her popularity, pretending he would be driven to abdicate and flee to Rhodes. He progressively deprived her of her honours and power, then of her Roman and German bodyguard, refusing to let her live with him, and expelling her from the Palace. He passed all extremes in his hounding of her, paying people to annoy her with lawsuits while she was in the City, and then after her retirement to the country, sending them by land and sea to haunt the grounds and disturb her peace, with mockery and abuse.

Weary at last of her violent and threatening behaviour, he decided to have her killed, and after three poisoning attempts which she evaded by the use of antidotes, he had a false ceiling created to her bedroom, with a mechanism for dropping the heavy panelling on her as she slept. When those involved chanced to reveal the plot, he next had a collapsible boat designed which would cause her drowning or crush her in her cabin. He then feigned reconciliation and sent her a cordial letter inviting her to Baiae to celebrate the Feast of Minerva (Quinquatria) with him. He instructed one of his naval captains to ensure the galley she arrived in was damaged, as if by accident, while he detained her at a banquet. When she wished to return to Bauli (Bacoli) he offered his collapsible boat in place of the damaged one, escorting her to the quay in jovial mood, and even kissing her breasts before she boarded. He then passed a deeply anxious and sleepless night, awaiting the outcome of his actions.

Driven to desperation by subsequent news that his plan had failed, and that she had escaped by swimming, he ordered her freedman, Lucius Agermus, who had joyfully brought the information, arrested and bound, a dagger having been surreptitiously dropped near him, on a charge of attempting to kill his Emperor, and commanded that his mother be executed, giving out meanwhile that she had escaped the consequences of her premeditated crime by committing suicide. Reputable sources add the more gruesome details: that he rushed off to view the corpse, pawing her limbs while criticising or commending their features, and taking a drink to satisfy the thirst that overcome him.

Yet he was unable, then or later, to ignore the pangs of conscience, despite the congratulations by which the soldiers, Senate, and people, tried to reassure him, and he often confessed that his mother’s ghost was hounding him and the Furies too with their fiery torches and whips. He went to the lengths of having Magi perform their rites, in an effort to summon her shade and beg for forgiveness. And on his travels in Greece he dared not participate in the Eleusinian mysteries, since before the ceremony the herald warns the impious and wicked to depart.

Having committed matricide, he now compounded his crimes by murdering his aunt, Domitia. He found her confined to bed with severe constipation. As old ladies will, she stroked his downy beard (since he was now mature), and murmured fondly: ‘When you celebrate your coming-of-age and send me this, I’ll die happy.’ Nero promptly turned to his companions and joked: ‘Then I’ll shave it off here and now!’ Then he ordered the doctors to give her a fatal purge, and seized her property before she was cold, suppressing the will so nothing escaped him.

Book Six: XXXV More Family Murders

He married two wives after Octavia. The first was Poppaea Sabina (from AD62), daughter of an ex-quaestor, married at that time to a Roman knight, and the second was Statilia Messalina, great-great-granddaughter of Statilius Taurus, who had twice been consul and had been awarded a triumph. In order to wed Statilia (in AD66) he first murdered her husband Atticus Vestinus, who was then a consul.

Life with Octavia had soon bored him, and when his friends criticised his attitude, he replied that she should have contented herself with bearing the name of wife. He tried to strangle her on several occasions but failed, so divorced her, claiming she was barren. He responded to public disapproval and reproach by banishing her, as well, and finally had her executed on a charge of adultery so ludicrous and insubstantial that after torturing witnesses who merely substantiated her innocence, he was forced to bribe his former tutor Anicetus to provide a false confession that through her deceit he had lain with her.

Nero doted on Poppeia, whom he married twelve days after divorcing Octavia, yet he caused her death by kicking her when she was pregnant and ill, because she complained of his coming home late from the races. She had borne him a daughter, Claudia Augusta, who died in infancy.

There was no family relationship which Nero did not brutally violate. When Antonia, Claudius’s daughter refused to marry him after Poppaea’s death he had her charged with rebellion and executed (in AD66). That was how he treated all who were connected to him by blood or marriage.

Among them was young Aulus Plautius whom he indecently assaulted before having him put to death, saying ‘Now, Mother can kiss my successor’. Nero openly claimed that the dead Agrippina had loved Aulus and that this had given him hopes of the succession.

He ordered Rufrius Crispinus, Poppaea’s child by her former husband, to be drowned in the sea by the boy’s slaves while fishing, simply because he was said to have acted out the parts of general and emperor in play. He banished his nurse’s son Tuscus because as procurator of Egypt he had dared to use the baths newly-built for Nero’s visit.

When Seneca, his tutor, begged to be allowed to relinquish his property and retire, Nero swore most solemnly that Seneca was wrong to suspect him of wishing to do him harm, as he would rather die than do such a thing, but he drove him to suicide, regardless.

Nero sent Afranius Burrus, the Guards commander, poison instead of the throat medicine he had promised him, also poisoning the food and drink of the two rich old freedmen who had originally aided his adoption by Claudius as his heir, and who had later helped him with their advice.

Book Six: XXXVI The Pisonian Conspiracy

He attacked those outside his family with the same ruthlessness. Nero was caused great anxiety by the appearance of a comet which was visible for several nights running, an event commonly believed to prophesy the death of some great ruler. His astrologer Balbillus told him that princes averted such omens, and diverted the effect onto their noblemen, by contriving the death of one of them, so Nero decide to kill all his most eminent statesmen, and was later convinced to do so all the more, and apparently justified in doing so, by the discovery of two conspiracies against him.

The first and more dangerous was that of Calpurnius Piso in Rome (in AD65); the second initiated by Vinicius was discovered at Beneventum (Benevento). The conspirators were brought to trial triply-chained, some freely admitting guilt, and saying they had sought to do the Emperor a favour, since only his death could aid one so tainted by every kind of crime. The children of those condemned were banished, poisoned, or starved to death. A number of them were massacred together with their tutors and attendants, while at a meal, while others were prevented from earning a living in any way.

Book Six: XXXVII Indiscriminate Persecution

Thereafter Nero dispensed with all moderation, and ruined whoever he wished, indiscriminately and on every imaginable pretext. To give a few instances: Salvidienus Orfitus was charged with letting three offices, which were part of his house near the Forum, to certain allied states; Cassius Longinus, a blind advocate, with exhibiting a bust of Gaius Cassius, Caesar’s assassin, among his family images; and Paetus Thrasea with having the face of a sullen schoolteacher.

He never allowed more than a few hours respite to any of those condemned to die, and to hasten the end he had physicians in attendance to ‘take care’ of any who lingered, his term for opening their veins to finish them off. He was even credited with longing to see living men torn to pieces and devoured by a certain Egyptian ogre who ate raw flesh and anything else he was given.

Elated by his ‘achievements’ as he called them, he boasted that no previous ruler had ever realised his power to this extent, hinting heavily that he would not spare the remaining Senators, but would wipe out the whole Senate one day and transfer rule of the provinces and control of the army to the knights and his freedmen. He certainly never granted Senators the customary kiss when starting or ending a journey, nor ever returned their greetings. And when formally inaugurating work on the Isthmus canal project, before an assembled crowd, he prayed loudly that the event might benefit ‘himself and the Roman people’ without mentioning the Senate.

Book Six: XXXVIII The Great Fire of Rome

But Nero showed no greater mercy towards the citizens, or even the walls of Rome herself. When in the course of conversation someone quoted the line:

‘When I am dead, let fire consume the earth,’

he commented ‘No, it should rather be – while I yet live…’ and acted accordingly, since he had the City set on fire, pretending to be displeased by its ugly old buildings and narrow, winding streets, and had it done so openly that several ex-consuls dared not lay hands on his agents, though they caught them in situ equipped with blazing torches and tar. Various granaries which occupied desirable sites near the Golden House were partly demolished by siege engines first, as they were built in stone, and then set ablaze.

The conflagration lasted seven nights and the intervening days, driving people to take refuge in hollow monuments and tombs. Not only a vast number of tenement blocks, but mansions built by generals of former times, and still decorated with their victory trophies, were damaged, as well as temples vowed and dedicated by the kings, or later leaders during the Punic and Gallic wars, in fact every ancient building of note still extant. Nero watched the destruction from the Tower of Maecenas, and elated by what he called ‘the beauty of the flames’ he donned his tragedian’s costume and sang a composition called The Fall of Troy from beginning to end.

He maximised his proceeds from the disaster by preventing any owner approaching their ruined property, while promising to remove the dead and the debris free of charge. The contributions for rebuilding, which he demanded and received, bankrupted individuals and drained the provinces of resources.

Book Six: XXXIX Disasters and Abuse

Various other misfortunes were added by fate to the disasters and scandals of his reign. A plague resulted in thirty thousand deaths being registered at the shrine of Venus Libitina, in a single autumn. There was also the disastrous sack of two major towns in Britain (60/61AD), in which a host of citizens and allies were massacred, and a shameful defeat in the East (62AD), where the legions in Armenia went beneath the yoke, and Syria was almost lost.

It is strange and certainly worth noting that Nero seemed amazingly tolerant of public abuse and curses, at this time, and was especially lenient towards the perpetrators of jokes and lampoons. Many of these were posted on walls or circulated, in both Greek and Latin. For example, the following:

‘Nero, Orestes, Alcmaeon’s the other, each of them murdered his mother.’

‘Add the letters in Nero’s name, and ‘matricide’ sums the same.’

‘Who can deny that Nero is truly Aeneas’s heir?

Aeneas cared for his father, of his mother the other took care.’

‘As long as our lord twangs his lyre, the Parthian the bow,

We’re still ruled by the Healer, by the Far-Darter our foe.’

‘Rome’s one enormous House, so off to Veii, my friend,

If only it hasn’t swallowed Veii as well, in the end!’

Yet he made no effort to hunt out the authors. Indeed, when an informer reported some of them to the Senate, Nero prevented their being punished with any severity.

Once, as he crossed the street, Isidorus the Cynic taunted him loudly with making a good song out of Nauplius’s ills, but making ill use of his own goods. Again, Datus, an actor in Atellan farce, mimed the actions of drinking and swimming to the song beginning:

‘Farewell father, farewell mother…’

since Claudius had been poisoned, and Agrippina nearly drowned, and at the last line:

‘The Lord of the Dead directs your steps…’

he gestured towards the Senators present. Nero was either impervious to insult, or avoided showing his annoyance in order to discourage such witticisms, since he was content merely to banish the philosopher and the actor from Rome and the rest of Italy.

Book Six: XL Uprising in Gaul

After the world had endured such misrule for fourteen years, it finally rid itself of him. The initiative was taken by the Gauls under Julius Vindex, a provincial governor.

Some astrologers predicted he would be deposed one day, which earned the well-known retort: a little art will meet our daily needs, presumably referring to his lyre-playing, an emperor’s amusement that would support him as a private citizen. Others promised he would command the East after his deposition, and one or two expressly indicated his ruling from Jerusalem. Others claimed former possessions would be restored, and he placed his hope in the fact that Armenia and Britain had both been lost and both regained, which led him to think that he had already suffered the ills fate had in store.

He felt confident after consulting the Delphic Oracle, which warned him to beware the seventieth year, which he took to mean that he would die then, not dreaming it referred to Galba’s age, and instilled him with such confidence in a long life, and rare and unbroken good fortune, that when he lost some articles of great value in a shipwreck, he simply told his close friends that the fishes would return them to him.

It was at Naples, on the anniversary of his mother’s murder, that he heard of the Gallic uprising (in 67/68AD), and received the news so calmly and with such indifference that he was suspected of welcoming the chance to pillage those rich provinces as in wartime. He slipped off to the gymnasium where he watched the athletic contests with rapt attention. When a messenger interrupted his dinner with a despatch warning that the situation was growing yet more serious, he confined himself merely to threats of vengeance on the rebels. In fact he made no reply, and wrote no requests or orders for eight days, shrouding the whole business in silence.

Book Six: XLI Continuing Rebellion

At last a series of insulting edicts, issued by Vindex, drove Nero to write to the Senate urging that they exact vengeance on behalf of himself and Rome, while pleading a throat infection as his reason for not appearing in person. He resented above all the taunt that his efforts with the lyre were wretched, and being addressed as Ahenobarbus instead of Nero. Yet he told the Senate he would renounce his adopted name and resume this family name which was being mocked. As for his lyre-playing how could he be unskilled in an art which had claimed so much of his attention, and in which he had achieved perfection, always enquiring of various individuals whether they knew of any better a performer, argument enough surely to demonstrate the falsity of the other abusive comments.

A ceaseless flow of urgent despatches finally sent him back to Rome in a panic, though his spirits rose on observing a minor omen on the way: the sight of a monument on which a Roman cavalryman was sculpted dragging a defeated Gallic soldier by the hair. In a transport of joy at the sign, he raised his hands to heaven.

Once in the City he made no personal plea to the Senate or people, but gathered various leading citizens to the Palace for a hasty consultation, after which he spent the day demonstrating some water-powered musical instruments, built to a new design, explaining the various features of these organs, with a dissertation on the mechanically complex theory of each, and maintaining that he would soon have them installed in the Theatre ‘if Vindex will allow it.’

Book Six: XLII Galba’s Insurrection

But when news of Galba’s insurrection in Spain arrived, he fainted away and lay there insensible for a long while, mute and seemingly dead. When he came to, he tore his clothes and beat his forehead, crying that all was over with him. His old nurse tried to comfort him, reminding him that other princes had suffered like evils before, but he shouted out that on the contrary his fate was unparalleled since none had been known to lose supreme power while they still lived.

However he made no attempt thereafter to abandon or even modify his lazy and extravagant ways. Indeed, when tidings from the provinces proved good, he not only gave lavish banquets, but even ridiculed the rebels in verse, later published, which was set to bawdy music accompanied by appropriate gestures. And he stole into the audience room of the Theatre, to convey a message to an actor whose performance was going well, to say that he ought not to take advantage of the emperor’s absence on business.

Book Six: XLIII Nero’s Reaction to the Gallic Rebellion

At the first news of the Gallic revolt Nero is thought to have formed a characteristically perverse and wicked plan to depose the army commanders and provincial governors and execute them on charges of conspiracy; to murder all exiles, for fear they might join the rebels, and all the Gallic residents of Rome as sharing in and abetting their countrymen’s designs; to allow his armies to ravage the Gallic provinces; to poison the entire Senate at a banquet; and to set the City alight after loosing the wild beasts to prevent the citizens saving themselves.

He was deterred not by any compunction on his part but because he despaired of being able to carry out his plan. Feeling driven to take military action himself, he dismissed the consuls before their term ended, and took sole office, as if the Gallic provinces were fated only to be subdued by himself as consul. Having assumed the consular insignia, he then declared, as he left the dining room after the banquet, his arms round the shoulders of two friends, that when he reached Gaul he would present himself unarmed and in tears, to the soldiers, and having won them to his side in this way, such that they abandoned their intentions, he would be ready to rejoice next day among his joyful subjects, singing the victory paean which he really ought to be composing at that very moment.

Book Six: XLIV His Preparations for a Campaign

His first thought in preparing for a campaign was allocating the wagons to carry his theatrical props, and since he intended to take his concubines with him, to have their hair trimmed in manly style, and have them issued with Amazonian axes and shields.

He then called the City tribes to arms, and when no one claimed to be eligible, levied a number of the choicest slaves from each household refusing exemption even to stewards and secretaries. A contribution of part of their incomes was demanded from every house-owning class, and the tenants of private houses and apartments were required to pay their year’s rent immediately to the Privy Purse. He insisted rigorously and fastidiously on payment in newly-minted coin, refined silver or pure gold, so that many people refused to contribute, openly and unanimously demanding that he reclaim their fees from his paid informers instead.

Book Six: XLV Popular Resentment

Resentment against him intensified because he was known to be profiting from the high cost of grain. And while people were short of food, news arrived of a ship from Alexandria that instead of a cargo of corn had brought sand for his wrestling arena.

Nero aroused such universal hatred he was spared no form of insult. A trailing lock of hair was stuck to the head of one of his statues, and a note in Greek attached: ‘at last here’s a real contest for you to lose!’ A sack was tied round the neck of another with the words: ‘I did all that I could do!’ – ‘But it’s still the sack for you!’ People wrote on the columns that he had even roused the Gallic cocks with his crowing. And, at night, they pretended to be quarrelling with their slaves crying out that ‘the Avenger’ (Vindex) was coming.

Book Six: XLVI Dreams and Omens

He was terrified by manifest portents, old as well as new, implied by dreams, auspices and omens. After he murdered his mother, though he had not been wont to recall his dreams, he seemed in sleep to be steering a ship when the rudder was wrenched from his hands; then he dreamed his wife Octavia drew him down into deep shadows; then that he was clothed in a swarm of flying ants; that the statues of the nations dedicated in Pompey’s Theatre surrounded him and prevented his going further; and that an Asturian horse, a favourite of his, turned into an ape, all except its head, which whinnied tunefully.

As for auspices and omens, the doors of the Mausoleum opened spontaneously and a voice was heard calling out his name. Then on New Year’s Day, when the statues of the Household Gods had been decorated, they tumbled to the ground as the sacrifice was being prepared, and while Nero was taking the auspices, Sporus gave him a ring whose stone was engraved with the rape of Proserpine. When a large crowd gathered to pay their annual vows (for the prosperity of Emperor and State) the keys of the Capitol were found to have been mislaid and were not discovered for some time.

Again, when a speech of his was being read in the Senate, which vilified Vindex, the words ‘...and punish the wicked soon, they must meet the end they deserve’ was greeted with the unanimous and ambiguous cry of: ‘You will do so, Augustus.’

It did not escape notice either that at his last public recital he sang the part of Oedipus in Exile, ending with the line:

‘They drive me to my death: wife, mother, father.’

Book Six: XLVII Preparations for Flight

He tore to pieces despatches bringing news that the rest of the military were also in rebellion. The messages were handed to him while he was dining, and he overturned the table, sending his two favourite drinking cups flying, those he called ‘Homeric’ as they were engraved with scenes from the epics. He then had Lucusta supply him with a poisonous substance which he placed in a golden box, and crossed to the Servilian Gardens where he tried to persuade the Guards officers to flee with him, his most loyal freedmen having been sent ahead to Ostia to ready the fleet. But some answered evasively and others flatly refused, one even shouting out Virgil’s line: ‘Is it so terrible a thing to die?’

Nero then considered various options, whether for instance to throw himself on the mercy of the Parthians or of Galba; or to show himself on the Rostra dressed pathetically in black and beg the people to pardon his past sins; or if he could not soften their hearts, at least entreat them to grant him Egypt as a prefecture. A speech composed for this latter purpose was discovered later among his papers, but it is thought that he was too scared to deliver it fearing to be torn to pieces before he could reach the Forum.

He put off any further decision to the following day, but waking at midnight and finding the Guards had deserted him, he leapt from his bed and sent for his friends. Receiving no reply he went to their rooms with a handful of servants, but finding the doors locked and obtaining no answer returned to his own room to find that the caretakers had fled taking with them the box of poison and even the bed linen. He at once shouted for Spiculus, the gladiator, or someone else skilled in dealing death at whose hands he might perish, and when no one appeared, cried out: ‘Have I not one friend or enemy left? He then scurried from the Palace as if intending to throw himself into the Tiber.

Book Six: XLVIII A Last Hiding-Place

But again altering his purpose, he looked for some quiet spot where he could hide, and gather his wits. When Phaon, his freedman, suggested his own villa in the north-eastern suburbs, four miles or so distant, between the Via Nomentana and the Via Salaria, Nero mounted a horse, barefoot, his tunic covered by a faded cloak, and holding a handkerchief to his face, rode off with only four attendants including Sporus.

Immediately there was an earth-tremor and a flash of lightning illuminated him. He could hear the shouts of soldiers from the nearby camp, foretelling his ruin and Galba’s triumph. One traveller they met cried: ‘They’re after Nero.’ While another asked: ‘What news of him in the City?’ Then his horse shied at the smell of a corpse by the roadside, causing him to expose his face, at which point he was recognised by a retired Guard who promptly saluted.

When they reached a lane leading to the villa, they abandoned the horses, and followed a track, through brushes, brambles and a reed-bed, leading to the rear wall of the house. The going was difficult, and at places a cloak was thrown down for him to walk on. Phaon begged him to lie low in a sand-pit but he refused, saying he would not go ‘down below’ before he was dead, and while waiting for a secret entrance to the villa to be constructed, he scooped up water from a nearby pool in his hand, and drank it saying: ‘This is Nero’s ice-water.’

Then he pulled out the thorns which had pierced his cloak, before crawling on all fours through the tunnel that had been dug as an entry to the villa and in the first room he reached sinking onto a bed, with a rough mattress, over which an old cloak had been flung. Though hungry and again thirsty he refused the coarse bread offered him, but sipped a little lukewarm water.

Book Six: XLIX His Death

Finally, when his companions urged him, one and all, to escape the impending insults that threatened him, he ordered them to dig a grave, there and then, suitable for a man of his proportions, bring any pieces of marble they could find, and fetch water and wood for washing and burning his corpse, in a little while. While they carried this out, he was in tears, repeatedly murmuring: ‘What an artist dies here!’

While he endured the wait, a letter arrived for Phaon by courier. Nero snatched it from his hand and read that having been declared a public enemy by the Senate he would be punished in the ancient fashion. Asking what that was he learned that the victim was stripped naked, had his head thrust in a wooden fork, and was then beaten to death with rods. Terrified by the thought, he grasped the two daggers he had brought with him, but after testing their sharpness threw them down again, claiming the final hour had not yet come. He begged Sporus to weep and moan for him, begged someone else to commit suicide and show him the way, and belaboured himself for his cowardice, saying: ‘To live, is shame and disgrace’, and then, in Greek: ‘it’s unworthy of Nero, unworthy – we should be ever-resolute – rouse yourself!’

By now the cavalry were approaching with orders to take him alive. When he heard them, he quoted Homer in a quavering voice:

‘Listen, I hear the sound now of galloping horses!’

Then, with the help of Epaphroditus, his private secretary, he plunged a dagger into his throat, and was already half-dead when a centurion entered, and feigning to have brought aid, staunched the wound with his cloak, Nero gasping: ‘Too late: yet, how loyal!’ With these words he died, his eyes glazing and starting from their sockets, to the horror of all who saw it.

He had forced his companions to promise that, whatever occurred, no one should sever his head from his body, and to contrive somehow that his corpse be given whole to the pyre. This was granted by Icelus, Galba’s freedman, who had just been released from the prison to which he had been committed at news of Galba’s revolt.

Book Six: L His Funeral

Nero was laid on the pyre, dressed in the gold-embroidered white robes he had worn on New Year’s Day. The funeral arrangements cost two thousand gold pieces. His old nurses, Egloge and Alexandria, accompanied by Acte his mistress, laid his ashes to rest in the family tomb of the Domitii on the summit of the Pincian Hill, which can be seen from the Campus Martius. The sarcophagus, of porphyry, was enclosed by a balustrade of stone from Thasos, with an altar of marble from Luna standing above.

Book Six: LI His Appearance, Health and Mode of Dress

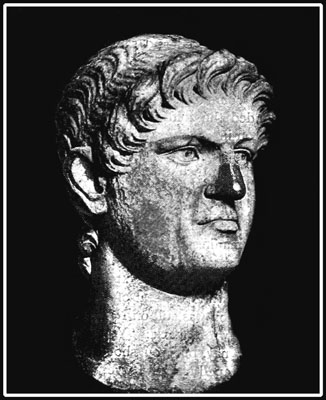

Nero was of average height, his skin mottled and his body malodorous. His hair was light blond, his features regular rather than attractive, with blue somewhat weak eyes. He had a thick neck, protruding belly, and spindly legs. His health was sound, and despite indulging in every kind of sensual excess, he was only ill on three occasions during his fourteen-year reign, and even then he did not abstain from drinking wine or from any other habit. He was shameless in personal appearance and dress having his hair set in tiered curls, and during his Greek travels letting it grow long enough to hang down his back. He often appeared in public in a loose tunic, with a scarf about his neck, and slippers on his feet.

Book Six: LII His Knowledge of the Arts