La Vita Nuova

‘The New Life’ of Dante Alighieri

Sections I to X

Listen to audio-book edition sample:

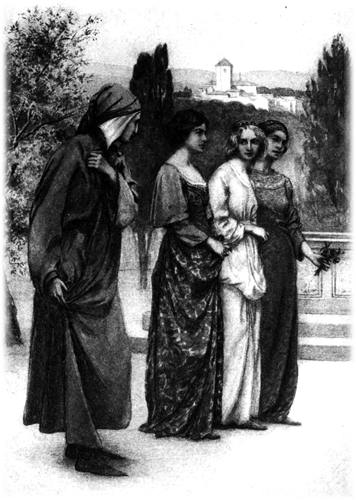

Frontispiece to the Ellis and Elvey 1899 edition of the Dante Gabriel Rossetti translation of “La Vita Nuova” The Open Library

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

In Memory of Jean (1922-2001)

Contents

- I Introduction

- II The first meeting with Beatrice

- III Years later she greets him

- IV The effects of Love on him

- V The screen lady

- VI He composes the serventese of the sixty ladies

- VII The screen lady’s departure

- VIII Dante’s poem on the death of Beatrice’s companion

- IX Dante’s journey: the new screen lady

- X Beatrice refuses to greet him

- Index to the First Lines of the Poems

I Introduction

I Introduction

In that part of the book of my memory before which little can be read, there is a heading, which says: ‘Incipit vita nova: Here begins the new life’. Under that heading I find written the words that it is my intention to copy into this little book: and if not all, at least their essence.

‘Dante (Study for Dante's Dream)’ - Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882)

II The first meeting with Beatrice

II The first meeting with Beatrice

Nine times already since my birth the heaven of light had almost revolved to the self-same point when my mind’s glorious lady first appeared to my eyes, she who was called by many Beatrice (‘she who confers blessing’), by those who did not know what it meant to so name her. She had already lived as long in this life as in her time the starry heaven had moved east the twelfth part of one degree, so that she appeared to me almost at the start of her ninth year, and I saw her almost at the end of my ninth. She appeared dressed in noblest colour, restrained and pure, in crimson, tied and adorned in the style that then suited her very tender age.

At that moment I say truly that the vital spirit, that which lives in the most secret chamber of the heart began to tremble so violently that I felt it fiercely in the least pulsation, and, trembling, it uttered these words: ‘Ecce deus fortior me, qui veniens dominabitur michi: Behold a god more powerful than I, who, coming, will rule over me.’ At that moment the animal spirit, that which lives in the high chamber to which all the spirits of the senses carry their perceptions, began to wonder deeply at it, and, speaking especially to the spirit of sight, spoke these words: ‘Apparuit iam beatitudo vestra: Now your blessedness appears.’ At that moment the natural spirit, that which lives in the part where our food is delivered, began to weep, and weeping said these words: ‘Heu miser, quia frequenter impeditus ero deinceps!: Oh misery, since I will often be troubled from now on!’

From then on I say that Amor governed my soul, which was so soon wedded to him, and began to acquire over me such certainty and command, through the power my imagination gave him, that I was forced to carry out his wishes fully. He commanded me many times to discover whether I might catch sight of this most tender of angels, so that in my boyhood I many times went searching, and saw her to be of such noble and praiseworthy manners, that certainly might be said of her those words of the poet Homer: ‘She did not seem to be the daughter of a mortal man, but of a god’. And though her image, that which was continually with me, was a device of Amor’s to govern me, it was nevertheless of so noble a virtue that it never allowed Amor to rule me without the loyal counsel of reason in all those things where such counsel was usefully heard.

But because it might seem fiction to some to dwell on the passions and actions of such tender years, I will leave them, and passing over many things that might be derived from the sample from which these were taken, I will come to those words that are written in my memory under more important heads.

III Years later she greets him

III Years later she greets him

When so many days had passed that exactly nine years were completed since the appearance of this most gracious being I have written of above, it happened, on the last of these days, that this marvellous lady appeared to me, dressed in the whitest of white, between two gracious ladies who were of greater age: and passing through a street she turned her eyes to the place where I stood greatly fearful, and, with her ineffable courtesy, that is now rewarded in a greater sphere, she greeted me so virtuously, so much so that I saw then to the very end of grace. The hour at which her so sweet greeting welcomed me was exactly the ninth of that day, and because it was the first time that her words deigned to come to my ears, I found such sweetness that I left the crowd as if intoxicated, and I returned to the solitude of my own room, and fell to thinking of this most gracious one.

And thinking of her a sweet sleep overcame me, in which a marvellous vision appeared to me: so that it seemed I saw in my room a flame-coloured nebula, in the midst of which I discerned the shape of a lord of fearful aspect to those who gazed on him: and he appeared to me with such joy, so much joy within himself, that it was a miraculous thing: and in his speech he said many things, of which I understood only a few: among them I understood this: ‘Ego dominus tuus: I am your lord.’

It seemed to me he held a figure sleeping in his arms, naked except that it seemed to me to be covered lightly with a crimson cloth: gazing at it very intently I realised it was the lady of the greeting, she who had deigned to greet me before that day. And in one of his hands it seemed to me that he held something completely on fire, and he seemed to say to me these words: ‘Vide cor tuum: Look upon your heart. And when he had stood for a while, he seemed to wake her who slept: and by his art was so forceful that he made her eat the thing that burned in her hand, which she ate hesitantly.

‘The Salutation of Beatrice’ - Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882)

After waiting for a little while his joy was all turned to bitter grief: and, so grieving, he gathered that lady in his arms, and it seemed to me that he ascended with her towards heaven: from which I experienced such anguish that my light sleep could not endure it, and so was broken, and was dispersed. And immediately I began to reflect, and discovered that the hour in which this vision appeared to me was the fourth of that night: so as to be manifestly clear, it was the first hour of the nine last hours of night.

Thinking to myself about what had appeared to me, I decided to make it known to many who were famous poets of the time: and as it was a fact that I had already gained for myself to some extent the art of speaking words in rhyme, I decided to shape a sonetto, in which I would greet all those faithful to Amor: and begging them to interpret my vision, I wrote for them what I had seen in my sleep. And then I began this sonetto, that which begins: A ciascun´alma presa e gentil core.

To every captive soul and gentle heart

into whose sight this present speech may come,

so that they might write its meaning for me,

greetings, in their lord’s name, who is Love.

Already a third of the hours were almost past

of the time when all the stars were shining,

when Amor suddenly appeared to me

whose memory fills me with terror.

Joyfully Amor seemed to me to hold

my heart in his hand, and held in his arms

my lady wrapped in a cloth sleeping.

Then he woke her, and that burning heart

he fed to her reverently, she fearing,

afterwards he went not to be seen weeping.

This sonnet is divided in two parts: so that in the first part I greet and demand reply, in the second I signify what must be replied to. The second part begins with: ‘Già eran: Already (a third)’. There were replies from many to this sonnet and of differing interpretation: among those who replied was one whom I call the foremost of my friends, and he wrote then a sonnet, that which begins: ‘Vedeste, al mio parere, onne valore: You saw, it seems to me, every virtue.’

And this was virtually the beginning of the friendship between him and myself, when he knew that it was I who had made the request of him. The true meaning of that dream was not then seen by anyone, but now it is clear to the most unknowing.

IV The effects of Love on him

IV The effects of Love on him

From that vision onwards my natural spirit began to be obstructed in its operation, because my spirit was completely dedicated to thoughts of that most graceful one: so that in a little while I reached so frail and debilitated a condition, that many friends were anxious about my appearance: and many full of malice put themselves about to know about me things that I wished above all to hide from others. And I, aware of the ill requests they made about me, replied, by the will of Amor, who directed me in accordance with reason’s counsel, that it was Amor who had brought me to this.

I spoke of Amor, because I bore so many signs of him in my face, that they could not be concealed. And, when they asked me: ‘For whom has Amor so distressed you?’ gazing at them I smiled, and said nothing to them.

V The screen lady

V The screen lady

One day it chanced that this most graceful lady was seated in a place where words were heard concerning the queen of glory, and I was in a position from which I could see my blessedness: and between her and me in a straight line sat a gentle lady of most pleasant appearance, who looked at me frequently, amazed by my gaze, which seemed to end with her.

Then many were aware of her look, and in a while were certain of it, so that, in leaving the place, I heard it spoken after me: ‘See how that lady has distressed his person’ and being named, I realised that he was speaking of her who had been placed in the straight line that started at the most graceful Beatrice, and ended at my eyes. Then I was greatly comforted, assured that my secret had not been revealed to others by my gaze that day.

And immediately I thought of making of this lady a screen before the truth: and I pretended to it so often in so short a time that my secret was believed known by most of the people who speculated about me. I screened myself with this lady for some months and years: and to better allow others to believe it, I created certain little things for her in verse, which it is not my intention to write down, unless they mainly set out to treat of that most graceful Beatrice: and therefore I will forget them all except one that I wrote which can be seen to be in praise of her.

VI He composes the serventese of the sixty ladies

VI He composes the serventese of the sixty ladies

I say that during the time that lady was the screen for so great a love, so great on my part, there came to me the will to want to record the name of that graceful one and accompany it with many names of women, and especially the name of the gentle lady. And I took the names of the sixty most beautiful ladies of the city, in which my lady had been placed by the highest Lord, and I composed a letter in the form of a serventese, a poem of praise, which I will not write down: and I would not have mentioned it if it were not to say that composing it, a marvellous thing occurred, that the name of my lady was not allowed to stand in any other place than that of ninth among the names of those ladies.

VII The screen lady’s departure

VII The screen lady’s departure

The lady by means of whom I had concealed my wishes for so long had to leave the city I mentioned above, and travel to a distant region: because of this, I, greatly troubled by the loss of the beautiful defence I had acquired, was much discomforted, more than I myself would have believed before. And thinking that if I did not write sorrowfully enough about her departure people would more quickly be aware of my pretence, I decided to create a lament as a sonetto: which I will write down, since my lady was the direct cause for certain words that are in the sonetto, as is apparent to anyone who understands it. And so I wrote this sonetto, which begins: ‘O voi che par la via.’

O you who on the way of Love go by,

listen and see

if there is any grief, as grave as mine:

and I beg you only to suffer me to be heard,

and then reflect

whether I am not the tower and the key of every torment.

Amor, indeed not for my slight worth

but through his nobility

placed me in a life so sweet and gentle,

that often I would hear it said behind me:

‘God, for what virtue

does this heart own so much delight?’

Now I have lost all my eloquence

which flowed so from love’s treasure:

and I am grown so poor

in a way that speech barely comes to me.

So that I desire to be like one

who to conceal his poverty through shame,

shows joy outwardly,

and within my heart am troubled and weep.

This sonetto has two main parts: in the first I mean to call on those loyal to Amor in the words that Jeremiah the prophet spoke: ‘O vos omnes qui transitis per viam, attendite et videte si est dolor sicut meus: O all you who pass this way, listen and see, if there is any grief like mine,’ and to beg them to allow me to be heard: in the second part I say where Amor had placed me, with an intention opposite to that which the outer extremes of the sonetto reveal, and I tell what I have lost. The second part begins at: ‘Amor non gia: Amor indeed, not.’

VIII Dante’s poem on the death of Beatrice’s companion

VIII Dante’s poem on the death of Beatrice’s companion

After the departure of that gentle lady it pleased the lord of angels to call to his glory a woman, young and of very gentle aspect, who had been a great grace to the city I spoke of: whose lifeless body I saw lying amongst a crowd of ladies, who were weeping most piteously. Then, remembering that I had seen her before accompanying the most graceful lady, I could not hold back tears: so weeping I decided to speak a few words about her death, in tribute to the fact that I had once seen her with my lady.

And I touched on this a little in the last part of the words I wrote, as is clearly apparent to those who understand. And then I wrote these two sonetti, the first of which begins: ‘Piangete, amanti,’ and the second: ‘Morte villana.’

Weep you lovers, since Love is also weeping,

and hear the reason that makes him full of tears.

Amor feels ladies calling on Pity,

revealing a bitter sorrow in their eyes,

because the villain Death in gentle heart

has set his cruel machinations,

destroying what the world has given praise to

in gentle lady, all except honour.

Hear how Amor has honoured her,

who in his true form I saw lamenting

bending above the lifeless image:

and often gazing upwards to the heavens,

where the gentle soul had already fled,

that was a lady of such joyful semblance.

This first sonetto is divided into three parts: in the first part I call on and beg those loyal to Amor to weep and I say that their lord is weeping, and I say ‘hear the reason that makes him full of tears’ so that they might be more ready to listen to me: in the second I narrate the cause: in the third I speak of the honour that Amor paid this lady. The second part begins with: ‘Amor sente: Amor feels,’ the third with: ‘Audite: Hear.’

Death the villain, enemy of pity,

ancient mother of sorrows,

justice incontestable and grave,

since you have given matter for the grieving heart

because of which I go pensive,

my tongue will weary blaming you.

And if by grace I can make you beg,

I will be forced to speak

of your guilt for all vile evils,

not because they are unknown to people,

but to make more extreme

those who go to love for nurture.

From the world you have driven courtesy

and virtue, that causes praise in women:

in joyful youthfulness

you have lightly destroyed loveliness.

I will not tell you who this lady is

except by naming her true qualities.

He who does not deserve grace

may no more hope to have her company.

This sonetto is divided into four parts: in the first part I call on Death by certain of his true names: in the second, speaking to him, I tell the reason why he moves me to blame him: in the third I revile him: in the fourth I turn to speak to an unspecified person, though he is specified by my intention. The second begins with: ‘poi che hai data: since you have given’: the third with: ‘E s’io di grazia: And if by grace’: the fourth with: ‘Chi non merta salute: He who does not deserve grace.’

‘The Pious Lady on the Right (Study for Dante's Dream)’ - Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882)

IX Dante’s journey: the new screen lady

IX Dante’s journey: the new screen lady

A few days after the death of this lady something happened which forced me to leave the above city and travel to that region where the gentle lady was who had been my screen, though the destination of my journey was not as far as where she was. And although I was in the company of many, at least outwardly, the travelling displeased me so much that my sighs could scarcely relieve the anguish my heart felt, because I distanced myself from my blessedness.

And so the sweetest lord who ruled over me through the virtue of my most graceful lady appeared in my imagination like a traveller simply dressed, in coarse cloth. He seemed to me dejected, and gazed at the ground, except when he seemed to me to turn his eyes towards a beautiful and clearest of running streams, which ran along the way I was going.

It seemed to me that Amor called my name and said these words to me: ‘I come from that lady who has long been your screen, and I know that her return will not be for some time, and so I have with me that heart which I made you leave with her, and I carry it to a lady who will become your defence, as she was.’ And he named her name to me, so that I knew her well. ‘But take care, if you repeat any thing of these words I have mentioned to you, that it be in such a way that no one discerns by them the false love you have shown, and which you must show to another.’

And speaking these words he departed my imagination quite suddenly for the most part, as it seemed that Amor merged himself with me: and somewhat changed in my appearance, I rode on that day thinking deeply and accompanied by many sighs. After that day I began this sonetto, which begins: ‘Cavalcando’.

Riding the other day along a track,

thinking of the journey I disliked,

I found Amor in the middle of the way

in the simple dress of a traveller.

In his countenance, wretched, he seemed to me

as if he had lost a ruler-ship:

and he came sighing thoughtfully

not seeing anyone, with head bowed low.

When he saw me he called me by name,

and said: ‘I come from a distant place

from where your heart was according to my wish:

and bring it back to serve new pleasures.’

Then I took from him so great a part

that he vanished, and I did not see how.

This sonetto has three parts: in the first I say how I met Amor and how he seemed to me: in the second I say what he said to me, thought not completely for fear of revealing my secret: in the third I say how he vanished. The second begins with: ‘Quando mi vide: When he saw me’: the third: ‘Allora presi: Then I took.’

X Beatrice refuses to greet him

X Beatrice refuses to greet him

After my return I set out to search for the lady that my lord had named to me on the road of sighs: and in order to speak briefly of it, I say that in a short time I made her my screen, so much so that too many people speculated about it, beyond the bounds of courtesy: because of that it often made me greatly pensive. And for that reason, namely the outrageous rumours that seemed to viciously defame me, that most graceful being, she who was the slayer of all vices and the queen of all virtue, passing by, refused me her sweet greeting, in which all my blessedness existed.

And leaving the present subject somewhat, I want to make clear how her greeting worked within me virtuously.

Index to the First Lines of the Poems

- To every captive soul and gentle heart

- O you who on the way of Love go by,

- Weep you lovers, since Love is also weeping,

- Death the villain, enemy of pity,

- Riding the other day along a track,