Dante: The Divine Comedy

Inferno Cantos XXIX-XXXIV

Authored and translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2000, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Inferno Canto XXIX:1-36 Geri del Bello

- Inferno Canto XXIX:37-72 The Tenth Chasm: The Falsifiers

- Inferno Canto XXIX:73-99 Griffolino and Capocchio

- Inferno Canto XXIX:100-120 Griffolino’s narrative

- Inferno Canto XXIX:121-139 The Spendthrift Brigade

- Inferno Canto XXX:1-48 Schicci and Myrrha

- Inferno Canto XXX:49-90 Adam of Brescia

- Inferno Canto XXX:91-129 Sinon: Potiphar’s wife

- Inferno Canto XXX:130-148 Virgil reproves Dante

- Inferno Canto XXXI:1-45 The Giants that guard the central pit

- Inferno Canto XXXI:46-81 Nimrod

- Inferno Canto XXXI:82-96 Ephialtes

- Inferno Canto XXXI:97-145 Antaeus

- Inferno Canto XXXII:1-39 The Ninth Circle: The frozen River Cocytus

- Inferno Canto XXXII:40-69 The Caïna: The degli Alberti: Camicion

- Inferno Canto XXXII:70-123 The Antenora: Bocca degli Abbati

- Inferno Canto XXXII:124-139 Ugolino and Ruggieri

- Inferno Canto XXXIII:1-90 Count Ugolino’s story

- Inferno Canto XXXIII:91-157 Friar Alberigo and Branca d’Oria

- Inferno Canto XXXIV:1-54 The Judecca: Satan

- Inferno Canto XXXIV:55-69 Judas: Brutus: Cassius

- Inferno Canto XXXIV:70-139 The Poets leave Hell

Inferno Canto XXIX:1-36 Geri del Bello

The multitude of people, and the many wounds, had made my eyes so tear-filled, that they longed to stop and weep, but Virgil said to me: ‘Why are you still gazing? Why does your sight still rest, down there, on the sad, mutilated shadows? You did not do so at the other chasms. Think, if you wish to number them, that the valley circles twenty-two miles, and the moon is already underneath our feet. The time is short now, that is given us, and there are other things to view, than those you see.’

“Virgil said to me: ‘Why are you still gazing? Why does your sight still rest, down there, on the sad, mutilated shadows?’” (Inferno XXIX: 4—6)

I replied, then: ‘Had you noticed the reason why I looked, perhaps you might still have allowed me to stay.’ Meanwhile, the guide was moving on, and I went behind him, making my reply, and adding, now: ‘In the hollow where I held my gaze, I believe a spirit, of my own blood, laments the guilt that costs so greatly here.’ Then the Master said: ‘Do not let your thoughts be distracted by him: attend to something else: let him stay there. I saw him point to you, at the foot of the little bridge, and threaten, angrily, with his finger: and I heard them call him Geri del Bello. You were so entangled, then, with him who once held Altaforte, that you did not look that way, so he departed.’

I said: ‘Oh, my guide, his violent murder made him indignant, not yet avenged on his behalf, by any that shares his shame: therefore, I guess, he went away, without speaking to me: and, by that, has made me pity him the more.’

Inferno Canto XXIX:37-72 The Tenth Chasm: The Falsifiers

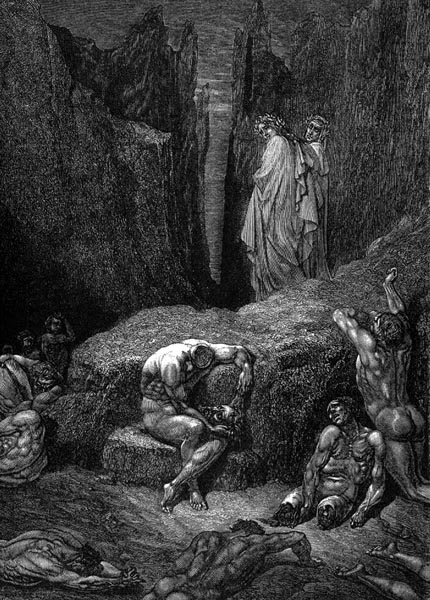

So we talked, as far as the first place on the causeway that would have revealed the next valley, right to its floor, if it had been lighter. When we were above the last cloister of Malebolge, so that its lay brothers could be seen, many groans pierced me, whose arrows were barbed with pity, at which I covered my ears with my hands. Such pain there was, as there would be, if the diseases in the hospitals of Valdichiana, Maremma and Sardinia, between July and September, were all rife in one ditch: a stench arose from it, such as issues from putrid limbs.

We descended on the last bank of the long causeway, again on the left, and then my sight was clearer, down to the depths, where infallible Justice, the minister of the Lord on high, punishes the falsifiers that it accounts for here. I do not think it would have been a greater sadness to see the people of plague-ridden Aegina, when the air was so malignant, that every animal, even the smallest worm, was killed, and afterwards, as Poets say, for certain, the ancient race was restored from the seed of ants, than it was to see the spirits languishing in scattered heaps through that dim valley. This one lay on its belly, that, on the shoulders of the other, and some were crawling along the wretched path.

Step by step we went, without a word, gazing at, and listening to, the sick who could not lift their bodies.

“…then my sight was clearer, down to the depths, where infallible Justice, the minister of the Lord on high, punishes the falsifiers that it accounts for here.” (Inferno XXIX: 52—56)

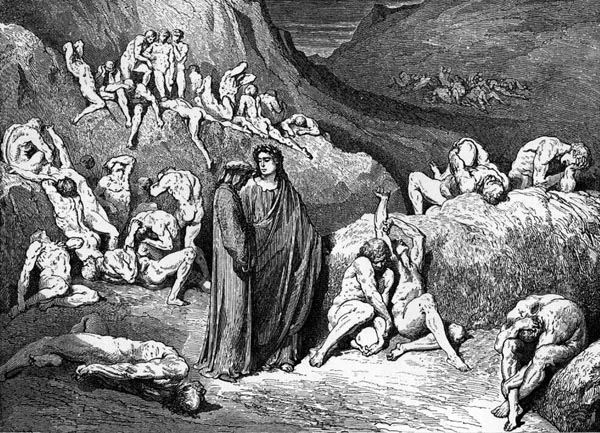

Inferno Canto XXIX:73-99 Griffolino and Capocchio

I saw two sitting, leaning on each other, as one pan is leant to warm against another: they were marked with scabs from head to foot, and I never saw a stable lad his master waits for, or one who stays awake unwillingly, use a currycomb as fiercely, as each of these two clawed himself with his nails, because of the intensity of their itching, that has no other relief.

And so the nails dragged the scurf off, as a knife does the scales from bream, or other fish with larger scales. My Guide began to speak: ‘O you, who strip your chain-mail with your fingers, and often make pincers of them, tell us if there is any Latian among those here, inside: and may your nails be enough for that task for eternity.’ One of them replied, weeping: ‘We are both Latians, whom you see so mutilated here, but who are you who enquire of us? And the guide said: ‘I am one, who with this living man, descends from steep to steep, and mean to show him Hell.’

Then the mutual prop broke, and each one turned, trembling, towards me, along with others that heard him, by the echo.

“And so the nails dragged the scurf off, as a knife does the scales from bream, or other fish with larger scales.” (Inferno XXIX: 79—81)

Inferno Canto XXIX:100-120 Griffolino’s narrative

The good Master addressed me directly, saying: ‘Tell them what you wish,’ and I began as he desired: ‘So that your memory will not fade, from human minds, in the first world, but will live for many suns, tell us who you are, and of what race. Do not let your ugly and revolting punishment make you afraid to reveal yourselves to me.’

The one replied: ‘I was Griffolino of Arezzo, and Albero of Siena had me burned: but what I died for did not send me here. It is true I said to him, jesting, “I could lift myself into the air in flight,” and he who had great desire and little brain, wished me to show him that art: and only because I could not make him Daedalus, he caused me to be burned, by one who looked on him as a son.

But to the last chasm of the ten, Minos, who cannot err, condemned me, for the alchemy I practised in the world.’

Inferno Canto XXIX:121-139 The Spendthrift Brigade

And I said to the poet: ‘Now was there ever a people as vain as the Sienese? Certainly not the French, by far.’ At which the other leper, hearing me, replied to my words: ‘What of Stricca, who contrived to spend so little: and Niccolo who first discovered the costly use of cloves, in that garden, Siena, where such seed takes root: and that company in which Caccia of Aciano threw away his vineyard, and his vast forest, and the Abbagliato showed his wit.

But so that you may know who seconds you like this against the Sienese, sharpen your eye on me, so that my face may reply to you: so you will see I am Capocchio’s shadow, who made false metals, by alchemy, and you must remember, if I know you rightly, how well I aped nature.’

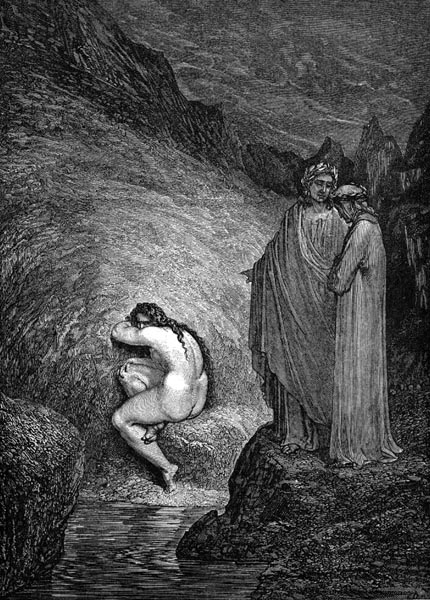

Inferno Canto XXX:1-48 Schicci and Myrrha

At the time when Juno was angry, as she had shown more than once, with the Theban race, because of Jupiter’s affair with Semele, she so maddened King Athamas, that, seeing his wife, Ino, go by, carrying her two sons in her arms, he cried: ‘Spread the hunting nets, so that I can take the lioness and her cubs, at the pass,’ and then stretched out his pitiless talons, snatching the one, named Learchus, and, whirling him round, dashed him against the rock: and Ino drowned herself, and her other burden, Melicertes. And after fortune had brought down the high Trojan pride, that dared all, so that Priam the king, and his kingdom were destroyed, Queen Hecuba, a sad, wretched captive, having witnessed the sacrifice of Polyxena, alone, on the sea-shore, when she recognised the body of her Polydorus, barked like a dog, driven out of her senses, so greatly had her sorrow racked her mind.

But neither Theban nor Trojan Furies were ever seen embodied so cruelly, in stinging creatures, or even less in human limbs, as I saw displayed in two shades, pallid and naked, that ran, biting, as a hungry pig does, when he is driven out of his sty. The one came to Capocchio, and fixed his tusks in his neck, so that dragging him along, it made the solid floor rasp his belly. And the Aretine, Griffolino, who was left, said to me, trembling: ‘That goblin is Gianni Schicci, and he goes, rabidly, mangling others like that.’ I replied: ‘Oh, be pleased to tell us who the other is, before it snatches itself away, and may it not plant its teeth in you.’

“‘That goblin is Gianni Schicci, and he goes, rabidly, mangling others like that.’” (Inferno XXX: 33, 34)

And he to me: ‘That is the ancient spirit of incestuous Myrrha, who loved her father, Cinyras, with more than lawful love. She came to him, and sinned, under cover of another’s name, just as the one who is vanishing there, undertook to disguise himself as Buoso Donati, so as to gain the mare, called the Lady of the Herd, by forging a will, and giving it legal form.’

When the furious pair, on whom I had kept my eye, were gone, I turned to look at the other spirits, born to evil.

“‘That is the ancient spirit of incestuous Myrrha…’” (Inferno XXX: 38, 39)

Inferno Canto XXX:49-90 Adam of Brescia

I saw one, who would have been shaped like a lute, if he had only had his groin cut short, at the place where a man is forked. The heavy dropsy, that swells the limbs, with its badly transformed humours, so that the face does not match the belly, made him hold his lips apart, as the fevered patient does who, through thirst, curls one lip towards the chin, and the other upwards.

He said to us: ‘O you, who are exempt from punishment in this grim world (and why, I do not know), look and attend to the misery of Master Adam. I had enough of what I wished, when I was alive, and now, alas, I crave a drop of water. The little streams that fall, from the green hills of Casentino, down to the Arno, making cool, moist channels, are constantly in my mind, and not in vain, since the image of them parches me, far more than the disease, that wears the flesh from my face.

The rigid justice, that examines me, takes its opportunity from the place where I sinned, to give my sighs more rapid flight. That is Romena, where I counterfeited the coin of Florence, stamped with the Baptist’s image: for that, on earth, I left my body, burned. But if I could see the wretched soul of Guido here, or Alessandro, or Aghinolfo, their brother, I would not exchange that sight for Branda’s fountain. Guido is down here already, if the crazed spirits going round speak truly, but what use is it to me, whose limbs are tied?

If I were only light enough to move, even an inch, every hundred years, I would already have started on the road, to find him among this disfigured people, though it winds around eleven miles, and is no less than half a mile across. Because of them I am with such a crew: they induced me to stamp those florins that were adulterated, with three carats alloy.’

Inferno Canto XXX:91-129 Sinon: Potiphar’s wife

I said to him: ‘Who are those abject two, lying close to your right edge, and giving off smoke, like a hand, bathed, in winter? He replied: ‘I found them here, when I rained down into this pound, and they have not turned since then, and may never turn I believe.

One is the false wife who accused Joseph. The other is lying Sinon, the Greek from Troy. A burning fever makes them stink so strongly.’ And Sinon, who perhaps took offence at being named so blackly, struck Adamo’s rigid belly with his fist, so that it resounded, like a drum: and Master Adam struck him in the face with his arm, that seemed no softer, saying to him: ‘I have an arm free for such a situation, though I am kept from moving by my heavy limbs.’ At which Sinon answered: ‘You were not so ready with it, going to the fire, but as ready, and readier, when you were coining.’ And he of the dropsy: ‘You speak truth in that, but you were not so truthful a witness, there, when you were questioned about the truth at Troy.’

‘If I spoke falsely, you falsified the coin,’ Sinon said, ‘and I am here for the one crime, but you for more than any other devil.’ He who had the swollen belly answered: ‘Think of the Wooden Horse, you liar, and let it be a torment to you that all the world knows of it.’ The Greek replied: ‘Let the thirst that cracks the tongue be your torture, and the foul water make your stomach a barrier in front of your eyes.’ Then the coiner: ‘Your mouth gapes wide as usual, to speak ill. If I have a thirst, and moisture swells me, you have the burning, and a head that hurts you: and you would not need many words of invitation, to lap at the mirror of Narcissus.’

Inferno Canto XXX:130-148 Virgil reproves Dante

I was standing, all intent on hearing them, when the Master said to me: ‘Now, keep gazing much longer, and I will quarrel with you!’ When I heard him speak to me in anger, I turned towards him, with such a feeling of shame that it comes over me again, as I only think of it. And like someone who dreams of something harmful to them, and dreaming, wishes it were a dream, so that they long for what is, as if it were not; that I became, who, lacking power to speak, wished to make an excuse, and all the while did so, not thinking I was doing it.

My Master said: ‘Less shamefacedness would wash away a greater fault than yours, so unburden yourself of sorrow, and know that I am always with you, should it happen that fate takes you, where people are in similar conflict: since the desire to hear it, is a vulgar desire.’

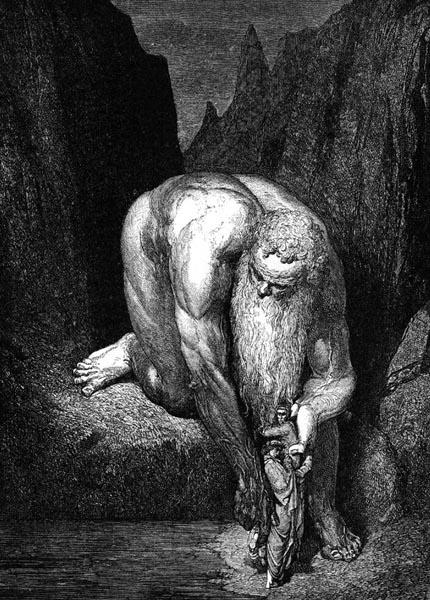

Inferno Canto XXXI:1-45 The Giants that guard the central pit

One and the same tongue at first wounded me, so that it painted both my cheeks with blushes, and then gave out the ointment for the wound. So I have heard the spear of Achilles, and his father Peleus, was the cause first of sadness, and then of a healing gift.

We turned our back on the wretched valley, crossing without a word, up by the bank that circles round it. Here was less darkness than night and less light than day, so that my vision showed only a little in front: but I heard a high-pitched horn sound, so loudly, that it would have made thunder seem quiet: it directed my eyes, that followed its passage back, straight to a single point. Roland did not sound his horn so fiercely, after the sad rout, when Charlemagne had lost the holy war, at Roncesvalles.

I had kept my head turned for a while in that direction, when I seemed to make out many high towers, at which I said: ‘Master, tell me what city this is?’ And he to me: ‘Because your eyes traverse the darkness from too far away, it follows that you imagine wrongly. You will see, quite plainly, when you reach there, how much the sense is deceived by distance, so press on more strongly.’ Then he took me, lovingly, by the hand, and said: ‘Before we go further, so that the reality might seem less strange to you, know that they are Giants, not towers, and are in the pit, from the navel downwards, all of them, around its bank.’

As the eye, when a mist is disappearing, gradually recreates what was hidden by the vapour thickening the air, so, while approaching closer and closer to the brink, piercing through that gross, dark atmosphere, error left me, and my fear increased. As Montereggione crowns its round wall with towers, so the terrible giants, whom Jupiter still threatens from the heavens, when he thunders, turreted with half their bodies the bank that circles the well.

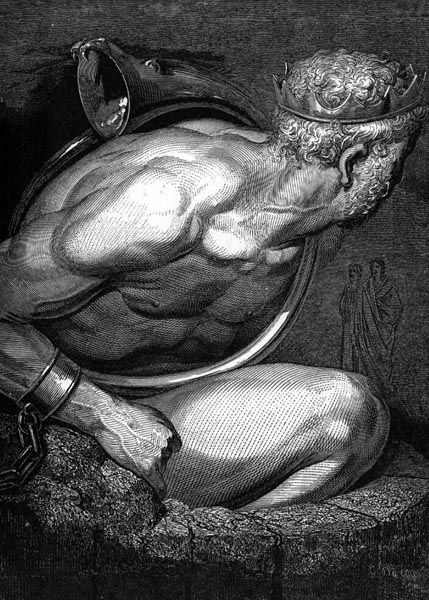

Inferno Canto XXXI:46-81 Nimrod

And I already saw the face of one, the shoulders, chest, the greater part of the belly, and the arms down both sides. When nature abandoned the art of making creatures like these, she certainly did well by removing such killers from warfare, and if she does not repent of making elephants and whales, whoever looks at the issue subtly, considers her more prudent and more right in that, since where the instrument of mind is joined to ill will and power, men have no defence against it.

His face seemed to me as long and large as the bronze pine-cone, in front of St Peter’s in Rome, and his other features were in proportion, so that the bank that covered him from the middle onwards, revealed so much of him above that three Frieslanders would have boasted in vain of reaching his hair, since I saw thirty large hand-spans of him down from the place where a man pins his cloak.

The savage mouth, for which no sweeter hymns were fit, began to rave: ‘Rafel mai amech sabi almi.’ And my guide turning to him, said: ‘Foolish spirit, stick to your hunting-horn, and vent your breath through that, when rage or some other passion stirs you. Search round your neck, O confused soul, and you will find the belt where it is slung, and see that which arcs across your huge chest.’ Then he said to me: ‘He declares himself. This is Nimrod, through whose evil thought, one language is not still used, throughout the whole world. Let us leave him standing here, and not speak to him in vain: since every language, to him, is like his to others, that no one understands.’

“‘Foolish spirit, stick to your hunting-horn, and vent your breath through that, when rage or some other passion stirs you.’” (Inferno XXXI: 64—66)

Inferno Canto XXXI:82-96 Ephialtes

So we went on, turning to the left, and, a crossbow-shot away, we found the next one, far larger and fiercer. Who and what the power might be that bound him, I cannot say, but he had his right arm pinioned behind, and the other in front, by a chain that held him tight, from the neck down, and, on the visible part of him, reached its fifth turn.

My guide said: ‘This proud spirit had the will to try his strength against high Jupiter, and so has this reward. Ephialtes is his name, and he made the great attempt, when the Giants made the gods fear, and the arms he shook then, now, he never moves.’

“‘This proud spirit had the will to try his strength against high Jupiter…’” (Inferno XXXI: 82—84)

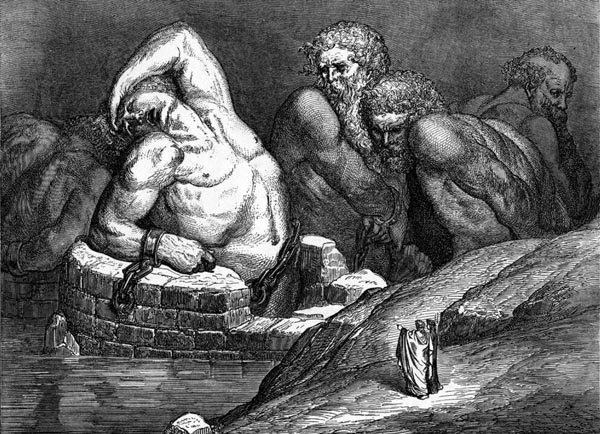

Inferno Canto XXXI:97-145 Antaeus

And I said to him: ‘If it were possible, I would wish my eyes to light on vast Briareus.’ To which he replied: ‘You will see Antaeus, nearby, who speaks and is unchained, and will set us down in the deepest abyss of guilt. He whom you wish to see is far beyond, and is formed and bound like this one, except he seems more savage in his features.’ No huge earthquake ever shook a tower, as violently as Ephialtes promptly shook himself. Then I feared death more than ever, and the fear alone would have been enough to cause it, had I not seen his chains.

We then went further on, and reached Antaeus, who projected twenty feet from the pit, not including his head. The Master spoke: ‘O you, who, of old, took a thousand lions for your prey, in the fateful valley, near Zama, that made Scipio heir to glory, when Hannibal retreated with his army; you, through whom, it might still be believed, the Giant sons of Earth would have overcome the gods, if you had been at the great war with your brothers; set us down, and do not be shy to do it, where the cold imprisons the River Cocytus, in the Ninth Circle.

Do not make us ask Tityos or Typhon. Bend, and do not curl your lips in scorn: this man can give that which is longed for, here: he can refresh your fame on earth, since he is alive, and still expects long life, if grace does not call him to her before his time.’ So the Master spoke, and Antaeus quickly stretched out both hands, from which Hercules of old once felt the power, and seized my guide. Virgil when he felt his grasp, said to me: ‘Come here, so that I may carry you.’ Then he made one bundle of himself and me.

To me, who stood watching to see Antaeus stoop, he seemed as the leaning tower at Bologna, the Carisenda, appears to the view, under the leaning side, when a cloud is passing over it, and it hangs in the opposite direction. It was such a terrible moment I would have wished to have gone by another route, but he set us down gently in the deep, that swallowed Lucifer and Judas, and did not linger there, bent, but straightened himself, like a mast raised in a boat.

“…but he set us down gently in the deep, that swallowed Lucifer and Judas…” (Inferno XXXI: 133—135)

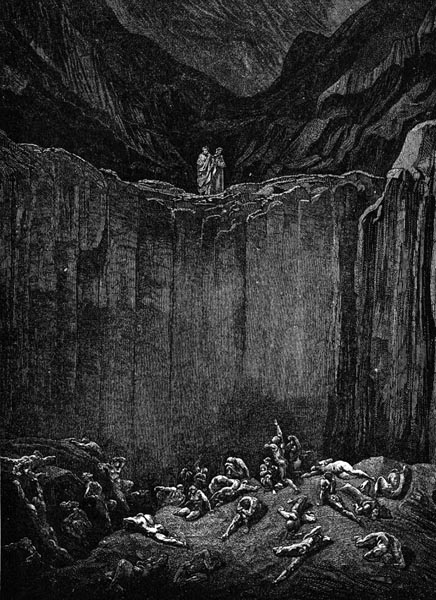

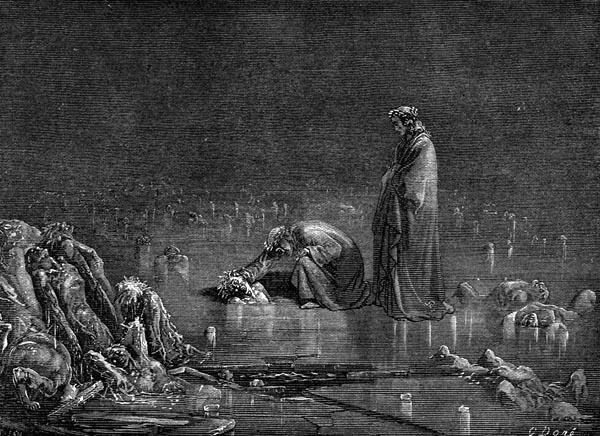

Inferno Canto XXXII:1-39 The Ninth Circle: The frozen River Cocytus

If I had words, rough and hoarse enough, to fit the dismal chasm, on which all the other rocky cliffs weigh, and converge, I would squeeze out the juice of my imagination more completely: but since I have not, I bring myself, not without fear, to describe the place: to tell of the pit of the Universe is not a task to be taken up in play, nor in a language that has words like ‘mother’ and ‘father’. But may the Muses, those Ladies, who helped Amphion shut Thebes behind its walls, aid my speech, so that my words may not vary from the truth.

O you people, created evil beyond all others, in this place that is hard to speak of, it were better if you had been sheep or goats here on earth! When we were down, inside the dark well, beneath the Giants’ feet, and much lower, and I was still staring at the steep cliff, I heard a voice say to me: ‘Take care as you pass, so that you do not tread, with your feet, on the heads of the wretched, weary brothers.’ At which I turned, and saw a lake, in front of me and underneath my feet, that, because of the cold, appeared like glass not water.

“‘Take care as you pass, so that you do not tread, with your feet, on the heads of the wretched, weary brothers.’” (Inferno XXXII: 20—22)

The Danube, in Austria, never formed so thick a veil for its winter course, nor the Don, far off under the frozen sky, as was here: if Mount Tambernic in the east, or Mount Pietrapana, had fallen on it, it would not have even creaked at the margin. And as frogs sit croaking with their muzzles above water, at the time when peasant women often dream of gleaning, so the sad shadows sat, in the ice, livid to where the blush of shame appears, chattering with their teeth, like storks.

Each one held his face turned down: the cold is witnessed, amongst them, by their mouths: and their sad hearts, by their eyes.

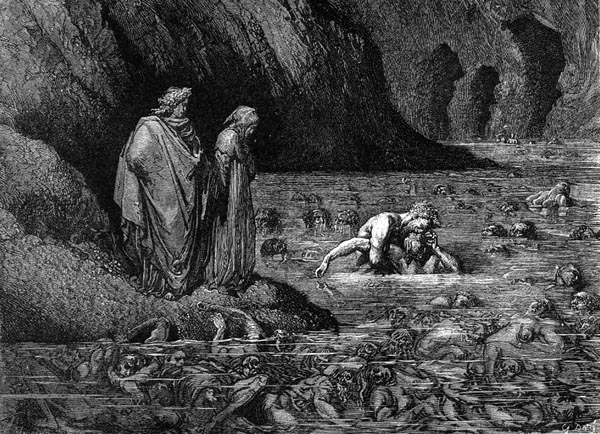

Inferno Canto XXXII:40-69 The Caïna: The degli Alberti: Camicion

When I had a looked around awhile, turning to my feet, I saw two, so compressed together, that the hair of their heads was intermingled. I said: ‘Tell me, you, who press your bodies together so: who are you?’ And they twisted their necks up, and when they had lifted their faces towards me, their eyes, which were only moist, inwardly, before, gushed at the lids, and the frost iced fast the tears, between them, and sealed them up again. No vice ever clamped wood to wood as firmly: so that they butted one another like two he-goats, overcome by such rage.

And one, who had lost both ears to the cold, with his face still turned down, said: ‘Why are you staring at us, so fiercely? If you want to know who these two are, they are the degli Alberti, Allesandro and Napoleone: the valley where the Bisenzio runs down, was theirs and their father Alberto’s. They issued from one body, and you can search the whole Caïna, and will not find shades more worthy of being set in ice: not even Mordred, whose chest and shadow, were pierced, at one blow, by his father’s, King Arthur’s, lance: nor Focaccia: nor this one, who obstructs my face with his head, so that I cannot see further, who was named Sassol Mascheroni. If you are a Tuscan, now, you know truly what he was.

And so that you do not put me to more speech, know that I am Camicion de’ Pazzi, and am waiting for Carlino, my kinsman, to outdo me.’

Inferno Canto XXXII:70-123 The Antenora: Bocca degli Abbati

Afterwards I saw a thousand faces, made doglike by the cold, at which a trembling overcomes me, and always will, when I think of the frozen fords. And, whether it was will, or fate or chance, I do not know: but walking, among the heads, I struck my foot violently against one face. Weeping it cried out to me: ‘Why do you trample on me? If you do not come to increase the revenge for Montaperti, why do you trouble me?’

And I: ‘My Master, wait here for me, now, so that I can rid me of a doubt concerning him, then you can make as much haste as you please.’ The Master stood, and I said to that shade which still reviled me bitterly: ‘Who are you, who reproach others in this way?’ ‘No, who are you,’ he answered, ‘who go through the Antenora striking the faces of others, in such a way, that if you were alive, it would be an insult?’

I replied: ‘I am alive, and if you long for fame, it might be a precious thing to you, if I put your name among the others.’ And he to me: ‘I long for the opposite: take yourself off, and annoy me no more: since you little know how to flatter on this icy slope.’ Then I seized him by the back of the scalp, and said: ‘You need to name yourself, before there is not a hair left on your head!’ At which he said to me: ‘Even if you pluck me, I will not tell you who I am, nor demonstrate it to you, though you tear at my head, a thousand times.’

“Then I seized him by the back of the scalp, and said: ‘You need to name yourself, before there is not a hair left on your head!’” (Inferno XXXII: 97, 98)

I already had his hair coiled in my hand, and had pulled away more than one tuft of it, while he barked, and kept his eyes down, when another spirit cried: ‘What is wrong with you, Bocca, is it not enough that you chatter with your jaws, but you have to bark too? What devil is at you?’ I said: ‘Now, accursed traitor, I do not want you to speak: since I will carry true news of you, to your shame.’ He answered: ‘Go, and say what you please, but, if you get out from here, do not be silent about him, who had his tongue so ready just now. Here he regrets taking French silver. You can say, “I saw Buoso de Duera, there, where the sinners stand caught in the ice.”

If you are asked who else was there, you have Tesauro de’ Beccheria, whose throat was slit by Florence. Gianni de’ Soldanier is further on, with Ganelon, and Tribaldello, who unbarred the gate of Faenza while it slept.’

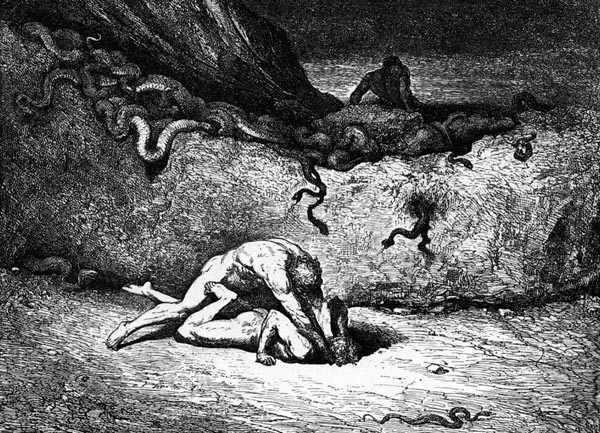

Inferno Canto XXXII:124-139 Ugolino and Ruggieri

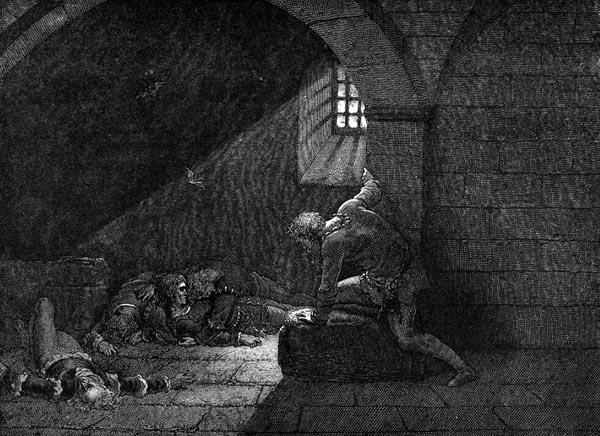

We had already left him, when I saw two spirits frozen in a hole, so close together that the one head capped the other, and the uppermost set his teeth into the other, as bread is chewed, out of hunger, there where the back of the head joins the nape. Tydeus gnawed the head of Menalippus, no differently, out of rage, than this one the skull and other parts.

“Tydeus gnawed the head of Menalippus, no differently, out of rage, than this one the skull and other parts.” (Inferno XXXII: 127—129)

I said: ‘O you, who, in such a brutal way, inflict the mark of your hatred, on him, whom you devour, tell me why: on condition that, if you complain of him with reason, I, knowing who you are, and his offence, may repay you still in the world above, if the tongue I speak with is not withered.’

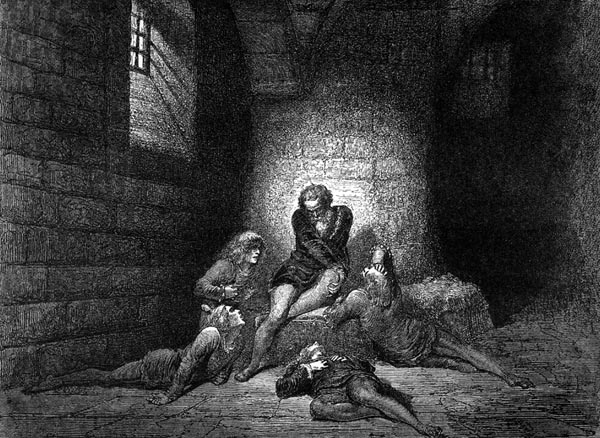

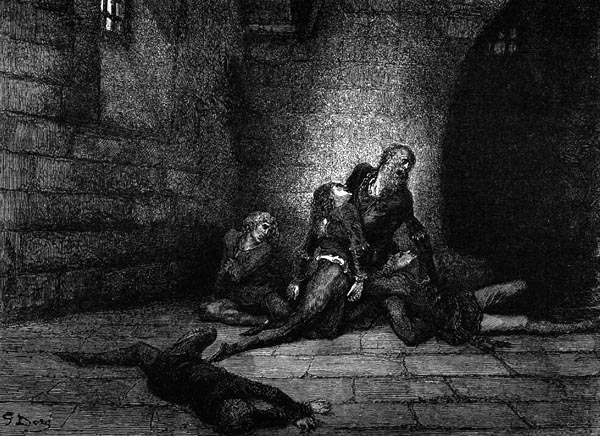

Inferno Canto XXXIII:1-90 Count Ugolino’s story

That sinner raised his mouth from the savage feast, wiping it on the hair, of the head he had stripped behind. Then he began: ‘You wish me to renew desperate grief, that wrings my heart at the very thought, before I even tell of it. But if my words are to be the seed, that bears fruit, in the infamy, of the traitor whom I gnaw, you will see me speak and weep together. I do not know who you are, nor by what means you have come down here, but when I hear you, you seem to me, in truth, a Florentine.

You must know that I am Count Ugolino, and this is the Archbishop Ruggieri. Now I will tell you why I am a neighbour such as this to him. It is not necessary to say that, confiding in him, I was taken, through the effects of his evil schemes, and afterwards killed. But what you cannot have learnt, how cruel my death was, you will hear: and know if he has injured me.

A narrow hole inside that tower, which is called Famine, from my death, and in which others must yet be imprisoned, had already shown me several moons through its opening, when I slept an evil sleep that tore the curtain of the future for me. This man seemed to me the lord, and master, chasing the wolf and its whelps, on Monte di San Guiliano, that blocks the view of Lucca from the Pisans. He had the Gualandi, Sismondi and Lanfranchi running with him, with hounds, slender, keen, and agile.

After a short chase the father and his sons seemed weary to me, and I thought I saw their flanks torn by sharp teeth. When I woke, before dawn, I heard my sons, who were with me, crying in their sleep, and asking for food. You are truly cruel if you do not sorrow already at the thought of what my heart presaged: and if you do not weep, what do you weep at?

They were awake now, and the hour nearing, at which our food used to be brought to us, and each of us was anxious from dreaming, when below I heard the door of the terrible tower locked up: at which I gazed into the faces of my sons, without saying a word. I did not weep: I grew like stone inside: they wept: and my little Anselm said to me: ‘Father you stare so, what is wrong?’ But I shed no tears, and did not answer, all that day, or the next night, till another sun rose over the world. When a little ray of light was sent into the mournful gaol, and I saw in their four faces, the aspect of my own, I bit my hands from grief. And they, thinking that I did it from hunger, suddenly stood, and said: ‘Father, it will give us less pain, if you gnaw at us: you put this miserable flesh on us, now strip it off, again.’

Then I calmed myself, in order not to make them more unhappy: that day and the next we all were silent. Ah, solid earth, why did you not open? When we had come to the fourth day, Gaddo threw himself down at my feet, saying: ‘My father, why do you not help me?’ There he died, and even as you see me, I saw the three others fall one by one, between the fifth and sixth days: at which, already blind, I took to groping over each of them, and called out to them for three days, when they were dead: then fasting, at last, had power to overcome grief.’

“Then I calmed myself, in order not to make them more unhappy.” (Inferno XXXIII: 62, 63)

“‘My father, why do you not help me?’” (Inferno XXXIII: 67, 68)

“‘…then fasting, at last, had power to overcome grief.’” (Inferno XXXIII: 73, 74)

When he had spoken this, he seized the wretched skull again with his teeth, which were as strong as a dog’s on the bone, his eyes distorted. Ah Pisa, shame among the people, of the lovely land where ‘si’ is heard, let the isles of Caprara and Gorgona shift and block the Arno at its mouth, since your neighbours are so slow to punish you, so that it may drown every living soul. Since if Count Ugolino had the infamy of having betrayed your castles, you ought not to have put his sons to the torture. Their youth made Uguccione and Brigata, and the other two my words above have named, innocents, you modern Thebes.

Inferno Canto XXXIII:91-157 Friar Alberigo and Branca d’Oria

We went further on, where the rugged frost encases another people, not bent down but reversed completely. The very weeping there prevents them weeping: and the grief that makes an impediment to their sight, turns inward to increase their agony: since the first tears form a knot, and like a crystal visor, fill the cavities below their eyebrows. And though all feeling had left my face, through the cold, as though from a callus, it seemed to me now as if I felt a breeze, at which I said: ‘Master, what causes this? Is the heat not all quenched here below?’ At which he said to me: ‘Soon you will be where your own eyes, will answer that, seeing the source that generates the air.’

And one of the sad shadows, in the icy crust, cried out to us: ‘O spirits, so cruel that the last place of all is reserved for you, remove the solid veils from my face, that I might vent the grief a little that chokes my heart, before the tears freezes again.’ At which I said to him: ‘If you would have my help, tell me who you are: and if I do not disburden you, may I have to journey to the depths of the ice.’

He replied to that: ‘I am Friar Alberigo, I am he of the fruits of the evil garden, who here receive dates made of ice, to match my figs.’ I said to him: ‘O, are you dead already?’ And he to me: ‘How my body stands in the world above, I do not know, such is the power of this Ptolomaea, that the soul often falls down here, before Atropos cuts the thread. And so that you may more willingly clear the frozen tears from your face, know that when the soul betrays, as mine did, her body is taken from her by a demon, there and then, who rules it after that, till its time is complete. She falls, plunging down to this well: and perhaps the body of this other shade, that winters here, behind me, is still visible in the world above.

You must know it, if you have only now come down here: it is Ser Branca d’Oria, and many years have passed since he was imprisoned here.’ I said to him: ‘I believe you are lying to me: Branca d’Oria is not dead, and eats and drinks, and sleeps, and puts on his clothes.’ He said: ‘Michel Zanche had not yet arrived, in the ditch of the Malebranche above, there where the tenacious pitch boils, when this man left a devil in his place in his own body, and one in the body of his kinsman who did the treachery with him. But reach your hand here: open my eyes.’ And I did not open them for him: and it was a courtesy to be rude to him.

Ah, Genoese, men divorced from all morality, and filled with every corruption, why are you not dispersed from off the earth? I found the worst spirit of Romagna was one of you, who for his actions even now bathes, as a soul, in Cocytus, and still seems alive on earth, in his own body.

Inferno Canto XXXIV:1-54 The Judecca: Satan

‘Vexilla Regis prodeunt inferni, the banners of the King of Hell advance towards us: so look in front of you to see if you discern him,’ said my Master. I seemed to see a tall structure, as a mill, that the wind turns, seems from a distance, when a dense mist breathes, or when night falls in our hemisphere, and I shrank back behind my guide, because of the wind, since there was no other shelter.

I had already come, and with fear I put it into words, where the souls were completely enclosed, and shone through like straw in glass. Some are lying down, some stand upright, one on its head, another on the soles of its feet, another bent head to foot, like a bow.

When we had gone on far enough, that my guide was able to show me Lucifer, the monster who was once so fair, he removed himself from me, and made me stop, saying: ‘Behold Dis, and behold the place where you must arm yourself with courage.’ Reader, do not ask how chilled and hoarse I became, then, since I do not write it, since all words would fail to tell it. I did not die, yet I was not alive. Think, yourself, now, if you have any grain of imagination, what I became, deprived of either state.

“‘Behold Dis, and behold the place where you must arm yourself with courage.’” (Inferno XXXIV: 20, 21)

The emperor of the sorrowful kingdom stood, waist upwards, from the ice, and I am nearer to a giant in size than the giants are to one of his arms: think how great the whole is that corresponds to such a part. If he was once as fair, as he is now ugly, and lifted up his forehead against his Maker, well may all evil flow from him. O how great a wonder it seemed to me, when I saw three faces on his head! The one in front was fiery red: the other two were joined to it, above the centre of each shoulder, and linked at the top, and the right hand one seemed whitish-yellow: the left was black to look at, like those who come from where the Nile rises. Under each face sprang two vast wings, of a size fit for such a bird: I never saw ship’s sails as wide. They had no feathers, but were like a bat’s in form and texture, and he was flapping them, so that three winds blew out away from him, by which all Cocytus was frozen. He wept from six eyes, and tears and bloody spume gushed down three chins.

Inferno Canto XXXIV:55-69 Judas: Brutus: Cassius

He chewed a sinner between his teeth, with every mouth, like a grinder, so, in that way, he kept three of them in torment. To the one in front, the biting was nothing compared to the tearing, since, at times, his back was left completely stripped of skin.

The Master said: ‘That soul up there that suffers the greatest punishment, he who has his head inside, and flails his legs outside, is Judas Iscariot. Of the other two who have their heads hanging downwards, the one who hangs from the face that is black is Brutus: see how he writhes and does not utter a word: and the other is Cassius, who seems so long in limb. But night is ascending, and now we must go, since we have seen it all.’

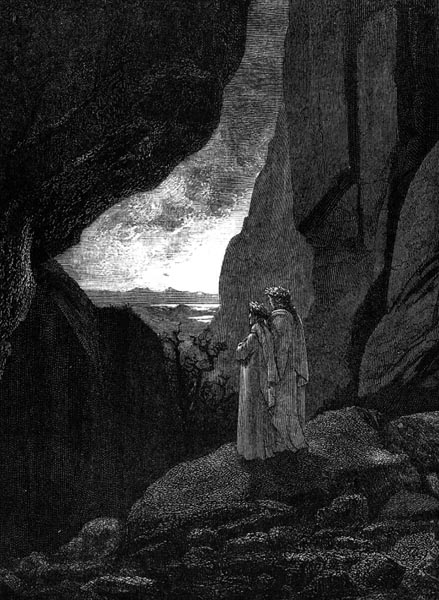

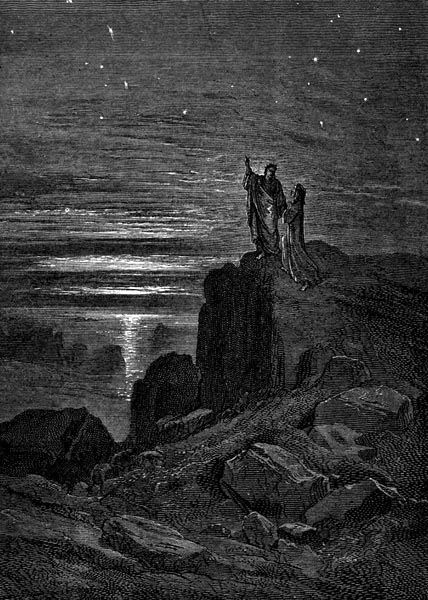

Inferno Canto XXXIV:70-139 The Poets leave Hell

I clasped his neck, as he wished, and he seized the time and place, and when the wings were wide open, grasped Satan’s shaggy sides, and then from tuft to tuft, climbed down, between the matted hair and frozen crust.

When we had come to where the thigh joint turns, just at the swelling of the haunch, my guide, with effort and difficulty, reversed his head to where his feet had been, and grabbed the hair like a climber, so that I thought we were dropping back to Hell. ‘Hold tight,’ said my guide, panting like a man exhausted, ‘since by these stairs, we must depart from all this evil.’ Then he clambered into an opening in the rock, and set me down to sit on its edge, then turned his cautious step towards me.

I raised my eyes, thinking to see Lucifer as I had left him, but saw him with his legs projecting upwards, and let those denser people, who do not see what point I had passed, judge if I was confused then, or not.

My Master said: ‘Get up, on your feet: the way is long, and difficult the road, and the sun already returns to mid-tierce.’ Where we stood was no palace hall, but a natural cell with a rough floor, and short of light. When I had risen, I said: ‘My Master, before I leave the abyss, speak to me a while, and lead me out of error. Where is the ice? And why is this monster fixed upside down? And how has the sun moved from evening to dawn in so short a time?’

And he to me: ‘You imagine you are still on the other side of the earth’s centre, where I caught hold of the Evil Worm’s hair, he who pierces the world. You were on that side of it, as long as I climbed down, but when I reversed myself, you passed the point to which weight is drawn, from everywhere: and are now below the hemisphere opposite that which covers the wide dry land, and opposite that under whose zenith the Man was crucified, who was born, and lived, without sin. You have your feet on a little sphere that forms the other side of the Judecca.

Here it is morning, when it is evening there: and he who made a ladder for us of his hair is still as he was before. He fell from Heaven on this side of the earth, and the land that projected here before, veiled itself with the ocean for fear of him, and entered our hemisphere: and that which now projects on this side, left an empty space here, and shot outwards, maybe in order to escape from him.’

Down there, is a space, as far from Beelzebub as his cave extends, not known by sight, but by the sound of a stream falling through it, along the bed of rock it has hollowed out, into a winding course, and a slow incline. The guide and I entered by that hidden path, to return to the clear world: and, not caring to rest, we climbed up, he first, and I second, until, through a round opening, I saw the beautiful things that the sky holds: and we issued out, from there, to see, again, the stars.

“The guide and I entered by that hidden path, to return to the clear world…” (Inferno XXXIV: 127—129)

“…we issued out, from there, to see, again, the stars.” (Inferno XXXIV: 133)