Homer: The Odyssey

Book V

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2004 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Bk V:1-42 Zeus sends Hermes to Calypso

- Bk V:43-91 Hermes visits Calypso

- Bk V:92-147 Hermes explains his mission

- Bk V:148-191 Calypso promises to free Odysseus

- Bk V:192-261 Odysseus builds his raft

- Bk V:262-312 Poseidon raises a storm

- Bk V:313-387 Leucothea lends Odysseus her veil

- Bk V:388-450 Odysseus tries to land

- Bk V:451-493 Odysseus reaches shore

BkV:1-42 Zeus sends Hermes to Calypso

Now Dawn rose from her bed beside renowned Tithonus, bringing light to the deathless ones and to mortal men. The gods were seated in council, Zeus the Thunderer, greatest of all, among them. Athene was speaking of Odysseus’ many sufferings, recalling them to their minds, unhappy that he was still a prisoner in Calypso’s isle:

‘Father Zeus, and all you blessed ever-living gods, may sceptered kings never be kind or gentle, or think of justice, from this time on: let them be arbitrary and cruel, since not one of the race that divine Odysseus ruled remembers him, though he was tender as a father. He suffers misery in the island home of the nymph Calypso, who keeps him captive there. He cannot head for home without oared ship or crew to carry him over the sea’s wide back: and men plot to murder his beloved son who is journeying home from sacred Pylos and noble Sparta, where he went seeking news of his father.’

Cloud-Gathering Zeus replied: ‘My child, what words escape your lips? Was this not of your own devising, that Odysseus might return and take vengeance on them all? As for Telemachus, direct him wisely, since you have the power, so that he may reach home safely, while the Suitors return, their purpose thwarted.’

Then he instructed Hermes, his faithful son: ‘Since you are ever our messenger, Hermes, tell the nymph of the lovely tresses of our resolve, that enduring Odysseus shall return without help of gods or mortal men, but with great suffering he shall come, on a close-knit raft, on the twentieth day, to Scheria’s rich soil, the land of the Phaeacians, kin to the gods. They will honour him from the heart, as if he were divine, and send him on board ship to his native land, gifting him piles of gold, and bronze and garments, more than he could ever have won from Troy if he had reached home safely with his fair share of the spoils. This is the way he is fated to see his people again, his vaulted palace, and native isle.’

BkV:43-91 Hermes visits Calypso

He spoke, and the messenger god, the slayer of Argus, promptly obeyed. He quickly fastened to his feet the lovely imperishable golden sandals that carry him swift as the flowing wind over the ocean waves and the boundless earth. He took up the wand as well, with which he lulls men to sleep, or wakes them from slumber, and the mighty slayer of Argus flew off with it in his hand. He stepped out of the ether onto the Pierian coast then swooped over the sea, skimming the waves like a cormorant that drenches its dense plumage with brine, as it searches for fish in the fearsome gulfs of the restless ocean. So Hermes travelled over the endless breakers, until he reached the distant isle, then leaving the violet sea he crossed the land, and came to the vast cave where the nymph of the lovely tresses lived, and found her at home.

A great fire blazed on the hearth, and the scent of burning cedar logs and juniper spread far across the isle. Sweet-voiced Calypso was singing within, moving to and fro at her loom, weaving with a golden shuttle. Around the cave grew a thick copse of alder, poplar and fragrant cypress, where large birds nested, owls, and falcons, and long-necked cormorants whose business is with the sea. And heavy with clustered grapes a mature cultivated vine went trailing across the hollow entrance. And four neighbouring springs, channelled this way and that, flowed with crystal water, and all around in soft meadows iris and wild celery flourished. Even an immortal passing by might pause and marvel, delighted in spirit, and the messenger-god, the slayer of Argus, stood there and wondered. But when he had marvelled at all he saw, he quickly entered the wide-cave-mouth, and Calypso, the lovely goddess knew him when she saw his face, since the deathless gods are not unknown to each other, however far apart they live. Of Odysseus there was no sign, since he sat wretched as ever on the shore, troubling his heart with tears and sighs and grief. There he could gaze out over the rolling waves, with streaming eyes.

When the lovely goddess, Calypso, had seated Hermes on a bright gleaming chair, she questioned him: ‘Why are you here, Hermes of the golden wand, an honoured and welcome guest? You rarely visit me. Speak whatever is in your mind: my heart says do it, if do it I can, and if it can be done. But follow me now, so I can offer you refreshment.’

BkV:92-147 Hermes explains his mission

With this the goddess set ambrosia on a table in front of him, and mixed a bowl of red nectar. So the messenger-god, the slayer of Argus, ate and drank, and when he had dined to his heart’s content, he replied to her question: ‘Goddess to god, you ask why I am here, and since you ask I will tell you clearly. Zeus it was who sent me, unwillingly. Who would choose to fly over the vast space of the briny sea, unspeakably vast? And no cities about: no mortals to sacrifice to the gods, and make choice offerings. But no god can escape or deny the will of Zeus, the aegis bearer. He says that you have here a man, the most unfortunate of all those warriors who fought nine years round Priam’s city, and sacked it in the tenth, then left for home. Setting out, having offended Athene, she raised a violent storm and towering seas. All the rest of his noble friends were drowned, but the wind and the waves that carried him brought him here. Zeus commands you to send him swiftly on his way: it is not his fate to die here far from his friends: he is destined to see those friends again, and reach his vaulted house and his native isle.’

At this, the lovely goddess, Calypso, shuddered, and spoke to him winged words: ‘You are cruel, you gods, and quickest to envy, since you are jealous if any goddess openly mates with a man, taking a mortal to her bed. Jealous, you gods, who live untroubled, of rosy-fingered Dawn and her Orion, till virgin Artemis, of the golden throne, attacked him with painless arrows in Ortygia, and slew him. Jealous, when Demeter of the lovely tresses, gave way to passion and lay with Iasion in the thrice-ploughed field. Zeus soon heard of it, and struck him dead with his bright bolt of lightning. And jealous now of me, you gods, because I befriend a man, one I saved as he straddled the keel alone, when Zeus had blasted and shattered his swift ship with a bright lightning bolt, out on the wine-dark sea. There all his noble friends were lost, but the wind and waves carried him here. I welcomed him generously and fed him, and promised to make him immortal and un-aging. But since no god can escape or deny the will of Zeus the aegis bearer, let him go, if Zeus so orders and commands it, let him sail the restless sea. But I will not convey him, having no oared ship, and no crew, to send him off over the wide sea’s back. Yet I’ll cheerfully advise him, and openly, so he may get back safe to his native land.’

‘Then send him off now, as you suggest’, said the messenger god, the slayer of Argus, ‘and be wary of Zeus’ anger, lest he is provoked and visits that anger on you some day.’

BkV:148-191 Calypso promises to free Odysseus

With this the mighty slayer of Argus departed, and the lovely Nymph, mindful of Zeus’ command, looked for valiant Odysseus. She found him sitting on the shore, his eyes as ever wet with tears, life’s sweetness ebbing from him in longing for his home, since the Nymph no longer pleased him. He was forced to sleep with her in the hollow cave at night, as she wished though he did not, but by day he sat among rocks or sand, tormenting himself with tears, groans and anguish, gazing with wet eyes at the restless sea.

The lovely goddess spoke as she approached him: ‘Be sad no longer, unhappy man, don’t waste your life in pining: I am ready and willing to send you on your way. Fell tall trees with the axe, make a substantial raft, and fasten planks across for decking, so it can carry you over the misty sea. And I will stock it with bread and water, and red wine to your heart’s content, to stave off hunger and thirst, and I’ll give you clothing too. And I’ll raise a following wind, so you reach home safely, if that is the will of the gods who rule the wide heavens, since they have more power than I to fulfil their purpose.’

At this noble enduring Odysseus shuddered, and he spoke to her winged words: ‘Goddess, you must mean something other, suggesting I cross the dangerous, daunting sea’s vast gulf on a raft, where not even the fine swift sailing ships go, enjoying the winds of Zeus. I will not trust myself to a raft when you do not wish it, unless you, goddess, give me your solemn word that you are not planning something new to harm me.’

Calypso, the lovely goddess, smiled at his words and, stroking his arm, replied: ‘What a rascal you are, with a devious mind, to think of speaking so to me? So let Earth be my witness now, and the underground waters of Styx, this the blessed gods’ greatest most dreadful oath, that I will not plan anything new to harm you. Rather my thoughts and advice are like those I would have for myself if I needed them. My intentions are honest ones, and my heart is not made of iron. It too can feel pity.’

BkV:192-261 Odysseus builds his raft

With this, the lovely goddess swiftly walked away, and he followed in her footsteps. Man and goddess reached the hollow cave, and he sat down on the chair that Hermes had used. Then the Nymph set all kinds of food and drink before him, those that mortals consume. But before her the maids set ambrosia and nectar, as she sat facing divine Odysseus. So they reached for the good things prepared for them. And when they had finished eating and drinking, Calypso, that lovely goddess, spoke first: ‘Son of Laertes, scion of Zeus, Odysseus of many resources, must you leave, like this, so soon? Still, let fortune go with you. Though if your heart knew the depths of anguish you are fated to suffer before you reach home, you would stay and make your home with me, and be immortal, no matter how much you long to see that wife you yearn for day after day. I am surely no less than her, I contend, in height or form, since no woman can reasonably compete with the gods in form or face.’

Then resourceful Odysseus replied to her: ‘Great goddess, do not be angry at what I say. I know myself that wise Penelope is less than you, it’s true, in looks and stature, being a mortal, while you are immortal and ever young. Even so I yearn day after day, longing to reach home, and see the hour of my return. And if some god should strike me, out on the wine-dark sea, I will endure it, owning a heart within inured to suffering. For I have suffered much, and laboured much, in war and on the seas: add this then to the sum.’

As he spoke the sun dipped, and darkness fell. And the two of them found the deepest recess of the hollow cave, and delighted together in their lovemaking.

As soon as rosy-fingered Dawn appeared, Odysseus dressed in tunic and cloak, and the Nymph clothed herself in a long white robe, lovely and closely woven, and fastened a fine gold belt around her waist, and covered her head with a veil. Then she began to prepare valiant Odysseus’ departure. She gave him a bronze double axe that fitted his hands well, one with its blades both sharpened, its fine olivewood handle firmly fixed, and a polished adze as well. She led the way to the fringes of the island where stands of alder, poplar, and fir rose to the sky: dry, well-seasoned timber that would ride high in the water. When she had shown him where the tall trees stood, Calypso, the lovely goddess, turned for home, while he began felling timber, making rapid progress. He cut down twenty trees in total, trimming them with the axe: then he smoothed them dextrously, and made their edges true. Meanwhile Calypso, the lovely goddess, brought him drills, and he bored through the timbers then joined them, hammering the mortice and tenon joints together. Odysseus made his raft as wide as a skilled shipwright makes the hull of a broad-beamed trading vessel. And he placed the decking, bolting the planks to the close-set timbers as he worked, completing the raft with long gunwales. He fixed up a mast and yardarm, and a steering oar for a rudder. Then he lined its sides from stem to stern with intertwined willows, as a defence against the sea, and covered the deck with brushwood. Meanwhile Calypso, the lovely goddess, had brought him the cloth for a sail, and he skilfully fashioned that too. Then he lashed the braces, halyards and sheets in place, and levered it down to the shining sea.

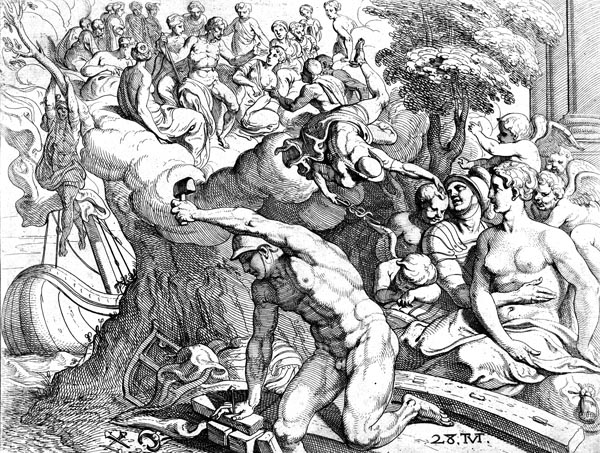

‘Odysseus and Calypso’

BkV:262-312 Poseidon raises a storm

By the fourth day all his work was done, and on the fifth lovely Calypso bathed him and dressed him in scented clothes, and watched him set out. The goddess had placed a skin filled with dark wine on board, and a larger one of water, and a bag of provisions, full of many good things to content his heart, and she sent a fine breeze, warm and gentle. Odysseus spread his sail to the wind with joy, and steered the raft cleverly with the oar as he sat there. At night he never closed his eyes in sleep, but watched the Pleiades, late-setting Bootes, and the Great Bear that men call the Wain, that circles in place opposite Orion, and never bathes in the sea. Calypso, the lovely goddess had told him to keep that constellation to larboard as he crossed the waters. Seventeen days he sailed the seas, and on the eighteenth the shadowy peaks of the Phaeacian country loomed up ahead, like a shield on the misty sea.

But now Lord Poseidon, the Earth-Shaker, returning from visiting Ethiopia, saw him far off from the Solymi range, as he came in sight over the water: and the god, angered in spirit, shook his head, and said to himself: ‘Well now, while I was among the Ethiopians, the gods have certainly changed their minds about Odysseus! Here he is, close to Phaeacian country, where he’s fated to escape his trials and tribulations. But I’ll give him his fill of trouble yet.’

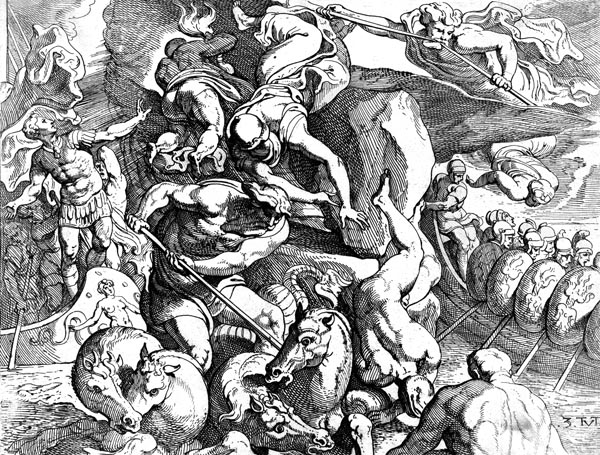

‘Poseidon raises the storm’

With that, he gathered the cloud, and seizing his trident in his hands, stirred up the sea, and roused the tempest blast of every wind, and hid the land and sea with vapour: and darkness swooped from the sky. The East Wind and South Wind clashed together, and the stormy West Wind, and the heaven-born North Wind, driving a vast wave before him. Then Odysseus’ knee-joints slackened and his heart melted, and deeply shaken he communed with his own valiant spirit: ‘Oh, wretch that I am, what will become of me? I fear the goddess spoke true when she said I would know full measure of suffering at sea before I reached my own country: now all is coming to pass. Zeus has covered the wide heavens with cloud, and troubled the sea, and the tempest blast of every wind sweeps over me: now I am doomed for sure. Thrice blessed, four times blessed those Danaans who died long ago on Troy’s wide plain working the will of the sons of Atreus. I wish I had met my fate like them, and died on that day when the Trojan host hurled their bronze-tipped spears at me while we fought for the corpse of Achilles, son of Peleus. Then I would have had proper burial, and the Achaeans would have trumpeted my fame, but now I am destined to die a miserable death.’

BkV:313-387 Leucothea lends Odysseus her veil

Even as he thought this, a great wave, sweeping down with terrible power, crashed over him, and whirled his raft around. Loosing the steering oar, he was thrown far from the raft, while a savage blast of tempestuous wind snapped the mast in two, and yardarm and sail fell far off in the sea. Long the wave held him under, for the clothes Calypso gave him weighed him down, and he could not surface from under the great wave’s flow. At last he rose, and spat out bitter brine that ran too in streams from his hair. Labouring as he was, he still remembered the raft, lunged after it through the breakers, holding tight clambered to its centre, and sat there, trying to escape a deadly fate: and the heavy seas carried the raft to and fro in their path. Just as in autumn the North Wind blows a ball of thistle tufts, clinging together, over the fields, so the winds drove the raft to and fro over the sea. Now the South Wind flung it to the North Wind to be played with, then the East Wind gave it to the West Wind in play.

But Leucothea, the White Goddess, saw him, she who once had mortal speech as Ino of the slender ankles, Cadmus’ daughter, but now in the deep is honoured by the gods. She pitied Odysseus, driven on, surrounded by dangers, and she rose from the waves like a sea mew on the wing, settled on the close-knit raft, and spoke to him:

‘Poor wretch, why has Poseidon, the Earth-Shaker, dealt you such fierce suffering, sowing the seed of endless misery for you? Yet for all his anger he shall not destroy you quite. You seem a man of sense, so do as I tell you. Strip off these clothes, and let the wind take your raft, while you swim hard towards the Phaeacian coast, where you are destined to escape the waves. And take this veil, and wind it round your waist. It has divine power, and you need not fear injury or death. But when you clasp the land, unwind it once more, and cast it far out onto the wine-dark sea, and turn your eyes away.’

With this, the goddess gave him the veil, and like a sea mew dived at the stormy sea, and the dark wave covered her. Then long-suffering noble Odysseus thought long and hard, and, deeply shaken, communed with his valiant spirit: ‘Oh, let this not be one of the deathless ones, weaving a net for me, telling me to abandon the raft. I will not obey her yet, since the land, she said I would escape to, was far away when I saw it. This I shall do, and this seems best, to wait here as long as the timbers hold, and endure in misery, then if the seas beat the raft to pieces, swim, for want of a better plan.’

While he reflected in mind and heart, Poseidon, Earth-Shaker, raised another fearsome, threatening wave, arched above Odysseus, then hurled it down on him. Like a strong wind catching a pile of dry straw, scattering the stalks here and there, so the breaker scattered the raft’s timbers. But Odysseus straddled a plank, like a horseman, and stripped off the clothes lovely Calypso had given him. Then he wound the veil round his waist, and arms outstretched plunged into the sea, prepared to swim. Lord Poseidon saw him, and shook his head, saying to himself: ‘Well then, after all that, you can drift through the sea till you come to men favoured by Zeus. Still I don’t think you’ll find it easy.’ And with that he lashed his horses, with beautiful manes, and headed for his glorious palace at Aegae.

But Athene, daughter of Zeus, had an idea. She checked the winds in their course, and ordered them all to stop, and sink to rest, except for the swift North Wind, and him she commanded to smooth the waves ahead of the swimmer, so that Odysseus, scion of Zeus, might escape from fate and death, and reach the Phaeacians, who love the oar.

BkV:388-450 Odysseus tries to land

Two nights and days he was tossed about on the swollen sea, and many a time he thought himself doomed. But when Dawn of the lovely tresses gave birth to the third day, the wind dropped, and there was breathless calm. Glancing ahead as a long breaker suddenly lifted him, he glimpsed the shore nearby. Just as a father’s recovery is welcome to his children when, to their joy, the gods free him from sickness, from the grip of some evil force that caused great pain, and long wasted him, so the wooded shore was welcome to Odysseus. He swam on, eager to reach solid ground. But, within shouting distance of the land, he heard the thunder of surf on rock, as powerful waves battered the coast, veiling the sea with spray. There was no safe harbour, no roadstead for ships to ride in, only jutting reefs and rocky cliffs and headlands. Then Odysseus’ knee-joints slackened and his heart melted, and deeply shaken he communed with his valiant spirit:

‘Oh, now Zeus has allowed me to reach land, beyond all expectation, and I have managed to carve my way across the deep, there seems no way to escape the grey waters. Offshore are pointed reefs that the waves roar over, foaming: the rock is sheer, and the water deep close in, so a man can’t find his footing and escape from danger. If I try to get ashore a breaker may catch me, and dash me against the jagged rocks, and my labours will be in vain. If I swim on in hope of finding a shelving beach and a natural harbour, I fear a squall may strike again and carry me groaning out to sea, into the teeming deep, or some god may raise a monster from the void, like those herds great Amphitrite breeds. I know the Earth-Shaker means me harm.’

As he considered all this in heart and mind, a large wave drove him towards the splintered shore. There his skin would have been stripped, and his bones shattered, if the goddess, bright-eyed Athene, had not given him an idea. Rushing by he clung to a rock with both hands, and hung there, groaning, till the wave had passed. So he survived, but with its backflow the wave caught him again, and took him, and drove him far out to sea. Just as pebbles stick to an octopus’ suckers when it is dragged from its crevice, so pieces of skin stripped from his sturdy hands stuck to the rock, and the wave swallowed him. Then wretched Odysseus would surely have come to a premature end, if bright-eyed Athene had not sharpened his wits. Freeing himself from the surge breaking on shore, he swam outside it, staring towards the land, hoping to find a shelving beach or a natural harbour. Then, swimming, he came to the mouth of a swift-running river that seemed a good place, free of stones, and sheltered from the wind. He felt the current flowing, and prayed to the river god:

‘Hear me, Lord, whoever you might be. I come to you, as to one who is greatly longed for, as I try to escape the sea and Poseidon’s menace. Even to the eyes of the deathless gods that man is sacred who comes as a wanderer, as I come to your stream, to your knees, after many trials. Pity me, Lord, I am your suppliant.’

BkV:451-493 Odysseus reaches shore

As he ended, the god stemmed the current, held back the waves, and smoothed the water ahead, so bringing him safely to the river mouth. His knees gave way, and his arms fell slack, his strength exhausted by the sea. All his flesh was swollen, and streams of brine oozed from his mouth and nostrils. So he lay there, breathless, speechless, with barely energy enough to stir. But as he revived his spirits rose, and he unwound the goddess’s veil and dropped it into the ocean-bound flow: the current sweeping it downstream, so it was soon in Ino’s hands. Odysseus turned from the river, sank into the reeds and kissed the earth, giver of crops: and deeply shaken he communed with his valiant spirit:

‘Oh, what will become of me? What is my fate? If I lie awake in the riverbed here, through the weary night, I fear the bitter cold and the dewfall may conquer my labouring heart, weak as it is, and river breezes blow chill at dawn. But if I climb the slope to the shadowy wood, and lie down in a dense thicket, hoping to lessen the cold and fatigue, and fall softly asleep, I fear to become the prey of wild beasts.’

Still as he thought about it, the latter seemed best: he headed for the wood, and found a place near the water by a clearing: there he crept under a pair of bushes, a thorn and an olive, growing from the same spot. They grew so closely twined together that the force of the damp breeze, and the bright sunlight, and the driving rain failed to penetrate. Under these Odysseus crept. He quickly made a wide bed with his hands from the heaps of fallen leaves, enough there to cover two or three men from the bitterest winter weather. Gazing at it, long-suffering Odysseus was relieved, and lay down in the centre, and covered himself with the fallen leaves. As a farmer on a lonely farm buries a glowing log under the blackened embers, to preserve a spark of fire, so that he need not light it again from somewhere else, so Odysseus buried himself in the leaves. And Athene poured sleep into his eyes, so as to close his eyelids, and free him quickly from utter weariness.