Homer: The Odyssey

Book XVII

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2004 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Bk XVII:1-60 Telemachus goes to the palace

- Bk XVII:61-106 Telemachus finds Theoclymenus

- Bk XVII:107-165 Theoclymenus prophesies Odysseus’ presence

- Bk XVII:166-203 Odysseus sets out for the city

- Bk XVII:204-253 Melanthius taunts Odysseus

- Bk XVII:254-289 Odysseus reaches the palace

- Bk XVII:290-327 The death of Odysseus’ dog, Argus

- Bk XVII:328-395 Odysseus among the Suitors

- Bk XVII:396-461 Antinous is angered

- Bk XVII:462-504 Odysseus is struck on the shoulder

- Bk XVII:505-550 Penelope summons the stranger

- Bk XVII:551-606 Odysseus declines to see Penelope

BkXVII:1-60 Telemachus goes to the palace

As soon as rosy-fingered Dawn appeared, godlike Odysseus’ steadfast son Telemachus, eager to leave for the city, strapped on his fine sandals, picked up his sturdy spear, one comfortable to hold, and said to the swineherd: ‘Old friend, I’m off to town to find my mother: she won’t stop her sad weeping, her tearful grieving, till she sees me in the flesh. Here are my orders for you. Guide this unfortunate stranger to the city, so he can beg for food there: someone may decide to give him a crust and a cup of water. With all my troubles I can’t bear everyone’s burden myself. So much the worse for him if that should make him genuinely angry. I would rather speak the truth.’

Then resourceful Odysseus spoke up, saying: ‘Friend, I no more wish to be left here myself. It’s better for a beggar to beg in town than in the country: someone may decide to give me food. I’m too old to live on a farm at some master’s beck and call. Go ahead, and this man will take me there as you command, when I’ve warmed myself at the fire and the sun has some heat, since the rags I wear are wretchedly thin, and I fear the morning frost might prove too much for me, given that you tell me it’s a long walk to town.’

At this, Telemachus strode off quickly through the farm, planning disaster for the Suitors. When he reached the royal palace, he leant his spear against a tall pillar, and crossed the stone threshold.

The nurse, Eurycleia, who was spreading fleecy covers on the fine-wrought chairs, was first to see him. She rushed towards him, in floods of tears, while noble Odysseus’ other maids gathered round him, welcoming him lovingly with kisses on head and shoulders.

Soon wise Penelope, the image of Artemis or golden Aphrodite, came from her room, and weeping threw her arms round her dear son, kissing his face and his fine eyes, and sobbed out winged words: ‘Telemachus, light of my eyes, here you are. I thought I would never see you again when you left in your ship for Pylos to seek news of your brave father, secretly and against my wishes. Come tell me what news you have of him.’

Wise Telemachus replied: ‘Mother, don’t rouse my tears, don’t stir my emotions: I’ve barely escaped from total ruin. Bathe, and dress yourself in clean linen, then go to your room upstairs with your women, and promise the gods a perfect offering, hoping that Zeus might bring about a day of judgement. I will go to the gathering place and invite a guest to our house, a stranger who returned from Pylos with me. I sent him on ahead with my noble friends, and told Peiraeus to take him home and welcome him, and show him kindness and honour till I came.’

To these words of his she made no reply, but went and bathed, and dressed in clean linen, and promised the gods a perfect offering, hoping that Zeus might bring about a day of judgement.

BkXVII:61-106 Telemachus finds Theoclymenus

Then Telemachus, spear in hand, with two swift hounds at his heels, left by way of the hall. And Athene granted him such miraculous grace that every face turned to him in wonder as he passed. The noble Suitors crowded round him speaking words of respect while plotting evil in the depths of their hearts. But he evaded the dense throng, and took his place alongside Mentor, Antiphus and Halitherses, his father’s friends of old. As they questioned him, Peiraeus, famous with the spear, approached leading the stranger, Theoclymenus, through the city to the gathering place. Telemachus did not pause for long before he rose and went to meet them. Piraeus it was who was first to speak: ‘Telemachus, send your women to my house, without delay, to collect Menelaus’ gifts to you.’

Wise Telemachus replied: ‘Peiraeus who knows what may happen. If the arrogant Suitors murder me behind the closed doors of the house, and split my fathers’ wealth between them, I would rather you kept the things yourself to enjoy. If instead it is I who sow the seeds of death for them, bring it all to the palace, and I will share your pleasure.’

With this, he guided his long-suffering guest to the house. When they reached the noble halls, they hung their cloaks on bench and chair, and entered the gleaming baths to bathe. When the women had washed them, rubbed them with oil, and dressed them in tunics and fleecy cloaks, they left the baths and were seated. A maid brought water in a fine golden jug so they could rinse their hands, pouring it over their hands into a silver basin. Then she brought a gleaming table, and the loyal housekeeper set bread and dishes of meat before them, giving freely of her stores. Telemachus’ mother sat opposite by a pillar, leaning from her chair to spin her delicate yarn, while they reached for the good food before them. When they had quenched their hunger and thirst, wise Penelope was first to speak: ‘Telemachus, I will go to my room, there to lie down on my bed, that has become a bed of tears indeed, ever since the day when Odysseus left for Troy with the Atreides. It seems you do not care to tell me the truth, though the Suitors are absent, as to whether you’ve heard anything of your father’s return.’

BkXVII:107-165 Theoclymenus prophesies Odysseus’ presence

‘Mother,’ wise Telemachus answered, ‘be assured I’ll tell you all. We went to Pylos, to Nestor, the shepherd of his people, who gave me a kind welcome, receiving me in his great palace as a father might welcome his own son back from a distant journey. He and his glorious sons were as kind to me as could be. But he’d heard not a word from anyone of brave Odysseus, whether living or dead. So he sent me on in a well-made horse-drawn chariot, to Sparta, to Menelaus, the famous warrior, the son of Atreus. There I met Argive Helen, for whose sake they and the Trojans laboured by the gods’ will. Menelaus of the loud war-cry asked me straight out what I sought in lovely Lacedaemon, and I told him the truth.

Then he cried out in answer: “Rogues, men without courage, they are, who wish to creep into a brave man’s bed. Odysseus will bring them to a cruel end, just as if a doe had left twin newborn fawns asleep in some great lion’s lair in the bush, and gone for food on the mountain slopes and in the grassy valleys, and the lion returned to its den and brought them to a cruel end. By Father Zeus, Athene, and Apollo, I wish he would come among those Suitors with that strength he showed in well-ordered Lesbos, when he rose to wrestle with Philomeleides, and threw him mightily, to all the Achaeans’ delight. Then they would meet death swiftly, and a dark wedding. But concerning what you ask of me, I will not evade you, or mislead you: on the contrary, I will not hide a single fact of all that the infallible Old Man of the Sea told me. He said he saw him shedding great tears in the island haunt of the Nymph Calypso, who keeps him captive there, far from his native land, since he has no oared ship, no crew, to carry him over the wide waters.”

Those were the words of Menelaus, famous warrior, son of Atreus. Afterwards I set out for home, and the immortals sent a helpful breeze, and carried me swiftly home.’ So spoke Telemachus, and troubled her heart.

Then godlike Theoclymenus spoke out too, saying: ‘Honoured wife of Laertes’ son Odysseus, Menelaus has no true knowledge: but listen to me, and I will prophesy with truth and openness. Let Zeus above all be my witness, and this welcoming table and hearth of peerless Odysseus that I have reached: in truth Odysseus has reached this island even now, and waiting or reconnoitring he gains knowledge of their crimes, and sows the seeds of trouble for all those Suitors. I noted a bird of omen clearly as I sat on the oared ship, and told Telemachus so.’

‘Ah, stranger,’ wise Penelope replied, ‘if only your words should prove true. Then you will swiftly know such kindness and gifts from me that all who meet you will call you blessed.’

BkXVII:166-203 Odysseus sets out for the city

While they were speaking, the arrogant Suitors were enjoying themselves as usual, hurling the javelin and discus over the flat ground in front of the palace. At the dinner hour, when the drovers brought home their flocks from the fields, Medon, most popular of the heralds, who was always there at the feasts, said: ‘Now you youngsters have delighted your hearts at your sports, come to the hall so we can prepare the meal: there’s a right time for dining too.’

At this, obeying his words, they stood, and went towards the royal palace, where they threw their cloaks over seats and benches, and prepared the feast by slaughtering well-fed sheep and goats, fatted pigs, and a heifer from the herd.

Meanwhile Odysseus and the worthy swineherd were making ready to travel to the city. The master swineherd was first to speak: ‘Stranger, since you are keen to go to the city as my master said – as for me I’d rather have left you here to watch the farm, but I respect him and fear he would scold me later, and a master’s rebuke is chastening – well, come, let’s be off. The day is nearly done, and you’ll find the evening cold.’

Resourceful Odysseus replied: ‘I listen and hear, and you speak to a man who understands you. Let’s go, and you can show me the whole path. But give me a stick to lean on, if you have one trimmed, since you say the track is truly treacherous.’

So saying, he slung his wretched torn leather pouch over his shoulder by its twisted strap, and Eumaeus gave him a staff that suited him, and off they went, leaving the herdsmen and the dogs to guard the farm. So the swineherd led his master to the city, him leaning on a stick, like a beggar, old and wretched, his body draped in miserable rags.

BkXVII:204-253 Melanthius taunts Odysseus

Along the rocky path, near to the city, they came to a clear, stone-lined spring where the townspeople drew their water. Ithacus, Neritus and Polyctor had dug it, and a grove of water-loving poplars ringed it round. The cold water fell from the cliff above, and over the spring they had built an altar to the Nymphs, where passers-by left offerings. There they met Melanthius, Dolius’ son, with his two herdsmen, driving the pick of his she-goats to the Suitors’ feast. When he set eyes on them he abused them, with a flood of coarse and hostile words, and stirred Odysseus’ anger.

‘Here comes vice leading vice, indeed! The god matches like with like, as always. You miserable swineherd you, tell me I pray where you’re taking this vile pig, a beggarly nuisance that ruins feasts? He’s no man to whom swords and cauldrons are due. He’s one who’ll scratch his back on every pillar, begging for scraps. If you give him to me to tend the farm, muck out the pens, and hump fodder for the goats, he’d maybe fatten his thighs drinking whey. But since he only knows mischief, he’ll not deign to look for work. He’ll skulk around, and beg, to feed that bottomless gut of his. But I tell you how it will be, for certain, if he reaches noble Odysseus’ palace, his ribs will shatter many a footstool hurled at his head by the hands of real men who’ll pelt him through the halls.’

With this, the fool barged Odysseus as he passed, but failed to knock him from the path. Odysseus stood there, unmoved, debating whether to leap at him and beat him to death with his stick, or take him by the ears and thump his head on the ground. He endured it however, restraining himself, while the swineherd looked Melanthius straight in the eyes, and rebuked him. Lifting his hands in prayer Eumaeus cried: ‘Daughters of Zeus, Nymphs of the Fountain, if ever Odysseus burned lambs’ and kids’ thigh-pieces folded in fat on your altars, grant me this wish, that my master might return, with a god to guide to him. Then he’d cure you, Melanthius, of your insolent ways, roaming arrogantly through the city, while useless herdsmen spoil your flock.’

The goatherd, Melanthius, answered him back. ‘How the cur whines, bent on mischief! Some day I’ll take him far from Ithaca, on a black oared ship, and sell him for a price. If only Apollo of the Silver Bow would strike Telemachus down in the hall today, or the Suitors kill him, as certainly as Odysseus’ chance of return has been ended in some far land.’

BkXVII:254-289 Odysseus reaches the palace

With that he strode past them, as they walked slowly on, and quickly came to the royal palace. There he went straight in and seated himself among the Suitors opposite Eurymachus, who of them all liked him most. The servants placed meat for him, and the faithful housekeeper brought him bread to eat.

When Odysseus and the worthy swineherd arrived, they halted, with the sound of the lyre ringing in their ears, since Phemius was striking the chords of a song for the Suitors. Odysseus took the swineherd by the arm, saying: ‘Surely this is Odysseus’ house, Eumaeus. It would be easy to recognise among a thousand. There’s building after building. The courtyard wall’s complete with coping, and the gates are well-protected. No one could disregard it. And I see the house is full of men feasting: you can smell the meat roasting, and hear the sounds of the lyre that the gods created to accompany a feast.’

Eumaeus, the swineherd, you replied, saying: ‘You are quick-witted as always and easily found it out. But now let’s think what to do. You could go first, enter the palace, and join the Suitors, while I stay here, or you could stay here if you prefer, and I’ll go on before you. But don’t wait about, if you do, since someone may see you, and hurl something at you, or chastise you. Please decide.’

Then noble long-suffering Odysseus answered: ‘I listen and hear: you speak to a man who understands you. Do you go first, and I will remain behind: I’m used to missiles and blows. My heart knows how to suffer, after the pain I’ve endured in war and at sea: just add this to all that’s gone before. But one thing no man can hide is ravening hunger, a cursed plague that brings men plenty of trouble. Oared ships are even launched because of it, bringing evil to enemies on the waves.’

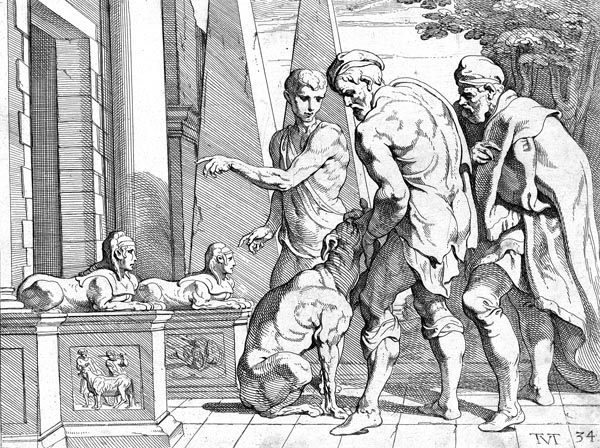

BkXVII:290-327 The death of Odysseus’ dog, Argus

So they spoke. And a dog, lying there, lifted its head and pricked up its ears. Argus was the hound of noble Odysseus, who had bred him himself, though he sailed to sacred Ilium before he could enjoy his company. Once the young men used to take the dog out after wild goat, deer and hare, but with his master gone he lay neglected by the gate, among the heaps of mule and cattle dung that Odysseus’ men would later use to manure the fields. There, plagued by ticks, lay Argus the hound. But suddenly aware of Odysseus’ presence, he wagged his tail and flattened his ears, though no longer strong enough to crawl to his master. Odysseus turned his face aside and hiding it from Eumaeus wiped away a tear then quickly said: ‘Eumaeus, it’s strange indeed to see this dog lying in the dung. He’s finely built, but I can’t tell if he had speed to match or was only a dog fed from the table, kept by his master for show.’

‘Odysseus is recognised by his dog Argus’

Then, Eumaeus, the swineherd, you replied: ‘Yes this dog belongs to a man who has died far away. If he had the form and vigour he had when Odysseus left for Troy you’d be amazed by the speed and power. He was keen-scented on the trail, and no creature he started in the depths of the densest wood escaped him. But now he is in a sad state, and his master has died far from his own country, and the thoughtless women neglect him. When their masters aren’t there to command them, servants don’t care about the quality of their work. Far-voiced Zeus takes half the good out of them, the day they become slaves.’

With this he entered the stately house and walking straight into the hall joined the crowd of noble suitors. As for Argus, seeing Odysseus again in this twentieth year, the hand of dark death seized him.

BkXVII:328-395 Odysseus among the Suitors

Now, godlike Telemachus was the first to notice the swineherd as he entered the hall, and with a nod he called him swiftly to his side. Eumaeus looked round then picked up a stool nearby, where the carver sat when slicing the joints of meat for the Suitors at the feast. He took the stool and set it down at Telemachus’ table, opposite him, then seated himself there. A steward brought him a portion of meat, and helped him to bread from a basket.

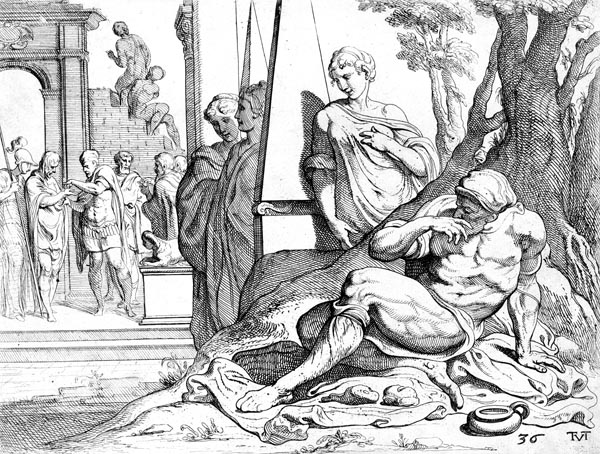

Odysseus entered close on Eumaeus’ heels, in his beggar’s disguise, looking old and wretched, leaning on his staff, and clothed in miserable rags. He sat down on the ash wood sill of the doorway, leaning on the doorpost made of cypress that had been carefully planed and trued to the line by some carpenter of old.

‘Odysseus, dressed as a beggar, sits in front of his palace in Ithaca’

Telemachus called the swineherd, and taking a whole loaf from the fine bread basket, then adding as much meat as his hands could hold, he spoke to him, saying: ‘Take this food to the stranger, and tell him to do the round of the Suitors one by one, as well. It doesn’t do for a man in need to be shy.’

At this, the swineherd went over to Odysseus, and as he approached him spoke with winged words: ‘Stranger, this is from Telemachus, who suggests you do the round of the Suitors one by one, and says that a man in need should not be shy.’

‘Odysseus, accepts meat from Telemachus’

Resourceful Odysseus spoke in return: ‘Lord Zeus, I pray, grant that Telemachus may be blessed among men, and receive all that his heart desires.’ Then he took the food with both hands and set it down in front of him on his shabby leather bag. While the minstrel sang in the hall he ate, and ended his meal as the bard was finishing the song, whereupon the Suitors filled the hall with their noise. Now Athene appeared at Odysseus’ side, close to that son of Laertes, and prompted him to go and gather scraps among the Suitors, and find out which were decent men and which were wild, not that she meant to save a single one from death. So round he went, starting on the right, proffering his hand on every side like a true beggar. They wondered who he was, and asked each other where he had come from, giving him food out of pity.

Then up spoke Melanthius the goatherd: ‘Suitors to our noble queen hear me on the subject of this stranger, since I’ve seen him before. The swineherd brought him here, though I don’t know for sure what native country he claims.’

At this, Antinous rounded on the swineherd: ‘Eumaeus, the famous, why on earth did you drag this fellow here? Haven’t we vagrants enough already, beggarly nuisances to ruin our feasts? Isn’t it enough for you that they all crowd in here, swallowing your master’s stores, without you inviting this wretch too?’

Eumaeus, the swineherd, you answered him then: ‘Antinous, noble as you are your words sound ill. Who searches out foreigners himself, and invites them home, unless they are masters of some universal art: a seer, or physician, or architect, or perhaps a divine minstrel who delights men with song? Such men are welcome throughout the boundless earth, but no one would invite a burdensome beggar. You are the harshest Suitor where Odysseus’ servants are concerned, harshest of all to me: but I don’t care as long as loyal Penelope, my lady, and godlike Telemachus live here.’

But wise Telemachus spoke to him: ‘Silence now: don’t waste words answering Antinous: it’s ever his way to employ harsh language and with trouble in mind stir men to anger, encouraging others to do the same.’

BkXVII:396-461 Antinous is angered

He added winged words for Antinous himself: ‘Antinous you show your concern for me indeed, like a father for a son, advising me to drive that stranger by force of words from the palace. No, no, may the gods forbid such a thing. Give him some food yourself, since I don’t begrudge it, but tell you to do so, rather, paying no attention to my mother, or any of the servants in Odysseus’ palace. But you are minded quite differently in truth, preferring to dine yourself rather than give to another.’

‘Telemachus,’ Antinous retorted, ‘brave spirit and noble orator, what are you saying? If every Suitor gave him as much as I would, he’d avoid this house for a full three months.’ And with that he snatched up a stool from under the table where it stood, the one he propped his bright-sandaled feet on during the feast, and flourished it. Nevertheless all the others gave something, and Odysseus filled his leather pouch with scraps of bread and meat. Odysseus was heading back to the threshold having sounded out the Achaeans scot-free, when he paused near Antinous and spoke to him: ‘Give me something, Friend, since you seem to me the best and not the least of the Achaeans here. You look every inch a king, and therefore it is right you should give me a better portion than the others and I will sound your name throughout the boundless earth. I too once had a house of my own among men. I too lived in riches in a fine palace, and often gave gifts to the stranger, whoever he might be, whatever his needs were. I had servants too without number, and an abundance of all that counts as wealth and allows a man to live well.

But Zeus the son of Cronos ended that – such was his pleasure – when he prompted me to my ruin, sailing the long voyage to Egypt, as a wandering corsair. There in the Nile I moored my curved ships. Then I told my loyal companions to stay and guard them, while I sent scouts to find the highest ground. But my crews, feeling confident, and succumbing to temptation, set about plundering the Egyptians’ fine fields, carrying off women and children, and killing the men till their cries reached the city. Hearing the shouting the people poured out at dawn and filled the plain with infantry, and chariots, and the gleam of bronze. Zeus who hurls the lightning bolt filled my men with abject fear, and not one had the courage to face the enemy who threatened us on all sides, or hold his ground. Then they killed many of us with their bronze weapons, and dragged the rest off to the city as slaves. As for myself, they handed me over to a friend of theirs, Dmetor son of Iasus, mighty ruler of Cyprus, who took me there, and from there I reached here, in much distress.’

‘What god is it,’ Antinous said, ‘who brings this creature here to blight our feast? Get away from my table, stand over there in the middle, you insolent and shameless beggar, lest you end up in a place more bitter than Egypt or Cyprus. Every man in turn you try will no doubt give to you without conscience or restraint, since there’s never a thought of holding back when there’s plenty to hand, and they’re making free with another man’s wealth.’

Resourceful Odysseus drew back and answered: ‘How’s this? It seems your brains don’t match your looks! If you can’t bring yourself to break off a piece of bread, when there’s plenty here, and give it to a suppliant at another man’s table, is it likely you would give even a grain of salt from your own?’

At this, Antinous glowered, angered the more, and spoke winged words with a dark look: ‘Now you’re truly casting aspersions I doubt you’ll get out of this hall unscathed.’

BkXVII:462-504 Odysseus is struck on the shoulder

And with that he grasped the stool and threw it, striking Odysseus on his back, under the right shoulder. But Odysseus stood firm as a rock, and did not reel at the blow. He merely shook his head in silence, thinking dark thoughts in the depths of his mind. Then he returned to the threshold, sat down with his well-filled bag, and addressed the Suitors.

‘Hear me, you Suitors of the noble Queen, while I say what my heart feels. When a man is struck, fighting for his own possessions, his cattle or his white sheep, there’s no reason for shame or grief: but Antinous’ blow was on account of my ravening hunger, a cursed plague that brings men plenty of trouble. If there are gods and Furies even for beggars let Antinous find death before he can marry.’

Antinous, Eupeithes’ son, retorted: ‘Stranger, sit quiet and eat, or go elsewhere, lest the young men drag you by hand or foot through the house, and scrape off all your skin.’

Such were his words, but the others were indignant, and one proud youth said: ‘Antinous, you were wrong to strike at a wretched vagrant. What if he chanced to be some god from heaven? You’d be a doomed man. The gods put on all kinds of disguises, and in the form of wandering strangers do indeed visit our cities observing human virtue and vice.’

So the Suitors murmured, but Antinous ignored their words, and though Telemachus nursed great grief in his heart at the blow to his father, he shed not a tear, but shook his head in silence, thinking dark thoughts in the depths of his mind.

But wise Penelope, hearing of Antinous’ striking the beggar in the hall, cried out so her handmaids heard: ‘I hope Apollo the keen Archer strikes you in the same way!’ And her housekeeper, Eurynome, added: ‘If only our prayers might be fulfilled, not one of those men would see the Dawn, golden-throned.’

‘Nurse,’ wise Penelope replied, ‘they are all hateful, plotting evil but Antinous above all is a man dark as death. See now, when a wretched beggar goes through the hall asking alms out of need while all the rest fill his bag generously Antinous hurls a stool at his back and strikes him on the shoulder.’

BkXVII:505-550 Penelope summons the stranger

While she sat in her room talking with her maids, noble Odysseus was eating his meal. Penelope then summoned her loyal swineherd, and said to him: ‘Worthy Eumaeus, go and ask the stranger to come to me, so I can welcome him and ask if he has seen or heard anything of my steadfast Odysseus. He has the look of a much-travelled man.’

Eumaeus, the swineherd, you answered her, saying: ‘My Queen, I only wish the Achaeans would cease their noise, since his speech is entrancing. He stumbled upon me first after he’d escaped from a ship by stealth. Three days and nights he stayed with me in the hut, but even then the story of his sufferings was incomplete. Sitting in my house, he held me entranced, like a man gazing at a bard who sings songs of longing the gods have taught him, to mortal ears. He claims he is an old family friend of Odysseus, and hails from Crete where Minos’ people live. He arrived here in his wandering far from that island, always dogged by suffering. And he swears he has heard news of Odysseus, that he is alive and nearby in the rich Thesprotian country, and is bringing home a fortune in treasure.’

‘Go and summon him here,’ said wise Penelope, ‘so that he can tell me so, face to face. As for those Suitors, let them have their sport, outside or in the hall below, light-hearted because their own stores of bread and mellow wine are safe at home with only their servants to taste them, while they crowd our house day after day, killing our sheep and oxen and well-fed goats, feasting and wasting our glowing wine: squandering our wealth, because there is no Odysseus here to stave off ruin. But if Odysseus comes home to his own country, he and our son will take revenge on these men for their rapacity.’

As she finished, Telemachus sneezed loudly in the echoing hall, and Penelope laughed, and said to Eumaeus with winged words: ‘Go, please, and summon the stranger to me. You see my son sneezed at my words? So will death strike the Suitors, every man, not one will escape their fate. And remember this that I say as well: if I find that he speaks the truth I will fit him out in handsome clothes, a tunic and a cloak.’

BkXVII:551-606 Odysseus declines to see Penelope

Hearing this promise, the swineherd went to find Odysseus, and spoke aloud to him with winged words: ‘Old man, wise Penelope, the mother of Telemachus, wishes to see you. Sorrowful as she is, her heart prompts her to ask for news of her husband. If she finds that you speak the truth, she will give you what you need most, a tunic and cloak, since as for food you can beg throughout the island to feed your belly, and anyone will give it to you.’

Noble long-suffering Odysseus answered: ‘Eumaeus, I will tell the whole truth to wise Penelope, Icarius’ daughter, shortly. I know all about Odysseus: he and I have suffered alike. But I fear this harsh crowd of Suitors, whose violence and irreverence reaches the adamantine heavens. Just now when that man struck me a blow and hurt me, as I wandered harmlessly round the hall, no one including Telemachus did a thing to prevent it. So ask Penelope, even though she is eager to see me, to wait until sunset darkens the hall, then she can give me a seat nearer the fire and ask me about her husband and his homecoming, for my clothes are ragged as you know, you whom I first asked for help.’

Hearing this, the swineherd returned, and as he entered the room, Penelope said: ‘Eumaeus, you fail to bring him here. What does the stranger mean by it? Is he more afraid than he should be of something, or does he hesitate for some other reason? A shy beggar makes a poor one.’

Eumaeus, the swineherd, you answered her then, saying: ‘He is right, anyone would agree, in wanting to avoid the insolence of arrogant men. So he asks you to wait till sunset, which is a more fitting time for you too, my Queen, to speak to a stranger alone, and hear what he has to say.’

Wise Penelope answered: ‘The stranger is not devoid of judgement in guessing how things might be, since I don’t believe there are any men on earth who plot such wicked and insolent games as these men do.’

When she had finished speaking, and he had said all he had to say, the worthy swineherd left to rejoin the crowd of Suitors. At once he sought Telemachus, and holding his head close whispered winged words to him in secret: ‘Dear master, I will go and protect the farm and the pigs, your livelihood and mine. You must be in command here. Above all consider your own safety, be alert for any threat against you, since many of the Achaeans are planning evil. And may Zeus destroy them before they can strike at us.

‘May it be so, old Friend, have your supper and go. Return in the morning with some fine animals for the slaughter. Leave all here in my hands and the gods’.’

At this the swineherd seated himself again on the gleaming bench, and when he had quenched his hunger and thirst, he went off to the farm, leaving the courts and halls filled with the revellers, who were enjoying the dancing and singing now that evening had fallen.