Homer: The Iliad

Book III

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2009 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Bk III:1-57 Paris and Menelaus

- Bk III:58-120 Single combat is proposed

- Bk III:121-180 Iris visits Helen

- Bk III:181-244 Helen names the Greek Leaders

- Bk III:245-309 A sacrifice to the gods

- Bk III:310-394 The duel

- Bk III:395-461 Paris and Helen

BkIII:1-57 Paris and Menelaus

Marshalled together under their leaders, the Trojans advanced with cries and clamour, a clamour like birds, cranes in the sky, flying from winter’s storm and unending rain, flowing towards the streams of Ocean, bringing the clamour of death and destruction to Pygmy tribes, bringing evil and strife at the break of day. The Achaeans, however, breathing fury, firm in resolve to aid each other, came on in silence.

As when a Southerly veils the mountain-tops in mist, a mist the shepherds hate, where a man can see less than a stone’s throw ahead, but thieves hold it dearer than darkness, so thick clouds of dust rose under their feet as they sped over the plain.

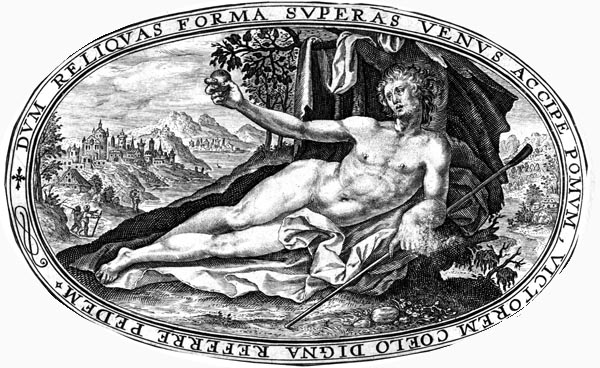

And as they approached in their advance, godlike Paris stepped out from the Trojan ranks as their champion, a panther’s skin on his back, a sword and a bow slung over his shoulders; flourishing twin bronze-tipped spears he challenged the best of the Greeks to meet him, face to face, in single combat.

‘Paris of Troy’ - Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1613

When Menelaus, beloved of Ares, saw him stride out from the host, he felt as the hungry lion does that finds the whole carcase of a wild goat, or an antlered stag, and tears it greedily, though nimble hounds and powerful huntsmen plague him: such was his pleasure when he saw godlike Paris, and primed for revenge on one who had wronged him he leapt down from his chariot in full armour.

But Paris was sick at heart when he saw who had met the challenge, and shying from death shrank back into the ranks. As a man in a steep ravine starts when he sees a snake; trembles in every limb, and retreats with pallid face, so godlike Paris, fearing Atreides, hid among the throng of Trojan warriors.

There Hector met him, and showered reproach on him: ‘Sinful Paris beautiful to look on, seducer and deceiver of women, I wish you had never been born, or had died before you wed. Such is my wish indeed, far better than disgrace us all, an object of men’s contempt. The long-haired Greeks must laugh out loud, and cry that our champion was chosen only for beauty, devoid of strength and courage. Was it not you who with your close comrades sailed the deep in your sea-going ships, mixed with foreigners and brought back a fair woman from a far-off land, the daughter of fierce spearmen, a source of woe to your father, city, nation; pleasing your enemies, shaming yourself? And dare you not face Menelaus, beloved of Ares, now? You would find what kind of man it is whose fair wife you stole. Your lyre will not help you, nor will those gifts of Aphrodite, your looks and your flowing locks, when he lays you in the dust. But the Trojans lack spirit or you would have sunk beneath a shower of stones by now, given all your sinful ways.’

Bk III:58-120 Single combat is proposed

Godlike Paris replied: ‘Hector you only say what is right in rebuking me: as always your heart is true, like an axe that splits a beam in the hands of a shipwright working his skill more powerfully shaping the timber; your heart is just as unswerving, but do not blame me for the sweet gifts of golden Aphrodite. Great gifts of the gods are not to be despised: no man of his own free will chooses what they give. Well, if you want me to fight this duel, let the Trojans and Achaeans take their seats, and I will meet Menelaus, beloved of Ares, before both armies, and fight for Helen and her riches. Whichever wins and shows himself the better man let him take both wealth and woman to his house. And the rest of you can sign a treaty under oath to live on Troy’s rich soil, while our enemies sail for Argos, the horse-pasture, and Achaea, the land of lovely women.’

Hector was delighted at his words, and grasping his spear by the middle pushed the men back, and forced them to be seated. But the long-haired Greeks fired arrows towards him, and pelted him with stones, till Lord Agamemnon shouted: ‘Argives, hold: enough you Greeks, enough, Hector of the gleaming helm desires to speak.’

At once, they ceased their attack and fell silent, while Hector spoke to both the armies: ‘Listen, you Trojans, and you bronze-greaved Greeks, these are the words of Paris, source of all this strife. He asks that both sides ground their sharp weapons while he and Menelaus, beloved of Ares, fight in single combat between the armies, for Helen and all her treasure. Whichever wins and shows himself the better man let him take both wealth and woman to his house, while the rest of us sign a treaty under oath.’

When he finished, silence reigned, till Menelaus of the loud war-cry spoke: ‘Hear me, now. Mine is the heart that suffered most: I propose that Greeks and Trojans part in peace, for you have borne much pain through this quarrel of mine with Paris, though he began it. Whichever of us is fated to die: let him fall; the rest of you shall leave swiftly in peace. Bring two sheep, white ram and black ewe, to sacrifice to Earth and Sun, and we will bring another for Zeus, and let great Priam swear the oath himself, since his sons are reckless and break trust, lest some presumptuous action violate the oaths of Zeus. Fickle are the hearts of the young: but old men have regard to the future and the past, so the outcome of their actions may fall out best for both sides.’

The Greeks and Trojans thrilled to his words, seeing an end to the pain of war. The chariots were reined in along the lines, and the charioteers descended, and shed their battle gear in tightly-spaced piles on the ground. Meanwhile Hector sent two runners to the city to summon Priam and bring the sacrifice. Likewise King Agamemnon sent Talthybius to the hollow ships, telling him to return with a lamb. He straight obeyed.

BkIII:121-180 Iris visits Helen

Meanwhile Iris, disguised as Helen’s sister-in-law, Laodice, loveliest of Priam’s daughters and wife of Antenor’s son, Helicaon, brought news to white-armed Helen. She found her in the palace, weaving a great double-width purple cloth, showing the many battles on her behalf between the horse-taming Trojans and the bronze-greaved Achaeans. Swift-footed Iris nearing her, said: ‘Dear sister, come see how strangely Greeks and Trojans act. From threatening each other on the plain, hearts fixed on deadly warfare, they descend to sitting in silence, leaning on their shields, spears grounded, and no sign of conflict. But Paris it seems and Menelaus, beloved of Ares, plan to fight for you with their long spears, and the winner will claim you as his wife.’

Her words filled Helen’s heart with tender longing for her former husband, her parents and her homeland. She veiled herself in white linen, and, weeping large tears, she left her room accompanied by her handmaids, Aethra daughter of Pittheus, and ox-eyed Clymene. Swiftly they reached the Scaean Gate.

There Priam sat with the city Elders, Panthous, Thymoetes, Lampus, Clytius, Hicetaon, scion of Ares, and the wise men Antenor and Ucalegon. Too old to fight, they were nevertheless fine speakers, perched on the wall like cicadas on a tree that pour out sound. Seeing Helen ascend the ramparts, they spoke soft winged words to each other: ‘Small wonder that Trojans and bronze-greaved Greeks have suffered for such a woman, she is so like an immortal goddess. Yet lovely as she is, let her sail home, not stay to be a bane to us and our children.’

But Priam called Helen to his side: ‘Come, dear child, and sit with me. See there, your former husband, your kin and your dear friends. You are not guilty in my eyes. Surely the gods must be to blame, who brought these fateful Greeks against me. Tell me who that great warrior is, that tall and powerful Achaean. There are others taller, true, but I have never seen so handsome or so regal a man, every inch a king.’

‘I respect and reverence you, dear father-in-law,’ the lovely Helen replied: ‘I wish I had chosen death rather than following your son, leaving behind my bridal chamber, my beloved daughter, my dear childhood friends and my kin. But I did not, and I pine away in sorrow. But let me answer what you ask. That is imperial Agamemnon, Atreus’ son, a great king and mighty spearman. He was brother-in-law to this shameless creature here, unless it was all a dream.’

BkIII:181-244 Helen names the Greek Leaders

The old man viewed Agamemnon with wonder: ‘Ah, happy son of Atreus, fortune’s child, blessed by the gods! All these Achaeans, then, are your subjects. I journeyed to vine-rich Phrygia once, and saw the host of warriors, masters of gleaming horses, men of Otreus’ army and godlike Mygdon’s too, camped by the banks of the River Sangarius. Their ally, I was with them when the Amazon women attacked and fought like men. But that force would be outnumbered by these bright-eyed Achaeans.’

Then he saw Odysseus and asked: ‘Who is he, dear child? Tell me of that man shorter than Agamemnon, but broader in the chest and shoulders. He heaps his armour on the ground and ranges the ranks like the leader of the flock, the fleecy ram that roams among white ewes.’

‘That’, replied Helen, daughter of Zeus, ‘is wily Odysseus, Laertes’ son, reared in Ithaca that rocky isle, master of tricks and clever devices.’

‘True, indeed, lady’ added wise Antenor. ‘He has been here before with Menelaus, beloved of Ares, on an embassy regarding you. They were guests in my house, and I know their looks and stature and all their guile. When they stood among our assembled Trojans, Menelaus was the taller, but, seated, broad-shouldered Odysseus was more regal. And when they began to weave their web of cunning speech, Menelaus, it is true, spoke fluently and clearly, but briefly, since though the younger he was a man of few and concise words. But when wily Odysseus rose to speak, he stood with his gaze fixed on the ground, his staff gripped tight and motionless, as if he were a man of little experience. Yet when that great voice issued from his chest, with words like flakes of winter snow, no mortal man could rival him; and we were no longer fooled by his appearance.’

Ajax was the third warrior the old king noticed: ‘Who is that other tall and mighty Greek, head and shoulders above the rest?’

‘That is great Ajax, shield of the Achaeans,’ answered the lovely long-robed Helen, ‘and godlike Idomeneus stands among his Cretans on the other side, with his generals gathered round. Whenever he came from Crete, Menelaus, beloved of Ares, would entertain him in our house. Though I see all the rest of the bright-eyed Greeks whom I know and could name, I see no sign of my two brothers, Castor the horse-tamer, and the boxer Polydeuces. Either they failed to join the fleet when it left fair Lacedaemon, or having reached here in their sea-going craft they choose not to mingle with these warriors for fear of the scorn and insults poured on me.’

She spoke, not knowing the rich soil already covered them, in Lacedaemon, their sweet native land.

BkIII:245-309 A sacrifice to the gods

The heralds, meanwhile, were bringing the sacrificial offerings from the city, two lambs, and a goatskin bottle full of heart-refreshing wine, the fruit of the earth. Idaeus was one of them, and he carried a gleaming bowl and golden cups; he came to the old king’s side and stirred him to action, saying: ‘Up, son of Laomedon, for the leaders of the Trojans, the horse-tamers, and of the Greeks, the bronze-clad Achaeans, summon you to the plain to swear a truce. Paris and Menelaus, beloved of Ares, will fight with long spears for the woman; and whichever shall win shall have her and her wealth, and the rest of us sign a treaty under oath to live on Troy’s rich soil, while our enemies sail for Argos, the horse-pasture, and Achaea, the land of lovely women.’

Hearing his words, the old man shuddered, but told his men to harness the horses, which they did and quickly. Then Priam mounted his fine chariot and took the reins, and with Antenor at his side drove his swift horses through the Scaean Gate into the plain.

When they reached the opposing armies, they stepped down from the chariots onto the rich dust and entered the space between them. Then Agamemnon, king of men, and wily Odysseus stood forth, and the noble heralds brought the sacrificial offerings, mixed wine in the bowl, and laved the royal hands. And Atreides drew the knife that ever hung next the great scabbard of his sword, and cut wool from the heads of the lambs, which the heralds shared among the Greek and Trojan leaders. Now Agamemnon raised his arms and prayed aloud: ‘Father Zeus, great and glorious, you who reign on Ida, and you all-seeing and all-knowing Sun, and you rivers, and you earth, and you beneath that take vengeance on the dead for their oath-breaking: be witness to what we solemnly swear. If Paris kills Menelaus, Helen and all her treasure are his to keep; and we depart in our sea-going ships. But if red-haired Menelaus kills Paris, the Trojans must yield Helen and her riches, and pay the Greeks proper recompense, on a scale men shall remember. And if Priam and his sons choose not to pay though Paris falls, then we fight on to win our claim, however long it takes to make an end to war.’

So saying, he slit the lambs’ throats with the merciless bronze, and loosed them to the earth as they gasped for breath, the knife robbing them of their powers. Then wine from the bowl was poured into the cups, and oaths sworn to the immortal gods. This was the Greek and Trojan plea: ‘Great and glorious Zeus, and all you deathless gods, may the brains of whatever race first wreaks harm in defiance of this treaty be poured out, like this wine, on the ground, theirs and their children’s too; and their wives be taken in servitude.’

That was their prayer, but Zeus would yet thwart their hopes. Dardanian Priam spoke then, saying: ‘Hear me, Greeks and Trojans. I will return now to windy Ilium, since I cannot bear to watch my beloved son fight Menelaus, beloved of Ares. I think Zeus and the immortal gods already know which of them is fated to die.’

BkIII:310-394 The duel

With these words the godlike king set the lambs in his fine chariot and took the reins, and with Antenor by his side drove back to Troy. Meanwhile Hector, Priam’s son, and noble Odysseus marked out the ground, and then cast lots in a bronze helmet to decide who should first let fly his spear. The warriors of both armies raised their arms in prayer, and this was the Greek and Trojan plea: ‘Father Zeus, great and glorious, who reigns on Ida, whichever man brought these sorrows on both nations, let him die and descend to Hades, but let solemn oaths bring friendship between us.’

They prayed, while Hector of the gleaming helm cast lots, head turned away; and instantly out leapt that of Paris. Then the warriors seated themselves in rows, by their high-stepping horses and their piles of inlaid gear. Now, noble Paris, blonde Helen’s husband, donned his fine armour. First he clasped the greaves about his legs, splendid ones with silver clips; next fitted his brother Lycaon’s cuirass over his chest, adjusting it himself; from his shoulder he slung his bronze sword with silver studs, then his thick and sturdy shield; on his firm head he set a well-made helm with horse-hair crest, grimly the plume nodded from its crown, and grasped a brave spear tailored to his grip. Likewise warlike Menelaus donned his battle gear.

When they had armed themselves on either side, they strode to the space between the hosts, glaring so terribly the watching throng were spellbound, both the horse-tamers of Troy and the bronze-clad Achaeans. They met on the ground marked out, brandishing their spears at each other in anger. First Paris hurled his long-shadowed spear, striking Menelaus’ firm round shield; the bronze point failing to pierce its thickness. Then Atreides ran forward with his weapon in turn, raising a prayer to Father Zeus: ‘Lord, let me gain revenge on noble Paris who wronged me, let my hand strike him down, so that future generations shall shudder at harming a host who shows them friendship.’

So saying, he lifted his long-shadowed spear, and hurled it, striking the son of Priam’s firm round shield. Right through the gleaming shield the mighty weapon flew, forcing its way on through the rich cuirass, ripping the tunic along his flank, yet Paris swerved aside and dodged dark death. Now Atreides drew his silver-studded sword, and brought it down on his enemy’s helm, shattering the blade in four, which flew from his hand. Then Menelaus glanced to the wide sky with a bitter groan: ‘No god is harsher than you, Father Zeus. Surely I thought to take revenge on Priam’s son, for all the evil he has done, yet now my sword breaks in my hand, my spear, launched from my hand in vain, fails to strike him.’

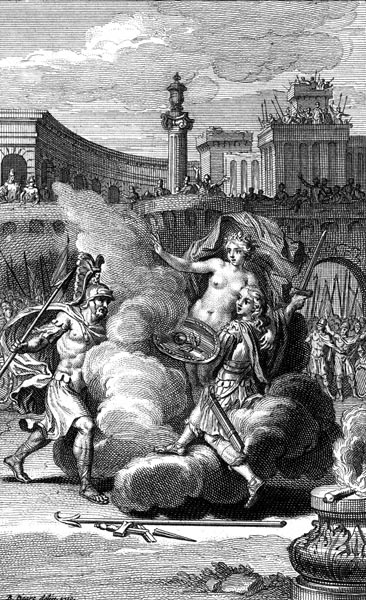

With this he threw himself on Paris, seizing him by his helm’s thick horsehair crest, whirled him round and dragged him towards the Achaean lines.Paris was choked by the richly inlaid strap of his helm, drawn tight beneath his chin, pressing on his soft throat. And Menelaus would have hauled him off and won endless glory, had not Zeus’ daughter Aphrodite, swift to see it, broken the ox-hide strap, so the empty helm was left in Menelaus’ strong grip. He tossed it away into the Greek ranks, where his comrades gathered it, then sprang again to the attack, his bronze spear eager for the kill. But Aphrodite cloaked Paris in mist and, with a goddess’s power, whisked him away, and set him down in his own high sweet-scented room, while she sped off to summon Helen.

‘The duel between Menelaus and Paris’ - Workshop of Bernard Picart, 1710

She found her on the rampart, with a throng of Trojan women round her. So the goddess stretched out her hand to pluck at Helen’s perfumed robes, and spoke to her, disguised as an old and dearly loved wool-carder, who combed the fine wool for Helen when she lived in Lacedaemon. ‘Come,’ cried the goddess, ‘Paris calls for you. He lies on his inlaid bed in his room, radiant with beauty in his fine garments. You would never guess he had come from a fight: rather that he was off to the dance or resting after dancing.’

BkIII:395-461 Paris and Helen

Helen was roused by her words then struck with wonder, as the goddess revealed her lovely neck and shoulders, and her bright eyes. She addressed her, saying: ‘Goddess, why choose to deceive me so? Now Menelaus has beaten noble Paris, and wants to drag his shameful wife home, would you have me follow you to some great city in Phrygia or sweet Maeonia, destined for some other man dear to you? Is that why you come here full of guile? Go yourself, and sit beside him, forget your deity, abandon Olympus, fret over him and pamper him, be his wife then, or at least his slave. I shall not run, for shame, to share his bed again; the Trojan women would scorn me if I did, and anyway my heart is full of sorrow.’

Fair Aphrodite turned on her, in anger: ‘Obstinate woman, provoke me to fury and I’ll desert you, and hate you as deeply as I still love you yet, and bring on you the fierce enmity of Trojan and Greek alike; then indeed would your fate be evil.’

Zeus-begotten Helen was gripped by fear, as she spoke, and wrapping herself in her bright shining mantle, followed the goddess without a word, escaping the notice of the Trojan women.

When they reached Paris’ fine house, her handmaids returned swiftly to their tasks, but the fair lady went to her high-roofed chamber. There laughter-loving Aphrodite placed a chair for her, facing Paris, and Helen, daughter of aegis-bearing Zeus, sat with averted gaze berating her lover, saying: ‘So you have left the field: I wish you had died there, at the hands of that great soldier who was once my husband. You used to boast you were a better man than Menelaus, beloved of Ares, a finer spearman, and with a stronger arm. Go back, then, and challenge him, man to man. But my advice would be to stay here, not fight hand to hand with red-haired Menelaus, nor taunt him rashly, lest his spear conquers you.’

‘Paris declares his love to Helen’ - Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1613

‘Lady, restrain your harsh abusive words of reproach. Athene helped Menelaus win this time, but I will conquer him the next; there are gods to aid us too. Come to bed, and know the joy of love, for I have never desired you more than now, for love and sweet desire seize me, not even when I first took you from Lacedaemon aboard my sea-going ship, and slept with you on Cranae’s isle.’ So saying, he drew his wife to the bed, and they lay down together.

Meanwhile Atreides ranged like a wild beast through the ranks, trying to catch a glimpse of Paris. But none of the Trojans or their allies could point him out to Menelaus, beloved of Ares, though they hated Paris like death, and nothing would have tempted them to hide him. It was left to Agamemnon to speak out: ‘Hear me, Trojans, Dardanians, and your allies. Victory clearly rests with Menelaus; yield Argive Helen and her riches now, and pay us proper recompense, on a scale men shall remember.’

So the son of Atreus spoke, and all the Greeks shouted their assent.